Abstract

Purpose

Few computer-based HIV, sexually transmitted infection (STI), and pregnancy prevention programs are available, and even fewer target early adolescents. In this study, we tested the efficacy of It’s Your Game (IYG)-Tech, a completely computer-based, middle school sexual health education program. The primary hypothesis was that students who received IYG-Tech would significantly delay sexual initiation by ninth grade.

Methods

We evaluated IYG-Tech using a randomized, two-arm nested design among 19 schools in a large, urban school district in southeast Texas (20 schools were originally randomized). The target population was English-speaking eighth-grade students who were followed into the ninth grade. The final analytic sample included 1,374 students. Multilevel logistic regression models were used to test for differences in sexual initiation between intervention and control students, while adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity, time between measures, and family structure.

Results

There was no significant difference in the delay of sexual activity or in any other sexual behavior between intervention and control students. However, there were significant positive between-group differences for psychosocial variables related to STI and condom knowledge, attitudes about abstinence, condom use self-efficacy, and perceived norms about sex. Post-hoc analyses conducted among intervention students revealed some significant associations: “full exposure” (completion of all 13 lessons) and “mid-exposure” (5–8 lessons) students were less likely than “low exposure” (1–4 lessons) students to initiate sex.

Conclusions

Collectively, our findings indicate that IYG-Tech impacts some determinants of sexual behavior, and that additional efficacy evaluation with full intervention exposure may be warranted.

Keywords: sexual health, teen pregnancy, HIV, sexually transmitted infections, prevention, technology, adolescents

In the United States, despite substantial improvements in adolescent sexual health, youth, especially racial/ethnic minorities, continue to bear a significant proportion of the burden of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unplanned pregnancies [1, 2]. The ubiquitous appeal and availability of technology among youth offers the possibility of its application to adolescent sexual health education programs [3, 4]. Specifically, technology has the potential to increase the fidelity and reduce the implementation costs of sexual health programs aimed at preventing STIs/HIV and unplanned pregnancies among youth [5, 6].

Technology-based sexual health programs are available and have been found to be effective in increasing abstinence and condom use [7–12]; however, most of these programs do not target early adolescents, almost one-third of whom initiate sex by the time they are in the ninth grade [13]. To our knowledge, only one completely computer-based sexual health intervention has been developed specifically for middle school–aged youth, Keeping It Safe [14]. Evaluation revealed that Keeping It Safe improved HIV/AIDS–related knowledge and risk reduction self-efficacy, but these findings are limited because only short-term effects were measured and only early adolescent females were targeted. Thus, there is a need for effective computer-based sexual health programs that target behavioral and psychosocial outcomes among early adolescent males as well as females.

To capitalize on the promise of technology for sexual health education, we adapted the It’s Your Game…Keep It Real! (IYG) program into a completely computer-based program, IYG-Tech. IYG is a classroom and computer-based sexual health education intervention designed specifically for middle school students, which is theoretically grounded in social cognitive behavioral theories [15]. Evaluation in two randomized controlled trials revealed that IYG significantly delays sexual initiation among sexually inexperienced students [16, 17]. To develop IYG-Tech, we used Intervention Mapping (IM) [18] to assess existing IYG intervention planning matrices and to guide curriculum adaptation to a completely computer-based curriculum [19]. Our usability study of IYG-Tech found that most students liked the program (>70%) and perceived the program as credible, understandable, and just as much fun (if not more so) than other health lessons (>80%) [19]. In the present study, we examined the behavioral (delay in sexual initiation and reduction of sexual risk behavior) and psychosocial effects of IYG-Tech. The primary hypothesis was that students who received IYG-Tech would significantly delay sexual initiation by ninth grade, compared with students who did not receive IYG-Tech.

Methods

Study design and participants

We evaluated IYG-Tech using a randomized, two-arm nested design in a large, urban school district in southeast Texas. We randomized 10 schools to the intervention condition (IYG-Tech) and 10 schools to the control condition (state-approved health education usually from a textbook, without any exposure to a structured health education program). After randomization, one intervention school was dropped because of changes in its administration, which prevented us from conducting timely recruitment. Randomization was conducted using a multi-attribute randomization protocol that accounted for school size, geographic region, racial/ethnic distribution, and teen birth rate for the school’s zip code [20]. Most students were economically disadvantaged, as determined by the percentage of students in the school who received free/reduced lunch. Each school and a school contact (for each school) received $200 and $100, respectively, for participating in the study.

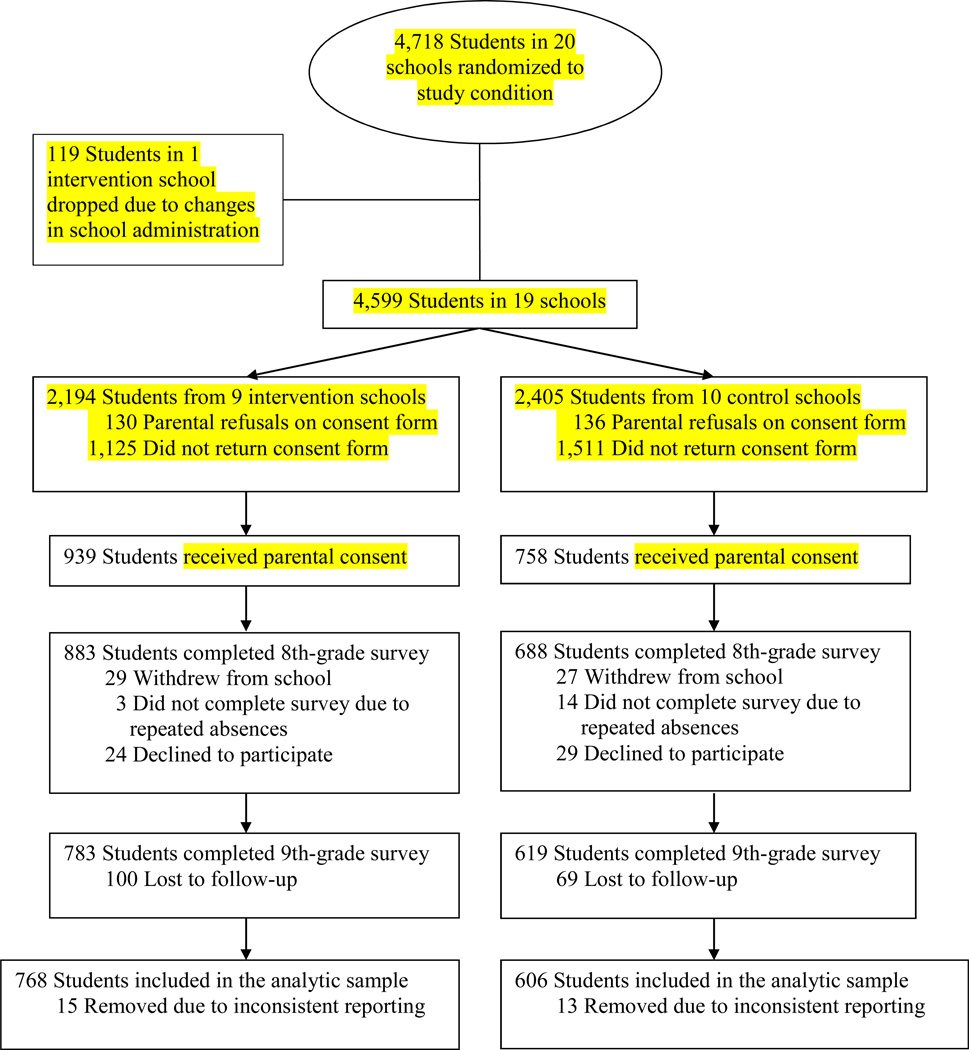

We recruited eighth-grade students who spoke English from classes that all students were required to attend, such as homeroom, physical education, health, or science. Students who returned a parental permission form received a $5 incentive. Affirmative parental permission was obtained by 1,697 students in 2010–2011 (Figure). Of students with parental consent, 92.6% (n = 1,571) provided assent and completed the baseline survey in eighth grade, for which they received a $5 incentive. Students were blinded to condition prior to the baseline assessment. Of students who completed the baseline survey, almost 90% (n = 1,402) completed the 1-year follow-up survey in ninth grade, for which they received a $10 incentive. Students in the follow-up sample were more likely to be Hispanic and less likely to report sexual behavior than students lost to follow-up. Attrition across the conditions was non-differential. Because of inconsistent reporting in outcomes across time, 28 students were excluded from the analysis, leaving a final analytic sample of 1,374. This study was approved by the University of Texas institutional review board and the school district’s Office of Research and Accountability.

Figure.

Flow of participants through the study.

Intervention

The IYG-Tech curriculum comprises 13 lessons, each approximately 35–45 minutes in length. The curriculum is set within a mall-like environment that includes several “storefronts” and “proprietors.” Within the environment, students are guided by two animated narrators who introduce selected activities. Activities include animated scenarios with modeling and skills practice, peer modeling videos (“teens talk”), quizzes, fact sheets, a graffiti wall for personalization and reflection, and “point of view” virtual role-play activities that simulate student skills practice in real-world situations.

IYG-Tech integrates the same life-skills paradigm (Select, Detect, Protect) that is presented in the original IYG program [16, 17]. This paradigm teaches youth to select their personal rules (or limits) regarding their behaviors (sexual and non-sexual) ahead of time, detect signs and situations that could challenge their rules, and protect their rules with refusal skills (use a clear no or alternative actions). Other topics covered in the IYG-Tech curriculum include the characteristics of healthy and unhealthy friendships and dating relationships; anatomy and reproduction; social, emotional, and physical consequences of sex; communication skills; Internet communication and safety; consequences of teen pregnancy and STIs; knowledge and skills for condom and contraception use; and condom negotiation. Details about the development of IYG-Tech, including the adaptation process, are available elsewhere [19].

IYG-Tech was delivered in the school setting. Briefly, IYG-Tech was loaded directly onto individual laptop computers, which were brought into the schools and provided to each student during the sessions. Students who had permission to receive IYG-Tech were pulled from their classes and brought to one location in each school to complete the lessons.

Data collection

Student self-reported data were collected using an audio–computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) on laptop computers at baseline (eighth grade) and 1-year follow-up (ninth grade). Data collection was primarily conducted in schools during regular class time. When it was not feasible in school, data collection was conducted at the student’s home, library, or another location. Standardized data collection procedures were implemented in all survey sites by trained data collectors.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was delayed initiation of any sexual activity in the ninth grade among students who were sexually inexperienced at baseline (eighth grade). This measure was a composite variable of three questions that assessed participation in oral, vaginal, or anal sex. Oral sex was defined as “when someone puts his or her mouth on their partner’s penis, vagina, or anus (that means their butt) or lets their partner put his or her mouth on their penis, vagina, or anus.” Vaginal sex was defined as “when a boy puts his penis inside a girl’s vagina. Some people call this ‘making love’ or ‘doing it.’” Anal sex was defined as “when a boy puts his penis in his partner’s anus (which means butt).”

Secondary outcome measures

Sexual behaviors

Several additional sexual behaviors were assessed: (1) delayed initiation of specific types of sexual activity, (2) number of lifetime sexual partners, (3) current sexual activity (defined as sexual activity in the past 3 months), (4) number of occasions students had sex without a condom, (5) number of partners in the past 3 months, (6) number of partners without a condom in the past 3 months, and (7) use of a condom during last sex. All these measures have been extensively pilot-tested and used among multi-ethnic, urban-dwelling, public school student populations [16, 17, 21, 22].

Psychosocial measures

Determinants of sexual behavior (i.e., psychosocial factors) based on social cognitive behavioral theories [15] were also assessed. Individual factors included (1) knowledge of STIs and condoms; (2) beliefs towards abstinence and condoms; (3) beliefs about friends’ attitudes towards abstinence; (4) perceived norms regarding peer sexual behavior; (5) self-efficacy for refusing sex and using condoms; (6) intentions to have sex, remain abstinent, and use condoms; (7) reasons for not having sex; (8) global character attributes; (9) future orientation; and (10) number of personal limits. Environmental factors included (1) exposure to risky situations that might lead to sex and (2) parental communication about sex. All these measures have been extensively pilot-tested [22–25]. Additional information about each measure (i.e., number of items, range of scores, and Cronbach’s alpha) is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Intervention effects on psychosocial outcomes by ninth grade among the analytic samplea

| Outcomeb | No. of items, range of scores, [Cronbach’s alpha]c |

Sample sized |

Beta (Difference in adjusted mean) |

SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beliefs about abstinence | 4; 0–3 [.77] | 1,323 | .07 | .04 | .00 | .14 |

| Beliefs about waiting to have sex until marriage | 3; 0–3 [.72] | 1,315 | .08* | .03 | .01 | .14 |

| Friends’ beliefs about abstinence | 4; 0–3 [.78] | 1,315 | .09* | .04 | .01 | .16 |

| Perceptions of friends’ behavior | 5; 0–4 [.80] | 1,281 | –.05 | .04 | –.12 | .03 |

| Reasons against having sex | 10; 0–10 [.75] | 1,336 | .27 | .18 | –.09 | .63 |

| Refusal self-efficacy | 7; 1–4 [.86] | 1,293 | .00 | .03 | –.06 | .06 |

| Condom knowledge, % correct | 6; 0–1 [.64] | 1,325 | .07** | .01 | .05 | .10 |

| Condom beliefs | 3; 0–3 [.86] | 1,327 | .06 | .03 | .00 | .12 |

| Condom negotiation self-efficacy | 2; 1–3 [.62] | 1,329 | –.01 | .02 | –.05 | .03 |

| Condom use self-efficacy | 3; 1–3 [.65] | 1,311 | .09** | .03 | .02 | .16 |

| Global character | 5; 0–4 [.78] | 1,320 | .05 | .04 | –.03 | .13 |

| Exposure to risky situations | 7; 0–3 [.83] | 1,305 | .02 | .03 | –.04 | .08 |

| STI signs/symptoms, % correct | 6; 0–1 [.63] | 1,234 | .02 | .01 | .00 | .05 |

| STI knowledge, % correct | 4; 0–1 [.40] | 1,322 | .05* | .02 | .01 | .10 |

| Parental communication | 7; 0–2 [.86] | 1,300 | .03 | .02 | –.02 | .08 |

| Future orientation | 4; 0–3 [.80] | 1,325 | .02 | .03 | –.07 | .03 |

| Intentions to engage in oral sex in the next year | 1; 1–4 [NA] | 1,330 | .02 | .04 | –.06 | –.10 |

| Intentions to engage in vaginal sex in the next year | 1; 1–4 [NA] | 1,320 | .02 | .04 | –.07 | .10 |

| Intentions to engage in anal sex in the next year | 1; 1–4 [NA] | 1,321 | –.04 | .04 | –.11 | .03 |

| Intentions to remain abstinent until end of high school | 1; 1–4 [NA] | 1,315 | –.02 | .05 | –.12 | .08 |

| Intentions to remain abstinent until marriage | 1; 1–4 [NA] | 1,315 | –.05 | .05 | –.15 | .05 |

| Intentions to use a condom in the next 3 months | 1; 1–4 [NA] | 1,327 | –.03 | .03 | –.09 | .03 |

| Personal limits | 6; 0–6 [.80] | 1,283 | .14 | .10 | –.06 | .33 |

| Perceived norms: most teens wish they waited | 1; 1–4 [NA] | 1,338 | .09* | .04 | .00 | .17 |

| Perceived norms: most teens my age having sex | 1; 1–4 [NA] | 1,330 | –.08* | .04 | –.16 | –.01 |

Models were adjusted for the baseline measure of the outcome, age, gender, ethnicity, time between measures, and family structure.

All psychosocial variables were coded as protective factors except for perception of friends’ behavior, exposure to risky situations, oral sex intentions, vaginal sex intentions, anal sex intentions, and perceived norms (most teens my age having sex).

Cronbach’s alphas were calculated using baseline data.

Sample sizes vary due to missing data.

SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; STI = sexually transmitted infection; NA = not applicable.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Demographic measures

Demographic measures included gender, age, race/ethnicity, family structure, and parental education, which are correlates of sexual behavior [26].

Process measures

Intervention exposure, or program coverage, among the intervention group was measured through a combination of paper-based attendance logs and computer logs that tracked student participation in individual lessons.

Data analysis

Multilevel logistic regression models were used to test for differences between treatment conditions in the primary outcome by estimating the relationship between the dependent variable (any sexual initiation) and group assignment. Similarly, secondary outcomes were evaluated using multilevel linear regression models. Age, gender, ethnicity, time between measures, and family structure were entered into all models as covariates to adjust for any group differences that may have been present prior to intervention implementation. Multilevel models were used to adjust the regression coefficients and their standard errors for intra-class correlation present in the data resulting from students being sampled from within schools. Intra-class correlation ranged from 0.00 to 0.04 across the various outcomes. A Wald test was used to test for significance of group differences, with type I error rate set at 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

The baseline sample had a mean age of 14.3 years (SD = .59), and was 59% female, 74% Hispanic, 17% African American, and 9% other race/ethnicity. Close to 20% of students reported ever engaging in any type of sex (vaginal, oral, or anal) at baseline. No significant differences in these characteristics were observed across conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at baseline among the final analytic sample (n = 1,374)

| Measure | Intervention (n = 768) |

Control (n = 606) |

Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % or Mean (SD) |

n | % or Mean (SD) |

N | % or Mean (SD) |

|

| Gender (% Female) | 444 | 57.8 | 366 | 60.4 | 810 | 59.0 |

| Age (Years) | 768 | 14.3 (0.62) | 606 | 14.3 (0.56) | 1,374 | 14.32 (0.59) |

| Race | ||||||

| African American | 139 | 18.1 | 99 | 16.3 | 238 | 17.3 |

| Hispanic | 563 | 73.3 | 449 | 74.1 | 1,012 | 73.7 |

| Other | 66 | 8.6 | 58 | 9.6 | 124 | 9.0 |

| Family structure | ||||||

| One biological or adopted | 298 | 38.8 | 238 | 39.3 | 536 | 39.0 |

| Both biological or adopted | 308 | 40.1 | 247 | 40.8 | 555 | 40.4 |

| Biological/adopted + someone else | 86 | 11.2 | 84 | 13.9 | 170 | 12.4 |

| Other | 62 | 8.1 | 35 | 5.8 | 97 | 7.1 |

| Missing | 14 | 1.8 | 2 | .3 | 16 | 1.2 |

| Parental education | ||||||

| Did not finish high school | 289 | 37.6 | 236 | 38.9 | 525 | 38.2 |

| Graduated from high school | 196 | 25.5 | 151 | 24.9 | 347 | 25.3 |

| Some college | 112 | 14.6 | 77 | 12.7 | 189 | 13.8 |

| Graduated college | 88 | 11.5 | 102 | 16.8 | 190 | 13.8 |

| Missing | 83 | 10.8 | 40 | 6.6 | 123 | 9.0 |

| Ever had sex (any) | ||||||

| % Yes | 153 | 19.9 | 114 | 18.8 | 267 | 19.4 |

| Missing | 2 | .3 | 5 | .8 | 7 | .5 |

| Ever had sex (oral) | ||||||

| % Yes | 102 | 13.3 | 61 | 10.1 | 163 | 11.9 |

| Missing | 1 | .1 | 6 | 1.0 | 7 | .5 |

| Ever had sex (vaginal) | ||||||

| % Yes | 117 | 15.2 | 85 | 14 | 202 | 14.7 |

| Missing | 1 | .1 | 5 | .8 | 6 | .4 |

| Ever had sex (anal) | ||||||

| % Yes | 48 | 6.3 | 29 | 4.8 | 77 | 5.6 |

| Missing | 2 | .3 | 4 | .7 | 6 | .4 |

SD = standard deviation.

Intervention exposure

We created five categories of intervention exposure: completion of no lessons (“no exposure”), 1–4 lessons (“low exposure”), 5–8 lessons (“mid-exposure”), 9–12 lessons (“high exposure”), and all 13 lessons (“full exposure”). Exposure varied among intervention students: 6% received “no exposure,” 12% received “low exposure,” 28% received “mid-exposure,” 39% received “high exposure,” and 14% received “full exposure” to the intervention.

Intervention effects

There was no significant difference in the delay of sexual activity (Table 2) or in any other sexual behavior between intervention and control students, either in the total sample or subgroup analyses. However, there were significant between-group differences for some psychosocial variables (Table 3). In ninth grade, intervention students reported greater knowledge about STIs and condoms, more positive beliefs about waiting until marriage to have sex, perceived their friends as having more positive beliefs about abstinence, and greater self-efficacy to use condoms than control students. Intervention students were also more likely than control students to perceive that other teens who had had sex wished they had waited and that most teens their age were not having sex (perceived norms).

Table 2.

| Outcome | Sample size | ORc | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any sex | Overall | 1,079 | 1.00 | .70 | 1.41 |

| Males only | 421 | .99 | .57 | 1.74 | |

| Females only | 658 | .99 | .63 | 1.56 | |

| African Americans only | 154 | 1.36 | .56 | 3.33 | |

| Hispanics only | 835 | .88 | .59 | 1.32 | |

| Oral sex | Overall | 1,079 | 1.09 | .67 | 1.76 |

| Males only | 421 | 1.07 | .51 | 2.21 | |

| Females only | 658 | 1.17 | .61 | 2.25 | |

| African Americans only | 154 | 2.60 | .74 | 9.11 | |

| Hispanics only | 835 | .77 | .37 | 1.58 | |

| Vaginal sex | Overall | 1,079 | 1.01 | .69 | 1.48 |

| Males only | 421 | .96 | .53 | 1.77 | |

| Females only | 658 | 1.03 | .62 | 1.70 | |

| African Americans only | 154 | .81 | .25 | 2.67 | |

| Hispanics only | 835 | .93 | .60 | 1.44 | |

| Anal sex | Overall | 1,080 | 1.05 | .47 | 2.35 |

OR = Odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Main study outcomes were analyzed for students who reported not having any sex at baseline.

Adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, time between measures, and family structure, as well as for intra-class correlation using Stata version 12 SE Mixed Effects.

Odds of initiation in the intervention group relative to the control group; therefore, an OR less than 1 is in the desired direction.

Exploratory post-hoc analyses: Sexual initiation among intervention students taking into account intervention exposure

To explore the association between level of intervention exposure and changes in sexual initiation outcomes, we conducted post-hoc exploratory analyses within the intervention condition. Multilevel logistic regression modeling was used to estimate the association between the outcome and varying levels of intervention exposure. Indicator variables were created to indicate groupings of exposure level and entered in the model simultaneously. As stated previously, we created five categories of intervention exposure. Models were fit sequentially first using “no exposure” as the referent and all four indicator variables. Subsequent models were then estimated combining categories with the referent to determine if a threshold effect could be identified. Wald tests were used to test statistical significance, with type I error rate set at 0.05.

When level of intervention exposure among intervention students was accounted for in post-hoc analyses, some significant associations did emerge (Table 4). Among intervention students, those in the “full exposure” group were 81% less likely than those in the “low exposure” group to initiate any type of sex (p < .01). Using the same referent group (“low exposure”), students in the “mid-exposure” group were 58% less likely to initiate any type of sex (p < .01). There was no significant association between “high exposure” and “low exposure” students on the “any sex” variable. A similar pattern of results was obtained for initiation of vaginal sex. For oral sex, a significant association was found only between “full exposure” and “low exposure” students, with the former being 86% less likely than the latter to initiate oral sex (p < .05). Small sample sizes precluded us from examining models for initiation of anal sex. Students across the exposure categories did not differ significantly by gender, race/ethnicity, family structure, or parental education.

Table 4.

| Intervention exposure category |

Any sex | Vaginal sex | Oral sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (reference) | — | — | — |

| Medium | .42** | .42* | .52 |

| High | .59 | .58 | .69 |

| Full | .19** | .20** | .14* |

Sample restricted to those sexually inexperienced at baseline in the intervention group only (n = 612).

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and gender.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the behavioral and psychosocial effects of IYG-Tech, a completely computer-based HIV, STI, and pregnancy prevention curriculum for middle school students. We found that IYG-Tech did not significantly impact sexual initiation or any other sexual behavior. However, we did find that IYG-Tech significantly impacted several important psychosocial factors (e.g., knowledge about STIs and condoms, beliefs about waiting until marriage to have sex, perceived friends’ beliefs about abstinence, self-efficacy to use condoms, perceived norms about sex). Furthermore, we found that post-hoc analyses conducted among intervention students revealed some significant associations: “full exposure” and “mid-exposure” students were less likely than “low exposure” students to initiate any type of sex. Taken together, the present study’s findings suggest that the efficacy of IYG-Tech requires additional evaluation.

The lack of significant impact on sexual behavior may be due to several reasons. First, because it is completely computer-based, IYG-Tech lacks some components that are common to effective sexual health education programs, namely group activities, in-person role-play scenarios, and small-group discussions [27]. However, as mentioned previously, other computer-based programs have demonstrated positive sexual behavior health outcomes, so there is evidence that technology-based programs, which do not include a class group process or teacher-facilitated instruction, can impact behavior [7–9]. There is also evidence that computer-based HIV prevention interventions (designed for adults and for adolescents) have effect sizes for condom use similar to those of traditional interventions [6]. Second, and perhaps more likely, most (86%) intervention students did not receive the entire 13-lesson IYG-Tech curriculum. Research with the original IYG program suggests that to achieve positive behavioral effects students should be exposed to at least 13 lessons (with each lesson lasting 35–45 minutes; Markham, unpublished). Despite providing incentives to schools and working diligently with them to adequately plan for IYG-Tech implementation, we found that many students did not receive all the lessons because of standardized testing preparation and make-up testing activities. These academic activities not only affected the implementation of IYG-Tech, in particular, but also provide a reminder of the difficulties in implementing and evaluating school-based sexual health programs in an environment that places increased priority on core academic subjects in schools [28]. However, we found that even limited intervention exposure was sufficient to impact some psychosocial factors, albeit modestly, making it more difficult to detect a difference in the more distal binary sexual behavior outcome.

Although the present study’s findings do not support the hypothesized behavioral efficacy of IYG-Tech, they do support the premise that a completely computer-based intervention could potentially impact behavior for two important reasons. First, although not conclusive because they are derived from a one-group design, our exposure data suggest that there is an association between delayed sexual initiation and full or mid-levels of exposure to IYG-Tech. Although results for sexual initiation were not statistically significant for high levels of exposure, we still found positive trends, and the lack of significance could be an anomaly of sample size within each category. Second, IYG-Tech incorporates many strategies (e.g., simulated skills practice, modeling, reinforcement and feedback; tailored messages by sexual experience and gender) necessary for the development of effective computer-based sexual health education programs [5, 29, 30]. Other computer-based sexual health education programs that increased risk reduction self-efficacy, increased abstinence, and/or reduced unprotected sex also included many of these strategies [7, 8, 14].

The present study’s findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, generalizability of findings is limited to English-speaking students who attend schools in urban settings. However, generalizability can still be made to English-speaking students at urban schools who choose to participate in sexual health programs. Second, the response rate was lower than desired, and attrition was high among students who were eligible to participate in the study. Furthermore, students retained in the final sample had fewer risk behaviors than those who were lost to follow-up, so there may be some selection bias. Because students in the follow-up sample reported less risky behavior, our ability to detect a difference between the two groups may also have been impaired. Third, recruitment rates differed between the conditions, with more control students than intervention students declining to participate in the study. We do not believe this difference was due to the schools’ knowledge of their assigned condition, because teachers and students were unaware of it, and all staff recruited students using a standardized protocol. Furthermore, although we used A-CASI to help increase student literacy and comfort in answering sensitive questions [31], measures were self-reported, so responses could be subject to bias. Finally, full exposure to the intervention (i.e., all 13 lessons) was low; thus, IYG-Tech would benefit from an additional randomized controlled trial to determine if full intervention exposure results in behavior change. Potential options for increasing intervention exposure include providing larger monetary incentives to participating schools or delivering IYG-Tech outside of the school setting through social media or other Internet sites [28].

Conclusion

Despite a surge in the application of technology and an integration of digital approaches to education in schools, there is a dearth of computer-based sexual health education programs, especially targeting middle school students. Although IYG-Tech did not significantly impact sexual behavior, it did significantly impact some determinants of sexual behavior. Furthermore, analyses which took into account intervention exposure among the intervention group yielded positive results for delaying sexual initiation. Collectively, our findings indicate that IYG-Tech significantly impacts some determinants of sexual behavior, and that additional efficacy evaluation with full intervention exposure may be warranted.

Implications and Contributions

Technology has the potential to increase the fidelity and reduce the implementation costs of sexual health education programs aimed at preventing STIs/HIV and unplanned pregnancies, but few technology-based programs target early adolescents. IYG-Tech impacts some determinants of sexual behavior, but additional efficacy evaluation with full intervention exposure is needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lionel Santibáñez for his editorial assistance.

Sources of Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (5 R01 MH085594).

Abbreviations

- STI

sexually transmitted infection

- IYG

It’s Your Game

- ACASI

audio–computer-assisted self-interview

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

These findings were presented at the American Public Health Association 142nd Annual Meeting and Exposition.

Financial Disclosure: All authors have no financial relationships relevant to this study to disclose.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: All authors have no potential conflicts of interest, either real or perceived, to disclose.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Adolescent Health. Trends in Teen Pregnancy and Childbearing. [Accessed August 12, 2014]; [Online]. Available at: < http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/adolescent-health-topics/reproductive-health/teen-pregnancy/trends.html>.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. [Accessed August 12, 2014]; [Online]. Available at: < http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/toc.htm>.

- 3.Madden M, Lenhart A, Duggan M, et al. Teens and Technology 2013. [Accessed August 12, 2014]; [Online]. Available at: < http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/03/13/teens-and-technology-2013/>. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyar R, Levine D, Zensius N. TECHsex USA: Youth Sexuality and Reproductive Health in the Digital Age. Oakland, CA: ISIS, Inc.; 2011. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- 5.Card JJ, Kuhn T, Solomon J, et al. Translating an effective group-based HIV prevention program to a program delivered primarily by a computer: methods and outcomes. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23:159–174. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS (London) 2009;23:107–115. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ybarra ML, Bull SS, Prescott TL, et al. Adolescent abstinence and unprotected sex in CyberSenga, an Internet-based HIV prevention program: randomized clinical trial of efficacy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70083. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein CH, Card JJ. Preliminary efficacy of a computer-delivered HIV prevention intervention for African American teenage females. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23:564–576. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.6.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downs JS, Murray PJ, Bruine de BW, et al. Interactive video behavioral intervention to reduce adolescent females’ STD risk: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1561–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lightfoot M, Comulada WS, Stover G. Computerized HIV preventive intervention for adolescents: Indications of efficacy. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1027–1030. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberto AJ, Zimmerman RS, Carlyle KE, et al. A computer-based approach to preventing pregnancy, STD, and HIV in rural adolescents. J Health Commun. 2007;12:53–76. doi: 10.1080/10810730601096622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chavez NR, Shearer LS, Rosenthal SL. Use of digital media technology for primary prevention of STIs/HIV in youth. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(Suppl. 4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di NJ, Schinke SP, Pena JB, et al. Evaluation of a brief computer-mediated intervention to reduce HIV risk among early adolescent females. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Peskin MF, et al. It's Your Game: Keep It Real: Delaying sexual behavior with an effective middle school program. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markham CM, Tortolero SR, Peskin MF, et al. Sexual risk avoidance and sexual risk reduction interventions for middle school youth: A randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, et al. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shegog R, Peskin MF, Markham C, et al. ItsYourGame-Tech: Toward sexual health in the digital age. Creative Education. 2014 doi: 10.4236/ce.2014.515161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham JW, Flay BR, Johnson C, et al. Group comparability: A multiattribute utility measurement approach to the use of random assignment with small numbers of aggregated units. Eval Rev. 1984;8:247–260. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coyle K, Kirby D, Parcel G, et al. Safer Choices: A multicomponent school-based HIV/STD and pregnancy prevention program for adolescents. J Sch Health. 1996;66:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coyle KK, Kirby DB, Main BV, et al. Draw the Line/Respect the Line: A randomized trial of a middle school intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:843–851. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borawski EA, Trapl ES, Lovegreen LD, et al. Effectiveness of abstinence-until-marriage sex education among middle school adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29:423–434. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basen-Engquist K, Masse LC, Coyle K, et al. Validity of scales measuring the psychosocial determinants of HIV/STD-related risk behavior in adolescents. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:25–38. doi: 10.1093/her/14.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller KS, Kotchick BA, Dorsey S, et al. Family communication about sex: what are parents saying and are their adolescents listening? Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:218–222. 235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirby D, Lepore G. Sexual risk and protective factors: Factors affecting teen sexual behavior, pregnancy, childbearing and sexually transmitted disease: Which are important? Which can you change? ETR Associates & The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herbert PC, Lohrmann DK. It's all in the delivery! An analysis of instructional strategies from effective health education curricula. J Sch Health. 2011;81:258–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strasburger VC, Brown SS. Sex education in the 21st century. JAMA. 2014;312:125–126. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soto Mas FG, Plass J, Kane WM, et al. Health education and multimedia learning: connecting theory and practice (Part 2) Health Promot Pract. 2003;4:464–469. doi: 10.1177/1524839903255411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kreuter MW, Strecher VJ, Glassman B. One size does not fit all: The case for tailoring print materials. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21:276–283. doi: 10.1007/BF02895958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Tu X. Accuracy of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) and self-administered questionnaires for the assessment of sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:541–552. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]