Background: The small subunit of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase contains three Cys-to-Asp/Glu thioether bonds.

Results: The radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) enzyme QhpD catalyzes the single-turnover reaction of thioether bond formation in the protein substrate.

Conclusion: The thioether bond formation by QhpD proceeds sequentially in an N- to C-terminal direction of the polypeptide.

Significance: Our findings uncover another challenging reaction of radical SAM superfamily of enzymes.

Keywords: Iron-Sulfur Protein, Post-translational Modification, Protein Cross-linking, Radical, S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM), Enzyme Maturation

Abstract

The bacterial enzyme designated QhpD belongs to the radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) superfamily of enzymes and participates in the post-translational processing of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase. QhpD is essential for the formation of intra-protein thioether bonds within the small subunit (maturated QhpC) of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase. We overproduced QhpD from Paracoccus denitrificans as a stable complex with its substrate QhpC, carrying the 28-residue leader peptide that is essential for the complex formation. Absorption and electron paramagnetic resonance spectra together with the analyses of iron and sulfur contents suggested the presence of multiple (likely three) [4Fe-4S] clusters in the purified and reconstituted QhpD. In the presence of a reducing agent (sodium dithionite), QhpD catalyzed the multiple-turnover reaction of reductive cleavage of SAM into methionine and 5′-deoxyadenosine and also the single-turnover reaction of intra-protein sulfur-to-methylene carbon thioether bond formation in QhpC bound to QhpD, producing a multiknotted structure of the polypeptide chain. Homology modeling and mutagenic analysis revealed several conserved residues indispensable for both in vivo and in vitro activities of QhpD. Our findings uncover another challenging reaction catalyzed by a radical SAM enzyme acting on a ribosomally translated protein substrate.

Introduction

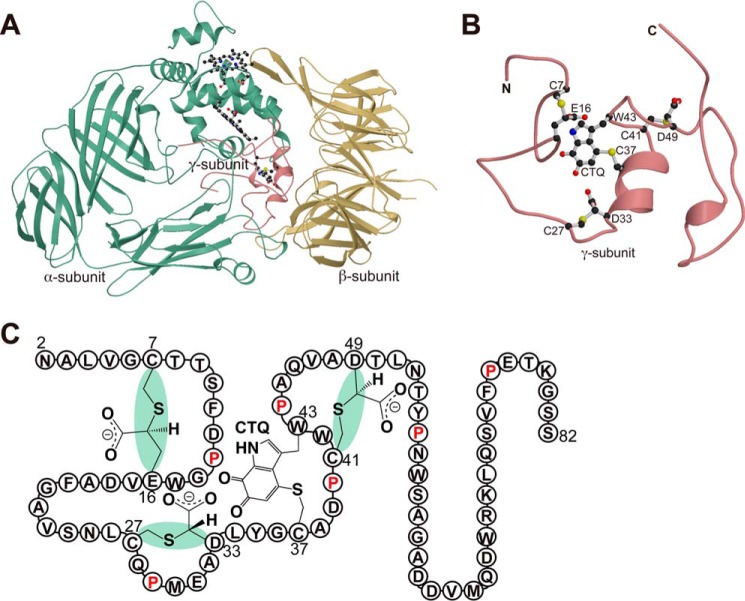

Quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase (QHNDH)2 is a bacterial enzyme that catalyzes oxidative deamination of various aliphatic primary amines for use as energy, carbon, and nitrogen sources (1–3). Although the enzyme was originally reported to occur only in a limited number of Gram-negative bacteria (2, 3), our recent survey with the updated genome sequence database revealed a wide distribution of the enzyme not only in more than 200 Gram-negative species but also in some Gram-positive bacteria with the associated genes constituting an operon designated “qhp” (4). QHNDH consists of three nonidentical subunits, with each subunit exhibiting distinct structural features (Fig. 1A) (5, 6). The large subunit of 60 kDa, termed α and encoded by the qhpA gene, has four domains with two hemes that mediate electron transfer from the substrate to an external electron acceptor, such as cytochrome c550 and azurin (2, 3), contained in the N-terminal di-heme cytochrome c peroxidase-like domain. The mid-sized subunit of 36 kDa, termed β and encoded by the qhpB gene, has a β-propeller structure that is highly conserved in quinoprotein dehydrogenases. The smallest subunit of ∼9 kDa, termed γ and encoded by qhpC, has an unprecedented protein structure with four internal thioether cross-links (Fig. 1B). One of the cross-links (Cys-37–Trp-43) is formed between the sulfur atom of a Cys residue and the indole group of a Trp residue that is specifically modified to contain ortho-quinone groups, building a peptidyl quinone cofactor, cysteine tryptophylquinone (CTQ). Three other thioether cross-links (Cys-7–Glu-16, Cys-27–Asp-33, and Cys-41–Asp-49) are formed between the sulfur atom of a Cys residue and the methylene carbon atom of an Asp or Glu residue, affording the structural stabilization of the subunit polypeptide chain that is otherwise a featureless coil with only two short α-helices. Therefore, the γ subunit must undergo multiple post-translational modifications, in which many gene products encoded in the qhp operon, including QhpD, QhpE, QhpF, and QhpG, are involved (4, 7, 8), and such events occur before or after associating with the α and β subunits to form the active QHNDH complex.

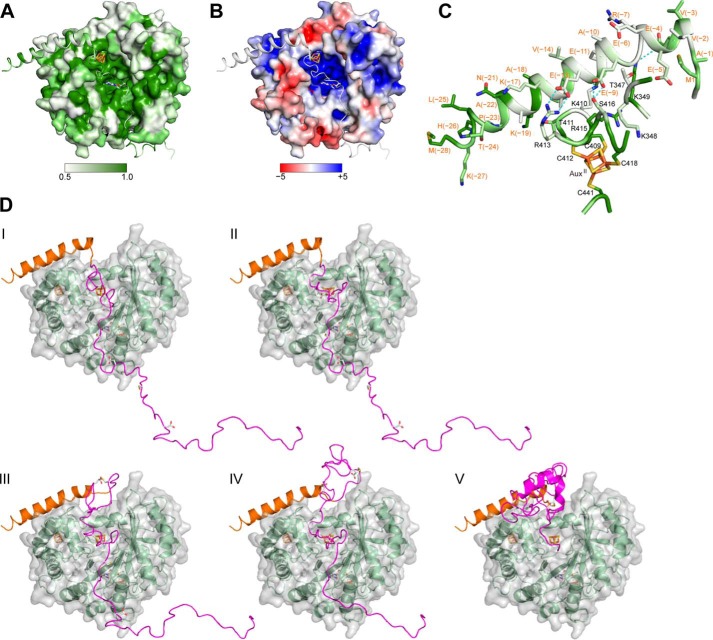

FIGURE 1.

Crystal structure of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase. A, ribbon model of QHNDH from P. denitrificans (PDB code 1JJU) with α, β, and γ subunits colored green, yellow, and magenta, respectively. Hemes and CTQ are drawn as ball-and-stick models. B, enlarged view of the γ subunit in an orientation different from A. CTQ and thioether cross-links are shown as ball-and-stick models. This figure was prepared using MOLSCRIPT (49) and Raster3D (50). C, schematic structure of γ subunit is shown with the stereochemistry of the thioether bonds and the amino acid residues in a single-letter code.

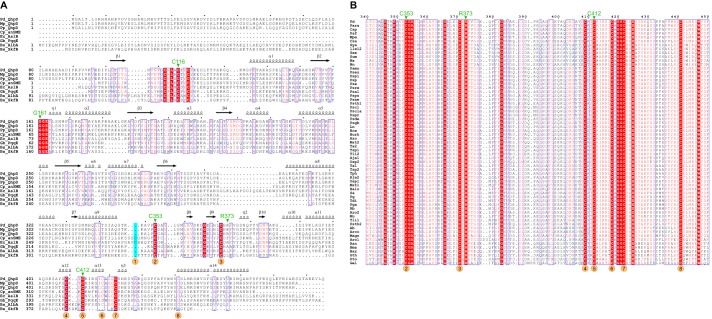

The QhpD protein belongs to the radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) superfamily currently comprising ∼113,600 members (9), harboring the consensus CX3CX2C [4Fe-4S] cluster-binding motif in the N-terminal region (10–12). QhpD is essential for the biogenesis of QHNDH, most likely by participating in the Cys-to-Asp/Glu thioether bond formation in the γ subunit (maturated QhpC) (7). Consistent with its indispensable role in the QHNDH biogenesis, the qhpD gene is strictly conserved in all bacteria possessing the qhp operon with the common gene array, qhpADCB (and their reverse, BCDA, in the complementary strands) (4). According to recent bioinformatics analysis, QhpD is classified into the subgroup “SPASM/twitch domain-containing,” named for its biochemically characterized founding members as follows: subtilosin A-synthesizing enzyme, AlbA; pyrroloquinoline quinone biosynthetic enzyme, PqqE; anaerobic sulfatase-maturating enzyme, anSME; and mycofactocin synthesizing enzyme, MtfC (13, 14). About 11,800 members classified into this subgroup (9) are characterized by sharing the 7-cysteine motif (CX9–15GX4C-gap-CX2CX5CX3C-gap-C) in the C-terminal half (15), which are likely involved in binding of auxiliary [4Fe-4S] clusters (16, 17). Moreover, multiple sequence alignment of QhpD and its homologs with other SPASM proteins (Fig. 2) reveals strict conservation of several residues throughout the subgroup and also some residues only among QhpD homologs that constitute the QHNDH maturation protein family (9), in addition to the N-terminal signature CX3CX2C motif that ligates the SAM-binding [4Fe-4S] cluster (10–12). These SPASM proteins are primarily involved in cofactor and peptide maturation processes, acting on ribosomally translated proteins (peptides) encoded in the vicinity of their genes (14).

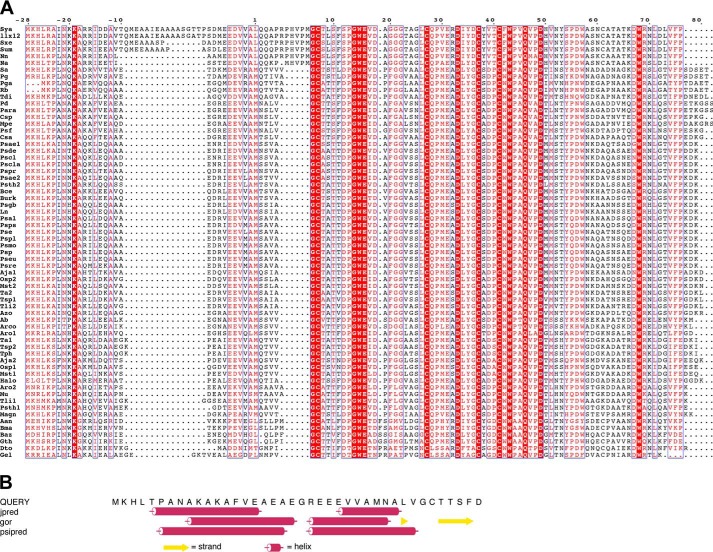

FIGURE 2.

Structure-based sequence alignment of QhpD homologs. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using the program ClustalW (51) for QhpD homologs and other radical SAM proteins belonging to the SPASM subgroup in A as follows: QhpD from P. denitrificans (Pd_QhpD, NCBI RefSeq, YP_915497); Meganema perideroedes (Mp_QhpD, WP_018634150); Ps. putida (Pp_QhpD, WP_010954326); anSME from C. perfringens (Cp_anSME (anSMEcpe), WP_011590280; PDB code 4K36); AslB from E. coli (Ec_AslB, YP_026259); PqqE from Granulibacter bethesdensis (Gb_PqqE, WP_011632626); AlbA from Bacillus subtilis (Bs_AlbA, WP_003242599); and SkfB from B. subtilis (Bs_SkfB, WP_003234902); and multiple sequence alignment was performed using the program ClustalW for SPASM domains of QhpD homologs in B as follows: Aneurinibacillus aneurinilyticus (Aan, GenBank gi:545381874); Arcobacter butzleri (Ab, gi:157736727); Amphritea japonica (Aja1, gi:518449972; Aja2, gi:518449964); Arcobacter sp. L (Arco, gi:384171423); Aromatoleum aromaticum (Aro1, gi:56478378; Aro2, gi:56476667); Azoarcus sp. BH72 (Azo, gi:119897531); Bacillus azotoformans (Baz, gi:489426247); Burkholderia cepacia (Bce, gi:402569817); Brevibacillus massiliensis (Bma, gi:517950086); Burkholderia sp. TJI49 (Burk, gi:325526527); Caenispirillum salinarum (Csa, gi:497227880); Citreicella sp. SE45 (Csp, gi:260425941); Desulfobacula toluolica (Dto, gi:408418101); Geopsychrobacter electrodiphilus (Gel, gi:522163448); Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius (Gth, gi:489342624); Halomonas sp. KM-1 (Halo, gi:498311926); Pseudogulbenkiania ferrooxidans (Ln, gi:224823976); Magnetospirillum sp. SO-1 (Magn, gi:495896650); M. perideroedes (Mpe, gi:517463417); Marinobacterium stanieri (Mst1, gi:498009607; Mst2, gi:498009580); Methyloversatilis universalis (Mu, gi:334132770); Novosphingobium aromaticivorans (Na, gi:87201041); Novosphingobium nitrogenifigens (Nn, gi:326387246); Neptuniibacter caesariensis (Osp1, gi:89094965; Osp2, gi:89093841); Paracoccus sp. TRP (Para, gi:498081303); P. denitrificans (Pd, gi:119384441); Polymorphum gilvum (Pg, gi:328544106); Phaeobacter gallaeciensis (Pga, gi:518127691); Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Psae, gi:544781831); Ps. alcaligenes (Psal, gi:544800897); Ps. chlororaphis (Pscla, gi:496335660); Ps. chlororaphis (Pscl, gi:496340839); Ps. denitrificans (Psde, gi:472325482); Ps. entomophila (Pse, gi:104782043); Ps. sp. FGI182 (Pseu, gi:568240125); Ps. fluorescens (Psf, gi:77459199); Pseudogulbenkiania sp. NH8B (Psgb, gi:347540000); Ps. putida (Psmo, gi:431802845); Ps. putida (Psp, gi:24985113); Ps. plecoglossicida (Pspl, gi:511761567); Ps. protegens (Pspr, gi:70731475); Ps. pseudoalcaligenes (Psps, gi:489543545); Ps. resinovorans (Psre, gi:512618903); Ps. thermotolerans (Psth1, gi:516562571; Psth2, gi:516563886); Rhodobacterales bacterium (Rb, gi:254467660); Stappia aggregata (Sa, gi:118588651); Sphingobium ummariense (Sum, gi:544909902); Sphingobium xenophagum (Sxe, gi:515748629); Sphingobium yanoikuyae (Sya, gi:490321472); Thauera aminoaromatica (Ta1, gi:479298785; Ta2, gi:479297321); Thiothrix disciformis (Tdi, gi:521061977); Thauera linaloolentis (Tli1, gi:490477633; Tli2, gi:490475214); Thauera phenylacetica (Tph, gi:490494489); Thauera sp. MZ1T (Tsp1, gi:217969195; Tsp2, gi:237653643); and α-proteobacterium LLX12A (llx12, gi:516070889). A, secondary structural elements found in the crystal structure of anSMEcpe (17) are shown above the alignment; the region including Gln-345–Leu-360 of Pd_QhpD was re-aligned manually so that Cys-353 of QhpD corresponds to Cys-261 of anSMEcpe to coincide with the QhpD structure model, described later (Fig. 15). Identical and highly conserved residues are shown by white letters on red background and red letters boxed in blue, respectively. Mutated residues of Pd_QhpD are indicated with green triangles above the alignment. Numbers in orange circles shown below the alignment represent Cys residues ligating the auxiliary clusters (Aux) in anSMEcpe (Aux I: 1, 2, 3, and 7; Aux II: 4, 5, 6, and 8) (17). The figure was produced using ESPRIPT (52).

In view of the reactions catalyzed, QhpD resembles AlbA and some other related enzymes (SkfB, ThnB, and TrnC/D) that catalyze the regiospecific formation of the sulfur-to-α-carbon thioether bonds in the biosynthesis of sactipeptides (18–20). However, QhpD differs from these proteins in that it acts on an enzyme subunit to form a multiknotted structure of the polypeptide chain with sulfur-to-methylene carbon thioether cross-links (7). In this study, we describe efficient expression of recombinant QhpD from Paracoccus denitrificans in complex with its substrate QhpC and biochemical characterization as a radical SAM enzyme, and we demonstrate that QhpD does catalyze the formation of intra-protein sulfur-to-methylene carbon thioether bonds in QhpC. Based on the modeled structure for the QhpC·QhpD complex, we propose a possible mechanism of the sequential formation of multiple thioether bonds, which uncovers another challenging reaction catalyzed by a radical SAM enzyme belonging to the SPASM subgroup.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of the QhpC·QhpD Complex

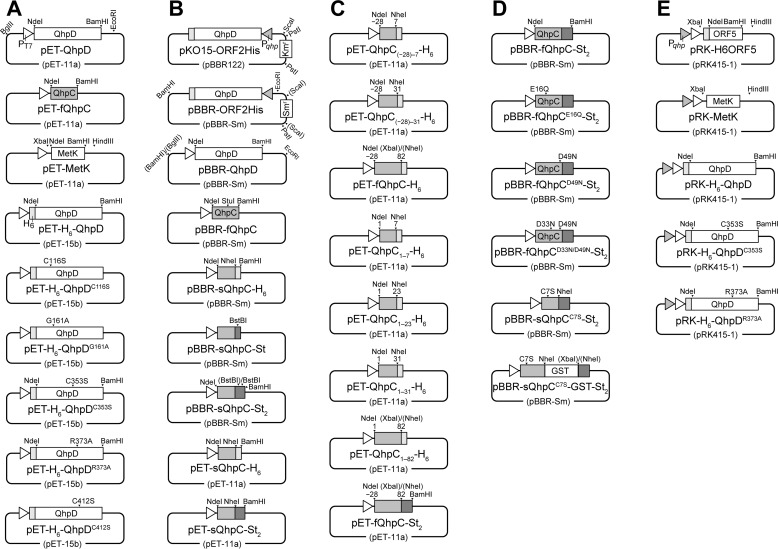

Expression plasmids for QhpC and QhpD from P. denitrificans Pd1222 and their derivatives were constructed using either an Escherichia coli expression vector pET-15b or a broad host range vector pBBR1, mostly according to standard molecular genetic protocols (Fig. 3). In addition, a hexa-His (H6) tag or a Twin-Strep (St2) tag was appended on the N terminus of QhpD or the C terminus of QhpC to aid purification of the QhpC·QhpD complex and analysis of their interaction. PCR primers used in construction of these plasmids as well as those for site-specific mutants of QhpC and QhpD are summarized in Table 1. Site-specific mutants were obtained by the PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis method. Codon replacements and the absence of PCR-derived errors, if any, were confirmed by sequencing the entire coding regions. E. coli C41 (DE3) cells carrying expression plasmids for QhpD and/or QhpC were grown at 37 °C by reciprocal shaking at 180 rpm in LB medium (1% (w/v) bactotryptone, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract, and 0.5% (w/v) NaCl) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (50 μg/ml ampicillin, 30 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 μg/ml tetracycline). When the cell density reached an OD600 of ∼0.5, 0.17 mg/ml ammonium ferric citrate and isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.1 mm were added, and the cells were further grown at 30 °C for 6 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min and stored at −20 °C until use.

FIGURE 3.

Schematic structures of the plasmids used in this study. In all plasmids depicted, only the restriction sites used for plasmid construction are indicated. A, qhpD, qhpC, and metK genes were amplified by PCR using primers containing NdeI and BamHI (or BglII for metK) sites (Table 1) with Pd1222 or E. coli genomic DNA as a template. The NdeI/BamHI (or NdeI/BglII for metK) fragments excised from the PCR products were inserted into pET-11a to yield pET-QhpD, pET-fQhpC, and pET-metK. The NdeI/BamHI fragment excised from pET-QhpD was inserted into pET-15b to yield pET-H6-QhpD. Plasmids encoding pET-H6-QhpDC116S, pET-H6-QhpDG161A, pET-H6-QhpDC353S, pET-H6-QhpDR373A, and pET-H6-QhpDC412S were obtained by the PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. B, to change antibiotic resistance of pBBR122-derived plasmids, the SmaI/HindIII fragment containing the Smr gene was excised from pGRPd1 (53), blunt-ended using Klenow fragment, and ligated into the ScaI site of pKO15-ORF2His (7). The resulting plasmid was digested at the PstI sites to remove the Kmr gene, and then self-ligated to yield pBBR-ORF2His. The BglII/EcoRI fragment containing qhpD with the T7 promoter was excised from pET-QhpD and inserted into pBBR-ORF2His (replacing qhpD and the qhp promoter) to yield pBBR-QhpD. The NdeI/BamHI fragments were excised from pET-fQhpC and inserted into pBBR-QhpD (replacing qhpD) to yield pBBR-fQhpC. Oligonucleotide encoding H6 tag and its complement were annealed and inserted into the StuI/BamHI sites in pBBR-fQhpC. The NdeI/NheI fragment was excised from the resulting plasmid and ligated to the NdeI/NheI fragment excised from the PCR product encoding sQhpC gene to yield pET-sQhpC-H6. Oligonucleotides encoding a single Strep tag (St-tag) and its complement were annealed and inserted into the NheI/BamHI sites in pBBR-sQhpC-H6 to yield pBBR-sQhpC-St. Oligonucleotides encoding a linker and the second St-tag and its complement were annealed and inserted into the BstBI site in pBBR-sQhpC-St to yield pBBR-sQhpC-St2. The NdeI/BamHI fragments were excised from pBBR-sQhpC-H6 and pBBR-sQhpC-St2 and inserted into pET-11a to yield pET-sQhpC-H6 and pET-sQhpC-St2, respectively. The restriction sites shown in parentheses were eliminated by ligation. C, genes encoding QhpC variants were amplified by PCR using primers containing NdeI and NheI (or XbaI for fQhpC and QhpC1–82) sites with pET-fQhpC as a template. The NdeI/NheI or NdeI/XbaI fragments were excised from the PCR products and inserted into pET-sQhpC-H6 to yield pET-QhpC(−28)−7-H6, pET-QhpC(−28)−31-H6, pET-fQhpC-H6, pET-QhpC1–7-H6, pET-QhpC1–23-H6, pET-QhpC1–31-H6, and pET-QhpC1–82-H6. The NdeI/XbaI fragment containing the fQhpC gene was also inserted into pET-sQhpC-St2 to yield pET-fQhpC-St2. D, NdeI/BamHI fragments were excised from pET-fQhpC-St2 and inserted into pBBR-QhpD (replacing qhpD) to yield pBBR-fQhpC-St2. Plasmids encoding pBBR-fQhpCE16Q-St2, pBBR-fQhpCD49N-St2, pBBR-fQhpCD33N/D49N-St2, and pBBR-sQhpCC7S-St2 were obtained by the PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. The gene encoding GST was amplified by PCR using primers containing NheI and XbaI sites with pGEX-6P-3 (GE Healthcare) as a template. The NheI/XbaI fragment was excised from the PCR products and inserted into pBBR-sQhpCC7S-St2 to yield pBBR-sQhpCC7S-GST-St2. E, XbaI/HindIII fragment was excised from pET-MetK and inserted into pRK-H6ORF5 (8) (replacing H6ORF5) to yield pRK-MetK. The NdeI/BamHI fragments excised from pET-H6-QhpD, pET-H6-QhpDC353S. and pET-H6-QhpDR373A were inserted into pRK-H6ORF5 (replacing ORF5) to yield pRK-H6-QhpD, pRK-H6-QhpDC353S, and pRK-H6-QhpDR373A, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Primer for plasmid constructiona | Nucleotide sequenceb | Introduced restriction site or mutation |

|---|---|---|

| H6-tag (+) | 5′-CCTGCTAGCCATCACCATCACCATCACTAG-3′ | NheI/BamHI |

| H6-tag (−) | 5′-GATCCTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGCTAGCAGG-3′ | NheI/BamHI |

| St-tag (+) | 5′-CTAGCGCTTGGAGCCACCCGCAGTTCGAAAAATAG-3′ | NheI/BstBI/BamHI |

| St-tag (−) | 5′-GATCCTATTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCAAGCG-3′ | NheI/BstBI/BamHI |

| Linker-St (+) | 5′-CGAGAAAGGTGGAGGTTCCGGAGGTGGATCGGGTGGCGGTAGTTGGAGCCACCCGCAGTT-3′ | BstBI/BstBI |

| Linker-St (−) | 5′-CGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCAACTACCGCCACCCGATCCACCTCCGGAACCTCCACCTTTCT-3′ | BstBI/BstBI |

| QhpD (+) | 5′-ATATCATATGGGAGCCCTGACCCTGATCCGC-3′ | NdeI |

| QhpD (−) | 5′-ATATGGATCCTCATTGGAGAACCTCCCTTGCTGT-3′ | BamHI |

| QhpD-C116S (+) | 5′-GGCTGCAACCTGGCCAGCACCTATTGCTAC-3′ | QhpD (C116S) |

| QhpD-C116S (−) | 5′-GTAGCAATAGGTGCTGGCCAGGTTGCAGCC-3′ | QhpD (C116S) |

| QhpD-G161A (+) | 5′-CGTGGTGTTCTTCGCCGGCGAGCCGCTG-3′ | QhpD (G161A) |

| QhpD-G161A (−) | 5′-CAGCGGCTCGCCGGCGAAGAACACCACG-3′ | QhpD (G161A) |

| QhpD-C353S (+) | 5′-GCCGTGCCCTCCGGCGCCGGG-3′ | QhpD (C353S) |

| QhpD-C353S (−) | 5′-CCCGGCGCCGGAGGGCACGGC-3′ | QhpD (C353S) |

| QhpD-R373A (+) | 5′-GCATCTGTGCCACGCCTTCGTCGGCTCGA-3′ | QhpD (R373A) |

| QhpD-R373A (−) | 5′-TCGAGCCGACGAAGGCGTGGCACAGATGC-3′ | QhpD (R373A) |

| QhpD-C412S (+) | 5′-GGCTGCAAGACCAGCCGGATACGCTC-3′ | QhpD (C412S) |

| QhpD-C412S (−) | 5′-GAGCGTATCCGGCTGGTCTTGCAGCC-3′ | QhpD (C412S) |

| QhpC (−28) (+) | 5′-ATATCATATGAAACATCTGACGCCCGCCAAT-3′ | NdeI |

| QhpC(1) (+) | 5′-ATATCATATGAATGCGCTGGTCGGCTGCACC-3′ | NdeI |

| QhpC(7) (−) | 5′-ATATGCTAGCGCAGCCGACCAGCGCATTCAT-3′ | NheI |

| QhpC(23) (−) | 5′-ATATGCTAGCGACGGCGCCGAAGGCGTC-3′ | NheI |

| QhpC(31) (−) | 5′-ATATGCTAGCCTCCATCGGCTGGCACAG-3′ | NheI |

| QhpC(82)-X (−) | 5′-ATATTCTAGAGCCTTTCGTTTCGGGGAAGAC-3′ | XbaI |

| QhpC(82)-B (−) | 5′-ATATGGATCCTCACGACGAGCCTTTCGTTTCGGG-3′ | BamHI |

| QhpC-C7S (+) | 5′-GCGCTGGTCGGCAGCACCACCTCGTTCG-3′ | QhpC (C7S) |

| QhpC-C7S (−) | 5′-CGAACGAGGTGGTGCTGCCGACCAGCGC-3′ | QhpC (C7S) |

| QhpC-E16Q (+) | 5′-GATCCCGGCTGGCAGGTGGACGCCTTC-3′ | QhpC (E16Q) |

| QhpC-E16Q (−) | 5′-GAAGGCGTCCACCTGCCAGCCGGGATC-3′ | QhpC (E16Q) |

| QhpC-D33N (+) | 5′-CCGATGGAGGCCAACCTTTACGGCTGC-3′ | QhpC (D33N) |

| QhpC-D33N (−) | 5′-GCAGCCGTAAAGGTTGGCCTCCATCGG-3′ | QhpC (D33N) |

| QhpC-D49N (+) | 5′-GCGCAGGTGGCCAACACGCTGAACACC-3′ | QhpC (D49N) |

| QhpC-D49N (−) | 5′-GGTGTTCAGCGTGTTGGCCACCTGCGC-3′ | QhpC (D49N) |

| MetK (+) | 5′-ATATCATATGGCAAAACACCTTTTTACGTCCGAGTCC-3′ | NdeI |

| MetK (−) | 5′-ATATAGATCTTTACTTCAGACCGGCAGCATCGCG-3′ | BglII |

| GST (+) | 5′-CCTTTGCTAGCTCCCCTATACTAGGTTATTGGAAAATTAAGG-3′ | NheI |

| GST (−) | 5′-GCTCTAGATTTTGGAGGATGGTCGCCACCACCAAACG-3′ | XbaI |

a Plus and minus signs in parentheses denote sense and antisense strands, respectively.

b Restriction sites are underlined. Mismatching nucleotides at the mutated sites are shown in bold.

For purification of the QhpC·QhpD complex, such as the complex between a short version of QhpC (QhpC(−28)−23; hereafter designated sQhpC) and QhpD, frozen cells were suspended in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.8, containing 300 mm NaCl, 1 mm sodium dithionite (DT), and cOmplete Protease Inhibitor (EDTA-free; Roche Applied Science) (1 tablet/50 ml of cell suspension), and disrupted by ultrasonic oscillation. The cell extract was obtained by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 1 h. All subsequent procedures were carried out in a vacuum-type glovebox (AS ONE Corp.) filled with 99.999% (v/v) argon gas; oxygen concentration was routinely maintained below 0.01% (v/v) throughout the purification by monitoring with an oxygen sensor. The stock solution of 100 mm DT in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, was also prepared freshly in the glovebox. The cell extract was applied to a nickel-chelate column (5 ml, cOmplete His-Tag Purification Resin; Roche Applied Science) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, containing 500 mm NaCl, 1 mm DT, 10 mm imidazole, and 10% (w/v) glycerol (buffer A), which was de-aerated by purging with 99.999% (v/v) N2-gas for >10 min. After washing the column with 25 ml of buffer A, the QhpC·QhpD complex was eluted with buffer A containing 500 mm imidazole. The fractions colored dark brown were collected and applied to a Strep-trap column (5 ml, Strep-Tactin Superflow high capacity 50% (v/v) suspension; IBA) pre-equilibrated with 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 150 mm NaCl and 10% (w/v) glycerol (buffer B) added with 1 mm DT. The column was washed with two bed volumes of buffer B (without DT), and the dark brown-colored complex was eluted with buffer B containing 1 mm d-desthiobiotin.

To prevent thioether bond formation in sQhpC occurring in E. coli cells during expression of the sQhpC·QhpD complex (see below), Cys-7 (the sulfur donor for the Cys-7–Glu-16 thioether bond) in sQhpC was replaced by Ser (sQhpCC7S) (Fig. 3), which did not affect expression and purification of the complex. In addition, for size discrimination from the wild-type QhpC, sQhpCC7S was expressed occasionally as a C-terminally fusion protein with GST (sQhpCC7S-GST).

For purification of the full-length QhpC (QhpC(−28)−82; designated fQhpC) without thioether bonds that are partially formed in E. coli cells when expressed as the complex with QhpD, fQhpC was first co-expressed with an inactive mutant of QhpD (QhpDC116S) and then the fQhpC·QhpDC116S complex was purified by nickel-chelate affinity chromatography as above. Subsequently, the eluted solution was incubated at 70 °C for 20 min to denature the QhpDC116S protein; fQhpC is heat-stable. After standing on ice for 20 min, the precipitated QhpDC116S was removed by centrifugation. The fQhpC remaining in the supernatant was further purified using a Strep-trap column as described above under atmospheric conditions. Site-specific mutants of fQhpC (fQhpCE16Q, fQhpCD33N/D49N, and fQhpCD49N) that do not contain pre-formed thioether bonds were also obtained by the same method. The fQhpC·QhpD complex, containing no thioether bonds in fQhpC, was prepared by anaerobically incubating the sQhpCC7S-GST·QhpD complex (60 μm), which was expressed and purified as described above, with 20 μm fQhpC containing no thioether bonds prepared as above for more than 6 h (to exchange sQhpCC7S-GST with fQhpC). The mutant fQhpC·QhpD complex was also obtained by the same method. In these experiments, the concentration of fQhpC added was kept lower than that of the complex so that most the fQhpC was bound to QhpD.

Reconstitution

QhpD in the as-purified complex was reconstituted essentially according to the published procedure (18). Briefly, the complex (protein concentration, 0.1–0.2 mm) eluted from the Strep-trap column was incubated with 100 eq of DTT (final concentration, 10–20 mm) for 1 h on ice in the glovebox. Then 10 eq of ammonium ferric citrate (final concentration, 1–2 mm) was slowly added under careful mixing, and the mixture was incubated for 5 min on ice. Finally, 10 eq of lithium sulfide (final concentration, 1–2 mm) was added, and the mixture was incubated overnight at 4 °C in a sealed bag with gentle rotary shaking. The resulting solution was filtrated through a 0.22-μm membrane and then desalted with a PD-10 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer B containing 1 mm DTT. The reconstituted QhpC·QhpD complex thus obtained was stored at 4 °C in a sealed bag containing an oxygen absorber for a few days without appreciable loss of SAM cleaving and thioether bond forming activities.

Determination of Protein Concentration and Iron and Sulfur Contents

Protein concentrations of the as-purified QhpC·QhpD complex were determined by the Bradford assay (Nacalai Tesque) using BSA as the standard. For determination of the Bradford correction factor (21), the sQhpC·QhpD complex (4.06 ± 0.21 mg/ml) was first precipitated with 10% (w/v) TCA at −20 °C for 30 min and washed twice with cold acetone to remove the bound [Fe-S] clusters. The precipitates dried in air were then dissolved in a small volume of 8 m urea (3.93 ± 0.02 mg/ml; recovery, 97%). As the urea solution exhibited a spectrum of simple protein without absorption above 350 nm (data not shown), the protein concentration was calculated to be 3.23 mg/ml from the absorbance at 280 nm using the molar extinction coefficient (52,370 m−1 cm−1, assuming all Cys residues are reduced) obtained by the web-based tool, ProtParam, in ExPASy (22). The Bradford correction factor (3.23/3.93 = 0.822) thus obtained was used for all the subsequent enzyme characterizations. The iron and sulfur contents were determined according to published procedures (23, 24).

Spectral Measurements

Solutions of the as-purified and reconstituted QhpC·QhpD complexes were prepared anaerobically in a 1-ml quartz cuvette with a gas-tight screw cap within the glovebox. UV-visible absorption spectra were recorded at 25 °C with an Agilent 8453 photodiode array spectrophotometer.

For measurement of EPR spectra, the reconstituted QhpC·QhpD complex (80 μm in buffer B) was reduced with 2 mm DT for 5 min and transferred to EPR tubes, which were sealed with screw caps, in the glovebox. The samples were immediately flash-frozen and kept in liquid nitrogen until EPR analysis. X-band (9.23 GHz) microwave frequency EPR spectra were recorded at 15 K on a Varian E-109 EPR spectrometer with 100-kHz field modulation. The microwave frequency was calibrated with a microwave frequency counter (Takeda Riken Co., Ltd., model TR5212). An Oxford flow cryostat (ESR-900) was used to achieve temperatures down to 15 K.

Assay for the SAM Cleavage Reaction

The reductive SAM cleavage activity of QhpD was measured for the sQhpC·QhpD and sQhpCC7S·QhpD complexes (63 μm) under strictly anaerobic conditions maintained in the glovebox. The reconstituted QhpC·QhpD complex in buffer B containing 1 mm DTT was first reduced with a 10-fold molar excess of DT for 10 min and then reacted with 1 mm SAM (Sigma) at an ambient temperature. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 10 mm K3[Fe(CN)6] at 10–300 min after the addition of SAM, and the precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation. For quantification of the 5′-deoxyadenosine (5′-dA) produced, a 10-μl aliquot of the supernatant was injected into a Cosmosil 5C18-PAQ reversed-phase column (Nacalai Tesque) attached to a Hitachi L-7000 HPLC system with an L-7420 UV detector. Elution was performed with 0.1% (w/v) KH2PO4 for 5 min followed by a linear gradient to 0.1% (w/v) KH2PO4 containing 40% (v/v) methanol for 15 min and then with the latter solution for 5 min at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, with the absorbance monitored at 260 nm. Under these conditions, SAM and 5′-dA are eluted at 6.8 and 24.5 min, respectively. The concentration of 5′-dA was determined by comparison with the integrated peak areas of 5′-dA standards at known concentrations. The eluate collected at the 5′-dA peak was also analyzed by TOF-MS (Accu TOF, JMS-T100LC, JEOL) equipped with a direct-analysis-in-real-time ion source (MS-54141 direct-analysis-in-real-time, JEOL).

For determination of the methionine produced, the supernatant of the reaction mixture (20 μl) was diluted 10-fold with 100 mm sodium borate, pH 9.3, containing 1 mm EDTA and incubated with 50 mm 4-(N,N-dimethylaminosulfonyl)-7-fluoro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazole (DBD-F) (Dojindo) at 50 °C for 30 min to convert the methionine into a fluorescent derivative (DBD-methionine). A 20-μl aliquot of the reaction mixture was injected into a Cosmosil 5C18-PAQ reversed-phase column attached to the L-7000 HPLC system with a Hitachi F-1050 fluorescence detector. Elution was done with 0.1% (v/v) TFA for 5 min, and then a linear gradient to 0.08% (v/v) TFA containing 80% (v/v) acetonitrile for 15 min at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, monitored by excitation at 450 nm and emission at 590 nm. Under these conditions, the DBD-methionine was eluted at ∼18 min. The concentration of methionine was determined by comparison with the integrated peak areas of methionine standards at known concentrations that had been treated with DBD-F as described above.

Assay for in Vitro Formation of Thioether Bonds

Thioether bond formation in the QhpC·QhpD complex was assayed by mass spectrometric monitoring of the disappearance of free cysteine residues in QhpC via modification with 2-iodoacetamide (IAA) (18). The reconstituted QhpC·QhpD complex (∼80 μm) in buffer B was incubated with 1 mm DT and 1 mm SAM as described above, and 50-μl aliquots were taken at appropriate times (0.5–6 h), mixed with 10% (w/v) TCA, and washed twice with cold acetone. The precipitated materials obtained by centrifugation were thoroughly dried. The residue was dissolved in 50 μl of 6 m urea in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, containing 1 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. To 10 μl of the solution was added 1 μl of 500 mm IAA in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, and the mixture was left to stand at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was acidified with 2% (v/v) formic acid, desalted with a C18 ZipTip pipette tip (Millipore), and eluted with 10 μl of 50% (v/v) acetonitrile in 0.1% (v/v) TFA. The eluate (1 μl) was subjected to mass analysis using a Bruker Ultraflex III MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer and 1 mg/ml sinapic acid (Bruker) dissolved in 90% (v/v) acetonitrile, containing 0.1% (v/v) TFA, as a matrix, which was co-crystallized with the protein by the drying-droplet method. Before every MS analysis, mass calibration was done using Protein Calibration Standard I (Bruker).

Modification of free cysteine residues with N-(9-acridinyl)maleimide (NAM) (Tokyo Chemical Industry) was carried out as follows. The dried residue obtained by precipitation of the reaction mixture (50 μl) with 10% (w/v) TCA, as described above, was dissolved in 50 μl of 1% (w/v) SDS in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, containing 1 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine and incubated at 95 °C for 5 min. To 10 μl of the solution was added 1 μl of 5 mm NAM in acetone, and the mixture was left to stand at room temperature for 1 h. After the addition of 3 μl of 50% (w/v) glycerol, the sample was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. A UV transilluminator (ChemiDoc XRS system, Bio-Rad) was used to detect fluorescent bands by excitation at 355 nm and emission at 465 nm.

Structure Modeling

The structure model of QhpD was built by applying the P. denitrificans QhpD amino acid sequence (gi: 119384441) to the website SWISS-MODEL (25), and the resultant initial model was modified manually by Coot (26). The model of the QhpC leader peptide without structural data was also built by Coot (26) initially as an ideal α-helix on the basis of secondary structure predictions by Jpred (27), GOR (28), and PSIPRED (29), which was then slightly bent around Gly(−8) to fit to the shape of a groove of the QhpD model. The modeled leader peptide was then connected at the N terminus of the core peptide of QhpC, the structure of which was extracted from the QHNDH crystal structure (PDB code 1JJU). Finally, according to the progress of the processive action of QhpD (as described below), the structure model of the QhpC core peptide with or without the thioether bonds (three Cys-to-Asp/Glu cross-links and one in the CTQ cofactor) was also built by Coot (26), using the coordinates of the γ subunit in the QHNDH crystal structure as an initial structure.

RESULTS

Expression and Purification of the QhpC·QhpD Complex

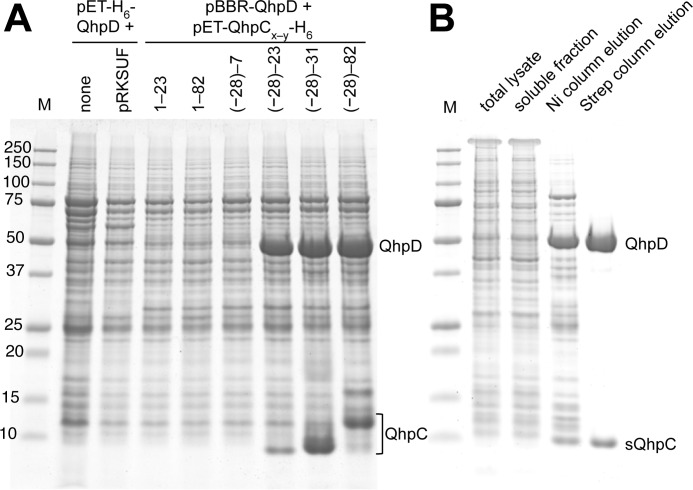

To achieve overproduction of recombinant QhpD from P. denitrificans Pd1222, we constructed various plasmids carrying the genes encoding QhpD and its substrate QhpC (Fig. 3). For QhpC, we also prepared a series of full-length and truncated forms with or without the N-terminal 28-residue leader peptide that is essential for the formation of thioether bonds in QhpC (7) but must be removed subsequently by a subtilisin-like protease QhpE (8). Initial attempts to express QhpD alone or by co-expression with a plasmid carrying E. coli iscRSUA-hscBA-fdx-iscX genes (30) or sufABCDSE genes (31), which are expected to assist the assembly of iron-sulfur clusters in radical SAM proteins (21), were all unsuccessful for efficient production of QhpD in the soluble fraction of the E. coli C41 (DE3) cell lysate. However, when QhpD was co-expressed with substrate QhpC, its expression was dramatically improved. Analysis of the cell-free extracts using a His-trap spin column revealed that expressed QhpD was tightly associated with QhpC containing the leader peptide plus the mature protein region with a sufficient length (at least residues involved in the first thioether bond between Cys-7 and Glu-16) (Fig. 4A). Co-expression of shorter QhpC with or without the leader peptide (QhpC(−28)−7, QhpC1–23) was essentially ineffective for QhpD expression, suggesting that overproduction of soluble QhpD was a result of the formation of a stable complex with QhpC containing both the leader peptide and the mature protein region of more than 23 residues. Densitometric comparison of the stained protein bands of the purified QhpC·QhpD complex (Fig. 4B) strongly suggested that the protein composition was a 1:1 complex of QhpC and QhpD. It is also noteworthy that co-expression of the full-length QhpC without the leader peptide (QhpC1–82) did not enhance the QhpD production. Thus, the leader peptide of QhpC is essential for the interaction with QhpD, leading to the efficient expression of the QhpC·QhpD complex.

FIGURE 4.

Interaction of QhpD with various forms of QhpC and affinity purification of the QhpC·QhpD complex. A, E. coli cells transformed with either pET-H6-QhpD alone, pET-H6-QhpD plus pRKSUF, or pBBR-QhpD plus one of the pET-QhpC-H6 plasmids (encoding various lengths of QhpC as indicated in the figure) were grown in 50 ml of LB medium containing appropriate antibiotics, 0.17 mg/ml of ammonium ferric citrate, and 0.1 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and disrupted by sonication in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.8, containing 300 mm NaCl. Cell extracts (2.4 ml) were applied to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid spin columns (Qiagen) in four load-and-spin cycles, and eluted proteins were precipitated with 10% (w/v) TCA and dissolved in 50 μl of loading buffer for SDS-PAGE. A 10-μl aliquot of the resultant solution was loaded in each lane. B, E. coli cells harboring pET-H6-QhpD and pBBR-sQhpC-St2 were disrupted by sonication (total lysate). The cell extract obtained by centrifugation (soluble fraction) was purified first by a nickel chelate column (Ni column elution) and second by a Strep-Tactin column (Strep column elution). A total of 7 μg of protein was loaded in each lane. The protein bands were stained with colloidal Coomassie G-250 (54).

For purification of the QhpC·QhpD complex, we routinely employed co-expression of QhpD and sQhpC, carrying an N-terminal H6 tag and a C-terminal St2 tag, respectively, encoded in separate plasmids. Transformed E. coli cells were grown in the medium supplemented with excess ferric ions for loading iron into QhpD. By using the first His trap and the following Strep trap affinity columns in an anaerobic chamber, both proteins were efficiently co-purified from the cell-free extracts to near homogeneity (purity, >90% on SDS-PAGE) as the sQhpC·QhpD complex (Fig. 4B). The as-purified complex was rather unstable, forming protein precipitates even in an overnight storage under anaerobic conditions. Therefore, it was reconstituted immediately after the purification, unless otherwise stated. The reconstituted complex thus obtained was stable for a few days when stored at 4 °C in a buffer containing 10% (w/v) glycerol under rigorously anaerobic conditions; addition of glycerol was essential to prevent protein precipitation. All the subsequent experiments were done within 1–3 days after the reconstitution.

Spectral Properties of the Purified QhpC·QhpD Complex

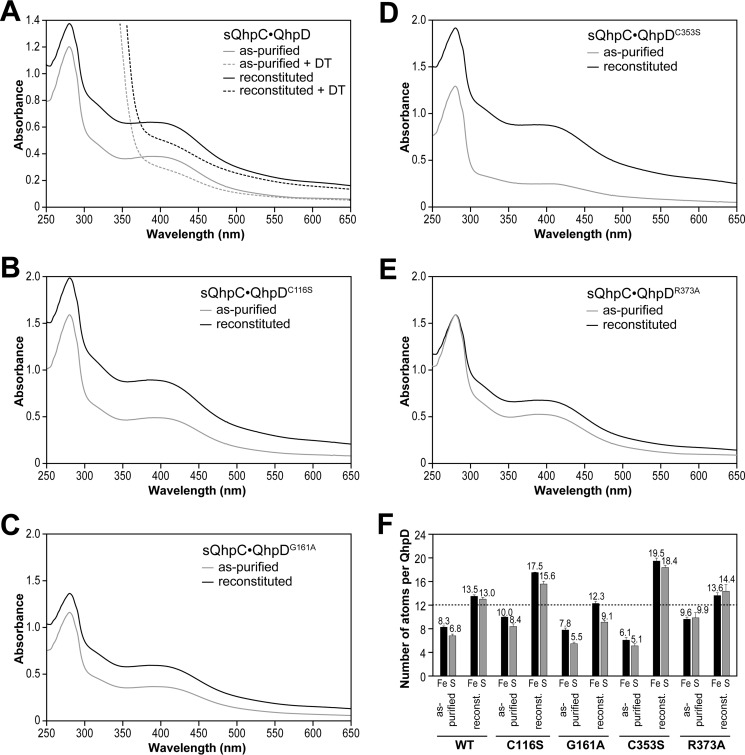

After purification, the sQhpC·QhpD complex was colored dark brown with absorption bands at ∼320 and 410 nm, thereby supporting the presence of [4Fe-4S] clusters (32, 33) in QhpD (Fig. 5). Chemical reconstitution resulted in a further increase of the absorption bands not only at 320 and 410 nm but also at 280 nm. Using a molar extinction coefficient at 410 nm reported for the [4Fe-4S] cluster (15,000 m−1 cm−1) (34, 35) and protein concentrations determined by the Bradford method and corrected with the Bradford correction factor (21), the contents of the [4Fe-4S] cluster were calculated to be about 1.6 and 2.7 mol/mol of as-purified and reconstituted sQhpC·QhpD complexes, respectively. Colorimetric iron/sulfur analysis also indicated the presence of multiple (likely three) iron-sulfur clusters (Fig. 5). These results are consistent with the presence of three iron-sulfur cluster-binding motifs conserved in the QhpD homologs (Fig. 2). The absorption band at ∼410 nm disappeared after incubation with DT (Fig. 5), suggesting reduction of the [4Fe-4S]2+ cluster.

FIGURE 5.

UV-visible absorption spectra and iron/sulfur contents of wild-type and mutant QhpD complexes with sQhpC. UV-visible absorption spectra of the as-purified (gray) and reconstituted (black) complexes of sQhpC·QhpD (A), sQhpC·QhpDC116S (B), sQhpC·QhpDG161A (C), sQhpC·QhpDC353S (D), and sQhpC·QhpDR373A (E) are shown after normalization to a protein concentration of 1 mg/ml. F, numbers of iron and sulfur atoms per each sQhpC·QhpD complex are represented by black and gray bars, respectively. Dashed line indicates the number of iron and sulfur atoms expected for the content in three [4Fe-4S] clusters.

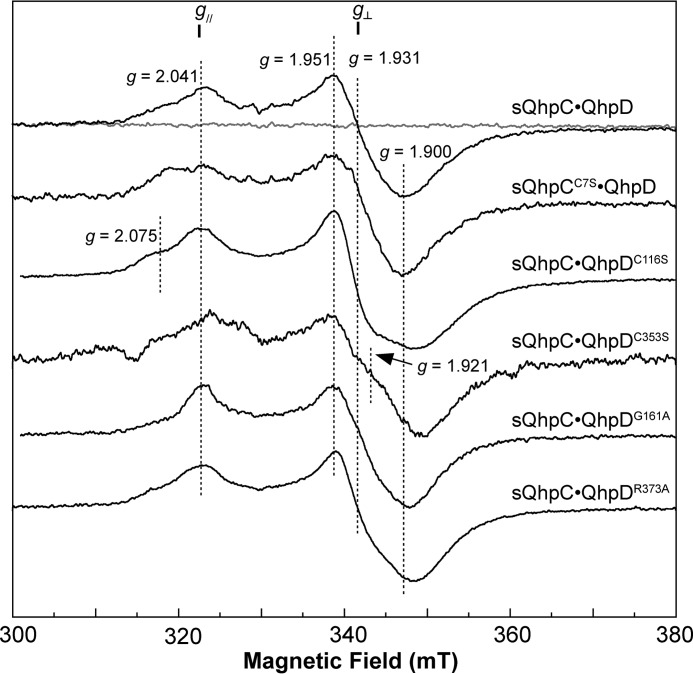

The reconstituted sQhpC·QhpD complex was EPR-silent (Fig. 6), indicating that the [4Fe-4S] clusters in QhpD are in the diamagnetic oxidized form ([4Fe-4S]2+) (36). The EPR spectrum characteristic for the reduced form of the cluster ([4Fe-4S]+) (37) was observed at 15 K after the addition of excess DT (Fig. 6), but not at 77 K (data not shown). The signals derived from the reduced QhpD were almost identical in the complex with either sQhpC (wild type) or sQhpCC7S (a mutant that does not undergo ether bond formation by QhpD, as described later), except for slight broadening of the g‖ signal at g = 2.041 (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

EPR spectra of wild-type and mutant QhpD complexes with sQhpC or sQhpCC7S. The X-band EPR spectra of the reconstituted sQhpC·QhpD, sQhpCC7S·QhpD, sQhpC·QhpDC116S, sQhpC·QhpDC353S, sQhpC·QhpDG161A, and sQhpC·QhpDR373A complexes (80 μm) are shown with important g values including those for g‖ and g⊥ signals. X-band (9.23 GHz) microwave frequency spectra before (gray) and after (black) the addition of 2 mm DT were recorded at 15 K with modulation frequency, 100 kHz; modulation amplitude, 1 millitesla (mT); and microwave power, 10 milliwatts.

SAM Cleavage Activity

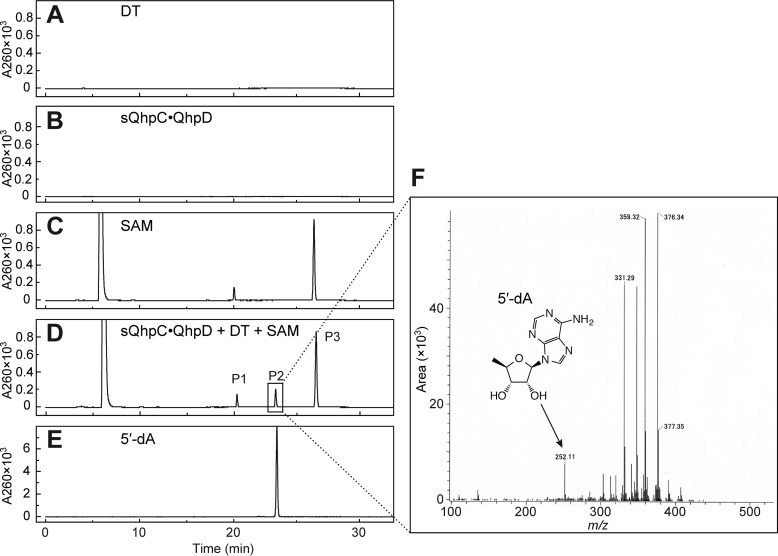

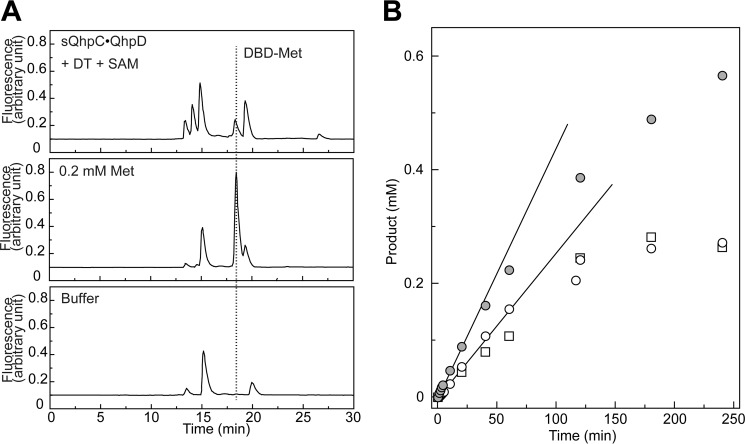

The common activity for most, if not all, radical SAM enzymes reported is the reductive homolytic cleavage of the S–5′C bond of SAM, producing methionine, and the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (5′-dA•) that abstracts a hydrogen atom from the substrate in their respective coupled reactions, or from protein or solvent in the uncoupled reaction, to form the final stable product 5′-deoxyadenosine (5′-dA) (10–12). The reductive SAM cleavage activity of the sQhpC·QhpD complex was determined by measuring both methionine and 5′-dA by liquid chromatography of the reaction mixture. Control experiments indicated that the reaction occurred only when the DT-reduced QhpC·QhpD complex was anaerobically incubated with SAM, yielding a product identifiable as 5′-dA (calculated [M + H]+ = 252.24) by a TOF-MS analysis of the HPLC eluate (Figs. 7 and 8A). The reaction by the sQhpCC7S·QhpD complex continued linearly over 60 min for production of both methionine and 5′-dA with a multiple-turnover rate constant (kcat) of about 0.193 min−1 at 1 mm SAM, when measured immediately after reconstitution (Fig. 8B). This rate is within the range of the reported values for SAM cleavage activities of other radical SAM enzymes, including the SPASM subgroup, such as PqqE (0.011 min−1) (38), anSME from Clostridium perfringens (termed anSMEcpe) (1.09 nmol min−1 mg−1 (= 0.047 min−1)) (15), AtsB (0.32 min−1) (16), and lipoate synthase (0.175 min−1) (39). By measuring the initial rates of 5′-dA production at different SAM concentrations, the apparent Km value for SAM was determined to be 45.3 ± 5.4 μm. The observation that the rate of 5′-dA production with the wild-type sQhpC·QhpD complex was slightly higher than that with sQhpCC7S·QhpD (Fig. 8B) suggests that the SAM cleavage reaction is further stimulated, albeit only by about 30%, when coupled with the following reaction (thioether bond formation). Collectively, these results show that QhpD catalyzes the multiple-turnover reaction of reductive SAM cleavage irrespective of the subsequent coupled reaction, yielding 5′-dA and methionine considerably exceeding the amount of QhpC·QhpD complex used.

FIGURE 7.

Analysis of 5′-dA produced in the SAM cleavage reaction by QhpD. After TCA quenching and removal of the precipitated proteins, the reaction mixtures were analyzed by reversed-phase column chromatography using Cosmosil 5C18-PAQ column (Nacalai Tesque) equipped on an HPLC system: A, DT; B, sQhpC·QhpD; C, SAM; D, sQhpC·QhpD + DT + SAM; E, 5′-dA standard. The elution was monitored at absorbance at 260 nm. F, P2 peak of sQhpC·QhpD + DT + SAM (D) was collected and analyzed by TOF MS. The peaks with masses larger than that of 5′-dA are assumed to be derived from impurities contaminated during the procedure.

FIGURE 8.

Identification of methionine and time course of the product formation in SAM cleavage reaction. A, SAM cleavage reaction was carried out with the sQhpC·QhpD complex (63 μm) in the presence of 1 mm DT and 1 mm SAM for 1 h. The DBD-F-treated samples (sQhpC·QhpD + DT + SAM, 0.2 mm Met, and buffer only) were analyzed by reversed-phase column chromatography using the Cosmosil 5C18-PAQ column equipped on an HPLC system. The elution was monitored by excitation at 450 nm and emission at 590 nm. The elution position of DBD-Met is indicated by a dotted line. B, time course of the SAM cleavage reaction was monitored with the concentrations of products formed (5′-dA and Met), which were calculated by integrating the peak area. Open circles and squares indicate 5′-dA and Met concentrations, respectively, in the reaction with 63 μm sQhpCC7S·QhpD, and gray circles indicate 5′-dA concentrations in the reaction with 63 μm sQhpC·QhpD. Lines represent initial increase of the concentrations of 5′-dA produced.

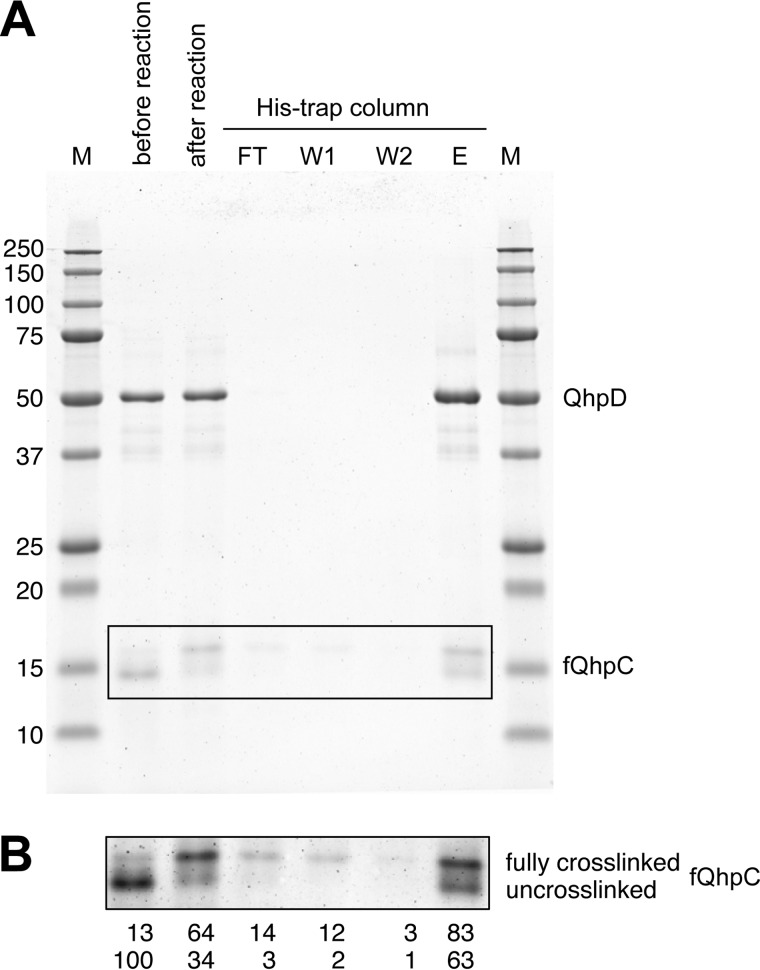

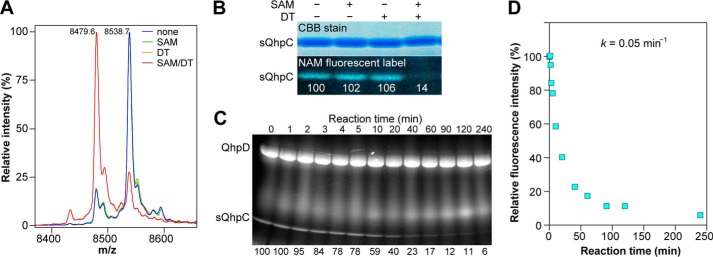

Thioether Bond Formation in the sQhpC·QhpD Complex

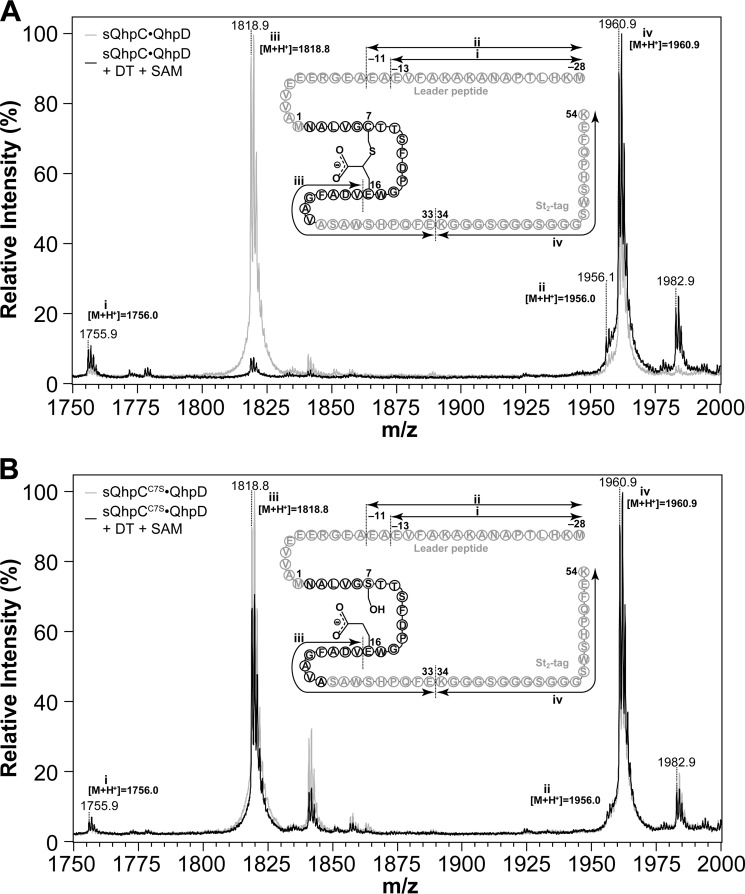

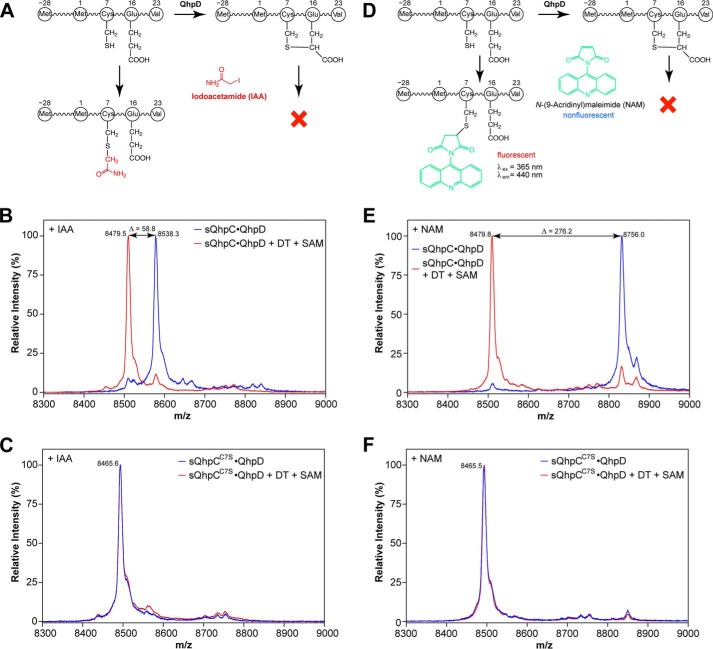

We expected that the formation of thioether bonds within the bound QhpC in the QhpC·QhpD complex would occur in vitro, if the 5′-dA• produced by QhpD in the reductive cleavage of SAM is used efficiently for the subsequent coupled reaction. Because the mass difference before and after the thioether bond formation is only 2 mass units and protein chemical determination of intra-peptidyl thioether bonds is not straightforward (see also Fig. 9A) (40), the reaction was assayed by monitoring the loss of a free sulfhydryl group from a Cys residue by chemical modification with IAA or NAM (Fig. 10, A and D). A similar assay using IAA has been employed previously for the AlbA-catalyzed formation of sulfur-to-α-carbon thioether bonds in subtilosin A (18). Thus, modification of a Cys residue with IAA and NAM gives an overall difference of ∼59 and 276 mass units, respectively, for the molecular ion peaks observed before and after the thioether bond formation (Fig. 10, B and E). Disappearance of the fluorescent band on SDS-PAGE is also a convenient way to assay semi-quantitatively the reaction using NAM that forms a fluorescent conjugate upon reaction with a free Cys residue (Fig. 10D). However, the assay methods using IAA and NAM are both inapplicable to the sQhpCC7S mutant without a free SH group. Nevertheless, exact matching of the mass peaks before and after the reaction (Fig. 10, C and F) and protein chemical analysis (Fig. 9B) revealed that the sQhpCC7S mutant does not undergo ether bond formation between Ser-7 and Glu-16 by QhpD.

FIGURE 9.

MALDI-TOF MS analysis of in-gel digested sQhpC. Mass spectra obtained from sQhpC·QhpD (A) and sQhpCC7S·QhpD (B) before (gray) and after (black) the reaction. Each complex (∼80 μm) was mixed with or without 1 mm DT and 1 mm SAM, and incubated for 1 h for cross-linking reaction. The sQhpC polypeptide was then separated by SDS-PAGE, digested in-gel with Glu-C (Roche Applied Science) and then analyzed with a Bruker Ultraflex III MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer. Schematic structure of sQhpC and sQhpCC7S with identified fragments are shown in the inset. Theoretical monoisotopic m/z values calculated for each fragment ([M + H+]) are also shown near each peak. In the case of the wild-type sQhpC shown in A, the peak height of fragment iii was significantly decreased after the cross-linking reaction, probably due to the inability of Glu-C to cleave the peptide bond next to the cross-linked Glu-16. In contrast in B, such effect was not observed after the reaction, indicating that the C7S mutant does not undergo the ether bond formation between Ser-7 and Glu-16 by QhpD.

FIGURE 10.

Reaction scheme of thiol-modifying reagents used for detection of unreacted free –SH group and MALDI-TOF MS analysis of cross-link formation in sQhpC. Reaction schemes for IAA (A) and NAM (D) and mass spectra for the sQhpC·QhpD (B and E) and sQhpCC7S·QhpD (C and F) complexes modified with IAA (B and C) or NAM (E and F) are shown. Note that sQhpC after undergoing the thioether bond formation would not be modified by these reagents. The reconstituted complexes (∼80 μm) before (blue) and after (red) the reaction with 1 mm DT and 1 mm SAM for 1 h were concentrated by precipitation with TCA, dissolved in 6 m urea in 50 mm potassium phosphate, incubated with 50 mm IAA or 0.5 mm NAM for 1 h, desalted with a C18 ZipTip pipette tip, and subjected to MALDI-TOF MS analysis. Theoretical m/z values (including St2-tag) ([M + H+]) are as follows: IAA-modified (uncross-linked) sQhpC, 8538.42; NAM-modified (uncross-linked) sQhpC, 8755.65; cross-linked sQhpC, 8479.35; uncross-linked sQhpCC7S, 8465.30.

The thioether bond formation was first examined with the purified and reconstituted sQhpC·QhpD complex, where only a single Cys residue (Cys-7) forming a thioether bond is contained in sQhpC. As shown in Fig. 11, A and B, the thioether bond formation (i.e. disappearance of a free SH group) occurred only in the presence of both DT and SAM. The reaction followed pseudo-first order kinetics and proceeded with the disappearance of >80% modifiable Cys residue within 60 min (Fig. 11C), indicating that the thioether bond formation is a single-turnover reaction occurring in the sQhpC·QhpD complex. The pseudo-first order rate constant for the initial 20-min reaction was estimated to be ∼0.05 min−1 (3 h−1) (Fig. 11D), which corresponds to about 26% of the SAM cleavage activity. Although this activity was considerably lower than those of the multiple-turnover reactions catalyzed by other radical SAM enzymes that range from 0.175 min−1 (lipoate synthase) (39) to ∼27 s−1 (lysine 2,3-aminomutase) (41), the low single-turnover activity of QhpD is probably sufficient for the post-translational modification (maturation) of QhpC (γ subunit of QHNDH) coordinated with bacterial cell growth.

FIGURE 11.

Thioether bond formation in sQhpC. A, MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the reaction product (sQhpC) modified with IAA. Predicted mass difference between the acetamidated sQhpC and that containing the Cys-7–Glu-16 thioether bond is 59.1. B, SDS-PAGE analysis of the reaction product modified with NAM. C, time course of the thioether bond formation as monitored by the disappearance of the fluorescent band. B and C, values below the fluorescent band show relative fluorescence intensities. D, plot of fluorescence intensities against reaction time. The method of sample preparation was the same as described in the legend to Fig. 10.

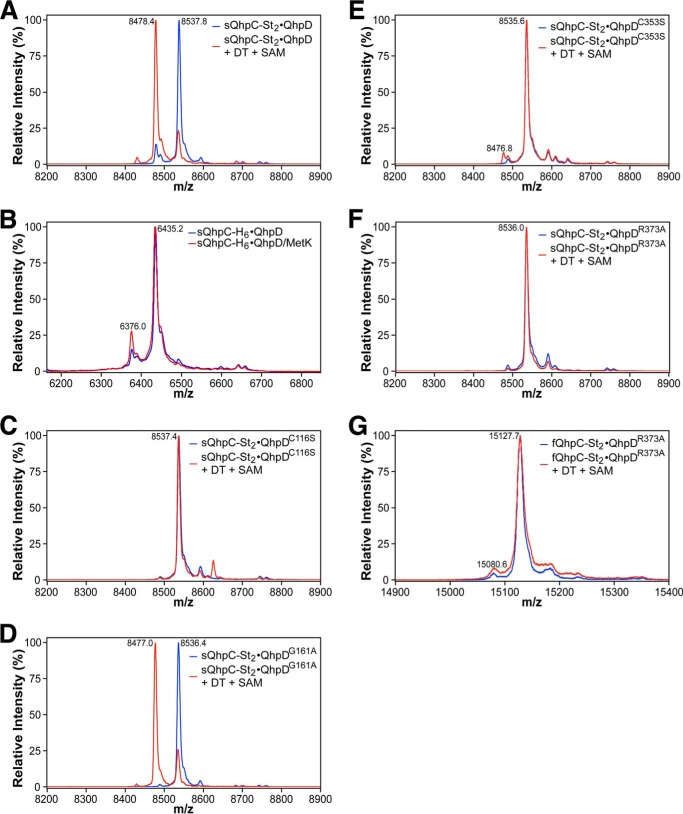

The thioether bond formation in the sQhpC·QhpD complex appeared to occur also in the recombinant E. coli cells, although slightly, as judged from the presence of a small amount of sQhpC that could not be modified with IAA even before the reaction (with a relative peak height corresponding to about 12% of the main peak) (Figs. 11A and 12A). It is assumed that intracellular SAM and a physiological electron donor serving for reduction of the SAM-binding [4Fe-4S] cluster promoted the formation of the thioether bond by QhpD in the recombinant E. coli cells. Supporting this assumption, co-expression of SAM synthetase (MetK) resulted in a significant increase in the amount of sQhpC already containing the thioether bond in the purified QhpD·sQhpC complex (with a relative peak height corresponding to about 26% of the main peak) (Fig. 12B).

FIGURE 12.

MALDI-TOF MS analysis of cross-link formation of QhpC co-expressed with QhpD mutants and MetK. Mass spectra obtained from the reaction mixtures with the sQhpC-St2·QhpD (A), sQhpC-H6·QhpD (B), sQhpC-St2·QhpDC116S (C), sQhpC-St2·QhpDG161A (D), sQhpC-St2·QhpDC353S (E), sQhpC-St2·QhpDR373A (F), and fQhpC-St2·QhpDR373A (G) complexes. B, the as-purified sQhpC-H6·QhpD (blue) and that co-expressed with MetK (red) were used without subjecting to the in vitro reaction. In other panels, the reconstituted complexes before (blue) and after (red) the reaction with 1 mm DT and 1 mm SAM for 1 h were used for analysis. Note that in the sQhpC-St2·QhpDG161A complex (D), the thioether bond formation in E. coli cells (before the in vitro reaction) was almost unobserved as compared with the wild-type sQhpC-St2·QhpD in A. The method of sample preparation was the same as described in the legend to Fig. 10. Theoretical m/z values (including St2-tag or H6-tag) ([M + H+]): IAA-modified (uncross-linked) sQhpC-St2, 8538.42; cross-linked sQhpC-St2, 8479.35; IAA-modified (uncross-linked) sQhpC-H6, 6435.18; cross-linked sQhpC-H6, 6376.11; IAA-modified (uncross-linked) fQhpC-St2, 15129.5.

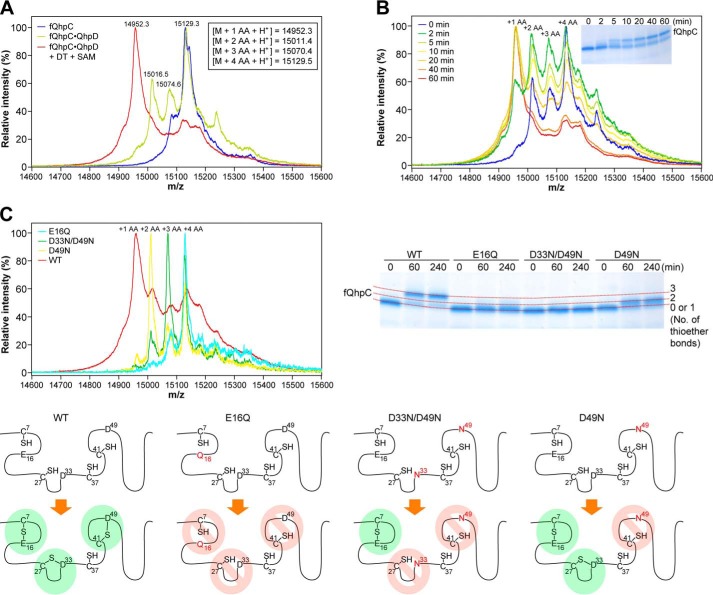

Thioether Bond Formation in the fQhpC·QhpD Complex

We next studied thioether bond formation in fQhpC, which contains three Cys residues (Cys-7, Cys-27, and Cys-41) that are involved in thioether cross-links to the methylene carbon atom of Glu or Asp and one Cys residue (Cys-37), forming the CTQ cofactor (Fig. 1B). When fQhpC was co-expressed with QhpD, the purified fQhpC in the fQhpC·QhpD complex was found to be a mixture of species that contains 2–4 Cys residues reactive with IAA (Fig. 13A, green trace), indicating again that thioether bond formation in fQhpC partially occurs in E. coli cells. The fQhpC without thioether bonds, which contains the full four Cys residues reactive with IAA (Fig. 13A, blue trace), could only be obtained by expression as a single polypeptide or by co-expression with an inactive QhpD mutant (QhpDC116S, as described later) as the QhpC·QhpD complex followed by removal of heat-denatured QhpDC116S (fQhpC is heat-stable). The mixed fQhpC containing 2–4 Cys residues could finally be converted to the form that contains only a single free Cys (Cys-37, which is not involved in the sulfur-to-methylene carbon thioether bonds) by anaerobic incubation with DT and SAM for 2 h (Fig. 13A, red trace). The time course of the reaction measured by MS (Fig. 13B) shows that the reaction in fQhpC practically completes within 1 h. Analysis by SDS-PAGE also indicates the time-dependent formation of fQhpC containing only a single Cys (=3 thioether bonds formed), which is well separated from the initial unmodified polypeptide (Fig. 13B, inset). These results unequivocally show that formation of the sulfur-to-methylene carbon thioether bond is catalyzed by QhpD in the complex with its substrate fQhpC.

FIGURE 13.

Thioether bond formation in fQhpC. A, reconstituted fQhpC·QhpD complex before (yellow green) and after (red) the reaction with 1 mm DT and 1 mm SAM for 2 h and also the fQhpC purified from the fQhpC·QhpDC116S complex (blue) were modified with IAA and analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. Calculated mass values for fQhpC with St2-tag (M) containing 1–4 acetamide (AA) groups with 3–0 thioether bonds are indicated in the inset. B, time course of thioether bond formation in the fQhpC·QhpD complex. The number of 1–4 acetamide groups incorporated is indicated at the top of each peak. Mass spectra of fQhpC at each reaction time are shown in different colors as follows: 0 (blue); 2 (green); 5 (yellow-green); 10 (yellow); 20 (yellow-orange); 40 (orange); and 60 min (red). SDS-PAGE analysis of the reaction product is shown in the inset. C, MS and SDS-PAGE analyses of the order of thioether bond formation using wild-type (WT) and mutants of fQhpC. Mass spectra of E16Q (cyan), D33N/D49N (green), D49N (yellow), and WT (red) fQhpC after the cross-linking reaction for 20 min are shown. Predicted patterns of the thioether bond formation are shown schematically for WT and each mutant. The method of sample preparation was the same as described in the legend to Fig. 10.

Furthermore, to study whether the thioether bond formation occurs from the N- to C-terminal direction (i.e. in the order of Cys-7–Glu-16, Cys-27–Asp-33 and Cys-41–Asp-49) or initiates at any position in the fQhpC sequence, we prepared mutants of substrate fQhpC and reacted these mutants with QhpD in the presence of DT and SAM. The Glu-to-Gln or Asp-to-Asn mutants of fQhpC are expected not to serve as a sulfur acceptor at the methylene carbon atoms, presumably due to the absence of the side-chain carboxyl group that is assumed to interact with the conserved Arg-373 in QhpD, as discussed later. The reaction products after 20-min of incubation with DT and SAM were treated with IAA and analyzed by TOF-MS (Fig. 13C). To confirm the products after a longer reaction time (1–4 h), the products were also analyzed by SDS-PAGE as the position of the stained bands differs depending on the number of thioether bonds present; although the bands without and with one thioether bond cannot be separated (Fig. 13C). The wild-type fQhpC was converted to the major product containing three full thioether bonds (i.e. containing only 1 IAA-reactive SH group), whereas the single fQhpCE16Q and double fQhpCD33N/D49N mutants were unmodified (i.e. containing four IAA-reactive SH groups) or were converted to the product containing only a single thioether bond (i.e. containing three IAA-reactive SH groups) after reaction with QhpD. In contrast, the single fQhpCD49N mutant was converted to the product that contained two thioether bonds (i.e. containing two IAA-reactive SH groups) (Fig. 13C). These results clearly show that thioether bond formation proceeds sequentially in an N- to C-terminal direction in the bound fQhpC but not randomly at any position, as shown schematically in Fig. 13C.

Dissociation of the QhpC·QhpD Complex

An important issue to be addressed is whether the substrate fQhpC dissociates from QhpD or stays bound in the complex during or after formation of the three thioether bonds. This was studied by using a His trap affinity column (Fig. 14A), and most of fQhpC was found to bind in the complex with QhpD even after the three thioether bonds were formed; only a small amount of fQhpC with three thioether bonds was found in the flow-through and the first washing fractions. This result indicates that formation of the three thioether bonds in fQhpC is catalyzed progressively by a single QhpD molecule bound in the same complex (i.e. a single-turnover reaction in terms of fQhpC) and thus suggests the sliding of the fQhpC polypeptide chain along the active site of QhpD during the sequential formation of the three thioether bonds, as discussed below. Quantification of the stained bands of fQhpC (Fig. 14B) also supports that the fully cross-linked fQhpC is only slightly more dissociable from QhpD than the unmodified one. Thus, it is concluded that the substrate fQhpC most probably stays bound in the complex during and after formation of the three thioether bonds, which is certified by the tight binding of the leader peptide of fQhpC to QhpD.

FIGURE 14.

Analysis of the interaction between QhpD and fQhpC before and after the cross-linking reaction. A, reconstituted fQhpC·QhpD (60 μm) (before reaction) was reacted with 1 mm DT and 1 mm SAM for 8 h (after reaction). The reaction mixture (2 ml) was applied to a His trap column (2 ml) (QhpD contained N-terminal H6-tag), and the flow-through (FT, 2 ml), first and second wash (W1 and W2, each 2 ml), and eluted (E, 2 ml) fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (10 μl/lane). The protein bands were stained with colloidal Coomassie G-250 (54). B, enhanced image of the boxed area in A. Band intensities were quantified using the ImageJ program (National Institutes of Health) and are shown below each lane as a percentage relative to the band intensity of uncross-linked fQhpC before the reaction.

Homology-based Structure Modeling of QhpD

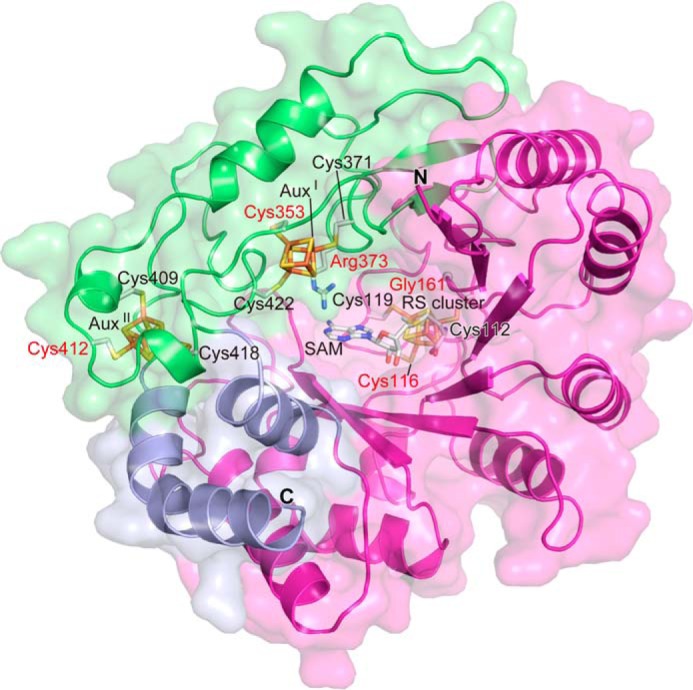

Presumably due to the instability after purification and/or heterogeneity of the bound QhpC, we have not yet succeeded in crystallization of the QhpC·QhpD complex for x-ray diffraction analysis. However, a highly plausible structure model of QhpD could be obtained by homology alignment-based structure modeling (Swiss-Model) (25). Although the crystal structure of anSMEcpe (PDB code 4K36) (17) was auto-selected as the template based on sequence homology, the loop region from Gln-345 to Leu-360, adjacent to one of the predicted auxiliary clusters, had to be manually modified to create sufficient space to accommodate the substrate QhpC peptide segment in the active site. Consequently, Cys-353 of QhpD that corresponded to Cys-255 of anSMEcpe in the initial model was re-aligned to correspond to Cys-261 of anSMEcpe (Fig. 2A) to build the final model, containing residues Ile-99–Asn-463 (Fig. 15); the N-terminal 98 residues that are absent in the anSMEcpe sequence were not included in the model. This model is consistent with the prediction that the majority of radical SAM superfamily enzymes would have a common core fold comprising a partial (α/β)6 triose-phosphate isomerase barrel (42, 43). The lateral opening (an opening on the side) of the triose-phosphate isomerase barrel in the QhpD model is as large as that of anSMEcpe and hence appears to be able to accommodate proteinaceous substrates. Moreover, in addition to the consensus CX3CX2C motif (Cys-112, Cys-116, and Cys-119 in QhpD) that ligates the radical SAM [4Fe-4S] cluster (designated RS cluster) (10–12), seven Cys residues conserved in the C-terminal SPASM domain (Fig. 2B) are ideally positioned to bind two auxiliary clusters (AuxI and AuxII) at sites very similar to those in the anSMEcpe structure. The AuxI cluster in QhpD, however, is ligated by three Cys residues (Cys-353, Cys-371, and Cys-422) unlike in the anSMEcpe structure, in which the auxiliary cluster I is ligated by four Cys residues (17), whereas the AuxII cluster is fully ligated by four Cys residues (Cys-409, Cys-412, Cys-418, and Cys-441) (Fig. 15). Thus, the noncoordinated iron site in the AuxI cluster may bind the substrate as proposed for the formylglycine-generating enzyme AtsB (16), the subtilosin A-synthesizing enzyme AlbA (18), and the molybdenum cofactor biosynthetic enzyme MoaA (44, 45). The RS cluster to AuxI cluster distance is estimated to be 16.3 Å, which is comparable with that (16.9 Å) in the anSMEcpe structure (17).

FIGURE 15.

Homology alignment-based structure model of QhpD. The modeled QhpD structure is shown in ribbon representation with molecular surfaces; the radical SAM, SPASM, and other domains are colored magenta, green, and light blue, respectively. SAM, iron-sulfur clusters (RS, AuxI, and AuxII), and the side chains of Cys residues ligating the clusters and those substituted by site-directed mutagenesis (labeled in red) are shown by stick models.

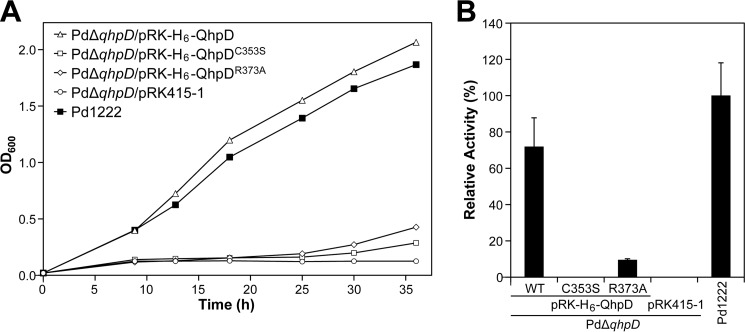

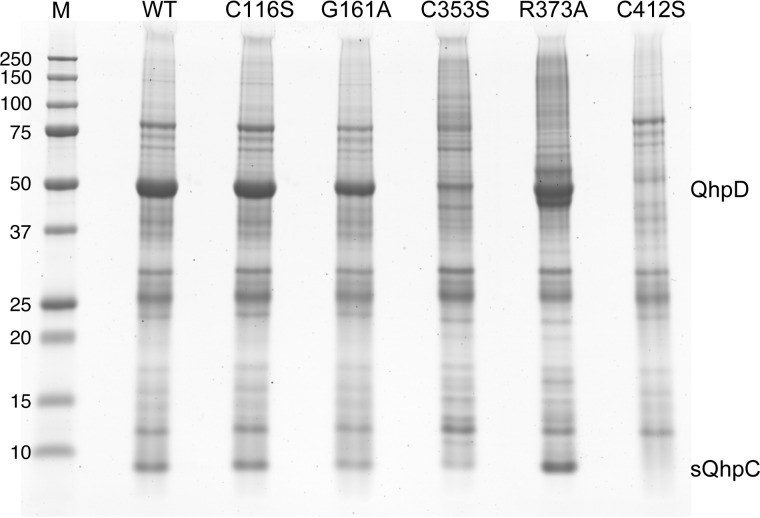

Site-specific Mutagenesis of Conserved Residues

To study the roles of residues strongly conserved in the SPASM subgroup (Fig. 2A), a number of site-specific mutants were prepared for QhpD. The first mutant prepared involved mutating the middle Cys residue (Cys-116) in the N-terminal signature motif (CX3CX2C) into Ser (QhpDC116S). The second mutant prepared replaced the Gly residue (Gly-161) in the GGE motif, predicted to be involved in binding of SAM, with Ala (QhpDG161A). Two Cys residues (Cys-353 and Cys-412) in the 7-Cys motif of the SPASM domain (15) were replaced by Ser (QhpDC353S and QhpDC412S). Finally, Arg-373 that is invariant in QhpD homologs (Fig. 2B) was replaced by Ala (QhpDR373A). We previously reported that the n-butylamine-dependent growth of the ΔqhpD mutant strain of P. denitrificans was not rescued by complementation with a plasmid encoding QhpDC116S, QhpDG161A, or QhpDC412S mutants (7). Using the same method, QhpDC353S and QhpDR373A mutants were also found to be unable to recover the growth of the ΔqhpD strain and to produce active QHNDH (Fig. 16), demonstrating the importance of these conserved residues for the in vivo activity of QhpD.

FIGURE 16.

Bacterial growth and QHNDH activity of the wild-type and qhpD-disrupted mutant of P. denitrificans Pd1222. A, wild-type Pd1222 (■) and qhpD-disrupted mutant PdΔqhpD cells transformed with pRK-H6-QhpD (▵), pRK-H6-QhpDC353S (□), pRK-H6-QhpDR373A (♢), or an empty vector pRK415–1 (○) were grown in minimal medium supplemented with n-butylamine. Cell densities measured by absorbance at 600 nm were plotted against culture time. B, wild-type Pd1222 and mutant PdΔqhpD cells transformed with a plasmid carrying the wild-type or mutant genes (as indicated) were cultured for 36 h in minimal medium containing n-butylamine. To support growth of the gene-disrupted mutant cells, 20 mm choline chloride was added to the culture medium. Preparation of periplasmic and cytoplasmic fractions of P. denitrificans Pd1222 cells and assay of QHNDH activity were performed as described previously (7). QHNDH activities in the periplasmic fraction are shown as relative values compared with that of wild-type Pd1222 cells (100%). Each bar represents the mean ± S.E. from two independent experiments.

Interaction of these QhpD mutants with the co-expressed sQhpC was examined using a His-trap spin column (Fig. 17). Three mutants (QhpDC116S, QhpDG161A, and QhpDR373A) were produced and bound to sQhpC as efficiently as the wild-type QhpD. However, expressions of the QhpDC353S and QhpDC412S mutants were significantly lower and negligible, respectively, suggesting that mutation of Cys-353 and Cys-412 resulted in a significant structural change of QhpD that impaired the interaction with QhpC. Because of negligible protein expression, the QhpDC412S mutant was not analyzed further in subsequent studies.

FIGURE 17.

Interaction of QhpD mutants with QhpC. E. coli was co-transformed with pET-sQhpC-H6 and one of the pBBR-QhpD plasmids (encoding wild-type, C116S, G161A, C353S, R373A, and C412S mutants of QhpD, as indicated). Protein expression and purification, sample preparation, and SDS-PAGE were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 4.

Absorption spectra of the QhpDC116S, QhpDG161A, QhpDC353S, and QhpDR373A mutants co-purified with sQhpC are shown in Fig. 5, together with their iron/sulfur contents. Increases in visible absorption bands as well as iron/sulfur contents observed after reconstitution of the purified complex were similar among the wild-type QhpD and QhpDG161A and QhpDR373A mutants but were considerably greater in the QhpDC116S and QhpDC353S mutants over the wild-type enzyme. These results suggest that in these Cys mutants, additional iron and sulfur atoms are adventitiously bound to surface residues on the protein (21) and/or to the remaining Cys residues in the canonical and auxiliary [4Fe-4S] cluster-binding sites possibly in different chemical structures (12).

The reduced QhpDC116S mutant in the complex with sQhpC exhibited an EPR spectrum considerably different from that of the wild-type QhpD complex, particularly in the g⊥ region showing a broader trough of the derivative type signal with an increased rhombic character (Fig. 6). The shoulder signal at g = 2.075 is still observed in the QhpDC116S spectrum and therefore appears to be derived from AuxI and AuxII. The spectra of the reduced QhpDG161A and QhpDR373A mutants in the complex with sQhpC were very similar to the spectrum of the wild-type QhpD complex, except that the signal at g = 2.075 was almost absent in the QhpDG161A mutant, and the trough at g = 1.900 was considerably shifted to a higher magnetic field, suggesting that the mutation of the SAM- and/or substrate-binding sites also affected the structures of the [4Fe-4S] cluster-binding regions. From the spectrum of the reduced QhpDC353S mutant in the complex, it is likely that the signal around g = 1.92 is derived from AuxII and/or RS clusters that are left in this mutant.

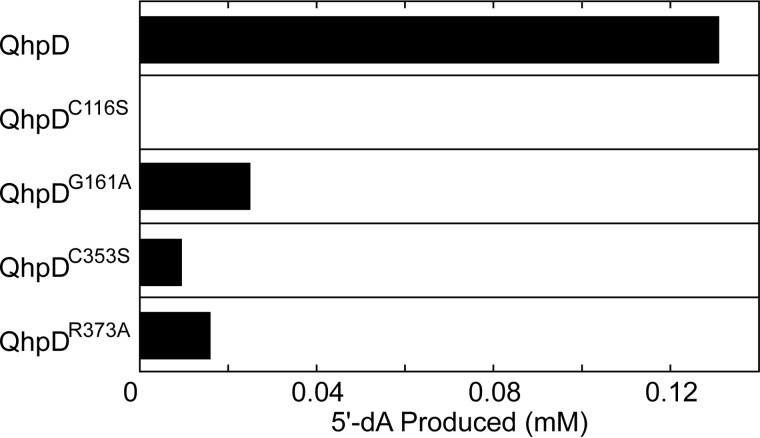

Regarding the SAM cleavage activity, the QhpDG161A mutant had significantly reduced activity (about 20% of the wild-type enzyme), whereas the QhpDC116S mutant showed no activity (Fig. 18), as expected because these residues are involved in binding SAM. It is also interesting to note that even the QhpDC353S and QhpDR373A mutants, both of which are assumed not to directly participate in SAM binding, exhibited very low SAM cleavage activities. Presumably, these residues play allosteric roles in stabilizing the protein architecture necessary for SAM binding and/or cleavage. Alternatively, there is a possibility that electrons are supplied from AuxI and/or AuxII to the RS cluster during the reductive SAM cleavage reaction, as proposed for the role of auxiliary clusters in anSMEcpe (15, 17).

FIGURE 18.

SAM cleavage activity of wild-type and mutant QhpD. The SAM cleavage reaction was carried out at room temperature for 8 h with 63 μm wild-type and mutant enzymes of QhpD in the presence of 1 mm SAM, and the 5′-dA produced was measured by HPLC as described in the legend to Fig. 7. The concentrations of the 5′-dA produced were calculated from the peak area in the HPLC profiles.

The in vitro thioether bond formation was also examined with various QhpD mutants in the complex with sQhpC (Fig. 12, C–F). Unexpectedly, the QhpDG161A mutant exhibited significant activity that was comparable with the wild-type QhpD at 1 mm SAM (Fig. 12D). This observation is apparently inconsistent with the inability of the QhpDG161A mutant to rescue the growth of the ΔqhpD strain of P. denitrificans (7). It is likely that the intracellular concentration of SAM in P. denitrificans is lower than 1 mm and is therefore insufficient for the QhpDG161A mutant to function in vivo; the mutant is probably unable to form thioether bonds in QhpC during the QHNDH maturation in the ΔqhpD strain. Conversely, the QhpDC116S, QhpDC353S, and QhpDR373A mutants had no thioether bond forming activity (Fig. 12, C, E, and F), as predicted from their no or negligible SAM cleavage activities (Fig. 18) that should provide 5′-dA• needed for the subsequent thioether bond formation. It is noteworthy that the QhpDR373A mutant was unable to form thioether bonds not only in sQhpC but also in fQhpC (Fig. 12G).

DISCUSSION

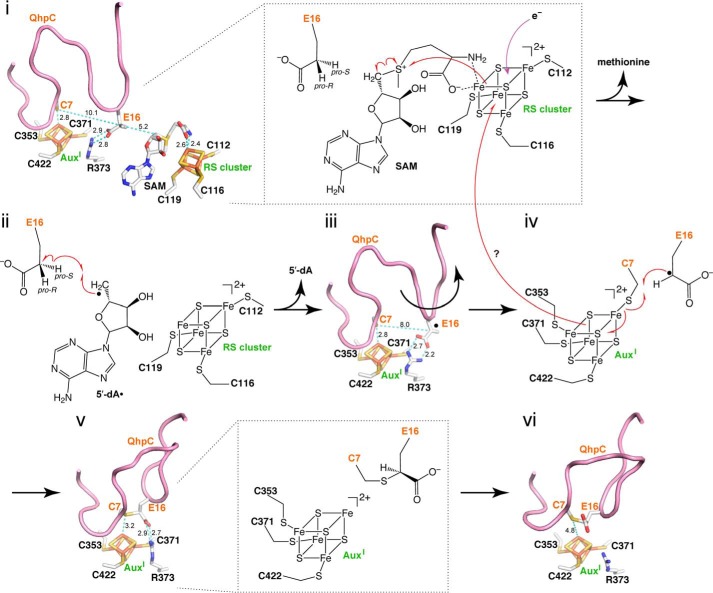

In this study, we have demonstrated that the radical SAM enzyme QhpD catalyzes the sequential formation of sulfur-to-methylene carbon thioether bonds of its protein substrate QhpC in the presence of an artificial reducing agent (DT) and SAM. The intra-protein thioether bond formation is a chemically challenging reaction, accompanying the removal of a hydrogen atom from an inert methylene carbon atom of Asp and Glu residues with high bond dissociation energies for homolytic cleavage (394.8 and 418.6 kJ/mol, respectively) (46). These values are even higher than those of α-hydrogen atoms of a polypeptide chain, which are abstracted in the sulfur-to-α-carbon thioether bond formation by analogous radical SAM enzymes AlbA and SkfB (18, 19), requiring 345.1, 348.9, and 338.9 kJ/mol for α-H abstraction from Thr, Phe, and Met, respectively (46).

Based on the spectral properties of the purified and reconstituted QhpC·QhpD complex and the results of site-specific mutagenesis of conserved Cys residues, the presence of multiple (most likely three) [4Fe-4S] clusters (RS, AuxI, and AuxII) in QhpD is strongly suggested, as also predicted from homology modeling of the QhpD structure (Fig. 15). However, except for the canonical role of the RS cluster that binds SAM and reductively cleaves it into methionine and 5′-dA•, the roles of the AuxI and AuxII clusters remain inconclusive. Decreased binding of the QhpDC353S mutant with substrate QhpC (Fig. 17) and loss of thioether bond forming activity (Fig. 12E) both support the role of the AuxI cluster in binding of protein substrate. In addition, AuxI may also act as an electron acceptor from substrate and transfer the accepted electron to the RS cluster during the thioether bond formation, as proposed below. In the QhpD model (Fig. 15), the AuxII cluster is located rather close to the molecular surface and behind the predicted binding region for the leader peptide of QhpC (see below); mutation of one of the AuxII cluster-ligating Cys residues (Cys-412) completely abolishes the interaction with QhpC (Fig. 17), suggesting a structural role to support the stable QhpC·QhpD complex. Arg-373 that is completely conserved in the QhpD homologs (Fig. 2B) is located in the vicinity of the AuxI cluster and assumed to be involved in electrostatic binding of acidic residues (Asp or Glu) of substrate QhpC; the anchoring of the carboxyl group of Asp/Glu is likely to be essential for thioether bond formation by QhpD (Figs. 12, F and G, and 13C). We also noted the presence of a large groove consisting of highly conserved and positively charged residues (including above mentioned Arg-373) in the QhpD model, which has sufficient space to accommodate the core QhpC polypeptide containing several negatively charged residues, as depicted in Fig. 19, A and B (see also supplemental Movie). The RS and AuxI clusters are harbored in the bottom of this groove, thus constituting the active site of QhpD.

FIGURE 19.

Structure modeling of the QhpC·QhpD complex. A, sequence conservation is mapped onto the molecular surfaces of the models of QhpD and QhpC, colored in gradation from white to green, corresponding to the score of 0.5 (nonconserved) and 1.0 (fully conserved), respectively. The conservation score was calculated using Scorecons (55) with all QhpD and QhpC homologs (∼270 sequences) identified by a BLAST search. B, electrostatic surface potential is mapped onto the modeled QhpD surface, colored in gradation from red (−5 kT) to blue (+5 kT), where k is Boltzmann's constant and T is the absolute temperature, based on the calculation by PyMOL (Schrödinger, LLC) and APBS (56). C, predicted interactions between the leader peptide of QhpC and surface residues of QhpD. Residue numbers of QhpC and QhpD are indicated in red and black, respectively. Sequence conservation is also shown as in A. D, modeled structures of the fQhpC·QhpD complexes during the processive reaction along the fQhpC polypeptide are shown in ribbon representation with molecular surfaces of QhpD (green ribbon). The leader and the core peptides of QhpC are colored orange and magenta, respectively. SAM, iron-sulfur clusters, thioether bonds, and their precursor residues are shown by stick models. Modeled structures of the cross-linked segments, Cys-7–Glu-16 in step II, Cys-7–Glu-16 and Cys-27–Asp-33 in step III, Cys-7–Asp-33 and Cys-41–Asp-49 in step IV, and the fully cross-linked core peptide in step V of fQhpC were adopted from the coordinate of γ subunit (maturated QhpC) in the QHNDH crystal structure with other regions built and refined using the regularize zone module in Coot (26) to improve model stereochemistry. All molecular drawings were generated using PyMOL.

Precursors of most ribosomally translated natural products such as antibiotics contain an N-terminal leader extension in addition to the C-terminal core peptide that is processed to the final mature compound by post-translational tailoring reactions (47). Likewise, QhpC contains the 28-residue leader peptide that is essential for stable binding with QhpD (Fig. 4A). The leader peptides in general show high sequence conservation as compared with the core peptides with greater sequence variability. However, the leader peptide of QhpC is less conserved than the mature protein region (Fig. 20A) that undergoes the multiple thioether bond formation by QhpD, indicating that QhpD has rigorous sequence specificity for protein substrate but is rather tolerant for the leader peptide sequence. Although the details as to how leader peptides of natural products are recognized by the processing enzymes are largely unknown, it has been noted that many leader peptides have a propensity to form amphipathic α-helices, either in solution or when bound to the enzymes (47). A major part of the 28-residue leader peptide of QhpC is indeed assumed to form α-helices by secondary structure prediction (Fig. 20B). Thus, it appears very likely that formation of the stable complex between QhpC and QhpD is facilitated through binding of the putative α-helix of the QhpC leader peptide to a small groove located above the AuxII cluster and connected to the large groove with some specified ionic interactions between the conserved residues of QhpC and QhpD (Fig. 19, A–C). There is an additional possibility that about 100 N-terminal residues of QhpD that are not included in the model may also interact with the leader peptide, particularly at the conserved N-terminal portion including the invariant Lys(−19) (Fig. 20A).

FIGURE 20.

Multiple sequence alignment of QhpC homologs and secondary structure prediction. A, multiple sequence alignment was conducted using the program ClustalW (51) for QhpC homologs from the following: A. aneurinilyticus (Aan, GenBank gi:545381876); A. butzleri (Ab, gi:157736728); A. japonica (Aja1, gi:518449973; Aja2, gi:518449965); Arcobacter sp. L (Arco, gi:384171424); A. aromaticum (Aro1, gi:56478379; Aro2, gi:56476666); Azoarcus sp. BH72 (Azo, gi:119897532); B. azotoformans (Baz, gi:489426249); B. cepacia (Bce, gi:402569816); B. massiliensis (Bma, gi:517950088); Burkholderia sp. TJI49(Burk, gi:325526528); C. salinarum (Csa, gi:497227881), Citreicella sp. SE45 (Csp, gi:260426667); D. toluolica (Dto, gi:408418099); G. electrodiphilus (Gel, gi:522163449); G. thermoglucosidasius (Gth, gi:617767740); Halomonas sp. KM-1 (Halo, gi:498311925); P. ferrooxidans (Ln, gi:224823977); Magnetospirillum sp. SO-1 (Magn, gi:452962999); M. perideroedes (Mpe, gi:517463416); M. stanieri (Mst1, gi:498009606; Mst2, gi:498009579); M. universalis (Mu, gi:334132771); N. aromaticivorans (Na, gi:87201042; N. nitrogenifigens (Nn, gi:326387245); N. caesariensis (Osp1, gi:89094964; Osp2, gi:89093840); Paracoccus sp. TRP (Para, gi:498081305); P. denitrificans (Pd, gi:119384442); P. gilvum (Pg, gi:328544105); P. gallaeciensis (Pga, gi:518127692); Ps. aeruginosa (Psae1, gi:544781830; Psae2, gi:544782759). Ps. alcaligenes (Psal, gi:544800896); Ps. chlororaphis (Pscl, gi:496335659; Pscla, gi:647806188); Ps. denitrificans (Psde, gi:472325483); Ps. entomophila (Pse, gi:104782042); Ps. sp. FGI182 (Pseu, gi:568240124); Ps. fluorescens (Psf, gi:77459198); Pseudogulbenkiania sp. NH8B (Psgb, gi:347540001); Ps. putida (Psmo, gi:431802844); Ps. putida (Psp, gi:24985112); Ps. plecoglossicida (Pspl, gi:511101188); Ps. protegens (Pspr, gi:346643116); Ps. pseudoalcaligenes (Psps, gi:489543546); Ps. resinovorans (Psre, gi:512618902); Ps. thermotolerans (Psth1, gi:516562569; Psth2, gi:648454818); R. bacterium (Rb, gi:254467679); S. aggregata (Sa, gi:118588650); S. ummariense (Sum, gi:544909903); S. xenophagum (Sxe, gi:515748628); S. yanoikuyae (Sya, gi:490321473); T. aminoaromatica (Ta1, gi:479298786; Ta2, gi:479297320); T. disciformis (Tdi, gi:521061978); T. linaloolentis (Tli1, gi:490477634; Tli2, gi:490475210); T. phenylacetica (Tph, gi:490494487); Thauera sp. MZ1T (Tsp1, gi:217969196; Tsp2, gi:237653642); and α-proteobacterium LLX12A (llx12, gi:516070888). Identical and highly conserved residues are shown by white letters on red background and red letters boxed in blue, respectively. The figure was produced using ESPRIPT (52). B, amino acid sequence of QhpC(−28)−12was used as a query for secondary structure predictions, and the results are graphically displayed with arrows and cylinders for β-strands and α-helices, respectively.