Abstract

Purpose

Smokers have a higher risk of developing non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) than nonsmokers, but the relative risk of developing second primary lung cancer (SPLC) is unclear. Determining the risk of SPLC in smokers versus nonsmokers after treatment of an initial cancer may help guide recommendations for long-term surveillance.

Methods

Patients who underwent resection for stage I adenocarcinoma were identified from a prospectively maintained institutional database. Patients with other histologies, synchronous lesions, or who received neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy were excluded. SPLC were identified based on Martini criteria.

Results

From 1995 to 2012, 2151 patients underwent resection for stage I adenocarcinoma (308 never-smokers [14%] and 1843 ever-smokers [86%]). Thirty never-smokers (9.9%) and 145 ever-smokers (7.8%) developed SPLC. SPLC was detected by surveillance computed tomography scan in the majority of patients (161; 92%). In total, 87% of never-smokers and 83% of ever-smokers had stage I SPLC. There was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of SPLC between never-smokers and ever-smokers (p=0.18) in a competing-risks analysis. The cumulative incidence at 10 years was 20.3% for never-smokers and 18.2% for ever-smokers.

Conclusions

Although smokers have a greater risk of developing NSCLC, the risk of developing a second primary cancer after resection of stage I lung cancer is comparable between smokers and never smokers. The majority of these second primary cancers are detectable at a curable stage. Ongoing postoperative surveillance should be recommended for all patients regardless of smoking status.

Keywords: Metachronous, Lung, Never, Smoking, Recurrences

Introduction

An estimated 412,230 patients were living with lung cancer in the United States in 2012, 226,160 of whom were newly diagnosed [1]. Although the majority of these cases are related to smoking, 10% to 15% of cases occur in never-smokers, making lung cancer a leading cause of cancer-related death in never-smokers [2, 3]. Whether lung cancer in never-smokers represents a different epidemiology and biology than in smokers remains a matter of debate, but nearly all cases of lung cancer in never-smokers are adenocarcinomas [4–8].

Although most patients with lung cancer present with advanced disease, a significant number have early-stage disease that is amenable to complete resection [1]. Patients who undergo resection for pathologic stage IA and IB lung cancer have an estimated 5-year survival of 58% to 73% [9]. Since the publication of the National Lung Screening Trial, the number of patients diagnosed with early-stage disease is expected to increase, as screening becomes more common [10]. After resection of stage I disease, these patients remain at risk for both recurrences and development of second primary lung cancer (SPLC) [11, 12].

SPLC, unlike recurrences, often presents as early-stage disease that may be completely resectable with reasonable long-term survival [13–15]. As with most early-stage lung cancers, SPLC is often asymptomatic; therefore, surveillance for SPLC is critical for detection at an early stage [16, 17]. The incidence of SPLC in never-smokers has not been well-characterized, although some studies report a very low incidence [11].

Recently, the American Association for Thoracic Surgery recommended annual low-dose computed tomography (CT) scan for the detection of SPLC for lung cancer survivors until age 79 [18]. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer is also working to produce screening guidelines [19], but the recommendations from these guidelines are independent of smoking status. Although nonsmokers have, in general, a lower risk of developing non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) than smokers, it is unclear whether the risk of developing a second primary cancer differs between nonsmokers and smokers who have developed and been treated for an initial lung cancer. We examined the incidence of SPLC in never-smokers and ever-smokers after complete resection of stage I adenocarcinoma.

Patients and Methods

Data Collection and Clinical Assessment

A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained thoracic surgery database identified all patients who underwent resection for stage I lung cancer at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center from 1995 to 2012. Patients were designated as ever-smokers or never-smokers from self-reports at the time of the initial consultation. The ever-smokers included patients who were former or current cigarette smokers, and the never-smokers included patients who had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. All patients with completely resected pathologic stage IA and IB adenocarcinoma were included. Staging included preoperative history and physical examination, laboratory assessment, CT scan of the chest/upper abdomen, and positron emission tomography (PET) scan in most patients. Staging was based on the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual. Patients with other histologies (including squamous cell carcinoma), synchronous NSCLC, receipt of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy, R1 or R2 resection, or previous nonthoracic cancers were excluded. All patients were treated at our institution. A subset of these patients were previously reported on in an earlier publication [12]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Surveillance Protocol

Surveillance was conducted according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, with history and physical examination as well as CT scan of the chest/upper abdomen every 6 to 12 months for the first 2 years and yearly thereafter. Bronchoscopy, PET scan, and serum markers were not included in routine surveillance. The patients were initially monitored by a thoracic surgeon or an oncologist; after two years, some patients were monitored by a nurse practitioner as part of a thoracic survivorship program.

Second Primary Lung Cancer

The primary endpoint was the development of SPLC. Secondary endpoints were death after treatment of SPLC and the method of detection of SPLC. Data extracted included date of recurrence, date of development of SPLC, method of detection, treatment of SPLC (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or ablation), and date of death or last follow-up. Method of detection distinguished between routine surveillance and evaluation for symptoms.

SPLC was primarily defined using the criteria of Martini and Melamed with the inclusion of morphologic or mutational differences where necessary [20]. A pulmonary lesion was defined as an SPLC if it met one of the three following criteria: (1) Histology different from the index tumor; (2) same histology as the index tumor but diagnosed more than two years after the primary tumor; (3) same histology as the index tumor, diagnosed within two years of treatment of the index tumor, but in a different lobe or segment, without intervening positive lymph nodes and no evidence of metastatic disease. Cases where the primary and secondary lesions were morphologically different (eg, lepidic vs. micropapillary) or had differing mutation status (eg, EGFR-positive vs. EGFR-negative) were considered different histologies and were managed clinically as separate primaries.

Statistical Analysis

Because the risk of developing a second primary, the risk of recurrence of the initial cancer, and the risk of death were likely to affect each other, we used a competing-risks approach. The event of primary interest was the diagnosis of SPLC, with recurrence and death treated as competing risks [21]. Patients received follow-up from initial surgery for lung cancer until a second primary, recurrence, or death was observed—whichever came first. Patients who did not experience any of the three events during the study period were censored at the time of the last available follow-up. The cumulative risk of experiencing each event over time was estimated using a cumulative incidence function and compared between never- and ever-smokers using Gray’s test. Hazard ratios for the subdistribution were estimated using the Gray and Fine model [22].

Additional analyses investigated survival after treatment of SPLC and overall survival from initial surgery for the entire cohort. In each analysis, patients received follow-up until death. Patients who did not die during the study period were censored at the time of the last available follow-up. Survival probabilities were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared across groups using the log-rank test (nonparametric analysis) and Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

Patient and Treatment Characteristics

Of the 2151 patients with stage I adenocarcinoma identified from the database, 308 (14%) were never-smokers and 1843 (86%) were current or former smokers. Median follow-up among patients developing SPLC was 4.3 years (range, 0 to 16.7 years). In total, 382 patients developed recurrences, and 175 developed SPLC; 631 patients died during the study period, 320 of whom had no reported recurrence or SPLC. The median age of both groups was approximately 67 years. Women composed 79% of never-smokers (244/308) and 60% of ever-smokers (1106/1843) (p=0.001). Lobectomy was the initial operation for 69% of never-smokers (213/308) and 68% of ever-smokers (1245/1843). Nonanatomic resections, segmentectomies, and bilobectomies accounted for a minority of initial operations. Complete demographic details of the initial resections are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Never-Smokers and Ever-Smokers Who Underwent Resection for Stage I Adenocarcinoma

| Characteristic | Never-Smokers (N=308) |

Ever-Smokers (N=1843) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 244 (79) | 1106 (60) | 0.001 |

| Age at first operation, years (mean ± SD) | 68 ± 12 | 68 ± 9 | 0.99 |

| Stage | |||

| IA | 236 (77) | 1382 (75) | 0.34 |

| IB | 72 (23) | 458 (25) | |

| Location of first tumor | |||

| Right upper lobe | 98 (32) | 712 (39) | 0.02 |

| Right middle lobe | 15 (5) | 101 (5) | |

| Right lower lobe | 66 (21) | 332 (18) | |

| Left upper lobe | 74 (24) | 467 (25) | |

| Left lower lobe | 55 (18) | 227 (12) | |

| First operation | |||

| Lobectomy | 213 (69) | 1245 (68) | 0.13 |

| Wedge | 60 (19) | 392 (21) | |

| Segmentectomy | 27 (9) | 188 (10) | |

| Bilobectomy | 6 (2) | 15 (0.8) | |

| Pneumonectomy | 2 (1) | 3 (0.2) |

Data are no. (%), unless otherwise noted.

Among the study population, 9.7% of never-smokers (30/308) and 7.9% of ever-smokers (145/1843) developed SPLC. Among those who developed SPLC, 77% of never-smokers (236/308) and 75% of ever-smokers (1382/1843) had stage IA adenocarcinoma as the initial pathology. The remaining patients had stage IB adenocarcinoma.

Method of Detection

SPLC was detected by surveillance CT scan in 97% of never-smokers (29/30) and 91% of ever-smokers (132/145). Less than 10% of the patients in both groups were detected symptomatically or incidentally. Details of detection are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Method of Detection of Second Primary Lung Cancer

| Method | Never-Smokers (N=30) |

Ever-Smokers (N=145) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surveillance CT scan | 29 (97) | 132 (91) | 0.3 |

| Symptoms | 1 (3) | 8 (6) | |

| Incidental | 0 | 3 (2) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (1) |

Data are no. (%).

Second Primary Lung Cancer

Among the never-smokers and ever-smokers who developed SPLC, 80% of never-smokers (24/30) and 73% of ever-smokers (106/145) developed stage IA SPLC. SPLC was treated surgically in 77% of never-smokers (23/30) and 87% of ever-smokers (126/145). Given that the majority of patients had previously undergone lobectomy, only 10% of never-smokers (3/30) and 23% of ever-smokers (33/145) underwent a subsequent lobectomy; instead, 53% of never-smokers (16/30) and 46% of ever-smokers (67/145) who developed stage IA SPLC underwent nonanatomic wedge resection.

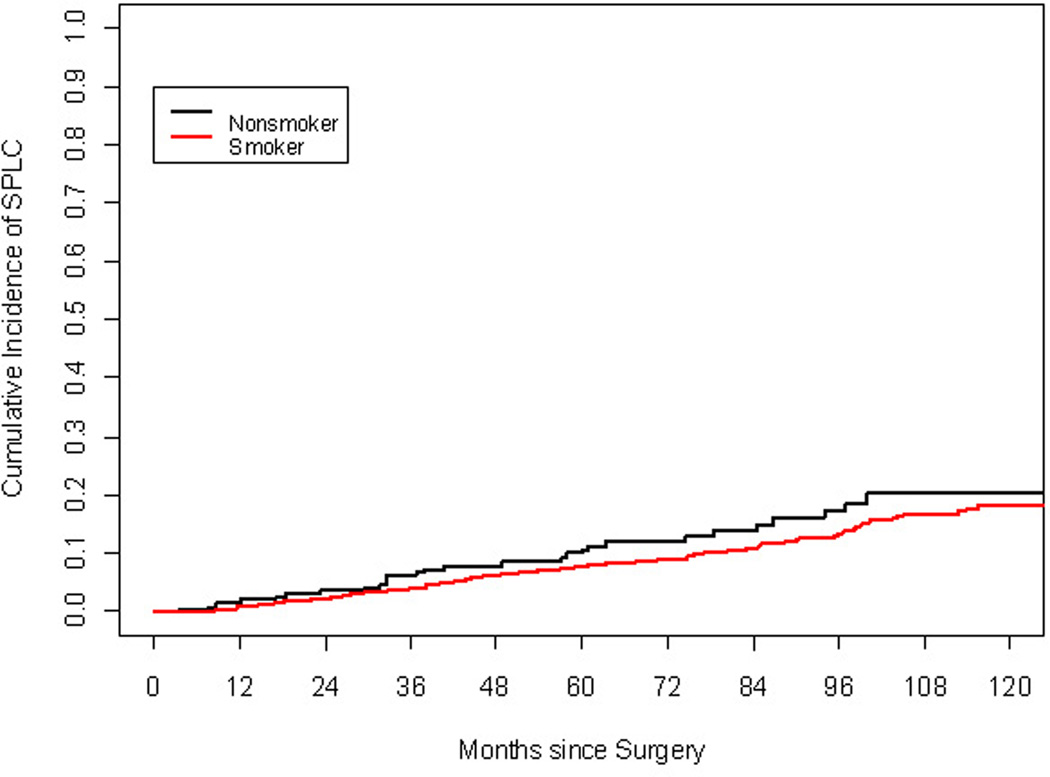

The cumulative incidence of SPLC at 5 and 10 years was 9.9% and 20.3% for never-smokers and 7.8% and 18.2% for ever-smokers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.88 to 1.92; p=0.18). The cumulative incidence of recurrence at 10 years was 26.7% for never-smokers and 29.7% for ever-smokers (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.09; p=0.61) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Competing-risks analysis of the cumulative incidence of second primary lung cancer (p=0.16) by smoking status.

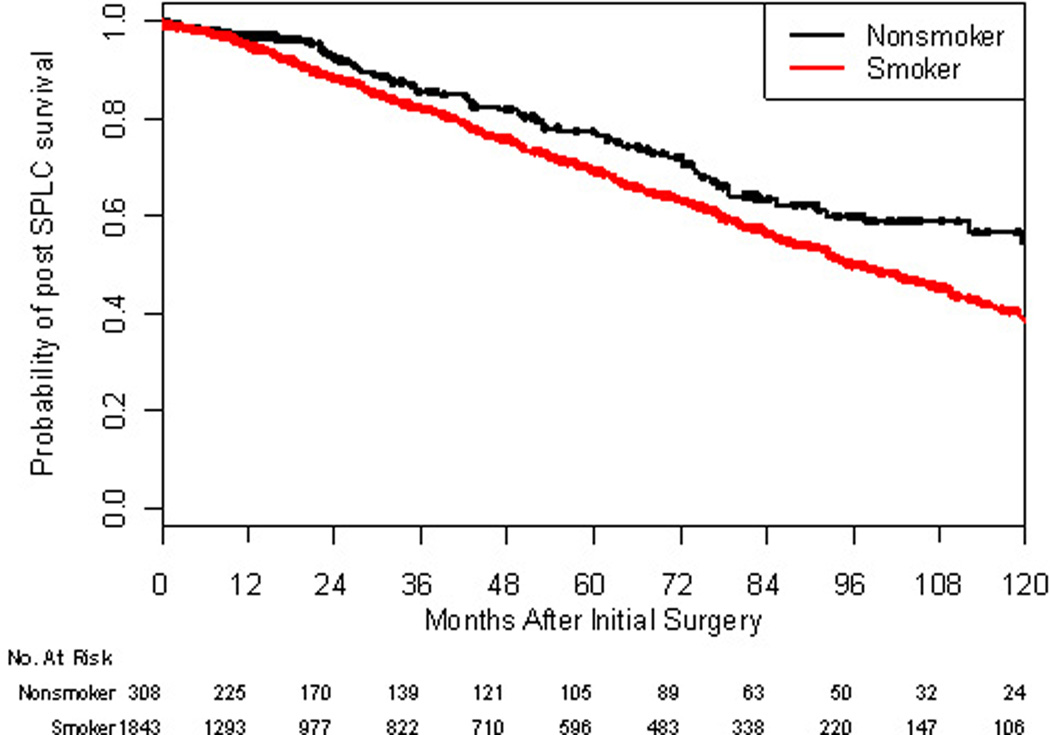

Clinical Outcomes

Overall survival after the first resection for lung cancer was calculated for never-smokers and ever-smokers (Figure 2). For ever-smokers, 5- and 10-year survival was 69% and 38%; for never-smokers, 78% and 54%. The HR of death for ever-smokers versus never-smokers was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.06 to 1.73; p= 0.01), signifying an association between worse mortality and smoking in the patients studied.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier graph of overall survival for patients after resection of stage IA or IB adenocarcinoma by smoking status (p=0.014).

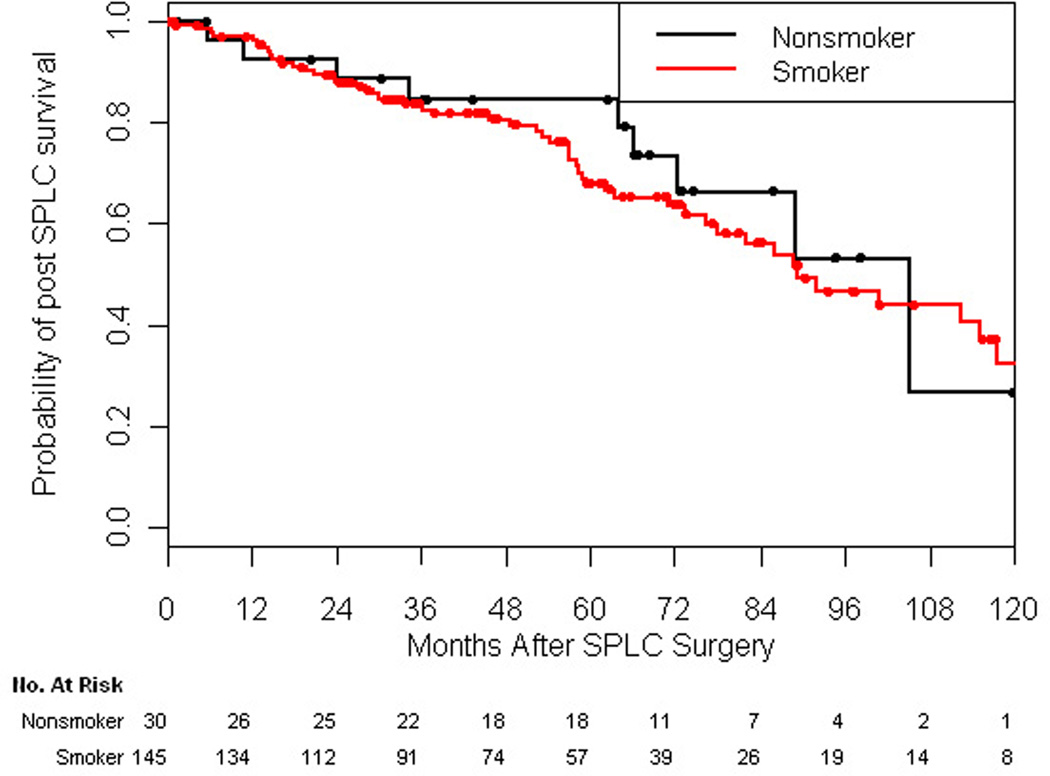

Prolonged survival was observed after treatment of SPLC. Median survival after treatment of SPLC was 7.45 years among ever-smokers and 8.78 years among never-smokers (Figure 3). Five-year survival after resection for SPLC was 68% for ever-smokers and 85% for never-smokers (p=0.18). Of note, the HR of death after treatment of SPLC for ever-smokers versus never-smokers was not significantly different (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.59 to 2.46; p=0.61).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier graph of overall survival for patients after treatment of second primary lung cancer by smoking status (p=0.18).

Comment

NSCLC is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States, yet the benefit of screening has only recently been demonstrated [1, 10]. Although the National Lung Screening Trial revealed a reduction in lung cancer–specific deaths among high-risk patients, the incidence of lung cancer is still less than 1%. In contrast to screening, postoperative surveillance is aimed at a potentially higher-risk group, given the history of lung cancer. These patients are at risk for both recurrences and SPLC. The incidence of SPLC is 1% to 6% per year; therefore, these patients have a high likelihood of benefitting from surveillance [12, 23, 24]. This potential benefit has led the American Association for Thoracic Surgery to recommend surveillance for the detection of SPLC after complete resection of lung cancer [18]. Whether never smokers have a lower risk than smokers for developing SPLC remains unclear. Our study suggests that never smokers and smokers have a similar risk of developing SPLC after initial resection of stage I adenocarcinoma.

Demographic details of never smokers compared with ever smokers revealed that the number of women in the never smoker cohort was significantly greater. Sixty percent of ever smokers and 79% of never smokers were women (p=0.001). Although the reason for the higher percentage of women is not clear, this finding is consistent with the literature [25]. Thun and colleagues reported that among never smokers, more women than men have lung cancer and that this difference increases with age [26]. Wakelee and colleagues reported that the incidence of lung cancer was higher in never smoker women than never smoker men although the difference was not significant [27]. Henschke and colleagues reported that women are more likely to be diagnosed when screened with CT scan [28]. Although the explanation for these findings remains unclear, the imbalance in our study population is representative of the never smokers at risk of developing lung cancer in the general population.

Overall survival of patients with stage I NSCLC after the first resection is worse for ever smokers than for never smokers. Maeda and colleagues reported 5-year overall survival among 536 never smokers and 831 ever smokers with stage I NSCLC of 92% and 76%, respectively (p<0.001). Similarly, we found that, among all patients who underwent primary resection for stage I adenocarcinoma, 5-year survival was 73% for never smokers and 65% for ever smokers (p = 0.014) (Figure 2). Several factors, including cardiopulmonary comorbidites, different etiologies, and different mutation profiles, may account for the difference in survival between never and ever smokers [2, 4–8]. Samet et al. reported that although exposure to radon, environmental tobacco smoke, and indoor air pollutants have been linked to lung cancer in never-smokers, the majority of never-smokers do not have definite links to such environmental causes [2]. Varghese and colleagues reported a higher frequency of KRAS mutations and a lower frequency of EGFR mutations in smokers than in never-smokers [5, 29]. Given the epidemiologic differences between never smokers and ever smokers, it is noteworthy that the risk of developing SPLC was similar between the two groups.

The vast majority of SPLCs are detected by surveillance scan, rather than by evaluation of symptoms. Bae and colleagues and Rice and colleagues reported that 75% and 82% of SPLCs were asymptomatic and detected by surveillance [11, 13]. In our report, more than 90% of SPLCs were detected by surveillance CT scan for both never and ever smokers. At our institution, the high rate of detection among asymptomatic patients is likely secondary to routine surveillance. Bae et al. also reported 5-year survival rates of 63% and 15%, respectively, for patients who had SPLC diagnosed by surveillance or as a result of symptoms [13]. Battafarano et al. reported 5-year actuarial survival of 42% for stage I patients versus 10% for patients with higher-stage SPLC [14]. These reports support that earlier detection of SPLC by surveillance may result in better outcomes.

Rice and colleagues reported that 63% of patients who developed SPLC (31/49) underwent surgical resection. Mollberg and Ferguson reported a review of current series and found that 52% to 75% of patients with SPLC underwent resection [16]. In our series, 77% of never-smokers (23/30) and 87% of ever-smokers (126/145) underwent surgical resection for SPLC (Table 3). These data suggest that patients often present with localized disease that is amenable to surgical resection.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Second Primary Lung Cancers

| Characteristic | Never-Smokers (N=30) |

Ever-Smokers (N=145) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | |||

| IA | 24 (80) | 106 (73) | 0.8 |

| IB | 2 (7) | 16 (11) | |

| IIA | 0 | 2 (1) | |

| IIB | 1 (3) | 10 (7) | |

| IIIA | 0 | 10 (7) | |

| IIIB | 1 (3) | 0 | |

| IV | 2 (7) | 1 (1) | |

| Location | |||

| Ipsilateral | 14 (47) | 64 (44) | 0.8 |

| Contralateral | 16 (53) | 81 (56) | 0.8 |

| Synchronous lesions | 4 (13) | 4 (3) | 0.01 |

| Right upper lobe | 9 (30)a | 45 (31)a | 0.5 |

| Right middle lobe | 4 (13)a | 6 (4)a | |

| Right lower lobe | 10 (33)a | 40 (28)a | |

| Left upper lobe | 5 (17)a | 35 (24)a | |

| Left lower lobe | 4 (13)a | 23 (16)a | |

| Treatment | |||

| Lobectomy | 3 (10) | 33 (23) | 0.2 |

| Wedge | 16 (53) | 67 (46) | |

| Segmentectomy | 3 (10) | 24 (17) | |

| Pneumonectomy | 1 (3) | 2 (1) | |

| Nonoperative therapy | 7 (23) | 19 (13) |

Data are no. (%).

>100% secondary to patients with synchronous lesions.

Bae et al. reported actuarial 5- and 10-year survival rates of 78% and 40% [13]. Battafarano and colleagues reported a 5-year actuarial survival rate of 33% among 69 patients who underwent resection [14]. Hamaji and colleagues reported actuarial 5- and 10-year survival rates of 61% and 20% among 161 resected patients with SPLC [15]. In a multivariate analysis, they found that tumors >2 cm and number of pack years of smoking were adverse prognostic factors. These studies did not report outcomes based on smoking status. From the date of treatment of SPLC, we found 5-year overall survival rates of 84.7% for never-smokers and 68.0% for ever-smokers (p=0.18) (Figure 3). Whereas smokers experience worse outcomes after treatment of primary lung cancer, the outcomes after treatment of SPLC do not appear to be different on the basis of smoking status. However, if these groups were larger, a difference may exist.

The risk of developing SPLC increases over time regardless of smoking status. Bae and colleagues reported that the cumulative risk of developing SPLC increased from 4.7% at 5 years to 12.6% at 10 years [13]. Rice and colleagues similarly showed an increasing cumulative incidence of SPLC [11]. They compared the development of SPLC in never versus ever smokers. None of the never-smokers in their study (n=44) developed SPLC. In contrast, we found a similar cumulative incidence of SPLC between never smokers and ever smokers (20.3% vs. 18.2%) (Figure 1). Our study cohort included 308 never-smokers whereas theirs had only 44. The small group of patients in their study may account for the difference. Also, postoperative surveillance was performed with radiography, rather than computed tomography scan; therefore; small lesions may have been missed. We believe that our data are more robust and that the incidence of SPLC among never-smokers does increase with time. The results of these reports confirm that all patients remain at risk of developing SPLC and that risk does not decrease with time. Our study adds the finding that the risk of developing SPLC is similar between never- and ever-smokers.

Several important limitations to our study exist. First, our study represents a single-institution experience; therefore, the lack of external validity is a potential problem. Second, even though the data were generated from a prospectively maintained database, our review was retrospective, so some degree of selection bias may have occurred. However, the database is updated on a weekly basis and data managers independently review the records to ensure the data are as accurate as possible. Lastly, the database does not capture patient exposure to second-hand smoke; therefore, the percentage of never-smokers who have had that exposure is not known. An estimated 3000 to 5000 lung cancer deaths occur annually as a result of second-hand smoke [2, 3, 30, 31]. Approximately 160,340 deaths occur each year from lung cancer [1], with 10% to 15% of those among never-smokers; therefore, we estimate that approximately 12% to 31% of never-smokers may have been regularly exposed to second-hand smoke [26]. Despite these limitations, we believe our data provide the best estimates of SPLC in never-smokers.

Although smokers have a greater risk of developing NSCLC than nonsmokers, the risk of developing SPLC after resection of stage I lung cancer is comparable between the two groups. The majority of these second primary cancers are detectable at an early stage that is amenable to surgical resection if surveillance occurs. Postoperative surveillance on an ongoing basis should be recommended for all patients, regardless of smoking status. Owing to the similar risk of developing SPLC between smokers and nonsmokers, we recommend that nonsmokers should undergo a long-term surveillance protocol similar to that for smokers.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748

Footnotes

Oral Presentation: Presented at the 50th Annual Meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Orlando, FL, January 25–29, 2014.

References

- 1.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samet JM, Avila-Tang E, Boffetta P, et al. Lung cancer in never smokers: clinical epidemiology and environmental risk factors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5626–5645. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sisti J, Boffetta P. What proportion of lung cancer in never-smokers can be attributed to known risk factors? Int J Cancer. 2012;131:265–275. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mountzios G, Fouret P, Soria JC. Mechanisms of disease: signal transduction in lung carcinogenesis―a comparison of smokers and never-smokers. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:610–618. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varghese AM, Sima CS, Chaft JE, et al. Lungs don't forget: comparison of the KRAS and EGFR mutation profile and survival of collegiate smokers and never smokers with advanced lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:123–125. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827914ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maeda R, Yoshida J, Ishii G, Hishida T, Nishimura M, Nagai K. The prognostic impact of cigarette smoking on patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:735–742. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318208e963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallo V, Neasham D, Airoldi L, et al. Second-hand smoke, cotinine levels, and risk of circulatory mortality in a large cohort study of never-smokers. Epidemiology. 2010;21:207–214. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c9fdad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang P. Lung cancer in never smokers. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32:10–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1272865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rice D, Kim HW, Sabichi A, et al. The risk of second primary tumors after resection of stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00821-x. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lou F, Huang J, Sima CS, Dycoco J, Rusch V, Bach PB. Patterns of recurrence and second primary lung cancer in early-stage lung cancer survivors followed with routine computed tomography surveillance. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.030. discussion 81–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bae MK, Byun CS, Lee CY, et al. The role of surgical treatment in second primary lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Battafarano RJ, Force SD, Meyers BF, et al. Benefits of resection for metachronous lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamaji M, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, et al. Surgical treatment of metachronous second primary lung cancer after complete resection of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.051. discussion 90–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mollberg NM, Ferguson MK. Postoperative surveillance for non-small cell lung cancer resected with curative intent: developing a patient-centered approach. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:1112–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calman L, Beaver K, Hind D, Lorigan P, Roberts C, Lloyd-Jones M. Survival benefits from follow-up of patients with lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1993–2004. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822b01a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field JK, Smith RA, Aberle DR, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Computed Tomography Screening Workshop 2011 report. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:10–19. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823c58ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martini N, Melamed MR. Multiple primary lung cancers. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;70:606–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chappell R. Competing risk analyses: how are they different and why should you care? Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2127–2129. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, Zhang MJ, Fine J. A proportional hazards regression model for the subdistribution with right-censored and left-truncated competing risks data. Stat Med. 2011;30:1933–1951. doi: 10.1002/sim.4264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Meerbeeck J, Weyler J, Thibaut A, et al. Second primary lung cancer in Flanders: frequency, clinical presentation, treatment and prognosis. Lung Cancer. 1996;15:281–295. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haraguchi S, Koizumi K, Hirata T, et al. Surgical treatment of metachronous nonsmall cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;16:319–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel JD, Bach PB, Kris MG. Lung cancer in US women: a contemporary epidemic. JAMA. 2004;291:1763–1768. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thun MJ, Henley SJ, Burns D, Jemal A, Shanks TG, Calle EE. Lung cancer death rates in lifelong nonsmokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:691–699. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakelee HA, Chang ET, Gomez SL, et al. Lung cancer incidence in never smokers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:472–478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henschke CI, Miettinen OS. Women's susceptibility to tobacco carcinogens. Lung Cancer. 2004;43:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D'Angelo SP, Pietanza MC, Johnson ML, et al. Incidence of EGFR exon 19 deletions and L858R in tumor specimens from men and cigarette smokers with lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2066–2070. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Couraud S, Zalcman G, Milleron B, Morin F, Souquet PJ. Lung cancer in never smokers—a review. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1299–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fontham ET, Correa P, Reynolds P, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and lung cancer in nonsmoking women: a multicenter study. JAMA. 1994;271:1752–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]