Abstract

Kyrle's disease (KD) is an acquired perforating dermatosis associated with an underlying disorder such as diabetes mellitus or chronic renal failure. It presents as multiple discrete, eruptive papules with a central crust or plug, often on the lower extremities. A keratotic plug is seen histologically in an atrophic epidermis and may penetrate the papillary dermis with transepidermal elimination of keratotic debris without collagen or elastic fibers. Various therapies have been reported that include cryotherapy, laser therapy, narrow-band ultraviolet B and use of topical or systemic retinoids. Hereby a case of 64-year-old male, a known case of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and chronic renal failure who developed KD is presented.

Keywords: Chronic renal failure, keratotic plug, Kyrle's disease

Introduction

Kyrle's disease (KD) is a rare skin disorder characterized by transepidermal elimination of abnormal keratin. It is classified as a subtype of acquired perforating dermatosis along with reactive perforating collagenosis, elastosis perforans serpiginosa and perforating folliculitis.[1] It is commonly seen in patients with diabetes, renal disease and rarely in liver disease.[2] KD is regarded as a genetically determined disease with onset during adulthood usually between the age of 30 and 50 years but onset as early as age 5 years and as late as 75 years has been reported with[3] female-to-male ratio of up to 6:1.[4]

It presents as multiple discrete, eruptive papules with a central crust or plug, often on the lower extremities. The first line therapy of KD is keratolytics (salicylic acid and urea) followed by electrocautery or radiocautery.

Case Report

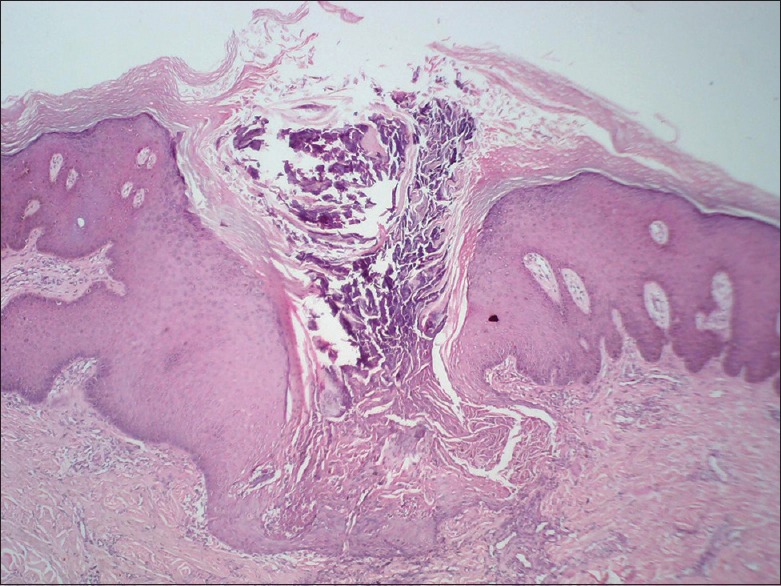

A 64-year-old male presented to Skin Department with complaints of lesions over body since 1 month with severe itching. The lesions initially began over right leg which progressed to involve both lower limbs, back, hands, face and scalp. He was a known case of diabetes and hypertension since 25 years on regular treatment. Patient was on hemodialysis since 1 year (twice a week) for chronic renal failure. On investigations his serum creatinine was 15.45 mg/dl, serum uric acid was 9.1 mg/dl, and HBA1c was 7.8%. Urine routine and microscopy showed glucose 2 + and protein 3+, fasting blood sugar 180 mg/dl and post-prandial blood sugar 200 mg/dl. Ultrasonography of abdomen and pelvis revealed right kidney size to be 8 × 3 cm and left kidney size to be 8.5 × 3 cm. Rest of the investigations were in normal limits. On examination multiple, large, discrete hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic papules with central crusted keratotic plugs over bilateral extremities [Figure 1], back, neck, face and scalp were seen. Linear distribution of lesions was seen over bilateral thighs showing koebnerization [Figure 2]. Biopsy taken from one of the papule from right leg showed irregular epithelial hyperplasia with follicular cornified plug and focal parakeratosis. The plug contained basophilic degenerated material [Figure 3]. The upper dermis showed moderate lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates favoring the diagnosis of KD. The patient was given oral antihistamines, topical retinoids and emollients.

Figure 1.

Multiple discrete hyperkeratotic papules on bilateral lowerlimbs

Figure 2.

Koebnerization over right lateral thigh

Figure 3.

Follicular cornified plug with focal parakeratosis (H and E, ×4)

The patient was seen after 15 days with symptomatic improvement in the form of reduced intensity of itching. After 1 month lesions started regressing.

Discussion

Kyrle first described this disorder in 1916 under the name hyperkeratosis follicularis et parafollicularis in cutem penetrans.[5] Perforating disorders (PD) are a heterogeneous group of disorders which are categorized into four types based on physical and pathological investigations sharing the common characteristics of transepidermal elimination as elastosis perforans serpiginosa, reactive perforating collagenosis, perforating folliculitis and KD.[6]

Kasiakou et al.,[7] suggested an infectious etiology while abnormal keratinization been proposed by Tappeiner et al.[8] Detmar et al.,[9] suggested that defective differentiation of the epidermis and the dermoepidermal junction owing to alteration of the underlying glycosylation process may be responsible for the lesions. Elevated serum and tissue concentrations of fibronectin may be responsible for inciting increased epithelial migration and proliferation, culminating in perforation was suggested by Morgan et al.[10]

It has been found to be associated with renal failure and diabetes, shown by the report of Saray et al.,[11] in which among 22 patients with PD, 72% had chronic renal failure and 50% had diabetes. Among patients with diabetes and PD, 90% had chronic renal failure. In a report involving 21 cases of KD, 19 cases presented with a renal disorder and 12 cases had diabetes.[12]

The pathogenesis associated with diabetes mellitus is unknown, it may be an outcome of changes in the epidermis or dermis leading to metabolic derangements and a cutaneous response to the superficial trauma and vasculopathy arising from products of oxidative damage or endoplasmic stress like advanced glycation end products and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL).[13]

The mode of inheritance of KD is unclear as both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive patterns have been reported.[14]

It is characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and nodules, with a central keratotic plug most commonly on the lower extremities with marked disposition for calf, tibial region and posterior aspect.[3] Arms, head and neck region are also involved while palms and soles are involved rarely. Koebner phenomenon has been noted in some cases like in our case.[4]

Along with diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure, it is also seen with tuberculosis, pulmonary aspergillosis, scabies, atopic dermatitis, AIDS, neurodermatitis, malignancy, hepatic disorders, congestive heart failure and endocrinological disorders.[3,11]

Cases of Kryle's disease are reported like ours in patients with renal failure.[11,15,16,17] It occurs in 10% of dialysis patients like our case[18] Nine cases of KD among 200 patients underwent hemodialysis because of chronic renal failure[19]

A keratotic plug is seen histologically in an atrophic epidermis penetrating papillary dermis with underlying dermal histiocytic and lymphocytic infiltrate, which constitutes the foreign body granulomatous reaction. Orthokeratosis, parakeratosis and abnormal keratinization are seen sometimes. Transdermal elimination of collagen, elastic fibers and degenerated follicular contents with or without collagen or elastic fibers is seen in RPC, EPS and PF, respectively while transdermal elimination of keratotic material with no collagen or elastic fibers is observed in KD.[6]

The first line therapy for treatment of KD is keratolytics (salicylic acid and urea) followed by electrocautery, cryotherapy or CO2 laser surgery. Surgical excision is considered as the last option. Other options include ultraviolet irradiation after curetting the hyperkeratosis along combination of oral retinoids and psoralen plus Ultraviolet A radiation.[20] Isotretinoin, high-dose vitamin A and tretinoin cream are also effective.[20] Emollients and oral antihistamines are useful in relieving pruritus. Oral clindamycin (300 mg) three times a day for 1 month can be given with good results. Discontinuation of these treatments usually results in recurrence of the lesions[19]

Conclusion

KD is a rare entity which has potential to adversely affect the quality of life. Therefore physicians need to have high index of suspicion for KD in patients with diabetes along with concomitant renal disease. Any suspicious lesion should be biopsied, sent for histopatholgy, to confirm the diagnosis and start the treatment at the earliest.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rapini RP. Perforating diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, editors. Dermatology. London, England: Mosby; 2003. pp. 1497–502. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harman M, Aytekin S, Akdeniz S, Derici M. Kyrle's disease in diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1998;11:87–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.1998.tb00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shivakumar V, Okade R, Rajkumar V, Prathima KM. Familial Kyrle's disease: A case report. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:770–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham SR, Walsh M, Matthews R, Fulton R, Burrows D. Kyrle's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:117–23. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss HV. Kyrle's disease. Cutis. 1979;23:463–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michael K.Miller, Narayan S.Naik, Carlos H.Nousari, Robert J.Friedman, Edward R.Heilman. Degenrative diseases & perforating disorders. In: David E.Elder, Rosalie Elenitsas Bernett, Johnson L, Jr, George F Murphy, Xiaowei Xu., editors. In: Lever's Histopathology of skin. 10th edition. Philadelphia: 2009. pp. 389–405. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasiakou SK, Peppas G, Kapaskelis AM, Falagas ME. Regression of skin lesions of Kyrle's disease with clindamycin: Implications for an infectious component in the etiology of the disease. J Infect. 2005;50:412–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tappeiner J, Wolff K, Schreiner E. Kyrle's disease. Hautarzt. 1969;20:296–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Detmar M, Ruszczak Z, Imcke E, Stadler R, Orfanos CE. Kyrle's disease in juvenile diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure. Z Hautkr. 1990;65:53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan MB, Truitt CA, Taira J, Somach S, Pitha JV, Everett MA. Fibronectin and the extracellular matrix in the perforating disorders of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:147–54. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199804000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: Clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:679–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph D, Papali C, Pisharody R. Kyrle's disease: A cutaneous marker of renal disorder. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996;62:222–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swetha C, Samuel Sathweek R, Srinivas B, Unnikrishnan R, Anjana RM, Mohan V. A case of Kyrle's disease with diabetes and renal insufficiency. J Diabetol. 2014;2:6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golusin Z, Poljacki M, Matovi’ c L, Tasić S, Vucković N. Kyrle's disease. Med Pregl. 2002;55:47–50. doi: 10.2298/mpns0202047g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akcali C, Baba M, Seçkin D, Kayaselçuk F, Gulec T. Kyrle's Disease: A Case Report. J Turk Acad Dermatol. 2007;1:71401c. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhambri S, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N, Janda P. Kyrle's Disease. Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;21:1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sastry AS, Sahoo AK, Sagar MK, Mahapatra SC. IOSR Kyrle's Disease: A Case Report. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2014;13:21–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.White CR, Jr, Heskel NS, Pokorny DJ. Perforating folliculitis of hemodialysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:109–16. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198204000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hood AF, Hardegen GL, Zarate AR, Nigra TP, Gelfand MC. Kyrle's disease in patients with chronic renal failure. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:85–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elisabeth CH, Schreiner W. Kyrle's disease and other perforating disorders. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Katz SI, Goldsmith LA, editors. In: Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies; 2003. pp. 537–42. [Google Scholar]