Abstract

Over 50% of individuals with lower limb amputation fall at least once each year. These individuals also exhibit reduced ability to effectively respond to challenges to frontal plane stability. The range of whole body angular momentum has been correlated with stability and fall risk. This study determined how lateral walking surface perturbations affected the regulation of whole body and individual leg angular momentum in able-bodied controls and individuals with unilateral transtibial amputation. Participants walked at fixed speed in a Computer Assisted Rehabilitation ENvironment with no perturbations and continuous, pseudo-random, mediolateral platform oscillations. Both the ranges and variability of angular momentum for both the whole body and both legs were significantly greater (p < 0.001) during platform oscillations. There were no significant differences between groups in whole body angular momentum range or variability during unperturbed walking. The range of frontal plane angular momentum was significantly greater for those with amputation than for controls for all segments (p < 0.05). For the whole body and intact leg, angular momentum ranges were greater for patients with amputation. However, for the prosthetic leg, angular momentum ranges were less for patients than controls. Patients with amputation were significantly more affected by the perturbations. Though patients with amputation were able to maintain similar patterns of whole body angular momentum during unperturbed walking, they were more highly destabilized by the walking surface perturbations. Individuals with transtibial amputation appear to predominantly use altered motion of the intact limb to maintain mediolateral stability.

Keywords: Stability, Transtibial Amputation, Gait, Variability, Virtual Reality

Introduction

Individuals with lower limb amputation are at greater risk of falling than able-bodied individuals with over 50% falling each year [1]. This higher incidence of falling is potentially related to differences between the intact and prosthetic leg, specifically different inertial properties, lack of active ankle control, and disrupted sensory input. The majority of all falls occur during locomotion [2] and humans are particularly unstable in the mediolateral direction while walking [3, 4]. Individuals with lower limb amputation are mediolaterally more unstable during walking than able-bodied individuals. These differences in stability become more pronounced during walking in destabilizing environments such as a rocky surface [5] or with mediolateral surface oscillations [6–8].

Whole body angular momentum, the sum of the angular momentum about the center of mass for each body segment, exhibits a high degree of contralateral segment cancelling [9]. Angular momentum has been related to fall risk as a large angular momentum during a stumble will likely lead to a fall [10]. Individuals with unilateral transtibial amputation had a greater mean range of angular momentum across a range of speeds compared to able-bodied controls [10]. Angular momentum mean differences were also found during the higher fall risk task of downhill walking [11]. Changes in mean angular momentum have been correlated with fall risk metrics in hemiparetic stroke patients [12]. The correlation is especially strong during single support on the paretic leg, reflecting deficits on the involved side [12].

While continuous, mediolateral perturbations induce local dynamic instability [7, 13], the response of the individuals’ limbs as they contribute to whole body angular momentum has not been investigated. Studies have used the range of angular momentum to identify deficits in walking stability [10–12]. Angular momentum quantifies the rotation of segments [9]. In the frontal plane, if an individual has a large range of angular momentum, they will likely have a large magnitude of angular momentum during a stumble which would require an extensive response including large joint torques to recover and avoid a fall to the side [14, 15]. However, a fall happens during a single “bad” stride and therefore may not be identified by average measures. Thus, within-subject stride-to-stride variability of angular momentum may provide a better measure of fall risk because it indicates how likely an individual is to experience a magnitude of angular momentum on a given stride (independent of the mean angular momentum) that is sufficiently large to prevent them from being able to recover from a perturbation. This is especially pertinent since an individual could have a small average angular momentum range, but a large stride-to-stride variability in that range such that they could still experience individual strides with excessively large angular momentum.

This study determined the effects of destabilizing mediolateral walking surface perturbations on the regulation of whole body and individual leg frontal plane angular momentum during walking. Of particular interest was how these responses differed between able-bodied controls and individuals with unilateral transtibial amputation. We adopted a paradigm of continuous platform perturbations known to induce significant mediolateral instability [6–8, 13]. Since angular momentum has been related to stability [10–12], we hypothesized that the mean range and variability of frontal plane angular momentum would be greater during platform perturbations than no perturbations. Likewise, patients with amputation were more sensitive to these perturbations leading to stronger responses [10–12]. Thus, we also hypothesized that the range and variability of whole body angular momentum would be greater in patients with transtibial amputation than in able-bodied controls. Lastly, because Beurskens et al. [8] found that the prosthetic leg of individuals with transtibial amputation exhibited greater local dynamic instability than the intact leg, we hypothesized that whole body angular momentum range and variability would be greater for the prosthetic leg than the intact leg.

Methods

In accordance with the Institutional Review Boards of Brooke Army Medical Center and The University of Texas, nine individuals with traumatic, unilateral, transtibial amputation (TTA; 9/0 M/F, 30.7 ± 6.8 yo, 1.76 ± 0.11 m, 90.2 ± 16.1 kg) and thirteen able-bodied controls (AB; 10/3 M/F, 24.8 ± 6.9 yo, 1.75 ± 0.08 m, 79.3 ± 11.6 kg) completed the protocol after providing written informed consent. This participant pool has been used for previous analyses and additional information is available in those publications [6–8] and a supplementary table. TTA underwent amputation following traumatic injury (8) or osteosarcoma (1), were receiving treatment at a specialized outpatient rehabilitation facility for injured U.S. service members, and were free from orthopedic and neurological disorders of their intact limb that might have affected walking. All patients with TTA had sockets that were properly fitted by trained and licensed prosthetists and used an energy storage and return foot, thus we expect little difference between patients due to prosthetic components [16].

The protocol was described in detail previously [6–8]. In summary, participants walked on a 1.8 m wide treadmill within a Computer Assisted Rehabilitation Environment (CAREN; Motek Medical, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Walking speed was fixed for each participant as a function of their leg length (l) [17], such that . This resulted in an average walking speed of 1.22 ± 0.28 m/s across participants. Participants completed a 6 min warmup prior to completing five 3-minute trials of unperturbed walking (NOP) and five 3-minute trials of walking with continuous, pseudorandom, mediolateral platform oscillations (PLAT). Perturbations were generated using the sum of four incommensurate sine waves [6, 7]. Order of presentation of trials was randomized and balanced across participants.

Whole body kinematic data were collected at 60 Hz from 57 markers and digitized joint centers [18] using a 24-camera Vicon motion capture system (Vicon Motion Systems, Oxford, UK). Data were post-processed using Visual 3D (C-Motion Inc., Germantown, MD) to create a 13-segment model [19] used to determine segment inertial properties and linear and angular velocities. For the amputated limb, the model’s shank was adjusted by reducing the mass by 35% and shifting the center of mass position 35% more proximal [20]. Gait events were determined using the velocity-based algorithm developed by Zeni and colleagues [21].

Frontal plane angular momentum (H) was then calculated for each segment about the whole body center of mass [9] as:

| (1) |

where r⃗, v⃗, and ω⃗ are the position, velocity, and angular velocity of the segment COM, respectively. m is the segment mass and I is the segment moment of inertia. r⃗body and v⃗body are the whole body COM position and velocity. We focused on the frontal plane because walking is most unstable in the mediolateral direction [4, 13, 22, 23]. Also, persons with amputation exhibit significantly different frontal plane angular momentum than able-bodied controls [10, 11]. We summed the frontal plane angular momenta of all 13 segments to compute whole body frontal plane angular momentum [9, 10]. We also summed the frontal plane angular momenta of the foot, shank, and thigh of each leg to get the individual leg frontal plane angular momenta. Whole body frontal plane angular momentum values were normalized to Height × Body Mass × Walking Speed [10]. Because the leg inertial properties differed between prosthetic and intact, the leg angular momenta were normalized to Leg Length × Leg Mass × Walking Speed.

For each participant, the range of the frontal plane angular momentum was calculated across all strides of both NOP and PLAT. In addition, we computed the mean of the within-subject standard deviation across all strides for each condition over the single support phase of the prosthetic and intact legs for TTA and of the left and right legs for AB, respectively. These range and variability values were extracted from the whole body angular momentum curves as well as from both legs.

We ran separate repeated measures design 2-factor (Group × Condition) ANOVAs. We also compared the response of the prosthetic vs. intact leg of the TTA by running a 2-factor (Leg × Condition) ANOVA for the range and both variability time points of the legs. When appropriate, pairwise comparisons were made using estimated marginal means. We completed all statistical analyses using SPSS 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

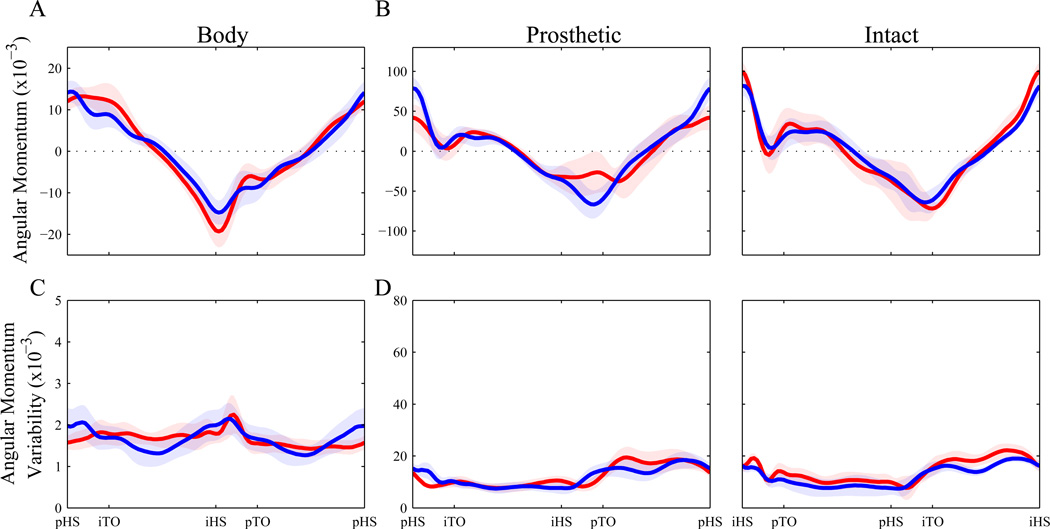

Qualitatively, there were few appreciable differences between TTA and AB during NOP (Fig. 1). The most notable difference was a reduced prosthetic leg angular momentum during the second double support phase (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Frontal plane angular momentum during NOP.

The between-subjects mean ± SD (A – B) and group mean of within-subject variability ± SD (C – D). The whole body angular momentum (A, C) is normalized to Height × Body Mass × Walking Speed. The prosthetic/left leg and intact/right leg (B, D) angular momentum is normalized to Leg Length × Leg Mass × Walking Speed. AB are plotted in blue and TTA are plotted in red. The whole body and prosthetic leg are graphed from prosthetic/left heel strike to prosthetic/left heel strike with the intermediate gait events labeled on the x-axis. The intact leg is graphed from intact/right leg heel strike to intact/right leg heel strike.

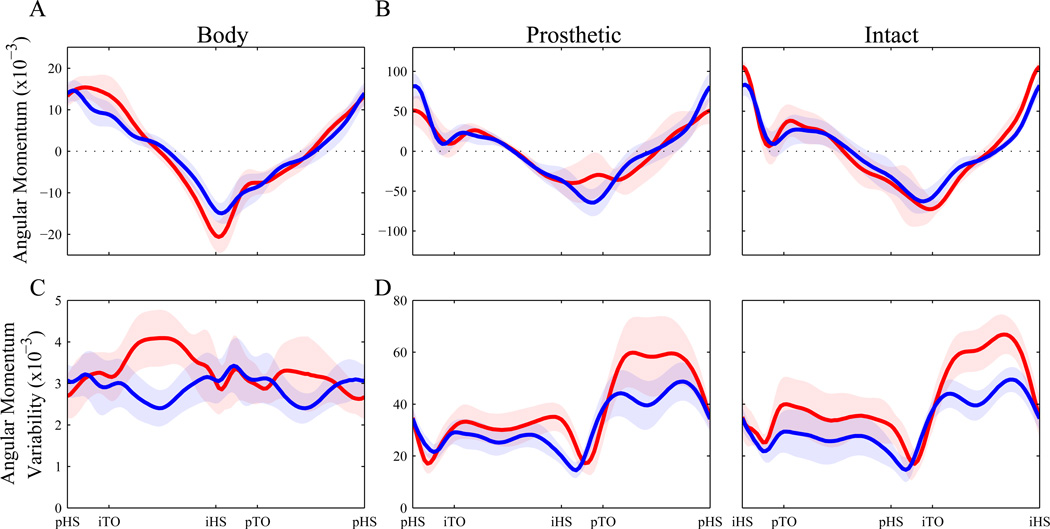

There were no clear differences in mean frontal plane angular momentum patterns between NOP and PLAT (Fig. 2A–B vs. Fig. 1A–B). However, the platform perturbation condition induced notably greater stride-to-stride variability for both groups (Fig. 2C–D vs. Fig. 1C–D). During the PLAT trials, subjects in both groups exhibited few qualitative differences between their mean curves (Fig. 2A–B). The reduced double support prosthetic leg angular momentum observed in TTA during NOP (Fig. 1B) was likewise still observed during PLAT (Fig. 2B). These TTA did, however, exhibit visibly greater variability than AB during PLAT perturbation trials, especially during both single support phases (Fig. 2C–D).

Figure 2. Frontal plane angular momentum during PLAT.

The between-subjects mean ± SD (A – B) and group mean of within-subject variability ± SD (C – D). The whole body angular momentum (A, C) is normalized to Height × Body Mass × Walking Speed. The prosthetic/left leg and intact/right leg (B, D) angular momentum is normalized to Leg Length × Leg Mass × Walking Speed. AB are plotted in blue and TTA are plotted in red. The whole body and prosthetic leg are graphed from prosthetic/left heel strike to prosthetic/left heel strike with the intermediate gait events labeled on the x-axis. The intact leg is graphed from intact/right leg heel strike to intact/right leg heel strike. The scale on the plots are the same as the NOP Figure 1.

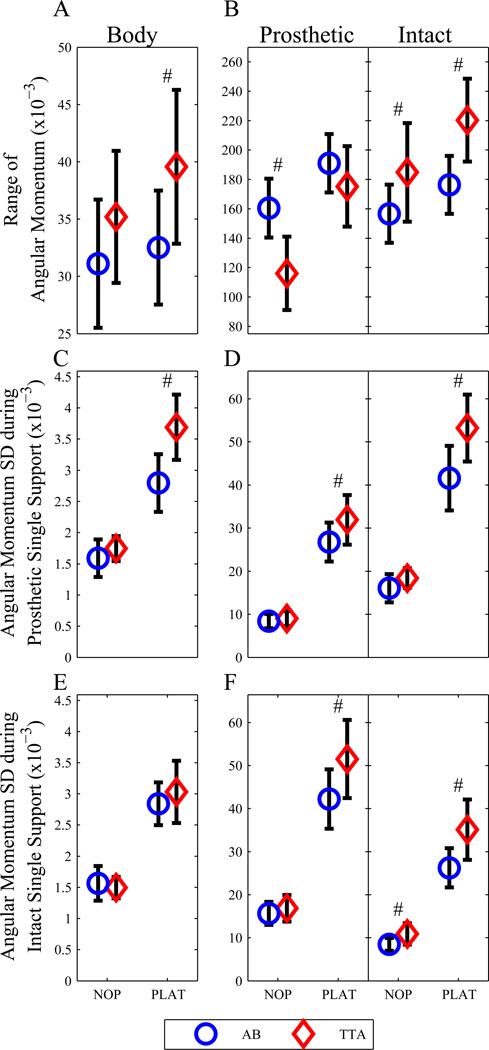

These qualitative observations were substantiated by our statistical analyses. There was a significant main effect difference between Groups for the range of angular momentum for all three comparisons (Fig. 3A–B, Table 1A). There was also a significant main effect difference between Conditions for range of angular momentum, increasing from NOP to PLAT. Furthermore, a significant Group × Condition interaction existed with TTA exhibiting a greater response with the whole body and intact leg, but a reduced response in the prosthetic leg (Fig. 3A–B, Table 1A).

Figure 3. Group mean frontal plane angular momentum variables.

The mean range of the frontal plane angular momentum (A – B) and the mean variability over prosthetic/left single support (C – D) and intact/left single support (E – F) for both NOP and PLAT. AB are displayed as blue circles and TTA are displayed as red diamonds. All plots are represent the group means with 1 SD error bars.

Table 1.

Outcomes of ANOVA for Condition × Group analysis

| A - Range | Whole Body | Prosthetic/Left | Intact/Right | |||

| F | p-value | F | p-value | F | p-value | |

| Condition | 33.64 | (0.00) | 343.02 | (0.00) | 107.42 | (0.00) |

| Group | 5.28 | (0.03) | 9.99 | (0.00) | 11.92 | (0.00) |

| Condition × Group | 8.90 | (0.01) | 34.83 | (0.00) | 8.89 | (0.01) |

| B - SD Prosthetic Single Support | Whole Body | Prosthetic/Left | Intact/Right | |||

| F | p-value | F | p-value | F | p-value | |

| Condition | 430.62 | (0.00) | 585.43 | (0.00) | 560.23 | (0.00) |

| Group | 11.83 | (0.00) | 4.29 | (0.05) | 10.56 | (0.00) |

| Condition × Group | 23.70 | (0.00) | 7.13 | (0.01) | 13.21 | (0.00) |

| C - SD Intact Single Support | Whole Body | Prosthetic/Left | Intact/Right | |||

| F | p-value | F | p-value | F | p-value | |

| Condition | 435.91 | (0.00) | 556.97 | (0.00) | 449.33 | (0.00) |

| Group | 0.21 | (0.65) | 5.65 | (0.03) | 13.32 | (0.00) |

| Condition × Group | 3.75 | (0.07) | 9.72 | (0.01) | 10.71 | (0.00) |

Both the whole body and the intact leg variability during prosthetic single support exhibited significant main effects for Group, with TTA being more variable than AB (Fig. 3C–D, Table 1B). Variability of all segments during prosthetic single support also increased from NOP to PLAT and TTA exhibited greater responses to perturbation based on a significant Group × Condition interaction effect (Fig. 3C–D, Table 1B).

There was no significant Group effect for variability of whole body angular momentum. However, both legs exhibited significantly greater variability for the TTA group during intact single support (Fig. 3E–F, Table 1C). The whole body and both legs exhibited significantly greater variability during the PLAT condition, with prosthetic and intact leg variability increasing more for the TTA group (Fig. 3E–F, Table 1C).

No significant differences were found between TTA and AB in either range or variability of H during NOP (Fig. 3A, C, E). However, during NOP, the TTA prosthetic leg exhibited a smaller range, while the intact leg exhibited both a greater range (Fig. 3B) and greater variability during intact single support (Fig. 3F). The ranges and variability of all segments and both groups were both greater during the PLAT condition (Fig. 3). The ranges of both the whole body (Fig. 3A) and intact leg (Fig. 3B) were greater for TTA than AB. There was no significant difference in range between groups for the prosthetic (left) leg (Fig. 3B). The TTA also exhibited significantly greater variability for whole body in prosthetic single support (Fig. 3C) and for both legs in prosthetic single support (Fig. 3D) and intact single support (Fig. 3F).

Within the TTA group, the intact leg exhibited a significantly greater range during both NOP (Fig. 1B) and PLAT (Fig. 2B, Table 2). However, the variability during ipsilateral single support was greater on the prosthetic leg than the intact leg (Fig. 2D). Both legs responded to PLAT in a similar manner, as there were no significant Leg × Condition interaction effects (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes of ANOVA for Condition × Leg analysis

| Range | SD ipsilateral Single Support |

SD contralateral Single Support |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p-value | F | p-value | F | p-value | |

| Condition | 18.22 | (0.00) | 133.50 | (0.00) | 156.17 | (0.00) |

| Leg | 53.84 | (0.00) | 7.03 | (0.02) | 2.49 | (0.13) |

| Condition × Leg | 2.32 | (0.15) | 0.46 | (0.51) | 0.01 | (0.94) |

Discussion

This study quantified whole body and individual leg frontal plane angular momenta during destabilizing mediolateral walking surface perturbations to determine how these responses differed between able-bodied controls and individuals with unilateral transtibial amputation. As expected, the platform perturbations destabilized participants in both groups and lead to greater range and variability of H. However, TTA exhibited a greater response to these perturbations than AB. The legs of TTA also responded in opposite directions, with greater intact leg range of H and smaller prosthetic leg range of H during PLAT.

We hypothesized that mediolateral platform perturbations would lead to greater range and variability in whole body and individual leg frontal plane angular momentum. As hypothesized, there was a significant main effect for condition with greater range and variability during the PLAT condition. In addition, nearly all variables exhibited significant Condition × Group interactions, indicating that TTA had a greater response to the perturbations than AB. This supports our second hypothesis that the changes in H would be greater for TTA than AB. However, contrary to our third hypothesis that the range and variability of the frontal plane angular momentum would be greater for the prosthetic leg than the intact, it was in fact opposite with greater H on the intact leg than the prosthetic leg.

As described by Herr and Popovic [9], the range of whole body angular momentum is kept low through extensive cancelation between segments which others have attributed to a high degree of regulation. We observed similar cancelation with small ranges for whole body angular momentum and nearly equal and opposite patterns for the individual legs. However, likely due to inertial and/or control differences between the intact and prosthetic leg, there was a deviation in the prosthetic leg angular momentum pattern which lead to a greater whole body angular momentum.

Several studies have used the range of the angular momentum to infer differing levels of fall risk [10, 11]. However, the present results demonstrated that variability of angular momentum may be a more sensitive measure, better indicating the likelihood that an individual will experience an “unstable” stride at some point during a given bout of walking. In hemiparetic stroke patients, the single support phase was found to be particularly unstable during walking [12]. We found particularly notable increases in angular momentum variability during both single support phases. Interestingly, Silverman [11] found that the range of angular momentum during the greater fall risk task of downhill walking was less than during level walking in young, healthy participants. They interpreted this to reflect tighter control in response to the increased fall risk, similar to cautious gait patterns. That would suggest that the decrease in angular momentum was more related to fear of falling than actual fall risk. Our findings support the interpretation that greater angular momentum is related to greater fall risk.

Our research group previously investigated changes in various other measures of dynamic stability on this same data set, specifically dynamic margins of stability [6] and local and orbital dynamic stability [7, 8]. All of the study variables, including our analysis of angular momentum, indicate that mediolateral perturbations lead to greater instability, especially in the TTA group. In addition, like our present findings, our previous studies found greater differences in the step-to-step variability of the various different parameters examined than in mean measures. This emphasizes the importance of quantifying variability and other step-to-step measures of stability rather than relying on aggregate measures (i.e., averages) that may miss particularly unstable deviations from the typical walking pattern.

There exists a large body of literature on various dynamic stability measures [7, 8, 24–26]. There is also a growing, and predominantly separate, body of literature on angular momentum changes in different populations and scenarios [9–12, 15, 27–29]. While Nott et al. [12] correlated angular momentum changes with fall risk in stroke patients, this was only through post hoc grouping of participants based on balance assessment indexes, not fall incidence or mechanical stability measures. To our knowledge, the present findings represent the first step toward bridging the gap between established, mechanically derived measures of stability and angular momentum changes. By comparing our angular momentum research to the dynamic stability measures from the same data set of Beltran [6] and Beurskens [7, 8], we have shown that these two lines of inquiry at least yield consistent results. This further supports the use of angular momentum in relation to dynamic stability.

While the smaller range and variability of the prosthetic leg compared to the intact leg of the TTA was unexpected, this was likely due to differing mechanics and abilities. Because the prosthetic leg does not have any active ankle control, its motion is likely largely defined by the mechanics of the prosthesis and gravity. In contrast, the intact leg is capable of making many fine adjustments to the force generation and movement, and thus is responsible for making the majority of the compensations to regulate the angular momentum. Beurskens et al. [8] came to a similar conclusion, since TTA exhibited greater local instability on their prosthetic leg, yet still maintained comparable upper body stability to AB, presumably through compensatory movements in the intact segments. However, Silverman [11] found a similar decrease in angular momentum range during the higher fall risk task of downhill walking. They suggested that individuals were more tightly controlling their angular momentum to reduce the fall risk. It is possible that TTA are more fearful of falling while walking on their prosthetic leg, and so they make similar changes to their gait which regulate their angular momentum.

Based on our findings of angular momentum and corroborating evidence from additional stability measures [6–8], it is clear mediolateral perturbations significantly impact walking stability. These differences appear to be amplified in these patients with unilateral TTA. Thus, it is important to both evaluate and train patients with lower limb amputation during perturbed walking in addition to standard level walking surfaces. It is only during perturbed walking conditions that stability is truly challenged and patients are at a high risk of falling. As the majority of compensatory movements are made by the intact limb, it is possible that by improving the adaptability and control of the prosthetic leg through training and/or prosthesis design, individuals with amputation may be able to better regulate their angular momentum and reduce their fall risk.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

We measured the frontal plane angular momentum of unilateral transtibial amputees.

Participants walked unperturbed and with continuous mediolateral oscillations.

Amputees had a greater response to the perturbation than controls.

The intact leg had a greater range and variability than the prosthetic leg.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant 1-R01-HD059844 (to JBD and JMW). The authors would like to thank Emily Sinitski and Dr. Kevin Terry for their help with data collection and data processing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, Department of Defense and/or the U.S. Government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with this work.

References

- 1.Miller WC, Speechley M, Deathe B. The prevalence and risk factors of falling and fear of falling among lower extremity amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1031–1037. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.24295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinetti ME, Doucette J, Claus E, Marottoli R. The contribution of predisposing and situational risk factors to serious fall injuries. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1995;43:1207–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauby CE, Kuo AD. Active control of lateral balance in human walking. J Biomech. 2000;33:1433–1440. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo AD. Stabilization of Lateral Motion in Passive Dynamic Walking. The International Journal of Robotics Research. 1999;18:917–930. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gates DH, Scott SJ, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB. Frontal plane dynamic margins of stability in individuals with and without transtibial amputation walking on a loose rock surface. Gait Posture. 2013;38:570–575. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beltran EJ, Dingwell JB, Wilken JM. Margins of stability in young adults with traumatic transtibial amputation walking in destabilizing environments. J Biomech. 2014;47:1138–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beurskens R, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB. Dynamic Stability of Individuals with Transtibial Amputation Walking in Destabilizing Environments. J Biomech. 2014;47:1675–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beurskens R, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB. Dynamic Stability of Superior vs. Inferior Body Segments in Individuals with Transtibial Amputation Walking in Destabilizing Environments. J Biomech. 2014;47:3072–3079. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herr H, Popovic M. Angular momentum in human walking. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2008;211:467–481. doi: 10.1242/jeb.008573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverman AK, Neptune R. Differences in whole-body angular momentum between below-knee amputees and non-amputees across walking speeds. J Biomech. 2011;44:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverman AK, Wilken JM, Sinitski EH, Neptune RR. Whole-body angular momentum in incline and decline walking. J Biomech. 2012;45:965–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nott C, Neptune R, Kautz S. Relationships between frontal-plane angular momentum and clinical balance measures during post-stroke hemiparetic walking. Gait Posture. 2014;39:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAndrew PM, Wilken JM, Dingwell JB. Dynamic Stability of Human Walking in Visually and Mechanically Destabilizing Environments. J Biomech. 2011;44:644–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pijnappels M, Bobbert MF, van Dieen JH. How early reactions in the support limb contribute to balance recovery after tripping. J Biomech. 2005;38:627–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pijnappels M, Bobbert MF, van Dieën JH. Contribution of the support limb in control of angular momentum after tripping. J Biomech. 2004;37:1811–1818. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofstad C, Linde H, Limbeek J, Postema K. Prescription of prosthetic ankle-foot mechanisms after lower limb amputation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD003978. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003978.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaughan CL, O'Malley MJ. Froude and the contribution of naval architecture to our understanding of bipedal locomotion. Gait Posture. 2005;21:350–362. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilken JM, Rodriguez KM, Brawner M, Darter BJ. Reliability and Minimal Detectible Change values for gait kinematics and kinetics in healthy adults. Gait Posture. 2012;35:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.09.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gates DH, Wilken JM, Scott SJ, Sinitski EH, Dingwell JB. Kinematic strategies for walking across a destabilizing rock surface. Gait Posture. 2012;35:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith JD, Martin PE. Short and longer term changes in amputee walking patterns due to increased prosthesis inertia. JPO: Journal of Prosthetics and Orthotics. 2011;23:114–123. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeni JA, Jr, Richards JG, Higginson JS. Two simple methods for determining gait events during treadmill and overground walking using kinematic data. Gait Posture. 2008;27:710–714. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dean JC, Alexander NB, Kuo AD. The effect of lateral stabilization on walking in young and old adults. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2007;54:1919–1926. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.901031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAndrew PM, Dingwell JB, Wilken JM. Walking variability during continuous pseudo-random oscillations of the support surface and visual field. J Biomech. 2010;43:1470–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dingwell JB, Cusumano JP. Nonlinear time series analysis of normal and pathological human walking. Chaos. 2000;10:848–863. doi: 10.1063/1.1324008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dingwell JB, Cusumano JP, Cavanagh PR, Sternad D. Local dynamic stability versus kinematic variability of continuous overground and treadmill walking. J Biomech Eng. 2001;123:27–32. doi: 10.1115/1.1336798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dingwell JB, Kang HG, Dingwell JB, Kang HG. Differences between local and orbital dynamic stability during human walking. J Biomech Eng. 2007;129:586–593. doi: 10.1115/1.2746383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neptune R, McGowan C. Muscle contributions to whole-body sagittal plane angular momentum during walking. J Biomech. 2011;44:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Popovic M, Hofmann A, Herr H. Angular momentum regulation during human walking: biomechanics and control; Robotics and Automation, 2004 Proceedings ICRA'04 2004 IEEE International Conference on: IEEE; 2004. pp. 2405–2411. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reisman DS, Scholz JP, Schoner G. Coordination underlying the control of whole body momentum during sit-to-stand. Gait Posture. 2002;15:45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(01)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.