Abstract

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory suggests that the quality of the leader–employee relationship is linked to employee psychological health. Leaders who reside at different hierarchical levels have unique roles and spheres of influence and potentially affect employees' work experiences in different ways. Nevertheless, research on the impact of leadership on employee psychological health has largely viewed leaders as a homogeneous group. Expanding on LMX theory, we argue that (1) LMX sourced at the levels of the line manager (LM) and senior management (SM) team will be differentially linked to employee psychological health (assessed as worn-out) and that (2) these relationships will be mediated by perceived work characteristics (reward and recognition, workload management, quality of relationships with colleagues and physical environment). Structural equation modelling on data from 337 manual workers partially supported the hypotheses. Perceptions of the physical environment mediated the relationship between LMX at the LM level and employee psychological health, whereas perceptions of workload management mediated the relationship between LMX at the SM level and psychological health. These findings corroborate arguments that leaders are not a uniform group and as such the effects of LMX on employees will depend on leadership hierarchy. Implications for expanding leadership theory are discussed.

Keywords: Leader-Member Exchange, psychological health, line managers, senior management, work characteristics, worn-out

Introduction

Despite strong evidence for the positive effects of leadership on employees' work experience and psychological health (Kuoppala, Lamminpää, Liira, & Vainio, 2008; Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006; Van Dierendonck, Haynes, Borrill, & Stride, 2004), research in this area has tended to view leadership as one homogeneous group. In their systematic review of 30 years of empirical research, Skakon, Nielsen, Borg, and Guzman (2010) confirmed the position of leadership as an important correlate for employee psychological health. Indeed, as Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory suggests, a positive and high-quality social exchange between managers and employees is vital for a range of individual, group and organizational outcomes (Gerstner & Day, 1997; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Among the range of influences on employee psychological health, the quality of the relationship between an employee and his or her leader(s) is of the utmost importance. Because leaders at different organizational levels also have unique roles and spheres of influence, they can potentially affect employees' work experiences in different ways. The relational perspective has failed to make this distinction. Rather, by viewing leaders as a homogeneous group, LMX implies that all levels of leadership are created equal for employees' work experiences and psychological health.

In this study, we suggest that LMX will apply differently to leaders at different organizational levels. Work organizations are hierarchical systems where leaders at different organizational levels influence employees' work experiences. Because the leader actors in the LMX have different functions and roles (Mintzberg, 1979; O'Dea & Flin, 2003), which can define the nature and quality of their relationships with employees, it cannot be expected that LMX sourced at different levels of leadership would be comparable. Although senior leaders are crucial for promoting adherence to safety procedures (Barling, Loughlin, & Kelloway, 2002), commitment (Hill, Seo, Kang, & Taylor, 2012) and compliance with interventions (Biron, Karanika-Murray, & Cooper, 2012), their role as a source of LMX and relationship with employee psychological health has been overlooked in the leadership literature. The importance of LMX, sourced at different hierarchical levels, for employees' work experiences and psychological health remains understudied.

The aim of the present study is to address this gap. We take a relational perspective, exploring the links among LMX at two levels [relationships with line managers (LMs) and with the senior management (SM) team], sector-specific perceived work characteristics and psychological health in a sample of manual workers in manufacturing. We draw from both leadership more broadly and LMX more specifically. By empirically distinguishing between LMX at two hierarchical levels, we hope to expand the relational perspective and unpack the importance of LMX for employees' work experiences.

The impact of leadership on employee psychological health

Leadership is defined as the “process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal” (Northouse, 2010, p. 3). Leaders influence employees indirectly by shaping their perceptions of the workplace (Tafvelin, Armelius, & Westerberg, 2011) and directly via a more relational route (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). LMX theory suggests that a positive and high-quality social exchange between leaders and employees is vital for promoting desirable individual, group and organizational behavioural and work-related outcomes (Gerstner & Day, 1997) including performance, attendance, satisfaction and commitment (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Not only is leadership directly linked to psychological health outcomes such as well-being (Kelloway, Weigand, McKee, & Das, 2013), but also its impact on employee emotional experiences (e.g., depression, anxiety and tiredness) persists in the long term (Tordera, Peiró, González-Romá, Fortes-Ferreira, & Mañas, 2006).

It is not the aim of this study to dissect the relationships between LMX and specific dimensions of psychological health. Thus, we proceed on the substantiated principle that employees' relationships with their leaders play an important role for their psychological health. Next, we proceed to examine LMX at two hierarchical levels.

LMX is sourced at different levels of leadership

The majority of the research into leadership quality and its impact on employee psychological health has focused predominantly on the LM (e.g., Nielsen, Randall, Yarker, & Brenner, 2008; Yarker, Lewis, & Donaldson-Feilder, 2008; Yarker, Lewis, Donaldson-Feilder, & Flaxman, 2007). This approach is justified because LMs are the “most tangible representative of management actions, policies and procedures” (Kozlowski & Doherty, 1989, p. 547), the most immediate and salient persons in employees' work environment and therefore most likely to directly influence their perceptions and behaviours (O'Driscoll & Beehr, 1994). However, as Dansereau, Yammarino, and Markham (1995) observe, there is a lack of consideration of levels of analysis in leadership research. Because leaders are not one homogeneous group but rather they reside at different hierarchical levels, it is possible that different sources of LMX reflect varying relational quality between leaders and employees. Here, “followers and leaders per se are not of interest; relationships are of most interest” (Dansereau et al., 1995, p. 100). We argue that LMX sourced at higher organizational levels of leadership is equally important for employees as LMX sourced at the LM level.

Two areas of leadership thinking and research support this proposition: leader distance and managerial roles. First, physical/structural distance, perceived psychosocial distance and task interaction frequency can determine employee outcomes (Antonakis & Atwater, 2002). For example, Hill et al. (2012) showed that hierarchical distance (“the number of reporting levels between an employee and the top management team”, p. 758) was inversely related to employees' commitment to change. Similarly, Howell and Hall-Merenda (1999) showed that physical distance moderated the effects of LMX on employee performance. Therefore, leadership distance is relevant to relational content and quality. Second, relational content and quality is influenced by the constraints of the different interacting roles in this relationship. Here we distinguish between LMs as the immediate leaders to whom employees report (Hales, 2005) and SM as referring to the team at higher levels of the organization who hold executive powers and have responsibility for corporate strategy and governance. The leadership literature clearly distinguishes between leadership levels in terms of enacted roles, responsibilities and spheres of influence (Mintzberg, 1979; O'Dea & Flin, 2003). As the role descends in the chain of authority, it “becomes more detailed and elaborated, less abstract and aggregated, more focused on the work flow itself” (Mintzberg, 1979, p. 20). Leaders at senior levels tend to assume more strategic roles with a longer-term impact (e.g., organizational restructuring and strategy or policy formulation), whereas immediate managers or LMs tend to have more operational roles (e.g., structuring, coordinating and facilitating work activities; Mintzberg, 1979; O'Dea & Flin, 2003). Interactions between LM and employees tend to be more immediate and personal whereas communication with SM more formal and structured. Therefore, LMX is contingent upon the specific roles of the actors in a dyadic relationship.

It is important to note that, on the face of it, the fact that SM refers to a group of individuals could preclude a meaningful examination of LMX as a dyadic relationship. The relationship-based approach to leadership suggests that relationships are explained on the basis of behaviours between the interacting individuals (Dachler & Hosking, 1995). We argue that LMX can include groups of individuals with limited one-on-one daily interactions, such as SM and individual employees. The processes that govern dyadic relationships between individuals (e.g., organizational communication and social influence) can also fuel meaningful relationships between individual employees and SM as a group of leaders at higher organizational levels. These relationships can be captured as LMX sourced at the SM level.

In summary, the quality of the relationship between leaders and employees impacts on employee psychological health, and this relationship will hold for leaders at different organizational levels. A separation between leadership levels as different sources of LMX can provide a more elaborate understanding of the link between LMX and employee psychological health.

In the existing literature, employee psychological health has been conceptualized in a range of different ways. Note that although a range of employee outcomes have been studied in the leadership and specifically LMX literatures, the principles that this study reaches on the importance of LMX at different hierarchical levels are more general and apply to a range of indices of psychological health. Here, employee psychological health is conceptualized as well-being and operationalized as its diametrically opposite worn-out (General Well-Being Questionnaire or GWBQ; Cox et al., 1983):

Hypothesis 1a:

LMX sourced at the LM level will be negatively associated with employee feelings of worn-out.

Hypothesis 1b:

LMX sourced at the SM level will be negatively associated with employee feelings of worn-out.

LMX impacts on employees' perceptions of work characteristics

In addition to directly influencing employee psychological health, leaders can also shape employees' perceptions of their work and foster positive appraisals of the workplace (Tafvelin, Armelius, & Westerberg, 2011). The work experience is socially construed on the basis of a range of sources of information available (Griffin, Bateman, Wayne, & Head, 1987), including objective characteristics of their work and information clues provided by the LM (Griffin, 1981; Kozlowski & Doherty, 1989). Therefore, employees' perceptions of their work are coloured by the quality of their relationships with their leaders. LMX will impact on employees' perceptions of their work, specifically in the areas that employees see as being within the leader's roles and responsibilities.

A range of work characteristics experienced by employees across a range of occupations and sectors (e.g., Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006) are possible candidates. Here, we take a bottom-up approach by focusing on work characteristics that have been identified as key in the manufacturing sector, where this study was carried out. These include relationships with colleagues (a positive social environment that can foster positive and supportive interpersonal relationships), reward and recognition (mechanisms to obtain feedback, feel appreciated and feel trusted to make decisions; participation, appreciation, recognition and rewards), workload management issues (opportunities to manage work effectively and feel competent, balancing demands and control) and quality of the physical work environment (availability of more tangible resources to carry out work effectively; Griffiths, Cox, Karanika, Khan, & Tomás, 2006). These mirror some of the global work characteristics identified across occupations but are sector-specific and offer a more focused examination of possible mediators in the relationship between LMX and employee psychological health.

As discussed earlier, more proximal leaders at lower organizational levels tend to attend to operational, day-to-day, relational elements of work, whereas the more distant leaders at senior levels tend to focus on structural, strategic and abstract tasks (Mintzberg, 1979; O'Dea & Flin, 2003). It can be expected that LMX sourced at the LM level will be crucial for employees' perceptions of day-to-day and relational work characteristics, such as expressing appreciation and recognition and influencing relationships at work. Similarly, LMX sourced at the SM level will play a greater role on more structural aspects of work, such as those governed by formal targets, policies and procedures (i.e. configuration of workload, investment in the physical work environment):

Hypothesis 2a:

LMX sourced at the LM level will be positively related to employees' perceptions of work characteristics, specifically reward and recognition, and relationships with colleagues.

Hypothesis 2b:

LMX sourced at the SM level will be positively related to employees' perceptions of work characteristics, specifically workload management, and the physical environment.

Mediating mechanisms between LMX and employee psychological health

To the extent that perceived quality of work is both a product of the expectations and interactions between leaders and employees and an antecedent to employee psychological health (e.g., well-being; see Warr, 2007), it represents a possible mediating link in the relationship between LMX and employee psychological health. Research has supported both direct links between leadership and employee perceptions of their work and indirect influences of leadership on employee outcomes through creating or shaping working conditions (e.g., Kelloway, Sivanathan, Francis, & Barling, 2004). Indeed, working conditions can enhance employee psychological health by allowing employees to experience meaningfulness, responsibility and knowledge of the results of their work (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). It can be expected that employees who have a high-quality LMX with their leaders will perceive their work conditions more positively and, consequently, report better psychological health. Therefore, the influence of LMX sourced at the LM level on employee psychological health will be transmitted through relational aspects of work, whereas the influence of LMX at the SM level on employee psychological health will be transmitted through more structural aspects of work:

Hypothesis 3a:

Perceptions of work characteristics will significantly mediate the relationships between LMX sourced at the LM level and feelings of worn-out.

Hypothesis 3b:

Perceptions of work characteristics will significantly mediate the relationships between LMX sourced at the SM level and feelings of worn-out.

Method

Participants and procedure

All managerial and non-managerial employees in a UK manufacturing organization received a survey, and 640 (65%) returned fully completed questionnaires. The right to withdraw at any time, confidentiality of the data and anonymity of responses were explained to participants. Employees were members of the working group reporting to a LM, whereas LMs were members of a work group reporting to a SM team. To exclude potential self-referent bias, the analyses focused on manual workers who had no managerial responsibilities, resulting in a final sample of 337 maintenance and production operators (335 men, 2 women; age M = 45.41, age range: 19–64 years; tenure M = 20.1 years, range: 1–45 years). This gender distribution is typical in this industry.

Measures

LMX, sourced at the LM and SM levels, was assessed with the 9-item quality of relationships with management scale of the Work Organization Assessment Questionnaire (WOAQ; Griffiths et al., 2006). Respondents were asked to indicate how they felt about their LM and SM in the last six months, on a range of dimensions, on a 5-point Likert response scale (from 1 = unacceptable/major problem to 5 = excellent/very good). The assessment for LMs and the SM team was simultaneous but separate. The scale taps into a range of aspects of the quality of employees' relationships with their LM and SM (e.g., communication, support and feedback) rather than specific styles of leadership. Example items include the following: “making roles and responsibilities clear” and “quality of support from management”. Some of the original items were rephrased to make them applicable to both managerial levels (e.g., “communication with line manager/supervisor” was modified to “communication with management”).

Work characteristics were measured using the remainder four WOAQ scales (Griffiths et al., 2006) on reward and recognition (7 items covering participation, skill utilization, consultation and variety; e.g., “opportunities to use your skills and abilities”), workload management issues (4 items covering work load, work pace and work–life balance; e.g., “how flexible the pace of your workload is”), quality of relationships with colleagues (2 items covering both one-to-one and team relationships; e.g., “how well you get on with your co-workers”) and quality of physical environment (6 items covering equipment, workstation, safety and facilities; e.g., “facilities for taking breaks”). Respondents were asked to indicate how their job had been for them in the last six months on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = unacceptable/major problem to 5 = excellent/very good).

Having been specifically developed for use in the manufacturing sector, the WOAQ was appropriate for this study. The dimensions that the WOAQ covers corresponds with the core work characteristics typically reported (across all occupations and sectors; e.g., Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006; Warr, 2007) but are specific to this sector and therefore more appropriate to use in the present study. Because context-specific assessment is important (Sparks & Cooper, 1999), the use of specific rather than generic tools is more appropriate. For all WOAQ scales, research has shown high levels of internal reliability (Cronbach's α > .80; Spearman–Brown coefficients > .80; and mean inter-item correlations > .40) and satisfactory levels of test–retest reliability (r between .60 and .90, p ≤ .01) and split-half reliability (Guttman split-half reliability coefficients ≥ .80). The WOAQ predicts job satisfaction, tension, exhaustion, psychological distress and physical health (see Griffiths et al., 2006).

Employee psychological health was measured by the short version of the GWBQ (Cox et al., 1983). The 12-item scale measures worn-out and consists of symptoms of general malaise which are not clinically significant in themselves. Respondents were asked to rate the frequency of occurrence of a list of symptoms (related to aspects of behavioural, emotional and cognitive functioning; e.g., “have you had difficulty in falling or staying asleep”) in the last six months. Responses were on a 5-point scale (0 = never to 4 = all the time), with higher scores indicating poorer well-being or higher feelings of worn-out. The short version of the GWBQ has good internal consistency with Cronbach's α at .90 (Cox & Griffiths, 2005). Scores on all scales were calculated by summing the scores on the relevant items.

Analytical procedure

The data were analysed via structural equation modelling (SEM) using Mplus version 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998/2012). All analyses were carried out using maximum likelihood estimations. The degree of model fit was evaluated using multiple fit indices. A non-significant chi-square is considered indicative of adequate model fit. However, the chi-square is also known to be affected by sample size (Hu & Bentler, 1999). As such, a number of fit indices were used to determine whether the hypothesized model accurately represented the data. The comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were chosen as indicators of incremental fit. Although values indicative of acceptable model fit remain controversial (Marsh, Hau, & Wen, 2004), it is typically accepted that CFI and TLI values exceeding .90 and .95 are indicative of acceptable and excellent fit, respectively. The Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) were chosen as indicators of absolute fit. SRMR values of ≤.08 and RMSEA values ≤.06 represent good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

In line with the frequently advocated two-step approach to SEM (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988), the fit of the measurement model was examined prior to testing the hypothesized structural model (Model 1). Mediation analyses of the effects of LMX sourced at the LM and SM levels on worn-out via perceptions of work characteristics (i.e., reward and recognition, workload management, relationships with colleagues and the physical environment) were subsequently performed following the recommendations of MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, and Sheets (2002) and Preacher and Hayes (2008). Initially, competing models were tested to determine whether there was evidence of an overall mediation effect in our hypothesized model (Holmbeck, 1997; Williams, Vandenberg, & Edwards, 2009). Specifically, three models were estimated: a direct effects model (Model 2), a full mediation model (Model 1) and a partial mediation model (Model 3). It has been argued, however, that Baron and Kenny's (1986) causal steps method of testing mediation merely probes, rather than fully explicates, the relationship of an independent variable to a dependent variable via a mediating variable (MacKinnon & Fairchild, 2009). The causal steps approach has also been criticized for having limited applications to multiple mediation models as it is not possible to tease out the independent intervening effect of each mediator (Hayes, 2009). Simulation research has shown that bootstrapping is a superior method for testing intervening variable effects and should be used instead of the causal steps approach (Hayes, 2009; MacKinnon et al., 2002). Bootstrapping can generate a bias-corrected confidence interval (CI) and, as a consequence, inferences can be made about the significance of the indirect effect in the population sampled if zero is not between the lower bound and the upper bound intervals of the 95% CI. After the three competing models were analysed to test whether an overall mediation effect was present (Holmbeck, 1997; Williams et al., 2009), the recommendations of MacKinnon (2000) were followed to ascertain the significance and magnitude of the specific mediated effect via each work characteristic.

Results

Table 1 presents the means (M), standard deviations (SD), inter-correlations between variables (r), Cronbach's α reliability coefficients and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for the study variables. Cronbach's α coefficients ranged from .62 to .92. Two of the scales had α < .70, which was initially a cause for concern (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). However, it should be noted that the α coefficient depends on the number of items in a scale and is biased against scales with fewer items. As an alternative measure of reliability, AVE was calculated by subtracting the mean correlations from the square root of the variance for each construct, and AVE levels needed to exceed .50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) for scales to be satisfactory. For the scales with a Cronbach's α below .70 (i.e., workload management and relationships with colleagues), all AVE values were > .50 (ranging from .97 to 7.58).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, AVE values and zero-order correlations.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. LMX sourced at the LM level | 25.68 | 7.13 | (.92) | ||||||

| 2. LMX sourced at the SM level | 23.78 | 6.81 | .71** | (.91) | |||||

| 3. Reward and recognition | 18.99 | 3.97 | .64* | .57* | (.75) | ||||

| 4. Workload management | 11.00 | 2.42 | .34* | .32* | .46* | (.67) (2.03)a | |||

| 5. Relationships with colleagues | 7.50 | 1.51 | .30* | .23* | .30* | .15* | (.62) (0.97)a | ||

| 6. Physical environment | 16.47 | 3.49 | .45* | .42* | .57* | .50* | .20* | (.71) | |

| 7. Worn-out | 16.96 | 7.86 | −.22* | −.23* | −.29* | −.32* | −.15* | −.33** | (.86) |

Note: N = 337; Cronbach's α values for each scale are shown in the first parentheses on the diagonal.

LM, line manager; SM, senior management.

Analysis of Variance Extracted (AVE) for workload management issues and relationships with colleagues is shown in the second parenthesis.

*p ≤ .01; **p ≤ .001.

As expected, LMX at the LM and SM levels was positively and significantly correlated with all work characteristics (r = .23 to .64, p ≤ .001). Furthermore, worn-out was significantly correlated with LMX at LM (r = –.22, p ≤ .001) and at SM (r = –.23, p ≤ .001) and with all work characteristics (r = –.15 to –.33, p ≤ .01). Because age and tenure were not correlated with the predictor or outcome variables, they were not included in the models.

Testing the measurement and structural models

All constructs were tested as latent variables. To increase the stability of the parameter estimates and improve the ratio of sample size to estimated parameters (Bagozzi & Edwards, 1998), construct-specific parcels were created for all latent variables with the exception of workload management and relationships with colleagues, which were indexed by four and two items in each of these subscales, respectively. Little, Cunningham, Shahar, and Widaman's (2002) discussions of the pros and cons of parcelling were incorporated in the parcelling methods used. For instance, Little et al. (2002) have argued that parcelling would not be appropriate for a latent variable with only two indicator items, which is why parcelling was not used for the relationships with colleagues subscale. Each parcel represented unweighted averaged scores created by pairing stronger with weaker loading items from the same scale. The use of this factorial algorithm (Rogers & Schmitt, 2004) ensures that all parcels are equally balanced in terms of their difficulty and discrimination (Williams et al., 2009). Subsequently, the measurement model was tested to evaluate whether the parcelled indicators loaded onto their respective latent constructs. A satisfactory fit was evident: χ 2(250) = 442.66, p < .001, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, SRMR = .05, RMSEA = .05 (95% CI: 0.04–0.06).

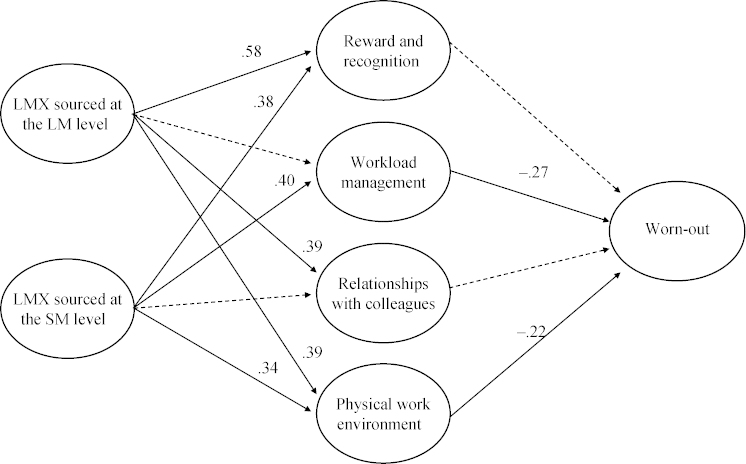

The proposed structural model (Model 1) also demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data: χ 2(258) = 548.92, p < .001, CFI = .94, TLI = .93, SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .06 (95% CI: 0.05–0.07). The standardized path coefficients are presented in Figure 1. With the exception of the pathways between SM and relationships with colleagues, and LM and workload management, employees' perceptions of LMX significantly predicted perceptions of work characteristics. Specifically, and in line with H2a, LMX at the LM level was strongly and positively associated with reward and recognition (β = .58, p < .001) and relationships with colleagues (β = .39, p < .001). A significant but weaker relationship was also observed between SM and rewards and recognition (β = .38, p < .001). Furthermore, LMX at the SM level did not significantly predict relationships with colleagues (β = .12, p = .301). In line with H2b, LMX at the SM level strongly and positively predicted perceptions of workload management (β = .40, p < .001) and LMX at the LM level did not (β = .20, p = .086). However, in contrast to H2b, LM (β = .39, p < .001) proved to be a slightly stronger predictor of the physical work environment in comparison to SM (β = .34, p < .001). In turn, perceptions of workload management (β = –.27, p = .012) and the physical environment (β = –.22, p = .050) significantly predicted employee worn-out. Non-significant pathways were observed between reward and recognition (β = –.02, p = .900) and relationships with colleagues (β = –.13, p = .194) and worn-out. Together, LMX with the LM and SM accounted for 78% of the variance in perceptions of reward and recognition, 31% of the variance in perceptions of workload management, 23% of the variance in perceptions of their relationships with colleagues and 46% of the variance in perceptions of the physical environment. In turn, employees' perceptions of these work characteristics explained 21% of the variance in employee worn-out. All R 2 values were statistically significant (p < .01).

Figure 1. Structural model of associations between perceived LMX sourced at the line manager (LM) and senior management (SM) levels, work characteristics and worn-out.

Note: Coefficients shown are standardized path coefficients. Dotted lines represent non-significant parameters. Correlation between LM and SM, r = .71.

Mediation analyses

The mediational effects in the hypothesized model were tested following the SEM approach advanced by Holmbeck (1997). First, we tested a model estimating the direct paths from the independent variables to the outcome variable (Model 2). The model specifying direct associations between LMX with the LM and SM and well-being demonstrated an excellent fit to the data: χ 2(47) = 81.81, p = .001, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, SRMR = .04, RMSEA = .05 (95% CI: 0.03–0.06). However, an examination of the standardized path coefficients reveals only partial support for H1. As expected, a direct relationship was observed between LMX at the SM level and worn-out (β = –.18, p = .036; H1b). In contrast, employees' perceptions of LMX sourced at the LM level did not significantly influence worn-out (β = –.14, p = .103; H1a). If the independent variable does not predict the criterion, the mediator cannot be said to account for this association (Holmbeck, 1997). Thus, whilst there may still be evidence of an indirect effect, a condition required for mediation per se has been violated.

The next step in testing mediation would be to confirm the fit of the constrained, full mediation, model (see Model 1 outlined above). According to Holmbeck (1997), significant paths should be evident between the independent variables and the mediators and the mediators and the outcome variables. This condition was satisfied in the significant relationships represented in Figure 1. Specifically, in relation to H3, the findings supported the proposed pathways between the independent variables and the mediators in that LMX at the LM level was positively related to employees' perceptions of rewards and recognition and relationships with colleagues (H3a), and LMX with the SM was positively related to employees' perceptions of workload management and the physical environment (H3b). However, only employees' perceptions of workload management and the physical environment significantly predicted employee worn-out. As such, no significant specific indirect effects were expected via rewards and recognition or relationships with colleagues. The final step was to examine an unconstrained model specifying partial mediation (Model 3). Thus direct paths were added from LMX at the LM level and LMX at the SM level to worn-out. The model demonstrated an adequate fit to the data: χ 2(256) = 548.36, p < .001, CFI = .94, TLI = .92, SRMR = .07, RMSEA = .06 (95% CI: 0.05–0.07). A chi-square difference test was performed between the constrained model (Model 1) and the unconstrained model (Model 3). The chi-square difference test indicated no difference between the two models (Δχ 2(2) = .56, p > .05). That is, the hypothesized model was not significantly improved by adding the direct pathways between LMX with the LM and LMX with SM to employee worn-out. The fact that the unconstrained model did not offer an advanced representation of the data suggests that the full mediation model provided the most parsimonious representation of the data (Holmbeck, 1997; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Furthermore, LMX with the SM no longer significantly predicted worn-out as it did in Model 2 when the four mediating work characteristics were included in the unconstrained model (β = .03, p = .822).

Subsequently, the indirect effects of LMX at the LM and SM levels on employee worn-out via characteristics of the workplace were explored and these are presented in Table 2. An examination of the total indirect effects revealed that, as hypothesized, work characteristics significantly mediated the negative relationship between LMX and worn-out (H3). Specifically, providing partial support for H3b, employees' perceptions of workload management significantly mediated the relationship between LMX with the SM and employee psychological health (β = –.11, p = .025). However, the indirect effect via employees' perceptions of the physical environment was not significant (β = –.08, p = .396). Instead, an unexpected significant indirect effect was observed via employees' perceptions of the physical environment in the relationship between LMX at the LM level and worn-out (β = –.09, p = .051). In contrast to H3b, indirect effects via employees' perceptions of rewards and recognition (β = –.01, p = .900) and relationships with colleagues (β = –.05, p = .168) were not significant. Given that neither potential mediator predicted employee worn-out, this finding was not unexpected.

Table 2. Indirect effects of LM and SM levels on worn-out via reward and recognition, workload management, relationships with colleagues and physical environment.

| Specific indirect effect (95% CI) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | Criterion Variable | Total indirect effect (95% CI) | Reward and recognition | Workload Management | Relationships with colleagues | Physical environment |

| LMX sourced at the LM level | Worn-out | −.18 (−.30 to −.07)* | .01 (−.13 to .15) | −.06 (−.14 to .03) | −.05 (−.13 to .02) | −.09 (−.18 to −.01)* |

| LMX sourced at the SM level | Worn-out | −.19 (−.34 to −.09)* | .01 (−.09 to .10) | −.11 (−.21 to −.01)* | −.02 (−.05 to .02) | −.08 (−.17 to .02) |

Note: Standardized beta coefficients are presented with biased corrected 95% CI.

LM, line manager; SM, senior management.

*p ≤ .05.

Discussion

The quality of the relationship between an employee and his or her leader(s), is one of the major influences on employee psychological health, here measured as worn-out. Consistent with previous work, our findings highlight the role of the leader for psychological health (e.g., Nielsen et al., 2008; Skakon et al., 2010; Van Dierendonck et al., 2004) and provide support for the mediating role of perceived work characteristics (e.g., Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006). Expanding on past work, we have argued for differential effects of leadership levels and provided support for the proposition that LMX sourced at two hierarchical levels has differential effects on employees' work experiences and psychological health.

As expected, a direct relationship between LMX and employee psychological health (measured as worn-out and with the short form of the GWBQ) was observed, but only for LMX sourced at the SM level, therefore providing partial support for Hypothesis 1. In addition, LMX was associated with employee perceptions of work characteristics; specifically, LMX sourced at the LM level was positively associated with relational work characteristics (reward and recognition and relationships with colleagues), whereas LMX sourced at the SM level was linked to perceptions of more structural work characteristics (workload management and the physical work environment), providing support for Hypothesis 2. Unexpectedly, however, strong relationships were observed between LMX at the LM level and physical work environment, and between LMX at the SM level and reward and recognition. Finally, in partial support of Hypothesis 3, perceptions of workload management mediated the relationship between LMX with the SM and employee psychological health. Unexpectedly, perceptions of the physical work environment mediated the effects of LMX with the LM on worn-out. No other significant indirect effects were observed.

The development of a high-quality leader–employee relationship, with its ensuing benefits, relies on proximity and trust between the leader and the employee (Shamir, 1995). Proximity provides opportunities for interaction and communication, aids day-to-day management (Avolio, Zhu, Koh, & Bhatia, 2004), facilitates effective working (Howell & Hall-Merenda, 1999) and boosts commitment (Avolio et al., 2004). Proximity or distance can take many forms (Antonakis & Atwater, 2002). In the present study, proximity was implicitly operationalized as structural or functional, on account of the definition of the two leadership levels. Unexpectedly, LMX sourced at one leadership level was also linked with work characteristics expected to be in the realm of the other leadership level. Thus, it is possible that psychosocial rather than structural distance may explain the links between LMX sourced at the LM level with physical work environment and between SM and reward and recognition in this sample. Further exploration of how different aspects of distance (physical, social or interaction frequency) and hierarchical leadership levels will provide insights into the proximity conditions for the effects of LMX.

Additionally, LMX sourced at both LM and SM levels influenced two of the four work characteristics. The finding that the relationships between LMX at different hierarchical levels and work characteristics were not unique and distinct, as expected, could be explained by Mintzberg's (1979) work on managerial roles. Mintzberg argued that both leaders (here, the SM) and managers (here, LM) enact similar roles but to different degrees. Thus, although LM tend to control relational/interactional functions, whereas SM have more influence on structural functions (e.g., higher-level strategic planning and initiating structure), leaders at different seniority levels can, to some extent, fulfil both relational and structural functions (Mintzberg, 1979). For this reason, it is possible that reward and recognition and the physical work environment are influenced predominantly but not exclusively by one leadership level. The role boundaries between different leadership levels are not fixed and inflexible, at least in some organizations.

Furthermore, regardless of a leader's defined sphere of influence and power in relation to objective work characteristics, leaders also influence employees' perceptions of their work (O'Driscoll & Beehr, 1994). Via one-on-one or one-on-many actions and interactions, LMXs impact on employees' work experiences. Indeed, the safety literature suggests that SM establishes safety rules (Janssens, Brett, & Smith, 1995), whereas LMs ensure employees adhere to these rules. Furthermore, not only has SM the power to make strategic decisions, for example about configurations of the physical work environment, but also LMs act as SM's representatives (cf. Kozlowski & Doherty, 1989). Therefore, the process by which LM and SM influence employees and the role of LMX in this relationship is complex and worth considering in detail in future research. Not only that but greater specificity in understanding how the observed relationships apply to different indices of psychological health (e.g., positive and negative affect, job satisfaction or burnout) would also add to our understanding of the role of LMX at different hierarchical levels.

Most importantly, by unpacking our understanding of the types of actors who can take part in a dyadic relationship, the present study offers new perspectives for expanding LMX theory. In support of existing literature, quality social exchange between leaders and employees was found to be important for employee outcomes (Gerstner & Day, 1997). We expand on Dansereau et al.'s (1995) observation that “followers and leaders per se are not of interest; relationships are of interest” (p. 100) by suggesting that we can include groups of individuals as the actors in this exchange and, specifically, that the source of LMX is important for employee outcomes. Here, relationships are explained as behaviours not between interacting individuals (Dachler & Hosking, 1995) but between interacting groups whose interactions are governed by the same rules that govern dyadic relationships. Describing LMX as a dyadic relationship should not preclude groups of individuals in this dyadic relationship.

These findings also hint to possibilities to blend different areas of leadership research including roles, trust, leader distance, shared leadership and LMX. Although we drew from these different literatures to examine the links between LMX, hierarchical levels of leadership and employee psychological health, it would have been beyond the purposes of this study to fuse perspectives further. Future conceptual and empirical work can achieve a more detailed understanding and integration of these perspectives and further expansion of LMX theory.

Our findings also showed that perceptions of the physical work environment mediated the influence of LMX sourced at the LM level, whereas workload management mediated the influence of LMX sourced at the SM level. The former was unexpected but, in light of the above discussion on leader roles and spheres of influence, not surprising. Manufacturing is one of the most hazardous industrial sectors (Roberts, 2002). Considering manual work in manufacturing, the SM sets the targets and decisions regarding pace of work, shiftwork and, to an extent, work–life balance. LM, on the other hand, can impact on workers' interpretation of harsh and often hazardous working conditions.

On this observation, it is important to put the present findings in their broader occupational context. The current study examined psychological health within a well-defined population of manual workers in the UK division of a large international manufacturing organization. Manual work is a demanding occupation (e.g., Cherry, 1978). Compared to other occupations, manual workers have high levels of mental and physical health and sickness absence. Corroborating findings on the mental and physical health of manual workers (e.g., Cooper & Bramwell, 1992), in the study organization, 27.8% of manual workers smoked (compared to 13.5% of salaried staff). Bullying is also prevalent among manual workers, of whom 14.8% reported having been intimidated (harassed, assaulted or bullied) at work in the past six months (compared to 9.4% of salaried staff). Manual workers and salaried staff also differed in tenure (M = 20.1 and M = 18.3 years, respectively), gender composition (99.5% and 91.7% males, respectively) and working a shiftwork pattern (71.0% and 22.9%, respectively). Furthermore, this organization's structure is decentralized; strong leader–employee communication and SM interaction with manual workers at the site level are valued. Understanding the role of LMX for this occupational group's work experiences is important.

It is also important to note that in this study leadership levels were considered not methodologically, by taking a multi-level analytical approach to separating between individual- and group-level effects, but in terms of sources of LMX as referents for employees' work experiences. An invaluable avenue for future research would be to methodologically differentiate between levels of leadership and LMX in order to proportion the variance in the target outcome that can be explained by leadership levels. As Klein, Dansereau, and Hall (1994) argue, “greater attention to levels issues will increase the clarity, testability, comprehensiveness, and creativity of organizational theories” (p. 224). This study provided a useful theory-grounded starting point in this endeavour.

In contrast to past research (e.g., Van Dierendonck et al., 2004), and despite correlations of similar magnitude, our SEM findings showed that the quality of the relationship with the SM, but not with the LM, had a direct effect on employee worn-out. Distinguishing between the two levels of leadership possibly allowed to distinguish between LM's and SM's roles and responsibilities, also indicating the referent for employees' perceptions of their work.

The findings suggest a range of practical implications. In some countries, national guidance for managing psychosocial issues at the workplace has been developed (e.g., in Great Britain and more recently in Canada), supplemented by LM competencies (e.g., Yarker et al., 2007, 2008). Inadvertently in practice, and perhaps due to limited understanding of the differential effects of hierarchical leadership levels on employee outcomes, a disproportionately larger part of responsibility for managing employee psychological health aspects such as stress and well-being tends to be allocated to the immediate LM. This could, at best, filter out invaluable resources and, at worst, be counter-productive. It is important to (1) promote an understanding of how leadership levels impact on perceptions of work, (2) redress the balance of responsibility across different leader seniority levels and (3) make optimal use of resources when developing interventions to promote employee psychological health, along the core concepts relating to LMX, roles and responsibilities, and distance or leadership levels. Understanding how to optimize the work experience is ongoing, and we hope to have contributed a little stone to this quest by providing support for the important role of LMX and suggesting ways forward for research.

The present findings should be interpreted with the requisite caution. First, this cross-sectional self-report study provided proof of concept but did not seek to establish causal inferences. Reciprocal causation from work characteristics to perceptions of LMX is possible (e.g., Nielsen et al., 2008) and worth exploring. In addition, common method variance may have affected the results, and therefore, future research should further test the validity of the model by adopting a longitudinal approach and using objective measures (e.g., physiological indicators of employee psychological health). Second, because employees are nested within workgroups that correspond to individual LMs, who may, in turn, be nested within SMs, a multi-level examination would be relevant. In the present study, it was not possible to take a multi-level approach because the number of workgroups was small, and it was not possible to match respondents to their LMs. Third, it is important to note that the relationships between leadership levels and work characteristics only apply to the specific organizational context and industrial sector from which the data were gathered. For example, the flat hierarchy and active encouragement of SM visibility observed in this organization is not necessarily a reality in other organizations, potentially restricting the generalizability of the findings to more hierarchical organizations. Similarly, the male-dominated sample is a characteristic of the workforce in this sector but not in others, providing another limitation to this study. Nevertheless, there is no reason to question the finding that LMX sourced at different hierarchical leadership levels can have differential impact on employee psychological health and their perceptions of their work.

Conclusions

It is hoped that these findings can contribute to further research to help enrich our appreciation of the impact of LMX on employee psychological health, specifically by identifying the sources of LMX. Consistent with previous work, this study highlights the role of leadership for employee's work experience and provides support for the mediating role of work characteristics in this relationship. By drawing on leaders' different spheres of influence, this study also sheds light on the role of the senior management team for employee psychological health and highlights the distinct but concurrent influences of LMX sourced at different hierarchical levels. From the employees' perspective, the quality of their relationship with leaders at different seniority levels is not uniform. The role of LMX at two hierarchical levels for employee psychological health should not be neglected, at least in some organizations.

Acknowledgements

The original research was carried out whilst the first and last authors were affiliated with the University of Nottingham.

References

- Anderson J. C., Gerbing D. W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988:411–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonakis J., Atwater L. Leader distance: A review and a proposed theory. Leadership Quarterly. 2002:673–704. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00155-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avolio B. J., Zhu W., Koh W., Bhatia P. Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2004:951–968. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R. P., Edwards J. R. A general approach for representing constructs in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 1998;(1):45–87. doi: 10.1177/109442819800100104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barling J., Loughlin C., Kelloway E. K. Development and test of a model linking safety-specific transformational leadership and occupational safety. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002:488–496. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. M., Kenny D. A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron C., Karanika-Murray M., Cooper C. Improving organizational interventions for stress and well-being: Addressing process and context. London: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry N. Stress, anxiety and work: A longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational Psychology. 1978:259–270. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1978.tb00422.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C. L., Bramwell R. S. A comparative analysis of occupational stress in managerial and shopfloor workers in the brewing industry: Mental health, job satisfaction and sickness. Work & Stress. 1992:127–138. doi: 10.1080/02678379208260347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox T., Griffiths A. The nature and measurement of work-related stress: Theory and practice. In: Wilson J. R., Corlett N., editors. Evaluation of human work. 3rd Ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2005. pp. 553–572. [Google Scholar]

- Cox T., Thirlaway M., Gotts G., Cox S. The nature and assessment of general well-being. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1983:353–359. doi: 10.1016/0022--3999(83)90066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dachler H. P., Hosking D. M. The primacy of relations in socially constructing organizational realities. In: Hosking D. M., Dachler H. P., Gergen K. J., editors. Management and organization: Relational alternatives to individualism. Burlington, VT: Ashgate/Avebury; 1995. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dansereau F., Yammarino F. J., Markham S. E. Leadership: The multiple-level approaches. The Leadership Quarterly. 1995:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;(1):39–850. doi: 10.2307/3151312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstner C. R., Day D. V. Meta-analytic review of Leader-Member Exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1997:827–844. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.82.6.827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graen G. B., Uhl-Bien M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly. 1995:219–247. doi: 10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin R. W. Supervisory behaviour as a source of perceived task scope. Journal of Occupational Psychology. 1981:175–182. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1981.tb00057.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin R. W., Bateman T. S., Wayne S. J., Head T. C. Objective and social factors as determinants of task perceptions and responses: An integrated perspective and empirical investigation. Academy of Management Journal. 1987:501–523. doi: 10.2307/256011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A., Cox T., Karanika M., Khan S., Tomás J. M. Work design and management in the manufacturing sector: Development and validation of the Work Organization Assessment Questionnaire. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2006:669–675. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.023671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman J. R., Oldham G. R. Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hales C. Rooted in supervision, branching into management: Continuity and change in the role of first-line manager. Journal of Management Studies. 2005:471–506. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009:408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill N. S., Seo M.-G., Kang J. H., Taylor M. S. Building employee commitment to change across organizational levels: The influence of hierarchical distance and direct managers' transformational leadership. Organization Science. 2012:758–777. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997:599–610. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell J. M., Hall-Merenda K. The ties that bind: the impact of leader-member exchange, transformational and transactional leadership, and distance on predicting follower performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1999:680–694. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.5.680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens M., Brett J. M., Smith F. J. Confirmatory cross-cultural research: Testing the viability of a corporation-wide safety policy. Academy of Management Journal. 1995:364–382. doi: 10.2307/256684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway E. K., Sivanathan N., Francis L., Barling J. Poor leadership. In: Barling J., Kelloway E. K., Frone M., editors. Handbook of workplace stress. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway K. E., Weigand H., McKee M. C., Das H. Positive leadership and employee well-being. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 2013:107–117. doi: 10.1177/1548051812465892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein K. J., Dansereau F., Hall R. J. Levels issues in theory development, data collection and analysis. Academy of Management Review. 1994:195–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski S. W. J., Doherty M. L. Integration of climate and leadership: Examination of a neglected issue. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1989:546–55. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.74.4.546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuoppala J., Lamminpää A., Liira J., Vainio H. Leadership, job well-being, and health effects – A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2008:604–915. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31817e918d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little T. D., Cunningham W. A., Shahar G., Widaman K. F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002:151–173. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P. Contrasts in multiple mediator models. In: Rose L., Chassin C., Presson C. C., Sherman S. J., editors. Multivariate applications in substance use research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Fairchild A. J. Current directions in mediation analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009:16–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Lockwood C. M., Hoffman J. M., West S. G., Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H. W., Hau K., Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler's (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004:320–341. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg H. The structuring of organizations: A synthesis of the research. Englewood Hills, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Morgeson F. P., Humphrey S. E. The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006:1321–1339. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. Mplus user's guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998/2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K., Randall R., Yarker J., Brenner S. O. The effects of transformational leadership on followers' perceived work characteristics and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. Work & Stress. 2008:16–32. doi: 10.1080/02678370801979430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse P. Leadership: Theory and practice. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally J. C., Bernstein I. H. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- O'Dea A., Flin R. The role of managerial leadership in determining workplace safety states. Sudbury: HSE Books; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll M., Beehr T. Supervisor behaviours, role stressors and uncertainty as predictors of personal states for subordinates. Journal of Organizational Behaviour. 1994:141–155. doi: 10.1002/job.4030150204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo R. F., Colquitt J. A. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal. 2006:327–340. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2006.20786079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Hayes A. F. Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In: Hayes A. F., Slater M. D., Snyder L. B., editors. The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Thousand Oaks: CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. E. Hazardous occupations in Great Britain. The Lancet. 2002:543–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09708-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers W. M., Schmitt N. Parameter recovery and model fit using multidimensional composites: A comparison of four empirical parceling algorithms. Multivariate Behavioural Research. 2004:379–412. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3903_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir B. Social distance and charisma: Theoretical notes on an explanatory study. Leadership Quarterly. 1995:19–47. doi: 10.1016/1048-9843(95)90003-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skakon J., Nielsen K., Borg V., Guzman J. Are leaders' well-being, behaviours and style associated with the affective well-being of their employees? A systematic review of three decades of research. Work & Stress. 2010:107–139. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2010.495262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks K., Cooper C. L. Occupational differences in the work-strain relationship: Towards the use of situation-specific models. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 1999:219–229. doi: 10.1348/096317999166617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tafvelin S., Armelius K., Westerberg K. Toward understanding the direct and indirect effects of transformational leadership on well-being a longitudinal study. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 2011:480–492. doi: 10.1177/1548051811418342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tordera N., Peiró J. M., González-Romá V., Fortes-Ferreira L., Mañas M. A. Leaders as health enhancers: A longitudinal analysis of the impact of leadership in team members' well-being; Paper presented at the 26th International Congress of Applied Psychology (pp. 16–21); Athens, Greece. 2006. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Van Dierendonck D., Haynes C., Borrill C., Stride C. B. Leadership behaviour and subordinate well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2004:165–175. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.9.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr P. Work, happiness and unhappiness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Williams L. J., Vandenberg R. J., Edwards J. R. Structural equation modelling in management research. A guide for improved analysis. Academy of Management Annals. 2009:543–604. doi: 10.1080/19416520903065683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yarker J., Lewis R., Donaldson-Feilder E. Management competencies for preventing and reducing stress at work: identifying the management behaviours necessary to implement the management standards: phase two. Bootle: Health and Safety Executive. (Research Report, no. RR633); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yarker J., Lewis R., Donaldson-Feilder E., Flaxman P. Management competencies for preventing and reducing stress at work: Identifying and developing the management behaviours necessary to implement the HSE Management Standards. Bootle: Health and Safety Executive; 2007. Research Report, no. RR553. [Google Scholar]