Abstract

Thousands of DNA breaks occur daily in mammalian cells, including potentially tumorigenic double-strand breaks (DSBs) and less dangerous but vastly more abundant single-strand breaks (SSBs). The majority of SSBs are quickly repaired, but some can be converted to DSBs, posing a threat to the integrity of the genome. Although SSBs are usually repaired by dedicated pathways, they can also trigger homologous recombination (HR), an error-free pathway generally associated with DSB repair. While HR-mediated DSB repair has been extensively studied, the mechanisms of HR-mediated SSB repair are less clear. This chapter describes a protocol to investigate SSB-induced HR in mammalian cells employing the DR-GFP reporter, which has been widely used in DSB repair studies, together with an adapted bacterial CRISPR/Cas system.

Keywords: Homologous recombination, single-strand breaks, DNA nicks, DNA repair, CRISPR/Cas, Cas9, DR-GFP reporter

1. Introduction

Mammalian cells endure continuous assault on the integrity of their genomes exerted by exogenous agents such as ionizing radiation, chemicals, and UV light. Additionally, by-products of endogenous metabolic activities - reactive-oxygen species, free radicals - and cellular processes that directly involve DNA - replication, transcription - cause DNA damage (Horton et al., 2008). Among the most dangerous, but least abundant (an estimated 10 per cell per day), are DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). By contrast, tens of thousands of less dangerous DNA single-strand breaks (SSBs) occur daily in mammalian cells (Caldecott, 2008). SSBs frequently arise as intermediates in excision repair of oxidatively damaged DNA bases (Hegde et al., 2008), but may also form due to failed reactions of DNA maintenance enzymes, such as topoisomerase I (Pommier et al., 2003). Although SSBs, as such, do not pose a serious threat to the integrity of the genome, replication of nicked DNA can result in formation of a DSB (Haber, 1999; Saleh-Gohari et al., 2005).

Unless repaired in an appropriate manner, DSBs can cause chromosome loss or potentially cancer-causing chromosome rearrangements (Bunting and Nussenzweig, 2013; Weinstock et al., 2006). Molecular mechanisms of DSB repair have been investigated extensively in mammalian cells using rare-cutting endonucleases, primarily I-SceI, to introduce DSBs into the genome (Liang et al., 1998; Rouet et al., 1994). These and other studies lead to the conclusion that cells have two robust DSB repair pathways, homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). NHEJ involves processing of the broken DNA ends followed by ligation to seal the break (Deriano and Roth, 2013; Lieber, 2010). Because end processing can lead to loss of DNA sequences, NHEJ is often considered to be error-prone, although it is certainly capable of precise DSB rejoining (Bétermier et al., 2014).

HR involves a seemingly more complex set of enzymatic reactions that utilizes an intact DNA strand, usually the sister chromatid, to faithfully restore the original sequence at the break site (Jasin and Rothstein, 2013; San Filippo et al., 2008). Unlike NHEJ, which is functional throughout the cell cycle, HR activity is limited to the S- and G2 phases. HR is initiated by resection of the 5’ DNA ends to give rise to 3’ single-stranded (ss) DNA overhangs. In subsequent steps, the resected strand invades an intact, homologous DNA template, forming heteroduplex DNA. The invading strand then acts as a primer for repair synthesis from the template, followed by dissolution of the heteroduplex, re-annealing of the newly synthesized strand to the second end of the DNA, and sealing of remaining gaps.

Like DSBs, endonuclease-induced SSBs also stimulate HR in mammalian cells (Davis and Maizels, 2014; McConnell Smith et al., 2009; Metzger et al., 2013). Interestingly, the mechanistic requirements of SSB-induced HR vary depending on whether the available template DNA is single- or double-stranded (Davis and Maizels, 2014). Although DSB and SSB repair pathways likely involve some mechanistically distinct but also overlapping steps, how nicks trigger HR is not well understood. For instance, it is unclear whether SSB-induced HR involves formation of a DSB intermediate or whether DNA replication influences the process.

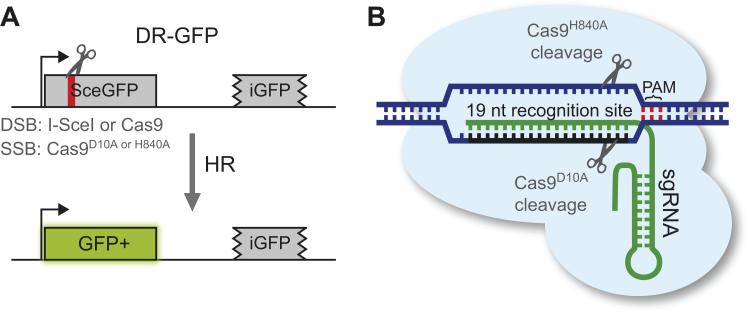

Among the most common approaches to studying DSB-induced HR involves the use of a GFP reporter, DR-GFP, which allows flow cytometry-based detection of HR stimulated by I-SceI endonuclease-induced DSBs (Pierce and Jasin, 2005; Pierce et al., 1999) (Fig. 1A). The recent adaptation of the bacterial adaptive immunity system, CRISPR/Cas (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats / CRISPR-associated), has enabled straightforward induction of DSBs and SSBs at desired loci by the RNA-guided Cas9 endonuclease (Gasiunas et al., 2012; Jinek et al., 2012; Mali et al., 2013a). Here we adapt the DR-GFP reporter for measuring both DSB and SSB-induced HR, using wild-type Cas9 endonuclease and Cas9 nickases, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the DR-GFP reporter and the RNA guided Cas9 endonuclease. A. The DR-GFP reporter consists of two copies of the GFP gene in tandem arrangement. The first copy (SceGFP) is inactive due to the presence of a stop codon within the I-SceI cleavage site (red bar), while the second copy (iGFP) is truncated at both ends. After cleavage within SceGFP by I-SceI or a Cas9 nuclease, HR uses iGFP as a template to restore the GFP open reading frame. B. Cas9 nuclease has two catalytic domains, with each domain cleaving a single DNA strand guided by a short RNA (gRNA, green) containing 19 nt complementary to the target site. Mutation of either catalytic domain (D10A or H840A) turns Cas9 into a nickase (as indicated), while mutation of both residues makes it catalytically dead (not shown). Cas9 requires a PAM motif (NGG) immediately downstream of the recognition site (red).

2. Cloning the nickase and catalytically dead variants of Cas9

2.1. The Cas9 endonuclease

Cas9 (CRISPR-associated 9) is a RNA-guided endonuclease involved in bacterial adaptive immunity (Hsu et al., 2014). Cas9 forms a nucleoprotein complex with a guide RNA (gRNA) containing a 19 nt sequence that determines binding specificity based on Watson-Crick base pairing (Cong et al., 2013; Jinek et al., 2012; Mali et al., 2013a) (Fig. 1B). The only sequence requirement in the genomic target is a NGG PAM motif (where N signifies any nucleotide) directly downstream from the binding sequence (Fig. 1B). Cas9 contains two catalytic domains, the modular RuvC-like domain and the C-terminal HNH-like domain. Each domain cleaves one of the DNA strands, resulting in a blunt-ended DSB (or short overhang) 3 bp upstream of the PAM motif (Fig. 1B). Mutation of the active site in either catalytic domain turns wild-type Cas9 (Cas9WT) into a nicking enzyme (nCas9), while mutating both active sites renders it catalytically dead (dCas9), but still able to efficiently bind DNA, a feature that has been exploited for dCas9-mediated transcription regulation and visualization of DNA sequences in living cells (Chen et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013b). The Cas9D10A variant with a mutation in the active site of the RuvC-like domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA binding sequence, while Cas9H840A with a mutation in the HNH-like domain cleaves the non-complementary strand, and Cas9D10A/H840A is catalytically dead (Jinek et al., 2012).

There are two widely used sets of Cas9 expression vectors for mammalian cells available from Addgene (www.addgene.com), both of which include a codon-optimized Cas9 cDNA sequence. The set generated by the Zhang laboratory (www.addgene.org/crispr/zhang) is a bicistronic system wherein both Cas9 and gRNA are expressed from a single plasmid. The advantage of this system is that only one plasmid needs to be generated and transfected if one type of Cas9 or gRNA is to be used. However, this can also be disadvantageous if the experimental design requires using different Cas9 variants (e.g., for generating both DSBs and SSBs) or gRNAs because multiple plasmids will need to be generated. The second commonly used set of Cas9 expression vectors, generated by the Church laboratory (http://www.addgene.org/crispr/church), has separate plasmids for Cas9 and gRNA expression. We routinely use the Church plasmid set, given our comparison of multiple Cas9 variants and gRNAs, and the following protocol is based on these reagents. To obtain Cas9H840A and catalytically-dead Cas9, we mutated the available wild-type and Cas9D10A variants, respectively, as described below.

2.2. Generating Cas9H840A and Cas9D10A/H840A expression vectors

Step 1. Obtain the wild-type (ID 41815) and D10A (ID 41816) variants of Cas9 and empty gRNA expression plasmid (ID 41824) from Addgene. Prepare plasmid stocks using midi- or maxi-prep kit of your choice. (We routinely use Life Technologies DNA purification kits.)

Step 2. Order the following primers to sequence and generate mutant Cas9 nucleases:

| Cas9mutF | 5’-GACGTGGATGCTATCGTGCCCCAGTC TTTTCTCAA-3’ |

| Cas9mutR | 5’-AGCATCCACGTCGTAGTCGGAGAGCCGATTGATGTCCAG-3’ |

| Cas9seqF1 | 5’-GCTGTTTTGACCTCCATAGAAG-3’ |

| Cas9seqF2 | 5’-TGATAAGGCTGACTTGCGG-3’ |

| Cas9seqF3 | 5’-AGACGCCATTCTGCTGAGTG-3’ |

| Cas9seqF4 | 5’-CGCAAATCAGAAGAGACCATC-3’ |

| Cas9seqF5 | 5’-GAACGCTTGAAAACTTACGC-3’ |

| Cas9seqF6 | 5’-GCCCGAGAGAACCAAACTAC-3’ |

| Cas9seqF7 | 5’-GGCTTCTCCAAGGAAAGTATC-3’ |

| Cas9seqF8 | 5’-CGTGGAACAACACAAACACTAC-3’ |

| Cas9seqR1 | 5’-ACTGTAAGCGACTGTAGGAG-3’ |

Both mutagenesis primers (Cas9mutF and Cas9mutR) include 15 nt overlapping overhangs that are necessary for ligation-independent cloning using In-Fusion method (see 2.3. step 2).

2.3 Cloning and verifying the constructs

Step 1. Setup the following two PCR reactions using a high-fidelity polymerase, such as in the iProof polymerase kit from Bio Rad.

Cas9wt or Cas9D10A DNA (10 ng)

Cas9mutF primer (200 nM)

Cas9mutR primer (200 nM)

dNTPs (200 nM)

10x reaction buffer (5 μL)

H2O (fill up to 25 μL)

iProof polymerase (0.2 μL)

Run PCRs in a heated-lid PCR thermocycler using the following program:

98 °C for 30 s

98 °C for 30 s

55 °C for 30 s

72 °C for 5 min

Repeat steps 2-4 30 times

72 °C for 10 min

12 °C ∞

Electrophorese the PCR products on a 0.8% agarose gel and excise the 9.5-kb band. Purify the DNA using a gel extraction kit (e.g., from Life Technologies).

Step 2. Circularize the purified PCR products using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Transform competent bacteria using the obtained circularized DNA solution and streak on LB plates containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin. Typically, 10-100 colonies can be found on the plate after overnight incubation. Pick five colonies from each plate, inoculate 5 mL LB medium, incubate overnight at 37 °C and isolate DNA using method of your choice. Verify the sequence of DNA isolated from two clones by sequencing using the primers shown in paragraph 2.2.

Step 3. After verifying the correctly mutated Cas9H840A and Cas9D10A/H840A sequences, prepare plasmid stocks. DNA obtained by using Life Technologies midi- and maxi-prep kits is suitable for direct transfection without further purification steps.

3. Selection of the target site and cloning of gRNA constructs

3.1. Selecting suitable target sequences

Obtain the DR-GFP reporter from Addgene (ID 26475). To confirm proper functioning of the DR-GFP assay, we recommend also obtaining the I-SceI expression vector (pCBASceI; ID 26477).

The following sequence in the SceGFP part of the DR-GFP reporter (Fig. 1A) contains the cleavage site for I-SceI, which gives rise to 4 bp overhangs (demarcated by gray arrowheads).

Cas9 recognizes a 19 bp DNA sequence that binds the gRNA followed by the NGG PAM motif in the following format: 3’-NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN?NNN-NCC-5’, where the arrowhead indicates the cleavage site. (See Jinek et al., 2012) for precise in vitro mapping of cleavage sites on both strands.) A PAM motif (underlined) is fortuitously present next to the I-SceI cleavage site, such that SceGFP can be targeted for cleavage by Cas9 using the 19 nt sequence (bold) adjacent to the PAM motif in the gRNA. With this approach, Cas9 cleavage (open and filled arrowheads) results in a DSB at almost an identical position as I-SceI. Moreover, SceGFP is specifically cleaved because the iGFP repair template has five mismatches with the gRNA and in addition the AGG PAM motif is not present. The Cas9D10A and Cas9H840A nick the DNA at the filled and open arrowheads, respectively.

An alternative target sequence located on the opposite DNA strand is shown below. In this case, although the PAM motif (underlined) is present, iGFP has 10 mismatches with the gRNA sequence.

In the following part of the protocol, we use the first target sequence.

3.2. Cloning the guide RNA constructs

The empty gRNA expression vector generated by the Church laboratory contains an U6 pol III promoter that drives the expression of the gRNA. A specific protocol for cloning the target sequence into the gRNA expression vector is provided using two specific 60 nt oligos (http://www.addgene.org/static/cms/files/hCRISPR_gRNA_Synthesis.pdf) and we have succesfully used this protocol. Below we detail an alternative protocol that requires one 57 nt oligonucleotide (oligo) containing the specific target sequence and three short universal oligos that can be re-used for other target sequences. Cloning the new gRNA expression construct involves running two separate PCR reactions using the empty gRNA expression vector as a template. The first reaction with two universal primers produces a universal 2-kb fragment (which hence can be repetitively used). The second reaction with the specific forward primer and a universal reverse primer produces a 2-kb fragment containing the target 19 nt sequence. Both fragments, containing 15 nt overlaps, are then combined together using the seamless In-Fusion method, giving a circular final plasmid. (See also Zhang et al., 2014)

Step 1. Order the following specific primer gRNAF1 containing the sequence for targeting SceGFP, gRNAF1SceGFP. Bold font indicates the specific target sequence, such that for each new gRNA construct only this sequence needs to be changed.

5’-AAGGACGAAACACCGGTGTCCGGCTAGGGATAACGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAG-3’

Step 2. Order the following universal primers:

| gRNAF2 | 5’-CGTCAAGAAGGCGATAGAAG-3’ |

| gRNARI | 5’-CGGTGTTTCGTCCTTTCCAC-3’ |

| gRNAR2 | 5’-ATCGCCTTCTTGACGAGTTC-3’ |

| gRNAseq | 5’-TGGACTATCATATGCTTACCGTAAC-3’ |

Step 3. Setup the following two PCR reactions using a high-fidelity polymerase (e.g., from the iProof polymerase kit from Bio Rad).

| PCR 1 (specific) | PCR 2 (universal) |

| empty gRNA vector (10 ng) | empty gRNA vector(10 ng) |

| gRNAFISceGFP (specific) primer (200 nM) | gRNAF2 (universal) primer (200 nM) |

| gRNAR2 (universal) primer (200 nM) | gRNARI (universal) primer (200 nM) |

| dNTP (200 nM) | dNTP (200 nM) |

| 10× reaction buffer (5 μL) | 10× reaction buffer (5 μL) |

| H20 (fill up to 25 μL) | H20 (fill up to 25 μL) |

| iProof polymerase (0.2 μL) | iProof polymerase (0.2 μL) |

Run PCRs in a heated-lid PCR thermocycler using the following program:

98 °C for 1 min

98 °C for 30 s

56 °C for 30 s

72 °C for 1 min

Repeat steps 2-4 30 times

72 °C for 5 min

12 °C ∞

Electrophorese the PCR products on a 1% agarose gel and excise the 2-kb bands. Purify the DNA using a gel extraction kit (e.g., from Life Technologies).

Step 4. Combine the two purified PCR products using the In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech), as described in step 2 of paragraph 2.3. The gRNA vector is kanamycin resistant, so use LB plates and media containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin. Verify the sequence of the gRNA from two clones using the primer gRNAseq.

Tip: The universal 2-kb fragment produced by PCR 2 can be reused for subsequent cloning reactions, such that for each new gRNA vector only one (specific) PCR reaction needs to be run.

4. Cell transfection and FACS analysis

We describe the protocol for transfection of HEK293 cells using the Nucleofector-2b (Lonza). Either the commercial (Lonza) or home-made (Box 1) nucleofection solution can be used for transfections. In the case of HEK293 cells, we used program A-023 and the home-made nucleofection solution. Other cells might require different programs which can be found on the Lonza website or in the program list of the nucleofector. Table 1 shows optimized nucleofection conditions for additional cell lines that we tested.

Box 1. Home-made nucleofection solution.

Prepare the following:

Solution I:

2 g ATP-disodium salt

1.2 g MgCb 6 • H20

10 ml H20

Sterilize the solution by passing it through a 0.22 μm filter and split into 80 μl aliquots. Store at −20 °c.

Solution II:

6.0 g KH2P04

0.6 g NaHC03

0.2 g glucose

300 ml H20

Adjust the pH to 7.4 with NaOH and add water to a final volume of 500 ml. Filter-sterilize and split into aliquots of 4 ml. Store at −20 °C.

On the day of the experiment thaw and mix one aliquot of solution Iwith one aliquot of solution II. The final solution can be stored at 4 °C for up to two weeks. Pre-warm the final solution to 37 °C before transfection.

Table 1.

Optimized nucleofection conditions for tested cell lines.

| Cell line | Nucleofector program |

DNA quantity (μg) Cas9:gRNA:DR-GFP |

|---|---|---|

| HEK293 | A-023 | 1:1:2 |

| U20S | X-001 | 1:1:1 or 1:1:2 |

| AA8 (Chinese hamster cells) | D-023 | 5:2.5:5 |

| mouse embryonic stem cells | A-023 | 4:4:4 (maximum cell survival) or 15:5:5 (maximum transfection efficiency) |

4.1. Transfection

See Fig. 2A for an overview of the procedure.

Fig. 2.

Representative experiment testing different variants of Cas9 for HR in the DR-GFP reporter in HEK293 cells. A. Schematic overview of the experiment. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with plasmid DNA (Table 2) using Nucleofector-2b (Lonza, program A-023). After 48 h, the percent GFP+ cells, indicative of HR efficiency, was measured by flow cytometry. B. FlowJo software was used to analyze the flow cytometry data. Left, SSC vs FSC was used to set the gate for live cells. Middle, FL1 vs FL2 was used to determine the percent GFP+ cells from a control sample (cells above diagonal line are GFP+); note that there is a relatively high background of cells using the plasmid DR-GFP reporter. Right, GFP+ cells are much higher with induced DNA damage. C. Results from three independent experiments. SSBs created by Cas9D10A and Cas9H840A are capable of inducing HR, albeit at reduced frequency, as compared to Cas9WT. Error bars represent standard deviation from the mean.

Step 1. Subculturing cells prior to transfection: Plate 6-7 million cells into a 150-mm tissue culture plate 24 h before transfection such that cells are 70-80% confluent on the day of transfection. Subculturing cells 24 h before transfection significantly improves reproducibility of results.

Step 2. Preparation of tissue culture plates and media: For each sample prepare a 60-mm tissue culture plate containing 2.5 mL culture media at least 1 h before transfection. Incubate at 37 °C to warm and to equilibrate the pH of the culture medium. In addition, warm additional culture medium and nucleofection solution to 37 °C.

Step 3. Preparation of the plasmid mix: In the case of HEK293 cells, Cas9 endonuclease (either WT, D10A, H840A or D10A/H840A) and gRNA plasmids are used in a ratio of 1:1 (1 μg: 1 μg). The amount and ratio of plasmids may need to be adjusted depending on the cell line used (e.g., Table 1). Unless cells harbor a genomically integrated DR-GFP copy, the DR-GFP plasmid is also co-transfected (2 μg). (Note: HEK293 DR-GFP cells have been developed, Nakanishi et al., 2005). As controls, we use either Cas9WT with a gRNA expression vector containing no target sequence or Cas9D10A/H840A with the specific gRNA of interest. For every sample, prepare a separate sterile eppendorf tube with the plasmid mix (Table 2), ideally starting with a mix of the common plasmids (e.g., in Samples 2-5 below, a mix of DR-GFP and the SceGFP gRNA can be prepared and then aliquoted for each sample).

Table 2.

Plasmid mixes for the experiment described in Fig. 2 (DNA quantity in μg in parentheses). To equalize the total amount of DNA in each sample, an empty plasmid (pCAGGS) is added to samples 6 and 7.

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 | Sample 5 | Sample 6 | Sample 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | WT (1) |

WT (1) |

D10A (1) |

H840A (1) |

D10A/ H840A (1) |

- | - |

| gRNA | empty (1) |

SceGFP (1) |

SceGFP (1) |

SceGFP (1) |

SceGFP (1) |

- | - |

| DR-GFP | (2) | (2) | (2) | (2) | (2) | (2) | - |

| Other | pCBAScel (1) + pCAGGS (1) |

NZE-GFP (2) + pCAGGS (2) |

Tip: To confirm proper functioning of the DR-GFP assay, prepare an extra sample with the I-SceI endonuclease expression vector (pCBASceI, 1 μg). To determine overall transfection efficiency, prepare an extra sample with any GFP expression plasmid (e.g., NZE-GFP, 2 μg).

Tip: Do not exceed the total volume of ~10 μl of the plasmid mix. Larger volumes will significantly dilute the nucleofection solution which might lead to reduced or inconsistent transfection efficiencies.

Tip: Do not use very concentrated plasmid stocks to avoid pipetting errors. Dilute the plasmid stocks if necessary.

Step 4. Preparation of cells for transfection: Trypsinize and count the cells. For each sample, dispense two million cells into in a sterile conical 15-mL tube and spin down (3 min at 1000 rpm). Carefully aspirate the supernatant, resuspend cells in 2 mL sterile PBS by vortexing at low speed. Spin down cells and carefully aspirate PBS, leaving the pellet as dry as possible. Residual PBS dilutes the transfection solution and might influence the transfection efficiency.

Step 5. Nucleofection: Select the appropriate program on the nucleofector. Resuspend the prepared plasmid mix in 100 μI nucleofection solution and transfer to the 15-ml tube containing the cell pellet. Resuspend the cells gently by pipetting up and down and transfer to a 2-mm Gene pulser cuvette. Make sure no bubbles are formed during the transfer as this may reduce transfection efficiency. Place the cuvette in the nucleofector and press the start button. Remove the cuvette, gently add 1 ml pre-warmed media into the cuvette, and transfer the cell suspension into the 60-mm culture dish prepared in step 1. Repeat this step for all experimental samples and controls. Incubate the cells at 37 °C for 48 h.

Step 6. Flow cytometry: After 48 h measure the frequency of GFP+ cells using a flow cytometer. Any instrument able to excite and detect GFP fluorescence is suitable. Trypsinize cells and resuspend them in 0.5 ml culture media in a flow cytometer tube. Analyze the samples using cell line specific cytometer settings. Forward (FSC) versus side (SSC) scatter plots are used to select the live cells (Fig. 2B). Typically, 30.000 live cells per sample are analyzed.

4.2. Analysis and interpretation of the results

Data collected with the flow cytometer are analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). Typical results obtained with HEK293 cells are shown in Fig. 2B. Gate the live cells based on the FSC and SSC (Fig. 2B, left panel). Use the negative control Sample 1 to set the gate for GFP analysis (Fig. 2B, middle panel) and apply the same gate to experimental samples (Fig. 2B right panel). DSBs induce relatively high levels of HR, either created by Cas9WT (~17.5%) or I-SceI (~14%). Nicks on the transcribed (Cas9D10A) or non-transcribed (Cas9H840A) DNA strand are also able to induce HR in ~9.5% and ~4% of cells, respectively. These results were obtained using transient transfection of the DR-GFP reporter, together with Cas9 and gRNA vectors, and so cells likely contain multiple copies of the DR-GFP reporter. Therefore, lower HR frequencies are to be expected when using cells harboring a single, genomically-integrated copy of the reporter. However, an advantage of cells with an integrated reporter is that the GFP+ background in the absence of nuclease expression is very low. It should be noted that SSBs are usually repaired within minutes (Caldecott, 2008), but nCas9s have the potential to nick the DNA again, in a repetitive breakage-repair cycle, until HR destroys the Cas9 recognition site while restoring the GFP open reading frame. Consequently, the induction of HR by SSBs measured using the DR-GFP reporter may be overestimated relative to physiological SSBs, which may be rapidly restored by SSB-specific repair pathways without the intervention of HR.

5. Materials

5.1. Cloning

Primers

Plasmids (Addgene)

Mini and midi-/maxi-prep DNA extraction kit

iProof polymerase kit (Bio Rad) Gel extraction kit

In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech)

LB plates and media containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin or 50 μg/mL kanamycin

Competent bacteria

PCR thermocycler

Incubator for bacteria (37 °C)

5.2. Cell culture, transfections, data collection and analysis

Plasmids

Sterile eppendorf tubes

Cell type specific culture media

Sterile Trypsin, 0.2%

Sterile PBS

Sterile 15 mL conical tubes

Cell culture dishes, 60 mm and 150 mm

Commercial (Lonza) or home-made (Box 1) nucleofection solution

Gene pulser cuvettes, 2 mm (Bio-Rad)

FACS tubes (if necessary with cell strainer cap) (BD falcon)

Nucleofector 2b (Lonza)

FACS analyzer

FlowJo software (Tree Star)

6. Summary

SSBs can induce HR but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. The DR-GFP reporter has been used widely to study factors involved DSB-induced HR. In this chapter, we have presented a straightforward protocol to assay SSB-induced HR using the Cas9 nicking endonuclease and DR-GFP. This approach can be used to investigate mechanisms of SSB-induced HR and may be also adaptable to explore other applications requiring targeted induction of SSBs, such as genome editing.

7. References

- Bunting SF, Nussenzweig A. End-joining, translocations and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:443–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bétermier M, Bertrand P, Lopez BS. Is non-homologous end-joining really an inherently error-prone process? PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldecott KW. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:619–631. doi: 10.1038/nrg2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Gilbert LA, Cimini BA, Schnitzbauer J, Zhang W, Li G-W, Park J, Blackburn EH, Weissman JS, Qi LS, et al. Dynamic imaging of genomic loci in living human cells by an optimized CRISPR/Cas system. Cell. 2013;155:1479–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, et al. Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Maizels N. Homology-directed repair of DNA nicks via pathways distinct from canonical double-strand break repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:E924–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400236111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deriano L, Roth DB. Modernizing the nonhomologous end-joining repertoire: alternative and classical NHEJ share the stage. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013;47:433–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:E2579–86. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208507109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE. DNA recombination: the replication connection. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde ML, Hazra TK, Mitra S. Early steps in the DNA base excision/single-strand interruption repair pathway in mammalian cells. Cell Res. 2008;18:27–47. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JK, Watson M, Stefanick DF, Shaughnessy DT, Taylor JA, Wilson SH. XRCC1 and DNA polymerase beta in cellular protection against cytotoxic DNA single-strand breaks. Cell Res. 2008;18:48–63. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F. Development and Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasin M, Rothstein R. Repair of strand breaks by homologous recombination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a012740. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F, Han M, Romanienko PJ, Jasin M. Homology-directed repair is a major double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:5172–5177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber MR. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013a;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, Esvelt KM, Moosburner M, Kosuri S, Yang L, Church GM. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013b;31:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell Smith A, Takeuchi R, Pellenz S, Davis L, Maizels N, Monnat RJ, Jr, Stoddard BL. Generation of a nicking enzyme that stimulates site-specific gene conversion from the I-AniI LAGLIDADG homing endonuclease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:5099–5104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810588106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger MJ, Stoddard BL, Monnat RJ., Jr PARP-mediated repair, homologous recombination, and back-up non-homologous end joining-like repair of single-strand nicks. DNA Repair. 2013;12:529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K, Yang Y-G, Pierce AJ, Taniguchi T, Digweed M, D’Andrea AD, Wang Z-Q, Jasin M. Human Fanconi anemia monoubiquitination pathway promotes homologous DNA repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:1110–1115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407796102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce AJ, Jasin M. Measuring recombination proficiency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2005;291:373–384. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-840-4:373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce AJ, Johnson RD, Thompson LH, Jasin M. XRCC3 promotes homology-directed repair of DNA damage in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2633–2638. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier Y, Redon C, Rao VA, Seiler JA, Sordet O, Takemura H, Antony S, Meng L, Liao Z, Kohlhagen G, et al. Repair of and checkpoint response to topoisomerase I-mediated DNA damage. Mutat. Res. 2003;532:173–203. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouet P, Smih F, Jasin M. Expression of a site-specific endonuclease stimulates homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:6064–6068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh-Gohari N, Bryant HE, Schultz N, Parker KM, Cassel TN, Helleday T. Spontaneous homologous recombination is induced by collapsed replication forks that are caused by endogenous DNA single-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:7158–7169. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7158-7169.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Filippo J, Sung P, Klein H. Mechanism of Eukaryotic Homologous Recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:229–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061306.125255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock DM, Richardson CA, Elliott B, Jasin M. Modeling oncogenic translocations: distinct roles for double-strand break repair pathways in translocation formation in mammalian cells. DNA Repair. 2006;5:1065–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Vanoli F, LaRocque JR, Krawczyk PM, Jasin M. Biallelic targeting of expressed genes in mouse embryonic stem cells using the Cas9 system. Methods. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]