Abstract

Objective

To identify novel genetic markers of obesity-related traits and to identify gene-diet interactions with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (n-3 PUFA) intake in Yup’ik people.

Material and Methods

We measured body composition, plasma adipokines and ghrelin in 982 participants enrolled in the Center for Alaska Native Health Research (CANHR) Study. We conducted a genome-wide SNP linkage scan and targeted association analysis, fitting additional models to investigate putative gene-diet interactions. Finally, we performed bioinformatic analysis to uncover likely candidate genes within the identified linkage peaks.

Results

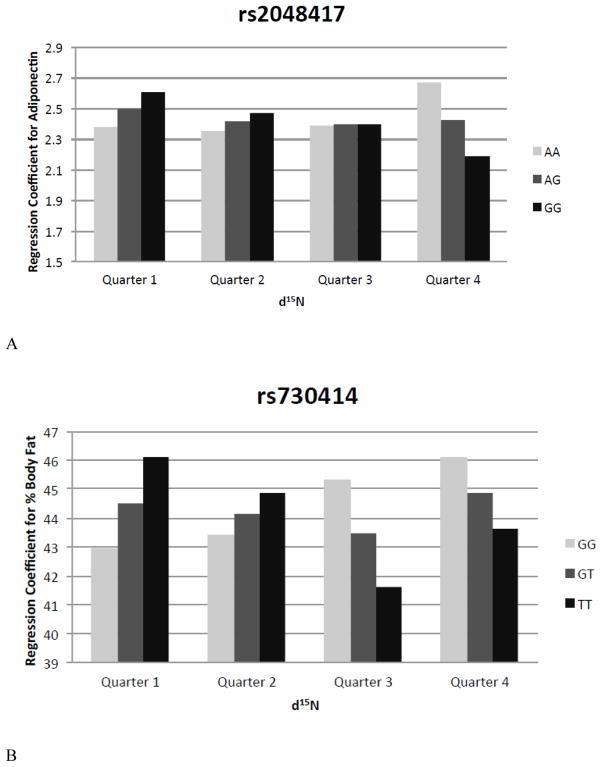

We observed evidence of linkage for all obesity-related traits, replicating previous results and identifying novel regions of interest for adiponectin (10q26.13-2) and thigh circumference (8q21.11-13). Bioinformatic analysis revealed DOCK1, PTPRE (10q26.13-2) and FABP4 (8q21.11-13) as putative candidate genes in the newly identified regions. Targeted SNP analysis under the linkage peaks identified associations between three SNPs and obesity-related traits: rs1007750 on chromosome 8 and thigh circumference (P=0.0005), rs878953 on chromosome 5 and thigh skinfold (P=0.0004), and rs1596854 on chromosome 11 for waist circumference (P=0.0003). Finally, we showed that n-3 PUFA modified the association between obesity related traits and two additional variants (rs2048417 on chromosome 3 for adiponectin, P for interaction=0.0006 and rs730414 on chromosome 11 for percentage body fat, P for interaction=0.0004).

Conclusions

This study presents evidence of novel genomic regions and gene-diet interactions that may contribute to the pathophysiology of obesity-related traits among Yup’ik people.

Keywords: Alaska Native, linkage, obesity, n-3 fatty acids

1. INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a complex disorder arising from multiple interactions of genes, behavior and environment. Family-based heritability estimates provide strong evidence of genetic contributions to obesity-related phenotypes [1–3]. Although more than 40 genome-wide linkage scans and association studies, as well as several hundred candidate gene studies, have yielded numerous obesity-related loci, a large proportion of the genetic risk for obesity remains unexplained [3–5]. While a few genomic regions, e.g., 1p36, 2p21, 3q27, 10p12, and 11q23-24 or genes such as FTO and MC4R have been widely replicated across various studies, other findings remain largely inconsistent [3, 4, 6]. Moreover, body mass index (BMI) is an imperfect proxy for body fat with differential validity among populations, which highlights the importance of studying additional phenotypes such as skinfold thickness or circumference measures [2].

Meta-analyses of genome wide association studies (GWAS) and linkage scans suggest that obesity-related phenotypes may be influenced by many genes with small effects [7]. Such genes can be fruitfully studied in geographically remote populations, such as the Yup’ik people, due to their extended family structure and reduced genetic variation [8]. Yup’ik people living in Southwest Alaska have a high prevalence of the ‘healthy obese’ phenotype, where obesity is not closely tied with other metabolic complications as is commonly seen in other populations [9]. Specifically, Yup’ik people have a historically low prevalence of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes despite obesity prevalence similar to those of the US and Canadian general populations [10–15]. Such unique separation of obesity with other metabolic complications may be related to the traditional Yup’ik diet, which is high in marine-derived omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA) [9, 16]. Although prior studies from our group have found associations between candidate SNPs in FTO, ETV5, HHEX, CDKAL1 and metabolic traits [17, 18], the genetic contributions to obesity in the Yup’ik have not been comprehensively examined at the genome-wide level.

In this study, we examined the genetic architecture of obesity-related phenotypes, including BMI, multiple measures of body composition, and plasma adipokine concentrations, in Yup’ik people. We conducted a whole genome linkage scan and targeted association testing within observed linkage peaks, supplemented by a bioinformatic analysis. In addition, we investigated whether a diet rich in marine n-3 PUFA intake modifies the associations between genetic variants and obesity traits.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Participants

The Center for Alaska Native Health Research (CANHR) studies genetic, behavioral, and dietary risk factors underlying obesity and their relationship to diabetes and cardiovascular disease among Yup’ik people [15]. Recruitment of participants from 11 Southwest Alaska communities began in 2003 and is currently ongoing. This study sample consists of 982 non-pregnant Yup’ik individuals that were ≥14 years old at the time of enrollment and reflects the age distribution of all eligible participants according to the 2000 U.S. census.

2.2 Ethics

Participants provided written informed consent. The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Alaska and the National and Alaska Area Indian Health Service, as well as the Yukon-Kuskokwim Human Studies Committee, approved the study protocols.

2.3 Measurements of anthropometric, clinical, and dietary characteristics

Anthropometric measurements, including height, weight, four circumferences (waist, hip, triceps, and thigh), and four skinfolds (abdominal, subscapular, triceps and thigh) were collected using protocols from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III Anthropometric Procedures Manual [19] as previously described [14] and percentage body fat was measured by electrical bioimpedance using a Tanita TBF-300A body composition analyzer (Tanita Corp., Arlington Heights, IL). Blood samples were collected from participants after an overnight fast, and lipoproteins including total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL-) cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL-) cholesterol, very low density lipoprotein (VLDL-) cholesterol, apolipoprotein A1, and plasma triglycerides were assayed as previously described [14]. Adiponectin and leptin were measured by radioimmunoassay (Linco Research, St Charles, MO for adiponectin and leptin; and Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Burlingame, CA for ghrelin). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were respectively 7.1% and 12.1% for adiponectin, 6.7% and 11.1% for leptin, and 3.4% and 25.4% for ghrelin [20]. Long-term intake of n-3 PUFA was estimated using the nitrogen stable isotope ratio (δ15N) of red blood cells (RBC), as previously described [21–23].

2.4 Genotyping and statistical analysis

The Linkage-IV panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to genotype 6090 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at the Center for Inherited Disease Research [22]. Family structure, quality control procedures, and methods used for both linkage and association analysis are described in detail previously [22]. Briefly, for non-normally distributed traits, we implemented either logarithmic transformation for body fat proportion, waist and thigh circumferences, abdominal, subscapular, and triceps skinfolds, leptin, and ghrelin; square root transformation for adiponectin; and Box-Cox transformation for hip and triceps circumferences to normalize the distributions of residuals [24]. All linkage and association models included age, sex, community group (inland vs. coastal), and n-3 PUFA intake. In the association analyses, we fit additional models including an interaction term between the SNP genotype (additive effect) and quartiles of the δ15N, and used likelihood ratio test to compare the models. We estimated statistical power to detect SNP-δ15N interactions to exceed 60% for the examined traits. To correct for multiple testing, we determined the effective number of SNPs using spectral decomposition of the correlation matrix for the SNP genotypes [25, 26]. We annotated SNPs using the SNAP 2.2 (SNP Annotation and Proxy Search) program, the 1000 Genomes Pilot project data, and GeneCruiser 3.2.2 [27, 28]. To identify SNPs occurring in potential regulatory regions, we used RegulomeDB [29].

2.5 Bioinformatic analysis

We searched for the keyword “obesity” to compile a list of training genes using the Gene Evidence search in HUGE Navigator [30], selecting only genes with a HUGE score of 0.10 that were only related to obesity and not type 2 diabetes. We converted gene names to Ensembl or EntrezGene IDs using BioMart Central Portal ID converter [31]. Information on genes of interest was obtained using GeneCards [32].

Using our study data, we extracted lists of genes that physically fell within linkage peaks that exceeded a logarithm of the odds (LOD) score of 2. To identify obesity candidate genes from these regions, we employed three complementary software packages, which use different prioritization methodologies: Gene Wanderer [33], TOPPGene Suite [34], and ENDEAVOUR [35]. Gene Wanderer prioritizes genes by using random walk analysis to estimate similarities in protein-protein interaction networks [33]. TOPPGene uses semantic annotations to estimate fuzzy-based similarity measures between any two genes that are subsequently combined into an overall score; a P-value of each annotation of a test gene is then derived by random sampling of the whole genome [34]. We chose the default gene model for TOPPGene analysis. ENDEAVOUR uses a set of training genes and multiple genomic data sources to first propose several models, then applies each model to the candidate genes to rank them against the profile of the training genes and estimate P-values, and finally merges the rankings from each model into one global ranking [35]. Our ENDEAVOUR model included BIND, MINT, BioGRID, STRING, BPRD and Intact interactions, KEGG and GO annotations, as well as Cis-regulatory models, motif and text mining. We based all coordinates on the human genome 18 build (Hg18), converting from build19 (Hg19) using UCSC Browser LiftOver tool when appropriate. We considered results from the analysis significant if the P-value (TOPPGene and ENDEAVOUR) was less than or equal to 0.005, or if the Gene Wanderer prioritization score, which reflects the global similarity of candidate genes to members of a known disease gene family [33], was at least 0.1. We defined candidate genes as genes that were identified by at least two out of the three algorithms, or by one algorithm plus interactions identified by Ingenuity IPA (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA).

3. RESULTS

3.1 Baseline characteristics

Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of our study sample. Females represented slightly more than half the sample, particularly in the inland communities (57%). The distribution of all obesity-related traits varied by gender (P-value <0.05), with the exception of waist and triceps circumferences. All traits exhibited statistically significant heritability estimates, ranging from 28% for waist circumference and abdominal skinfold to 47% for adiponectin and triceps circumference (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the study sample.

| Male (n=454) | Female (n=528) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Community group, n (%)a | |||

| Coastal | 214 (51)b | 204 (49) | 0.63 |

| Inland | 240 (43) | 324 (57) | 0.0004 |

| Age, years | 36 (35–38) | 38 (37–40) | 0.072 |

| δ15N, ‰ | 8.8 (8.7–8.9) | 9.2 (9.1–9.3) | 0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.6 (25.2–26.0) | 28.2 (27.7–28.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Percent body fat | 21.2 (20.4–21.9) | 35.5 (34.8–36.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Circumference, cm | |||

| Triceps | 44.7 (44.7–44.7) | 44.8 (44.8–44.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Hip | 30.4 (30.1–30.8) | 30.4 (30.0–31.0) | 0.822 |

| Thigh | 50 (49–50) | 51 (50–51) | 0.007 |

| Waist | 88 (87–90) | 90 (89–91) | 0.081 |

| Skinfold, mm | |||

| Abdominal | 16 (15–17) | 29 (28–30) | < 0.0001 |

| Subscapular | 13 (12–13) | 23 (22–24) | < 0.0001 |

| Triceps | 11.2 (10.7–11.7) | 25.6 (24.8–26.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Thigh | 11.9 (11.3–12.5) | 30.0 (29.1–31.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Adiponectin, mg/mL | 9.0 (8.6–9.5) | 9.9 (9.4–10.3) | 0.009 |

| Leptin, ng/mL | 2.6 (2.4–2.8) | 13.4 (12.6–14.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Ghrelin, pg/mL | 37 (36–39) | 40 (38–41) | 0.01 |

P-value was based on binomial distribution.

For continuous variables, we report means of untransformed traits and 95% confidence intervals in parentheses; for the categorical variable of community group, we report counts and percentages in parentheses. P-values were based on a 2-sample t-test using transformed trait values.

Table 2.

Heritability estimates of obesity-related traits.

| Heritability | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin | 0.47 | 6.0×10−18 |

| Leptin | 0.30 | 1.3×10−6 |

| Ghrelin | 0.42 | 9.7×10−11 |

| BMI | 0.41 | 1.2×10−8 |

| Circumference | ||

| Triceps | 0.47 | 2.6×10−11 |

| Hip | 0.43 | 1.1×10−9 |

| Thigh | 0.39 | 4.0×10−7 |

| Waist | 0.28 | 4.5×10−5 |

| Percent body fat | 0.31 | 5.5×10−6 |

| Skinfold | ||

| Abdominal | 0.28 | 4.3×10−6 |

| Subscapular | 0.30 | 1.1×10−6 |

| Thigh | 0.35 | 2.0×10−7 |

| Triceps | 0.36 | 1.0×10−7 |

3.2 Genomewide linkage scan results

We present results for the genome-wide linkage scan in Table 3. We considered peaks that exceeded a LOD score of 2 or greater as significant. All of the traits, except leptin, showed evidence for areas of linkage (the highest LOD score for leptin was 1.9, just below our cutoff). Several traits shared linkage regions, including adiponectin and triceps skinfold (10q26.13-10q26.2); triceps skinfold, waist circumference, percent body fat, and BMI (11p15.1-11p13); waist circumference and percent body fat (4p16.1-4p15.1); and thigh and subscapular skinfold (5q32-5q42).

Table 3.

Observed maximum logarithm of the odds (LOD) score and linkage regions with LOD>2.

| Chromosome Bands | Peak LOD | Start SNP | Start Position | End SNP | End Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin | |||||

| 3q26.33-3q29 | 3.65 | rs2049769 | 181,136,696 | rs711995 | 195,842,216 |

| 10q26.13-10q26.2 | 2.20 | rs10899 | 125,758,210 | rs1255135 | 130,007,627 |

| 22q13.1-22q13.31 | 2.12 | rs137636 | 38,052,423 | rs12170546 | 42,753,666 |

| Triceps circumference | |||||

| 11q24.1-11q25 | 2.54 | rs676943 | 121,553,535 | rs965493 | 131,145,305 |

| BMI | |||||

| 4p15.33-4p15.32 | 2.04 | rs763318 | 12,572,672 | rs1357233 | 16,752,474 |

| 11p15.4-11p15.3 | 2.64 | rs892336 | 5,559,255 | rs1365406 | 12,519,296 |

| Percent body fat | |||||

| 4p16.1-4p15.2 | 2.72 | rs881641 | 9,742,845 | rs1533132 | 24,921,455 |

| 11p15.4-11p15.1 | 2.79 | rs906895 | 6,236,824 | rs4348874 | 18,748,760 |

| Ghrelin | |||||

| 13q12.13-13q13.3 | 2.69 | rs306395 | 25,348,564 | rs737645 | 38,931,693 |

| Subscapular skinfold | |||||

| 5q33.1-5q34 | 2.23 | rs1560657 | 149,971,205 | rs7717940 | 161,694,190 |

| Thigh circumference | |||||

| 8q21.11-8q21.13 | 2.18 | rs1007750 | 74,148,846 | rs10105219 | 84,019,730 |

| 9q34.2-9q34.3 | 2.12 | rs7023064 | 136,236,772 | rs7357733 | 140,123,767 |

| Thigh skinfold | |||||

| 5q32-5q34 | 2.58 | rs887346 | 149,576,185 | rs1030154 | 164,983,908 |

| Triceps skinfold | |||||

| 10q26.13-10q26.2 | 2.14 | rs4962480 | 127,378,272 | rs1255135 | 130,007,627 |

| 11p15.1-11p13 | 2.21 | rs1470251 | 20,078,168 | rs509628 | 31,491,931 |

| Waist circumference | |||||

| 4p16.1-4p15.1 | 3.11 | rs881641 | 9,742,845 | rs902658 | 31,864,983 |

| 11p15.4-11p13 | 3.34 | rs1451724 | 3,813,244 | rs750780 | 33,874,170 |

3.3 Targeted association results

Results of the targeted association testing of individual SNPs located in regions identified by genome wide linkage are presented in Table 4. Adiponectin, body fat, thigh circumference, thigh skinfold, and waist circumference each had a single SNP that showed significant associations. In models investigating plasma adiponectin and percent body fat, we observed statistically significant interactions between genotype and n-3 PUFA intake (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Associations between single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within linkage peaks and obesity related traits.

| SNP | Chr | Gene | P-valuea | P-valueb | P-valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin | rs2048417 | 3 | -- | 0.58 | 0.001 | 0.0006 |

| Percent body fat | rs730414 | 11 | BTBD10 | 0.48 | 0.0009 | 0.0004 |

| Thigh circumference | rs1007750 | 8 | SBSPON | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | 0.03 |

| Thigh skinfold | rs878953 | 5 | -- | 0.0004 | 0.003 | 0.30 |

| Waist circumference | rs1596854 | 11 | LUZP2 | 0.0003 | 0.002 | 0.30 |

P-value for the model adjusted for sex, age, n-3 PUFA intake, community group, and additive genotype.

P-value for the model with all the terms from the additive model plus an interaction between the additive genotype and n-3 PUFA intake.

P-value for the likelihood ratio test for comparing the additive model with the full model (i.e. for the interaction between genotype and n-3 PUFA intake).

Figure 1.

Interactions between genotype and the quarter of n-3 PUFA intake as measured by δ15N for A) rs2048417 in the adiponectin analysis and B) rs730414 in the percent body fat analysis.

3.4 Bioinformatic analysis results

Table 5 lists the top candidate genes for each of the linkage peaks identified in this study. At least one of the proposed candidate genes has been previously associated with obesity for almost all linkage peaks [36]. The exception is 10q26.13-10q26.2, which we found to be linked to adiponectin and triceps skinfold. In that region, TOPP Gene was the only algorithm that identified potential candidate genes, DOCK1 and PTPRE. Although neither DOCK1 nor PTPRE have been previously associated with obesity traits, they are paralogs for known obesity susceptibility genes: DOCK5 and PTPRA, PTPRD, and PTPRF, respectively [37, 38].

Table 5.

Putative candidate genes from bioinformatic analysis.

| Chromosome | Training list genes | Putative candidate genes |

|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin | ||

| 3q26.33-3q29 | ETV5 | |

| 10q26.13-10q26.2 | DOCK1, PTPRE | |

| 22q13.1-22q13.31 | EP300, SREBF2 | |

| Triceps circumference | ||

| 11q24.1-11q25 | TIRAP, HSPA8, CBL | |

| BMI | ||

| 4p15.33-4p15.32 | PPARGC1A | |

| 11p15.4-11p15.3 | BDNF | |

| Percent body fat | ||

| 4p16.1-4p15.2 | PPARGC1A | |

| 11p15.4-11p15.1 | BDNF | |

| Ghrelin | ||

| 13q12.13-13q13.3 | PDX1 | |

| Subscapular skinfold | ||

| 5q33.1-5q34 | ADRA1B, IL21B | |

| Thigh circumference | ||

| 8q21.11-8q21.13 | FABP4 | |

| 9q34.2-9q34.3 | RXRA, GRIN1, EHMT1 | |

| Thigh skinfold | ||

| 5q32-5q34 | ADRA1B, IL21B | |

| Triceps skinfold | ||

| 10q26.13-10q26.2 | DOCK1, PTPRE | |

| 11p15.1-11p13 | BDNF | |

| Waist circumference | ||

| 4p16.1-4p15.1 | PPARGC1A | |

| 11p15.4-11p13 | BDNF | |

4. DISCUSSION

We conducted a genome-wide linkage scan and targeted SNP association analysis for obesity-related traits in a cross-sectional sample of Yup’ik people. In agreement with previous studies of fat distribution genetics [39], we found distinct signals underlying different obesity phenotypes, e.g. different skinfold thicknesses. Several of our findings overlapped with known linkage peaks, previously identified candidate genes, or proposed candidate genes from mouse studies. Specifically, the 11p15.4-11p13 region, which was significantly linked with BMI, waist circumference, body fat percent and triceps skinfold, contains the obesity candidate gene BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor, geneID 627). BDNF and its tyrosine kinase receptor are expressed in hypothalamic nuclei associated with eating behaviors [40] and have been linked to body weight and eating disorders in European populations [41]. Several BDNF variants were robustly associated with BMI in a large-scale GWAS comprised of Europeans and African Americans [42]. However, we have previously reported null associations between the nonsynonymous variant rs6265 in the BDNF gene and obesity phenotypes in Yup’ik people [17]. One reason for this discrepancy could be the low minor allele frequency (0.04) at the rs6265 locus in our study sample [17]. It is likely that the linkage peak observed in this study is driven by other variants in the 11p15.4-11p13 region. Other findings on chromosome 11 included a linkage peak for triceps circumference in the 11q24.1-11q25 region, located adjacent to but not overlapping with the previously reported peak for percent body fat in a Pima Indian population [43].

The linkage peak for adiponectin on chromosome 3 includes two known and biologically plausible candidate genes, namely ETV5 (ets variant 5, geneID 2119) and ADIPOQ (adiponectin, C1Q and collagen domain containing, geneID 9307). While the role of ADIPOQ variation in metabolic phenotypes has long been established [44], evidence indicates that ETV5 also merits attention. A polymorphism in ETV5, rs117016164, showed a robust association with circulating plasma adiponectin in Filipino women [45]. Another common variant in ETV5, rs7647305, was correlated with BMI and weight in a large-scale GWAS [42] as well as with hip and thigh circumference in Yup’ik people [17]. We also found an adiponectin peak on chromosome 10, located adjacent to a recently identified novel locus near WDR11-FGFR2 that was linked to circulating adiponectin, blood lipids, and BMI-adjusted waist-to-hip ratio in East Asian populations [46]. Notably, the same 10q26.2 region showed robust evidence of linkage to plasma triglycerides in another Native American population: the Arizona subset of the Strong Heart Family Study [47]. Overall, our findings corroborate previously reported observations that the majority of adiponectin-linked loci have pleiotropic effects, particularly on circulating adiponectin levels, type 2 diabetes risk, and obesity traits [44].

Our study also provides preliminary evidence for a novel peak on chromosome 8 for thigh circumference. Both targeted SNP and bioinformatic analysis of the 8q21.11-8q21.13 genomic region suggested FABP4 (fatty acid binding protein 4, geneID 2167), which encodes a fatty acid binding protein that is highly expressed in adipose tissue and macrophages and is detected in high concentrations in serum. In children, FABP4 variants were significantly associated with measures of insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism and inflammation [48]. In conjunction with that evidence, our findings warrant further exploration of the role of FABP4 in obesity pathogenesis.

Follow-up association analysis of variants under the linkage peaks identified five SNPs associated with adiponectin, percent body fat, thigh circumference, thigh skinfold, and waist circumference (Table 4). The genes tagged by three of these SNPs (rs730414 in BTBD10 (BTB (POZ) domain containing 10, geneID 84280), rs1007750 in SBSPON (somatomedin B and thrombospondin, geneID 157869), and rs1596854 in LUZP2 (leucine zipper protein 2, geneID 338645) have no obvious connections with obesity related phenotypes, although all are relatively newly identified and have not been studied extensively. The two remaining SNPs (rs2048417 and rs878953) are located in non-coding regions, and careful data mining discovered no indication of other types of known functional genomic elements.

Using bioinformatic analysis, we identified several putative candidate genes for the linkage peaks reported in this study. In addition to the previously discussed FABP4, we found PPARGC1A from the BMI, waist circumference, and body fat percent analyses, SREBF2 from the adiponectin peak, and PDX1 from the ghrelin peak especially noteworthy. PPARGC1A (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha, geneID 10891) encodes a master metabolic regulator previously implicated in insulin resistance [49]. Interestingly, a nonsynonymous polymorphism in PPARGC1A was linked to BMI in Polynesians, positioning PPARGC1A as a strong “thrifty gene” candidate in that population [50]. Other studies have implicated PPARGC1A expression and methylation in diet-induced metabolic changes, highlighting the biological relevance of our findings [49]. In the adiponectin analysis, the bioinformatic algorithm identified SREBF2 (sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 2, geneID 6721), an important transcription factor involved in cholesterol homeostasis that is downregulated in adipocytes from obese humans and upregulated following weight loss [51]. Finally, PDX1 (pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1, geneID 3651) emerged as a likely candidate from the ghrelin peak. PDX1 encodes a transcriptional regulator that plays a critical role in insulin metabolism and is implicated in the monogenic form of early onset diabetes [52]. While its direct effects on the ghrelin concentrations remain to be tested in humans, a recent exome sequencing study discovered an association between a rare frameshift mutation in PDX1 and the risk of type 2 diabetes in the general population [53]. It is worth noting that despite the implications for diabetes reported in other population, we did not find evidence of linkage in our previously published analysis of fasting glucose [22], likely due to the uniqueness of the Yup’ik population or chance.

We established that the association between genotype and two of the obesity traits (rs2048417 with adiponectin and rs730414 with body fat percent) is mediated by n-3 PUFA intake (Table 4). Previously, high levels of marine-derived n-3 PUFAs in the traditional Yup’ik diet have been suggested to play a role in the “healthy obesity” phenotype, in part, through gene-diet interactions [17, 54]. The interaction of n-3 PUFA intake with the rs730414 genotype is particularly interesting. Although rs730414 is located in the intron of BTBD10, it is also in linkage disequilibrium with the gene encoding parathyroid hormone (PTH, geneID 5741). PTH plays a critical role in calcium homeostasis and is involved in vitamin D metabolism. The traditional diet of the Yup’ik people, which contains a large amount of marine-derived fatty acids, is also rich in vitamin D [55]. Additionally, variation in PTH and the gene encoding the vitamin D receptor (VDR, geneID 7421) has been tied to obesity-related traits. Therefore, the gene-diet interactions observed in our study are biologically plausible and warrant further investigation.

Our study has several important strengths. In addition to large sample size, an accurate biomarker of n-3 PUFA, and a wide range of n-3 PUFA intake, we were able to leverage data from extended family structures. Extended pedigrees provide one of the most powerful approaches for studying the genetics of quantitative traits, and the use of complex pedigrees that span multiple households and communities provide significant statistical power for discriminating between shared genetic and environmental effects. However, our findings must not be interpreted as causal for several reasons. First, the SNPs identified by targeted analysis may not represent the true susceptibility variant but rather “tag” the causal mutation. Second, the phenotypes that we examined are complex traits that are likely to be determined by a combination of genetic and environmental effects. Finally, the novel genomic regions for adiponectin and thigh circumference have not yet been replicated in other populations, and thus need further investigation. Additionally, given the genetic and environmental uniqueness of our study population, the generalizability of our findings may be limited, although replication analyses of our top hits in other Native groups are certainly warranted. Once successfully validated, these preliminary results will advance current understanding of the genetic and dietary determinants of obesity-related traits in communities with low prevalence of obesity-related comorbidities.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the work of the community field research assistants to recruit our participants and collect the data. We are sincerely grateful to all study participants and their communities for welcoming and teaching us about the Yup’ik way of life.

FUNDING

The study was supported by the following National Institute of Health grants: K01DK080188 (LKV), DK074842 and RR016430 (BBB), DK056336 (DBA). Genotyping services were provided by the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR), funded through a federal contract (HHSN268200782096C) from the National Institutes of Health to Johns Hopkins University.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- n-3 PUFA

omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids

- CANHR

Center for Alaska Native Health Research

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- VLDL

very low density lipoprotein

- δ15N

nitrogen stable isotope ratio

- RBC

red blood cell

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- LOD

logarithm of the odds

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

LKV conducted bioinformatic analyses, interpreted the findings, and wrote the manuscript; HWW conducted linkage and association analyses; SA and DJL interpreted the findings and assisted in writing the manuscript; DBA, BB and HKT designed research, interpreted the findings, and edited the manuscript; PJH, KLS, DMO, and SEH conducted research. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Laura Kelly Vaughan, Email: lkvaughn@uab.edu.

Howard W. Wiener, Email: hwiener@uab.edu.

Stella Aslibekyan, Email: stella7@gmail.com.

David B. Allison, Email: dallison@uab.edu.

Peter J. Havel, Email: pjhavel@ucdavis.edu.

Kimber L. Stanhope, Email: klstanhope@ucdavis.edu.

Diane M. O’Brien, Email: dmobrien@alaska.edu.

Scarlett E. Hopkins, Email: scarlett.hopkins@gmail.com.

Dominick J. Lemas, Email: dominick.lemas@ucdenver.edu.

Bert B. Boyer, Email: bboyer@alaska.edu.

Hemant K. Tiwari, Email: htiwari@uab.edu.

References

- 1.Laramie JM, Wilk JB, Williamson SL, Nagle MW, Latourelle JC, Tobin JE, et al. Multiple genes influence BMI on chromosome 7q31-34: the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:2182–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung WK, Leibel RL. Considerations regarding the genetics of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(Suppl3):S33–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung WW, Mao P. Recent advances in obesity: genetics and beyond. ISRN Endocrinol. 2012;2012:536905. doi: 10.5402/2012/536905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rankinen T, Zuberi A, Chagnon YC, Weisnagel SJ, Argyropoulos G, Walts B, et al. The human obesity gene map: the 2005 update. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:529–644. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Sayed Moustafa JS, Froguel P. From obesity genetics to the future of personalized obesity therapy. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:1–12. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandholt CH, Hansen T, Pedersen O. Beyond the fourth wave of genome-wide obesity association studies. Nut Diabetes. 2012;2:e37. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2012.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saunders CL, Chiodini BD, Sham P, Lewis CM, Abkevich V, Adeyemo AA, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage studies in BMI and obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2263–75. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peltonen L, Palotie A, Lange K. Use of population isolates for mapping complex traits. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:182–90. doi: 10.1038/35042049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemas DJ, Wiener HW, O’Brien DM, Hopkins S, Stanhope KL, Havel PJ, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A gene are associated with variation in body composition and fasting lipid traits in Yup’ik Eskimos. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:175–84. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P018952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebbesson SO, Schraer CD, Risica PM, Adler AI, Ebbesson L, Mayer AM, et al. Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in three Alaskan Eskimo populations. The Alaska-Siberia Project Diabetes Care. 1998;21:563–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schraer CD, Risica PM, Ebbesson SO, Go OT, Howard BV, Mayer AM. Low fasting insulin levels in Eskimos compared to American Indians: are Eskimos less insulin resistant? Int J Circumpolar Health. 1999;58:272–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumacher C, Davidson M, Ehrsam G. Cardiovascular disease among Alaska Natives: a review of the literature. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2003;62:343–62. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v62i4.17579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young TK, Bjerregaard P, Dewailly E, Risica PM, Jørgensen ME, Ebbesson SE. Prevalence of obesity and its metabolic correlates among the circumpolar Inuit in 3 countries. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:691–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyer BB, Mohatt GV, Plaetke R, Herron J, Stanhope KL, et al. Metabolic syndrome in Yup’ik Eskimos: the Center for Alaska Native Health Research (CANHR) Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2535–40. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohatt GV, Plaetke R, Klejka J, Luick B, Lardon C, Bersamin A. The Center for Alaska Native Health Research Study: a community-based participatory research study of obesity and chronic disease-related protective and risk factors. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66:8–18. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i1.18219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makhoul Z, Kristal AR, Gulati R, Luick B, Bersamin A, Boyer B, et al. Associations of very high intakes of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids with biomarkers of chronic disease risk among Yup’ik Eskimos. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:777–85. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemas DJ, Klimentidis YC, Wiener HH, O’Brien DM, Hopkins SE, Allison DB, et al. Obesity polymorphisms identified in genome-wide association studies interact with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and modify the genetic association with adiposity phenotypes in Yup’ik people. Genes Nutr. 2013;8:495–505. doi: 10.1007/s12263-013-0340-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klimentidis YC, Lemas DJ, Wiener HW, O’Brien DM, Havel PJ, Stanhope KL, et al. CDKAL1 and HHEX are associated with type 2 diabetes-related traits among Yup’ik people. J Diabetes. 2014;6:251–9. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lohman TG, Roche AF. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goropashnaya AV, Herron J, Sexton M, Havel PJ, Stanhope KL, Plaetke R, et al. Relationships between plasma adiponectin and body fat distribution, insulin sensitivity, and plasma lipoproteins in Alaskan Yup’ik Eskimos: the Center for Alaska Native Health Research Study. Metabolism. 2009;58:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Brien DM, Kristal AR, Jeannet MA, Wilkinson MJ, Bersamin A, Luick B. Red blood cell δ15N: a novel biomarker of dietary eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:913–9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aslibekyan S, Vaughan LK, Wiener HW, Lemas DJ, YC, Havel PJ, et al. Evidence for novel genetic loci associated with metabolic traits in Yup’ik people. Am J Hum Biol. 2013;25:673–80. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien DM, Kristal AR, Nash SH, Hopkins SE, Luick BR, Stanhope KL, et al. A stable isotope biomarker of marine food intake captures associations between n-3 fatty acid intake and chronic disease risk in a Yup’ik study population, and detects new associations with blood pressure and adiponectin. J Nutr. 2014;144:706–13. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.189381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Box GE, Cox DR. An analysis of transformations. J Roy Stat Soc Ser B. 1964;26:211–52. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity. 2005;95:221–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyholt DR. A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:765–9. doi: 10.1086/383251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson AD, Handsaker RE, Pulit SL, Nizzari MM, O’Donnell CJ, De Bakker PI. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2938–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liefeld T, Reich M, Gould J, Zhang P, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GeneCruiser: a web service for the annotation of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3681–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyle AP, Hong EL, Hariharan M, Cheng Y, Schaub MA, Kasowski M, et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22:1790–7. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu W, Gwinn M, Clyne M, Yesupriya A, Khoury MJ. A navigator for human genome epidemiology. Nat Genet. 2008;40:124–5. doi: 10.1038/ng0208-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guberman JM, Ai J, Arnaiz O, Baran J, Blake A, Baldock R, et al. BioMart Central Portal: an open database network for the biological community. Database (Oxford) 2011;2011:bar041. doi: 10.1093/database/bar041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safran M, Dalah I, Alexander J, Rosen N, Iny Stein T, Shmoish M, et al. GeneCards Version 3: the human gene integrator. Database (Oxford) 2010;2010:baq020. doi: 10.1093/database/baq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohler S, Bauer S, Horn D, Robinson PN. Walking the interactome for prioritization of candidate disease genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:949–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J, Bardes EE, Aronow BJ, Jegga AG. ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W305–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tranchevent LC, Barriot R, Yu S, Van Vooren S, Van Loo P, Coessens B, et al. ENDEAVOUR update: a web resource for gene prioritization in multiple species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W377–84. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu W, Clyne M, Khoury MJ, Gwinn M. Phenopedia and Genopedia: disease-centered and gene-centered views of the evolving knowledge of human genetic associations. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:145–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Sayed Moustafa JS, Eleftherohorinou H, de Smith AJ, Andersson-Assarsson JC, Alves AC, Hadjigeorgiou E, et al. Novel association approach for variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) identifies DOCK5 as a susceptibility gene for severe obesity. Hum Molec Genet. 2012;21:3727–38. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad F, Azevedo JL, Cortright R, Dohm GL, Goldstein BJ. Alterations in skeletal muscle protein-tyrosine phosphatase activity and expression in insulin-resistant human obesity and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:449–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI119552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouchard C. Genetic determinants of regional fat distribution. Hum Reprod. 1997;12 (Suppl 1):1–5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.suppl_1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakazato M, Hashimoto K, Shimizu E, Niitsu T, Iyo M. Possible involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in eating disorders. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:355–61. doi: 10.1002/iub.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ribases M, Gratacos M, Aranda-Fernandez F, Bellodi L, Boni C, Anderluh M, et al. Association of BDNF with restricting anorexia nervosa and minimum body mass index: a family-based association study of eight European populations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:428–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, Steinthorsdottir V, Sulem P, Helgadottir A, et al. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet. 2009;41:18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norman RA, Thompson DB, Foroud T, Garvey WT, Bennett PH, Bogardus C, et al. Genomewide search for genes influencing percent body fat in Pima Indians: suggestive linkage at chromosome 11q21-q22. Pima Diabetes Gene Group. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:166–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breitfeld J, Stumvoll M, Kovacs P. Genetics of adiponectin. Biochimie. 2012;10:2157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Croteau-Chonka DC, Wu Y, Li Y, Fogarty MP, Lange LA, Kuzawa CW, et al. Population-specific coding variant underlies genome-wide association with adiponectin level. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:463–71. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu Y, Gao H, Li H, Tabara Y, Nakatochi M, Chiu YF, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for adiponectin levels in East Asians identifies a novel locus near WDR11-FGFR2. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1108–19. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X, Monda KL, Goring HH, Haack K, Cole SA, Diego VP, et al. Genome-wide linkage scan for plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol, apolipoprotein A-1 and triglyceride variation among American Indian populations: the Strong Heart Family Study. J Med Genet. 2009;46:472–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.063891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khalyfa A, Bhushan B, Hegazi M, Kim J, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Bhattacharjee R, et al. Fatty-acid binding protein 4 gene variants and childhood obesity: potential implications for insulin sensitivity and CRP levels. Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gillberg L, Jacobsen SC, Ronn T, Brons C, Vaag A. PPARGC1A DNA methylation in subcutaneous adipose tissue in low birth weight subjects-- impact of 5 days of high-fat overfeeding. Metabolism. 2014;63:263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Myles S, Lea RA, Ohashi J, Chambers GK, Weiss JG, Hardouin E, et al. Testing the thrifty gene hypothesis: the Gly482Ser variant in PPARGC1A is associated with BMI in Tongans. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oberkolfer H, Fukushima N, Esterbauer H, Krempler F, Patsch W. Sterol regulatory element binding proteins: relationship of adipose issue gene expression with obesity in humans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1575:75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stoffers DA, Ferrer J, Clarke WL, Habener JF. Early-onset type-II diabetes mellitus (MODY4) linked to IPF1. Nat Genet. 1997;17:138–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinthorsdottir V, Thorleifsson G, Sulem P, Helgason H, Grarup N, Sigurdsson A, et al. Identification of low-frequency and rare sequence variants associated with elevated or reduced risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2014;46:294–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemas DJ, Wiener HW, O’Brien DM, Hopkins S, Stanhope KL, Havel PJ, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A gene are associated with variation in body composition and fasting lipid traits in Yup’ik Eskimos. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:175–84. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P018952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luick B, Bersamin A, Stern JS. Locally harvested foods support serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D sufficiency in an indigenous population of Western Alaska. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2014;73 doi: 10.3402/ijch.v73.22732. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]