Abstract

Familial Mediterranean fever is an autosomal recessive autoinflammatory disorder mainly affecting Mediterranean populations, which is associated with mutations of the MEFV gene that encodes pyrin. Functional studies suggest that pyrin is implicated in the maturation and secretion of interleukin-1 (IL-1). The IL-1 receptor antagonist or anti-IL-1 monoclonal antibody may therefore represent a rational approach for the treatment of the rare patients who are refractory to conventional therapy. We report the case of a young female affected by familial Mediterranean fever who proved to be resistant to colchicine and was successfully treated with canakinumab.

Keywords: interleukin-1, colchicine, familial Mediterranean fever, anti-IL-1 treatment, biologic agents

Case report

A 30-year-old Bolivian woman with familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) was referred to our Centre of Research on Immunopathology and Rare Diseases (CMID) in November 2010 because of remitting fever over a 6-month period, painful symmetrical arthritis of the wrists, elbows, and knees without radiographic erosions or deformities, myalgia, diarrhea with abdominal pain, and weight loss.

FMF had been diagnosed 7 years before at the Division of Medicine of the Johns Hopkins Institute of Baltimore. At that time, the disease was characterized by short-lived recurrent inflammatory febrile attacks, concurrent with abdominal and chest pain and erysipelas-like skin lesions.

She had been under regular treatment with colchicine 1 mg daily since diagnosis with a good response for 6 years. In 2008, she moved to Italy to continue her education, and in June 2010, her attacks recurred with different clinical features including predominant articular symptoms, fever, and abdominal crises, despite continued administration of colchicine (1 mg/day).

In August 2010, she was referred to our centre (CMID). She reported frequent attacks (three episodes a week, 12 crises in the preceding month) dominated by more severe arthralgia and abdominal pain. During intercritical periods, the symptoms diminished but did not cease altogether as had previously been the case. Her quality of life was severely compromised with decreasing body weight (from 56 kg to 49 kg).

On admission, laboratory data showed normal white blood cells and platelet count, and slight elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (18 mm/hour) and C-reactive protein (CRP: 1 mg/dL, normal values <0.5 mg/dL). Serum Amyloid A (SAA) was normal as were creatinine, transaminases, and uric acid levels and urine analysis.

Rheumatoid factor, as well as antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, anti-Ro/La, antiendomysial, antitransglutaminase, and antitropheryma whipplei antibodies, was negative. Mild proteinuria (450 mg/24 h) was detected during an FMF attack. Biopsy of the periumbilical fat was negative.

Blood culture, stool examination, and culture, as well as urine culture were carried out because of recurrent high fever (39.4°C) and were negative.

Imaging studies including chest and abdominal computed tomography scans and echocardiography were unremarkable. While genetic revaluation confirmed a pM694v mutation in the MEFV gene, a previously undetected second mutation was identified in pI591T.

First of all, we increased the dose of colchicine from 1 mg to 2 mg daily, but this treatment was immediately discontinued due to the rapid appearance of side effects (diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting).

We began discussing alternative treatments.

Paracetamol, corticosteroids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may sometimes be useful as analgesics during acute attacks, but not in this case.

On the basis of an increasing number of case reports and case series in which biologic drugs have been successfully used in the management of colchicine-resistant FMF,1,2 we administered Anakinra (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), a recombinant, non-glycosylated form of the human interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist, subcutaneously at a dose of 100 mg daily.

Due to the off-label use of this therapy, informed consent was obtained from the patient before starting treatment.

Albeit effective, anakinra was discontinued after 10 days due to a severe cutaneous reaction at the site of injection. The patient was therefore switched to canakinumab (ACZ885, Ilaris; Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland), a fully humanized monoclonal antibody targeting IL-1β.3,4 This treatment was started in December 2010, at a dose of 150 mg given subcutaneously, followed by two more administrations 8 weeks apart.

Informed consent was again provided by the patient for this drug before starting treatment.

The effects of canakinumab were monitored over the following 6-month period.

A significant improvement in the clinical symptoms was observed after the first administration.

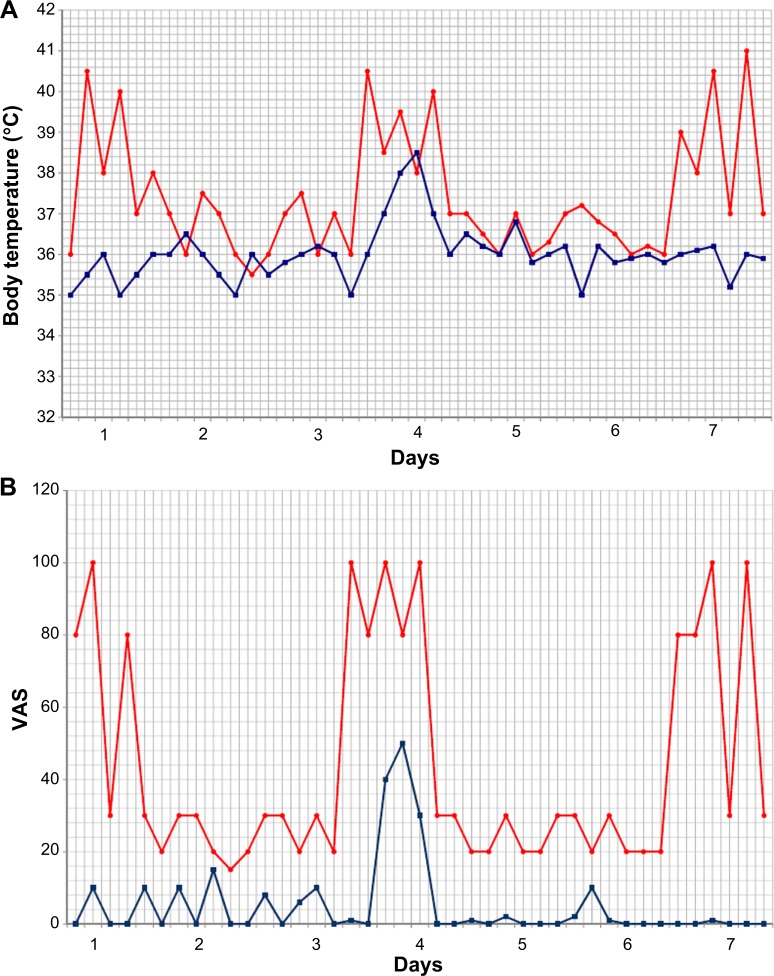

During treatment with canakinumab, the patient reported only three minor episodes of FMF. Figure 1 shows the profiles of body temperature and visual analog scale.

Figure 1.

Effect of canakinumab on thermal curves and its impact on VAS.

Notes: (A) Thermal curves of the week preceding (red line) and the week following the administration of the first dose of canakinumab (blue line). (B) VAS values of the week preceding (red line) and the week following the administration of the first dose of canakinumab (blue line).

Abbreviation: VAS, visual analog scale.

Acute-phase reactants (CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and SAA) were evaluated every 4 weeks over a 24-week period. These laboratory parameters normalized within 4 weeks.

The 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) standard version5,6 and the Health Assessment Questionnaire7 were used to monitor the patient’s health perception and physical ability.

At baseline, scores for health-related quality of life (HRQoL) were indicative of a reduced quality of life compared with the general population.

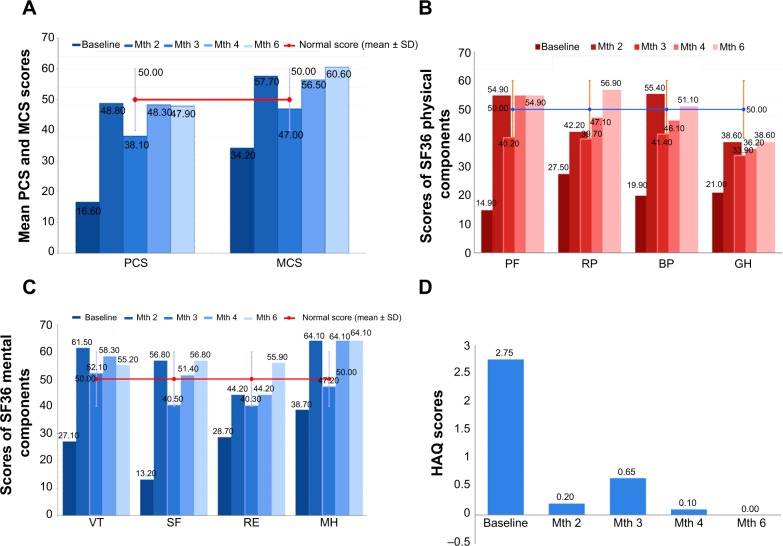

After the first dose of canakinumab, the mean SF-36 physical-component summary score increased from 16.6 at baseline to 48.8 with an increase of 32 points, and it was 47.9 by the end of follow-up. These values approximate those of the general population. The mean SF-36 mental-component summary (MCS) also showed a significant increase over the course of the study from 34.2 at baseline to 57.7 after 1 month of treatment and 60.6 at the end of the study (with an increase of 26.4 points from baseline). Notably, the SF-36 MCS score at the end of the study exceeded that of the general population (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Effects of canakinumab on HRQoL and HAQ.

Notes: (A) Results of questionnaires on quality of life in relation to physical and mental health. (B) Results of questionnaires on quality of life in relation to physical health, filled in during the course of follow-up. (C) Results of questionnaires on quality of life in relation to mental health. (D) Results of questionnaires on the degree of disability in carrying out common daily activities.

Abbreviations: PCS, physical-component summary; MCS, mental-component summary; PF, physical functioning; RP, role limitations – physical; BP, bodily pain; GH, general health perception; VT, vitality; SF, social functioning; RE, role limitations – emotional; MH, mental health; Mth, month; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire.

At baseline, scores for all SF-36 individual domains were lower than in the general population, especially for physical functioning, pain, and general health (Figure 2B). Improvements in score were evident for all domains by the end of the first month after starting therapy. Further improvements were observed over the entire period of monitoring, with mean scores approaching normal (Figure 2B).

Before starting treatment, all four subscale scores of SF-36 mental component were lower than for the general population and the difference was remarkable for social functioning (36.8 points difference) and vitality (22.9 points difference). After finishing treatment, all domains exceeded those of the general population. The greatest improvements in mental functions were seen in vitality and social functioning (Figure 2C).

Over the course of the study, the mean Health Assessment Questionnaire score decreased from 2.75 at baseline to 0.0 at the end of the study, indicating a complete remission of functional disability (Figure 2D).

Therapy with canakinumab for up to 24 weeks was well tolerated. No adverse events were observed.

Discussion

Daily administration of colchicine is the standard therapy for prophylaxis of FMF attacks and amyloid deposition in FMF.8

Colchicine inhibits leukocyte chemotaxis through a direct effect on microtubuli. It also reduces the expression of adhesion molecules on white blood cells and endothelial cells, thereby interfering with leukocyte transfer to the inflammatory site.9

The beneficial role of colchicine in FMF attacks is well documented by open-label studies in adult and pediatric patients, as well as by placebo-controlled trials in adult patients.10 Long-term administration of colchicine leads to complete remission in two thirds of the patients and partial remission (defined as a significant decrease in the frequency of attacks or remission of a single symptom) in another third of the patients with FMF.10 However, a substantial minority (5%–10%) of patients does not respond to colchicine treatment.10

Quite recently, an increasing number of case reports in which biologic drugs (tumor necrosis factor-alfa, IL-6, and IL-1 inhibitors) have been used in the management of patients with FMF who were unresponsive to colchicines have been published.

In this setting, IL-1 blockade with either anakinra or canakinumab has been reported in case series and both agents would appear to be effective.11 This year, positive results were published regarding the first randomized controlled study of an IL-1 blocker, rilonacept, in 14 colchicine-resistant patients.12

On the basis of the available studies, French and Israeli experts made evidence-based recommendations for the management of FMF. They recommended adding anti-IL-1 therapy for colchicine-resistant patients and starting with a short half-life molecule (anakinra) to assess efficacy before considering long half-life IL-1-targeting therapies.2

The results of our study indicate that a single dose of canakinumab induces rapid remission of symptoms in patients with FMF, with minimal disease activity in the first 4 weeks and sustained remission by week 8. Remission of symptoms was accompanied by the suppression of inflammation, as indicated by the decrease until normalization of CRP.

FMF, like other autoinflammatory diseases, can greatly impact HRQoL as previously reported by in-depth interviews of patients with this disease.13

Our study confirms that FMF has a negative impact on the patient’s HRQoL, and especially on the physical component, and shows beneficial changes induced by canakinumab. The most compromised SF-36 domains in FMF were physical functioning, pain, and general health. Within 1 month of therapy, improvements were evident in all affected SF-36 domains in agreement with the rapid remission of symptoms observed in the patient. Four weeks after receiving the first dose of canakinumab, SF-36 physical-component summary and SF-36 MCS scores approached those of the general population.

In summary, these results provide evidence that canakinumab induces rapid reversal of the clinical symptoms of FMF paralleled by a decrease in inflammation markers.

Remission can be maintained by a standard administration every 8 weeks, leading to a significant improvement in HRQoL scores. Notably, canakinumab 150 mg/dose is currently being investigated in FMF in a phase II clinical trial (trial registration: clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01088880).

Our patient has been in complete clinical remission for 2 years, and we are considering the possibility of tapering therapy.

However, there is still a need for randomized controlled trials using canakinumab to treat FMF.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Chae JJ, Aksentijevich I, Kastner DL. Advances in the understanding of familial Mediterranean fever and possibilities for targeted therapy. Br J Haematol. 2009;146(5):467–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ter Haar NM, Frenkel J. Treatment of hereditary autoinflammatory diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(3):252–258. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, et al. Canakinumab in CAPS Study Group Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2416–2425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lachmann HJ, Lowe P, Felix SD, et al. In vivo regulation of interleukin 1beta in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1029–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware JE., Jr . SF-36 Physical and Mental Summary Scales: A User’s Manual Boston. Boston, MA: The Health Insititute, New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:137–145. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meinzer U, Quartier P, Alexandra JF, Hentgen V, Retornaz F, Koné-Paut I. Interleukin-1 targeting drugs in familial Mediterranean fever: a case series and a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41(2):265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozturk MA, Kanbay M, Kasapoglu B, et al. Therapeutic approach to familial Mediterranean fever: a review update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;4(suppl 67):S77–S86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kallinich T, Haffner D, Niehues T, et al. Colchicine use in children and adolescents with familial Mediterranean fever: literature review and consensus statement. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):e474–e483. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ter Haar N, Lachmann H, Özen S, et al. Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) and the Eurofever/Eurotraps Projects Treatment of autinflammatory diseases: results from the Eurofever Registry and a literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:678–685. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashkes PJ, Spalding SJ, Giannini EH, et al. Rilonacept for colchicine-resistant or -intolerant familial Mediterranean fever a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(8):533–541. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-8-201210160-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deger SM, Ozturk MA, Demirag MD, et al. Health-related quality of life and its associations with mood condition in familial Mediterranean fever patients. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31(5):623–628. doi: 10.1007/s00296-009-1334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]