Abstract

Background

Infectious diarrhea is a common problem among travelers. Expert guidelines recommend the prompt use of antibiotics for self-treatment of moderate or severe traveler’s diarrhea (TD). There is limited data on whether travelers follow these self-treatment guidelines. We evaluated the risk factors associated with TD, use of TD self-treatment, and risk of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) during travel.

Methods

Department of Defense beneficiaries traveling outside the US for ≤ 6.5 months were enrolled in a prospective cohort study. Participants received pre- and post-travel surveys, and could opt into a travel illness diary and follow-up surveys for symptoms of IBS. Standard definitions were used to assess for TD and IBS. Sub-optimal self-treatment was defined as use of antibiotics (with or without antidiarrheal agents) for mild TD, or use of antidiarrheals alone or no self-treatment in cases of moderate or severe TD.

Results

Twenty-four percent of participants (270/1120) met criteria for TD. The highest incidence was recorded in Africa (8.6 cases/100 person-weeks, 95% CI: 6.7–10.5). Two hundred and twelve TD cases provided information regarding severity and self-treatment: 89 (42%) had mild TD and 123 (58%) had moderate or severe TD. Moderate or severe TD was independently associated with suboptimal self-treatment (OR 10.4 [95% CI: 4.92–22.0]). Time to last unformed stool did not differ between optimal and suboptimal self-treatment. IBS occurred in 4.5% (7/154) of TD cases and 3.1% (16/516) of patients without TD (p=0.39). Among TD cases, a lower incidence of IBS was noted in participants who took antibiotics (4.8% (5/105) vs. 2.2% (1/46)), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.60).

Conclusions

Our results suggest the underutilization of antibiotics in travelers with moderate or severe TD. Further studies are needed to systematically evaluate pre-travel instruction and traveler adherence to self-treatment guidelines, and the impact of suboptimal self-treatment on outcomes.

Traveler’s diarrhea (TD) is a frequent cause of incapacitation in travelers and deployed military personnel, resulting in disruption of planned activities and impacting mission readiness. Randomized trials have established the efficacy of combination therapy with antibiotics and loperamide in limiting the duration of TD symptoms.1–3 Expert guidelines recommend rehydration with or without loperamide for self-treatment of mild watery diarrhea that does not interfere with daily activities, and a combination of antibiotics (e.g. quinolones, azithromycin or rifaximin) and loperamide for moderate or severe symptoms.4–6 However, there is limited prospective data on how travelers use these medications for self-treatment, and their effectiveness in shortening the duration of symptoms and preventing long-term sequelae.7, 8

The TravMil study (Deployment and Travel Related Infectious Disease Risk Assessment, Outcomes, and Prevention Strategies Among Department of Defense Beneficiaries) prospectively evaluates infectious disease risks, and the effectiveness of prevention and treatment strategies, in Department of Defense (DoD) beneficiaries traveling outside the continental United States.9 We utilized data from the TravMil cohort to assess i) the incidence and risk factors for TD; ii) the risk factors for suboptimal self-treatment and impact on outcomes and iii) the risk of irritable bowel syndrome following TD.

METHODS

Study Design

TravMil is a prospective, observational cohort of DoD beneficiaries traveling outside the continental United States for ≤ 6.5 months. Adult and pediatric travelers enrolled pre-travel from three military travel clinics (Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, VA; Naval Medical Center San Diego, CA and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD) between January 2010 and July 2013 were included. Itineraries limited to Western or Northern Europe, Canada, or New Zealand were excluded. Travel medicine physicians counseled travelers on prevention and self-treatment of diarrhea, and provided relevant prescriptions. No standardization of counseling for TD self-treatment was performed as part of this study. The study was approved by the Uniformed Services University Infectious Disease Institutional Review Board.

Participant demographics, travel itinerary, medical history, and prescriptions were obtained during the pre-travel visit. Participants received two surveys. A pre-travel survey evaluated demographic data, previous travel to developing countries and symptoms of IBS. A post-travel survey, completed up to 8 weeks after return, collected information regarding dietary habits during travel, diarrheal episodes, associated symptoms, perceived severity and incapacitation, and use of self-treatment.

Participants were invited to opt into the following procedures at the pre-travel visit:

-

-

Travel illness diary: daily record of the number of unformed stools per 6 hour period during a diarrheal episode along with associated symptoms, severity, level of incapacitation, timing of self-treatment and associated side effects.

-

-

Follow up survey: sent at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months post-travel to evaluate for symptoms of IBS.

Definitions

Travel destinations were divided into five regions, modified from the GeoSentinel model10: a) Southeast Asia, North Asia and Oceania; b) South, Central, and West Asia; c) South America, Central America, Caribbean; d) Africa; and e) Eastern Europe. Travel to > 1 region was classified as ‘multiple destinations,’ except where travel was limited to Eastern Europe and one other destination. In this instance, participants were classified as traveling to the destination other than Eastern Europe, since the incidence of TD is higher elsewhere. For the multivariate analyses regarding TD risk factors and sub-optimal treatment, we dichotomized travel regions into ‘Africa’ and ‘regions other that Africa’ (since travel to Africa was associated with the highest TD attack rates).

Trip purpose was categorized as follows: visiting friends and relatives (VFR), vacation, business, military travel, and other (teaching/study, providing medical support, missionary/humanitarian work, adventure travel/ecotour, adoption and other). For the multivariate analyses, we combined VFR and vacation travel into a single ‘vacation’ category (due to the small number of VFR travelers in our cohort and no significant difference in the rate or severity of diarrhea) and combined all other trip purposes into a single ‘non-vacation’ category.

TD was defined as ≥ 3 unformed stools, or 2 unformed stools with at least one accompanying symptom (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, blood in stool) within 24 hours. Participants with unformed stool that did not meet criteria were classified as having loose stools. Participants with TD were categorized into the following hierarchy: a) mild TD, defined as acute watery diarrhea (AWD) (i.e. diarrhea without fever or blood in stool) with mild severity (i.e. allowing for normal level of activity) and b) moderate or severe TD, defined as AWD with moderate or severe symptoms (i.e. decreased level or complete inability to participate in daily activities), dysentery (visible blood in stool) or acute febrile watery diarrhea (AFWD) (diarrhea associated with subjective fever). Multiple episodes of TD were defined as having a diarrhea-free interval of ≥ 72 hours.

We evaluated optimal use of self-treatment in participants with TD. Suboptimal self-treatment was defined as the use of antibiotics for mild TD, or use of an antidiarrheal agent alone or no self-treatment for moderate or severe TD. Conversely, no self-treatment or use of antidiarrheals alone was considered optimal self-treatment for mild TD, as was the use of antibiotics alone or in combination with antidiarrheals for moderate or severe TD.

Participants with TD who completed a travel illness diary were included in the effectiveness analysis. The primary measure was time to last unformed stool (TLUS), defined as the time from treatment initiation to passage of the last unformed stool. Clinical cure was defined as passage of no unformed stools and resolution of all associated symptoms after initiation of self-treatment. The modified Rome III criteria were used to classify participants with IBS in the pre-travel and follow-up surveys.11 Participants with IBS pre-travel, and those who did not complete any follow-up surveys, were excluded from the IBS analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). TD Incidence rates were calculated as the number of cases/100 person-weeks of travel. The median time to first episode of TD between geographic regions was compared using hazard ratios computed by a univariate Cox proportional hazards model. A multivariable logistic regression model with backward selection was used to determine risk factors for TD and suboptimal self-treatment. A Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and the Fishers exact test for categorical variables were used to compare median TLUS, clinical cure rates and risk factors for IBS. TLUS was compared between optimal vs. suboptimal self-treatment by a Kaplan-Meier analysis with a log-rank test. A left-truncation was performed on the cohort that received no self-treatment using the median time from start of symptoms to treatment in participants in the self-treatment cohort. Participants could be included in the analysis multiple times if they took multiple trips, but only the first episode of diarrhea that met criteria for TD per trip was used in the treatment analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 1215 patients were enrolled in the study - 79 patients enrolled for multiple trips, for a total of 1323 enrollments. Of these, 1120 (85%) completed a post-travel survey and/or a travel illness diary (Supporting Information online only). The median trip duration was 17 days (IQR: 12–29 days) and the median duration between trip return and completion of the post-travel survey was 21 days (IQR: 10–34 days). Seven hundred and eighty four (70%) participants had no diarrhea during travel, 66 (6%) experienced loose stool, and 270 (24%) developed TD (incidence rate of 5.3 cases/100 person-weeks [95% CI: 4.7–6.0 cases/100 person-weeks]). TD was associated with a maximum (median) of 4 (IQR: 2–4) stools per day and lasted for a median of 1 day (IQR: 1–2 days). There were 208 cases of AWD, 52 cases of AFWD and 10 cases of dysentery. Cases with mild TD reported a maximum (median) of 3 stools per day (IQR: 2–4) lasting for 1 day (IQR: 1–2), while moderate or severe TD was associated with 4 stools per day (IQR: 3–6) for 2 days (IQR: 1–3).

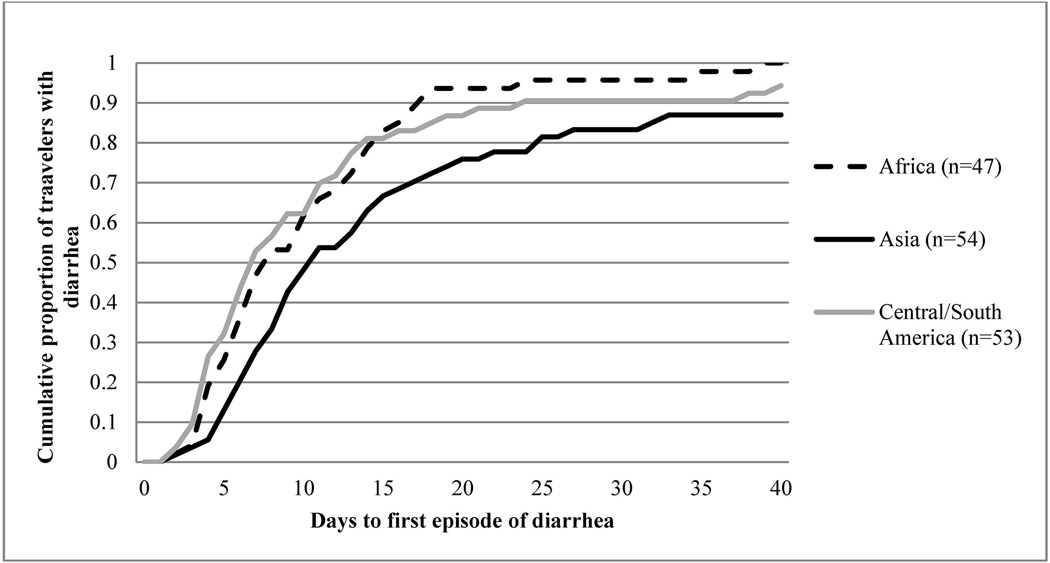

The highest incidence rates for TD were recorded in Africa (8.6 cases/100 person-weeks, 95% CI: 6.7–10.5) and South, Central, and West Asia (6.1 cases/100 person-weeks, 95% CI: 3.4–8.7). Information regarding timing of symptoms was obtained from 164 participants with TD and the median time from start of travel to development of TD was 9 days (IQR: 6–16 days). Figure 1 represents the time to first TD episode, and the TD hazard ratio at 9 days for the highest risk regions. A longer median interval to symptom onset was observed for Asia (11 days [IQR: 7–20]; n=54) as compared to Africa (8 days [IQR: 5–14]; n=47; Africa vs Asia p=0.02) and Central and South America (7 days; [IQR: 4–13]; n=53; Central and South America vs. Asia p=0.01). Participants who traveled to Asia were more likely to be vacationing or visiting friends and relatives (VFR) and consume meals prepared by street vendors as compared to Africa and the Americas (p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Time from trip start date to first episode of traveler’s diarrhea (TD) stratified by travel destinationa

a In participants who met criteria for TD, completed a travel diary and traveled to regions with high risk for TD (n=154).

Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards model used to calculate hazard ratio for TD within 9 days of travel (9 days was the median time to development of TD for the overall cohort); log-rank p-value=0.0541. Hazard Ratio for TD within 9 days of travel (95% CI): Asia: Reference; South/Central America: 1.85 (1.09–3.16) p=0.03; Africa: 1.46 (0.83–2.58) p=0.19

Risk factors independently associated with TD were female gender (Risk Ratio: 1.33(1.03–1.71)) and travel to Africa either for vacation/VFR (Risk Ratio: 1.88 (1.26–2.80)) or for business (Risk Ratio: 1.73(1.18–2.57)). Dietary indiscretion (consumption of poorly cooked meat, unsecured water, use of ice in beverages and eating meals prepared by street vendors) during travel was not associated with TD (Table 1). We performed a separate univariate analysis of incidence of TD within the first 14 days of travel among short term (i.e. ≤ 2 weeks) vs. long term (> 2 weeks) travelers, for patients who provided information regarding timing of diarrheal episodes. Short term travelers were significantly more likely to develop TD in the first two weeks compared to longer term travelers (Risk Ratio: 2.97(2.15–4.09).

Table 1.

Risk factors for travelers’ diarrhea (TD) (n=1120) a

| Variable | Number of participants who met criteria for TD |

Person -time (days) |

Rate(Cases/100 person-weeks) |

Univariate Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

Multivariate Rate Ratio (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| > 55 years | 104 | 12210 | 5.96 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| 26–55 years | 116 | 15668 | 5.18 | 0.87(0.67–1.13) | 1.11(0.81–1.52) | |

| ≤ 25 years | 50 | 7723 | 4.53 | 0.76(0.54–1.07) | 1.01(0.67–1.51) | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 120 | 18643 | 4.51 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Female | 150 | 16958 | 6.19 | 1.37(1.08–1.75) | 1.32(1.03–1.71) | |

| Trip purpose and destination | ||||||

| Non-vacation excluding Africa | 96 | 17924 | 3.75 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Vacation excluding Africa | 96 | 11268 | 5.96 | 1.59(1.20–2.11) | 1.36(0.98–1.89) | |

| Africa for non-vacation travel | 37 | 2973 | 8.71 | 2.32(1.59–3.40) | 1.74(1.18–2.57) | |

| Africa for vacation travel | 41 | 3362 | 8.54 | 2.28(1.58–3.28) | 1.88(1.26–2.80) | |

| Meals prepared by street vendors b | ||||||

| No | 186 | 24412 | 5.33 | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 70 | 9147 | 5.36 | 1.00(0.76–1.32) | ||

| Consumption of poorly cooked meat(pork, beef or seafood) b | ||||||

| No | 200 | 26580 | 5.27 | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 32 | 4786 | 4.68 | 0.89(0.61–1.29) | ||

| Consumption of unsecured water b | ||||||

| No | 200 | 26092 | 5.30 | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 56 | 6924 | 5.47 | 1.03(0.77–1.39) | ||

| Ice in beverages b | ||||||

| No | 104 | 10968 | 6.64 | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 145 | 21332 | 4.76 | 0.72(0.56–0.92) | ||

| History of H2 blockers/PPI use | ||||||

| No | 222 | 29672 | 5.24 | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 48 | 5885 | 5.71 | 1.09(0.80–1.49) | ||

TD defined as report of ≥ 3 loose stools in a 24 hour period or two unformed stools with at least one accompanying symptom (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, blood in stool)

Subjects with missing information: meals prepared by street vendors=14 subjects; consumption of poorly cooked meat=38 subjects; consumption of unsecured water=14 subjects; ice in beverages=21 subjects

Two hundred and twelve TD cases (79%) were included in the analysis for suboptimal self-treatment (Supporting Information online only). A moderate or severe diarrheal illness was the only independently predictor for suboptimal self-treatment (OR: 10.4 (95% CI: 4.92–22.0) (Table 2). Eighty-eight percent (77/88) of mild TD cases took optimal self-treatment. However, only 42% of moderate or severe TD cases took optimal self-treatment (moderate or severe AWD: 30/81(37%), AFWD 17/35 (49%), dysentery 4/8 (50%)). The most frequently used antibiotic was ciprofloxacin (68%), followed by azithromycin (32%), with 5% reported taking both.

Table 2.

| Variable | Optimal self- treatment (n=129) |

Suboptimal self-treatment (n=83) |

Univariate Odds Ratio – suboptimal self-treatment (95% CI) |

Multivariate Odds Ratio – suboptimal self-treatment (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| > 55 years | 48(38) | 30(36) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| 26–55 years | 55(43) | 38(46) | 1.10(0.60–2.05) | 1.07(0.53–2.17) | |

| ≤ 25 years | 25(19) | 15(18) | 1.02(0.46–2.25) | 1.36(0.54–3.43) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 61(47) | 33(40 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Female | 68(53) | 50(60) | 1.36(0.78–2.38) | 1.11 (0.57–2.15) | |

| Severity of diarrhea | |||||

| Mild | 78(60) | 11(13) | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Moderate or Severe | 51(40) | 72(87) | 10.0(4.84–20.7) | 10.4(4.95–22.0) | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 102(79) | 68(82) | Ref. | ||

| Non-white | 27(21) | 15(18) | 0.83 (0.41–1.68) | ||

| Trip duration | |||||

| ≤ 2 weeks | 40(31) | 31(37) | 1.32(0.74–2.37) | ||

| > 2 weeks | 89(69) | 52(63) | Ref. | ||

| Trip purpose | |||||

| Non-vacation/VFR | 46(36) | 23(28) | Ref. | ||

| Vacation or VFR | 83(64) | 60(72) | 1.44(0.79–2.64) | ||

| Region of travel | |||||

| Travel to Africa | 88(68) | 67(81) | Ref. | ||

| Travel to regions other than Africa | 41(32) | 16(19) | 0.51(0.27–0.99) | ||

| High risk behavior for TD c | |||||

| No | 30(25) | 18(22) | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 89(75) | 62(78) | 1.16(0.60–2.27) | ||

TD defined as report of ≥ 3 loose stools in a 24 hour period or two unformed stools with at least one accompanying symptoms(nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, blood in stool). 212 TD cases provided information regarding severity of diarrhea and use of self-treatment and were included in the analysis

Suboptimal self-treatment is defined as use of antibiotic therapy for mild acute watery diarrhea or use of antidiarrheal medication alone or no treatment for moderate or severe acute watery diarrhea, dysentery and acute febrile watery diarrhea. Conversely, no self-treatment or use of antidiarrheals alone was considered optimal self-treatment for mild TD, as was the use of antibiotics alone or in combination with antidiarrheals for moderate or severe TD.

Defined as consumption of meals prepared by street vendors, poorly cooked meat, unsecured water or use of ice in beverages during travel. Risk behavior was unknown for 13 participants

One hundred and twenty four TD cases (46%) were included in the effectiveness analysis (Supporting Information online only). TLUS and 48 hour cure rate was compared between suboptimal and optimal self-treatment, stratified by severity of diarrhea. No significant difference in the TLUS (log rank p-value > 0.05) or 48-hour cure rates was observed (mild TD: suboptimal treatment: 100% (7/7); optimal self-treatment: 85% (28/33); p=0.36); moderate-severe TD: suboptimal treatment: 77% (36/47); optimal self-treatment: 73% (27/37); p=0.70) (Table 3). The poor compliance with the travel diary and lack of antibiotic use for moderate or severe diarrhea, significantly limited the sample size for analysis.

Table 3.

Outcomes associated with travelers’ diarrhea (TD) self-treatment a

| Mild diarrhea (n=40) | |||

| Outcome Characteristics |

Optimal self-treatment (no treatment or antidiarrheals) (n=33) |

Sub-optimal self-treatment (antibiotics +/− antidiarrheals) (n=7) |

p-value |

| TLUS, median h(IQR) c | 8.5 (3.5–25.0) | 14.0 (7.3–27.3) | 0.22 |

| Clinical cure at 24 h, n(%) | 23(70) | 4(57) | 0.66 |

| Clinical cure at 48 h, n(%) | 28(85) | 7(100) | 0.36 |

| Post treatment side effects | |||

| Nausea, n(%) | 0(0) d | 1(14) | 0.35 |

| Vomiting, n(%) | 1(8) d | 0(0) | 1.0 |

| Moderate or severe diarrhea (n=84) | |||

| Outcome |

Optimal self-treatment (antibiotics +/− antidiarrheals) (n=37) |

Sub-optimal self-treatment (no treatment or antidiarrheals) (n=47) |

p-value |

| TLUS, median h(IQR) c | 7(2–62) | 8.5(2.5–38.5) | 0.97 |

| Clinical cure at 24 h, n(%) | 24(65) | 30(64) | 0.92 |

| Clinical cure at 48 h, n(%) | 27(73) | 36(77) | 0.70 |

| Post treatment side effects | |||

| Nausea, n(%) | 11(30) d | 0(0) d | 0.005 |

| Vomiting, n(%) | 5(14) d | 0(0) d | 0.15 |

Participants who met criteria for TD and completed a diary noting the timing of diarrheal episodes and use of self-treatment (n=124)

p-value reflects the comparison between the three treatment types only

Median time to therapy start for treatment group was 3.5 hours. For patients who took no self-treatment (n=47 [20 mild diarrhea, 27 moderate or severe diarrhea]) TLUS was calculated as the mean number of unformed stools by 3.5 hours after episode start. Six subjects had resolved symptoms before this time.

reported only for patients who took antidiarrheals

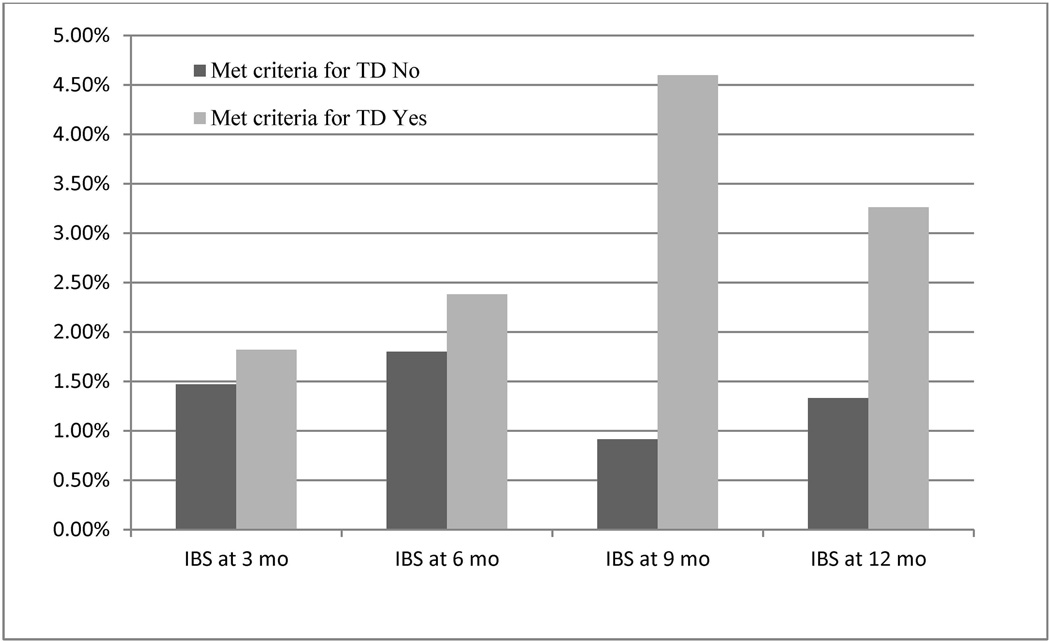

The overall incidence of IBS was 3.4% (23/670). Of the 23, eight (35%) developed new IBS symptoms within 3 months after their return date, seven (30%) first developed symptoms 6 months after returning, three (13%) first developed symptoms 9 months after returning, and five (22%) first developed symptoms on the last survey 12 months after returning. Thirty percent (7/23) displayed symptoms over multiple time points. Participants with TD had a numerically higher incidence of IBS vs. those without TD (4.5% vs. 3.1%; p=0.39) (Figure 2 and Table 4). Among 154 cases TD, 5 of 105 (4.8%) who received no treatment or antidiarrheal alone developed post-travel IBS vs. 1 of the 46 cases (2.2%) who took antibiotic alone or in combination with an antidiarrheal (p=0.67).

Figure 2.

Frequency of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) among travelers’ diarrhea (TD) cases and those without TD.

a Total number of participants who met criteria or did not meet criteria for traveler’s diarrhea and completed an extended follow up survey at the specified time point. Participants counted at multiple time points.

b Number of participants who did not fill out an extended f/up survey at the specified time-point

Table 4.

Comparison of travelers who developed irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) post-travel and those who did not a

| Variable | No IBS reported post- travel (n=647) |

IBS reported post- travel (n=23) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| > 55 years | 326(50) | 15(65) | ||

| 26–55 years | 252(39) | 8(35) | 0.41 | |

| ≤ 25 years | 69(11) | 0(0) | 0.96 | |

| Male gender | 322(97) | 9(3) | 0.32 | |

| Active duty (Enlisted or Officer) | 118(18) | 4(17) | 0.92 | |

| Trip duration | ||||

| ≥ 2 weeks | 400(62) | 9(39) | ||

| < 2 weeks | 247(38) | 14(61) | 0.03 | |

| Trip purpose | ||||

| Non-Vacation or VFR | 170(26) | 7(30) | ||

| Vacation/VFR | 474(74) | 16(70) | 0.67 | |

| Region of travel | ||||

| Southeast Asia, North Asia and Oceania | 155(24) | 5(22) | ||

| South Asia, Central Asia, West Asia | 51(8) | 5(22) | 0.09 | |

| South America, Central America, Caribbean | 193(30) | 6(26) | 0.95 | |

| Africa | 185(28) | 3(13) | 0.35 | |

| Eastern Europe | 16(2) | 1(4) | 0.56 | |

| Multiple destinations | 47(7) | 3(13) | 0.36 | |

| Traveler’s diarrhea (TD) | ||||

| No diarrhea | 500(77) | 16(70) | ||

| Mild TD | 69(11) | 1(4) | 0.45 | |

| Moderate or severe TD | 78(12) | 6(26) | 0.08 | |

| Duration of TD | ||||

| No TD | 500(77) | 16(70) | ||

| ≤ 1 day | 65(10) | 1(4) | 0.48 | |

| > 1 day | 82(13) | 6(26) | 0.09 | |

| Multiple episodes of TD c | 19(20) | 2(40) | 0.28 | |

| TD self-treatment b | ||||

| No Treatment/Antidiarrheal only | 100(69) | 5(83) | ||

| Antibiotic | 45(31) | 1(17) | 0.67 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 1 | ||

Only participants who did not report symptoms of IBS pre-travel and completed at least 1 extended follow-up surveys at 3, 6, 9 or 12 months post-travel were included in the analysis.

Participants who completed a diary or post-travel survey and met criteria for TD

Participants who completed a diary and had multiple episodes that met criteria for TD

DISCUSSION

We utilized a large, prospective cohort of DoD beneficiaries traveling to intermediate and high-risk TD regions to describe the incidence and characteristics of TD, the use and effectiveness of self-treatment, and the incidence of IBS. Approximately one-quarter of participants developed TD, with a regional attack rate between 22–26% for all regions of travel except Eastern Europe. Our incidence rate was substantially lower than historic rates of > 50% reported for high risk destinations,12–14 and slightly lower than the 28–34% attack rates reported in recent observational cohorts.7, 8, 15–17 This may be attributable to the pooling of intermediate and high risk destinations, and could also indicate a general trend towards better food hygiene in parts of the developing world frequented by travelers.

Several interesting associations with TD incidence were observed. Travelers with trip durations of ≤ 2 weeks had a TD incidence rate in the first two weeks of travel three times greater than longer term travelers, possibly due to altered dietary behaviors (e.g. cooking at home) in long-term travelers that allowed them to remain well. A slightly longer median interval to TD onset was noted in travelers to Asia (11 days vs. 8 days for Africa and 7 days for the Americas), possibly reflecting the longer incubation periods of pathogens such as Campylobacter spp. and Salmonella spp. found more frequently in Asia. Despite receiving pre-travel advice on avoidance measures, only 14% were fully compliant with dietary precautions and no association between dietary indiscretion and TD was observed, highlighting the limitations of education on avoidance behaviors in mitigating the risk of TD.7, 18, 19

TD cases were relatively mild, lasting a median of 8.5 hours, with a maximum (median) of 3–5 stools/day, but had a significant impact on travel plans: 52% reported partial or complete incapacitation for a day, 23% had febrile diarrhea or dysentery, and 10% sought medical care or hospitalization. This disruption in daily activities maybe especially important in business travelers or deploying personnel, where the tolerance for any short-term illnesses is low. It is these subsets of short-term travelers that may be good candidates for chemo- or immunoprophylaxis.

Expert guidelines and efficacy trials support prompt treatment with antibiotics and loperamide for moderate-severe TD.1–6 We observed that moderate or severe TD cases were ten times more likely to use suboptimal self-treatment compared to participants with mild diarrhea. Only 32% of participants with moderate-severe diarrhea took an antibiotic despite receiving pre-travel counseling and an antibiotic prescription for self-treatment. Underutilization of antibiotics for self-treatment has been reported in other observational cohorts, with rates ranging from 7% to 45%, although these studies did not stratify by severity of TD.7, 8, 16 Most patients with moderate-severe TD in our cohort experienced mild, self-limited diarrhea (4 stools/day lasting 1–2 days), which could explain why they were inclined to defer self-treatment or use loperamide alone. We did not observe a benefit associated with taking antibiotics for moderate-severe diarrhea, likely due to the self-limited TD episodes in our cohort along with the poor compliance with the travel illness diaries and underutilization of antibiotics for self-treatment, limiting the sample size for determining the impact of self-treatment on outcome. Further studies are needed to systematically evaluate pre-travel counseling regarding use and timing of self-treatment, traveler adherence, and impact of non-compliance on outcomes.

IBS occurred in 3.4% of the overall cohort, similar to rates reported in previous studies20–23. TD was not associated with increased risk of IBS as reported in prior studies, which could be related to mild nature of TD in our cohort and the infrequency of IBS24. In participants with TD, rates of PI-IBS were higher with moderate-severe diarrhea (7% vs. 1.4% for mild diarrhea) and diarrhea lasting > 1 day (7% vs. 2% for ≤ 1 day), although these findings did not reach statistical significance. In addition, TD cases who did not take an antibiotic developed PI-IBS more frequently than antibiotic-treated cases (4.8% vs. 2.2%). Experimental evidence suggests that PI-IBS may result from uncontrolled chronic inflammation following infectious diarrhea, and similar associations between duration and severity of infectious diarrhea and PI-IBS have been reported previously.25–29 Further studies are needed to identify travelers that are high risk for development of PI-IBS and design prospective studies to evaluate the use of prophylactic and therapeutic strategies.

Research in travel medicine poses unique methodological challenges including the heterogeneity of the population, travel itineraries, utilization of pre-travel health care, and recall bias on post-travel surveys. Selection bias may have influenced our results since participants were enrolled at travel clinics, representing a different risk profile compared to individuals who do not seek pre-travel health care or see non-specialist providers. Poor compliance with completion of travel illness diaries limited our analyses for effectiveness of self-treatment and risk of IBS.

In conclusion, our results indicate suboptimal use of self-treatment in patients with moderate or severe TD. Additional studies are needed to systematically evaluate the possible causes including the knowledge, attitudes and practice patterns of providers, adherence to counseling by travelers and the impact of suboptimal TD self-treatment on outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Flow diagram of participants included in the travelers’ diarrhea (TD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) analyses

Acknowledgments

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the NIH or the Department of Health and Human Services, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the DoD or the Departments of the Army, Navy or Air Force. Mention of trade name, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the US Government.

Funding

The study was supported by the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program (IDCRP), a Department of Defense (DoD) program executed through the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under the Inter-Agency Agreement Y1-AI-5072.

Footnotes

** This study was presented in part at the 62nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH), Washington, DC, USA, November 2013.

Some authors are employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties.

Declaration of Interests

The authors state they have no financial conflicts or disclosures to report

REFERENCES

- 1.Ericsson CD, DuPont HL, Okhuysen PC, et al. Loperamide plus azithromycin more effectively treats travelers' diarrhea in Mexico than azithromycin alone. J Travel Med. 2007;14(5):312–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dupont HL, Jiang ZD, Belkind-Gerson J, et al. Treatment of travelers' diarrhea: randomized trial comparing rifaximin, rifaximin plus loperamide, and loperamide alone. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(4):451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders JW, Frenck RW, Putnam SD, et al. Azithromycin and loperamide are comparable to levofloxacin and loperamide for the treatment of traveler's diarrhea in United States military personnel in Turkey. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(3):294–301. doi: 10.1086/519264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(3):331–351. doi: 10.1086/318514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diemert DJ. Prevention and self-treatment of traveler's diarrhea. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(3):583–594. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00052-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Cabada Bauche J, Dupont HL. New Developments in Traveler's Diarrhea. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7(2):88–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill DR. Occurrence and self-treatment of diarrhea in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62(5):585–589. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitzurra R, Steffen R, Tschopp A, Mutsch M. Diarrhoea in a large prospective cohort of European travellers to resource-limited destinations. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalani T. TravMil: Deployment and Travel Related Infectious Disease Risk Assessment, Outcomes, and Prevention Strategies Among Department of Defense Beneficiaries. Atlanta, GA: American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; 2012. Advances in Pre- and Post-Travel Infectious Disease Risk Management Systems. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey K, Esposito DH, Han P, et al. Surveillance for travel-related disease--GeoSentinel Surveillance System, United States, 1997–2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1377–1390. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Sonnenburg F, Tornieporth N, Waiyaki P, et al. Risk and aetiology of diarrhoea at various tourist destinations. Lancet. 2000;356(9224):133–134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02451-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steffen R, Tornieporth N, Clemens SA, et al. Epidemiology of travelers' diarrhea: details of a global survey. J Travel Med. 2004;11(4):231–237. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.19007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steffen R, van der Linde F, Gyr K, Schar M. Epidemiology of diarrhea in travelers. JAMA. 1983;249(9):1176–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill DR. Health problems in a large cohort of Americans traveling to developing countries. J Travel Med. 2000;7(5):259–266. doi: 10.2310/7060.2000.00075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soonawala D, Vlot JA, Visser LG. Inconvenience due to travelers' diarrhea: a prospective follow-up study. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:322. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattila L, Siitonen A, Kyronseppa H, et al. Risk Behavior for Travelers' Diarrhea Among Finnish Travelers. J Travel Med. 1995;2(2):77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.1995.tb00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shlim DR. Looking for evidence that personal hygiene precautions prevent traveler's diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 8):S531–S535. doi: 10.1086/432947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steffen R, Collard F, Tornieporth N, et al. Epidemiology, etiology, and impact of traveler's diarrhea in Jamaica. JAMA. 1999;281(9):811–817. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.9.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitzurra R, Fried M, Rogler G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome among a cohort of European travelers to resource-limited destinations. J Travel Med. 2011;18(4):250–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stermer E, Lubezky A, Potasman I, et al. Is traveler's diarrhea a significant risk factor for the development of irritable bowel syndrome? A prospective study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(7):898–901. doi: 10.1086/507540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okhuysen PC, Jiang ZD, Carlin L, et al. Post-diarrhea chronic intestinal symptoms and irritable bowel syndrome in North American travelers to Mexico. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(9):1774–1778. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilnyckyj A, Balachandra B, Elliott L, et al. Post-traveler's diarrhea irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(3):596–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair P, Okhuysen PC, Jiang ZD, et al. Persistent abdominal symptoms in US adults after short-term stay in Mexico. J Travel Med. 2014;21(3):153–158. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connor BA. Sequelae of traveler's diarrhea: focus on postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 8):S577–S586. doi: 10.1086/432956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Spiller RC. Distinctive clinical, psychological, and histological features of postinfective irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(7):1578–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neal KR, Hebden J, Spiller R. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: postal survey of patients. BMJ. 1997;314(7083):779–782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ji S, Park H, Lee D, et al. Post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome in patients with Shigella infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(3):381–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connor BA, Riddle MS. Post-infectious sequelae of travelers' diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2013;20(5):303–312. doi: 10.1111/jtm.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Flow diagram of participants included in the travelers’ diarrhea (TD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) analyses