Abstract

Purpose

Given that emotional health is a critical component of healthy aging, we undertook a systematic literature review to assess whether current interventions can positively affect older adults’ emotional health.

Methods

A national panel of health services and mental health researchers guided the review. Eligibility criteria included community-dwelling older adult (aged ≥ 50 years) samples, reproducible interventions, and emotional health outcomes, which included multiple domains and both positive (well-being) and illness-related (anxiety) dimensions. This review focused on three types of interventions – physical activity, social support, and skills training – given their public health significance and large number of studies identified. Panel members evaluated the strength of evidence (quality and effectiveness).

Results

In all, 292 articles met inclusion criteria. These included 83 exercise/physical activity, 25 social support, and 40 skills training interventions. For evidence rating, these 148 interventions were categorized into 64 pairings by intervention type and emotional health outcome, e.g., strength training targeting loneliness or social support to address mood. 83% of these pairings were rated at least fair quality. Expert panelists found sufficient evidence of effectiveness only for skills training interventions with health outcomes of decreasing anxiety and improving quality of life and self-efficacy. Due to limitations in reviewed studies, many intervention–outcome pairings yielded insufficient evidence.

Conclusion

Skills training interventions improved several aspects of emotional health in community-dwelling older adults, while the effects for other outcomes and interventions lacked clear evidence. We discuss the implications and challenges in moving forward in this important area.

Keywords: mental health, aged, health promotion, review

Introduction

Emotional health is increasingly viewed as a multidimensional construct that includes both positive and illness-related dimensions. Hendrie et al. (1) characterized emotional health as self-efficacy, depression, hostility and anger, anxiety, psychological stress, optimism, self-esteem, quality of life, and other domains assessed by multidimensional measures. A report (2) using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) (3) identified six indicators reflecting positive and illness-related emotional health outcomes in older adults: social and emotional support; life satisfaction; frequent mental distress; current depression; lifetime diagnosis of depression; and lifetime diagnosis of anxiety disorders.

Mental health is increasingly viewed as part of public health’s mission, as important as physical health in contributing to overall health and well being (2). Epidemiologic data links a range of health outcomes, particularly mortality and cardiovascular disease, to emotions (1). Despite the public health importance, little is currently known about the effectiveness of interventions to promote emotional health in community-dwelling older adults. One of the few available reports (4) reviews studies from UK, finding some evidence to support significant small-to-moderate improvements in emotional health from select exercise programs including mixed exercise programs, strength and resistance, aerobic, walking, and individually targeted health promotion interventions. However, it also indicated a clear shortage of robust evidence for effective programs to improve late-life emotional health.

Although this review (4) addressed several important questions, a more rigorous review of the scientific literature is warranted. The primary objective of this systematic literature review was to identify interventions to promote emotional health of older adults aged 50 years and older. We sought to expand Windle and colleagues work by encompassing a wider range of community-based interventions, including more than UK-based studies, examining multiple domains of emotional health incorporating both positive and illness-related dimensions, and addressing community-dwelling older adults.

Materials and Methods

Data sources

Conceptual framework and definition of emotional health

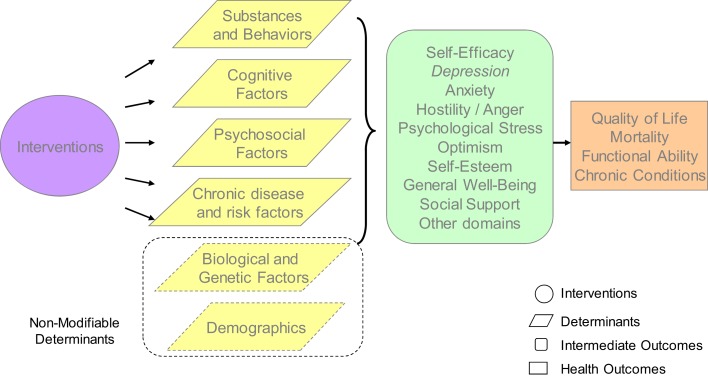

This review used the NIH’s Cognitive and Emotional Health Project (1, 5) to guide the development of our conceptual framework and definition of emotional health (Figure 1). Interventions to promote emotional health can influence various determinants of emotional health. These determinants include substance use and other behaviors, cognitive factors, psychosocial factors, emotional factors, and chronic conditions. Risk and protective factors for emotional health also included less modifiable biological and genetic factors and demographics. For the purpose of this review, we focused on interventions aimed at modifiable determinants.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Borrowing from Hendrie and colleagues, we defined emotional health comprehensively as including both emotion regulation concepts (e.g., the ability to control/regulate emotions) and emotion intelligence (e.g., the ability to recognize and use emotions constructively). Most importantly, emotional health is multidimensional, involving positive mental health constructs, such as life satisfaction as well as illness-related domains such as anxiety. We used Hendrie and colleagues’ emotional health domains (1) and added “general well being” and “social support,” given research describing the relevance of these constructs to emotional health (6–8). The emotional health constructs used in this review are provided in the first row of Table 1. Finally, based on the literature, the conceptual model included longer term health outcomes associated with emotional health, including reductions in mortality and improvements in functional ability, morbidity of chronic conditions, and overall quality of life (entailing both physical and emotional well being).

Table 1.

Search terms used in electronic searches.

| Construct | Search terms | |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional health | Emotional health | Interpersonal trust |

| Self-efficacy | Positive Energy | |

| Locus of control | Happiness | |

| Personal control | Contentment | |

| Personal mastery | Hardiness | |

| Powerlessness | Resilience | |

| Sense of coherence | Emotional vitality | |

| Depression | Shame | |

| Hopelessness | Guilt | |

| Hostility | Regret | |

| Anger | Emotion regulation | |

| Type A behavior | Emotional control | |

| Anxiety | Well being | |

| Environmental demands | Altruism | |

| Life events | Sadness | |

| Stress | Fear | |

| Mood states | Neuroticism | |

| Positive affect | Boredom | |

| Negative affect | Capacity to care | |

| Optimism | Life satisfaction | |

| Self-esteem | Spirituality | |

| Quality of life | Caregiver burden | |

| Loneliness | Acculturation | |

| Social support | Discrimination | |

| Intervention | Intervention | Reminiscence therapy |

| Treatment | Assertiveness training | |

| Prevention | Strengths-based | |

| Exercise | Positive psychology | |

| Physical activity | Social support | |

| CBT | Spirituality | |

| Psychotherapy | Complementary and alternative medicine | |

| Life review | Integrated medicine stress management | |

| Meditation | Anger management | |

| Mindfulness | Coping skills | |

| Community based | Community | Primary care |

| Home | Community health center | |

| Neighborhood | ||

| Older adults | Older adults | Middle-Aged |

| Aged | Limits of 40 and older (to include 50 and older) | |

| Elderly | ||

| Study design | Clinical trial | Experimental replication |

| Multicenter study | Follow-up study | |

| Randomized controlled trial | Field study | |

| Randomized clinical trial | Non-clinical case study | |

| Evaluation studies | Qualitative study | |

| Clinical case study | Quantitative study | |

| Empirical study |

Note: We did not find any physical activity, social support, or skills training intervention studies that targeted the emotional health outcomes in italics.

Expert panel and review methods

This review was guided by an eight-member expert panel of health services and mental health researchers from around the United States representing psychology, psychiatry, geriatrics, public health, and social work. The systematic review methods were derived from the Guide to Community Preventive Services (“The Guide”) (9, 10) and the systematic literature review of strategies to address late-life depression (11), using a formal process to identify relevant studies, assess their quality, and summarize the evidence. We searched the peer-reviewed literature through June 2008 and updated the search in June 2012 using PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), CINAHL (http://www.ebscohost.com/academic/cinahl-plus-with-full-text/), and PsycINFO (www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/index.aspx) databases. Subject headings and text words reflected our study aims, including key concepts of “emotional health,” “older adults,” “community based,” and “intervention”; specific terms are provided in Table 1. References to meta-analyses and review papers were also examined, and expert panelists reviewed the citations of included articles.

Study selection

Study inclusion criteria were (1) published data on populations aged 50 years and older, (2) community-based sample and setting, (3) clearly described intervention; and (4) “emotional health” operationalized using the list of constructs determined by the expert panel (see Table 1). There were no restrictions on sample size or study design. Articles were excluded if they: were not available in English; reported only a review of the literature, meta-analysis, or commentary; focused exclusively on inpatient or institutionalized persons. We included articles from any country as long as they were published in English. We excluded interventions that targeted depression given the overlap with a previously conducted review focusing on late-life depression (11). The emotional component of quality of life measures was included [e.g., the role emotional subscale of the SF-36 (12)]; however, physical subscales were excluded. For studies aimed at addressing outcomes not strictly emotional in nature (e.g., spirituality, caregiver burden), we required the inclusion of at least one other emotional health outcome from the list of constructs.

We used a two-step screening process evaluating abstracts and where necessary full text to assess whether articles met inclusion criteria. A standardized form was used to systematically collect key data from each article, including study design, sample size, intervention setting, outcome measures, results, and indicators of study quality. Data were compiled in summary tables that the expert panel used for the evidence rating. As employed in our prior review (11), we grouped articles into intervention type-emotional health outcome pairings to categorically rate the evidence. For example, skills training interventions aimed at reducing anxiety were paired together.

Expert panel members rated the quality and effectiveness of each intervention–outcome pairing (Table 2). For quality rating, panel members independently rated the set of studies for each intervention–outcome pairing as Good, Fair, or Limited. Because few pairings received a vote of “good,” the good and fair categories were collapsed into a single category labeled “at least fair” quality. For effectiveness ratings, the panel members independently rated each intervention–outcome pairing as Strong, Sufficient, or Insufficient. For any pairing rated as insufficient, panel members were asked to record whether the rating was due to (1) an insufficient number of available studies or (2) a sufficient number of available studies but an insufficient amount of data to determine effectiveness. As established at the start of the review process, final determination of quality and effectiveness was based on 80% agreement among panel members. The panel met to discuss areas of disagreement and panel members were allowed to change their votes after the discussion; however, they were not required to reach consensus.

Table 2.

Indicators of quality and effectiveness for rating the evidence.

| Quality indicators | Effectiveness indicators |

|---|---|

| Well-described study population and intervention | Study quality |

| Sampling | Study design |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Number of studies |

| Data analysis | Consistency across studies |

| Interpretation of results | Statistical results |

Results

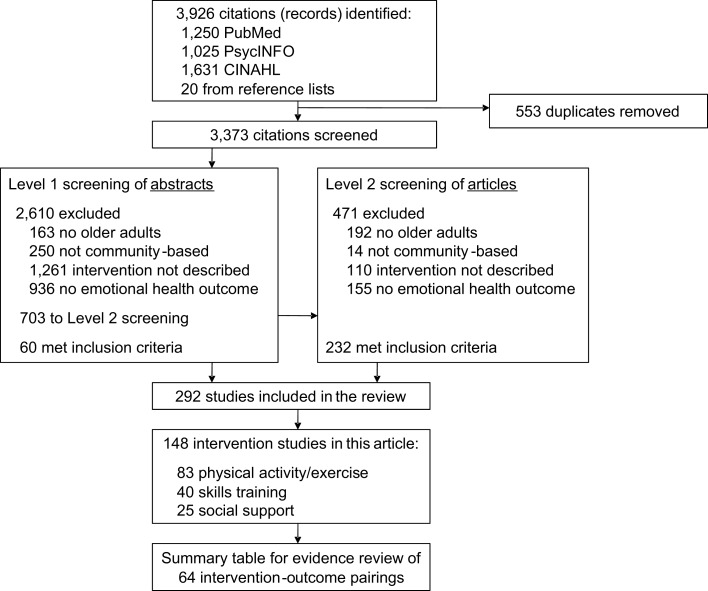

A total of 3,926 articles were identified in the initial search (1,250 from PubMed, 1,025 from PsycINFO, 1,631 from CINAHL, and 20 from reference lists of review articles or meta-analyses). 553 articles were duplicates and were eliminated (Figure 2). Two hundred ninety-two articles were eligible for inclusion, with the majority of the ineligible being excluded due to having too young of a sample size, not being an intervention study, or not having an emotional health outcome. Of the 292 eligible articles, the expert panel focused on three types of interventions relevant to public health practice and with ample studies for rating the evidence. These comprised a total of 148 of the 292 found articles: physical activity and/or exercise (n = 83), skills training (n = 40), and social support (n = 25) (Table 3). More than half of the studies (57%) were from the US or Canada, 19% were from European studies, 12% were from Australia or New Zealand, and 11% were from Asia. Thirty-nine percent of the articles specified that a theoretical framework that was used to inform the development of the intervention – one-third of the studies that evaluate an exercise or a social support intervention used a theoretical framework, while two-thirds of skills training interventions used a theoretical framework. Across interventions, the most common frameworks used across interventions were social cognitive theory, self-efficacy, and social learning theory. Other theories include the progressively lowered stress threshold model, the self-care deficit nursing theory of Orem, mindfulness meditation, self-management model of illness behavior, stress and coping theoretical framework, stress process models of caregiving, the transtheoretical model of behavior change, stages of change, negotiated adherence model, motivational interviewing, transforming hope theory, and Yalom group theory.

Figure 2.

Literature review flow chart.

Table 3.

Intervention–outcome pairings for skills training, social support + skills training, and physical activity interventions.

| Intervention | Emotional health outcome | # Of studies (n)a | Quality rating | Effectiveness rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skills training | Anger | 3 (258) (13–15) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Skills training | Anxiety | 11 (1,346) (13, 16–25) | At least fair | Sufficient |

| Skills training | Mood | 5 (988) (13, 18, 26, 27, 76) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Skills training | Other positive outcomes | 2 (99) (29, 145) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Skills training | Psychological well being/distress | 4 (1,449) (31, 32, 124, 142) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Skills training | Quality of life | 11 (1,417) (17, 22, 29, 31, 35–41) | At least fair | Sufficient |

| Skills training | Self-efficacy | 16b (3,735) (14, 15, 18, 20, 24, 26, 27, 30, 35, 39, 41–46, 175) | At least fair | Sufficient |

| Skills training | Spirituality | 3b (283) (23, 27, 65, 148) | Limited | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Skills training | Stress | 4b (500) (39, 45, 46, 98, 142) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Social support | Anxiety | 3b (502) (34, 93, 135, 138) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Social support | Loneliness | 2 (313) (72, 108) | Limited | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Social support | Mood | 2b (144) (72, 109, 113) | Limited | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Social support | Other positive outcomes | 1 (39) (83) | Limited | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Social support | Psychological well being/distress | 5b (704) (31, 34, 89, 128, 135, 139) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Social support | Quality of life | 3b (450) (31, 34, 135, 138) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Social support | Self-efficacy/locus of control | 1 (39) (83) | Limited | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Social support + skills training | Anxiety | 5 (580) (54, 63, 70, 100, 143) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Social support + skills training | Mood | 1 (144) (70) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Social support + skills training | Other negative outcomes | 2 (415) (47, 82) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Social support + skills training | Other positive outcomes | 3c (58) (33, 66) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Social support + skills training | Psychological well being/distress | 6 (1,041) (14, 47, 70, 82, 144, 174) | Limited | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Social support + skills training | Quality of life | 3b,c (393) (66, 109, 113, 121) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Social support + skills training | Self-efficacy/locus of control | 3 (408) (65, 70, 121) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Motivation/counseling | Mood | 1 (86) (103) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Motivation/counseling | Other positive outcomes | 2 (969) (71, 79) | At least fair | Insufficient (No consensus) |

| Motivation/counseling | Quality of life | 4 (850) (52, 64, 71, 120) | At least fair | Insufficient (Multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Motivation/counseling | Self-efficacy/mastery | 5 (567) (71, 79, 92, 112, 176) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Motivation/counseling | Stress | 2 (1,712) (79, 118) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Aerobic: walking | Anxiety | 3 (507) (59, 102, 146) | At least fair | No Consensus (btw sufficient and insufficient, multiple studies) |

| Aerobic: other aerobic activities | Anxiety | 4 (361) (57, 73, 114, 136) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Aerobic: walking | Caregiver burden | 1b (100) (60, 102) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Aerobic: walking | Mood | 2 (170) (107, 147) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Aerobic: walking | Other positive outcomes | 1 (582) (101) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Aerobic: other aerobic activities | Other positive outcomes | 2 (150) (57, 114) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Aerobic: walking | Quality of life | 6 (1,273) (56, 101, 104, 123, 130, 147) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Aerobic: other aerobic activities | Quality of life | 6 (823) (51, 57, 117, 134, 151, 179) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Aerobic: walking | Psychological distress and well-being | 91 (28) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Aerobic: other aerobic activities | Psychological distress and well being | 101 (136) | At last fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Aerobic: walking | Self-efficacy/mastery/locus of control | 1 (32) (62) | NC | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Aerobic: Other aerobic activities | Self-efficacy/mastery/locus of control | 3 (231) (56, 106, 114) | NC | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Aerobic: walking | Stress | 2b (457) (59, 60, 102) | At least fair | No consensus (btw sufficient and insufficient, not enough studies) |

| Strength/resistance | Anxiety | 1 (42) (129) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Strength/resistance | Fear of falling | 2 (94) (48, 150) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Strength/resistance | Loneliness | 1b (32) (84, 129) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Strength/resistance | Mood | 2 (144) (69, 153) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Strength/resistance | Psychological well being/distress | 2 (124) (134, 153) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Strength/resistance | Quality of life | 13b (1,000) (28, 68, 75, 84, 115, 119, 122, 126, 132–134, 137, 153, 177) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Strength/resistance | Self-efficacy/locus of control | 7b (442) (75, 115, 126, 129, 132, 137, 153, 177) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Stretch/flexibility/balance/agility | Anxiety | 1 (88) (96) | NC | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Stretch/flexibility/balance/agility | Fear of falling | 2b (422) (53, 90, 181) | At least fair | No consensus (btw sufficient and insufficient) |

| Stretch/flexibility/balance/agility | Mood | 5 (307) (49, 87, 95, 116, 147) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Stretch/flexibility/balance/agility | Other positive outcomes | 1b (200) (53, 182) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Stretch/flexibility/balance/agility | Psychological well being/distress | 1b (200) (53, 182) | At least fair | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Stretch/flexibility/balance/agility | Quality of life | 8b (853) (48, 51, 53, 87, 94, 96, 132, 147, 181) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Stretch/flexibility/balance/agility | Self-efficacy/mastery/locus of control | 5 (465) (48, 90, 94, 95, 132) | At least fair | No consensus (btw strong, sufficient, insufficient) |

| Stretch/flexibility/balance/agility | Stress | 1 (39) (95) | NC | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

| Combination | Anxiety | 3 (485) (91, 180, 182) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Combination | Fear of falling | 2 (200) (85, 88) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Combination | Mood | 3 (257) (81, 97, 173) | At least fair | Insufficient (no consensus) |

| Combination | Other positive outcomes | 3 (459) (91, 131, 178) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Combination | Psychological well being/distress | 6 (748) (97, 131, 133, 180, 182, 184) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Combination | Quality of life | 16 (7,492) (55, 61, 78, 80, 81, 85, 86, 88, 97, 99, 110, 111, 149, 152, 182, 183) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Combination | Self-efficacy/mastery/locus of control | 5b (654) (77, 92, 105, 125, 127, 183) | At least fair | Insufficient (multiple studies, inconclusive data) |

| Combination | Stress | 1 (187) (180) | NC | Insufficient (not enough studies) |

NC, no consensus.

aArticle citations for each intervention–outcome pairing are provided in this column. Some of the 148 studies are listed in more than one intervention–outcome pairing.

bSeveral studies are reported in more than one article (e.g., article #40 and article #41 describe the same study using different analyses).

cArticle #62 reported on two different positive outcomes, self-esteem and life satisfaction.

The physical activity and/or exercise interventions included aerobic activity, strength training, balance and flexibility interventions, motivational strategies, and a combination of exercise types. The skills training group included self-management [e.g., Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP)], psycho-education, anger management, and stress management interventions. The social support group included interventions targeting direct or indirect provision of social support (e.g., interventions designed to improve ability to obtain support).

The 148 studies were subsequently grouped into 64 intervention type–outcome pairings, or categories, for rating the evidence, such as social support interventions aimed at elevating mood (Table 3). For quality, 53 (83%) of the intervention–outcome pairings were rated as having “at least fair” quality; only 11% of these had good quality. For effectiveness, a majority of pairings (89%) were deemed to have insufficient evidence, due to lack of studies (two or fewer) or inconclusive evidence (mixed results within or across studies). Herein, we will report findings for the three intervention–outcome pairings for which sufficient evidence was found. For further information about categories not presented or on detailed summary data tables, please contact the corresponding author.

Intervention–outcome pairings with sufficient evidence

Skills training

Sufficient evidence was found for effectiveness of skills training interventions to reduce anxiety and to promote quality of life and self-efficacy (from a total of 38 studies). These studies were rated as having “at least fair” quality. Of these studies, 11 were aimed at reducing anxiety, of which four involved randomized controlled trials (RCT). They involved 1,346 participants and represented a diverse subject population (e.g., caregivers and people with breast cancer, heart disease, or arthritis). Only three studies reported dropout rates, and in two of these, that rate was below 20%. Study duration varied from 2 to 12 months, although generally the active phase ranged from 6 to 8 weeks.

The report by López et al. (16) focused on caregivers in which the majority of care was provided to persons living with dementia (80%).They found a 38% decrease in mean anxiety score in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (154) for traditional format skills training (60 min weekly over a period of 8 weeks) involving cognitive behavioral approaches, assertiveness training, self-esteem building exercises, and problem-solving skills training. The other studies using the HADS found a 10–20% decrease in anxiety scores after intervention (17, 18). The Williams (19) study of 71 women with breast cancer found no effect for a 20-min audiotape to teach skills for decreasing sleep, anxiety, and fatigue problems encountered during chemotherapy. Two non-randomized, controlled trials did not show a significant effect. One focused on asthma self-management and another focused on Chinese older adults with history of depression or anxiety, although there was a non-significant trend toward effectiveness (p < 0.10) (20, 21). Five single-group studies revealed mixed results (13, 22–25).

Eleven additional skills training studies aimed at emotional health as measured by the subscales of a quality of life measure such as the SF-36. There were eight RCTs, two quasi-experimental studies, and one single-group study. A total of 1,417 participants were included in these studies, with sample sizes ranging from 35 to 320, averaging between 75 and 100 participants. The duration of the interventions ranged from 1 week to 8 months, averaging between 6 and 8 weeks. Interventions included both group and individual-level activities. Dropout rates of less than 20% were reported for all but two studies. Seven studies [five RCTs (17, 35–39) and one non-RCT (40)] reported statistically significant improvements in at least one emotional health subscale of the SF-36 Quality of Life measure. Specifically, statistically significant improvements were reported for the vitality and role limitations emotional SF-36 subscales for Barnason et al.’s (35) phone-based home communication intervention for older adults with ischemic heart failure (p < 0.01). Similarly, Grant et al.’s (36) social problem-solving phone partnership for adult caregivers of stroke survivors improved quality of life subdomains (p = 0.013). McHugh et al.’s (17) share care health education and motivational interviewing program for adults waiting for elective CABG (p = 0.000), and Wallace et al.’s (37) nurse visit to develop a customized health plan for older adults exercising at a local senior center were found to be effective (p = 0.02). No significant improvements in vitality were found for Markle-Reid et al.’s (26, 38) individual-level program to bolster personal and environmental resources of frail, older home care clients although this study did find improvement using the role limitation emotional subscale. In addition to Grant et al. (36), Markle-Reid et al. (38), McHugh et al. (17), and Wallace et al. (37) studies, Hughes et al. (39) study of a workshop intervention for women with self-reported disabilities all reported significant improvements in the SF-36 mental health subscale. Furthermore, two studies (38, 40) found significant improvements in the mental health composite SF-36 measure (including vitality, mental health, and role limitation emotional). Significant improvements were demonstrated in two studies using emotional health subscales of quality of life-specific measures for older adults with heart failure (13, 22–25, 31, 35–38). The remaining two studies (29, 41) did not find improvements in emotional health subscales of different quality of life measures.

Sixteen skills training intervention studies were directed at improving self-efficacy. These studies included 11 RCTs, two observational studies, and three single-group studies. Seven of the studies were of interventions using the CDSMP. A total of 3,735 participants received skills training interventions, with sample sizes ranging from 33 to 728. Study duration averaged 6 to 8 weeks. Dropout rates, reported in half the studies, were less than 20%. The frequency of the skills training interventions was rarely reported. When reported, adherence to the intervention was typically less than 80%. The interventions were delivered most often in a group format and the control groups were generally usual care and wait-list control conditions. Eight of the 11 RCTs (14, 15, 26, 27, 35, 42–46) reported significant improvements in self-efficacy; three of the significant studies used CDSMP (15, 42, 45). Four of the five non-RCT studies (15, 20, 24, 32) also demonstrated significant improvements in self-efficacy. All but Smith et al. (20) study were single-group designs with 20–32% dropout rates.

Exercise and social support

The expert panel did not find sufficient evidence for either exercise or social support interventions to improve emotional health.

Other intervention–outcome pairings

Skills training

The expert panel found insufficient evidence for 20 other skills training interventions that focused on other emotional health outcomes such as mood and stress. Most of these pairings were of at least fair quality. In addition, 82 studies were found that reported on the effects of physical activity and/or exercise on emotional health outcomes, and 25 studies looked at social support interventions. There was insufficient evidence of effectiveness for most of these intervention–outcome pairings and the panel rated most of the pairings as at least fair quality.

Exercise and physical activity

The expert panel did not reach consensus for several physical activity and exercise intervention–outcome pairings. First, the panel was split between ratings of sufficient and insufficient for stretching, flexibility, balance, or agility interventions to decrease fear of falling. Second, panel members did not agree on whether there was sufficient evidence that stretching, flexibility, balance or agility interventions improved self-efficacy, mastery, or locus of control. Panel members raised concerns about limited numbers of studies for any single outcome and about mixed results observed across the study outcomes. Finally, the expert panelists were split between evidence ratings of sufficient and insufficient for walking interventions that targeted anxiety or stress. Insufficient evidence was found for all other exercise and physical activity interventions.

Social support

The expert panel found insufficient evidence that the reviewed social support interventions improved emotional health.

Discussion

This review examined three broad types of interventions designed to promote emotional health: physical activity and/or exercise, skills training, and social support. Among the interventions rated as having at least fair quality and sufficient evidence, we found that skills training interventions reduced anxiety; enhanced self-efficacy; and improved vitality, role functioning related to emotional limitations, and emotional health as measured in quality of life subscales. Skills training interventions are theorized to promote positive domains of emotional health through cognitive reframing, strengthening coping resources, and increasing the amount of support (or quality of support). We acknowledge that skills training may improve emotional health through improved self-efficacy, though the panel chose to view self-efficacy as its own emotional health domain. These interventions are designed for older adults with chronic conditions (e.g., arthritis, heart disease, physical disabilities) or informal caregivers (e.g., spouses, adult children) of older adults coping with dementia, stroke survivors, or mental illness making them quite generalizable. These populations were targeted by these interventions because chronic conditions or caregiving responsibilities increase the need for skills training, support, information, and resources.

The CDSMP was used as an intervention in seven of the skills training studies that showed sufficient evidence for improving quality of life or self-efficacy or decreasing anxiety. CDSMP has been shown to enhance stress management techniques, improve communication with physicians, increase confidence in ability to manage the condition, and improve role function (32, 42, 155–159). Improving self-management skills has been shown to impact other aspects of participants’ lives, such as their ability to manage their emotions, choose healthy foods and exercise activities, and activate their social network (158). This review is limited by its end date of June 2008. While it is beyond the scope of this project to conduct an updated systematic literature review, we recently searched for other review papers on skills training, exercise and/or physical activity, and social support interventions to promote emotional health. We found two review papers (160, 161) that reported similar findings as we report above, namely, sufficient evidence for skills training interventions impact on self-efficacy and quality of life and insufficient evidence for other emotional health outcomes. We also searched for intervention studies for those areas where sufficient evidence was found. Our search yielded 10 recently published articles (162–171), none of which reported different findings than reported above.

We defined “insufficient evidence of effectiveness” in two ways: either there were not enough studies of at least fair quality, or there were multiple studies with inconclusive data. Insufficient evidence did not mean that interventions were clearly ineffective. Very few intervention–outcome pairings were rated as at least fair quality. The expert panel identified the following common quality limitations: lack of descriptive information about the interventions, limited information about the statistical methods and analyses, and small sample sizes or underpowered studies. Additionally, features of some of the study designs made it difficult to detect changes in emotional health. For example, many studies included emotional health outcome measures that may not be responsive to small changes from programs of limited intensity and duration, and sampling “emotionally healthy” subjects that created ceiling effects. In fact, many of the reviewed aerobic physical activity interventions did not meet current national guidelines (140) for 150 min per week of moderate-intensity activity (though all reviewed strength/resistance interventions did meet existing criteria of 2 days per week).

Our review included a wide range of emotional health constructs. Some outcomes were entirely emotional (e.g., anxiety), whereas others included a mix of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains (e.g., self-efficacy). In addition, some studies included emotional health outcomes as their primary outcomes, whereas others included emotional health as intermediate outcomes or mediators of other health outcomes. Finally, there was a dearth of intervention studies on certain emotional health constructs, such as hopelessness, shame, guilt, regret, fear, neuroticism, boredom, positive energy, contentment, hardiness, resilience, emotional stability, emotional regulation/control, altruism, capacity to care, and happiness. In particular, positive constructs were underrepresented in the available literature. We were not surprised that there was limited evidence on interventions to promote emotional health, and particularly any studies lacking in positive emotional health constructs given the tendency (up until recently) to focus on disease prevention over health promotion. We anticipate that more research will include emotional health outcomes as models such as the socio-ecological model (67, 172) and guidelines such as the Public Health Action Plan to Integrate Mental Health Promotion and Mental Illness Prevention with Chronic Disease Prevention, 2011–2015 (74) emphasize the importance of emotional health in the larger public health goals.

Future research needs to address these quality concerns by attending to limitations with both internal and external validity. One way to do so is to use the RE-AIM framework, a conceptual approach for evaluating the translation of research into practice in “real-world” settings (141). RE-AIM stands for reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation fidelity, and maintenance – five areas, which, if addressed, ensure that essential program goals are retained during the implementation process, resulting in greater external validity. More research is also needed to investigate the longer term, maintenance effects of interventions to promote positive emotional health, and address illness-related domains in older adults as most of the studies here were of short-term effectiveness. The prominence of theories such as social cognitive theory, social learning theory, and self-efficacy theory in those interventions with sufficient evidence may also be helpful to consider in future intervention design and development as they may have contributed to the optimization of participants’ quality of life and self-efficacy and minimization of anxiety symptoms.

Despite the gaps in the current research, our systematic review provides important information about interventions that can promote emotional health outcomes in community-dwelling older adults. Specifically, we found that skills training interventions resulted in improvements in both illness-related (anxiety) and positive (quality of life and self-efficacy) domains of emotional health. Given that more than one in four Americans lives with two or more concurrent chronic conditions, the challenges of managing multiple chronic conditions among the growing numbers of older persons are significant (50). One of the overarching goals of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Strategic Framework (58), Optimum Health and Quality of Life for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Conditions, is to “maximize the use of proven self-care management and other services by individuals with multiple chronic conditions.” As shown in this review, skills training interventions can offer important benefits in the realm of promoting emotional health in older adults. Given the expanding proportion of older adults in the US and globally, we hope this review will help in addressing some of challenges identified in this important area of study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This paper is included in the Research Topic, “Evidence-Based Programming for Older Adults.” This Research Topic received partial funding from multiple government and private organizations/agencies; however, the views, findings, and conclusions in these articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of these organizations/agencies. All papers published in the Research Topic received peer review from members of the Frontiers in Public Health (Public Health Education and Promotion section) panel of Review Editors. Because this Research Topic represents work closely associated with a nationwide evidence-based movement in the US, many of the authors and/or Review Editors may have worked together previously in some fashion. Review Editors were purposively selected based on their expertise with evaluation and/or evidence-based programming for older adults. Review Editors were independent of named authors on any given article published in this volume.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible through a contract with the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors (NACDD) to the University of Washington Health Promotion Research Center and funded by the CDC Healthy Aging Program’s Healthy Brain Initiative (U48-DP000050). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Hendrie HC, Albert MS, Butters MA, Gao S, Knopman DS, Launer LJ, et al. The NIH cognitive and emotional health project: report of the critical evaluation study committee. Alzheimers Dement (2006) 2:12–32 10.1016/j.jalz.2005.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Association of Chronic Disease Directors (NACDD). The State of Mental Health and Aging in America Issue Brief 1: What Do the Data Tell Us?. National Association of Chronic Disease Directors; (2008). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/mental_health.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Windle G, Linck P, Morgan R, Hughes D, Burholt V, Reeves C, et al. Public Health Interventions to Promote Mental Well-Being in People Aged 65 and Over: Systematic Review of Effectiveness and Costs-Effectiveness. (2008). Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=folder&o=36395

- 5.National Institutes of Health (NIH). Cognitive and Emotional Health Project: The Healthy Brain. (2001). Available from: http://trans.nih.gov/cehp/HBPemot.htm

- 6.Stevens A, Coon D, Wisniewski S, Vance D, Arguelles S, Belle S, et al. Measurement of leisure time satisfaction in family caregivers. Aging Ment Health (2004) 8:450–9. 10.1080/13607860410001709737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickinson P, Neilson G, Agee M. The sustainability of mentally healthy schools initiatives: insights from the experiences of a co-educational secondary school in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Int J Ment Health Promot (2004) 6(2):34–9 10.1080/14623730.2004.9721929 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haley W, Roth D, Coleton M, Ford G, West C, Collins R, et al. Appraisal, coping, and social support as mediators of well-being in black and white family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Consult Clin Psychol (1996) 64:121–9. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briss P, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, Fielding J, Wright-De Agüero L, Truman BI, et al. Developing an evidence-based guide to community preventive services-methods. Am J Prev Med (2000) 18(1S):35–43. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00119-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norris S, Nichols PJ, Caspersen CJ, Glasgow RE, Engelgau MM, Jack L, et al. The effectiveness of disease and case management for people with diabetes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med (2002) 22(4S):15–38. 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00423-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frederick JT, Steinman LE, Prohaska T, Satariano WA, Bruce M, Bryant L, et al. Community-based treatment of late life depression–an expert panel informed literature review. Am J Prev Med (2007) 33(3):222–49. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care (1992) 30:473–83 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizuno E, Hosak T, Ogihara R, Higano H, Mano Y. Effectiveness of a stress management program for family caregivers of the elderly at home. J Med Dent Sci (1999) 46(4):145–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coon DW, Thompson L, Steffen A, Sorocco K, Gallagher-Thompson D. Anger and depression management: psychoeducational skill training interventions for women caregivers of a relative with dementia. Gerontologist (2003) 43(5):678–89. 10.1093/geront/43.5.678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steffen AM. Anger management for dementia caregivers: a preliminary study using video and telephone interventions. Behav Ther (2000) 31(2):281–99. 10.1080/13607860903420989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.López J, Crespo M, Zarit SH. Assessment of the efficacy of a stress management program for informal caregivers of dependent older adults. Gerontologist (2007) 47(2):205–14. 10.1093/geront/47.2.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McHugh F, Lindsay GM, Hanlon P, Hutton I, Brown MR, Morrison C, et al. Nurse led shared care for patients on the waiting list for coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Heart (2001) 86(3):317–23. 10.1136/heart.86.3.317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlow JH, Turner AP, Wright CC. A randomized controlled study of the arthritis self-management programme in the UK. Health Educ Res (2000) 15(6):665–80. 10.1093/her/15.6.665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams SA, Schreier AM. The role of education in managing fatigue, anxiety, and sleep disorders in women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer. Appl Nurs Res (2005) 18(3):138–47. 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith C, Hancock H, Blake-Mortimer J, Eckert K. A randomised comparative trial of yoga and relaxation to reduce stress and anxiety. Complement Ther Med (2007) 15(2):77–83. 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai Y, Zhang S, Yamamoto J, Ao M, Belin TR, Cheung F, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy of minor depressive symptoms in elderly Chinese Americans: a pilot study. Community Ment Health J (1999) 35(6):537–42. 10.1023/A:1018763302198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui E, Lee PS, Woo J. Management of urinary incontinence in older women using videoconferencing versus conventional management: a randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare (2006) 12(7):343–7. 10.1258/135763306778682413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kretzer K, Davis J, Easa D, Johnson J, Harrigan R. Self identity through Ho’oponopono as adjunctive therapy for hypertension management. Ethn Dis (2007) 17(4):624–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright CC, Barlow JH, Turner AP, Bancroft GV. Self-management training for people with chronic disease: an exploratory study. Br J Health Psychol (2003) 8(Pt 4):465–76. 10.1348/135910703770238310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishizaki J, Meguro K, Ohe K, Kimura E, Tsuchiya E, Ishii H, et al. Therapeutic psychosocial intervention for elderly subjects with very mild Alzheimer disease in a community: the tajiri project. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord (2002) 16(4):261–9. 10.1097/00002093-200210000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brody BL, Roch-Levecq AC, Gamst AC, Maclean K, Kaplan RM, Brown SI. Self-management of age-related macular degeneration and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Ophthalmol (2002) 120(11):1477–83. 10.1001/archopht.120.11.1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham AJ. Integrating spirituality into a group psychological therapy program for cancer patients. Integr Cancer Ther (2005) 4(2):178–86. 10.1177/1534735405275648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evcik D, Sonel B. Effectiveness of a home-based exercise therapy and walking program on osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatol Int (2002) 22(3):103–6. 10.1007/s00296-002-0198-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duggleby WD, Degner L, Williams A, Wright K, Cooper D, Popkin D, et al. Living with hope: initial evaluation of a psychosocial hope intervention for older palliative home care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage (2007) 33(3):247–57. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kline KS, Scott LD, Britton AS. The use of supportive-educative and mutual goal-setting strategies to improve self-management for patients with heart failure. Home Healthc Nurse (2007) 25(8):502–10. 10.1097/01.NHH.0000289104.60043.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott LD, Setter-Kline K, Britton AS. The effects of nursing interventions to enhance mental health and quality of life among individuals with heart failure. Appl Nurs Res (2004) 17(4):248–56. 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, Brown BW, Jr, Bandura A, Ritter P, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care (1999) 37(1):5–14. 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis LL. Telephone-based interventions with family caregivers: a feasibility study. J Fam Nurs (1998) 4(3):255–70 10.1177/107484079800400303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mant J, Winner S, Roche J, Wade DT. Family support for stroke: one year follow up of a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2005) 76(7):1006–8. 10.1136/jnnp.2004.048991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnason SL, Zimmerman L, Nieveen J, Schmaderer M, Carranza B, Reilly S. Impact of a home communication intervention for coronary artery bypass graft patients with ischemic heart failure on self-efficacy, coronary disease risk factor modification, and functioning. Heart Lung (2003) 32(3):147–58 10.1016/S0147-9563(03)00036-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grant JS, Elliott TR, Weaver M, Bartolucci AA, Giger JN. Telephone intervention with family caregivers of stroke survivors after rehabilitation. Stroke (2002) 33(8):2060–5. 10.1161/01.STR.0000020711.38824.E3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace JI, Buchner DM, Grothaus L, Leveille S, Tyll L, LaCroix AZ, et al. Implementation and effectiveness of a community-based health promotion program for older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (1998) 53(4):M301–6. 10.1093/gerona/53A.4.M301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Markle-Reid M, Weir R, Browne G, Roberts J, Gafni A, Henderson S. Health promotion for frail older home care clients. J Adv Nurs (2006) 54(3):381–95. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03817.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes RB, Robinson-Whelen S, Taylor HB, Hall JW. Stress self-management: an intervention for women with physical disabilities. Womens Health Issues (2006) 16(6):389–99. 10.1016/j.whi.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pischke CR, Weidner G, Elliott-Eller M, Ornish D. Lifestyle changes and clinical profile in coronary heart disease patients with an ejection fraction of <or=40% or >40% in the multicenter lifestyle demonstration project. Eur J Heart Fail (2007) 9(9):928–34. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kocken PL, Voorham AJJ. Effects of a peer-led senior health education program. Patient Educ Couns (1998) 34(1):15–23. 10.1016/S0738-3991(98)00038-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swerissen H, Belfrage J, Weeks A, Jordan L, Walker C, Furler J, et al. A randomised control trial of a self-management program for people with a chronic illness from Vietnamese, Chinese, Italian and Greek backgrounds. Patient Educ Couns (2006) 64(1–3):360–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barlow JH, Williams B, Wright CC. Instilling the strength to fight the pain and get on with life’: learning to become an arthritis self-manager through an adult education programme. Health Educ Res (1999) 14(4):533–44. 10.1093/her/14.4.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorig K, Gonzalez VM, Ritter P. Community-based Spanish language arthritis education program: a randomized trial. Med Care (1999) 37(9):957–63. 10.1097/00005650-199909000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E, Meisel M. Impact of brief family psychoeducation on self-efficacy. Schizophr Bull (1996) 22(1):41–50. 10.1093/schbul/22.1.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E, Meisel M. Effectiveness of two models of brief family education: retention of gains by family members of adults with serious mental illness. Am J Orthopsychiatry (1997) 67(2):177–86. 10.1037/h0080221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forster A, Young J. Specialist nurse support for patients with stroke in the community: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ (1996) 312(7047):1642–6. 10.1136/bmj.312.7047.1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu-Ambrose T, Khan KM, Eng JJ, Lord SR, McKay HA. Balance confidence improves with resistance or agility training. Gerontology (2004) 50(6):373–82. 10.1159/000080175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ross MC, Bohannon AS, Davis DC, Gurchiek L. The effects of a short-term exercise program on movement, pain, and mood in the elderly: results of a pilot study. J Holist Nurs (1999) 17(2):139–47. 10.1177/089801019901700203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson G. Chronic Care: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: (2010). Available from: http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2010/rwjf54583 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daley AJ, Crank H, Saxton JM, Mutrie N, Coleman R, Roalfe A. Randomized trial of exercise therapy in women treated for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol (2007) 25(13):1713–21. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kolt GS, Schofield GM, Kerse N, Garrett N, Oliver M. Effect of telephone counseling on physical activity for low-active older people in primary care: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc (2007) 55(7):986–92. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kutner NG, Barnhart H, Wolf SL, McNeely E, Xu T. Self-report benefits of Tai Chi practice by older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci (1997) 52(5):242–6. 10.1093/geronb/52B.5.P242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartford K, Wong C, Zakaria D. Randomized controlled trial of a telephone intervention by nurses to provide information and support to patients and their partners after elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery: effects of anxiety. Heart Lung (2002) 31(3):199–206. 10.1067/mhl.2002.122942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smart N, Haluska B, Jeffriess L, Marwick TH. Predictors of a sustained response to exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: a telemonitoring study. Am Heart J (2005) 150(6):1240–7. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clark DO, Stump TE, Damush TM. Outcomes of an exercise program for older women recruited through primary care. J Aging Health (2003) 15(3):567–85. 10.1177/0898264303253772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Quinney HA, Fields AL, Jones LW, Fairey AS. A randomized trial of exercise and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (2003) 12(4):347–57. 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2003.00437.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Multiple Chronic Conditions—A Strategic Framework: Optimum Health and Quality of Life for Individuals with Multiple Chronic Conditions. Washington, DC: (2010). Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/ash/initiatives/mcc/mcc_framework.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 59.King AC, Taylor CB, Haskell WL. Effects of differing intensities and formats of 12 months of exercise training on psychological outcomes in older adults. Health Psychol (1993) 12(4):292–300. 10.1037/0278-6133.12.5.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.King AC, Baumann K, O’Sullivan P, Wilcox S, Castro C. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on physiological, behavioral, and emotional responses to family caregiving: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2002) 57(1):M26–36. 10.1093/gerona/57.1.M26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Focht BC, Brawley LR, Rejeski WJ, Ambrosius WT. Group-mediated activity counseling and traditional exercise therapy programs: effects on health-related quality of life among older adults in cardiac rehabilitation. Ann Behav Med (2004) 28(1):52–61. 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gary R. Exercise self-efficacy in older women with diastolic heart failure: results of a walking program and education intervention. J Gerontol Nurs (2006) 32(7):31–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gendron CE, Poitras LR, Engels ML, Dastoor DP, Sirota SE, Barza SL, et al. Skills training with supporters of the demented. J Am Geriatr Soc (1986) 34(12):875–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Halbert JA, Silagy CA, Finucane PM, Withers RT, Hamdorf PA. Physical activity and cardiovascular risk factors: effect of advice from an exercise specialist in Australian general practice. Med J Aust (2000) 173(2):84–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Slivinske LR, Fitch VL. The effect of control enhancing interventions on the well-being of elderly individuals living in retirement communities. Gerontologist (1987) 27(2):176–81 10.1093/geront/27.2.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Acorn S. Assisting families of head-injured survivors through a family support programme. J Adv Nurs (1995) 21(5):872–7. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21050872.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Promoting Positive Mental Health Through A Socio-Ecological Approach. Centers for Addictions Research of BC; (2011). Available from: http://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/sites/default/files/CARBC-campusdoc1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chien MY, Yang RS, Tsauo JY. Home-based trunk-strengthening exercise for osteoporotic and osteopenic postmenopausal women without fracture – a pilot study. Clin Rehabil (2005) 19(1):28–36. 10.1191/0269215505cr844oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Etkin CD, Prohaska TR, Harris BA, Latham N, Jette A. Feasibility of implementing the strong for life program in community settings. Gerontologist (2006) 46(2):284–92. 10.1093/geront/46.2.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hébert R, Lévesque L, Vézina J, Lavoie JP, Ducharme F, Gendron C, et al. Efficacy of a psychoeducative group program for caregivers of demented persons living at home: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci (2003) 58B(1):S58–67. 10.1093/geronb/58.1.S58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stewart AL, Mills KM, Sepsis PG, King AC, McLellan BY, Roitz K, et al. Evaluation of CHAMPS, a physical activity promotion program for older adults. Ann Behav Med (1997) 19(4):353–61. 10.1007/BF02895154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stewart M, Craig D, MacPherson K, Alexander S. Promoting positive affect and diminishing loneliness of widowed seniors through a support intervention. Public Health Nurs (2001) 18(1):54–63. 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Molloy GJ, Johnston DW, Gao C, Witham MD, Gray JM, Argo IS. Effects of an exercise intervention for older heart failure patients on caregiver burden and emotional distress. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil (2006) 13(3):381–7. 10.1097/01.hjr.0000198916.60363.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Action Plan to Integrate Mental Health Promotion and Mental Illness Prevention with Chronic Disease Prevention, 2011–2015. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Singh NA, Clements KM, Singh MA. The efficacy of exercise as a long-term antidepressant in elderly subjects: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2001) 56(8):M497–504. 10.1093/gerona/56.8.M497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garand L, Buckwalter KC, Lubaroff D, Tripp-Reimer T, Frantz RA, Ansley TN. A pilot study of immune and mood outcomes of a community-based intervention for dementia caregivers: the PLST intervention. Arch Psychiatr Nurs (2002) 16(4):156–67. 10.1053/apnu.2002.34392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Inokuchi S, Matsusaka N, Hayashi T, Shindo H. Feasibility and effectiveness of a nurse-led community exercise programme for prevention of falls among frail elderly people: a multi-centre controlled trial. J Rehabil Med (2007) 39(6):479–85. 10.2340/16501977-0080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Losito J, Murphy S, Thomas M. The effects of group exercise on fatigue and quality of life during cancer treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum (2006) 33(4):821–5. 10.1188/06.ONF.821-825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderson RT, King A, Stewart AL, Camacho F, Rejeski WJ. Physical activity counseling in primary care and patient well-being: do patients benefit? Ann Behav Med (2005) 30(2):146–54. 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Munro JF, Nicholl JP, Brazier JE, Davey R, Cochrane T. Cost effectiveness of a community based exercise programme in over 65 year olds: cluster randomised trial. J Epidemiol Community Health (2004) 58(12):1004–10. 10.1136/jech.2003.014225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mutrie N, Campbell AM, Whyte F, McConnachie A, Emslie C, Lee L, et al. Benefits of supervised group exercise programme for women being treated for early stage breast cancer: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ (2007) 334(7592):517. 10.1136/bmj.39094.648553.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Toseland RW, Rossiter CM, Peak T, Smith GC. Comparative effectiveness of individual and group interventions to support family caregivers. Soc Work (1990) 35(3):209–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bogat G, Jason LA. An evaluation of two visiting programs for elderly community residents. Int J Aging Hum Dev (1983) 17(4):267–80. 10.2190/6AQX-1TDM-DEL4-3T6L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jette AM, Harris BA, Sleeper L, Lachman ME, Heislein D, Giorgetti M, et al. A home-based exercise program for nondisabled older adults. J Amer Geriatr Soc (1996) 44(6):644–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lin MR, Wolf SL, Hwang HF, Gong SY, Chen CY. A randomized, controlled trial of fall prevention programs and quality of life in older fallers. J Am Geriatr Soc (2007) 55(4):499–506. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Austin EN, Johnston YA, Morgan LL. Community gardening in a senior center: a therapeutic intervention to improve the health of older adults. Ther Recreation J (2006) 40(1):48–56. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen KM, Snyder M, Kirchbaum K. Tai chi and well-being of Taiwanese community-dwelling elders. Clin Gerontol (2001) 24(3–4):137–56 10.1300/J018v24n03_12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Devereux K, Robertson D, Briffa NK. Effects of a water-based program on women 65 years and over: a randomised controlled trial. Aust J Physiother (2005) 51(2):102–8. 10.1016/S0004-9514(05)70038-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Logiudice D, Waltrowicz W, Brown K, Burrows C, Ames D, Flicker L. Do memory clinics improve the quality of life of carers? A randomized pilot trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (1999) 14(8):626–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li F, Fisher KJ, Harmer P, McAuley E. Falls self-efficacy as a mediator of fear of falling in an exercise intervention for older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci (2005) 60(1):34–40. 10.1093/geronb/60.1.P34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Means KM, O’Sullivan PS, Rodell DE. Psychosocial effects of an exercise program in older persons who fall. J Rehabil Res Dev (2003) 40(1):49–58. 10.1682/JRRD.2003.01.0049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Resnick B, Orwig D, Yu-Yahiro J, Hawkes W, Shardell M, Hebel JR, et al. Testing the effectiveness of the exercise plus program in older women post-hip fracture. Ann Behav Med (2007) 34(1):67–76. 10.1007/BF02879922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Drummond MF, Mohide EA, Tew M, Streiner DL, Pringle DM, Gilbert JR. Economic evaluation of a support program for caregivers of demented elderly. Int J Technol Assess Health Care (1991) 7(2):209–19 10.1017/S0266462300005109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hartman CA, Manos TM, Winter C, Hartman DM, Li B, Smith JC. Effects of T’ai Chi training on function and quality of life indicators in older adults with osteoarthritis. J Am Geriatr Soc (2000) 48(12):1553–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Taylor-Piliae RE, Haskell WL, Waters CM, Froelicher ES. Change in perceived psychosocial status following a 12-week Tai Chi exercise programme. J Adv Nurs (2006) 54(3):313–29. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03809.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cheung BM, Lo JL, Fong DY, Chan MY, Wong SH, Wong VC, et al. Randomised controlled trial of qigong in the treatment of mild essential hypertension. J Hum Hypertens (2005) 19(9):697–704. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Christopher KA, Morrow LL. Evaluating a community-based exercise program for women cancer survivors. Appl Nurs Res (2004) 17(2):100–8. 10.1016/S0897-1897(04)00024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gross CR, Kreitzer MJ, Russas V, Treesak C, Frazier PA, Hertz MI. Mindfulness meditation to reduce symptoms after organ transplant: a pilot study. Adv Mind Body Med (2004) 20(2):20–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, Winegard K, Ferko N, Parkinson W, Cook RJ, et al. Efficacy of home-based exercise for improving quality of life among elderly women with symptomatic osteoporosis-related vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int (2003) 14(8):677–82. 10.1007/s00198-003-1423-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Smith TL, Toseland RW. The effectiveness of a telephone support program for caregivers of frail older adults. Gerontologist (2006) 46(5):620–9. 10.1093/geront/46.5.620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fisher K, Li FA. Community-based walking trial to improve neighborhood quality of life in older adults: a multilevel analysis. Ann Behav Med (2004) 28(3):186–94. 10.1207/s15324796abm2803_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Castro CM, Wilcox S, O’Sullivan P, Baumann K, King AC. An exercise program for women who are caring for relatives with dementia. Psychosom Med (2002) 64(3):458–68. 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pinto BM, Frierson GM, Rabin C, Trunzo JJ, Marcus BH. Home-based physical activity intervention for breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol (2005) 23(15):3577–87. 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stewart AL, King AC, Haskell WL. Endurance exercise and health-related quality of life in 50-65 year-old adults. Gerontologist (1993) 33(6):782–9. 10.1093/geront/33.6.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell RT, Huber G, Pollak N, Sharma L, et al. Long-term impact of fit and strong! on older adults with osteoarthritis. Gerontologist (2006) 46(6):801–14. 10.1093/geront/46.6.801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Senuzun F, Fadiloglu C, Burke LE, Payzin S. Effects of home-based cardiac exercise program on the exercise tolerance, serum lipid values and self-efficacy of coronary patients. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil (2006) 13(4):640–5. 10.1097/01.hjr.0000198445.41860.ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shin Y. The effects of a walking exercise program on physical function and emotional state of elderly Korean women. Public Health Nurs (1999) 16(2):146–54. 10.1046/j.1525-1446.1999.00146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Heller K, Thompson MG, Trueba PE, Hogg JR, Vlachos-Weber I. Peer support telephone dyads for elderly women: was this the wrong intervention? Am J Community Psychol (1991) 19(1):53–74. 10.1007/BF00942253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dröes RM, Breebaart E, Ettema TP, van Tilburg W, Mellenbergh GJ. Effect of integrated family support versus day care only on behavior and mood of patients with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr (2000) 12(1):99–115. 10.1017/S1041610200006232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ruhland JL, Shields RK. The effects of a home exercise program on impairment and health-related quality of life in persons with chronic peripheral neuropathies. Phys Ther (1997) 77(10):1026–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Alexander MJL, Butcher JE, MacDonald PB. Effect of a water exercise program on walking gait, flexibility, strength, self-reported disability and other psycho-social measures of older individuals with arthritis. Physiother Can (2001) 53(3):203–11. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bennett JA, Young HM, Nail LM, Winters-Stone K, Hanson G. A telephone-only motivational intervention to increase physical activity in rural adults: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res (2008) 57(1):24–32. 10.1097/01.NNR.0000280661.34502.c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dröes RM, Meiland F, Schmitz M, van Tilburg W. Effect of combined support for people with dementia and carers versus regular day care on behaviour and mood of persons with dementia: results from a multi-centre implementation study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry (2004) 19(7):673–84. 10.1002/gps.1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Emery CF, Gatz M. Psychological and cognitive effects of an exercise program for community-residing older adults. Gerontologist (1990) 30(2):184–8. 10.1093/geront/30.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Foley A, Halbert J, Hewitt T, Crotty M. Does hydrotherapy improve strength and physical function in patients with osteoarthritis – a randomised controlled trial comparing a gym based and a hydrotherapy based strengthening programme. Ann Rheum Dis (2003) 62(12):1162–7. 10.1136/ard.2002.005272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Jeong S, Kim MT. Effects of a theory-driven music and movement program for stroke survivors in a community setting. Appl Nurs Res (2007) 20(3):125–31. 10.1016/j.apnr.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Savage P, Ricci MA, Lynn M, Gardner A, Knight S, Brochu M, et al. Effects of home versus supervised exercise for patients with intermittent claudication. J Cardiopulm Rehabil (2001) 21(3):152–7. 10.1097/00008483-200105000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wilcox S, Dowda M, Griffin SF, Rheaume C, Ory MG, Leviton L, et al. Results of the first year of active for life: translation of 2 evidence-based physical activity programs for older adults into community settings. Am J Health (2006) 96(7):1201–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Beaupre LA, Lier D, Davies DM, Johnston DB. The effect of a preoperative exercise and education program on functional recovery, health related quality of life, and health service utilization following primary total knee arthroplasty. J Rheumatol (2004) 31(6):1166–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kerse N, Elley C, Robinson E, Arroll B. Is physical activity counseling effective for older people? A cluster randomized, controlled trial in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc (2005) 53(11):1951–6. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.van den Heuvel ET, Witte LP, Stewart RE, Schure LM, Sanderman R, Meyboom-de Jong B. Long-term effects of a group support program and an individual support program for informal caregivers of stroke patients: which caregivers benefit the most? Patient Educ Couns (2002) 47(4):291–9. 10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00230-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Barrett CJ, Smerdely P. A comparison of community-based resistance exercise and flexibility exercise for seniors. Aust J Physiother (2002) 48(3):215–9. 10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60226-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Hernández MT, Rubio TM, Ruiz FO, Riera HS, Gil RS, Gómez JC. Results of a home-based training program for patients with COPD. Chest (2000) 118(1):106–14. 10.1378/chest.118.1.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Murray J, Manela M, Shuttleworth A, Livingston G. An intervention study with husband and wife carers of older people with a psychiatric illness. J Affect Disord (1997) 46(3):279–84. 10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00098-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Stenstrom CH. Home exercise in rheumatoid arthritis functional class II: goal setting versus pain attention. J Rheumatol (1994) 21(4):627–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Greendale GA, Salem GJ, Young JT, Damesyn M, Marion M, Wang MY, et al. A randomized trial of weighted vest use in ambulatory older adults: strength, performance, and quality of life outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc (2000) 48(3):305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hughes SL, Seymour RB, Campbell R, Pollak N, Huber G, Sharma L. Impact of the fit and strong intervention on older adults with osteoarthritis. Gerontologist (2004) 44(2):217–28. 10.1093/geront/44.2.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Larson J, Franzén-Dahlin A, Billing E, Arbin M, Murray V, Wredling R. The impact of a nurse-led support and education programme for spouses of stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Nurs (2005) 14(8):995–1003. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Tsutsumi T, Don BM, Zaichkowsky LD, Delizonna LL. Physical fitness and psychological benefits of strength training in community dwelling older adults. Appl Human Sci (1997) 16(6):257–66. 10.2114/jpa.16.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.van Uffelen JG, Chin A, Paw MJ, Hopman-Rock M, van Mechelen W. The effect of walking and vitamin B supplementation on quality of life in community-dwelling adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized, controlled trial. Qual Life Res (2007) 16(7):1137–46. 10.1007/s11136-007-9219-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Chin A, Paw MJ, de Jong N, Schouten EG, van Staveren WA, Kok FJ. Physical exercise or micronutrient supplementation for the wellbeing of the frail elderly? A randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med (2002) 36(2):126–31. 10.1136/bjsm.36.2.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.King AC, Pruitt LA, Phillips W, Oka R, Rodenburg A, Haskell WL. Comparative effects of two physical activity programs on measured and perceived physical functioning and other health-related quality of life outcomes in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2000) 55(2):M74–83. 10.1093/gerona/55.2.M74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bravo G, Gauthier P, Roy PM, Payette H, Gaulin P. A weight-bearing, water-based exercise program for osteopenic women: its impact on bone, functional fitness, and well-being. Arch Phys Med Rehabil (1997) 78(12):1375–80. 10.1016/S0003-9993(97)90313-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.de Vreede PL, van Meeteren NL, Samson MM, Wittink HM, Duursma SA, Verhaar HJ. The effect of functional tasks exercise and resistance exercise on health-related quality of life and physical activity. A randomised controlled trial. Gerontology (2007) 53(1):12–20. 10.1159/000095387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mant J, Carter J, Wade DT, Winner S. Family support for stroke: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2000) 356(9232):808–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67276-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Blumenthal JA, Emery CF, Madden DJ, Schniebolk S, Walsh-Riddle M, George LK. Long-term effects of exercise on psychological functioning in older men and women. J Gerontol (1991) 46(6):352–61. 10.1093/geronj/46.6.P352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci (2005) 60(6):768–76. 10.1093/gerona/60.6.768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Barker C. The value of home support for cancer patients: a study. Nurs Stand (1997) 11(32):34–7. 10.7748/ns1997.04.11.32.34.c2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Walsh K, Jones L, Tookman A, Mason C, McLoughlin J, Blizard R, et al. Reducing emotional distress in people caring for patients receiving specialist palliative care. Randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry (2007) 190:142–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity Guidelines for Older Adults. Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; (2011). Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/guidelines/olderadults.html [Google Scholar]

- 141.Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD. The re-aim framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns (2001) 44:119–27. 10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00186-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ducharme F, Trudeau D. Qualitative evaluation of a stress management intervention for elderly caregivers at home: a constructivist approach. Issues Ment Health Nurs (2002) 23(7):691–713. 10.1080/01612840290052820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]