Abstract

Individuals experience reward not only when directly receiving positive outcomes (e.g., food or money), but also when observing others receive such outcomes. This latter phenomenon, known as vicarious reward, is a perennial topic of interest among psychologists and economists. More recently, neuroscientists have begun exploring the neuroanatomy underlying vicarious reward. Here we present a quantitative whole-brain meta-analysis of this emerging literature. We identified 25 functional neuroimaging studies that included contrasts between vicarious reward and a neutral control, and subjected these contrasts to an activation likelihood estimate (ALE) meta-analysis. This analysis revealed a consistent pattern of activation across studies, spanning structures typically associated with the computation of value (especially ventromedial prefrontal cortex) and mentalizing (including dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and superior temporal sulcus). We further quantitatively compared this activation pattern to activation foci from a previous meta-analysis of personal reward. Conjunction analyses yielded overlapping VMPFC activity in response to personal and vicarious reward. Contrast analyses identified preferential engagement of the nucleus accumbens in response to personal as compared to vicarious reward, and in mentalizing-related structures in response to vicarious as compared to personal reward. These data shed light on the common and unique components of the reward that individuals experience directly and through their social connections.

Keywords: vicarious reward, positive empathy, empathy, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, meta-analysis, activation likelihood estimation

Humans are physically separate, but psychologically intertwined. Empathy—the ability to share and understand others’ internal states—intimately connects us, such that we “co-experience” the feelings of those around us. Empathy often involved sharing others’ pain and suffering, but applies equally to our sharing of others’ positive states. Adam Smith, whose Theory of Moral Sentiments (1790/2002) paved the way for modern theories of empathy, recognized such positive empathy. Smith even suggested that people could re-ignite their enjoyment of, for instance, theater performances by capitalizing on shared enjoyment with others who had not seen these performances before:

We enter into the surprise and admiration which it naturally excites in him, but which it is no longer capable of exciting in us… and we are amused by sympathy with his amusement which thus enlivens our own. (Pg. 9)

Although not the center of empathy research, positive empathy has received increasing attention for years (Batson et al., 1991; Gable & Reis, 2010; Morelli, Lieberman, Telzer, & Zaki, under review; Morelli, Lieberman, & Zaki, in press; K. D. Smith, Keating, & Stotland, 1989). Scientists have demonstrated, for instance, that other-reported positive empathy tracks the health of close relationships (Gable, 2006). Further, individuals reap psychological rewards from their own prosocial behaviors, reporting higher degrees of happiness after acting prosocially, as compared to selfishly (Dunn, Aknin, & Norton, 2014). Indices of positive empathy track individuals’ tendency to engage in prosocial behaviors, which suggests that positive empathy plays a functional role in driving generosity (Harbaugh, Mayr, & Burghart, 2007; Mobbs et al., 2009; Morelli et al., in press; Zaki & Mitchell, 2013). Finally, neuroimaging studies suggest that individuals may share the positive emotional and bodily states of others during positive empathy (Jabbi, Swart, & Keysers, 2007; Mobbs et al., 2009; Morelli, Rameson, & Lieberman, 2014; Perry, Hendler, & Shamay-Tsoory, 2012).

Thus, positive empathy appears to foster both prosociality and personal well-being. That said, a number of key questions about this phenomenon remain unanswered. Recent theoretical models suggest that empathy involves experience sharing (i.e., vicariously sharing targets’ internal states), mentalizing (i.e., explicitly considering and potentially understanding others’ emotional states), and motivation to help others (Davis, 1994; Singer & Klimecki, 2014; Zaki, 2014; Zaki & Ochsner, 2012). However, the psychological structure of this first process – vicarious positive affect— remains at least partially unclear. In particular, to what extent does vicarious enjoyment share affective mechanisms with “personal” reward (i.e., positive events that occur to the self)? Neuroscientific data provide a powerful lens through which to examine this question. In particular, scientists have robustly characterized the brain systems underlying positive affect, and reward processing in particular (Knutson, Taylor, Kaufman, Peterson, & Glover, 2005; Liu, Hairston, Schrier, & Fan, 2011). This literature suggests ways in which personal and vicarious reward might both overlap and dissociate.

On the one hand, the experience of valuable outcomes reliably engages neural structures such as ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) and nucleus accumbens (NAcc). These responses, especially in VMPFC, (i) track the subjective value that individuals associate with outcomes (Bartra, McGuire, & Kable, 2013), (ii) occur irrespective of the particular qualities of rewarding stimuli (Chib, Rangel, Shimojo, & O’Doherty, 2009; D. J. Levy & Glimcher, 2011), and (iii) occur even when rewards are not the result of specific actions (I. Levy, Lazzaro, Rutledge, & Glimcher, 2011; Wunderlich, Rangel, & O’Doherty, 2010). As such, these regions might be expected to respond even to rewarding events that occur to others. Indeed, several studies have identified brain activity in NAcc and VMPFC that track a number of classes of “social rewards” (Fehr & Camerer, 2007; Sanfey, 2007). These include positive evaluation by or consensus with others (Izuma, Saito, & Sadato, 2008; Izuma, Saito, & Sadato, 2010; Klucharev, Hytonen, Rijpkema, Smidts, & Fernandez, 2009; Zaki, Schirmer, & Mitchell, 2011), acting prosocially (Dawes et al., 2012; de Quervain et al., 2004; Moll et al., 2006; Zaki & Mitchell, 2011), observing behaviors that conform to social norms such as equity and reciprocity (Rilling et al., 2002; Tricomi, Rangel, Camerer, & O’Doherty, 2010) and—crucially—observing others receiving rewarding outcomes (Hare, Camerer, Knoepfle, & Rangel, 2010a; Mobbs et al., 2009; Morelli et al., 2014; Zaki, Lopez, & Mitchell, 2014). As such, one might expect vicarious and personal reward to resemble each other in these key structures.

By contrast, other brain structures are strong candidates for dissociation between these reward-types. Two such examples bear emphasis. First, dorsal striatum often responds to rewarding events, but in a manner specific to decision-making and action planning (Rangel & Hare, 2010; Rushworth, Noonan, Boorman, Walton, & Behrens, 2011). Second, vicarious sharing of others’ rewards often requires understanding the extent to which others value a particular outcome, especially when observers and social targets’ preferences diverge. For instance, an ice cream-loving observer can simply savor frozen desserts themselves, but might need to engage in mentalizing—or inferences about others’ mental states. Mentalizing produces activity in a system of brain regions including dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), temporoparietal junction (TPJ), posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) involved more broadly in projecting one’s self outside of the present moment and location (Buckner & Carroll, 2007; Lieberman, 2010; Mitchell, 2009; Spreng, Mar, & Kim, 2009; Zaki & Ochsner, 2012). To the extent that vicarious, but not personal, reward involves mentalizing, these regions might be engaged preferentially by vicarious reward.

Over the last 10 years, the neuroscientific study of vicarious reward has experienced considerable growth, and in many cases supported the foregoing predictions. Here, we take a step towards more formally organizing this information through a quantitative, whole-brain, coordinate-based meta-analysis. Specifically, we employed an activation likelihood estimate (ALE) meta-analysis, surveying 25 functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies that included contrasts between vicarious reward and a neutral control condition. We then quantitatively compared the results of this analysis (i.e., patterns of brain activity consistently associated with vicarious reward) to the results of a recent meta-analysis of personal reward (Bartra et al., 2013). This allowed us to isolate brain regions that were common to both vicarious and personal reward, as well as regions preferentially engaged by each type of reward.

Materials and Methods

We conducted two coordinate-based meta-analyses of task-based fMRI studies of vicarious and personal reward in order to understand the spatial signature of activation foci for these two sets of studies. We also assessed the overlap and dissociation between vicarious and personal reward using conjunction and contrast analyses.

Study Selection for Vicarious Reward

We initially identified candidate studies by searching Google Scholar for combinations of key words including: “vicarious,” “reward,” “fMRI,” and “empathy.” We identified additional studies by examining papers that cited a seminal paper on vicarious reward (Mobbs et al., 2009). We further extended this corpus of studies to identify other studies that examined vicarious reward, but framed it as another phenomena (e.g., observational learning), and to catalogue various types of vicarious rewards (e.g., monetary, social, sensory, emotional). Thus, follow-up searches included terms including “observational learning,” “donation,” “win,” “gain,” “money,” “reputation,” “social reward,” “touch,” “taste,” “smell,” “happiness,” “joy,” and “positive” combined with the original search terms.

We selected a final set of studies for inclusion in our analysis using a number of criteria. We required that all studies employ fMRI to measure BOLD signal in healthy human adults. Further, studies qualified only if participants directly observed, imagined, or saw a cue indicating that another person received a reward outcome. Therefore, we excluded studies that focused on the anticipation of vicarious reward or simply depicted targets experiencing positive emotion (e.g., smiling faces). We also excluded any studies in which participants competed with, disliked, or envied the target receiving rewards (Cikara & Fiske, 2011; Dohmen, Falk, Fliessbach, Sunde, & Weber, 2011; Dvash, Gilam, Ben-Ze’ev, Hendler, & Shamay-Tsoory, 2010; Fareri & Delgado, 2014). We also did not include studies in which the participant and target shared rewarding outcomes (e.g., (Fareri, Niznikiewicz, Lee, & Delgado, 2012) so as not to confound personal and vicarious reward.

We also required that studies include whole-brain analysis comparing a vicarious reward condition to a neutral condition (e.g., no reward) or baseline (e.g., fixation), with the exception of one study that did not have a baseline condition (i.e., (Kätsyri, Hari, Ravaja, & Nummenmaa, 2013). Therefore, all region of interest (ROI) analyses were excluded. All included studies utilized a binary contrast (rather than a parametric or correlational analysis) statistically thresholded by the authors of the original papers. These studies included the observation of social targets experiencing a variety of reward types, including pleasant touch, tastes, and smells, monetary payoffs, positive social feedback (e.g., praise), and positive emotional events (e.g., getting engaged). Social distance between the participant and target varied across studies, ranging from strangers (Morelli et al., 2014) to friends and ingroup members (e.g., (Braams et al., 2013; Molenberghs et al., 2014; Varnum, Shi, Chen, Qiu, & Han, 2014) to family (Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman, & Galván, 2013; Telzer, Masten, Berkman, Lieberman, & Fuligni, 2010).

Because many studies did not report coordinates from whole-brain contrasts of vicarious reward compared to control conditions in published tables, we obtained the remaining included contrasts from personal correspondence with study authors (when possible). However, not all authors could supply their whole-brain coordinates (Albrecht, Volz, Sutter, Laibson, & Von Cramon, 2010; Albrecht, Volz, Sutter, & von Cramon, 2013; Canessa, Motterlini, Alemanno, Perani, & Cappa, 2011; Canessa et al., 2009; Cooper, Dunne, Furey, & O’Doherty, 2012; Harbaugh et al., 2007; Kawamichi et al., 2013; Mitchell, Schirmer, Ames, & Gilbert, 2011; Mobbs et al., 2009; Moll et al., 2006; Suzuki et al., 2012). For all included publications, we selected the most relevant contrast from the study. However, one publication included two separate studies (Morrison, Björnsdotter, & Olausson, 2011), so we selected one contrast from each study. Thus, the final set of 24 publications included a total of 25 studies, 25 analysis contrasts, 575 participants, and 358 activation foci. See Appendix A for a full list of included studies, task descriptions, reward stimuli, and contrasts.

Study Selection for Personal Reward

Drawing from a recent meta-analysis on subjective value (Bartra et al., 2013), we selected studies that closely paralleled the criteria used for vicarious reward contrasts. As a first step, we queried an online database created by Bartra and colleagues (http://kl.rewardstudies.appspot.com/) for studies demonstrating a positive effect of reward outcomes. This query produced a list of 79 studies including the sample size and coordinates (in MNI space) for each study. Using additional study information provided by the authors, we then selected studies from this initial list that included whole-brain binary contrasts comparing reward outcomes to no reward control conditions. Therefore, we excluded studies with (a) only region of interest (ROI) analyses, (b) parametric or correlational analyses, or (c) contrasts comparing relatively larger rewards to smaller rewards. We also excluded any studies that might involve vicarious reward – such as erotic pictures, happy faces, and shared reward outcomes. Resulting contrasts included several reward types, including primary rewards (e.g., food, drinks), monetary payoffs, and positive feedback. The final set of 42 studies (Appendix B) included a total of 42 analysis contrasts, 805 participants, and 495 activation foci.

ALE Analyses

Basic Meta-Analyses

We conducted meta-analyses of both vicarious and personal reward using the Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE) algorithm (version 2.3) (Eickhoff, Bzdok, Laird, Kurth, & Fox, 2012; Eickhoff et al., 2009; Turkeltaub et al., 2012) in MNI space. We converted any coordinates originally reported in Talairach space to MNI space. According to the ALE method, significant coordinates for a given study were represented as three-dimensional Gaussian probability distributions. The Gaussian distribution widths represent spatial uncertainty associated with neuroimaging results (e.g., that may result from sample size). Computing the voxel-wise union of these probability distributions across voxels resulted in a modeled activation (MA) map for each study. The MA map can be conceptualized as a summary of that study, mapping the likelihood that a veridical activation exists in any given voxel. Aggregation of the MA maps across studies produced an ALE map for vicarious reward, as well as personal reward. We then assessed voxel-wise spatial convergence across studies with permutation-based statistics. Specifically, voxel-wise ALE values were compared to a null distribution that did not exhibit spatial contingency. A single value in this null distribution was created by randomly spatially sampling each MA map once, and then taking the union of the resulting values. This process was then repeated to create a null distribution.

Original ALE values were then compared to the null distribution to calculate a p-value per voxel. Specifically, each voxel-wise p-value was computed by dividing the number of values in the null distribution greater than or equal to the given ALE value at that voxel by the total number of values in the null distribution. In order to correct for false positive inflation as a result of multiple comparisons from a statistical test at each voxel, we used a cluster-level correction that compared significant cluster sizes in the original data to cluster sizes in ALE maps generated from 10,000 sets of randomly distributed foci. We implemented a cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05, and a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.01. The resulting clusters represented regions that exhibit non-random spatial convergence across the studies included in each meta-analysis (i.e., for vicarious or personal reward).

Overlap Analysis

To assess brain regions related to both vicarious and personal reward, we conducted a minimum-statistic conjunction analysis (Caspers, Zilles, Laird, & Eickhoff, 2010; Kurth, Zilles, Fox, Laird, & Eickhoff, 2010). This analysis assessed the intersection of statistically thresholded (i.e., cluster corrected) ALE-maps for vicarious and personal reward (with matched statistical parameters, described above).

Contrast Analyses

To identify brain regions that differentially related to vicarious versus personal reward, we conducted ALE contrast analyses (Eickhoff et al., 2011). Differences were computed at each voxel between statistically thresholded vicarious reward and personal reward ALE maps. These difference values were then compared, on a voxel-wise basis, to a null distribution at each voxel. This null distribution reflected ALE scores from datasets in which the group for a given set of study coordinates (i.e., vicarious or personal reward) was shuffled. New group datasets retained the size of the initial groups. ALE difference maps were then iteratively created for each shuffled dataset, creating a volume of null distributions. The input maps for the contrast analyses are described above for the single-study ALE meta-analyses and used a cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05 and a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.01. In order to correct for multiple comparisons in the statistical difference map, we additionally used a conservative, whole-brain FDR correction of p < 0.01 (pID) and cluster extent of 128 mm3 (Laird et al., 2005). The cluster extent value was computed based on the minimum volume that would guarantee at least one significant voxel in a given cluster. ALE contrast analysis thus allowed for the assessment of brain regions that were associated with vicarious reward more than personal reward, and personal reward more than vicarious reward.

GingerALE’s contrast analysis relies on a permutation null-distribution created from difference maps computed from uneven groups with the same size as the original groups. Thus, the current results should be robust to uneven group size in the original meta-analyses. Extreme group size differences can still lead to unreliable results when (1) the size difference between two sets of studies is more than four-fold and (2) the smaller group has less than 12 experiments. However, our meta-analysis of vicarious reward (i.e. smaller group) includes 25 studies. The size difference between the vicarious and personal reward meta-analysis is less than two-fold (i.e., 25 vs. 42 studies). Thus, our contrast analysis should still be robust against the uneven number of studies.

Results

All analyses referred to in this section can be accessed at http://neurovault.org/collections/73/. We used Connectome Workbench to visualize ALE results on three-dimensional cortical renderings and coronal slices using a standard MNI brain (Marcus et al., 2011).

Vicarious Reward Meta-Analysis

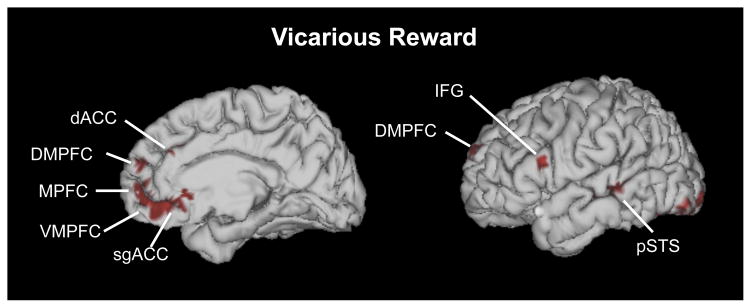

Our meta-analysis of vicarious reward revealed consistent activation foci across 25 studies in ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS), and amygdala, as well as the inferior parietal lobule (IPL), anterior insula (AI), dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC), and other areas (Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Brain areas activated by vicarious reward across 25 studies

Table 1.

Brain areas activated by vicarious reward as identified using ALE meta-analysis

| Region | Size | L/R | x | y | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | 2752 | R | 2 | 36 | −14 |

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | 0 | 50 | −12 | ||

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | 0 | 44 | −16 | ||

| Medial prefrontal cortex | 0 | 58 | −6 | ||

| Medial prefrontal cortex | 2128 | R | 6 | 58 | 14 |

| Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex | L | −6 | 60 | 24 | |

| Posterior superior temporal sulcus | 880 | R | 56 | −32 | −4 |

| Middle temporal gyrus | R | 60 | −38 | −8 | |

| Posterior superior temporal sulcus | 2136 | L | −62 | −38 | 2 |

| Posterior superior temporal sulcus | L | −52 | −36 | 0 | |

| Posterior superior temporal sulcus | L | −60 | −28 | 0 | |

| Middle temporal gyrus | L | −60 | −20 | −6 | |

| Amygdala | 736 | R | 24 | −6 | −10 |

| Amygdala | 976 | L | −18 | −10 | −14 |

| Hippocampus | L | −10 | 0 | −12 | |

| Anterior insula | 1816 | L | −30 | 8 | −10 |

| Anterior insula | L | −34 | 16 | −2 | |

| Putamen | L | −28 | 8 | −4 | |

| Inferior parietal lobule | 2232 | R | 38 | −62 | 44 |

| Inferior parietal lobule | R | 30 | −72 | 38 | |

| Inferior parietal lobule | R | 46 | −56 | 38 | |

| Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex | 1392 | R | 12 | 28 | 26 |

| Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex | R | 12 | 36 | 20 | |

| Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex | R | 4 | 38 | 24 | |

| Subgenual anterior cingulate cortex | 808 | L | −2 | 24 | −6 |

| Subgenual anterior cingulate cortex | L | −2 | 24 | −14 | |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | 960 | L | −38 | 18 | 22 |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | −54 | 18 | 20 | |

| Superior parietal lobule | 1064 | L | −28 | −62 | 44 |

| Parietal lobule | L | −34 | −68 | 38 | |

| Supplementary motor area | 680 | L | −8 | 10 | 62 |

| Fusiform gyrus | 1112 | L | −40 | −70 | −18 |

| Fusiform gyrus | L | −44 | −58 | −18 | |

| Superior temporal gyrus | 808 | L | −32 | 0 | −22 |

| Thalamus | 744 | L | −22 | −30 | −2 |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | 2528 | L | −26 | −96 | −8 |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | L | −42 | −86 | −12 | |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | L | −30 | −90 | −16 | |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | 1856 | R | 36 | −90 | −4 |

| Inferior occipital gyrus | R | 24 | −94 | −6 | |

| Middle occipital gyrus | R | 34 | −88 | 16 |

Notes. We used a cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05, with a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.01. Peaks are listed first for each cluster with subpeaks listed in subsequent rows.

Personal Reward Meta-Analysis

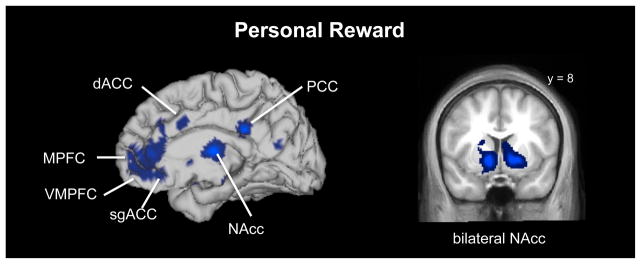

We included a personal reward meta-analysis primarily as a tool for examining similarities and differences between personal and vicarious reward. This meta-analysis largely replicated the findings of the original paper on personal reward (Bartra et al., 2013). In particular, this analysis revealed significant clusters in VMPFC, bilateral NAcc, bilateral ventral tegmental area (VTA), and bilateral amygdala. (Figure 2; Table 2). In addition, significant peaks and subpeaks appeared in MPFC, posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), AI, dACC, sgACC, and other areas. The consistency in these results and those presented by Bartra et al. (2013) suggested that we could reliably use this data for the ALE conjunction and contrast analyses.

Figure 2.

Brain areas activated by personal reward across 42 studies

Table 2.

Brain areas activated by personal reward as identified using ALE meta-analysis

| Region | Size | L/R | x | y | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial prefrontal cortex | 10320 | 0 | 56 | 0 | |

| Medial prefrontal cortex | 0 | 48 | −2 | ||

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | 0 | 56 | −14 | ||

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | R | 4 | 42 | −16 | |

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | 0 | 32 | −14 | ||

| Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex | R | 2 | 38 | 26 | |

| Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex | R | 4 | 32 | 14 | |

| Rostral anterior cingulate cortex | R | 2 | 38 | 2 | |

| Nucleus accumbens | 9944 | R | 12 | 10 | −6 |

| Caudate nucleus | R | 12 | 18 | 2 | |

| Caudate | R | 18 | 12 | 16 | |

| Putamen | R | 26 | 18 | −4 | |

| Amygdala | R | 20 | −2 | −16 | |

| Nucleus accumbens | 20904 | L | −12 | 12 | −6 |

| Caudate | L | −14 | 28 | 0 | |

| Amygdala | L | −16 | −2 | −14 | |

| Anterior insula | L | −30 | 22 | 0 | |

| Anterior insula | L | −38 | 20 | −12 | |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | −42 | 28 | −6 | |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | −40 | 34 | 8 | |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | −44 | 38 | −2 | |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | L | −46 | 32 | 0 | |

| Thalamus | 0 | −10 | 10 | ||

| Thalamus | L | −12 | −12 | 8 | |

| Thalamus | R | 22 | −12 | 14 | |

| Thalamus | R | 16 | −6 | 12 | |

| Ventral tegmental area | 1864 | R | 6 | −24 | −14 |

| Ventral tegmental area | L | −2 | −22 | −18 | |

| Posterior cingulate | 1792 | 0 | −32 | 30 | |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | 2744 | R | 32 | 30 | −18 |

| Anterior insula | R | 34 | 18 | −18 | |

| Pons | L | −4 | −28 | −20 | |

| Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex | 1104 | R | 6 | 20 | 30 |

| Cuneus | 1344 | R | 4 | −62 | 20 |

| Cuneus | R | 12 | −68 | 10 | |

| Posterior cingulate | R | 6 | −52 | 22 |

Notes. We used a cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05, with a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.01. Peaks are listed first for each cluster with subpeaks listed in subsequent rows.

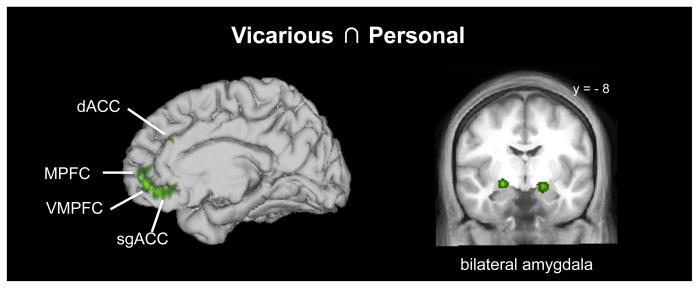

Overlap Between Vicarious and Personal Reward

An ALE conjunction analysis revealed overlap between personal and vicarious reward in a number of structures including VMPFC, MPFC, and bilateral amygdala, as well as AI, dACC, sgACC, and other areas (Figure 3; Table 3).

Figure 3.

Brain areas commonly activated by both vicarious and personal reward

Table 3.

Brain areas commonly activated by vicarious and personal reward as identified using ALE conjunction analysis

| Region | Size | L/R | x | y | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | 2128 | 0 | 34 | −14 | |

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | 0 | 52 | −12 | ||

| Ventromedial prefrontal cortex | R | 2 | 40 | −14 | |

| Medial prefrontal cortex | 0 | 58 | −6 | ||

| Amygdala | 56 | R | 22 | −6 | −14 |

| Amygdala | 568 | L | −18 | −8 | −14 |

| Putamen | 272 | L | −26 | 8 | −6 |

| Anterior insula | 200 | L | −30 | 18 | −2 |

| Anterior insula | 8 | L | −34 | 10 | −14 |

| Hippocampus | L | −10 | 0 | −12 | |

| Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex | 120 | R | 4 | 38 | 24 |

| Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex | 16 | R | 12 | 24 | 28 |

| Subgenual anterior cingulate cortex | 24 | R | 0 | 28 | −14 |

Notes. Both input images were cluster-level thresholded at p < 0.05, with a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.01. Peaks are listed first for each cluster with subpeaks listed in subsequent rows.

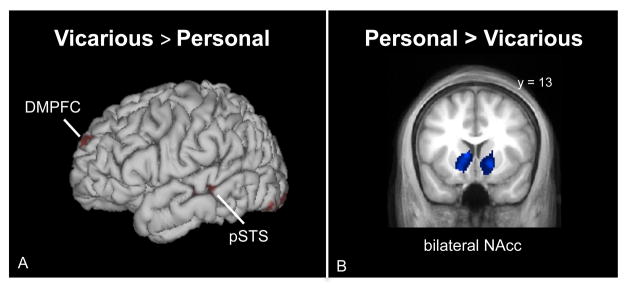

Dissociations Between Vicarious and Personal Reward

A number of regions distinguished between vicarious and personal reward. In particular, vicarious reward, as compared to personal reward, preferentially activated DMPFC and pSTS (Figure 4A; Table 4). In contrast, personal reward, as compared to vicarious reward, preferentially activated bilateral NAcc and other areas (Figure 4B; Table 4).

Figure 4.

Brain areas activated more by (a) vicarious reward than personal reward and (b) personal reward than vicarious reward.

Table 4.

Brain areas activated more by (a) vicarious reward than personal reward and (b) personal reward than vicarious reward in ALE contrast analyses

| Region | Size | L/R | x | y | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vicarious Reward > Personal Reward | |||||

| Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex | 536 | L | −12 | 61 | 26 |

| Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex | L | −14 | 56 | 26 | |

| Middle temporal gyrus | 672 | L | −58 | −20 | −4 |

| Posterior superior temporal sulcus | L | −60 | −27 | −1 | |

| Angular gyrus | 128 | L | −30 | −60 | 40 |

| Cerebellum | 1832 | L | −28 | −90 | −16 |

| Cerebellum | L | −33 | −89 | −17 | |

| Cerebellum | L | −22 | −90 | −18 | |

| Fusiform gyrus | L | −24 | −92 | −11 | |

| Fusiform gyrus | L | −40 | −84 | −12 | |

| Fusiform gyrus | L | −30 | −94 | −12 | |

| Superior occipital gyrus | 1096 | R | 32 | −64 | 40 |

| Middle occipital gyrus | R | 32 | −70 | 36 | |

| Middle occipital gyrus | 256 | R | 39 | −87 | 11 |

| Middle occipital gyrus | R | 34 | −90 | 12 | |

| Personal Reward > Vicarious Reward | |||||

| Nucleus accumbens | 2712 | R | 15 | 17 | −5 |

| Nucleus accumbens | R | 12 | 16 | −14 | |

| Caudate | R | 12 | 24 | 6 | |

| Caudate | R | 16 | 19 | 8 | |

| Thalamus | 7568 | L | −6 | −10 | 11 |

| Thalamus | R | 8 | −10 | 12 | |

| Thalamus | R | 14 | −6 | 14 | |

| Nucleus accumbens | L | −9 | 5 | 1 | |

| Nucleus accumbens | L | −14 | 13 | −7 | |

| Caudate | L | −6 | 10 | 18 | |

| Inferior frontal gyrus | 264 | R | 38 | 24 | −10 |

Notes. The input maps for the contrast analyses are described above for the single-study ALE meta-analyses and used a cluster-level threshold of p < 0.05 and a cluster-forming threshold of p < 0.01. In order to correct for multiple comparisons in the statistical difference map, we additionally used a conservative, whole-brain FDR correction of p < 0.01 (pID) and cluster extent of 128 mm3. Peaks are listed first for each cluster with subpeaks listed in subsequent rows.

Discussion

Positive empathy and vicarious reward are topics of widespread interest in psychology, economics, and—increasingly—neuroscience. Here we organize extant information about the neural structure of vicarious reward through a quantitative meta-analysis of neuroimaging data examining this phenomenon. We found that vicarious reward engages ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), a region commonly implicated in the computation of subjective value (Bartra et al., 2013; Hare, Camerer, Knoepfle, & Rangel, 2010b). This is consistent with both animal and human neuroscience suggesting that the VMPFC aggregates cues from multiple sensory modalities, along with contextual information about an organism’s current drives, to produce high-order representations of value. These representations, in turn, support decision-making even over seemingly incommensurate choices (Grabenhorst & Rolls, 2011; Izquierdo, Suda, & Murray, 2004; D. J. Levy & Glimcher, 2011; Strait, Blanchard, & Hayden, 2014). These data also fit with recent findings that the VMPFC is involved in computing value even when outcomes are decoupled from specific motor acts (Gläscher, Hampton, & O’Doherty, 2009; I. Levy et al., 2011). Our data demonstrate that VMPFC responds consistently not only when individuals receive valuable outcomes themselves, but also when they observe others receiving such outcomes. This suggests that the integrative value signal computed in VMPFC might be “person-invariant,” flexible not only with respect to the reward modality, but also the individual receiving that reward (cf. Zaki et al., 2014).

The personal and vicarious reward meta-analyses also showed overlap in the amygdalae, regions that are typically activated by motivationally relevant and emotionally impactful stimuli (Adolphs, 2010; Ewbank, Barnard, Croucher, Ramponi, & Calder, 2009; Lindquist, Wager, Kober, Bliss-Moreau, & Barrett, 2012). The amygdalae process emotional aspects of reward, such as valence (e.g., positive vs. negative) and relative value (e.g., small vs. large), and also update the value of expected outcomes in concert with the VMPFC (Gottfried, O’Doherty, & Dolan, 2003; Murray, 2007). Thus, the amygdalae’s response to both personal and vicarious reward could reflect the salience of rewarding stimuli for the self or for others. Although past work relates amygdala dysfunction to reduced empathy in psychopathy and autism spectrum disorders (Baron-Cohen et al., 2000; Blair, 2008), these findings suggest that vicarious reward, and positive empathy more broadly, may rely on the amygdala to generate affective responses to others’ positive outcomes.

We also document robust dissociations between vicarious and personal reward. One such difference is that, although personal reward consistently engaged NAcc, vicarious reward did not. This finding could occur for a number of reasons. First, we focused on reward outcomes, whereas NAcc activity is often instead linked to reward anticipation (Knutson, Fong, Adams, Varner, & Hommer, 2001) or reward prediction errors (comparisons of outcomes to expectations; e.g., Hare, O’Doherty, Camerer, Schultz, & Rangel, 2008). However, the personal reward meta-analysis we examined likewise compared rewarding and neutral outcomes, and did yield consistent engagement of NAcc in response to personal reward. This suggests that a focus on outcome alone does not explain the lack of NAcc activity in studies of vicarious reward.

Alternatively, personal rewards may activate the NAcc more strongly because they are a direct result of the participants’ action (Elliott, Newman, Longe, & William Deakin, 2004; Sescousse, Caldú, Segura, & Dreher, 2013; Zink, Pagnoni, Martin-Skurski, Chappelow, & Berns, 2004), whereas vicarious reward tasks typically involve passive observation of reward receipt. In fact, the majority of the studies in the vicarious reward meta-analysis did not directly involve the participant and only asked that participants observe others receive rewards – which may explain the lack of NAcc activation across studies. However, a few studies in this meta-analysis asked participants to win rewards for another person (Braams et al., 2013; Jung, Sul, & Kim, 2013; Varnum et al., 2014), linking participants’ direct actions to others’ rewarding outcomes. Due to the limited number of studies, however, we could not determine if vicarious reward tasks that involve direct action (vs. passive observation) increase NAcc activity during vicarious reward. Although we cannot resolve why personal reward engages NAcc more than vicarious reward, this comparison generates novel and interesting empirical predictions that can be explored in future research.

Vicarious reward could also lack psychological features that are (i) involved in personal reward and (ii) related to NAcc function. One such candidate is affective intensity. NAcc activity is often linked to the positive arousal, or excitement, that accompanies anticipating, learning about, and receiving rewards (Knutson, Katovich, & Suri, 2014; Rutledge, Skandali, Dayan, & Dolan, 2014). Such reactions often diminish with psychological distance, which renders cognitive and affective reactions more abstract (Fujita, Henderson, Eng, Trope, & Liberman, 2006; Tamir & Mitchell, 2011). Thus, an observer witnessing a target receive rewards might compute the value of those rewards as they would with personally received outcomes (e.g., in VMPFC), but not experience the same level of excitement they would upon receiving rewards themselves, thus diminishing activity in NAcc.

This idea, though speculative, dovetails with prior work. First, three studies have documented NAcc activity in response to watching socially close, but not distant, targets receive rewards (Braams et al., 2013; Mobbs et al., 2009; Varnum et al., 2014), consistent with the idea that stronger affective intensity might accompany vicarious reward in socially close contexts. Second, this effect resembles similar findings on empathy for pain. A recent meta-analysis in that domain (Lamm, Decety, & Singer, 2011) found overlap between vicarious and personal pain in areas associated with higher-order pain representations (e.g., anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula), but less consistent overlap in regions associated with perceptions of pain location and intensity. Our data suggest that vicarious reward might likewise include more abstract (e.g., valuation) psychological features of personal reward, but may not elicit positive arousal and increased NAcc activity when observing distant others receive rewards (Knutson et al., 2014). Future research should directly assess this prediction by examining whether self-reported positive arousal or excitement (i) distinguishes between personal and vicarious reward, and (ii) explains differential NAcc responses to these two phenomena.

Vicarious reward also produced consistent patterns of engagement not found in response to personal reward. Interestingly, this pattern included areas that are often associated with mentalizing (i.e., dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and posterior superior temporal sulcus) and mirroring (Mitchell, 2009; Puce & Perrett, 2003). As described above (see Introduction), this activity might represent a “layer” of inference necessary for vicarious, but not personal, reward: an observer’s decision as to whether outcomes are in fact valuable to social targets. When observer and target preferences diverge, this can be considered an affective analogue of a false belief task, because observers must simultaneously hold in mind both their and a target’s value representation. Interestingly, like classic false belief tasks (Saxe & Powell, 2006; Wellman, Cross, & Watson, 2001) reasoning about others’ preferences—especially when they are different from observers’ own—recruits activity in the inferior parietal lobe (Janowski, Camerer, & Rangel, 2012; Silani, Lamm, Ruff, & Singer, 2013). Further, one recent paper documented functional coupling between another region involved in mentalizing, the pSTS, and VMPFC in response to vicarious, but not personal reward (Hare et al., 2010b). These suggest that VMPFC commonly responds to vicarious and personal reward, but uniquely integrates information from regions involved in social cognition when processing vicarious reward. Our aggregated data across studies provides converging support for this idea.

Taken together, our analyses reveal several dissociations between personal and vicarious reward that warrant further exploration. In particular, thinking more deeply about why these differences occur can generate novel predictions and exciting new research directions. For example, future studies could explore exactly which features of vicarious reward might engage some parts of the “valuation network,” but not other parts of this network. Similarly, future work could examine whether some components of the mentalizing network serve a functionally distinct purpose during vicarious reward processing, while other regions might be generally responsive to mental state evaluation.

This meta-analysis surveys a burgeoning research enterprise, and as such is subject to certain limitations. In particular, the limited number of studies directly assessing vicarious reward meant that we did not have the power to explore patterns of activation specific to particular vicarious reward features, such as anticipation and prediction errors. Likewise, we are as of yet unable to formally dissociate between different classes of vicarious reward (e.g., watching others receive monetary versus primary rewards), levels of abstraction in vicarious reward cues, or social closeness as a moderator of vicarious reward. As the neuroscientific literature in this domain grows, scientists will be able to better parse the processes that constitute vicarious reward, and map each to potentially dissociable brain circuitry. Nonetheless, even at this early stage, our analyses demonstrate clear and theoretically compelling patterns of brain activity consistently associated with socially-mediated reward experiences.

Conclusions

The neuroscientific study of vicarious reward has grown quickly in recent years. Here we demonstrate consistency in patterns of brain activity that accompany the experience of vicarious reward. Like another recent meta-analysis examining vicarious and personal pain (Lamm et al., 2011), we document both overlap and dissociation between vicarious and personal reward. These data suggest inferences about the psychological structure of vicarious positive affect, and empathy more broadly.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We compare quantitative meta-analyses of personal and vicarious (vic.) reward.

Vic. reward studies activate regions related to value computation and mentalizing.

Vic. and personal reward studies commonly activate ventromedial PFC.

Personal as compared to vic. reward preferentially engages nucleus accumbens.

Vic. versus personal reward preferentially engages regions related to mentalizing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Oscar Bartra, Joseph McGuire, and Joseph Kable for providing data and information from their meta-analysis on subjective value. We also thank all the authors who generated coordinate files and/or conducted additional analyses for our vicarious reward meta-analysis. Lastly, we thank Mick Fox and Simon Eickhoff for helpful suggestions regarding ALE analysis. The National Institutes of Mental Health supported this work (grant number F32 MH 098504 to S.A.M.), as well as the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (grant number DGE-1147470 to M.D.S.).

Appendix A

| Paper | Task Description for Relevant Conditions | Type of Reward | Contrast | Source of Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bellebaum, C., Jokisch, D., Gizewski, E., Forsting, M., & Daum, I. (2012). The neural coding of expected and unexpected monetary performance outcomes: Dissociations between active and observational learning. Behavioural Brain Research, 227(1), 241–251. | Participants had to learn by observing the performance and outcomes of another subject. For each trial, they observed another subject choose between two stimuli and receive monetary feedback, such as monetary reward (20 cents) or non-reward (neither reward nor punishment). | Money | Observational feedback learning task: Reward outcome > Non-reward outcome | Personal correspondence |

| Braams, B. R., Güroğlu, B., de Water, E., Meuwese, R., Koolschijn, P. C., Peper, J. S., & Crone, E. A. (2013). Reward- related neural responses are dependent on the beneficiary. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, nst077. | Participants could win money for their best friend in a gambling task. | Money | Friend gain > Fixation | Personal correspondence |

| Burke, C. J., Tobler, P. N., Baddeley, M., & Schultz, W. (2010). Neural mechanisms of observational learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(32), 14431–14436. | Participants could learn by observing the performance and outcomes of another subject. During the gain sessions, they observed another subject choose between two stimuli and receive a reward (10 points) or non-reward (0 points). | Points | Full observational learning during gain session: 10-point gain > 0-point gain | Personal correspondence |

| Chester, D. S., Powell, C. A., Smith, R. H., Joseph, J. E., Kedia, G., Combs, D. J., & DeWall, C. N. (2013). Justice for the average Joe: The role of envy and the mentalizing network in the deservingness of others’ misfortunes. Social Neuroscience, 8(6), 640–649. | Participants observed that non-enviable targets had been accepted into a prestigious student program (i.e., good fortune). | Acceptance into student program | Good fortune for low envy targets > Baseline | Personal correspondence |

| Hamilton, J. P., Chen, M. C., Waugh, C. E., Joormann, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2014). Distinctive and common neural underpinnings of major depression, social anxiety, and their comorbidity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, nsu084. | Participants passively listened to positive affective statements (praise) directed at another person. | Positive social feedback | Healthy controls only: Other positive > Baseline | Personal correspondence |

| Hare, T. A., Camerer, C. F., Knoepfle, D. T., & Rangel, A. (2010). Value computations in ventral medial prefrontal cortex during charitable decision making incorporate input from regions involved in social cognition. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(2), 583–590. doi: 30/2/583 [pii] 0.1523/JNEUROSCI.4089-09.2010 | Participants made donations to different charities. In forced donation trials subjects were instructed how much they had to donate in that trial ($0 – $100 in $5 increments) and had to move a slider to the mandated amount (i.e. forced response). | Money | For all amounts except $0: Forced response > Fixation | Personal correspondence |

| Hooker, C. I., Verosky, S. C., Miyakawa, A., Knight, R. T., & D’Esposito, M. (2008). The influence of personality on neural mechanisms of observational fear and reward learning. Neuropsychologia, 46(11), 2709–2724. | Participants learned object-emotion associations by observing whether a woman reacted with a happy or neutral expression to a neutral object. | Object | Learn happy > Learn neutral | Table 6 |

| Izuma, K., Saito, D. N., & Sadato, N. (2008). Processing of social and monetary rewards in the human striatum. Neuron, 58(2), 284–294. | Participants saw blocks of all positive words showing what others thought of another person (i.e. high social reputation) or saw no feedback about the other person (i.e. no social reputation). | Positive social feedback | Other high social reputation > Other no social reputation | Personal correspondence |

| Jabbi, M., Swart, M., & Keysers, C. (2007). Empathy for positive and negative emotions in the gustatory cortex. Neuroimage, 34(4), 1744–1753. | Participants saw videos of people drinking pleasant and neutral liquids. | Juice | Pleasant > Neutral | Personal correspondence |

| Jung, D., Sul, S., & Kim, H. (2013). Dissociable neural processes underlying risky decisions for self versus other. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7. | Participants were asked to perform a gambling task on behalf of another person (decision-for-other condition). These decisions sometimes resulted in a person winning either 10 points or 90 points. Points were converted to money. | Points/Money | Other Win > Fixation | Personal correspondence |

| Kätsyri, J., Hari, R., Ravaja, N., & Nummenmaa, L. (2013). Just watching the game ain’t enough: striatal fMRI reward responses to successes and failures in a video game during active and vicarious playing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. | Participants watched a pre-recorded gameplay video (vicarious playing) and observed another player’s successes (wins) and failures (losses). | Video game wins | Vicarious play: Win > Loss | Personal correspondence |

| Korn, C. W., Prehn, K., Park, S. Q., Walter, H., & Heekeren, H. R. (2012). Positively biased processing of self-relevant social feedback. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32(47), 16832–16844. | Participants observed others receive desirable feedback about their personality traits. | Positive social feedback | Other desirable feedback > Fixation | Personal correspondence |

| Meffert, H., Gazzola, V., den Boer, J. A., Bartels, A. A., & Keysers, C. (2013). Reduced spontaneous but relatively normal deliberate vicarious representations in psychopathy. Brain, 136(8), 2550–2562. | Participants watched videos of others’ hands receiving loving or neutral touch. | Loving touch | Healthy controls only: Observe loving touch > Observe neutral touch | Personal correspondence |

| Meshi, D., Morawetz, C., & Heekeren, H. R. (2013). Nucleus accumbens response to gains in reputation for the self relative to gains for others predicts social media use. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7. | Participants observed others receive positive feedback about their personality traits or no feedback. | Positive social feedback | Other high positive feedback > Other no feedback | Personal correspondence |

| Molenberghs, P., Bosworth, R., Nott, Z., Louis, W. R., Smith, J. R., Amiot, C. E., Decety, J. (2014). The influence of group membership and individual differences in psychopathy and perspective taking on neural responses when punishing and rewarding others. Human Brain Mapping. | Participants gave monetary rewards or nothing (neutral) to in-group members during a trivia game. | Money | Reward in-group > Neutral in-group | Personal correspondence |

| Morelli, S. A., Rameson, L. T., & Lieberman, M. D. (2014). The neural components of empathy: Predicting daily prosocial behavior. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(1), 39–47. doi: 10.1093/scan/nss088 | Participants were asked to empathize with photos of others’ happy events (e.g., getting engaged) and to view others’ neutral events (e.g., ironing). | Positive emotional events | Happy empathize > Neutral | Table 1 |

| Morrison, I., Björnsdotter, M., & Olausson, H. (2011). Vicarious responses to social touch in posterior insular cortex are tuned to pleasant caressing speeds. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(26), 9554–9562. Morrison | Participants observed brush strokes on another person’s arm at two different speeds: 3 cm/s (pleasant) and 30 cm/s (neutral). | Pleasant touch | Study 1: Seen 3 > Seen 30 | Table 1 |

| Morrison, I., Björnsdotter, M., & Olausson, H. (2011). Vicarious responses to social touch in posterior insular cortex are tuned to pleasant caressing speeds. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(26), 9554–9562. | Participants observed brush strokes on another person’s arm at two different speeds: 3 cm/s (pleasant) and 30 cm/s (neutral). | Pleasant touch | Study 2: Seen 3 > Seen 30 | Table 2 |

| Perry, D., Hendler, T., & Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. (2012). Can we share the joy of others? Empathic neural responses to distress vs joy. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(8), 909–916. | Participants read sentences depicting everyday positive emotional events occurring to a fictional character. | Positive emotional events | Other positive > Fixation | Personal correspondence |

| Spunt, R. P., & Lieberman, M. D. (2012). An integrative model of the neural systems supporting the comprehension of observed emotional behavior. Neuroimage, 59(3), 3050–3059. doi: S1053-8119(11)01166-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.005 | Participants watched video clips of others’ experiencing positive emotions and were asked to imagine why they felt that way. They also did a shape matching task which served as a neutral condition. | Positive emotional events | Positive Why task > Shape matching | Personal correspondence |

| Telzer, E. H., Masten, C. L., Berkman, E. T., Lieberman, M. D., & Fuligni, A. J. (2010). Gaining while giving: An fMRI study of the rewards of family assistance among White and Latino youth. Social Neuroscience, 5(5–6), 508–518.” | Participants choose whether to accept or reject a payment option that affected their own and their family’s endowment. One type of payment included a noncostly-donation to the family (e.g., YOU –$0.00 FAM +$3.00). | Money | Noncostly donation > Fixation | Personal correspondence |

| Telzer, E. H., Fuligni, A. J., Lieberman, M. D., & Galván, A. (2013). Ventral striatum activation to prosocial rewards predicts longitudinal declines in adolescent risk taking. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 3, 45–52. | Paritcipants choose whether to accept or reject a payment option that affected their own and their family’s endowment. One type of payment included a noncostly-donation to the family (e.g., YOU –$0.00 FAM +$3.00). For the control condition, YOU and FAM were presented without a financial gain or loss. | Money | Noncostly donation > Control | Personal correspondence |

| Tricomi, E., Rangel, A., Camerer, C. F., & O’Doherty, J. P. (2010). Neural evidence for inequality-averse social preferences. Nature, 463(7284), 1089–1091. | Inequality was created by recruiting pairs of subjects and giving one of them a large monetary endowment (i.e. high-pay player). This high-pay player then evaluated monetary transfers from the experimenter to the other participant (i.e. low-pay player). | Money | High-pay player: Payments to low-pay player > Control | Personal correspondence |

| Varnum, M. E., Shi, Z., Chen, A., Qiu, J., & Han, S. (2014). When “Your” reward is the same as “My” reward: Self-construal priming shifts neural responses to own vs. friends’ rewards. Neuro Image, 87, 164–169. | Experimenters manipulated participants’ self-construal (independent vs. interdependent). Participants then played a game in which they could win money for a friend during a gambling game. | Money | Interdependent prime for main task: Friend win > Neutral | Personal correspondence |

| Wicker, B., Keysers, C., Plailly, J., Royet, J., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (2003). Both of us disgusted in My Insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron, 40(3), 655–664. | Participants watch videos of other people smelling pleasant odors. | Pleasant odors | Observation of pleasure > Neutral | Personal correspondence |

Appendix B

List of articles included in the meta-analysis of personal reward:

- Acevedo BP, Aron A, Fisher HE, Brown LL. Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2012;7:145–159. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver JD, Lawrence AD, van Ditzhuijzen J, Davis MH, Woods A, Calder AJ. Individual differences in reward drive predict neural responses to images of food. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:5160–5166. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0350-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Hommer DW. Anticipating instrumentally obtained and passively received rewards: A factorial fMRI investigation. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;177:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Knutson B, Fong GW, Caggiano DM, Bennett SM, Hommer DW. Incentive-elicited brain activation in adolescents: Similarities and differences from young adults. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:1793–1802. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4862-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Smith AR, Chen G, Hommer DW. Adolescents, adults and rewards: Comparing motivational neurocircuitry recruitment using fMRI. PloS One. 2010;5:e11440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caria A, Venuti P, de Falco S. Functional and dysfunctional brain circuits underlying emotional processing of music in autism spectrum disorders. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21:2838–2849. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Lawrence AJ, Astley-Jones F, Gray N. Gambling near-misses enhance motivation to gamble and recruit win-related brain circuitry. Neuron. 2009;61:481–490. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MX, Young J, Baek J-M, Kessler C, Ranganath C. Individual differences in extraversion and dopamine genetics predict neural reward responses. Cognitive Brain Research. 2005;25:851–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa VD, Lang PJ, Sabatinelli D, Versace F, Bradley MM. Emotional imagery: Assessing pleasure and arousal in the brain’s reward circuitry. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31:1446–1457. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley TJ, Dalwani MS, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Du YP, Lejuez CW, Raymond KM, Banich MT. Risky decisions and their consequences: Neural processing by boys with Antisocial Substance Disorder. PloS One. 2010;5:e12835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey CG, Allen NB, Harrison BJ, Dwyer D, Yücel M. Being liked activates primary reward and midline self-related brain regions. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31:660–668. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MR, Locke HM, Stenger Va, Fiez JA. Dorsal striatum responses to reward and punishment: Effects of valence and magnitude manipulations. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;3:27–38. doi: 10.3758/cabn.3.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher J-C, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Kohn P, Berman KF. Age-related changes in midbrain dopaminergic regulation of the human reward system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:15106–15111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802127105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Newman JL, Longe OA, Deakin JFW. Instrumental responding for rewards is associated with enhanced neuronal response in subcortical reward systems. Neuro Image. 2004;21:984–990. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Nelson EE, Jazbec S, McClure EB, Monk CS, Leibenluft E, Blair J, Pine DS. Amygdala and nucleus accumbens in responses to receipt and omission of gains in adults and adolescents. Neuro Image. 2005;25:1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figee M, Vink M, de Geus F, Vulink N, Veltman DJ, Westenberg H, Denys D. Dysfunctional reward circuitry in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:867–874. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianaros PJ, Manuck SB, Sheu LK, Kuan DCH, Votruba-Drzal E, Craig AE, Hariri AR. Parental education predicts corticostriatal functionality in adulthood. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21:896–910. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone AP, Prechtl de Hernandez CG, Beaver JD, Muhammed K, Croese C, Bell G, Durighel G, Hughes E, Waldman AD, Frost G, Bell JD. Fasting biases brain reward systems towards high-calorie foods. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;30:1625–1635. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izuma K, Saito DN, Sadato N. Processing of social and monetary rewards in the human striatum. Neuron. 2008;58(2):284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson A, Green E, Murphy C. Age-related functional changes in gustatory and reward processing regions: An fMRI study. Neuro Image. 2010;53:602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.012. monetary reward selectively recruits nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neuroscience. 21:RC159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Bhanji JP, Cooney RE, Atlas LY, Gotlib IH. Neural responses to monetary incentives in major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Bjork JM, Fong GW, Hommer D, Mattay VS, Weinberger DR. Amphetamine modulates human incentive processing. Neuron. 2004;43:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, Varner JL, Hommer D. Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3683–3687. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Fong GW, Bennett SM, Adams CM, Hommer D. A region of mesial prefrontal cortex tracks monetarily rewarding outcomes: Characterization with rapid event-related fMRI. Neuro Image. 2003;18:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leknes S, Lee M, Berna C, Andersson J, Tracey I. Relief as a reward: Hedonic and neural responses to safety from pain. PloS One. 2011;6:e17870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LE, Potts GF, Burton PC, Montague PR. Electrophysiological and hemodynamic responses to reward prediction violation. Neuro Report. 2009;20:1140–1143. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832f0dca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs D, Greicius MD, Abdel-Azim E, Menon V, Reiss AL. Humor modulates the mesolimbic reward centers. Neuron. 2003;40:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00751-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RW, Vercammen A, Lenroot R, Moore L, Langton JM, Short B, Kulkarni J, Curtis J, O’Donnell M, Weickert CS, Weickert TW. Disambiguating ventral striatum fMRI-related bold signal during reward prediction in schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2012;17:280–289. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty JP, Deichmann R, Critchley HD, Dolan RJ. Neural responses during anticipation of a primary taste reward. Neuron. 2002;33:815–826. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic P, Pleger B, Seymour B, Klöppel S, De Martino B, Critchley H, Dolan RJ. Blocking central opiate function modulates hedonic impact and anterior cingulate response to rewards and losses. Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:10509–10516. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2807-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plassmann H, O’Doherty J, Shiv B, Rangel A. Marketing actions can modulate neural representations of experienced pleasantness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:1050–1054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706929105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, Kringelbach ML, de Araujo IET. Different representations of pleasant and unpleasant odours in the human brain. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;18:695–703. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serences JT. Value-based modulations in human visual cortex. Neuron. 2008;60:1169–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JJ, Walther S, Fiebach CJ, Friederich H-C, Stippich C, Weisbrod M, Kaiser S. Neural reward processing is modulated by approach- and avoidance-related personality traits. Neuro Image. 2010;49:1868–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Kiebel SJ, Winston JS, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Brain responses to the acquired moral status of faces. Neuron. 2004;41:653–662. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Gregory MD, Mak YE, Gitelman D, Mesulam MM, Parrish T. Dissociation of neural representation of intensity and affective valuation in human gustation. Neuron. 2003;39:701–711. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00467-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AB, Halari R, Giampetro V, Brammer M, Rubia K. Developmental effects of reward on sustained attention networks. Neuro Image. 2011;56:1693–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Yokum S, Burger KS, Epstein LH, Small DM. Youth at risk for obesity show greater activation of striatal and somatosensory regions to food. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:4360–4366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6604-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka SC, Doya K, Okada G, Ueda K, Okamoto Y, Yamawaki S. Prediction of immediate and future rewards differentially recruits cortico-basal ganglia loops. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:887–893. doi: 10.1038/nn1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil RS, Furl N, Ruff CC, Symmonds M, Flandin G, Dolan RJ, Driver J, Rees G. Rewarding feedback after correct visual discriminations has both general and specific influences on visual cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2010;104:1746–1757. doi: 10.1152/jn.00870.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrase J, Kahnt T, Schlagenhauf F, Beck A, Cohen MX, Knutson B, Heinz A. Different neural systems adjust motor behavior in response to reward and punishment. Neuro Image. 2007;36:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink CF, Pagnoni G, Martin-Skurski ME, Chappelow JC, Berns GS. Human striatal responses to monetary reward depend on saliency. Neuron. 2004;42:509–517. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adolphs R. What does the amygdala contribute to social cognition? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1191:42–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht K, Volz KG, Sutter M, Laibson DI, Von Cramon DY. What is for me is not for you: brain correlates of intertemporal choice for self and other. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2010 doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq046. nsq046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht K, Volz KG, Sutter M, von Cramon DY. What do I want and when do I want it: brain correlates of decisions made for self and other. PloS one. 2013;8(8):e73531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Ring HA, Bullmore ET, Wheelwright S, Ashwin C, Williams S. The amygdala theory of autism. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24(3):355–364. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartra O, McGuire JT, Kable JW. The valuation system: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of BOLD fMRI experiments examining neural correlates of subjective value. Neuroimage. 2013;76:412–427. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, Batson JG, Slingsby JK, Harrell KL, Peekna HM, Todd RM. Empathic joy and the empathy-altruism hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(3):413–426. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair R. Fine cuts of empathy and the amygdala: dissociable deficits in psychopathy and autism. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2008;61(1):157–170. doi: 10.1080/17470210701508855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braams BR, Güroğlu B, de Water E, Meuwese R, Koolschijn PC, Peper JS, Crone EA. Reward-related neural responses are dependent on the beneficiary. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1093/scan/nst077. nst077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Carroll DC. Self-projection and the brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11(2):49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.004. S1364-6613(06)00327-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa N, Motterlini M, Alemanno F, Perani D, Cappa SF. Learning from other people’s experience: A neuroimaging study of decisional interactive-learning. Neuro Image. 2011;55(1):353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canessa N, Motterlini M, Di Dio C, Perani D, Scifo P, Cappa SF, Rizzolatti G. Understanding others’ regret: a FMRI study. PloS one. 2009;4(10):e7402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S, Zilles K, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB. ALE meta-analysis of action observation and imitation in the human brain. Neuroimage. 2010;50(3):1148–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chib VS, Rangel A, Shimojo S, O’Doherty JP. Evidence for a common representation of decision values for dissimilar goods in human ventromedial prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(39):12315–12320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2575-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cikara M, Fiske ST. Bounded empathy: Neural responses to outgroup targets’(mis) fortunes. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23(12):3791–3803. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JC, Dunne S, Furey T, O’Doherty JP. Human dorsal striatum encodes prediction errors during observational learning of instrumental actions. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2012;24(1):106–118. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Empathy: A social psychological approach. Madison, WI: Brown and Benchmark; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes CT, Loewen PJ, Schreiber D, Simmons AN, Flagan T, McElreath R, Paulus MP. Neural basis of egalitarian behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(17):6479–6483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118653109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quervain DJ, Fischbacher U, Treyer V, Schellhammer M, Schnyder U, Buck A, Fehr E. The neural basis of altruistic punishment. Science. 2004;305(5688):1254–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.1100735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen T, Falk A, Fliessbach K, Sunde U, Weber B. Relative versus absolute income, joy of winning, and gender: Brain imaging evidence. Journal of Public Economics. 2011;95(3):279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn E, Aknin L, Norton M. Prosocial spending and happiness: Using money to benefit others pays off (vol 23, pg 41, 2014) Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23(2):155–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dvash J, Gilam G, Ben-Ze’ev A, Hendler T, Shamay-Tsoory SG. The envious brain: the neural basis of social comparison. Human brain mapping. 2010;31(11):1741–1750. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Bzdok D, Laird AR, Kurth F, Fox PT. Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis revisited. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2349–2361. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Bzdok D, Laird AR, Roski C, Caspers S, Zilles K, Fox PT. Co-activation patterns distinguish cortical modules, their connectivity and functional differentiation. Neuroimage. 2011;57(3):938–949. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Grefkes C, Wang LE, Zilles K, Fox PT. Coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: A random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Human brain mapping. 2009;30(9):2907–2926. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Newman JL, Longe OA, William Deakin J. Instrumental responding for rewards is associated with enhanced neuronal response in subcortical reward systems. Neuroimage. 2004;21(3):984–990. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewbank MP, Barnard PJ, Croucher CJ, Ramponi C, Calder AJ. The amygdala response to images with impact. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2009;4(2):127–133. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fareri DS, Delgado MR. Differential reward responses during competition against in-and out-of-network others. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2014;9(4):412–420. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fareri DS, Niznikiewicz MA, Lee VK, Delgado MR. Social Network Modulation of Reward-Related Signals. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(26):9045–9052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0610-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Camerer CF. Social neuroeconomics: the neural circuitry of social preferences. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11(10):419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.09.002. S1364-6613(07)00215-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K, Henderson MD, Eng J, Trope Y, Liberman N. Spatial distance and mental construal of social events. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(4):278–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable SL. Approach and avoidance social motives and goals. Journal of personality. 2006;74(1):175–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gable SL, Reis HT. Good news! Capitalizing on positive events in an interpersonal context. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;42:195–257. [Google Scholar]

- Gläscher J, Hampton AN, O’Doherty JP. Determining a role for ventromedial prefrontal cortex in encoding action-based value signals during reward-related decision making. Cerebral cortex. 2009;19(2):483–495. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA, O’Doherty J, Dolan RJ. Encoding predictive reward value in human amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex. Science. 2003;301(5636):1104–1107. doi: 10.1126/science.1087919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabenhorst F, Rolls ET. Value, pleasure and choice in the ventral prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15(2):56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbaugh WT, Mayr U, Burghart DR. Neural responses to taxation and voluntary giving reveal motives for charitable donations. Science. 2007;316(5831):1622–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1140738. 316/5831/1622 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare TA, Camerer CF, Knoepfle DT, Rangel A. Value computations in ventral medial prefrontal cortex during charitable decision making incorporate input from regions involved in social cognition. J Neurosci. 2010a;30(2):583–590. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4089-09.2010. 30/2/583 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare TA, Camerer CF, Knoepfle DT, Rangel A. Value computations in ventral medial prefrontal cortex during charitable decision making incorporate input from regions involved in social cognition. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010b;30(2):583–590. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4089-09.2010. 30/2/583 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare TA, O’Doherty J, Camerer CF, Schultz W, Rangel A. Dissociating the role of the orbitofrontal cortex and the striatum in the computation of goal values and prediction errors. J Neurosci. 2008;28(22):5623–5630. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1309-08.2008. 28/22/5623 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo A, Suda RK, Murray EA. Bilateral orbital prefrontal cortex lesions in rhesus monkeys disrupt choices guided by both reward value and reward contingency. J Neurosci. 2004;24(34):7540–7548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1921-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izuma K, Saito DN, Sadato N. Processing of social and monetary rewards in the human striatum. Neuron. 2008;58(2):284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.020. S0896-6273(08)00266-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izuma K, Saito DN, Sadato N. The roles of the medial prefrontal cortex and striatum in reputation processing. Social Neuroscience. 2010;5(2):133–147. doi: 10.1080/17470910903202559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbi M, Swart M, Keysers C. Empathy for positive and negative emotions in the gustatory cortex. Neuroimage. 2007;34(4):1744–1753. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski V, Camerer C, Rangel A. Empathic choice involves vmPFC value signals that are modulated by social processing implemented in IPL. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung D, Sul S, Kim H. Dissociable neural processes underlying risky decisions for self versus other. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2013:7. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamichi H, Sasaki AT, Matsunaga M, Yoshihara K, Takahashi HK, Tanabe HC, Sadato N. Medial Prefrontal Cortex Activation Is Commonly Invoked by Reputation of Self and Romantic Partners. PloS one. 2013;8(9):e74958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klucharev V, Hytonen K, Rijpkema M, Smidts A, Fernandez G. Reinforcement learning signal predicts social conformity. Neuron. 2009;61(1):140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.027. S0896-6273(08)01020-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, Varner JL, Hommer D. Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. Neuroreport. 2001;12(17):3683–3687. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Katovich K, Suri G. Inferring affect from fMRI data. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Taylor J, Kaufman M, Peterson R, Glover G. Distributed neural representation of expected value. J Neurosci. 2005;25(19):4806–4812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0642-05.2005. 25/19/4806 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth F, Zilles K, Fox PT, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB. A link between the systems: functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Structure and Function. 2010;214(5–6):519–534. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kätsyri J, Hari R, Ravaja N, Nummenmaa L. Just watching the game ain’t enough: striatal fMRI reward responses to successes and failures in a video game during active and vicarious playing. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2013:7. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird AR, Fox PM, Price CJ, Glahn DC, Uecker AM, Lancaster JL, Fox PT. ALE meta-analysis: Controlling the false discovery rate and performing statistical contrasts. Human brain mapping. 2005;25(1):155–164. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm C, Decety J, Singer T. Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.014. S1053-8119(10)01306-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DJ, Glimcher PW. Comparing apples and oranges: using reward-specific and reward-general subjective value representation in the brain. J Neurosci. 2011;31(41):14693–14707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2218-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]