Abstract

Anorectal disorders such as dyssynergic defecation, fecal incontinence, levator ani syndrome and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome are common, and affect both the adult and pediatric populations. Although they are treated with several treatment approaches, over the last two decades, biofeedback therapy using visual and verbal feedback techniques has emerged as an useful option. Because it is safe, it is commonly recommended. However, the clinical efficacy of biofeedback therapy in adults and children is not clearly known, and there is a lack of critical appraisal of the techniques used and the outcomes of biofeedback therapy for these disorders. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility convened a task force to examine the indications, study performance characteristics, methodologies used and the efficacy of biofeedback therapy, and to provide evidence-based recommendations. Based on the strength of evidence, biofeedback therapy is recommended for the short term and long term treatment of constipation with dyssynergic defecation (Level I, Grade A), and for the treatment of fecal incontinence (Level II, Grade B). Biofeedback therapy may be useful in the short-term treatment of Levator Ani Syndrome with dyssynergic defecation (Level II, Grade B), and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome with dyssynergic defecation (Level III, Grade C), but the evidence is fair. Evidence does not support the use of biofeedback for the treatment of childhood constipation (Level 1, Grade D).

Keywords: Biofeedback therapy, dyssynergic defecation, constipation, fecal incontinence, levator ani syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Anorectal disorders such as dyssynergic defecation, fecal incontinence and levator ani syndrome are common and affect up to 25% of the adult and pediatric populations. They significantly affect quality of life and pose a major health care burden (1–3). Although these disorders are treated with several approaches including laxatives, antidiarrheals, botulinum toxin or dextranomer injections, electrical and sacral nerve stimulations and surgery (1,2,4), biofeedback therapy using visual and verbal feedback techniques has emerged as a useful treatment option. However, a critical appraisal of the techniques used and the outcomes of biofeedback therapy are lacking.

The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility convened a task force to examine the indications, study performance characteristics, methodologies used and the scientific basis, noting especially the results of randomized controlled trials and the impact of biofeedback therapy on patient reported outcomes, objective measurements and quality of life. These measures were used to provide evidence-based recommendations regarding the clinical utility and efficacy of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation, fecal incontinence, levator ani syndrome, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome and childhood constipation.

Pubmed, Embase, Medline, and PsychInfo databases from inception to August 2014 were used to identify appropriate studies in adults and children. Inclusion criteria included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and those that compared biofeedback with standard care, placebo or no treatment. If unavailable, uncontrolled studies were examined. Treatment recommendations were based on grading recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (5).

BIOFEEDBACK THERAPY FOR DYSSYNERGIC DEFECATION

Introduction

Neuromuscular dysfunction of the defecation unit can lead to disordered or difficult defecation. Dyssynergic defecation (DD) is the most common defecation disorder that affects about 40% of patients with chronic constipation (6). It is an acquired behavioral disorder where the act of stooling is uncoordinated or dyssynergic (6). Physiologic testing may demonstrate one or more abnormalities when attempting to defecate: (a) paradoxical anal contraction, (b) incomplete anal relaxation, (c) inadequate push effort, or (d) elevated threshold for the sensation of stooling (rectal hyposensitivity). Whole gut transit time may be delayed in up to 2/3rds of these patients, but this is believed to be secondary to the outlet dysfunction rather than a cause of defecatory dysfunction (6–8).

Indications

Patients with chronic constipation and DD who fulfill the criteria shown in Table 1 are eligible for biofeedback therapy (6–8). Contraindications include severe neurological disorders, inability to sit on a commode, developmental disability and visual impairment.

Table 1.

|

Study Performance

Technical Aspects

The goal of biofeedback training is to improve bowel function by restoring a normal pattern of defecation. Biofeedback therapy is an instrument-based learning process that is based on “operant conditioning” techniques. The governing principle is that any behavior when reinforced repeatedly can be learned and perfected. In patients with dyssynergic defecation, the goal of biofeedback training is three-fold (8–10):

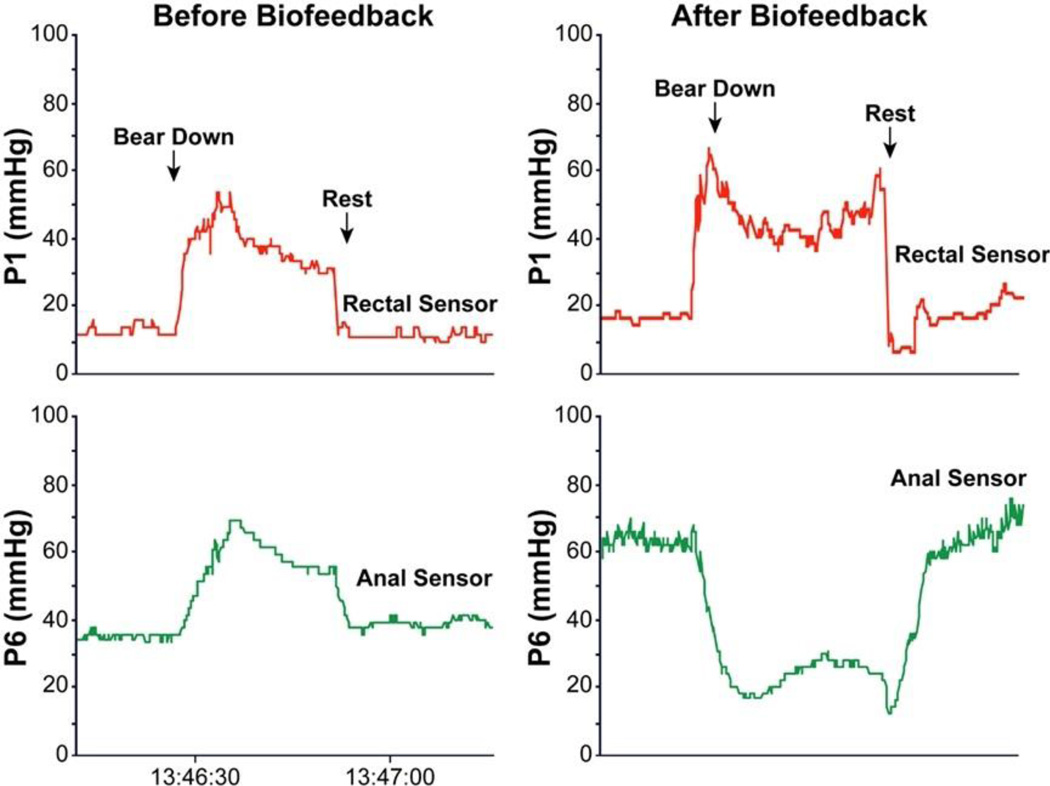

To correct the dyssynergia or incoordination of the abdominal, rectal, puborectalis and anal sphincter muscles in order to achieve a normal and complete evacuation (Fig. 1).

To facilitate normal evacuation by simulated defecation training using balloons.

To enhance rectal sensory perception in patients with impaired rectal sensation.

Fig 1.

The rectal and anal pressure changes, and manometric patterns in a patient with constipation and dyssynergic defecation, before and after biofeedback showing paradoxical anal contraction at baseline that improved after 5 sessions of biofeedback therapy

(i) Correct dyssynergia and improve rectoanal coordination

The purpose of this training is to produce a coordinated defecatory movement that consists of an abdominal push effort synchronized with relaxation of the pelvic floor (Fig. 1). This is achieved by manometric or electromyographic (EMG)-guided training of the abdominal push effort (diaphragmatic and abdominus rectus muscle training) together with anal relaxation.

The subject should be seated on a commode with the manometry/EMG probe in situ. The monitor display of the pressure/EMG changes from the rectum and anal canal provides visual feedback and facilitates learning (Fig. 1). First, their posture and breathing techniques during attempted defecation are corrected. Next, at least 10–15 bearing down maneuvers is performed. Additional bearing down maneuvers may be performed with a 60 cc balloon inflated in the rectum in order to provide a sensation of stooling. After few sessions the patient is encouraged to perform these maneuvers without visual or verbal feedback.

(ii) Facilitate simulated defecation training

The goal here is to teach the subject to expel a 50 ml water or air-filled balloon by using gentle traction to supplement the patient’s efforts, preferably in the seated position on a commode.

(iii) Sensory training

The objective of this optional training is to improve the thresholds for rectal sensory perception and to promote better awareness for stooling in patients with rectal hyposensitivity (9,11). This is performed by intermittent inflation of the balloon in the rectum. The goal is to teach the subject to perceive a lower volume of balloon distention but with the same intensity as experienced with a higher volume. Thus, by repeated inflations and deflations newer sensory thresholds can be established (8,9).

Duration and Frequency of Training

The number of sessions and frequency of sessions should be customized for each patient. Typically, training sessions are performed biweekly and each session takes one hour, and on average, 4 to 6 training sessions are required; periodic reinforcements at additional intervals may provide benefit (9,12), but its role has not been examined. Patients are encouraged to practice diaphragmatic breathing and attempted defecation maneuvers at home for at least 15 minutes, two or three times a day (11–15). Training is discontinued when patients demonstrate: (i) consistent coordinated pattern of defecation with anal relaxation; (ii) improved stooling habit; and (iii) normal balloon expulsion time.

Devices and Techniques for Biofeedback

Because biofeedback is an instrument-based learning technique, several devices and methods are available including solid-state manometry systems, catheters with microballoons or perfusion ports, anal EMG probes, and home training devices (8). A manometry probe with microtransducers located in anal canal and a rectal balloon has the advantage of displaying rectal and anal pressure changes accurately and this may facilitate training of rectal propulsive forces (increases in rectal pressure produced by the diaphragm and abdominal muscle contraction), anal relaxation and sensory training. EMG probes provide information on the striated anal muscles but do not provide information on rectal propulsive forces.

Efficacy of Biofeedback Therapy and Randomized Controlled Trials (Table 2)

Table 2.

Summary of randomized controlled trials of biofeedback therapy for Dyssynergic Defecation

| Rao et al (11) | Rao et al (12) | Chiarioni et al (13) | Heymen et al (14) | Chiarioni et al (15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Design | Biofeedback (manometry pressure) vs. Standard treatment vs. Sham biofeedback |

Biofeedback (Manometry pressure) vs Standard therapy |

EMG Biofeedback for slow transit vs Dyssynergia |

EMG Biofeedback vs Diazepam 5 mg vs placebo |

EMG Biofeedback vs PEG 14.6 gms |

| Subjects and Randomization and Intervention(s) |

77 (69 women) 1:1:1 distribution Standard: diet, exercise, laxatives Sham: Progressive muscle relaxation with anorectal probe |

52; Short term therapy 26= long term study 12= biofeedback 13= standard therapy Standard: diet, exercise, laxatives (titrated) |

52 (49 women) 34 dyssynergia 12 slow transit 6 mixed |

84 (71 women) 30 biofeedback 30 diazepam 24 placebo |

109 (104 women) 54 biofeedback 55 polyethylene glycol |

| Duration & Number of biofeedback sessions |

3 months, Biweekly, one hour, maximum of six sessions over three months, performed by biofeedback nurse therapist |

One year; 6 active therapy sessions and 3 reinforcement sessions at 3 month intervals |

5 weekly 30 minute training sessions, performed by physician investigator |

6 bi-weekly, one hour sessions |

3 months & 1 year, 5 weekly, 30 minute training sessions performed by physician investigator |

| Primary outcomes |

|

Number of complete spontaneous bowel movements Secondary Outcome; Presence of dyssynergia Balloon expulsion time Global satisfaction |

Symptom improvement None=1 Mild=2 Fair=3 Major=4 |

Global Symptom relief | Global Improvement of symptoms Worse=0 No improvement=1 Mild=2 Fair=3 Major improvement=4 |

| Dyssynergia corrected or symptoms improved |

Dyssynergia corrected at 3 months in 79% with biofeedback vs 4% sham and 6% in Standard group ; CSBM= Biofeedback group vs Sham or Standard, p<0.05 |

No of CSBM/week increased significantly in biofeedback 9p<0.001 Dyssynergia pattern normalized 9p<0.0010 Balloon expulsion improved (p<0.001) Colonic transit normalized (p<0.01) |

71 % with dyssynergia and 8% with slow transit alone reported fair improvement in symptoms |

70% improved with biofeedback compared to 38% with placebo and 30 % with diazepam, (p<0.01) |

79.6% reported major improvement at 6 and 12 months 81.5% reported major improvement at 24 months |

| Conclusions | Biofeedback was superior to sham feedback and standard therapy |

Biofeedback is superior to standard therapy |

Biofeedback benefits dyssynergia and not slow transit constipation |

Biofeedback is superior to placebo and diazepam |

Biofeedback was superior to laxatives |

Several randomized controlled trials have been reported in adults with dyssynergic defecation and are summarized in Table 2 (11–15). Although there are methodological differences between the studies including recruitment criteria, end points and outcome measures, all studies have concluded that biofeedback therapy is superior to controlled treatment approaches including diet, exercise and laxatives (11,12), polyethylene glycol (15), diazepam/placebo tablets (14), balloon defecation therapy (16) and sham feedback therapy (11).

Both short-term and one year long-term outcome studies have shown that biofeedback is superior to standard therapy alone in patients with DD (12). A meta-analysis of 7 studies involving biofeedback compared to any other treatment suggested that biofeedback conferred a six-fold increase in the odds of treatment success (odds ratio 5·861 (95% CI, 2·2 to 15·8); (17). Predictors for successful therapy include harder stool consistency (P = 0.009), greater willingness to participate, higher resting anal sphincter pressure, and prolonged balloon expulsion time, with sensitivity and specificity of 0.79 to 0.81, respectively. A longer duration of laxative use was associated with poor outcome (18). DD is associated with significant impairment in QOL (19). In a prospective RCT of 100 patients, biofeedback therapy, administered at home or in-office improved most QOL domains in patients with DD (20).

Strengths & Confounding Issues

Biofeedback therapy is a labor-intensive approach but has no adverse effects. However, it is only offered in a few centers and is performed by nurse therapists or physiotherapists. In order to treat the vast number of constipated patients in the community, a home based, self-training program is desirable. Uncontrolled studies of home trainers have reported that biofeedback is useful (21,22). However, there is no standard or approved device. A recent RCT showed that home biofeedback is as useful as office biofeedback therapy in improving symptoms and anorectal function (23). Also, treatment success may be best defined by a combination of improvement in bowel function such as ≥1 CSBM/week + correction of dyssynergia pattern, but such measures have not been used in clinical trials.

The mechanism of action of biofeedback therapy is not fully understood. Improvements in defecation appear to be mediated by enhanced rectal propulsive forces and by anal and pelvic floor relaxation and by improved sensory thresholds (11–15,24). Recent studies using bidirectional cortical evoked potentials and transcranial magnetic stimulations have revealed significant bi-directional brain-gut dysfunction in patients with dyssynergic defecation (25), and biofeedback appears to improve these dysfunctions (26).

Because biofeedback is an instrument-based treatment, standardization of both equipment and protocols is desirable. At present, both EMG and pressure-based biofeedback therapy protocols have been used, and both appear to be efficacious, but comparative trials are lacking. EMG probes are cheaper, more durable and usually provide one or two- channel display whereas manometric systems are more expensive, provide multiple channel display and because they have a balloon and rectal sensor they can facilitate recto-anal coordination and sensory training. A recent systematic review concluded that there is currently “insufficient evidence to allow firm conclusions regarding efficacy and safety of biofeedback for treatment of chronic constipation (27). However, this review addressed the use of biofeedback in all patients with constipation, for example, it included studies that evaluated biofeedback therapy for conditions that are not always associated with disordered defecation (eg, rectal prolapse and slow transit constipation). In fact, biofeedback therapy does not benefit constipated patients without dyssynergic defecation (13). Hence, including patients with these disorders as well as many other suboptimal and non-randomized older studies in the meta analysis, most likely diluted the benefit of biofeedback therapy, and led to an inappropriate conclusion regarding its use in defecation disorders. Lastly, the review determined that blinding was suboptimal and there was a risk of bias; however, the ability to blind subjects to treatment assignment in behavioral trials is limited and the risk of bias definition used for drug trials cannot be applied to behavioral trials. Hence, these factors should not weigh against the rigorous quality of randomized controlled trials for biofeedback therapy. It is essential that only patients who fulfill the criteria for dyssynergic defecation be offered this treatment modality.

RECOMMENDATION

Biofeedback therapy is recommended for the short term and long term treatment of constipation with dyssynergic defecation. Level I, Grade A.

BIOFEEDBACK THERAPY FOR FECAL INCONTINENCE

Introduction

Fecal Incontinence affects approximately 8.3% of the population and its treatment remains unsatisfactory. Biofeedback has been shown to be a useful treatment approach (1,2,4).

Indications

Patients with FI who have not responded to conservative medical treatment measures including a trial of antidiarrheals or fiber supplements. Patients must have adequate cognitive ability and be motivated to participate in this training program. Contraindications include neurological disorders such as spinal cord injury, severe internal anal sphincter injuries resulting in absence of resting anal canal pressure, dementia, developmental disability, uncontrolled psychotic disorder, age younger than 8 years, and visual impairment.

Study Performance

Technical Aspects

Biofeedback involves the use of electronic or mechanical devices to provide augmented awareness of physiological responses to patients and their therapists to facilitate neuromuscular retraining. The goals are to correct the physiological deficits that contribute to FI by (1) improving the strength and isolation of pelvic floor muscles, (2) improving the ability to sense weak distentions of the rectum and contract pelvic floor muscles in response to these distentions, and/or (3) improving the ability to tolerate larger rectal distentions without experiencing uncontrollable urge sensations (28–34).

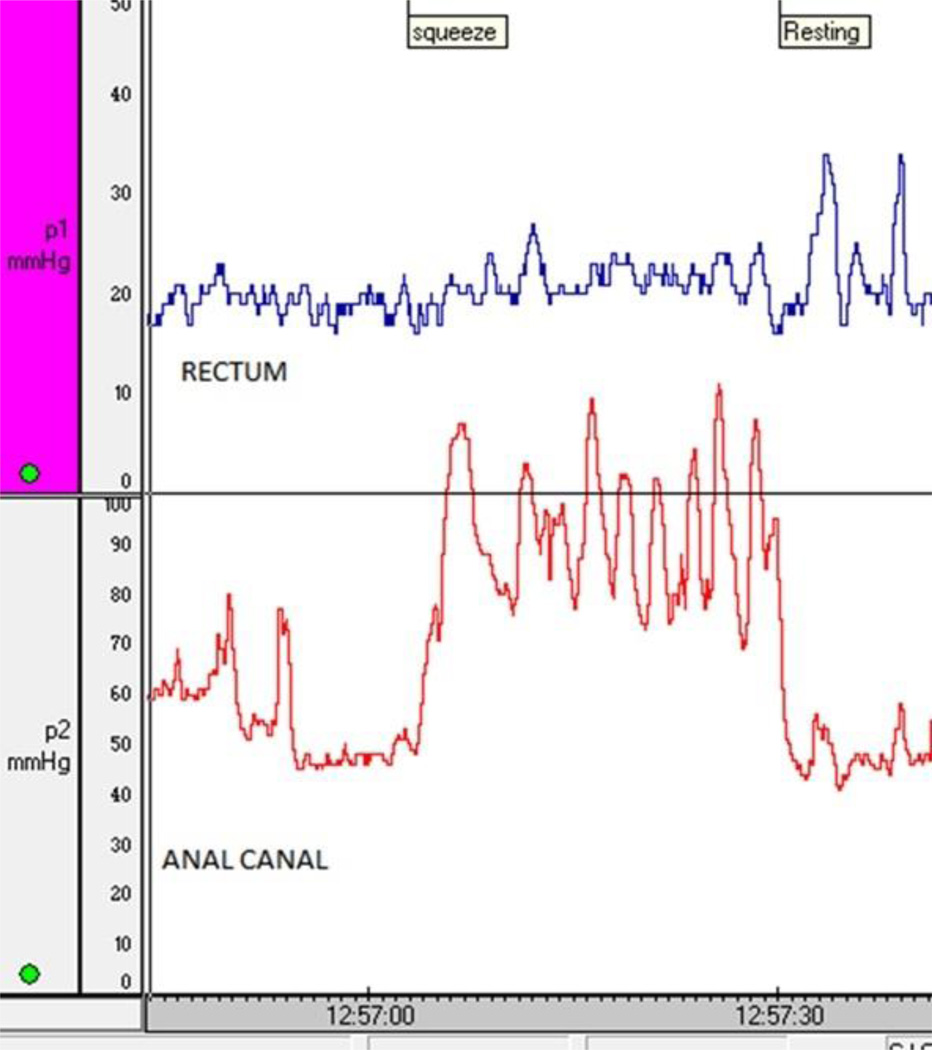

(i) Anal and pelvic floor muscle training

First, patients are instructed to isolate the anal sphincter and puborectalis muscles and improve its strength by using modified Kegel exercises in the sitting or lying position with a probe in situ. Visual and verbal feedback techniques are used to reinforce the maneuvers, as they are being performed. The anal and rectal pressure changes displayed on the monitor provides visual feedback to the patient. The verbal feedback is provided by the physician/nurse therapist and consists of either complimenting the patient for performing a correct maneuver or rectifying any errors. The patient is instructed to squeeze and to maintain the squeeze for as long as possible. During the maneuver, the patient observes the monitor and is educated about the changes in anal pressure/EMG activity. For comparison, a normal recording is shown (32). As the sphincter strength improves, the patient is encouraged to maintain a voluntary contraction for at least 30 s. Patients are instructed not to use their abdominal or gluteal muscles to achieve a voluntary squeeze. After a few sessions, the patient is encouraged to perform these maneuvers without visual feedback (32,33). Also, the patient is instructed to perform squeeze exercises at home for at least 20 min, two to three times a day, and to perform about 20 squeeze maneuvers per session. Training may be discontinued when patients demonstrate (1) reduction in the number of incontinence episodes; (2) improvement in anal squeeze pressure and rectoanal coordination when squeezing. Patients also receive sensory-motor coordination training. The objective here is to achieve a maximum voluntary squeeze in less than 1 second after inflation of a rectal balloon and to control the reflex anal relaxation by consciously contracting the sphincter muscles (28,29,32).

(ii) Sensory Training

Patients found to have an impaired rectal sensation may benefit from sensory training (29–31). In brief, a series of progressively smaller balloon inflations are performed, starting with the volume that induced a sensation of urge to defecate, and decreasing by 5–10 ml with each successive distention. The patient is instructed to respond to the rectal distention by squeezing their anal sphincters. When the patient fails to perceive the balloon inflation, this defines the sensory threshold. Sensory discrimination training is used to train the patient to recognize and respond to lower balloon volumes; the balloon is distended with slightly higher, and on others trials slightly lower volumes than the current threshold. The patient is encouraged to focus on any sensation they feel in their rectum even if it is not the sensation they were expecting, and to squeeze in response to it. They are encouraged to watch for these sensations when they are at home (between training sessions) and to always squeeze when they think they feel something, even if they are not sure. They are told that it does not hurt to squeeze extra times if there is a chance this could prevent an accident.

(iii) Urge Resistance Training

Patients who have accidents that are preceded by a strong, uncontrollable urge to defecate are desensitized to the sensations of rectal balloon inflation by distending the rectal balloon in a step-wise fashion with progressively larger volumes of air until a strong urge is experienced. Once this strong urge threshold is identified, some air is removed from the balloon and the patient is taught to relax using a deep breathing technique. They are encouraged to use relaxation to counteract the urge sensation while the balloon is gradually inflated again. This process is repeated several times during the training session. The goal is to teach the patient how to use relaxation as a coping mechanism to enable them to tolerate larger volumes of balloon inflation. For home practice, they are taught to use relaxation to counteract urge sensations at home and to “Walk; don’t run” to the toilet when they feel an urge.

Duration and Frequency of Training

Typically, treatment sessions are performed biweekly (32,35), although different intervals may be used. The number of sessions may be customized for each patient but usually six sessions are performed. Each session takes approximately one hour.

Devices and Techniques for Biofeedback

Commonly a manometry system (pressure sensors) or EMG probe is used (32,33,35,36), and rarely an anal ultrasound probe (34) or a home training device has been used (33).

Efficacy of Biofeedback therapy & Randomized Controlled Trials (Table 3)

Table 3.

Selected randomized controlled trials of biofeedback therapy and/or exercises for fecal incontinence in adults.

| References | Subjects (F/M) |

Baseline FI/Week | Previous PFM training |

Sphincter defects |

Treatment | Control | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fynes (30) | 40/0 | NA | NA | All included (Obstetric trauma) |

-BFB -Electrical stimulation (weekly,12 wks) |

Vaginal manometric biofeedback |

Augmented group improved symptoms more than control (p = <0.001) |

| Ilnycki (31) | 17/8 | At least once a week |

None | Major defect excluded |

-Manometric biofeedback -Rectal sensory training -Coordination training (cross over – weekly, 4 weeks) |

Sham training (cross over) |

Biofeedback improved symptoms |

| Heymen (32) |

83/25 | Mean = 5.2 | NA | Surgical candidate excluded |

-BFB -PFMT sensory training (biweekly, 12 wks) |

PFMT | BFB improved symptoms more than PFMT (77% vs 41%, P= 0.001) |

| Norton (33) | 159/12 | Median = 2 | Excluded | Major defect excluded |

4 groups: 1. Education + advice 2. As group 1 + PFMT 3. As group 2 + manometric biofeedback 4. As group 3 + home BFB (biweekly, 6 sessions, 3 months) |

See 4 treatment groups |

∼ 54 % improved in all groups NSD in symptoms & QOL between groups |

| Solomon (34) |

107/13 | “Mild to Moderate” | NA | All excluded | 3 groups: 1. PFMT 2. PFMT + anal ultrasound biofeedback 3. PFMT + manometric biofeedback (monthly, 5 sessions) |

See groups | NSD in symptoms & QOL & manometry changes between groups |

| Heymen (37) |

60/0 | NA | All subjects | All included | BFB (weekly,12 wks) |

BFB + electrical stimulation | NSD between groups |

| Naimy (38) | 49/0 | NA | NA | Major defect excluded |

-BFB -Home exercises |

Electrical stimulation |

Both groups improved NSD in symptoms & QOL between groups |

| Schwandner (39) |

138/20 | NA | NA | All included | Electrical Stimulation combined with EMG biofeedback twice daily at least 3 months |

EMG Biofeedback twice at home for at least 3 months |

Combine Tx produce greater reduction in Cleaveland Clinic FI Score (8 VS 5 Points) and more patients achieved continence (50% vs 26%) |

BFB = Biofeedback training using electromyography probe; VAS= Visual analog scale; NSD= Not significantly different;QOL= Quality of life; PFMT= Pelvic floor muscle training. NA= Not available

RCTs of biofeedback for FI have yielded inconsistent results (30–34, 37,38,39). Two earlier studies (33,34) showed no benefit for biofeedback compared to pelvic floor exercises taught by digital rectal exam, while a third study (32) showed a clear superiority for biofeedback compared to pelvic floor exercises taught verbally. In the third study, which had the strongest design, patients with severe FI (at least weekly solid or liquid stool accidents) first underwent a one-month screening period on conservative management, and patients who achieved adequate relief were excluded from further participation (32). The remaining 108 patients underwent biofeedback training by an experienced biofeedback therapist during 6 biweekly sessions and were reassessed at 3 months and 12 months follow up. In the intent to treat analysis, 76% of biofeedback patients vs. 41% of pelvic floor exercise patients improved at 3 months follow up (p<0.001) and patients using biofeedback had greater reductions in Fecal Incontinence Severity Index (FISI) scores. Results were well maintained at 12 months in this and in an independent, uncontrolled study (36). Anal sphincter exercises (pelvic floor muscle training) and biofeedback therapy have been used alone and in combination for the treatment of FI. Anal sphincter exercises are performed to strengthen the puborectalis and EAS muscles (32,33,35,36). A single-center, randomized controlled study indicated that a regimen of pelvic floor exercises with biofeedback was nearly twice as effective as pelvic floor exercises alone, with 44% vs. 21% of patients achieving complete continence at 3 months, respectively (P = 0.008) (35). In a more recent randomized study comparing 2 different pelvic floor exercise regimens, both with biofeedback, 59 of the 69 patients (86%) had improved continence with 20% fully continent, with no statistically significant differences between exercise regimens (40). A 2012 systematic review of randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials of patients performing anal sphincter exercises and/or receiving biofeedback and/or surface electrical stimulation of the anal sphincter concluded that the addition of biofeedback or electrical stimulation was superior to exercise alone in patients who had previously failed to respond to other conservative treatments, but overall there was insufficient evidence for biofeedback therapy or one method of therapy (35).

In patients with reduced rectal sensation, there is objective evidence that biofeedback therapy can improve rectal sensation (29,36,41) and shorten the latency between rectal distention and contraction of the external anal sphincter (41). While anal resting and squeeze pressure increased after some studies of biofeedback therapy, effects were relatively small (35). The American College of Gastroenterology (1), and the Rome Foundation (7) recommends biofeedback for the treatment of FI.

Strengths & Confounding Issues

It is important to recognize some differences in study methodology among the key RCTs of biofeedback therapy that are summarized in table 3. One study (32) systematically screened patients for one month and excluded those who achieved adequate relief with conservative management, and required that patients have at least moderately severe FI (two or more episodes of FI per week) prior to treatment. However, others (33,34) included patients with mild FI and did not exclude those who could benefit from conservative treatment alone. Two studies (31,37) were underpowered, and the one (31) used a cross-over design but did not demonstrate return to baseline following the first intervention. Thus, further research is needed to standardize the treatment protocols and the training of biofeedback therapists. Treatment success is best defined by an improvement in bowel function such as 50% reduction in episodes of fecal incontinence, but this measure has not been used in clinical trials.

Alternative/comparative approaches

Pelvic floor exercises alone are nearly always recommended to patients with FI, but there is little consensus on how they should be taught. There are no known RCTs (33). In some recent studies, pelvic floor exercises were taught by a health care provider during a digital rectal examination, and reductions in FI from baseline were comparable to those achieved with biofeedback training using electronic devices (33). Electrical stimulation of the anal mucosa is not effective when used as the sole treatment for FI (38). However, mucosal electrical stimulation may augment the effects of biofeedback (39) and merits further RCT.

RECOMMENDATION

Biofeedback therapy is recommended for the short term and long term treatment of fecal incontinence. Level II, Grade B.

BIOFEEDBACK THERAPY FOR LEVATOR ANI SYNDROME AND SOLITARY RECTAL ULCER SYNDROME

INTRODUCTION

Levator ani syndrome (LAS) is characterized by chronic or recurrent anorectal pain or aching lasting at least 20 min, without any structural or systemic disease (7). Its exact prevalence is unknown. It is part of a spectrum of painful anorectal disorders. LAS is associated with tenderness of the levator ani muscle during digital rectal examination (7), and increased anal canal resting pressures. In a recent study, 85% of patients with LAS showed dyssynergic defecation, i.e., paradoxical contraction or failure to relax the pelvic floor muscles when straining to defecate plus inability to evacuate a water-filled rectal balloon (42).

Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome (SRUS), is characterized by single or multiple ulcers in the rectum with specific histological inflammatory changes, and is associated with symptoms of excessive straining, chronic or recurring anal or rectal discomfort, use of digital maneuvers to defecate, and frequent blood and mucus discharge (43, 44). Manometric studies have revealed dyssynergia in up to 2/3rds of patients with SRUS (44, 45), and this may develop secondary to painful defecation. It has been suggested that excessive straining over years may lead to rectal mucosal intussusception; repeated trauma of the prolapsing rectal mucosa together with dyssynergia may lead to a stretch injury or ischemic ulceration (44, 45).

Indications

-

-

Levator Ani Syndrome: (i) Patients unresponsive to standard therapies including antispasmodics and muscle relaxants. (ii) Absence of structural or inflammatory causes of chronic anorectal pain and pelvic pain. (iii) Demonstrable tenderness of levator ani muscle on digital rectal exam.

-

-

Solitary Rectal Ulcer Syndrome: (i) Endoscopically and histologically proven SRUS. (ii) SRUS unresponsive to behavioral measures including avoiding excessive straining, laxatives, topical therapies such as sucralfate or 5-ASA.

Study performance and technical aspects

Studies of biofeedback therapy for these disorders have used methods, techniques and protocols similar to those described under the section of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation (11–14, 43, 44, 46).

Efficacy of Biofeedback Therapy & randomized Controlled Trials

Reports of biofeedback treatment for chronic functional anorectal pain have shown inconsistent results, and most of these were small and uncontrolled (46) However, a recent RCT of 157 well-characterized patients with LAS compared three treatments: biofeedback to teach pelvic floor muscle relaxation, electrogalvanic stimulation (EGS) to relax the pelvic floor, and digital massage of the levator muscles (42). The primary outcome measure was the subjects’ report of adequate pain relief. Key to the interpretation of the study was an a priori decision to test for tenderness when traction was applied to the levator ani muscles during digital rectal examination, and patients were stratified into the three treatment arms based on the presence or absence of tenderness. Among patients with tenderness on physical examination, adequate relief was reported by 87% with biofeedback, 45% with EGS and 22% with digital massage. However, none of these three treatments were effective in patients who did not report tenderness on physical examination (42). The mixed results reported in previous biofeedback studies most likely were a consequence of failure to stratify patients based on the presence or absence of levator ani tenderness.

Biofeedback therapy has also been used to treat SRUS in open, short-term, small sized (less than 20 patients) studies (43,44). Inclusion criteria, physiological investigations and outcome parameters were variable. Biofeedback therapy was associated with symptom improvement in at least two thirds of patients with some histological improvement (44). Most notably, the highest successful outcome was reported when SRUS was associated with DD (44).

Strengths and confounding issues

The biofeedback training protocol that was developed originally to treat dyssynergic defecation also appears to be effective for the treatment of LAS in one large RCT, and possibly useful in SRUS based on uncontrolled trials. These observations suggest that DD may be a key pathophysiological dysfunction in both LAS and SRUS, although it is unknown why tense striated pelvic floor muscles cause pain in some patients, bleeding and ulceration with mucosal intussusception in others and only difficulty with defecation in the majority. Further characterization of the underlying pathophysiology of these disorders may shed more insights, and importantly confirmatory RCTs are needed for LAS and SRUS.

RECOMMENDATION

Biofeedback therapy may be useful for the short-term treatment of Levator Ani Syndrome with dyssynergic defecation (Level II, Grade B) and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome with dyssynergic defecation (Level III, Grade C), but the evidence is fair.

BIOFEEDBACK THERAPY FOR PEDIATRIC FUNCTIONAL CONSTIPATION

Introduction

Functional constipation (FC) and overflow fecal incontinence (FI) are commonly encountered in the pediatric population, with a worldwide prevalence of 3% (47) In most children, the purposeful or subconscious withholding of stool after having experienced the passage of a hard, painful or frightening bowel movement leads to FC. The retentive child learns to contract the pelvic floor, the anal sphincter, and the gluteal muscles in response to the urge to defecate so as to avoid defecation (3). The withholding behavior creates a vicious cycle of progressive accumulation of feces and hardening of stool, which when untreated causes stretching of the rectal wall and development of a megarectum. This in turn results in overflow FI, loss of rectal sensation and eventually loss of normal urge to defecate (3).

Anorectal manometry can demonstrate abnormal defecation dynamics in 50% of children with FC (48,49), and rectal barostat studies show impaired rectal sensation and higher rectal compliance (50). Conventional treatment consists of educating the parent and the child regarding correct defecation dynamics and behavioral interventions, such as toilet training, laxatives and/or enemas (51). Despite these interventions, only half of all children with constipation, followed for 6–12 months evacuate regular stools without laxatives (52). Thus, biofeedback therapy may be an option in children with chronic defecation disorders.

Indication

Functional constipation with dyssynergic defecation, which is unresponsive to conventional treatment.

Study Performance Characteristics

Technical aspects

The objective is to achieve normal evacuation by using visual and verbal biofeedback techniques and correcting the inadequate coordination of pelvic floor muscles and anal sphincter and by improving the awareness for stooling (urge to defecate). Biofeedback teaches children how to relax the external anal sphincter (EAS) with visual reinforcement (anorectal manometry and electromyography) in response to abdominal straining. The equipment used and principles of training including the duration and frequency of therapy sessions are similar to those described above for adult patients undergoing biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation. After reliable and consistent relaxation of EAS is accomplished, children are instructed to do the same without visual feedback.

Efficacy of biofeedback therapy & Randomized Controlled Trials (Table 4)

Table 4.

Summary of randomized controlled trials of biofeedback therapy for children with constipation

| Loening Baucke (48) |

Van der Plas et al (49) |

Wald et al ref (53) |

Davila et al (54) |

Nolan et al (55) |

Borowitz et al (56) |

Sunic-Omejc et al (57) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Design | Conventional treatment (use of laxatives, increase of dietary fiber and scheduled toileting) vs Conventional treatment + biofeedback |

Conventional treatment (toilet training, dietary advice, use of laxatives) vs conventional treatment + biofeedback |

Conventional treatment (toilet training, use of mineral oil as laxative) vs. conventional treatment + biofeedback |

Conventional treatment (enemas for three days + dietary advice + use of laxatives + toilet training) vs conventional treatment + biofeedback |

Conventional treatment (laxatives + behavioral modification) vs EMG biofeedback training |

Intensive medical care including laxatives (IMC) vs IMC + enhanced toilet training (EHT) vs IMC + ETT + EMG biofeedback |

Conventional treatment (toilet training, dietary advice, use of laxatives) vs conventional treatment plus biofeedback |

| Subjects and Randomizat on and Intervention( s) |

41 (31 boys, 5–16 yrs) 19 conventional treatment 22 biofeedback Sealed envelopes |

192 (126 boys, 5–16 yrs) 94 patients conventional treatment 98 biofeedback Allocation Concealment unclear |

50 (40 boys, 6–15 yrs) 26 Conventional treatment 24 biofeedback Allocation concealment unclear |

21 (14 boys, average age 9 yrs) 10 patients conventional 11 patients biofeedback block randomisation, allocation concealment unclear |

29 (24 boys, 4–14 yrs) 14 – conventional treatment 15 biofeedback Stratified blocked schedule by a person not connected with the study. Opaque numbered sealed envelopes stored sequentially |

87 (72 boys, 5–13 years) 26 conventional treatment 24 biofeedback Block randomisation, Outcome data collected by means of a computerize d voice mail data collection system |

49 (27 boys, 5–15 years) 24 conventional treatment 25 biofeedback Allocation concealment unclear |

| Duration & Number of biofeedback sessions |

up to six sessions of therapy 7 +/− 2 days apart. performed by physician investigator |

up to six sessions of therapy 7 +/− 2 days apart. 30 minutes training sessions performed by physician investigator |

4 sessions at week 0,2,4 and 8 weeks 30 minute training sessions performed by physician investigator |

8 sessions during a 4 week period performed by physician investigator |

Up to four sessions of biofeedback training were conducted at weekly intervals |

Number of biofeedback sessions unclear 30 minute training sessions performed by psychologist investigator |

Duration of the study was 12 weeks. Both study groups were followed weekly at the outpatient clinic. Number of biofeedback sessions is unclear. Duration of the session is not mentioned neither the person who gave the instructions |

| Primary outcomes |

Patients were considered to have recovered from chronic constipation and FI if they met the following criteria: > 3 bowel movements per week and ≤2 FI episodes per month while not receiving laxatives for 4 weeks |

Patients were considered to have recovered from chronic constipation and FI if they met the following criteria: > 3 bowel movements per week and ≤2 FI episodes per month while not receiving laxatives for 4 weeks |

Number of children cured or improved, number of bowel movements, FI episodes, anorectal manometric assessment |

Patients were considered to have recovered from chronic constipation and FI if they met the following criteria: > 3 bowel movements per week and ≤2 FI episodes per month |

Full remission was defined as no medication and no soiling for at least four weeks |

No episodes of fecal incontinence during the 2- week assessment, 12 months after initiation of therapy. |

Patients were considered to have recovered from chronic constipation and FI if they met the following criteria: > 3 bowel movements per week and ≤2 FI episodes per month without the use of a laxative |

| Success | Dyssynergia corrected at 7 months in 77% with biofeedback vs 13% in conventional group. At 7 and 12 months 5% and 16% in the conventional treatment recovered and 55% and 50% in the biofeedback- treated patients (p< 0.01 and p<0.05). |

Dyssynergia corrected at 6 weeks increased in the conventional group from 41% to 52% (not significant) and in the biofeedback group from 38% to 86% (p = 0.001). At 1 year, 59% in the conventional group recovered and 50% in biofeedback group (p = 0.24). |

55% success rates were reported in both groups at 3 months. No significant differences were found between the groups at 6 and 12 months; 62% vs 50% and 60% vs 50% respectively. |

Dyssynergia corrected at 4 weeks increased from 79.6 ± 10 to 97.9% ± 6 (p<0.001) in the biofeedback group vs 84 ± 7 to 93% ± 6 (ns) in the conventional group. At 4 weeks 90.8% recovered in the biofeedback. While it is unclear how many in the conventional group recovered. |

Dyssynergia corrected in all but one child. At six months’ follow up, laxative free remission was sustained in 2/14 patients in the biofeedback group and in 2/15 controls (95% confidence interval (CI) difference, −24% to 26%). |

At 12 months, the cure rates for each group were: IMC-36%, ETT −48%, and BF – 39%, respectively (ns). |

Correction of dyssynergia at 6 weeks increased in the conventional group from 50% to 58% (ns) and in the biofeedback group from 56% to 92% (p < 0.001). At 12 weeks, 63% in the conventional group and 84% in biofeedback group recovered (p< 0.05). |

| Conclusions | Biofeedback treatment is complementary to a good conventional therapeutic regimen in patients with constipation and abnormal defecation dynamics. |

Additional biofeedback training compared to conventional therapy did not result in higher success rates in chronically constipated children. Furthermore, achievement of normal defecation dynamics was not associated with success. |

Biofeedback was not superior to conventional treatment |

Biofeedback seems useful in the treatment of the child with constipation and FI |

No evidence of a lasting benefit in clinical outcome for biofeedback training in children who had treatment resistant or treatment dependent FI associated with abnormal defecation dynamics. |

Enhanced toilet training is more effective in treating childhood FI than either intensive medical therapy or anal sphincter biofeedback therapy. |

No clear evidence for long-term benefit of biofeedback therapy, despite recovery of abnormal anorectal dynamics and manometric parameters. |

Several RCTs have been reported in children and have also been systematically assessed in a recent ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN guideline (51). There are significant methodological differences among the published studies including recruitment criteria, end points and outcome measures. These are summarized in Table 4 (48, 49, 53–57). One single study included children with functional nonretentive fecal incontinence (FNRFI) and one study evaluated children with FI due to a myelomeningocele, and both were excluded from this analysis.

Seven trials compared biofeedback to conventional therapy, including education, toilet training and laxatives (58) Two studies only used surface EMG to provide biofeedback whereas others used anorectal manometry and EMG. Sample sizes ranged from 21 to 192 subjects, and only children who were older than 5 years were enrolled. Children should be at least 5 year old before starting biofeedback therapy (48, 49, 55, 56, 57), as attention span and ability to focus and not being intimidated by laboratory environment are important factors that contribute to treatment success. Three studies were conducted in outpatient clinics in USA, two in Europe, one in South America and one in Australia (Table 4). Four studies included children with chronic constipation and FI and the other three studies enrolled children with constipation associated with FI and pelvic floor dyssynergia. Follow-up varied from 6–18 months. Since allocation concealment was unclear in 5 studies and double blinding is not possible due to the nature of performing trials with behavioral interventions, the standard definitions for a risk of bias used in conventional drug studies cannot be directly applied to these studies. One study had a high risk of incomplete outcome data (51, 52). Number of biofeedback sessions depended on how soon the child learned to relax the EAS. Different outcome measures were used across all studies, such as defecation frequency, episodes of FI, use of laxatives and results of anorectal manometry, but the number of children improved or not cured was used as an outcome measure in all trials (51, 52).

A RCT by Loening-Baucke (48) compared biofeedback with conventional therapy (education, toilet training, laxatives) in 129 children (5–18 years of age) in USA, in an outpatient setting, with a follow-up period of four years. Whether the treatment allocation was concealed was unclear, and because blinding is not possible, meta-analysis adjudged a possible risk of bias. Patients were rated as recovered if they had ≥3 bowel movements per week and ≤2 FI episodes per month while off laxatives for at least one month. Results showed that biofeedback did not improve long-term recovery rates when compared to conventional therapy alone.

Another RCT by Van der Plas et al (49) evaluated the additional effect of biofeedback compared to conventional treatment (education, toilet training and laxatives) in 192 children with chronic constipation (5–16 years of age) in the Netherlands, in an outpatient tertiary care setting, with a follow-up period of 1 year. Although treatment allocation was concealed, blinding was not possible. Treatment was considered successful if the patients achieved three or more bowel movements per week and had less than two episodes of FI per month while not receiving laxatives for 4 weeks. The results showed that additional biofeedback compared to conventional therapy did not result in higher success rates in chronically constipated children. Furthermore, achievement of normal defecation dynamics was not associated with success.

After pooling the data and excluding the trials that either enrolled children with FNRFI or children with FI due to organic causes, there were no significant differences between biofeedback plus conventional treatment when compared to conventional treatment alone after 12 months for the number of children designated as cured or improved (OR 1.13; 95% CI 0.77–1.66) and 18 months (OR 1.42; 95% CI 0.79–2.53).

Strengths & Confounding issues

In these different RCTs, neither adverse effects nor cost-effectiveness analysis were reported, although risk is very small. Studies in constipated children have shown that abnormal defecation dynamics can begin at any age in childhood (58). Thus, it is possible that in the majority of these patients withholding behavior due to painful defecation could be avoided by early and adequate therapeutic intervention with laxatives and reassurance alone (59). Because many children are diagnosed late and fail to respond to laxative therapy, alternative therapies are often sought either by caregivers or medical providers. Although several pediatric studies show that biofeedback therapy results in an improvement of defecation dynamics and other parameters like maximal defecation pressure (49,55), it appears that the long-term treatment success does not differ between most children who have received biofeedback versus those who have received conventional therapy.

The results of biofeedback therapy in children are at odds with those in the adult literature. As discussed earlier in this article, several RCTs in adult patients have demonstrated that biofeedback therapy is effective in improving bowel symptoms and in correcting dyssynergic defecation. It is unclear why biofeedback therapy in children is less successful. The absence of clinical improvement after correction of abnormal defecation dynamics, could suggest that dyssynergic defecation plays a less crucial role in the pathophysiology of pediatric constipation or the nature of illness and its natural history is different in children. For example, children may learn to stop withholding more easily or the cognitive skills required for biofeedback to succeed might be more complex and challenging making clinical outcomes less favorable. Thus, based on published evidence, although biofeedback therapy is useful, it does not provide additional benefit over conventional treatment of constipation in most children, either with or without FI (51).

RECOMMENDATION

Biofeedback therapy is not recommended for the routine treatment of children with functional constipation, with or without overflow fecal incontinence. Level 1, Grade D.

Fig 2.

B. The anorectal pressure changes in the same patient (2A) after 4 sessions of biofeedback therapy for fecal incontinence. The patient now demonstrates a coordinated squeeze response with a significant and sustained increase in the anal sphincter pressure, and without any rise in intrarectal pressure.

Acknowledgement

Dr Rao is supported in part by grant RO1DK57100-03, National Institutes of Health. Dr Bharucha is supported by grant RO1DK78924, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Whitehead is supported by grant R21DK096545, National Institutes of Health and R01HS018695 from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.

Dr. Whitehead received a grant from Salix Pharmaceuticals, and he is a member of the board of the Rome Foundation.

Role of Authors: All authors were equally involved in the design, preparation of the manuscript, critical appraisal and final approval. Specifically Dr. S. Rao and Dr. Bharucha critically reviewed and summarized the literature on biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation. Dr. Whitehead, and Dr. Chiarioni reviewed and summarized the literature on fecal incontinence. Dr. Benninga and Dr. Di Lorenzo on pediatric functional constipation and fecal incontinence and Dr. Chiarioni and Dr. Rao on levator ani syndrome and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Dr Rao reports no conflict of interest in the context of this report but has served as a consultant for Forest laboratories, Ironwood pharmaceuticals, Takeda pharmaceuticals, Salix pharmaceuticals and Given imaging. Dr Benninga reports no conflict of interest in the context of this report, but he serves as a consultant for Shire, Sucampo and Johnson and Johnson pharmaceuticals. Dr Bharucha served as a consultant for Uroplasty Inc, Gicare Pharma, Furiex Pharmaceuticals. Dr Chiarioni served as a speaker for Shire Italia S.P.A. Dr. Di Lorenzo reports no conflict of in interest in the context of this report, but he is consultant for QOL, Sucampo Pharmaceuticals and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Wald AB, Bharucha A, Cosman BC, et al. ACG clinical guidelines: management of benign anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.190. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao SS. Current and emerging treatment options for fecal incontinence. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:752–764. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mugie SM, Di LC, Benninga MA. Constipation in childhood. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:502–511. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitehead WE, Rao SS, Lowry A, et al. Treatment of fecal incontinence: State of the Science and directions for future research. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.303. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao SSC, Mudipalli S, Stessman M, et al. Investigation of the utility of colorectal function tests and Rome II criteria in dyssynergic defecation (Anismus) Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:589–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, et al. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1510–1518. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao SSC. Dyssynergic Defecation and biofeedback therapy. In Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:569–586. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao SSC, Welcher K, Pelsang RE. Effects of biofeedback therapy on anorectal function in obstructive defecation. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2197–2205. doi: 10.1023/a:1018846113210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao SSC. The Technical aspects of biofeedback therapy for defecation disorders. The Gastroenterologist. 1998;6:96–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao SS, Seaton K, Miller M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback, sham feedback, and standard therapy for dyssynergic defecation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao SSC, Valestin J, Brown CK, et al. Long term efficacy of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation: randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:890–896. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiarioni G, Salandini L, Whitehead WE. Biofeedback benefits only patients with outlet dysfunction, not patients with isolated slow transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:86–97. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heymen S, Scarlett Y, Jones K, et al. Randomized, controlled trail shows biofeedback to be superior to alternative treatments for patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia-type constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:428–441. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0814-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiarioni G, Whitehead WE, Pezza V, et al. Biofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergia. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:657–664. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koutsomanis D, Lennard-Jones J, Kamm MA. Prospective study of biofeedback treatment for patients with slow and normal transit constipation. Eur J. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;6:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koh CE, Young CJ, Young JM, et al. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the effectiveness of biofeedback for pelvic floor dysfunction. BJS. 2008;95:1079–1087. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shim LSE, Jones M, Prott GM, et al. Predictors of outcome of anorectal biofeedback therapy in patients with constipation. Alim Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1245–1251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao SS, Seaton K, Miller MJ, et al. Psychological profiles and quality of life differ between patients with dyssynergia and those with slow transit constipation. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Go J, Valestin J, Brown C, et al. Is biofeedback therapy effective in improving quality of life in dyssynergic defecation? A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(supplement 5) S-52. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patankar SK, Ferrara A, Levy JR, et al. Biofeedback in colorectal practice: a multicenter, statewide, three-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:827–831. doi: 10.1007/BF02055441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawimbe BM, Pappachrysostomou M, Binnie NR, et al. Outlet obstruction constipation (anismus) managed by biofeedback. Gut. 1991;32:1175–1179. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.10.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao SSC, Valestin J, Brown C, et al. Home or Office Biofeedback Therapy for Dyssynergic Defecation - Randomized control trial. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:S160. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heymen S, Jones KR, Scarlett Y, et al. Biofeedback treatment of constipation: a critical review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1208–1217. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6717-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao SSC, Tantiphlachiva K, Remes-Troche JM, et al. Does biofeedback therapy modulate Anorectal (gut)-brain axis in patients with dyssynergic defecation? Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5) suppl 1:S707–S708. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coss-adame E, Rao S, Remes-Troche JM, et al. Does biofeedback therapy improve brain-gut axis in dyssynergic defecation? Neurogastro Motil. 2012;3(24s2):27. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodward S, Norton C, Chiarelli P. Biofeedback for treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Mar 26;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008486.pub2. CD008486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sangwan YP, Coller JA, Barrett RC, et al. Can manometric parameters predict response to biofeedback therapy in fecal incontinence? Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:1021–1025. doi: 10.1007/BF02133972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiarioni G, Bassotti G, Stegagnini S, et al. Sensory retraining is key to biofeedback therapy for formed stool fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:109–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fynes MM, Marshall K, Cassidy M, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing the effect of augmented biofeedback with sensory biofeedback alone on fecal incontinence after obstetric trauma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:753–758. doi: 10.1007/BF02236930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ilnyckyj A, Fachnie E, Tougas G. A randomized controlled trial comparing an educational intervention alone vs education and biofeedback in the management of faecal incontinence in women. Neurogastroenterol Mot. 2005;17:58–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heymen S, Scarlett YV, Jones KR, et al. Randomized controlled trial shows biofeedback to be superior to pelvic floor exercises for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1730–1737. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b55455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norton C, Chelvanayagam S, Wilson-Barnett J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback for fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solomon MJ, Pager CK, Rex J, et al. Randomised, controlled trial of biofeedback with anal manometry, transanal ultrasound, or pelvic floor retraining with guidance alone in the treatment of mild to moderate fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:703–710. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norton C, Cody JD. Biofeedback and/or sphincter exercises for the treatment of faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002111.pub3. CD002111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozturk R, Niazi S, Stessman M, et al. Long-term outcome and objective changes of anorectal function after biofeedback therapy for fecal incontinence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:667–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heymen S, Pikarsky AJ, Weiss EG, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing four biofeedback techniques for patients with faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2000;2:88–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2000.0136a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naimy N, Lindam AT, Bakka A, et al. Biofeedback vs. electrostimulation in the treatment of postdelivery anal incontinence: A randomized, clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2040–2046. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwandner T, Konig IR, Heimerl T, et al. Triple target treatment (3T) is more effective than biofeedback alone for anal incontinence: the 3T–AI study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1007–1016. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181db7738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartlett L, Sloots K, Nowak M, et al. Biofeedback for fecal incontinence: a randomized study comparing exercise regimens. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:846–856. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182148fef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buser WD, Miner PB, Jr, et al. Delayed rectal sensation with fecal incontinence. Successful treatment using anorectal manometry. Gastroenterology. 1986 Nov;91:1186–1191. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(86)80015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiarioni G, Nardo A, Vantini I, et al. Biofeedback is superior to electrogalvanic stimulation and massage for treatment of levator ani syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1321–1329. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jarrett MED, Emmanuel AV, Vaizey CJ, et al. Behavioural therapy (biofeedback) for solitary rectal ulcer syndrome improves symptoms and mucosal blood flow. Gut. 2004;53:368–370. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.025643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao SSC, Ozturk R, De Ocampo S, et al. Pathophysiology and role of biofeedback therapy in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:613–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morio O, Meurette G, Desfourneaux V, et al. Anorectal physiology in solitary ulcer syndrome: A Case-Matched Series. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1917–1922. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiarioni G, Asteria C, Whitehead WE. Chronic proctalgia and chronic pelvic pain syndromes: New etiologic insights and treatment options. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4447–4455. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i40.4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van den Berg MM, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C. Epidemiology of childhood constipation: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2401–2409. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loening-Baucke V. Biofeedback treatment for chronic constipation and encopresis in childhood: long-term outcome. Pediatrics. 1995;96:105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van der Plas RN, Benninga MA, Büller HA, et al. Biofeedback training in treatment of childhood constipation: a randomised controlled study. Lancet. 1996;348:776–780. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)03206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Voskuijl WP, van Ginkel R, Benninga MA, et al. New insight into rectal function in pediatric defecation disorders: disturbed rectal compliance is an essential mechanism in pediatric constipation. J Pediatr. 2006;148:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tabbers MM, Dilorenzo C, Berger MY, et al. Evaluation and Treatment of Functional Constipation in Infants and Children: Evidence-Based Recommendations From ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58:265–281. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brazzelli M, Griffiths PV, Cody JD, et al. Behavioural and cognitive interventions with or without other treatments for the management of faecal incontinence in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002240.pub4. CD002240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wald A, Chandra, Gabel S, et al. Evaluation of biofeedback in childhood encopresis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:554–558. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198707000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davila E, de Rodriguez GG, Adrianza A, et al. The usefulness of biofeedback in children with encopresis. A preliminary report. G E N. 1992;46:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nolan T, Catto-Smith T, Coffey C, et al. Randomised controlled trial of biofeedback training in persistent encopresis with anismus. Arch Dis Child. 1998;79:131–135. doi: 10.1136/adc.79.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borowitz SM, Cox DJ, Sutphen JL, et al. Treatment of childhood encopresis: a randomized trial comparing three treatment protocols. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;34:378–384. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sunić-Omejc M, Mihanović M, Bilić A, et al. Efficiency of biofeedback therapy for chronic constipation in children. Coll Antropol. 2002;26(Suppl):93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pijpers MAM, Bongers MEJ, Benninga MA, et al. Functional constipation in children: a systematic review on prognosis and predictive factors. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:256–268. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181afcdc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van den Berg M, van Rossum C, de Lorijn F, et al. Functional constipation in infants: a follow-up study. J Pediatr. 2005;147:700–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]