Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas are characterized by the desmoplastic reaction, a dense fibrous stroma that has been shown to be supportive of tumor cell growth, invasion, and metastasis, and has been associated with resistance to chemotherapy and reduced patient survival. Here, we investigated targeted depletion of stroma for pancreatic cancer therapy via taxane nanoparticles. Cellax-DTX polymer is a conjugate of docetaxel (DTX), polyethylene glycol (PEG), and acetylated carboxymethylcellulose, a construct which condenses into well-defined 120nm particles in aqueous solution, and is suitable for intravenous injection. We examined Cellax-DTX treatment effects in highly stromal primary patient-derived pancreatic cancer xenografts and in a metastatic PAN02 mouse model of pancreatic cancer, focussing on specific cellular interactions in the stroma, pancreatic tumor growth and metastasis. Greater than 90% of Cellax-DTX particles accumulate in smooth muscle actin (SMA) positive cancer-associated fibroblasts which results in long-term depletion of this stromal cell population, an effect not observed with Nab-paclitaxel (Nab-PTX). The reduction in stromal density leads to a >10-fold increase in tumor perfusion, reduced tumor weight and a reduction in metastasis. Consentingly, Cellax-DTX treatment increased survival when compared to treatment with gemcitabine or Nab-PTX in a metastatic PAN02 mouse model. Cellax-DTX nanoparticles interact with the tumor-associated stroma, selectively interacting with and depleting SMA positive cells and macrophage, effects which are associated with significant changes in tumor progression and metastasis.

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, tumor-associated stroma, nanoparticles

1. Introduction

The desmoplastic response, a dense accumulation of fibrous and cellular stroma, is a prominent feature of pancreatic tumors. Stromal components, such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, inflammatory cells and extracellular matrix, provide a tumor microenvironment that promotes tumor progression, metastasis and treatment resistance [1, 2]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) represent the majority of non-cancer cells within the tumor and are characterized by the expression of smooth-muscle actin (SMA). Rather than being bystanders, CAFs closely interact with tumor cells and actively promote tumor growth through the secretion of proteins that activate signaling pathways involved proliferation and metastasis [1]. In the context of therapy, stroma is understood to significantly impair drug delivery: the contractile phenotype of CAFs, inadequate vascularisation, high extracellular matrix (ECM) density, and high interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) impair the transport of chemotherapeutics to tumor cells [3-5]. Tumor-associated stroma is widely recognized as a target for therapy, both to normalize the microenvironment, and to reduce drug delivery barriers [3-9].

In contrast to other solid tumors, tumor-associated stroma represents the most prominent component of pancreatic tumors, and therefore, stroma has become a focus of pancreatic cancer therapeutic development. Approaches to stromal control have included modulation of matrix [5], targeting of VEGF-driven angiogenesis [10], and suppression of the hedgehog pathway [9], but clinical success has been limited, as human tumors tend to become resistant to drugs that block these pathways [3]. Recently, Von Hoff et al. [11] reported that gemcitabine plus Nab-PTX (Abraxane) significantly prolongs survival compared to gemcitabine alone [12]. Nab-PTX is a complex of paclitaxel with human albumin, and is understood to interact with SPARC protein, which acts to concentrate the drug in the tumor compartment [13-15]. Pancreatic tumors are display high SPARC expression, consistent with highly stromal tumors [16], and it has been demonstrated that Nab-PTX depletes pancreatic tumor stromal content, a reduction correlated to increased uptake of gemcitabine [11]. These findings support the idea that the stroma represents a clinically relevant target in pancreatic cancers.

Cellax-DTX is a conjugate of PEGylated carboxymethylcellulose and docetaxel: this macromolecule condenses into well-defined 120nm nanoparticles in saline, and is stable in serum, against dilution, and in storage at 4°C. It has been demonstrated that these particles are long circulating compared to native DTX and Nab-PTX, and exhibit a 5 and 10-fold increase in tumor accumulation, respectively [17-19]. We recently reported that Cellax-DTX depletes SMA positive stroma in breast cancer models, with significant reduction in metastatic potential [20]. In that study, the model was established by injecting tumor cell lines into the mammary fatpad, which did not exhibit the true anatomical structure of a tumor microenvironment presented in humans [21]. This previous study only reported significant association of Cellax with CAFs, but did not systemically examine the uptake of Cellax nanoparticles in other major cell populations of the tumor microenvironment, nor did prior work determine the pharmacodynamic impact on these cell types. These mechanistic studies are required to conclude the target of Cellax in solid tumors. In the current study, we aimed at further delineating the biofate of Cellax nanoparticles in a relevant tumor microenvironment, identifying the target of Cellax through a pharmacodynamic mechanistic study and validate its stromal modulating effect in another tumor type (i.e. stroma-rich pancreatic tumor). We employed the human derived pancreatic xenograft models, which displayed a relevant tumor microenvironment with the true anatomical structure reported with human tumors [22], to study Cellax uptake and compare the pharmacodynamics of Cellax and Nab-PTX in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment. Nab-PTX was included as a control in this study, as it is a nanoparticle formulation of taxane, was recently approved for pancreatic tumor therapy, and appears to exhibit microenvironment modulating activity.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Reference Drugs

Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) sodium salt 30000-P was purchased from CPKelco (Atlanta, GA, USA). Docetaxel (DTX) was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). Polyethylene glycol methyl ether (mPEG-OH, MW=2000), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide HCl (EDC.HCl), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Oakville, ON, CA). DiI (1,10-dioctadecyl-3,3,3030-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate, D-307) was purchased from Invitrogen (Burlington, ON, CA). Gemcitabine was purchased from BetaPharma (Branford, CT, USA). Abraxane (Nab-PTX) was purchased from the University Health Network (UHN) pharmacy. Tissue-Tek® OCT™ compound was purchased from VWR (Mississauga, ON, CA).

Preparation of Cellax-DTX nanoparticles.

The Cellax-DTX polymer consists of an acetylated carboxymethylcellulose backbone coupled to DTX and PEG via ester linkages: the synthesis and characterization are previously described [17-19, 23]. Cellax-DTX nanoparticles were prepared by a nanoprecipitation technique as previously described [17-19, 23], yielding sterile 120nm particles in saline. Particle size was measured on a Malvern NanoZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) instrument. To determine the concentration of DTX in nanoparticle suspension, Cellax-DTX particle solutions (100μL) were lyophylized, dissolved in deuterated dimethylsulphoxide (dDMSO, 900μL) containing 2-methyl-5-nitrobenzoic acid (1mg/mL) internal standard (IS), and were analyzed by 1H NMR. DTX concentration was calculated using a DTX/IS response factor generated using a DTX (1mg/mL) solution containing the IS. Cellax-DTX particles containing DiI (Cellax-DTX-DiI) were prepared and characterized as reported previously: all Cellax-DTX-DiI nanoparticle suspensions were adjusted to 300μg DiI/mL for intravenous administration (200μL) for tissue distribution analyses [19].

Cell Culture

The mouse PAN02 pancreatic cancer cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C and 5% CO2 for a maximum of 10 passages.

Mouse models of pancreatic cancer

The OCIP19 and OCIP23 primary pancreatic xenografts were established from patient pancreatectomy samples in accordance to institutional guidelines for human and animal research, as previously described [24]. Briefly, tumor fragments were surgically implanted on top of the pancreas of 4-5 week old male SCID. Treatments were initiated when tumors were 5mm in diameter.

For experiments involving orthotopic implantation of the PAN02 cell line, female C57/BL6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbour, ME, USA) were anesthetized, a left lateral laparatomy (subcostal 4mm incision into the peritoneal cavity) was performed, and the spleen and pancreas were exposed and mobilized. PAN02 cells (50μl, 2.0 × 107 cells/mL) were injected into the pancreas, the spleen and pancreas were placed back within the abdominal cavity, and the muscle and skin layers were closed with sutures.

All animal use protocols were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University Health Network (AUP 786 and 2402). Maximum tolerated doses (MTDs) of Cellax-DTX, DTX, gemcitabine, and Nab-PTX were established in previous reports [17, 19].

OCIP19 Models

Pharmacodynamic study (1 dose) –Five mice per treatment group were treated intravenously with saline, Nab-PTX (50mg PTX/kg), or Cellax-DTX (170mg DTX/kg), and were sacrificed at 1, 3 and 6 d post treatment. At each timepoint, tumors were fixed in buffered formalin for histological analysis. A subset of mice (n=5) in this experiment were treated with Cellax-DTX-DiI (fluorescent particles), and were sacrificed 24h after treatment: tumors were frozen in OCT for cryosectioning and histology analysis.

Efficacy study (3 dose): primary human pancreatic xenografts (OCIP19 and OCIP23) were divided into fragments and sutured to the surface of the pancreas in male SCID mice [24]. When tumors were palpable, mice were treated intravenously (iv) with saline, Nab-PTX (50mg PTX/kg), or Cellax-DTX (170mg DTX/kg) q1w × 3. Weight and mouse health was monitored throughout the course of therapy. Two weeks following the 3rd treatment, mice were injected with FITC-lectin (Sigma Aldrich, Oakville, ON, CA L0401, 0.05mg in saline), and sacrificed 4h later. On necropsy, tumors were weighed and fixed for histology analysis, and mice were examined for metastatic presentation in the peritoneum, diaphragm, liver, hepatic portal, spleen, and mesentarium.

PAN02 Models

1 dose sc model: 2wk after inoculation with PAN02 cells, mice were treated with a single dose IV with therapies at MTD: DTX (40mg/kg), Nab-PTX (170mg PTX/kg), and Cellax-DTX (170mg DTX/kg). Six wk after inoculation, the mice were sacrificed, tumors were weighed and fixed for histological analysis.

2 dose sc model: 2wk after inoculation with PAN02 cells, mice were treated with DTX (25mg/kg), Nab-PTX (50mg PTX/kg), gemcitabine (120mg/kg), or Cellax-DTX (150 mgDTX/kg). Mice treated with gemcitabine received a second dose 3 d after the first dose. Three wk after inoculation, the treatments were repeated (2nd round). Five weeks after inoculation, the mice were sacrificed, pancreatic tumors were excised and weighed, and tumors were fixed for histological analysis.

Metastatic model: PAN02 cells were adjusted to 3.0 × 106 cell/mL in serum-free DMEM. C57BL6 mice were sedated and 1mL of cell suspension was injected to the intraperitoneal space. One day after inoculation, mice (10 per group) were injected iv with native DTX (40mg/kg), Cellax-DTX (40 or 170mg DTX/kg), Nab-PTX (50mgPTX/kg), or GEM (120mg/kg). A second round of treatment followed 1wk later. Mice were weighed 3 times weekly, and were sacrificed when humane endpoints were reached, including >20% weight loss, lethargy, piloerection, or a swollen abdomen.

Tissue analysis

Primary tumors and metastases were fixed in 10% formalin for 3 days, and subsequently stored in 70% ethanol. Samples were mounted in paraffin blocks, 10 μm slices were collected, and were deparaffinised for IHC. Cryo-preserved samples were mounted in OCT, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Chromogenic IHC: All tissues were prepared in 10 μm thick sections, and were stained for specific cell markers. Preparations included α-SMA (mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb, MO851), Dako, Burlington ON, 1/200 dilution), Ki67 (rabbit polyclonal antibody (pAb, NB-110-90592), Novus, Littleton CO, USA, 1/1500 dilution), or F4/80 (rat mAb (MCA497GA), Serotec, Raleigh NC, USA, 1/500 dilution), CD31 (rabbit pAb (sc-1506R), Santa Cruz, Dallas TX, USA, 1/2500 dilution). To evaluate tumor morphology and tumor-associated stroma relative to tumor epithelium, sections were stained with H&E and Masson’s trichrome. Chromogenic slides were scanned on an Aperio ScanScope XT (AOMF, Toronto, ON, CA), and images were analyzed using Definiens Tissue Studio (Definiens, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Fluorescent IHC: All tissues were prepared in 10 μm thick sections, and were stained for specific cell markers. Preparations included α-SMA (cryosection: Dako M0851, 2% PFA fix, 1/1500, Invitrogen A11029 Alexa488 goat anti-mouse, or fixed: Dako M0851, no pre-treatment, 1/200), F4/80 (Santa Cruz 26642, acetone fix, 1/25, Jackson 705-225-147 Alexa488 donkey anti-goat), or CD31 (BD 550274 clone MEC13.3, acetone fix, 1/200, Invitrogen 11006 Alexa488 goat anti-rat). Fluorescent sections from the OCIP19 pharmacodynamic study were imaged on an Ariol microscope (Leica, Solms, GE), and images were analyzed using Definiens Tissue Studio software. Fluorescent slides from the 3-dose OCIP study were imaged on an Olympus Fluoview confocal microscope at 20X magnification (Olympus, Richmond Hill, CA) and images were quantitatively analyzed on ImagePro Plus (Media Cybernetics) using the established protocols [25].

Statistical Analysis

All graphed data are expressed as the mean ± standard error. For the pharmacodynamic data, linear regression was used to model the effect of time and treatment. Significance in figures refers to comparison of treatments to each other unless otherwise noted, whereas results reported in the text also include comparison to controls. All other statistical analyses were performed with the two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data, or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. Median survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare the survival distributions of treatment groups. A difference between groups with p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Particle tissue distribution and co-localization measurements are reported with +/− standard deviation values.

Results

We first examined the MTDs for each formulation under different dosing regimens and in different strains of mice. While Nab-PTX could be safely dosed at 170 mg/kg for one dose, we observed incidence of death in >40% of the animals receiving 2 cycles of Nab-PTX at 170 mg/kg [17], and the MTD for multidose of Nab-PTX in mice was only 50 mg/kg. This was also reported by others [26], an effect attributed to an immune response to human serum albumin..

Cellax-DTX targets the stromal compartment

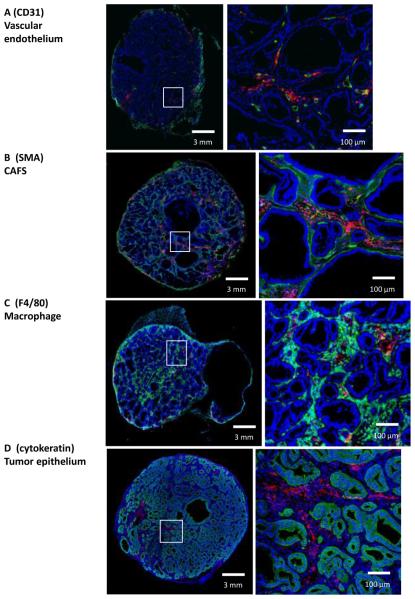

To study intratumoral distribution of Cellax-DTX particles, mice bearing orthotopic OCIP19 tumors were treated with a single dose of fluorescent Cellax-DTX-DiI. Analysis of particle penetration from blood vessels (CD31) revealed broad distribution of Cellax-DTX away from microvessels (Fig. 1A), with a mean diffusive distance of 34 ± 5.1 μm at 24h post treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Cellax-DTX particles distributed from the rim to corebut were not homogeneously distributed throughout the tumor. Rather, particles were associated with specific structures or stromal cell types, in a time dependant manner. Increased particle densities were observed close to microvessels (Fig. 1A), andmean penetration of Cellax-DTX was found to increase with time. At 1, 6, and 24h post treatment the mean distance of Cellax-DTX from the nearest blood vessel was 14 ± 2.5, 18 ± 3.1, and 34 ± 5.1μm, respectively. In contrast, no extravasation was observed from blood vessels in normal tissues such as the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Within stromal tissue, 35.1 +/− 4.9% of Cellax-DTX-DiI signal was associated with vasculature 24h after treatment, and the balance of the Cellax-DiI population migrated into the stromal tissue. As shown in Fig. 1B and 1C, Cellax-DTX-DiI particles are principally located in the stromal tissues that surround glandular tumor epithelial structures. These tissues contain both SMA positive CAFs (Fig. 1A) and F4/80 positive macrophage (Fig. 1B). The accumulation of Cellax-DTX-DiI particles in stromal areas was 13.2 ± 4.7 fold higher when compared to epithelial regions (93 ± 10% of total particle signal). Patterns of cellular interaction within the stroma were further analyzed by co-localizing DiI with SMA or F4/80 markers. As shown in Fig. 1B and C, approximately 75-80% of Cellax-DTX-DiI particles are associated with either SMA positive CAF or F4/80 positive macrophage. Due to the spatial resolution of microscopy and the close association of CAFs and macrophage in stroma, exact deconvolution of cell association is not possible. As shown in Fig. 1D, Cellax-DTX did not accumulate in cytokeratin positive tumor epithelial cells.

Figure 1. Intratumoral distribution of Cellax-DTX-DiI.

All tumor sections are OCIP19, and are representative samples from 1d post-dosing. (A) Representative sections stained for DAPI (blue) and CD31 (green). Cellax-DTX-DiI (red) is seen to be extravasating from the vasculature into tumor tissue. (B) Representative sections stained for DAPI (blue), SMA (green). Cellax-DTX-DiI is red. Cellax-DTX-DiI is 79% co-localized with the SMA positive CAF. (C) Tumor stained for DAPI (blue), and F4/80 macrophage marker (green). Cellax-DTX-DiI is red. Cellax-DTX-DiI is 75% co-localized with the macrophage. (D) Tumor stained for DAPI (blue), and cytokeratin epithelial marker (green). Cellax-DTX-DiI is red. Cellax-DTX-DiI is not co-localized with the tumor epithelial cells, being largely associated with the stromal CAF and macrophage.

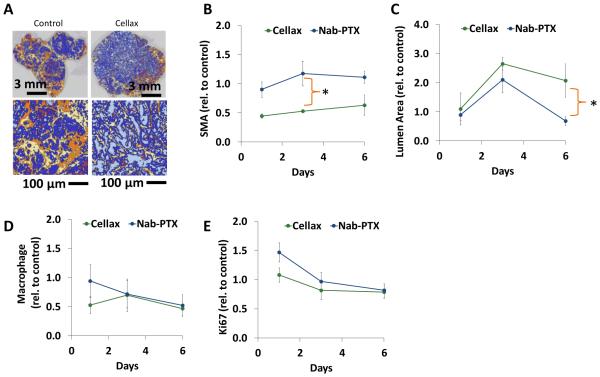

Consistent with the accumulation of Cellax-DTX particles in the stromal compartment, we observed a significant 50% decrease in SMA positive cells relative to control and Nab-PTX on Day 3 following treatment (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2 A and B, Supplemental Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Pharmacodynamic analysis of Cellax-DTX in OCIP19 pancreatic tumor tissue.

Mice bearing OCIP19 xenografts were treated with Nab-PTX (50mg/kg) or Cellax-DTX (170mg DTX/kg) once, and tissues were collected at 1, 3 and 6 days post treatment. All data was normalized to control tumor tissue. (A) Chromogenic staining of SMA was analyzed in Definiens: SMA positive tissue (orange), SMA negative stroma (yellow), tumor tissue (dark blue), open ducts (light blue) and voids (purple) were identified. (B) SMA density declined 50% following Cellax-DTX treatment. Tumors treated with Nab-PTX exhibited no significant decline in SMA. (C) Lumen area (light blue areas in Definiens analysis) increased post-Cellax-DTX treatment, and was only significant in Nab-PTX treatment as a transient effect on day 3. (D) Macrophage were identified by F4/80 chromogenic staining, and cells were identified in Definiens analysis. Macrophage density dropped significantly in the first day post-Cellax-DTX treatment, and by day 6, both Nab-PTX and Cellax-DTX treated tumors exhibited a 50% decline in this cell population. (E) Ki67 positive epithelial cells were counted in Definiens analysis: no significant effects were observed in either treatment group. * p < 0.05.

A significant 2-fold increase in duct luminal area was observed in Cellax-DTX-treated tumors on day 3 (p=0.003) and day 6 (p=0.019) when compared to control tumors, suggesting a reduction in intratumoral pressure (Fig. 2C). Nab-PTX treatment induced a transient increase in duct luminal area on Day 3 relative to control (p=0.036), but this effect was not significant at day 6. On day 6, the duct luminal area in Cellax-DTX treatments was significantly higher than the Nab-PTX treatment groups (p=0.003).

Cellax-DTX treatment caused an immediate and significant 50% decrease in macrophage content relative to control on day 1 (p=0.035), an effect that was sustained to day 6 (p=0.003) (Fig. 2D and Supplemental Fig. 2B). On the other hand, a significant macrophage reduction (50% decrease, p=0.008)was observed only on day 6 with Nab-PTX treatment. At no time point was macrophage depletion significantly different when comparing the Cellax-DTX and Nab-PTX groups to each other (p>0.05), suggesting the overall macrophage deletion effect is a common feature of both nanoparticles.

Cellax-DTX had no measurable impact on vascular density (Supplemental Figure 2C), whereas Nab-PTX treatment caused a significant decrease in density on day 3 relative to control (p=0.033).

Cellax-DTX and Nab-PTX treatments did not exert any measurable impact on tumor cell proliferation (Fig. 1E), or overall collagen content (Supplemental Fig. 2D-E).

Stromal depletion results in increased perfusion and reduced metastatic potential in patient-derived pancreatic xenografts

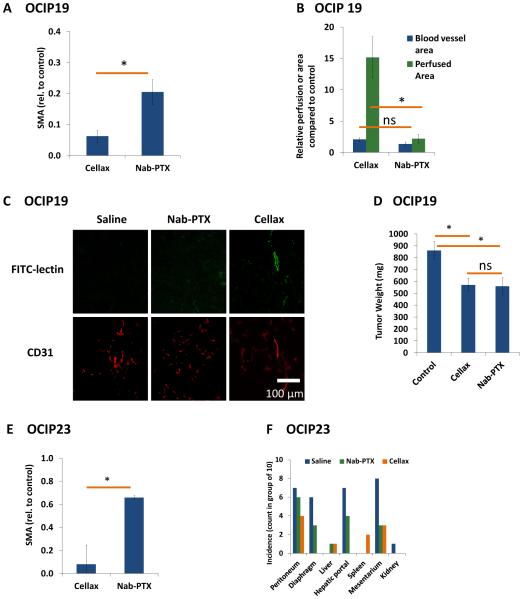

Mice bearing OCIP19 tumors were treated with 3 cycles of Cellax-DTX and Nab-PTX at their MTDs, and 2wk post-final dose were sacrificed for tumor and metastases analysis. Both Nab-PTX (p<0.001) and Cellax-DTX (p<0.001) treatments significantly reduce SMA positive CAFs in this model (80 and 90% respectively), with Cellax-DTX treatment producing a further significant reduction relative to Nab-PTX (p=0.005) (Fig. 3A) when compared with control. The remaining SMA positive cells in Cellax-DTX-treated tumors were co-localized with CD31 positive cells (vascular bed), suggesting that Cellax-DTX particles did not interact with vascular pericytes (Supplemental Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Tumor-associated stroma analysis in a multi-dose orthotopic OCIP19 pancreatic tumor model.

Mice were treated with Nab-PTX (50mg/kg) or Cellax-DTX (170mg DTX/kg) once weekly for 3 cycles, and tumor tissues were collected 2wk post final treatment. Sections were stained and imaged by confocal microscopy for image analysis. (A) multiple Nab-PTX and Cellax-DTX treatments significantly reduced SMA positive CAF cells. (B,C) Mice were treated with FITC-lectin prior to sacrifice. Perfused blood vessels are marked in green. The area of perfused tissue in tumors was significantly increased with Cellax-DTX treatment (p=0.004), compared to no significant difference in Nab-PTX treated tumors. Average blood vessel area did not increase (p=0.052) after Cellax-DTX treatment. (D) Primary OCIP19 tumors in Nab-PTX and Cellax-DTX treated groups were significantly smaller compared to control, and in visual observation, were better marginated from surrounding tissue compared to control. (E) Similar to the OCIP19 model, Cellax-DTX treatments result in a significant reduction in SMA positive CAF in the OCIP23 model. (F) OCIP23 tumors metastasize to peritoneal tissues. Cellax-DTX treatment had a significant impact on the incidence of metastasis, with marked reductions in tumor incidence. Nab-PTX treatment reduced the incidence of metastatic tumors to a lesser degree. * p<0.05; Ns = not significant.

While the effect of Cellax-DTX treatment on the CAFs population was maintained for 2wk post final treatment, the depletion of macrophages seen in the days post single dosing (Fig. 2C) was not observed as an enduring effect (p=0.4) (Supplemental Fig. 3B). Similarly, no significant difference in replicating tumor cells was detected with either Nab-PTX or Cellax-DTX (p=0.2) (Supplemental Fig. 3C).

To analyze for tissue perfusion, mice were treated with FITC-lectin 2h prior to sacrifice, and vascular structures were analyzed. The average size of each blood vessel increased 2.1 fold after Cellax-DTX treatment, but was not a significant effect (p=0.052) (Fig. 3 B,C), accompanied by a 15.2 fold increase in perfusion (p=0.004) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, no significant changes in vascular structure (p=0.589) or perfusion (p=0.093) were observed in mice treated with Nab-PTX (Fig. 3 B, C).

Treatment for 3wk with either Nab-PTX or Cellax-DTX resulted in significant tumor growth inhibition in the OCIP19 xenografts (p=0.019 and 0.008, respectively) (Fig. 3D). Similar results were observed in mice bearing OCIP23 xenografts (p<0.001 for Nab-PTX and p=0.017 for Cellax) (Supplemental Fig. 3D). As with the OCIP19 model, a reduction in SMA positive CAFs was observed in the OCIP23 model (p<0.001 for Nab-PTX and Cellax-DTX) (Fig. 3E, Supplemental Fig. 3E). Again, the anti-SMA effect was more profound with Cellax-DTX over Nab-PTX (p<0.05).

OCIP23 tumors exhibit a metastatic phenotype. At the humane endpoint, mice bearing OCIP23 xenografts displayed metastatic lesions on the peritoneal wall, diaphragm, liver, hepatic portal, spleen, and mesentery, and the primary tumors were fused with neighbouring organs such as the spleen and liver (Fig. 3F). We observed minor presentation of tumors in liver and spleen in the Cellax-DTX treated group. Treatment with Cellax-DTX significantly reduced metastases in 3 of the 7 locations (diaphragm, hepatic portal and mesentery, p=0.003, 0.001 and 0.02 respectively), whereas treatment with Nab-PTX significantly reduced metastases in only one location (mesentery, p=0.05).

Cellax-DTX treatment increases tumor perfusion and survival in the metastatic PAN02 model of pancreatic cancer

The reduction in metastatic potential in OICP models following Cellax-DTX treatment was also demonstrated in a metastatic murine pancreatic cell line PAN02.. Although the patient-derived OCIP pancreatic xenograft models represent the clinically more relevant model of pancreatic cancer, their chimeric nature may lead to reduced tumor-stroma interactions.

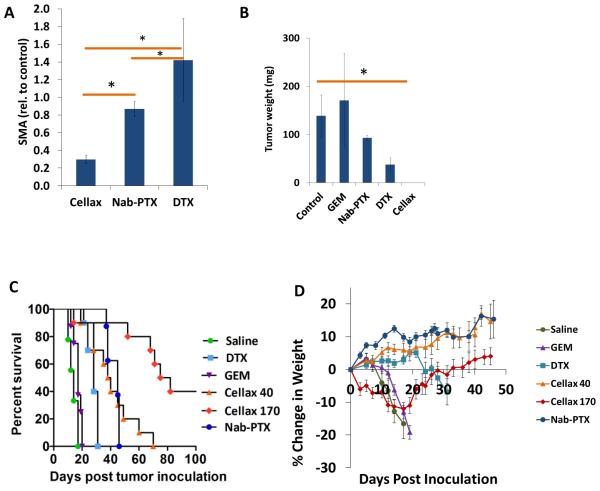

Similar to the observation made in patient-derived xenograft models, treatment of orthotopic PAN02 tumors with a single dose of Cellax-DTX significantly reduced SMA content when compared to DTX treated (p<0.001), Nab-PTX treated (p<0.001) or control (p<0.001) (Fig. 4A, Supplemental Fig. 4A). Nab-PTX and native DTX had no effect on SMA relative to control (p=0.336 and p=0.105, respectively) in this syngeneic model.

Figure 4. Tissue microenvironment effects and efficacy in a PAN02 pancreatic tumor model.

(A) Two weeks after inoculation, mice bearing advanced orthotopic PAN02 tumors were treated once with DTX (40mg/kg), Nab-PTX (170mg PTX/kg), or Cellax-DTX (170mg DTX/kg), and were sacrificed 3wk later. Levels of SMA were significantly reduced in Cellax-DTX-treated mice, whereas levels remained unchanged in the Nab-PTX and DTX groups. (B) Two weeks after inoculation, mice bearing established PAN02 tumors were treated once weekly for 2 cycles with DTX (25mg/kg), Nab-PTX (50mg/kg), or Cellax-DTX (150mg DTX/kg). Gemcitabine (120mg/kg) was administered twice weekly for 2 cycles. Two weeks post final treatment, Cellax-DTX-treated mice exhibited no detectable tumors on sacrifice, and tumors in all other groups were not significantly different relative to control. There were significant differences between the treatment groups: Cellax-DTX vs Nab-PTX (p=0.02), DTX vs Cellax (p=0.021), DTX vs Nab-PTX (p=0.029), and gemcitabine vs Cellax-DTX (p=0.021). (C) One day after inoculation, mice bearing intraperitoneal tumors were treated once weekly for 2 cycles with DTX (40mg/kg), gemcitabine (120mg/kg), Nab-PTX (50mg PTX/kg), or Cellax-DTX (40 or 170mg DX/kg). Mice were sacrificed when humane endpoints were reached, which included weight and ascites accumulation. DTX, Nab-PTX, and Cellax-DTX 40mg/kg treatments led to modest extension of survival relative to control and gemcitabine groups. Cellax-DTX 170mg/kg treatments significantly extended survival, and 40% of this group did not present with disease 100d post study initiation. (D) Weight profiles of mice bearing intraperitoneal PAN02 tumors. One day after inoculation, mice were treated once weekly for two cycles with DTX (40mg/kg), gemcitabine (120mg/kg), Nab-PTX (50mg PTX/kg), or Cellax-DTX (40 or 170mg DX/kg).

To investigate the efficacy of Cellax-DTX treatment in mice bearing orthotopic PAN02 tumors, mice were treated with q1w × 2 doses of DTX (25mg/kg), Cellax-DTX (150mg DTX/kg), and Nab-PTX (50mg PTX/kg), and q2w × 2 doses of gemcitabine (120mg/kg). On necropsy at study conclusion, mice treated with Cellax-DTX exhibited no measurable tumor in the pancreas, and were the only group that exhibited significantly smaller tumors compared to control (p=0.020) (Fig. 4B).

To examine the effect of Cellax-DTX treatment on tumor metastasis, mice were injected ip with PAN02 cells, and received 2 cycles of treatment starting 1d after inoculation. Mice were sacrificed when humane endpoints were reached. On gross examination of mice on necropsy, significant ascites and tumors were observed on the intestines, mesentary, and peritoneal walls. Progression to endpoint was rapid and characterized by a sudden onset of ascites and weight loss at day 12 with median survival of saline-treatment groups being 14d. Gemcitabine treatment only extended survival to 17d (p=0.027), whereas DTX (40mg/kg), Cellax-DTX (40mg/kg) and Nab-PTX (50mg/kg) extended median survival to 28, 39, and 45d respectively (all p<0.0001). The Cellax-DTX MTD is 170mg DTX/kg, and at this dosing level, median survival was extended to 78.5d (p<0.0001) at study endpoint, and 40% of Cellax-DTX 170mg/kg treated mice were disease free (Fig. 4C). Weight profiles show a sudden onset of loss at 10d in saline-treated mice (Fig. 4D). Saline, gemcitabine, and DTX treated mice exhibit rapid disease progression, whereas Nab-PTX and Cellax-DTX treated mice exhibit slower transitions to endpoint conditions. There was ~10% weight loss in the mice receiving Cellax-DTX at 170 mg DTX/kg after the second dose, suggesting mild to moderate toxicity. However, the mice recovered in 10 d.

Discussion

Tumor-stroma interactions are essential for all stages of tumor progression and metastasis though the activation of autocrine and paracrine signaling pathways [1]. The dense and fibrotic stroma of pancreatic tumors serve as physical barriers that inhibits drug penetration into the tumor, as well as providing a microenvironmental niche that promotes tumor cell survival [3-5]. Even though advances in chemotherapeutic and radiation treatments have increased survival in a panel of different cancers, the outcome of pancreatic cancer patients has not improved greatly over the last decade, and trials for new therapies have yielded only one new treatment (Abraxane + gemcitabine) [3, 5, 9, 10, 27].

Nanomedicine therapies leverage the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [28], and we have previously demonstrated that Cellax-DTX nanoparticles extravasate and accumulate in tumor tissues by this passive targeting mechanism [17-20]. The EPR effect targeting is only one component of the efficacy equation, as bioavailability and tumor-associated stroma effects are well known to impact nanoparticle fate [4, 29-31]. Recently, we discovered that Cellax-DTX particles interact with stroma in breast cancer models, and furthermore, we observed an increase in tumor perfusion and a reduction in metastases arising from Cellax-DTX treatment [20]. The anti-stromal and functional effects may be linked to each other, as stromal cells constrict the tumor matrix and restrict perfusion and delivery of therapy [5, 31], and signal tumor cells and promote proliferation and migratory phenotypes [27, 32-34]. The study presented here aimed to evaluate Cellax-DTX treatment in mouse models of pancreatic tumor, to expand our analysis to include the vascular and macrophage components of the stroma, and to examine treatment impact on tumor epithelial cells.

Consistent with previous observations, 93% of Cellax-DTX particles located to the tumor-associated stroma, where the particles extravasate from the vascular bed and locate to CAFs and macrophage. Specifically, 75-80% of particles were associated with either CAF or macrophage, suggesting that CAF and macrophage are closely associated and are both interacting with Cellax-DTX. As suggested by the depletion data, Nab-PTX on the other hand only lightly interacts with CAFs, but displays a strong interaction with macrophage. It may be possible that Cellax-DTX particles are entrapped by the stroma since they do not interact with tumor epithelial cells, but in fact, we measured significant transport within the stromal compartment, and throughout the entire core-to-rim structure of the tumor, suggesting that cell-specific interactions are halting the diffusion, not the matrix itself. Our observations also suggest that the Cellax-DTX packaging itself influences target cell interactions.

Macrophage depletion by Cellax-DTX and Nab-PTX was a transient observation, as macrophages were completely recovered 2wk post 3-doses. Taxanes are known to interact with tumor-associated macrophage and circulating monocytes and cause leukopenia [35]. It is also known that circulating monocytes regenerate every 2-3wk, are recruited into the tumor compartment from the circulation, where they differentiate into macrophage [36]. The macrophage regeneration contrasts with CAFs, which are locally recruited during tumorogenesis [37], and as our analysis suggests, CAFs do not rapidly regenerate. The implication is that CAF treatment is a more persistent and stable target compared to macrophage for Cellax-DTX therapy. The most plausible explanation that Cellax-DTX was more effective in depleting tumor stroma compared to Nab-PTX would be the improved tumor delivery by Cellax. As reported previously by our group [17], Cellax displayed 37-fold increased systemic exposure and 203-fold enhanced tumor uptake compared to Nab-PTX at the same dose. Moreover, Cellax particles retained in the tumor for >10 d, while Nab-PTX was cleared from the tumor in 1 d. This increased drug delivery to the tumor would likely result in improved stromal depletion by Cellax.

It has been demonstrated that CAFs facilitate metastatic progression through the activation of paracrine signaling pathways and mechanical pressure on the tumor compartment [2, 33, 38]. Along with the observation of significantly reduced metastasis in the patient-derived pancreatic xenografts and the PAN02 model, Cellax-DTX treated primary tumors exhibit better defined margins. Additionally, Cellax-DTX also acts effectively against PAN02 metastases, suggesting that the reduction in metastases arises due to a combination of tumor-site and metastatic-site activity.

A common metric of stroma is the density of the collagen matrix, which is laid down by CAFs [31, 33]. Collagen is only gradually remodelled, and the current biological activity of the stroma is measured via SMA positive CAF staining, as this cellular phenotype indicates an inflammatory condition [32, 34]. In Cellax-DTX treated tumors, CAFs content was significantly and stably reduced, and moreover, both duct luminal area and blood perfusion were accordingly increased. Mechanical constriction of the tumor is mediated by CAFs, and as has been reported [5, 20], loosening of this restriction is correlated with enhanced control of tumor growth and inhibition of metastases.

In a separate project, we have studied the molecular mechanism of Cellax targeting, and have demonstrated that Cellax adsorbed serum albumin, which bound with SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine) produced in a 50-fold higher level by CAFs compared to the tumor epithelial cells. Binding of SPARC and albumin coated Cellax trapped the nanoparticles in the microenvironment and eventually triggered cellular internalization. The results will be reported in a separate manuscript.

From the efficacy data presented in this study, it appears that stromal targeting with cytotoxic agents displayed significant antitumor efficacy, and in the orthotopic PAN02 tumor model, Cellax even abolished the tumors. However, complete tumor regression was not measured in other models, suggesting that this strategy should be combined with an agent targeting tumor epithelial cells to exert enhanced activity.

In summary, in the context of pancreatic cancers, Cellax-DTX treatment is almost entirely stroma-specific and leads to enduring CAF reduction, an effect which is correlated with increased perfusion and a demonstrated control of desmoplasia and metastasis. Our data show that treatment with Cellax-DTX results in debulking and confinement of the primary tumor, suggesting tumor resection might become possible. In addition, therapeutic reduction of desmoplasia significantly mitigates metastatic potential and might therefore represent a therapeutic approach to reduce post-surgical metastasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research Intellectual Property Development and Commercialization Fund, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PPP-122898), and the National Institutes of Health (CA17633901). S.D. Li is a recipient of a Coalition to Cure Prostate Cancer Young Investigator Award from the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and a New Investigator Award from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MSH-130195). The Ontario Institute for Cancer Research is financially supported by the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation. Ines Lohse is funded by the Knudson Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Cirri P, Chiarugi P. Cancer associated fibroblasts: the dark side of the coin. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:482–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:239–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Neesse A, Michl P, Frese KK, Feig C, Cook N, Jacobetz MA, Lolkema MP, Buchholz M, Olive KP, Gress TM, Tuveson DA. Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2011;60:861–868. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yu M, Tannock IF. Targeting tumor architecture to favor drug penetration: a new weapon to combat chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer? Cancer Cell. 2012;21:327–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Engels B, Rowley DA, Schreiber H. Targeting stroma to treat cancers. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Loeffler M, Kruger JA, Niethammer AG, Reisfeld RA. Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts improves cancer chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1955–1962. doi: 10.1172/JCI26532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, Madhu B, Goldgraben MA, Caldwell ME, Allard D, Frese KK, Denicola G, Feig C, Combs C, Winter SP, Ireland-Zecchini H, Reichelt S, Howat WJ, Chang A, Dhara M, Wang L, Ruckert F, Grutzmann R, Pilarsky C, Izeradjene K, Hingorani SR, Huang P, Davies SE, Plunkett W, Egorin M, Hruban RH, Whitebread N, McGovern K, Adams J, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Griffiths J, Tuveson DA. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jain RK. Normalizing tumor vasculature with anti-angiogenic therapy: a new paradigm for combination therapy. Nat Med. 2001;7:987–989. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ, Laheru DA, Smith LS, Wood TE, Korn RL, Desai N, Trieu V, Iglesias JL, Zhang H, Soon-Shiong P, Shi T, Rajeshkumar NV, Maitra A, Hidalgo M. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4548–4554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Von Hoff D, Ervin TJ, Arena FP, Chiorean G, Infante JR, Moore MJ, Seay TE, Tjulandin S, Ma MW, Saleh MN, Harris M, Reni M, Ramanathan RK, Tabernero J, Hidalgo M, Van Cutsem E, Goldstein D, Wei X, Iglesis JL, Renschler F, Piper V. Results of a randomized phase III trial (MPACT) of weekly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone for patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas with PET and CA19-9 correlates. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 3013;31 [Google Scholar]

- [13].Desai N, Trieu V, Yao Z, Louie L, Ci S, Yang A, Tao C, De T, Beals B, Dykes D, Noker P, Yao R, Labao E, Hawkins M, Soon-Shiong P. Increased antitumor activity, intratumor paclitaxel concentrations, and endothelial cell transport of cremophor-free, albumin-bound paclitaxel, ABI-007, compared with cremophor-based paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1317–1324. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Desai NP, Trieu V, Hwang LY, Wu R, Soon-Shiong P, Gradishar WJ. Improved effectiveness of nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab) paclitaxel versus polysorbate-based docetaxel in multiple xenografts as a function of HER2 and SPARC status. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19:899–909. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32830f9046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vogel SM, Minshall RD, Pilipovic M, Tiruppathi C, Malik AB. Albumin uptake and transcytosis in endothelial cells in vivo induced by albumin-binding protein. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L1512–1522. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.6.L1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Infante JR, Matsubayashi H, Sato N, Tonascia J, Klein AP, Riall TA, Yeo C, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Goggins M. Peritumoral fibroblast SPARC expression and patient outcome with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:319–325. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.8824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ernsting MJ, Murakami M, Undyzs E, Aman A, Press B, Li SD. A docetaxel-carboxymethylcellulose nanoparticle outperforms the approved taxane nanoformulation, Abraxane, in mouse tumor models with significant control of metastases. Journal of Controlled Release. 2012;162:575–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ernsting MJ, Tang WL, MacCallum N, Li SD. Synthetic modification of carboxymethylcellulose and use thereof to prepare a nanoparticle forming conjugate of docetaxel for enhanced cytotoxicity against cancer cells. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:2474–2486. doi: 10.1021/bc200284b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ernsting MJ, Tang WL, Maccallum NW, Li SD. Preclinical pharmacokinetic, biodistribution, and anti-cancer efficacy studies of a docetaxel-carboxymethylcellulose nanoparticle in mouse models. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1445–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Murakami M, Ernsting MJ, Undzys E, Holwell N, Foltz WD, Li SD. Docetaxel conjugate nanoparticles that target alpha-smooth muscle actin-expressing stromal cells suppress breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4862–4871. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Siolas D, Hannon GJ. Patient-derived tumor xenografts: transforming clinical samples into mouse models. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5315–5319. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chang Q, Jurisica I, Do T, Hedley DW. Hypoxia predicts aggressive growth and spontaneous metastasis formation from orthotopically grown primary xenografts of human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3110–3120. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ernsting MJ, Foltz WD, Undzys E, Tagami T, Li SD. Tumor-targeted drug delivery using MR-contrasted docetaxel - carboxymethylcellulose nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3931–3941. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chang Q, Chapman MS, Miner JN, Hedley DW. Antitumour activity of a potent MEK inhibitor RDEA119/BAY 869766 combined with rapamycin in human orthotopic primary pancreatic cancer xenografts. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:515. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hoang B, Ekdawi SN, Reilly RM, Allen C. Active targeting of block copolymer micelles with trastuzumab Fab fragments and nuclear localization signal leads to increased tumor uptake and nuclear localization in HER2-overexpressing xenografts. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:4229–4241. doi: 10.1021/mp400315p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Frese KF, Neesse A, Cook N, Tashinga EB, Lolkema MP, Jodrell DI, Tuveson DA. nab-Paclitaxel potentiates gemcitabine activity by reducing cytidine deaminase levels in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discovery. 2012;2:261–269. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–1617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fang J, Sawa T, Maeda H. Factors and mechanism of "EPR" effect and the enhanced antitumor effects of macromolecular drugs including SMANCS. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;519:29–49. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47932-X_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Murakami M, Ernsting MJ, Li SD. Tiwari A, Tiwari A, editors. Theranostic nanoparticles for cancer imaging and therapy. Nanomaterials in drug delivery, imaging, and tissue engineering. 2013:369–389. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Li SD, Huang L. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:496–504. doi: 10.1021/mp800049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Johansson A, Ganss R. Remodeling of tumor stroma and response to therapy. Cancers. 2012;4:340–353. doi: 10.3390/cancers4020340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Erkan M, Michalski CW, Rieder S, Reiser-Erkan C, Abiatari I, Kolb A, Giese NA, Esposito I, Friess H, Kleeff J. The activated stroma index is a novel and independent prognostic marker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Erkan M, Reiser-Erkan C, Michalski CW, Kleeff J. Tumor microenvironment and progression of pancreatic cancer. Experimental Oncology. 2010;32:128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Erkan M, Reiser-Erkan C, Michalski CW, Kong B, Esposito I, Friess H, Kleeff J. The impact of the activated stroma on pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma biology and therapy resistance. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:288–303. doi: 10.2174/156652412799218921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wu H, Ramanathan RK, Zamboni BA, Strychor S, Ramalingam S, Edwards RP, Friedland DM, Stoller RG, Belani CP, Maruca LJ, Bang YJ, Zamboni WC. Mechanism-based model characterizing bidirectional interaction between PEGylated liposomal CKD-602 (S-CKD602) and monocytes in cancer patients. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:5555–5564. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S35751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pollard JW. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:71–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes - bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:839–849. doi: 10.1038/nrc1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Pena C, Cespedes MV, Lindh MB, Kiflemariam S, Mezheyeuski A, Edqvist PH, Hagglof C, Birgisson H, Bojmar L, Jirstrom K, Sandstrom P, Olsson E, Veerla S, Gallardo A, Sjoblom T, Chang AC, Reddel RR, Mangues R, Augsten M, Ostman A. STC1 expression by cancer-associated fibroblasts drives metastasis of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1287–1297. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.