Abstract

Background

Several single center studies have reported excellent outcomes with minimally invasive aortic valve replacement (mini-AVR). Although criticized as requiring more operative time and complexity, mini-AVR is increasingly performed. We compared contemporary outcomes and cost of mini-AVR versus conventional AVR in a multi-institutional regional cohort. We hypothesize that mini-AVR provides equivalent outcomes to conventional AVR without increased cost.

Methods

Patient records for primary isolated AVR (2011–2013) were extracted from a regional, multi-institutional Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database and stratified by conventional versus mini-AVR, performed by either partial sternotomy or right thoracotomy. To compare similar patients, a 1:1 propensity match cohort was performed after adjusting for surgeon, operative year, and STS risk score including age and risk factors (n=289 in each group). Differences in outcomes and cost were analyzed.

Results

A total of 1,341 patients underwent primary isolated AVR, of which 442 (33%) underwent mini-AVR at 17 hospitals. Mortality, stroke, renal failure and other major complications were equivalent between groups. Mini-AVR was associated with decreased ventilator time (5 vs 6 hours; p=0.04) and decreased blood product transfusion (25% vs 32%; p=0.04). A greater percentage of mini-AVR patients were discharged within 4 days of the operation (15.2% vs 4.8%; p<0.001). Consequently, total hospital costs were lower in the mini-AVR group ($36,348 vs $38,239; p=0.02).

Conclusions

Mortality and morbidity outcomes of mini-AVR are equivalent to conventional AVR. Mini-AVR is associated with decreased ventilator time, blood product utilization, early discharge, and reduced total hospital cost. In contemporary clinical practice, mini-AVR is safe and cost-effective.

INTRODUCTION

Aortic valve replacement (AVR) via a full sternotomy has long been the standard approach to treat aortic valve pathology and can be performed with minimal morbidity and mortality.1 Introduced in the 1990s, minimally invasive aortic valve replacement (mini-AVR), performed via a partial upper sternotomy or right thoracotomy, is increasingly performed at cardiac surgery centers across the United States.2 Several groups have demonstrated that mini-AVR can be performed with excellent outcomes, less patient discomfort, decreased blood product transfusion, and reduced length of stay compared to conventional AVR.3–7 Mini-AVR, however, has been criticized for increased cardiopulmonary bypass, cross-clamp, and operating room time, and higher cost.8, 9 As partial-sternotomy or thoracotomy provides limited exposure to the heart, myocardial protection, deairing, and valve exposure can be more challenging.10 Previous published studies on mini-AVR have been limited to single high-volume centers. The contemporary outcomes of mini-AVR as it has disseminated to centers with more diverse volume and experience is unknown. Furthermore, no previous study has evaluated outcomes and cost of mini-AVR in a multi-institutional cohort.

In this study, we compare contemporary mini-AVR and conventional AVR outcomes and cost in a multi-institutional regional cohort. We hypothesize that mini-AVR provides equivalent outcomes to conventional AVR without increased cost.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The Virginia Cardiac Surgery Quality Initiative (VCSQI) is a voluntary group of 17 hospitals and 13 cardiac surgical practices providing cardiac surgery in the Commonwealth of Virginia. VCSQI members perform over 99% of Commonwealth’s cardiac surgery procedures. The VCSQI data registry is a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) certified database (version 2.73). This investigation was exempt from formal Institutional Review Board review at each participating center as it represents a secondary analysis of the VCSQI data registry with the absence of Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act patient identifiers and because the data are collected for quality analysis and purposes other than research.

Patients and Data Acquisition

Starting in 2011, operative approach for AVR was recorded within the VCSQI database, allowing for identification of minimally invasive procedures (STS v2.73). De-identified patient records for all patients who underwent isolated primary AVR for the study period of January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2013 were obtained from the VCSQI registry. Exclusion criteria included endocarditis, reoperative status, and any other concomitant surgical procedure. Patient records were then stratified by operative approach: full sternotomy, partial-sternotomy, or right thoracotomy. Full sternotomy patients were placed in the conventional AVR group. Partial sternotomy and right thoracotomy patients were combined into the mini-AVR group. Patient preoperative, operative, and postoperative variables were retrieved from the VCQI database for each patient. STS predicted risk of morbidity and mortality (PROMM) and predicted risk of mortality (PROM) were individually calculated.

Cost Data and Acquisition

The VCSQI data registry combines standardized clinical data extracted from the STS data entry forms with hospital inpatient discharge financial data. Hospital inpatient data from UB-92 and UB-04 files are matched with each STS patient record. By the use of center-specific cost-to-charge ratios, estimated hospital costs are determined with previously described methods.11, 12 VCSQI maintains a 99% matching rate between STS patient records and billing data.

Measured Outcomes

The primary outcomes were frequency of postoperative complications, length of stay (LOS), operative mortality, and hospital cost. Operative mortality was defined as all patient deaths occurring during hospitalization as well as those within 30 days of the date of surgery despite discharge status. Ventilation time, intensive care unit (ICU) hours, and hospital LOS from surgery to discharge were measured. Early discharge was defined as discharge by the 4th postoperative day. Standard STS definitions for postoperative events and complications were utilized, including cerebrovascular accident (CVA), renal failure (increase in serum creatinine level >2.0 or doubling of the most recent preoperative creatinine), prolonged ventilation (>24 hours of mechanical ventilation), presence of any new onset atrial fibrillation, deep sternal wound infection, and administration of intraoperative or postoperative blood product.11

Statistical Analysis

All study group comparisons were unpaired. Categorical variables were compared using either Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, and continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test for normally distributed data or the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for non-normally distributed data where appropriate. Propensity score matching was performed to generate a study cohort of matched conventional AVR and mini-AVR patients adjusted for potential confounding. Propensity scores were estimated using binary logistic regression models with performance of mini-AVR as the response variable and STS PROM, operative year, and operating surgeon as possible confounding predictor variables. Propensity scores were then used to match conventional AVR and mini-AVR patients in a 1:1 ratio using nearest neighbor greedy methodology, resulting in equal size study cohorts. Postoperative outcomes were then compared between matched groups using standard univariate statistical tests of association.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

In our regional cohort, a total of 1,341 patients underwent isolated AVR during the study period, of which 442 (33%) underwent mini-AVR at 17 hospitals. Patient characteristics for the overall cohort are reported in Table 1 and grouped by surgical approach. Mini-AVR patients were older (74 vs 69 yrs; p<0.001) and had a greater incidence of peripheral vascular disease (12.7% vs 8.0%; p<0.001) and end stage renal disease (3.6% vs 1.3%; p<0.01). In the unmatched cohort, conventional AVR patients had a higher STS PROM (1.8% vs 1.3%; p<0.001) and STS PROMM (14.2% vs 11.8%; p<0.001). Moderate or severe aortic insufficiency (AI), which some groups use as a relative contraindication for mini-AVR, was present in 26.2% (n=116) of mini-AVR patients. There were no statistically significant differences in other comorbidities such as hypertension, COPD, diabetes, or heart failure between the 2 unmatched groups. The patient characteristics of the propensity score matched groups are shown in Table 2. After 1:1 matching by surgeon, operative year, and STS PROM, conventional AVR and mini-AVR patients shared similar preoperative comorbidities. The groups had equivalent STS PROM and PROMM.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics for Overall Unmatched Cohort

| Characteristic | Conventional AVR (n = 899)

|

Mini-AVR (n = 442)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age | 69 (60,77) | 74 (63, 83) | <0.01 | ||

| Female Gender | 378 | 42.0 | 201 | 45.5 | 0.233 |

| BSA | 2.0 (1.9, 2.3) | 2.0 (1.8, 2.2) | <0.01 | ||

| Hypertension | 713 | 79.3 | 348 | 78.7 | 0.81 |

| Diabetes | 299 | 33.3 | 132 | 29.9 | 0.06 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 72 | 8.0 | 56 | 12.7 | <0.01 |

| End Stage Renal Disease | 12 | 1.3 | 16 | 3.6 | <0.01 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 242 | 26.9 | 139 | 31.4 | 0.06 |

| Mild | 137 | 15.2 | 65 | 14.7 | |

| Moderate | 60 | 6.7 | 35 | 7.9 | |

| Severe | 45 | 5.0 | 39 | 8.8 | |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 368 | 40.9 | 192 | 43.4 | 0.29 |

| NYHA I | 15 | 1.7 | 9 | 2.0 | |

| NYHA II | 137 | 15.2 | 58 | 13.1 | |

| NYHA III | 153 | 17.0 | 81 | 18.3 | |

| NYHA III | 53 | 7.0 | 44 | 10.0 | |

| LV EF (%) | 60 (53, 63) | 60 (55, 64) | 0.72 | ||

| Moderate or Severe AI | 246 | 27.4 | 116 | 26.2 | 0.79 |

| STS PROMM (%) | 14.2 (10.1, 20.0) | 11.8 (9.0, 17.1) | <0.01 | ||

| STS PROM (%) | 1.8 (1.0, 3.1) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.3) | <0.01 | ||

BSA, Body Surface Area. NYHA, New York Heart Association. AI, Aortic Insufficiency. STS PROMM, Society of Thoracic Surgery Predicted Risk of Morbidity or Mortality. STS PROM, Society of Thoracic Surgery Predicted Risk of Mortality. All continuous variables are presented as median and 25% and 75% percentiles.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics for Propensity Score Matched Cohort

| Characteristic | Conventional AVR (n = 289)

|

Mini-AVR (n = 289)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age | 67 (58,74) | 67 (60,76) | 0.36 | ||

| Female Gender | 110 | 38.1 | 103 | 35.6 | 0.55 |

| BSA | 2.1 (1.9, 2.3) | 2.0 (1.9, 2.2) | 0.41 | ||

| Hypertension | 225 | 77.9 | 215 | 74.4 | 0.33 |

| Diabetes | 93 | 32.2 | 76 | 26.3 | 0.12 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 22 | 7.6 | 25 | 8.7 | 0.65 |

| End Stage Renal Disease | 7 | 2.4 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.20 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 67 | 23.2 | 65 | 22.5 | 0.57 |

| Mild | 42 | 14.5 | 33 | 11.4 | |

| Moderate | 15 | 5.2 | 18 | 6.2 | |

| Severe | 10 | 3.5 | 14 | 4.8 | |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 196 | 67.8 | 201 | 69.6 | 0.31 |

| NYHA I | 5 | 1.7 | 5 | 1.7 | |

| NYHA II | 35 | 12.1 | 35 | 12.1 | |

| NYHA III | 37 | 12.8 | 41 | 14.2 | |

| NYHA III | 16 | 5.5 | 6 | 2.1 | |

| LV EF (%) | 60 (53, 64) | 60 (55, 65) | 0.71 | ||

| Moderate or Severe AI | 87 | 30.1 | 85 | 29.4 | 0.23 |

| STS PROMM (%) | 12.5 (9.4, 16.9) | 11.8 (9.0, 17.5) | 0.34 | ||

| STS PROM (%) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.4) | 1.4 (0.8, 2.3) | 0.31 | ||

BSA, Body Surface Area. NYHA, New York Heart Association. AI, Aortic Insufficiency. STS PROMM, Society of Thoracic Surgery Predicted Risk of Morbidity or Mortality. STS PROM, Society of Thoracic Surgery Predicted Risk of Mortality. All continuous variables are presented as median and 25% and 75% percentiles.

Operative Characteristics

Mini-AVR was performed via a partial sternotomy (n=410; 93%) or right thoracotomy (n=32; 7%). Median cardiopulmonary bypass time (104 vs 103 min; p=0.64) and ischemic time (75 vs 73 min; p=0.61) was equivalent between the two groups. Central arterial and venous cannulation was the preferred perfusion technique in the majority of cases (n=311; 70%). Femoral venous cannulation was performed in 131 (30%) patients and femoral arterial cannulation was performed in 78 (18%) patients.

Outcomes of Matched Cohorts

Operative morbidity, mortality, and length of stay are reported in Table 3 and stratified by surgical approach for propensity matched patients. Operative mortality was equivalent between the 2 groups (0.3% mini-AVR vs 2.1% AVR; p=0.06). There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of postoperative stroke (1.0% mini-AVR vs 2.1% AVR; p=0.37), renal failure (1.0% mini-AVR vs 0.7% AVR; p=0.66), atrial fibrillation (32.2% mini-AVR vs 28.4% AVR; p=0.6), reoperation for bleeding (5.2% mini-AVR vs 2.1% AVR; p=0.12), or respiratory insufficiency (9.0% mini AVR vs 8.7% AVR; p=0.69). Ventilator time was lower in mini-AVR patients (5 vs 6 hours; p=0.04) There was no significant difference in ICU LOS (43 vs 45 hrs; p=0.08), or hospital LOS (5.0 vs 6.0 days; p=0.10) between the 2 groups. Early discharge (defined by discharge by the 4th postoperative day) was more common in Mini-AVR patients (15.8% vs 4.2%; p<0.01)

Table 3.

Operative Outcomes in Propensity Matched Patients

| Outcome | Conventional AVR (n = 289)

|

Mini-AVR (n = 289)

|

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Death | 6 | 2.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.06 |

| Stroke | 6 | 2.1 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.37 |

| Renal Failure | 2 | 0.7 | 3 | 1.0 | 0.66 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 82 | 28.4 | 93 | 32.2 | 0.60 |

| Reop for Bleed | 6 | 2.1 | 15 | 5.2 | 0.12 |

| Blood Product Transfusion | 92 | 31.8 | 71 | 24.6 | 0.05 |

| Respiratory Insufficiency | 25 | 8.7 | 26 | 9.0 | 0.69 |

| Ventilator Time (hours) | 6 (4, 13) | 5 (4, 11) | 0.04 | ||

| ICU LOS (hours) | 45 (26, 75) | 43 (24, 75) | 0.08 | ||

| Hospital LOS (days) | 6 (5, 8) | 5 (4, 8) | 0.10 | ||

| Discharged by POD#4 | 14 | 4.8 | 44 | 15.2 | <0.01 |

ICU, Intensive Care Unit. LOS, Length of Stay. POD, Postoperative Day. All continuous variables are presented as median and 25% and 75% percentiles.

Blood Product Transfusion

In matched patients, fewer mini-AVR patients received a blood product transfusion compared to conventional AVR (24.6% vs 31.8%; p=0.05). Mini-AVR received 47% fewer units of blood on average (0.28 vs 0.53 units packed red blood cells; p=0.008).

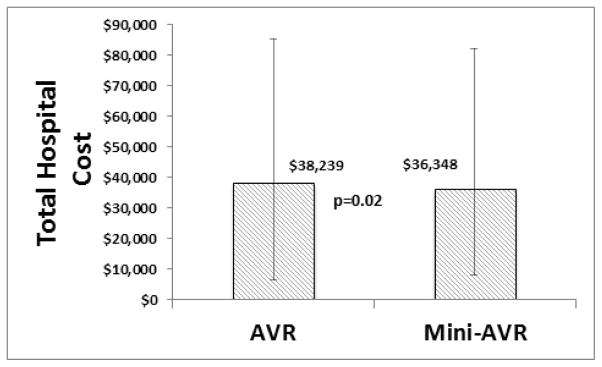

Cost

Hospital cost data for the matched groups is reported in Figure 1. Total hospital cost was lower in the mini-AVR group ($36,348 vs $38,239; p=0.02).

Figure 1. Hospital Costs for Propensity Matched Patients.

Median total hospital cost was $1,891 (p=0.02) lower in mini-AVR compared to conventional AVR.

COMMENT

Minimally invasive aortic valve surgery is increasingly desired by patients. The appeal of minimally invasive surgery is clear given its improved cosmesis, potential for less pain and quicker recovery.5 Minimally invasive operations may be especially beneficial for specific subgroups, such as the elderly or patients with significant respiratory disease.13 Concerns however that less invasive surgery is associated greater operative complexity with longer crossclamp and bypass times are appropriate, particularly if this leads to increased morbidity and mortality. Poorer outcomes obviate any perceived benefit of less invasive operations.

In this study, we compared operative outcomes and cost of mini-AVR versus conventional AVR in a multi-institutional regional cohort. Unlike prior studies from single high volume centers, this study evaluates the outcomes from 17 institutions—allowing a “realworld” and contemporary analysis. Mini-AVR was associated with equivalent cardiopulmonary bypass time and cross-clamp time. In propensity matched patients, there was no difference in mortality, stroke, renal failure, and other major morbidities between mini-AVR and conventional AVR. There was a notable trend in reduced operative mortality with mini-AVR in propensity matched patients (0.3% vs 2.1%; p=0.06). Mini-AVR was found to have reduced ventilator time and more frequent early discharge. Moreover, mini-AVR patients were also significantly less likely to receive a transfusion. Although criticized as being more costly, mini-AVR cost was less than conventional AVR, primarily due to more frequent early discharge and less blood product utilization.

Previous studies have also uniformly found longer crossclamp and bypass times with mini-AVR. 3, 14, 15 The clinical significance of this however is unclear, as these same studies identified no associated increase in morbidity or mortality. In our study, we found that cross-clamp and bypass times were equal in full sternotomy and mini-AVR, suggesting that surgeons have now adopted techniques to reduce bypass and cross-clamp times with mini-AVR. Mini-AVR cross-clamp times are now similar to national STS data for AVR. There are, however, scenarios where minimally invasive surgery will inevitably increase operative times compared to conventional surgery. Given this, new surgeons and centers embarking on minimally invasive surgery should devise a strategy to optimize myocardial protection. New technology, such as endovascular pulmonary artery vents and cardioplegia catheters have been developed to improve myocardial protection during mini-AVR should be considered in a minimally invasive surgeon’s armamentarium. 15

Consistent with national STS trends, overall operative mortality with AVR in our regional cohort was low with an observed mortality of 1.2%.1 This corresponded to an observed to expected mortality ratio of 0.84. Prior studies comparing mini-AVR to full sternotomy AVR have also found equivalent operative mortality rates. Mihaljevik and colleagues found an operative mortality of 2% in mini-AVR versus 3% in conventional AVR in 526 patients who underwent AVR at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.3 Johnston and colleagues found an identical 0.96% operative mortality in 832 propensity matched patients at the Cleveland Clinic.5 Brown and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 26 studies and 4,586 patients undergoing mini-AVR versus conventional AVR. 14 They found no difference in operative mortality (odds ratio 0.71 [0.49, 1.02]).

Corresponding with prior studies, there was no significant difference in major morbidity (stroke, renal failure, etc.) between mini-AVR and conventional AVR. Similar to previous studies, mini-AVR decreased median ventilator time by 17% (1 hour). Johnston and colleagues reported a median ventilator time of 5.2 hours for mini-AVR versus 6.9 hours for conventional AVR.5 Many high-volume minimally invasive valve centers perform early extubation in the operating room. Such strategies may reduce ventilator times and LOS and further widen the difference between mini- and conventional AVR.16 Mirroring national STS trends, postoperative LOS is decreasing after AVR. In 2006, median postoperative LOS was 7.06 days. By comparison, in this study postoperative LOS has decreased to 5 days (mini-AVR) and 6 days (conventional AVR). Although median ICU and hospital LOS were statistically equivalent, mini-AVR patients were 3 times more frequently discharged by the 4th postoperative day. Earlier discharge provides a potential opportunity for improved resource utilization and patient satisfaction.

As noted in prior studies, mini-AVR is associated with decreased blood product utilization.3, 5, 7, 17–19 Twenty five percent of mini-AVR patients received blood products compared to 32% for conventional AVR, with mini-AVR patients receiving 47% fewer units of packed red blood cells on average. Numerous studies have indicated that transfusion is associated with worse short and long term outcomes following cardiac surgery.20, 21 Reduced transfusion reduces resource utilization and may provide benefits beyond in-hospital outcomes.11

Few studies have evaluated cost of mini-AVR, which has been criticized as more expensive due to longer operative times and need for specialized equipment. In this study, we found that total hospital costs were 5% lower in patients who underwent mini-AVR compared to conventional AVR. The primary reason for lower total costs were more frequent early discharge and lower blood product utilization. Prior single center studies have reported decreased cost with mini-AVR. Cohn and colleagues reported that mini-AVR reduced hospital charges by $7,000.22 Cosgrove and colleagues reported that mini-AVR reduced hospital direct costs by 19%. 23

Most prior studies have been limited to a single center’s experience with mini-AVR. In this study, mini-AVR was performed at 17 hospitals. We believe the results of this study are more reflective of contemporary clinical practice. Mini-AVR represented 33% of total isolated aortic valve replacement volume in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The median operative volume was 4.5 cases per hospital over the 3 year study period. The results of this study indicate that equivalent outcomes to conventional AVR can be obtained at centers with diverse experience and volume.

This study does have some important limitations. This study is a retrospective analysis. We do not know the selection criteria that individual surgeons utilized to select patients for mini-AVR. We utilized propensity-score matching to create similar AVR and mini-AVR cohorts for comparison. We intentionally limited our propensity matching variables to the STS PROM score, surgeon, and operative year to avoid overestimation with modeling. Although utilizing this technique 35% of mini-AVR patients were unmatched and thus not included for comparison, we were able to identify sizeable, well-matched cohorts. We included both partial sternotomy and right thoracotomy approaches for mini-AVR, as we wanted to include all “real world” minimally invasive approaches in this analysis. As the right thoracotomy approach was limited to a small number of patients, the outcomes of this study are unaffected by their inclusion. Comparison of partial sternotomy and right thoracotomy would be an important future study; however we did not have adequate sample size for this analysis in this cohort. Important outcome data such as postoperative pain, patient satisfaction, and return to work were also not captured in our database. These are the primary rationale to perform mini-AVR and others have demonstrated superiority to conventional AVR.22, 24 Cost data was limited to in-hospital costs. Additional factors, such as rehabilitation cost and lost productivity were not included in the cost analysis. Including these health-care costs may have increased overall savings with mini-AVR compared to conventional AVR.

In summary, the outcomes of mini-AVR are equivalent to conventional AVR in a contemporary multi-institutional analysis. Mini-AVR is associated with decreased ventilator time, blood product utilization, early discharge, and reduced total hospital cost. In contemporary clinical practice, mini-AVR is safe and cost-effective.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Department of Surgery, University of Virginia

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflict of interest that would impact this study’s design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brown JM, O’Brien SM, Wu C, Sikora JA, Griffith BP, Gammie JS. Isolated aortic valve replacement in North America comprising 108,687 patients in 10 years: changes in risks, valve types, and outcomes in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2009;137:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosgrove DM, 3rd, Sabik JF. Minimally invasive approach for aortic valve operations. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1996;62:596–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mihaljevic T, Cohn LH, Unic D, Aranki SF, Couper GS, Byrne JG. One thousand minimally invasive valve operations: early and late results. Annals of surgery. 2004;240:529–34. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000137141.55267.47. discussion 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabata M, Umakanthan R, Cohn LH, Bolman RM, 3rd, Shekar PS, Chen FY, et al. Early and late outcomes of 1000 minimally invasive aortic valve operations. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2008;33:537–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston DR, Atik FA, Rajeswaran J, Blackstone EH, Nowicki ER, Sabik JF, 3rd, et al. Outcomes of less invasive J-incision approach to aortic valve surgery. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012;144:852–8. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, Sidiropoulos A, Konertz W. Minimally invasive aortic valve replacement (AVR) compared to standard AVR. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 1999;16 (Suppl 2):S80–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonacchi M, Prifti E, Giunti G, Frati G, Sani G. Does ministernotomy improve postoperative outcome in aortic valve operation? A prospective randomized study. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2002;73:460–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03402-6. discussion 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooley DA. Antagonist’s view of minimally invasive heart valve surgery. Journal of cardiac surgery. 2000;15:3–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2000.tb00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham MJ, Berberian CE, Starnes VA. Is transthoracic minimally invasive aortic valve replacement too time-consuming for the busy cardiac surgeon? Innovations. 2011;6:10–4. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0b013e31820bc462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabata M, Umakanthan R, Khalpey Z, Aranki SF, Couper GS, Cohn LH, et al. Conversion to full sternotomy during minimal-access cardiac surgery: reasons and results during a 9.5-year experience. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2007;134:165–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LaPar DJ, Crosby IK, Ailawadi G, Ad N, Choi E, Spiess BD, et al. Blood product conservation is associated with improved outcomes and reduced costs after cardiac surgery. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2013;145:796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.041. discussion -4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Speir AM, Kasirajan V, Barnett SD, Fonner E., Jr Additive costs of postoperative complications for isolated coronary artery bypass grafting patients in Virginia. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2009;88:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.03.076. discussion 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ElBardissi AW, Shekar P, Couper GS, Cohn LH. Minimally invasive aortic valve replacement in octogenarian, high-risk, transcatheter aortic valve implantation candidates. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2011;141:328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown ML, McKellar SH, Sundt TM, Schaff HV. Ministernotomy versus conventional sternotomy for aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2009;137:670–9. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinkman WT, Hoffman W, Dewey TM, Culica D, Prince SL, Herbert MA, et al. Aortic valve replacement surgery: comparison of outcomes in matched sternotomy and PORT ACCESS groups. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2010;90:131–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu F, Lee A, Chee YE. Fast-track cardiac care for adult cardiac surgical patients. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012;10:CD003587. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003587.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bakir I, Casselman FP, Wellens F, Jeanmart H, De Geest R, Degrieck I, et al. Minimally invasive versus standard approach aortic valve replacement: a study in 506 patients. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2006;81:1599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dogan S, Dzemali O, Wimmer-Greinecker G, Derra P, Doss M, Khan MF, et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional aortic valve replacement: a prospective randomized trial. The Journal of heart valve disease. 2003;12:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machler HE, Bergmann P, Anelli-Monti M, Dacar D, Rehak P, Knez I, et al. Minimally invasive versus conventional aortic valve operations: a prospective study in 120 patients. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1999;67:1001–5. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy GJ, Reeves BC, Rogers CA, Rizvi SI, Culliford L, Angelini GD. Increased mortality, postoperative morbidity, and cost after red blood cell transfusion in patients having cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:2544–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.698977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Galas FR, Nakamura RE, Silva CM, Santos MH, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:1559–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohn LH, Adams DH, Couper GS, Bichell DP, Rosborough DM, Sears SP, et al. Minimally invasive cardiac valve surgery improves patient satisfaction while reducing costs of cardiac valve replacement and repair. Annals of surgery. 1997;226:421–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199710000-00003. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cosgrove DM, 3rd, Sabik JF, Navia JL. Minimally invasive valve operations. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1998;65:1535–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00300-2. discussion 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Candaele S, Herijgers P, Demeyere R, Flameng W, Evers G. Chest pain after partial upper versus complete sternotomy for aortic valve surgery. Acta cardiologica. 2003;58:17–21. doi: 10.2143/AC.58.1.2005254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]