Abstract

The search for new bioactive substances with anticancer activity and the understanding of their mechanisms of action are high-priorities in the research effort toward more effective treatments for cancer. The phenylpropanoids are natural products found in many aromatic and medicinal plants, food, and essential oils. They exhibit various pharmacological activities and have applications in the pharmaceutical industry. In this review, the anticancer potential of 17 phenylpropanoids and derivatives from essential oils is discussed. Chemical structures, experimental report, and mechanisms of action of bioactive substances are presented.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a global health concern that causes mortality in both children and adults. More than 100 distinct types and subtypes of cancer can be found within specific organs [1]. Despite the success of several cancer therapies, an ideal anticancer drug has not been discovered, and numerous side effects limit treatment. However, research into new drugs has revealed a variety of new chemical structures and potent biological activities that are of interest in the context of cancer treatment.

Essential oils are natural products that are a mixture of volatile lipophilic substances. The chemical composition of essential oils includes monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and phenylpropanoids, which are usually oxidized in an aliphatic chain or aromatic ring. Several studies have shown that this chemical class has several biological activities, including analgesic, anticonvulsant, and anti-inflammatory effects [2–4]. Antitumor activity has been reported for essential oils against several tumor cell lines [5–7], and these oils contain a high percentage of phenylpropanoids, which are believed to contribute to their pharmacological activity [8, 9].

This paper presents a literature review of phenylpropanoids from essential oils with respect to antitumor activity, with chemical structures and names of bioactive compounds provided. The phenylpropanoids presented in this review were selected on the basis of effects shown in specific experimental models for evaluation of antitumor activity and/or by complementary studies aimed at elucidating mechanisms of action (Table 1). The selection of essential oil constituents in the database was related to various terms, including essential oils and phenylpropanoids, as well as names of representative compounds of chemical groups, and refined with respect to antitumor activity, cytotoxic activity, and cytotoxicity. The search was performed using scientific literature databases and Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) in November 2013.

Table 1.

Essential oil phenylpropanoids with antitumoral activity.

| Compound | Experimental protocol | Antitumoral activity and/or mechanism | Animal/cell line tested | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anaphylaxis model | Apoptotic manifestations via phospho-ser 15-p53 into mitochondria | Mast cells | [11] |

| Skin carcinogenesis model | Inhibition of the proliferation associated genes c-Myc and H-ras and antiapoptotic gene Bcl2 along with upregulation of proapoptotic genes Bax, p53, and active caspase-3 | Mice | [12] | |

| Trypan-blue assays | Cytotoxic activity | B16-F10, Sbcl2, WM3211, WM98-1 and WM1205Lu, PC-3, human gingival fibroblasts, oral mucosal, neutrophils—male guinea pig, rat hepatocytes cells | [14, 15, 23, 32, 33, 48, 49] | |

| Melanoma cell proliferation | Deregulation of the E2F family of transcription factors, transcriptional activity of E2F1 | Sbcl2, WM3211, WM98-1, and WM1205Lu cells | [15] | |

| Flow cytometry analysis | Cytotoxic activity | P-815, K-562, CEM, and MCF-7 cells | [13] | |

| VL irradiation time | Antioxidative reactivity | HSG, HSC-2, and HL-60 cells | [17] | |

| MTT assay | Cytotoxic activity | B16-F10, P-815, K-562, CEM, MCF-7, MCF-7 gem, HeLa, DU-145, KB, HSG, human dental pulp, murine peritoneal macrophages HL-60, HepG-2, B16, cells | [13, 19–22, 25–29, 38, 45, 46, 48] | |

| DPPH assay | Antioxidative activity | Caco-2 cells and VH10 fibroblasts | [18] | |

| Flow cytometer analysis | Enhanced the accumulation of cells in the S and G2/M phase which may be unable to divide | HeLa cells | ||

| DAPI staining | Increase in the number of apoptotic cells | |||

| In vitro hemolytic activity | Hemolytic activity | Human erythrocytes | [19] | |

| Caspase-3 colorimetric assay | Induce caspase 3-mediated apoptosis | |||

| RT-PCR | Anticancer activities via apoptosis induction and anti-inflammatory downregulation of Bcl-2, COX-2, and IL-1β | |||

| RT-PCR | Downregulated the expression of Bcl-2, COX-2, and IL-β | HeLa cells | [20] | |

| Flow cytometer analysis | Increased population of cells G2/M phase by 4.5-fold | PC-3 cells | [24] | |

| Western blot and RT-PCR analysis | Reduced expression of antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and enhanced expression of proapoptotic protein Bax | |||

| DPPH radical-scavenging activity | Formation of dimers | HSG cells | [25] | |

| ELISA | Reduced the nicotine-induced ROS, NO generation, and iNOSII expression | Murine peritoneal macrophages | [27] | |

| Spectrophotometric analysis | Increase in LDH release | DU-145 and KB cells | [28] | |

| ESR analysis | Activity of the production of phenoxyl radicals with most efficiently scavenged reactive oxygen | HSG cells | [29] | |

| Laser cytometry analysis | Production of ROS induced by VL-irradiated is significantly affected by pH | |||

| Antioxidants production | Produced antioxidants in alkaline solutions | Human salivary gland and oral squamous cells | [30] | |

| DPPH assay | Apoptosis-inducing effect | HGF and HSG cells | [31] | |

| TBA analysis lipid oxidation | Depleted intracellular glutathione; protect cells from the genetic attack of reactive oxygen species via inhibition of xanthine oxidase activity and lipid peroxidation | Oral mucosal fibroblasts | [32] | |

| ATP assay | Decreased cellular ATP level in a concentration- and time-dependent manner | |||

| NR assay | Intracellular glutathione levels | HFF and HepG2 cells | [33] | |

| Dichlorofluorescein assay | Reduction in the intracellular level of GSH | HSG cells | [34] | |

| CAs assay | Induced a dose-dependent increase of aberrant cells | V79 cells | [41] | |

| Topo II activity assay | Inhibition of topoisomerase II | |||

| Croton oil induced skin carcinogenesis | Inhibition of the proliferation associated genes c-Myc and H-ras and antiapoptotic gene Bcl2 along with upregulation of proapoptotic genes Bax, p53, and active caspase-3 | Swiss mice | [36] | |

| DMBA/TPA-induced carcinogenesis in murine skin | Declined of hyperplasia, epidermal ODC activity, and protein expression of iNOS, COX-2, and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines | Swiss mice | [42] | |

| TUNEL assay | Upregulation of p53 expression with a concomitant increase in p21WAF1 levels in epidermal cells indicating induction of damage to the DNA | |||

| Flow cytometric analysis | cDNA array analysis showed that eugenol caused deregulation of the E2F family of transcription factors | WM1205Lu cells | [24] | |

| TUNEL assay | Induces apoptosis in melanoma tumors | WM1205Lu cells | ||

| DPPH assay | Antioxidative properties | HL-60 and HepG-2 cells | [48] | |

| Sulforhodamine B assay | Cytotoxic activity | SK-OV-3, XF-498, and HCT-15 cells | [76] | |

| Murine Ehrlich ascites and solid carcinoma models | Inhibit the growth of Ehrlich ascites | BALB/c mice | [44] | |

| DPPH assay | Antioxidation activity | HepG2 cells | [22] | |

| Western blot analysis | Decreased the protein expression of BSP in a concentration-dependent manner | Human dental pulp cells | [35] | |

| DPPH assay | Antioxidant effect | Raw 264.7 cells | [43] | |

| VL irradiation/MTT assay | Generation of eugenol radicals | HSG and HGF cells | [36] | |

| Laser cytometer | Generation of ROS | |||

| ESR analysis | Produced phenoxyl radicals | HSG and HGF cells | [37] | |

| Superoxide generation/spectrophotometer | Stimulation the production of superoxide (O2 −) | Neutrophils—male guinea pig | [40] | |

|

| ||||

|

DPPH assay | Antioxidative properties | HL-60 and HepG-2 cells | [48] |

| UDS assay | Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity effects | B6C3F1 mouse hepatocytes | [47] | |

| F-344 rat hepatocytes | ||||

| L-Lactate assay | Cytotoxic effect | B6C3F1 mouse hepatocytes | ||

| F-344 rat hepatocytes | ||||

| MTT assay DPPH assay |

Cytotoxic activity Antioxidative properties |

HL-60, HepG-2, WM266-4, SK-Mel-28, LCP-Mel, LCM-Mel, PNP-Mel, CN-MelA, and GR-Mel cells | [16, 48] | |

| WST assay SRB assay |

Cytotoxic and genotoxic properties | V79 cells | [49] | |

| Corn oil gavage | Carcinogenic activity is based on increased incidences of hepatocellular adenoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hepatocellular adenoma or carcinoma (combined) | F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice | [50] | |

| Trypan-blue exclusion assay | Cytotoxic activity | Rat hepatocytes | [55] | |

|

| ||||

|

MTT assay |

Cytotoxic activity |

HSG cells | [29] |

| DPPH radical-scavenging activity | Cormation of dimers | |||

| Dichlorofluorescein assay |

Reduction in the intracellular level of GSH |

[39] | ||

|

| ||||

|

MTT assay | Inhibition of cell proliferation | WM266-4, SK-Mel-28, LCP-Mel, LCM-Mel, PNP-Mel, CN-MelA, and GR-Mel cells | [16] |

|

| ||||

|

WST assay SRB assay |

Cytotoxic and genotoxic properties | V79 cells | [49] |

|

| ||||

|

L-Lactate assay | Cytotoxic effect | B6C3F1 mouse hepatocytes | [47] |

| F-344 rat hepatocytes | ||||

| UDS assay | Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity effects | B6C3F1 mouse hepatocytes | ||

| F-344 rat hepatocytes | ||||

| Trypan-blue exclusion assay | Potential cytotoxic effects | Rat hepatocytes and SCC-4 cells | [47, 51, 54] | |

| Flow cytometric assay | Induction of apoptosis of cells by involvement of mitochondria- and caspase-dependent signal pathway | SCC-4 cells | [51] | |

| Western blotting analysis | Upregulation of the protein expression of Bax and Bid and downregulation of the protein levels of Bcl-2 (upregulation of the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2), resulting in cytochrome c release, promoted Apaf-1 level, and sequential activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 in a time-dependent manner | |||

| Real-time PCR | mRNA expressions of caspases 3, 8, and 9 | |||

| MTT assay | Cytotoxic effect | Human BMFs | [52] | |

| Western blot analysis | Activate NF-κB expression that may be involved in the pathogenesis of OSF and mediated by ERK activation and COX-2 signal transduction pathway | |||

| Fura-2 as a probe assay | Induced a [Ca2+]i increase by causing Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum in a phospholipase C- and protein kinase C-independent fashion and by inducing Ca2+ influx | PC3 cells | [53] | |

| Comet assay/(DAPI) staining | Induced apoptosis (chromatin condensation) and DNA damage | HL-60 cells | [51] | |

| Flow cytometric analysis | Increased the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Ca2+ and reduced the mitochondrial membrane potential | |||

| Western blotting analysis/confocal laser microscopy | Promoted the expression of glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), growth arrest- and DNA damage-inducible gene 153 (GADD153), and activating transcription factor 6α (ATF-6α) | |||

| Flow cytometric analysis | Promoted the levels of CD11b and Mac-3 that might be the reason for promoting the activity of phagocytosis; reduced the cell population such as CD3 and CD19 cells |

NK cells | [58] | |

| Ames test | Mutagenicity activity | Salmonella TA 98 | [59] | |

|

| ||||

|

MTT assay |

Produced toxicity in cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner |

HepG2 cells FVB mice |

[56] |

| Comet assay | Significant dose-dependent increase in the degree of DNA (strand breaks) | |||

| Cytotoxic or genotoxic effect in vivo—i.p./Comet assay | Increase in mean Comet tail moment in peripheral blood leukocytes and in the frequency of micronucleated reticulocytes | HepG2 cells FVB mice |

||

| TUNEL assay | Activity of caspases 3, 8, and 9 | A549 cells | [58] | |

|

| ||||

|

Western blot assay | Cleavages of PARP, accompanied by an accumulation of cytochrome c and by the activation of caspase-3 | SK-N-SH cells | [60] |

|

| ||||

|

Induction of GST and QR |

Induction of GST and QR in mouse livers |

Four strains of mouse: A/JOlaHsd, C57BL/6NHsd, BALB/cAnNHsd, and CBA/JCrHsd |

[61] |

| Trypan-blue exclusion assay |

Cytotoxic activity |

Rat hepatocytes |

[55] |

|

|

| ||||

|

Trypan-blue assay | Cytotoxic activity | HeLa, rat hepatocytes cell | [21, 23, 55, 64] |

| MTT assay | Cytotoxic activity | HT-1080, ML1-a cells | [63] | |

| Boyden-chamber assay | Reduced 40 and 85% of cells to invade into Matrigel |

HT-1080 cells | [62] | |

| Gelatin zymography and RT-PCR analyses | Inhibitory effect of MMP-2 and MMP-9 and downregulate the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) 2 and 9 and upregulate the gene expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase- (TIMP-) 1 | |||

| Expression of MMPs, TIMPs, and uPA assays | Decreased mRNA expression of urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) | |||

| Western blot analysis | Suppressed the phosphorylation of AKT, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38, and nuclear transcription factor kappa B (NF-κB) | |||

| Fluorometric assay | Increases in the levels of ADP and AMP | Rat hepatocytes | [62] | |

| CCK-8 assay | Estrogenic effect based on the concentrations of the hydroxylated intermediate, 4OHPB | MCF-7 cells | ||

| Western blot analysis | Suppressed TNF-induced activation of the transcription factor AP-1, c-jun N-terminal kinase, and MAPK-kinase | ML1-a cells | [63] | |

| Colorimetric e fluorometric assays | Reduced the levels of nucleic acids and MDA, and increased NP-SH concentrations | EAT cells in the paw of Swiss mice | [65] | |

|

| ||||

|

Ames test |

Mutagenic for Salmonella tester strains |

Salmonella typhimurium strains TA1535, TA100, and TA98 |

|

| Induction of hepatic tumors | Carcinogenic in the induction of hepatomas | B6C3F1 mice | [67] | |

| Induction of skin papillomas |

Carcinogenic in the induction of skin papillomas |

CD-1 mice |

||

|

| ||||

|

SRB assay | Cytotoxic activity | A549, SK-OV-3, SK-MEL-2, and HCT15 cells | [70] |

|

| ||||

|

Ames test |

Mutagenic for Salmonella tester strains |

Salmonella typhimurium strains TA1535, TA100, and TA98 |

|

| Induction of hepatic tumors | Carcinogenic in the induction of hepatomas | B6C3F1 mice | [67] | |

| Induction of skin papillomas |

Carcinogenic in the induction of skin papillomas |

CD-1 mice |

||

|

| ||||

|

MTT assay | Cytotoxic activity | A375, HCT 116, MCF-7, P388, L-1210, 3LL, SNU-C5, HL-60, U-937, HCT 116, L1210 mouse, and Syrian hamster embryo cells | [71, 77, 78, 80, 84, 89] |

| TRPA1 and TRPM8 gene expression | Reduce the proliferation of melanoma cells; this effect is independent of an activation of TRPA1 channels | A375, G361, SK-Mel-19, SK-Mel-23, and SK-Mel-28 cells | [77] | |

| Sulforhodamine B assay | Cytotoxic activity | HeLa, A549, SK-OV-3, SK-MEL-2, XF-498, and HCT-15 cells | [76] | |

| Ames test | Not mutagenic | Strains (TA 98, TA 100, TA 1535, and TA 1537) of Salmonella typhimurium | ||

| DTNB assay | TrxR inactivation | Recombinant rat TrxR | [78] | |

| Western blot analysis | Induced an adaptive antioxidant response through Nrf2-mediated upregulation of phase II enzymes, including TrxR induction | HCT 116 cells | ||

| XTT assay | Inhibitory effects on the growth of cells | Hep G2 cells | [80] | |

| Western blot analysis | Increase in the CD95 (APO-1/CD95) protein expression in Hep G2 cells | |||

| Inhibited the expression of Bax, p53, and CD95, as well as the cleavage of PARP. This pretreatment also prevented the downregulation of Bcl-XL in cells | ||||

| Trypan-blue assay | Inhibited the proliferation of cells | PLC/PRF/5 cells | [81] | |

| Flow cytometer analysis | Activation of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family (Bax and Bid) proteins and MAPK pathway |

PLC/PRF/5 cells | [83] | |

| Western immunoblot analysis | Prevented the phosphorylation of JNK and p38 proteins | |||

| DAPI/Fluorometric method | Induced apoptosis in cells | P388, L-1210, 3LL, SNU-C5, HL-60, U-937, and HepG2 cells | [71] | |

| Flow cytometry analysis | Induces the ROS-mediated mitochondrial permeability transition and resultant cytochrome c release | |||

| cis-DDP-induced | Potentiated the inactivating effect of cis-DDP in all phases of the cell cycle | NHIK 3025 cells | [82] | |

| NRU assay | Induced the fragmentation of nuclei (Plate 2), which is typical for condensed apoptotic phenotype |

Hep-2 cells | [87] | |

| Genotoxicity assays—DNA repair test | Involve DNA damage as one of the factors involved in the mammalian cytotoxicity | |||

| LDH-cytotoxicity assay | Potent inhibitory effect against human hepatoma cell growth | HepG2 and Hep3B cells | [88] | |

| Western blot analysis | JAK2-STAT3/STAT5 pathway may be important targets | |||

| Decreased the protein levels of cyclin D1 and proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) but increased the protein levels of p27Kip1 and p21Waf1/Cip1 | ||||

| Flow cytometry analysis | Inducing apoptosis and synergizing the cytotoxicity of CIK cells | K562 cells | [92] | |

| Spectral analysis | Induced an adaptive antioxidant response through Nrf2-mediated upregulation of phase II enzymes, including TrxR induction | S180 in mice | [89] | |

|

| ||||

|

MTT assay | Cytotoxic activity | NIH/3T3 cells | [90] |

| Lymphoproliferation—Con A, LPS, or PMA plus ionomycin | Inhibit the lymphoproliferation and induce a T-cell differentiation from CD4CD8 double positive cells to CD4 or CD8 single positive cells | Mice splenocytes | [74] | |

| Flow cytometry analysis | Capability to block the cell growth and stimulate a differentiation to mature cell | |||

| IgM-secreting B cells to SRBC | Decreased level of IgM to be due to the lower level of B-cell proliferation | Balb/c mice | ||

|

| ||||

|

ELISA | Inhibits proliferation and DNA synthesis | Caco-2 cells | [79] |

| Radioimmunoassay | Decreased intracellular cAMP levels | |||

| Flow cytometry analysis | Influence on the tumor cell cycle: G2-M period shortened, cell cycle lengthened, and cell proliferation inhibited | U14 cells | [92] | |

| cis-DDP-induced | Potentiated the inactivating effect of cis-DDP in all phases of the cell cycle | NHIK 3025 cells | [82] | |

| Trypan-blue assay | Anticancer activity | HL-60, A549, PC3, Du145, LN-CaP, A172, U251, SKMEL28, and A375 cells | [93, 94] | |

| Flow cytometry analysis | Inhibition and induced-differentiation on human osteogenic sarcoma cells | Human osteogenic sarcoma cells | [95] | |

| MTT assay | Cytotoxic activity | HepG2 cells | [97] | |

| Spectrophotometer | Higher antioxidant capacity | |||

| NRU assay | Cytotoxic activity | Mac Coy cells | [96] | |

| MTT assay | Antiviral activity | EHV-1 | [98] | |

|

| ||||

|

Trypan-blue assay |

Cytotoxic activity |

Rat hepatocytes | [54] |

| Waters chromatograph |

Decrease in cell viability, accompanied by losses of ATP, GSH; increase in GSSG, ROS, and MDA levels |

|||

|

| ||||

|

Indirect immunofluorescent method/EBV activation |

Inhibiting the generation of anions during tumor promotion |

Raji cells |

[100] |

| Trypan-blue exclusion assay | Cytotoxic activity | RPMI8226, U266, and IM-9 cells | [99] | |

| Flow cytometry | Induced caspases 3, 9, and 8 activities | RPMI8226 cells | ||

| Western blot analysis | TNF-α-induced apoptosis | |||

| ELISA | Downregulation of NF-κB activity | |||

| TNF-α-induced apoptosis | ||||

|

In vivo assay |

Anticancer effects with no toxic effects |

NOD/SCID mouse |

||

2. Phenylpropanoids

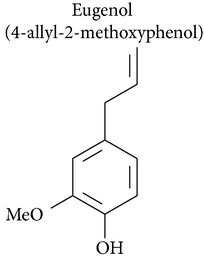

2.1. Eugenol

Eugenol is the active component of essential oil isolated from clove (Syzygium aromaticum) and has antimutagenic, antigenotoxic, and anti-inflammatory properties [10]. Eugenol also has cytotoxic activity. This drugs can induce cell death in several tumor and cell types: mast cells [11–13], breast adenocarcinoma [13], melanoma cells [14–16], leukemia [14, 17], colon carcinoma [18], cervical carcinoma [19–23], prostate cancer [24], submandibular gland adenocarcinoma [25], human dental pulp [26], murine peritoneal macrophages [27], androgen-insensitive prostate cancer, oral squamous carcinoma [17, 28], human submandibular gland carcinoma [29, 30], salivary gland [30], gingival fibroblasts [31–33], hepatoma [34], human dental pulp cells [35], human gingival fibroblasts, and epidermoid carcinoma cells derived from human submandibular gland [36, 37]. Furthermore, eugenol is neither carcinogenic nor mutagenic and is not cytotoxic in lymphocytes [14]. Isoeugenol was found to be more toxic than eugenol when the cytotoxicity of isoeugenol, bis-eugenol, and eugenol was tested in HSG (human submandibular gland adenocarcinoma) cell lines [25]. In this way, Atsumi and collaborators [37] compared the cytotoxicity of dehydrodiisoeugenol, alpha-di-isoeugenol, isoeugenol, eugenol, and bis-eugenol in a gland tumor cell line (HSG) and normal human gingival fibroblasts (HGF). Both the cytotoxic activity and the DNA synthesis inhibitory activity of these compounds against the salivary gland tumor cell line (HSG) and normal human gingival fibroblasts (HGF) were greatest in dehydrodiisoeugenol and alpha-di-isoeugenol, followed by isoeugenol, which showed greater activity than eugenol [37].

Synergistic effects have been demonstrated for eugenol with gemcitabine and fluorouracil, which potentiated its cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells (human cervical carcinoma) [19, 20, 38]. Eugenol also significantly decreased expression of Bcl-2, COX2, and IL-1b in the HeLa cell line [20]. Atsumi and collaborators [39] demonstrated that the effects of eugenol on ROS production were biphasic, with production enhanced at lower eugenol concentrations (5–10 μM) and inhibited at higher concentrations (500 μM). Suzuki and collaborators [40] demonstrated that eugenol stimulated production of superoxide (O2 −) free radicals in guinea pig neutrophils without lag time.

Eugenol halts cells in the replication phase, suggesting that cells stop to repair DNA damage and either reenter the cell cycle or, in cases of massive DNA damage, activate apoptosis. Melanoma cells treated with eugenol remain in the S phase and undergo apoptosis, and eugenol treatment upregulates numerous enzymes involved in the base excision repair pathway, including E2F family members [15].

In another study, eugenol at higher doses induced chromosomal aberrations, with significant increases (3.5%) in aberrant cells at a concentration of 2500 μM in V79 cells (Chinese hamster lung fibroblast). Eugenol was also assayed for genotoxic activity via inhibition of topoisomerase II and showed dose-dependent inhibition [41].

The chemopreventive potential of eugenol was also studied [10]. Using in vivo methods, Pal and collaborators [10] showed that eugenol inhibits skin carcinogenesis induced by dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) croton oil in mice, probably due to inhibition of proliferation-associated genes (c-Myc and H-ras) and antiapoptotic gene Bcl2, along with upregulation of proapoptotic genes Bax, p53, and active caspase-3 [10]. Kaur and collaborators [42] studied the chemopreventive effect of eugenol in DMBA/TPA-induced carcinogenesis in murine skin. They showed that topical application of eugenol resulted in a marked decline in hyperplasia, epidermal ODC activity, protein expression of iNOS and COX-2, and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, all of which are classical markers of inflammation and tumor promotion [42]. In addition, eugenol has been shown to produce antioxidant effects via free radical scavenging activity and reduction of ROS [22, 36, 43]. Atsumi and collaborators [36] showed that visible-light irradiation and elevation of the pH of the eugenol-containing medium resulted in significantly lower cell survival in HSG cultures in comparison with eugenol alone.

In vivo murine assays have also demonstrated the antitumor potential of eugenol. Treatment of female B6D2F1 mice bearing B16 melanoma allografts with 125 mg/kg of eugenol resulted in a small, but highly significant (P = 0.0057), 2.4-day tumor growth delay. Furthermore, the treated animals had no fatalities that were attributed to metastasis or tumor invasion, which is indicative of the ability of eugenol to suppress melanoma metastasis [15]. Jaganathan and collaborators [44] also demonstrated the antitumor potential of eugenol using an in vivo assay, in which a dose of 100 mg/kg caused 24.35% tumor growth inhibition and inhibited the growth of Ehrlich ascites by 28.88%. In contrast, Tangke Arung and collaborators [45] showed that 100 μg/mL eugenol inhibited melanin formation by more than 42% in the B16 melanoma cell line in vitro, with cytotoxicity in 5% of cells. At a higher concentration of 200 μg/mL 23% cytotoxicity was observed, which demonstrated that eugenol could be useful as a skin-whitening agent for the treatment of hyperpigmentation [45].

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that eugenol, when mixed with zinc oxide, has a restorative effect on dental erosion and demineralization [46]. Using human dental pulp cells (D824) it was observed that eugenol had a cytotoxic effect, with reduction of cell growth and inhibition of colony-forming cell [35]. D824 cells have the potential for metabolic activation, because they are a mixed-cell population composed of many types of cells, and thus the cytotoxic activity of eugenol could be attributable to eugenol metabolites. However, Marya and collaborators [46] showed a hemolytic effect of eugenol, which could be a possible side effect of this drug. In addition, Anpo and collaborators [35] showed that eugenol reduced growth and survival of human dental pulp cells, as well as collagen synthesis and bone sialoprotein (BSP) expression, which play a critical role in physiological and reparative dentinogenesis. Eugenol is a phenylpropanoid with promising antitumor drug profile. Further studies to elucidate the mechanisms that mediate the adverse effects of eugenol are necessary.

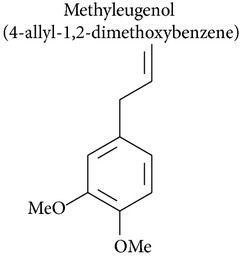

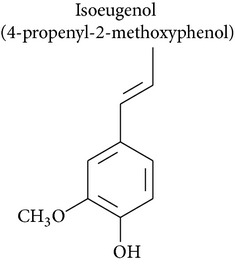

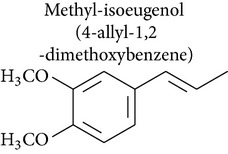

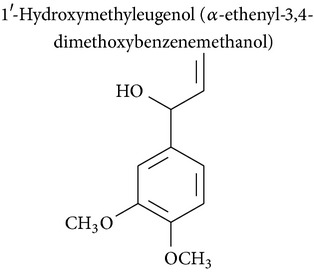

2.2. Methyleugenol, Isoeugenol, Methylisoeugenol, and 1′-Hydroxymethyleugenol

Methyleugenol is a substituted alkenylbenzene found in a variety of foods and essential oils. It is structurally similar to eugenol and found in many plant species [47]. Methyleugenol produced cytotoxic effects in rat and mouse hepatocytes [47, 48] and leukemia [48]. Methyleugenol also produced genotoxicity in mice [47] and in cultured cells [49] and caused neoplastic lesions in the livers of Fischer 344 rats and B6C3F1 mice [47].

Isoeugenol is a phenylpropanoid produced by plants. As a flavoring agent, isoeugenol is added to nonalcoholic drinks, baked foods, and chewing gums. In male F344/N rats, isoeugenol showed carcinogenic effects, causing increased incidence of rarely occurring thymoma and mammary gland carcinoma. There was no evidence of carcinogenic activity due to isoeugenol in female F344/N rats. However, there was clear evidence of carcinogenic activity due to isoeugenol in male B6C3F1 mice, including increased incidence of hepatocellular adenoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hepatocellular adenoma with carcinoma. Carcinogenic activity due to isoeugenol in female B6C3F1 mice was observed in the form of increased incidence of histiocytic sarcoma. Exposure to isoeugenol resulted in nonneoplastic lesions of the nose in male and female rats, of the kidney in female mice, and of the nose, forestomach, and glandular stomach in mice of both sexes [50]. However, methyleugenol is minimally cytotoxic for hepatocytes and leukemia cells compared to eugenol [48, 49]. The structural similarity of these substances with eugenol stimulates advances in pharmacological studies to explore their therapeutic potential in cancer treatment.

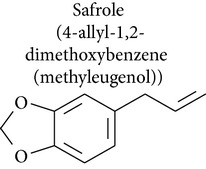

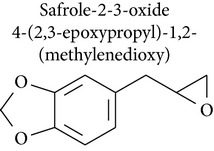

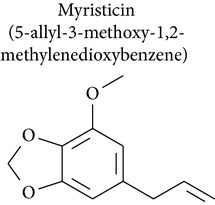

2.3. Safrole, Safrole-2′,3′-oxide, and Myristicin

Safrole is an important food-borne phytotoxin found in many natural products, such as oil of sassafras, anise, basil, nutmeg, and pepper. Safrole is cytotoxic against human tongue squamous carcinoma [51], primary human buccal mucosal fibroblasts [52], prostate cancer [53], rat hepatocytes [54], and leukemia [51] and shows genotoxic activity [55, 56].

Safrole induced apoptosis in human tongue squamous carcinoma SCC-4 cells by mitochondria- and caspase-dependent signaling pathways. Safrole-induced apoptosis was accompanied by upregulation of Bax and Bid and downregulation of Bcl-2, which increased the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2, resulting in cytochrome c release, increased Apaf-1 levels, and sequential activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 in a time-dependent manner [51]. In A549 human lung cancer cells, safrole activated caspases 3, 8, and 9 [57]. In rat hepatocytes cells, safrole induced cell death by loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and generation of oxygen radical species, which were assayed using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) [54].

Fan and collaborators [58] showed that safrole promoted the activities of macrophages and NK cells in BALB/c mice. While promoting macrophage phagocytosis, safrole increased abundance of cell markers such as CD11b and Mac-3. Additionally, NK cell cytotoxicity was remarkably suppressed in mice treated with safrole, as were levels of cell markers for T cells (CD3) and B cells (CD19). Safrole was also cytotoxic against primary human buccal mucosal fibroblasts (BMFs) [52]. Ni and collaborators [52] demonstrated that safrole increased NF-κB expression, which may have been involved in the pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis. NF-κB expression induced by safrole in fibroblasts may be mediated by ERK activation and the COX-2 signal transduction pathway.

A study by Chang and collaborators [53] investigated the effect of safrole on intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and viability of human PC3 prostate cancer cells. Cytosolic free Ca2+ levels ([Ca2+]i) were measured using fura-2 as a probe. Safrole increased [Ca2+]i by causing Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum in a phospholipase C- and protein kinase C-independent manner, which decreased cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner. In HL-60 leukemia cells, safrole promoted the expression of glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), growth arrest- and DNA damage-inducible gene 153 (GADD153), and activating transcription factor 6α (ATF-6α) [51]. In the unscheduled DNA synthesis (UDS) assay described by Howes and collaborators [55], safrole exhibited genotoxic activity in freshly isolated rat hepatocyte primary cultures.

Safrole-2′,3′-oxide (SAFO) is a reactive electrophilic metabolite of safrole. SAFO is the most mutagenic metabolite of safrole that has been tested in the Ames test, but data on the genotoxicity of SAFO in mammalian systems is scarce. SAFO induced cytotoxicity, DNA strand breakage, and micronuclei formation in human cells in vitro and in mice [56]. In addition, safrole produced mutagenicity in Salmonella TA 98 and TA 100 in the Ames test [59].

Myristicin (1-allyl-3,4-methylenedioxy-5-methoxybenzene) is an active constituent of nutmeg, parsley, and carrot. A study by Lee and collaborators [60] investigated the cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of myristicin on human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. Apoptosis triggered by myristicin was caused by cleavage of PARP, which was accompanied by accumulation of cytochrome c and activation of caspase-3. These results suggested that myristicin induced cytotoxicity in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells by an apoptotic mechanism [60].

Ahmad and collaborators [61] investigated the effect of myristicin on activity of glutathione S-transferase (GST) and NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase (QR) in four mouse strains. The authors showed that activity of GST and QR was significantly increased in the livers of all four mouse strains, GST activity was increased in the intestine of three out of four strains, and QR activity was significantly increased in the lungs and stomachs of three out of four stains. Thus myristicin, which is found in a wide variety of herbs and vegetables, shows strong potential as an effective chemoprotective agent against cancer.

Safrole, safrole-2′,3′-oxide, and myristicin are bioactive substances in antitumor models that can be used as starting materials for the preparation of derivatives with improved pharmacological profile.

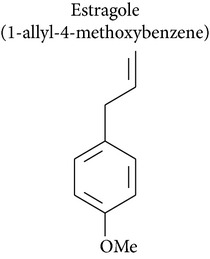

2.4. Estragole, Anethole, and trans-Anethole Oxide

Estragole has been isolated from essential oils of Artemisia dracunculus and Leonotis ocymifolia. Howes and collaborators [55] demonstrated the genotoxic activity of estragole via UDS assay, in which estragole induced dose-dependent increases in UDS up to 2.7 times that of the control in rat hepatocytes in primary culture.

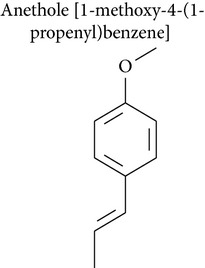

Anethole (1-methoxy-4-(1-propenyl)benzene) occurs naturally as a major component of essential oils from fennel and star anise and is also present in numerous plants such as dill, basil, and tarragon [62]. Anethole had a cytotoxic effect on fibrosarcoma tumor [63], breast cancer [63], hepatocytes [55, 64], cervical carcinoma [21, 23], and Ehrlich ascites tumor [65], as well as an anticarcinogenic effect and a lack of clastogenic potential [65].

Chainy and collaborators [66] reported that anethole reduced apoptosis by inhibiting induction of NF-κB, activator protein 1 (AP-1), c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKK) by tumor necrosis factor (TNF). Choo and collaborators investigated the antimetastatic activity of anethole [63] and showed that anethole inhibited proliferation, adhesion, and invasion of highly metastatic human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells. Anethole also inhibited the activity of metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) and increased the activity of MMP inhibitor TIMP-1 [63]. Nakagawa and Suzuki [62] showed that anethole induced a concentration- and time-dependent loss of cell viability in isolated rat hepatocytes, which was followed by decreases in intracellular levels of ATP and total adenine nucleotide pools. Howes and collaborators [55] demonstrated that anethole did not induce unscheduled DNA synthesis (UDS) in rat hepatocytes in primary culture. In Ehrlich ascites tumor-bearing mice,anethole increased survival time and reduced tumor weight, tumor volume, and body weight [65].

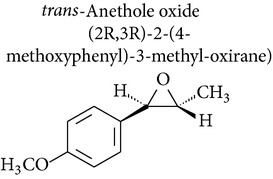

Anethole is metabolized through 3 pathways: O-demethylation, ω-hydroxylation followed by side chain oxidation, and epoxidation of the 1,2-double bond. The cytotoxicity of trans-anethole oxide in rat hepatocytes has been shown to be due to its metabolism to epoxide [67]. In addition, trans-anethole oxide produced a positive result in the Salmonella mutation assay and induced tumors in mice. These results suggest that epoxidation of the side chain of anethole in vivo could be a carcinogenic metabolic mechanism. Kim and collaborators [67] found that trans-anethole oxide is more toxic to animals than trans-anethole and was mutagenic in point mutation and frameshift mutation Ames test models. trans-Anethole did not induce hepatomas in male B6C3F1 mice, but the highest dose of trans-anethole oxide tested (0.5 μmol/g) significantly increased the incidence of hepatomas.

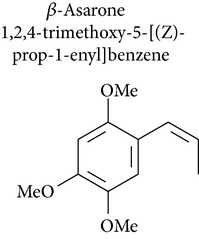

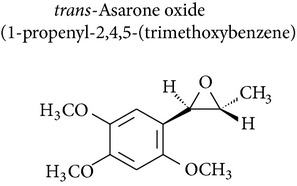

2.5. Asaraldehyde, β-Asarone, and trans-Asarone Oxide

Acorus gramineus (Araceae), which is distributed throughout Korea, Japan, and China, has been used in Korean traditional medicine for improvement of learning and memory, sedation, and analgesia [68]. Several pharmacologically active compounds, such as β-asarone, α-asarone, and phenylpropenes, have been reported from this rhizome [69]. Park and collaborators [70] investigated asarone and asaraldehyde and showed minimal cytotoxicity (IC50 < 30 μM) in the SRB assay using 4 human tumor cell lines: A549 (non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma), SK-OV-3 (ovarian cancer cell), SK-MEL-2 (skin melanoma), and HCT15 (colon cancer cell). trans-Asarone oxide, prepared from trans-asarone and dimethyldioxirane, induced hepatomas in B6C3F1 mice and skin papillomas in CD-1 mice and was mutagenic for Salmonella strains [67].

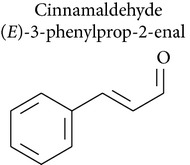

2.6. Cinnamaldehyde, 2′-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde, and Cinnamic Acid

Cinnamaldehyde is a bioactive compound isolated from the stem bark of Cinnamomum cassia and has been widely used in folk medicine for its anticancer [71], antibacterial [72], antimutagenic [73], and immunomodulatory effects [74], as well as to remedy other diseases [75]. The cytotoxic activity of cinnamaldehyde has been confirmed in melanoma [76, 77], the colon [76, 78, 79], breast cancer [78], hepatic tumor [80, 81], leukemia [71, 82, 83], cervical carcinoma [76, 83] the lung, the ovary, the central nervous system [76], lymphoma, mouse leukemia [76, 84], mouse lung carcinoma [71], lymphocytes [74], hepatocytes [85], embryo cells [86], and larynx carcinoma [87]. Its genotoxicity has been confirmed in vitro [87]. Cinnamaldehyde also had genotoxic effects against SA7-transformed Syrian hamster embryo cells [86].

Ng and Wu [80] showed that cinnamaldehyde induced lipid peroxidation in hepatocytes isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats with glutathione depletion. Adding NADH generators, for example, xylitol, prevented cytotoxicity induced by cinnamaldehyde, but decreasing mitochondrial NAD+ with rotenone markedly increased cinnamaldehyde cytotoxicity. The authors showed that cinnamaldehyde-induced cytotoxicity and inhibition of mitochondrial respiration were markedly increased by ALDH inhibitors and in particular by cyanamide [80].

Chew and collaborators [78] used flow cytometric analysis to show that 80 μM of cinnamaldehyde caused cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase in HCT 116 cells and induced cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP. It has also been proposed that cinnamaldehyde induced apoptosis by ROS release with TrxR-inhibitory and Nrf2-inducing properties [78]. Ka and collaborators [71] demonstrated that cinnamaldehyde induced ROS-mediated mitochondrial permeability and cytochrome c release in human leukemia cells (HL-60).

Using hepatoma cells, Wu and collaborators [81] demonstrated that cinnamaldehyde upregulated Bax protein, downregulated Bcl-2 and Mcl-1, and caused Bid to cleave upon the activation of caspase-8. These events consequently led to cell death. JNK, p38, and ERK were activated and phosphorylated after cinnamaldehyde treatment in a time-dependent manner, which suggested that apoptosis was mediated by activation of proapoptotic Bcl-2 family (Bax and Bid) proteins and MAPK pathways [81]. Cinnamaldehyde can also activate TRPA1 expression in melanoma cells [77].

Cinnamaldehyde caused a time-dependent increase in CD95 (APO-1/CD95) protein expression in HepG2 cells (human hepatoma), while also downregulating antiapoptotic proteins (Bcl-XL) and upregulating proapoptotic (Bax) proteins in a time-dependent manner [80]. Preincubation of HepG2 cells with cinnamaldehyde effectively inhibited the expression of Bax, p53, and CD95, as well as the cleavage of PARP. This pretreatment also prevented downregulation of Bcl-XL [80]. Using the HepG2 and Hep3B human hepatoma cancer cell lines, Chuang and colleagues [88] demonstrated that cinnamaldehyde had a potent inhibitory effect against human hepatoma cell growth. They observed that the JAK2-STAT3/STAT5 pathway might be an important target of cinnamaldehyde. Cinnamaldehyde also altered apoptotic signaling. Cinnamaldehyde significantly decreased protein levels of cyclin D1 and proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) but increased the protein levels of p27Kip1 and p21Waf1/Cip1 [86]. In an assay of thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) action, cinnamaldehyde showed a TrxR inactivation effect that could contribute to its cytotoxicity [89]. Furthermore, cinnamaldehyde had an antitumor effect in Sarcoma 180-bearing BALB/c mice and a protective effect on immune function [89].

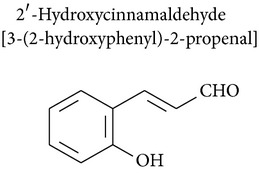

2′-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde, a cinnamaldehyde derivative, was studied for its immunomodulatory effects. The chemopreventive effects of cinnamaldehyde derivatives were demonstrated on hepatocellular carcinoma formation in H-ras12V transgenic mice, where they probably produced a long-term immunostimulating effect on T cells, because immune cell infiltration into hepatic tissues was increased [90].

2′-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde has immunomodulatory effects in vivo, but in vitro studies showed that secreted IgM level was depressed in the culture supernatants of splenocytes. Decreased IgM produced by cinnamaldehyde treatment in vitro appeared to be due to lower levels of B-cell proliferation, rather than direct inhibition of IgM production [74]. Koh and collaborators [74] also demonstrated that cinnamaldehyde induced T-cell differentiation from CD4CD8 double positive cells to CD4 or CD8 single positive cells.

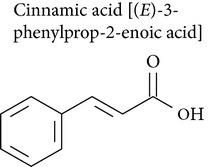

Cinnamic acid occurs throughout the plant kingdom and particularly in flavor compositions and products containing cinnamon oil [91]. Cinnamic acid inhibited proliferation of uterocervical carcinoma [92], leukemia [93], colon adenocarcinoma [79], glioblastoma, melanoma, prostate, lung carcinoma [94], osteogenic sarcoma [95] cells, Mac Coy cells [96], Hep G2 cells [97], and kidney epithelial (VERO) cells [98].

Cinnamic acid had an inhibitory effect on uterocervical carcinoma (U14) cells in mice, causing tumor cell apoptosis [92]. In vitro assay of U14 cells demonstrated a shortened G2-M period, lengthened cell cycle, and inhibited cell proliferation, which supported the conclusion that cinnamic acid influenced tumor cell cycle [92].

Ekmekcioglu and collaborators [79] showed that cinnamic acid inhibited proliferation and DNA synthesis of Caco-2 (human colon) cells. Treatment with cinnamic acid modulated the Caco-2 cell phenotype by dose-dependently stimulating sucrase and aminopeptidase N activity, while inhibiting alkaline phosphatase activity. In melanoma cells cinnamic acid induced cell differentiation with morphological changes and increased melanin production. Cinnamic acid reduced the invasive capacity of melanoma cells and modulated expression of genes implicated in tumor metastasis (collagenase type IV and tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 2) and immunogenicity (HLA-A3, class-I major histocompatibility antigen) [94].

Using in vivo and in vitro assays, Zhang and collaborators (2010) [92] showed that cinnamic acid influenced the cell cycle of uterocervical carcinoma cells (U14); the G2-M period was shortened, cell cycle was lengthened, and cell proliferation was inhibited. Cinnamic acid also induced differentiation of human osteogenic sarcoma cells and caused a higher percentage of cells in S phase [95].

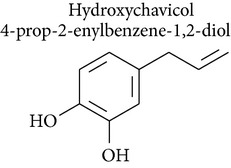

2.7. Hydroxychavicol and 1′-Acetoxychavicol Acetate

Hydroxychavicol (1-allyl-3,4-dihydroxybenzene) is a major component in Piper betle leaf, which is used for betel quid chewing in Asia, and is also a major metabolite of safrole, which is the main component of sassafras oil, in rats and humans. A study by Nakagawa and collaborators [54] demonstrated the biotransformation and cytotoxic effects of hydroxychavicol in freshly-isolated rat hepatocytes. In hepatocytes pretreated with diethyl maleate or salicylamide, hydroxychavicol-induced cytotoxicity was enhanced and was accompanied by a decrease in the formation of conjugates and inhibition of hydroxychavicol loss.

Other studies indicate that mitochondria are the target organelles for hydroxychavicol, which induces cytotoxicity through mitochondrial failure related to mitochondrial membrane potential at an early stage, and lipid peroxidation through oxidative stress at a later stage. Furthermore, the onset of cytotoxicity depends on the initial and residual concentrations of hydroxychavicol, rather than its metabolites.

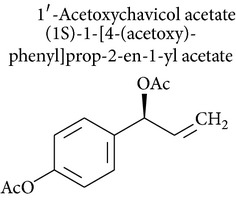

1′-Acetoxychavicol acetate is obtained from the rhizomes of Languas galanga (Zingiberaceae), a traditional condiment in Thailand. Recent studies have revealed that 1′-acetoxychavicol acetate has potent chemopreventive effects against rat oral carcinomas and inhibits chemically induced tumor formation and cellular growth of cancer cells. 1′-Acetoxychavicol acetate inhibited NF-κB and induced apoptosis of myeloma cells in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, 1′-acetoxychavicol acetate is a novel NF-κB inhibitor and represents a new therapy for the treatment of multiple myeloma patients [99]. The isolation and identification of 1′-acetoxychavicol acetate, an inhibitor of xanthine oxidase, may induce antitumor activity by inhibiting generation of anions during tumor promotion [100] (Figure 1).

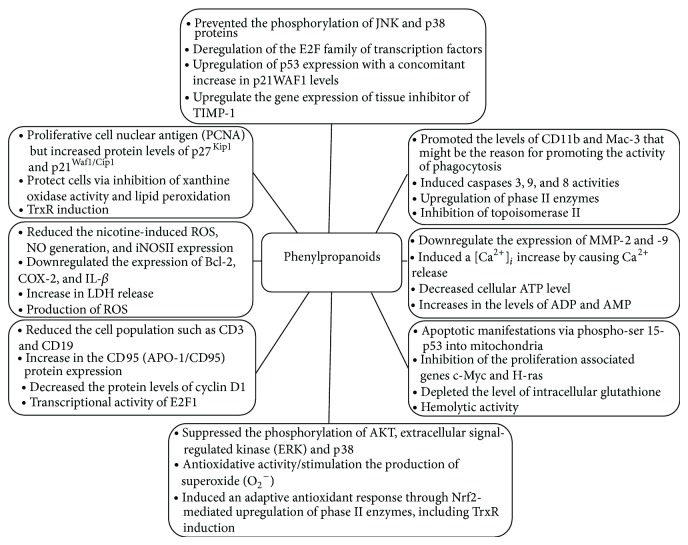

Figure 1.

Possible mechanisms of action from phenylpropanoids antitumoral activity.

3. Conclusions

The studies presented in this review reveal the anticancer therapeutic potential of bioactive constituents found in essential oils and medicinal plants, the phenylpropanoids. The research on the clinical studies of these natural products is required to the development of new drug candidates with applications in the therapy of cancer.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Abbreviations

Cell Lines

- 3LL:

Mouse lung carcinoma

- A172:

Human malignant glioblastoma

- A375:

Melanoma

- A549:

Lung adenocarcinoma

- BMFs:

Primary human buccal mucosal fibroblasts

- Caco-2:

Human colon adenocarcinoma

- CD11b:

Monocytes

- CD19:

B cells

- CD3:

T cells

- CEM:

Acute T lymphoblastoid leukemia

- CN-Mel:

Melanoma

- DU-145:

Androgen-insensitive prostate cancer

- F344:

Hepatocytes

- G361:

Melanoma

- GR-Mel:

Melanoma

- HCT-15:

Colon tumor

- HeLa:

Human cervical carcinoma

- Hep3B:

Human hepatoma cancer

- HepG2:

Human hepatoma

- HGF:

Human gingival fibroblasts

- HL-60:

Human promyelocytic leukemia

- HSC-3:

Human oral cancer cells

- HSG:

Human submandibular gland carcinoma

- HT-1080:

Human fibrosarcoma tumor

- K-562:

Human chronic myelogenous leukemia

- KB:

Oral squamous carcinoma

- L-1210:

Mouse leukemia

- LCM-Mel:

Melanoma

- LCP-Mel:

Melanoma

- LN-CaP:

Prostate cancer

- Mac-3:

Macrophages

- MCF-7 gem:

Human breast adenocarcinoma (resistant to gemcitabine)

- MCF-7:

Human breast adenocarcinoma

- ML-1:

Human myeloblastic leukemia

- NHIK 3025:

Human cervical carcinoma

- P388:

Mouse leukemia

- P-815:

Murine mastocytoma

- PC-3:

Human prostate cancer

- PLC/PRF/5:

Human hepatoma

- PNP-Mel:

Melanoma

- Raw 264.7:

Mouse leukemic monocyte macrophage

- S180:

Sarcoma 180

- SbCl2:

Primary melanoma

- SCC-4:

Tongue squamous carcinoma

- SK-Mel-19:

Melanoma

- SK-MEL-2:

Skin melanoma

- SK-MEL-23:

Melanoma

- SK-MEL-28:

Melanoma

- SK-N-SH:

Neuroblastoma

- SK-OV-3:

Ovarian cancer

- SNU-C5:

Human colon cancer

- U14:

Uterocervical carcinoma

- U251:

Human malignant glioblastoma

- U-937:

Human histiocytic lymphoma

- uPA:

Urokinase plasminogen activator

- WM1205Lu:

Metastatic melanoma

- WM266-4:

Melanoma

- WM3211:

Primary radial growth phase melanoma

- WM98-1:

Primary vertical growth phase melanoma

- XF-498:

Central nerve system.

Tests

- AFC:

Antibody forming cell

- ALDH:

Aldehyde dehydrogenase

- Ames test:

Biological assay to assess the mutagenic potential of chemical compounds

- Boyden-chamber assay:

Evaluation of tumor cell invasion in vitro

- c-AMP:

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CAs:

Chromosomal aberrations

- CCK-8:

Cell Counting Kit-8, a sensitive colorimetric assay

- CDFHDA:

5-(and -6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- Comet assay:

Single-cell gel electrophoresis

- Con A:

Concanavalin

- DAPI:

4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DCFH:

Dichlorofluorescein

- DEM:

Diethyl maleate

- DMBA:

7,12-Dimethylbenz[a]anthracene

- DPPH:

1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl

- DTNB:

5,5′-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- EBV:

Epstein-Barr virus

- EHV-1:

Herpes virus 1

- ESR:

Electron spin resonance spectroscopy

- GSSG:

Oxidized glutathione

- GST:

Glutathione S-transferase

- LDH:

Lactate dehydrogenase

- LPS:

Lipopolysaccharide

- MDA:

Malondialdehyde

- MMP:

Matrix metalloproteinase

- MTT:

[3(4,5-Dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide]

- NF-κB:

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- NRU assay:

Neutral red uptake

- p21WAF1:

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1A

- PARP:

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PBS:

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR:

Polymerase chain reaction

- PMA:

Phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate plus ionomycin

- QR:

Quinone oxidoreductase

- SRB:

Sulforhodamine B

- SRBC:

Sheep red blood cells

- TBA:

Test in the aqueous phase

- TBARS:

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

- TUNEL:

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling

- UDS assay:

Unscheduled DNA synthesis

- V-FITC assay:

Apoptosis detection kit

- WST:

Tetrazolium salt

- XTT:

2,3-Bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Sousa D. P. Analgesic-like activity of essential oils constituents. Molecules. 2011;16(3):2233–2252. doi: 10.3390/molecules16032233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Almeida R. N., de Fátima Agra M., Maior F. N. S., de Sousa D. P. Essential oils and their constituents: anticonvulsant activity. Molecules. 2011;16(3):2726–2742. doi: 10.3390/molecules16032726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Da Silveira E Sá R. D. C., Andrade L. N., De Oliveira R. D. R. B., De Sousa D. P. A review on anti-inflammatory activity of phenylpropanoids found in essential oils. Molecules. 2014;19(2):1459–1480. doi: 10.3390/molecules19021459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su Y.-C., Ho C.-L. Composition, in-vitro anticancer, and antimicrobial activities of the leaf essential oil of Machilus mushaensis from Taiwan. Natural Product Communications. 2013;8(2):273–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manjamalai A., Grace V. M. B. The chemotherapeutic effect of essential oil of Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour) on lung metastasis developed by B16F-10 cell line in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Investigation. 2013;31(1):74–82. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2012.749268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashour H. M. Antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer activities of volatile oils and extracts from stems, leaves, and flowers of Eucalyptus sideroxylon and Eucalyptus torquata . Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2008;7(3):399–403. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.3.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medina-Holguín A. L., Omar Holguín F., Micheletto S., Goehle S., Simon J. A., O'Connell M. A. Chemotypic variation of essential oils in the medicinal plant, Anemopsis californica. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(4):919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kathirvel P., Ravi S. Chemical composition of the essential oil from basil (Ocimum basilicum Linn.) and its in vitro cytotoxicity against HeLa and HEp-2 human cancer cell lines and NIH 3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Natural Product Research. 2012;26(12):1112–1118. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2010.545357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal D., Banerjee S., Mukherjee S., Roy A., Panda C. K., Das S. Eugenol restricts DMBA croton oil induced skin carcinogenesis in mice: downregulation of c-Myc and H-ras, and activation of p53 dependent apoptotic pathway. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2010;59:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park B. S., Song Y. S., Yee S.-B., et al. Phospho-ser 15-p53 translocates into mitochondria and interacts with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in eugenol-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2005;10(1):193–200. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-6074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaganathan S. K., Supriyanto E. Antiproliferative and molecular mechanism of eugenol-induced apoptosis in cancer cells. Molecules. 2012;17(6):6290–6304. doi: 10.3390/molecules17066305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaafari A., Tilaoui M., Mouse H. A., et al. Comparative study of the antitumor effect of natural monoterpenes: relationship to cell cycle analysis. Brazilian Journal of Pharmacognosy. 2012;22(3):534–540. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2012005000021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satooka H., Kubo I. Effects of eugenol on murine B16-F10 melanoma cells. Proceedings of the 238th ACS National Meeting; 2009; Washington, DC, USA. pp. 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosh R., Nadiminty N., Fitzpatrick J. E., Alworth W. L., Slaga T. J., Kumar A. P. Eugenol causes melanoma growth suppression through inhibition of E2F1 transcriptional activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(7):5812–5819. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pisano M., Pagnan G., Loi M., et al. Antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activity of eugenol-related biphenyls on malignant melanoma cells. Molecular Cancer. 2007;6, article 8 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujisawa S., Atsumi T., Satoh K., et al. Radical generation, radical-scavenging activity, and cytotoxicity of eugenol-related compounds. In Vitro and Molecular Toxicology. 2000;13(4):269–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slameňová D., Horváthová E., Wsólová L., Šramková M., Navarová J. Investigation of anti-oxidative, cytotoxic, DNA-damaging and DNA-protective effects of plant volatiles eugenol and borneol in human-derived HepG2, Caco-2 and VH10 cell lines. Mutation Research—Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis. 2009;677(1-2):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemaiswarya S., Doble M. Combination of phenylpropanoids with 5-fluorouracil as anti-cancer agents against human cervical cancer (HeLa) cell line. Phytomedicine. 2013;20(2):151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain A., Brahmbhatt K., Priyani A., Ahmed M., Rizvi T. A., Sharma C. Eugenol enhances the chemotherapeutic potential of gemcitabine and induces anticarcinogenic and anti-inflammatory activity in human cervical cancer cells. Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2011;26(5):519–527. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2010.0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoichev S., Zolotovich G., Nachev C., Silyanovska K. Cytotoxic effect of phenols, phenol ethers, furan derivatives, and oxides isolated from essential oils. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie Bulgare des Sciences. 1967;20:1341–1344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang P., Zhang E., Xiao M., Chen C., Xu W. Enhanced chemical and biological activities of a newly biosynthesized eugenol glycoconjugate, eugenol α-d-glucopyranoside. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2013;97(3):1043–1050. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zolotovich G., Silyanovska K., Stoichev S., Nachev C. Cytotoxic effect of essential oils and their individual components. II. Oxygen-containing compounds excluding alcohols. Parfuemerie und Kosmetik. 1969;50:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh R., Ganapathy M., Alworth W. L., Chan D. C., Kumar A. P. Combination of 2-methoxyestradiol (2-ME2) and eugenol for apoptosis induction synergistically in androgen independent prostate cancer cells. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2009;113(1-2):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujisawa S., Atsumi T., Ishihara M., Kadoma Y. Cytotoxicity, ROS-generation activity and radical-scavenging activity of curcumin and related compounds. Anticancer Research. 2004;24(2):563–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awuti G., Tuerxun G., Tuerxun A., Tuerxun J. Cytotoxicity of two different pulp capping materials on human dental pulp cells in vitro . Journal of Oral Science Research. 2012;28(5):485–487. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahapatra S. K., Bhattacharjee S., Chakraborty S. P., Majumdar S., Roy S. Alteration of immune functions and Th1/Th2 cytokine balance in nicotine-induced murine macrophages: immunomodulatory role of eugenol and N-acetylcysteine. International Immunopharmacology. 2011;11(4):485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carrasco A. H., Espinoza C. L., Cardile V., et al. Eugenol and its synthetic analogues inhibit cell growth of human cancer cells (Part I) Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society. 2008;19(3):543–548. doi: 10.1590/S0103-50532008000300024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujisawa S., Atsumi T., Kadoma Y., Sakagami H. Antioxidant and prooxidant action of eugenol-related compounds and their cytotoxicity. Toxicology. 2002;177(1):39–54. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satoh K., Ida Y., Sakagami H., Tanaka T., Fujisawa S. Effect of antioxidants on radical intensity and cytotoxic activity of eugenol. Anticancer Research. 1998;18(3 A):1549–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kashiwagi Y. A cytotoxic study of eugenol and its ortho dimer (bis-eugenol) Meikai Daigaku Shigaku Zasshi. 2001;29:176–188. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerosa R., Borin M., Menegazzi G., Puttini M., Cavalleri G. In vitro evaluation of the cytotoxicity of pure eugenol. Journal of Endodontics. 1996;22(10):532–534. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(96)80012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeng J. H., Hahn L. J., Lu F. J., Wang Y. J., Kuo M. Y. Eugenol triggers different pathobiological effects on human oral mucosal fibroblasts. Journal of Dental Research. 1994;73(5):1050–1055. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Babich H., Stern A., Borenfreund E. Eugenol cytotoxicity evaluated with continuous cell lines. Toxicology in Vitro. 1993;7(2):105–109. doi: 10.1016/0887-2333(93)90119-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anpo M., Shirayama K., Tsutsui T. Cytotoxic effect of eugenol on the expression of molecular markers related to the osteogenic differentiation of human dental pulp cells. Odontology. 2011;99(2):188–192. doi: 10.1007/s10266-011-0009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atsumi T., Iwakura I., Fujisawa S., Ueha T. Reactive oxygen species generation and photo-cytotoxicity of eugenol in solutions of various pH. Biomaterials. 2001;22(12):1459–1466. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atsumi T., Fujisawa S., Satoh K., et al. Cytotoxicity and radical intensity of eugenol, isoeugenol or related dimers. Anticancer Research. 2000;20(4):2519–2524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hussain A., Priyani A., Sadrieh L., Brahmbhatt K., Ahmed M., Sharma C. Concurrent sulforaphane and eugenol induces differential effects on human cervical cancer cells. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2012;11(2):154–165. doi: 10.1177/1534735411400313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atsumi T., Fujisawa S., Tonosaki K. A comparative study of the antioxidant/prooxidant activities of eugenol and isoeugenol with various concentrations and oxidation conditions. Toxicology in Vitro. 2005;19(8):1025–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki Y., Sugiyama K., Furuta H. Eugenol-mediated superoxide generation and cytotoxicity in guinea pig neutrophils. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 1985;39(3):381–386. doi: 10.1254/jjp.39.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maralhas A., Monteiro A., Martins C., et al. Genotoxicity and endoreduplication inducing activity of the food flavouring eugenol. Mutagenesis. 2006;21(3):199–204. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gel017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaur G., Athar M., Sarwar Alam M. Eugenol precludes cutaneous chemical carcinogenesis in mouse by preventing oxidative stress and inflammation and by inducing apoptosis. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2010;49(3):290–301. doi: 10.1002/mc.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogiwara T., Satoh K., Kadoma Y., et al. Radical scavenging activity and cytotoxicity of ferulic acid. Anticancer Research. 2002;22(5):2711–2717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaganathan S. K., Mondhe D., Wani Z. A., Pal H. C., Mandal M. Effect of honey and eugenol on ehrlich ascites and solid carcinoma. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2010;2010:5. doi: 10.1155/2010/989163.989163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tangke Arung E., Matsubara E., Wijaya Kusuma I., Sukaton E., Shimizu K., Kondo R. Inhibitory components from the buds of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) on melanin formation in B16 melanoma cells. Fitoterapia. 2011;82(2):198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marya C. M., Satija G., Avinash J., Nagpal R., Kapoor R., Ahmad A. In vitro inhibitory effect of clove essential oil and its two active principles on tooth decalcification by apple juice. International Journal of Dentistry. 2012;2012:6. doi: 10.1155/2012/759618.759618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burkey J. L., Sauer J.-M., McQueen C. A., Sipes I. G. Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of methyleugenol and related congeners—a mechanism of activation for methyleugenol. Mutation Research: Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2000;453(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(00)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee K.-T., Choi J., Park J.-H., Jung W.-T., Jung H.-J., Park H.-J. Composition of the essential oil of Chrysanthemum sibiricum, and cytotoxic properties. Natural Product Sciences. 2002;8(4):133–136. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maria Groh I. A., Cartus A. T., Vallicotti S., et al. Genotoxic potential of methyleugenol and selected methyleugenol metabolites in cultured Chinese hamster V79 cells. Food and Function. 2012;3(4):428–436. doi: 10.1039/c2fo10221h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Toxicology Program. Toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of isoeugenol (CAS No. 97-54-1) in F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice (gavage studies) National Toxicology Program Technical Report Series. 2010;551:1–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu F.-S., Huang A.-C., Yang J.-S., et al. Safrole induces cell death in human tongue squamous cancer SCC-4 cells through mitochondria-dependent caspase activation cascade apoptotic signaling pathways. Environmental Toxicology. 2012;27(7):433–444. doi: 10.1002/tox.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ni W.-F., Tsai C.-H., Yang S.-F., Chang Y.-C. Elevated expression of NF-κB in oral submucous fibrosis—evidence for NF-κB induction by safrole in human buccal mucosal fibroblasts. Oral Oncology. 2007;43(6):557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang H. C., Cheng H. H., Huang C. J., et al. Safrole-induced Ca2+ mobilization and cytotoxicity in human PC3 prostate cancer cells. Journal of Receptors and Signal Transduction. 2006;26(3):199–212. doi: 10.1080/10799890600662595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakagawa Y., Suzuki T., Nakajima K., Ishii H., Ogata A. Biotransformation and cytotoxic effects of hydroxychavicol, an intermediate of safrole metabolism, in isolated rat hepatocytes. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2009;180(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Howes A. J., Chan V. S. W., Caldwell J. Structure-specificity of the genotoxicity of some naturally occurring alkenylbenzenes determined by the unscheduled DNA synthesis assay in rat hepatocytes. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1990;28(8):537–542. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(90)90152-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiang S.-Y., Lee P.-Y., Lai M.-T., et al. Safrole-2′,3′-oxide induces cytotoxic and genotoxic effects in HepG2 cells and in mice. Mutation Research—Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis. 2011;726(2):234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Du A., Zhao B., Yin D., Zhang S., Miao J. Safrole oxide induces apoptosis by activating caspase-3, -8, and -9 in A549 human lung cancer cells. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2006;16(1):81–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fan M.-J., Lin S.-Y., Yu C.-C., et al. Safrole-modulated immune response is mediated through enhancing the CD11b surface marker and stimulating the phagocytosis by macrophages in BALB/c mice. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 2012;31(9):898–904. doi: 10.1177/0960327111421944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farag S. E. A., Abo-Zeid M. A. A. Mutagenicity and degradation of natural carcinogenic compound-safrole in spices under different processing methods. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1996;17:149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee B. K., Kim J. H., Jung J. W., et al. Myristicin-induced neurotoxicity in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. Toxicology Letters. 2005;157(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahmad H., Valdivia V., Cadena A., et al. Myristicin: inducer of phase-II drug metabolizing enzymes and prospective chemoprotective agent against cancer. Acta Horticulturae. 2009;841:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakagawa Y., Suzuki T. Cytotoxic and xenoestrogenic effects via biotransformation of trans-anethole on isolated rat hepatocytes and cultured MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2003;66(1):63–73. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Choo E. J., Rhee Y.-H., Jeong S.-J., et al. Anethole exerts antimetatstaic activity via inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase 2/9 and AKT/mitogen-activated kinase/nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathways. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2011;34(1):41–46. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marshall A. D., Caldwell J. Influence of modulators of epoxide metabolism on the cytotoxicity of trans-anethole in freshly isolated rat hepatocytes. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1992;30(6):467–473. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(92)90097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Al-Harbi M. M., Qureshi S., Raza M., Ahmed M. M., Giangreco A. B., Shah A. H. Influence of anethole treatment on the tumour induced by Ehrlich ascites carcinoma cells in paw of Swiss albino mice. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 1995;4(4):307–318. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199508000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chainy G. B. N., Manna S. K., Chaturvedi M. M., Aggarwal B. B. Anethole blocks both early and late cellular responses transduced by tumor necrosis factor: effect on NF-κB, AP-1, JNK, MAPKK and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2000;19(25):2943–2950. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim S. G., Liem A., Stewart B. C., Miller J. A. New studies on trans-anethole oxide and trans-asarone oxide. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20(7):1303–1307. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.7.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liao J.-F., Huang S.-Y., Jan Y.-M., Yu L.-L., Chen C.-F. Central inhibitory effects of water extract of Acori graminei rhizoma in mice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1998;61(3):185–193. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(98)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Greca M. D., Monaco P., Previtera L., Aliotta G., Pinto G., Pollio A. Allelochemical activity of phenylpropanes from Acorus gramineus . Phytochemistry. 1989;28(9):2319–2321. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)97975-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park C. H., Kim K. H., Lee I. K., et al. Phenolic constituents of Acorus gramineus . Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2011;34(8):1289–1296. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ka H., Park H.-J., Jung H.-J., et al. Cinnamaldehyde induces apoptosis by ROS-mediated mitochondrial permeability transition in human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells. Cancer Letters. 2003;196(2):143–152. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang S.-T., Chen P.-F., Chang S.-C. Antibacterial activity of leaf essential oils and their constituents from Cinnamomum osmophloeum . Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2001;77(1):123–127. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shaughnessy D. T., Setzer R. W., DeMarini D. M. The antimutagenic effect of vanillin and cinnamaldehyde on spontaneous mutation in Salmonella TA104 is due to a reduction in mutations at GC but not AT sites. Mutation Research—Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2001;480-481:55–69. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(01)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koh W. S., Yoon S. Y., Kwon B. M., Jeong T. C., Nam K. S., Han M. Y. Cinnamaldehyde inhibits lymphocyte proliferation and modulates T-cell differentiation. International Journal of Immunopharmacology. 1998;20(11):643–660. doi: 10.1016/S0192-0561(98)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perry L. M. Medicinal Plants of East and Southeast Asia: Attributed Properties and Uses. Cambridge, Mass, USA: The MIT Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee H.-S., Kim S.-Y., Lee C.-H., Ahn Y.-J. Cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of Cinnamomum cassia bark-derived materials. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2004;14(6):1176–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oehler B., Scholze A., Schaefer M., Hill K. TRPA1 is functionally expressed in melanoma cells but is not critical for impaired proliferation caused by allyl isothiocyanate or cinnamaldehyde. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 2012;385(6):555–563. doi: 10.1007/s00210-012-0747-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chew E.-H., Nagle A. A., Zhang Y., et al. Cinnamaldehydes inhibit thioredoxin reductase and induce Nrf2: potential candidates for cancer therapy and chemoprevention. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2010;48(1):98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ekmekcioglu C., Feyertag J., Marktl W. Cinnamic acid inhibits proliferation and modulates brush border membrane enzyme activities in Caco-2 cells. Cancer Letters. 1998;128(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ng L.-T., Wu S.-J. Antiproliferative activity of Cinnamomum cassia constituents and effects of pifithrin-alpha on their apoptotic signaling pathways in Hep G2 cells. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:6. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep220.492148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu S.-J., Ng L.-T., Lin C.-C. Cinnamaldehyde-induced apoptosis in human PLC/PRF/5 cells through activation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins and MAPK pathway. Life Sciences. 2005;77(8):938–951. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dornish J. M., Pettersen E. O., Oftebro R. Synergistic cell inactivation of human NHIK 3025 cells by cinnamaldehyde in combination with cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) Cancer Research. 1988;48(4):938–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang J.-H., Liu L.-Q., He Y.-L., Kong W.-J., Huang S.-A. Cytotoxic effect of trans-cinnamaldehyde on human leukemia K562 cells. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2010;31(7):861–866. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moon K. H., Pack M. Y. Cytotoxicity of cinnamic aldehyde on leukemia L1210 cells. Drug and Chemical Toxicology. 1983;6(6):521–535. doi: 10.3109/01480548309017807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Niknahad H., Shuhendler A., Galati G., et al. Modulating carbonyl cytotoxicity in intact rat hepatocytes by inhibiting carbonyl metabolizing enzymes. II. Aromatic aldehydes. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2003;143-144:119–128. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(02)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hatch G. G., Anderson T. M., Lubet R. A., et al. Chemical enhancement of SA7 virus transformation of hamster embryo cells: evaluation by interlaboratory testing of diverse chemicals. Environmental Mutagenesis. 1986;8(4):515–531. doi: 10.1002/em.2860080404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stammati A., Bonsi P., Zucco F., Moezelaar R., Alakomi H.-L., Von Wright A. Toxicity of selected plant volatiles in microbial and mammalian short-term assays. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1999;37(8):813–823. doi: 10.1016/S0278-6915(99)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chuang L.-Y., Guh J.-Y., Chao L. K., et al. Anti-proliferative effects of cinnamaldehyde on human hepatoma cell lines. Food Chemistry. 2012;133(4):1603–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.02.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang J.-Q., Luo X.-X., Wang S.-W., Xie Y.-H. Effect of cinnamaldehyde on activity of tumor and immunological function of S180 sarcoma in mice. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2006;10(11):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moon E.-Y., Lee M.-R., Wang A.-G., et al. Delayed occurrence of H-ras12V-induced hepatocellular carcinoma with long-term treatment with cinnamaldehydes. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;530(3):270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hoskins J. A. The occurrence, metabolism and toxicity of cinnamic acid and related compounds. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 1984;4(6):283–292. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550040602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang Y., Yang X. Y., Kunag Z. S., Xiao C. Inhibitory effect of cinnamic acid germanium on growth of uterocervical carcinoma (U14) cells in mice. Linchuang Yu Shiyan Binglixue Zazhi. 2010;26:467–470. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang L. P., Ji Z. Z. Synthesis, antiinflammatory and anticancer activity of cinnamic acids, their derivatives and analogues. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 1992;27(11):817–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liu L., Hudgins W. R., Shack S., Yin M. Q., Samid D. Cinnamic acid: a natural product with potential use in cancer intervention. International Journal of Cancer. 1995;62(3):345–350. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang Q., Wang Y., Chai W., et al. Induced-differentiation effects of cinnamic acid on human osteogenic sarcoma cells cultured primarily in vitro. Zhonghua Zhongliu Fangzhi Zazhi. 2009;16(9):668–672. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Soares V. C. G., Bonacorsi C., Andrela A. L. B., et al. Cytotoxicity of active ingredients extracted from plants of the Brazilian `Cerrado’. Natural Product Communications. 2011;6(7):983–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bemani E., Ghanati F., Boroujeni L. Y., Khatami F. Antioxidant activity, total phenolics and taxol contents response of hazel (Corylus avellana L.) cells to benzoic acid and cinnamic acid. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. 2012;40(1):69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gravina H. D., Tafuri N. F., Silva Júnior A., et al. In vitro assessment of the antiviral potential of trans-cinnamic acid, quercetin and morin against equid herpesvirus 1. Research in Veterinary Science. 2011;91(3):e158–e162. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ito K., Nakazato T., Xian M. J., et al. 1′-acetoxychavicol acetate is a novel nuclear factor κB inhibitor with significant activity against multiple myeloma in vitro and in vivo . Cancer Research. 2005;65(10):4417–4424. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kondo A., Ohigashi H., Murakami A., Suratwadee J., Koshimizu K. 1′-Acetoxychavicol acetate as a potent inhibitor of tumor promoter-induced Epstein-Barr virus activation from Languas galanga, a traditional Thai condiment. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 1993;57(8):1344–1345. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]