Abstract

In the context of a global artificial photosynthesis (GAP) project, we review our current work on nature's water splitting catalyst. In a recent report (Cox et al. 2014 Science 345, 804–808 (doi:10.1126/science.1254910)), we showed that the catalyst—a Mn4O5Ca cofactor—converts into an ‘activated’ form immediately prior to the O–O bond formation step. This activated state, which represents an all MnIV complex, is similar to the structure observed by X-ray crystallography but requires the coordination of an additional water molecule. Such a structure locates two oxygens, both derived from water, in close proximity, which probably come together to form the product O2 molecule. We speculate that formation of the activated catalyst state requires inherent structural flexibility. These features represent new design criteria for the development of biomimetic and bioinspired model systems for water splitting catalysts using first-row transition metals with the aim of delivering globally deployable artificial photosynthesis technologies.

Keywords: photosynthesis, photosystem II, water splitting, H2 production

1. The need for a global project on artificial photosynthesis

The world's power supply is based predominantly on the use of non-renewable energy resources such as oil, coal and natural gas. These geological resources have been accumulated over millions of years from photosynthetic activity and thus constitute ‘stored solar energy’. The steep rise in energy consumption over the last century has led to an inevitable shortage of these valuable resources with the economic, social and political consequences already felt today. Human population and economic growth, particularly in fast-developing countries, will lead to a further increase in energy demand. Furthermore, the burning of carbon-rich fuels has increased CO2 concentration in the atmosphere. This increase is associated with anthropogenic climate changes, with projected adverse effects for our planet and human society (http://www.ipcc.ch/report). It is therefore one of the great challenges of mankind to identify and develop alternative sustainable energy sources [1–5].

Society's energy needs come in many forms. The dominant fraction is related to liquid fuels used for example in transportation (approx. 80%); whereas electrical energy only accounts for a small part of our energy consumption (approx. 20%) (https://www.bdew.de/internet.nsf/id/DE_Energiedaten). This is particularly problematic as there currently exists no satisfactory method which would be able to supply our demand for renewable liquid fuels. One possible solution would be to generate electricity using alternative, clean physical energy conversion technologies such as photovoltaics, wind turbines and hydropower and subsequently convert it into a chemical storage form. Such technologies already represent an increasing share of electrical energy generation worldwide (in Germany in 2013 16%) (https://www.bdew.de/internet.nsf/id/DE_Energiedaten). The question that then arises is what represents the best feedstock for a synthetic, renewable fuel. Here, biology provides an answer: photosynthesis uses water, a cheap, non-toxic, abundant material. Thus, in an idealized scenario ‘clean’ electricity would be used in the electrolysis of water, generating hydrogen (H2), as a fuel [6]. Hydrogen itself is a very important base chemical and can be converted to many other important energy-rich materials for storage and/or transport, e.g. with CO2 to methane, methanol or formic acid, and with molecular nitrogen to ammonia (figure 1).

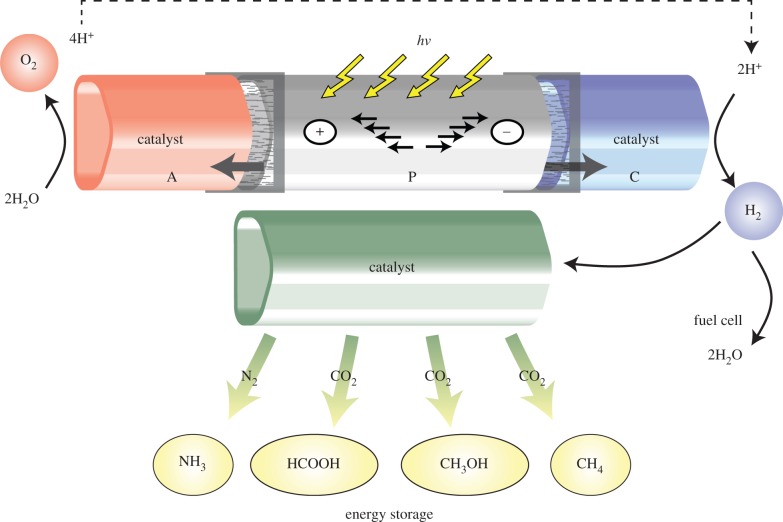

Figure 1.

Biomimetic device showing light-induced charge separation in a photo(electro)catalyst P, transport of redox equivalents to a water splitting catalyst (A, anode) and to a hydrogen-producing catalyst (C, cathode). The generated primary ‘solar fuel’ is dihydrogen. This can be used directly, e.g. in fuel cells to generate electricity or burned in combustion engines, or can be converted for storage, transport or other uses. The examples are reactions with carbon dioxide to yield formic acid, methanol or methane and ammonia production with nitrogen (e.g. for fertilizers, agriculture). These reactions also require efficient catalysts.

A simple calculation shows that the yearly energy needs of a single person can be met by decomposition of 12 000 l of water, i.e. the contents of a small water pool (4 × 3 × 1 m). In addition, such a scenario eliminates the need for an independent power supplier, allowing energy production at the site of use [7], reducing transportation losses. A bottleneck though for such a ‘hydrogen economy’ blueprint is the relatively high price of the hydrogen produced. The high cost is derived from the materials used currently in commercially viable electrolysers: noble metals such as platinum or precious metal oxides (Ru and Ir oxides). These need to be replaced by less expensive metal catalysts before this model for the hydrogen economy becomes viable.

The generation of H2 from water requires two catalytic steps: (i) the oxidation of two water molecules into O2 and protons and (ii) the subsequent reduction of protons to molecular H2. For proton reduction interesting approaches already exist (e.g. based on biomimetic catalysts from hydrogenase research) [8] that are close to enabling feasible commercial/industrial applications [9]. By contrast, there exists no completely satisfactory water oxidation catalyst. First-row transition metal based materials used for this reaction display typically a limited stability and durability (low turnover number, TON) or have an intrinsically low turnover frequency (TOF), precluding their wide range application. Another problem is often the excessive voltages needed to drive such catalysts (overpotential), which are due to the lack of suitable interfaces between the catalysts and the photo-active semiconductors.

Clearly renewed public investment should be targeted towards the scientific, technological and economic challenges needed to initiate the energy transition described above, e.g. the ‘Energiewende’ policy adopted by the current German government. The central discipline in this endeavour is chemical catalysis in all its facets, allowing energy to be efficiently used, stored, transported and interconverted. In this endeavour much can be learned from nature, which has developed many highly efficient metallo-enzymes [10] for the chemical conversion of small molecules with high TONs, long lifetimes and low overpotentials, and which even have built-in protection and repair mechanisms.

To solve the energy problems of the future requires initiatives such as the Global Artificial Photosynthesis (GAP) project [5], which bring together the efforts of many researchers across a wide range of scientific disciplines. Ideally, technologies that use nature as a blueprint, such as photosynthesis, should be considered part of the common heritage of mankind. We should aim that such technologies are affordable and accessible throughout the world with maximum benefit to all. We endorse the spirit of the GAP project: ‘Our goal is to work cooperatively and with respect for basic ethical principles to produce the scientific breakthroughs that allow development and deployment of an affordable, equitably accessed, economically and environmentally sustainable, non-polluting global energy and food system that also contributes positively to our biosphere’, as discussed at the Chicheley Hall conference in July 2014.

2. Design strategies for artificial photosynthesis, learning from nature

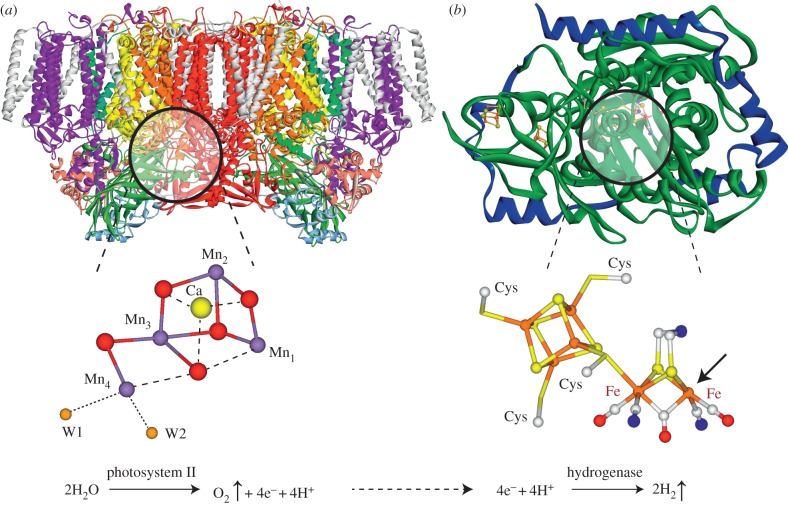

The term ‘artificial photosynthesis’ or equally ‘synthetic photosynthesis’ describes technologies that attempt to capture the energy of sunlight to make energy-rich molecules, i.e. ‘solar fuels’. This relies on the thesis that chemical bonds allow energy to be efficiently stored. This is essentially what nature does. It performs a photocatalytic water oxidation reaction which is coupled to carbon dioxide fixation (CO2 reduction). In oxygenic photosynthesis, light-induced water oxidation occurs in a biological supercomplex, called photosystem II (PSII) that is found in all green plants, algae and cyanobacteria. It harbours a protein-embedded oxygen-bridged Mn4Ca cluster with four bound water-derived ligands [11], as shown in figure 2. This cluster, called the water oxidizing complex (WOC) or oxygen evolving complex (OEC), is coupled to a pigment–protein reaction centre, which successively extracts electrons from it. After four such extractions, the complex splits water into protons and molecular oxygen, which is released as by-product, returning to its resting state (for reviews, see [13–16]). Protons generated via this process could, in principle, be used by another enzyme found in many green algae and bacteria, hydrogenase, which catalyses the conversion of protons to molecular hydrogen (for a recent review, see [8]). In figure 2 next to PSII, the structure of an [FeFe] hydrogenase is also depicted. The active site of this hydrogenase is a six-iron cluster, made up from a classical [4Fe–4S] cubane linked to a di-iron complex that carries uncommon ligands (3 CO, 2 CN−, azadithiolate) [8]. Under certain metabolic conditions, this enzyme is activated and produces hydrogen from excess protons. Other types of hydrogenases are known that harbour a different binuclear metal cluster ([NiFe] hydrogenases) that converts H2 into protons and electrons, thereby generating energy for the organism [8,17,18]. In principle, both types of hydrogenases catalyse both reactions, dihydrogen splitting and production, albeit with different rates.

Figure 2.

Light-induced water splitting into molecular oxygen and hydrogen by the enzymes PSII and [FeFe] hydrogenase. This cascade reaction (water oxidation and subsequent proton reduction) is for example exploited by green algae, e.g. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. The structure of the proteins ((a) PDB 3ARC [11], (b) PDB 1HFE [12]) and the structure of the active sites are shown (see text for details).

The efficient coupling of these two biological processes, water oxidation and hydrogen production (shown in figure 2), is currently being investigated in many laboratories aiming at producing (bio)hydrogen [19–23]. An interesting feature of the enzymes is the high turnover rate, which is about 500 s−1 for the WOC and up to 10 000 s−1 for the hydrogenase [24]. Unfortunately, both enzymes suffer from limited stability: the WOC has a half-life of only 30 min in average light under working conditions [25] and the [FeFe] hydrogenase is very sensitive to oxygen [26,27]; in the living cell, protection and repair mechanisms exist that efficiently resynthesize and replace the damaged parts of the enzymes. Among the [NiFe] hydrogenases, there is also a class of oxygen-tolerant enzymes [28–32].

An understanding of the principles and mechanisms of water oxidation and hydrogen conversion in nature would allow us to better design artificial systems capable of (bio)hydrogen production, be they biological photosynthetic organisms or purely synthetic systems, such as the hypothetical device in figure 1. For this latter system, the ultimate aim is to synthesize new catalysts for large-scale water splitting, hydrogen production and energy storage in chemical compounds. Such compounds may also be of importance for a future sustainable energy economy. In this short review, the current knowledge about the enzyme water oxidase (PSII) is described as an example. It is not intended to describe in depth the biological system but instead focus on the active metal cluster, and the recent insight gained about its function by structural, spectroscopic and theoretical results. Design criteria for the construction of respective biomimetic and bioinspired model systems for water splitting are discussed. We note that the reversible conversion of protons to molecular hydrogen is described in recent reviews (e.g. [8]).

3. Nature's water splitting catalyst

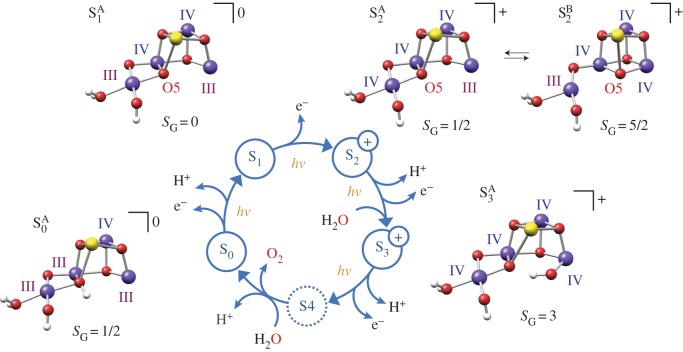

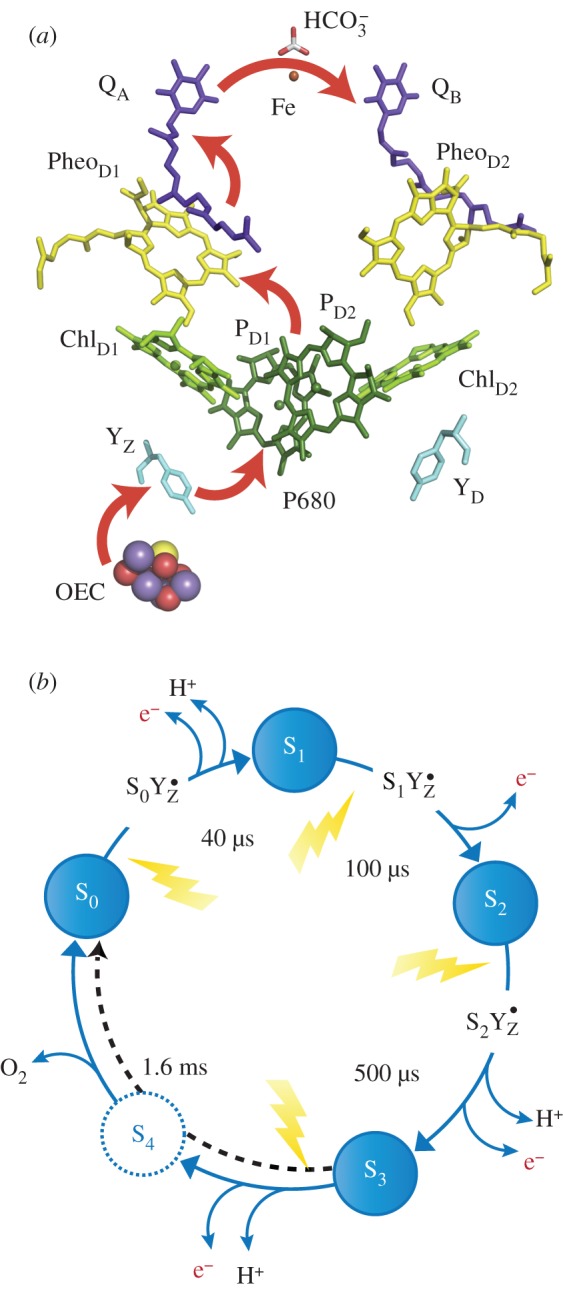

Nature's water oxidizing catalyst represents a penta-oxygen tetramanganese–calcium cofactor (Mn4O5Ca) [11,13,16] (figure 2). Its catalytic cycle comprises five distinct redox intermediates, the Sn states, where the subscript indicates the number of stored oxidizing equivalents (n = 0–4) required to oxidize two water molecules and release dioxygen [33] (figure 3b). It is embedded in a unique pigment–protein supercomplex, PSII, which acts as a photosensitizer. Outer light harvesting complexes absorb visible light and funnel excitation energy to the reaction centre of PSII, where charge separation takes place. The reaction centre comprises chlorophyll, pheophytin and quinone molecules arranged about a twofold symmetry axis [35]. The radical cation generated upon charge separation, termed the primary oxidant (P680•+), is predominately associated with the chlorophylls PD1 and PD2 (figure 3a). The photochemically generated electron is passed in succession to the pheophytin (PheoD1) and subsequently to the bound plastoquinone (QA), increasing the electron–hole distance, thus stabilizing the charge separated state. Reaction centre photochemistry occurs on a picosecond to nanosecond time scale [35].

Figure 3.

(a) Electron transport chain of PSII linking reaction centre photochemistry to the site of water splitting catalysis. (b) The catalytic (Kok) [33] cycle of the cofactor showing the sequence of electron and proton withdrawals and the time constant for each transition [34].

Subsequently, the electron is passed from QA to a second plastoquinone (QB), which acts as a mobile charge carrier. It accepts two electrons and two protons, before leaving its protein pocket to be exchanged with a new plastoquinone. In this way, electrons are passed to the next photosynthetic supercomplex, the cytochrome b6f complex.

The photogenerated cation P680•+ is coupled to the Mn4O5Ca cofactor via an intermediary redox-active tyrosine residue YZ, which acts as a single-electron gate (figure 3a). Initial electron (hole) transfer between P680•+ and YZ occurs on a nanosecond time scale, whereas the subsequent electron (hole) transfer between YZ• and the Mn4O5Ca cofactor occurs on a microsecond to millisecond time scale, depending on the intermediate (S-state). Fast reversible oxidation of YZ is a property of the protein pocket. A nearby histidine residue acts as an intermolecular base, stabilizing the deprotonated (Tyr-O•) state, while structured waters (bound to the Ca2+ ion) act to tune its redox potential [11,36]. After four charge separation events, the transiently formed S3YZ• state [S4] rapidly decays to the S0 state with the concomitant release of molecular triplet dioxygen and probably the rebinding of one substrate water molecule [37,38].

4. Key design features of the oxygen evolving complex

Nature's ‘photosynthetic cell’—the water splitting cofactor coupled to the pigment–protein reaction centre photosynthesizer—has a number of unique design features, including the following.

(i) Light-induced single-electron transfer on a picosecond time scale coupled to a much slower millisecond four-electron process, the oxidation of two water molecules to molecular oxygen.

(ii) The temporary storage of oxidation equivalents required for this reaction, i.e. transient oxidation of the Mn ions.

(iii) Decoupling of O–O bond formation and proton release. Protons are released continuously throughout the S-state cycle [34], whereas the O–O bond forms in a single concerted step. Cofactor oxidation coupled with deprotonation (charge balancing/redox levelling) ensures that the redox potential of each of the four-electron withdrawal steps is similar, allowing all transitions to be driven by a single oxidant, P680, i.e. it lowers the overpotential needed to drive catalysis.

(iv) Efficient interfacing of the catalyst and the photosensitizer via a redox-active tyrosine Yz.

(v) Regulated substrate (water) delivery and product release (O2, H+) via protein channels.

(vi) Protection and repair mechanisms that limit oxidative damage of the protein pocket and replace the protein scaffold every 30 min under full sunlight [39]. It is noted that the water splitting catalyst binds to the protein and assembles spontaneously from free Mn2+ and Ca2+ in solution under visible light, a process called photoactivation [40].

5. The structure of the catalyst

The arrangement of the five metal ions and the connectivity of the cofactor (oxo bridges) have been resolved by conventional X-ray crystallography using synchrotron radiation (XRD) [11] supplemented by femtosecond X-ray crystallography using a free electron laser (XFEL) [41]. The structure represents a distorted chair where the back of the chair is defined by a plane containing Mn1, Mn3 and Mn4. A second plane containing the Ca ion and Mn2 defines the front of the chair. The Mn–Mn distances seen in the XRD structure are systematically longer than those seen in extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and in model complexes [42–46]. This is not the case for the XFEL structure, where the same Mn–Mn distances as seen in EXAFS are observed. The longer Mn–Mn distances in the XRD structure are thought to reflect reduction [47–49] of the Mn ions, and as such the XFEL structure is considered more reliable.

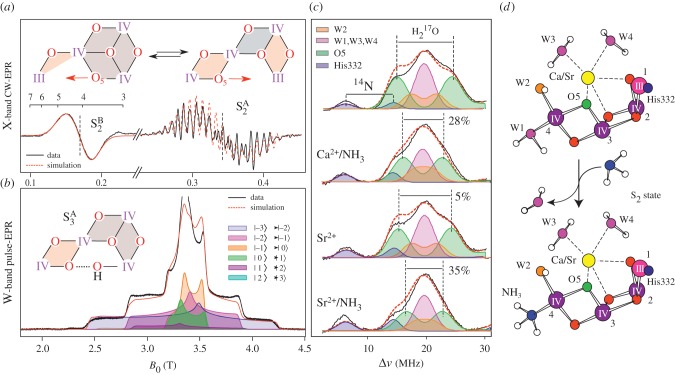

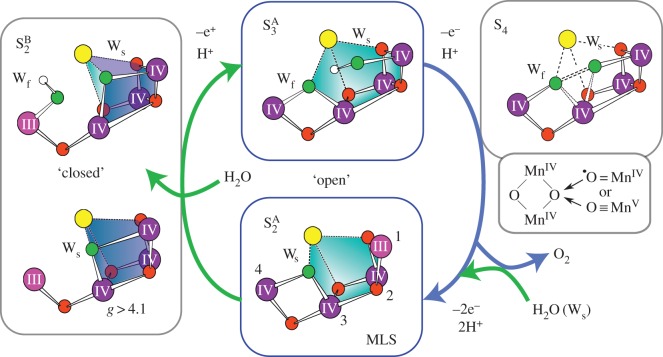

Our own work has concentrated on the development of methods for calculation of spectroscopic observables from magnetic resonance and X-ray spectroscopies, to further refine structural models of the cofactor and precisely describe the electronic structure of the catalyst in all catalytic states [50,51]. Our starting point was the structure of the cofactor in the S2 state, for which extensive spectroscopic data exist, in which the net oxidation state of the cofactor is MnIIIMnIV3. Theoretical modelling has shown that the cofactor can adopt two interconvertible core topologies in this state [52–54], an open cubane (S2A) and a closed cubane motif (S2B) (figure 4). The S2A form is slightly lower in energy by ca 1 kcal mol−1 and displays an electronic ground state of spin SG = 1/2. In this structure, the only MnIII ion of the cofactor, which is five-coordinate, is found within the cuboidal unit (Mn1, figure 5a). In the S2B form, the cofactor instead displays an electronic ground state of spin SG = 5/2. In this structure, the five-coordinate MnIII ion is now located at the terminal Mn4 (figure 5a) [52–54]. Movement of the MnIII site is thus coupled to a reorganization of the core connectivity of the cofactor, involving the movement of a single μ-oxo bridge (O5) (figures 4 and 5a). In the open structure (S2A), O5 represents a bis-μ-oxo linkage between Mn3 and Mn4 (open form, S2A), whereas in the closed structure it becomes (S2A) a vertex of the heterobimetallic cubane unit. These two structures show a one-to-one correspondence with the two well-known electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signals for the S2 state, the multiline (S = 1/2) and g4 (S = 5/2) signals (figure 5a) [52].

Figure 4.

Models for each S state of the Kok cycle, showing the optimized geometry, protonation pattern and Mn oxidation states of the inorganic core, modified from Krewald et al. [55]. The cofactor exists in two forms in the S2 state, an open cubane (S2A, SG = 1/2) and a closed cubane (S2B, SG = 5/2) structure which differ in their core connectivity by the reorganization of O5 [52].

Figure 5.

(a) CW-EPR data of the two forms of the S2 state (S2A and S2B) modified from Cox et al. [13]. (b) High field (W-band) data of the S3 state consistent with an open S3A type structure, modified from Cox et al. [56]. (c) 17O-EDNMR data of exchangeable oxygen sites of the Mn4O5Ca cofactor, modified from Lohmiller et al. [57]. The splitting of the largest doublet (green, O5) is sensitive to both Ca2+/Sr2+ replacement and W1/NH3 exchange. (d) Replacement of W1 by NH3. Also shown are the three different sites where 17O labelled water is taken up by the cofactor: (i) as a ligand to the Ca2+ ion, (ii) as a ligand to the outer Mn4 ion and (iii) as a μ-oxo bridge (O5) [58].

Recent multifrequency EPR measurements from our laboratory have now resolved the net oxidation state of the S3 state (figure 5b). We find the net oxidation state of the cofactor is MnIV4 [56], categorically ruling out a ligand centred oxidation during the S2–S3 transition as has been proposed in the literature. Concomitant double resonance data suggest that the cofactor adopts a single configuration (unlike the S2 state), which is best described as an open cubane (S3A) structure (figures 4 and 5b). Importantly, these results require that all four Mn ions are six coordinate in the S3 state. This constraint necessitates the binding of a new water molecule to the open coordination site of the cofactor in the form of a hydroxide (figures 4 and 5b) [56,59]. Further evidence for water binding during the S2–S3 transition comes from work of the Noguchi laboratory [60]; their Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic data suggest that the solvation of the cluster increases during the S2–S3 transition. Interpretations of X-ray absorption near-edge structure data of the S2–S3 state are also consistent with a water binding event, where the absence of a large edge shift may reflect the five-coordinate MnIII ion of the S2 state becoming six coordinate in the S3 state [61].

From this starting point, i.e. an understanding of the atomic structure of the S2 and S3 states that includes assignments of the energetically most favourable and spectroscopically consistent protonation states of all titratable ligands [55], we recently extended our spectroscopy-oriented theoretical modelling to the S0 and S1 states. The guiding principle for selecting the best models was again maximal consistency with experimental observables, including spin states (SG = 1/2 for S0 and SG = 0 for S1) [56,62,63], Mn hyperfine couplings, metal–metal distances from EXAFS and profiles of Mn K-pre-edge X-ray absorption spectra [55]. Figure 4 summarizes the results of this effort, showing the cofactor geometry, protonation states of titratable groups and individual Mn oxidation states for all spectroscopically consistent S-states models of the Kok cycle.

6. The substrate (water) molecules of the oxygen evolving complex

Experiments performed with isotopically labelled water (H217O/ H218O) provide a means to identify the two substrate binding sites of the water oxidizing cofactor. Earlier membrane-inlet mass spectrometry (MIMS) results [64], which monitor the uptake of H218O into the product O2 molecule, have demonstrated that the complex contains two chemically different substrate sites: an early (Ws) and late (Wf) binding substrate site, both of which exchange with bulk water in all catalytic states (S-states) [65–67]. Owing to the relatively slow rate of exchange of Ws (≈1 s−1), and its dependence on the oxidation state of the Mn tetramer, Ws is usually considered to be an oxygen ligand of one of the Mn ions [38,67]. By using water labelled with the magnetic isotope (17O, I = 5/2), the same substrate binding site (Ws) can be characterized spectroscopically, using the EPR technique ELDOR-detected NMR (EDNMR) [13,58,68]. These measurements identify a unique, exchangeable μ-oxo bridge as a potential candidate for Ws and the identity of the exchangeable μ-oxo bridge has been inferred from small site perturbations of the cofactor (figure 5c).

Ammonia, a substrate water analogue, is known to bind to the water oxidizing cofactor in the S2 state [69,70]. Its binding mode was recently determined as a terminal ligand to the Mn4 ion, replacing the water ligand W1 [71,72]. Such a binding motif readily explains the observed hyperfine and quadrupole couplings; the asymmetric quadrupole coupling is a property of the H-bonding network of the W1/NH3 site (Asp61) [57,72]. W1 displacement as opposed to other binding modes (μ-oxo bridge displacement) is also preferred based on energetic considerations and an analysis of available vibrational data [71–73]. In samples where NH3 is added, the hyperfine coupling of the exchangeable μ-oxo bridge is strongly perturbed (ca 30%) [57,72]. This result is readily understood as due to a trans effect: the W1 ligand is trans to the O5 bridge. Displacement of W1 by NH3 elongates the O5–Mn4 distance perturbing the observed hyperfine coupling (figure 5c,d) [71].

The assignment that the exchangeable μ-oxo bridge is O5 is further supported by measurements on PSII, where the Ca2+ ion is biosynthetically replaced with Sr2+ [57]. In such samples, the hyperfine coupling of the exchangeable μ-oxo bridge is perturbed (ca 5%, figure 5c). As O5 is a ligand to the Ca2+/Sr2+ site this result is again easily understood. Furthermore, in samples where the Ca2+ is replaced by Sr2+ and NH3 is bound to the cofactor, an additive effect is seen on the exchangeable μ-oxo bridge hyperfine coupling (ca 35%) [57], again consistent with the notion that O5 represents the exchangeable μ-oxo bridge (figure 5c).

The above results on Ca2+/Sr2+ exchange point to O5 representing Ws. This hypothesis comes from correlation to MIMS results which show that Ca2+/Sr2+ replacement perturbs the rate at which Ws exchanges with bulk water [38,67,74]. As Ca2+/Sr2+ replacement similarly affects the electronic properties of O5 (but no other exchangeable oxygen ligand) [57], this result can again be easily understood. We note that the fast rate of exchange of O5 when compared with that of μ-oxo bridges in simple synthetic model systems is likely due to the unusual flexibility of its metal coordination (figures 4–6) [52,53].

Figure 6.

The reaction cycle of the Mn4O5Ca cofactor. In the resting states (S0, S1, S2A), the cofactor represents an ‘open’ cubane structure with an open coordination site for substrate binding. In the activated states (S3 and possibly S4), the structure also resembles an ‘open’ cubane but now the open coordination site is occupied by a hydroxide ligand. Structural flexibility in S2 (S2A, S2B) is hypothesized to be critical for the insertion of this water-derived ligand and formation of an activated S3 state. The O–O bond may then presumably form between the flexible µ-oxo bridge and the inserted (proximal) water-derived ligand.

Assignment of the second substrate site Wf is less clear. The above description of the structure of the S3 state suggests that the second substrate would represent the newly bound terminal hydroxide ligand, in close proximity to O5/Ws. This result though appears at odds with MIMS data that show that Wf's exchange kinetics are almost identical for the S2 and S3 states [13,37,75], suggesting that it is associated with the Mn4O5Ca cofactor in the S2 and S3 states in the same way [38,75]. A possible solution is that Wf represents a pre-existing water ligand of the cluster (W2 bound to the Mn4 ion or W3 bound to Ca2+ ion) which is relocated in the S3 state, suggesting a concerted mechanism for substrate delivery [38,71,75,76].

7. The reaction cycle of the catalyst

As described above, the water oxidizing cofactor takes two discrete conformations during its catalytic cycle and as such, its reaction cycle can be divided into two (figure 6). In the ‘resting’ S-states (S0, S1), the cofactor adopts a low-spin configuration (S = 1/2 and 0) [62,63]. Calculations demonstrate that this is a property of the incomplete cuboidal unit [52,55], i.e. a manganese unit with a vacant coordination site. In this form, the catalyst is inactivated. In the ‘activated’ S states, the cofactor instead adopts a high-spin configuration (S = 3) [56], concomitant with the insertion of a water ligand into the cubodial unit. S2 displays both low- and high-spin forms (S = 1/2 for the open cubane form S2A, S = 5/2 for the closed cubane form S2B) suggesting that it may represent a switching point in the catalytic cycle (figure 6). Spin-state interconversion, which involves the opening of the cubodial unit may facilitate water insertion/relocation into the heterobimetallic cubane. It is noted that EPR data suggest that Ca2+ is necessary to proceed past the low-spin S2YZ• state, and thus Ca2+ may play a role either in allowing efficient S2A/S2B interconversion, or at least in allowing spin-state crossover [77–79]. It is then the high-spin topology that allows low barrier single-product formation to proceed, for example, via an oxo–oxyl coupling mechanism as proposed by Siegbahn [56,59,80]. Late second substrate binding may avoid deleterious two-electron chemistry (slow peroxide formation) in the resting states of the catalytic cycle [81].

8. Conclusion and outlook

The results described above place new, important restrictions on the structure of nature's water oxidizing cofactor, its catalytic cycle and the mechanism of water splitting and O2 evolution. These are listed below with reference to design criteria for the development of biomimetic and bioinspired water splitting catalysts using manganese.

(i) The oxidation states of all individual Mn sites in all S-states are now resolved: S0 (MnIII)3MnIV, S1 (MnIII)2(MnIV)2, S2 MnIII(MnIV)3, S3 (MnIV)4 and ligand oxidation can be excluded prior to formation of the S4 state. This assignment is in agreement with the average Mn oxidation state inferred for heterogeneous manganese oxide water oxidation catalysts [82].

(ii) An exchangeable μ-oxo bridge (O5) is likely the first substrate of the water splitting reaction. This result, coupled with the observation that the cofactor gains a new hydroxide ligand in the S3 state supports the notion that the O–O bond forms between oxygen ligands of neighbouring redox-active Mn ions (Mn1 and Mn4).

(iii) Structural flexibility of the cofactor appears to be critical for function, namely catalyst activation, i.e. the formation of the S3 state, which is coupled to second substrate inclusion. This flexibility is only readily apparent in the S2 state, with the other S-states adopting a single preferred configuration. This property seems to be conferred in part by the Ca2+ ion, which also may act to tune the redox/magnetic properties of the cuboidal (Mn3Ca) unit [83], or of the tyrosine radical [36] or both. The inclusion of calcium has been correlated with enhanced water splitting activity of manganese oxide water oxidation catalysts [82,84].

The heterobimetallic nature of the cluster and the choice of Mn as the redox active metal for biological water splitting must therefore reflect a confluence of effects. Key properties are

(i) that it can stabilize multiple oxidation states to be accessed over a narrow range of redox potentials. This property is derived from protein/cofactor interactions being able to tune the pKa of cofactor bound water (substrate) molecules allowing sequential H+ release upon each Mn oxidation event;

(ii) the possibility that the heterobimetallic cubane allows the formation of an energetically accessible MnV-oxo or MnIV-oxyl radical in the transition state [85–88]; and

(iii) that the Mn ions represent trapped valence states of local high-spin states, which magnetically couple together in a precise way in each S-state.

While the points above pose interesting theoretical questions, from a more practical perspective, the static properties of heterobimetallic cubane appear to be universal and can be reproduced in simpler model compound systems [89–91]. Similarly, heterogeneous Mn/Ca materials already show reasonable, if somewhat slow water splitting capacity normalized to Mn content [82,92,93]. Although it cannot be excluded that such Mn/Ca materials adopt lower efficiency pathways for O–O bond formation, the alternative explanation, that such materials only contain an intrinsically small number of ‘active’ heterobimetallic cubane units, seems equally reasonable. If, as figure 6 suggests, nature's catalyst essentially toggles between an ‘inactive’ and ‘active’ form, the latter having a substrate bound within the heterobimetallic cubane, the challenge in designing a better catalyst amounts to introducing this property (structural flexibility) or stabilizing a solvent accessible cuboidal structure that is stable/robust. These key design criteria should form the basis for new synthetic complex development—akin to the progress recently made in H2 production using hydrogenase mimics [9]—for water splitting catalysts using manganese.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Alain Boussac (Saclay, France) and Prof. Johannes Messinger (Umea, Sweden) for helpful discussions.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the MPG, the Cluster of Excellence RESOLV (EXC 1069) and the DIP (Lu 315/17-1), both funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

References

- 1.Wydrzynski TJ, Hillier W. (eds). 2012. Molecular solar fuels. Cambridge, UK: RSC Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlögl R. (ed.). 2013. Chemical energy storage. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olah GA, Goeppert A, Prakash GKS. 2006. Beyond oil and gas: the methanol economy. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faunce TA. 2011. Future perspectives on solar fuels. In Molecular solar fuels (eds Wydrzynski TJ, Hillier W.), pp. 506–528. Cambridge, UK: RSC Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faunce TA, et al. 2013. Energy and environment policy case for a global project on artificial photosynthesis. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 695–698. ( 10.1039/c3ee00063j) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rand DAJ, Dell RM. 2008. Hydrogen energy. Challenges and prospects. Cambridge, UK: RSC Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nocera DG. 2012. The artificial leaf. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 767–776. ( 10.1021/ar2003013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lubitz W, Ogata H, Rüdiger O, Reijerse E. 2014. Hydrogenases. Chem. Rev. 114, 4081–4148. ( 10.1021/cr4005814) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simmons TR, Berggren G, Bacchi M, Fontecave M, Artero V. 2014. Mimicking hydrogenases: from biomimetics to artificial enzymes. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 270, 127–150. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.12.018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holm RH, Solomon EI. (eds). 2014. Special issue on Bioinorganic enzymology II. Chem. Rev. 114 (7,8). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen J-R, Kamiya N. 2011. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9Å. Nature 473, 55–60. ( 10.1038/nature09913) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolet Y, Piras C, Legrand P, Hatchikian CE, Fontecilla-Camps JC. 1999. Desulfovibrio desulfuricans iron hydrogenase: the structure shows unusual coordination to an active site Fe binuclear center. Structure 7, 13–23. ( 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80005-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox N, Pantazis DA, Neese F, Lubitz W. 2013. Biological water oxidation. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1588–1596. ( 10.1021/ar3003249) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McEvoy JP, Brudvig GW. 2006. Water-splitting chemistry of photosystem II. Chem. Rev. 106, 4455–4483. ( 10.1021/cr0204294) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renger G. (ed.). 2008. Primary processes of photosynthesis—part 2. Principles and apparatus. Cambridge, UK: RSC Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yano J, Yachandra V. 2014. Mn4Ca cluster in photosynthesis: where and how water is oxidized to dioxygen. Chem. Rev. 114, 4175–4205. ( 10.1021/cr4004874) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandelia ME, Ogata H, Lubitz W. 2010. Intermediates in the catalytic cycle of [NiFe] hydrogenase: functional spectroscopy of the active site. Chem. Phys. Chem. 11, 1127–1140. ( 10.1002/cphc.200900950) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shafaat HS, Rüdiger O, Ogata H, Lubitz W. 2013. [NiFe] hydrogenases: a common active site for hydrogen metabolism under diverse conditions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 986–1002. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.01.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cammack R. 2011. The catalytic machinery. In Hydrogen as a fuel: learning from nature (eds Cammack R, Frey M, Robson R.), pp. 159–180. London, UK: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaffron H, Rubin J. 1942. Fermentative and photochemical production of hydrogen in green algae. Gen. Physiol. 26, 219–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghirardi ML, Dubini A, Yu J, Maness P-C. 2009. Photobiological hydrogen-producing systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 52–61. ( 10.1039/B718939G) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruse O, Hankamer B. 2010. Microalgal hydrogen production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 21, 238–243. ( 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.03.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melis A, Happe T. 2001. Hydrogen production. Green algae as a source of energy. Plant Physiol. 127, 740–748. ( 10.1104/pp.010498) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madden C, Vaughn MD, Diez-Perez I, Brown KA, King PW, Gust D, Moore AL, Moore TA. 2012. Catalytic turnover of [FeFe]-hydrogenase based on single-molecule imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 1577–1582. ( 10.1021/ja207461t) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohad I, Kyle DJ, Arntzen CJ. 1984. Membrane protein damage and repair: removal and replacement of inactivated 32-kilodalton polypeptides in chloroplast membranes. J. Cell Biol. 99, 481–485. ( 10.1083/jcb.99.2.481) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swanson KD, et al. 2015. [FeFe]-hydrogenase oxygen inactivation is initiated at the H cluster 2Fe subcluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1809–1816. ( 10.1021/ja510169s) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vincent KA, Parkin A, Lenz O, Albracht SPJ, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Cammack R, Friedrich B, Armstrong FA. 2005. Electrochemical definitions of O2 sensitivity and oxidative inactivation in hydrogenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 18 179–18 189. ( 10.1021/ja055160v) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandelia ME, Lubitz W, Nitschke W. 2012. Evolution and diversification of Group 1 [NiFe] hydrogenases. Is there a phylogenetic marker for O2-tolerance? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 1565–1575. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.04.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandelia ME, Nitschke W, Infossi P, Giudici-Orticoni MT, Bill E, Lubitz W. 2011. Characterization of a unique [FeS] cluster in the electron transfer chain of the oxygen tolerant [NiFe] hydrogenase from Aquifex aeolicus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6097–6102. ( 10.1073/pnas.1100610108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shomura Y, Yoon K-S, Nishihara H, Higuchi Y. 2011. Structural basis for a [4Fe-3S] cluster in the oxygen-tolerant membrane-bound [NiFe]-hydrogenase. Nature 479, 253–257. ( 10.1038/nature10504) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fritsch J, Scheerer P, Frielingsdorf S, Kroschinsky S, Friedrich B, Lenz O, Spahn CMT. 2011. The crystal structure of an oxygen-tolerant hydrogenase uncovers a novel iron–sulphur centre. Nature 479, 249–252. ( 10.1038/nature10505) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wulff P, Day CC, Sargent F, Armstrong FA. 2014. How oxygen reacts with oxygen-tolerant respiratory [NiFe]-hydrogenases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 6606–6611. ( 10.1073/pnas.1322393111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kok B, Forbush B, McGloin M. 1970. Cooperation of charges in photosynthetic O2 evolution—I. A linear four step mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 11, 457–467. ( 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1970.tb06017.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klauss A, Haumann M, Dau H. 2012. Alternating electron and proton transfer steps in photosynthetic water oxidation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 16 035–16 040. ( 10.1073/pnas.1206266109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cardona T, Sedoud A, Cox N, Rutherford AW. 2012. Charge separation in photosystem II: a comparative and evolutionary overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 26–43. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Retegan M, Cox N, Lubitz W, Neese F, Pantazis D. 2014. The first tyrosyl radical intermediate formed in the S2–S3 transition of photosystem II. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 11 901–11 910. ( 10.1039/c4cp00696h) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hillier W, Messinger J. 2005. Mechanism of photosynthetic oxygen production. In Photosystem II: the light-driven water:plastoquinone oxidoreductase (eds Wydrzynski T, Satoh K.), pp. 567–608. In series Advances in photosynthesis and respiration, vol. 22 (ed. Govindjee) Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox N, Messinger J. 2013. Reflections on substrate water and dioxygen formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 1020–1030. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.01.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker K, Cormann KU, Nowaczyk MM. 2011. Assembly of the water-oxidizing complex in photosystem II. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 104, 204–211. ( 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.02.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dasgupta J, Ananyev GM, Dismukes GC. 2008. Photoassembly of the water-oxidizing complex in photosystem II. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 252, 347–360. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suga M, et al. 2015. Native structure of photosystem II at 1.95 Å resolution viewed by femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature 517, 99–103. ( 10.1038/nature13991) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dau H, Haumann M. 2008. The manganese complex of photosystem II in its reaction cycle—basic framework and possible realization at the atomic level. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 252, 273–295. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glöckner C, Kern J, Broser M, Zouni A, Yachandra V, Yano J. 2013. Structural changes of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II during the catalytic cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 22 607–22 620. ( 10.1074/jbc.M113.476622) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haumann M, et al. 2005. Structural and oxidation state changes of the photosystem II manganese complex in four transitions of the water oxidation cycle (S0 → S1, S1 → S2, S2 → S3, and S3,4 → S0) characterized by X-ray absorption spectroscopy at 20 K and room temperature. Biochemistry 44, 1894–1908. ( 10.1021/bi048697e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pushkar YL, Yano J, Sauer K, Boussac A, Yachandra VK. 2008. Structural changes in the Mn4Ca cluster and the mechanism of photosynthetic water splitting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1879–1884. ( 10.1073/pnas.0707092105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yano J, et al. 2006. Where water is oxidized to dioxygen: structure of the photosynthetic Mn4Ca cluster. Science 314, 821–825. ( 10.1126/science.1128186) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galstyan A, Robertazzi A, Knapp EW. 2012. Oxygen-evolving Mn cluster in photosystem II: the protonation pattern and oxidation state in the high-resolution crystal structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 7442–7449. ( 10.1021/ja300254n) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luber S, Rivalta I, Umena Y, Kawakami K, Shen J-R, Kamiya N, Brudvig GW, Batista VS. 2011. S1-State model of the O2-evolving complex of photosystem II. Biochemistry 50, 6308–6311. ( 10.1021/bi200681q) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grundmeier A, Dau H. 2012. Structural models of the manganese complex of photosystem II and mechanistic implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 88–105. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zimmermann JL, Rutherford AW. 1984. EPR studies of the oxygen-evolving enzyme of photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 767, 160–167. ( 10.1016/0005-2728(84)90091-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boussac A, Girerd J-J, Rutherford AW. 1996. Conversion of the spin state of the manganese complex in photosystem II induced by near-infrared light. Biochemistry 35, 6984–6989. ( 10.1021/bi960636w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pantazis DA, Ames W, Cox N, Lubitz W, Neese F. 2012. Two interconvertible structures that explain the spectroscopic properties of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II in the S2 state. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 9935–9940. ( 10.1002/anie.201204705) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bovi D, Narzi D, Guidoni L. 2013. The S2 state of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II explored by QM/MM dynamics: spin surfaces and metastable states suggest a reaction path towards the S3 state. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 11 744–11 749. ( 10.1002/anie.201306667) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Isobe H, Shoji M, Yamanaka S, Umena Y, Kawakami K, Kamiya N, Shen JR, Yamaguchi K. 2012. Theoretical illumination of water-inserted structures of the CaMn4O5 cluster in the S2 and S3 states of oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II: full geometry optimizations by B3LYP hybrid density functional. Dalton Trans. 41, 13 727–13 740. ( 10.1039/c2dt31420g) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krewald V, Retegan M, Cox N, Messinger J, Lubitz W, DeBeer S, Neese F, Pantazis D. 2015. Metal oxidation states in biological water splitting. Chem. Sci. 6, 1676–1695. ( 10.1039/C4SC03720K) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cox N, Retegan M, Neese F, Pantazis DA, Boussac A, Lubitz W. 2014. Electronic structure of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II prior to O-O bond formation. Science 345, 804–808. ( 10.1126/science.1254910) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lohmiller T, et al. 2014. Structure, ligands and substrate coordination of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II in the S2 state: a combined EPR and DFT study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 11 877–11 892. ( 10.1039/c3cp55017f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rapatskiy L, et al. 2012. Detection of the water-binding sites of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II using W-band 17O electron–electron double resonance-detected NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16 619–16 634. ( 10.1021/ja3053267) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siegbahn PEM. 2013. Water oxidation mechanism in photosystem II, including oxidations, proton release pathways, O–O bond formation and O2 release. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 1003–1019. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.10.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Noguchi T. 2008. FTIR detection of water reactions in the oxygen-evolving centre of photosystem II. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 363, 1189–1195. ( 10.1098/rstb.2007.2214) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dau H, Liebisch P, Haumann M. 2005. The manganese complex of oxygenic photosynthesis conversion of five coordinated Mn(III) to six coordinated Mn(IV) in the S2–S3 transition is implied by XANES simulations. Phys. Scripta 2005, 844 ( 10.1238/Physica.Topical.115a00844) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Messinger J, Robblee JH, Yu WO, Sauer K, Yachandra VK, Klein MP. 1997. The SO state of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II is paramagnetic: detection of an EPR multiline signal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 11 349–11 350. ( 10.1021/ja972696a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamauchi T, Mino H, Matsukawa T, Kawamori A, Ono T. 1997. Parallel polarization electron paramagnetic resonance studies of the S1-state manganese cluster in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving system. Biochemistry 36, 7520–7526. ( 10.1021/bi962791g) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Messinger J, Badger M, Wydrzynski T. 1995. Detection of one slowly exchanging substrate water molecule in the S3 state of photosystem II. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 3209–3213. ( 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hillier W, Wydrzynski T. 2000. The affinities for the two substrate water binding sites in the O2 evolving complex of photosystem II vary independently during S-state turnover. Biochemistry 39, 4399–4405. ( 10.1021/bi992318d) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hillier W, Wydrzynski T. 2004. Substrate water interactions within the photosystem II oxygen evolving complex. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 4882–4889. ( 10.1039/b407269c) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hillier W, Wydrzynski T. 2008. 18O-Water exchange in photosystem II: substrate binding and intermediates of the water splitting cycle. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 252, 306–317. ( 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cox N, Lubitz W, Savitsky A. 2013. W-band ELDOR-detected NMR (EDNMR) spectroscopy as a versatile technique for the characterisation of transition metal–ligand interactions. Mol. Phys. 111, 2788–2808. ( 10.1080/00268976.2013.830783) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beck WF, De Paula JC, Brudvig GW. 1986. Ammonia binds to the manganese site of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II in the S2 state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108, 4018–4022. ( 10.1021/ja00274a027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Britt RD, Zimmermann JL, Sauer K, Klein MP. 1989. Ammonia binds to the catalytic manganese of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Evidence by electron spin-echo envelope modulation spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 3522–3532. ( 10.1021/ja00192a006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pérez Navarro M, et al. 2013. Ammonia binding to the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II identifies the solvent-exchangeable oxygen bridge (µ-oxo) of the manganese tetramer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15 561–15 566. ( 10.1073/pnas.1304334110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schraut J, Kaupp M. 2014. On ammonia binding to the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II: a quantum chemical study. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 7300–7308. ( 10.1002/chem.201304464) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hou L-H, Wu C-M, Huang H-H, Chu H-A. 2011. Effects of ammonia on the structure of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II as revealed by light-induced FTIR difference spectroscopy. Biochemistry 50, 9248–9254. ( 10.1021/bi200943q) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hendry G, Wydrzynski T. 2003. 18O isotope exchange measurements reveal that calcium is involved in the binding of one substrate-water molecule to the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II. Biochemistry 42, 6209–6217. ( 10.1021/bi034279i) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nilsson H, Krupnik T, Kargul J, Messinger J. 2014. Substrate water exchange in photosystem II core complexes of the extremophilic red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1837, 1257–1262. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.04.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Narzi D, Bovi D, Guidoni L. 2014. Pathway for Mn-cluster oxidation by tyrosine-Z in the S2 state of photosystem II. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 8723–8728. ( 10.1073/pnas.1401719111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boussac A, Rutherford AW. 1988. Nature of the inhibition of the oxygen-evolving enzyme of photosystem II induced by sodium chloride washing and reversed by the addition of calcium(2+) or strontium(2+). Biochemistry 27, 3476–3483. ( 10.1021/bi00409a052) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boussac A, Zimmermann JL, Rutherford AW. 1989. EPR signals from modified charge accumulation states of the oxygen-evolving enzyme in calcium-deficient photosystem II. Biochemistry 28, 8984–8989. ( 10.1021/bi00449a005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sivaraja M, Tso J, Dismukes GC. 1989. A calcium-specific site influences the structure and activity of the manganese cluster responsible for photosynthetic water oxidation. Biochemistry 28, 9459–9464. ( 10.1021/bi00450a032) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Siegbahn PEM. 2009. Structures and energetics for O2 formation in photosystem II. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1871–1880. ( 10.1021/ar900117k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rutherford AW. 1989. Photosystem II, the water-splitting enzyme. Trends Biochem. Sci. 14, 227–232. ( 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90032-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wiechen M, Berends H-M, Kurz P. 2012. Water oxidation catalysed by manganese compounds: from complexes to ‘biomimetic rocks’. Dalton Trans. 41, 21–31. ( 10.1039/C1DT11537E) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsui EY, Tran R, Yano J, Agapie T. 2013. Redox-inactive metals modulate the reduction potential in heterometallic manganese–oxido clusters. Nat. Chem. 5, 293–299. ( 10.1038/nchem.1578) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wiechen M, Zaharieva I, Dau H, Kurz P. 2012. Layered manganese oxides for water-oxidation: alkaline earth cations influence catalytic activity in a photosystem II-like fashion. Chem. Sci. 3, 2330–2339. ( 10.1039/c2sc20226c) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lassalle-Kaiser B, Hureau C, Pantazis DA, Pushkar Y, Guillot R, Yachandra VK, Yano J, Neese F, Anxolabéhère-Mallart E. 2010. Activation of a water molecule using a mononuclear Mn complex: from Mn-aquo, to Mn-hydroxo, to Mn-oxyl via charge compensation. Energy Environ. Sci. 3, 924–938. ( 10.1039/b926990h) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sameera WMC, McKenzie CJ, McGrady JE. 2011. On the mechanism of water oxidation by a bimetallic manganese catalyst: a density functional study. Dalton Trans. 40, 3859–3870. ( 10.1039/c0dt01362e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yamaguchi K, Takahara Y, Fueno T. 1986. Ab-initio molecular orbital studies of structure and reactivity of transition metal oxo compounds. In Applied quantum chemistry (eds Smith VH, Schaefer HF, Morokuma K.), pp. 155–184. Boston, MA: Reidel. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Siegbahn PEM, Crabtree RH. 1998. Manganese oxyl radical intermediates and O−O bond formation in photosynthetic oxygen evolution and a proposed role for the calcium cofactor in photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 117–127. ( 10.1021/ja982290d) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kanady JS, Tsui EY, Day MW, Agapie T. 2011. A synthetic model of the Mn3Ca subsite of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II. Science 333, 733–736. ( 10.1126/science.1206036) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mukherjee S, et al. 2012. Synthetic model of the asymmetric [Mn3CaO4] cubane core of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 2257–2262. ( 10.1073/pnas.1115290109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Krewald V, Neese F, Pantazis DA. 2013. On the magnetic and spectroscopic properties of high-valent Mn3CaO4 cubanes as structural units of natural and artificial water-oxidizing catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5726–5739. ( 10.1021/ja312552f) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Najafpour MM, Ehrenberg T, Wiechen M, Kurz P. 2010. Calcium manganese(III) oxides (CaMn2O4 · xH2O) as biomimetic oxygen-evolving catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 2233–2237. ( 10.1002/anie.200906745) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zaharieva I, Najafpour MM, Wiechen M, Haumann M, Kurz P, Dau H. 2011. Synthetic manganese–calcium oxides mimic the water-oxidizing complex of photosynthesis functionally and structurally. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 2400–2408. ( 10.1039/c0ee00815j) [DOI] [Google Scholar]