Abstract

It is evident from previous reports that 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), like other known plant growth regulators, is effective in countering the injurious effects of heavy metal-stress in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). The present study was carried out to explore the capability of ALA to improve cadmium (Cd2+) tolerance in B. napus through physiological, molecular, and proteomic analytical approaches. Results showed that application of ALA helped the plants to adjust Cd2+-induced metabolic and photosynthetic fluorescence changes in the leaves of B. napus under Cd2+ stress. The data revealed that ALA treatment enhanced the gene expressions of antioxidant enzyme activities substantially and could increase the expression to a certain degree under Cd2+ stress conditions. In the present study, 34 protein spots were identified that differentially regulated due to Cd2+ and/or ALA treatments. Among them, 18 proteins were significantly regulated by ALA, including the proteins associated with stress related, carbohydrate metabolism, catalysis, dehydration of damaged protein, CO2 assimilation/photosynthesis and protein synthesis/regulation. From these 18 ALA-regulated proteins, 12 proteins were significantly down-regulated and 6 proteins were up-regulated. Interestingly, it was observed that ALA-induced the up-regulation of dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, light harvesting complex photo-system II subunit 6 and 30S ribosomal proteins in the presence of Cd2+ stress. In addition, it was also observed that ALA-induced the down-regulation in thioredoxin-like protein, 2, 3-bisphosphoglycerate, proteasome and thiamine thiazole synthase proteins under Cd2+ stress. Taken together, the present study sheds light on molecular mechanisms involved in ALA-induced Cd2+ tolerance in B. napus leaves and suggests a more active involvement of ALA in plant physiological processes than previously proposed.

Introduction

Heavy metals such as cadmium, lead and chromium are almost persistent environmental pollutants. Among them, cadmium (Cd2+) is highly toxic [1], and has greater hazardous impact on ecosystem. Its different sources are pesticides and chemical fertilizers, which easily release Cd2+ into our environment. It belongs to a group of metals, which are water soluble [2, 3]. Among the well-known phyto-toxic heavy metals in the environment, Cd2+ is of considerable importance due to its high water solubility, mobility, persistence, and toxicity even in minute amounts [4]. Using roots as medium of entry, Cd2+ enters our food chains and causes serious human health problem such as cancer.

The oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) is a worldwide source of edible oil [5]. Brassica species are generally considered as tolerant to heavy metal, due to their fast growth, more biomass and ability to absorb heavy metals [6]. Brassica plants adopt different strategies to overcome or tolerate metal toxicity by specific mechanisms in heavy metal contaminated soils [7].

The toxicity effects of Cd2+ in plants have been extensively studied, although several questions remain unaddressed [8]. Symptoms of Cd2+ toxicity in plants include growth inhibition and the disruption of physiological processes [9]. Plants have evolved mechanisms for alleviating and/or tolerating heavy metal stress, including Cd2+ stress, some of which include: exclusion, compartmentalization, complexation/sequestration by small molecules such as phytochelatins (PCs), and the synthesis of stress-response proteins [4]. Cd2+ causes several toxicity symptoms in plants at various functional levels such as physiological, biochemical and proteomic. Physiological disturbances such as water transport, absorption and transport of essential elements, oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria, photosynthesis, respiration, chlorophyll content, plant growth and reproduction in plants have been reported [10]. Cd2+ also disturbs different metabolic processes and can cause decline of water and nutrient uptake in plants [11]. Plants contain antioxidative mechanisms to avoid the oxidative stress such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and peroxidase (POD) as well as glutathione, carotenoids and ascorbate [12]. In plants, SOD dismutase’s the O2 - to H2O2, and CAT scavenges the H2O2, which is generated from photorespiration [13]. POD utilizes H2O2 in the oxidation of different organic and inorganic substrates and it is located in vacuole, cell wall as well as in extracellular spaces [14].

The plant growth regulators (PGRs) are often used to increase the stress tolerance of plants. Similarly, 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) is one of most important plant growth regulator, which is known as essential precursor for the biosynthesis of tetrapyrrols like protochlorophyllide (that is converted in chlorophyll when exposed to light) [15, 16]. In previous research, we found that ALA alleviates the Cd2+ toxicity by improving the plant growth and ultrastructural changes in oilseed rape [16]. Moreover, Wang et al. [17] also showed that treatment of ALA exercised a positive effect on the growth of Brassica campestris seedlings. Recently, it was observed that ALA improved the osmotic potential and relative water content in B. napus under salinity stress. Moreover, it was also found that soluble sugar and free amino acid contents were enhanced with the application of exogenous ALA in B. napus under salinity stress [18].

It is evident from a number of previous reports that ALA, like other known PGRs, is effective in countering the injurious effects of various abiotic stresses on plants, but the information regarding the molecular mechanisms about the question how ALA regulates plant growth under stressful situation are not fully elucidated yet. Proteomic study is achieving great recognition as a reliable and reproducible high-through put approach in understanding biological processes under various environments [19]. It is based on the systematic analysis and documentation of expressed proteins and their study at the functional level [20]. The present experiment is designed to study the comprehensive knowledge about the mechanisms how ALA regulates the physiological, metabolic and proteomic changes in leaves of B. napus under Cd2+ stress.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

For the experiment, seeds of winter Brassica napus L. cv. ZS 758 were obtained from the College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University. The seeds were grown in plastic pots (170 mm×220 mm) filled with peat moss. At five leaf stage, morphologically uniform seedlings were selected and plugged these seedlings into plate holes on plastic pots (six plants per pot) containing a half strength Hoagland nutrient solution [21], aerated continuously with an air pump, in the greenhouse. The composition of Hoagland nutrient solution was as follows (in μmol/L): 3000 KNO3, 2000 Ca(NO3)2, 1000 MgSO4, 10 KH2PO4, 12 FeC6H6O7, 500 H3BO3, 800 ZnSO4, 50 Mncl2, 300 CuSO4, 100 Na2MoO4. The pH of solution was maintained at 6.0. The light intensity was in the range of 250–350 μmol m-2 s-1, temperature was16–20°C and the relative humidity was approximately 55–60%. Each treatment was replicated four times. The nutrient solution was renewed every 5 days.

After acclimatization period of seven days, Cd2+ as CdCl2 was added into full-strength Hoagland solution making desired Cd2+ concentrations (0, 100 and 500 μM) and plants were simultaneously sprayed with or without an aqueous solution of ALA (Cosmo Oil Co. Ltd., Japan) at a concentration of 25 mg/L ALA. The treatment concentrations were based on pre-experimental studies, in which several lower and higher levels of metal were used, i.e., 100, 200, 300, 400, 500 and 1000 μM of CdCl2. The Cd2+ at 100 μM showed a little damage on plant growth and 500 μM Cd2+ imposed a significant damage to plant growth, while those higher than 500 μM were too toxic for plant growth. It was similar in the case of ALA application, where plants exhibited optimum response with the treatment of 25 mg/L concentration under Cd2+ stress conditions [16, 22]. The lower, as well as the upper leaf surfaces were sprayed until wetted with a hand-held atomizer, as it was reported that absorption by the lower leaf surface is rapid and effective [23]. After the five days of first spray, subsequent application was followed. Plants sprayed with distilled water served as the control. Fifteen days after treatment, samples for biochemical, metabolic and proteomic studies of leaf were collected as described below.

Osmotic potential and relative water content

The leaves for the measurement of leaf osmotic potential (ψ s) were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C. The samples were thawed for 30s, which provided 10 μL of sap that was used for the determination of osmotic potential according to Gucci et al. [24] using a vapor pressure osmometer (Wescor Inc., Logan, UT, USA).

The relative water contents (RWC) were determined in fresh leaves, excluding midrib. Samples were weighed quickly and immediately floated on double distilled water, in Petri dishes to saturate them with water for the next 24 hr, in dark. The excessive water was blotted and turgor weight was taken. Dry weight of these samples was obtained, after dehydrating them at 70°C for 48 hr. RWC were calculated by placing the observed values in the following formula:

Soluble sugar, free amino acid and proline contents

The soluble sugars contents were estimated as reported by Zhang et al. [15]. Fresh leaves were boiled in distilled water in water bath for 30 min and then centrifuged at 2,000 g for 15 min. The supernatants were used for the sugar analysis by using spectrophotometric method. After that, soluble sugar concentration was determined. Total free amino acids were estimated according to the method of Yemm and Cocking [25]. One mL of amino-acid solution was mixed with 2 mL sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.5) and 1 mL freshly prepared ninhydrin reagent. The resulting color was determined at 570 nm.

The proline contents in fresh leaves were determined by adopting the method of Bates et al. [26]. Samples were extracted with sulfo-salicylic acid. In the extract, an equal volume of glacial acetic acid and ninhydrin (1.25 g ninhydrin, 30 mL of glacial acetic acid, 20 mL of 6 M H3PO4) solutions were added. The samples were incubated at 100°C for 40 min, to which 3 mL of toluene was added. The absorbance of the toluene layer was read at 520 nm, on a spectrophotometer. After that, proline concentration was determined.

Measurements of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

Photochemical quenching parameters (F0, Fm, Fm´ and Fv/Fm) were measured using an imaging pulse amplitude-modulated (PAM) fluorimeter (IMAG-MAXI; Heinz Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). The F0 is minimal fluorescence yield when the PSII reaction center is open. The Fm is maximal fluorescence yield at the time of closure of PSII reaction center. The Fm´ is the maximal fluorescence in the light-adapted state. The Fv/Fm is the photochemical efficiency of PS II and is used as basic tool in plant photosynthetic activity. In order to measure these parameters, expanded leaves were first dark adaptation for 15 min. Then, all measurements were taken from the same leaf. There were three replications and then three leaves were randomly selected of three different plants from each replication. Measurements for each parameter on a single leaf were done at five different locations and their means were calculated. Thus, for every replication, the means were calculated for 15 different locations of the three different leaves.

Determination of relative electrolyte leakage (REL)

Plasma membrane integrity in roots was assessed in terms of relative electrolyte leakage (REL). Root tissues (100 mg) were cut into small pieces and vibrated for 30 min in deionized water followed by measurement of conductivity of bathing medium (EC1). The samples were again boiled for 15 min and second conductivity was measured (EC2) [27]. Total electrical conductivity was calculated by using the following formula.

Determination of antioxidant enzyme activities

For enzyme activities, leaf samples (0.5 g) were homogenized in 8 mL of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) under ice cold conditions. Homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 min at 4°C and the supernatant was used for the determination of the following enzyme activities. The assay for ascorbate peroxidase (APX, EC 1.11.1.11) activity was measured in a reaction mixture of 3 mL containing 100 mM phosphate (pH 7), 0.1 mM EDTA-Na2, 0.3 mM ascorbic acid, 0.06 mM H2O2 and 100 μL protein extract. After 30 s of addition of H2O2, change in absorption was taken at 290 nm [28]. Catalase (CAT, EC 1.11.1.6) activity was measured according to Aebi [29] with the use of H2O2 (extinction co-efficient 39.4 mM cm-1) for 1 min at A240 in 3 mL reaction mixture containing 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 2 mM EDTA-Na2, 10mM H2O2 and 100 μL protein extract. Glutathione reductase (GR, EC 1.6.4.2) activity was assayed by Jiang and Zhang [30], where NADPH oxidation was followed at 340 nm. The reaction mixture was comprised of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 2 mM EDTA-Na2, 0.15 mM NADPH, 0.5 mM GSSG and 100 μL enzyme extract in a 1 mL volume. The reaction was started by using NADPH.

Total superoxide dismutase (SOD, EC 1.15.1.1) activity was determined with the method of Zhang et al. [31] following the inhibition of photochemical reduction due to nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT). The reaction mixture was comprised of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 13 mM methionine, 75 μM NBT, 2 μM riboflavin, 0.1 mM EDTA and 100 μL of enzyme extract in a 3-mL volume. One unit of SOD activity was measured as the amount of enzyme required to cause 50% inhibition of the NBT reduction measured at 560 nm. Peroxidase (POD, EC1.11.1.7) activity was assayed by Zhou and Leul [32] with some modifications. The reactant mixture contained 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 1% guaiacol, 0.4% H2O2 and 100 μL enzyme extract. Variations due to guaiacol were measured at 470 nm.

Total RNA extraction and gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from ~100 mg of leaf and root tissues using manual (Trizol) method. Prime Script RT reagent kit (Takara Co. Ltd) with gDNA eraser was used to remove the genomic DNA and cDNA synthesis. cDNA samples from different treatments were assayed by quantitative real time PCR (RT-qPCR) in the iCycler iQ Real-time detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using SYBRPremix Ex Taq II (Takara Co. Ltd). The PCR conditions consisted denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C 30 s, annealing at 58°C for 45 s and finally extension at 72 s for 45 s. Gene-targeting primers were designed based on mRNA or expressed sequence tag (EST) for the corresponding genes as follows: SOD (F: 5′ ACGGTGTGACCACTGTGACT 3′, R: 5′ GCACCGTGTTGTTTACCATC3′), POD (F: 5′ATGTTTCGTGCGTCTCTGTC3′, R: 5′ TACGAGGGTCCGATCTTAGC 3′), CAT (F: 5′ TCGCCATGCTGAGAAGTATC 3′, R: 5′ TCTCCAGGCTCCTTGAAGTT 3′), APX (F:5′ ATGAGGTTTGACGGTGAGC 3′, R:5′ CAGCATGGGAGATGGTAGG 3′), GR (F: 5′ AAGCTGGAGCTGTGAAGGTT 3′, R: 5′ AGACAGTGTTCGCAAAGCAG 3′), and Actin gene (F: 5′ TTGGGATGGACCAGAAGG 3′, R: 5′ TCAGGAGCAATACGGAGC 3′) as an internal control. The software given with the PCR system was used to calculate the threshold cycle values and quantification of mRNA levels was performed according to the method of Livak and Schmittgen [33]. The threshold cycle (Ct) value of actin was subtracted from that of the gene of interest to obtain ΔCt value. Brassica napus actin gene 2.1 (FJ529167) was used as an internal control.

Protein extraction, visualization and identification studies

Soluble protein extraction and 2-DE analysis

For proteomic study, two biological independent replicates were used throughout the experiment. Total soluble proteins were extracted as described by Carpentier et al. [34] with minor modification using phenol extraction method. Concentration was determined as according to Bradford [35]. Proteins were separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE), and the protein spots in analytical gels were visualized by silver staining method.

Protein visualization, image analysis, and quantification

Protein visualization, image analysis, and quantification were done as followed by Bah et al. [36]. Briefly, PowerLook1100 scanner (UMAX) was used for scanning and calibration of the protein spots. Only those with significant and reproducible changes (P≤0.05) were considered to be differentially accumulated proteins. The target protein spots were automatically excised from the stained gels and digested with trypsin using a Spot Handling Workstation (Amersham Biosciences). Peptides gel pieces were placed into the EP tube and washed with 1:1 mixture of 50 μL of 30 mM K3Fe(CN)6 and 100 mM NaS2O3 for 10–15 min until completely discolored then washed with 200 μL bi-distilled water (two times for 5 min each). The washed solution was drained and gel slices washed with 50% CAN (acetonitrile, Fisher A/0626/17) and 100% ACN rotationally, and then incubated in 25 mM NH4HCO3 (Sigma A6141) for 5 min at 37°C. After absorbance of incubation solvent, 50% ACN and 100% ACN was rotationally added and dried at 40°C for 5 min respectively.

Trypsin digestion was carried out as follows: sequencing-grade porcine trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was suspended in 25 mM NH4HCO3 at a concentration of 12.5ng/μL used to rehydrate the dried gel pieces. The trypsin digestion was carried out for 16 hr at 37°C. Peptides were extracted from the digest as follows for three times: 10 μL of 50% ACN containing 0.1% TFA (trifluoroacetic acid, GE HealthCare) was added to each tube and incubated for 5 min at 37°C and transferred the supernatants to new EP tube. The extracts were pooled and then vacuum concentrated for about 2 hr. A solution of peptides was filtrated via Millipore (Millipore ZTC18M096) and mixed with the same volume of a matrix solution consisting of saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) in 50% ACN containing 0.1% TFA.

After the peptides were co-crystallized with CHCA by evaporating organic solvents, tryptic-digested peptide masses were measured using a MALDI-TOF-TOF mass spectrometer (ABI4700 System, USA). All mass spectra were recorded in positive reflector mode and generated by accumulating data from 1000 laser shots. The following threshold criteria and settings were used: detected mass range of 700–3200 Da (optimal resolution for the quality of 1500 Da), using a standard peptide mixture (des-Argl-Bradykinin Mr904.468, Angiotensin I Mr1296.685, Glul-Fihrinopeptide B Mr1570.677, ACTH (1–17) Mr2093.087, ACTH (18–39) Mr2465.199; ACTH (7–38) Mr3657.929) as an external standard calibration, with laser frequency of 50 Hz, repetition rate of 200 Hz, UV wavelength of 355 nm, and accelerated voltage of 20,000 V. Peptide mass fingerprint data were matched to the NCBInr database using Profound program under 50 ppm mass tolerance.

Peptide and protein identification by database search

Data were processed via the Data Explorer software and proteins were unambiguously identified by searching against a comprehensive non-redundant sequence database using the MASCOT software search engine (http://www.matrixscience.com/cgi/search%20form.pl?FORMVER=2&SEARCH=MIS). Moreover, in order to evaluate protein identification, we considered the percentage of sequence coverage, the observation of distribution of matching peptides (authentic hit is often characterized by peptides that are adjacent to one another in the sequence and that overlap), the distribution of error (distributed around zero), the gap in probability and score distribution from the first to other candidate; only matches with over 90% sequence identity and a maximum e-value of 10-10 were considered.

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed by using a statistical package, SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A two-way variance analysis (ANOVA) was carried out, followed by the Duncan’s multiple range test.

Results

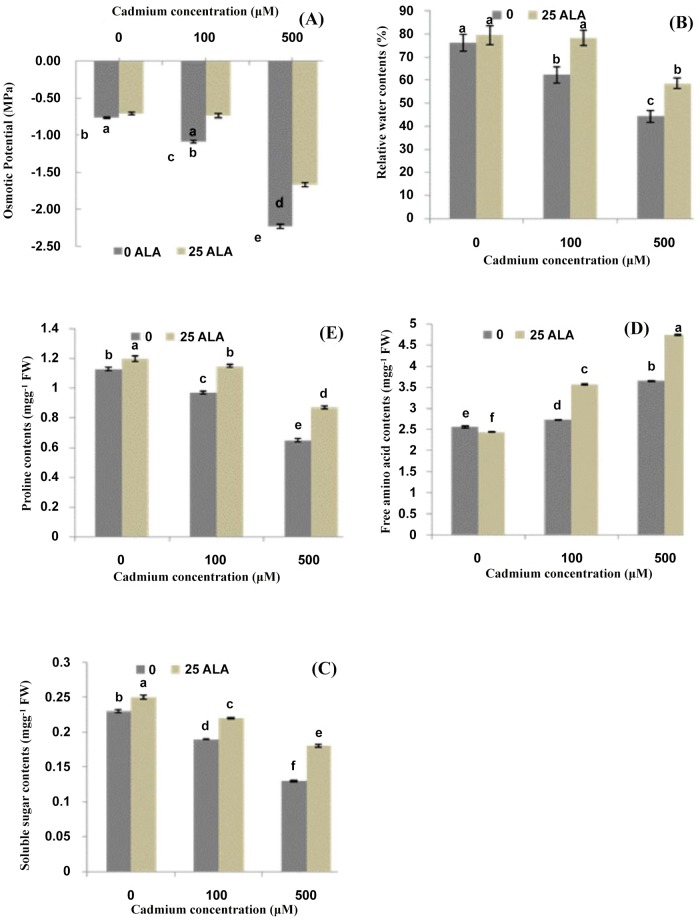

ALA improves metabolic changes under Cd stress

The present study demonstrated that leaf osmotic potential and relative water contents decreased with an increase in cadmium (Cd2+) concentrations (Fig 1A and 1B). However, exogenous application of ALA helped the plants to adjust osmotic potential and relative water contents. The plants treated with 100 μM Cd2+ recovered completely, and those treated with 500 μM also significantly recovered with the application of ALA. Results showed that Cd2+ stress alone significantly lowered the soluble sugar contents in B. napus leaves as compared to control (Fig 1C). This decrease was (18% and 43%) under different treatments of Cd2+ (100 and 500 μM) respectively as compared to control plants. Meanwhile, foliar application of ALA significantly improved soluble sugar contents in B. napus leaves under both Cd2+ stress levels. Moreover, the plants treated with Cd2+ stress alone showed a significant increase in free amino acids contents in B. napus leaves (Fig 1D). At the same time, exogenously applied ALA showed a synergetic affect and it further improved the free amino acids contents in the leaves of B. napus under Cd2+ stress. Moreover, it was found that that Cd2+ stress alone significantly reduced the proline contents in B. napus leaves (Fig 1E). Besides, the application of ALA significantly improved the proline contents in the leaves of B. napus under different Cd2+ stress levels. Moreover, ALA alone significantly enhanced the proline contents in the leaves of B. napus as compared to control plants.

Fig 1. Effects of different treatments of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) (mg/L) and cadmium (Cd2+) (μM) on (A) osmotic potential (MPa), (B) relative water contents (%), (C) soluble sugar contents (mg g-1 FW), (D) free amino acid contents (mg g-1 FW) and (E) proline contents (mg g-1 FW) in the leaves of Brassica napus cv. ZS758.

Values are the means ± SD of three replications. Variants possessing the same letter are not statistically significant at P < 0.05.

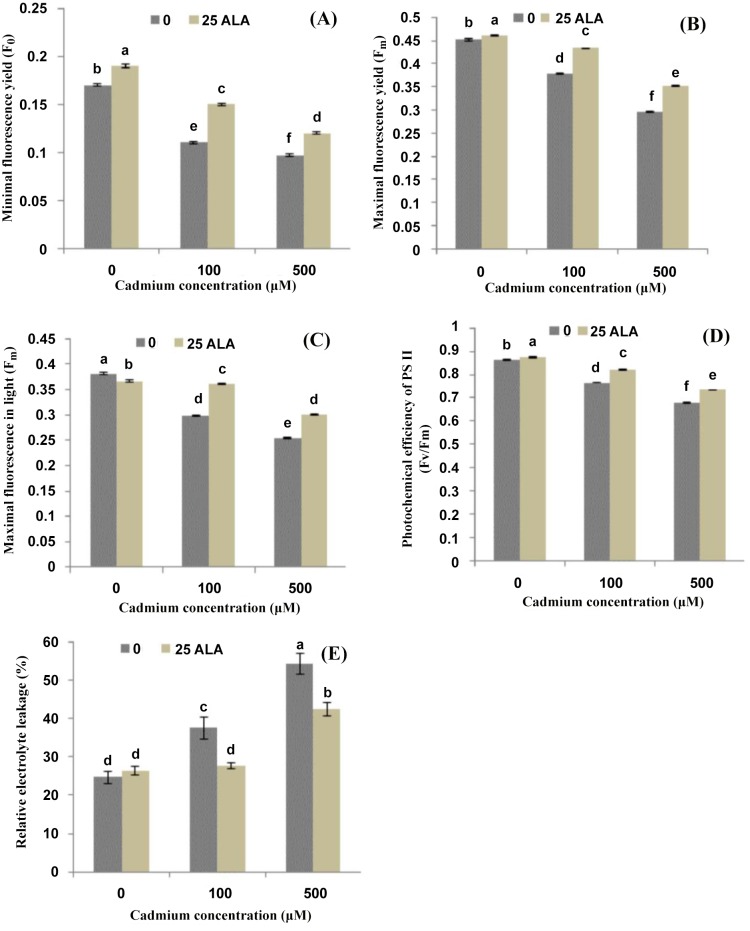

ALA up-regulates Cd-induced fluorescence parameters and down-regulates REL

Effects of different treatments of ALA and Cd2+ on chlorophyll fluorescence of photosynthetic machinery are presented in Fig 2. Results revealed that Cd2+ stress alone significantly reduced the photosynthetic quenching parameters such as F0, Fm, Fm´ and Fv/Fm as compared to control. The higher concentration of Cd2+ (500 μM) decreased F0 by (43%), Fm by (34%), Fm´ by (33%) and Fv/Fm by (22%) as compared to control. However, foliar application of ALA reduced the deleterious effects of Cd and significantly improved these parameters as compared to their respective controls. Furthermore, application of ALA alone also increased these parameters except Fm´ as compared to control plants. The present study also showed that REL increased linearly in the leaves of B. napus as we increased Cd2+ stress alone in the solution (Fig 2E). The increase in REL was (53% and 120%) under different treatments of Cd2+ (100 and 500 μM) respectively as compared to control plants. Foliar applied ALA significantly reduced the REL in B. napus under Cd2+ stress. However, ALA alone did not show any significant change on the contents of REL of B. napus as compared to control plants (Fig 2E).

Fig 2. Effects of different treatments of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) (mg/L) and cadmium (Cd2+) (μM) on photochemical quenching parameters (A) minimal fluorescence yield (F0), (B) maximal fluorescence yield (Fm), (C) maximal fluorescence in light (Fm´), (D) photochemical efficiency of PS II (Fv/Fm) and (E) relative electrolyte leakage (%) in the leaves of Brassica napus cv. ZS758.

Values are the means ± SD of three replications. Variants possessing the same letter are not statistically significant at P < 0.05.

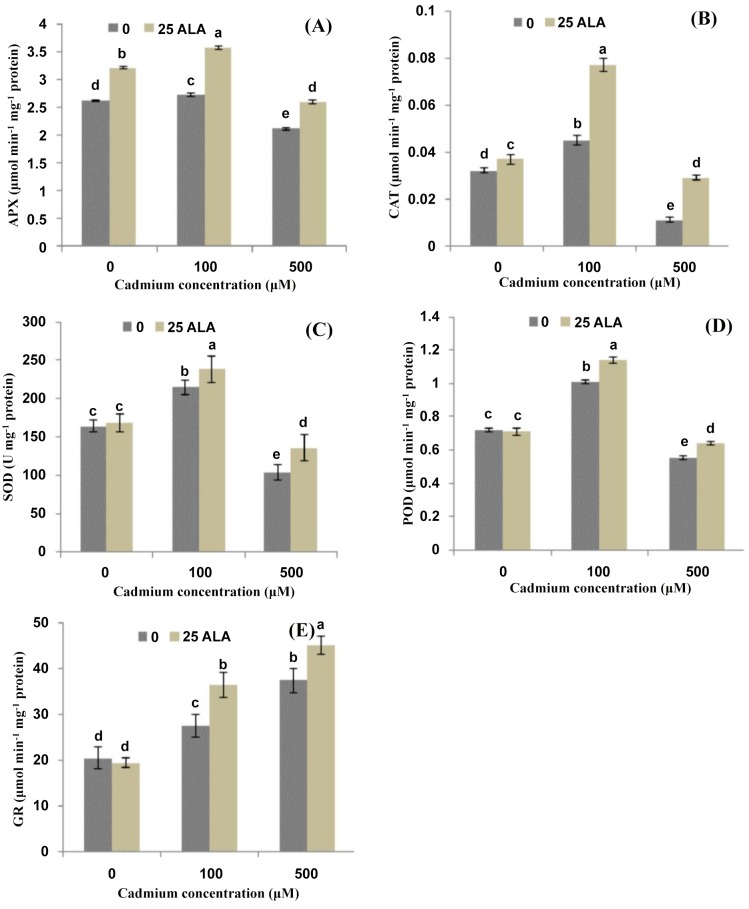

ALA alleviates Cd-induced antioxidants activities and their transcript levels

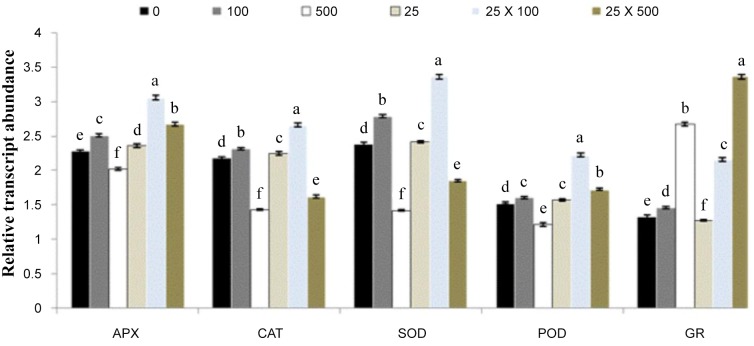

Effects of different treatments of ALA and Cd2+ on antioxidant enzyme activities in the leaves of B. napus are shown in Fig 3. Results showed that lower level of Cd2+ alone (100 μM) significantly increased the activities of APX and CAT in B. napus leaves as compared to control (Fig 3A and 3B). However, a significant decrease was found under the higher concentration of Cd2+ (500 μM). The application of ALA alleviates the Cd stress and improved APX and CAT activities significantly in B. napus leaves. Exogenous ALA increased the activity of APX by (30% and 36%) and CAT by (71% and 163%) under 100 and 500 μMCd2+ respectively, as compared to their respective controls. Results showed that lower level of Cd2+ alone showed a stimulatory effect on the activities of SOD and POD, while, higher level of Cd2+ alone showed inhibitory effect on SOD and POD activities (Fig 3C and 3D). Under Cd2+ stress conditions, ALA induced a significant increase in the activity of SOD and POD and this increase was 18% and 30% for SOD and 13% and 17% for POD under 100 and 500 μMCd2+stress respectively, as compared to their respective controls. The data depicted that activity of GR showed an increasing trend with an increase in different Cd2+ concentrations (Fig 3E). Exogenously applied ALA showed a synergetic effect on GR activity and increased the contents under different Cd2+ levels. Moreover, the present study also depicted that application of ALA alone did not show any significant change in the activities of SOD, POD and GR; however, ALA enhanced the APX and GR activities significantly as compared to control (Fig 3). To analyze the effect of ALA on gene expression in B. napus leaves under Cd stress, we examined five antioxidant enzyme genes APX, CAT, SOD, POD and GR. As shown in Fig 4, lower level of Cd2+ significantly increased the expression of APX, CAT, SOD and POD; however, higher level significantly induced these gene expressions as compared to control. The expression level of all the antioxidant enzymes was also up-regulated with the application of ALA under both Cd stress conditions (Fig 4).

Fig 3. Effects of different treatments of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) (mg/L) and cadmium (Cd2+) (μM) on the activities of (A) ascorbate peroxidase (APX), (B) catalase (CAT), (C) superoxide dismutase (SOD), (D) peroxidase (POD) and (E) glutathione reductase (GR) in the leaves of Brassica napus cv. ZS 758.

Values are the means ± SD of three replications. Variants possessing the same letter are not statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Fig 4. Effects of different treatments of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) (mg/l) and cadmium (Cd2+) (μM) on the expression of ascorbate peroxidase gene (APX), catalase gene (CAT), superoxide dismutase gene (SOD), peroxidase gene (POD) and glutathione reductase gene (GR) in the leaves of Brassica napus cv. ZS758.

The RT-qPCR analysis was performed to examine mRNA levels of five antioxidant enzyme genes in plants treated with CK, 100 μM Cd2+ alone, 500 μM Cd2+ alone, 25 mg/l ALA alone, 100 μM Cd2+ + 25 mg/l ALA and 500 μM Cd2+ + 25 mg/l ALA. Values are the means ± SD of three replications. Means followed by the same letter did not significantly differ at P<0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

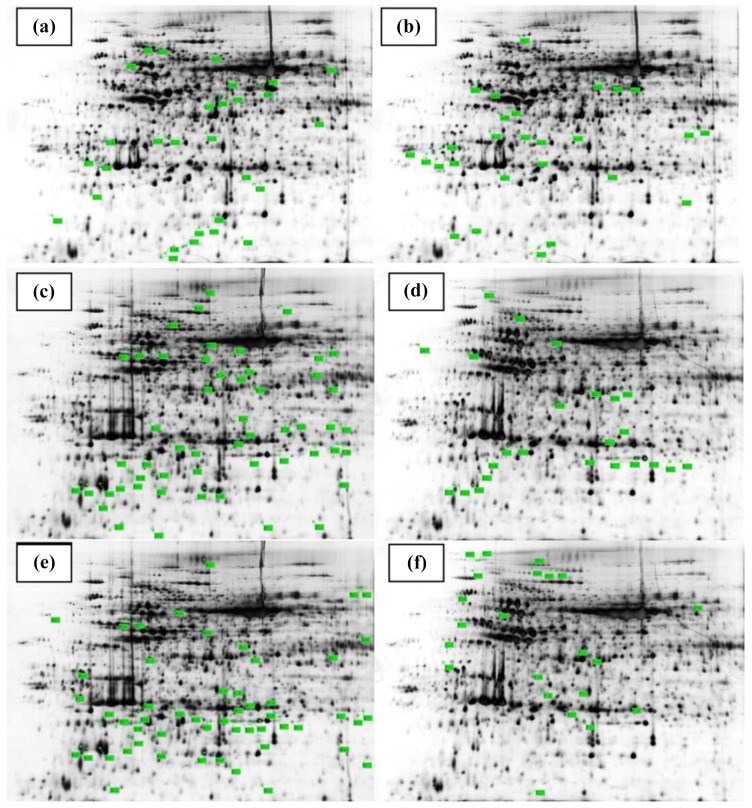

Cd-induced proteomic changes in B. napus leaves and alleviation through ALA

Classification of identified proteins spots

In order to investigate, how ALA alleviates the Cd2+-induced proteomic changes, total crude proteins were extracted for 2-D gel electrophoresis (Fig 5). Based on 1.5-fold quantitative change criteria for expression, total thirty-four protein spots showed differential expression between Cd and/or ALA-treated leaves proteomes of B. napus (S1 and S2 Figs). Eighteen spots contained down-regulated proteins (Table 1) and sixteen spots showed up-regulated proteins (Table 2). Out of thirty four differentially regulated proteins, seventeen (50%) showed no matches, while, other seventeen (50%) could be identified by proteomics analysis (S1 Fig). Out of seventeen identified reproducible protein spots, seven proteins (41%) were induced and ten proteins (59%) were up-regulated. Out of seventeen unmatched proteins, eleven proteins (64%) proteins were from down-regulated category and the rest six proteins (36%) was from up-regulated category. Moreover, data showed that out of 18 down regulated proteins, six proteins were found at Cd2+ alone conditions (S1 Fig A lettering) and seven proteins were found at the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+ as compared to Cd2+ alone conditions (S1 Fig E lettering) as well as five proteins were obtained at the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+ as compared to control (S1C Fig lettering). However, out sixteen up-regulated proteins, ten proteins were found at Cd2+ alone conditions as compared to control (S2B Fig lettering) and five proteins were found at the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+ as compared to Cd2+ alone conditions (S2F Fig lettering) as well as only one protein was observed at the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+ as compared to control (S2D Fig lettering).

Fig 5. Representative 2-DE maps comparing Brassica napus cv. ZS 758 leaf proteins isolated from normal (a, d) and under 500 μM Cd2+ alone (b, e) and under combine application of ALA and 500 μM Cd2+ (c, f) along with protein marker.

Differentially accumulated protein spots are indicated by green sashes. Twenty-nine down-regulated spots (C01-C29) and twenty-four up-regulated spots (D01-D24) under control conditions (a, d); twenty-seven down-regulated spots (A01-A27) and fifty-three up-regulated spots (B01-B53) under Cd2+ alone (b, e); fifty-three down-regulated spots (E01-E53) and twenty-two up-regulated spots (F01-F22) under the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+ (c, f) are indicated on the map.

Table 1. Down-regulated proteins in the leaves of Brassica napus cv. ZS 758 under 500 μM Cd2+ alone as compared to control (with A lettering), under the combine treatment of ALA and 500 μM Cd2+ as compared to Cd2+ alone (with E lettering) and under the combine treatment of ALA and 500 μM Cd2+ (with C lettering) as compared to control conditions.

| Spot ID | Acc. No | Homologous and specie name | Mascot score | Mol. Mass | IP Value | Peptides match | Fold decrease | Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A04 | gi|557102603 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10013710mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 50 | 44539 | 5.74 | 1 | 1.8 | |

| A05 | gi|557092637 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10004217mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 141 | 48063 | 6.52 | 10 | 2.1 | |

| A06 | gi|330254622 | ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activase (Arabidopsis thaliana) | 158 | 48754 | 7.55 | 14 | 2.5 | CO2 assimilation/photosynthesis |

| A13 | gi|557099707 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10014179mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 213 | 33483 | 5.79 | 16 | 1.9 | |

| A18 | gi|12230623 | Ribonucleoprotein At2g37220, chloroplastic; Precursor | 79 | 30699 | 5.06 | 5 | 2.0 | Protein synthesis/regulation |

| A24 | gi|75161441 | 30S ribosomal protein S6 alpha | 65 | 22975 | 5.92 | 4 | 10 | Protein synthesis/regulation |

| E05 | gi|482570957 | hypothetical protein CARUB_v10020280mg (Capsella rubella) | 113 | 50895 | 5.85 | 7 | 10 | |

| E20 | gi|75205048 | Thioredoxin-like protein, Chloroplastic drought-induced stress protein | 121 | 33948 | 8.65 | 9 | 1.9 | Stress related |

| E24 | gi|557099778 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10014474mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 108 | 27210 | 6.77 | 6 | 10 | |

| E25 | gi|557099778 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10014474mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 177 | 27210 | 6.77 | 5 | 10 | |

| E29 | gi|557115451 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10025815mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 30 | 33651 | 9.24 | 1 | 1.8 | |

| E48 | gi|557095024 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10008422mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 216 | 30292 | 8.5 | 15 | 10 | |

| E52 | gi|482572100 | hypothetical protein CARUB_v10010538mg (Capsella rubella) | 152 | 17198 | 5.24 | 6 | 10 | |

| C02 | gi|482565882 | hypothetical protein CARUB_v10013177mg (Capsella rubella) | 180 | 71578 | 5.04 | 17 | 10 | |

| C03 | gi|30316342 | 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | 230 | 60770 | 5.32 | 10 | 10 | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| C14 | gi|17380545 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-1-A | 114 | 30685 | 4.99 | 6 | 10 | Dehydration of damaged protein |

| C15 | gi|2501188 | Thiamine thiazole synthase | 266 | 36755 | 5.82 | 9 | 1.9 | Catalysis |

| C26 | gi|557107168 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10021585mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 75 | 40658 | 4.45 | 8 | 10 |

Table 2. Up-regulated proteins in the leaves of Brassica napus cv. ZS 758 under 500 μM Cd2+ alone as compared to control (with B lettering), under the combine treatment of ALA and 500 μM Cd2+ as compared to Cd2+ alone (with F lettering) and under the combine treatment of ALA and 500 μM Cd2+ (with D lettering) as compared to control conditions.

| Spot ID | Acc. No | Homologous and specie name | Mascot score | Mol. Mass | IP Value | Peptides match | Fold increase | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B11 | gi|211905345 | epithiospecifier protein (Brassica rapa subsp. pekinensis) | 245 | 37890 | 5.95 | 19 | 10 | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| B20 | gi|557094682 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10008467mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 74 | 30337 | 7.6 | 7 | 10 | |

| B21 | gi|266891 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain | 330 | 20499 | 8.23 | 8 | 1.7 | CO2 assimilation/photosynthesis |

| B24 | gi|557114672 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10027518mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 30 | 27724 | 6.86 | 1 | 2.0 | |

| B27 | gi|557102656 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10014706mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 161 | 21846 | 6.1 | 4 | 10 | |

| B28 | gi|544370614 | iron superoxide dismutase (Brassica rapa subsp. oleifera) | 67 | 23833 | 5.96 | 5 | 2.9 | Defense |

| B39 | gi|227438283 | disease resistance protein (Brassica rapa subsp. pekinensis) | 19 | 142209 | 6.48 | 1 | 4.7 | Stress related |

| B45 | gi|17369187 | Regulator of ribonuclease-like protein 1 | 164 | 18110 | 5.68 | 5 | 5.1 | Protein synthesis/ Regulation |

| B47 | gi|332646777 | peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase CYP20-3 (Arabidopsis thaliana) | 165 | 34696 | 9.24 | 7 | 5.3 | Redox homeostasis |

| B53 | gi|22001642 | Non-symbiotic hemoglobin 2 | 81 | 18364 | 5.89 | 7 | 2.3 | Transport protein |

| F09 | gi|544604537 | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase 1 | 79 | 66905 | 8.56 | 10 | 1.8 | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| F11 | gi|557104099 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10005987mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 206 | 48751 | 5.08 | 5 | 1.8 | |

| F14 | gi|557089213 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10011629mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 261 | 38323 | 5.88 | 16 | 1.7 | |

| F17 | gi|15218330 | light harvesting complex photosystem II subunit 6 (Arabidopsis thaliana) | 37 | 27505 | 6.75 | 1 | 1.8 | CO2 assimilation/photosynthesis |

| F19 | gi|75161441 | 30S ribosomal protein S6 alpha | 69 | 22975 | 5.92 | 4 | 10 | Protein synthesis/ Regulation |

| D04 | gi|557112823 | hypothetical protein EUTSA_v10025445mg (Eutrema salsugineum) | 75 | 40658 | 4.45 | 8 | 10 |

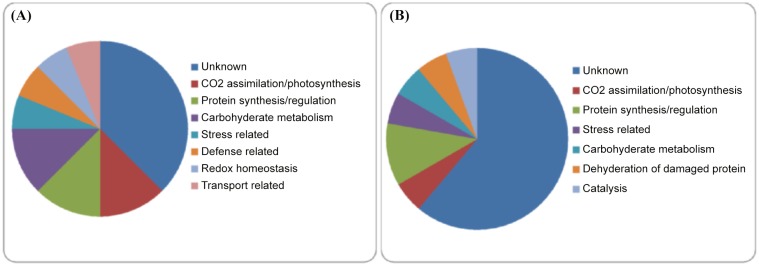

Functional distribution of identified proteins

Out of thirty four detected proteins, seventeen Cd2+ and/or ALA-responsive proteins were identified in the treated leaves. They are involved in different biological functions and pathways during the cellular adaptation to Cd2+ and/or ALA. All the identified proteins were laid under different functional classes on the basis of their putative functions (Fig 6A and 6B). These pathways and biological functions are such as CO2 assimilation/ photosynthesis, protein synthesis/ regulation, stress related, carbohydrate metabolism, dehydration of damaged proteins, catalysis, defense, redox homeostasis and transport proteins. The identified proteins belong to different functional groups. The functional groups are CO2 assimilation/ photosynthesis (18%, designated as A06, B21, F17), protein synthesis/ regulation (23% designated as A18, A24, B45, F19), stress related (11%, designated as E21, B39), carbohydrate metabolism (18%, designated as C03, B11, F07), dehydration of damaged proteins (6%, designated as C14), catalysis (6%, designated as C15), defense related proteins (6%, designated as B28), redox homeostasis (6%, designated as B47) and transport proteins (6%, designated as B53) (Table 1 and 2).

Fig 6. Differentially regulated Brassica napus proteins due to Cd2+ and/or ALA treatments.

(A) Functional distribution of the 16 up-regulated proteins that were differentially produced in response to Cd2+ and/or ALA treatments.(B) Functional distribution of the 18 down-regulated proteins that were differentially produced in response to Cd2+ and/or ALA treatments.

Identified proteins under Cd stress conditions

Regarding the Cd2+ stress alone conditions, the identified induced proteins belonged two main functional categories i.e. CO2 assimilation/ photosynthesis and protein synthesis/ regulation (Table 1). The proteins of these two categories (A06, A18, A24) were significantly down-regulated under Cd2+ alone conditions as compared to control (S1 Fig). The CO2 assimilation/ photosynthesis related protein was “ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase” (gi|330254622), which uses in the photosynthesis process in plants. However, protein synthesis/ regulation related protein were “ribonucleo protein” (gi|12230623) and “ribosomal protein” (gi|75161441) which is involved in protein synthesis.

The identified up-regulated proteins under Cd2+ alone conditions came under five main functional categories i.e. carbohydrate metabolism, CO2 assimilation/ photosynthesis, defense related, stress related and protein synthesis/ regulation (Table 2). The proteins of these five categories (B11, B21, B28, B39, B45) were significantly up-regulated under Cd2+ alone conditions as compared to control (S2 Fig). The carbohydrate metabolism and CO2 assimilation/ photosynthesis related protein were “epithiospecifier protein” (gi|211905345) and “ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase” (gi|266891) respectively, which are involved in the metabolism and assimilation of proteins. Other proteins such as “iron superoxide dismutase” (gi|544370614), “disease resistance protein” (gi|227438283) and “regulator of ribonuclease” (gi|17369187) were activated during the defense, stress and regulation of proteins, respectively.

ALA alleviates proteomic changes under Cd stress

Under the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+ tress, among the identified down-regulated proteins, identified proteins were found under four main functional categories i.e. stress related, carbohydrate metabolism, dehydration of damaged proteins and catalysis (Table 1). There was only one protein of stress related category (E20), which was significantly down-regulated under the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+ as compared to Cd2+ alone stress conditions. This protein is “thioredoxin-like protein” (gi|75205048), which uses in the plants against the stress conditions. However, carbohydrate metabolism, dehydration of damaged proteins and catalysis related protein were “2,3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase 1” (gi|30316342), proteasome (gi|17380545) and “thiamine thiazole synthase” (gi|2501188) respectively. These three proteins (C03, C14, C15) were significantly down-regulated under the combine treatment of ALA and Cd as compared to control conditions (S1 Fig).

Among the identified up-regulated proteins under the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+, identified proteins were from two main functional catagories i.e. CO2 assimilation/ photosynthesis and protein synthesis/ regulation (Table 2). The proteins of these two categories (F17, F19) were significantly up-regulated during the combine treatment of ALA and Cd as compared to Cd alone conditions (S2 Fig). These proteins were “light harvesting complex photosystem II subunit 6” (gi|15218330) and “30S ribosomal protein S6 alpha” (gi|75161441) respectively, which used in the photosynthesis and regulations of proteins in the leaves.

Discussion

ALA alleviates Cd stress and improves metabolic changes in B. napus

Cadmium (Cd) stress can also be attributed to the water stress or a kind of physiological drought generated by Cd2+ [37], as evident from the decrease in osmotic potential and relative water content (Fig 1). The decline in osmotic potential in the Cd2+ solution resulted from reduced tissue water content, and some entry of sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-) solutes with maintenance of K+ concentrations and increased production of organic solutes. ALA application induced an increase in osmotic potential and relative water contents of the stressed seedlings. Our findings are similar with those of Naeem et al. [38], who found that ALA increased osmotic potential and relative water contents under salinity stress in B. napus leaves. The accumulation of compatible solutes at high concentrations is believed to facilitate ‘‘osmotic adjustment”, can reduce inhibitory effects of ions on enzyme activity and prevent dissociation of enzyme complexes [39]. Proline, soluble sugars and free amino acids have been mentioned as important compatible solutes in osmoregulation and protect plants from stress through different mechanisms, including cellular osmotic adjustment, detoxification of reactive oxygen species, protection of membrane integrity and stabilization of proteins/ enzymes [40]. Some researchers correlate the accumulation of proline under stress as stress tolerance [41], while others consider the accumulation of proline as stress injury [42]. The present study authenticates the findings of Nayyar and Walia [41], as results show that foliar application of ALA enhanced proline accumulation in the leaves under salinity stress (Fig 1), as reported in Brassica juncea seedlings [43].

Free amino acid (FAA) accumulation in plants under Cd2+ stress has often been attributed to alterations in biosynthesis and degradation processes of amino acids and proteins [44]. In this study, FAA content increased in leaves (Fig 1) under Cd2+ stress alone or in combination with ALA. So, it can hypothesize that ALA treatment may stimulate hydrolysis of proteins, providing a pool of compatible osmolyte, which is important in osmotic adjustment [18]. This hypothesis could be supported by the observation that ALA increased FAA accumulation at the sake of proteins.

ALA alleviates Cd-induced photosynthetic fluorescence parameters

This study depicted that Cd2+ stress significantly decreased the photosynthetic fluorescence pigments (Fig 2). Previously, decrease in chlorophyll pigments under Cd2+ stress was also found in Brassica [6]. Such inhibition of biosynthesis might be the key factor for reduced photosynthesis and growth by Cd2+ [16]. Up-regulation of ROS and MDA under heavy metal stress might have caused the disturbances in the electron transport rates of PSI and PSII [45]. Another reason for such decline might be the indirect interaction of Cd2+ with photosynthesis by competing for root absorption with other metals (Mg, Fe, Mn, Zn) that are essential cofactors of enzymes, pigments and structure components of the photosynthetic apparatus [4].

It has been reported that exogenous application of ALA (a key precursor of chlorophyll) can induce the development of chloroplasts, which is reflected by the raised fluorescence pigments in the present study (Fig 2). These results are consistent with those of Wang et al. [46]; who reported that ALA may regulate the biosynthesis of chlorophyll. The effectiveness of ALA in enhancing photosynthetic efficiency can therefore be attributed to the significant improvement of fluorescence pigments and subsequently boosting light-harvesting capabilities of the treated plants [38]. Moreover, present findings suggested that Cd2+ stress displayed a negative effect on membrane integrity and thus deterioration of membranes occurred and that’s why relative electrolyte leakage enhanced under the Cd2+ toxicity (Fig 2E). The possible reason is that under heavy metal stress, plants have evolved the antioxidant enzymes mechanism that act to detoxify the changes caused by reactive oxygen species and maybe due to that this increase was occurred [47]. However, foliar applied ALA regulates the Cd2+ stress and decreased the REL in B. napus leaves. These findings are in line with those of Yusuf et al. [43] in Brassica juncea and El-Tayeb [48] in barley under NaCl stress. However, foliar application of ALA decreased the REL by improving Cd2+ tolerance; as reported by Naeem et al. [11] in B. napus.

ALA regulates Cd-induced antioxidant machinery

According to present study, APX, CAT, SOD and POD activities decreased under higher concentration of Cd2+ (500 μM); however, GR activity was increased under different Cd2+ concentrations (Fig 3). Similar to these results, such reduction in SOD activity under Cd2+ stress was reported previously in wheat [49] and in pea [50]. In the present study, the antioxidant enzymes i.e. APX, CAT, POD, and SOD enhanced their activities under the combined application of ALA and Cd2+ at different concentrations (Fig 3). This may be due to the fact that ALA is an essential precursor of heme-based molecules; its application can increase the activity of these bio-molecules (APX, POD and CAT) and helps scavenge the H2O2 to provide protection against harmful effects caused by ROS under Cd2+ stress [6]. Moreover, Liu et al. [51] and Naeem et al. [18] also observed an enhancement in antioxidant enzyme activities with the application of ALA under the water-deficit and salinity stress respectively in the leaves of B. napus.

In the present study, the expression of antioxidant genes (APX, CAT, SOD, POD and GR) was also examined (Fig 4). ALA treatment alone induced expression of antioxidant genes (POD, APX and CAT), thus increased the activities of antioxidant enzymes (POD, APX and CAT) (Fig 4). Under Cd2+ stress, expression of these activities was also up-regulated with ALA treatment. The expression patterns of these genes were totally consistent with enzyme activities. The GR activity, which can be partially reflected by GSH/GSSG ratio [52], was significantly increased upon treatment with ALA under Cd2+ stress condition in the present study. These increased activities as well as enhanced gene expression may be beneficial to ASA-GSH cycle. Similarly, Nishihara et al. [53] suggested that higher GR activity triggered by ALA in spinach led to a large pool of GSH, which could make the ASA-GSH cycle more efficient. Zhang et al. [31] found that the activity of SOD of oilseed rape leaves with ALA and herbicide ZJ0273 was significantly higher over the control. Nishihara et al. [53] also demonstrated a slightly higher SOD activity during foliar application of ALA at 0.6 and 1.8 mM to the spinach leaves than that of control. These present findings support this view; however, particular mechanisms require further investigation.

Proteomic features of B. napus leaves under application of ALA and Cd

CO2 assimilation / photosynthesis

Heavy metals can adversely affect the photosynthetic pathway [19] by depressing proteins involved in carbon fixation such as Rubisco proteins. These proteins directly control the photosynthetic mechanism of green plants. Their degradation and/or fragmentation in metal tolerant and non-tolerant plants are due to redox (e.g. copper and cadmium) and non-redox (e.g. mercury, cobalt, manganese, zinc) heavy metals [54, 55]. In the present study, we found one down-regulated (A06) and one up-regulated (B21) RuBisCO protein under Cd2+ stress alone conditions. The intensity of the up-regulated one was 1.75, while that of down-regulated one was 2.51 as compared to control (Table 1 and 2). So, the down-regulation was more, which conveyed the idea that the Calvin cycle was slowed down. The inhibition of this protein may be due to reduced photosynthetic efficiency and chlorophyll pigments of the B. napus leaves in Cd2+ stressed conditions [16]. Furthermore, Kieffer et al. [54] showed that proteins involved in carbon fixation and photosynthesis were repressed in young poplar leaves due to Cd2+ treatment. The down-regulation of RuBisCO and other photosynthesis- related enzymes have also been observed in response to metals other than Cd2+ [56]. Moreover, one up-regulated RuBisCO protein (F17) was also found with the application of ALA under Cd2+ stress (Table 2). The intensity of this up-regulated protein was 1.81 as compared to Cd2+ stress conditions. The up-regulation of RuBisCO with the application of ALA may be due to that ALA is a precursor for the biosynthesis of tetrapyrrols, and it can improve the photosynthetic efficiency of the B. napus leaves under Cd2+ stress [16]. Additionally, the alleviation of Cd2+induced of photosynthesis-related proteins by ALA supports the findings of Nwugo et al. [20], who concluded that Si could alleviate the Cd2+induced photosynthesis-related proteins in rice.

Protein synthesis and regulation

In present study, proteins were found to be involved in the synthesis and regulation of Ribonucleo protein (Table 1, spot no. A18) 30S ribosomal protein (Table 1, spot no. A24 and Table 2, spot F19) and Regulator of ribonuclease (Table 2, spot no. B45). Results showed that two proteins (spot id A18, A24) were down-regulated (A18, A24) and one protein (spot id B45) was up-regulated under Cd2+ stress (Table 1 and 2). These findings revealed the fact that ALA alleviated Cd2+induced toxicity effects on regulation/protein synthesis-related proteins. Similar to present findings, Basile et al. [57] stated that Cd2+ repressed PTPase at the transcriptional level in the liverwort. Further, Durand et al. [58] also described that Cd2+ repressed Elongation factor 1-γ and S-adenosylmethionine synthetase in poplar cambial proteome. Moreover, results also depicted that one up-regulated protein (F19) was found with the application of ALA under the Cd2+ stress (Table 2). Its intensity increased several fold over the relevant protein in Cd2+ stressed alone conditions. The fact that exogenously applied ALA alleviated the Cd2+toxicity effects on the above-mentioned protein synthesis/regulation-related proteins in B. napus plants is interesting.

Carbohydrate metabolism

In this study, we observed Cd2+ induced up-regulation of epithiospecifier protein (Table 2, spot no. B11) especially in the absence of ALA. It is well documented that epithiospecifier protein promotes the hydrolysis of glucosinolates to nitriles [54]. This protein commonly presents in plants that containing glucosinolates. Glucosinolates without terminal alkene functions may also be converted to nitriles under various conditions [59]. Kieffer et al. [54] also suggested that Cd2+ stress could limit the carbon availability by slowing down of photosynthetic carbon fixation, which can cause the plants to induce processes involved in carbohydrate catabolism [60]. However, an up-regulated protein (Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase 1, F09) of this category was found with the application of ALA under Cd2+ stress conditions (Table 2). The intensity of protein was 1.85 fold higher as compared to Cd2+ stress alone conditions. The up-regulation of this carbohydrate metabolism protein might be due to that ALA improved the photosynthetic carbon fixation process [45] and ultimately, carbon availability increased in the plant leaves.

Stress related proteins

In this experiment, two stress related proteins were found under Cd2+ and/or ALA i.e. one was down-regulated and one was up-regulated. The down-regulated protein (E20) was “thioredoxin-like protein” and found under the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+ stress (Table 1). The stress related protein was suppressed under the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+, which showed that plants did not go under stress conditions at this level [9]. However, “Thioredoxin-like protein” acts as an electron donor, which can catalyze the reduction of cysteine disulfides in proteins. Thus, in the cytoplasm, thioredoxins have a role in the catalytic cycle of redox enzymes, such as ribonucleotide reductase, and they also play role in preventing protein disulfide bridge formation in the cytoplasm [61]. Moreover, up-regulated stress related protein (B39) was found in the Cd2+ stress alone condition, which confirm the possibility that plant goes under stress at this level [22]. Further, up-regulation in stress related proteins was also observed in soybean roots under Cd2+ stress [54].

Redox homeostasis, defense and transport proteins

Proteins involved in redox homeostasis are usually involved in the prevention of oxidative stress, which is induced by reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS are byproducts of electron transport and redox reactions from metabolic processes such as photosynthesis and respiration. The production of ROS has been shown to be markedly increased under conditions of abiotic stress [62]. Cd2+ toxicity has been shown to induce the production of ROS, most likely indirectly because the redox potential of Cd2+ is too low to participate in Fenton-like redox reactions [63]. However, the effect of Cd2+ on antioxidants or proteins involved in redox homeostasis is complex and appears to be dependent on growth conditions, species, and level/duration of Cd2+ exposure. However, superoxide dismutase (SOD) acts as a primary defense against ROS by converting O2 - to O2 and H2O2, which requires a specific metal cofactor [64]. In the present study, we found one up-regulated redox homeostasis protein (B47), one up-regulated defense related protein (B28) and one up-regulated transport protein (B53) under Cd2+ stress, in the absence of ALA. These results confirmed that under Cd stress, plants gone under stress conditions and that’s why, these proteins were up-regulated to accumulate the stress [1]. However, there appeared no protein under the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+, which confirmed the findings of Nwugo et al. [9], who stated that exogenously applied Si alleviated Cd2+ induced stress in plants. Similarly, Kieffer et al. [54] also found an up-regulation in redox homeostasis related proteins in popular under Cd2+ stress.

B. napus leaf proteins regulated by ALA and Cd

Data showed only three proteins regarding this category and all were down-regulated. These proteins were “2, 3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase 1” (C03), Proteasome subunit alpha type-1-A (C14) and “Thiamine thiazole synthase” (C15) and these proteins contained different function categories such as carbohydrate metabolism, dehydration of damaged proteins and catalysis, respectively (Table 1). It is considered that protein “2, 3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase” is a metallo enzyme found particularly in archaea and some eubacteria. It is responsible for the interconversion of 2-phosphoglycerate and 3-phosphoglycerate [65]. However, proteasome contains multicatalytic proteinase complex which is characterized by its ability to cleave peptides with Arg, Phe, Tyr, Leu, and Glu adjacent to the leaving group at neutral or slightly basic pH [66]. Moreover, “thiamine thiazole synthase” catalyzes the conversion of NAD and glycine to adenosine diphosphate 5-(2-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole-2-carboxylic acid (ADT), an adenylated thiazole intermediate. The enzyme can only undergo a single turnover, which suggests it is a suicide enzyme. It may have additional roles in adaptation to various stress conditions and in DNA damage tolerance [67]. Additionally, present findings confirmed that these three proteins were down-regulated under the combine treatment of ALA and Cd2+ as compared to control. It might be suggested that there was lower stress and ultimately, less number of damaged proteins and catalytic process was found at this level.

Conclusions

The present study provides initial evidence showing that the role of ALA in plants might not be limited to that of a mechanical role but that ALA might be actively involved in the regulation of biochemical processes particularly the modulation of protein production. Generally, results from this investigation provide insights into gene expressions and post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms induced by ALA in plants under abiotic stress conditions. Further studies to determine the effect of ALA-induced stress tolerance in B. napus, the sequential influence of ALA on gene/protein expression especially during periods of stress, and possible ALA-protein interactions are currently being explored.

Supporting Information

(TIF)

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201303022), Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production (JCIC-MCP), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31170405, 31301678), and the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2012C12902-1, 2011R50026-25).

Data Availability

All the raw data is available online at Figshare at http://figshare.com/articles/Raw_Data_PONE_D_14_52527/1350903.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest (201303022), Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31170405, 31301678), and the Science and Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2012C12902-1, 2011R50026-25).

References

- 1. Zhao L, Sun YL, Cui SX, Chen M, Yang HM, Liu HM, et al. Cd-induced changes in leaf proteome of the hyper accumulator plant Phytolacca americana . Chemosphere. 2011;85: 56–66. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dai Q, Chen C, Feng B, Liu T, Tian X, Gong YY, et al. Effects of different NaCl concentration on the antioxidant enzymes in oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) seedlings. Plant Growth Regul. 2009;59: 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daud MK, Sun Y, Dawood M, Hayat Y, Variath MT, Wu YX, et al. Cadmium-induced functional and ultrastructural alterations in roots of two transgenic cotton cultivars. J Hazard Mater. 2009;161: 463–73. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.03.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. di Toppi SL, Gabbrielli R. Response to cadmium in higher plants. Environ Exp Bot. 1999;41: 105–130. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou WJ. Oilseed rape In: Zhang GP, Zhou WJ (eds) Crop production. Zhejiang University Press, Hangzhou, 2001; pp. 153–178. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ali B, Huang CR, Qi ZY, Ali S, Daud MK, Geng XX, et al. 5-aminolevulinic acid ameliorates cadmium-induced morphological, biochemical, and ultrastructural changes in seedlings of oilseed rape. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2013;20: 7256–7267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Papazoglou EG, Karantounias GA, Vemmos SN, Bouranis DL. Photosynthesis and growth responses of giant reed (Arundo donax L.) to the heavy metals Cd and Ni. Environ Int. 2005;31: 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirkham MB. Cadmium in plants on polluted soil: Effects of soil factors, hyperaccumulation, and amendments. Geoderma. 2006;137: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nwugo CC, Huerta AJ. Effects of silicon nutrition on cadmium uptake, growth and photosynthesis of rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings exposed to long-term low level cadmium. Plant Soil. 2008;311: 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lage-Pinto F, Oliveira JG, Cunha MD, Souza CMM, Rezende CE, Azevedo RA, et al. Chlorophyll a fluorescence and ultrastructural changes in chloroplast of water hyacinth as indicators of environmental stress. Environ Exp Bot. 2008;64: 307–331. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Najeeb U, Jilani G, Ali S, Sarwar M, Xu L, Zhou WJ. Insight into cadmium induced physiological and ultra-structural disorders in Juncus effusus L. and its remediation through exogenous citric acid. J Hazard Mater. 2011;186: 565–574. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kanazawa S, Sano S, Koshiba T, Ushimaru T. Changes in anti-oxidative in cucumber cotyledons during natural senescence: Comparison with those during dark-induced senescence. Physiol Plant. 2000;109: 211–216. 15092892 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin CC, Kao CH. Effect of NaCl stress on H2O2 metabolism in rice leaves. Plant Growth Regul. 2000;30: 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Asada K. Production and action of active oxygen species in photosynthetic tissues In: Foyer C, Mullineaux P (eds.) Causes of photo-oxidative stress and amelioration of defense systems in plants. Boca Raton, CRC Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang ZJ, Li HZ, Zhou WJ, Takeuchi Y, Yoneyama K. Effect of 5-aminolevulinic acid on development and salt tolerance of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) microtubers in vitro. Plant Growth Regul. 2006;49:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ali B, Wang B, Ali S, Ghani MA, Hayat MT, Yang C, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid ameliorates the growth, photosynthetic gas exchange capacity and ultrastructural changes under cadmium stress in Brassica napus L. J Plant Growth Regul. 2013;32: 604–614. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang LJ, Jiang WB, Liu H, Liu WQ, Kang L, Hou XL. Promotion by 5-aminolevulinic acid of germination of Pakchoi (Brassica camestris ssp. chinensis var. communis Tsen et Lee) seeds under salt stress. J Integr Plant Biol. 2005;47: 1084–1091. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naeem MS, Rasheed M, Liu D, Jin ZL, Ming DF, Yoneyama K, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid ameliorates salinity-induced metabolic, water-related and biochemical changes in Brassica napus L. Acta Physiol Plant. 2011;33: 517–528. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ahsan N, Renault J, Komatsu S. Recent developments in the application of proteomics to the analysis of plant responses to heavy metals. Proteomics. 2009;9: 2602–2621. 10.1002/pmic.200800935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nwugo CC, Huerta AJ. The effect of silicon on the leaf proteome of rice (Oryza sativa L.) plants under cadmium-stress. J Proteome Res. 2001;10: 518–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arnon DI, Hoagland DR. Crop production in artificial solution with special reference to factors affecting yield and absorption of inorganic nutrients. Soil Sci. 1940;50: 463–485. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ali B, Tao QJ, Zhou YF, Gill RA, Ali S, Rafiq MT, et al. 5-aminolevolinic acid mitigates the cadmium-induced changes in Brassica napus as revealed by the biochemical and ultra-structural evaluation of roots. Ecotox Environ Safe. 2013;92: 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hull HM, Morton HL, Wharrie JR. Environmental influence on cuticle development and resultant foliar penetration. Bot Rev. 1975;41: 421–451. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gucci R, Xilyannis C, Flore JA. Gas exchange parameters, water relations and carbohydrate partitioning in leaves of field grown Prunus domestica following fruit removal. Physiol Plant. 1991;83: 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yemm EW, Cocking EC. Determination of amino acids with ninhydrin. Analyst. 1955;80: 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bates LS, Waldren RP, Teare ID. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39: 205–207. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang YS, Yang ZM. Nitric oxide reduces aluminum toxicity by preventing oxidative stress in the roots of Cassia tora L. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46: 1915–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen-peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach-chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22: 867–880. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105: 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jiang M, Zhang J. Water stress-induced abscisic acid accumulation triggers the increased generation of reactive oxygen species and up-regulates the activities of antioxidant enzymes in maize leaves. J Exp Bot. 2002;53: 2401–2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang WF, Zhang F, Raziuddin R, Gong HJ, Yang ZM, Lu L, et al. Effects of 5-aminolevulinic acid on oilseed rape seedling growth under herbicide toxicity stress. J Plant Growth Regul. 2008;27: 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhou WJ, Leul M. Uniconazole-induced tolerance of rape plants to heat stress in relation to changes in hormonal levels, enzyme activities and lipid peroxidation. Plant Growth Regul. 1999;27: 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Carpentier SC, Witters E, Laukens K, Deckers P, Swennen R, Panis B. Preparation of protein extracts from recalcitrant plant tissues: an evaluation of different methods for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis analysis. Proteomics. 2005;5: 2497–2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bradford NM. Rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing principle of protein—dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bah AM, Sun H, Chen F, Zhou J, Dai H, Zhang GP, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of Typha angustifolia leaf under chromium, cadmium and lead stress. J Hazard Mater. 2010;184: 191–203. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hopkins WJ. Introduction to plant physiology. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Naeem MS, Warusawitharana H, Liu H, Liu D, Ahmad R, Waraich EA, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid alleviates the salinity-induced changes in Brassica napus as revealed by the ultrastructural study of chloroplast. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2012;57: 84–92. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Delauney AJ, Verma DPS. Proline biosynthesis and osmoregulation in plants. Plant J. 1993;4: 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ashraf M, Foolad MR. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;59: 206–216. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nayyar H, Walia DP. Water stress induced proline accumulation in contrasting wheat genotypes as affected by calcium and abscisic acid. Biol Plant. 2003;46: 275–279. [Google Scholar]

- 42. de Lacerda CF, Cambraia J, Oliva MA, Ruiz HA, Prisco JT. Solute accumulation and distribution during shoot and leaf development in two sorghum genotypes under salt stress. Environ Exp Bot. 2003;49: 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yusuf M, Hasan SA, Ali B, Hayat S, Fariduddin Q, Ahmad A. Effect of salicylic acid on salinity induced changes in Brassica juncea L. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50: 1096–1102. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Roy-Macauley H, Zuily-Fodil Y, Kidric M, Thi ATP, Da Silva JV. Effect of drought stress on proteolytic activities in Phaseolus and Vigna leaves from sensitive and resistant plants. Physiol Plant. 1992;85: 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ali B, Xu X, Gill RA, Yang S, Ali S, Tahir M, et al. Promotive role of 5-aminolevulinic acid on mineral nutrients and antioxidative defense system under lead toxicity in Brassica napus . Ind Crops Pro. 2014;52: 617–626. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang LJ, Jiang WB, Huang BJ. Promotion of 5-aminolevulinic acid on photosynthesis of melon (Cucumis melo) seedlings under low light and chilling stress conditions. Physiol Plant. 2004;121: 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Inostroza-Blancheteau IM, Reyes-Díaz F, Aquea A, Nunes-Nesi M, Alberdi M, Arce-Johnson P. Biochemical and molecular changes in response to aluminum stress in high bush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2011;49: 1005–1012. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. El-Tayeb MA. Response of barley grains to the interactive effect of salinity and salicylic acid. Plant Growth Regul. 2005;45: 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Milone MT, Sgherri C, Clijsters H, Navarri-Izzo F. Antioxidant responses of wheat treated with realistic concentration of cadmium. Environ Exp Bot. 2003;50: 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Romero-Puertas MC, Corpas FJ, Rodriguez-Serrano M, Gomez M, del Rio LA, Sandalio LM. Differential expression and regulation of antioxidative enzymes by cadmium in pea plants. J Plant Physiol. 2007;164: 1346–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu D, Pei ZF, Naeem MS, Ming DF, Liu HB, Khan F, et al. 5-aminolevulinic acid activates anti-oxidative defence system and seedling growth in Brassica napus L. under water-deficit stress. J Agron Crop Sci. 2011;197: 284–295. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Foyer CH, Halliwell B. The presence of glutathione and glutathione reductase in chloroplasts: proposed role in ascorbic-acid metabolism. Planta. 1976;133: 21–25. 10.1007/BF00386001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nishihara E, Kondo K, Parvez M, Takahashi K, Watanabe K, Tanaka K. Role of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) on active oxygen-scavenging system in NaCl-treated spinach (Spinacia oleracea). J Plant Physiol. 2003;160: 1085–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kieffer P, Dommes J, Hoffmann L, Hausman JF, Renaut J. Quantitative changes in protein expression of cadmium-exposed poplar plants. Proteomics. 2008;8: 2514–2530. 10.1002/pmic.200701110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rafiq MT, Aziz R, Yang X, Xiao W, Stoffella PJ, Saghir A, et al. Phytoavailability of cadmium (Cd) to Pak choi (Brassica chinensis L.) grown in Chinese soils: A model to evaluate the impact of soil Cd pollution on potential dietary toxicity. PLOS ONE. 2014;11: 111461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van Keulen H, Wei R, Cutright TJ. Arsenate-induced expression of a class III Chitinase in the dwarf sunflower Helianthus annuus . Environ Exp Bot. 2008;63: 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Basile A, Alba di Nuzzo R, Capasso C, Sorbo S, Capasso A, Carginalea V. Effect of cadmium on gene expression in the liverwort Lunularia cruciata . Gene. 2005;356: 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Durand TC, Sergeant K, Planchon S, Carpin S, Label P, Morabito D, et al. Acute metal stress in Populus tremula P. alba (717-1B4 genotype): Leaf and cambial proteome changes induced by cadmium. Proteomics. 2010;10: 349–368. 10.1002/pmic.200900484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Latxague L, Gardrat C. Identification of enzymatic degradation products from synthesized glucobrassicin by gas chromatography—mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 1991;586: 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lopez-Millan A, Sagardoy R, Solanas M, Abadia A, Abadia J. Cadmium toxicity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants grown in hydroponics. Environ Exp Bot. 2009;65: 376–385. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ritz D, Beckwith J. Roles of thiol-redox pathways in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55: 21–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mittler R, Vanderauwera S, Gollery M, Van Breusegem F. Reactive oxygen gene network of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9: 490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Clemens S. Toxic metal accumulation, responses to exposure and mechanisms of tolerance in plants. Biochimie. 2006;88: 1707–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bowler C, van Montagu M, Inze D. Superoxide dismutase and stress tolerance. Ann Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43: 83–116. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Johnsen U, Schönheit P. Characterization of cofactor-dependent and cofactor-independent phosphoglycerate mutases from Archaea. Extremophiles. 2007;11(5): 647–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sung DY, Kim TH, Komives EA, Mendoza-Cozatl DG, Schroeder JI.ARS5 is a component of the 26S proteasome complex, and negatively regulates thiol biosynthesis and arsenic tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;59: 802–812. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03914.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Machado CR, de Oliveira RL, Boiteux S, Praekelt UM, Meacock PA, Menck CF.Thi1, a thiamine biosynthetic gene in Arabidopsis thaliana, complements bacterial defects in DNA repair. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31: 585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All the raw data is available online at Figshare at http://figshare.com/articles/Raw_Data_PONE_D_14_52527/1350903.