Abstract

The human FMR1 gene contains an unstable CGG-repeat in its 5′ untranslated region. The repeat length in the normal population is polymorphic (5-54 CGG-repeats). Individuals carrying lengths beyond 200 CGGs (i.e. the full mutation) show hypermethylation and as a consequence gene silencing of the FMR1 gene. The absence of the gene product FMRP causes the fragile X syndrome, the most common inherited form of mental retardation. Elderly carriers of the premutation (PM), which is defined as a repeat length between 55-200 CGGs, can develop a progressive neurodegenerative syndrome: fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS). The high FMR1 mRNA levels observed in cells from PM carriers have led to the hypothesis that FXTAS is caused by a pathogenic RNA gain-of-function mechanism. Apart from tremor/ataxia, specific psychiatric symptoms have been described in PM carriers with or without FXTAS. Since these symptoms could arise from elevated stress hormone levels, we investigated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis regulation using a knock-in mouse model with an expanded CGG-repeat in the PM range (>98 repeats) in the Fmr1 gene, which shows repeat instability, and displays biochemical, phenotypic and neuropathological characteristics of FXTAS. We show elevated levels of corticosterone in serum and ubiquitin-positive inclusions in both the pituitary and adrenal gland of 100-week old animals. In addition, we demonstrate ubiquitin-positive inclusions in the amygdala from aged expanded CGG-repeat mice. We hypothesize that altered regulation of the HPA axis and the amygdala and higher stress hormone levels in the mouse model for FXTAS may explain associated psychological symptoms in humans.

Keywords: FXTAS, Fmr1, CGG-repeat, corticosterone, HPA axis, inclusions

Introduction

The fragile X mental retardation gene 1 (FMR1), located on the X chromosome, harbors a CGG-repeat in its 5′ untranslated region. This repeat may become unstable upon transmission to the next generation. Different clinical outcomes occur depending on the length of this trinucleotide repeat. Normal individuals carry a repeat of up to 44 CGG units, which remains stable on transmission (Fu et al., 1991). Alleles with between 45 and 54 repeats are considered intermediate size alleles, which are associated with some degree of instability. Individuals with over 200 CGGs have the full mutation, which usually leads to methylation of both the promoter region and the CGG-repeat, and consequent transcriptional silencing of the gene. The absence of the gene product fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) is the cause of the mental retardation seen in fragile X patients (Verkerk et al., 1991). Individuals with the premutation (PM) have between 55 and 200 CGGs. Female carriers of the PM are at increased risk of developing premature ovarian failure (POF) (Sherman, 2000). PM carriers also are at risk for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), which has been observed in elderly men over age 50, and less often in female PM carriers (Hagerman et al., 2001; Hagerman and Hagerman, 2002; Jacquemont et al., 2003).

FXTAS is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, believed to be the result of a pathogenic RNA gain-of-function mechanism, as PM carriers produce 2-8 fold elevated levels of FMR1 mRNA in their lymphocytes. While transcription is increased, translation is hampered, resulting in slightly lower FMRP levels in individuals with high CGG-repeat alleles within the PM range (Tassone et al., 2000a; 2000b; Kenneson et al., 2001; Tassone et al., 2007). Patients with FXTAS usually present with tremor and ataxia, but may develop other neurological symptoms such as Parkinsonism, autonomic dysfunction and peripheral neuropathy and may suffer from cognitive decline including formal dementia. Post mortem studies of brains from patients with FXTAS reveal intranuclear inclusions in neurons and astrocytes in multiple brain areas (Greco et al., 2002). These inclusions contain several proteins, including ubiquitin, heat shock proteins including αB-crystallin, the RNA binding proteins hnRNP-A2 (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2) and MBNL1 (muscle blind-like protein 1) and a number of neurofilaments, among which are lamin A/C (Iwahashi et al., 2006) and FMR1 mRNA (Tassone et al., 2004). Very recently, Pur α has been identified as a component of the ubiquitin-positive inclusions in FXTAS brain (Jin et al., 2007). Proteins that are sequestered into the inclusions may be prevented from exerting their normal function, thus resulting in cellular dysfunction, ultimately leading to neurodegeneration (Rosser et al., 2002; Jin et al., 2007; Sofola et al., 2007).

Recent studies have documented that the abnormal elevation of FMR1 mRNA is associated with increased psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, and irritability in adult PM carriers, with or without symptoms of FXTAS, especially males (Jacquemont et al., 2004; Hessl et al., 2005; Bacalman et al., 2006; Bourgeois et al., 2007). These psychological symptoms could arise from elevated stress hormone levels, thus aberrant regulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal gland (HPA) axis. More evidence suggestive of altered regulation of the HPA axis by the PM comes from the observation that ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions are also present in the anterior and posterior lobes of the pituitary gland of patients with FXTAS (Louis et al., 2006; Greco et al., 2007). A link has been suggested between pituitary inclusions and dysregulated neuroendocrine function in patients with FXTAS. Increased Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) (Hundscheid et al., 2001; Sullivan et al., 2005; Greco et al., 2007) and decreased inhibin A and B levels in female PM carriers were reported even in those who are cycling normally, suggestive of early ovarian aging and ovarian compromise (Welt et al., 2004). Elevated levels of FSH have been found to reflect decreasing ovarian reserve (MacNaughton et al., 1992), which can be correlated to the risk of developing POF seen in female PM carriers. Interestingly, intranuclear inclusions have been reported in the testicles of two men with FXTAS; inclusions were present in the anterior and posterior pituitary gland of one of these for whom the pituitary gland was available (Greco et al., 2007). Finally, a reduced amygdala response has been reported in PM male carriers which may explain the etiology of psychological symptoms involving emotion and social cognition as well (Hessl et al., 2007).

An expanded CGG-repeat knock-in (CGG) mouse model has been generated (Bontekoe et al., 2001; Willemsen et al., 2003), by substituting the endogenous mouse (CGG)8 with a human (CGG)98. The CGG-repeat in the mouse model shows instability upon transmission to the next generation (Brouwer et al., 2007), similar to humans. Also, the CGG mice show elevated Fmr1 mRNA levels (Brouwer et al., 2007), as well as ubiquitin-positive neuronal inclusions throughout the brain (Bontekoe et al., 2001; Willemsen et al., 2003). Aberrant behavior in mice was described by Van Dam and colleagues, including mild learning deficits and increased anxiety (Van Dam et al., 2005).

We explored HPA axis physiology in expanded CGG-repeat mice for two reasons: 1) increased anxiety has been observed in our mouse model (Van Dam et al., 2005) and PM carriers, especially those with elevated FMR1 mrNA experience more psychological distress (Hessl et al., 2005); 2) ubiquitin-positive inclusions have been found in the pituitary gland of male patients with FXTAS (Greco et al., 2007). Here we further characterize the expanded CGG-repeat mouse model for FXTAS and more specifically we demonstrate the presence of inclusions in several endocrine organs of the CGG mice and in the amygdala. The amygdala plays an important role in the regulation of the secretion of HPA axis-related hormones in the hypothalamus (Tronche et al., 1998). We also report elevated corticosterone levels in response to a mild stressor. Thus we present evidence that HPA axis physiology is disturbed in CGG mice, which might explain molecular mechanisms underlying psychopathology in PM carriers and/or patients with FXTAS.

Methods and Materials

Mice

Both the expanded CGG-repeat knock-in (CGG) mice and the wild-type (wt, with an endogenous (CGG)8-repeat) mice were housed under standard conditions. All experiments were carried out with permission of the local ethical committee. CGG-repeat lengths were determined for the whole colony, but only male mice were used for experiments. All mice had a mixed C57/BL6 and FVB/n genetic background.

Genotyping of the mice

DNA was extracted from mouse tails as described previously (Brouwer et al., 2007). Determination of the CGG-repeat length was performed by means of PCR using the Expand High Fidelity Plus PCR System (Roche Diagnostics), with forward primer 5′-CGGAGGCGCCGCTGCCAGG-3′ and 5′-TGCGGGCGCTCGAGGCCCAG-3′ as reverse. PCR products were visualized on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. As these primers are specific to the knock-in allele, a separate PCR is performed for the wt allele. The wt allele was detected using TaKaRa LA Taq polymerase (using GC buffer II), according to manufacturer’s instructions (Takara Bio Inc), with 5′-GCTCAGCTCCGTTTCGGTTTCACTTCCGGT-3′ as forward primer and 5′-AGCCCCGCACTTCCACCACCAGCTCCTCCA-3′ as reverse primer (detailed description in (Brouwer et al., 2007)). The 100-week old mice used in this study had CGG-repeat lengths between 100 to 160 CGGs, while 25-week old mice had 160-200 CGGs.

Western blotting

Half brains (sagittal) were homogenised in HEPES buffer. We loaded 100 μg of protein onto an 8% SDS-PAGE gel, which was then electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with the monoclonal 2F5-1 antibody specific for Fmrp (Gabel et al., 2004) and a monoclonal antibody against Gapdh (Chemicon), which served as a loading control. The next day the membrane was incubated with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated rabbit-anti-mouse antibody (DAKO), allowing visualization by chemiluminescence using an ECL kit (Amersham) (for details, see (Brouwer et al., 2007)). Quantification of protein bands was performed using TotalLab software (Nonlinear Dynamics Ltd). All three Fmrp isoforms were taken into account in the calculations. Multiple comparable series of increasing repeat lengths were performed, both for young and old mice. One series, representative of many repeated experiments, is shown.

Blood collection and hormone levels

In the morning, mice were transported from the animal facility to the laboratory in their home cage, which can be considered a mild stressor. After arrival in the laboratory they were left to acclimate for at least 30 minutes. The order of sacrifice was random with respect to genotype. After sacrifice by cervical dislocation, blood was collected immediately from the thoracic cavity by perforating the right cardiac atrium and collecting the resulting blood flow. Blood was kept at 4°C overnight and centrifuged the next day at 4°C for 15 minutes. The supernatant was stored at −20°C until analysis. Serum corticosterone levels were estimated using radio immunoassays or enzyme immunoassays for the determination of corticosterone in serum provided by Diagnostic Systems Laboratories (Webster, TX). Both assays use the same antiserum and yielded identical results for the internal quality control sera. Intra-assay and inter-assay variation coefficients were below 7 and 13%, respectively. Thus, all data were analyzed together.

Measured serum corticosterone levels did not follow a normal distribution (positively skewed: standard deviation > ½ * mean). Therefore measured corticosterone levels were subjected to logarithmic transformation. The lognormal plot showed a strongly improved distribution, hence the log-transformed data were used for further analysis. Back-transformation of the means of the values by calculating 10mean gives the geometrical mean (GM). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on log-transformed corticosterone levels to test the difference between wt and CGG mice, at 25 and 100 weeks of age. Since a significance was revealed, posthoc pair wise comparisons were performed with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Geometrical mean differences (GMD) are presented with their respective corrected p-value. GMDs were calculated by subtracting back-transformed mean log-transformed corticosterone levels. The correlation between corticosterone levels and repeat length was also examined. The statistical software package SPSS (version 11) was used for all analyses. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Immunohistochemistry

After mice were sacrificed brains were dissected, followed by the pituitary gland and adrenal gland and fixed overnight in 3% paraformaldehyde. Tissues were embedded in paraffin according to standard protocols. Sections (7 μM) were deparaffinised followed by antigen retrieval using microwave treatment in 0.01 M sodium citrate solution. Endogenous peroxidase activity blocking and immunoincubation were performed as described before (Bakker et al., 2000), using a polyclonal rabbit antibody against ubiquitin (Dako, ZO458), a monoclonal antibody against FMRP (1C3) (Bakker et al., 2000) and a polyclonal antibody against glucocorticoid receptor (GR: Affinity BioReagents PA1-511A). Ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusion counts in amygdala, pituitary and adrenal gland were determined by counting the number of inclusion-bearing cells in a field of 100 neurons counted. Per area of interest three fields of 100 neurons were counted. Mean counts and the range are given.

RNA isolation, RT and Q-PCR

RNA of pituitary glands of 100-week old animals was extracted using a RNeasy Mini Kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). RNA concentration and purity were determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies). Reverse transcriptase was performed on 1 μg RNA using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Detailed description of RNA isolation and RT can be found in Brouwer et al (2007). Q-PCR was performed on 0.1 μl of RT product. Primers used for Q-PCR were as follows: Fmr1 (transition exon 7/8: forward: 5′-TCTGCGCACCAAGTTGTCTC -3′, reverse: 5′-CAGAGAAGGCACCAACTGCC-3′), Gapdh (forward: 5′-AAATCTTGAGGCAAGCTGCC-3′, reverse: 5′-GGATAGGGCCTCTCTTGCTCA-3′), GR (nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 1: Nr3c1: transition exon 4/5: forward: 5′-CAAAGGCGATACCAGGATTCA-3′, reverse: 5′- GGGTCATTTGGTCATCCAGGT-3′), Corticotropin releasing hormone receptor type 1 (Crhr1: transition exon 2/3: forward: 5′-TCTGACAATGGCTACCGGG-3′, reverse: 5′-AATAATTCACACGGGCTGCC-3′), Arginine vasopressin receptor 1b (Avpr1b: transition exon 1/2: forward: 5′-GGACGAGAATGCCCCTAATGA-3′, reverse: 5′-TCGAGATGGTGAAAGCCACAT-3′) and Proopiomelanocortin (Pomc: transition exon 2/3: forward: 5′-AACCTGCTGGCTTGCATCC-3′, reverse: 5′-TGACCCATGACGTACTTCCG-3′). Efficiencies of the different primer sets were checked and found to be comparable. Ct values of the reference gene were subtracted from the Ct value of the target gene for each sample, which gives the ΔCt. ΔCt of wt was then subtracted from ΔCt of CGG mice, which is designated as the ΔΔCt. 2−ΔΔCt then gives fold change.

Results

All knock-in mice have a CGG-repeat length in the PM range, and they all show Fmrp expression as illustrated by Western blot analysis (figure 1). Analysis of different CGG-repeat animals shows that Fmrp levels decrease mildly with increasing repeat length and a transition to reduced levels seems to occur around 170 CGGs. Western blot was performed on multiple series of brain lysates of mice with increased repeat lengths. All experiments showed the same pattern, both when brains from old (72- or 100-weeks old) and young (25-weeks old) were used. Figure 1 shows a series representative of what was seen in all experiments. For the samples used in figure 1, quantification of the amount of Fmrp in each sample relative to wt brain revealed 100% for 112 and 129 CGG-repeats and 80% and 70% for 174 and 184 CGGs respectively.

Figure 1.

Fmrp levels at different CGG-repeat lengths in 100-week old whole mouse brain lysates.

An antibody against Gapdh was used as loading control. Fmrp levels decrease mildly as CGG-repeat length increases. Quantification of the amount of Fmrp in each sample relative to wt brain revealed 100% for 112 and 129 CGG-repeats and 80% and 70% for 174 and 184 CGGs respectively.

Corticosterone levels in CGG mice

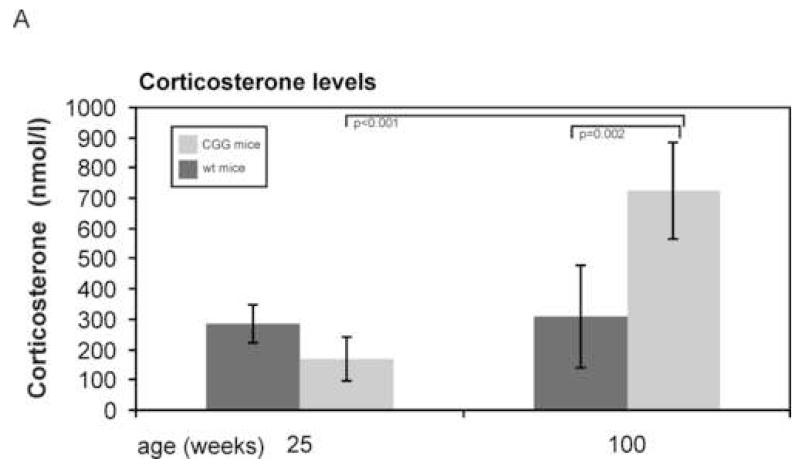

To study the regulation of the HPA axis in our mouse model, we first investigated the endpoint of this axis, namely corticosteroid levels. The predominant corticosteroid in mice is corticosterone. Moving the mice from the animal facility to the laboratory where they were sacrificed is a mild stressor. We waited at least 30 minutes before mice were sacrificed and since corticosterone response to stress occurs within approximately 30 minutes, we measured corticosterone levels in response to this mild stressor (Veenema et al., 2003; Dallman, 2005; McGill et al., 2006). Mean corticosterone levels as measured in CGG and wt mice at 25 and 100 weeks of age are depicted in figure 2. One-way ANOVA on log transformed corticosterone levels revealed that the four groups, based on genotype and age, were significantly different (Fdf=3=10.675, p<0.001). Bonferroni corrected posthoc pairwise comparison revealed a statistically significant geometrical mean difference (GMD) between CGG and wt mice at 100 weeks (GMD=285.4, p=0.002) and between CGG mice at 100 weeks and CGG mice at 25 weeks (GMD=338.4, p<0.001). No statistically significant differences were seen between CGG and wt mice at 25 weeks (GMD=−102.1, p=0.44) or between wt mice at 25 weeks and wt mice at 100 weeks (GMD=−49.1, p=1). Scatter plots with repeat length plotted against corticosterone levels for each age did not reveal statistically significant correlations (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Mean corticosterone levels as measured in CGG and wt mice at 25 and 100 weeks of age. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (mean ± 1.96 * st.dev). One-way ANOVA on logtransformed corticosterone levels revealed that the four groups, based on genotype and age, were significantly different (Fdf=3=10.675, p<0.001). Bonferroni corrected posthoc pairwise comparison revealed a statistically significant geometrical mean difference (GMD) between CGG and wt mice at 100 weeks (GMD=285.4 nmol/L, p=0.002) and between CGG mice at 100 weeks and CGG mice at 25 weeks (GMD=338.4 nmol/L, p<0.001).

Ubiquitin-positive inclusions in HPA axis related organs

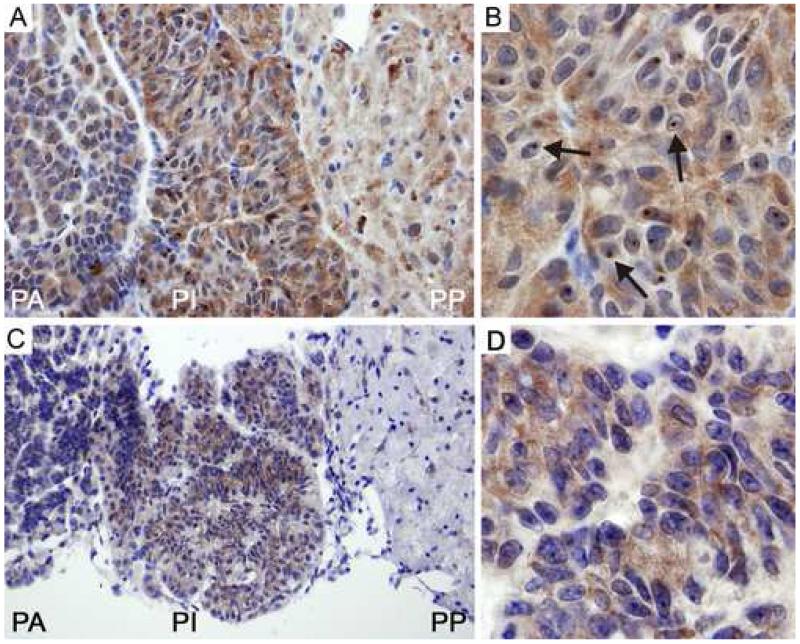

Immunohistochemistry on paraffin sections of the pituitary gland of 100-week old expanded CGG mice showed intranuclear inclusions using an antibody directed against ubiquitin (figure 3). Highest numbers were present in the pars intermedia (table 1 and figure 3A and 3B), while inclusions were seen to a lesser extent in the pars anterior (table 1 and figure 3A). Inclusions were virtually absent in the pars posterior (table 1 and figure 3A). Immunolabelling for Fmrp expression in the pituitary gland correlated with the presence of the number of inclusions, that is, high Fmrp expression in the pars intermedia (figure 3C and 3D) and very low expression in both pars anterior and pars posterior (figure 3C). Immunohistochemistry was also performed on pituitary gland sections of 25-week old CGG mice. Ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions could be detected, although in a much lower percentage of cells (table 1) compared to 100-week old animals. Also they were smaller and less consistently spherical (data not shown). Wild-type animals did not show inclusions at either age.

Figure. 3.

Immunohistochemistry with antibodies against ubiquitin and Fmrp in pituitary gland of 100-week old CGG mice.

A: Many intranuclear ubiquitin-positive inclusions (arrows) are seen in the pars intermedia, while hardly any were observed in the pars posterior.

B: Ubiquitin-positive inclusions in the pars intermedia.

C: Highest levels of Fmrp are observed in the pars intermedia.

D: Fmrp expression in the pars intermedia. PA: pars anterior, PI: pars intermedia, PP: pars posterior

Table 1.

Mean percentages (range) of pituitary cells with ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in 25-week and 100-week old wt and CGG mice.

| Pituitary gland | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pars anterior | Pars intermedia | Pars posterior | ||

|

|

||||

|

25

wks |

Wt | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

||||

| CGG | 2 (1-3) | 34 (25-45) | 0 | |

|

|

||||

|

100

wks |

Wt | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

||||

| CGG | 18 (4-38) | 58 (44-75) | 1 (0-2) | |

Cellular localization of GRs in pituitary glands of 100-week old mice was not different between CGG mice and wt mice (data not shown).

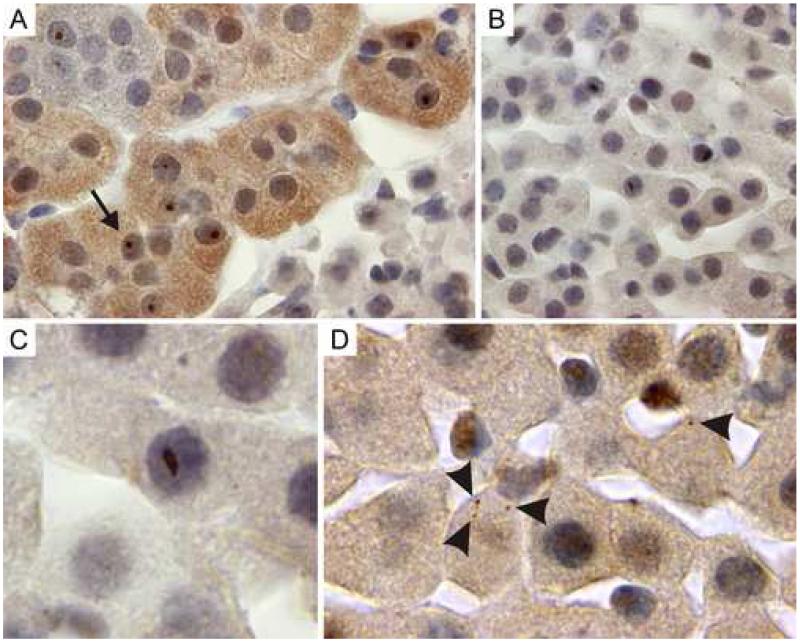

Next, immunostainings for ubiquitin in sections of 100-week old adrenal glands were performed, which showed significant numbers of inclusions in the parenchymal cells of the medulla (figure 4A) and parenchymal cells of the zona fasciculata (figure 4B and C) of the adrenal cortex.

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry with an antibody against ubiquitin show ubiquitin-positive inclusions in adrenal gland of 100-week old CGG mice.

A: Ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions (arrows) in chromaffin cells of the adrenal gland.

B+C: Elongated, irregularly shaped ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in the zona fasciculata of the adrenal gland.

D: Cytoplasmic inclusions (arrow heads) in the zona fasciculata of the adrenal gland.

Parenchymal cells of the zona reticularis and the zona glomerulosa were virtually devoid of inclusions. The percentage of ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in the different layers of the adrenal gland was substantially less compared to the percentage in the pars intermedia of the pituitary gland (table 2).

Table 2.

Mean percentages (range) of adrenal cells with ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in 25-week and 100-week old wt and CGG mice.

| Adrenal gland | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zona glomerulosa | Zona fasciculata | Medulla | ||

|

|

||||

|

25

wks |

Wt | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

||||

| CGG | 1 (0-2) | 2 (0-4) | 6 (5-6) | |

|

|

||||

|

100

wks |

Wt | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

|

||||

| CGG | 1 (0-4) | 4 (1-6) | 16 (9-27) | |

Note that the intranuclear inclusions in the parenchymal cells of the zona fasciculata are more irregularly shaped, more elongated compared to the circular intranuclear inclusions found thus far in brain, pituitary gland and other layers of the adrenal gland. Also, in the zona fasciculata frequently small, round cytoplasmic inclusions were seen, occasionally more than one per cell (figure 4D). In adrenal gland of 25-week old CGG animals, few inclusions were observed (table 2).

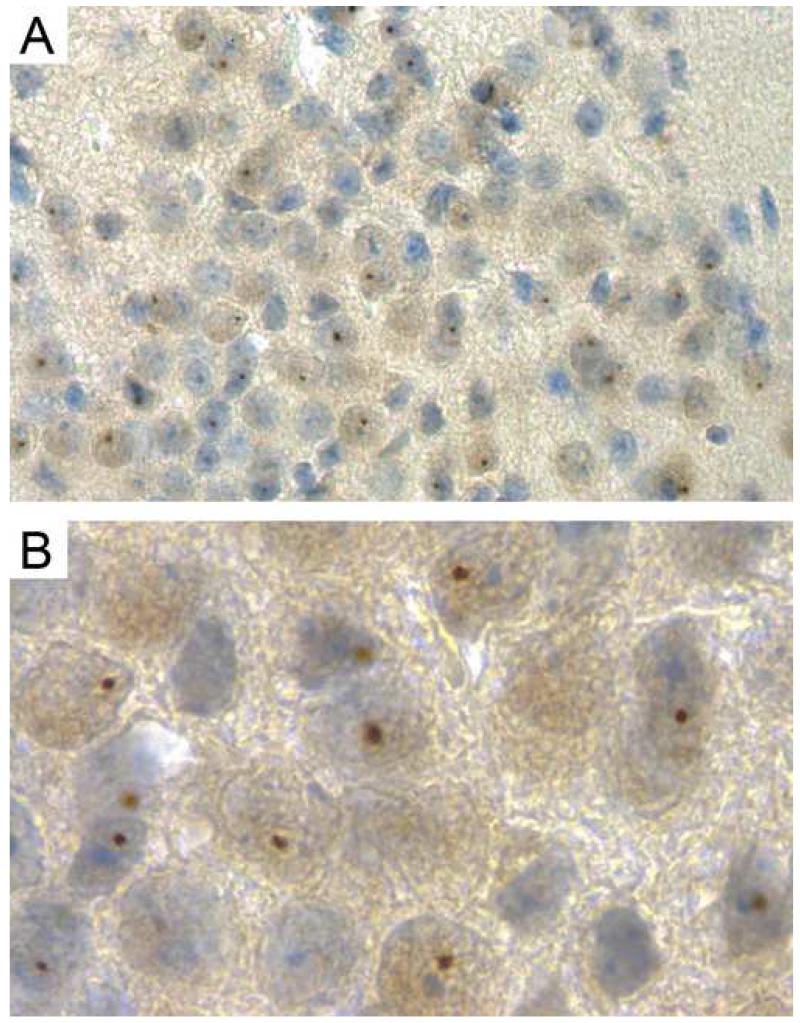

Neurons and astrocytes in the human FXTAS amygdala bear intranuclear inclusions and showed aberrant brain activation in a functional MRI study (Hessl et al., 2007). The amygdala helps control arginine vasopressin (AVP) and corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) secretion in the hypothalamus (Tronche et al., 1998). We observed the presence of intranuclear ubiquitin-positive inclusions throughout the amygdala of 100-week old CGG mice. High percentages were seen in the posteromedial amygdalohippocampal nucleus (figure 5, 59% of neurons counted), the posteromedial cortical amygdaloid nucleus (57%) and the anterior amygdaloid area (58%). Other regions of the amygdala only showed inclusions in up to 5% of neurons. In CGG mice of 25 weeks of age, intranuclear inclusions were counted in on average 6% of neurons in the three regions specified for old mice.

Fig 5.

Ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in the amygdala of a 100-week old CGG mouse. A en B show the posteromedial amygdalohippocampal nucleus, where B is a higher magnification of what is seen in A.

Transcript levels in the pituitary gland

Fmr1 transcript levels were found to be 3.4-fold higher (SD=0.6) in pituitary glands of CGG mice, as compared with wt mice, at 72 weeks of age.

Several feedback mechanisms exist for the HPA axis to prevent lasting high levels of corticosteroids. We analyzed effects of corticosterone binding to its receptor, the GR, namely transcription levels of the glucocorticoid, Crh and vasopressin receptors and of the ACTH precursor molecule Pomc. Quantitative PCR revealed no statistically significant difference for any of the receptors tested, neither for Pomc, in CGG mouse pituitary gland when compared with wt pituitary gland (data not shown).

Discussion

Recently, observations have accumulated that PM carriers, both with and without FXTAS are more often affected by psychiatric problems than controls (Jacquemont et al., 2004; Hessl et al., 2005; Bacalman et al., 2006; Bourgeois et al., 2007). Although a link between the presence of inclusions in the hippocampus and the frequent occurrence of anxiety and depression in patients with FXTAS has been suggested (Jacquemont et al., 2004), little is known about the origin of the psychopathology.

In the CGG mouse model, which shows genetic, biochemical, behavioral and neuropathological parallels to the human situation in FXTAS, we investigated whether altered HPA axis regulation could play a role in the development of these symptoms. The presence of ubiquitin-positive intranuclear inclusions in the pituitary and adrenal glands and the elevated corticosterone levels in 100-week old CGG mice point towards disturbed HPA axis physiology. At 25 weeks of age CGG mice did have ubiquitin-positive inclusions in pituitary gland, although these were smaller in size and number, and less spherical than in the 100-week old animals. In 25-week old CGG mice also inclusions in the amygdala were observed. Interestingly, no inclusions have been observed in other brain regions at this age, including amygdala (Willemsen et al., 2003). It seems that inclusions start to develop around this time point, with the pituitary gland and amygdala being the first sites of inclusion development followed by other regions in the brain at 40-50 weeks of age (Willemsen et al., 2003). At 25 weeks of age corticosterone levels are not yet elevated in CGG mice. Fmr1 mRNA levels are elevated at all ages (Brouwer et al., 2007), including in pituitary gland. If inclusions in the amygdala play a role in the dysregulation of the HPA axis, then apparently a threshold exists for the amount of inclusions that can cause an effect. Intranuclear inclusions in the pituitary gland could impair cellular function, although they may be just a marker for the degree of protein dysregulation that is occurring in the cell.

The presence of inclusions in the pars intermedia is puzzling since this area contains one major endocrine cell type in mammals, the melanotrophs. These cells process the precursor molecule POMC and release β-endorphin and α-melanocyte stimulating hormone. This POMC processing is different from that in the pars anterior, where predominantly ACTH and β-endorphin are released. Also, in adult humans the pars intermedia has undergone involution (Saland, 2001). Negative feedback of corticosteroids occurs via GRs in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and the pituitary gland. Rapid feedback effects of glucocorticoids prepare an organism for a stressful situation (Tronche et al., 1998; Dallman, 2005). Slower gene transcription-mediated systems come into action when corticosteroids bind to the cytoplasmic GR, present as a complex with other proteins among which hsp90 and hsp70. Ligand-binding disassembles the complex, upon which the GR can translocate to the nucleus. There it binds to negative glucocorticoid responsive elements, downregulating factors involved in corticosteroid synthesis (Webster and Cidlowski, 1999; Nishi et al., 2001; Nishi et al., 2004). Hence GR function would be worth investigating. However, since mice were mildly stressed before sacrifice, likely causing GR translocation, no localization differences were observed.

We did not detect differences in pituitary gland receptor mRNA levels, involved in HPA axis negative feedback. The hypothalamus secretes AVP and CRH under the control of the hippocampus and the amygdala (Tronche et al., 1998). CRH provides the predominant stimulus to the anterior pituitary gland to synthesize and secrete ACTH, whereas AVP strengthens the effect of CRH to secrete ACTH. Changes in hormone and receptor levels of the HPA axis are very specifically dependent on the type and duration of stressors (Aguilera, 1994). GR is known to repress its own synthesis in a hormone-dependent manner (Webster and Cidlowski, 1999). Negative feedback at the level of the pituitary gland to block synthesis and secretion of ACTH by the corticotroph cells occurs by directly inhibiting synthesis of Pomc mRNA (Dallman et al., 1994). No such effect was found in pituitary glands of CGG mice in this study. Not finding any transcriptional differences between CGG and wt mice could be because mice were sacrificed before a change at the transcription level could have taken place, or the stressor could have been too mild.

In the adrenal gland, we found ubiquitin-positive inclusions not only in the chromaffin cells of the medulla, which are the main source of catecholamines, but also in the zona glomerulosa and zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex. The zona glomerulosa is the site where mineralocorticoids are produced, while the zona fasciculata produces glucocorticoids (Aguilera, 1993). It is as yet unclear how inclusions might affect the functioning of the adrenal gland. It is striking that the inclusions seen in the zona fasciculata were differently shaped from those seen thus far in brain, pituitary gland and the other cell layers of the adrenal gland. This might indicate that inclusions in the zona fasciculate develop in a different way and from different components compared to the ones studied previously.

A review summarizing observations in a large group of patients with the premutation reported anxiety and depression in over 30% of patients with FXTAS and anxiety in almost 40% and depression in 9% of non-FXTAS PM carriers (Hessl et al., 2005). The authors suggested a relationship with the inclusions present in the hippocampus, which is the area with the highest inclusion density in the human FXTAS brain (Jacquemont et al., 2004). Another study described more psychopathology, including phobic anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients with FXTAS compared to published norms (Hessl et al., 2005). Interestingly, PM carriers without signs of FXTAS also showed more obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Moreover, there was a stronger correlation between psychopathology and FMR1 mRNA levels in PM carriers who had not developed FXTAS, than in patients with FXTAS. It is not yet understood whether psychological symptoms are associated with the PM from a developmental perspective or whether they reflect prodromal symptoms of later onset FXTAS (Hessl et al., 2005). Although patients with FXTAS show higher scores of psychopathology on a neuropsychiatric inventory than controls (Bacalman et al., 2006), anxiety has also been observed in young PM carriers, who were free of FXTAS symptoms. Anxiety along with shyness and social deficits are common among young boys with the premutation compared to brothers who do not have the premutation (Farzin et al., 2006). This suggests that there is a developmental effect of the premutation that can lead to this type of psychopathology. As FXTAS develops these symptoms can be aggravated by the neuropsychological deficits that set in (Bacalman et al., 2006). Another report described that seven out of fifteen male patients with FXTAS suffered from mood and/or anxiety disorders, and twelve out of fifteen were found to have neuropsychological problems (Bourgeois et al., 2007). Increased irritability, agitation/aggression and anxiety might suggest further HPA axis dysregulation.

Naturally, it will be of interest to measure cortisol levels in PM carriers with and without FXTAS. In humans, it is as yet unknown whether only symptomatic PM carriers develop inclusions or whether the PM itself leads to inclusion formation with another factor in turn causing clinical manifestations. All mice carrying the PM develop inclusions, so the mouse model cannot be used to show whether individuals without inclusions will suffer from a similarly altered HPA axis regulation and associated psychopathology.

Given the broad range of cognitive and emotional disturbances seen in PM carriers or patients with FXTAS, it cannot be excluded that altered HPA physiology is secondary to impaired coping strategies in stressful situations. For example, the amygdala was suggested to be a potential site of dysfunction underlying social deficits, when PM carriers showed diminished brain activation in the amygdala and other brain areas that mediate social cognition while viewing fearful faces in a functional MRI study. In the same study, sympathetic activation as measured by skin conductance upon a mild social stressor, was also lower in PM carriers than in controls. Sympathetic outflow is normally conducted by the amygdala (Hessl et al., 2007). Interestingly, intranuclear inclusions are also present in neurons and astrocytes in the amygdala in humans (Louis et al., 2006). Dysfunction of the amygdala through elevated FMR1 mRNA levels and inclusion formation might play a role in the etiology of psychological symptoms involving emotion and social cognition as well. The presence of inclusions had not been investigated in our previous studies, but now we demonstrate significant numbers of intranuclear neuronal inclusions in amygdala of CGG mice of 100 weeks of age (figure 5). It is unclear why amygdala response is reduced in humans while corticosterone levels are elevated in CGG mice. For human brain, it is as yet unknown when inclusions first develop, since no post mortem material has been available of relatively young patients. It should be noted that the mean age of subjects tested in the study by Hessl and co-workers (Hessl et al., 2007) was lower (~43 years) than the age at which inclusions have been seen thus far (Greco et al., 2006). Around 40 years of age in a human life might be comparable to about 25 weeks of age in mice, thus it could be that reduced limbic response and elevation of corticosteroid levels are different stages of the same syndrome.

Fragile X individuals (Hessl et al., 2002; Hessl et al., 2006), as well as Fmr1 KO mice (Markham et al., 2006), have also been shown to have an exaggerated stress response. Children with the fragile X full mutation have elevated cortisol levels which are associated with severity of behavioral problems (Hessl et al., 2002; Hessl et al., 2006). Both fragile X patients and Fmr1 KO mice have a delayed return to baseline glucocorticoid levels, which was explained by the normal binding of GR mRNA to FMRP (Miyashiro et al., 2003). Fragile X individuals and Fmr1 KO mice do not express FMRP, thus in the absence of FMRP inappropriate transport or translation of GR could lead to altered HPA responsiveness (Markham et al., 2006). Mice with CGG-repeats shorter than 170 trinucleotides have close to normal Fmrp levels (figure 1). In our study, corticosterone levels did not correlate with repeat length in the range tested (100-170 CGGs). Also, the 25-week old mice tested had higher CGG-repeat lengths (170-200 CGGs) and lower Fmrp levels, but they did not have elevated corticosterone levels, indicating that lower Fmrp levels did not lead to inappropriate GR expression. Thus elevated stress responses develop differently in fragile X individuals and Fmr1 KO mice as compared to CGG mice. Although representing different molecular genetic mechanisms, these prior studies document the impact of FMR1 gene mutation on the HPA axis. It should be noted that the decreased levels of Fmrp in animals with >170 CGGs do not represent a uniform decrease in cellular Fmrp throughout the brain. We have previously shown that some brain areas had very low Fmrp expression, while in other areas Fmrp levels were closer to normal (Brouwer et al., 2007).

Since we measured corticosterone levels only at one time point after a mild stressor, we cannot draw conclusions on the course of the corticosterone response over time. It is not yet known whether corticosterone levels in CGG mice return to baseline levels in a normal or delayed fashion, or whether peak stress levels are higher than in controls. Our future study will therefore focus on investigating corticosterone levels at different time points after a mild stressor.

It is intriguing that in different organs in the HPA axis ubiquitin-positive inclusions are observed, despite their different cell types. Within these organs, specific cells appear to be particularly prone to inclusion formation, for instance the chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla. This, however, gives no clue as to why corticosterone levels are elevated in CGG mice. The observation that there are much fewer and smaller intranuclear inclusions at 25 weeks than at 100 weeks of age and no difference in corticosterone levels at 25 weeks suggests that inclusions have a role in the origin of elevated corticosterone levels. Dysregulation of the HPA axis might arise at any of the organs involved. Although based on our current observations we cannot unravel the mechanism underlying the aberrant HPA axis physiology and its relation to the inclusions observed in CGG mice, we do believe that this is an important observation in view of the emerging evidence of psychiatric symptoms in PM carriers. A combination of clinical and animal research is likely to lead to answering questions on the origin of the psychopathology observed in PM carriers, which may ultimately lead to novel therapeutic strategies. A first step into this direction is to determine basal salivary cortisol and cortisol stress response in PM carriers with and without FXTAS.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. ER de Kloet and Claudia Greco for helpful discussion and to Ruud Koppenol and Tom de Vries Lentsch for graphical support. We thank Ronald van der Wal for measurement of corticosterone levels and Elisabeth Lodder and Josien Levenga for assistance with statistical analyses. This study was financially supported by the Prinses Beatrix Fonds (JB) and by the National Institutes of Health (UL1 RR024922; RL1 NS062411) (RW) and ROI HD38038 (BAO).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosures

We declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguilera G. Factors controlling steroid biosynthesis in the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1993;45:147–151. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90134-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera G. Regulation of Pituitary ACTH Secretion during Chronic Stress. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 1994;15:321–350. doi: 10.1006/frne.1994.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacalman S, Farzin F, Bourgeois JA, Cogswell J, Goodlin-Jones BL, Gane LW, Grigsby J, Leehey MA, Tassone F, Hagerman RJ. Psychiatric Phenotype of the Fragile X-Associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome (FXTAS) in Males: Newly Described Fronto-Subcortical Dementia. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2006;67:87–94. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker CE, de Diego Otero Y, Bontekoe C, Raghoe P, Luteijn T, Hoogeveen AT, Oostra BA, Willemsen R. Immunocytochemical and biochemical characterization of FMRP, FXR1P, and FXR2P in the mouse. Exp. Cell. Res. 2000;258:162–170. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontekoe CJ, Bakker CE, Nieuwenhuizen IM, van Der Linde H, Lans H, de Lange D, Hirst MC, Oostra BA. Instability of a (CGG)(98) repeat in the Fmr1 promoter. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1693–1699. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois JA, Cogswell JB, Hessl D, Zhang L, Ono MY, Tassone F, Farzin F, Brunberg JA, Grigsby J, Hagerman RJ. Cognitive, anxiety and mood disorders in the fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2007;29:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer JR, Mientjes EJ, Bakker CE, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Severijnen LA, Van der Linde HC, Nelson DL, Oostra BA, Willemsen R. Elevated Fmr1 mRNA levels and reduced protein expression in a mouse model with an unmethylated Fragile X full mutation. Exp. Cell. Res. 2007;313:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF. Fast glucocorticoid actions on brain: Back to the future. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2005;26:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF, Akana SF, Levin N, Walker CD, Bradbury MJ, Suemaru S, Scribner KS. Corticosteroids and the control of function in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1994;746:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb39206.x. discussion 31-22, 64-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzin F, Perry H, Hessl D, Loesch D, Cohen J, Bacalman S, Gane L, Tassone F, Hagerman P, Hagerman R. Autism spectrum disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in boys with the fragile X premutation. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2006;27:S137–144. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604002-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Richards S, Verkerk AJ, Holden JJ, Fenwick RG, Jr., Warren ST, et al. Variation of the CGG repeat at the fragile X site results in genetic instability: resolution of the Sherman paradox. Cell. 1991;67:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel LA, Won S, Kawai H, McKinney M, Tartakoff AM, Fallon JR. Visual Experience Regulates Transient Expression and Dendritic Localization of Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:10579–10583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2185-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco CM, Soontrapornchai K, Wirojanan J, Gould JE, Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ. Testicular and pituitary inclusion formation in fragile X associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. J. Urol. 2007;177:1434–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco CM, Hagerman RJ, Tassone F, Chudley AE, Del Bigio MR, Jacquemont S, Leehey M, Hagerman PJ. Neuronal intranuclear inclusions in a new cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome among fragile X carriers. Brain. 2002;125:1760–1771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco CM, Berman RF, Martin RM, Tassone F, Schwartz PH, Chang A, Trapp BD, Iwahashi C, Brunberg J, Grigsby J, Hessl D, Becker EJ, Papazian J, Leehey MA, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. Neuropathology of fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) Brain. 2006;129:243–255. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. The fragile X premutation: into the phenotypic fold. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2002;12:278–283. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, Leehey M, Heinrichs W, Tassone F, Wilson R, Hills J, Grigsby J, Gage B, Hagerman PJ. Intention tremor, parkinsonism, and generalized brain atrophy in male carriers of fragile X. Neurology. 2001;57:127–130. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessl D, Glaser B, Dyer-Friedman J, Reiss AL. Social behavior and cortisol reactivity in children with fragile X syndrome. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 2006;47:602–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessl D, Glaser B, Dyer-Friedman J, Blasey C, Hastie T, Gunnar M, Reiss A. Cortisol and behavior in fragile X syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:855. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessl D, Rivera S, Koldewyn K, Cordeiro L, Adams J, Tassone F, Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ. Amygdala dysfunction in men with the fragile X premutation. Brain. 2007;130:404–416. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessl D, Tassone F, Loesch DZ, Berry-Kravis E, Leehey MA, Gane LW, Barbato I, Rice C, Gould E, Hall DA, Grigsby J, Wegelin JA, Harris S, Lewin F, Weinberg D, Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ. Abnormal elevation of FMR1 mRNA is associated with psychological symptoms in individuals with the fragile X premutation. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2005;139B:115–121. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundscheid RD, Braat DD, Kiemeney LA, Smits AP, Thomas CM. Increased serum FSH in female fragile X premutation carriers with either regular menstrual cycles or on oral contraceptives. Hum. Reprod. 2001;16:457–462. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahashi CK, Yasui DH, An HJ, Greco CM, Tassone F, Nannen K, Babineau B, Lebrilla CB, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. Protein composition of the intranuclear inclusions of FXTAS. Brain. 2006;129:256–271. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemont S, Farzin F, Hall D, Leehey M, Tassone F, Gane L, Zhang L, Grigsby J, Jardini T, Lewin F, Berry-Kravis E, Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ. Aging in individuals with the FMR1 mutation. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2004;109:154–164. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2004)109<154:AIIWTF>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemont S, Hagerman RJ, Leehey M, Grigsby J, Zhang L, Brunberg JA, Greco C, Des Portes V, Jardini T, Levine R, Berry-Kravis E, Brown WT, Schaeffer S, Kissel J, Tassone F, Hagerman PJ. Fragile X Premutation Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome: Molecular, Clinical, and Neuroimaging Correlates. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:869–878. doi: 10.1086/374321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, Duan R, Qurashi A, Qin Y, Tian D, Rosser TC, Liu H, Feng Y, Warren ST. Pur alpha Binds to rCGG Repeats and Modulates Repeat-Mediated Neurodegeneration in a Drosophila Model of Fragile X Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome. Neuron. 2007;55:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenneson A, Zhang F, Hagedorn CH, Warren ST. Reduced FMRP and increased FMR1 transcription is proportionally associated with CGG repeat number in intermediate-length and premutation carriers. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:1449–1454. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis E, Moskowitz C, Friez M, Amaya M, Vonsattel JP. Parkinsonism, dysautonomia, and intranuclear inclusions in a fragile X carrier: A clinical-pathological study. Mov. Disord. 2006;27:193–201. doi: 10.1002/mds.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNaughton J, Banah M, McCloud P, Hee J, Burger H. Age related changes in follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, oestradiol and immunoreactive inhibin in women of reproductive age. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) 1992;36:339–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham JA, Beckel-Mitchener AC, Estrada CM, Greenough WT. Corticosterone response to acute stress in a mouse model of Fragile X syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:781–785. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill BE, Bundle SF, Yaylaoglu MB, Carson JP, Thaller C, Zoghbi HY. From the Cover: Enhanced anxiety and stress-induced corticosterone release are associated with increased Crh expression in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:18267–18272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608702103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashiro KY, Beckel-Mitchener A, Purk TP, Becker KG, Barret T, Liu L, Carbonetto S, Weiler IJ, Greenough WT, Eberwine J. RNA cargoes associating with FMRP reveal deficits in cellular functioning in Fmr1 null mice. Neuron. 2003;37:417–431. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M, Ogawa H, Ito T, Matsuda K-I, Kawata M. Dynamic Changes in Subcellular Localization of Mineralocorticoid Receptor in Living Cells: In Comparison with Glucocorticoid Receptor using Dual-Color Labeling with Green Fluorescent Protein Spectral Variants. Mol.Endocrinol. 2001;15:1077–1092. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.7.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M, Tanaka M, Matsuda K, Sunaguchi M, Kawata M. Visualization of Glucocorticoid Receptor and Mineralocorticoid Receptor Interactions in Living Cells with GFP-Based Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4918–4927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5495-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosser TC, Johnson TR, Warren ST. A cerebellar FMR1 riboCGG binding protein. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71:507. [Google Scholar]

- Saland LC. The mammalian pituitary intermediate lobe: an update on innervation and regulation. Brain. Res. Bull. 2001;54:587–593. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SL. Premature ovarian failure in the fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000;97:189–194. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200023)97:3<189::AID-AJMG1036>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofola OA, Jin P, Qin Y, Duan R, Liu H, de Haro M, Nelson DL, Botas J. RNA-Binding Proteins hnRNP A2/B1 and CUGBP1 Suppress Fragile X CGG Premutation Repeat-Induced Neurodegeneration in a Drosophila Model of FXTAS. Neuron. 2007;55:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan AK, Marcus M, Epstein MP, Allen EG, Anido AE, Paquin JJ, Yadav-Shah M, Sherman SL. Association of FMR1 repeat size with ovarian dysfunction. Hum. Reprod. 2005;20:402–412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Iwahashi C, Hagerman PJ. FMR1 RNA withinthe intranuclear inclusions of fragile X-associated Tremor/Ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) RNA biology. 2004;1:103–105. doi: 10.4161/rna.1.2.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Chamberlain WD, Hagerman PJ. Transcription of the FMR1 gene in individuals with fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000a;97:195–203. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200023)97:3<195::AID-AJMG1037>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Taylor AK, Gane LW, Godfrey TE, Hagerman PJ. Elevated levels of FMR1 mRNA in carrier males: A new mechanism of involvement in the Fragile-X syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000b;66:6–15. doi: 10.1086/302720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Beilina A, Carosi C, Albertosi S, Bagni C, Li L, Glover K, Bentley D, Hagerman PJ. Elevated FMR1 mRNA in premutation carriers is due to increased transcription. RNA. 2007;13:555–562. doi: 10.1261/rna.280807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Reichardt HM, Schutz G. Genetic dissection of glucocorticoid receptor function in mice. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1998;8:532–538. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam D, Errijgers V, Kooy RF, Willemsen R, Mientjes E, Oostra BA, De Deyn PP. Cognitive decline, neuromotor and behavioural disturbances in a mouse model for Fragile-X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) Behav. Brain Res. 2005;162:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenema AH, Meijer OC, de Kloet ER, Koolhaas JM, Bohus BG. Differences in basal and stress-induced HPA regulation of wild house mice selected for high and low aggression. Horm. Behav. 2003;43:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(02)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk AJ, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, Reiner O, Richards S, Victoria MF, Zhang FP, Eussen BE, Van Ommen GJB, Blonden LAJ, Riggins GJ, Chastain JL, Kunst CB, Galjaard H, Caskey CT, Nelson DL, Oostra BA, Warren ST. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991;65:905–914. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90397-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JC, Cidlowski JA. Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid-receptor-mediated Repression of Gene Expression. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;10:396–402. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welt CK, Smith PC, Taylor AE. Evidence of early ovarian aging in fragile X premutation carriers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;89:4569–4574. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen R, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Reis S, Holstege J, Severijnen LA, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Schrier M, VanUnen L, Tassone F, Hoogeveen AT, Hagerman P, Mientjes E, Oostra BA. The FMR1 CGG repeat mouse displays ubiquitin-positive intranuclear neuronal inclusions; implications for the cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:949–959. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]