Abstract

Background

An increasing number of young women Veterans seek reproductive health care through the VA, yet little is known regarding the provision of infertility care for this population. The VA provides a range of infertility services for Veterans including artificial insemination, but does not provide in vitro fertilization. This study will be the first to characterize infertility care among OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans using VA care.

Methods

We analyzed data from the OEF/OIF/OND roster file from the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC)—Contingency Tracking System Deployment file of military discharges from October 1, 2001–December 30, 2010, which includes 68,442 women Veterans between the ages of 18 and 45 who utilized VA health care after separating from military service. We examined the receipt of infertility diagnoses and care using ICD-9 and CPT codes.

Results

Less than 2% (n = 1323) of OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans received an infertility diagnosis during the study period. Compared with women VA users without infertility diagnosis, those with infertility diagnosis were younger, obese, black, or Hispanic, have a service-connected disability rating, a positive screen for military sexual trauma, and a mental health diagnosis. Overall, 22% of women with an infertility diagnosis received an infertility assessment or treatment. Thirty-nine percent of women Veterans receiving infertility assessment or treatment received this care from non-VA providers.

Conclusions

Overall, a small proportion of OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans received infertility diagnoses from the VA during the study period, and an even smaller proportion received infertility treatment. Nearly 40% of those who received infertility treatments received these treatments from non-VA providers, indicating that the VA may need to examine the training and resources needed to provide this care within the VA. Understanding women’s use of VA infertility services is an important component of understanding VA’s commitment to comprehensive medical care for women Veterans.

Keywords: women’s health, Veterans, infertility

Increasing numbers of women Veterans are turning to the Veteran’s Health Administration (VHA) for health care after their return from Operations Enduring Freedom (OEF), Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and New Dawn (OND).1 Many OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans are of childbearing age and may be seeking care for issues related to pregnancy or infertility.2 Lifestyle factors that may impact reproductive health for women Veterans include delayed childbearing, obesity, inappropriate diet, smoking, psychological stress, and environmental toxins.3,4 Although some recent studies have documented the rising number of women relying on VHA maternity benefits for prenatal care and delivery,5 few studies have examined the degree to which women Veterans sought VA care for infertility issues.

Several previous studies have examined infertility among military Veterans following deployment.6-9 Other recent studies of OEF/OIF/OND Veterans using VA health care have documented higher rates of infertility among those with mental health diagnoses.10 Exposure to sexual assault, including military sexual trauma (MST), has been historically linked with self-reported infertility among women Veterans, perhaps explaining some of the association between mental health conditions (ie, posttraumatic stress disorder and depression diagnoses are common among women Veteran with MST).11,12 Most recently, Katon et al13 utilized national survey data to examine self-reported infertility among male and female OEF/OIF/OND Veterans, including VA users and nonusers, and found 15.8% of women and 13.8% of men reported a lifetime history of infertility.

Understanding women’s use of VA infertility services is an important component of understanding VA’s commitment to comprehensive medical care for women Veterans. Moreover, attending to the unique health care needs of women Veterans with sexual trauma exposure and mental health conditions associated with other exposures during military service is essential to the provision of high quality and sex equitable care for women Veterans. To this end, in recent years, the VA has launched efforts to ensure women receive comprehensive medical care at all of its facilities. However, because women remain a numeric minority in the VA, there is wide facility-level variation in the onsite availability of some sex-specific services. Recent studies suggest that though most VA facilities provide basic women’s health services,14,15 availability of advanced gynecologic care varies widely.13,15,16 Much of this variation is dependent on the size and complexity of the services offered at each specific VA medical facility, which is often driven by the volume of female Veterans using that facility for their health care. If sex-specific services are not available on-site, they are provided in the community through non-VA (fee) care or contract services. Furthermore, though the VA provides comprehensive infertility assessment and treatment for qualified Veterans, covered services do not include in vitro fertilization or services for non-Veteran spouses.17

The present work is a first step toward understanding utilization of VA infertility services for women OEF/OIF/OND Veterans. Specifically, our study objectives were to: (1) determine the prevalence of infertility diagnoses among OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans in VA care and (2) examine the factors that contribute to infertility treatment among those women Veterans with infertility diagnoses.

METHODS

Overview of Study Design and Data Sources

This retrospective cohort analysis included OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans of childbearing age who used VA care between October 1, 2001 and December 30, 2010. Data from the Department of Defense Manpower Data Center’s (DMDC) Contingency Tracking System roster was used and includes information on sex, race, date of birth, deployment dates, armed forces branch (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, or Coast Guard) and component (National Guard, Reserve, or active duty). Data from the OEF/OIF/OND roster were linked to VA’s National Patient Care Database (NPCD) and Decision Support Systems (DSS). The NPCD and DSS provide information on Veterans VA health care utilization along with cost, pharmacy, and laboratory data, through documented VA health encounters and coded diagnostic and procedure data associated with inpatient and outpatient visits. VA fee basis files were utilized to examine Veterans’ receipt of infertility care from non-VA providers.

Subjects

Of the 749,036 Veterans in the OEF/OIF/OND roster as of December 30, 2010, 88,166 (12%) were women. Of these women, 68,442 (78%) were between the ages of 18 and 45 and had used VA medical or mental health services at least once during the study period. For the current analysis, we included only the 1323 women who had at least 1 infertility diagnosis through either a VA or fee basis provider.

Variables

Infertility diagnoses were quantified by grouping diagnoses according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes and specifications18 (Appendix A). Infertility assessments and treatments were quantified by using Current Procedural Terminology codes (Appendix A). Demographic characteristics included in the analysis that may impact infertility diagnoses or treatments included age, race, education, marital status, and service-connected disability status. To understand the contribution of lifestyle factors, such as obesity, on infertility diagnosis or treatment, we used weight and height data from the VA administrative records to calculate body mass index (BMI) [weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2)], to evaluate overall obesity, whereas BMI > 30 kg/m2 is considered obese. To understand the impact of mental health diagnoses on utilization of care for sex-specific conditions, we assessed the presence of mental health conditions using procedures similar to identifying infertility conditions. We focused on mental health conditions (depression, PTSD, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia) that are highly prevalent, and often disabling, conditions among Veterans in the VA (Appendix A). Given the prior literature on MST and infertility, we included a positive screen for MST in our analysis. We also examined alcohol use/dependence and drug use/dependence. This methodology has been used in identification of psychiatric disorders in administrative data.19

To understand how infertility care varies across facilities according to the complexity of clinical services offered at each facility, we utilized the 2008 VA Facility Complexity Model (Veterans Health Administration EDM, 2008) (Appendix B). The Facility Complexity Model variables and weighting are shown in Appendix B. Patient volume includes weighting by clinical encounter and treatment. Clinical services complexity is assessed by evaluating the complexity of intensive care units (ICUs) and complex clinical programs. Education and research capacity are measured by resident slots and Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) research dollars. The model produces 3 complexity levels. Complexity level 1 (high) is characterized by high patient risk, high levels of teaching and/or research, and high patient volume. Complexity level 2 (medium) is characterized by medium patient risk, medium levels of teaching/research activity, medium patient volume, and level 3 and 4 ICU units. Complexity level 3 (low) has the least patient volume, little or no teaching/research, the lowest ratio of physician specialists, and level 1 and 2 ICU units.

Analysis

We used bivariate statistics to describe the characteristics of women Veterans with and without infertility care, and bivariate statistics, including the Student t test for continuous and the χ2 test for ordinal or dichotomous variables, to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of women Veterans with and without infertility assessment and treatment. A separate sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the association between fertility treatment and BMI by race. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC). All statistical tests were 2-tailed with an α-level of 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 68,442 OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans utilized VA care during the study period. Overall, 1323 of these women (1.9%) received an infertility diagnosis during the study period. An additional 119 women received infertility treatment, but no infertility diagnosis, during the study period and were not included in the final sample of 1323 Veterans with infertility diagnosis.

Women Veterans who received an infertility diagnosis were more likely to be younger, black or Hispanic, married, with a high school degree or less, and an enlisted officer in comparison with women Veterans who did not receive an infertility diagnosis (all P-values <0.001) (Table 1). Women Veterans who received an infertility diagnosis were also significantly more likely to have a service-connected disability than those who did not receive an infertility diagnosis.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of OEF/OIF/OND Women Veterans, Ages 18–45, With and Without an Infertility Diagnoses (n = 68,442)

| N (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Women Veterans With Infertility Diagnosis (n = 1323) |

Women Veterans without Infertility Diagnosis (n = 67,119) |

P |

| Age at infertility diagnosis [mean (SD)] |

29.9 (5.3) | — | < 0.001 |

| Age on roster [mean (SD)] | — | 27.6 (7.0) | |

| Race | < 0.001 | ||

| White | 501 (37.9) | 32,379 (48.2) | |

| Black | 450 (34.0) | 16,784 (25.0) | |

| Hispanic | 178 (13.5) | 7155 (10.7) | |

| Other | 99 (7.5) | 5318 (7.9) | |

| Marital status | < 0.001 | ||

| Married | 569 (43.0) | 22,068 (32.9) | |

| Divorced/separated/ annulled/widowed |

86 (6.5) | 5347 (8.0) | |

| Never married | 664 (50.2) | 39,642 (59.1) | |

| Education | < 0.001 | ||

| Less than high school | 8 (0.6) | 820 (1.2) | |

| High school diploma or equivalent |

1037 (78.4) | 49,149 (73.2) | |

| > High school | 257 (19.4) | 16,243 (24.2) | |

| Rank | < 0.001 | ||

| Enlisted | 1276 (96.5) | 61,504 (91.6) | |

| Officer | 47 (3.6) | 5615 (8.4) | |

| Component | < 0.001 | ||

| Guard | 187 (14.1) | 13,984 (20.8) | |

| Active | 948 (71.7) | 40,570 (60.4) | |

| Reserve | 188 (14.2) | 12,565 (18.7) | |

| Branch of service | 0.001 | ||

| Army | 861 (85.1) | 41,564 (61.9) | |

| Coast Guard | 1 (0.1) | 36 (0.1) | |

| Air Force | 188 (14.2) | 11,740 (17.5) | |

| Marines | 37 (2.8) | 2815 (4.2) | |

| Navy | 236 (17.8) | 10,964 (16.3) | |

| Service-connected disability |

< 0.001 | ||

| 0% | 486 (36.7) | 40,334 (60.1) | |

| > 0% | 837 (63.3) | 26,785 (39.9) | |

| Fee basis care for infertility | 211 (16.0) | — | |

| Complexity score of facility where diagnosis/procedure was received | |||

| 1a, 1b, 1c | 1010 (76.3) | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | 190 (14.4) | N/A | N/A |

| 3 | 123 (9.3) | N/A | N/A |

| At least 1 mental health diagnosis |

752 (56.8) | 25,380 (37.8) | < 0.001 |

| PTSD | 461 (34.9) | 14,584 (21.7) | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 629 (47.5) | 20,335 (30.3) | < 0.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 115 (8.7) | 3470 (5.2) | < 0.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 7 (0.5) | 200 (0.3) | 0.130 |

| Alcohol use/dependence | 83 (6.3) | 3609 (5.4) | 0.153 |

| Drug abuse/dependence | 43 (3.3) | 1525 (2.3) | 0.019 |

| Positive military sexual trauma screen |

194 (14.7) | 5422 (8.1) | 0.015 |

Women Veterans who received an infertility diagnosis were also more likely to have a mental health diagnosis than women without an infertility diagnosis, including depression (48% vs. 30%, P < 0.001), PTSD (35% vs. 22%, P < 0.001), and bipolar disorder (9% vs. 5%, P < 0.001) (Table 1). In addition, compared with those without an infertility diagnosis, women Veterans with such a diagnosis were also more likely to have a diagnosis of drug abuse/dependence (3% vs. 2%, P = 0.019), and a history of MST (15% vs. 8%, P = 0.015). Sixteen percent of women Veterans with an infertility diagnosis or treatment (n = 211) received non-VA care for their infertility.

The most common infertility diagnosis was female infertility, NOS/NEC (78% of the sample) (Table 2). A total of 166 women had infertility codes related to anovulation (12% of sample), whereas 82 women in the sample had an infertility diagnosis of tubal origin (6% of sample).

TABLE 2.

Infertility Diagnoses Among OEF/OIF/OND Women Veterans (n = 1323)

| ICD-9 Code | N (%) |

|---|---|

| 6280: Infertility—anovulation | 166 (12.5) |

| 6281: Infertility—pituitary origin | 2 (0.2) |

| 6282: Infertility—tubal origin | 82 (6.2) |

| 6283: Infertility—uterine origin | 2 (0.2) |

| 6284: Infertility—cervical origin | 7 (0.5) |

| 6288 or 6289: Female infertility NEC/NOS | 1036 (78.3) |

| 62891: Habitual aborter without current pregnancy (begin 2006) |

18 (1.4) |

| 8674: Other feminine infertility—closed uterus injury | 3 (0.2) |

| 8784: Other feminine infertility—open wound of vulva | 3 (0.2) |

| 8786: Other feminine infertility—open wound of vagina | 3 (0.2) |

| 9224: Other infertility—contusion of genital organs | 1 (0.1) |

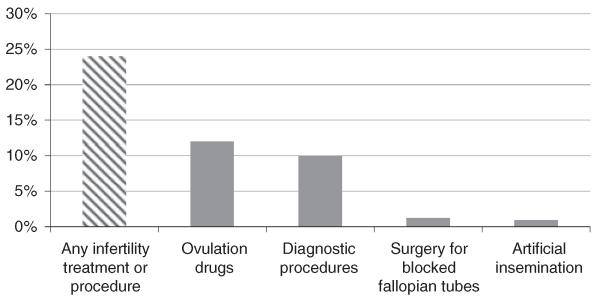

Overall, 22% of women Veterans with an infertility diagnosis received infertility assessment or treatment (Fig. 1). The most common infertility treatment was ovulation drugs (13% of those with an infertility diagnosis), followed by reverse tubal ligation (1% of those with infertility diagnosis) and artificial insemination (1% of those with infertility diagnosis). The most common diagnostic procedure was hysterosalpingography (8.3% of those with infertility diagnosis).

FIGURE 1.

Infertility treatment among OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans, 2001–2010 (n = 290). Any infertility treatment or procedure (n = 290, 21.9%); ovulation drugs (n = 170, 12.8%); diagnostic procedures (n = 110, 8.3%); surgery (n = 18, 1.4%); artificial insemination (n = 13, 1%).

Among women Veterans who received infertility diagnoses, those who also received infertility treatments were slightly younger than women who did not receive infertility treatments (Table 3). The BMI of women Veterans who received infertility assessment or treatment was higher than the BMI of those that did not receive infertility treatment (28.4 vs. 27.7 kg/m2, P = 0.036), and obese women (BMI > 30 kg/m2) were more likely to receive infertility treatment than to not receive treatment (43.4% vs. 31.3%, P = 0.027). There were no differences in utilization of infertility assessments or treatments by race, service-connected disability status, MST history, or mental health diagnoses. Overall, 39% of women Veterans receiving infertility assessment or treatment received this care from non-VA providers.

TABLE 3.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Women VA Users, Ages 18–45 Years, With Infertility by Whether or Not They Received an Infertility Assessment or Treatment

| N (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Received Infertility Assessment or Treatment (n = 290) |

Did Not Receive Infertility Assessment or Treatment (n = 1033) |

P |

| Age at infertility diagnosis [mean (SD)] | 29.4(4.8) | 30.1 (5.4) | 0.052 |

| BMI [mean (SD)] | 28.4 (5.2) | 27.7 (5.3) | 0.036 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 109 (37.6) | 294 (28.5) | 0.004 |

| Race | 0.213 | ||

| White | 104 (35.9) | 397 (38.4) | |

| Black | 99 (34.1) | 351 (34.0) | |

| Hispanic | 50 (17.2) | 128 (12.4) | |

| Other | 21 (7.2) | 78 (7.6) | |

| Marital status | 0.137 | ||

| Married | 116 (40.0) | 453 (43.9) | |

| Divorced/separated/annulled/ widowed |

14 (4.8) | 72 (7.0) | |

| Never married | 159 (54.8) | 505 (48.9) | |

| Education | 0.729 | ||

| Less than high school | 1 (0.3) | 7 (0.7) | |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 224 (77.2) | 813 (78.7) | |

| > High school | 59 (20.3) | 198 (19.2) | |

| Rank | 0.236 | ||

| Enlisted | 283 (97.6) | 993 (96.1) | |

| Officer | 7 (2.4) | 40 (3.9) | |

| Component | 0.177 | ||

| Guard | 50 (17.2) | 137 (13.3) | |

| Active | 204 (70.3) | 744 (72.0) | |

| Reserve | 36 (12.4) | 152 (14.7) | |

| Branch of service | 0.270 | ||

| Army | 179 (61.7) | 682 (66.0) | |

| Coast Guard | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Air Force | 38 (13.1) | 150 (14.5) | |

| Marines | 11 (3.8) | 26 (2.5) | |

| Navy | 62 (21.4) | 174 (16.8) | |

| Service-connected disability | 0.833 | ||

| 0% | 105 (36.2) | 381 (36.9) | |

| > 0% | 185 (63.8) | 652 (63.1) | |

| Fee basis care for infertility | 113 (39.0) | 98 (9.5) | < 0.001 |

| Complexity score of facility where diagnosis/procedure was received |

0.102 | ||

| 1a, 1b, 1c | 235 (81.0) | 775 (75.0) | |

| 2 | 24 (11.7) | 156 (15.1) | |

| 3 | 21 (7.2) | 102 (9.9) | |

| At least 1 mental health diagnosis | 171 (59.0) | 581 (56.2) | 0.408 |

| PTSD | 108 (37.2) | 353 (34.2) | 0.332 |

| Depression | 142 (49.0) | 487 (47.1) | 0.583 |

| Bipolar disorder | 22 (7.6) | 93 (9.0) | 0.449 |

| Schizophrenia | 2 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | 0.670 |

| Alcohol use/dependence | 17 (5.9) | 66 (6.4) | 0.744 |

| Drug abuse/dependence | 11 (3.8) | 32 (3.1) | 0.555 |

| Positive military sexual trauma screen | 41 (14.1) | 153 (14.8) | 0.283 |

| Diagnoses (ICD-9 code) | 0.667 | ||

| 6280: Infertility—anovulation | 43 (14.8) | 123 (11.9) | |

| 6281: Infertility—pituitary origin | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| 6282: Infertility—tubal origin | 20 (6.9) | 62 (6.0) | |

| 6283: Infertility—uterine origin | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| 6284: Infertility—cervical origin | 2 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | |

| 6288 or 6289: Female infertility NEC/NOS |

222 (76.6) | 814 (78.8) | |

There was substantial variation in BMI and infertility treatment by race (Table 4). Black women with an infertility diagnosis had a higher BMI than all other women Veterans with an infertility diagnosis, and obese black women (BMI > 30 kg/m2) were also more likely to receive infertility treatment than to not receive infertility treatment, though this treatment difference did not exist within other racial groups.

TABLE 4.

BMI Stratified by Race for Women VA Users, Ages 18–45 Years, With Infertility by Whether or Not They Received an Infertility Assessment or Treatment

| Characteristics | Received Infertility Treatment (n = 290) |

Did Not Receive Infertility Treatment (n = 1033) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI by race [mean (SD)] | |||

| Black | 29.1 (5.4) | 27.9 (5.1) | 0.040 |

| White | 27.9 (4.9) | 27.3 (5.6) | 0.312 |

| Hispanic | 27.3 (4.6) | 27.4 (4.6) | 0.866 |

| Other | 28.0 (5.5) | 27.9 (5.2) | 0.953 |

| Obesity by race (BMI ≥ 30) [n (%)] | |||

| Black | 43 (43.4) | 110 (31.3) | 0.027 |

| White | 37 (35.6) | 108 (27.2) | 0.113 |

| Hispanic | 14 (28.0) | 27 (21.1) | 0.339 |

| Other | 6 (28.6) | 21 (26.9) | 0.933 |

BMI indicates body mass index.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine infertility care among women Veterans using VA health care. A relatively small proportion (< 2%) of OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans received infertility diagnoses during the study period, and among those women, 22% received infertility assessments and treatments. Rates of assessment and treatment for infertility were higher among women Veterans using non-VA care. Understanding women’s use of VA infertility services is an important component of understanding VA’s commitment to comprehensive medical care for women Veterans.

In our analyses, we found that non-white women Veterans were overrepresented among those with an infertility diagnosis, and that a substantial proportion of those black women receiving infertility assessment or treatment had a BMI > 30 kg/m2. A population-based study also found that blacks had a 2-fold increased odds (95% confidence interval, 1.3–3.1) of infertility compared with whites after adjustment for socioeconomic position (education and income), correlates of pregnancy intent (marital status and hormonal contraceptive use), and risk factors for infertility (age, smoking, fibroid presence, and ovarian volume).20 Other studies have found that high BMI was related to delayed conception in black women.21

The proportion of women Veterans diagnosed with infertility or receiving infertility treatments was substantially lower than rates of fertility reported by the CDC.22 In a national survey conducted from 2006–2010, 6% of married women aged 15–44 reported infertility. In 1 recent study characterizing self-reported lifetime infertility among OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans, 15.8% reported infertility.13 However, given that previous studies focused on self-reported infertility and the present work focused only on clinical diagnoses and receipt of VA-paid infertility care, it is impossible to make direct comparisons.

Infertility treatments fall into 3 categories: (1) medication, (2) surgical, and (3) assisted reproductive technologies.23 In our study, the most common infertility treatment was infertility medications, with nearly 13% of women Veterans with diagnosed infertility taking oral or injectable infertility medications. In contrast, only 1% of women had surgical infertility treatments, and <1% received artificial insemination through intrauterine insemination. Because the VA does not pay for in vitro fertilization, no women in our study received IVF treatments.

Overall, few women Veterans with infertility diagnoses received VA infertility treatment during the study period, with only 13 Veterans receiving artificial insemination between 2001 and 2010. This low rate of artificial insemination may be attributable to VA policy that extends infertility benefits only to the Veteran and not to her partner. For women to receive artificial insemination services, their partner’s sperm must be analyzed, processed, and prepared for insemination. However, if the partner is not a Veteran, these services are not covered by VA benefits.

One important finding in this study is strong association between infertility and mental health diagnoses. This echoes findings from previous studies that have shown higher rates of infertility among those women with depression or PTSD.12 Although many women may experience depression after repeated, unsuccessful attempts to become pregnant, the association between infertility and depression may be related to women who seek VA care. Previous studies have demonstrated that women with service-connected disabilities, including depression and PTSD, are more likely to receive VA care,1,2,7,12,14 and because these women are already in VA care, they may be more likely to speak with their VA health care providers about problems related to conception. Women with mental health conditions and service-connected disabilities may also be more dependent on VA care due to lack of resources and thus less likely to seek reproductive care outside the VA health care system.

Findings from this study have several important policy implications to ensure delivery of comprehensive care in the VA. Evaluating the care that these women need, and tailoring VA women’s health programs to meet the needs of these women is crucial. Some women Veterans may not want treatment for infertility, or the diagnosis may have been incorrectly entered, or may represent a carry-forward diagnosis in which the provider is recording that she had infertility treatment in the past or they may have become pregnant without any medical intervention. Future studies should examine the extent to which women Veterans use private health insurance to seek infertility care, especially for services not covered by the VA such as in vitro fertilization.

There are several important limitations to our study. First, study conditions were ascertained by ICD-9 codes, and, as others have noted, it is possible that conditions were underascertained.24 Second, women may have received infertility care from non-VA providers through other insurance arrangements, including private insurance or TRICARE. The VA administrative databases do not capture this care, and therefore we are unable to ascertain whether women received care from other providers if that provider did not submit a VA claim. Third, we used the VA complexity measure as a predictor of infertility care. However, the complexity measure is used primarily to understand care delivered at VA medical centers, and not care delivered from community-based outpatient clinics. Consequently, the availability of infertility care may have been overestimated among women who primarily receive care at community-based outpatient clinics. Finally, we studied OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans in VA care, and findings may not be generalizable to OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans who do not use the VA, women Veterans of other eras, or non-Veteran women.

Nevertheless, this study makes several important contributions to the literature on women Veterans and infertility. It is the first study to examine infertility care among OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans. Overall, we found a small proportion of women Veterans with infertility diagnoses, and an even smaller proportion of women utilizing VA care for infertility treatment. Women with non-VA care diagnoses of infertility were more likely to receive an infertility assessment or treatment. Future studies should examine women’s experience with VA infertility care and determine how many ultimately utilize VA maternity benefits. The VA should also examine how women make decisions regarding infertility care if the services they require are not covered by VA insurance mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Christine Ulbricht, Ginnie Ryan, and Barrett Phillips for their contributions to the paper.

Supported by Veteran Affairs Health Services Research and Development.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

List of All ICD-9 and CPT Codes Used for Analysis

| ICD-9 Codes | CPT Codes |

|---|---|

| Infertility diagnoses | Infertility assessments or treatments |

| Infertility—anovulation: 6280 | Evaluation cervical mucus: 89330 |

| Infertility—pituitary origin: 6281 | Unlisted reprod med lab proc: 89398 |

| Infertility—tubal origin: 6282 | Artificial insemination: 58321 |

| Infertility—uterine origin: 6283 | Ovulation management per cycle: S4042 |

| Infertility—cervical origin: 6284 | Reverse tubal ligation: 58750 |

| Female infertility NEC: 6288 | Chromotubation of oviduct, including materials: 58350 |

| Female infertility NOS: 6289 | Create new tubal opening: 58770 |

| Tubal cannulation: 58345 | |

| Mental health disorders | |

| Depression: 293.83 296.20, .21, .22, .23, .24, .25, .30, .31, .32, .33, .34, .35, 300.4, 311 |

Hysterosalpingography, radiological supervision, and interpretation: 74740, together with catheterization and introduction of saline or contrast material for saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS) or hysterosalpingography: 58340 |

| PTSD: 309.81 | |

| Anxiety: 300.00 | |

| Schizophrenia: 295.0, .00, .01, .02, .03, .04, .05, .1, .10, .11, .12, .13, .14, .15, .2, .20, .21, .22, .23, .24, .25, .3, .30, .31, .32, .33, .34, .35, .4, .40, .41, .42, .43, .44, .45, .5, .50, .51, .52, .53, .54, .55, .6, .60, .61, .62, .63, .64, .65, .8, .80, .81, .82, .83, .84, .85, .9, .90, .91, .92, .93, .94, .95 |

Saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS), including color flow Doppler, when performed, together with any other previously listed CPT in this table; oral infertility medications (eg, Clomid); injectable infertility medications: 76831 |

| V11.0 | |

| Substance abuse disorders | |

| Alcohol abuse and dependence: 303.00, .01, .02, .03, .90, .91, .92, .93 305.00, .01, .02, .03 |

|

| Drug abuse or dependence: 304.00, .01, .02, .10, .11, .12, .13, .20, .21, .22, .23, .30, .31, .32, .33, .40, .41, .42, .43, .50, .51, .52, .53, .60, .61, .62, .63, .70, .71, .72, .73, .80, .81, .82, .83, .90, .91, .92, .93 |

|

| 305.20, .21, .22, .23, .30, .31, .32, .33, .40, .41, .42, .43, .50, .51, .52, .53, .60, .61, .62, .63, .70, .71, .72, .73, .80, .81, .83, .90, .91, .92, .93 |

TABLE A2.

FY2008 Facility Complexity Model Variables

| Complexity Model Category |

Variable Name | Variable Description | Weight | Total Category Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient population |

Veterans equitable resource allocation (VERA) prorated person (PRP) |

This variable represents the total number of PRPs seen at each VHA facility, based on the VERA model. In this model, each patient in the VHA system is classified into a patient class that represents the level of treatment provided in the preceding year. The class is based on clinical encounters and treatments. Each individual patient equates to 1 PRP, which is proportionately distributed among VHA facilities where treatment occurred, based on costs incurred |

0.25 | 0.40 |

| Patient risk | This is a Medicare Relative Risk score calculated from all VHA patient diagnoses from all sources, benchmarked to an average expected Medicare costliness of 1.00 for those diagnoses |

0.15 | ||

| Clinical services complexity |

Level of intensive care unit | This variable reflects the categorization of intensive care units. Intensive care units within VHA facilities are categorized into levels based on specified criteria that tend to contribute to the complexity of intensive care units, such as type of services provided and availability of subspecialty services |

0.20 | 0.45 |

| Complex clinical programs | This variable represents the number of complex clinical programs at the facility. There are a total of 11 complex clinical programs |

0.25 | ||

| Education and research |

Total resident slots | This variable represents the number of resident programs within the facility. Total resident slots is stated as the number of slots allotted to each residency program within the facility |

0.05 | 0.15 |

| Herfindahl index (HHI) resident slots |

The HHI represents the proportion of residency slots in each residency program, squared, and then summed across all residency programs within the facility. Therefore, a facility with numerous residency programs will have a very low value |

0.05 | ||

| VERA research | This variable represents the total amount of research dollars managed by a VHA facility, divided by the total number of prorated persons in 2006, as calculated according to the VERA model |

0.05 |

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frayne S, Phibbs C, Friedman S, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration Volume 2 Sociodemographics and Use of VHA and Non-VA Care (Fee) Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, Women’s Health Services, Veterans Health Administration. Department of Veterans Affairs; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattocks KM, Skanderson M, Goulet JL, et al. Pregnancy and mental health among women veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. J Womens Health. 2010;19:2159–2166. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Homan GF, Davies M, Norman R. The impact of lifestyle factors on reproductive performance in the general population and those undergoing infertility treatment: a review. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:209–223. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petraglia F, Serour GI, Chapron C. The changing prevalence of infertility. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;123(suppl 2):S4–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattocks KM, Frayne S, Phibbs CS, et al. Five-year trends in women veterans’ use of VA maternity benefits, 2008-2012. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24:e37–e42. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle P, Maconochie N, Ryan M. Reproductive health of Gulf War veterans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:571–584. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang H, Magee C, Mahan C, et al. Pregnancy outcomes among US Gulf War veterans: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:504–511. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araneta G, Rosario M, Schlangen KM, et al. Prevalence of birth defects among infants of Gulf War veterans in Arkansas, Arizona, California, Georgia, Hawaii, and Iowa, 1989–1993. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67:246–260. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray GC, Coate BD, Anderson CM, et al. The postwar hospitalization experience of US veterans of the Persian Gulf War. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1505–1513. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611143352007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen BE, Maguen S, Bertenthal D, et al. Reproductive and other health outcomes in Iraq and Afghanistan women veterans using VA health care: association with mental health diagnoses. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22:e461–e471. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frayne SM, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM, et al. Medical profile of women Veterans Administration outpatients who report a history of sexual assault occurring while in the military. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8:835–845. doi: 10.1089/152460999319156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan GL, Mengeling MA, Booth BM, et al. Voluntary and involuntary childlessness in female veterans: associations with sexual assault. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:539–547. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katon J, Cypel Y, Raza M, et al. Self-Reported infertility among male and female veterans serving during Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom. J Womens Health. 2014;23:175–183. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bean-Mayberry BA, Yano EM, Caffrey CD, et al. Organizational characteristics associated with the availability of womens health clinics for primary care in the Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2007;172:824–828. doi: 10.7205/milmed.172.8.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Washington DL, Caffrey C, Goldzweig C, et al. Availability of comprehensive women’s health care through Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Womens Health Issues. 2003;13:50–54. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seelig MD, Yano EM, Bean-Mayberry B, et al. Availability of gynecologic services in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veterans Health Administration . Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), VHA Handbook 133001: Health care services for women. Veterans Health Administration; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Disease Control and Prevention . ICD-9-CM Official Guides for Coding and Reporting. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goulet JL, Fultz SL, Rimland D, et al. Aging and infectious diseases: do patterns of comorbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1593–1601. doi: 10.1086/523577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wellons MF, Lewis CE, Schwartz SM, et al. Racial differences in self-reported infertility and risk factors for infertility in a cohort of black and white women: the CARDIA Women’s Study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1640–1648. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Body size and time-to-pregnancy in black women. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2856–2864. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility and impaired fecundity in the United States, 1982-2010: data from the National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Report. 2013;67:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Congress of Obstetricians and GynecologistsTreating infertility [Accessed April 4, 2014];FAQ 137. 2013 Available at: http://www.acog.org/B/media/For%20Patients/faq137.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20140501T0930143570.

- 24.Frayne SM, Chiu VY, Iqbal S, et al. Medical care needs of returning veterans with PTSD: their other burden. J Gen Int Med. 2011;26:33–39. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1497-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]