Abstract

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are seen in about 1–2% cases. Fixed drug reaction (FDR) is responsible for about 10% of all ADRs. It is a delayed type of hypersensitivity reaction that occurs as lesions recurs at the same skin site due to repeated intake of an offending drug. The most common drugs causing fixed drug eruption (FDE) are analgesics, antibiotics, muscle relaxants and anticonvulsants. FDE due to ciprofloxacin has been reported earlier also, but bullous variant of FDR is rare. We hereby report three case reports of bullous FDR caused due to ciprofloxacin.

Keywords: Bullous, ciprofloxacin, fixed drug reaction

Introduction

Ciprofloxacin is a widely used quinolone antibiotic since 1986. It is used against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative organism. It has excellent tissue penetration in the skin and soft tissue infections and is a well-tolerated drug. Side effects reported are nausea, abdominal discomfort, headache, dizziness.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are seen in about 1–2% of treated patients.[1] Urticaria angioedema, maculopapular exanthem, and photosensitivity are the most frequently documented cutaneous adverse reactions.[2] Fixed drug eruption (FDE) due to ciprofloxacin has been reported earlier.[3,4,5,6]

More severe reaction like Steven–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) can also occur with ciprofloxacin.[7,8] We hereby report three case reports of bullous fixed drug reaction (FDR) caused due to ciprofloxacin.

Case Report

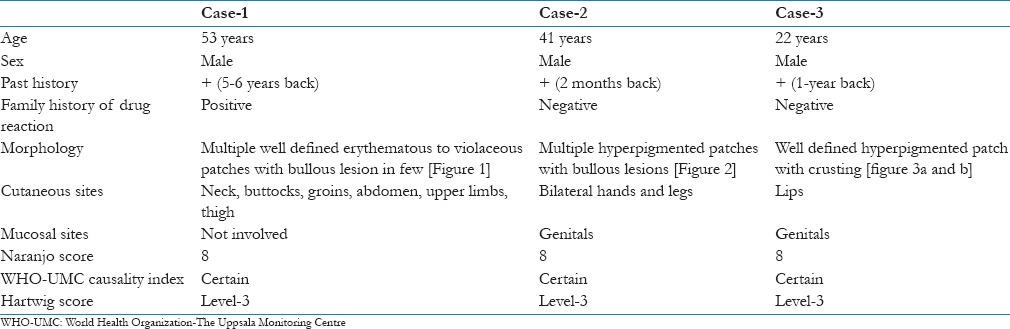

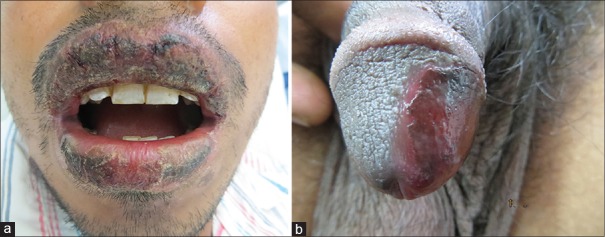

All the three patients presented with a history of lesions over the body after consuming ciprofloxacin. Symptoms in the form of burning sensations and itching were experienced by all of them. Lesions developed at different time duration after consumption of drugs but within 1-week duration [Table 1], [Figures 1-3a and b].

Table 1.

Clinico-epidemiological details of patients

Figure 1.

Multiple well defined erythematous to violaceous patches with bullous lesion in few over the back

Figure 3.

(a and b) Well-defined hyperpigmented patch with crusting over lips and genitals

Figure 2.

Hyperpigmented patches with bullous lesions over base of left thumb

All the patients were stable vitally. Routine complete blood count, renal function test and chest-X-ray were normal in all patients. All were treated with oral steroids in tapering dose that is, started with 40 mg/day of prednisolone, antihistamines, local soframycin and topical steroids were added in hyperpigmented lesions. All were given drug list that contained list of drugs that leads to FDR. They were advised to avoid all those group of drugs in the future.

Discussion

The term FDE was first introduced by Brocq in 1894.[9] It is a delayed type of hypersensitivity reaction that occurs as lesions recurs at the same skin site due to repeated intake of an offending drug.[10] The exact mechanism for this FDE is still unclear but, it has been postulated that FDE is due to a delayed classical type IVc hypersensitivity reaction mediated by CD8+ T cells.[11] The drug binds with basal keratinocytes and stimulates the inflammatory process by causing the release of lymphokines, mast cell and antibodies, which in turn causes damage to basal cell. CD8+ on activation causes release of interferon and cytotoxic granules.[12] A genetic susceptibility to develop a FDE with an increased incidence of human leukocyte antigen-B22 is also a possibility,[13] which is seen in our case-1 where patient had family history of drug reaction, while other cases had negative family history.

The peak incidence is usually between 21 and 40 years of age. Males have slightly higher predilection than female counterparts. It mostly occurs in patients who intermittently receive the causative agent rather than on continuous administration. It also tends to occur with other drugs similar in structure to the causative agent.

The list of causative drugs is long, including nonnarcotic analgesics, antibacterial agents, antifungal agents, antipsychotics, other miscellaneous drugs. Even ultraviolet radiation, emotional and psychiatric factors, heat, menstrual abnormalities, pregnancy, fatigue, cold, and undue effort can lead to FDE. Furthermore, it is difficult to pinpoint a culprit drug in subsequent episodes considering cross and polysensitivity.[9]

Ciprofloxacin was a considerable offender in 4.7%, in one case series[14] with all males similar to our cases. Norfloxacin-induced FDE has been reported less frequently and may have cross-sensitivity with ciprofloxacin.[5]

Fixed drug eruption presents mainly as sharply marginated, round or oval itchy plaques of erythema and edema becoming dusky violaceous or brown and sometimes vesicular or bullous lesions on the lip, hip, sacrum, or genitalia.[15] Most of the reactions occur within 30 min to 1-day of drug exposure.[16] Subsequent reexposure to the medication results in a reactivation of the site, with inflammation occurring within 30 min to 16 h.[17] The lesions may be solitary or multiple. The most common sites are the genitalia in males and the extremities in females.

Several variants of FDE have been described, based on their clinical features and distribution of lesions[18] including pigmented, generalized,[19] linear, nonpigmenting, bullous, eczematous, urticarial erythema dyschromicum perstans, vulvitis, psoriasiform or cellulitis.

Lesions may persist from days to weeks and then fade slowly to residual oval hyperpigmented patches.[20] The reactivation of old lesions also may be associated with the development of new lesions at other sites. The severity of reactions in FDE may increase after repeated exposures to the drug and very rarely progress to a clinical state called generalized bullous FDE, which is seen in case-1. It may be clinically misdiagnosed as SJS or TEN.[19] In generalized bullous FDE, the disease onset is within hours after the drug exposure. A diagnostic hallmark is the reappearance of the lesions over the previously affected sites, when the offending drug is reused. Mucosal sites are usually spared as in our case-1 but can be involved as seen in case-2 and 3. Histologically, FDE is characterized by marked basal cell hydropic degeneration with pigmentary incontinence. Scattered keratinocyte necrosis with eosinophilic cytoplasm and pyknotic nucleus (civatte bodies) are seen in the epidermis. Infiltration of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and neutrophil polymorphs is evident in the upper dermis.[21]

Rechallenging the patient to the suspected offending drug is the only known test to possibly discern the causative agent, but that is unethical and not advisable. Therefore, certain causality assessment scales regarding drug reaction have been described like the Naranjo ADR probability scale, WHO-Uppsala Monitoring Centre causality assessment system and Hartwig scale.[22,23,24]

Treatment includes stopping the offending drug with oral and topical steroids, emollients, and oral antihistamines. Though usually not fatal, FDE can cause enough cosmetic embarrassment especially when they recur on the previously affected sites leaving behind residual hyperpigmentation.

Conclusion

Pharmacovigilance for detecting and diagnosing ADR by practicing physicians, general practitioners and family physicians is an essential armament of their clinical acumen. It is also important to report ADRs, which can help detect and prevent drug reactions and in turn decrease the cost of treatment. Ciprofloxacin is commonly used antibiotic, it is important for prescribing physician to keep in mind that it can also lead to bullous FDR.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rönnau AC, Sachs B, von Schmiedeberg S, Hunzelmann N, Ruzicka T, Gleichmann E, et al. Cutaneous adverse reaction to ciprofloxacin: Demonstration of specific lymphocyte proliferation and cross-reactivity to ofloxacin in vitro. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:285–8. doi: 10.2340/0001555577285288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campi P, Pichler WJ. Quinolone hypersensitivity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;3:275–81. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200308000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawada A, Hiruma M, Morimoto K, Ishibashi A, Banba H. Fixed drug eruption induced by ciprofloxacin followed by ofloxacin. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31:182–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1994.tb01962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bose SK. Ciprofloxacin-induced bullous fixed drug eruption. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1995;61:238–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alonso MD, Martín JA, Quirce S, Dávila I, Lezaun A, Sanchez Cano M. Fixed eruption caused by ciprofloxacin with cross-sensitivity to norfloxacin. Allergy. 1993;48:296–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1993.tb00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhar S, Sharma VK. Fixed drug eruption due to ciprofloxacin. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:156–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hällgren J, Tengvall-Linder M, Persson M, Wahlgren CF. Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with ciprofloxacin: A review of adverse cutaneous events reported in Sweden as associated with this drug. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(5 Suppl):S267–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)00478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandal B, Steward M, Singh S, Jones H. Ciprofloxacin-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) in a nonagerian: A case report. Age Ageing. 2004;33:405–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Fixed drug eruption (FDE): Changing scenario of incriminating drugs. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:897–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanmukhani J, Shah V, Baxi S, Tripathi C. Fixed drug eruption with ornidazole having cross-sensitivity to secnidazole but not to other nitro-imidazole compounds: A case report. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:703–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y, Teraki Y. Pathophysiology of fixed drug eruption: The role of skin-resident T cells. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:317–23. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200208000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: Pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316–21. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32832cda4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pellicano R, Lomuto M, Ciavarella G, Di Giorgio G, Gasparini P. Fixed drug eruptions with feprazone are linked to HLA-B22. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:782–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fayez R, Obaidat N, Al-Qaqaa A, Al-Rawashdeh B, Maaita M, Al-Azab N. Drugs causing fixed drug eruption: A clinical study. J Res Med Sci. 2011;18:16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breathnach SM. Drug reactions. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010. pp. 28–177. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brahimi N, Routier E, Raison-Peyron N, Tronquoy AF, Pouget-Jasson C, Amarger S, et al. A three-year-analysis of fixed drug eruptions in hospital settings in France. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:461–4. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. In: Dermatology. London, England: Mosby; 2003. Fixed drug eruptions; pp. 344–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozkaya-Bayazit E, Bayazit H, Ozarmagan G. Drug related clinical pattern in fixed drug eruption. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:288–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ada S, Yilmaz S. Ciprofloxacin-induced generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:511–2. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.44324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI. In: Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. Fixed drug eruptions; p. 1333. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiatt KM, Horn TD. Cutaneous toxicities of drugs. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, Murphy GF, Xu X, editors. Levers Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. New Delhi: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 311–31. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The use of the WHO-UMC system for standardised case causality assessment. [Last accessed on 2 Dec 2014]. Available from: http://www-who.umc.org/graphics/24734.pdf .

- 23.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartwig SC, Siegel J, Schneider PJ. Preventability and severity assessment in reporting adverse drug reactions. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49:2229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]