SUMMARY

Therapeutics such as lapatinib that target ERBB2 often provide initial clinical benefit but resistance frequently develops. Adaptive responses leading to lapatinib resistance involve reprogramming of the kinome through reactivation of ERBB2/ERBB3 signaling and transcriptional upregulation and activation of multiple tyrosine kinases. The heterogeneity of induced kinases prevents their targeting by a single kinase inhibitor, underscoring the challenge of predicting effective kinase inhibitor combination therapies. We hypothesized that to make the tumor response to single kinase inhibitors durable, the adaptive kinome response itself must be inhibited. Genetic and chemical inhibition of BET bromodomain chromatin readers suppresses transcription of many lapatinib-induced kinases involved in resistance including ERBB3, IGF1R, DDR1, MET, and FGFRs, preventing downstream SRC/FAK signaling and AKT reactivation. Combining inhibitors of kinases and chromatin readers prevents kinome adaptation by blocking transcription, generating a durable response to lapatinib and overcoming the dilemma of heterogeneity in the adaptive response.

INTRODUCTION

The human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/ERBB2) is a member of the EGFR/ERBB family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). The ERBB2 oncogene is amplified or overexpressed in roughly 25% of breast cancers and serves as the primary driver of tumor cell growth in the majority of these cancers. Clinical trials indicate that ERBB2 “addiction” is fundamental to the behavior of these tumors and targeting ERBB2 has proven to be an effective treatment in a subset of ERBB2+ breast cancer patients. Approved ERBB2-targeting therapies include the monoclonal antibodies trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody drug conjugate, in addition to the ATP-competitive EGFR/ERBB2 inhibitor lapatinib. However, even with initial dramatic clinical responses to these therapies as single agents or in combination, patients frequently relapse as resistance develops. The preferred dimerization partner of ERBB2 is ERBB3/HER3, and a major mechanism of lapatinib resistance is due to transcriptional and post-translational upregulation of ERBB3 (Amin et al., 2010; Garrett et al., 2011). Multiple other kinases contribute to the resistant phenotype as well, including IGF1R, MET, FGFR2, FAK, and SRC family kinases (Azuma et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2011; Rexer and Arteaga, 2012).

Characteristically, tumors have a remarkable resiliency toward kinase-directed therapeutics, capable of rewiring their signaling networks to evade effects of the drug and develop resistance. Targeting specific signaling nodes crucial for tumor growth, such as PI3K, AKT, mTOR, BRAF, and MEK elicits adaptive kinome responses that upregulate alternative kinase signaling networks or reactivate the targeted pathway to overcome inhibitor treatment (Chandarlapaty et al., 2011; Duncan et al., 2012; Rodrik-Outmezguine et al., 2011; Serra et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2014). This “adaptive kinome reprogramming” is mechanistically based on the disruption of feedback and feedforward regulatory loops that serve to bypass the inhibition and rapidly generate resistance to targeted therapies. Adaptive bypass responses in tumor cells are a major reason that kinase inhibitors often do not have durable responses in the treatment of cancer patients.

To understand these bypass mechanisms toward ERBB2 inhibition, we investigated lapatinib-induced kinome adaptation in a panel of ERBB2+ cell lines using a chemical proteomics method. We find the adaptive kinome response to lapatinib involves the activation of multiple RTKs, SRC family kinases, FAK, and members of other intracellular networks downstream of RTKs. We additionally identify significant heterogeneity in this response among different ERBB2+ cell lines. Multiple kinases contribute to escape from lapatinib-mediated growth inhibition, consistent with a shift in dependency to alternative signaling nodes in addition to ERBB2. This prevents their targeting by a single kinase inhibitor, underscoring the difficulty of choosing the most effective kinase inhibitor combinations to treat ERBB2+ tumors. These results suggest that chasing combination therapies with multiple kinase inhibitors has a poor likelihood of success. We approached this problem with the hypothesis that lapatinib would be more durable in inhibiting ERBB2+ cell growth if we could block the adaptive reprogramming response itself. We target chromatin readers involved in transcriptional upregulation of RTKs that drive the adaptive signaling networks responsible for lapatinib resistance. By inhibiting the onset of the adaptive response, we achieve durable growth inhibition greater than that observed by targeting several different kinases with inhibitors. Our studies demonstrate that inhibiting the adaptive kinome response provides a method to address the heterogeneity in kinome adaptation and a mechanism to prevent resistance to kinase inhibitors.

RESULTS

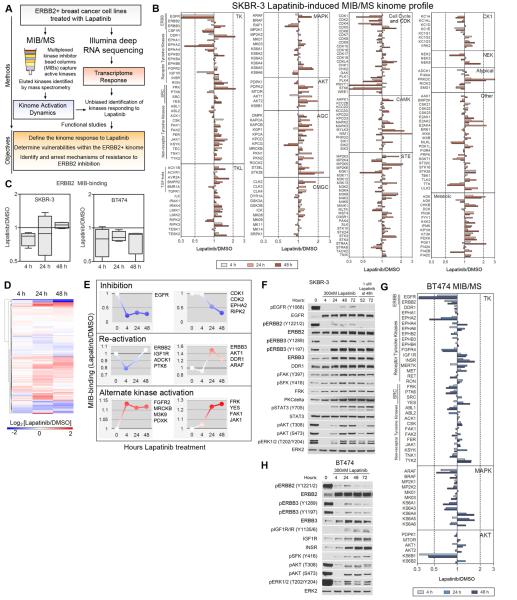

Lapatinib induces dynamic adaptive kinome responses in ERBB2+ breast cancer cells

We used Multiplexed Inhibitor Beads coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MIB/MS) to quantitatively measure dynamic changes in kinase activity on a proteomic scale (Figure 1A) (Duncan et al., 2012). SKBR-3 and BT474 luminal ERBB2+ breast cancer cells were treated with lapatinib for 4, 24, and 48 h (Figures 1B, S1A, S1B). The kinome of SKBR-3 cells is remarkably responsive to lapatinib with many kinases displaying enhanced MIB-binding, indicative of increased kinase activity relative to untreated cells. Lapatinib induces growth inhibition and there is a concomitant time-dependent loss of MIB-binding of cell cycle-regulating kinases, correlating with inhibition of their kinase activity. Loss of ERBB2 and EGFR MIB-binding is observed in both SKBR-3 and BT474 cells at 4 h, but in SKBR-3 cells, ERBB2 binding has returned to untreated levels after 48 h, indicating reactivation of ERBB2 (Figures 1B, 1C). In BT474 cells, ERBB2 remains inhibited at 48 h. ERBB3 binding to MIBs increases within 24 h, consistent with ERBB3 upregulation in response to lapatinib (Amin et al., 2010). The time course illustrates the dynamic behavior of the kinome with kinases having temporal differences in regulation of their activity (Figures 1D, 1E, S1A). EGFR displays rapid and sustained loss of MIB-binding, while most inhibited kinases demonstrate a progressive loss of MIB-binding over 48 h of lapatinib treatment. Some kinases display similar reactivation dynamics to ERBB2 (IGF1R, PTK6, ADCK1), suggesting they operate in a common regulatory network. Others such as ERBB3, AKT1, DDR1, and ARAF are initially inhibited but reactivate with greater MIB-binding than their baseline control activity. Kinases such as FGFR2 respond with increased activity within 4 h while other tyrosine kinases (TKs) such as FRK, YES, FAK1, and JAK1 become progressively more activated, suggesting they are regulated downstream of the kinases driving the initial adaptive kinome response. Western blots confirm MIB/MS results, with inhibition of ERBB family phosphorylation and downstream signaling (AKT, ERK1/2) at 4 h and reactivation by 48 h (Figure 1F). Total protein levels of EGFR, ERBB2, ERBB3, DDR1, FRK, and PKCδ increase over time, along with activation loop phosphorylation of FAK and SRC family kinases (SFKs). STAT3 activating phosphorylation is induced by lapatinib, downstream of JAK signaling and independent of SFK signaling (Figure S1C). Addition of a higher dose of lapatinib (1μM) after 48 h inhibits partial reactivation of EGFR, ERBB2 and ERBB3 phosphorylation, but effects on downstream FAK/SFK/AKT/ERK signaling are limited.

Figure 1. Lapatinib induces dynamic kinome responses.

(A) Flow chart for experimental design.

(B) MIB/MS kinome activation dynamics over 48 h of 300nM lapatinib treatment in SKBR-3 cells. Ratios greater than 1 indicate increased MIB-binding (increased activity) and values less than 1 indicate decreased MIB-binding (decreased activity) relative to control cells treated with DMSO. Data presented is the average of four biological replicates.

(C) MIB-binding dynamics suggest reactivation of ERBB2 in SKBR-3 cells but continued suppression in BT474 cells.

(D) Hierarchical clustering of MIB-binding ratios in SKBR-3 cells identifies clusters of dynamic kinase behavior.

(E) Dynamics of a select set of kinases illustrates multiple behaviors in response to lapatinib. Four points graphically indicate 0, 4, 24, and 48 h MIB-binding. Blue, inhibited; red, activated.

(F) Western blots validate MIB/MS results and identify upregulation of ERBB3, DDR1, FRK, and PKCδ and increased activation of FAK, SRC family kinases (SFKs), and STAT3 in response to lapatinib. AKT and ERK1/2 are inhibited at 4 h but become reactivated over 72 h. Treatment with 1µM lapatinib re-inhibits EGFR and ERBB2 but has little effect on other kinases.

(G) BT474 MIB-binding dynamics of tyrosine kinases and MEK/ERK and AKT/mTOR pathways.

(H) Western blots indicate upregulation of ERBB3, INSR, and IGF1R total levels and increase in SFK phosphorylation after lapatinib treatment in BT474 cells.

Also see Figures S2

BT474 cells generate a less-robust adaptive response with more kinases inhibited than activated (Figures 1G, S1B). BT474 cells display a progressive loss of MEK/ERK MIB binding, but a rebound in AKT signaling similar to SKBR-3 cells, with initial inhibition of AKT1 and overall increase in AKT2 MIB-binding (Figures 1B, 1G). Interestingly, MEK/ERK MIB-binding in SKBR-3 cells is seemingly unchanged by short-term treatment with lapatinib in the 4 h MIB/MS profile, suggesting additional inputs regulate their activity. Western blots of BT474 cells treated with lapatinib demonstrate little reactivation of ERBB2 and ERBB3, with progressively increasing IGF1R and INSR phosphorylation and total levels, SFK phosphorylation, and a partial return of AKT and ERK1/2 activity (Figure 1H).

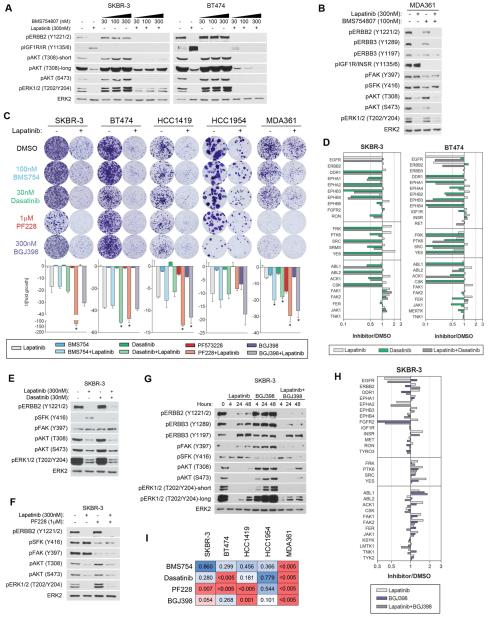

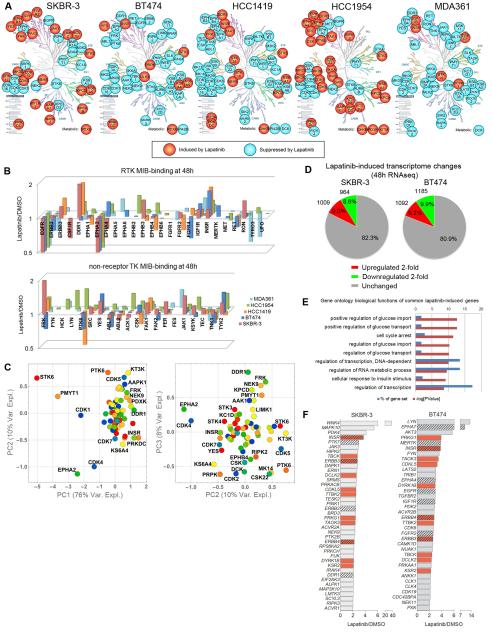

MIB/MS defines heterogeneity in the adaptive kinome response to lapatinib

Across four independent MIB/MS runs for SKBR-3 cells, we defined a signature of kinases with highly statistically significant changes in MIB-binding after 48 h lapatinib treatment (Figure 2A). Kinases with enhanced MIB-binding (increased activity) include the RTKs DDR1, EPHB3, and FGFR2, non-receptor TKs JAK1, FAK1, and SFKs FRK and YES, and multiple kinases involved in cytoskeletal regulation (MYLK3, NEK9, MARK2, MRCKB, LIMK2). The CMGC kinases CDK5, -10, and -17, and AGC kinases KPCD (PKCδ) and KS6A5 (RSK5) are also activated. PRKDC (DNA damage sensor), STK3 (HIPPO pathway/pro-apoptotic signaling), and AAPK1 (AMP-activated) are activated by multiple growth-inhibiting treatments and likely represent a stress-induced kinase response. Kinases with loss of MIB binding within the signature include multiple cell cycle regulating kinases, RTKs EGFR and EPHA2, and serine/threonine kinases KC1A, RIPK2, M3K2, and KS6A1 (RSK1). For BT474 cells, the 48 h MIB/MS signature defines a very different lapatinib response, with activation of INSR, PRPK (TP53-regulating kinase), ULK3 (autophagy, Hedgehog pathway), and KS6A4 (RSK4). Opposite from SKBR-3 cells, DDR1, FRK, NEK9, and cytoskeleton-regulating kinases (MARK3 and LIMK1) are inhibited (Figure 2A). Of activated kinases, only YES, KS6A5, PRKDC, and STK3 are common between SKBR-3 and BT474 cells.

Figure 2. MIB/MS and RNA sequencing define heterogeneity in the adaptive response.

(A) Statistically significant MIB-binding changes after 48 h lapatinib treatment based on Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-values at FDR of 0.05 and standard deviation in five ERBB2+ cell lines depicted graphically. Kinome trees reproduced courtesy of Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (www.cellsignal.com).

(B) Lapatinib-induced MIB-binding changes of tyrosine kinases illustrates differences between cell lines and identifies common response of INSR and IGF1R activation.

(C) Principal component analysis identifies kinases that drive the variation in kinome response. Kinases captured in at least 3 out of 4 MIB/MS runs per cell line (67 kinases) were used.

(D) Lapatinib induces 2-fold changes up or down in 18-20% of expressed mRNA transcripts.

(E) Gene ontology terms enriched in commonly upregulated mRNAs between SKBR-3 and BT474 cells ide ntifies glucose regulation and transcriptional regulation as most significant processes.

(F) Kinase mRNAs upregulated by lapatinib at least 2-fold by RNAseq in SKBR-3 and BT474. Hatched bars indicate RTKs and red bars indicate common upregulated kinases.

Also see Figures S2 and S3

MIB/MS was performed for three additional ERBB2-amplified cell lines after 48 h lapatinib treatment: luminal HCC1419 cells are highly sensitive to lapatinib-induced growth arrest, while basal-like HCC1954 and luminal MDA361 cells are more resistant. HCC1954 and MDA361 harbor activating PIK3CA mutations (H1047R and E545K, respectively) and display resistance to trastuzumab. The kinome of HCC1954 cells is very responsive with activation of multiple RTKs, PKC isoforms, and CAMKs. In contrast, the kinome of MDA361 cells is mostly suppressed by lapatinib with INSR and IGF1R the only RTKs with statistically significant increases in MIB binding (Figure 2A). HCC1419 cells are intermediate in their adaptive response, with four TKs significantly activated: DDR1, INSR, FAK1 and FRK. Across cell lines, multiple induced kinases are known to modulate or act downstream of ERBB signaling, including SFKs, FAK1, JAK1, CSK, CDK5, and PKCδ, emphasizing an addiction to ERBB-driven signaling networks (Allen-Petersen et al., 2014; Li et al., 2003). It was unexpected that the lapatinib adaptive response would demonstrate such heterogeneity across multiple kinase subfamilies in five ERBB2+ cell lines (Figure 2B, TKs; Figure S2A, other subfamilies). The responsiveness of the kinome does not seem to correlate with EGFR/ERBB2 expression or activation level or the dependency on different ERBB family members as measured by RNAi analysis (Figures S2B-C).

The RTK family displays significant variability in activity and response across the five cell lines, but IGF1R/INSR is commonly activated and EPHA2 commonly inhibited in all lines (Figure 2B). Among non-receptor TKs, multiple cell lines activate FRK, FAK1, and TYK2. SKBR-3 and HCC1954 share a robust activation of most TKs captured by MIBs. 3x3 self-organizing map (SOM) clustering identifies common kinase behavior between several lines, including induction of PRKDC, STK38, NEK9, FRK, STK3, and DDR1 (Figure S3A-B). A cluster preferentially induced in HCC1954 includes stress response kinases (MK09, MK11, MK14, STK24), CSK22 (CK2α), KCC2G (CAMK2G), KPCD2, and TKs ACK1 and PTK6 (Figure S3C). Commonly-inhibited kinases among the five cell lines include cell cycle-regulating kinases as well as KS6B1 (p70 S6 kinase) (Figure S3D). To understand the variation in kinome response between cell lines, we utilized principal component analysis (PCA) (Figure 2C). Principal component 1 (PC1) accounts for the majority of the variation and separates kinases that are commonly suppressed (STK6, PMYT1, CDK1, EPHA2, CDK4) from those that are primarily induced (PRKDC, INSR, DDR1) among cell lines. Kinases driving variation between cell lines in PC2 and PC3 agree with differences observed in 48 h MIB/MS signatures (Figure 2A) and SOM analysis (Figure S3A-D), and provide a statistical measure of the heterogeneity in the kinome response. These kinases include DDR1, FRK, KPCD, KT3K, CDK5, PTK6, PRPK and KS6A4.

mRNA sequencing (RNAseq) indicates 18-20% of the transcriptome is modulated at least 2-fold after 48h lapatinib treatment in SKBR-3 and BT474 cells (Figure 2D). Gene ontology terms enriched in commonly upregulated genes involve regulation of glucose homeostasis and transcription, consistent with a reactivation of AKT signaling networks and reorganization of a significant portion of the transcriptome (Figure 2E). Kinases commonly upregulated 2-fold or more between SKBR-3 and BT474 cells include RTKs INSR, ERBB3, and ERBB4, the cytoskeleton-regulating kinases TBCK, DCLK2, and TTBK2, and DYRK1B – a modulator of FOXO transcription (Figure 2F). ERBB2, PTK7 and DDR1 in SKBR-3 and EPHA7, MERTK, EPHA4, EGFR, IGF1R, and FGFR2 in BT474 are also upregulated, consistent with a transcriptional component of the adaptive RTK response. In BT474 cells, IRS2 and IGF1 (both 16-fold) are among the top 20 upregulated genes, indicating an autocrine/paracrine feedforward loop activating IGF1R signaling.

Significant heterogeneity exists among kinases that compensate for ERBB2 in the presence of lapatinib

Given the cluster of INSR/IGF1R activation, reports of IGF1R/ERBB2/ERBB3 complexes in trastuzumab-resistant cells (Huang et al., 2010), and the enrichment of glucose signaling networks from the RNAseq data, we investigated the role of IGF1R and INSR in bypassing ERBB2 inhibition. SKBR-3 and BT474 cells were treated with increasing doses of the INSR/IGF1R inhibitor BMS754807 (BMS754) in the presence or absence of lapatinib (Figure 3A). The combination of lapatinib + BMS754 causes a dose-dependent increase in AKT phosphorylation in SKBR-3 but a decrease in BT474 cells. Combinations of lapatinib and BMS754 have little effect on HCC1419 and HCC1954 signaling (Figure S3F), but in MDA361 cells BMS754 alone reduces phosphorylation of ERBB2, ERBB3, FAK, SFKs, and AKT S473, and in combination with lapatinib further inhibits AKT (Figure 3B). Crystal violet colony formation assays demonstrate the combination of lapatinib and BMS754 significantly inhibits growth of MDA361 cells, but resistant colonies persist, and no major enhancement of lapatinib-induced growth inhibition is observed in other cell lines (Figure 3C). Thus, co-targeting ERBB2 and the common IGF1R/INSR response does not provide a successful pan combination therapy.

Figure 3. Cell lines exhibit variability in kinases that drive growth in the presence and absence of lapatinib.

(A) Lapatinib combined with increasing doses of BMS754807 (IGF1R/INSR inhibitor) causes an increase in AKT phosphorylation in SKBR-3 but a decrease in BT474 relative to lapatinib treatment alone after 24 h.

(B) BMS754 inhibits ERBB2/3 phosphorylation as a single agent, and when combined with lapatinib causes a further inhibition of AKT phosphorylation after 24 h.

(C) Colony formation assays indicate heterogeneity in the kinases that contribute to growth. IGF1R/INSR inhibition has an additive effect with lapatinib in MDA361. Dasatinib is additive in BT474 and MDA361 but does not significantly enhance growth inhibition of other lines. SKBR-3 cells display synergism between lapatinib and PF228 (FAK inhibitor) or BGJ398 (FGFR inhibitor) but other cell lines show varying degrees of growth-inhibition by FAK or FGFR inhibition alone and in combination with lapatinib. SKBR-3, BT474, and HCC1419 treated for 4 weeks, HCC1954 and MDA361 treated for 5 weeks. Lapatinib doses: 100nM SKBR3; 30nM BT474; 10nM HCC1419; 300nM HCC1954 and MDA361. Data presented is mean ± SD of three technical replicates. * indicates significant difference from lapatinib alone (p≤0.05).

(D) MIB/MS profile of SKBR-3 and BT474 cells after 48h treatment with 300nM Lapatinib, 30nM Dasatinib, or the combination. Dasatinib inhibits MIB-binding of multiple tyrosine kinases, but not FAK1 and FAK2 in SKBR-3 cells.

(E) Western blots after 48 h demonstrate Dasatinib inhibits Lapatinib-induced SFK phosphorylation but increases FAK phosphorylation.

(F) Western blots after 48 h indicate PF228 inhibits FAK and SFK phosphorylation, but increases AKT and ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

(G) Western blots indicate FGFR inhibition alone slightly reduces AKT and ERK phosphorylation at 4 h, but elicits strong reactivation by 48 h. Combination with lapatinib indicates FGFRs regulate ERBB signaling and SFK and FAK phosphorylation. 300nM Lapatinib and 300nM BGJ398 added directly to media at 0 h. Media was not changed throughout experiment.

(H) MIB/MS analysis of 300nM lapatinib, 300nM BGJ398, or the combination after 48 h indicates FGFRs regulate multiple lapatinib-induced TKs.

(I) Matrix of p-values comparing growth inhibition of lapatinib alone versus lapatinib + kinase inhibitor in colony formation assays. Red, significant (p≤0.05); blue, not significant (p≥0.05).

Lapatinib induces activity and transcription of DDR1, SFKs, and EPH receptors in multiple cell lines (Figures 2A, 2B, 2F), all of which are targets for dasatinib, and previous reports link SFKs to escape from ERBB2-targeted therapies (Rexer et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). Treatment of SKBR-3 and BT474 cells with dasatinib causes a loss of MIB binding of multiple RTKs and TKs and prevents lapatinib-induced MIB-binding (Figure 3D). Colony formation assays demonstrate dasatinib only modestly enhances lapatinib growth-inhibition in BT474 and MDA361 cells (Figure 3C). Western blots indicate the combination of lapatinib and dasatinib inhibits activation of SFKs, AKT, and ERK1/2, but actually increases FAK phosphorylation (Figure 3E). Lapatinib induces FAK MIB-binding in multiple cell lines (Figure 2A), and the FAK inhibitor PF573228 in combination with lapatinib synergize in colony formation assays in SKBR-3 cells (Figure 3C). PF573228 inhibits FAK and SFK phosphorylation in the presence or absence of lapatinib (Figure 3F), suggesting both pathways must be inhibited in the presence of lapatinib to generate stable growth inhibition. While other cell lines do not demonstrate such strong synergism seen with SKBR-3 cells, FAK signaling is crucial for the growth of several cell lines and FAK inhibition enhances lapatinib growth inhibition.

FGFR2 is induced by lapatinib by MIB/MS (SKBR-3, Figure 2A) and RNAseq (BT474, Figure 2F), and FGFR2 has been implicated in compensating for ERBB2 in the presence of lapatinib (Azuma et al., 2011), so we tested lapatinib + a pan-FGFR inhibitor (BGJ398). Colony formation assays demonstrate FGFR inhibition enhances lapatinib growth-inhibition and SKBR-3 cells display moderate synergism between lapatinib and BGJ398 (Figure 3C). Most lines are growth-inhibited by BGJ398 in the absence of lapatinib, suggesting FGFRs cooperate with ERBB2 for growth of ERBB2+ cells. Combining lapatinib and BGJ398 inhibits ERBB2/ERBB3 reactivation and further inhibits SFK and FAK phosphorylation in SKBR-3 cells, but in turn elicits a stronger AKT/ERK response than lapatinib alone (Figure 3G). MIB/MS analysis of SKBR-3 cells demonstrates BGJ398 inhibits lapatinib induction of SFKs, FAK1/2, and multiple other TKs consistent with FGFR participation in lapatinib-induced kinome adaptation (Figure 3H). The combination of lapatinib and BGJ398 still allows resistant colony formation in all five cell lines, suggesting alternative growth-promoting signaling networks are activated even in response to combined ERBB/FGFR/SFK/FAK inhibition. Overall, these results identify multiple kinases that contribute to ERBB2+ cell growth, and reveal heterogeneity in the kinases that compensate for lapatinib-mediated ERBB2 inhibition.

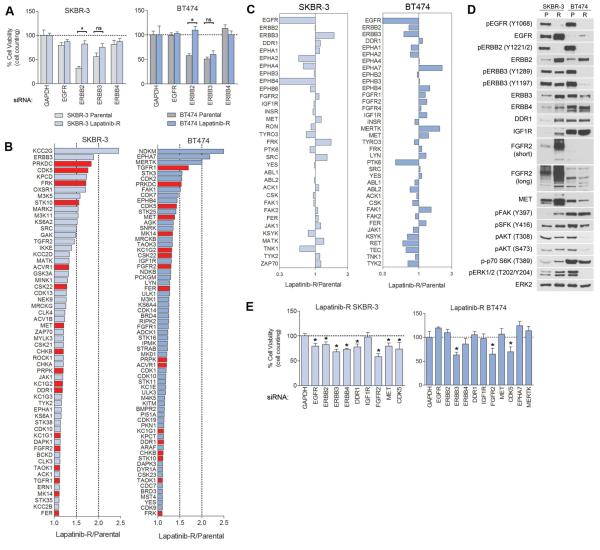

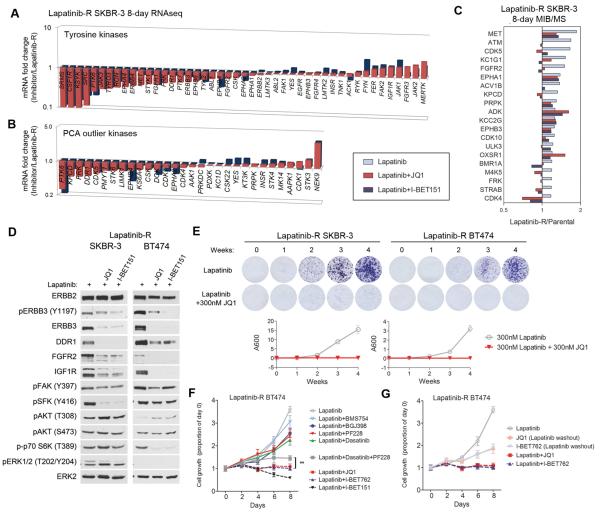

Lapatinib-resistant SKBR-3 and BT474 depend on multiple kinases for growth

To further define how the kinome bypasses inhibition of ERBB2, we generated lapatinib-resistant (LapR) SKBR-3 by continuous treatment with 300nM lapatinib for 4+ months and LapR BT474 by progressively increasing doses of lapatinib every 3-4 weeks to 300nM. Resistant lines were kept as a pool of all clones that grew out. LapR SKBR-3 grow at a similar rate to parental cells while LapR BT474 grow somewhat slower than parental (Figures S4A-B). LapR cells are less sensitive to growth inhibition by ERBB2 knockdown but similarly sensitive to ERBB3 knockdown as compared to parental cells (Figure 4A). MIB/MS was used to compare LapR cells to lapatinib-sensitive parental cells (Figure S4C). Longtail plots of activated kinases show the most-activated kinases in LapR cells overlap with 48 h MIB/MS signatures and transcriptome responses of the parental line and other ERBB2+ lines (Figures 4B, 2A, 2F). LapR SKBR-3 and BT474 cells share several activated kinases, including PRKDC, CDK5, TGFR1, ACVR1, CK1/2 and TKs MET, DDR1, FGFR2, FRK, and FER. Among RTKs, LapR SKBR-3 display strong activation of ERBB3 and modest increases in DDR1, FGFR2 and MET, while LapR BT474 activate multiple FGFRs, EPHA7, MERTK, MET, and IGF1R (Figure 4C). Western blots indicate inhibition of EGFR/ERBB2 phosphorylation in LapR cells with upregulation of multiple RTKs and reactivation of AKT/ERK in SKBR-3 cells but reduced activity of AKT/ERK in BT474 relative to parental cells (Figure 4D). Knockdown of ERBB RTKs, FGFR2, DDR1, MET, and CDK5 all provided partial growth inhibition of LapR SKBR-3 cells, while LapR BT474 cells are growth-inhibited by ERBB3, FGFR2, and CDK5 knockdown (Figures 4E, S4D-F). Thus, prolonged exposure to lapatinib causes a broad reorganization of the kinome and shifts dependency away from ERBB2 and toward multiple other kinases including several RTKs.

Figure 4. Multiple unrelated kinases contribute to the growth of lapatinib-resistant cells.

(A) Parental or 300nM lapatinib-resistant (LapR) SKBR-3 and BT474 cells were transfected with siRNAs against GAPDH (control) or ERBB receptors and cultured for 96 h. Both parental lines are strongly growth-inhibited by ERBB2 and ERBB3 knockdown. LapR cells are less dependent on ERBB2 but remain similarly dependent on ERBB3.

(B) MIB/MS long tail plots of most-activated kinases in LapR SKBR-3 and BT474 cells, relative to parental cells. Kinases in red are commonly over-activated in SKBR-3 and BT474.

(C) MIB/MS profile of tyrosine kinases from LapR SKBR-3 and BT474 cells. LapR SKBR-3 cells display enhanced MIB-binding of ERBB3, DDR1, FGFR2, MET, FRK, and SRC. LapR BT474 have increased activity of multiple FGFRs, EPHA7, IGF1R, MERTK, MET, LYN, and FAK1. Data presented is mean of two biological replicate MIB/MS experiments.

(D) Western blots indicate RTK upregulation in LapR SKBR-3 cells and reactivation of AKT/ERK signaling. LapR BT474 cells display suppressed activity of AKT and ERK relative to parental cells. P, parental; R, LapR.

(E) 96 h siRNA knockdown in LapR SKBR-3 cells indicates slight dependency on ERBB family, and a stronger dependency on DDR1, FGFR2, and CDK5. BT474 cells are growth-inhibited by ERBB3, FGFR2, and CDK5 knockdown. Data presented in A and E is mean ± SD of six technical replicates.

Also see Figure S4

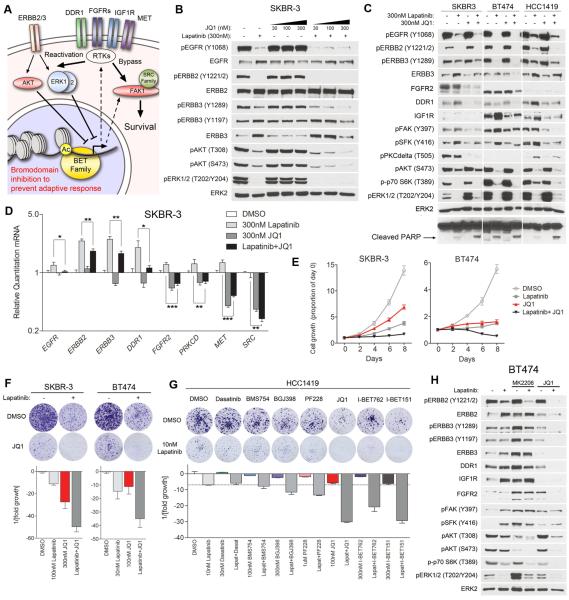

BET family bromodomain inhibition suppresses lapatinib-induced kinome reprogramming

By undertaking this comprehensive analysis, we unveiled significant heterogeneity in lapatinib-induced kinome adaptation in ERBB2+ cells and demonstrated the resiliency of the kinome to bypass combinations of lapatinib and a second kinase inhibitor. This argues multiple sequential combinations of kinase inhibitors and possibly intermittent therapies might be necessary to prevent resistance, but rationally choosing such a regimen poses a significant challenge. Multiple kinases contribute to growth, and since there is no one drug that can inhibit the activity of all responsive kinases, we hypothesized that targeting the adaptive response itself would make lapatinib-induced growth arrest more durable (Figure 5A). RNAseq analysis indicates 8-10% of the expressed transcriptome is upregulated ≥2-fold within 48 h of lapatinib treatment (Figure 2D). Of significance, kinases involved in resistance are transcriptionally induced by lapatinib treatment (e.g., ERBB3, DDR1, FGFR2), as are many kinases in the 48 h MIB/MS signature of SKBR-3 cells (Figure S5A). This is consistent with lapatinib inhibiting AKT and ERK signaling networks causing FOXO activation and c-Myc degradation, leading to RTK upregulation (Chandarlapaty et al., 2011; Duncan et al., 2012). Thus, we decided to target epigenetic factors – proteins that modify or associate with chromatin – to prevent the reprogramming response at a transcriptional level. We tested inhibitors of different epigenetic enzymes and identified JQ1, an inhibitor of BET family bromodomains (Delmore et al., 2011) as capable of suppressing lapatinib-induced kinome reprogramming.

Figure 5. BET bromodomain inhibition suppresses lapatinib-induced kinome reprogramming and arrests growth.

(A) Kinome reprogramming leads to transcriptional upregulation of multiple alternative kinases capable of reactivating or bypassing ERBB2-directed signaling. We hypothesize by inhibiting the BET family of bromodomain-containing acetylation readers, we can prevent the adaptive response at an epigenetic level.

(B) Western blots demonstrate JQ1 (BET family bromodomain inhibitor) suppresses lapatinib-induced ERBB3 phosphorylation and expression at 300nM, and inhibits reactivation of AKT in SKBR-3 cells. 48h treatments.

(C) Western blots indicate JQ1 blocks protein expression of multiple kinases involved in lapatinib resistance, and leads to a decrease in ERBB family, SFK, FAK, and PKCδ phosphorylation. JQ1/lapatinib combinations inhibit AKT and p70 S6K phosphorylation more than Lapatinib alone and increase cleavage of PARP. 48h treatments.

(D) qRT-PCR after 24h treatment shows JQ1 inhibits mRNA transcription of multiple RTKs involved in resistance (ERBB3, DDR1, FGFR2, MET) and suppresses lapatinib-mediated induction.

(E) 8-day growth curves demonstrate JQ1/lapatinib combination prevents growth of SKBR-3 and BT474 cells. Data presented is mean ± SD of six technical replicates.

(F) JQ1 in combination with lapatinib suppresses colony formation of SKBR-3 and BT474 cells after 4-weeks.

(G) BET family bromodomain inhibitors (JQ1, I-BET762, I-BET151) suppress colony formation of HCC1419 cells more so than kinase inhibitors in combination with lapatinib in 4-week colony formation assays.

(H) Western blots indicate AKT inhibition (MK2206) induces RTK expression and ERK signaling alone and in combination with lapatinib. BET bromodomain inhibition alone does not sustain inhibition of signature kinases, and only in combination with lapatinib suppresses the adaptive response. 8-day treatment with 30nM lapatinib, 100nM MK2206, and 300nM JQ1.

Data presented in D, F, and G is mean ± SD of three technical replicates. Also see Figures S5 and S6

ERBB2+ cell lines are sensitive to growth inhibition by JQ1 and I-BET762, a second BET bromodomain inhibitor (Figure S5B). Treatment of SKBR-3 cells with JQ1 prevents lapatinib-induced phosphorylation and expression of ERBB3, a primary mediator of the adaptive response leading to AKT reactivation and lapatinib resistance (Figure 5B). JQ1 also suppresses lapatinib-induced expression of FGFR2, DDR1, IGF1R, pFAK, pSFK and pPKCδ across multiple cell lines (Figure 5C). JQ1 alone has little effect on AKT and p70 S6K phosphorylation, but in combination inhibits the activity of both kinases more than that seen with lapatinib alone. Increased PARP cleavage is observed with the combination of lapatinib and JQ1 versus single agents, indicating an increase in apoptosis (Figure 5C). JQ1 also inhibits lapatinib-mediated kinase induction in HCC1954 and MDA361 cells, including growth-promoting kinases FGFR1, FGFR2, and IGF1R (Figure S5C). Treatment of SKBR-3 cells with another BET inhibitor, I-BET151, similarly blocks lapatinib-induced expression and phosphorylation of signature kinases (Figure S5D). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis demonstrates JQ1 suppresses or prevents lapatinib-induced transcription of many adaptive response kinases implicated in resistance, including ERBB3, DDR1, FGFR2, IGF1R, and MET, in addition to ERBB2 itself (Figures 5D and S5E).

JQ1 alone only reduces the growth of SKBR-3 and BT474 cells and results in the formation of resistant colonies in four-week clonogenic assays, but when combined with lapatinib strongly arrests growth or results in regression of cell number and essentially eliminates colony formation (Figures 5E, 5F). I-BET762 and I-BET151 elicit similar growth-inhibitory responses from SKBR-3 and BT474 cells (Figures S6A-C). Clonogenic assays with HCC1419 cells demonstrate combinations of lapatinib and BET bromodomain inhibitors suppress ERBB2+ cell growth more effectively than kinase inhibitor combinations with lapatinib (dasatinib, BMS754, PF228, and BGJ398) (Figure 5G). Growth of HCC1954 and MDA361 cells, which are more resistant to lapatinib than SKBR-3 or BT474 cells, is also inhibited by lapatinib + BET bromodomain inhibitors in 8-day and 5-week growth assays (Figures S6D-F).

Since AKT is a convergent node downstream of many RTKs and crucial to ERBB2+ cell growth, we compared BET bromodomain inhibitors to AKT inhibitors in combination with lapatinib. In 8-day treatments of BT474 cells, the AKT inhibitor MK2206 alone or in combination with lapatinib induces multiple RTKs (ERBB3, DDR1, IGF1R, FGFR2) and results in increased FAK, SFK, and ERK phosphorylation (Figure 5H). Importantly, JQ1 or I-BET151 alone is unable to completely suppress signature kinase expression and signaling, and only when combined with lapatinib inhibits RTK expression and activity and causes a loss of downstream FAK, SFK, AKT, ERK, and p70 S6K signaling (Figures 5H, S6G). This strongly suggests JQ1 inhibits reactivation of oncogenic signaling by suppressing the adaptive kinome response. 4-week growth assays indicate that while AKT inhibitors (MK2206 and GSK690693) work well in combination with lapatinib in BT474 cells, resistant colonies still form in SKBR-3 and HCC1419 cells (Figure S6H). This contrasts with the lack of colony formation in lapatinib + JQ1 combinations across all lines. These findings further support disruption of AKT/ERK signaling networks leading to RTK upregulation and a sustained blockade of the adaptive response by BET bromodomain inhibition.

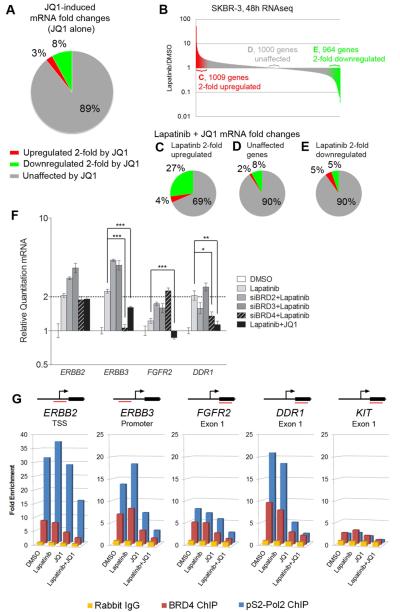

JQ1 regulates lapatinib-induced transcription and releases BRD4 and pSer2-Polymerase II from adaptive kinase genes

RNAseq analysis demonstrates JQ1 downregulates 8% and 11% of genes at least 2-fold in SKBR-3 and BT474 cells, respectively (Figures 6A and S7A). A smaller percentage is upregulated 2-fold, with 3% in SKBR-3 and 5% in BT474, indicating JQ1 affects transcription overall less than lapatinib. In combining lapatinib and JQ1, we found that genes upregulated by lapatinib were suppressed by JQ1 more than those unaffected or downregulated by lapatinib (Figures 6B-E, S7B-E). Of transcripts induced at least 2-fold by lapatinib in SKBR-3 cells, adding JQ1 suppressed the induction of 27% by at least half, and further upregulated just 4% (Figure 6C). Similarly, in BT474 cells JQ1 suppresses 28% of lapatinib-induced genes (Figure S7C). This indicates that JQ1 preferentially modulates lapatinib-responsive gene expression. Reports indicate suppression of MYC transcription is central to JQ1 function. BT474 cells stably overexpressing c-Myc are less sensitive to JQ1, but the combination of lapatinib+JQ1 still causes growth arrest in SKBR-3 and cell regression in BT474 despite the rescue of c-Myc levels (Figures S7F-G).

Figure 6. JQ1 modulates lapatinib-induced transcription and inhibits epigenetic regulation of signature kinase genes.

(A) RNAseq indicates JQ1 affects 11% of expressed genes 2-fold or more in SKBR-3 cells after 48 h treatment.

(B) Figures 6C-E refer to JQ1 effect on lapatinib-regulated genes as indicated.

(C) JQ1 downregulates 27% of the 1009 lapatinib-induced genes by at least 2-fold from the lapatinib-induced mRNA level.

(D) 1000 genes not affected by lapatinib treatment display a similar up- or down-regulation profile in the lapatinib+JQ1 combination compared to JQ1 alone.

(E) 964 genes at least 2-fold downregulated by lapatinib are mostly unaffected by JQ1 as compared to JQ1 alone or JQ1 effects on lapatinib-upregulated genes.

(F) qRT-PCR demonstrates siRNA-mediated knockdown of BRD2 and BRD3 enhances transcription of ERBB2, ERBB3, FGFR2 and DDR1. Knockdown of BRD4 suppresses ERBB3 and DDR1 transcription, similar to JQ1. 24h siRNA knockdown, then 24h drug treatment; 300nM JQ1, 300nM lapatinib. Data presented is mean ± SD of three technical replicates.

(G) ChIP-PCR indicates JQ1 inhibits BRD4 promoter occupation in the absence of lapatinib. Loss of BRD4 and elongating RNA Polymerase II (pS2-Pol2) from upstream elements is maximal when JQ1 is combined with lapatinib. 4h treatments with 300nM lapatinib and 300nM JQ1 in SKBR-3 cells. Data presented is mean of three biological replicate experiments.

Also see Figure S7

Figure 7. BET bromodomain inhibition suppresses signature kinases and arrests growth in lapatinib-resistant cells.

(A) RNAseq after 8-day treatment of lapatinib-resistant (LapR) SKBR-3 cells with lapatinib + 300nM JQ1 or 1µM I-BET151 indicates transcriptional suppression of the majority of tyrosine kinases.

(B) mRNA fold changes in outlier kinases identified by PCA (Figure 2C) indicates BET inhibitors suppress the majority of kinases that drive variation in the kinome response.

(C) MIB/MS analysis of the top 20 most-activated kinases in LapR SKBR-3 cells following 8 days treatment with 300nM JQ1 or 1µM I-BET151 indicates the majority of kinase activity is inhibited or blocked.

(D) Western blots of LapR SKBR-3 and BT474 cells treated with 300nM JQ1 or 1µM I-BET151 in combination with 300nM lapatinib show suppression of signature kinase expression and phosphorylation.

(E) 4-week colony formation assays demonstrate JQ1 suppresses colony formation and arrests growth of LapR SKBR-3 and BT474 cells in the presence of lapatinib. Data presented is mean ± SD of three technical replicates.

(F) LapR BT474 cells are moderately growth-inhibited by combinations of lapatinib and other kinase inhibitors, but growth is completely suppressed by lapatinib and bromodomain inhibitors (300nM JQ1, 1µM I-BET762, or 1µM I-BET151, even more effectively than a triple kinase inhibitor combination (lapatinib+dasatinib+PF228).

(G) Growth of LapR BT474 cells is arrested with 300nM JQ1 or 1µM I-BET762, but only in the presence of lapatinib.

Data presented in F and G is mean of six technical replicates ± SD.

RNAi was used to inhibit the expression of BET family members BRD2, 3 or 4 in SKBR-3 and BT474 cells (Figures 6F, S7H-I). BRD2 and BRD3 knockdown actually increases target kinase transcription in response to lapatinib. In contrast, lapatinib in combination with BRD4 knockdown was similar to JQ1 in reducing lapatinib-mediated induction of ERBB3 and DDR1 expression. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR demonstrates JQ1 displaces BRD4 from the promoters and upstream elements of lapatinib-induced kinase genes ERBB2, ERBB3, FGFR2, and DDR1 (Figures 6G, S7J). KIT is not expressed in SKBR-3 cells and serves as a negative control for ChIP-PCR analysis. JQ1 treatment also reduces the level of the elongating form of RNA Polymerase II (phospho-Serine 2 of the C-terminal tail repeat; pS2-Pol2) binding to promoters and internal exons of target kinase genes, consistent with transcriptional inhibition (Figures 6G, S7J). Importantly, BRD4 and pS2-Pol2 are most effectively dissociated from chromatin by combined lapatinib + JQ1 treatment, indicating synergism between these drugs at an epigenetic level.

BET bromodomain inhibition re-sensitizes resistant cells to lapatinib

RNAseq of LapR SKBR-3 cells following 8-day treatment with combinations of lapatinib with JQ1 or I-BET151 indicates transcriptional suppression of a large proportion of TKs, including those that contribute to growth (ERBB3, DDR1, FGFR2, and MET, Figure 7A). Many outlier kinases from PCA (a representation of heterogeneity in the kinome response, Figure 2C) are also suppressed by BET bromodomain inhibition (Figure 7B). MIB/MS analysis from the same treatments indicates JQ1 and I-BET151 inhibit or block the activity of the most-induced kinases in LapR SKBR-3 cells relative to parental cells (Figure 7C). Accordingly, JQ1 and I-BET151 inhibit the protein expression and phosphorylation of signature kinases in LapR SKBR-3 and BT474 cells, effectively reversing the adaptive kinome reprogramming response (Figure 7D). Four-week clonogenic growth assays demonstrate that the combination of lapatinib and JQ1 arrests the growth of lapatinib-resistant cells (Figure 7E). Furthermore, combinations of lapatinib and BET bromodomain inhibitors are superior to combinations of lapatinib and kinase inhibitors that only slow the growth of LapR cells (Figure 7F). Lapatinib + BET bromodomain inhibitor combinations are even significantly more effective than the triple combination of lapatinib, dasatinib and FAK inhibitor. This indicates that arresting the transcriptional reprogramming response is more effective than inhibiting the activity of multiple induced kinases. While BET inhibitors arrest the growth of LapR cells in combination with lapatinib, removal of lapatinib from the media while maintaining JQ1 or I-BET762 in the culture allows the cells to begin growing again (Figure 7G). Thus, lapatinib and BET bromodomain inhibitor must be present in combination to effectively inhibit growth; JQ1 or I-BET alone is not sufficient to inhibit growth of the cells. Since LapR BT474 cells do not depend on EGFR or ERBB2 for growth in the presence of lapatinib (Figure 4A), this indicates BET bromodomain inhibitors sensitize cells to lapatinib by blocking alternative kinases involved in adaptive growth responses.

DISCUSSION

In this study we used MIB/MS to define lapatinib-induced kinase activation dynamics on a kinome-wide level. This global approach unveiled a robust network of kinases that compensate for ERBB2 inhibition induced within 48 h of lapatinib treatment, indicating multiple potential mechanisms of resistance emerge rapidly upon kinase inhibitor treatment. Inhibition of different induced kinases in combination with lapatinib increased growth inhibition across the five ERBB2+ cell lines to varying degrees. Strong growth inhibition was observed by targeting FAK in combination with lapatinib in SKBR-3 cells, indicating significant synergism can be achieved if such vulnerable nodes are defined. Heterogeneity in the adaptive kinome response, however, makes identifying effective combination inhibitor treatments a challenging task. Adding to the problem is the differential dependence of tumor cells on unrelated kinases in addition to ERBB2. Together, these findings present a dilemma where combinations of any two or even three kinase inhibitors would be insufficient to suppress the resiliency of the kinome and sustain inhibition of tumor cell growth.

The five cell lines used in our study are each ERBB2+ but HCC1954 and MDA361 are less sensitive to lapatinib than the other three lines. MDA361 cells respond to inhibitors of IGF1R/INSR, SFKs, FAK, and FGFRs in the absence of ERBB2 inhibition, suggesting intrinsic resistance to ERBB2-targeted therapies can be rooted in dependence on multiple alternative kinases. Successful treatment of such tumors would be difficult with combinations of kinase inhibitors. Heterogeneity of kinase expression in different regions of the tumor would further enhance this dilemma. Our study demonstrates BET bromodomain inhibition provides an epigenetic mechanism to target a series of kinases that mediate resistance and sustain ERBB2+ cell growth. Indeed, MDA361 cells are the most sensitive to the JQ1/lapatinib combination treatment even though they are relatively insensitive to lapatinib alone.

We acknowledge inhibition of major epigenetic regulators such as BET bromodomain proteins has effects beyond the blockade of adaptive kinome reprogramming. Histone deacetylase inhibitors such as panobinostat are in clinical use and have been shown in melanoma to suppress resistance mechanisms to BRAF inhibition (Johannessen et al. 2013). We found panobinostat similarly blocks adaptive reprogramming in ERBB2+ breast cancer cells, but it also displays significant cellular toxicity in the absence of lapatinib. In contrast, we identified a significant molecular synergism between BET bromodomain inhibitors and lapatinib that inhibited RNA polymerase II function, kinase expression and phosphorylation. The ChIP-PCR data with SKBR-3 and long-term signaling studies with BT474 indicate the combination of lapatinib and BET bromodomain inhibitors is required to substantially suppress transcription of RTKs and prevent reactivation of AKT/p70 S6K signaling. These effects are not observed by JQ1 or I-BET151 treatment alone and suggest BET bromodomain inhibitors target the epigenetic machinery involved in the adaptive reprogramming response to lapatinib. RNAseq indicates approximately 2000 expressed genes are up or down regulated two-fold or greater by lapatinib. This adaptive transcriptome response involves a global reorganization of signaling that is borne out by significant changes in kinome activation dynamics. This argues that targeting broad-acting epigenetic regulators of transcription like BET bromodomain proteins is not only advantageous but needed to suppress this dramatic induction of gene expression. JQ1 suppresses 27% of lapatinib-induced transcripts by at least half, in contrast to 8% of genes as a whole. JQ1 thus has a selective inhibition of lapatinib-induced transcripts. SiRNA experiments identified BRD4 as participating in the reprogramming response. BRD4 is a core component of the P-TEFb transcriptional elongation complex (Jang et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2005), and regulates the phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II for activation of transcriptional elongation of newly induced genes (Devaiah et al., 2012). Disruption of this complex by targeting BRD4 function provides an elegant mechanism of how BET bromodomain inhibition might regulate kinome reprogramming.

By targeting chromatin readers we suppress expression of the majority of kinases having a potential role in lapatinib resistance, and provide a method to address both the heterogeneity in kinome response and inhibit a broad panel of kinases known to drive ERBB2+ cancer cell growth. Recent studies have described similar RTK networks comprised of ERBB receptors, MET, IGF1R, and FGFRs that become upregulated after targeted RTK inhibition (Singleton et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). It is conceivable that BET bromodomain inhibition would suppress these kinases in other cancers as well and provide a means to block the adaptive response to EGFR and FGFR inhibition observed in these studies. We believe epigenetic enzyme-targeting drugs will be key to preventing resistance rooted in kinome reprogramming, thus making the action of kinase inhibitors durable. With at least four BET bromodomain inhibitors in clinical trials, testing of a BET bromodomain inhibitor to block adaptive responses induced with kinase inhibitors is a possibility.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

MIB Chromatography and LC/MS

MIB preparation and chromatography was performed as previously described (Duncan et al., 2012). For multiplexing, peptides were labeled with iTRAQ and separated on a 288 or 300 min 5-45% ACN gradient as a single fraction. ABSciex 5800 MALDI TOF/TOF and Thermo Q-Exactive ESI mass spectrometers were used. For details, see supplemental experimental procedures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funded by the Susan G. Komen foundation IIR12-225201 (GLJ, LAC, HSE), NIH grant GM101141 (GLJ) U01 MH104999 (GLJ), T32 CA009156 (TJS) and the University Cancer Research Fund. GLJ, JJ, and LMG are co-founders of KinoDyn Inc., and HSE is co-founder of Meryx.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

For cell assays, statistics, western blotting, qRT-PCR, RNAseq, and ChIP-PCR, see supplemental experimental procedures.

REFERENCES

- Allen-Petersen BL, Carter CJ, Ohm AM, Reyland ME. Protein kinase Cdelta is required for ErbB2-driven mammary gland tumorigenesis and negatively correlates with prognosis in human breast cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:1306–1315. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin DN, Sergina N, Ahuja D, McMahon M, Blair JA, Wang D, Hann B, Koch KM, Shokat KM, Moasser MM. Resiliency and vulnerability in the HER2-HER3 tumorigenic driver. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000389. 16ra17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azuma K, Tsurutani J, Sakai K, Kaneda H, Fujisaka Y, Takeda M, Watatani M, Arao T, Satoh T, Okamoto I, et al. Switching addictions between HER2 and FGFR2 in HER2-positive breast tumor cells: FGFR2 as a potential target for salvage after lapatinib failure. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;407:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandarlapaty S, Sawai A, Scaltriti M, Rodrik-Outmezguine V, Grbovic-Huezo O, Serra V, Majumder PK, Baselga J, Rosen N. AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmore JE, Issa GC, Lemieux ME, Rahl PB, Shi J, Jacobs HM, Kastritis E, Gilpatrick T, Paranal RM, Qi J, et al. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146:904–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaiah BN, Lewis BA, Cherman N, Hewitt MC, Albrecht BK, Robey PG, Ozato K, Sims RJ, 3rd, Singer DS. BRD4 is an atypical kinase that phosphorylates serine2 of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:6927–6932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120422109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JS, Whittle MC, Nakamura K, Abell AN, Midland AA, Zawistowski JS, Johnson NL, Granger DA, Jordan NV, Darr DB, et al. Dynamic reprogramming of the kinome in response to targeted MEK inhibition in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell. 2012;149:307–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett JT, Olivares MG, Rinehart C, Granja-Ingram ND, Sanchez V, Chakrabarty A, Dave B, Cook RS, Pao W, McKinely E, et al. Transcriptional and posttranslational up-regulation of HER3 (ErbB3) compensates for inhibition of the HER2 tyrosine kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:5021–5026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016140108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Park CC, Hilsenbeck SG, Ward R, Rimawi MF, Wang YC, Shou J, Bissell MJ, Osborne CK, Schiff R. beta1 integrin mediates an alternative survival pathway in breast cancer cells resistant to lapatinib. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R84. doi: 10.1186/bcr2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Gao L, Wang S, McManaman JL, Thor AD, Yang X, Esteva FJ, Liu B. Heterotrimerization of the growth factor receptors erbB2, erbB3, and insulin-like growth factor-i receptor in breast cancer cells resistant to herceptin. Cancer research. 2010;70:1204–1214. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang MK, Mochizuki K, Zhou M, Jeong HS, Brady JN, Ozato K. The bromodomain protein Brd4 is a positive regulatory component of P-TEFb and stimulates RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription. Molecular cell. 2005;19:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen CM, Johnson LA, Piccioni F, Townes A, Frederick DT, Donahue MK, Narayan R, Flaherty KT, Wargo JA, Root DE, et al. A melanocyte lineage program confers resistance to MAP kinase pathway inhibition. Nature. 2013;504:138–142. doi: 10.1038/nature12688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li BS, Ma W, Jaffe H, Zheng Y, Takahashi S, Zhang L, Kulkarni AB, Pant HC. Cyclin-dependent kinase-5 is involved in neuregulin-dependent activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt activity mediating neuronal survival. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35702–35709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexer BN, Arteaga CL. Intrinsic and acquired resistance to HER2-targeted therapies in HER2 gene-amplified breast cancer: mechanisms and clinical implications. Crit Rev Oncog. 2012;17:1–16. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v17.i1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexer BN, Ham AJ, Rinehart C, Hill S, Granja-Ingram Nde M, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Mills GB, Dave B, Chang JC, Liebler DC, Arteaga CL. Phosphoproteomic mass spectrometry profiling links Src family kinases to escape from HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibition. Oncogene. 2011;30:4163–4174. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik-Outmezguine VS, Chandarlapaty S, Pagano NC, Poulikakos PI, Scaltriti M, Moskatel E, Baselga J, Guichard S, Rosen N. mTOR kinase inhibition causes feedback-dependent biphasic regulation of AKT signaling. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:248–259. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra V, Scaltriti M, Prudkin L, Eichhorn PJ, Ibrahim YH, Chandarlapaty S, Markman B, Rodriguez O, Guzman M, Rodriguez S, et al. PI3K inhibition results in enhanced HER signaling and acquired ERK dependency in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Oncogene. 2011;30:2547–2557. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton KR, Kim J, Hinz TK, Marek LA, Casas-Selves M, Hatheway C, Tan AC, DeGregori J, Heasley LE. A receptor tyrosine kinase network composed of fibroblast growth factor receptors, epidermal growth factor receptor, v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 2, and hepatocyte growth factor receptor drives growth and survival of head and neck squamous carcinoma cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:882–893. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.084111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Wang L, Huang S, Heynen GJ, Prahallad A, Robert C, Haanen J, Blank C, Wesseling J, Willems SM, et al. Reversible and adaptive resistance to BRAF(V600E) inhibition in melanoma. Nature. 2014;508:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Yik JH, Chen R, He N, Jang MK, Ozato K, Zhou Q. Recruitment of P-TEFb for stimulation of transcriptional elongation by the bromodomain protein Brd4. Molecular cell. 2005;19:535–545. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Huang WC, Li P, Guo H, Poh SB, Brady SW, Xiong Y, Tseng LM, Li SH, Ding Z, et al. Combating trastuzumab resistance by targeting SRC, a common node downstream of multiple resistance pathways. Nat Med. 2011;17:461–469. doi: 10.1038/nm.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Wang J, Ji D, Wang C, Liu R, Wu Z, Liu L, Zhu D, Chang J, Geng R, et al. Functional Genetic Approach Identifies MET, HER3, IGF1R, INSR Pathways as Determinants of Lapatinib Unresponsiveness in HER2-Positive Gastric Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4559–4573. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.