Abstract

Background and Aims:

Intraperitoneal instillation of local anaesthetics has been shown to minimise post-operative pain after laparoscopic surgeries. We compared the antinociceptive effects of intraperitoneal dexmedetomidine or tramadol combined with bupivacaine to intraperitoneal bupivacaine alone in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Methods:

A total of 120 patients were included in this prospective, double-blind, randomised study. Patients were randomly divided into three equal sized (n = 40) study groups. Patients received intraperitoneal bupivacaine 50 ml 0.25% +5 ml normal saline (NS) in Group B, bupivacaine 50 ml 0.25% + tramadol 1 mg/kg (diluted in 5 ml NS) in Group BT and bupivacaine 50 ml 0.25% + dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg, (diluted in 5 ml NS) in Group BD before removal of trocar at the end of surgery. The quality of analgesia was assessed by visual analogue scale score (VAS). Time to the first request of analgesia, total dose of analgesic in the first 24 h and adverse effects were noted. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft (MS) Office Excel Software with the Student's t-test and Chi-square test (level of significance P = 0.05).

Results:

VAS at different time intervals, overall VAS in 24 h was significantly lower (1.80 ± 0.36, 3.01 ± 0.48, 4.5 ± 0.92), time to first request of analgesia (min) was longest (128 ± 20, 118 ± 22, 55 ± 18) and total analgesic consumption (mg) was lowest (45 ± 15, 85 ± 35, 175 ± 75) in Group BD than Group BT and Group B.

Conclusion:

Intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine in combination with dexmedetomidine is superior to bupivacaine alone and may be better than bupivacaine with tramadol.

Keywords: Bupivacaine hydrochloride, dexmedetomidine hydrochloride, intraperitoneal injection, pain, post-operative, tramadol hydrochloride

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as opposed to open cholecystectomy is currently the most accepted surgical technique for cholelithiasis.[1] Laparoscopic procedures have many advantages over open procedures such as lesser haemorrhage, better cosmetic results, lesser post-operative pain, and shorter recovery time, leading to shorter hospital stay and less expenditure.[2]

Pain results from stretching of the intra-abdominal cavity,[3] peritoneal inflammation, and diaphragmatic irritation caused by residual carbon-dioxide in the peritoneal cavity.[4] Many methods have been proposed to relieve post-operative pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[5]

Intraperitoneal instillation of local anaesthetic agents alone[5] or in combination with opioids,[6,7] ∝-2 agonists such as clonidine and[8] dexmedetomidine[6] have been found to reduce post-operative pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

The aim of this study was to compare the antinociceptive effects of intraperitoneal dexmedetomidine or tramadol combined with bupivacaine to intraperitoneal bupivacaine alone in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

METHODS

After getting approval from Institutional Ethical Committee, written informed consent was obtained from all the patients before surgery. One hundred and twenty patients of American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I-II of both sexes, aged between 18 and 60 years undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomies were included in this prospective, randomised, double-blind study conducted between November 2012 and August 2013. Patient who were allergic to local anaesthetic and study drugs, patients with acute cholecystitis, patients with severe cardiac, pulmonary, and neurological diseases, those in whom procedure had to be converted to open cholecystectomy, in whom abdominal drain was put were excluded from the study.

All patients were transported to the operating room without premedication. On arrival to operating room, an 18-gauge intravenous (IV) catheter was inserted and 6 ml/kg/h crystalloid was infused intraoperatively monitoring of electrocardiography, non-invasive blood pressure, oxygen saturation (SpO2) was started and baseline values were recorded. Pre-oxygenation with 100% oxygen (O2) was done for 3 min. General anaesthesia was induced with IV fentanyl 1.5 μg/kg, propofol 2.0–2.5 mg/kg followed by succinyl choline 2 mg/kg to facilitate orotracheal intubation. The trachea was intubated with a cuffed orotracheal tube of appropriate size, lubricated with lidocaine jelly 2%. Anaesthesia was maintained with 60% N2O in oxygen with 0.5–1% isoflurane. Intermittent boluses of vecuronium bromide were used to achieve muscle relaxation. Minute ventilation was adjusted to maintain normocapnia (end tidal carbon-dioxide [EtCO2] between 34 and 38 mm Hg) and EtCO2 was monitored. Nasogastric tube of appropriate size was inserted.

Hypotension/hypertension was defined as fall/rise in systolic blood pressure of >20% from the baseline values and bradycardia/tachycardia was defined as fall/rise in pulse rate of >20% from the baseline values. Haemodynamic fluctuations were to be managed accordingly. Patients were placed in 15-20° reverse Trendelenberg's position with the the left side tilt position. During laparoscopy, intra-abdominal pressure was maintained 12-14 mm Hg. The CO2 was removed carefully by manual compression of the abdomen at the end of the procedure with open trocar.

Patients were randomly allocated to one of the groups using table of randomisation, Group B (n = 40): Intraperitoneal bupivacaine 50 ml 0.25% +5 ml normal saline (NS), Group BT (n = 40): Intraperitoneal bupivacaine 50 ml 0.25% + tramadol 1 mg/kg (diluted in 5 ml NS) or Group BD (n = 40): Intraperitoneal bupivacaine 50 ml 0.25% + dexmedetomidine1 μg/kg (diluted in 5 ml NS),

Study drugs were prepared by an anaesthesiologist not involved in the study. Anaesthesiologist who observed the patient and surgeon were unaware of the study group until the end of the study. At the end of the surgery, the study solution was given intraperitoneally before removal of trocar in Trendelenberg's position, into the hepato-diaphragmatic space, on gall bladder bed and near and above hepatoduodenal ligament. The neuro-muscular blockade was antagonized with neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg and trachea was extubated. The nasogastric tube was removed, and the patient was shifted to post-anaesthesia care unit (PACU).

All patients stayed in PACU for 2 h after the end of surgery. The primary outcome variable was to compare pain (visual analogue scale [VAS]) score. The secondary outcome included time to the first request of analgesia in the post-operative period, total dose of analgesic used in 24 h period (post-operative) and any adverse/side effects.

The intensity of post-operative pain was recorded for all the patients using VAS score at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24 h after surgery and over all VAS score (mean of all VAS scores). All the study patients were instructed about the use of the VAS score before induction of anesthesia (VAS score 0 - no pain, VAS score 10 - worst possible pain). Patients who reported VAS 3 or >3 were given diclofenac 75 mg intramuscularly as rescue analgesia. Patients were also observed for post-operative nausea and vomiting. Patients who suffered nausea or vomiting were given ondansetron 4 mg IV. Time to the first request of analgesia (considering the extubation as time 0), total dose of analgesia and adverse or side effects over 24 h postoperatively were noted.

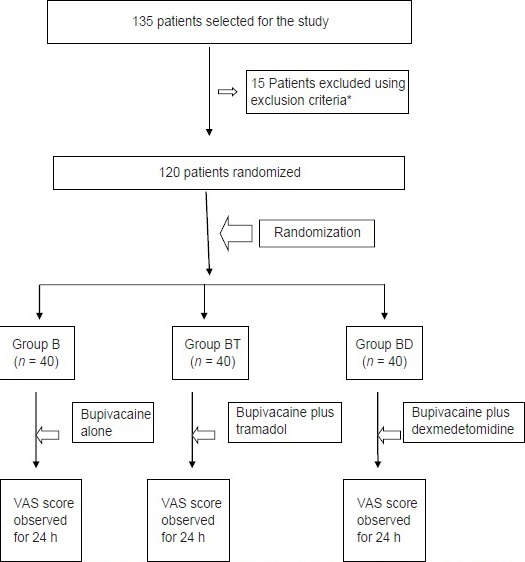

A total sample size of 120 patients (n = 40 each for three groups) was calculated using Power and Sample size calculator (PS version 3.0.0.34), assuming 30% improvement in pain scores with ∝ error of 0.05 and power of 80%. To obtain a 120 study sample size, a total of 135 patients were included; but 15 patients were excluded on the basis of exclusion criteria.

Consort diagram.

Patient randomisation and study design. *Out of excluded 15 patients, 11 were excluded because of associated severe co-morbid conditions while 4 were excluded during operative procedure and results of these were not included in the study so the sample size was limited to 120 patients

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft (MS) Office Excel Software (Microsoft Microsoft Excel, Redmond, Washington: Microsoft 2003, Computer software). Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, number and percentage (%). Data were analysed using post hoc analysis method. Normally distributed data were assessed using unpaired Student's t-test (for comparison of parameters among groups). Comparison was carried out using Chi-square (χ2) test with a P value reported at 95% confidence level. Level of significance used was P = 0.05.

RESULTS

There was no significant difference with respect to age, sex, weight and ASA physical status, duration of surgery and anaesthesia time [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of patients, operative data in studied groups (mean±SD)

A total of four patients were excluded from the study because of conversion to open procedure in BT Group and common bile duct injury in one patient in BD Group. However, no patient was excluded from the study because of unbearable pain, any cardiac event or patients’ intolerance.

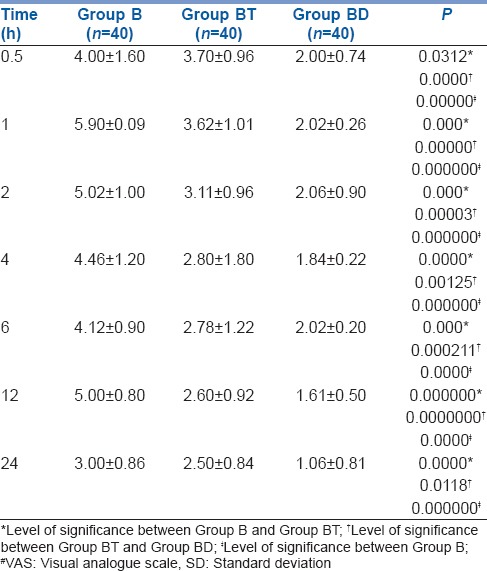

Visual analogue scale at different time intervals were statistically significantly lower at all times in Group BD than Group BT and Group B [Table 2]. Furthermore, overall VAS in 24 h was also significantly lower in Group BD (1.80 ± 0.36) than Group BT (3.01 ± 0.48) and Group B (4.5 ± 0.92) [Table 3].

Table 2.

Post-operative VAS# score (mean±SD) in studied groups

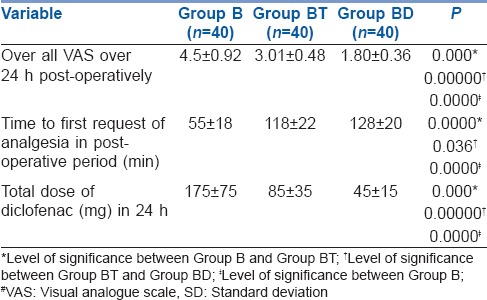

Table 3.

Post-operative overall VAS# score and analgesic requirements (mean±SD) in studied groups

Time to first request of analgesia was longest in Group BD (128 ± 20 min) as compared to BT (118 ± 22 min) and Group B (55 ± 18 min). Total diclofenac consumption was also lowest in Group BD (45 ± 15 mg) than Group BT (85 ± 35) and Group B (175 ± 75) [Table 3].

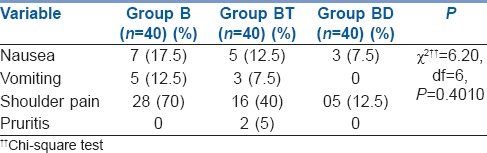

Overall analysis showed that adverse events were not statistically significantly different in all the three study groups (P = 0.4010) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Post-operative adverse/side effects (%) in studied groups

DISCUSSION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy results in better surgical outcome in terms of reduced post-operative pain, morbidity and duration of convalescence compared to open cholecystectomy.[1,2]

Post-operative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy consists of three components, visceral, parietal and referred shoulder pain distinguishable from each other in the intensity, latency and duration.[3] Previous studies[9,10] suggest that predominant cause of pain is parietal but in contrast many other studies emphasized that in early convalescent period, major portion is occupied by visceral pain because as compared to small incisions and limited trauma to the abdominal wall, the surgical manipulation and tissue destruction in visceral organs is much more.[11,12,13]

Multimodal efforts like parenteral opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or local wound infiltration have been done to reduce overall pain and benefit post-operative conditions of patients undergoing laparoscopic surgeries.[5,14,15,16] Despite their efficacy, with all parenteral medications, there are associated adverse effects.

In this modern era of surgery, intraperitoneal instillation of local anaesthetic agents has become an important method to control post-operative pain, nausea, vomiting and reduced hospital stay.[17,18] In laparoscopic surgeries because of gas insufflations and raised intraperitoneal pressure, there is peritoneal inflammation and neuronal rupture with a linear relationship between abdominal compliance and resultant severity of post-operative pain.[14] Hence, we chose intraperitoneal route because it blocks the visceral afferent signals and modifies visceral nociception. The local anaesthetic agents provide antinociception by affecting nerve membrane associated proteins and by inhibiting the release and action of prostaglandins which stimulates the nociceptors and cause inflammation.[19] Intraperitoneal instillation of 0.25% bupivacaine provide effective analgesia, in addition to this, we added either dexmedetomidine or tramadol to compare the antinociceptive efficacy if mixed with bupivacaine.

The antinociceptive effects of dexmedetomidine occurs at dorsal root neuron level, where it blocks the release of substance P in the nociceptive pathway and through action on inhibitory G protein, which increases the conductance through potassium channels.[20]

Golubovic et al.[21] assessed the analgesic effects of intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine and/or tramadol in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and concluded that intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine or tramadol or combination of both are effective method for management of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy and they significantly reduce post-operative analgesic and antiemetic medication. On the contrary, we found bupivacaine in combination with tramadol (Group BT) has significantly lower VAS score at all points of time (P < 0.05) and overall VAS score, and post-operative analgesia was statistically lower than with Group B.

Memis et al.[8] studied the effects of tramadol or clonidine added to intraperitoneal bupivacaine, on post-operative pain in total abdominal hysterectomy and found that combination of tramadol or clonidine with intraperitoneal bupivacaine to be more effective than bupivacaine alone. They found no significant difference between tramadol and clonidine groups in terms of efficacy but we found dexmedetomidine to have significantly better efficacy than tramadol in combination with bupivacaine. The prominent effect of dexmedetomidine may be due to its higher efficacy in our study and higher efficacy of clonidine in the study by Memis et al.[8]

There are very few studies in the literature which examined the analgesic effects of ἀ-2 agonists intraperitoneally.

Our results correlate with study done by Ahmed et al.[6] which has shown that intraperitoneal instillation of mepiridine or dexmedetomidine in combination with bupivacaine 0.25% significantly decreases the post-operative analgesic requirements and decreased incidence of shoulder pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic gynaecological surgeries.

Time to first request of analgesia in post operative period was significantly delayed in Group BD as compared to Group B (P = 0.000). Memis et al.[8] found no difference between tramadol or clonidine groups and in present study, the time was significantly shorter in tramadol group than dexmedetomidine group (P = 0.03).

Dose of diclofenac required in post-operative period, we found statistically higher doses are required in Group B as compared to Group BD or Group BT, (P = 0.00, 0.000 respectively) which was in agreement with Memis et al.[8] and Ahmed et al.[6] but by contrast Memis et al.[8] in their study found higher doses in clonidine group than tramadol group.

In our study, no statistically significant difference was found in regard to the adverse effects among the three study groups (P = 0.4010). Only 5 (12.5%) patients in Group BD suffered from shoulder pain as compared to 16 (40%) in Group BT and 28 (70%) patients in bupivacaine alone group. Incidence of shoulder pain was also lower in dexmedetomidine group in study done by Ahmed et al.[6]

Limitation of the present study is the post-operative pain, which is a subjective experience and can be difficult to quantify objectively and compare when comparing various treatment options.

As there are very few studies in the past on addition of dexmedetomidine to intraperitoneal bupivacaine, further studies with different doses of dexmedetomidine, timing, concentrations of local anaesthetics and routes of administration are needed to provide maximal benefit in terms of post-operative pain relief with minimal adverse effects after laparoscopic surgeries.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that intraperitoneal instillation of dexmedetomidine 1 μ/kg in combination with bupivacaine 0.25% in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy significantly reduces the post-operative pain and significantly reduces the analgesic requirement in post-operative period as compared to bupivacaine 0.25% alone and may be better than bupivacaine combined with tramadol.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim TH, Kang HK, Park JS, Chang IT, Park SG. Intraperitoneal ropivacaine instillation for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Korean Surg Soc. 2010;79:130–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisgaard T, Kehlet H, Rosenberg J. Pain and convalescence after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:84–96. doi: 10.1080/110241501750070510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernández-Palazón J, Tortosa JA, Nuño de la Rosa V, Giménez-Viudes J, Ramírez G, Robles R. Intraperitoneal application of bupivacaine plus morphine for pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20:891–6. doi: 10.1017/s0265021503001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esmat ME, Elsebae MM, Nasr MM, Elsebaie SB. Combined low pressure pneumoperitoneum and intraperitoneal infusion of normal saline for reducing shoulder tip pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2006;30:1969–73. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0752-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Labban GM, Hokkam EN, El-Labban MA, Morsy K, Saadl S, Heissam KS. Intraincisional vs intraperitoneal infiltration of local anaesthetic for controlling early post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy pain. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:173–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.83508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed B, Elmawgoud AA, Dosa R. Antinociceptive effect of (ἀ-2 adrenoceptor agonist) dexmedetomidine vs meperidine, topically, after laproscopic gynecologic surgery. J Med Sci. 2008;8:400–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golubovic S, Golubovic V, Cindric-Stancin M, Tokmadzic VS. Intraperitoneal analgesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Bupivacaine versus bupivacaine with tramadol. Coll Antropol. 2009;33:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Memis D, Turan A, Karamanlioglu B, Tükenmez B, Pamukçu Z. The effect of tramadol or clonidine added to intraperitoneal bupivacaine on postoperative pain in total abdominal hysterectomy. J Opioid Manag. 2005;1:77–82. doi: 10.5055/jom.2005.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma GR, Lyngdoh TS, Kaman L, Bala I. Placement of 0.5% bupivacaine-soaked Surgicel in the gallbladder bed is effective for pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1560–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantore F, Boni L, Di Giuseppe M, Giavarini L, Rovera F, Dionigi G. Pre-incision local infiltration with levobupivacaine reduces pain and analgesic consumption after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A new device for day-case procedure. Int J Surg. 2008;6(Suppl 1):S89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karaaslan D, Sivaci RG, Akbulut G, Dilek ON. Preemptive analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomized controlled study. Pain Pract. 2006;6:237–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pappas-Gogos G, Tsimogiannis KE, Zikos N, Nikas K, Manataki A, Tsimoyiannis EC. Preincisional and intraperitoneal ropivacaine plus normal saline infusion for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2036–45. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9762-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papadima A, Lagoudianakis EE, Antonakis P, Filis K, Makri I, Markogiannakis H, et al. Repeated intraperitoneal instillation of levobupivacaine for the management of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2009;146:475–82. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobias JD. Pain management following laparoscopy: Can we do better? Saudi J Anaesth. 2013;7:3–4. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.109553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdulla S, Eckhardt R, Netter U, Abdulla W. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial on non-opioid analgesics and opioid consumption for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2012;63:43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salihoglu Z, Yildirim M, Demiroluk S, Kaya G, Karatas A, Ertem M, et al. Evaluation of intravenous paracetamol administration on postoperative pain and recovery characteristics in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:321–3. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181b13933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahokehr A, Sammour T, Soop M, Hill AG. Intraperitoneal local anaesthetic in abdominal surgery-A systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:237–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bharadwaj N, Sharma V, Chari P. Intraperitoneal bupivacaine instillation for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Anaesth. 2002;46:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu SS, Hodgson PS. Local anaesthetics. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, editors. Clinical Anaesthesia. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippicott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 449–69. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamibayashi T, Maze M. Clinical uses of alpha2-adrenergic agonists. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1345–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200011000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golubovic S, Golubovic V, Tokmadzic VS. Intraperitoneal analgesia for laproscopic cholecystectomy. Periodicum Biologorum. 2009;3:263–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]