Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the initial effectiveness of a novel, pediatric office-based intervention in motivating mothers to seek further assessment of positive depression screens.

METHODS

In this pilot randomized controlled trial, English-speaking mothers (n=104) with positive 2-question depression screens and presenting with children 0–12 years old for well-child care to a general pediatric training clinic received interventions from a trained research assistant. The Motivating Our Mothers (MOM) intervention included office-based written and verbal targeted depression education and motivational messages encouraging further depression assessment and a semi-structured telephone “booster” delivered 2 days later. The control intervention included non-targeted written and verbal messages and 2 days later, an attention control telephone survey. Both groups received a list of depression care resources. The primary outcome was the proportion of mothers in each group who reported trying to contact any of 6 types of resources to discuss the positive screen at 2 weeks post-intervention (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01453790).

RESULTS

Despite 6 contact attempts, 10 MOM and 9 control mothers were lost to follow-up. More mothers in the MOM intervention tried to contact a resource compared to control (73.8% vs. 53.5%, difference 20.3%, 95% CI for difference −0.1% to 38.5%, P = 0.052).

CONCLUSIONS

Mothers receiving the MOM intervention made more attempts to contact a resource for follow-up of positive depression screens. If found effective in larger studies, MOM may prove a promising approach for motivating depression screen-positive mothers identified in general pediatric settings within and beyond the postpartum period, to seek further depression assessment and support.

Keywords: Maternal Depression, Screening, Primary Care, Motivational Intervention, Depression Care-Seeking

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a leading cause of disability in the US. It is common in mothers parenting young children and negatively impacts mothers’ well-being, parenting, and compliance with pediatric preventive services and practices.1–3 Children cared for by mothers with untreated or undertreated depression are at higher risk of poor health, psychiatric disorders, abuse, utilization of higher acuity healthcare, behavioral-developmental problems and medical morbidity.3–5 Mental health therapies targeted to mothers have demonstrated beneficial effects on maternal functioning and depressive symptoms. Reduction of mothers’ depressive symptoms is associated with the prevention and improvement of psychiatric, behavioral, and developmental problems in their children.6 However, maternal depression therapy is underutilized.1,7 While the contributing factors are complex, there is evidence that mothers in need of depression care face barriers in diagnosis, care-seeking, referral, and treatment.8 Growing evidence, primarily in the postpartum period, suggests that interventions targeted to some of these barriers can improve the utilization of maternal depression care.9–11

Pediatric visits provide an opportunity to identify mothers with depression and motivate them to take up effective treatments. Because pediatricians care for 80% of children up to 5 years of age12 and children are seen at regular intervals for well-child care, mothers are more likely to see their child’s pediatrician than their own health care provider in a given year.13 Mothers understand that their emotional health affects their child’s well-being and, if placed in that context, find it appropriate for pediatricians to inquire about depression and recommend follow-up.14,15 Pediatric providers know that maternal depression affects children’s well-being and health practices and are receptive to guidelines recommending pediatric-based maternal depression screening.16,17 Pediatric-based maternal depression screening instruments have been validated18,19, universal screening programs in pediatric settings have been successfully tested9,11 and 16–39%2,9 of mothers accompanying children to pediatric visits have been found to have positive depression screens. While literature on the uptake of maternal depression care referrals in pediatric settings is encouraging8–11,20,21, no standardized pediatric-based approach exists for encouraging depression-screen-positive mothers to seek further assessment followed by treatment if indicated. Pediatricians report that a lack of training and confidence in addressing positive maternal depression screens are barriers to both screening and referral.10,16,22 The best ways for pediatricians to provide maternal depression education and advice have not been determined. Developing effective approaches could ultimately improve both screening uptake by pediatricians and care uptake by these mothers.10,16

We report on a pilot randomized controlled trial of a novel intervention to motivate screen-positive mothers in pediatric offices to seek further depression assessment and possible care. We hypothesized that an intervention emphasizing motivational and educational messages based on the mother’s maternal role and their children’s well-being would be more effective than a control intervention lacking those aspects. Our objective was to assess the initial effectiveness of a practical pediatric-based intervention in promoting seeking of further assessment and possible care for positive maternal depression screens.

METHODS

DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

We conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing a novel intervention, Motivating Our Mothers (“MOM”), with an active control intervention (“control”) in a general pediatric trainee and faculty practice from August–November 2011. The clinic draws from a large urban, suburban, and rural catchment area in Northern California. While the rate of a positive 2-item depression screen (online supplement), Box 118 in mothers during a previous quality assurance project was 20%, there was no depression screening in the clinic at the time of the trial. The local Institutional Review Board approved the study, and it was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01453790).

Box 1. Measures Used to Assess Eligibility and Primary Outcomes for the MOM Pilot Trial.

Depression Screening Questions and Additional Trial Eligibility Question

|

| Participants were potentially eligible with a “Yes” answer to 1 and/or 2 (sensitivity 74% and specificity 80%)a and a “No” answer to 3. |

Outcome Measure: Intention to Contact Any Resource to Discuss the Symptoms in the Depression Screen

|

| Participants were asked to rank their agreement with these three statements on a scale from 1–7 (Strongly Disagree – Neither Disagree nor Agree – Strongly Agree). The mean across the three items was determined, with higher scores indicating stronger intention. |

|

Outcome Measure: Attempt to Contact any Resource to Discuss the Symptoms in the Depression Screen In the last 2 weeks [or “6 weeks” when administered at the 8 week follow-up], have you tried to contact:

|

| Participants were asked each question separately and asked to respond “Yes” or “No.” For the primary outcome, they were considered to have attempted to seek care if they answered “Yes” to any combination of questions. |

Sensitivity and specificity for the 2-question depression symptom screen were determined by comparison to the Beck Depression Inventory II in a study by Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, Prescott L, Blackman K, Grube L, Meyer W, Tracy K. Screening for depression in an urban pediatric primary care clinic. Pediatrics 2007;119(3):435–443

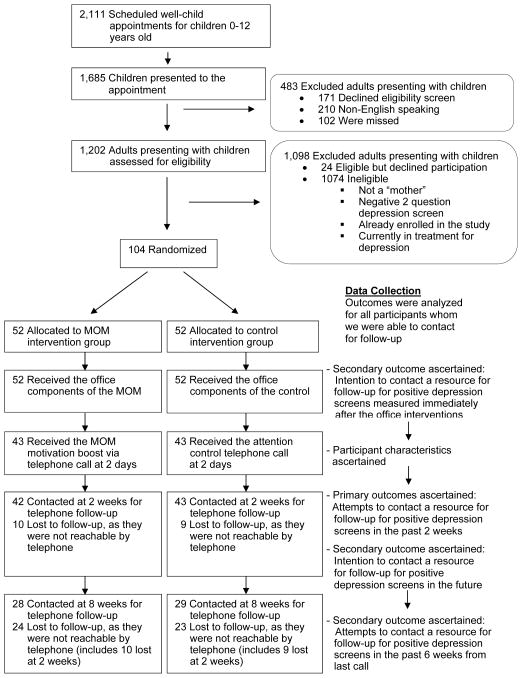

Our recruitment process occurred in 3 steps (Figure 1). First, we identified 2,111 scheduled well-child appointments for children 0–12 years old. Second, we identified for eligibility screening those 1,685 consecutively presenting adults accompanying the children who kept the appointment. Of these, 171 adults declined eligibility screening, 210 were not approached because scheduling data indicated that they were non-English-speaking, and 102 left the clinic before they could be approached. Third, the remaining 1,202 adults were screened for eligibility. To be eligible, mothers were required to be 18–65 years of age, have a positive written 2-item depression screen (administered as part of eligibility screening and not clinical care), and report not receiving professional care for any mental health condition during the previous 12 months. 18,23 Of the 128 mothers meeting study eligibility criteria, 24 (19%) declined participation and 104 (81%) were consented to the study (described as a test of a “long way” versus a “short way” of providing information for parental emotional health) and randomized. We chose the sample size of 104 (with 52 randomized to each group) based on power calculations and to account for dropouts. A statistician not associated with the trial randomized intervention allocation in blocks of 8.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram Showing the Progress of Participants in the MOM Pilot Trial.

The RA (blinded to the intervention randomization) met mothers after the pediatric visit in a private room adjacent to the clinic, administered a brief demographic survey, delivered the assigned intervention using materials enclosed in a previously sealed, opaque envelope, and then left the mothers in the room alone to complete a 3 question post-visit survey on their intention to contact in the future any resource to discuss the symptoms in the screen. Two days later, the RA contacted mothers by telephone to complete the intervention (MOM) or administer a survey (control). Telephone follow-up to assess outcomes was attempted at 2 weeks and 8 weeks by a second RA blinded to group allocation. We allowed up to 6 attempts to contact participants, provided them with call back numbers to reach us at their convenience for all calls, and provided a $10 thank you gift for each contact ($40 total possible). To assess fidelity, the principal investigator observed a 10% subset of RA interactions via a two-way mirror for the clinical interventions and face-to-face with the RA during telephone calls. There were no noted deviations from the scripts.

INTERVENTIONS

Motivating Our Mothers Intervention

We created the MOM intervention protocol based on prior literature in pediatric-based maternal depression studies11,14,15,20,24; motivational interviewing techniques in programs for alcohol cessation25; maternal depression treatment adherence interventions26,27; and obstetric-based maternal depression screening10,15; as well as our clinical experience. The first component was office-based and consisted of a pamphlet and an accompanying structured verbal motivational interaction lasting 5 minutes. The pamphlet contained depression education, including differentiating between screening and diagnosis, and messages meant to motivate mothers to seek further assessment for depression and possible care. All education and motivational messages (both written statements and images) were targeted to mothers and interspersed amongst listings of free, accessible parenting and depression care resources. The targeting focused on destigmatizing depression and included: 1) relating care for depressive symptoms to maintaining child health; 2) using terms such as “low mood” and “maternal depression” rather than depression alone; 3) stating that symptoms are common in mothers; and 4) including parenting resources along with mental health resources. The interaction included repeating the same messages in a discussion style while going over the pamphlet. The second component was a 15-minute semi-structured telephone interaction delivered 2 days later as a motivational “booster.”

Control Intervention

We designed the control as an active control, still providing depression education and advice, including distinguishing between positive screens and a diagnosis of clinically significant depression. However, we did not include in the control those aspects of the MOM which we consider novel and which would not be delivered routinely in adult primary care settings. The control consisted of a pamphlet and accompanying script. One side of the pamphlet was the JAMA Depression Patient Page (2010).28 The other side contained the same care resources provided in the MOM, presented as a list with explanatory headings rather than being interspersed among motivational messages. The control script replaced any terms related to the participants’ role as a mother (e.g. “clinical depression” for “maternal depression”), removed any references to child health (e.g. “your well-being” for “the well-being of yourself and your child”), and was presented without questions meant to stimulate discussion. Control mothers received a telephone survey without additional motivational component at 2 days.

OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Outcomes

We designed the MOM to motivate depression screen-positive mothers in pediatric settings to seek further assessment and possible care for depression and hypothesized that its greatest impact would occur within days to weeks of the initial contact. Therefore, our primary outcome was the proportion of mothers in each group who reported trying to contact any resource to discuss “feeling down, depressed, hopeless or having little interest or pleasure in doing things” (the symptoms in the 2-question screen) at 2 weeks after enrollment. Secondary outcomes included: 1) intention to contact any resource measured immediately after the office-based intervention; 2) the types of depression care resources mothers tried to contact (as reported at 2 weeks); 3) intention to contact any resource in the future (among mothers who had not made an actual attempt to contact any resource to discuss the symptoms in the screen at 2 weeks; and 4) the proportion of mothers in each group who reported trying to contact any resource to discuss the symptoms in the screen by 8 weeks. We assessed outcomes at 8 weeks to capture any participants who needed more time to attempt to seek further assessment for depression and possible care.

Measures

We used standard or adapted instruments to assess outcomes. To facilitate clinic workflow and minimize refusals due to excessive time requirements, we decided to use the available time with participants to deliver the interventions and minimally collect data. At enrollment participants were asked only to provide their age, children’s ages, and if they were currently taking any medications for mood or depression (all of which were part of eligibility screening). Immediately after the intervention, mothers completed a written 3 item measure of intention to contact any resource to discuss the symptoms in the depression screen (Box 1), adapted from Azjen29 and other depression studies.30 An overall mean score across the three items was determined, with higher scores indicating stronger intention (Cronbach’s α = 0.9815). At 2 days via telephone, all mothers provided information on self-identified race/ethnicity, level of education, employment status, household income, access to the internet, health insurance status, medical and mental health provider access, depression treatment history, and the PHQ-8. The PH-8 omits the question on self-harm contained in the PHQ-9; it has equal validity to the PHQ-9 and is commonly used in telephone studies where adequate follow-up for self-harm disclosure cannot be ensured.11,31,32 At 2 and 8 weeks, mothers reported whether or not they had tried to contact each of 6 types of resources (Box 1) to discuss “feeling down, depressed, hopeless or having little interest or pleasure in doing things” since receiving the intervention. The listed resources (medical provider, mental health provider, obstetrician-gynecologist, pediatrician, internet resource, or clergy) have been identified in the literature as those mothers may seek24 and were included in the pamphlets both groups received. If they reported no attempts to contact care resources, they were again asked the intention measure. All mothers were administered the PHQ-8 at 2 and 8 weeks.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We used a X2 test to compare by group the proportion of mothers who had tried to contact care resources (from any of the 6 resources) or not. Intention scale mean scores were compared between groups via Kruskal-Wallis test and t-test. We used Fischer’s exact test to compare the differences in the proportion of participants who tried to contact specific types of resources by group. We used X2 or Fisher’s exact test to compare participant characteristics by group.

RESULTS

PARTICIPANTS

Differences in baseline characteristics between groups were not statistically significant and equal numbers of participants had missing data in each group (Table 1). Overall, the sample was diverse racially/ethnically and socioeconomically. Most mothers were beyond the postpartum period and had access to healthcare. About 10% of mothers reported taking medications for mood; however, none reported seeing a general or mental healthcare professional for a psychiatric condition in the last 12 months.

Table 1.

The Characteristics of the Participating Mothers by Randomized Group

| GROUP, No. (%a) or Mean (SD) | P Value b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOM | CONTROL | TOTAL | ||

| COLLECTED AT ENROLLMENT, No. with Available Data | N = 52 | N = 52 | N = 104 | |

| Mothers Endorsing Both Depression Screening Questions | 28 (54) | 25 (48) | 53 (51) | 0.47 |

| Mothers Endorsing One (Either) Depression Screening Question | 24 (46) | 27 (52) | 51 (49) | |

| Mothers in the Early Postpartum (Any Child < 6 Months) Period | 14 (27) | 15 (29) | 29 (28) | 0.73 |

| Mothers in the Late Postpartum (Any Child 6–12 Months) Period | 10 (19) | 7 (13) | 17 (16) | |

| Mothers Not in the Postpartum (All Children >12 Months) Period | 28 (54) | 30 (58) | 58 (56) | |

| Mean Age (Years) of Mothers | 30.4 (8.1) | 31 (6.4) | 30.7 (7.3) | 0.68 |

| Mean Age (Years) of the Child Receiving Care | 3.6 (3.4) | 4.1 (3.9) | 3.8 (3.7) | 0.52 |

| Mean Total Number of Children Parented by Mothers | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.2) | 0.48 |

| COLLECTED AT THE 2 DAY CALL, No. with Available Data | N = 43 | N = 43 | N = 86 | |

| First Time Mother Met the Pediatrician | 13 (30) | 20 (47) | 33 (38) | 0.12 |

| Mean Scale of Child Care Availability c | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.7 (2.4) | 2.6 (1.3) | 0.71 |

| Mother Living with a Partner | 34 (79) | 26 (60) | 60 (70) | 0.06 |

| Has Internet Access | 39 (91) | 34 (79) | 73 (85) | 0.23 |

| Has Any Kind of Health Insurance | 38 (88) | 39 (91) | 77 (89) | 1.00 |

| Has a Primary Care or Mental Health Professional | 30 (70) | 34 (79) | 64 (74) | 0.46 |

| Race/Ethnicity of Mothers | ||||

| Non-Hispanic, White | 13 (30) | 10 (23) | 23 (27) | 0.75 |

| Non-Hispanic, Black | 9 (21) | 8 (19) | 17 (20) | |

| Non-Hispanic, Other | 9 (21) | 9 (21) | 18 (21) | |

| Hispanic, Any Race | 12 (28) | 16 (37) | 28 (32) | |

| Level of Education of Mothers | ||||

| Partial and Completed High School | 20 (47) | 14 (32) | 34 (39) | 0.69 |

| Partial College and Above | 23 (53) | 29 (68) | 52 (60) | |

| Employment of Mothers | ||||

| Employed Outside of the Home | 17 (39) | 13 (30) | 30 (35) | 0.84 |

| Out of Work, Homemaker, or Student | 26 (61) | 30 (70) | 56 (65) | |

| Yearly Household Income in Dollars | N = 41 | N = 42 | N = 83 | |

| <10,000 | 14 (34) | 15 (35) | 29 (35) | 0.31 |

| 10,000 – 34,999 | 17 (42) | 18 (43) | 25 (42) | |

| 35,000 – >100,000 | 10 (24) | 9 (22) | 19 (23) | |

| Mothers’ History of Depression | N = 43 | N =43 | N = 86 | |

| Has Ever Been Told They Have Depression by a Professional | 21 (49) | 24 (56) | 45 (52) | 0.52 |

| Were Mothers When Told They Had Depression | 16 (37) | 17 (40) | 33 (38) | 0.75 |

| Mothers’ Depression Symptoms | N = 42 | N = 43 | N = 85 | |

| Mean PHQ 8 Scoresd | 10.4 (5.5) | 11.1 (5.7) | 10.8 (5.5) | 0.54 |

| PHQ 8 Score 0–4 | 6 (14) | 7 (16) | 13 (15) | 0.82 |

| PHQ 8 Score 5–9 | 12 (29) | 11 (26) | 23 (27) | |

| PHQ 8 Score 10–14 | 15 (35) | 12 (28) | 27 (32) | |

| PHQ 8 Score 15–19 | 5 (12) | 9 (21) | 14 (17) | |

| PHQ 8 Score 20–24 | 4 (10) | 4 (9) | 8 (9) | |

All percentages are rounded up to the nearest whole integer

Test were by X2 or Fisher’s exact tests depending on the cell size and two-tailed t-test for means

Scale: 1 all of the time, 2 most of the time, 3 some of the time, 4 a little of the time, 5 none of the time

Scale: summative Score with range 0–24

OUTCOMES

Primary Outcome

Ten MOM and 9 control mothers were not reached by telephone at 2 weeks post-intervention, despite up to 6 attempts to contact them. Of the 42 MOM and 43 control mothers who we were able to reach, the proportion of MOM mothers who reported that they tried to contact any of 6 resources to discuss the symptoms in the depression screen was greater than control mothers (difference 20.3%, 95% CI, −0.1% to −38.5%, Table 2). The number needed to treat (NNT) to avert a single case of “not trying to contact a resource for follow-up” was 4.9 (95% CI, 2.4 – 290). We performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to mothers with baseline PHQ-8 scores of 10 or greater, as these mothers would be more likely to receive a diagnosis of depression and have a symptom burden which may hinder motivation. We found that within this more symptomatic subgroup, MOM mothers were more likely to attempt to contact any resource than controls, but the difference was not significant (75% versus 54.6%, P = 0.17). This compares to a more robust difference among mothers with PHQ-8 scores less than or equal to 9 (80% versus 43.8%, P = 0.066).

Table 2.

Number of Mothers Reporting Attempts to Contact Resources for Follow-Up of Positive Depression Screens by Group and Measured at Two Weeks Post-Intervention

| RESOURCES OF CARE FOR DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS No. with Available Data | GROUP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOM (N=42) | Control (N=43) | |||

| N | % of Totala (95% Confidence Interval) | N | % of Totala (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Any Resource | 31 | 74 (61–87) | 23 | 53 (39–68) |

| Mental Health Professional b (with or without other resources) | 14 | 33 (19–48) | 5 | 11 (2–21) |

| Medical Provider c (with or without other resources) | 6 | 14 (4–25) | 9 | 21 (9–33) |

| Clergy d (with or without other resources) | 4 | 10 (1–18) | 6 | 14 (4–24) |

| Internet Site only | 7 | 17 (5–28) | 3 | 7 (0–15) |

Percentages rounded to nearest whole number

Mental Health Professional = “Therapist, Counselor, Psychologist, Psychiatrist, or Social Worker”

Medical Provider = “Doctor, Nurse Practitioner, Physician Assistant, or Obstetrician/Gynecologist”

Clergy = “Pastor, Priest, Rabbi, Imam or Spiritual Counselor”

p = 0.052 for X2 test comparing any attempts versus no attempts to seek resources for care between intervention and control (the primary outcome).

p = 0.05 for Fisher’s exact test comparing the distribution of attempts to seek care between intervention and control.

Secondary Outcomes

In the post-visit surveys administered in the office (n=104), intention to contact any resource to discuss the symptoms in the depression screen was significantly higher in MOM mothers (mean score 5.22; 95% CI, 4.76–5.68) than control mothers (mean score 4.00; 95% CI, 3.46–4.55)(P = 0.009). At 2 weeks post-intervention (n=85), many mothers reported attempts to contact more than one type resource to discuss the symptoms in the depression screen. No mothers indicated pursuing any resource other than those included in the survey. In general, MOM mothers were more likely to try to contact mental health providers and less likely to try to contact medical professionals or clergy than control mothers (P = 0.05; Table 2). In those mothers who did not report attempts to contact any resource by 2 weeks (n=31), MOM mothers reported higher intention to do so in the future (mean score, 4.39; 95% CI, 3.52–5.27) than control mothers (mean score, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.47–3.23)(P = 0.001). At 8 weeks post-intervention, we were able to reach 28 MOM and 29 control mothers. Few mothers (3 MOM and 2 control) who had not tried to contact any resource to discuss the symptoms in the depression screen at 2 weeks reported doing so by 8 weeks. The proportion of MOM mothers who reported that they tried to contact any resource by 8 weeks (89%) was greater than control mothers (59%)(P = 0.015). The NNT to avert a single case of “not trying to contact a resource for follow-up” was 3.26 (95% CI, 1.95 – 10.65).

DISCUSSION

In this pilot randomized control trial, we found that mothers receiving the targeted MOM intervention were more likely to try to contact a resource to discuss symptoms in the depression screens than controls. In addition, as ancillary evidence of intervention effect, MOM mothers had greater intention to contact a resource for screen follow-up, whether they actually tried to contact a resource or not, and tended to try to contact traditional mental health sources of care more than controls. Our primary and ancillary findings together suggest that pediatric-specific messages demonstrate promise in motivating mothers with depressive symptoms to seek care for those symptoms. These messages may also reduce stigma associated with seeking care from mental health providers. Our pilot results provide a critical first step in eventually linking maternal depression screening in pediatrics9,11,20,24 to effective but underused maternal depression treatment programs10, thereby maximizing the opportunity presented in pediatric settings to improve care of maternal depression. Given advances in epigenetic science demonstrating the long lasting effects of environmental stress on child health33, the goal of eventually improving maternal depression is of utmost importance in ensuring the health of generations of pediatric patients.

We identified 4 related studies investigating pediatric-based referrals for depression care in samples of depression screen-positive mothers not exclusively in the postpartum period. In 2 studies, the method of referral was not specified and the proportion of mothers who intended or reported seeking care was 59%21 and 46%.34 In two studies, both using the “5 A’s” approach to referral, one did not report uptake of referrals10 and one found that 90% of parents who agreed to be proactively contacted by central referral telephone line were assisted, while only 5% of parents who were asked to call the line themselves chose to do so.11 Most other studies investigating uptake of referral for maternal depression care from pediatric practices are exclusive to the postpartum period, and have found uptake to be varied and highest for onsite services.9,20 Mothers’ uptake of referral to maternal depression care from peri-and postpartum care providers is similarly varied depending on the resource to which they were referred.7,35

In this context, our study has 3 novel aspects. First, it was designed specifically to assess the effect of a pediatric-based intervention on mother’s motivation to contact resources for follow-up of a positive depression screen. Second, the MOM was designed, and our study setting selected, so that our results would strongly encourage further testing and implantation of the MOM in general pediatric practices and for the diverse groups of mothers they serve. Third, we were able to describe mothers’ preferences for depression assessment and care resources after they received a menu of accessible services.

Our study extends prior work9–11,20,21,34 by identifying high rates of attempting to contact generally available community-based resources for follow-up of positive depression screens in mothers referred from a general pediatric clinic. Furthermore, MOM mothers’ greater attempts at contact compared to control mothers may demonstrate that mothers respond preferentially to depression education and advice targeted specifically to them. Whether the MOM can be delivered by clinic staff (rather than trained research assistants) needs to be explored in future studies. However, our results bolster current evidence for successfully motivating depression screen-positive mothers in pediatric settings to seek further evaluation for their symptoms, and add a way to do so that is practical in the context of general pediatric clinic resources.

In contrast to other studies34,35 we found that mothers with depressive symptoms tended to try to contact more than one resource, including combinations of formal services, such as mental and medical providers, and informal services like clergy and the internet. Only one mother reported attempting to contact a pediatrician. We can only speculate about the explanation, but many mothers had been diagnosed with depression in the past and had access to care. Therefore, they may have been aware of resources outside of those that a pediatrician could direct them toward. Lastly, mothers in the MOM group preferred mental health professionals more than would have been expected from preferences reported in previous studies, and more than control mothers. We suspect that our targeting of messages, with a focus on destigmatization of depressive symptoms and presenting further assessment and possible treatment of depression as a means to improve child health, could have led MOM mothers to be more accepting of depression as a cause of their symptoms. Therefore, they were more likely to consider mental health providers as appropriate sources of help.

Our results should be interpreted in light of various study limitations. The sample size was limited. However, this pilot trial was designed as an initial test of the concept of motivating mothers to seek follow-up for depression screens in pediatric settings and of feasibility and initial effectiveness of the MOM in doing so, and not as a means of estimating a definitive effect size for the dichotomized outcome overall or within subgroups. Furthermore, taken as a whole, our results indicate an effect of the MOM on mother’s attempts to contact resources to discuss the symptoms expressed in the depression screen despite the small sample size. The individuals who were eligible but refused to participate or who received the interventions but were lost to follow-up despite retention efforts, could be less likely to attempt contact. Generalizability is further limited by the single site design. In addition, because the same team of RAs was used to deliver both the MOM and control interventions, there were opportunities for cross-contamination, particularly inadvertent delivery of MOM elements to control patients. However, investigator observation of a 10% sample of RA interactions revealed no deviations from protocol, and in any case such cross-contamination would tend to bias the observed intervention effect towards the null. The motivational interviewing components of the MOM made interactions between the RA and MOM mothers necessarily longer than those in the control. Differences in length of interaction alone may account for some of the difference in outcome.

In summary, we have demonstrated that mothers within and beyond the postpartum period can be screened for depression in a general pediatric clinic and those with positive screens can be motivated to seek follow-up for those screens. We have also demonstrated the initial effectiveness of the MOM in increasing these mothers’ attempts to contact resources to discuss the symptoms evaluated in the screens. There are significant systematic barriers to maternal depression care utilization.1,7,8,14,15 The pediatric setting is not currently the place to address those barriers36, even though it may become so as the nation turns toward organizing family-centered medical homes. Instead, our goal is to realize the potential of pediatric settings in identifying mothers with depression who would otherwise not be identified or treated, including mothers with ongoing symptoms who have lost contact with treating providers, and motivating them to engage, to the extent possible, with effective but underutilized maternal depression evaluation and care programs. This study provides valuable information for others considering pediatric-based interventions with similar aims. Our results encourage larger effectiveness trials both to generate more precise estimates of the intervention’s impact and to explore potential areas for intervention improvement and implementation.

Supplementary Material

WHAT’S NEW.

Treating maternal depression may improve maternal and child well-being. Based on results of this pilot trial, the MOM intervention may be a promising method for pediatricians to screen mothers for depression and motivate them to seek further assessment and support.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH) through grants #UL1 TR000002 and 1K23MH101157-01A1, and by a grant from the University of California Davis Department of Pediatrics Children’s Miracle Network. Dr. Fernandez y Garcia was supported by the University of California Davis, Office of the Dean, as an Institutional Scholar. Dr. Kravitz was supported by 5K24MH07275605. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. All of the authors are without any potential conflicts of interest involving the work under consideration for publication (from initial conception to present), any relevant financial activities outside the submitted work (over the 3 years prior to submission), or any other relationships or activities that readers could perceive to have influenced or that give the appearance of potentially influencing what is written in the submitted work (during the 3 years prior to submission). We would like to thank Daniel Joseph Tancredi, Ph.D., University of California Davis Department of Pediatrics and Center for Healthcare Policy and Research, for his assistance in randomization procedures and Colleen Tweed Wong, M.F.T., for assistance in enrolling patients and delivering interventions. We would also like to thank University of California Davis Department of Neonatal Medical Social Workers, specifically Tamara Louis, M.S.W., Courtney Corbitt, M.S.W., and Julie Weckstein, L.C.S.W, for their assistance in editing the community resources included in both intervention guides.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Erik Fernandez y Garcia, Department of Pediatrics, School of Medicine, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA

Jill Joseph, Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA

Machelle D. Wilson, University of California, Davis, Clinical and Translational Science Center, Department Public Health Sciences, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA

Ladson Hinton, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, School of Medicine University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA

Gregory Simon, Group Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA

Evette Ludman, Group Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA

Fiona Scott, School of Medicine, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA

Richard L. Kravitz, Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA

References

- 1.Witt WP, Keller A, Gottlieb C, et al. Access to adequate outpatient depression care for mothers in the USA: a nationally representative population-based study. J Behav Heatlh Serv Res. 2011;38(2):191–204. doi: 10.1007/s11414-009-9194-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davé S, Petersen I, Sherr L, Nazareth I. Incidence of maternal and paternal depression in primary care: a cohort study using a primary care database. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(11):1038–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Scharfstein D, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and children’s receipt of healthcare in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):306–314. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chemtob CM, Gudiño OG, Laraque D. Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in pediatric primary care: association with child maltreatment and frequency of child exposure to traumatic events. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(11):1011–1018. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pemberton CK, Neiderhiser JM, Leve LD, et al. Influence of parental depressive symptoms on adopted toddler behaviors: an emerging developmental cascade of genetic and environmental effects. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(4):803–818. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky DJ, et al. Children of depressed mothers 1 year after remission of maternal depression: findings from the STAR*D-Child study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(6):593–602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith MV, Shao L, Howell H, Wang H, Poschman K, Yonkers KA. Success of mental health referral among pregnant and postpartum women with psychiatric distress. Gen Hosp Psych. 2009;31(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson AL, Dietrich AJ, Prazar G, Hurley J. Brief maternal depression screening at well child visits. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):207–216. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker-Ericzen MJ, Mueggenborg MG, Hartigan P, Howard N, Wike T. Partnership for women’s health: a new-age collaborative program for addressing maternal depression in the postpartum period. Families, Systems & Health. 2008;26(1):30–43. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinberg E, Smith MV, Morales MJ, Claussen AH, Smith DC, Perou R. Improving women’s health during internatal periods: developing an evidence-based approach to addressing maternal depression in pediatric settings. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15(6):692–703. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson A, Gaffney C. Parental depression screening for pediatric clinicians: an implementation manual. The Common Wealth Fund; 2007. [Accessed January 3, 2014]. Found at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Publications/Fund-Manuals/2007/Apr/Parental-Depression-Screening-for-Pediatric-Clinicians--An-Implementation-Manual.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatricians provide majority of care to children: survey. American Academy of Pediatrics News Research Update. 2001 Oct;19:154. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heneghan AM, Silver EJ, Bauman LJ, Stein RE. Do pediatricians recognize mothers with depressive symptoms? Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1367–1373. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heneghan AM, Mercer M, DeLeone NL. Will mothers discuss parenting stress and depressive symptoms with their child’s pediatrician? Pediatrics. 2004;113:460–467. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feinberg E, Smith MV, Naik R. Ethnically diverse mothers’ view on the acceptability of screening for maternal depressive symptoms during pediatric well-child visits. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):780–797. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heneghan AM, Morton S, DeLeone NL. Pediatricians’ attitudes about discussing maternal depression during a paediatric primary care visit. Child Care Health Development. 2007;33(3):333–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hagen JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. Bright Futures: Guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents (3rd edition) Elk Grove, Il: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, et al. Screening for depression in an urban pediatric primary care clinic. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):435–443. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gjerdingen D, Crow S, McGovern P, Miner M, Center B. Postpartum depression screening at well-child visits: validity of a 2 question screen and the PHQ-9. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):63–70. doi: 10.1370/afm.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Kitzman HJ, Wadkins HI, Conwell Y. Detection of postpartum depressive symptoms by screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 pt 1):551–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Needlman R, Walders N, Kelly S, Higgins J, Sofranko K, Dennis Drotar. Impact of screening for maternal depression in a pediatric clinic: an exploratory study. Ambulatory Child Health. 1999;5:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Head JG, Storfer-Isser A, O’Connor KG, et al. Does education influence pediatricians’ perceptions of physician-specific barriers for maternal depression? Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2008;47(7):670–678. doi: 10.1177/0009922808315213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson AL, Dietrich AJ, Prazar G, Hurley J, Tuddenham A, Hedberg V. Two approaches to maternal depression screening during well child visits. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(3):169–176. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascoe JM, Lee M, Specht SL, et al. Mothers with positive or negative depression screens evaluate a maternal resource guide. J Pediatr Health Care. 2010;24(6):378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandez WG, Hartman R, Olshaker J. Brief interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use among military personnel: lessons learned from the civilian experience. Military Medicine. 2006;171:538–543. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grote NK, Zuckoff A, Swartz H, Bledsoe SE, Geibel S. Engaging women who are depressed and economically disadvantaged in mental health treatment. Soc Work. 2007;52(4):295–308. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKay MM, Bannon WM., Jr Engaging families in child mental health services. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2004;13(4):905–921. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torpy JM, Burke AE, Glass RM. Depression. JAMA Patient Page. JAMA. 2010;3030(19):1994. doi: 10.1001/jama.303.19.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azjen I. [Accessed January 2, 2014];Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. Found at http://people.umass.edu/azjen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf.

- 30.Mo PKHM, Mak WWS. Help-seeking for mental health problems among Chinese: the application and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2009;44:675–684. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuire LC, Strine TW, Allen RS, Anderson LA, Mokdad AH. The Patient Health Questionnaire 8: current depressive symptoms among US older adults, 2006 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:324–334. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181953bae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuehn BM. AAP:Toxic stress threatens kids’ long-term health. JAMA. 2014;312(6):585–586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson CM, Robins CS, Greeno CG, et al. Why lower income mothers do not engage with the formal mental health care system: Perceived barriers to care. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(7):926–943. doi: 10.1177/1049732306289224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woolhouse H, Brown S, Krastev A, Perlen S, Gunn J. Seeking help for anxiety and depression after childbirth: results for the Maternal Health Study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Campbell AT, Mounts KO, McInerny TK. Legal and ethical considerations: risks and benefits of postpartum depression screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):123–128. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.