Abstract

According to national estimates, obesity prevalence is lower in Asian Americans compared to other racial/ethnic groups, but this low prevalence may be misleading for three reasons. First, a lower body mass index (BMI) cutoff as proposed by the World Health Organization may be more appropriate to use in Asian populations. However, evidence is limited to substantiate the potential costs and burden of adopting these cutoffs. Increasing BMI in Asians (as in other racial/ethnic groups) should be considered across the spectrum of BMI, with a minimum awareness of these lower cutoffs among healthcare researchers. Second, the need for disaggregated data across Asian American subgroups is illustrated by the higher obesity (and diabetes) prevalence estimates observed in South Asian Americans. Third, prevalence of obesity should be placed in the larger context of immigration and globalization through cross-national comparisons and examination of acculturation-related factors. However these types of studies and collection of salient variables are not routinely performed. Data from a metropolitan area where many Asian Americans settle is presented as a case study to illustrate these points. Clear evidence that incorporates these three considerations is necessary for program planning and resource allocation for obesity-related disparities in this rapidly growing and diverse population.

Keywords: Asian Americans, Obesity, Acculturation

Introduction

According to the most recent census data, Asian Americans comprise 5.6% of the U.S. population, and in metropolitan areas such as New York City (NYC), up to 13% of the citywide population (Hoeffel, 2010). Asian Americans were the fastest growing race/ethnic group in the United States in the last ten years, and these numbers will continue to rise in the coming decades. Nationally, Asian Americans will double in population size with a projected increase to more than 43 million by 2050.

New statistics describing the prevalence of obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m2) in the U.S. population were released from the National Center for Health Statistics using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–12 wave. Because an oversample of Asian Americans had been added in that survey wave, obesity prevalence for the Asian American non-institutionalized adult population calculated from measured height and weight values was presented for the first time (10.8) (Ogden et al., 2014). This estimate was lower compared to all other racial/ethnic groups (32.6–47.8). However, as was acknowledged by the study authors, the ‘advantage’ observed between Asian Americans and other groups may be misleading. The purpose of the current commentary is to frame obesity and obesity-related disparities in Asian Americans using existing literature and new data from the NYC adult population.

Modified body mass index (BMI) cutoffs

The use of modified BMI cutoffs has been proposed for Asian populations worldwide by the World Health Organization (WHO), though the broad applicability to all Asian subgroups and to Asians living in America is unknown (Consultation, W.H.O.E., 2004). These modified cutoffs lower the threshold by which an Asian individual is categorized as having a normal BMI, as overweight or as obese (modified BMI cutoffs for Asians: underweight < 18.5 kg/m2 [same as standard], normal 18.5–22.9 kg/m2, overweight 23.0–27.5 kg/m2, obese ≥ 27.5 kg/m2). The rationale behind these modified cutoffs is that Asians tend to have a higher percent body fat for the same BMI compared to whites (Deurenberg et al., 2002). This has been hypothesized to be due to leg length relative to height and/or to smaller body frames — of which Asians tend to have both versus whites (Deurenberg et al., 2002). As stated in the WHO report, one immediate consequence of applying these lower BMI cutoffs across Asian populations would be the increased prevalence of both overweight and obesity, and subsequent increases in healthcare spending and changes to healthcare policy (Consultation, W.H.O.E., 2004). Due to the lack of evidence to warrant such long-term, macro-level consequences, the WHO did not stress formal adoption of these modified cutoffs. Instead, they remind health care practitioners and public health officials that increases in BMI across the entire spectrum of BMI and not obesity per se, pose increased risk of chronic disease-related outcomes.

Since the 2004 WHO report, studies have demonstrated that at lower BMI values, Asian Americans tend to have a higher risk of diabetes and hypertension compared to other race/ethnic groups (Wong et al., 2014). In a pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies, risk of mortality increased with BMI values that were 30 kg/m2 or greater in Asian Americans, with authors concluding that modified cutoffs may not be warranted in Asian American populations (Park et al., 2014). A pooled analysis across 20 prospective studies (the Asia Cohort Consortium) demonstrated that there was increased risk of cardiovascular disease at BMI values of 25 kg/m2 in East Asians (Chinese, Japanese, Korean), but not in South Asians (Indians, Bangladeshi) (Chen et al., 2013; Zheng et al., 2011). Despite the lack of a formal recommendation and given a lack of evidence to the contrary, study authors have incorporated these modified cutoffs into their analyses of Asian Americans to highlight potential disparities across Asian subgroups and race/ethnicity (Jih et al., 2014; Maxwell et al., 2012). Additional research is necessary to determine whether the use of these cutoffs in Asian American populations is useful in predicting future morbidity and mortality.

Differences across Asian subgroups

The differential findings across Asians from East compared to South Asian countries from Chen et al. (2013) underscore another aspect of obesity in Asian Americans that warrants discussion. Asian Americans are often grouped together into one category despite tremendous diversity, including differences in socioeconomic status, access to resources, migration patterns, and immigration histories. Improvements to data collection efforts to reflect and capture subgroup differences have been outlined and encouraged (Islam et al., 2010). Even broad categorizations differentiating South, East, and Southeast Asian are preferable to none at all. As discussed above, there is potential for differential risk at various BMI cutoffs in East vs. South Asians. The high, and increasing prevalence of diabetes in South Asians specifically is also troubling (Gupta et al., 2011; Shih et al., 2014). Without data on Asian American subgroups, health planning and decision-making around obesity and diabetes are hampered.

Importance of immigration patterns and the global context

Following changes to American immigration policy in 1965, large numbers of Asians began to immigrate to the U.S. These initial immigrants and their offspring are now reaching older ages, placing them at higher risk for chronic disease morbidity and mortality. Prior literature has demonstrated generational status to be positively associated with obesity in Asian Americans in both adolescents and adults, and in some Asian subgroups (Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese) (Bates et al., 2008; Popkin and Udry, 1998). Further, characteristics of Asian immigrants who arrived just following 1965 compared to those arriving in the last decade differ, particularly with regard to socioeconomic status, an important predictor of health. A report using data from the 2006 American Community Survey estimated that 32% of Asian immigrants arriving prior to 1980 were low-income (below twice the federal poverty threshold), compared to 51% of Asian immigrants arriving after 2000 (Asian American Federation, 2008). Thus generational status and other markers of the immigration experience (U.S.-born vs. foreign-born, dietary changes, access to healthcare) are critical for further subdividing Asian Americans to accurately describe the burden of obesity in this group. Lastly, what is particularly salient in understanding obesity trends in Asian Americans is to place their experience within the rich context of globalization in countries such as India and China where diabetes is increasing rapidly (Hu, 2011) The impact of globalization and the immigration patterns on both those in Asia and new Asian American immigrants, and comparisons across these groups should be explored.

Case study using New York City data

The majority of the Asian American population is concentrated in major metropolitan cities and comprises a substantial proportion of the city populations (Hoeffel, 2010); therefore, datasets collected in urban areas often include Asian Americans in numbers substantial enough for statistical use. These analyses were performed with the hope that estimates of health indicators in these areas may inform program planning and resource allocation in other, non-urban areas.

Methods and statistical analysis

Data were from the Community Health Survey (CHS), a random-digit-dial, cross-sectional survey conducted annually since 2002 by the NYC Health Department. The CHS includes self-reported health data on approximately 9000 participants each year and is weighted to be representative of NYC as a whole; the datasets and a data query interface (EpiQuery) are publicly available on the website (The New York City Community Health Survey, 2014). Race/ethnicity was assessed using two questions on Hispanic origin and race group, and was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic and non-Hispanic Asian (hereafter referred to as ‘white’, ‘bl ‘, or ack ‘Asian American’). The sample sizes of Asian Americans and whites in the CHS 2012 were n = 783, n = 3525, and in the CHS 2002 were n = 488, n = 3754, respectively.

BMI was calculated from self-reported height and weight. For whites, the standard obesity cutoff of 30 kg/m2 was used; for Asian Americans, both the standard and the WHO modified cutoff of 27.5 kg/m2 were assessed. Nativity was defined as self-report of being born in the U.S. or elsewhere. Puerto Ricans and those born in U.S. territories were defined as being foreign born. Asian ancestry was asked of all adults who reported Asian race/ethnicity and determined using the question, “Please tell me which group best represents your Asian heritage or ancestry.” with the following answer choices: “Chinese, Asian Indian, Filipino, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, other”. These were further collapsed into East Asian (Chinese, Japanese, Korean); Southeast Asian (Filipino, Vietnamese) and South Asian (Asian Indian).

All analyses were age-standardized to the 2000 U.S. Standard population. All results were weighted to be representative of the NYC non-institutionalized, adult population. The following values were pulled from the EpiQuery system: 1) 2012 obesity prevalence estimates, overall, by race/ethnicity and in Asian Americans, by nativity; and 2) 2002 obesity prevalence estimates by race/ethnicity. Obesity prevalence estimates in Asian Americans using modified BMI cutoffs and stratified by Asian ancestry were run in CHS 2012. Prevalence estimates are presented with an accompanying 95% confidence interval (CI) in parentheses; non-overlapping CIs may be considered statistically different. Change in obesity prevalence from 2002 to 2012 was estimated and tested using t-tests for proportions. The linear trend p-value for change in obesity over time was compared across cross-sectional CHS years (2002 through 2012) using orthogonal trend tests. SUDAAN software (version 10.0; Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) was used for all analysis.

Results

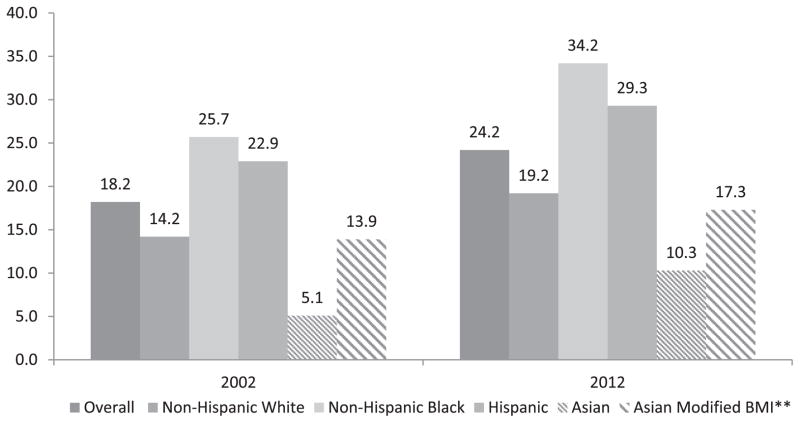

In the NYC adult population, the prevalence of obesity was 24.2 (22.8, 25.5) (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2012) and similar to the national data, differences exist by race/ethnicity. The age-standardized prevalence was 19.2 (17.1, 21.6) in whites, 34.2 (31.1, 37.4) in blacks, 29.3 (26.6, 32.2) in Hispanics, and 10.3 (7.6, 13.7) in Asian Americans (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2012). If however, the modified cutoff for obesity is applied for Asian Americans (BMI ≥ 27.5 kg/m2), the age-standardized prevalence of obesity increases to 17.3 (14.1, 21.2; Fig. 1). The prevalence of obesity in NYC when stratified by Asian subgroup was 8.1 (5.6, 11.6) in East Asians, 12.9 (7.6, 20.9) in South Asians, and 2.3 (0.5, 9.5) in Southeast Asians; with modified cutoffs: 14.1 (10.7, 18.4) in East Asians, 19.7 (13.5, 27.8) in South Asians and 19.0 (8.0, 38.7) in Southeast Asians. While generational status was not available in the CHS 2012, obesity prevalence stratified by nativity was 10.2 (7.4, 13.8) in the foreign-born, but 18.8 (9.6, 33.7) in the U.S.-born, though the latter may be unreliable owing to small sample size (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2012). In terms of trends, the age-standardized prevalence of obesity in 2002 was 5.1 (3.1, 8.4) in Asian Americans (14.2 [12.9, 15.7] in whites) (New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2002). The Asian American population experienced an increase of 102% in obesity prevalence (p = 0.01) between 2002 and 2012, while only a 35% (p < 0.01) increase was observed in whites. Linear trends were significant over time in analyses which incorporated data from multiple years of the CHS; these increases were observed in Asian Americans (p = 0.03) and in whites (p < 0.001) when using the standard BMI cutoffs, but not when modified BMI cutoffs were used in Asian Americans (p = 0.08).

Fig. 1.

Age-standardized obesity prevalence in New York City, Community Health Survey 2002, 2012. Displays obesity prevalence estimates stratified by race/ethnicity in two time periods, and when applying the standard and modified body mass index cutoffs for Asians. Prevalence has increased over time in all race/ethnic groups, and when using the modified cutoffs for Asians, the prevalence of obesity increases. **Modified body mass index cutoffs for Asians: underweight < 18.5 kg/m2 [same], normal 18.5 to 22.9 kg/m2, overweight 23.0 to 27.5 kg/m2, obese ≥ 27.5 kg/m2.

Conclusions

The current commentary outlines three areas where more information is needed to understand the burden of obesity in the Asian American population: 1) the utility of modified BMI cutoffs for routine use and verification in prospective data, 2) the importance of data collection efforts that not only include and/or oversample Asian Americans, but further differentiate between Asian subgroups and 3) the placement of Asian Americans into a global/immigration context through cross-national comparisons and the inclusion of questions on generational status and acculturation-related factors. To expand upon the second point regarding the collection of data disaggregated by Asian American subgroup, while sample sizes may be limited for analysis in any given year of a cross-sectional, population-based survey, repeat collection over time would allow for analysis of combined years to highlight emerging health disparities in these subgroups (Islam et al., 2010). This approach has been previously employed by others including Shih et al., using data from the Los Angeles County Health Survey (Shih et al., 2014) and Islam et al., using data from the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) Risk Factor Survey (Islam et al., 2013).

Several studies have illustrated that cardiovascular disease and mortality disparities exist for Asian American populations (Islam et al., 2013; Freeman et al., 2011; Ursua et al., 2014), yet the underlying causes for these disparities remain poorly understood. There are clear implementation gaps in adapting evidence-based public health interventions for culturally diverse populations. A lack of accurate data, particularly data disaggregated by ethnic subgroup, obscures baseline health needs and prevents researchers from fully appreciating the magnitude and nature of health disparities in Asian Americans (Lee et al., 2013). Disaggregated data collection and using measures that are relevant to Asian Americans can serve as an important step towards addressing the knowledge gaps in obesity and chronic disease prevention for this population.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: The authors would like to thank Tali Elfassy and Melanie Firestone for their assistance with data processing.

Funding sources: This publication is supported by grant numbers P60MD000538 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, U48DP005008 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and UL1TR000067 from NCATS/NIH. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH and CDC.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Bates LM, et al. Immigration and generational trends in body mass index and obesity in the United States: results of the National Latino and Asian American Survey, 2002–2003. Am J Public Health. 2008;98 (1):70–77. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, et al. Association between body mass index and cardiovascular disease mortality in east Asians and south Asians: pooled analysis of prospective data from the Asia Cohort Consortium. BMJ. 2013;347:f5446. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consultation WHOE. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363 (9403):157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deurenberg P, Deurenberg-Yap M, Guricci S. Asians are different from Caucasians and from each other in their body mass index/body fat per cent relationship. Obes Rev. 2002;3 (3):141–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2002.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman K, et al. Mortality trends and disparities among racial/ethnic and sex subgroups in New York City, 1990 to 2000. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13 (3):546–554. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta LS, et al. Prevalence of diabetes in New York City, 2002–2008: comparing foreign-born South Asians and other Asians with U.S.-born whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 (8):1791–1793. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffel EM, et al. [Accessed Jan 9, 2014];census briefs. 2010 https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf (Issued March 2012.

- Hu FB. Globalization of diabetes: the role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34 (6):1249–1257. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam NS, et al. Methodological issues in the collection, analysis, and reporting of granular data in Asian American populations: historical challenges and potential solutions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21 (4):1354–1381. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam NS, et al. Diabetes and associated risk factors among Asian American subgroups in New York City. Diabetes Care. 2013;36 (1):e5. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jih J, et al. Using appropriate body mass index cut points for overweight and obesity among Asian Americans. Prev Med. 2014;65C:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Fitzpatrick JJ, Baik SY. Why isn’t evidence based practice improving health care for minorities in the United States? Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26 (4):263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell AE, et al. Health risk behaviors among five Asian American subgroups in California: identifying intervention priorities. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14 (5):890–894. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9552-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. [Accessed on July 7, 2014];EpiQuery: NYC Interactive Health Data System — Community Health Survey. 2002 http://nyc.gov/health/epiquery.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. [Accessed on July 7, 2014];Epiquery: NYC Interactive Health Data System — Community Health Survey. 2012 http://nyc.gov/health/epiquery.

- Ogden CL, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311 (8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, et al. Body mass index and risk of death in Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2014;104 (3):520–525. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM, Udry JR. Adolescent obesity increases significantly in second and third generation U.S. immigrants: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Nutr. 1998;128 (4):701–706. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih M, et al. Stemming the tide: rising diabetes prevalence and ethnic subgroup variation among Asians in Los Angeles County. Prev Med. 2014;63:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Accessed Jan 9, 2014];The New York City Community Health Survey. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/survey/survey.shtml.

- Ursua R, et al. Awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among Filipino immigrants. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29 (3):455–462. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2629-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong RJ, et al. Ethnic disparities in the association of body mass index with the risk of hypertension and diabetes. J Community Health. 2014;39 (3):437–445. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asian American Federation. [Accessed on July 7, 2014];Working but poor: Asian American poverty in New York City. 2008n http://www.aafny.org/doc/WorkingButPoor.pdfOctober.

- Zheng W, et al. Association between body-mass index and risk of death in more than 1 million Asians. N Engl J Med. 2011;364 (8):719–729. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]