Abstract

The present studies used increased atmospheric pressure in place of a traditional pharmacological antagonist to probe the molecular sites and mechanisms of ethanol action in GlyRs. Based on previous studies, we tested the hypothesis that physical-chemical properties at position 52 in extracellular domain Loop 2 of α1GlyRs, or the homologous α2GlyR position 59, determine sensitivity to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol. Pressure antagonized ethanol in α1GlyRs that contain a non-polar residue at position 52, but did not antagonize ethanol in receptors with a polar residue at this position. Ethanol sensitivity in receptors with polar substitutions at position 52 was significantly lower than GlyRs with non-polar residues at this position. The α2T59A mutation switched sensitivity to ethanol and pressure antagonism in the WTα2GlyR, thereby making it α1-like. Collectively, these findings indicate that: 1) polarity at position 52 plays a key role in determining sensitivity to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol; 2) the extracellular domain in α1- and α2GlyRs is a target for ethanol action and antagonism and 3) there is structural-functional homology across subunits in Loop 2 of GlyRs with respect to their roles in determining sensitivity to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol. These findings should help in the development of pharmacological agents that antagonize ethanol.

Keywords: Increased atmospheric pressure, two-electrode voltage clamp, ethanol sites of action, Xenopus oocytes, ion channels, glycine receptor

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol (ethanol) abuse represents a major problem in the United States with an estimated 14 million people being affected (Grant et al. 2004). To address this issue, considerable attention has begun to focus on the development of medications to prevent and treat alcoholism (Heilig M. and Egli M. 2006;Steensland et al. 2007;Johnson et al. 2007). The development of such medications would be aided by a clear understanding of the sites and mechanisms of ethanol action.

Traditionally, the mechanisms and sites of drug action are studied using the appropriate receptor agonists and antagonists. To be used in this way, the mechanism of the antagonism must be direct (mechanistic not physiological) and selective. When these criteria are met, the site of antagonism is synonymous with and defines the site causing drug action. However, the physical-chemical mechanism of action as well as the low affinities of ethanol for its targets limit the utility of traditional pharmacological receptor agonist and antagonist ligands as tools for investigating ethanol’s sites of action (Eckenhoff and Johansson 1997;Davies et al. 2003).

Prior studies indicate that increased atmospheric pressure (pressure) is an ethanol antagonist that can help fill this gap. This work found that low level hyperbaric exposure (pressure up to twelve times normal atmospheric pressure—12 ATA) directly antagonizes the behavioral and biochemical actions of ethanol (Alkana and Malcolm 1981;Alkana et al. 1992;Bejanian et al. 1993;Davies and Alkana 1998;Davies and Alkana 2001). The antagonism occurred without causing changes in baseline behavior or central nervous system excitation (Syapin et al. 1988;Davies et al. 1994;Davies et al. 1999) that called into question the direct mechanism of earlier studies investigating high pressure reversal of anesthesia (Kendig 1984;Bowser-Riley et al. 1988;Wann and MacDonald 1988;Franks and Lieb 1994;Little 1996). The low level hyperbaric studies also demonstrated that pressure was selective for allosteric modulators (Alkana et al. 1995;Davies et al. 1996;Davies et al. 2003). More recent hyperbaric two-electrode voltage clamp studies demonstrated that pressure antagonized ethanol potentiation of α1 Glycine receptor (GlyR) function in a direct, reversible, concentration and pressure dependent manner that was selective for allosteric modulation by alcohols (Davies et al. 2003;Davies et al. 2004). Taken together, these findings indicate that pressure is a direct, selective ethanol antagonist that can be used, in place of a traditional pharmacological antagonist, as a tool to help identify the sites of ethanol action.

This notion is supported by recent studies using pressure to identify novel targets for ethanol in GlyRs. Glycine is a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system. GlyRs are a member of the superfamily of ligand-gated ion channels (LGICs), known as Cys-loop receptors (Ortells and Lunt 1995;Karlin 2002). Other members of this receptor family include γ-aminobutyric acid type-A receptor (GABAAR), nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) and 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor (5HT3R), all of which assemble to form ion channels with a pentameric structure (Schofield et al. 1987). Glycine causes inhibition in the adult central nervous system by activating the strychnine-sensitive GlyR. Five GlyR subunits have been cloned (α1 – α4 and β). The pentamer formed can be homo- or heteromeric (Betz 1991;Rajendra et al. 1997). Native adult GlyRs contain both α1 and β subunits, while native neonatal GlyRs contain both α2 and β subunits ((Malosio et al. 1991;Mascia et al. 1996a;Rajendra et al. 1997;Eggers et al. 2000)

Studies over the last decade have pointed to a role for GlyRs in mediating the effects of ethanol. This work includes studies that have shown that behaviorally relevant concentrations of ethanol positively modulate GlyR function measured in a variety of brain and spinal cord preparations (Engblom and Åkerman 1991;Aguayo and Pancetti 1994;Tapia et al. 1998;Eggers et al. 2000;Tao and Ye 2002;Ye et al. 2002;McCool et al. 2003;Ziskind-Conhaim et al. 2003). More recent studies also suggest that GlyRs in the nucleus accumbens are targets for ethanol that are involved in ethanol-induced mesolimbic dopamine release (Molander and Söderpalm 2005;Molander et al. 2007), thus linking GlyRs to the rewarding effects of ethanol.

The molecular targets and mechanisms that initiate ethanol action in GlyRs represent an active area of investigation (Mascia et al. 1996a;Mihic et al. 1997;Valenzuela et al. 1998;Ye et al. 2002;Davies et al. 2004;Yevenes et al. 2006;Crawford et al. 2007;Lobo et al. 2007). Considerable research has focused on potential targets for ethanol action in the transmembrane (TM) domains of GlyRs. Several of these studies employed the substituted cysteine accessibility method (SCAM) (Karlin and Akabas 1998) in combination with the anesthetic-like propyl methanethiosulfonate (PMTS) (Mascia et al. 2000). The authors proposed that PMTS would covalently bind to the substituted cysteine residue and change the normal effect of PMTS (reversible potentiation) to irreversible potentiation if the actions of PMTS and alcohols result from binding at this site. The results and subsequent studies fit this prediction and provide solid evidence that position 267 and, possibly other sites in the TM domain of GlyRs, are sites of ethanol action and contribute to an ethanol “binding/action” pocket (Mihic et al. 1997;Ye et al. 1998;Ye et al. 2002;Lobo et al. 2007).

Studies using pressure indicate that the extracellular domain also contains important targets for ethanol. These studies found that a naturally occurring mutation in Loop 2 of the extracellular domain of α1GlyRs (A52S) (Ryan et al. 1994;Saul et al. 1994) rendered α1GlyRs insensitive to pressure antagonism of 100mM ethanol (Davies et al. 2004). Prior work has also shown that A52S mutant α1GlyRs are less sensitive to ethanol than WT GlyRs (Mascia et al. 1996b;Davies et al. 2004;Lobo et al. 2007). Follow-up studies at normal atmospheric pressure, which utilized the SCAM technique in combination with PMTS, added two key elements to the evidence supporting the extracellular domain as an ethanol target (Crawford et al. 2007). This work found that PMTS exposure caused irreversible alcohol-like potentiation in α1A52C GlyRs and, thus, suggested a cause-effect relationship between ethanol acting on this site in the extracellular domain and alcohol-like GlyR modulation (Crawford et al. 2007). Further studies found that PMTS binding to cysteines in A52C and S267C α1GlyRs decreased the alcohol cutoff in a manner consistent with the notion that position 52 in the extracellular domain and position 267 in the TM domain form part of the same alcohol-action pocket (Crawford et al. 2007). These findings with position 52 of the α1GlyR parallel earlier findings that established the TM domain as a target for ethanol action. Collectively, these findings indicate that ethanol acts on targets in both the TM and extracellular domains, and that positions 52 and 267 are part of the same alcohol pocket (Crawford et al. 2007).

Interestingly, hyperbaric and other findings in WT and mutant α1GlyRs suggest that there may be a relationship between the physical chemical characteristics of the amino acid at position 52 and sensitivity to ethanol and to pressure antagonism of ethanol. As discussed above, substituting a polar serine for the non-polar alanine in WT α1GlyRs reduced ethanol sensitivity and eliminated sensitivity to pressure antagonism of ethanol (Davies et al. 2004). Moreover, sequence analysis of α1GlyRs and α2GlyRs indicates that α2GlyRs have a polar threonine at position 59, which is homologous to position 52 in WT α1GlyRs. Like A52S α1GlyRs, α2GlyRs have reduced ethanol sensitivity and are insensitive to pressure antagonism of ethanol compared to α1GlyRs (Davies et al. 2004). Taken together, these findings suggest that the polarity of the amino acid at position 52 in α1GlyRs, and the homologous position in α2GlyRs, plays a key role in determining the sensitivity of the receptor to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol. Prior studies found a significant correlation between the molecular volume of the amino acid at TM position 267 and ethanol sensitivity (Ye et al. 1998), which suggests that other physical-chemical parameters at position 52 might also influence sensitivity of the receptor to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol.

The present studies test the hypothesis that the physical-chemical properties of the specific residue at position 52 in WT α1GlyRs (A52) or its homologous position in WT α2GlyRs (T59), are determinants of the receptor’s sensitivity to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol. The findings support this hypothesis, increase our understanding of the molecular targets for ethanol action and antagonism, and should help in the development of novel prevention and treatment strategies for alcohol-related problems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Adult female Xenopus laevis frogs were purchased from Nasco (Fort Atkinson, WI). Penicillin, streptomycin, gentamicin, 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester, glycine, ethanol, and collagenase were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All other chemicals used were of reagent grade. Certified premixed gases were supplied by Specialty Air Technologies (Long Beach, CA).

Expression in Oocytes

Xenopus oocytes were isolated and injected with either human α1, α2 or mutant α1A52C, α1A52F, α1A52I, α1A52S, α1A52T, α1A52V, α1A52W, α1A52Y, or α2T59A cDNAs (1 ng per 32 nl) cloned into the mammalian expression vector pCIS2 or pBKCMV as previously described (Davies et al. 2003) and verified by partial sequencing (DNA Core Facility, University of Southern California, USA). Mutagenesis of the alanine at position 52 in α1GlyRs or the threonine at position 59 in α2GlyRs was performed as previously described (Ryan et al. 1994). After injection, oocytes were stored individually in incubation medium (MBS supplemented with 2mM sodium pyruvate, 0.5mM theophylline, 10,000 U/l penicillin, 10 mg/l streptomycin and 50 mg/l gentamicin) in petri dishes (VWR, San Dimas, CA). All solutions were sterilized by passage through 0.22 μM filters. Oocytes, stored at 18°C, usually expressed GlyRs the day after injection. Oocytes were used in electrophysiological recordings for 3–7 days after cDNA injection.

Atmospheric conditions

Atmospheric conditions were established as described previously (Davies et al. 1999;Davies et al. 2003). Briefly, we tested the 1 ATA air condition (control) in a hyperbaric chamber with the lid removed or by using compressed air with the chamber sealed. Pilot studies determined that there was no measurable difference between the results obtained by these two methods. To achieve the 12 ATA heliox condition, the chamber was purged with heliox and then pressurized to the experimental ATA at the rate of 1 ATA/min using premixed certified compressed gases. The heliox mixture consisted of 1.7% oxygen and 98.3% helium resulting in a 0.2 ATA partial pressure for oxygen at 12 ATA; this mixture provides normal oxygenation. We found previously that this mixture avoids complications from higher oxygen partial pressures (Alkana and Malcolm 1981). We replaced the nitrogen in our gas mixture with helium to avoid the depressant effect of nitrogen at increased atmospheric pressure (Alkana and Malcolm 1982).

Hyperbaric Two-Electrode Whole Cell Voltage Clamp Recording

Two-electrode voltage clamp recording was performed using techniques similar to those previously reported (Davies et al. 2003). Briefly, electrodes pulled (P-30, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) from borosilicate glass [1.2mm thick-walled filamented glass capillaries (WPI, Sarasota, FL)] were back-filled with 3M KCl to yield resistances of 0.5 -3 MΩ. All electrophysiological recordings were conducted within a specially designed hyperbaric chamber that contains a vibration resistant platform that supports an oocyte bath, two micro positioners (WPI, Sarasota, FL or Narishige International USA, Inc East Meadow, NY) and bath clamp (Davies et al. 2003). Oocytes were perfused in a 100 μl oocyte bath with MBS ± drugs via a custom high pressure drug delivery system (Alcott Chromatography, Norcross, GA) at 2 ml/min using 1/16 OD high pressure PEEK tubing (Upchurch Scientific, Oak Harbor, WA). Oocytes were voltage clamped at a membrane potential of −70 mV using a Warner Instruments Model OC-725C (Hamden, CT) oocyte clamp. Individual oocytes were tested at both control and experimental atmospheric conditions and checked for normal function during pressurization and depressurization. The order of testing control and atmospheric conditions was counterbalanced to minimize the effects of testing order and to determine if pressure effects were reversible.

Hyperbaric ethanol experiments

Previous work found that ethanol potentiation of GlyR function is more robust and reliable when tested in the presence of low concentrations of glycine (typically EC2-10) (Davies et al. 2003). Based on these studies, we used a concentration of glycine producing 2 ± 0.3% of the maximal effect (EC2). Pilot experiments found that WT and mutant GlyR responses using a 1 min glycine application reached maximal response, which did not differ appreciably from results using 30s applications. Therefore, we used the shorter application time to increase efficiency and to minimize desensitization at the higher glycine concentrations. When testing ethanol potentiation, the oocytes were preincubated with ethanol for 60 sec prior to co-application of ethanol and glycine (Davies et al. 2004). Washout periods (5–15 min) were allowed between drug applications to ensure complete resensitization of receptors. The hyperbaric experiments for WT α1, α1A52S, and α2T59A were measured across a full ethanol concentration range (25–200mM). For the α1A52C, α1A52F, α1A52I, α1A52T, α1A52V, α1A52W and α1A52Y mutants, we tested 100mM ethanol because this concentration produced a degree of potentiation that was functionally equivalent to the potentiation produced by ethanol in WT α1GlyRs that were antagonized by pressure (Davies et al. 2003;Davies et al. 2004). All experiments testing mutant GlyRs included WT control receptors expressed in the same batch of oocytes as the respective mutant GlyRs. A chart recorder (Barnstead/Thermolyne, Dubuque, IA) continuously plotted the clamped currents. The peak currents were measured and used in data analysis. All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–23° C).

Data Analysis

Data for each experiment were obtained from oocytes from at least two different frogs. The n refers to the number of oocytes tested. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Where no error bars are shown, they are smaller than the symbols. We used Prism (GraphPAD Software, San Diego, CA) to perform curve fitting and statistical analyses. Concentration response data were analyzed using non-linear regression analysis: [I = Imax [A] nH / ([A] nH + EC50 nH)] where I is the peak current recorded following application of a range of agonist concentrations, [A]; Imax is the estimated maximum current; EC50 is the glycine concentration required for a half-maximal response and nH is the Hill slope. Data were subjected to t-tests, one- or two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparison or Bonferroni post tests when warranted. For the correlation analyses, the change in ethanol potentiation upon exposure to 12ATA (ΔP) was determined by subtracting mean ethanol % potentiation at 12ATA from that observed at 1ATA. Polarity values were assigned to amino acid residues using the Zimmerman polarity scale (Zimmerman et al. 1968). Hydrophobicity values were assigned using the Eisenberg hydrophobicity scale (Eisenberg et al. 1984). Molecular volumes were calculated with the Spartan Molecular Modeling Program (Wave Function, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

RESULTS

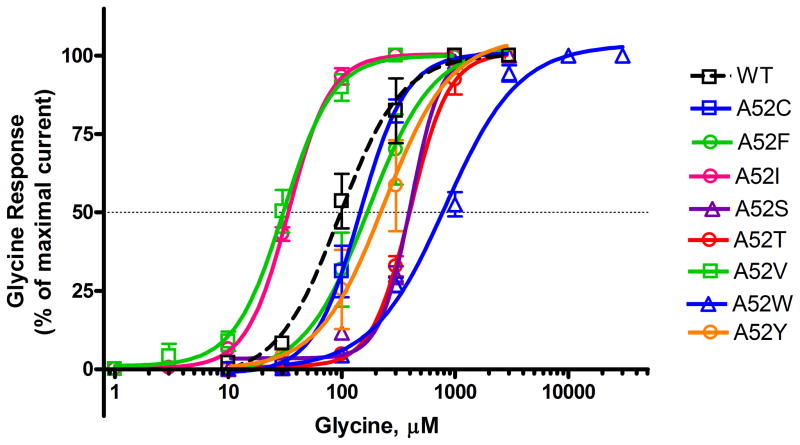

Glycine EC50s in WT and Mutant α1GlyRs

The effect of point mutations at position 52 on glycine sensitivity of α1GlyRs is shown in Figure 1A. Inward chloride currents were evoked in a concentration-dependent manner by glycine in WT and all mutant GlyRs. We found significant right shifts in glycine EC50 from WT α1GlyR for the polar α1A52S, α1A52T and α1A52W GlyRs and significant left shifts for the non-polar α1A52I and α1A52V GlyRs, but not for other substitutions. EC50 values of WT and mutant α1GlyRs did not correlate significantly with polarity, hydrophobicity, molecular volume, or weight (Data not shown). No significant differences were observed between WT and mutant GlyRs in Hill slope (nH) and/or maximal current amplitude (Imax) (Table 1).

Figure 1. Concentration-response curves for glycine (10–3,000 μM) activated chloride currents in Xenopus oocytes expressing WT and mutant α1GlyR subunits.

Glycine induced chloride currents were normalized to the maximal current activated by a saturating concentration of glycine (3 mM) when tested under 1 ATA air conditions. The curves represent non-linear regression analysis of the glycine concentration responses in the α1 mutant GlyRs compared to WT α1GlyRs. Details of EC50, Hill Slope and Maximal current amplitude (Imax) are provided in Table 1. Glycine was applied for 30 sec. Washout time was 5–15 min after application of glycine. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM from 4 different oocytes.

Table 1. Summary of non-linear regression analysis results for glycine concentration responses and differences in ethanol sensitivity WT and mutant α1 and α2 GlyRs shown in terms of increasing polarity of residue at position 52 or 59.

Glycine EC50, Hill Slope (nH) and maximal current amplitude (Imax) are presented as mean ± SEM from 4 different oocytes (as shown in Figure 1). Statistical significance from WT α1GlyRs was assessed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test. GlyRs containing polar substitutions at position 52 were significantly right shifted from α1WT and not significantly different than WT α2GlyRs in terms of EC50 with the exception of A52W. No significant differences were observed from WT α1GlyRs for Hill Slope (nH) or maximal current amplitude (Imax).

| Receptor (relative polarity) | Imax (nA) | Hill Slope | EC50 (μM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-polar | α1A52V | 17800±1842 | 2.2±0.3 | 31±4 |

| α1A52I | 18425±2072 | 2.5±0.4 | 34±1 | |

| α1 A52F | 18625±5525 | 2.3±0.3 | 199±62 | |

| α1 WT (A52) | 19875±2932 | 2.1±0.3 | 130±48 | |

| α2 T59A | 17750±4033 | 1.6±0.4 | 123±45 | |

| Intermediate polar | α1 A52C | 18250±2322 | 2.4±0.3 | 148±23 |

| Polar | α2 WT (T59) | 20687±7026 | 2.3±0.3 | 374±61 |

| α1 A52T | 18187±4360 | 2.9±0.5 | 410±32 | |

| α1 A52S | 18375±5572 | 3.4±0.4 | 387±10 | |

| α1A52Y | 16687±2809 | 2.8±0.9 | 239±58 | |

| α1A52W | 16750±2809 | 1.4±0.1 | 839±112 |

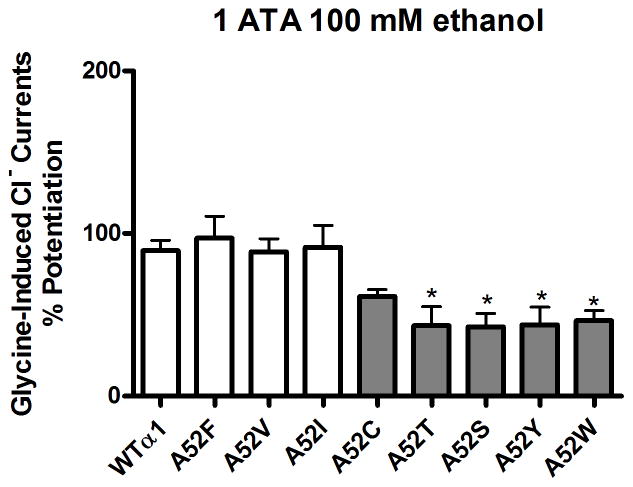

Ethanol Sensitivity in WT and Mutant α1GlyRs

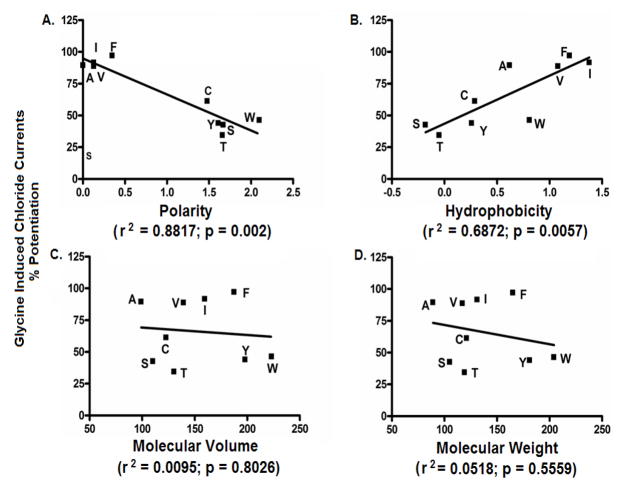

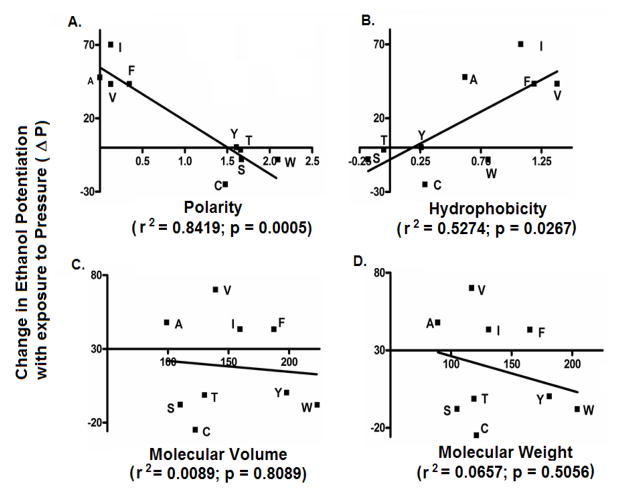

The effect of point mutations at position 52 in α1GlyRs on sensitivity to 100mM ethanol is shown in Figure 2. Ethanol responses for highly polar substitutions at position 52 - α1A52S, α1A52T, α1A52W and α1A52Y were significantly reduced compared to WT α1GlyRs. Ethanol responses for the intermediate-polar α1A52C and non-polar α1A52I, α1A52V and α1A52F mutants were not significantly reduced compared to WT α1GlyRs. There was a significant inverse correlation between polarity and receptor sensitivity to ethanol (Figure 3A). In addition, we found a significant direct correlation between hydrophobicity of the residue at position 52 and receptor sensitivity to ethanol (Figure 3B). The r2 values from the correlation analyses indicate that polarity explained approximately 88% of the variability in the sensitivity of α1GlyRs to ethanol while hydrophobicity accounted for approximately 69% of the variability. In contrast to polarity and hydrophobicity, the molecular volume and weight of the residues at position 52 did not appear to affect the sensitivity of α1GlyRs to ethanol (Figure 3C–D).

Figure 2. Polarity of the residue at position 52 in α1GlyRs determines sensitivity to ethanol.

Figure shows ethanol % potentiation of glycine induced chloride current at 100mM ethanol. White bars represent non-polar substitutions at position 52 in α1 GlyRs and grey bars represent polar substitutions. Ethanol responses for the polar mutants α1A52S, α1A52T, α1A52Y and α1A52W GlyRs were significantly reduced compared to WT α1GlyRs. There were no significant differences among the polar mutants with respect to ethanol sensitivity at 100mM. Significance is *p<0.05 vs. WT α1GlyRs.

Figure 3. The polarity and hydrophobicity of substitutions at position 52 are significantly correlated with sensitivity of α1GlyRs to ethanol.

The physical-chemical properties of the residues at position 52 (A) Polarity, (B) Hydrophobicity, (C) Molecular Volume and (D) Molecular Weight respectively, were correlated against sensitivity to 100mM ethanol.

Pressure Antagonism Sensitivity in WT and Mutant α1GlyRs

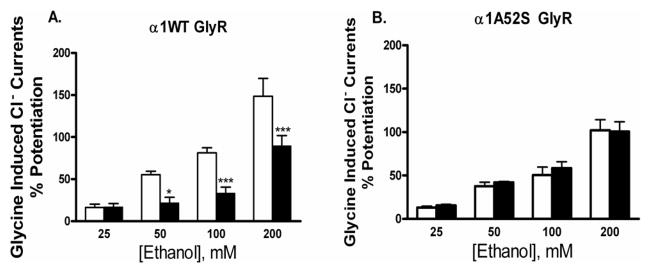

We began testing the hypothesis that the physical-chemical properties at position 52 in α1GlyRs play a role in determining sensitivity to pressure antagonism of four different concentrations of ethanol by testing A52S GlyRs, in which the non-polar alanine in WT receptors was replaced by a polar serine. Oocytes expressing α1WT or A52S GlyRs were voltage-clamped and tested with glycine +/− (25–200mM) ethanol under both control and pressure conditions. Consistent with previous findings (Davies et al. 2004), the alanine to serine mutation at position 52 eliminated sensitivity to pressure antagonism of 100mM ethanol seen in WTα1 GlyRs. This lack of the antagonist’s effect was evident across a broad range of ethanol concentrations (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(A). Pressure significantly antagonizes ethanol potentiation in α1 GlyRs: The figure depicts WT α1GlyRs tested at both 1ATA air control (white bars) and 12 ATA heliox (black bars). In agreement with previous findings, pressure antagonized ethanol potentiation from 50–200mM but not at 25mM; (B) Pressure Does not Antagonize Ethanol potentiation in mutant α1A52S GlyRs: The figure depicts results from 25–100 mM ethanol in the mutant (A52S) α1GlyRs form the same batches of oocytes shown in (A), tested at both 1 ATA air control (white bars) and 12 ATA heliox (black bars). Data is presented as mean ± SEM of 4–6 oocytes. Data was subjected to two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analyses. Statistical significance is *p < 0.05 or ***p<0.001.

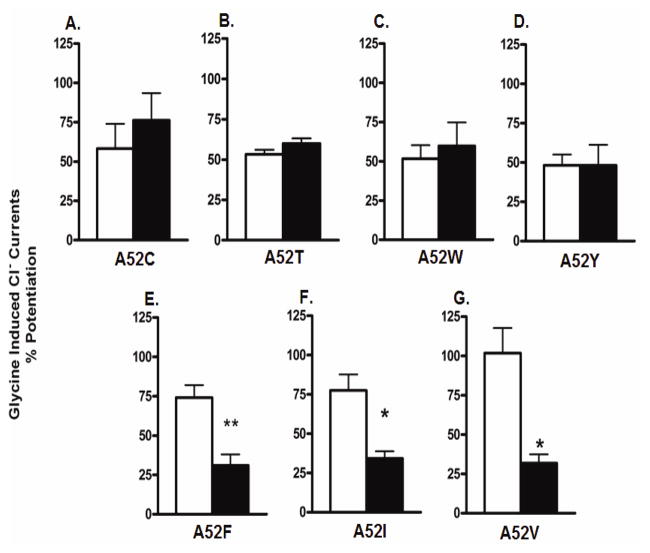

We expanded the investigation to test the effects of mutations with different physical chemical parameters at position 52 on the sensitivity to pressure antagonism of ethanol in α1GlyRs. Based on the results with ethanol sensitivity (Figures 2 and 3), we focused on polarity and hydrophobicity, but also investigated substitutions that altered molecular weight and volume.

Oocytes expressing the polar α1A52T, α1A52W and α1A52Y GlyRs, the intermediate-polar α1A52C GlyRs and the non-polar α1A52F, α1A52I and α1A52V GlyRs were voltage-clamped and tested with glycine +/− (100mM) ethanol under both control and pressure conditions. We found that exposure to 12 ATA heliox did not significantly affect ethanol potentiation in the polar α1A52C, α1A52T, α1A52W or α1A52Y GlyRs (Figure 5A–D). In contrast, pressure did significantly antagonize ethanol potentiation of 100mM in the non-polar α1A52F, α1A52I and α1A52V GlyRs (Figure 5E–G). Moreover, as with sensitivity to ethanol, there was a significant inverse correlation between polarity of the residue at position 52 and receptor sensitivity to pressure antagonism of ethanol (Figure 6A) and a significant inverse correlation between hydrophobicity of the residue at position 52 and sensitivity to pressure antagonism of ethanol (Figure 6B). The r2 indicated that polarity explained approximately 84% of the variability in the sensitivity of α1GlyRs to pressure antagonism of ethanol while hydrophobicity accounted for approximately 53% of the variability. In contrast to polarity and hydrophobicity, the molecular volume and weight of the residues at position 52 did not correlate with sensitivity to ethanol or pressure antagonism of ethanol (Figure 6C–D). Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that the polarity/hydrophobicity, but not the molecular weight or volume, of the residue at position 52 in α1GlyRs are key factors in determining the sensitivity of the receptor to pressure antagonism of ethanol.

Figure 5. Pressure antagonizes ethanol in α1GlyRs that have a non-polar residue at position 52.

The figure depicts mutant α1GlyRs tested at both 1ATA air control (white bars) and 12 ATA heliox (black bars). Exposure to 12 ATA heliox did not significantly affect ethanol potentiation at 100mM in (A) α1A52C (intermediate, intermediate-polar) (B) α1A52T (intermediate, polar), (C) α1A52W (bulky, polar) or (D) α1A52Y (bulky, polar) GlyRs. Pressure did significantly antagonize ethanol potentiation of (E) α1A52F (bulky, non-polar), (F) α1A52I (intermediate, non-polar) and (G) α1A52V (small, non-polar) GlyRs. Data were analyzed using unpaired t-tests to determine the effect of atmospheric condition on ethanol potentiation of glycine-activated chloride currents. Statistical significance is **p<0.01. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 4–6 oocytes.

Figure 6. The polarity of the residue at position 52 in α1GlyRs determines the receptors sensitivity to pressure antagonism of ethanol.

The physical-chemical properties of the residues at position 52 (A) Polarity, (B) Hydrophobicity, (C) Molecular Volume and (D) Molecular Weight respectively, were correlated against change in ethanol potentiation upon exposure to 12ATA (ΔP).

Ethanol and Pressure Antagonism Sensitivity in α2 GlyRs

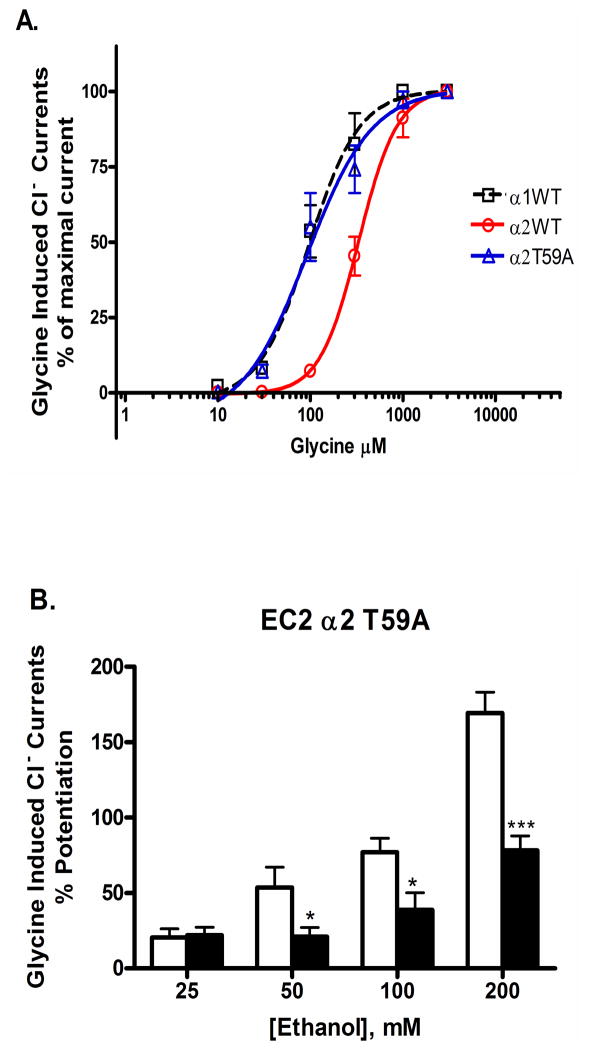

As described above, α1 and α2GlyRs differ in their sensitivity to ethanol (α1 > α2) and sensitivity to pressure antagonism of ethanol (α1—pressure antagonism sensitive; α2—pressure antagonism insensitive) (Davies et al. 2004). Sequence alignment between the Loop 2 regions of the receptor subtypes revealed that the WT α2GlyR has a polar threonine at position 59, the position homologous to position 52 in α1GlyRs (Table 2). Given that substituting the non-polar alanine for a polar threonine reduces ethanol sensitivity and eliminates sensitivity to pressure antagonism of ethanol in α1GlyRs (Figures 2 and 5A), we predicted that mutating this polar threonine in α2GlyRs to the non-polar alanine would convert the response of α2GlyRs to ethanol and pressure to be similar to those of α1GlyRs. The α2T59A mutation yielded functional receptors with glycine concentration responses that were left shifted compared to WT α2GlyRs and were similar to WT α1GlyRs (Figure 7A). As predicted, the alanine substitution at position 59 changed WT α2GlyRs from being insensitive to pressure antagonism of ethanol to being sensitive to the antagonism (Figure 7B). Overall, the findings in α1 and α2GlyRs demonstrate that switching between non-polar and polar residues at homologous positions 52 and 59 can switch the response of α1GlyRs to ethanol and pressure to be α2-like and vice-versa.

Table 2. Alignment of a portion of the amino terminal regions from human α1GlyR, α1A52S GlyR and α2GlyR subunit sequences.

Asterisks indicate residues that differ between WT α1 and α2GlyRs. Black boxed in region represents Loop 2. Residues in bold represent position 52 in α1GlyRs and homologous position 59 in α2GlyR respectively. Relative sensitivity to ethanol potentiation (EtOH) and whether pressure can antagonize the effects of ethanol (Pressure) are shown.

|

Figure 7.

(A) Concentration-response curves for glycine (10–3,000 μM) activated Cl- currents in Xenopus oocytes expressing WT and mutant α2 glycine receptor subunits: Glycine induced chloride currents were normalized to the maximal current activated by a saturating concentration of glycine (3mM) when tested under 1 ATA air conditions. The curves represent non-linear regression analysis of the glycine concentration responses in the α2 WT and mutant GlyRs compared to WT α1GlyRs. Details of EC50, Hill Slope and Maximal current amplitude (Imax) are provided in Table 1. Glycine was applied for 30 sec. Washout time was 5–15 min after application of glycine. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM from 4 different oocytes; (B) Replacing the polar threonine at position 59 in WT α1GlyRs with the non-polar alanine changes the α2GlyRs to be α1GlyR-like in response to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol: The figure depicts mutant α2T59A GlyRs tested at both 1ATA air control (white bars) and 12 ATA heliox (black bars). As predicted, pressure antagonized ethanol potentiation from 50–200mM but not at 25mM. The ethanol responses in the mutant were similar to WT α1GlyRs. Data were subjected to two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analyses. Statistical significance is *p < 0.05 or ***p<0.001. Data are presented as mean ± SEM of 4–5 oocytes.

DISCUSSION

Considerable attention has begun to focus on the development of medications to prevent or treat alcoholism. This focus is, in part, due to the marked increase in knowledge regarding the neurochemical targets for ethanol’s effects on brain function. This includes identification of neurotransmitter systems that appear to be initial targets for ethanol such as LGICs (e.g., GABAA, glycine, glutamate, 5HT3) and other targets that may play a role in mediating physical dependence and craving (Deitrich et al. 1989;Zhou and Lovinger 1996;Mihic et al. 1997;Ye et al. 1998;Cardoso et al. 1999;Harris 1999;Davies and Alkana 2001). However, this information has not resulted in comparable success in the development of pharmacological treatments for alcoholism.

Current approved therapeutics for alcoholism focus on deterring drinking by making alcohol ingestion aversive (e.g., disulfiram) or reducing the craving for alcohol (e.g., naltrexone and acamprosate) (Heilig M. and Egli M. 2006). However, the modest success rate of these drugs reflects, at least in part, their proposed mechanisms, which do not focus on blocking the actions of ethanol at initial targets. Rather, these drugs target neurochemical and neuropeptide systems in the downstream cascades leading to craving and dependence. Recently, varenicline, an approved pharmacotherapeutic for smoking cessation, demonstrated significant reduction in both acute and chronic alcohol consumption in an animal model (Steensland et al. 2007). Other drugs currently under investigation for alcoholism include topiramate (Johnson et al. 2007) and rimonabant (Colombo et al. 2007). But, these drugs also, theoretically, target downstream actions of ethanol.

An alternative approach that we have taken focuses on strategies to develop agents that are designed to block the initial actions of ethanol at its different neurotransmitter targets, thus potentially yielding novel prevention and treatment approaches (Alkana and Malcolm 1980;Davies and Alkana 1998). Recent studies along these lines have investigated the benzodiazepine receptor inverse agonist RO 15–4513 as a novel method of antagonizing ethanol action in GABAARs (Wallner et al. 2006).

Presently, we do not know enough about where and how ethanol acts to develop medications that antagonize ethanol directly. Part of the difficulty lies in the physical-chemical nature of ethanol’s mechanism of action, which limits the ability to use standard pharmacological approaches to study ethanol’s actions and effects, and to identify direct mechanistic ethanol antagonists (Deitrich et al. 1989). Findings over the last fifteen years suggesting that ethanol acts by “binding” to “pockets” (Franks and Lieb 1994;Mihic et al. 1997;Franks and Lieb 1997;Ye et al. 1998;Wick et al. 1998;Mascia et al. 2000;Crawford et al. 2007) seem to have blurred the mechanistic distinction between intoxicant-anesthetics, such as ethanol and other psychoactive drugs. However, the primary determinant of intoxicant-anesthetic potency remains hydrophobicity, not molecular structure. Furthermore, the high, millimolar ethanol concentrations required for its biological actions are inconsistent with high affinity sites of action and suggests that ethanol acts simultaneously by the same mechanism on different types of initial sites (Deitrich et al. 1989). Hence, ethanol’s physical-chemical mechanism of action is fundamentally different from the selective, high affinity binding mechanism that is known to initiate the behavioral effects of most psychoactive drugs (Dunn et al. 1999). This atypical mechanism, and resultant lack of high affinity and pharmacological specificity, precludes the classical approach of using “ethanol receptor” antagonists to identify the sites and mechanisms of ethanol action.

The present studies used increased atmospheric pressure in place of a traditional pharmacological antagonist to probe the molecular sites and mechanisms of ethanol action in GlyRs. We focused on position 52 in Loop 2 in the extracellular domain of GlyRs based on prior work which indicated that this position is part of an ethanol action pocket and is also a site of ethanol antagonism (Davies et al. 2004;Crawford et al. 2007).

We tested the hypothesis that the physical-chemical properties at position 52 in α1GlyRs or the homologous position 59 in α2GlyRs determine sensitivity to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol. As predicted, we found that pressure antagonized the effects of ethanol in α1GlyRs that contain a non-polar residue at position 52, but did not antagonize the receptors that had a polar residue at this position. Moreover, ethanol sensitivity in the receptors with polar substitutions at position 52 was significantly lower compared to the GlyRs with non-polar residues at this position.

These findings indicate that the polarity and the hydrophobicity of the residue at position 52 plays a key role in determining the responsiveness of α1GlyRs to both ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol. Correlation analyses presented in the present paper support this conclusion in α1GlyRs. In addition, the α2T59A mutation restored sensitivity to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol in the α2GlyR, thereby making it α1-like in these respects. Collectively, these findings in α1 and α2 GlyRs point to Loop 2 in the extracellular domain of GlyRs as a potential target for the development of alcohol antagonists. They also indicate that there is structural functional homology across subunits in Loop 2 of the extracellular domain with respect to the role they play in determining sensitivity to ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol. These findings in the extracellular region differ from previous studies in the TM region that showed a role for molecular volume at position 267 in controlling ethanol sensitivity in α1GlyRs (Ye et al. 1998), and suggest that different physical-chemical properties may influence ethanol action, respectively, in the extracellular and TM domains.

Although polarity and hydrophobicity are related, and are often thought to be interchangeable, examining separately their correlations with potency revealed some insights into the nature of the ethanol binding sites. The Zimmerman polarity scale used in the present study (Zimmerman et al. 1968) is based on the difference in electronegativity between atoms in the amino acids tested, and is not directly determined by oil-water partitioning/partition coefficients. However, hydrophobicity is determined by the oil-water partitioning of the respective amino acids. Hence, these differences in the physical chemical parameters likely underlie the respective differences in the strength of the correlations with sensitivity to ethanol and to pressure antagonism of ethanol.

For example, tryptophan is considered to be a non-polar amino acid due to the hydrophobic character of its indole ring, which is reflected in its relatively high positioning in the hydrophobicity scale. In contrast, the electron pair on the indole nitrogen allows it to form a hydrogen bond and causes it to behave like a polar amino acid. In addition, the indole ring in tryptophan (and the aromatic rings in A52F and A52Y) could act as an acceptor in a cation-pi interaction (Dougherty 1996) and this ability is not reflected in the hydrophobicity scale. In the present study, tryptophan appears to be a key determinant of the strength of the correlations with sensitivity to both ethanol and pressure antagonism of ethanol. Specifically, when its polarity is used, it fits nicely in the linear correlation for both sensitivity to ethanol, and pressure antagonism of ethanol. In contrast, when its hydrophobicity is used, tryptophan is an outlier in both cases. This suggests that polarity, and not hydrophobicity, is the key determinant. Taken together, these findings suggest that the physical-chemical factors at position 52 that influence sensitivity to ethanol and sensitivity to pressure antagonism of ethanol are influenced strongly by polarity and that polarity may be the underlying factor that gives hydrophobicity its correlation.

There are several possible explanations for the antagonistic effects of 12 ATA pressure observed in the present study. Fortunately, previous studies help to define the most likely mechanisms. Direct effects of high pressure on protein structure have been studied extensively. However, these studies typically use 1000 to 10,000 ATA to observe effects (Weber G and Drickamer HG 1983). Indeed, in the present studies no effect was observed at 12 ATA in the response of GlyRs in the absence of ethanol. The effect of pressure on membrane fluidity (Trudell et al. 1973;Mastrangelo et al. 1979) and phase transitions (Trudell et al. 1974) in phospholipid bilayers has also been studied, but approximately 100 ATA was required to observe significant effects.

More pertinent to interpretation of the present results are studies in which approximately 10 ATA of Xenon or nitrous oxide was sufficient to displace water molecules from solvated cavities in proteins. For example, Xenon displaced water molecules from the pore of the cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) with little change in the structure of the water-soluble five stranded coil (Malashkevich et al. 1996). However, in the case of cavities engineered into T4-lysozyme (Quillin et al. 2000), occupancy of the cavities by Xenon resulted in swelling of the cavity volume. Although the latter low pressure studies demonstrated significant effects at 8–12 ATA, there is an important distinction between the soluble gases used in them and the relatively insoluble heliox used in the present study: Raising the equilibrium pressure of Xenon from 1 to 10 ATA raises the local concentration of the gas that could enter a cavity by the same ratio. This increase in activity of Xenon is sufficient to explain its ability to displace water from a binding site.

In contrast, raising the pressure of heliox makes only a small increase in the concentration of the gas in the cavity, because helium is relatively insoluble in water and lipid. Moreover, the short period that the solutions used in the present study were exposed to hyperbaric heliox further reduces the possibility that helium was dissolved in the solutions. Thus, the antagonism by 12 ATA heliox cannot be explained by an increase in the local concentration of heliox that displaces water and/or ethanol from the cavity, but is a direct effect of hydrostatic pressure.

Ethanol could act on GlyRs by creating excess partial molar volume. That is, the volume of the total system with alcohol present would be greater than the sum of the volumes of ethanol, water, and GlyR. This hypothesis that alcohols and anesthetics create excess partial molar volume has been presented in various forms by several authors (Miller et al. 1973;Mori et al. 1984;Imai T et al. 2006) and is consistent with the swelling of cavities by Xenon described above for T4-lysozyme. Given that exposure to 12 ATA heliox did not change WT or mutant receptor function in the absence of ethanol, it is reasonable to conclude that pressure does not change the way that water hydrates the exterior of the GlyR or fills its internal cavities. This notion is supported by previous work that shows that glycine response under 12 ATA heliox remains constant with multiple applications of glycine over prolonged periods, which indicates that pressure antagonism cannot be explained by receptor desensitization or rundown (Davies et al. 2003;Davies et al. 2004). Therefore, the most likely explanation of pressure antagonism of ethanol in GlyRs is that pressure offsets the increase in partial molar volume produced by ethanol. Pressure could do this by displacing ethanol and/or an ethanol-water complex from an active site.

The above notion is consistent with our present and previous data that suggest a continuous thermodynamic opposition between the effects of ethanol and pressure (Davies et al. 2004). That is, ethanol causes potentiation of α1GlyR, pressure opposes this potentiation, but the pressure effect can be overcome by increasing the ethanol concentration (Figure 4A). Moreover, the differences in sensitivity to ethanol, based on the physical chemical properties of mutations at homologous positions 52 and 59 in α1 and α2 GlyRs, add key information to this model. The mutation of A52 to more polar residues reduced the potentiation by ethanol. This change can be explained by the differences in the forces attracting water and ethanol in the WT and mutant receptors. That is, water is attracted to alanine (non-polar) in WT A52 α1GlyRs by a combination of London dispersion and van der Waals forces; whereas, water is attracted to serine (polar) in mutant A52S α1GlyRs by these forces plus hydrogen bonding. Therefore, it would be harder for ethanol to displace water in order to access positions 52 when the respective position contains a polar versus non-polar residue. These differences in the accessibility of ethanol to a site of action could explain the differences in ethanol sensitivity of WT and mutant GlyRs.

In conclusion, the findings presented in this report represent the initial steps towards defining a site and mechanism of ethanol action and antagonism in GlyRs. Additional studies will increase our knowledge regarding the physical-chemical characteristics necessary for pressure antagonism, and in turn will aid in the development of molecules that mimic the ethanol antagonizing properties of pressure. Given the homology between GlyRs and other LGICs (GABAAR, 5HT3R and nAchRs), the current findings should also provide insight into the molecular mechanisms and targets of ethanol action and antagonism in other LGICs in the Cys loop superfamily of receptors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miriam Fine, Rachel Kelly and Drs. Liana Asatryan and Kaixun Li for technical assistance and Dr. Peter Schofield for providing the wild type α1 glycine receptor cDNA.

This work was supported in part by research grants NIH/NIAAA 1F31 AA017569 (D.I.P), AA03972 (R.L.A.), AA013890 and AA013922 (D.L.D.), and AA013378 (J.R.T.), NIGMS G64371 (J.R.T.), and the USC School of Pharmacy.

Abbreviations

- 5HT3R

5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor

- COMP

cartilage oligomeric matrix protein

- GlyR

glycine receptor

- GABAAR

γ-aminobutyric acid type-A receptor

- LGIC

ligand-gated ion channel

- nAChR

nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- PMTS

propyl methanethiosulfonate

- SCAM

substituted cysteine accessibility method

- TM

transmembrane

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

This work was conducted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree in Molecular Pharmacology & Toxicology, University of Southern California (D.I.P.)

Portions of these findings were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism in Chicago, IL (Alcohol: Clin. Exp. Res., Vol. 31, Issue s2, p. 16A, 2007) and at the Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting in San Diego, CA ( Program No. 874.9/F2. 2007 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. San Diego, CA: Society for Neuroscience, 2007. Online)

References

- 1.Aguayo LG, Pancetti FC. Ethanol modulation of the γ-aminobutyric acidA and glycine-activated Cl− current in cultured mouse neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkana RL, Davies DL, Morland J, Parker ES, Bejanian M. Low level hyperbaric exposure antagonizes locomotor effects of ethanol and n-propanol but not morphine in C57BL mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:693–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkana RL, Jones BL, Palomares ML, Crabbe JC, Bejanian M. Mechanism of low level hyperbaric ethanol antagonism: Specificity versus other drugs. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 1992;1:63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkana RL, Malcolm RD. The effects of low level hyperbaric treatment on acute ethanol intoxication. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1980;126:499–507. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3632-7_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alkana RL, Malcolm RD. Low-level hyperbaric ethanol antagonism in mice. Dose and pressure response. Pharmacology. 1981;22:199–208. doi: 10.1159/000137491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alkana RL, Malcolm RD. Hyperbaric ethanol antagonism in mice: studies on oxygen, nitrogen, strain and sex. Psychopharmacology. 1982;77:11–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00436093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bejanian M, Jones BL, Alkana RL. Low-level hyperbaric antagonism of ethanol-induced locomotor depression in C57BL/6J mice: dose response. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:935–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betz H. Glycine receptors: heterogeneous and widespread in the mammalian brain. TINS. 1991;14:458–461. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90045-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowser-Riley F, Daniels S, Smith EB. Investigations into the origin of the high pressure neurological syndrome: the interaction between pressure, strychnine and 1,2- propandiols in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 1988;94:1069–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardoso RA, Brozowski SJ, Chavez-Noriega LE, Harpold M, Valenzuela CF, Harris RA. Effects of ethanol on recombinant human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:774–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombo G, Orrù A, Lai P, Cabras C, Maccioni P, Rubio M, Gessa GL, Carai MA. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, rimonabant, as a promising pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence: preclinical evidence. Mol Neurobiol. 2007;36:102–112. doi: 10.1007/s12035-007-0017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford DK, Trudell JR, Bertaccini E, Li KX, Davies DL, Alkana RL. Evidence that ethanol acts on a target in Loop 2 of the extracellular domain of alpha1 glycine receptors. J Neurochem. 2007;102:2097–2109. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies DL, Alkana RL. Direct antagonism of ethanol’s effects on GABAA receptors by increased atmospheric pressure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1689–1697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies DL, Alkana RL. Ethanol enhances GABAA receptor function in short sleep and long sleep mouse brain membranes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:478–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies DL, Bejanian M, Parker ES, Morland J, Bolger MB, Brinton RD, Alkana RL. Low-level hyperbaric antagonism of diazepam’s locomotor depressant and anticonvulsant properties in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:667–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies DL, Bolger MB, Brinton RD, Finn DA, Alkana RL. In vivo and in vitro hyperbaric studies in mice suggest novel sites of action for ethanol. Psychopharmacology. 1999;141:339–350. doi: 10.1007/s002130050843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies DL, Crawford DK, Trudell JR, Mihic SJ, Alkana RL. Multiple sites of ethanol action in α1 and α2 glycine receptors suggested by sensitivity to pressure antagonism. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1175–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies DL, Morland J, Jones BL, Alkana RL. Low-level hyperbaric antagonism of ethanol’s anticonvulsant property in C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:1190–1195. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies DL, Trudell JR, Mihic SJ, Crawford DK, Alkana RL. Ethanol potentiation of glycine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes antagonized by increased atmospheric pressure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1–13. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065722.31109.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deitrich R, Dunwiddie T, Harris RA, Erwin VG. Mechanism of action of ethanol: initial central nervous system actions. Pharmacol Rev. 1989;41:489–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dougherty DA. Cation-pi interactions in chemistry and biology: a new view of benzene, Phe, Tyr, and Trp. Science. 1996;271:163–168. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn SMJ, Davies M, Muntoni AL, Lambert JJ. Mutagenesis of the rat α1 subunit of the γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor reveals the importance of residue 101 in determining the allosteric effects of benzodiazepine site ligands. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:768–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eckenhoff RG, Johansson JS. Molecular interactions between inhaled anesthetics and proteins. Pharmacol Rev. 1997;49:343–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eggers ED, O’Brien JA, Berger AJ. Developmental changes in the modulation of synaptic glycine receptors by ethanol. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:2409–2416. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.5.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenberg D, Weiss RM, Terwilliger TC. The hydrophobic moment detects periodicity in protein hydrophobicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:140–144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engblom AC, Åkerman KE. Effect of ethanol on γ-aminobutyric acid and glycine receptor-coupled Cl− fluxes in rat brain synaptoneurosomes. J Neurochem. 1991;57:384–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb03764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of general anaesthesia. Nature. 1994;367:607–614. doi: 10.1038/367607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franks NP, Lieb WR. Inhibitory synapses: Anaesthetics set their sites on ion channels. Nature. 1997;389:334–335. doi: 10.1038/38614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou P, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris RA. Ethanol actions on multiple ion channels: which are important? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1563–1570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heilig M, Egli M. Pharmacological treatment of alcohol dependence: target symptoms and target mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:855–876. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imai T, Isogai H, Seto T, Kovalenko A, Hirata F. Theoretical study of volume changes accompanying xenon-lysozyme binding: implications for the molecular mechanism of pressure reversal of anesthesia. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2006;110:12149–12154. doi: 10.1021/jp056346j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, Wiegand F, Mao L, Beyers K, McKay A, Ait-Daoud N, Anton RF, Ciraulo DA, Kranzler HR, Mann K, O’Malley SS, Swift R. Topiramate for Treating Alcohol Dependence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1641–1651. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlin A. Emerging structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Nat Reviews, Neurosci. 2002;3:102–1. doi: 10.1038/nrn731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karlin A, Akabas MH. Substituted-Cysteine Accessibility Method. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:123–145. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kendig JJ. Pressure dependence of excitable cell function. TINS. 1984;7:483–486. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Little HJ. How has molecular pharmacology contributed to our understanding of the mechanism(s) of general anesthesia? Pharmacol Ther. 1996;69:37–58. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)02030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lobo IA, Harris RA, Trudell JR. Cross-linking of sites involved with alcohol action between transmembrane segments 1 and 3 of the glycine receptor following activation. J Neurochem. 2007;104:1649–1662. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malashkevich VN, Kammerer RA, Efimov VP, Schulthess T, Engel J. The crystal structure of a five-stranded coiled coil in COMP: A prototype ion channel? Science. 1996;274:761–765. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malosio ML, Marquèze-Pouey B, Kuhse J, Betz H. Widespread expression of glycine receptor subunit mRNAs in the adult and developing rat brain. EMBO J. 1991;10:2401–2409. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07779.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mascia MP, Machu TL, Harris RA. Enhancement of homomeric glycine receptor function by long-chain alcohols and anaesthetics. Br J Pharmacol. 1996a;119:1331–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mascia MP, Mihic SJ, Valenzuela CF, Schofield PR, Harris RA. A single amino acid determines differences in ethanol actions on strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1996b;50:402–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mascia MP, Trudell JR, Harris RA. Specific binding sites for alcohols and anesthetics on ligand-gated ion channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9305–9310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160128797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mastrangelo CJ, Kendig JJ, Trudell JR, Cohen EN. Nerve membrane lipid fluidity: Opposing effects of high pressure and ethanol. Undersea Biomed Res. 1979;6:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCool BA, Frye GD, Pulido MD, Botting SK. Effects of chronic ethanol consumption on rat GABAA and strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors expressed by lateral/basolateral amygdala neurons. Brain Res. 2003;963:165–177. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03966-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mihic SJ, Ye Q, Wick MJ, Koltchine VV, Krasowski MD, Finn SE, Mascia MP, Valenzuela CF, Hanson KK, Greenblatt EP, Harris RA, Harrison NL. Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors. Nature. 1997;389:385–389. doi: 10.1038/38738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller KW, Paton WDM, Smith RA, Smith EB. The pressure reversal of anaesthesia and the critical volume hypothesis. Mol Pharmacol. 1973;9:131–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molander A, Lidö HH, Löf E, Ericson M, Söderpalm B. The glycine reuptake inhibitor Org 25935 decreases ethanol intake and preference in male wistar rats. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:11–18. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molander A, Söderpalm B. Accumbal strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors: an access point for ethanol to the brain reward system. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:27–37. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000150012.09608.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mori T, Matubayasi N, Ueda I. Membrane expansion and inhalation anesthetics. Mean excess volume hypothesis. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;25:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ortells MO, Lunt GG. Evolutionary history of the ligand-gated ion- channel superfamily of receptors. TINS. 1995;18:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93887-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quillin ML, Breyer WA, Griswold IJ, Matthews BW. Size versus polarizability in protein-ligand interactions: binding of noble gases within engineered cavities in phage T4 lysozyme. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:955–977. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajendra S, Lynch JW, Schofield PR. The glycine receptor. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;73:121–146. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryan SG, Buckwalter MS, Lynch JW, Handford CA, Segura L, Shiang R, Wasmuth JJ, Camper SA, Schofield PR, O’Connel P. A missense mutation in the gene encoding the α1 subunit of the inhibitory glycine receptor in the spasmodic mouse. Nature Genet. 1994;7:131–135. doi: 10.1038/ng0694-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saul B, Schmieden V, Kling C, Mülgardt C, Gass P, Kuhse J, Becker CM. Point mutation of glycine receptor α1 subunit in the spasmodic mouse affects agoinst responses. FEBS Lett. 1994;350:71–76. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schofield PR, Darlison MG, Fujita N, Burt DR, Stephenson FA, Rodriguez H, Rhee LM, Ramachandran J, Reale V, Glencorse TA, Seeburg PH, Barnard EA. Sequence and functional expression of the GABAA receptor shows a ligand-gated receptor super-family. Nature. 1987;328:221–227. doi: 10.1038/328221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Richards JK, Bartlett SE. Varenicline, an {alpha}4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12518–12523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705368104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Syapin PJ, Chen J, Finn DA, Alkana RL. Antagonism of ethanol-induced depression of mouse locomotor activity by hyperbaric exposure. Life Sci. 1988;43:2221–2229. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tao L, Ye JH. Protein Kinase C Modulation of Ethanol Inhibition of Glycine-Activated Currnt in Dissociated Neurons of Rat Ventral Tegmental Area. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:967–975. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.3.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tapia JC, Aguilar LF, Sotomayor CP, Aguayo LG. Ethanol affects the function of a neurotransmitter receptor protein without altering the membrane lipid phase. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;354:239–244. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Trudell JR, Payan DG, Chin JH, Cohen EN. Pressure-induced elevation of phase transition temperature in dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine bilayers: an electron spin resonance measurement of the enthalpy of phase transition. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;373:436–443. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trudell JR, Hubbell WL, Cohen EN. Pressure reversal of inhalation anesthetic-induced disorder in spin-labeled phospholipid vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;291:328–334. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(73)80001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valenzuela CF, Cardoso RA, Wick MJ, Weiner JL, Dunwiddie TV, Harris RA. Effects of ethanol on recombinant glycine receptors expressed in mammalian cell lines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1132–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wallner M, Hanchar HJ, Olsen RW. Low-dose alcohol actions on alpha4beta3delta GABAA receptors are reversed by the behavioral alcohol antagonist Ro15–4513. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8540–8545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600194103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wann KT, MacDonald AG. Actions and interactions of high pressure and general anesthetics. Prog Neurobiol. 1988;30:271–307. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(88)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weber G, Drickamer HG. The effect of high pressure upon proteins and other biomolecules. Q Rev Biophys. 1983;16:89–112. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500004935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wick MJ, Mihic SJ, Ueno S, Mascia MP, Trudell JR, Brozowski SJ, Ye Q, Harrison NL, Harris RA. Mutations of γ-aminobutyric acid and glycine receptors change alcohol cutoff: Evidence for an alcohol receptor? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6504–6509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ye JH, Tao L, Krnjevic K, McArdle JJ. Decay of Ethanol-Induced Suppression of Glycine-Activated Current of Ventral Tegmental Area Neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:788–798. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ye Q, Koltchine VV, Mihic SJ, Mascia MP, Wick MJ, Finn SE, Harrison NL, Harris RA. Enhancement of glycine receptor function by ethanol is inversely correlated with molecular volume at position α267. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3314–3319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yevenes GE, Moraga-Cid G, Guzmán L, Haeger S, Oliveira L, Olate J, Schmalzing G, Aguayo LG. Molecular determinants for G protein betagamma modulation of ionotropic glycine receptors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39300–39307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608272200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou Q, Lovinger DM. Pharmacologic characteristics of potentiation of 5-HT3 receptors by alcohols and diethyl ether in NCB-20 neuroblastoma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:732–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zimmerman JM, Eliezer N, Simha R. The characterization of amino acid sequences in proteins by statistical methods. J Theor Biol. 1968;21:170–201. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(68)90069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ziskind-Conhaim L, Gao BX, Hinckley C. Ethanol dual modulatory actions on spontaneous postsynaptic currents in spinal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:806–813. doi: 10.1152/jn.00614.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]