Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototypic autoimmune disease characterized by the production of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in association with protean clinic manifestations. ANA can bind to nuclear molecules, most prominently DNA and histones in nucleosomes, to form complexes to promote pathogenesis. Because of the intrinsic immunological activity of the nuclear components, these complexes can amplify responses by interacting with diverse pattern recognition receptors and internal sensing systems. Among molecules associated with nucleosomal components, HMGB1, a non-histone protein, can emanate from activated and dying cells; HMGB1’s immune activity is determined by post-translational modifications, redox state and binding to other immune mediators. Although ANAs form complexes that deposit in the kidney or induce type 1 interferon, ANAs may also block immune activity. Together, these studies highlight the importance of complexes in the pathogenesis of lupus and their role as antigens, immunogens and adjuvants.

Keywords: Systemic lupus erythematosus, antinuclear antibody, DNA, histones, HMGB1, nucleosome

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototypic autoimmune disease characterized by profound serological disturbances in association with protean systemic manifestations that range in severity from mild skin and joint disease to life-threatening conditions such as nephritis, stroke and seizures (1). Despite the marked heterogeneity of disease course, essentially all patients produce autoantibodies to components of the cell nucleus (antinuclear antibodies or ANA); of these autoantigens, nucleosomal molecules are the most characteristic and closely linked to pathogenesis. ANAs are markers of diagnostic and prognostic significance and, in some instances, mediators of inflammation and tissue injury (2–4). Given the close association of ANA production with SLE, research into pathogenesis has focused on the immune cell mechanisms breaching tolerance as well as the immunological properties of the target nuclear antigens (4). This review will discuss the central role of the DNA and histone components of the nucleosome in the pathogenesis of SLE. In addition, the review will consider the role of HMGB1, a non-histone protein, which can bind to both DNA and histones, in the generation of autoimmunity.

The Serology of SLE

As shown in serological studies, certain ANA specificities show selective or even exclusive expression in SLE. These antibodies can be divided into two main groups: 1) antibodies to the nucleosome and its DNA and histone components; and 2) antibodies to RNA binding proteins (RBPs). Of this group, two antibodies have been identified as serological criteria in the classification of patients with SLE: anti-DNA and anti-Sm. DNA is the molecule of heredity while Sm is comprised of a set of proteins bound to uridine-rich RNA molecules; this snRNP (small nuclear ribonucleoprotein) plays a key role in RNA splicing.

ANA expression in lupus shows a property known as linkage. Thus, antibodies to DNA and histones occur commonly together while the production of anti-Sm is closely associated with anti-RNP antibodies which are directed to another snRNP called the U1 snRNP. Despite the categorization of anti-DNA and anti-Sm as markers for classification, these antibodies have independent expression and divergent responses to treatment. These differences likely relate to the contribution of different B cell and plasma cell populations to autoantibody production and mechanisms of antigen drive (5–8). Unlike antibodies to DNA, however, antibodies to RBPs do not appear closely associated with disease activity; furthermore, they are not a usual feature of spontaneous lupus models in mice. The expression of these antibodies will therefore not be considered further.

In contrast to the situation with protein autoantigens, including nuclear proteins, induction of anti-DNA antibodies by immunization with DNA has been very difficult and an experimental model of lupus comparable to collagen-induced arthritis or experimental allergic encephalitis has yet to be established despite some limited successes (9,10). Nevertheless, antibodies to DNA show features consistent with antigen drive. Thus, these antibodies show high avidity for purified DNA antigen, binding sites on the phosphodiester backbone present on both single stranded (ss) and double stranded (ds) DNA. Furthermore, monoclonal antibodies derived from murine models show the hallmark of antigen selection in terms of somatic mutation as well as clonal expansion in which amino acid changes among clone members increase DNA binding (11).

The mechanisms leading to anti-DNA production represent one of the great unsolved mysteries in immunology. While the identification of these mechanisms awaits further research, significant progress has come recently with the recognition of two salient features on the immunological properties of DNA and other nuclear molecules. These features concern the role of complexes, albeit of different kinds. The first kind of complex involves the interaction of DNA and histones to form the nucleosome, the central building block of chromatin; in the nucleosome, DNA and histones can also attach to non-histone binding proteins. The second kind of complexes relates to the interaction of ANA with nucleosomes and associated binding molecules.

A model of lupus based on the role of complexes of nucleosomal components provides a useful framework to decipher events in this disease, highlighting the interaction of these molecules to generate structures that can act together to stimulate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs); these PRRs, which interact with PAMPs (pathogen-associated molecular patterns) and DAMPs (damage-associated molecular patterns), include toll-like receptors (TLRs), non-TLR nucleic acid sensors and the inflammasome. Both PAMPs and DAMPs can broadly activate the immune system via the production of cytokines that promote B and T cell responses; certain PAMPs such as LPS are also B cell mitogens. Because of their immune activity, PAMPs and DAMPs can act as adjuvants in the generation of autoreactivity; certain DAMPs also serve as immunogens with intrinsic autoadjuvant properties. Rather than considering the complexes’ components in isolation, this model focuses on complexes as a whole, recognizing that each component may influence the ultimate activity.

The nucleosome

The nucleosome consists of a length of DNA of approximately 147 bases that is wrapped around a core histone octamer. This octamer consists of two molecules each of histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. In chromatin, the individual nucleosomes are separated by linker DNA to produce an appearance of “beads on a string” (12, 13). In contrast to the tight binding of DNA to the core histones, the interaction of DNA with H1 is weak as this molecule circulates freely in the nucleus. The nucleosome is a remarkable structure since both DNA and histone are intensely charged: DNA is negatively charged because of the backbone phosphate groups while histones are positively charged because of their content of amino acids like lysine. The mutual interaction of DNA and histones shields the charges that would otherwise make packing the genetic material into the nucleus physically impossible.

While studies on processes such as replication and transcription have long made the nucleosome the central focus, immunologists have paid comparatively less attention to this structure, instead concentrating on the DNA itself; the histones have also received comparatively less attention. Several lines of evidence, however, suggest that DNA functions immunologically in the context of nucleosomes and that the presence of histone and non-histone protein components in these complexes powerfully shapes their properties. At the level of serology, the expression of antibodies to DNA and histones occurs together very commonly. Furthermore, while some antibodies can bind to DNA or histones alone, many ANAs are directed to histone-DNA complexes, with assays with antigens such as nucleosomes or chromatin providing data similar to that of anti-DNA determinations (14–16).

Other evidence pointing to the importance of the nucleosome in immunology relates to observations that DNA and histones show marked similarity in both intra- and extracellular expression, with DNA and histones translocating outside the cell in the same situations, mostly prominently, cell death. Thus, in clinical conditions marked by high levels of cellular demise (e.g., shock, sepsis, infarction), biochemical or immunochemical assays of DNA, histone or nucleosome levels show highly concordant results (17,18). Given the strength of DNA-histone binding, these molecules likely contact the immune system together as a structural entity.

The immune activity of the nucleosome and its components

While the nucleosome is likely the major source of extracellular DNA and histones, only a few studies have used nucleosome preparations as stimuli in cell systems (19–21). In general, these studies have demonstrated in vitro immunostimulatory activity although the relationship between these preparations and the nucleosomes found in vivo is uncertain. In general, such nucleosome preparations have undergone digestion with DNase to remove linker DNA, which could remove stimulatory components; nucleosome preparations for in vitro study have also been assembled from purified DNA and histone components. Rather than using nucleosomes, most investigations on the immune activity of nuclear molecules have involved isolated and purified DNA and histones.

While DNA was long considered to be immunologically inert, studies in the past two decades have clearly established that DNA can be immunologically very active depending on sequence, base modification, backbone structure and context (Table 1). Indeed, bacterial DNA can behave as a PAMP based on the presence of unmethylated CpG (cytosine-guanine) motifs. Such motifs occur much more commonly in bacterial than mammalian DNA because of differences in cytosine methylation and so-called CpG suppression in mammalian DNA (22). DNA with immune activity is frequently called CpG DNA in recognition of the role of these motifs.

Table 1.

Determinants of the Immune Activity of DNA

| Sequence |

| Base methylation |

| Backbone structure |

| Strandedness |

| Protein binding |

| Intracellular location |

Bacterial DNA can stimulate immune cells following uptake into cells by interaction with toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9). TLR9 is located in an endosomal compartment on the interior of the cells. Following transit of DNA to the endosomal compartment and its acidification, stimulation by CpG DNA leads to downstream activation of NF-κB via MyD88 (23). In contrast to bacterial DNA, mammalian DNA fails to elicit a response of cells in culture. Indeed, depending on sequence, mammalian DNA may actually inhibit responses to bacterial DNA, presumably competing for uptake or receptor binding (24–25). The paltry activity of mammalian DNA may contribute to its poor immunogenicity in experimental models. In this regard, many studies on the immune properties of CpG DNA have utilized oligonucleotides with a phosphorothioate backbone. This modification substitutes a sulfur atom for one of the non-bridging oxygen atoms, leading to nuclease resistance and enhanced responses.

While free mammalian DNA is inactive, complexation with an antibody or a protein carrier such as the LL-37 defensin and amyloid fibrils can boost immunological activity by promoting uptake into cells and subsequent interaction with internal non-TLR immune sensors (26–28). These receptors allow recognition of foreign or damaged DNA, monitoring the inside of the cell just as do TLRs on the cell membrane monitor its outside (29–31). In this case, the uptake of complexes allows access of DNA to receptors whose ordinary function is to respond to cytosolic DNA introduced by infecting viruses or microorganisms; DNA damaged by oxidation can trigger these same receptors. Complexes formed between DNA and transfection agents can behave similarly and provide access of DNA into internal receptors, triggering responses that can differ from those of free CpG DNA (32).

In the context of lupus pathogenesis, these findings highlight the importance of complexation to the immune activity of DNA and histones and raise caution about systems using only free molecules to characterize immune responsiveness. In this regard, it is always possible that DNA added to a culture can form complexes with proteins released from dying cells although, with stimulation of B cells, macrophages, or dendritic cells by mammalian DNA, that does not appear to be the case. Similarly, histones added to a culture can bind to either proteins or nucleic acids to form an immunostimulatory complex.

As noted, DNA is negatively charged while histones are positively charged. The charge difference appears to have important immunological consequences since histones can directly activate immune cells. This activation can occur via the inflammasome, a sensing system that may respond to cell stress and therefore can be activated by a wide range of large and small molecules that lack an obvious structural resemblance (33). Other studies indicate that histones can activate the immune system by interaction with TLR 2, 4 and 9 (34,35). Because of its charge, histones can interact with the cell membrane, potentially inducing pores and cell stress.

In considering the activities of histones, it is important to ask whether the presence of DNA modifies their extracellular activity by neutralization of charge, for example. During cell death and resulting inflammation, events occurring either inside (e.g., DNA digestion during apoptosis) or outside the cell (e.g., nucleolytic attack of DNA by blood nucleases) could degrade DNA and allow the concentration of free histones to rise to levels where their immunological activities become manifest. Experimentally, it is difficult to distinguish the different biochemical forms of histones (e.g., bound and unbound to DNA), although the involvement of TLR9 is some responses induced by histones suggests that DNA may contribute to responses that are putatively induced by histones (34).

The importance of HMGB1 to the activity of complexes

Fundamental to genetic regulation is the binding to DNA proteins to alter the structure of the nucleosome and allow processes such as replication or transcription to occur. Among these proteins, HMGB1 has attracted enormous interest as an immunological mediator and can be categorized as a danger molecule, DAMP or alarmin. Whatever the terminology, HMGB1, once translocated from the nucleus to outside the cell, can display activities to induce and potentiate autoimmunity in SLE (36,37).

HMGB1 is a non-histone nuclear protein that is 215 amino acids long, organized in two DNA binding regions (A and B boxes) and a C terminal acidic tail. HMGB1 can bind to DNA through its boxes, showing preferences for unusual structures such as bends and cruciforms. It can also bind to histones through its acidic tail, suggesting that it can simultaneously bind both DNA and histone in the nucleus. The affinity of HMGB1 for DNA is not high and, inside the cell, HMGB1, like histone H1, travels freely in the nucleus, contacting DNA in a “hit and run” fashion (38,39).

The immunological actions of HMGB1 are highly diverse, suggesting a role in the pathogenesis of a wide range of infectious, inflammatory, and malignant diseases (36,37,40). These activities are dynamic and mutable, depending in part upon post-translational modifications that include redox modifications affecting three cysteine residues at positions 23, 45 and 103. With all three cysteines as thiols, HMGB1 can bind the CXCL12 chemokine and stimulate chemotaxis via CXCR4. With a difulfide bond between positions 23 and 45 and a thiol at position 103, HMGB1 can bind to TLR4 and induce cytokine production. With further oxidation of the cysteines to sulfonates, HMGB1 loses its immune activity (41,42). Another key modification of HMGB1 involves acetylation of nuclear localization signals which occurs during stimulation of macrophages by TLR 4; acetylation allows translocation of HMGB1 to the cytosol for extracellular release in secretory lysosomes (43).

The extracellular translocation of HMGB1, along with that of DNA and histones, can occur during SLE, involving cells either in the tissue or blood and result from immune activation or cell death. In the study of lupus, apoptosis has represented a focal point of investigation based on a popular model for pathogenesis. Apoptosis is a form of regulated cell death in which enzymes called caspases lead to the systematic disassembly of cells and cleavage of both DNA and proteins. Apoptosis can occur in both physiological and pathological situations and can be triggered by a wide range of stimuli. In simplest form, this model posits that autoimmunity in lupus can arise in response to an excessive load to autoantigenic nuclear material; this load can develop because of excessive cell death or an impaired clearance of apoptotic cells (44–46).

The clearance of apoptotic cells is elaborate and highly regulated and involves both humoral and cellular elements (47). In animal models, a defect in clearance molecules can lead to a lupus-like disease while, in patients, genetic deficiency of the C1q protein, which can bind apoptotic cells to promote clearance, is highly associated with lupus. Given these findings, it has been proposed that impaired clearance of dead and dying cells can have dire consequences, with persistence of apoptotic cells, while are ordinarily immunological silent or immunosuppressive, transitioning to a state called secondary necrosis. Like cells dying by primary necrosis, secondarily necrotic cells have been considered to be immunostimulatory or dangerous in a popular terminology.

Apoptosis and necrosis are two of the death settings in which HMGB1 release occurs although the form of the molecule, its immunological activity and attachment to DNA, histones or their complexes may vary in a way that can impact of lupus pathogenesis. Thus, with apoptosis, HMGB1 may initially show increased binding to chromatin, reflecting post-translational modifications of either histones or HMGB1 (48,49). As a result, HMGB1 can lose its free intra-nuclear mobility and, at least in early stages of the process, show nuclear retention. Furthermore, with apoptosis, HMGB1 can undergo oxidation which degrades its immunological activity (50,51). In contrast, during necrosis, HMGB1 is immediately released from the cell in a reduced and active form, freely diffusing away because of its limited chromatin binding.

The observations on the behavior of HMGB1 during experimental apoptosis and necrosis are difficult to reconcile with a model of lupus based on the failed clearance of apoptotic cells and a “dangerous” transition to necrosis. Since oxidation to sulfonates is a terminal event, once HMGB1 has undergone this change, it should have permanently lost its immunological activity. These findings could suggest that the immunological activity of secondarily necrotic cells may involve molecules other than HMGB1. Alternatively, the oxidation during apoptosis in vivo may be incomplete, with rapid clearance allowing the release of the reduced form prior to terminal oxidation.

As now recognized, cell death is biochemically and morphologically heterogeneous, with apoptosis and necrosis representing only two stereotypical patterns out of many (52). NETosis and pyroptosis are two other cell death processes that can produce extracellular DNA, histones and HMGB1 to drive events in lupus. NETosis is a cellular response of neutrophils and other cells to certain forms of immune activation including bacterial infection (53). In NETosis, the nuclear membrane breaks down and chromatin mixes with granule contents to form a mesh-like structure which is extruded from the cell. This structure, called a NET for neutrophil extracellular trap, has antibacterial properties based on physical entrapment of bacteria and killing by antibacterial molecules such as histones and myeloperoxidase.

Another death process that can lead to HMGB1 release is pyroptosis (54). As the name implies, pyroptosis is an inflammatory form of cell death that can be induced by stimulation of the inflammasome. Like other death forms, pyroptosis leads to release of nuclear molecules, including HMGB1, with the pattern of post-translational modification determined by whether TLR stimulation occurs concomitantly. In vitro studies indicate that inflammasome stimulation alone leads to the release of a disulfide form of HMGB1 while, with both TLR and inflammasome stimulation, acetylation also occurs (55).

Each of these death forms (apoptosis, necrosis, NETosis and pyroptosis) can lead to release of nucleosomes and HMGB1, alone or together. As a result, an aberration in either their magnitude or their clearance could create the scenario which has been at the center of models on the role of apoptosis for lupus pathogenesis. Interestingly, while the clearance of apoptotic cells has been extensively analyzed, less is known about the clearance of cells dying by other death forms. One study suggested the clearance of pyroptotic cell is similar to that apoptotic cells, raising the possibility that this death form, rather than apoptosis, is the source of the nuclear antigen that drives autoreactivity in SLE (56). NETosis could also produce nuclear antigens that drive autoreactivity; the clearance of NETs involves DNase, complement and macrophages, each of which can be aberrant in SLE (57,58).

While the details of clearance mechanisms remain unknown, these studies suggest that cell death leads readily to the release or extrusion of nucleosomal molecules as complexes, with the death pathway influencing the stoichiometry of the complexes as well as the intrinsic immune properties of the component macromolecules. Thus, during apoptosis, HMGB1 may be more tightly bound to other nucleosomal components. On the other hand, the HMGB1 may be oxidized, diminishing its ability to stimulate responses. These considerations do not preclude the extracellular assembly of complexes with components that emerge from different cells. Thus, reduced HMGB1 from an activated cell may interact with a nucleosome from a necrotic cell to form a more active complex than one with oxidized HMGB1.

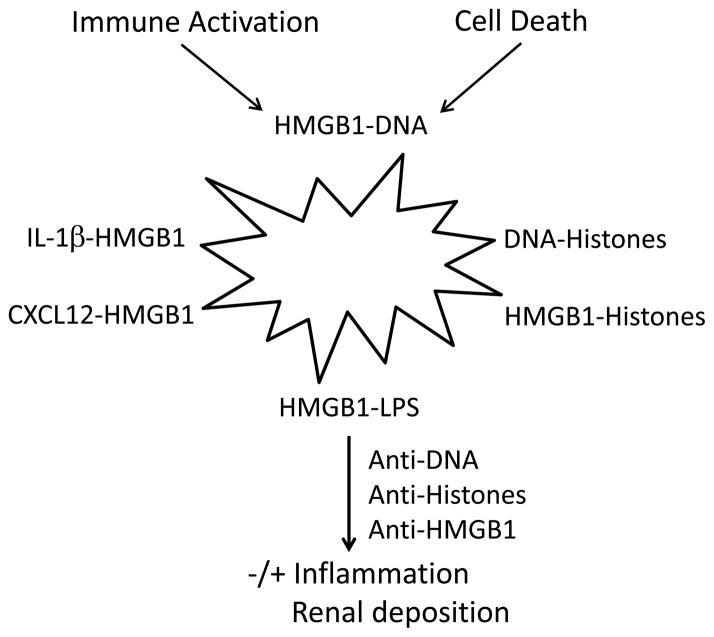

To the extent that each nuclear component retains its immune activity and capacity for receptor binding, the resulting complexes can stimulate a wide range of receptors, with HMGB1 behaving as an autoadjuvant in the induction of immune responses in SLE (59,60). These receptors include those for HMGB1 (RAGE, TLR 2 and TLR4), DNA (TLR9 and internal sensors), and histones (inflammasome, TLR 2, 4 and 9). Furthermore, HMGB1 can bind to cytokines such as IL-1β and PAMPs such as LPS to become even more potent (61–63). Thus, complexation can lead to a molecular structure (nanostructure) that can serve as antigen, immunogen and adjuvant. This complexation can also help explain why one molecule (e.g., histones) can show apparent interaction with multiple receptors in in vivo or in vitro experiments. Figure 1 illustrates the potential array of complexes that can form in the setting of autoimmunity or inflammation, including infection.

Figure 1.

The role of complexes in inflammation and autoimmunity in SLE. The figure illustrates some of the potential complexes that extracellular nuclear molecules, released during cell activation or cell deathn can form with each other as well as other immune active molecules (i.e., cytokines, chemokines or a PAMP like LPS). The cell depicted as a starburst represents a dying or activated cell, recognizing that some cells stimulated by TLR ligands undergo cell death. While all of these complexes can be formed in vitro, the existence and role in vivo for certain of these complexes in SLE, while plausible, have not yet been demonstrated. Furthermore, complexes driving events in SLE may have more components than indicated in the figure which focuses on pairs; thus, a complex of HMGB1 and LPS could also bind DNA and/or histones. These complexes in turn can interact with receptors for any of the component molecules. The figure also indicates that antinuclear antibodies can interact with complexes to stimulate or inhibit inflammation as well as deposit in the tissue.

The role of antinuclear antibodies

A critical component of any immunoactive complex in SLE is an autoantibody whose production depends upon dysregulated B cell expression; while nucleosomal antigens forming the complex likely derive from another cells, a dying B cell or plasma cell could theoretically produce both antibody and antigen components of the complex. Classically, lupus has been conceptualized as a disease in which immune complexes deposit in the kidney to fix complement and incite inflammation (64). While antibodies to double stranded DNA have been viewed as the key autoantibody to form immune complexes, theoretically, an antibody to any nucleosomal component (i.e., histones, DNA-histone complex) in the structure could serve a similar function and direct complexes to a renal site.

In addition to promoting renal disease, ANAs can promote immune activation by nucleosomal (as well as RBPs) antigens, facilitating uptake into immune cells, especially plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and access to internal nucleic acid sensors. The stimulation can lead to the production of type 1 interferon which has been implicated as a critical cytokine in pathogenesis, perturbing both the immune system and vasculature (65).

While the traditional role postulated for an ANA is to form a complex that incites nephritis or drives cytokine production, certain of these autoantibodies may have an unexpected role in pathogenesis: formation of complexes that inhibit immune responses of the component autoantigens (66–68). Thus, studies in animal models indicate that antibodies to HMGB1 or histones can block events in sepsis and shock; the effects of anti-HMGB1 antibodies and other types of HMGB1 inhibitors have also been demonstrated in animal models of inflammatory arthritis. This inhibitory action could result from either increased clearance of nuclear molecules or prevention of their receptor interaction. A role in transplantation immunity is also possible.

Studies on lupus in patients and animal models have long documented discordancy between serology and renal disease activity. Thus, patients with lupus may have high levels of anti-DNA antibodies but lack nephritis; animal models may show the same phenomenon. These findings have suggested that only certain anti-DNA antibodies can form complexes that are pathogenic or nephritogenic and can cause kidney disease (69). Similarly, in model studies in which normal animals are administered monoclonal anti-DNA autoantibodies, only certain antibodies show renal localization; the immunochemical properties determining pathogenicity remain unknown, however. A similar distinction may apply to antibodies that can promote cytokine induction by plasmacytoid dendritic cells.

In view of the effects of anti-histone and anti-HMGB1 antibodies in disease models, we would like to propose that, in lupus, certain ANAs can form non-pathogenic complexes that sequester or clear away nucleosomal molecules and thereby prevent stimulation of immune responses or deposition in the kidney. At present, there is no direct proof for this possibility but its inclusion in models on the role of ANAs in disease may provide clues to the discordancy between serology and clinical disease activity as well as the extraordinary heterogeneity among patients. Furthermore, the expression of non-pathogenic or protective ANAs could account for very large number of otherwise healthy subjects who do not develop autoimmunity despite robust ANA levels (70).

Conclusion

For many years, studies on both normal and aberrant immunity have followed a reductionist approach and used system to elucidate the immunological properties of single molecules. In more ways than one, biology is complex and virtually every important response involves the assembly of a complex of some kind to generate a novel activity. Among macromolecules, nuclear molecules have evolved to form complexes to coordinate the flow of genetic information. As this discussion indicates, the features relevant to genetics and genomics inside the cell may also pertain outside the cell, with the ANAs in lupus further modulating the immune activities of nucleosomal molecules and their HMGB1 partner, acting alone or together. Future studies will hopefully define the assembly and activity of complexes and provide the basis for new approaches to diagnosis and treatment.

Table 2.

Determinants of the Immune Activity of HMGB1

| Redox status |

| Acetylation |

| Cytokine binding |

| Chemokine binding |

| Binding of PAMPs and DAMPs |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a VA Merit Review Grant, a grant from Alliance for Lupus Research (ALR), and NIH 5U19-AI056363.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: The author declares that he has no competing interests as defined by Autoimmunity, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Tsokos GC. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2110–2121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1100359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan EM. Antinuclear antibodies: diagnostic markers for autoimmune diseases and probes for cell biology. Adv Immunol. 1989;44:93–151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harden JA. The lupus autoantigens and the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:457–460. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ardoin SP, Pisetsky DS. Developments in the scientific understanding of lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:218. doi: 10.1186/ar2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarty GA, Rice JR, Bembe ML, Pisetsky DS. Independent expression of autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1982;9:691–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pisetsky DS, Grammer AC, Ning TC, Lipsky PE. Are autoantibodies the targets of B-cell-directed therapy? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:551–556. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harley JB, James JA. Autoepitopes in lupus. J Lab Clin Med. 1995;126:506–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClain MT, Heinlen LD, Dennis GJ, Roebuck J, Harley JB, James JA. Early events in lupus humoral autoimmunity suggest initiation through molecular mimicry. Nat Med. 2005;11:85–89. doi: 10.1038/nm1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai DD, Krishnan MR, Swindle JT, Marion TN. Antigen-specific induction of antibodies against native mammalian DNA in nonautoimmune mice. J Immunol. 1993;151:1614–1626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilkeson GS, Pippen AM, Pisetsky DS. Induction of cross-reactive anti-dsDNA antibodies in preautoimmune NZB/NZW mice by immunization with bacterial DNA. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1398–1402. doi: 10.1172/JCI117793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radic MZ, Weigert M. Genetic and structural evidence for antigen selection of anti-DNA antibodies. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:487–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luger K, Dechassa ML, Tremethick DJ. New insights into nucleosome and chromatin structure: an ordered state or a disordered affair? Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:436–447. doi: 10.1038/nrm3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zentner GE, Henikoff S. Regulation of nucleosome dynamics by histone modifications. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:259–266. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller S, Dieker J, Tincani A, Meroni PL. Pathogenic anti-nucleosome antibodies. Lupus. 2008;17:431–436. doi: 10.1177/0961203308090030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mortensen ES, Rekvig OP. Nephritogenic potential of anti-DNA antibodies against necrotic nucleosomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:696–704. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bizzaro N, Villalta D, Giavarina D, Tozzoli R. Are anti-nucleosome antibodies a better diagnostic marker than anti-dsDNA antibodies for systemic lupus erythematosus? A systemic review and a study of metanalysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holdenrieder S, Stieber P. Clinical use of circulating nucleosomes. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2009;46:1–24. doi: 10.1080/10408360802485875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisetsky DS. The translocation of nuclear molecules during inflammation and cell death. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013 Mar 20; doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5143. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell DA, Morrison B, VandenBygaart P. Immunogenic DNA-related factors. Nucleosomes spontaneously released from normal murine lymphoid cells stimulate proliferation and immunoglobulin synthesis of normal mouse lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1487–1496. doi: 10.1172/JCI114595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohan C, Adams S, Stanik V, Datta SK. Nucleosome: a major immunogen for pathogenic autoantibody-inducing T cells of lupus. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1367–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindau D, Rönnefarth V, Erbacher A, Rammensee H-G, Decker P. Nucleosome-induced neutrophil activation occurs independently of TLR9 and endosomal acidification: implications for systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:669–681. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krieg AM. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA and their immune effects. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:709–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barton GM, Kagan JC. A cell biological view of Toll-like receptor function: regulation through compartmentalization. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:535–542. doi: 10.1038/nri2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pisetsky DS, Reich CF. Inhibition of murine macrophage IL-12 production by natural and synthetic DNA. Clin Immunol. 2000;96:198–204. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gursel I, Gursel M, Yamada H, Ishii KJ, Takeshita F, Klinman DM. Repetitive elements in mammalian telomeres suppress bacterial DNA-induced immune activation. J Immunol. 2003;171:1393–1400. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chamilos G, Gregorio J, Meller S, Lande R, Kontoyiannis DP, Modlin RL, Gilliet M. Cytosolic sensing of extracellular self-DNA transported into monocytes by the antimicrobial peptide LL37. Blood. 2012;120:3699–3707. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-401364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahlenberg JM, Kaplan MJ. Little peptide, big effects: the role of LL-37 in inflammation and autoimmune disease. J Immunol. 2013;191:4895–4901. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Domizio J, Dorta-Estremera S, Gagea M, Ganuly D, Meller S, Li P, Zhao B, Tan FK, Bi L, Gilliet M, Cao W. Nucleic acid-containing amyloid fibrils potently induce type I interfgeron and stimulate systemic autoimmunity. PNAS. 2012;109:14550–14555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206923109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagata S, Kawane K. Autoinflammation by endogenous DNA. Adv Immunol. 2011;110:139–161. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387663-8.00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atianand MK, Fitzgerald KA. Molecular basis of DNA recognition in the immune system. J Immunol. 2013;190:1911–1918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gehrke N, Mertens C, Zillinger T, Wenzel J, Bald T, Zahn S, Tuting T, Hartmann G, Barchet W. Oxidative damage of DNA confers resistance to cytosolic nuclease TREX1 degradation and potentiates STING-dependent immune sensing. Immunity. 2013;39:482–495. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang W, Pisetsky DS. The induction of HMGB1 release from RAW 264.7 cells by transfected DNA. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:2038–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang H, Chen H-W, Evankovich J, Yan W, Rosborough BR, Nace GW, Ding Q, Loughran P, Beer-Stolz D, Billiar TR, Esmon CT, Tsung A. Histones activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in Kupffer cells during sterile inflammatory liver injury. J Immunol. 2013;191:2665–2679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang H, Evankovich J, Yan W, Nace G, Zhang L, Ross M, Liao X, Billiar T, Xu J, Esmon CT, Tsung A. Endogenous histones function as alarmins in sterile inflammatory liver injury through toll-like receptor 9 in mice. Hepatology. 2011;54:999–1008. doi: 10.1002/hep.24501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allam R, Scherbaum CR, Darispudi MN, Mulay SR, Hägele H, Lichnekert J, Hagemann JH, Rupangudi KV, Ryu M, Schwarzenberger C, Hohenstein B, Hugo C, Uhl B, Reichel CA, Kromback F, Monestier M, Liapis H, Moreth K, Schaefer L, Anders H-J. Histones from dying renal cells aggravate kidney injury via TLR2 and TLR4. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1375–1388. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011111077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang H, Antoine DJ, Andersson U, Tracey KJ. The many faces of HMGB1: molecular structure-functional activity in inflammation, apoptosis, and chemotaxis. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93:1–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1212662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venereau E, Schiraldi M, Uguccioni M, Bianchi ME. HMGB1 and leukocyte migration during trauma and sterile inflammation. Mol Immunol. 2013;55:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Štros M. HMGB proteins: interactions with DNA and chromatin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas JO, Stott K. H1 and HMGB1: modulators of chromatin structure. Biochim Soc Trans. 2012;40:341–346. doi: 10.1042/BST20120014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang H, Lundbäck P, Ottosson L, Erlandsson-Harris H, Venereau E, Bianchi ME, Al-Abed Y, Andersson U, Tracey KJ, Antoine DJ. Redox modification of cysteine residues regulates the cytokine activity of high mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) Mol Med. 2012;18:250–259. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Venereau E, Casalgrandi M, Schiraldi M, Antoine DJ, Cattaneo A, DeMarchis F, Liu J, Antonelli A, Preti A, Raeli L, Shams SS, Yang H, Varani L, Andersson U, Tracey KJ, Bachi A, Uguccioni M, Bianchi ME. Mutually exclusive redox forms of HMGB1 promote cell recruitment or proinflammatory cytokine release. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1519–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonaldi, Talamo TF, Scaffidi P, Ferrera D, Porto A, Bachi A, Rubartelli A, Agresti A, Bianchi ME. Monocytic cells hyperacetylate chromatin protein HMGB1 to redirect it towards secretion. EMBO J. 2003;22:5551–5560. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muñoz LE, Lauber K, Schiller M, Manfredi AA, Herrmann M. The role of defective clearance of apoptotic cells in systemic autoimmunity. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:280–289. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagata S, Hanayama R, Kawane K. Autoimmunity and the clearance of dead cells. Cell. 2010;140:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao WH, Cohen PL. Disturbances of apoptotic cell clearance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:202. doi: 10.1186/ar3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poon IKH, Hulett MD, Parish CR. Molecular mechanisms of late apoptotic/necrotic cell clearance. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:381–397. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;18:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rovere-Querini P, Capobianco A, Scaffidi P, Valentinis B, Catalnotti F, Giazzon M, Dumitriu IE, Müller S, Iannacone M, Traversari C, Bianchi ME, Manfredi AA. HMGB1 is an endogenous immune adjuvant released by necrotic cells. EMBO J. 2004;5:1–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kazama H, Ricci J-E, Herndon JM, Hoppe G, Green DR, Ferguson TA. Induction of immunological tolerance by apoptotic cells requires caspase-dependent oxidation of high-mobility group box-1 protein. Immunity. 2008;29:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Urbonaviciute V, Meister S, Fürnrohr BG, Frey B, Gückel E, Schett G, Herrmann M, Voll RE. Oxidation of the alarmin high-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) during apoptosis. Autoimmunity. 2009;42:305–307. doi: 10.1080/08916930902831803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Abrams JM, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, Blagosklonny MV, Dawson TM, Dawson VL, El-Deiry WS, Fulda S, Gottlieb E, Green DR, Hengartner MO, Kepp O, Knight RA, Kumar S, Lipton SA, Lu X, Madeo F, Malorni W, Mehlen P, Nuñez G, Peter ME, Placentini M, Rubinszstein DC, Shi Y, Simon H-U, Vandenabeele P, White E, Yuan J, Zhivotovsky B, Melino G, Kroemer G. Molecular definitions of cell death subroutines: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2012. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:107–120. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps: is immunity the second function of chromatin? J Cell Biol. 2012;198:773–783. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miao EA, Rajan JV, Aderem A. Caspase-1-induced pyroptotic cell death. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:206–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nyström S, Antoine DJ, Lundbäck P, Lock JG, Nita AF, Högstrand K, Grandien A, Erlandsson-Harris H, Andersson U, Applequist SE. TLR activation regulates damage-associated molecular pattern isoforms released during pyroptosis. EMBO J. 2013;32:86–99. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Q, Imamura R, Motani K, Kushiyama H, Nagata S, Suda T. Pyroptotic cells externalize eat-me and release find-me signals and are efficiently engulfed by macrophages. Int Immunol. 2013;25:363–372. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxs161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leffler J, Martin M, Gullstrand B, Tyden H, Lood C, Truedsson L, Bengtsoon AA, Blom AM. Neutrophil extracellular traps that are not degraded in systemic lupus erythematosus activate complement exacerbating the disease. J Immunol. 2012;188:3522–3531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farrara C, Fadeel B. Macrophage clearance of neutrophil extracellular traps is a silent process. J Immunol. 2013;191:2647–2656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Urbonaviciute V, Fürnrohr BG, Meister S, Munoz L, Heyder P, DeMarchis F, Bianchi ME, Kirschning C, Wagner H, Amanfredi A, Kalden JR, Scheett G, Rovere-Querini P, Hermann M, Voll RE. Induction of inflammatory and immune responses by HMGB1-nucleosome complexes: implications for the pathogenesis of SLE. J Exp Med. 205:3007–3018. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao S-Y, Chen B, Senthil K, Wu H, Parroche P, Drabic S, Golenbock D, Sirois C, Hua J, An LL, Audoly L, LaRosa G, Bierhaus A, Naworth P, Marshak-Rothstein A, Crow MK, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Kiener PA, Coyle AJ. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nature Immunol. 2007;8:487–496. doi: 10.1038/ni1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bianchi ME. HMGB1 loves company. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:573–576. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1008585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wähämaa H, Schierbeck H, Hreggvidsdottir HS, Palmblad K, Aveberger AC, Andersson U, Harris HE. High mobility group box protein 1 in complex with lipopolysaccharide or IL-1 promotes an increased inflammatory phenotype in synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R136. doi: 10.1186/ar3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pisetsky D. Cell death in the pathogenesis of immune-mediated diseases: the role of HMGB1 and DAMP-PAMP complexes. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13256. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Koffler D, Agnello V, Thoburn R, Kunkel HG. Systemic lupus erythematosus: prototype of immune complex nephritis in man. J Exp Med. 1971;134:169–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shrivastav M, Niewold TB. Nucleic acid sensors and type I interferon production in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2013;4:319. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu J, Zhang X, Pelayo R, Monestier M, Ammollo CT, Semararo F, Taylor FB, Esmon NL, Lupu F, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med. 2009;15:1318–1321. doi: 10.1038/nm.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pisetsky DS. Antinuclear antibodies in rheumatic disease: a proposal for a function-based classification. Scand J Immunol. 2012;76:223–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakano T, Chen C-L, Goto S. Nuclear antigens and auto/alloantibody responses: friend or foe in transplant immunology. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:267156. doi: 10.1155/2013/267156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Krishnan MR, Wang C, Marion TN. Anti-DNA autoantibodies initiate experimental lupus nephritis by binding directly to the glomerular basement membrane in mice. Kidney Int. 2012;82:184–192. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pisetsky DS. Antinuclear antibodies in healthy people: the tip of autoimmunity’s iceberg? Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:109. doi: 10.1186/ar3282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]