Abstract

Objective

Low levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] are commonly found in type 2 diabetes. We examined whether there is an association between circulating 25(OH)D concentrations and the presence of microvascular complications in people with type 2 diabetes.

Research design and methods

We studied 715 outpatients with type 2 diabetes who regularly attended our clinic. Participants were evaluated for the presence of microvascular complications (namely retinopathy and/or nephropathy) by clinical evaluation, fundus examination, urine examination and biochemical tests. Serum 25(OH)D levels were also measured for each participant.

Results

Hypovitaminosis D (ie, a serum 25(OH)D level <30 ng/mL) was found in 75.4%, while deficiency (ie, a 25(OH)D level <20 ng/mL) was found in 36.6% of these patients. Serum 25(OH)D levels decreased significantly in relation to the severity of either retinopathy or nephropathy or both. In multivariate logistic regression analysis, lower 25(OH)D levels were independently associated with the presence of microvascular complications (considered as a composite end point; OR 0.758; 95% CI 0.607 to 0.947, p=0.015). Notably, this association remained significant even after excluding those with an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Conclusions

We found an inverse and independent relationship between circulating 25(OH)D levels and the prevalence of microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, vitamin D may be simply a marker and causality cannot be implied from our cross-sectional study. Whether vitamin D supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes may have beneficial effects on the risk of microvascular complications remains to be investigated.

Keywords: Microangiopathy, Microvascular Complications, Vitamin D

Key messages.

Low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D are commonly found in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Lower levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D are strongly associated with a greater prevalence of microvascular complications (retinopathy and/or nephropathy) in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Lower levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D are significantly associated with the presence of diabetic retinopathy and/or abnormal albuminuria even after excluding those with an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] are commonly found in people with type 2 diabetes.1 2 A significant association between lower serum 25(OH)D levels and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality has been reported in different patient populations, including individuals with type 2 diabetes.3 4 The presence of microvascular complications may predict an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.5 6 It is well established that poor glycemic control, hypertension, and longer duration of diabetes are among the strongest risk factors for the development and progression of microvascular complications, especially retinopathy and nephropathy.7 Some recent epidemiological studies suggested a significant association between low vitamin D status and increased prevalence of diabetic microangiopathy.8–10 However, an observational prospective study in 227 patients with type 1 diabetes showed that severe vitamin D deficiency independently predicted all-cause mortality, but not development of diabetic retinopathy or nephropathy.11 Currently, there are limited data on the relationship between vitamin D status and microvascular complications in large samples of patients with type 2 diabetes. An observational study in 581 Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes reported a significant inverse association between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of microvascular complications.12 However, in this study, the independence of this association was not examined in a multivariable regression model.

Therefore, in this study, we examined whether there is a significant relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and/or nephropathy in a large cohort of well-characterized patients with type 2 diabetes. In particular, we assessed whether serum 25(OH)D levels are independent predictors of the presence of these microvascular complications in a multivariable regression model.

Research design and methods

For this analysis, we recruited 715 outpatients with type 2 diabetes, who regularly attended our clinic and had a serum 25(OH)D measurement available during the years 2011–2012. The mean age of these patients was 68±12 years (range 26–94 years) with 61% of women. Patients were classified as having type 2 diabetes if the diagnosis was made after age 35 years irrespective of treatment, or irrespective of age of diagnosis if they were treated with diet and/or hypoglycemic drugs. No patients had overt cirrhosis or chronic renal failure. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent for this study was not obtained (and was exempted by the local ethics committee) because de-identified data were analyzed.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. Blood pressure was measured with a standard mercury manometer. Venous blood was drawn in the morning after an overnight fast in all patients. Serum creatinine (measured using a Jaffé rate-blanked and compensated assay), lipids, calcium, and other biochemical blood measurements were determined by standard laboratory procedures (DAX 96; Bayer Diagnostics, Milan, Italy). Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured according to the Standard Operating Procedure of the IFCC Reference, by an automated high-performance liquid chromatography analyzer (Bio-Rad Diamat, Milan, Italy); the upper limit of normality for our laboratory was 5.8%. Serum 25(OH)D concentrations were measured using a chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA, DiaSorin Liaison, Stillwater, USA) with a coefficient of variation of 8.6%. The season for vitamin D measurements was coded as 0 from April to September and as 1 from October to March. Serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels were measured on Elecsys 2010 by an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH).

Patients were considered to have arterial hypertension if their blood pressure values were ≥140/90 mm Hg or they were taking any antihypertensive drugs. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (e-GFR) was estimated from the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation.13 The urinary albumin excretion rate was measured from a 24 h urine sample by an immunonephelometric method. The presence of abnormal albuminuria (defined as urinary albumin excretion rate >30 mg/day) was confirmed in at least two of three consecutive samples. Nephropathy was defined as the presence of abnormal albuminuria (microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria) and/or e-GFRMDRD <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The presence of diabetic retinopathy was diagnosed with indirect ophthalmoscopy after pupillary dilation by a single ophthalmologist. Diabetes treatment was categorized in the diet, oral agents or insulin alone or associated with oral agents.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means±SD or proportions. Skewed variables (ie, diabetes duration, triglycerides, and 25(OH)D level) were logarithmically transformed to improve normality prior to analysis. The unpaired Student t test, one-way analysis of variance, and the χ2 test with Yates correction for continuity were used to analyze the differences among the clinical and biochemical characteristics of participants. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was also performed to test the independent association of the serum 25(OH)D level with the presence of microvascular complications (ie, the dependent variable). Two forced-entry multivariate regression models were performed. The dependent variable was included as a composite end point: patients with neither retinopathy nor nephropathy (coded as 0) and patients with both complications or with one or the other (coded as 1). Covariates were chosen as potential confounding factors on the basis of their significance in univariate analysis or on the basis of their biological plausibility. Results are presented as ORs with 95% CIs. ORs for all continuous variables were computed for each SD increase. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS V.19.0 statistical package software. p Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The median serum 25(OH)D level was 19.6 ng/mL (IQR 12.0–29.6 ng/mL) among the study participants. Hypovitaminosis D (defined as a serum 25(OH)D level <30 ng/mL) was present in 539 patients (75.4%), whereas 262 patients (36.6%) had a serum 25(OH)D level <20 ng/mL, configuring a state of vitamin D deficiency.

As shown in table 1, patients with diabetes with hypovitaminosis D were younger and had lower low density-lipoprotein cholesterol and higher values of BMI, diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides and triglycerides-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, and serum PTH than their vitamin D-sufficient counterparts. Notably, patients with hypovitaminosis D also had significantly greater frequencies of diabetic retinopathy (any degree) and nephropathy, principally abnormal albuminuria. No significant differences were observed in sex distribution, duration of diabetes, HbA1c, calcium, uric acid level, and e-GFR level between the groups.

Table 1.

Main clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients with type 2 diabetes grouped by vitamin D status

| 25(OH)D <30 ng/mL | 25(OH)D ≥30 ng/mL | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 539 | 176 | – |

| Sex (M/F) | 212/327 | 63/113 | 0.228 |

| Age (years) | 67±13 | 73±9 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.1±8.1 | 28.7±5.9 | <0.001 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 10±10 | 11±10 | 0.185 |

| Systolic pressure (mm Hg) | 138.4±19.1 | 137.7±18.1 | 0.683 |

| Diastolic pressure (mm Hg) | 81.1±11.1 | 78.6±9.5 | 0.005 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.6±1.8 | 7.4±1.3 | 0.114 |

| e-GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 75.6±24.1 | 73.3±17.6 | 0.220 |

| Uric acid (mmol/L) | 0.43±0.7 | 0.45±0.8 | 0.845 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.3±0.5 | 1.4±0.5 | 0.097 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.6±0.8 | 2.8±0.8 | 0.043 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.7±0.9 | 1.5±0.8 | 0.010 |

| TG/HDL-C ratio | 1.5±1.2 | 1.2±0.9 | 0.010 |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/mL) | 63.2±53.5 | 42.2±41.0 | 0.002 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 9.3±0.5 | 9.3±0.8 | 0.781 |

| Retinopathy, any degree (%) | 34% | 24% | 0.018 |

| Nephropathy (%) | 64% | 53% | 0.020 |

| Abnormal albuminuria (%) | 27% | 15% | 0.048 |

| e-GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (%) | 25% | 22% | 0.287 |

Continuous variables are reported as means±SD, and categorical variables as absolute or relative frequencies. Two tails Student t test or χ2 test have been employed to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; BMI, body mass index; e-GFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; F, female; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; M, male; TG, triglycerides.

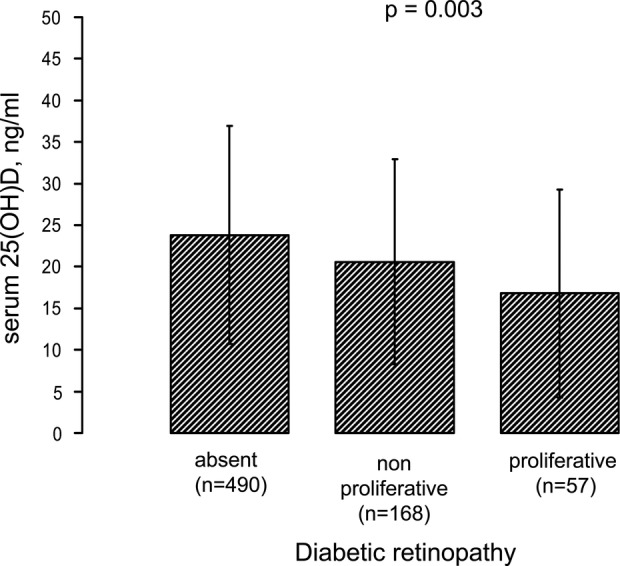

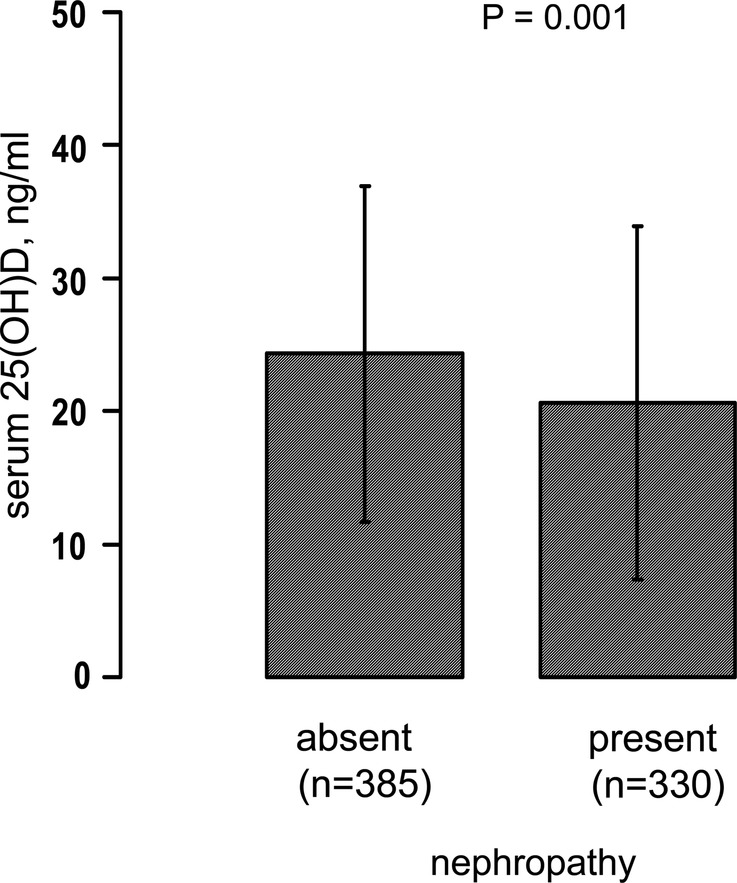

As shown in figure 1, there was an inverse graded relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and the severity of diabetic retinopathy (data were adjusted for age). A similar trend (figure 2) was also observed when patients were grouped by nephropathy status; patients with diabetes with nephropathy (defined as abnormal albuminuria and/or e-GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) had significantly lower age-adjusted levels of serum 25(OH)D than those without nephropathy.

Figure 1.

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels stratified by clinical grades of diabetic retinopathy. Data are adjusted for age and reported as means±SD.

Figure 2.

Serum 25(OH)D levels stratified by the presence or absence of nephropathy. The presence of nephropathy was defined as abnormal albuminuria (urinary albumin excretion rate >30 mg/day) and/or e-GFRMDRD <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Data are adjusted for age and reported as means±SD. 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; e-GFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease.

To further examine the relationship between serum 25(OH)D levels and microvascular complication status, we performed multivariable logistic regression analyses in which the presence of microvascular complications, that is, the dependent variable, was defined as a composite measure inclusive of retinopathy and/or nephropathy. Results of two forced-entry logistic regression models are showed in table 2. Higher serum 25(OH)D levels were independently associated with a reduced risk of prevalent microvascular complications (OR 0.758; 95% CI 0.607 to 0.947, p=0.015 for each SD increase in 25(OH)D level (ie, 13 ng/mL)). Notably, other independent predictors of microvascular complications were male sex, older age, higher HbA1c, longer duration of diabetes, and higher systolic blood pressure (table 2).

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression analyses showing the association of serum 25(OH)D levels with the presence of the composite microvascular end point, inclusive of diabetic retinopathy and/or nephropathy

| Regression model 1 |

Regression model 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 0.723 | 0.599 to 0.871 | 0.001 | 0.758 | 0.607 to 0.947 | 0.015 |

| Sex (M vs F) | 2.430 | 1.651 to 3.577 | <0.001 | 2.315 | 1.443 to 3.715 | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.977 | 1.559 to 2.507 | <0.001 | 2.013 | 1.473 to 2.750 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.180 | 0.927 to 1.502 | 0.180 | 1.086 | 0.788 to 1.497 | 0.616 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 1.263 | 1.001 to 1.594 | 0.049 | |||

| HbA1c (%) | 1.603 | 1.219 to 2.108 | 0.001 | |||

| TG/HDL-C ratio | 1.072 | 0.842 to 1.364 | 0.573 | |||

| Diabetes duration (years) | 2.341 | 1.741 to 3.147 | <0.001 | |||

| Season measurement (winter) | 1.474 | 0.934 to 2.328 | 0.096 | |||

A composite microvascular complication end point was present in 401 patients. All continuous variables included in the two regression models were modeled for each SD increase.

25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; BMI, body mass index; F, female; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; M, male; TG, triglyceride.

Lastly, as a sensitivity analysis, we performed the above logistic regression analyses after excluding those (n=170) with e-GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Also in this case, the serum 25(OH)D level was inversely associated with the presence of microvascular complications (ie, retinopathy and/or abnormal albuminuria), independently of potential confounding variables (OR 0.689, CI 95% 0.532 to 0.892; p=0.005 for each SD increase in vitamin D).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we assessed the association between circulating 25(OH)D levels and the presence of diabetic retinopathy and/or nephropathy in a large outpatient cohort of individuals with type 2 diabetes.

In accord with previous studies,1 2 14 we found that the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency (75.4%) or deficiency (36.6%) is very high in people with type 2 diabetes. Vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency is a growing epidemic condition worldwide.15 16 Using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1988–1984 and NHANES 2001–2004 databases, Ginde et al17 showed a significant decreasing trend in serum 25(OH) levels in the US population. Accordingly, Lippi et al18 found that low serum 25(OH)D levels are commonly found in a large cohort of unselected outpatients, who lived in the same geographical area of patients enrolled in our study. In particular, they found that a serum 25(OH)D level <30 ng/mL was present in approximately 50% of men and women aged >60 years. Similar findings have been reported by other investigators among 6403 unselected medical inpatients and outpatients, who attended the laboratory Hospital of Vicenza, a town in Northern Italy.19

The main finding of our study indicates that there was a significant inverse association between circulating vitamin D concentrations and the presence of diabetic retinopathy and/or nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. This association was independent of a broad number of potential confounders, such as season measurement, age, sex, duration of diabetes, BMI, blood pressure, HbA1c, and plasma lipids. Comprehensively, the rate of these microvascular complications was reduced by approximately 25% for each SD increase (ie, 13 ng/mL) in serum 25(OH)D level. Of interest, this inverse and independent association was maintained even when the analysis was restricted only to participants with e-GFR above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Collectively, our findings confirm and extend the results of some previous smaller studies showing an inverse, significant relationship between low vitamin D status and the presence of diabetic microvascular complications.8–10 12 20 Indeed, we examined a large cohort of outpatients with well-characterized type 2 diabetes and were able to adjust for important confounders. A previous study on 581 Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes found an inverse, significant association between serum 25(OH)D levels and the number of microvascular complications.12 Vitamin D deficiency was also associated with self-reported peripheral neuropathy symptoms in relatively small samples of patients with type 2 diabetes.21 22 Furthermore, a significant association between hypovitaminosis D and albuminuria has also been reported;23 however, in a small randomized clinical trial, vitamin D supplementation was ineffective in ameliorating proteinuria in patients with diabetes with proven nephropathy, who received vitamin D for a period of 3 months.24 A recent study on 517 young patients with type 1 diabetes reported a significant inverse association of serum 25(OH)D levels with retinopathy, in accord with our results.25

Therefore, all these findings suggest that lower 25(OH)D levels and microvascular complications (principally diabetic retinopathy and nephropathy) are strictly inter-related. However, whether low vitamin D status is the cause or result of the presence of microvascular complications is presently unknown. Among the putative biological mechanisms that might underlie this association, at least two deserve attention: neoangiogenesis and chronic inflammation.15 Calcitriol [1,25(OH)2D] was a powerful inhibitor of angiogenesis both in mouse models of retinopathy and in in vitro studies on retinal endothelial cells.26 27 Calcitriol was also a potent inhibitor of tumor cell-induced angiogenesis.28 The effect of vitamin D on angiogenesis might be mediated by the interaction with the vitamin D receptor (VDR). It has been demonstrated that VDR is present in the human retina, and VDR polymorphisms are closely related to retinopathy risk in patients with type 1 diabetes.29 A significant inverse association between serum 25(OH)D levels and plasma C reactive protein was reported in US adults.30 However, studies with vitamin D supplementation were unable to show any significant changes in plasma inflammatory biomarkers.31 32

On the other hand, experimental studies have suggested a possible detrimental effect of low levels of serum 25(OH)D on the progression of nephropathy. Diabetic VDR knockout mice developed more severe albuminuria and glomerulosclerosis compared with diabetic wild-type mice.33 Some in vitro studies also suggested that calcitriol may protect the kidney by other potential deleterious mechanisms, such as the reduction of expression of transforming growth factor-β, fibronectin, renin, angiotensinogen, and NF-κB.34 35 Of interest, some small intervention studies in humans have also reported that, in the short term (4 months), dietary vitamin D repletion with cholecalciferol had a beneficial effect in delaying the progression of diabetic nephropathy above that due to the established renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition.36 Finally, a recent meta-analysis suggested that the FokI polymorphism in the VDR gene might affect individual susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy in Caucasian individuals.37 However, it is important to remark that there is currently insufficient evidence of beneficial effect to recommend vitamin D supplementation as a means of reducing the development or delaying the progression of microvascular complications in patients with diabetes. In addition, recent systemic reviews and meta-analyses reported that although several observational studies showed a strong association of low vitamin D concentrations with mortality risk and occurrence of osteoporotic fractures, falls, and various non-skeletal diseases, the results of myriad recent randomized controlled trials are almost unanimous in concluding that vitamin D supplementation provides protection from few, if any, of these outcomes.38–40 Thus, it looks increasingly likely that low vitamin D is not a cause but a marker of ill health.

Our study has some important limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes making any causal inferences about the relationship between low 25(OH)D levels and microvascular complications of diabetes. Second, we did not measure 1,25-di-idroxyvitamin D levels, and nor did we have any information about the use of vitamin D supplements among these participants. Finally, as in all observational studies, we cannot a priori exclude that hidden biases or the inability to account for all factors related to vitamin D metabolism might have limited our multivariate approach. Notwithstanding these limitations, our study has some important strengths, such as the large sample size, the availability of extensive data on multiple covariates, and the completeness of the data set.

In conclusion, the results of this cross-sectional study indicate that there is an inverse and independent association between circulating 25(OH)D levels and the presence of diabetic retinopathy and/or nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Whether vitamin D supplementation in people with type 2 diabetes may exert any beneficial effects on the development and progression of these microvascular complications is still a matter of intense debate. Future large randomized controlled trials are needed to improve an understanding of this issue.

Footnotes

Contributors: GZ and GT wrote the manuscript and analyzed the data. AG and CN researched the data and contributed to discussions. CB, FDS, VS, and VC researched the data. IP, MT, and EB reviewed the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee of the Verona University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Koshiyama H, Ikeda H, Honjo S et al. Hypovitaminosis D is frequent in Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2007;76:470–1. 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isaia G, Giorgino R, Adami S. High prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in female type 2 diabetic population. Diabetes Care 2001;24:1496–500. 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joergensen C, Gall MA, Schmedes A et al. Vitamin D levels and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2238–43. 10.2337/dc10-0582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Y, Zhu J, Zhou M et al. Meta-analysis of long-term vitamin D supplementation on overall mortality. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e82109 10.1371/journal.pone.0082109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soedamah-Muthu SS, Chaturvedi N, Witte DR, et al. EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study Group . Relationship between risk factors and mortality in type 1 diabetic patients in Europe: the EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study (PCS). Diabetes Care 2008;31:1360–6. 10.2337/dc08-0107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Targher G, Zoppini G, Chonchol M et al. Glomerular filtration rate, albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetic individuals. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011;21:294–301. 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev 2013;93:137–88. 10.1152/physrev.00045.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patrick PA, Visintainer PF, Shi Q et al. Vitamin D and retinopathy in adults with diabetes mellitus. Arch Ophthalmol 2012;130:756–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aksoy H, Akçay F, Kurtul N et al. Serum 1,25 dihydroxy-vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D3), 25 hydroxy-vitamin D (25(OH)D) and parathormone levels in diabetic retinopathy. Clin Biochem 2000;33:47–51. 10.1016/S0009-9120(99)00085-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diaz VA, Mainous AG, Carek PJ et al. The association of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency with diabetic nephropathy: implications for health disparities. J Am Board Fam Med 2009;22:521–7. 10.3122/jabfm.2009.05.080231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joergensen C, Hovind P, Schmedes A et al. Vitamin D levels, microvascular complications, and mortality in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1081–5. 10.2337/dc10-2459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki A, Kotake M, Ono Y et al. Hypovitaminosis D in type 2 diabetes mellitus: association with microvascular complications and type of treatment. Endocr J 2006;53:503–10. 10.1507/endocrj.K06-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T et al. Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med 2010;354:2473–83. 10.1056/NEJMra054415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cigolini M, Iagulli MP, Miconi V et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 concentrations and prevalence of cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2006;29:722–4. 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-2148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hossein-nezhad A, Holick MF. Vitamin D for health: a global perspective. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88:720–55. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Targher G, Pichiri I, Lippi G. Vitamin D, thrombosis, and hemostasis: more than skip deep. Semin Thromb Hemost 2012;38:114–24. 10.1055/s-0031-1300957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA. Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:626–32. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lippi G, Montagnana M, Meschi T et al. Vitamin D concentration and deficiency across different ages and genders. Aging Clin Exp Res 2012;24:548–51. 10.3275/8263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cigolini M, Miconi V, Soffiati G et al. Hypovitaminosis D among unselected medical inpatients and outpatients in Northern Italy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;64:475 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Payne JF, Ray R, Watson DG et al. Vitamin D insufficiency in diabetic retinopathy. Endocr Pract 2012;18:185–93. 10.4158/EP11147.OR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soderstrom LH, Johnson SP, Diaz VA et al. Association between vitamin D and diabetic neuropathy in a nationally representative sample: results from 2001–2004 NHANES. Diabet Med 2012;29:50–5. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03379.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shehab D, Al-Jarallah K, Mojiminiyi OA et al. Does vitamin D deficiency play a role in peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes? Diabet Med 2012;29:43–9. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03510.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernández-Juárez G, Luño J, Barrio V et al. PRONEDI Study Group. 25(OH)-vitamin D levels and renal disease progression in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy and blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:1870–6. 10.2215/CJN.00910113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmadi N, Mortazavi M, Iraj B et al. Whether vitamin D3 is effective in reducing proteinuria in type 2 diabetic patients? J Res Med Sci 2013;18:374–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaur H, Donaghue KC, Chan AK et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with retinopathy in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1400–2. 10.2337/dc11-0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mantell DJ, Owens PE, Bundred NJ et al. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Circ Res 2000;87:214–20. 10.1161/01.RES.87.3.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert DM, Scheef EA, Wang S et al. Calcitriol is a potent inhibitor of retinal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007;48:2327–34. 10.1167/iovs.06-1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majewski S, Skopinska M, Marczak M et al. Vitamin D3 is a potent inhibitor of tumour cell-induced angiogenesis. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 1996;1:97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taverna MJ, Selam JL, Slama G. Association between a protein polymorphism in the start codon of the vitamin D receptor gene and severe diabetic retinopathy in C-peptide-negative type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:4803–8. 10.1210/jc.2004-2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amer M, Qayyum R. Relation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and C-reactive protein in asymptomatic adults (from the continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 to 2006). Am J Cardiol 2012;109:226–30. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jorde R, Strand Hutchinson M, Kjaergaard M et al. Supplementation with high doses of vitamin D to subjects without vitamin D deficiency may have negative effects: pooled data from four intervention trials in Tromso. ISRN Endocrinol 2013;2013:348705 10.1155/2013/348705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gepner AD, Ramamurthy R, Krueger DC et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial of the effects of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular disease risk. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e36617 10.1371/journal.pone.0036617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Sun L, Wang Y et al. Reno-protective role of the vitamin D receptor in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int 2008;73:163–71. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Yuan W, Sun L et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 targeting of NF-κB suppresses high glucose-induced MCP-1 expression in mesangial cells. Kidney Int 2007;72:193–201. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plum LA, Zella JB. Vitamin D compounds and diabetic nephropathy. Arch Biochem Biophys 2012;523:87–94. 10.1016/j.abb.2012.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim MJ, Frankel AH, Donaldson M et al. Oral cholecalciferol decreases albuminuria and urinary TGF-β1 in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy on established renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition. Kidney Int 2011;80:851–60. 10.1038/ki.2011.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Z, Liu L, Chen X et al. Associations study of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with diabetic microvascular complications: a meta-analysis. Gene 2014;546:6–10. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chowdhury R, Kunutsor S, Vitezova A et al. Vitamin D and risk of cause specific death: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort and randomised intervention studies. BMJ 2014;348:g1903 10.1136/bmj.g1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Autier P, Boniol M, Pizot C et al. Vitamin D status and ill health: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:76–89. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70165-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Gamble GD et al. Vitamin D supplementation and falls: a trial sequential meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:573–80. 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70068-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]