Abstract

FemABX peptidyl transferases are involved in non-ribosomal pentaglycine interpeptide bridge biosynthesis. Here, we characterized the phenotype of a Staphylococcus carnosus femB deletion mutant, which was affected in growth and showed pleiotropic effects such as enhanced methicillin sensitivity, lysostaphin resistance, cell clustering, and decreased peptidoglycan cross-linking. However, comparative secretome analysis revealed a most striking difference in the massive secretion or release of proteins into the culture supernatant in the femB mutant than the wild type. The secreted proteins can be categorized into typical cytosolic proteins and various murein hydrolases. As the transcription of the murein hydrolase genes was up-regulated in the mutant, they most likely represent an adaption response to the life threatening mutation. Even though the transcription of the cytosolic protein genes was unaltered, their high abundance in the supernatant of the mutant is most likely due to membrane leakage triggered by the weakened murein sacculus and enhanced autolysins.

Keywords: Cytosolic proteins, FemB, Microbiology, Peptidoglycan, Secretome, Staphylococcus carnosus

1 Introduction

In many organisms where the classical secretion systems are not involved in the excretion of cytosolic proteins, the “non-classical protein secretion” takes place. Proteins undergoing this secretion show no simple sequence motifs except that they are more disordered in structure than those remaining in the cytoplasm [1]. In Staphylococcus aureus, over 20 typical cytosolic proteins are excreted, starting already in the exponential phase and it appears to be more pronounced in clinical isolates than in the non-pathogenic staphylococcal species [2,3]. Various S. aureus mutants have been analyzed with respect to the release of cytoplasmic proteins. For example, in the atl (major autolysin) mutant, cytosolic proteins were hardly found in the supernatant, but were entrapped within the huge cell clusters of this mutant [2]. In the wall teichoic acid deficient tagO mutant, with its increased autolysis activity, excretion of cytosolic proteins was increased compared to the wt, confirming the importance of autolysis in excreting cytosolic proteins.

Here, we investigated a femB deletion mutant of Staphylococcus carnosus, which has a shortened glycine interpeptide bridge in the murein structure. The factors essential for the expression of methicillin resistance (fem), encode the FemABX peptidyl transferases involved in non-ribosomal pentaglycine interpeptide bridge biosynthesis [4,5]. While femX is essential, Tn mutants, but no deletion mutants, could be generated in S. aureus. Both mutants showed a reduced peptidoglycan (PGN) cross linking and glycine content, decreased lysostaphin susceptibility, reduced whole-cell autolysis, increased sensitivity to β-lactam antibiotics [6], an aberrant placement of cross walls, and stunted cell separation [7] showing key functions of the pentaglycine interpeptide bridge.

We could construct a femB deletion mutant in S. carnosus in which the femAB operon is orthologous to that of S. aureus [8]. The most striking phenotype of the femB mutant was the massive release of proteins into the culture supernatant. The excreted proteins could be classified into two groups: those secreted via the canonical Sec pathway, and those representing typical cytosolic proteins lacking a signal sequence. The results suggest that the release of cytosolic proteins is due to the altered PGN structure, which makes the cell envelope leaky enough for the release of cytosolic proteins.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and oligonucleotide primers

S. carnosus strains TM300 [9,10], its deletion mutant ΔfemB::ermB, the complementary mutant ΔfemB::ermB (pPSHG5femB), Escherichia coli strain DH5α [11], and Micrococcus luteus DSM 20030T [12,13] were cultivated at 37°C and shaken in basic medium (BM; 1% soy peptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, 0.1% glucose, and 0.1% K2HPO4; pH 7.4). When appropriate, BM was supplemented with 10 μg/mL chloramphenicol, 2.5 μg/mL erythromycin, or 100 μg/mL ampicillin. Oligonucleotide primers used for cloning and Northern blot analysis are listed in Supporting Information Table 1.

2.2 Preparation of extracellular proteins for preparative 2DE

Cells were harvested at a comparable time point of the growth phase (Fig.1 and Supporting Information Table 2) by centrifugation at 9000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Extracellular proteins in the culture supernatant were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid overnight at 4°C, subsequently pelleted by centrifugation at 9000 × g for 40 min at 4°C, and washed eight times with ethanol. The protein pellet was dried and resuspended in an appropriate volume of rehydration buffer consisting of 8 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% w/v CHAPS, 1% DTT, and 0.7% pharmalyte, pH 3–10 and centrifuged at 16 000 × g for 15 min at room temperature. The protein concentration was determined using Bradford assay according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bio-Rad Laboratories, München, Germany). For 2D PAGE, 500 μg of secreted proteins was applied.

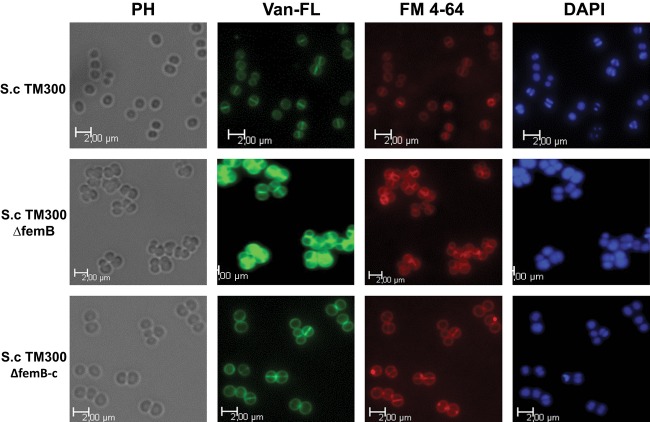

Figure 1.

Construction of the femB deletion mutant and complementation. (A) Location of the fem operon in the chromosome of S. carnosus and (B) the femB deletion mutant (ΔfemB::ermB). (C) Complementation plasmid pPSHG5femB. cat: chloramphenicol resistance gene; ermB: erythromycin resistance gene; trpA, trpB: tryptophan synthetase alpha and beta chain; h.p.: hypothetical protein.

2.3 Preparation of cytosolic proteins for preparative 2DE

Cells of 40 mL cultures were harvested at two time points (Fig.1 and Supporting Information Table 2) and centrifuged for 15 min at 9000 × g at 4°C. The pellets were then resuspended in 1 mL ice-cold TE buffer (10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA; pH 7.5) and disrupted by homogenization using glass beads and TissueLyser (Qiagen) twice for 30 s at 30 Hz. To remove cell fragments and insoluble proteins, the cleared lysate was centrifuged for 20 min at 20 000 × g at 4°C. The protein concentration was determined using Bradford assay. For 2D PAGE, 500 μg was used and mixed with rehydration buffer to a final concentration containing 8 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% w/v CHAPS, 1% DTT, and 0.7% pharmalyte (pH 3–10).

2.4 2D-PAGE and computational analysis

Protein patterns of the S. carnosus wt and the femB mutant were compared visually and quantitatively with Delta2D software (DECODON) after 2D PAGE was performed as described in earlier studies [14,15]. For each condition, three independent experiments were performed. Only statistically reproducible differences were included in the results. For identified proteins, several analyses were performed. The theoretical localization of proteins was predicted with PSORT (http://www.psort.org/psortb/), the prediction of N-terminal signal sequences was performed with SignalP version 3.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/), and the non-classical secretion of proteins was predicted with SecretomP version 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SecretomeP/). The theoretical molecular weight (MW) and pI for mature proteins without any signal sequence were calculated using the pI/MW tool (http://www.expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html).

2.5 Supporting information

Construction of the S. carnosus femB deletion mutant, construction of femB expression plasmid, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, purification and analysis of PGN, analysis of proteins in the supernatant, analysis of membrane and cytosolic fractions by SDS-PAGE, Western blot analysis, fluorescence microscopy, RNA isolation and northern blot analysis, and protein identification by MS are described as Supporting Information.

3 Results

3.1 Construction and characterization of the femB deletion mutant in S. carnosus TM300

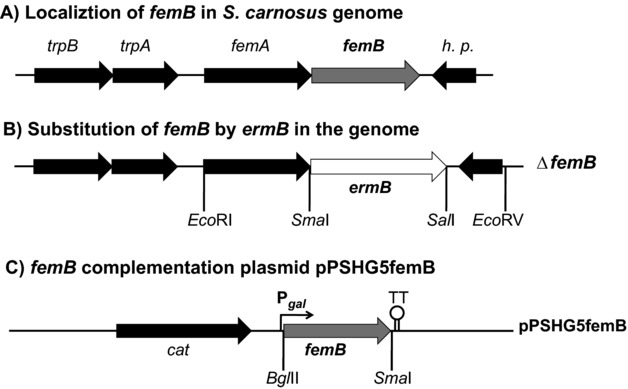

FemB (Sca_1020) of S. carnosus TM300 revealed 82% identity and 92% similarity to FemB (SAOUHSC_01374) of S. aureus NCTC 8325 and the femAB genes are organized in an operon downstream of the tryptophan synthase genes (trpBA) (Fig.1A). In S. carnosus TM300, the deletion mutant was created by replacing femB with an erythromycin cassette (ermB) [16]. The femB mutant was complemented with the plasmid pPSHG5femB, which was constructed by cloning femB under the control of a galactose-inducible promoter (Fig.1B). Growth deficiency of the femB mutant could be complemented by pPSHG5femB (Fig.1C and Fig.2A). It also showed an increased susceptibility to methicillin (Fig.2B) but high resistance to lysostaphin, with a more than 3000-fold increase in the MIC values from 0.01 to 32 μg/mL. This is in agreement with lysostaphin's cleavage preference for the pentaglycine interpeptide bridge [17].

Figure 2.

Comparative phenotypic features of S. carnosus, its femB mutant, and the complementary mutant. (A) Growth was severely affected in the femB mutant; arrow indicates sampling time for analysis. (B) Agar diffusion assay showing femB mutant methicillin susceptibility. (C) SDS-PAGE of culture supernatant proteins; cells were cultivated for 13 h in the presence of 0.25% galactose. wt: wild type; S.c. TM300; ΔfemB: femB deletion mutant; ΔfemB-c: mutant complemented with pPSHG5femB; M: marker proteins.

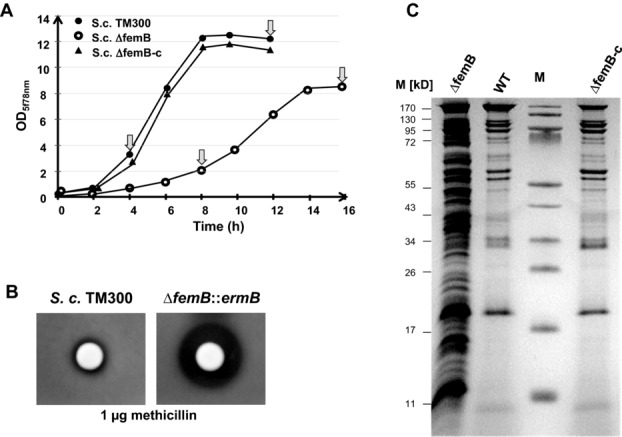

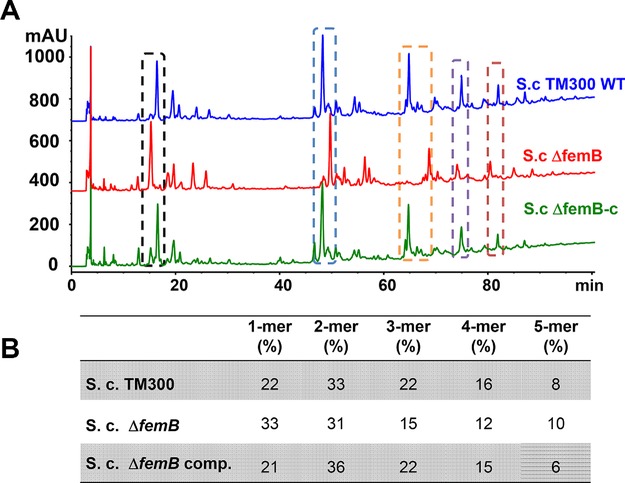

Phase and fluorescence microscopic analyses showed that cells of the femB mutant are clustered (Fig.3) suggesting a defect in daughter cell separation. Vancomycin staining (Van-FL) revealed a massive accumulation of fluorescence intensity in the femB mutant in the septum region suggesting that the degree of cross-linking of the PGN network was considerably decreased. As with vancomycin, fluorescence intensity with FM 4–64, a cell impermeant membrane stain, was increased in the septum region of the femB mutant, indicating increased penetration of the dye through the cell wall to the membrane site (Fig.3). Ultimately, DNA-staining with DAPI revealed enlarged DNA areas (nucleoid) in the mutant, which could have resulted from decreased chromosomal condensation (Fig.3). In all microscopic images, the femB mutant cells were enlarged, the average cell diameter was 132% increased compared to the wt; while the complementary mutant ΔfemB (PSHG5femB) closely resembles the wt (Fig.3). Comparative HPLC analysis of PGN isolated from the wt, ΔfemB, and the complementary mutant showed that the mutant contained roughly 50% more of monomeric fragments than the wt, and less tri- and tetramer fragments (Fig.4), which indicates a decreased level of PGN crosslinking.

Figure 3.

Microscopic analysis of S. carnosus and its femB mutant. S.c. TM300ΔfemB forms large cell clusters. Cell wall staining with vancomycin shows intensive fluorescence particularly in the septum and membrane staining (FM 4–64) revealed intensified florescence. The DAPI stained nucleoid shows significant enlargement, whereas the wt (upper row) and the complementary mutant (lower row) looked roughly similar.

Figure 4.

Peptidoglycan composition is altered in the S. carnosusΔfemB strain. (A) HPLC analysis of mutanolysin-digested PGN of the wild-type strain of S. carnosus TM300, the mutant S.cΔfemB, and the complemented mutant. (B) Eluted UV-absorbing peaks were integrated, and the corresponding muropeptides highlighted by the dotted area in (A) were quantified as a percentage of the total area of identified peaks. Dotted areas represent monomers to pentamers (left to right).

3.2 The femB mutant is characterized by the high abundance of secreted proteins

Another eye-catching phenotype of the femB mutant was the drastic increase of secreted proteins (Fig.2C). Quantitative analysis of these proteins in the exponential and stationary growth phases revealed that the protein content in the femB mutant was always roughly 5 to 6 times higher than in the wt, while the cytosolic protein content remained more or less the same (Table1 and Supporting Information Fig. 1). Comparative secretome analysis was performed to determine protein abundance in the supernatant of the femB mutant. Due to the growth rate difference (Fig.2A), protein samples for 2D-PAGE were taken at the exponential growth phase after 4 h (wt) and 8 h (femB mutant), as well as after 12 h (wt) and 16 h (femB mutant) for the stationary growth phase (Fig.2A and Supporting Information Fig. 2). Protein spots of each of three 2D gels of the wt and the femB mutant were analyzed by mass spectroscopy and 82 different proteins could be identified and quantified (Supporting Information Table 2).

Table 1.

Protein content in supernatant and cytosol of wt and femB mutant

| Strains | Harvest- time | OD578a) | Protein amount (μg/mL cell culture) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supernatant a) | Cytosol a) | |||

| Exponential growth phase | ||||

| S. c. WT | 4 h | 4.5 | 0.87 | 22.60 |

| S. c. ΔfemB | 8 h | 3.3 | 5.74 | 22.28 |

| Stationary growth phase | ||||

| S. c. WT | 12 h | 12.1 | 2.20 | 29.40 |

| S. c. ΔfemB | 16 h | 9.23 | 10.31 | 25.48 |

Indicates the mean values of the three measurements.

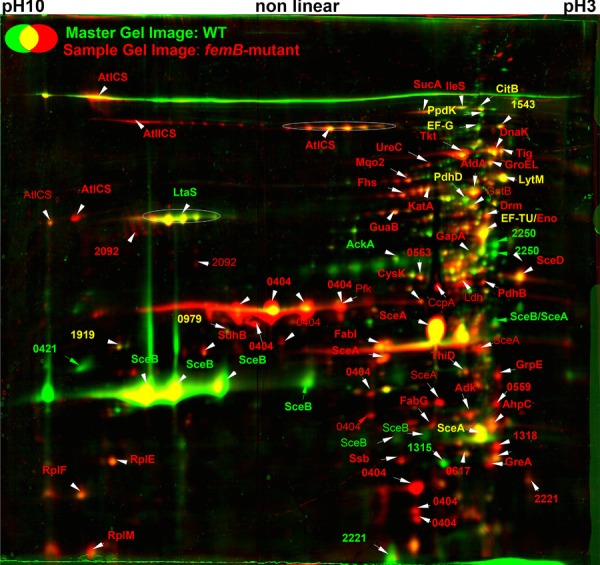

Though the overall protein pattern was similar, the femB mutant showed a much higher protein quantity in most of the spots. Protein amounts were therefore compared using the Delta2D software (DECODON) for better visualization (Fig.5). Proteins in the wt were designated green and in the femB mutant red. Equal amount of proteins would then result in yellow spots. Thirty six selected protein spots showing the most significant differences in intensity between the wt and femB mutant were identified and characterized (Tables2 and 3).

Figure 5.

Differential 2D-PAGE of secretomes of S. carnosus wt and its femB mutant after 12 and 16 h incubation, respectively. Proteins (500 μg) of the culture supernatant were separated by 2D-PAGE and stained with colloidal coomassie silver blue and compared using the Delta2D image analysis software. The secretome of the WT (green) and femB mutant (red) were overlaid using Delta2D software. Dominant spots retain their colors and equally distributed ones showed yellow color. Protein spots were identified by MALDI-TOF MS.

Table 2.

Proteins less abundant in the secretome of the femB mutant

| Proteina)b) | Function | S. carnosus TM300 gene ID | S. aureus N315 homolog gene ID | S. aureus COL homolog gene ID | Ratio femB mutant/wild typec) | Signal sequenced) | MW (kDa)f) | pIf) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular proteins | ||||||||

| SceB1 | SceB precursor | Sca_1790 | SA2093 ssaA | SACOL2291 | −8.0 | + | 25.3 | 7.9 |

| SceB2 | SceB precursor | Sca_1790 | SA2093 ssaA | SACOL2291 | −5.3 | + | 25.3 | 7.9 |

| SceB3 | SceB precursor | Sca_1790 | SA2093 ssaA | SACOL2291 | −2.8 | + | 25.3 | 7.9 |

| Sca0421 | Hypothetical protein | Sca_0421 | − | − | −6.2 | + | 34.5 | 9.7 |

| Sca2250 | Hypothetical protein | Sca_2250 | − | − | −9.2 | + | 37.2 | 4.5 |

| Membrane localization | ||||||||

| LtaS1 | Polyglycerol phosphate synthase LtaS | Sca_0366 | SA0674 | SACOL0778 | −4.2 | − | 74.3 | 9.0 |

| LtaS2 | Polyglycerol phosphate synthase LtaS | Sca_0366 | SA0674 | SACOL0778 | −3.5 | − | 74.3 | 9.0 |

| LtaS3 | Polyglycerol phosphate synthase LtaS | Sca_0366 | SA0674 | SACOL0778 | −2.6 | − | 74.3 | 9.0 |

| Cytosolic proteins | ||||||||

| AckA | Acetate kinase homolog | Sca_1316 | SA1533 | − | −5.8 | − | 43.6 | 5.5 |

| Sca1315 | Hypothetical protein | Sca_1315 | SA1532 | SACOL1759 | −2.2 | − | 18.8 | 5.2 |

Subcellular localization was predicted using PSORTb.

Several identified spots of one protein were numbered.

Volume ratios in the range of 1 to ∞ indicate an increase of the volume of the respective protein spot and volume ratios in the range –1 to –∞ indicate a decrease of the volume of the respective protein spot. Only volume ratios ≥ 2 and ≤ −2 were defined as significant changes between the different strains.

Typical signal sequence was predicted using SignalP.

Non-classical secretion was predicted using SecretomeP.

Theoretical molecular weight (MW) and pI were calculated for mature proteins without signal sequence using MW/pI tools.

Superscripts 1–3 refer to differently processed protein spots.

Table 3.

Proteins more abundant in the secretome of the S. carnosus femB mutant

| Proteina)b) | Function | S. carnosus TM300 gene ID | S. aureus N315 homolog gene ID | S. aureus COL homolog gene ID | Ratio femB mutant/wild typec) | Signal sequenced) | Non-classical secretione) | MW (kDa)f) | pIf) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular proteins | |||||||||

| AtlCS2 | Major autolysin precursor | Sca_0659 | SA0905 atlA | SACOL1062 | 9.8 | + | − | 133.1 | 9.2 |

| AtlCS3 | Major autolysin precursor | Sca_0659 | SA0905 atlA | SACOL1062 | 8.8 | + | − | 133.1 | 9.2 |

| AtlCS4 | Major autolysin precursor | Sca_0659 | SA0905 atlA | SACOL1062 | 8.8 | + | − | 133.1 | 9.2 |

| AtlCS5 | Major autolysin precursor | Sca_0659 | SA0905 atlA | SACOL1062 | 8.6 | + | − | 133.1 | 9.2 |

| AtlCS6 | Major autolysin precursor | Sca_0659 | SA0905 atlA | SACOL1062 | 6.8 | + | − | 133.1 | 9.2 |

| AtlCS7 | Major autolysin precursor | Sca_0659 | SA0905 atlA | SACOL1062 | 6 | + | − | 133.1 | 9.2 |

| AtlCS10 | Major autolysin precursor | Sca_0659 | SA0905 atlA | SACOL1062 | 2.2 | + | − | 133.1 | 9.2 |

| AtlCS11 | Major autolysin precursor | Sca_0659 | SA0905 atlA | SACOL1062 | 2.1 | + | − | 133.1 | 9.2 |

| SceA | SceA precursor | Sca_1598 | SA1898 sceD | SACOL2088 | 3.6 | + | − | 22.2 | 5.2 |

| SA2356 isaA | SACOL22584 | ||||||||

| SceA1 | SceA precursor | Sca_1598 | SA1898 sceD | SACOL2088 | 3.3 | + | − | 22.2 | 5.2 |

| SA2356 isaA | SACOL22584 | ||||||||

| SceA2 | SceA precursor | Sca_1598 | SA1898 sceD | SACOL2088 | 3.4 | + | − | 22.2 | 5.2 |

| SA2356 isaA | SACOL22584 | ||||||||

| Sca0404 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 6.8 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca04041 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 17.8 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca04042 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 12.3 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca04043 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 4.1 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca04044 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 6.9 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca04045 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 6.1 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca04046 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 4.1 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca04047 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 4.9 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca04048 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 6.5 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca04049 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 4.5 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca040410 | LysM family protein | Sca_0404 | − | − | 3.3 | + | − | 32.4 | 6.1 |

| Sca2221 | Hypothetical protein | Sca_2221 | − | − | 2.8 | + | − | 17.1 | 5.1 |

| Cell wall anchored proteins | |||||||||

| Sca2092 | Hypothetical protein | Sca_2092 | − | − | 2.7 | + | − | 48.1 | 7.9 |

| Sca2092 | Hypothetical protein | Sca_2092 | − | − | 13.66 | + | − | 48.1 | 7.9 |

| Membrane proteins | |||||||||

| Fhs | Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase homolog | Sca_1337 | SA1553 fhs | SACOL1782 | 3.6 | − | − | 59.9 | 5.4 |

| Fhs1 | Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase homolog | Sca_1337 | SA1553 fhs | SACOL1782 | 5 | − | − | 59.9 | 5.4 |

| GlpD | Aerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase homolog | Sca_0950 | SA1142 glpD | SACOL1321 | 4.2 | − | + | 62.7 | 5.8 |

| Lqo2 | Putative lactate:quinone oxidoreductase | Sca_2266 | SA2400 mqo2 | SACOL2623 | 3.0 | − | − | 55.5 | 5.4 |

| Lqo21 | Putative lactate:quinone oxidoreductase | Sca_2266 | SA2400 mqo2 | SACOL2623 | 4.0 | − | − | 55.5 | 5.4 |

| SdhB | Succinate dehydrogenase iron-sulfur protein subunit homolog | Sca_0767 | SA0996 sdhB | SACOL1160 | 6.3 | − | − | 30.8 | 6.5 |

| Cytosolic proteins | |||||||||

| FabG | 3-oxoacyl-(acyl-carrier protein) reductase | Sca_0854 | SA1074 fabG | SACOL1245 | 3.1 | − | − | 26.1 | 5.2 |

| FabI | Putative trans-2-enoyl-ACP reductase | Sca_0612 | SA0869 fabI | SACOL1016 | 7.0 | − | 28.0 | 5.5 | |

| GapA | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Sca_0424 | SA0727 gap | SACOL1016 | 3.8 | − | + | 36.3 | 4.7 |

| GrpE | Putative GrpE protein (HSP-70 cofactor) | Sca_1203 | Sa1410 grpE | SACOL1638 | 2.3 | − | + | 23.0 | 4.3 |

| GuaB | Putative inositol-monophosphate dehydrogenase | Sca_0049 | SA0375 guaB | SACOL0460 | 2.2 | − | − | 52.8 | 5.5 |

| KatA | Catalase | Sca_2336 | SA1170 katA | SACOL0866 | 2.1 | − | − | 57.2 | 5.3 |

| KatA1 | Catalase | Sca_2336 | SA1170 katA | SACOL0866 | 2.9 | − | − | 57.2 | 5.3 |

| PdhB | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component beta subunit homolog | Sca_0720 | SA0944 pdhB | SACOL1103 | 10 | − | − | 35.2 | 4.6 |

| RplC | 50S ribosomal protein L3 homolog | Sca_1735 | SA2047 rplC | SACOL_2239 | 2.2 | − | + | 23.7 | 9.6 |

| RplE | 50S ribosomal protein P5 homolog | Sca_1723 | SA2035 rplE | SACOL2227 | 5.1 | − | − | 20.2 | 9.0 |

| RplF | Probable 50S ribosomal protein L6 | Sca_1720 | SA2033 rplF | SACOL2224 | 3.5 | − | + | 19.6 | 9.5 |

| RplJ | 50S ribosomal protein L10 homolog | Sca_0195 | SA0497 rplJ | SACOL0585 | 2.4 | − | − | 17.8 | 5.1 |

| OdhA | Putatative 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component | Sca_1058 | SA1245 kgd | SACOL1449 | 2.7 | − | + | 105.6 | 5.3 |

| Tig | Trigger factor homolog | Sca_1281 | SA1499 tig | SACOL1722 | 2.2 | − | − | 49.5 | 4.3 |

| ThiD | Putative phosphomethylpyrimidine kinase | Sca_1595 | SA1896 thiD | SACOL2085 | 2.1 | − | − | 29.8 | 5.3 |

| Tkt | Putative transketolase | Sca_0983 | SA1177 tkt | SACOL1377 | 3 | − | − | 72.8 | 5.0 |

| TpiA | Triosephosphate isomerase homolog | Sca_0426 | SA0729 tpi | SACOL0840 | 4.7 | − | − | 27.5 | 4.8 |

| UreC | UreC urease alpha subunit homolog | Sca_1782 | SA2084 ureC | SACOL2282 | 3.9 | − | − | 62.4 | 5.3 |

| Sca0081 | Putative intracellular protease/amidase | Sca_0081 | − | − | 6.8 | − | − | 25.7 | 6.7 |

| Sca0559 | Putative peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | Sca_0559 | SA0815 | SACOL0957 | 2.1 | − | − | 21.8 | 4.4 |

| Sca0563 | NADH-dependent flavin oxidoreductase | Sca_0563 | SA0817 | SACOL0392 | 2.2 | − | − | 42.3 | 5.3 |

| Sca1991 | Pyruvate oxidase | Sca_1991 | SA2327 | SACOL0893 | 3.8 | − | − | 63.6 | 6.1 |

Subcellular localization was predicted using PSORTb.

Several identified spots of one protein were numbered.

Volume ratios in the range of 1 to ∞ indicate an increase of the volume of the respective protein spot and volume ratios in the range –1 to –∞ indicate a decrease of the volume of the respective protein spot. Only volume ratios ≥ 2 and ≤ −2 were defined as significant changes between the different strains.

Typical signal sequence was predicted using SignalP.

Non-classical secretion was predicted using SecretomeP.

Theoretical molecular weight (MW) and pI were calculated for mature proteins without signal sequence using MW/pI tools.

Superscripts refer to differently processed protein spots.

3.3 Few proteins show increased abundance in the wt secretome compared to the femB mutant

Only seven proteins were less abundant in the mutant secretome (Fig.5). Four of them belonged to signal peptide-dependent transported proteins: SceB, Sca0421, Sca2221, and Sca2250 (Table2). SceB showed 60% identity with Staphylococcal secretory antigen A (SsaA) of Staphylococcus epidermidis and S. aureus. SsaA is described in S. epidermidis as a highly antigenic protein [18]. The proteins Sca2250 and Sca0421 revealed no significant similarity to known proteins. Interestingly, the polyglycerol phosphate synthase LtaS (lipoteichoic acid synthase), a lipoteichoic acid biosynthesis enzyme, was also less abundant in the mutant. LtaS and its homologs in other Gram-positive bacteria were predicted to be polytopic membrane proteins with a large enzymatic domain located on the extracellular side of the bacterial membrane. According to this topological prediction, a cleaved fragment of the LtaS protein containing the complete enzymatic sulfatase domain was detected in the supernatant and cell wall-associated fractions in S. aureus [3,19]. Recently, the structure of the extracellular LtaS protein was determined and found to contain the complete enzymatic sulfatase [20]. Two typical cytosolic proteins, the acetate kinase homolog (AckA) and a hypothetical protein (Sca1315), were also found to be less abundant in the mutant secretome than in the wt (Table2).

3.4 Proteins showing increased abundance in the secretome of the femB mutant belong to three categories

3.4.1 Murein hydrolases

From the 30 proteins analyzed that are more abundant in the femB mutant (Table3), four proteins belonged to signal peptide-dependent transported proteins: AtlCS, the major autolysin; SceA, which resembled SceD and IsaA of S. aureus; Sca0404, a LysM family protein; and Sca2221, a hypothetical protein. All of these enzymes are involved in murein turnover and daughter cell separation, and their increased production in the femB mutant is most likely a compensatory response to partially resolve the cell-wall interlinked cell clusters. AtlCS, the major autolysin, organized similarly to its homologs in S. aureus (AtlA) and S. epidermidis (AtlE) [21–23], is produced as a bifunctional precursor protein and functions primarily to hydrolyze the murein in the septum of the daughter cells catalyzing cell separation. The occurrence of multiple protein spots (Fig.5 and Table3) is most likely due to their processing in defined substructures of the precursor protein [22]. SceA belongs to the early and highly expressed exoproteins in S. carnosus [24], and its similarity to SceD (32%) and immunodominant antigen IsaA (37%) of S. aureus and S. epidermidis suggests that it is a cell wall hydrolase. IsaA and SceD are two putative lytic transglycosylases of S. aureus with autolytic activity. The inactivation of sceD resulted in impaired cell separation, as indicated by cell clumping [25]. Sca0404 belongs to the LysM family of proteins and is similar in size to autolysins Aae and Aaa [26,27] that contain repetitive sequences in their N-terminal portion that represent the PGN-binding domain (LysM) and a C-terminally located cysteine- and histidine-dependent amidohydrolase/peptidase (CHAP) domain with bacteriolytic activity in many proteins [28]. Lastly, Sca2221 is a small (17 kDa) protein, which shows no conspicuous similarity.

3.4.2 Cytosolic proteins

The vast majority of increased protein spots in the femB mutant were typical cytosolic proteins (Table3). We identified 20 highly salient proteins, some of which represent typical enzymes of central metabolic pathways, such as FabG, FabI, GuaB, PdhB, OdhA, ThiD, Tkt, TpiA, UreC, Sca0081 (putative intracellular protease/amidase), Sca0563 (NADH-dependent flavin oxidoreductase), and Sca1991 (pyruvate oxidase). Others are involved in protein folding and oxidative stress situations—GrpE, Tig, Sca0559 (putative peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase), and KatA, while still others represent 50S ribosomal proteins such as RplC, RplE, RplF, and RplJ.

3.4.3 Membrane-associated enzymes

Four membrane-associated enzymes increased in the culture supernatant: formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase (Fhs), Lqo, GlpD, and SdhB (Table3). Fhs transfers formyl groups to 10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate (formyl-THF). In anaerobic conditions, PFL (pyruvate formate lyase) is important as a formate donor [29]. GlpD (aerobic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) is membrane-associated in S. aureus and strongly activated by detergents. In the femB mutant Lqo (earlier named Mqo2) was enhanced; it is required for the reassimilation of l-lactate during NO·-stress. Lqo is also critical to respiratory growth in l-lactate as a sole carbon source [30]. Finally, SdhB is part of the succinate dehydrogenase complex (Sdh) consisting of three subunits: a membrane-bound cytochrome b-558 (SdhC), a flavoprotein containing an FAD-binding site (SdhA), and an iron-sulfur protein with a binding region signature of the 4Fe-4S-type (SdhB) [31]. Sdh is part of the TCA cycle, which plays a central role in oxidative growth, and catalyzes the oxidation of succinate to fumarate by donating FADH2 for oxidative phosphorylation.

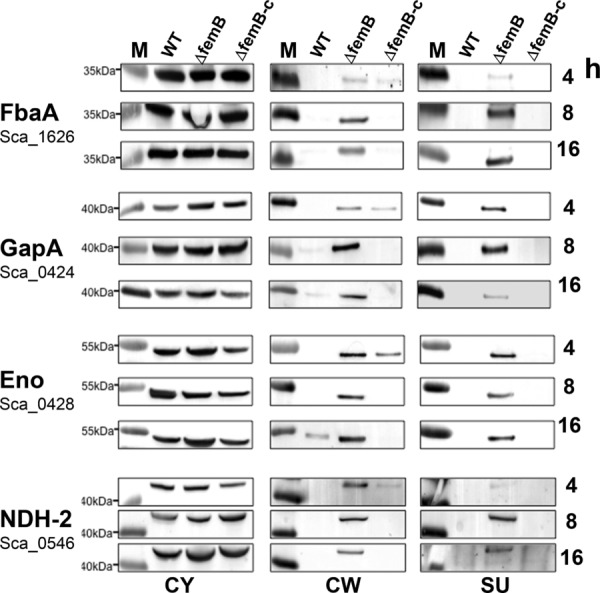

3.4.4 Localization analysis of four typical cytoplasmic proteins

To verify the data of secretome analysis, we purified four typical S. aureus- specific cytosolic proteins, raised rabbit antibodies, and determined the presence of the target proteins in the cytosolic fraction, the cell wall fraction, and the culture supernatant by Western blotting (Fig.6). The antibodies cross-reacted with the highly conserved S. carnosus counterparts. The cytosolic proteins investigated were glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GapA), enolase (Eno), fructose-1,6-bisphosphat-aldolase (FbaA), and NADH dehydrogenase (NDH-2). In the cytosolic fraction (CY), there was no marked difference in protein amounts between the wt, the femB mutant, and the complemented femB mutant. There was, however, a clear difference in the cell wall fraction (CW) and culture supernatant (SU) showing a significant increase in the femB mutant confirming that the cytosolic target proteins were abundantly exported.

Figure 6.

Localization of cytoplasmic marker proteins of S. carnosus wt, its femB mutant and the complementary mutant (femB-c) in the cytosole, cell wall, and supernatant by Western blot after 4, 8, and 16 h cultivation. The proteins fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (FabA), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GapA), enolase (Eno), and NADH-dehydrogenase (NDH-2) were each detected using specific antibodies. M: pre-stained molecular weight marker.

3.4.5 Transcription of genes encoding cell-wall lytic enzymes was up-regulated in the femB mutant, while that of cytosolic target genes was unchanged

Northern blot analysis of a selected set of genes encoding secreted and cytosolic proteins was performed to examine a possible correlation with the increased protein secretion. RNA was isolated from the wt, its femB mutant, and the complemented mutant in the exponential growth phase. The transcripts for the sceA, sceB, sceD, atlCS, and sca_0404 genes are clearly increased in the femB mutant, which correlates well with the increased amount of protein in the supernatant of the femB mutant (Supporting Information Table 3). Only SceB was an exception, as it was more abundant in the wt secretome. However, the transcription level of genes encoding the cytosolic proteins AhpC, GapA, KatA, Eno, and Tkt was essentially unchanged in the wt and the mutant, though these proteins were more abundant in the secretome of the mutant (Supporting Information Table 3).

4 Discussion

Here, we showed that the alteration of the cell wall structure in the femB mutant of S. carnosus had an enormous impact on morphology and physiology: expanded cells, retarded growth, high susceptibility to cell wall antibiotics, decrease of PGN crosslinking or unusually high secretion, and release of proteins into the culture supernatant. These pleiotropic effects suggest that the shortening of the interpeptide bridge from five to three glycine residues poses a life-threatening problem for the cells. The comparative analysis of secreted proteins in wt and femB mutant revealed that some proteins were less but the vast majority was more abundant in the mutant. The question is which of the differently expressed proteins in the secretome of the mutant is a response to adaptation or represents collateral damage.

It is very likely that the various Sec-dependent enzymes overexpressed in the femB mutant represent an adaptation response as the transcription of the corresponding genes is increased in the mutant. AtlCS, SceA, and Sca0404 represent murein hydrolyses. AtlCS belongs to the major staphylococcal autolysins Atl [21]. In staphylococci, Atl is crucial for daughter cell separation [32]. The other two secondary murein hydrolases, which were over-represented in the secretome of the femB mutant, were SceA and Sca0404. SceA is homologous to SceD and IsaA which represent two putative lytic transglycosylases in S. aureus [25] and Sca0404 belongs to the LysM family of proteins that represents a PGN-binding domain [33]. Because of the four- to nine-fold overexpression of the murein hydrolases AtlCS, SceA, and Sca0404 we assume that they represent a compensation reaction to accommodate the altered PGN structure in order to partially allow cell wall growth and daughter cell separation.

Proteins with a decreased prevalence in the secretome of the femB mutant were SceB, LtaS, AckA, and Sca1315. Particularly SceB and LtaS are interesting as their decreased production might also be part of the survival strategy of the femB mutant. SceB belongs to the prominently secreted exoproteins in S. carnosus; it is homologous to the S. epidermidis SsaA [18], which contains a cysteine- and histidine-dependent amidohydrolases and peptidases (CHAP) domain, which functions in some proteins as a l-muramoyl-l-alanine amidase or a d-alanyl-glycyl endopeptidase within the PGN [34,35]. Particularly, the d-alanyl-glycyl endopeptidase activity could be fatal in the femB mutant, as it would further decrease the degree of PGN cross-linking thus aggravating the already weakened murein network. Surprisingly, the membrane-associated LtaS was also decreased in the secretome of the femB mutant. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA), an important cell wall component of Gram-positive bacteria, is membrane-anchored via its lipid moiety. LtaS is required for LTA backbone synthesis and it has been shown recently that the enzyme accumulates at the cell division site [36]. Therefore, its presence in the secretome of the wt was not surprising, but its decreased presence in the secretome of the femB mutant was. In principle, we expected an increased LtaS expression in the femB mutant, as LTA synthesis is required for bacterial growth and cell division [37] and a decreased LtaS might worsen the growth defect of the femB mutant. Recently, it has been shown that LTA serves as a receptor for the Atl-repeats at the cross wall [38]. If the LTA content were decreased in the femB mutant, then back-binding of AtlCS to the cross wall would be affected; therefore the upregulation of AtlCS as a compensation reaction would make sense.

However, the vast majority of proteins overrepresented in the secretome of the femB mutant represent typical cytosolic proteins (Table3). With a few examples—FbaA, GapA, Eno, and Ndh-2—we showed in Western blots that these proteins are highly increased in the cell-wall fraction and the supernatant of the femB mutant (Fig.6). Interestingly, their quantity in the cytosolic fraction was essentially similar to that of the wt and the complemented mutant, which suggests that the level of gene expression should not differ much in the wt and mutant. Indeed, transcription analysis revealed no significant difference in the tested ahpC, gapA, katA, eno, and tkt genes (Supporting Information Table 3). Release of typical cytosolic proteins into the culture supernatant, also referred to as “non-classical protein excretion,” has been observed in many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria such as staphylococci, streptococci, Bacillus subtilis, Listeria monocytogenes, or E. coli. In particular, glycolytic enzymes, chaperones, translation factors, or enzymes involved in detoxification of ROS were found in the supernatants by secretome analysis [39–44].

As there is no indication for an increased gene expression for the corresponding proteins, we don't think that they contribute much to the survival strategy of the femB mutant. We assume that the increased release of these proteins can be ascribed to a collateral damage of the altered cell wall structure and the increased autolysis activity.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the expert technical help of Regine Stemmler. This work was funded by the German Research Foundation: SFB766 and TR-SFB34.

Glossary

- BM

basic medium

- CHAP

cysteine- and histidine-dependent amidohydrolase/peptidase

- CY

cytosolic fraction

- LTA

lipoteichoic acid

- LtaS

lipoteichoic acid synthase

- MW

molecular weight

- PGN

peptidoglycan

- PFL

pyruvate formate lyase

- wt

wild type

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site

5 References

- [1].Bendtsen JD, Kiemer L, Fausboll A, Brunak S. Non-classical protein secretion in bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pasztor L, Ziebandt AK, Nega M, Schlag M. Staphylococcal major autolysin (atl) is involved in excretion of cytoplasmic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:36794–36803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167312. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ziebandt AK, Weber H, Rudolph J, Schmid R. Extracellular proteins of Staphylococcus aureus and the role of SarA and sigma B. Proteomics. 2001;1:480–493. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200104)1:4<480::AID-PROT480>3.0.CO;2-O. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Berger-Bächi B. Genetic basis of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 1999;56:764–770. doi: 10.1007/s000180050023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rohrer S, Maki H, Berger-Bächi B. What makes resistance to methicillin heterogeneous? J. Med. Microbiol. 2003;52:605–607. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Maidhof H, Reinicke B, Blumel P, Berger-Bächi B. femA, which encodes a factor essential for expression of methicillin resistance, affects glycine content of peptidoglycan in methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:3507–3513. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3507-3513.1991. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Henze U, Sidow T, Wecke J, Labischinski H. Influence of femB on methicillin resistance and peptidoglycan metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:1612–1620. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1612-1620.1993. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rosenstein R, Nerz C, Biswas L, Resch A. Genome analysis of the meat starter culture bacterium Staphylococcus carnosus TM300. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:811–822. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01982-08. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schleifer KH, Fischer U. Description of a new species of the genus StaphylococcusStaphylococcus carnosus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1982;32:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Götz F. Staphylococcus carnosus: a new host organism for gene cloning and protein production. Soc. Appl. Bacteriol. Symp. Ser. 1990;19:49S–53S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 1983;166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Schleifer KH, Kloos WE, Moore A. Taxonomic status of Micrococcus luteus (Schroeter 1872) Cohn 1872: correlation between peptidoglycan type and genetic compatibility. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1972;22:224–227. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wieser M, Denner EB, Kampfer P, Schumann P. Emended descriptions of the genus MicrococcusMicrococcus luteus (Cohn 1872) and Micrococcus lylae (Kloos et al. 1974) Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002;52:629–637. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-2-629. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Eymann C, Dreisbach A, Albrecht D, Bernhardt J. A comprehensive proteome map of growing Bacillus subtilis cells. Proteomics. 2004;4:2849–2876. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400907. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bernhardt J, Büttner K, Scharf C, Hecker M. Dual channel imaging of two-dimensional electropherograms in Bacillus subtilis. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:2225–2240. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990801)20:11<2225::AID-ELPS2225>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brückner R. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1997;151:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Thumm G, Götz F. Studies on prolysostaphin processing and characterization of the lysostaphin immunity factor (Lif) of Staphylococcus simulans biovar staphylolyticus. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;23:1251–1265. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2911657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lang S, Livesley MA, Lambert PA, Littler WA. Identification of a novel antigen from Staphylococcus epidermidis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2000;29:213–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01525.x. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gatlin CL, Pieper R, Huang ST, Mongodin E. Proteomic profiling of cell envelope-associated proteins from Staphylococcus aureus. Proteomics. 2006;6:1530–1549. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500253. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lu D, Wormann ME, Zhang X, Schneewind O. Structure-based mechanism of lipoteichoic acid synthesis by Staphylococcus aureus LtaS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1584–1589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809020106. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Albrecht T, Raue S, Rosenstein R, Nieselt K. Phylogeny of the staphylococcal major autolysin and its use in genus and species typing. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:2630–2636. doi: 10.1128/JB.06609-11. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Heilmann C, Hussain M, Peters G, Götz F. Evidence for autolysin-mediated primary attachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis to a polystyrene surface. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;24:1013–1024. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4101774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Oshida T, Sugai M, Komatsuzawa H, Hong YM. A Staphylococcus aureus autolysin that has an N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase domain and an endo-beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase domain: cloning, sequence analysis, and characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:285–289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.285. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Montenbruck IP. 1992. Eberhard-Karls-Universität, Thesis 128 Tübingen.

- [25].Stapleton MR, Horsburgh MJ, Hayhurst EJ, Wright L. Characterization of IsaA and SceD, two putative lytic transglycosylases of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:7316–7325. doi: 10.1128/JB.00734-07. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Heilmann C, Thumm G, Chhatwal GS, Hartleib J. Identification and characterization of a novel autolysin (Aae) with adhesive properties from Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbiology. 2003;149:2769–2778. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26527-0. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Heilmann C, Hartleib J, Hussain MS, Peters G. The multifunctional Staphylococcus aureus autolysin Aaa mediates adherence to immobilized fibrinogen and fibronectin. Infect. Immunity. 2005;73:4793–4802. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4793-4802.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hirschhausen N, Schlesier T, Peters G, Heilmann C. Characterization of the modular design of the autolysin/adhesin Aaa from Staphylococcus aureus. Plos One. 2012;7:e40353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Leibig M, Liebeke M, Mader D, Lalk M. Pyruvate formate lyase acts as a formate supplier for metabolic processes during anaerobiosis in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 2011;193:952–962. doi: 10.1128/JB.01161-10. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fuller JR, Vitko NP, Perkowski EF, Scott E. Identification of a lactate-quinone oxidoreductase in Staphylococcus aureus that is essential for virulence. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2011;1:19. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2011.00019. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hederstedt L, Rutberg L. Succinate dehydrogenase–a comparative review. Microbiol. Rev. 1981;45:542–555. doi: 10.1128/mr.45.4.542-555.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Götz F, Heilmann C, Stehle T. Functional and structural analysis of the major amidase (Atl) in Staphylococcus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014;304:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Frankel MB, Schneewind O. Determinants of murein hydrolase targeting to cross-wall of Staphylococcus aureus peptidoglycan. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:10460–10471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bateman A, Rawlings ND. The CHAP domain: a large family of amidases including GSP amidase and peptidoglycan hydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:234–237. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rigden DJ, Jedrzejas MJ, Galperin MY. Amidase domains from bacterial and phage autolysins define a family of gamma-D,L-glutamate-specific amidohydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:230–234. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(03)00062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Reichmann NT, Picarra Cassona C, Monteiro JM, Bottomley AL. Differential localization of LTA synthesis proteins and their interaction with the cell division machinery in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2014;92:273–286. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12551. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gründling A, Schneewind O. Synthesis of glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8478–8483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701821104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zoll S, Schlag M, Shkumatov AV, Rautenberg M. Ligand-binding properties and conformational dynamics of autolysin repeat domains in staphylococcal cell wall recognition. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:3789–3802. doi: 10.1128/JB.00331-12. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sibbald MJ, Ziebandt AK, Engelmann S, Hecker M. Mapping the pathways to staphylococcal pathogenesis by comparative secretomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006;70:755–788. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00008-06. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tjalsma H, Antelmann H, Jongbloed JD, Braun PG. Proteomics of protein secretion by Bacillus subtilis: separating the “secrets” of the secretome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:207–233. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.207-233.2004. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ziebandt AK, Becher D, Ohlsen K, Hacker J. The influence of agr and sigmaB in growth phase dependent regulation of virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus. Proteomics. 2004;4:3034–3047. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400937. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Li M, Rosenshine I, Tung SL, Wang XH. Comparative proteomic analysis of extracellular proteins of enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains and their ihf and ler mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:5274–5282. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5274-5282.2004. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Trost M, Wehmhoner D, Karst U, Dieterich G. Comparative proteome analysis of secretory proteins from pathogenic and nonpathogenic Listeria species. Proteomics. 2005;5:1544–1557. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401024. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Xia XX, Han MJ, Lee SY, Yoo JS. Comparison of the extracellular proteomes of Escherichia coli B and K-12 strains during high cell density cultivation. Proteomics. 2008;8:2089–2103. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.