Abstract

Objective

It is unknown into what extent patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) utilise a joint service number (Swedish Healthcare Direct, SHD) as first medical contact (FMC) instead of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and how this impact time to diagnosis. We aimed to (1) describe patients’ FMC; (2) find explanatory factors influencing their FMC (ie, EMS and SHD) and (3) explore the time interval from symptom onset to diagnosis.

Setting

Multicentred study, Sweden.

Methods

Cross-sectional, enrolling patients with consecutive STEMI admitted within 24 h from admission.

Results

We included 109 women and 336 men (mean age 66±11 years). Although 83% arrived by ambulance to the hospital, just half of the patients (51%) called EMS as their FMC. Other utilised SHD (21%), contacted their primary healthcare centre (14%), or went directly to the emergency room (14%). Reasons for not contacting EMS were predominantly; (1) my transport mode was faster (40%), (2) did not consider myself sick enough (30%), and (3) it was easier to be driven or taking a taxi (25%). Predictors associated with contacting SHD as FMC were female gender (OR 1.92), higher education (OR 2.40), history of diabetes (OR 2.10), pain in throat/neck (OR 2.24) and pain intensity (OR 0.85). Predictors associated with contacting EMS as FMC were history of MI (OR 2.18), atrial fibrillation (OR 3.81), abdominal pain (OR 0.35) and believing the symptoms originating from the heart (OR 1.60). Symptom onset to diagnosis time was significantly longer when turning to the SHD instead of the EMS as FMC (1:59 vs 1:21 h, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Using other forms of contacts than EMS, significantly prolong delay times, and could adversely affect patient prognosis. Nevertheless, having the opportunity to call the SHD might also, in some instances, lower the threshold for taking contact with the healthcare system, and thus lowers the number that would otherwise have delayed even longer.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This multicentre study represents the first investigation to explore first medical contact of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and its impact on delay times.

Completion of the self-reported survey within 24 hours after admittance minimised the risk of recall bias.

With the study's observational design, we can only report association rather than infer causation.

The survey is only validated in the Swedish language, which can make comparisons with previous studies difficult.

Further research is required to examine the underlying factors that contribute to the variation in utilisation of first medical contacts.

Introduction

It is well established that prompt diagnosis and treatment can reduce mortality, improve prognosis and reduce the duration of hospital stay in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).1 Reperfusion therapy should be started as soon as possible, at the latest 90 min from first medical contact (FMC).2 However, the total ischaemic time, that is, between symptom onset and reperfusion therapy, is the most important factor to achieve the best possible outcome for the patient.2 3 Whatever choice of reperfusion therapy, patient decision time is crucial, but delay in seeking treatment for STEMI symptoms is still a problem, with prehospital delay times being constantly high over a 20-year observation period.4

Studying and understanding pathways to diagnosis and treatment in patients with STEMI is vital for the development of successful interventions to encourage early actions by the patients.5 In Sweden, the general public has the opportunity to receive healthcare advice via telephone, Internet or a self-care guide booklet, from a national service number (1177) provided by the county councils and regions.6 However, it is unknown into what extent individuals utilise healthcare advice via telephone as an FMC instead of immediately contacting Emergency Medical Services (EMS) when falling ill in STEMI, and how such a decision will impact the time to diagnosis. We hypothesised that patients with STEMI turn to the EMS as the FMC in the acute phase, and that this action will shorten the time to diagnosis. Therefore, the aim of this multicentre study was to (1) describe patients’ FMC in the prehospital phase of an evolving STEMI; (2) find explanatory factors influencing their FMC (ie, EMS and Swedish Healthcare Direct, SHD) and (3) explore the time interval from symptoms to FMC and from FMC to diagnosis.

Method

Setting

In Sweden, with a population of 9.7 million people, there are 69 hospitals that care for patients with acute coronary artery disease (CAD), of which 28 have catheterisation laboratory facilities. All patients with suspected acute CAD are registered in the Swedish quality register SWEDEHEART.7 The annual number of hospitalised Swedish patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) is about 19 000 patients, whereas approximately 4500 represent an STEMI. In 2013, primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was the reperfusion therapy chosen in 93% of patients with STEMI getting reperfusion therapy. Thrombolysis is still used in areas with long transport distances such as the northern part of Sweden. All ambulances are staffed with nurses and have ECG facilities. When a patient with a suspected acute MI has contacted the EMS, having an ECG recorded is one of the first priorities. In order to interpret the ECG, have a diagnosis, and start prehospital treatment, a communication with the hospital is established.

The SHD service number was initiated 2003 and nationally completed 2013. It is staffed by advisement nurses 24/7, to answer questions, determine the need for further care, and provide advice and/or contact with other healthcare agencies/ambulance services in a non-life-threatening situation. The service is built on a common quality-assured medical database. In this manner, the general public is assured consistent, uniform advice. Around 500 000 Swedes call SHD every month.6

Study design

This Swedish multicentre study (SymTime) had a descriptive and comparative cross-sectional design of self-reported data. We enrolled participants from five hospitals in Sweden, all with catheterisation laboratory facilities and primary PCI enabled 24/7: two university hospitals (Umeå and Linköping) and three county hospitals (Luleå, Jönköping and Kalmar). The hospitals were selected by a diverged geographic location and type of hospital. Data were collected in the cardiac care unit (CCU) in each participating hospital during November 2012 to January 2014.

Ethical aspects

Permission for the study was obtained from the regional Ethical Review Board, Linköping, Sweden (D-nr 2012/201–31), and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.8 Informed consent was obtained from all patients. They were informed by the staff nurse both in writing and verbally. Patients should be pain free and haemodynamically stable when they were asked to participate.

Participants and procedure

Eligible patients were designed to be consecutively included within 24 h after admittance. The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) diagnosed with STEMI, defined as ST-elevation on admission ECG and a diagnosis of acute MI at discharge according to ESC’s guidelines;1 (2) ability to fill in the questionnaire and (3) willing to participate. Patients having difficulties in reading and speaking Swedish were excluded from the study.

Data collection

Clinical variables

The staff nurse incharge obtained clinical data such as information on diagnosis, important time point measurements (eg, ECG and FMC) and comorbidities from the medical records.

Symptoms and prehospital actions

A previously validated self-administered questionnaire9 covering 35 items; including (1) baseline characteristics, (2) symptoms, (3) course of events including multiple time point measurements and (4) description of transport mode was used to access self-reported data from the patients with STEMI included in the study. This questionnaire was originally developed and tested in a Swedish chest pain population. Since the questionnaire was developed a decade ago, a new literature research and expert validation was made in collaboration with the original developer. Additionally, a pilot study (n=5) was carried out to test user-friendliness and content in the modified questionnaire. The pilot patients completed the questionnaire within 24 h after admittance and were also interviewed about how they perceived all the questions. The pilot study confirmed that user-friendliness and content were at a satisfactory level, with only clarifying when it was single versus multiple choices for each item. No changes to the questions were needed.

Statistical analysis

Patient delay time was defined as the interval between ‘time-of-onset-of-symptoms’ until ‘FMC’. ‘FMC’ was defined as the time point when contacting the primary healthcare centre, SHD, EMS or emergency room (ER). System delay was defined as the interval between ‘FMC’ until ‘time to diagnosis’ (ie, ECG recording). We used frequencies and proportions to describe the history of patients’ characteristics, the sociodemographic, clinical and contextual variables, and their FMC. Continuous variables were reported as mean±SD or median (25th–75th centile) as appropriate. The sample was dichotomised into post-specified cut-offs for age based on the median in the sample (ie, <66 or ≥66 years old) to compare FMC by age. Likewise, we dichotomised the patient decision time using cut-offs of ≤1 h or >1 h to define a delayed patient decision time. This strategy was based on the data supporting maximum efficacy of reperfusion therapy given within 2 h of the onset of symptoms.3 10 In order to confirm that dichotomisation did not result in markedly different findings, we also ran these analyses using the continuous level data with similar results.

In the bivariate analyses, we used the χ2 test and the two-tailed Student t test (or Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables), to compare different characteristics with the participants’ FMC (ie, SHD or EMS) and to determine if there were any statistically significant differences between onset of symptoms and timespan to choice of FMC, and choice of FMC and timespan to diagnosis (ie, EMS compared with other FMC). Time measurements were available for 96% of the study population, therefore no sensitivity analyses were considered necessary.

Two separate hierarchical logistic regression models were used to determine sociodemographic (ie, age, gender, co-habiting status, educational level), comorbidities, clinical (ie, symptomatology, symptom burden, interpretation of symptoms, pain intensity) and contextual factors (ie, time of symptom onset, alone or not when falling ill) that was associated with choice of FMC (ie, SHD or EMS). Independent variables in the regression models were chosen based on results from bivariate analyses (p value <0.10 and after testing for multicollinearity), and clinical and theoretical relevance. All tests were two tailed and a p value <0.05 indicated statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, V.22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA) for Windows.

Results

Demographics and clinical variables

A total of 109 women and 336 men were included, mean age 66±11 years. A minority had previously experienced an MI (13%), nearly half of the participants suffered from hypertension (47%), 15% had diabetes, 5% atrial fibrillation, and 3% chronic heart failure. The majority experienced chest pain when falling ill (88%), while 98% experienced a combination of cardinal STEMI symptoms, that is, chest pain and/or radiating pain in the arms and/or cold sweat. The total symptom burden was 5.3±2.5 of the 18 possible symptom choices the patients were presented in the survey. Sample characteristics are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Background characteristics and clinical variables

| All N=445 |

EMS n=227 |

SHD n=93 |

PHC n=64 |

ER n=61 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||||

| Age, years* | 66±11 | 66±11 | 64±11 | 67±11 | 66±10 |

| Gender, men | 336 (76) | 177 (78) | 62 (67) | 50 (78) | 47 (77) |

| Education, ≤9 years | 171 (39) | 91 (40) | 24 (26) | 26 (41) | 30 (49) |

| Current smoker | 104 (24) | 58 (26) | 20 (22) | 16 (25) | 10 (16) |

| Falling ill at home | 341 (77) | 178 (78) | 72 (77) | 45 (70) | 46 (75) |

| Being alone at symptom onset | 119 (27) | 60 (26) | 18 (19) | 24 (38) | 17 (28) |

| Falling ill during a weekend | 129 (29) | 67 (30) | 34 (37) | 8 (12) | 20 (33) |

| Falling ill during evening/night at 18:00–6:00 | 156 (36) | 86 (39) | 33 (36) | 14 (22) | 23 (38) |

| Distance to hospital, ≥50 km | 74 (17) | 42 (19) | 16 (17) | 8 (12) | 8 (13) |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | 55 (13) | 42 (18) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 9 (15) |

| Hypertension | 208 (47) | 103 (46) | 47 (51) | 33 (52) | 25 (41) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 22 (5) | 18 (8) | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Heart failure | 12 (3) | 11 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Diabetes | 68 (15) | 29 (13) | 20 (22) | 10 (16) | 9 (15) |

| Stroke | 8 (2) | 4 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Believing symptoms originated from the heart | 295 (66) | 167 (74) | 51 (55) | 38 (59) | 39 (64) |

| Chest pain | 390 (88) | 207 (91) | 77 (83) | 54 (84) | 52 (85) |

| Cardinal symptoms† | 436 (98) | 225 (99) | 89 (96) | 62 (97) | 60 (98) |

| Pain intensity, numeric rating scale* | 6.8±2.1 | 7.2±2.0 | 6.2±2.3 | 6.6±1.8 | 6.7±1.9 |

| Symptom burden* | 5.3±2.5 | 5.6±2.6 | 5.3±2.4 | 4.9±2.3 | 4.7±2.1 |

Data are presented as numbers (percentages) if not otherwise indicated.

*Data are presented as mean±SD.

†Chest pain and/or radiating pain in the arms and/or cold sweat.

EMS, Emergency Medical Services; ER, emergency room; PHC, Primary Healthcare Centre; SHD, Swedish Healthcare Direct.

First medical contact

In total, 227 patients (51%) turned to the EMS as their FMC, 21% utilised the SHD, while 14% chose to contact their primary healthcare centre, and 14% went directly to the ER. When comparing those turning to the SHD as FMC with all other patients, those were more often women (33% vs 22%, p<0.05), had a higher education (74% vs 58%, p<0.01), had more seldom a history of MI (5% vs 14%, p<0.05), experienced more often pain in throat/neck (33% vs 18%, p<0.01), did more seldom believed the symptoms originated from the heart (55% vs 69%, p<0.01), and rated their pain on the numeric rating scale (NRS) as less severe (6.2 vs 7.0, p<0.001).

Patients utilising the EMS had more frequently a history of MI (18% vs 7%, p<0.001), chronic heart failure (5% vs 1%, p<0.01) and atrial fibrillation (8% vs 2%, p<0.01). They more often experienced chest pain (91% vs 84%, p<0.01), radiating pain (63% vs 49%, p<0.01), numbness in the arms (36% vs 25%, p<0.01) and cold sweat (65% vs 55%, p<0.05). They interpreted the symptoms as originated from the heart more often (74% vs 59%, p<0.001), rated their pain as more severe on the NRS (7.2 vs 6.5, p<0.001), and had a higher symptom burden (5.6 vs 5.0, p<0.05). There were no significant differences with respect to age, co-habiting status, contextual factors (ie, time of symptom onset (time of day or weekday), alone or not when falling ill) and utilisation of the EMS or the SHD in the bivariate analyses.

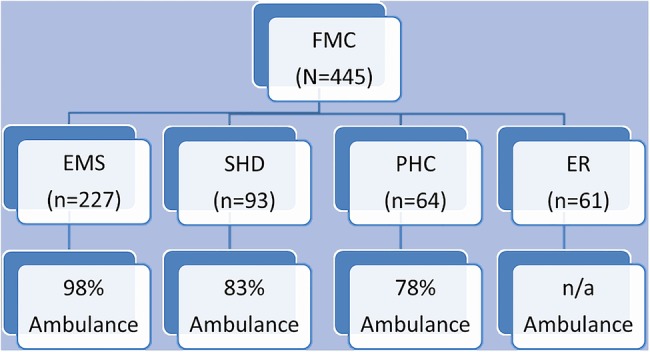

Of the 445 patients with STEMI included in the study, 83% finally arrived at the hospital by ambulance (figure 1), but only 21% of those patients called themselves. Among the 17% self-transported patients, the reasons for this decision were predominantly (1) my transport mode was faster (40%), (2) did not consider myself sick enough (30%) and (3) it was easier to be driven or taking a taxi (25%).

Figure 1.

Proportions of patients arriving at the hospital by ambulance, divided into first medical contact (FMC). EMS, Emergency Medical Services; ER, emergency room; PHC, Primary Healthcare Centre; SHD, Swedish Healthcare Direct.

Factors associated with the FMC

To determine variables that were independently associated with the FMC, two separate multiple logistic regression models were developed (ie, SHD and EMS). The probability of utilising healthcare advice via telephone was associated with female gender, having a higher education, a history of diabetes, experiencing pain in the throat/neck, and experiencing lower pain intensity (table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of using SHD as FMC,* n=426

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p Value | R2 change | Total R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: Sociodemographics | 0.052 | 0.081 | |||

| Gender, female | 1.92 | 1.01 to 3.66 | 0.05 | ||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.96 to 1.01 | 0.35 | ||

| Marital status, co-habiting | 1.45 | 0.84 to 2.51 | 0.18 | ||

| Education, >9 years | 2.40 | 1.32 to 4.35 | 0.01 | ||

| Block 2: Comorbidities | 0.080 | 0.124 | |||

| Diabetes | 2.10 | 1.06 to 4.16 | 0.03 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 0.45 | 0.16 to 1.29 | 0.14 | ||

| Heart failure | 0.00 | 0.00 to 00 | 0.99 | ||

| Block 3: Symptomatology | 0.120 | 0.186 | |||

| Chest pain | 0.88 | 0.40 to 1.95 | 0.76 | ||

| Pain in the neck/throat | 2.24 | 1.19 to 4.23 | 0.01 | ||

| Radiating pain in the arm(s) | 0.74 | 0.41 to 1.32 | 0.31 | ||

| Pain intensity, on the NRS | 0.85 | 0.75 to 0.97 | 0.01 | ||

| Symptom burden | 0.98 | 0.86 to 1.11 | 0.69 | ||

| Symptom interpretation, ie, from the heart | 0.72 | 0.42 to 1.23 | 0.23 | ||

| Block 4: Contextual factors | 0.131 | 0.203 | |||

| Alone when falling ill | 0.58 | 0.31 to 1.09 | 0.09 | ||

| Falling ill during a weekend | 1.46 | 0.86 to 2.51 | 0.16 | ||

| Symptom onset, between 18:00–6:00 | 0.91 | 0.53 to 1.58 | 0.74 |

Omnibus p Value <0.001.

*Regression conducted using hierarchical logistic regression.

FMC, first medical contact; NRS, numeric rating scale; SHD, Swedish Healthcare Direct.

With regard to the probability of contacting the EMS as FMC, those with a history of atrial fibrillation or MI, and believing that the symptoms were originating from the heart were more likely to call for an ambulance, while those having pain in their stomach were more likely not to do so (table 3). No sociodemographic or contextual factors were independently associated with the outcomes.

Table 3.

Predictors of using EMS as FMC,* n=422

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p Value | R2 change | Total R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: Sociodemographics | 0.008 | 0.010 | |||

| Gender, female | 0.64 | 0.37 to 1.10 | 0.11 | ||

| Age | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.04 | 0.10 | ||

| Marital status, co-habiting | 1.09 | 0.71 to 1.67 | 0.70 | ||

| Education, >9 years | 0.92 | 0.59 to 1.45 | 0.73 | ||

| Block 2: Comorbidities | 0.053 | 0.071 | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.81 | 1.14 to 12.74 | 0.03 | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 2.18 | 1.03 to 4.62 | 0.04 | ||

| Heart failure | 3.52 | 0.36 to 34.54 | 0.28 | ||

| Block 3: Symptomatology | 0.125 | 0.167 | |||

| Chest pain | 1.21 | 0.60 to 2.44 | 0.60 | ||

| Pain in the stomach | 0.35 | 0.14 to 0.87 | 0.02 | ||

| Radiating pain in the arm(s) | 1.53 | 0.94 to 2.47 | 0.08 | ||

| Cold sweat | 1.40 | 0.88 to 2.26 | 0.16 | ||

| Pain intensity, on the NRS | 1.10 | 0.99 to 1.24 | 0.08 | ||

| Symptom burden | 1.08 | 0.96 to 1.21 | 0.21 | ||

| Symptom interpretation, ie, from the heart | 1.60 | 1.02 to 2.52 | 0.04 | ||

| Block 4: Contextual factors | 0.127 | 0.169 | |||

| Alone when falling ill | 1.08 | 0.66 to 1.74 | 0.77 | ||

| Falling ill during a weekend | 1.15 | 0.73 to 1.81 | 0.55 | ||

| Symptom onset, between 18:00–6:00 | 1.15 | 0.74 to 1.78 | 0.54 |

Omnibus p Value <0.001.

*Regression conducted using hierarchical logistic regression.

EMS, Emergency Medical Services; FMC, first medical contact; NRS, numeric rating scale.

Time interval from symptom onset to FMC

Median delay time of the patients with STEMI was 1 h and 10 min (Q1 0:30; Q3 2:58), with 56% delaying ≥1 h from symptom onset to FMC. Those who turned to the EMS had the shortest delay time (median 57 min), while the corresponding time for those contacting the SHD was 1 h and 14 min (p=0.08). All time intervals are given in more detail in table 4.

Table 4.

Delay times from symptom onset to first medical contact (FMC), from FMC to diagnosis (ie, ECG), and total delay time, n=429

| Median | 25th Centile | 75th Centile | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient delay time | ||||

| Symptom onset to FMC | ||||

| Emergency Medical Services | 0:57 | 0:25 | 1:44 | |

| Swedish Healthcare Direct | 1:14 | 0:27 | 3:25 | 0.08 |

| Primary Healthcare Centre (direct) | 1:30 | 0:30 | 3:42 | 0.06 |

| Primary Healthcare Centre (telephone) | 3:57 | 1:22 | 27:54 | <0.001 |

| Emergency room | 2:33 | 1:06 | 5:45 | <0.001 |

| System delay time | ||||

| FMC to diagnosis | ||||

| Emergency Medical Services | 0:24 | 0:15 | 0:39 | |

| Swedish Healthcare Direct | 0:45 | 0:26 | 1:15 | <0.001 |

| Primary Healthcare Centre (direct) | 0:37 | 0:11 | 1:17 | 0.11 |

| Primary Healthcare Centre (telephone) | 1:05 | 0:32 | 2:42 | <0.001 |

| Emergency room | 0:11 | 0:07 | 0:25 | <0.001 |

| Total delay time | ||||

| Symptom onset to diagnosis | ||||

| Emergency Medical Services | 1:21 | 0:54 | 2:33 | |

| Swedish Healthcare Direct | 1:59 | 1:10 | 4:11 | <0.001 |

| Primary Healthcare Centre (direct) | 2:07 | 1:11 | 5:46 | <0.01 |

| Primary Healthcare Centre (telephone) | 5:02 | 1:58 | 29:33 | <0.001 |

| Emergency room | 2:44 | 1:32 | 6:48 | <0.001 |

*Comparison (Mann-Whitney U test) between Emergency Medical Services and all other first medical contacts.

Time interval from FMC to diagnosis

The system median delay time from FMC to diagnosis (ie, ECG) was 27 min (Q1 0:15; Q3 0:50). Patients turning to ER directly had the shortest time to diagnosis (median 11 min), while those contacting the SHD had a significantly longer time to diagnosis when compared with those contacting the EMS (45 vs 24 min, respectively, p<0.001). The choice of FMC and its impact on system delay times are given in more detail in table 4.

Discussion

Much research attention has focused on describing reasons why patients delay and factors that are associated with the same.11 However, this body of research lacks detailed information on patients’ FMC and its impact on delay times. We found that only half of the patients turned to the EMS as their FMC. This is disappointing since the EMS is a critical component of the STEMI chain of survival.1 A rapid diagnosis with prehospital ECG and transfer to a primary PCI centre has recently been found to be associated with a reduction in total ischaemic times.12–14 In our study, as many as every fifth patient with an ongoing STEMI utilised the SHD for healthcare advice, instead of contacting the EMS as their first action. This is worrying; even though the patients were urged to call the EMS immediately after speaking with the advisement nurse—or the nurse themself contacted the EMS—17% did not do so, and the time to diagnosis was nearly doubled for those hesitating to contact the EMS as their first action. Many non-callers reported that they did not think that their symptoms were severe enough to merit a drastic action such as calling the EMS or they believed that self-transport would be faster. These reasons for self-transportation has been described previously15 16 and is also in agreement with earlier Swedish research.17 18 Furthermore, our results showed that sociodemographic characteristics were significant determinants of the intention to use a telephone service, with women and higher educated individuals more frequently using the SHD compared with their counterpart. Also others19 20 have found the usage of a public healthcare advice service being more prominent in women.

In Sweden, for one decade efforts have been done to educate the citizens about the possibility to contact an advisement nurse by telephone instead of seeking immediate care at the ER or general practitioner (GP) when being in need of healthcare advice for non-life-threatening symptoms. Also other countries have the same services, for example the National Health Service Choices that is the UK's biggest health website.21 However, the results from our study indicate that these efforts may have been ‘too successful’ when it comes to patients experiencing STEMI symptoms. On the contrary, we do not know which action the individual had chosen if this service not had been available. We can assume that it has been a shift from contacting the general practitioner (GP) to contact an advisement nurse instead. This assumption is strengthen by findings from a previous Swedish study on chest pain patients—conducted before the joint service number era—where the authors found that as many as one-third of the patients contacted their GP as their FMC.9 In our study the equivalent number was 14%. Perhaps the patient's prehospital delay in our study should have been even longer without those possibilities to discuss symptoms and actions. Even though it is clearly stated in the SHD's guidelines that “in case of emergency one should call the EMS instead of waiting for the nurse to answer the call,” a person who already is uncertain about the symptoms and wants to discuss them, would probably not do so. Reasons for discussing symptoms with healthcare professionals are likely to be cognitive (ie, beliefs about symptoms, eg, something is wrong/serious), the consequences of symptoms (eg, interference of symptoms with one's ability to work), perceived inability to cope with symptoms (eg, persistence, failure of self-medication) or emotional (eg, anxiety, concern, need for reassurance).22

Any effort must be made to keep the respective time intervals between the onset of symptoms and the beginning of reperfusion therapy as short as possible. Unfortunately, we found that too many patients still hesitate to immediately call the EMS, contributing to a delayed symptom-to-diagnosis interval of 38 min when comparing EMS and SHD as the patient’s first choice. More intense measures must therefore be taken to educate the public about the positive effects of an early and correct first action with an exclusive use of the EMS when suspecting an MI. Furthermore, our results also underline the necessity of even more specifying the targeted group when introducing a new healthcare provider (such as SHD) in a healthcare system. However, introducing a low-threshold number in the society might also, in some instances, increase STEMI awareness among patients who otherwise might have delayed even longer.

Limitations

This study has some limitations which may limit the generalisability of our results. First, it was an observational study and thus we can only report association rather than infer causation. Second, as the patient had to be pain free and haemodynamically stable before they could participate in the study, they could be included in the study within 24 h after admittance, and thus a possibility of recall bias in some cases cannot be excluded. Finally, the self-reported questionnaire used in this study is only available in Swedish, which can make comparisons with other studies difficult. Despite these limitations, this study offers a new insight into how FMC of patients with STEMI may contribute to treatment delay.

Conclusion

Although 83% of the patients with an evolving STEMI arrived by ambulance at the hospital, this study emphasise that just half of the patients called the EMS as their FMC. Instead, every fifth patient contacted an advisement nurse by phone, causing a median difference of 21 min from FMC to diagnosis. Further research is required to examine the underlying factors that contribute to the variation in utilisation of these services. This will enable the development of future promotional campaigns that can target particular sections of the population to encourage use of telephone-based healthcare services only in a non-emergency situation. The general public must be taught that the symptoms connected with an evolving STEMI need not to be severe, and that a less severe pain is also a reason to contact the ambulance service instead of a telephone-based healthcare service.

Footnotes

Contributors: IT and SSL contributed to the study design, data analysis. ME, KHÄ and R-MI contributed to the data collection. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation.

Funding: This work was supported by the Medical Research Council of Southeast Sweden (FORSS, grant number 161061).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethical Review Board, Linköping, Sweden (D-nr 2012/201-31).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: on behalf of the SymTime study group

References

- 1.Steg PG, James SK, Atar D et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2012;33:2569–619. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2541–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gershlick AH, Banning AP, Myat A et al. Reperfusion therapy for STEMI: is there a role for thrombolysis in the era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention? Lancet 2013;382:624–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61454-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladwig KH, Meisinger C, Hymer H et al. Sex and age specific time patterns and long term time trends of pre-hospital delay of patients presenting with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2011;152:350–5. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2909–45. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eklöf P. 1177 Swedish Healthcare Direct (Vårdguiden)—Health care advice online and on the phone. http://www.1177.se/Om-1177/1177–Health-care-advice-online-and-on-the-phone1/ (accessed 10 Apr 2014).

- 7.Jernberg T. SWEDEHEART Annual Report 2013. Huddinge, Stockholm: Karolinska University Hospital; http://www.ucr.uu.se/swedeheart/ [Google Scholar]

- 8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson I, Strömberg A, Swahn E. Factors related to delay times in patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung 2004;33:291–300. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg RJ, Mooradd M, Gurwitz JH et al. Impact of time to treatment with tissue plasminogen activator on morbidity and mortality following acute myocardial infarction (The second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction). Am J Cardiol 1998;1:259–64. 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00342-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen HL, Saczynski JS, Gore JM et al. Age and sex differences in duration of pre-hospital delay in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:82–92. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.884361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mumma BE, Kontos MC, Peng SA et al. Association between prehospital electrocardiogram use and patient home distance from the percutaneous coronary intervention center on total reperfusion time in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients: a retrospective analysis from National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Am Heart J 2014;167:915–20. 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roswell RO, Greet B, Parikh P et al. From door-to-balloon time to contact-to-device time: predictors of achieving target times in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol 2014;37:389–94. 10.1002/clc.22278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen MB, Frost L, Stengaard C et al. Diagnostic performance and system delay using telemedicine for prehospital diagnosis in triaging and treatment of STEMI. Heart 2014;100:711–15. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meischke H, Ho MT, Eisenberg MS et al. Reasons patients with chest pain delay or do not call 911. Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:193–7. 10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70323-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan HB, Song L, Chen H et al. Factors influencing ambulance use in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction in Beijing, China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:272–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartford M, Karlsson BW, Sjölin M et al. Symptoms, thoughts and environmental factors in suspected acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung 1993;22:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson I, Strömberg A, Swahn E. Ambulance use in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2004;19:5–12. 10.1097/00005082-200401000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ybarra M, Suman M. Help seeking behavior and the Internet: a national survey. Int J Med Inform 2006;75:29–41. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cook EJ, Randhawa G, Large S et al. A UK case study of who uses NHS direct: investigating the impact of age, gender, and deprivation on the utilization of NHS direct. Telemed J E Health 2012;18:693–8. 10.1089/tmj.2011.0256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Health Service (NHS) Choices Annual Report 2012/13. http://www.nhs.uk/annualreport (accessed 21 Jul 2014).

- 22.Scott SE, Walter FM, Webster A et al. The Model of Pathways to Treatment: conceptualization and integration with existing theory. Br J Health Psychol 2013;18:45–64. 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]