Abstract

Aims: Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) is an iron overload disease that is caused by mutations in HFE, HJV, and several other genes. However, whether HFE-HH and HJV-HH share a common pathway via hepcidin regulation is currently unclear. Recently, some HH patients have been reported to carry concurrent mutations in both the HFE and HJV genes. To dissect the roles and molecular mechanisms of HFE and/or HJV in the pathogenesis of HH, we studied Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− double-knockout mouse models. Results: Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice developed iron overload in multiple organs at levels comparable to Hjv−/− mice. After an acute delivery of iron, the expression of hepcidin (i.e., Hamp1 mRNA) was increased in the livers of wild-type and Hfe−/− mice, but not in either Hjv−/− or Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice. Furthermore, iron-induced phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 was not detected in the livers of Hjv−/− or Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice. Innovation: We generated and phenotypically characterized Hfe−/−Hjv−/− double-knockout mice. In addition, because they faithfully phenocopy clinical HH patients, these mouse models are an invaluable tool for mechanistically dissecting how HFE and HJV regulate hepcidin expression. Conclusions: Based on our results, we conclude that HFE may depend on HJV for transferrin-dependent hepcidin regulation. The presence of residual hepcidin in the absence of HFE suggests either the presence of an unknown regulator (e.g., TFR2) that is synergistic with HJV or that HJV is sufficient to maintain basal levels of hepcidin. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22, 1325–1336.

Introduction

Iron is an essential element for normal cellular function. However, iron is also a pro-oxidant factor that causes oxidative stress by catalyzing a Fenton reaction, yielding reactive oxygen species. Iron overload-induced oxidative damage can cause cellular defects such as mitochondrial and DNA damage, lipid peroxidation, and protein modification, all of which subsequently cause damage to multiple organs, including the liver, heart, and pancreas of patients with hemochromatosis (18).

Iron metabolism has been studied extensively during the past decade. In particular, the hepcidin-ferroportin regulatory axis has been investigated in an attempt to understand how the body maintains iron homeostasis (2, 13, 16). Hepcidin was initially identified as an antimicrobial peptide that is secreted by the liver (20) and exerts negative effects on intestinal iron absorption and iron recycling in macrophages (25). Moreover, classic hereditary hemochromatosis (HH)—which is characterized by the progressive development of severe iron overload in multiple organs—can result directly from hepcidin deficiency (1, 6, 31).

Many proteins and pathways are involved in the regulation of hepcidin. For example, changes in transferrin saturation can cause conformational changes in HFE/TfR2 (transferrin receptor 2), which modulates hepcidin expression (12, 15, 33). Several bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family members (including Bmp2, Bmp4, Bmp6, and Bmp9) can upregulate hepcidin expression via the BMP/Smad pathway (3, 35). Moreover, inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6) and infectious stimuli can activate hepcidin via the IL-6/Stat3 pathway (4, 24, 36).

Innovation.

For more than a decade, hepcidin has been studied as a potential molecule for preventing iron overload. However, although the proteins HJV and HFE are key modulators of hepcidin expression, whether these two proteins act via parallel or converging pathways remains unknown. We therefore generated Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice and found that these double-knockout mice develop an iron overload phenotype that is strikingly similar to Hjv−/− single-knockout mice. Importantly, the response of hepcidin to acute iron treatment was dominated by HJV (but not HFE), and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal regulated kinase (Erk) pathway was not mainly involved in this process. These findings suggest that HJV is the key regulator of hepcidin and that HFE acts in an HJV-dependent manner.

HFE plays a regulatory role in the hepcidin pathway (6, 41), and mutations in the HFE gene cause Type I HH (10). In addition, HFE-deficient mice develop an iron overload phenotype that is strikingly similar to Type I HH in patients (41), and a study by Schmidt et al. revealed that HFE positively modulates the expression of hepcidin (33). HFE interacts with transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) and competes with the receptor's transferrin (Tf) binding site (23), thereby activating downstream signaling pathways, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Because the MAPK pathway can crosstalk with the BMP/Smad pathway, this activation can upregulate hepcidin expression at the transcriptional level (15, 33).

HJV is another principal modulator of hepcidin expression, and mutations in the HJV gene cause Type II HH (27). Membrane-bound HJV binds to BMPs, thereby acting as a co-receptor along with the Bmp receptor (3). The expression of Bmp6 is positively correlated with iron content in the liver (19), and binding of Bmp6 to the Bmp receptor triggers Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation, thus upregulating hepcidin expression. In vitro studies have shown that HJV is required for activation of the BMP/Smad pathway (5, 26). Thus, HJV is considered a necessary component of the Bmp6/Smad pathway.

The relationship between HFE and HJV has long been debated. Studies suggest that HFE/TfR2 activates the MAPK pathway (28, 29), although the extent of the crosstalk between the MAPK and BMP/Smad pathways remains unclear. Recently, patients with mutations in both HFE and HJV have been reported (22), revealing the complexity of mutations and pathogenesis in HH patients. Understanding the roles played by HFE and HJV in regulating hepcidin will help unravel the genetic analyses and therapeutic diagnoses of patients with HH.

To address these issues, we characterized the phenotypes, hepcidin expression levels, and Smad phosphorylation levels in Hfe−/−, Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− knockout mouse models. Interestingly, the Hfe−/−Hjv−/− double-knockout mice developed the same iron overload phenotype as Hjv−/− single-knockout mice. Consistent with this finding, hepatic hepcidin expression and Smad protein phosphorylation levels were similar between the Hfe−/−Hjv−/−and Hjv−/− mice. Furthermore, an acute oral bolus of iron significantly increased hepcidin mRNA levels in the livers of Hfe−/− mice, but was without effect on the Hfe−/−Hjv−/− and Hjv−/− mice. Based on these results, we hypothesize that HFE requires HJV to activate downstream signal transduction pathways.

Results

Hfe knockout does not increase iron overload in Hjv−/− mice

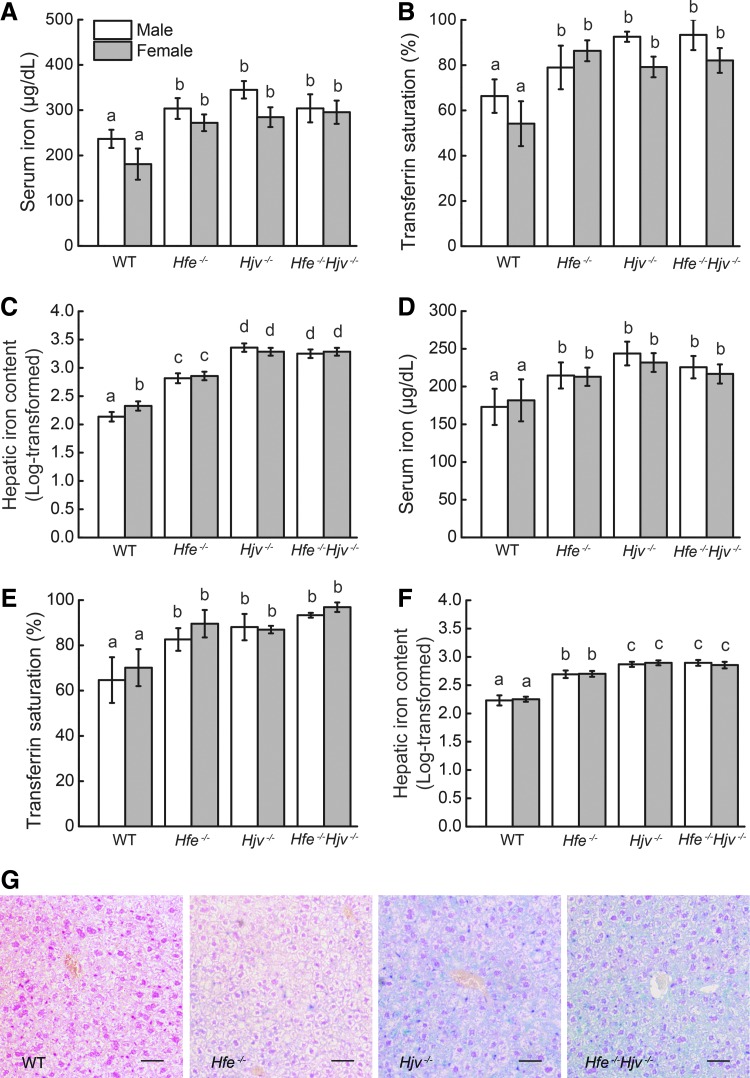

Eight-week-old wild-type, Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (three to four mice per group) were sacrificed, and blood and tissue samples were collected for analysis. The serum iron (Fig. 1A) and transferrin saturation (Fig. 1B) levels were significantly elevated in all three knockout lines. The hepatic iron content (HIC) was higher in both the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice compared with the Hfe−/− mice, with no difference between the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (Fig. 1C). This trend was observed in both males and females in each line, and we found no difference between male and female in Hfe−/−, Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice with respect to iron parameters, except that HIC in female wild-type mice is higher than in male wild-type mice. Prussian blue staining of liver sections revealed iron overload in the hepatocytes of all three knockout lines, with the most intense staining in Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− hepatocytes (Fig. 1G).

FIG. 1.

Iron accumulates in Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− double-knockout mice. (A) Serum iron, (B) transferrin saturation, and (C) hepatic non-heme iron levels were measured in 8-week-old WT (eight male, eight female), Hfe−/− (eight male, eight female), Hjv−/− (eight male, eight female), and Hjv−/−Hfe−/− (eight male, eight female) mice. (D) Serum iron, (E) transferrin saturation, and (F) hepatic non-heme iron levels were measured in 3-week-old WT (eight male, eight female), Hfe−/− (eight male, eight female), Hjv−/− (eight male, eight female), and Hjv−/−Hfe−/− (eight male, eight female) mice. In this and subsequent figures, the data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis in (C) and (F) was carried out by using log-transformed values to meet homogenous variances, and then all data were compared using an ANOVA with Tukey's test. Labeled without a common letter (a, b, c, or d) indicates significant difference among tested groups (p<0.05). (G) Liver sections were stained with Perls Prussian blue. The scale bar represents 100 μm. ANOVA, analysis of variance; WT, wild-type.

To examine the roles of Hjv and Hfe in iron homeostasis at a younger age, we measured the serum and liver iron contents in 3-week-old wild-type and knockout mice. At this age, the serum iron and transferrin saturation levels did not differ significantly between the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (Fig. 1D, E). Similar to the 8-week-old mice, all three knockout lines had significant hepatic iron overload compared with wild-type mice, with both the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice having higher hepatic iron overload than the Hfe−/− mice (Fig. 1F). We found no difference between males and females in Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice with respect to iron parameters.

Reduced hepcidin expression in Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice

Next, we used real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to measure the basal hepatic expression levels of Hamp1, Id1, Smad7, and Bmp6 in wild-type mice and all three knockout mouse lines of both genders. Compared with wild-type mice, all three knockout lines had significantly lower Hamp1 expression; specifically, the Hamp1 mRNA level in Hfe−/− mice was 35% of wild-type levels, and Hamp1 mRNA levels in both Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice was <2.5% of wild-type levels (Fig. 2A). There was no significant difference between the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice with respect to Hamp1 expression. Similarly, the expression levels of both Id1 and Smad7 were lower in the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− compared with the wild-type and Hfe−/− mice, and there was no significance difference between the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (Fig. 2B, C). This trend was observed for both genders in every line. In general, Hamp1 mRNA levels are higher in females than those in males in wild-type, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice.

FIG. 2.

Hamp1, Id1, and Smad7 expression, and Bmp6/Smad signaling in Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− double-knockout mice. Hepatic (A) Hamp1, (B) Id1, (C) Smad7, and (D) Bmp6 mRNA levels were measured in 8-week-old wild-type (eight male, eight female), Hfe−/− (eight male, eight female), Hjv−/− (eight male, eight female), and Hjv−/−Hfe−/− (eight male, eight female) mice that were fed a standard diet; the mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA and are expressed relative to the mean value of wild-type males. The (E) Hamp1/Bmp6, (F) Id1/Bmp6, and (G) Smad7/Bmp6 ratios were calculated for each mouse and relative to the mean value of wild-type males. Statistical analyses were conducted by using log-transformed values to meet homogenous variances, and then all data were compared using an ANOVA with Tukey's test. Labeled without a common letter (a, b, c, d, or e) indicates significant difference among tested groups (p<0.05).

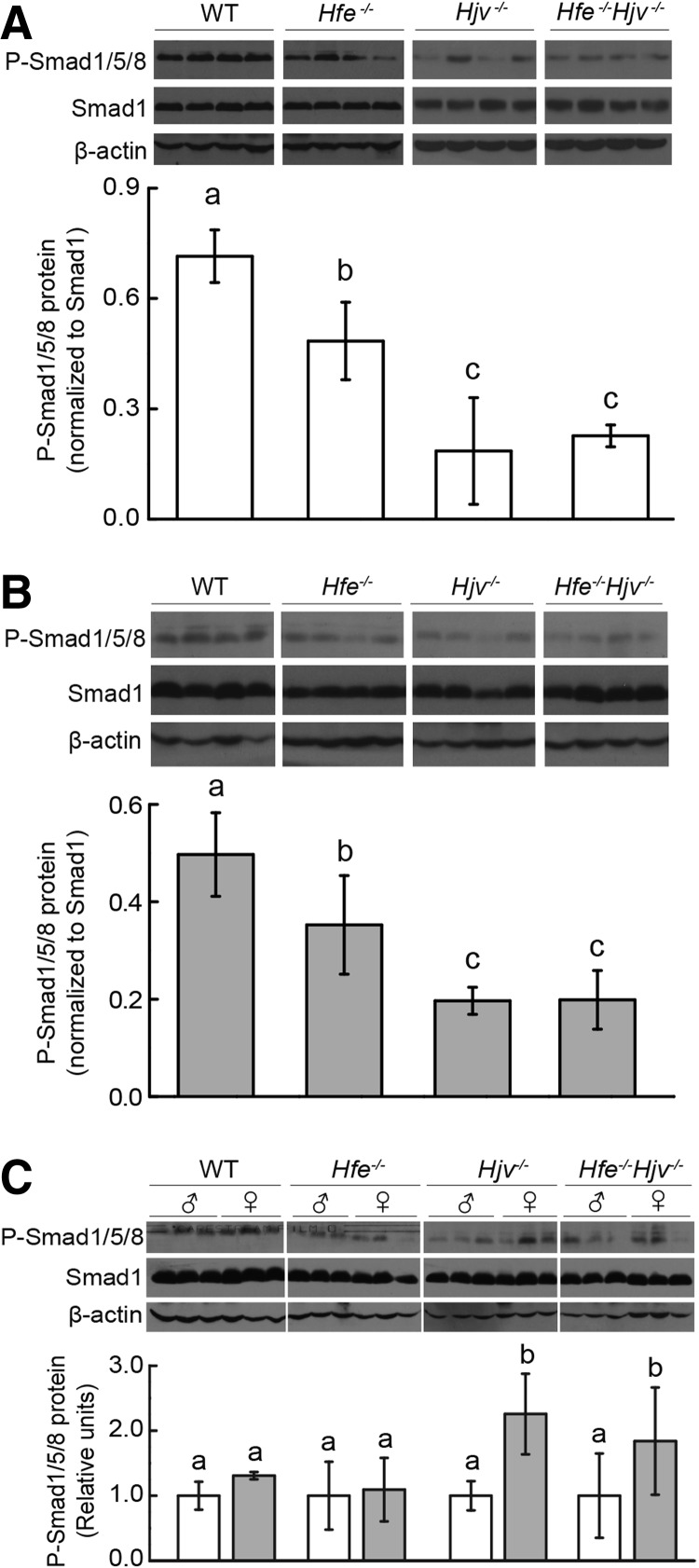

Compared with the wild-type and Hfe−/− mice, the hepatic expression of Bmp6 was significantly higher in both the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (Fig. 2D). Bmp6 expression was positively correlated to Hamp1 (and other Smad1/5/8 targeting genes, including Id1 and Smad7) levels when the Bmp/Smad pathway was intact; thus, we used the ratios of Hamp1/Bmp6, Id1/Bmp6, and Smad7/Bmp6 expression to assess the integrity of the Bmp/Smad pathway. We next measured the ratio of Hamp1/Bmp6 mRNA levels in all mouse lines (Fig. 2E). Hamp1/Bmp6 ratio was lower in all three knockout mice when compared with wild-type mice; the ratios in the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice were even lower compared with the Hfe−/− mice, although there was no significant difference between the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice. In addition, Hamp1/Bmp6 ratio was higher in females than in males in both Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice but not in wild-type or Hfe−/− mice. The ratios of Id1/Bmp6 mRNA and Smad7/Bmp6 mRNA (Fig. 2F, G) showed similar pattern as the ratio of Hamp1/Bmp6 in all mouse lines. We also measured the levels of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 (P-Smad1/5/8) in each gender using Western blot analysis. In comparison to WT mice, all three knockout lines showed attenuated P-Smad1/5/8. When three knockout lines were compared, we found that P-Smad1/5/8 levels in the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice are significantly lower than in the Hfe−/− mice. Notably, there was no apparent difference between Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (Fig. 3A, B).

FIG. 3.

Hepatic P-Smad1/5/8 levels in both male and female Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− double-knockout mice. Hepatic Smad1 and P-Smad1/5/8 levels in (A) male, (B) female, and (C) both genders were measured using Western blot analysis. The bands were quantified, and P-Smad1/5/8 levels were normalized to Smad1 levels. All data were compared using an ANOVA with Tukey's test. Labeled without a common letter (a, b, or c) indicates significant difference among tested groups (p<0.05).

Acute iron delivery alters hepcidin expression in an Hjv-dependent manner

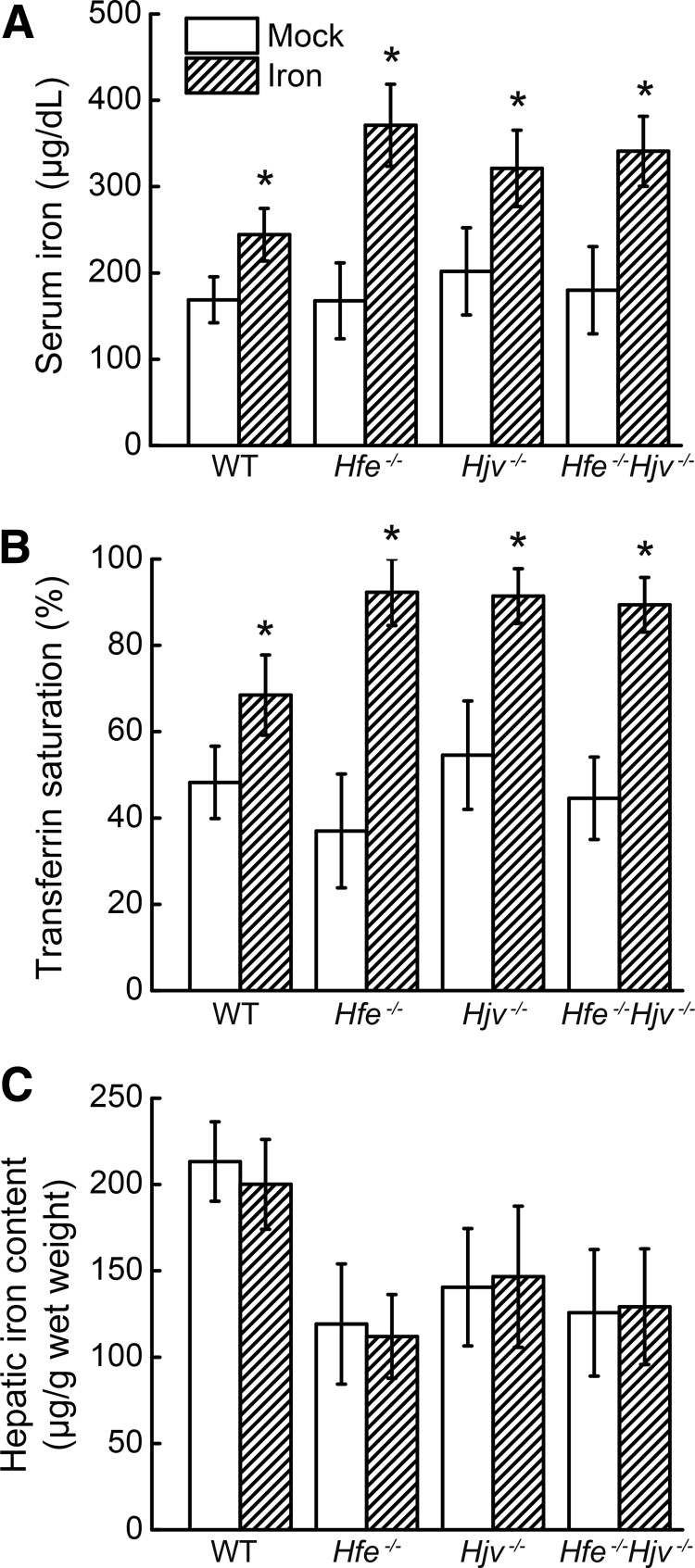

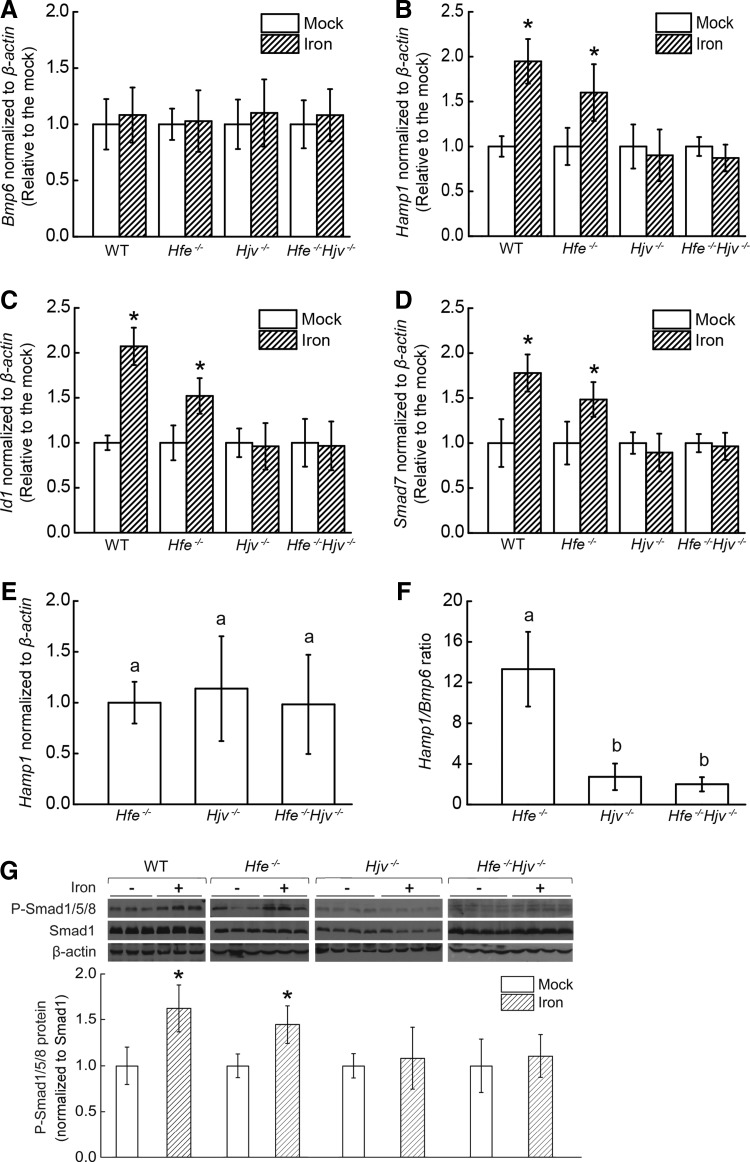

We next delivered an acute bolus of iron to the mice and measured the effect on hepcidin expression. All three knockout lines were first fed an iron-deficient diet for 3–5 weeks, and the wild-type mice were fed a standard diet containing normal levels of iron to achieve comparable iron levels between wild-type mice and knockout mice. All four groups were then given a single dose of iron by oral gavage to perturb the serum iron levels without affecting HIC. Four hours after treatment, the mice were sacrificed, and blood and tissue samples were collected for analysis. In each line (including the wild-type mice), the single delivery of iron significantly elevated the serum iron and transferrin saturation levels (Fig. 4A, B). Furthermore, HIC (Fig. 4C) and hepatic Bmp6 mRNA expression (Fig. 5A) were similar between the iron-treated and mock-treated groups. Interestingly, both the wild-type and Hfe−/− mice had significantly elevated hepatic Hamp1 mRNA expression (∼2-fold higher than the mock-treated mice); in contrast, hepatic Hamp1 mRNA levels were not affected by acute iron treatment in either the Hjv−/− or Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (Fig. 5B). Similar results were obtained with respect to hepatic Id1 and Smad7 mRNA levels (Fig. 5C, D). Hamp1 expression in the three knockout lines that were fed an iron-deficient diet did not differ; in contrast, the Hamp1/Bmp6 ratios were similar to the mice that were fed a normal diet (Fig. 5E, F). Hepatic P-Smad1/5/8 levels were also significantly elevated in the iron-treated wild-type and Hfe−/− mice, whereas the P-Smad1/5/8 levels were not affected by iron treatment in either the Hjv−/− or Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (Fig. 5G). These results were consistent in both genders.

FIG. 4.

Acute iron treatment alters serum iron levels and transferrin saturation but not hepatic iron content in wild-type, Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, or Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice. (A) Serum iron levels, (B) transferrin saturation, and (C) hepatic iron content were measured in the mice shown in Figure 3, which received mock (white bars) or iron (italic bars) treatment by oral gavage. The data were compared using the Student's t-test; *p<0.05 versus the respective mock group.

FIG. 5.

Hjv−/− and Hjv−/−Hfe−/− mice have an attenuated hepcidin response to acute iron treatment. Eight-week-old wild-type, Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hjv−/−Hfe−/− mice were given FeCl3 (“Iron”; n=8 mice/group) or distilled water (“Mock”; n=8 mice/group) by oral gavage; after 4 h, (A) Bmp6, (B) Hamp1, (C) Id1, (D) Smad7 mRNA, and (G) P-Smad1/5/8 levels were measured. Hepatic (E) Hamp1 mRNA levels in Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice that were fed an iron-deficient diet were detected, and (F) the hepatic Hamp1/Bmp6 ratio was calculated for each mouse. Hepatic Bmp6, Hamp1, Id1, and Smad7 mRNA was normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to the mean value of each genotype's respective mock group. Hepatic P-Smad1/5/8 levels were quantified, normalized to Smad1, and expressed relative to the mean value of each genotype's respective mock group. The data in (A–D) and (G) were analyzed using the Student's t-test; *p<0.05 versus the respective mock group. The data in (E, F) were compared using an ANOVA with Tukey's test. Labeled without a common letter (a, b) indicates significant difference among tested groups (p<0.05).

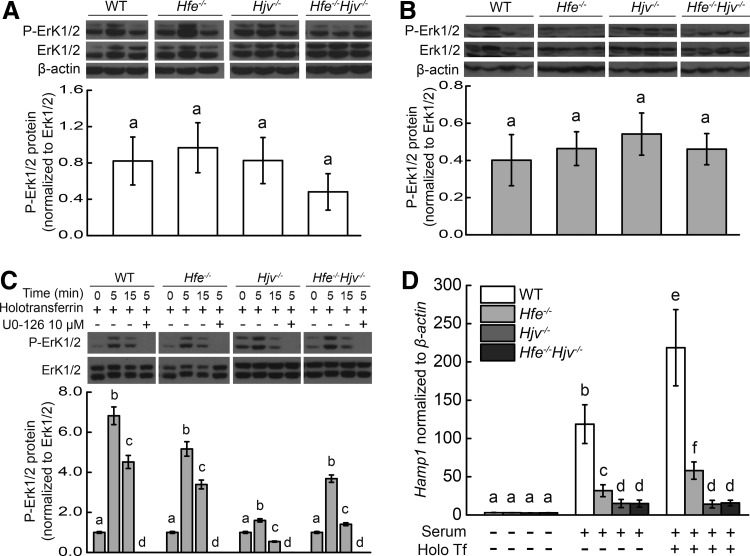

Crosstalk between the MAPK/Erk and Bmp/Smad pathways upstream of hepcidin expression

Under basal iron conditions, no significant difference in P-Erk1/2 levels was observed for either gender between the four lines (Fig. 6A, B). After acute iron treatment, no significant change in hepatic phosphorylated extracellular signal regulated kinase (P-Erk) levels was observed in either the wild-type mice or any of the three knockout lines (data not shown). Next, primary hepatocytes were isolated from all four mouse lines and treated with both serum and holotransferrin for 0, 5, or 15 min, after which P-Erk levels were measured using Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 6C, Erk phosphorylation levels peaked at 5 min in all four lines, but only in those of the Hjv−/−, and the double knockout mice returned to baseline at a 15-min time point when treated with serum+holotransferrin. In the presence of the MAPK inhibitor U0-126, Erk1/2 phosphorylation was completely blocked at the 5-min time point (Fig. 6C). Finally, Hamp1 expression was significantly upregulated in wild-type and Hfe−/− hepatocytes after treatment with holotransferrin, but was not activated in the Hjv−/− or Hfe−/−Hjv−/− hepatocytes (Fig. 6D).

FIG. 6.

The MAPK/Erk pathway is partial functional in Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice. Basal P-Erk1/2 levels were measured in (A) male and (B) female wild-type, Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice and normalized to total Erk1/2 protein levels. Primary hepatocytes were isolated from the indicated mouse lines, then treated with serum and holotransferrin in the absence or presence of 10 μM U0-126 for the indicated times. (C) P-Erk1/2 was then measured using Western blot analysis, and (D) Hamp1 mRNA was measured using real-time polymerase chain reaction. The bands were quantified, and P-Erk1/2 levels were normalized to Erk1/2 levels. The primary culture experiments were repeated three independent times. Statistical analyses were carried out by using log-transformed values to meet homogenous variances, and then all data were compared using an ANOVA with Tukey's test. Labeled without a common letter (a, b, c, d, e, or f) indicates significant difference among tested groups (p<0.05). Erk, extracellular signal regulated kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; P-Erk, phosphorylated Erk.

Discussion

In this study, we generated Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice and compared these double-knockout mice with wild-type and single-knockout Hfe−/− and Hjv−/− mice to identify the unique and/or synergistic roles that HFE and HJV play in regulating hepcidin. We found that both 3- and 8-week-old double-knockout mice develop an iron-related phenotype that is similar to Hjv−/− single-knockout mice (Fig. 1). These results were supported by our mRNA and protein level analyses, indicating that an additional deletion of HFE expression does not exacerbate the iron accumulation and hepcidin deficiency caused by the loss of HJV alone (Figs. 2 and 3). To evaluate the role of HFE and HJV in the hepcidin regulation pathway during acute changes in iron status, we fed these knockout mouse lines an iron-deficient diet to induce iron levels that were similar to wild-type levels and then acutely perturbed serum iron levels with a single oral treatment of iron. We then compared Hamp1 mRNA and P-Smad1/5/8 levels between the iron-treated and mock-treated groups. Interestingly, although iron treatment significantly increased Hamp1 expression in the wild-type and Hfe−/− mice, iron treatment had no effect on the Hjv−/− or Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (Fig. 5). Thus, these results suggest that Hjv elicits a stronger response to changes in serum iron levels than Hfe.

The basal iron parameters in the four mouse lines indicated differing degrees of iron homeostatic imbalance. To explore the underlying mechanisms, we measured Hamp1 expression and the downstream signaling pathways in the liver. Hamp1 expression was markedly reduced in the double-knockout mice to a level similar to the Hjv−/− mice. In contrast, although Hamp1 expression was reduced in the Hfe−/− mice, the effect was significantly weaker than in the Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice (Fig. 2A), indicating that this pathway is only partially impaired in Hfe−/− mice, consistent with a previous report (1). Furthermore, the different Hamp1 expression levels among these lines are consistent with their differing iron statuses, and the hepatic P-Smad1/5/8 levels support these results (Fig. 3A, B). Thus, disrupting basal hepcidin expression causes iron accumulation in the knockout mice. Recently, digenic inheritance of mutations in both HFE and HJV in patients was reported to cause juvenile hemochromatosis with a phenotype similar to patients with a single (monogenic inherited) HJV mutation (22), which supports our findings in Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice.

Gender is an important modifying factor in iron homeostasis. For example, HFE-HH hemochromatosis has higher penetrance in men than in women, mostly likely because of the physiological iron loss through menstruation and pregnancy (14). However, penetrance in HJV-HH was similar in women and men. In our study, we found there are no differences in measured iron parameters between female and male Hjv−/− or Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice. Interestingly, we observed that hepatic Hamp1 expression levels in female mice were higher than those in male mouse lines, and higher P-Smad1/5/8 levels were found in females than in males in terms of Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− lines (Fig. 3C), in which similar phenomena were also indicated in previous reports (21). Finally, the mechanisms that underlie iron metabolism differ between mice and humans (2). Therefore, the gender-related effect on the penetrance of hemochromatosis in humans with combined HFE and HJV mutations might not correlate directly with our animal studies.

Previous reports suggest that HFE and HJV regulate hepcidin expression via distinct pathways (5, 15, 17, 23, 26, 32, 33). However, deleting both genes did not exacerbate the phenotype. Knocking out HJV alone effectively impairs the BMP/Smad pathway, which may lead to reduced hepcidin expression. However, whether this reduction in hepcidin expression reaches a very low level in Hjv−/− mice is unclear. Studies have shown that hepcidin expression is still detectable in Hjv−/− mice (17), which is in agreement with our findings. Moreover, inflammatory stimuli can modulate hepcidin expression in Hjv−/− mice (17), which suggests that deleting HJV does not block the entire hepcidin pathway, but may block only the BMP/Smad pathway. In addition, when Hjv−/− mice were fed an iron-rich diet (30), hepcidin expression still responded to iron loading, indicating that the mechanism by which iron modulates hepcidin is partially functional even in the absence of HJV. On the other hand, HJV might play an indispensable role in HFE-dependent signaling. A recent study showed that HJV interacts with HFE and the TfR2 (9); thus, deleting HJV may abrogate both Bmp and HFE/TfR2 signaling, thereby masking the effect of also deleting HFE in the Hfe−/−Hjv−/− double-knockout mice. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine whether the HFE/TfR2 signaling complex still responds to changes in transferrin in our knockout mice.

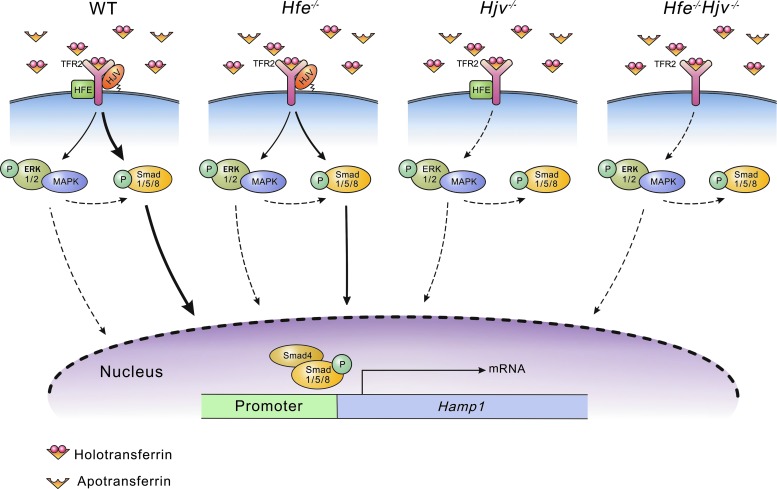

We also examined Hfe's role in our knockout mice models, as HFE was previously considered an iron sensor that contributes to hepcidin regulation. Given that our knockout mouse models develop iron overload (16, 38), it is conceivable that the basal iron status of these mice might overcome the changes in iron caused by acute iron treatment. Thus, we accounted for this possibility by inducing dietary iron deficiency (DID) in each knockout line. After consuming an iron-deficient diet for 5 weeks, the serum iron, transferrin saturation, and liver iron levels in the knockout mice were similar to—or lower than—the levels in wild-type mice that were fed a standard diet. Acutely treating the mice with oral iron had no effect on liver iron content in any of the mouse lines (Fig. 4C); therefore, we only considered the transferrin-dependent pathway in our treatment. Accordingly, we assessed the effect of acutely delivering iron to DID mice by oral gavage (8), and we found that transferrin saturation dramatically increased in all iron-treated groups (Fig. 4B). We then measured hepatic expression in the iron-treated and mock-treated groups. In the wild-type group, both Hamp1 expression and Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation were significantly increased, consistent with previous reports (8). Similarly, we also observed a significant increase in hepatic Hamp1 expression and P-Smad1/5/8 levels in the iron-treated Hfe−/− DID group (Fig. 5B, G). Moreover, a similar fold change in Hamp1 expression was induced by culturing primary Hfe−/− and wild-type hepatocytes in holo-transferrin (29), whereas Hamp1 induction by transferrin was abrogated in primary hepatocytes isolated from Hjv−/− and double-knockout mice (data not shown). These results suggest that transferrin-dependent signaling is partially preserved in the absence of HFE and is blocked completely by HJV deletion (Fig. 7). An unknown component (e.g., TfR2)—or perhaps HJV itself—would be sufficient for basal transferrin-induced hepcidin expression.

FIG. 7.

Proposed model illustrating the relationship between HJV and HFE in regulating hepcidin expression in response to an acute increase in serum iron levels. Elevated serum iron triggers the phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8, which then binds to Smad4. The P-Smad1/5/8-Smad4 complex then translocates to the nucleus, where it drives the expression of hepcidin (via the Hamp1 gene). HFE and TFR2 can sense an increase serum iron and transduce a signal that, ultimately, leads to the phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8. Our results suggest that HJV predominantly controls the phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8, and HFE activity is dependent on HJV. In our mouse models of hereditary hemochromatosis (i.e., the Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hjv−/−Hfe−/− mice), HFE deletion partially reduces P-Smad1/5/8 levels and hepcidin expression on stimulation with holotransferrin; in contrast, deleting HJV blocks this pathway completely. Moreover, crosstalk between the Erk/MAPK and Bmp/Smad pathways was previously believed to be necessary for holotransferrin-induced hepcidin expression (dashed arrows).

The Erk pathway has been reported to play a role in transferrin-mediated signaling (29). However, we have not observed any significant difference of Erk1/2 phosphorylation in four tested mouse lines (Fig. 6A, B). We found P-Erk1/2 levels peaked at 5-min time point in holotransferrin-treated primary cultured hepatocytes in all four mouse lines (Fig. 6C). These observations indicate that the holotransferrin-induced activation of MAPK-Erk pathway might not be the main downstream pathways of either HFE or HJV, since the pathway can be activated even without either HFE or HJV. To avoid any potential artifacts due to transferrin, cytokines, and/or iron in the serum, we used serum-free cell culture medium as a control. As previously reported, P-Erk1/2 levels in serum-treated hepatocytes were also increased but weaker than holotransferrin+serum-treated hepatocytes (29). Nevertheless, this previous study also reported that an MEK inhibitor reduced Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation (29). Thus, the activation of MAPK might occur via another branch of the transferrin-TfR2 signaling pathway.

In this model (Fig. 7), when iron enters the circulation, apo-transferrin binds to ferric ions, creating holotransferrin. Holotransferrin then interacts with HFE/TFR2 (and possibly with HJV as well), triggering the phosphorylation of MAPK/Erk and Smad1/5/8. Our experiments show that MAPK/Erk might not play a key regulatory role in Hamp1 expression, whereas P-Smad1/5/8 forms a complex with Smad4, translocates to the nucleus, and drives Hamp1 transcription. In the Hfe-knockout line (depicted in the second model), the holotransferrin-induced signal remains less changed; however, because of the loss of HFE, the P-Smad1/5/8 signal is considerably weakened, and as a result, Hamp1 expression in Hfe−/− mice is lower than wild-type expression. In the Hjv-knockout line (depicted in the third model), the holotransferrin signal cannot reach downstream signaling events; thus, even in the presence of HFE, Hamp1 expression cannot proceed normally. This finding that transferrin-dependent signaling is absent in Hjv−/− mice underscores the importance of HJV in transferrin-dependent signaling. Finally, the HFE/HJV double-knockout mice (depicted in the fourth model) have similar signaling properties as the HJV single-knockout mice.

In summary, our findings add to our current knowledge with respect to the relationship between HFE and HJV. Although additional studies are warranted, our in vivo studies suggest that HJV is a key regulator that is necessary for HFE to increase hepcidin expression.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Hfe−/− mice and Hjv−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. Nancy C. Andrews (11, 17). Both strains were maintained on a 129/SvEvTac background. Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice were generated by crossing the Hfe−/− and Hjv−/− mice. Unless stated otherwise, the mice were fed a standard rodent laboratory diet (containing 232 mg iron/kg) obtained from SLRC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute for Nutritional Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Serum iron and tissue non-heme iron measurements

Serum iron and tissue non-heme iron were measured as previously described (34, 39).

Tissue iron staining

Tissue iron was detected in Bouin's solution-fixed liver and spleen sections using Perls Prussian blue staining. Slides were viewed using an Olympus IX51 microscope, and images were captured using an Olympus DP70 digital camera (37).

Induction of a DID model and acute iron administration

Three-week-old Hfe−/− mice were fed a standard diet for 2 weeks, after which they were fed an iron-deficient diet for 3 weeks. Hjv−/− and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice were fed an iron-deficient diet for 5 weeks starting when they were weaned. The iron-deficient diet (containing 0.9 mg iron/kg) was the egg white-based AIN-76A-diet (Research Diets) (40). The DID mice and control diet-fed mice then received either 2 mg of elemental iron per kg body weight in the form of iron sulfate (Sigma) in 200 μl distilled water (iron-treated groups) or 200 μl distilled water alone (mock groups) by oral gavage; the mice were sacrificed 4 h after gavage, and serum and tissue samples were collected for analysis.

Primary hepatocyte culture and treatment

Hepatocytes were isolated from 8-week-old male wild-type (129/SvEvTac), Hfe−/−, Hjv−/−, and Hfe−/−Hjv−/− mice using the collagenase isolation method as previously described (38). Hepatocytes were seeded in six-well plates at 1×106 cells per well. After the cells attached to the surface, the media was changed to fresh serum-free M199 media, and the cells were incubated for 42 h. Hepatocytes were then incubated with fresh media containing no serum (control), 10% fetal calf serum, 30 μM human holotransferrin (Sigma), or both 10% fetal calf serum and 30 μM human holotransferrin. Where indicated, the Erk inhibitor U0-126 (Cell Signaling) was added to a final concentration of 10 μM 1 h before the serum and/or holotransferrin treatment.

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the liver using Trizol (Invitrogen). Primer pairs were then used to detect iron-related mRNA transcripts (Table 1). Real-time PCR was performed using the two-step quantitative RT-PCR method as previously described (7), and target gene expression was normalized to β-actin mRNA levels.

Table 1.

Sequences of Oligonucleotide Primers Used for Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Actin | 5′-AAA TCG TGC GTG ACA TCA AAG A-3′ | 5′-GCC ATC TCC TGC TCG AAG TC-3′ |

| Hamp1 | 5′-GCA CCA CCT ATC TCC ATC AAC A-3′ | 5′-TTC TTC CCC GTG CAA AGG-3′ |

| Id1 | 5′-CGC AGC CAC CGG ACT CT-3′ | 5′-AAC CCC CTC CCC AAA GTC T-3′ |

| Smad7 | 5′-TTC GGA CAA CAA GAG TCA GC-3′ | 5′-GGT AAC TGC TGC GGT TGT AA-3′ |

| Bmp6 | 5′-ATG GCA GGA CTG GAT CAT TGC-3′ | 5′-CCA TCA CAG TAG TTG GCA GCG-3′ |

Western blot analysis

Samples were prepared and analyzed using Western blot as previously described (39). Anti-phospho-Smad1/5/8 (1:1000; Cell Signaling), anti-Smad1 (1:1000; Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-Erk1/2 (1:1000; Cell Signaling), anti-Erk1/2 (1:1000; Cell Signaling), anti-TfR1 (1:500), and anti-β-actin (1:2000; Sigma) were used as the primary antibodies.

Statistical analysis

All summary data are expressed as the mean±standard error of the mean (n=8–10 mice/group). To compare multiple groups (i.e., >2 groups), we first used Bartlett's test to check the homogeneity of variance. For multiple groups with unequal variance, the data were log10-transformed to meet the assumption of homogeneity of variance, and then an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. To compare two groups, differences were analyzed using the Student's t-test, and differences were considered statistically significant when p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the R software package.

Abbreviations Used

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- DID

dietary-induced iron deficiency

- Erk

extracellular signal regulated kinase

- Fpn1

ferroportin1

- HAMP1

hepcidin antimicrobial peptide 1

- HFE

hemochromatosis protein

- HH

hereditary hemochromatosis

- HIC

hepatic iron content

- HJV

hemojuvelin

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- P-Erk

phosphorylated Erk

- P-SMAD1/5/8

phosphorylated Smad1/5/8

- RBC

red blood cell

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SMAD

mothers against decapentaplegic homolog proteins

- STAT3

signal transducers and activators of transcription 3

- Tf

transferrin

- TfR1

transferrin receptor 1

- TfR2

transferrin receptor 2

- WT

wild-type

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Nancy C. Andrews for generously providing the Hfe and Hjv knockout mice. This study was supported by research grants from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2011CB966200 and 2012BAD33B05 to F.W.), the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (31225013, 31330036, and 31030039 to F.W.), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Z15H160009 to J.M.), and the Distinguished Professorship Program from Zhejiang University (to F.W.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ahmad KA, Ahmann JR, Migas MC, Waheed A, Britton RS, Bacon BR, Sly WS, and Fleming RE. Decreased liver hepcidin expression in the Hfe knockout mouse. Blood Cells Mol Dis 29: 361–366, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews NC. Forging a field: the golden age of iron biology. Blood 112: 219–230, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andriopoulos B, Jr., Corradini E, Xia Y, Faasse SA, Chen S, Grgurevic L, Knutson MD, Pietrangelo A, Vukicevic S, Lin HY, and Babitt JL. BMP6 is a key endogenous regulator of hepcidin expression and iron metabolism. Nat Genet 41: 482–487, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armitage AE, Eddowes LA, Gileadi U, Cole S, Spottiswoode N, Selvakumar TA, Ho LP, Townsend AR, and Drakesmith H. Hepcidin regulation by innate immune and infectious stimuli. Blood 118: 4129–4139, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Wrighting DM, Xia Y, Sidis Y, Samad TA, Campagna JA, Chung RT, Schneyer AL, Woolf CJ, Andrews NC, and Lin HY. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling by hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression. Nat Genet 38: 531–539, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridle KR, Frazer DM, Wilkins SJ, Dixon JL, Purdie DM, Crawford DH, Subramaniam VN, Powell LW, Anderson GJ, and Ramm GA. Disrupted hepcidin regulation in HFE-associated haemochromatosis and the liver as a regulator of body iron homoeostasis. Lancet 361: 669–673, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, and Wittwer CT. The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55: 611–622, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corradini E, Meynard D, Wu Q, Chen S, Ventura P, Pietrangelo A, and Babitt JL. Serum and liver iron differently regulate the bone morphogenetic protein 6 (BMP6)-SMAD signaling pathway in mice. Hepatology 54: 273–284, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Alessio F, Hentze MW, and Muckenthaler MU. The hemochromatosis proteins hfe, tfr2 and hjv form a membrane-associated protein complex for hepcidin regulation. J Hepatol 57: 1052, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feder JN, Gnirke A, Thomas W, Tsuchihashi Z, Ruddy DA, Basava A, Dormishian F, Domingo R, Jr., Ellis MC, Fullan A, Hinton LM, Jones NL, Kimmel BE, Kronmal GS, Lauer P, Lee VK, Loeb DB, Mapa FA, McClelland E, Meyer NC, Mintier GA, Moeller N, Moore T, Morikang E, Prass CE, Quintana L, Starnes SM, Schatzman RC, Brunke KJ, Drayna DT, Risch NJ, Bacon BR, and Wolff RK. A novel MHC class I-like gene is mutated in patients with hereditary haemochromatosis. Nat Genet 13: 399–408, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finberg KE, Whittlesey RL, and Andrews NC. Tmprss6 is a genetic modifier of the Hfe-hemochromatosis phenotype in mice. Blood 117: 4590–4599, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleming RE. Iron sensing as a partnership: HFE and transferrin receptor 2. Cell Metab 9: 211–212, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganz T. Hepcidin and iron regulation, 10 years later. Blood 117: 4425–4433, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganz T. and Nemeth E. Hepcidin and disorders of iron metabolism. Annu Rev Med 62: 347–360, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao J, Chen J, Kramer M, Tsukamoto H, Zhang AS, and Enns CA. Interaction of the hereditary hemochromatosis protein HFE with transferrin receptor 2 is required for transferrin-induced hepcidin expression. Cell Metab 9: 217–227, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, and Camaschella C. Two to tango: regulation of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 142: 24–38, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang FW, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Fleming MD, and Andrews NC. A mouse model of juvenile hemochromatosis. J Clin Invest 115: 2187–2191, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jomova K. and Valko M. Importance of iron chelation in free radical-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Curr Pharm Des 17: 3460–3473, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kautz L, Meynard D, Besson-Fournier C, Darnaud V, Al Saati T, Coppin H, and Roth MP. BMP/Smad signaling is not enhanced in Hfe-deficient mice despite increased Bmp6 expression. Blood 114: 2515–2520, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krause A, Neitz S, Magert HJ, Schulz A, Forssmann WG, Schulz-Knappe P, and Adermann K. LEAP-1, a novel highly disulfide-bonded human peptide, exhibits antimicrobial activity. FEBS Lett 480: 147–150, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krijt J, Niederkofler V, Salie R, Sefc L, Pelichovska T, Vokurka M, and Necas E. Effect of phlebotomy on hepcidin expression in hemojuvelin-mutant mice. Blood Cells Mol Dis 39: 92–95, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Gac G, Scotet V, Ka C, Gourlaouen I, Bryckaert L, Jacolot S, Mura C, and Ferec C. The recently identified type 2A juvenile haemochromatosis gene (HJV), a second candidate modifier of the C282Y homozygous phenotype. Hum Mol Genet 13: 1913–1918, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lebron JA, Bennett MJ, Vaughn DE, Chirino AJ, Snow PM, Mintier GA, Feder JN, and Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure of the hemochromatosis protein HFE and characterization of its interaction with transferrin receptor. Cell 93: 111–123, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee P, Peng H, Gelbart T, Wang L, and Beutler E. Regulation of hepcidin transcription by interleukin-1 and interleukin-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 1906–1910, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicolas G, Bennoun M, Devaux I, Beaumont C, Grandchamp B, Kahn A, and Vaulont S. Lack of hepcidin gene expression and severe tissue iron overload in upstream stimulatory factor 2 (USF2) knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 8780–8785, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nili M, Shinde U, and Rotwein P. Soluble repulsive guidance molecule c/hemojuvelin is a broad spectrum bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) antagonist and inhibits both BMP2- and BMP6-mediated signaling and gene expression. J Biol Chem 285: 24783–24792, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papanikolaou G, Samuels ME, Ludwig EH, MacDonald ML, Franchini PL, Dube MP, Andres L, MacFarlane J, Sakellaropoulos N, Politou M, Nemeth E, Thompson J, Risler JK, Zaborowska C, Babakaiff R, Radomski CC, Pape TD, Davidas O, Christakis J, Brissot P, Lockitch G, Ganz T, Hayden MR, and Goldberg YP. Mutations in HFE2 cause iron overload in chromosome 1q-linked juvenile hemochromatosis. Nat Genet 36: 77–82, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poli M, Luscieti S, Gandini V, Maccarinelli F, Finazzi D, Silvestri L, Roetto A, and Arosio P. Transferrin receptor 2 and HFE regulate furin expression via mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/Erk) signaling. Implications for transferrin-dependent hepcidin regulation. Haematologica 95: 1832–1840, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramey G, Deschemin JC, and Vaulont S. Cross-talk between the mitogen activated protein kinase and bone morphogenetic protein/hemojuvelin pathways is required for the induction of hepcidin by holotransferrin in primary mouse hepatocytes. Haematologica 94: 765–772, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramos E, Kautz L, Rodriguez R, Hansen M, Gabayan V, Ginzburg Y, Roth MP, Nemeth E, and Ganz T. Evidence for distinct pathways of hepcidin regulation by acute and chronic iron loading in mice. Hepatology 53: 1333–1341, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roetto A, Papanikolaou G, Politou M, Alberti F, Girelli D, Christakis J, Loukopoulos D, and Camaschella C. Mutant antimicrobial peptide hepcidin is associated with severe juvenile hemochromatosis. Nat Genet 33: 21–22, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt PJ, Andrews NC, and Fleming MD. Hepcidin induction by transgenic overexpression of Hfe does not require the Hfe cytoplasmic tail, but does require hemojuvelin. Blood 116: 5679–5687, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt PJ, Toran PT, Giannetti AM, Bjorkman PJ, and Andrews NC. The transferrin receptor modulates Hfe-dependent regulation of hepcidin expression. Cell Metab 7: 205–214, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torrance JD. and Bothwell TH. Tissue iron stores. In: Methods in Hematology: Iron, edited by Cook JD. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1980, pp. 90–115 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Truksa J, Peng H, Lee P, and Beutler E. Bone morphogenetic proteins 2, 4, and 9 stimulate murine hepcidin 1 expression independently of Hfe, transferrin receptor 2 (Tfr2), and IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 10289–10293, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verga Falzacappa MV, Vujic Spasic M, Kessler R, Stolte J, Hentze MW, and Muckenthaler MU. STAT3 mediates hepatic hepcidin expression and its inflammatory stimulation. Blood 109: 353–358, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace DF, Summerville L, Crampton EM, Frazer DM, Anderson GJ, and Subramaniam VN. Combined deletion of Hfe and transferrin receptor 2 in mice leads to marked dysregulation of hepcidin and iron overload. Hepatology 50: 1992–2000, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Q, Jiang L, Wang J, Li S, Yu Y, You J, Zeng R, Gao X, Rui L, Li W, and Liu Y. Abrogation of hepatic ATP-citrate lyase protects against fatty liver and ameliorates hyperglycemia in leptin receptor-deficient mice. Hepatology 49: 1166–1175, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Z, Zhang F, An P, Guo X, Shen Y, Tao Y, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Yu Y, Ning B, Nie G, Knutson MD, Anderson GJ, and Wang F. Ferroportin1 deficiency in mouse macrophages impairs iron homeostasis and inflammatory responses. Blood 118: 1912–1922, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z, Zhang F, Guo X, An P, Tao Y, and Wang F. Ferroportin1 in hepatocytes and macrophages is required for the efficient mobilization of body iron stores in mice. Hepatology 56: 961–971, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou XY, Tomatsu S, Fleming RE, Parkkila S, Waheed A, Jiang J, Fei Y, Brunt EM, Ruddy DA, Prass CE, Schatzman RC, O'Neill R, Britton RS, Bacon BR, and Sly WS. HFE gene knockout produces mouse model of hereditary hemochromatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 2492–2497, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]