Abstract

Objective To assess the benefits and risks of short term (<12 months) or extended (>12 months) dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) versus standard 12 month therapy, following percutaneous coronary intervention with drug eluting stents.

Design Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources PubMed, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and major congress proceedings, searched from 1 January 2002 to 16 February 2015.

Review methods Trials comparing short term (<12 months) or extended (>12 months) DAPT regimens with standard 12 month duration of therapy. Primary outcomes were cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, major bleeding, and all cause mortality.

Results 10 randomised controlled trials (n=32 287) were included. Compared to 12 month DAPT, a short term course of therapy was associated with a significant reduction in major bleeding (odds ratio 0.58 (95% confidence interval 0.36 to 0.92); P=0.02) with no significant differences in ischaemic or thrombotic outcomes. Extended versus 12 month DAPT yielded a significant reduction in the odds of myocardial infarction (0.53 (0.42 to 0.66); P<0.001) and stent thrombosis (0.33 (0.21 to 0.51); P<0.001), but more major bleeding (1.62 (1.26 to 2.09); P<0.001). All cause but not cardiovascular death was also significantly increased (1.30 (1.02 to 1.66); P=0.03).

Conclusions Compared with a standard 12 month duration, short term DAPT (<12 months) after drug eluting stent implementation yields reduced bleeding with no apparent increase in ischaemic complications, and could be considered for most patients. In selected patients with low bleeding risk and very high ischaemic risk, extended DAPT (>12 months) could be considered. The increase in all cause but not cardiovascular death with extended DAPT requires further investigation.

Introduction

Drug eluting stents have consistently improved the safety and efficacy of percutaneous coronary intervention as compared with bare metal stents.1 2 3 4 While drug eluting stents have reduced in-stent restenosis, uncertainty has arisen regarding the risk of associated late and very late stent thrombosis. Dual antiplatelet therapy consisting of aspirin plus a P2Y12 receptor antagonist is recommended after drug eluting stent implantation for at least 12 months by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and for six to 12 months by European guidelines,5 6 followed by aspirin monotherapy. Current recommendations, however, are based largely on observational data with few randomised controlled trials.

The most recent trials and meta-analyses have suggested comparable efficacy of short term dual antiplatelet therapy versus therapy of at least 12 months, especially with newer generation drug eluting stents,7 8 9 but these studies are underpowered to draw definitive conclusions. On the other hand, very late stent thrombosis still occurs with drug eluting stents, especially after first generation devices, raising the question of whether prolongation of dual antiplatelet therapy offers clinical benefit. One randomised controlled trial recently showed a significant reduction of stent thrombosis with dual antiplatelet therapy extended beyond 12 months at the price of increased bleeding.10 Thus, the optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy is debated, with short term and extended protocols not yet compared to standard 12 month treatment within the same trial. We aimed to perform a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials to compare the efficacy and safety of short term and extended dual antiplatelet therapy with standard 12 month therapy.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

Established methods were used in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement in healthcare interventions.11 We screened Medline, Embase, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Scopus, Web of Science, the Cochrane Register of Controlled Clinical Trials, as well as congress proceedings from major cardiac societies, for randomised data comparing different durations of dual antiplatelet therapy. Dual antiplatelet therapy was defined as aspirin plus a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, after percutaneous coronary intervention with implantation of a drug eluting stent. The search period took place from 1 January 2002 to 16 February 2015.

Search terms according to medical subjects headings were: “DAPT”, “dual antiplatelet therapy”, “clopidogrel”, “Plavix”, “prasugrel”, “Efient”, “ticagrelor”, “Brilinta”, “thienopyridine”, “P2Y12”, “shortened DAPT”, “prolonged DAPT”, “extended DAPT”, “premature cessation”, “early discontinuation”, “randomised trial”, and “trial”. No language or publication status restriction was imposed. The most updated or inclusive data for each study were used for abstraction. In addition, landmark analysis data at 12 months were available from the original PROlonging Dual antIplatelet treatment after Grading stent-induced intimal hyperplasia studY (PRODIGY)7 and were therefore incorporated into the present article.

Study design and selection criteria

The design of the current meta-analysis compared two strategies of dual antiplatelet therapy involving three durations after percutaneous coronary intervention with drug eluting stent implantation. The first comparison was between a short term (<12 months) and 12 month therapy, and the second between an extended duration (>12 months) and 12 month therapy. The original PRODIGY randomised controlled trial7 assigned patients to either six or 24 month durations. Because the randomisation process in PRODIGY began one month after the index percutaneous coronary intervention, the availability of landmark data at 12 months allowed inclusion of the study in the short term versus 12 month comparison, after censoring events that occurred after 12 months and keeping the original randomisation design. We did additional sensitivity analyses by including PRODIGY trial data in the extended duration versus 12 month comparison. The analyses included only events that occurred beyond 12 months in both study arms (postrandomisation subgroups).

The main exclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were: observational design, patients without documented coronary artery disease or patients with peripheral or cerebrovascular disease, percutaneous coronary intervention without stents or with bare metal stents only, and duration timeframes of dual antiplatelet therapy selected by the meta-analysis not reported. Two independent reviewers (VS and MK) selected the studies for inclusion and extracted the study characteristics and relevant outcomes; divergences were solved by consensus after discussion with a third reviewer (EPN). Three authors (EPN, MK, and VS) independently reassessed the trials’ eligibility and ranked their risk of bias. Risk of bias was graded using the components recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration—that is, random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias.12

Outcome measures

Primary clinical endpoints were cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, major bleeding, and overall mortality; secondary endpoints were repeat revascularisation, and cerebrovascular accident, and the combination of cardiac and cerebrovascular accidents. We classified stent thrombosis as definite/probable, definite, late (between 30 days and one year after percutaneous coronary intervention), and very late (>one year after percutaneous coronary intervention) according to criteria from the Academic Research Consortium.13 For major bleeding, trial definitions were applied. Major bleeding according to TIMI criteria,14 and a composite endpoint of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular accidents were also assessed.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed according to the intention to treat principle. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were used as summary statistics. Heterogeneity was assessed by Cochran’s Q test.15 We also used the statistical inconsistency test (I2=(Q−df)/Q×100%, where Q=χ2 statistic and df=its degrees of freedom) to overcome the low statistical power of Cochran’s Q test. Pooled odds ratios were calculated using a fixed effect model with the Mantel-Haenszel method, because of the absence of moderate or significant inconsistency (>50%) across studies. We also did prespecified sensitivity analyses using a random effects model. Potential publication bias was examined by constructing funnel plots for the clinical outcomes in which the standard error of the log of the odds ratio was plotted against the odds ratio. The asymmetry of the plot was estimated both visually and by Harbord’s regression test.16 Prespecified analyses assessed the effect of different durations of dual antiplatelet therapy in the following subgroups: age older than 65 years or younger than 65 years, patients with or without acute coronary syndrome, and those treated with either clopidogrel or new P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel and ticagrelor). P<0.05 was considered significant and reported as two sided.

Results

Studies and patients

The PRISMA statement flowchart (web fig 1) describes the literature screening, study selection, and reasons for exclusion. From 338 initial studies, 295 were discarded at title or abstract level. Another 33 studies did not meet the prespecified inclusion criteria and were therefore excluded. A total of 10 randomised controlled trials (n=32 287)7 8 10 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 were finally included in the meta-analysis. Tables 1 and 2 list the characteristics and references of the included studies. Web figure 2 summarises the quality of included studies, along with potential sources of bias. Web table 1 outlines the full electronic Medline search process. No publication bias was suggested by the funnel plots (web figs 3-8) and by Harbord’s regression test (web table 7). Seven studies tested short term regimens (<12 months) of dual antiplatelet therapy against 12 months’ duration (table 1),7 8 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 and three studies tested extended regimens (>12 months; table 2).10 17 18 19 20 21

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies comparing short term (<12 month) versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Primary endpoints | Secondary endpoints | Time to randomisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXCELLENT22 (2012), n=1443, 6 months v 12 months of DAPT duration | ||||

| ≥1 de novo lesion; native coronary vessel; RVD ≥2.25-4.25 mm; >50% DS; stable angina, unstable angina, recent MI, silent ischaemia, positive functional study, or reversible changes on ECG consistent with ischaemia | <72 h MI; <25% LVEF or cardiogenic shock; any stent implantation in target vessel before enrolment; major bleeding <3 months; major surgery <2 months; elective surgery planned <12 months; >50% DS on LM; CTO; true bifurcation lesions requiring a planned two stent strategy | Target vessel failure (composite of cardiac death, MI, or ID-TVR) | Cardiac death; MI; ID-TVR; all cause death; death or MI; ST; TIMI14 major bleeding; MACCE (composite of death, MI, stroke, or any revascularisation); safety endpoint (composite of death, MI, stroke, ST, or TIMI major bleeding) | At index PCI |

| ISAR-SAFE23 (2014), n=4005, 6 months v 12 months of DAPT duration | ||||

| Patients on clopidogrel at 6 (−1/+2) months after PCI with DES; written informed consent | Clinical symptoms or signs of ischaemia or angiographic lesions requiring revascularisation; active bleeding; bleeding diathesis; history of intracranial bleeding; STEMI and NSTEMI during last 6 months after DES; previous ST; DES in LM at index intervention; oral anticoagulation; planned major surgery within next 6 months with need to discontinue APT | Composite of death, MI, ST, stroke, or TIMI major bleeding | Composite of death, MI, ST, stroke; TIMI major and minor bleeding; death; MI; ST; stroke; TIMI major bleeding; BARC bleeding ≥class 2 | 6 months after index PCI |

| ITALIC28 (2014), n=1850, 6 months v 12 months of DAPT duration | ||||

| Patients ≥18 years old, eligible for PCI, with ≥1 Xience V DES (Abbott Vascular Devices, Santa Clara, CA, USA) implanted, in all clinical situations excluding primary PCI for acute MI and treatment of LM | Patients non-responders to aspirin; previous DES implantation within 1 year; known platelet level <100 000/μL or known haemorrhagic diathesis; oral anticoagulation therapy or abciximab treatment during hospital stay; contraindications to aspirin or clopidogrel (prasugrel or ticagrelor); major surgery within preceding 6 weeks; evidence of active gastrointestinal or urogenital bleeding; severe liver failure; any surgery scheduled within 1 year after enrolment; or severe concomitant disease with <2 years’ life expectancy | Composite of death, MI, repeat emergency revascularisation, stroke, or major bleeding | Composite at 24 and 36 months, death, MI, or repeat emergency revascularisation, and stroke requiring readmission | At index PCI |

| OPTIMIZE24,25 (2013), n=3211, 3 months v 12 months of DAPT duration | ||||

| Stable angina or silent ischaemia or low risk ACS as defined by unstable angina or recent (but not acute) myocardial infarction (<30 days) | Elevated biomarker levels at time of index procedure and ≥1 lesion with stenosis >50% (MVD allowed) located in a native vessel >2.5 mm diameter with indication for PCI with stent implantation; STEMI presenting for primary or rescue PCI; PCI with BMS in non-target lesions <6 months before index procedure; previous treatment with any DES; scheduled elective surgery within 12 months after index procedure; contraindication, intolerance, or known hypersensitivity to aspirin, clopidogrel, or both; lesion in a saphenous vein graft; or in-stent restenosis of DES | Net adverse clinical and cerebral events (composite of all cause death, MI, stroke, or major bleeding) | ST according to ARC; target lesion and target vessel revascularisation; MACE (including all cause death, MI, emergent CABG surgery, or target lesion revascularisation); and any bleeding, including major bleeding and bleeding events that did not meet criteria for major or severe or life threatening bleeding (according to modified major REPLACE-2 and severe or life threatening GUSTO criteria) | At index PCI |

| PRODIGY7,26 (2012), n=1970, 6 months v 24 months of DAPT duration* | ||||

| ≥18 years old; ≥1 coronary artery lesion; >50% DS; PCI suitability; RVD ≥2.25 mm; chronic stable coronary artery disease or ACS (NSTEMI or STEMI) | Elective surgery planned 24 months after index PCI (unless DAPT could be maintained during perisurgical period); bleeding diathesis; major surgery <15 days; active bleeding or previous stroke <6 months; concomitant or foreseeable need for anticoagulants | Composite of all cause death, MI, or CVA | All cause death; MI; CVA; cardiac death; ST; bleeding | 1 month after index PCI |

| RESET27 (2012), n=2117, 3 months v 12 months of DAPT duration | ||||

| 20-85 years old; ≥50% DS; RVD ≥2.5-4.0 mm; elective PCI; stable or unstable angina, or acute MI | Cerebral or peripheral atherosclerotic arterial disease, thromboembolic disease or ST history; <40% LVEF; restenotic lesion; CTO; LM disease requiring intervention; cardiogenic shock; <48 h STEMI | Composite of cardiac death, MI, ST, ID-TVR, and TIMI major or minor bleeding | Composite of all cause death, MI and ST, cardiac death, MI, ST, ID-TVR and TIMI14 major or minor bleeding | At index PCI |

| SECURITY8 (2014), n=1399, duration 6 months v 12 months of DAPT duration | ||||

| >18 years old; stable angina, as defined by CCS or unstable angina, as defined by Braunwald classification, or patients with documented silent ischaemia, treated with ≥1 second generation DES implanted in the target lesion in past 24 h; presence of ≥1 de novo stenosis ≥70% in a native coronary artery; no other DES implanted before target procedure and no BMS implanted in 3 months before target procedure | STEMI in 48 h before the procedure, NSTEMI in previous 6 months; LVEF <30%; known hypersensitivity to aspirin, thienopyridines, heparin, limus analogues, cobalt, chromium, nickel, molybdenum, or contrast media; target lesion in saphenous vein graft, in-stent restenosis, unprotected LM; history of significant thrombocytopenia with aspirin or thienopyridines; patients with chronic kidney disease (creatinine >2 mg/dL†); women during pregnancy or lactation; active bleeding or significant risk of bleeding; uncontrolled hypertension; life expectancy <24 months and any medical condition that could preclude follow-up as defined in protocol | Composite of cardiac death, MI, stroke, definite or probable ST or BARC type 3 or 5 bleeding | Composite of cardiac death, spontaneous MI, stroke, definite or probable stent thrombosis, or BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding at 12 and 24 months (cumulative incidence of individual components of the primary endpoint); MI, urgent target vessel revascularisation (CABG or PCI because of acute cardiac ischaemia), all bleeding events and all cause mortality | At index PCI |

Data classified by study name (year), no of patients, and comparison of DAPT durations after index percutaneous coronary intervention. DAPT=dual antiplatelet therapy; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; DES=drug eluting stent; STEMI=ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; MI=myocardial infarction; ST=stent thrombosis; BMS=bare-metal stent; MACCE=major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; GUSTO=global utilization of streptokinase and TPA for occluded arteries; CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting; BARC=Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; MACE=major adverse cardiovascular events; ACS=acute coronary syndrome; RVD=reference vessel diameter; ECG=electrocardiogram; LVEF=left ventricle ejection fraction; DS=diameter stenosis; LM=left main artery; CTO=chronic total occlusion; ID-TVR=ischaemia driven target vessel revascularisation; NSTEMI=non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; APT=antiplatelet therapy; MVD=multivessel disease; ARC=Academic Research Consortium; REPLACE-2=randomized evaluation in PCI linking angiomax to reduced clinical events; CVA=cerebrovascular accidents; CCS=Canadian Cardiovascular Society.

*Available landmark data at 12 and 12-24 months.

†1 mg/dL=88.4 µmol/L.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies comparing extended (>12 month) versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Primary endpoints | Secondary endpoints | Time to randomisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARCTIC Interruption17,18 (2014), n=1286, 12 months v 18 months of DAPT duration* | ||||

| ≥18 years and eligible for PCI with planned use of ≥1 DES; without use of a GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor at randomisation; able to understand study requirements and comply with study procedures and protocol | Anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists; contraindication to aspirin or clopidogrel, GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors, or increased dose regimen of aspirin/clopidogrel; ongoing or recent bleeding or major surgery <3 weeks; severe liver insufficiency; thrombocytopenia <80 000/μL; GPIIb/IIIa inhibitor before randomisation; primary PCI for STEMI; history of major bleeding with contraindication to APT; scheduled surgery <12 months; high risk feature of poor compliance to DAPT | Composite of all cause death, MI, stroke or TIA, urgent coronary revascularisation, and ST | Composite of ST (whether revascularised or not) and urgent revascularisation, all cause death, MI, stroke or TIA, urgent coronary revascularisation, and ST; main safety endpoint was STEEPLE major bleeding | 12 months after index PCI |

| DAPT10,19 (2014), n=9961, 12 months v 30 months of DAPT duration | ||||

| >18 years old, undergoing percutaneous intervention with stent deployment | Index procedure stent placement with stent diameter <2.25 mm or >4.0 mm; pregnancy; planned surgery necessitating discontinuation of APT within 30 months after enrollment; life expectancy of <3 years; enrollment in another device or drug study whose protocol specifically rules out concurrent enrollment or involves blinded placement of a DES or BMS other than those included as DAPT study devices; warfarin or similar anticoagulant therapy; hypersensitivity or allergies to one of the drugs or DES components; patient treated with both DES and BMS during index procedure | Definite/probable ST and MACCE defined as composite of death, MI or stroke | Moderate or severe bleeding according to GUSTO14 classification; clinically actionable non-CABG related bleeding according to BARC (type 2, 3, and 5); MI, stroke, cardiac and vascular mortality | 12 months after index PCI |

| DES LATE20,21 (2010), n=5045, 12 months v 24 months of DAPT duration | ||||

| <12 months DES implantation; no MACE (MI, stroke, repeat PCI) or major bleeding since PCI; DAPT on board | DAPT contraindications due to bleeding diathesis or major bleeding history; long term DAPT indication due to concomitant vascular disease or recent ACS | MI or cardiac death | All cause death; MI, stroke; ST; repeat revascularisation; composite of MI or all cause death; composite of MI, stroke, or all cause death; composite of MI, stroke, or cardiac death; TIMI14 major bleeding | 12 months after index PCI |

Data classified by study name (year), no of patients, and comparison of DAPT durations after index percutaneous coronary intervention. DAPT=dual antiplatelet therapy; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; DES=drug eluting stent; GP=glycoprotein; STEMI=ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; APT=antiplatelet therapy; MI=myocardial infarction; ST=stent thrombosis; TIA=transient ischaemic attack; STEEPLE=the safety and efficacy of enoxaparin in PCI patients, an international randomized evaluation; BMS=bare-metal stent; MACCE=major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; GUSTO=global utilization of streptokinase and TPA for occluded arteries; CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting; BARC=Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; MACE=major adverse cardiovascular events; ACS=acute coronary syndrome.

*Available landmark data at 12 and 12-24 months.

Clopidogrel and aspirin was the most frequent drug combination in dual antiplatelet therapy; prasugrel or ticagrelor were available in three8 10 17 18 19 and two8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 studies, respectively. Of 32 287 patients, 7975 were randomly allocated to short term regimens and 8196 to extended regimens of dual antiplatelet therapy; 16 116 patients constituted the 12 month control group. Web table 2 lists the patients’ baseline characteristics. Patients presented evenly, with either stable angina/silent ischaemia or non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (48% and 45%, respectively); fewer than 10% presented with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Web table 3 lists procedural characteristics of each study. Web table 4 lists definitions of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events.

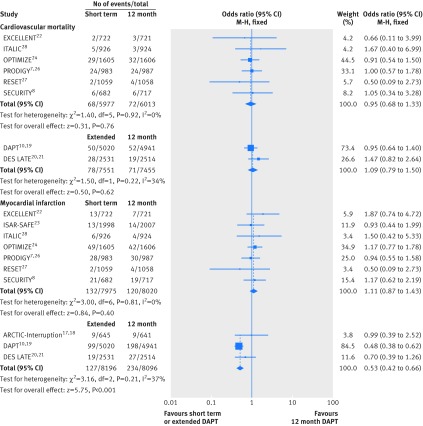

Cardiovascular mortality and myocardial infarction

Eight studies including 26 996 patients provided data for cardiovascular mortality. Cardiovascular mortality after short term and 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy did not differ significantly (event rate 1.13% (68/5997 patients) v 1.20% (72/6013); odds ratio 0.95 (95% confidence interval 0.68 to 1.33); P=0.76; I2=0%; fig 1). Similarly, cardiovascular mortality did not differ significantly between extended dual antiplatelet therapy and 12 month therapy (1.03% (78/7551) v 0.95% (71/7455); 1.09 (0.79 to 1.50); P=0.62; I2=34%; fig 1).

Fig 1 Individual and summary odds ratios for the endpoints of cardiovascular mortality and myocardial infarction. M-H=Mantel-Haenszel. Data stratified by duration of dual antiplatelet therapy: short term (<12 months) versus 12 months, and extended (>12 months) versus 12 months

All 10 randomised controlled trials (n=32 287) were included in the myocardial infarction analysis. Myocardial infarction rates were similar in patients randomised to either short term or 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy (1.65% (132/7975 patients) v 1.50% (120/8020); odds ratio 1.11 (95% confidence interval 0.87 to 1.43); P=0.40; I2=0%; fig 1). We saw a reduction of roughly 50% in the odds of myocardial infarction with extended dual antiplatelet therapy, compared with 12 month therapy (1.55% (127/8196) v 2.89% (234/8096); 0.53 (0.42 to 0.66); P<0.001; I2=37%; fig 1).

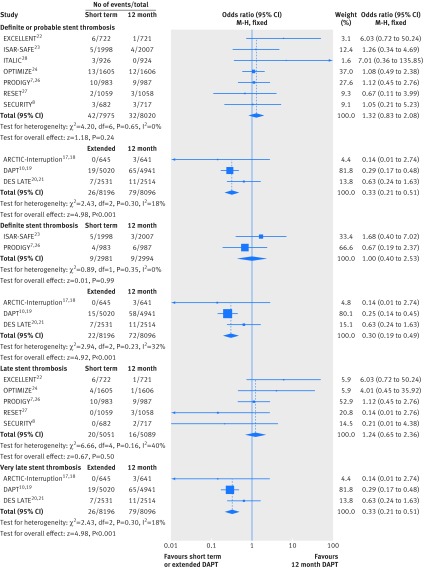

Stent thrombosis

All 10 studies (n=32 287) contributed to the analysis of definite/probable stent thrombosis (fig 2). We saw no significant difference in the rates of stent thrombosis when comparing short term dual antiplatelet therapy with 12 month therapy (0.53% (42/7975 patients) v 0.40% (32/8020); odds ratio 1.32 (95% confidence interval 0.83 to 2.08); P=0.24; I2=0%). Similarly, the analysis of definite stent thrombosis demonstrated identical rates (0.3%) for both short term and 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy (1.00 (0.40 to 2.53); P=0.99; I2=0%; fig 2).

Fig 2 Individual and summary odds ratios for the endpoints of definite/probable stent thrombosis and definite stent thrombosis, and analysis of late and very late stent thrombosis. Data stratified by duration of dual antiplatelet therapy: short term (<12 months) versus 12 months, and extended (>12 months) versus 12 months

By contrast, a 67% reduction in the odds of definite/probable stent thrombosis was observed with extended versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy (odds ratio 0.33 (95% confidence interval 0.21 to 0.51); P<0.001; I2=18%; fig 2). The corresponding rates were 0.32% (26/8196 patients) versus 0.98% (79/8096), with a number needed to treat of 152. Similarly, the analysis of definite stent thrombosis showed a 70% reduction in the odds of stent thombosis with extended versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy (0.30 (0.19 to 0.49); P<0.001; I2=32%; corresponding rates 0.27% (22/8196) v 0.89% (72/8096; fig 2).

Timing of stent thrombosis

We saw similar rates of late stent thrombosis when comparing short term with 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy (0.36% (20/5501 patients) v 0.31% (16/5089); odds ratio 1.24 (95% confidence interval 0.65 to 2.36); P=0.50; I2=40%). By contrast, the odds of very late stent thrombosis were significantly reduced by 67% when comparing extended with 12 month therapy (0.32% (26/8196) v 0.98% (79/8096); 0.33 (0.21 to 0.51); P<0.001; I2=18%; fig 2).

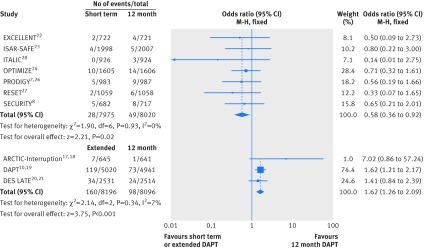

Major bleeding

Major bleeding rates were available in all studies (n=32 287). Short term versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy was associated with a roughly 40% reduction in the odds of major bleeding (event rate 0.35% (28/7975 patients) v 0.61% (49/8020); odds ratio 0.58 (95% confidence interval 0.36 to 0.92); P=0.02; I2=0%); the corresponding number needed to treat to prevent a major bleed was 385. Conversely, continuation of dual antiplatelet therapy beyond 12 months significantly increased the odds of major bleeding by 62% (1.95% (160/8196) v 1.21% (98/8096); 1.62 (1.26 to 2.09); P<0.001; I2=7%; fig 3); the corresponding number needed to harm by causing a major bleed was 135.

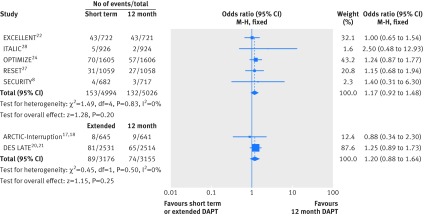

Fig 3 Individual and summary odds ratios for the endpoint of major bleeding. Data stratified by duration of dual antiplatelet therapy: short term (<12 months) versus 12 months, and extended (>12 months) versus 12 months

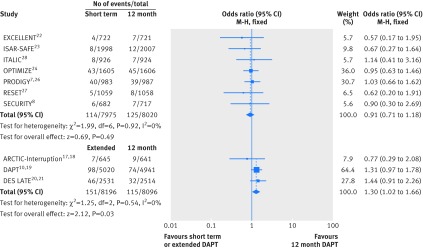

All cause mortality

All 10 randomised controlled trials (n=32 287) provided data for all cause death. We found no significant differences in all cause mortality between short term and 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy (event rate 1.43% (114/7975 patients) v 1.56% (125/8020); odds ratio 0.91 (95% confidence interval 0.71 to 1.18); P=0.49; I2=0%; fig 4). By contrast, extended versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy was associated with a higher risk of all cause death (1.84% (151/8196) v 1.42% (115/8096); 1.30 (1.02 to 1.66); P=0.03; I2=0%; fig 4). The number needed to harm was 238.

Fig 4 Individual and summary odds ratios for the endpoint of all cause mortality. Data stratified by duration of dual antiplatelet therapy: short term (<12 months) versus 12 months, and extended (>12 months) versus 12 months

Repeat revascularisation and cerebrovascular accidents

Repeat revascularisation data were available from seven studies (n=16 351). Short term duration of dual antiplatelet therapy yielded similar results compared with 12 month duration (event rate 3.06% (153/4994 patients) v 2.63% (132/5026); odds ratio 1.17 (95% confidence interval 0.92 to 1.48); P=0.20; I2=0%). Results with extended dual antiplatelet therapy were comparable to those with 12 month therapy (2.80% (89/3176) v 2.35% (74/3155); 1.20 (0.88 to 1.64); P=0.25; I2=0%; fig 5).

Fig 5 Individual and summary odds ratios for the endpoint of repeat revascularisation. Data stratified by duration of dual antiplatelet therapy: short term (<12 months) versus 12 months, and extended (>12 months) versus 12 months

All studies (n=32 287) provided data for cerebrovascular accidents. These events occurred in 0.45% of patients (36/7975) with short term dual antiplatelet therapy versus 0.49% (39/8020) with 12 month therapy (odds ratio 0.93 (95% confidence interval 0.59 to 1.46); P=0.75; I2=0%). Similarly, we did not see any significant differences in cerebrovascular accidents when comparing extended duration with 12 month duration (0.78% v 0.84%; 0.93 (0.66 to 1.31); P=0.67; I2=0%; web fig 9).

Sensitivity analyses

The results obtained by repeating the analyses using random effects models were highly consistent with the main findings (web table 5). Seven studies (n=17 716) reported major bleeding events by TIMI criteria.14 Short term dual antiplatelet therapy compared with 12 month therapy was associated with a significantly reduced rate of TIMI major bleeding (odds ratio 0.49 (95% confidence interval 0.26 to 0.94); P=0.03; I2=0%). Converse results were found with therapy continuation beyond 12 months compared with 12 month therapy (1.60 (0.97 to 2.64); P=0.07; I2=42%; web fig 10).

Nine studies reported the incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular accidents. No significant differences were seen with short term versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy (odds ratio 1.02 (0.86 to 1.22); P=0.81; I2=0%). The odds of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular accidents were significantly reduced by 22%, when extended therapy was compared with 12 month therapy (0.78 (0.67 to 0.92); P=0.002; I2=47%; web fig 11). Analyses in patients with and without acute coronary syndrome, younger or older than 65 years, and treated with different P2Y12 inhibitors (web table 6) showed no significant outcome differences among those subgroups. Sensitivity analyses for the extended versus 12 month regimen comparison after inclusion of the PRODIGY landmark analysis are in web figures 12-18. These analyses showed highly consistent findings with the main results, except for all cause mortality, which became of borderline significance (P=0.05) in the extended versus 12 month regimen comparison.

Discussion

The current meta-analysis compares the efficacy and safety of three different durations of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with drug eluting stents. To our knowledge, by its unique design, it is the first report focusing on outcomes with either short term or extended (beyond 12 months) duration of dual antiplatelet therapy versus 12 month therapy. By incorporating the most recent evidence from randomised controlled trials, this report forms the largest database on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy ever analysed (n=32 287).

There were two main findings. First, short term dual antiplatelet therapy, when compared to 12 month therapy, was associated with a similar rate of stent thrombosis or myocardial infarction, with a reduced risk of major bleeding. Second, extended therapy, compared with a 12 month regimen, reduced the odds of definite/probable stent thrombosis, very late stent thrombosis, and myocardial infarction, but increased the odds of major bleeding. While all cause mortality also increased in the extended versus 12 month regimen comparison, driven by non-cardiovascular events, this study finding becomes mitigated by the inclusion of the landmark analysis at 12 months of patients enrolled in the PRODIGY trial. Nevertheless, given the potential profound implications of this observation if confirmed to be true, further studies are needed to validate or confute this preliminary finding.

Coronary drug eluting stents—by inhibiting in-stent neointimal proliferation—have effectively reduced the need for repeat revascularisation compared with bare metal stents and have achieved widespread use worldwide.4 Concerns about drug eluting stents have arisen, however, regarding the propensity for thrombotic events occurring more than one year after implantation.1 2

Based on these considerations, current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association advocate at least 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug eluting stents.5 The European Society of Cardiology endorses six to 12 months of dual therapy after implantation, and 12 months for all patients with acute coronary syndrome irrespective of revascularisation strategy.6 Prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy (beyond 12 months), while protecting against thrombosis, will invariably increase the risk of major bleeding with an uncertain net impact on patient outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention.29 30 31 This benefit-risk dualism has raised controversies around the optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy that would maximise the effect against stent thrombosis while minimising the associated bleeding risk. As a result, recent randomised controlled trials have adopted a triad of duration models: short term, 12 months, and beyond 12 months.

Short term (<12 month) versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy

We did not observe any significant differences in myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis outcomes with short term dual antiplatelet therapy as compared with 12 month therapy, in the face of reduced bleeding complications. This neutral effect on ischaemic endpoints testifies for a similar efficacy and a greater safety profile with shortened therapy as compared with 12 month therapy. Our findings are consistent with those of recent trials (which were, however, limited in sample size) and two previous meta-analyses of four trials comparing short term with longer durations.9 32 The two analyses, however, included fewer studies that were, in addition, heterogeneous as to duration of prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy, spanning 12-24 months.

Extended (>12 month) versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy

Although previous studies had suggested that short term dual antiplatelet therapy is effective and safe, especially with the availability of modern interventional techniques and new generation drug eluting stents, the benefit to harm ratio of therapy beyond one year had remained largely unknown. Registry data had suggested improvements in ischaemic outcomes with prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy; however, registries are prone to bias owing to their observational design.33 34 An important finding was the 67% reduction in cumulative odds of definite/probable stent thrombosis and, specifically, of very late (>1 year) stent thrombosis with extended dual antiplatelet therapy when compared with 12 month therapy, at the price of higher major bleeding and all cause mortality. In practical terms, the numbers needed to treat and to harm were similar for thrombotic (number needed to treat 152) and bleeding (number needed to harm 135) events, highlighting the importance of balancing the patients’ thrombotic profile against their bleeding risk in case of prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy.

The pathophysiology of very late stent thrombosis has been attributed to incomplete re-endothelialisation caused by drug or scaffold induced inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation, belated stent malapposition, neoatherosclerosis, and inflammation induced by the durable polymers, which occur over time after drug eluting stent implantation.35 36 The results of the present meta-analysis suggest that in a subgroup of patients, both patient and stent related factors can interact adversely over time through retarded endothelialisation and persistent inflammation, culminating in very late stent thrombosis37 once dual antiplatelet therapy is withdrawn. On the other hand, major bleeding and apparently also all cause deaths (number needed to harm 238) were more common with prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy. It remains unclear whether this observation on total mortality is real and whether it might be explained by the effect of bleeding on fatal outcomes.

The DAPT trial,10 19 which is the largest to explore the effect of extended versus 12 month dual antiplatelet therapy, found ischaemic protection with extended therapy at the price of increased bleeding risk. In the present meta-analysis, a large number of myocardial infarctions were derived from the DAPT trial, which was only partly justified by the trial’s bigger sample size than the other trials. Indeed, the annual incidence of myocardial infarction in the DAPT trial was more than twice that reported by other studies. On the other hand, the annual incidence of other thrombotic complications (such as stent thrombosis) or of bleeding events in the DAPT trial seemed more consistent with those observed in the other included trials. Reasons for the marked difference in myocardial infarction rates—in the range of three extra events per 100 aspirin treated patients per year in the control group of the DAPT trial as compared to the other studies—remain unclear. Moreover, the consistency of direction of estimates testified by the very low heterogeneity across trials in our pooled analysis suggests that the overall effect of this meta-analysis is robust and can be interpreted with confidence. In view of the residual uncertainty on overall mortality and the clear bleeding liability associated with prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy, a long term regimen should probably be reserved to patients at high ischaemic risk and low bleeding risk, in whom such treatment would have been well tolerated for the first 12 months.

Implications for clinical practice

There are distinct effects associated with short term and extended dual antiplatelet therapy. Shorter duration yields fewer bleeding events than a longer duration, with comparable efficacy against ischaemic complications. Furthermore, extended therapy leads to a marked reduction of thrombotic complications at the price of increased bleeding rates with a signal towards increased all cause mortality. The currently recommended 12 month duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug eluting stent implementation is a compromise between ischaemic and bleeding risks. However, based on this meta-analysis, the 12 month recommendation seems to be a less appealing strategy to minimise bleeding risk or maximise ischaemic benefit than a short term or an extended therapy regimen, respectively.

The lack of clear-cut benefits observed with the 12 month strategy raises the question of whether this average duration of dual antiplatelet therapy might be replaced by a shorter or longer duration in patients at high or low bleeding risk, respectively.

The apparently discordant finding of similar ischaemic risks in trials comparing a short term versus 12 month duration of dual antiplatelet therapy—as opposed to an ischaemic protection conferred by an extended versus 12 month duration—may reflect differences in the selection of patient populations included in the studies. In trials randomising patients to a 12 month versus short term regimen, those at high bleeding risk were not excluded, and randomisation occurred relatively early after stent implantation (that is, immediately, or after one, three, or six months). Studies comparing 12 month with extended regimens randomised patients only after several months of dual antiplatelet therapy provided that no major bleeding episodes had occurred in the preceding months. These studies most likely selected, by design, a patient population at relatively lower risk of bleeding while receiving therapy.

In view of the possible association between bleeding and subsequent ischaemic and fatal events, it may be hypothesised that in less carefully selected populations (such as those patients included in short term v 12 month studies), the detrimental effect of bleeding on ischaemic endpoints and death would have counterbalanced the ischaemic protection potentially offered by dual antiplatelet therapy. On the other hand, prolonging therapy in the long term in patients at relatively lower bleeding risk (that is, those who tolerate this therapy for at least 12 months) could result in a more favourable reduction of ischaemic events, at the cost of some major haemorrhagic complications.

From an individual patient’s perspective, the results of this article suggest that the 12 month cut-off for dual antiplatelet therapy should not necessarily be considered as the optimal standard of care choice. Rather, durations shorter or longer than 12 months should be calibrated, taking into consideration the patient’s bleeding and ischaemic risk profile, in addition to procedural variables and acuity of presentation. Further, well powered trials are warranted to test the clinical effect of tailored dual antiplatelet therapy. A practical approach for clinicians, given the results of our pooled analysis, would be to offer to many patients, especially those at high bleeding risk, a duration of less than one year after coronary implantation of a drug eluting stent. Prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy beyond one year could represent an option for selected patients who present very high ischaemic and low bleeding risks.

Effect of dual antiplatelet therapy on all cause mortality

In the present article, all cause but not cardiovascular mortality was found to be increased with extended dual antiplatelet therapy as compared with 12 month regimens. These findings were at variance with a recent Bayesian non-standard meta-analysis, in which no difference in all cause, cardiovascular, and non-cardiovascular mortality was found between treatment durations.38 The Bayesian meta-analysis focused only on the mortality outcome and had broad inclusion criteria. It comprised patients with coronary artery disease undergoing medical management (that is, without coronary stent implantation) and patients without coronary artery disease, who qualified for inclusion based on multiple atherothrombotic risk factors, peripheral artery disease, or presence of atrial fibrillation. This recent pooled analysis also included a highly heterogeneous duration of regimens. Dual antiplatelet therapy spanned from six to 40 months in the so-called “extended DAPT” arm, which was compared to a similarly heterogeneous shorter “DAPT duration” group; this second group included not only a shortened regimen but also no dual antiplatelet therapy at all. Hence, while the finding of the mortality increase in our meta-analysis might be due to chance, it could also indicate an excess of deaths attributed to non-cardiovascular causes (for example, cancer related deaths, as observed in the large DAPT trial10 19) or to major bleeding.

Limitations

The results were analysed on trial level data and not on patient level data; individual patient information would have added further insights to the analysis. Furthermore, the criteria for inclusion of patients in this meta-analysis were broad, comprising both stable low risk and unstable high risk patients, according to the original trial designs, and reflecting more closely the case mix encountered in clinical practice. Different types of P2Y12 antagonists (clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor) and drug eluting stents were used across and within trials. These data should be viewed as reflecting real world routine practice in all patients treated with different antiplatelet drugs and drug eluting stents, based on clinical settings, operator choices, and drug availability.

On the other hand, all the main and sensitivity analyses performed were consistent, suggesting that the effects of the different durations of dual antiplatelet therapy were robust and justified. Since most randomised trials were performed under clopidogrel, and first generation drug eluting stents were implanted in a sizable fraction of patients, further randomised controlled trials are needed to explore the effect of novel P2Y12 inhibitors and new stents on the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. Finally, no data were available to specifically test the interaction of different stents and different DAPT durations.

Conclusions

Discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy before the recommended 12 month period following percutaneous coronary intervention with drug eluting stents yields significantly reduced bleeding without increasing ischaemic outcomes. By contrast, dual antiplatelet therapy maintained well beyond 12 months (that is, up to 24 or 30 months) reduces the incidence of thrombotic complications, in particular stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction, at the price of increased major bleeding and possibly all cause death. The effect of extended dual antiplatelet therapy on mortality rates observed in the DAPT trial10 19 and confirmed in this meta-analysis remains preliminary, as a play of chance cannot be excluded. However, this observation warrants further investigation as, if true, could have profound consequences on public health.

What is already known on this topic

Dual antiplatelet therapy is currently recommended after the implantation of drug eluting stents, but the optimal duration is a matter of debate

The currently recommended 12 month duration is of uncertain value

What this study adds

Compared with a 12 month duration, short term (<12 months) dual antiplatelet therapy yields reduced bleeding without increasing ischaemic complications

Dual antiplatelet therapy extended beyond 12 months reduces ischaemic and thrombotic events compared with a 12 month regimen, but at the price of greater risk of major bleeding and all cause death

The increase in all cause but not cardiovascular death seen with extended therapy requires further investigation

Contributors: EPN and MV conceived and designed the study. EPN, MK, and VS collected and abstracted the data. EPN undertook the statistical analysis; EPN and MV drafted the manuscript. All authors analysed and interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. EPN is the guarantor.

Funding: Part of this study was supported by the Collaborative Research Center 1116 Masterswitches in Myocardial Ischemia, funded by the German Research Council (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that EPN has received honorariums for lectures from Eli Lilly; MV has received fees for lecturing from or has served on the advisory board of Abbott Vascular, Alvimedica, AstraZeneca, Correvio, The Medicines Company, Medtronic, and Terumo; FA has received honorariums for lectures and advisory boards from Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS-Pfizer, and Daiichi Sankyo-Eli Lilly; all the remaining authors do not have any conflicts relevant to this contribution.

Ethical approval: None was required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h1618

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Web appendix: Supplementary material

References

- 1.Navarese EP, Tandjung K, Claessen B, Andreotti F, Kowalewski M, Kandzari DE, et al. Safety and efficacy outcomes of first and second generation durable polymer drug eluting stents and biodegradable polymer biolimus eluting stents in clinical practice: comprehensive network meta-analysis. BMJ 2013;347:f6530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarese EP, Kowalewski M, Kandzari D, Lansky A, Gorny B, Koltowski L, et al. First-generation versus second-generation drug-eluting stents in current clinical practice: updated evidence from a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials comprising 31 379 patients. Open Heart 2014;1:e000064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valgimigli M, Sabate M, Kaiser C, Brugaletta S, de la Torre Hernandez JM, Galatius S, et al. Effects of cobalt-chromium everolimus eluting stents or bare metal stent on fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: patient level meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;349:g6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangalore S, Kumar S, Fusaro M, Amoroso N, Attubato MJ, Feit F, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes with drug-eluting and bare-metal coronary stents: a mixed-treatment comparison analysis of 117 762 patient-years of follow-up from randomized trials. Circulation 2012;125:2873-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:e44-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Task Force members, Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J 2014;35:2541-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valgimigli M, Campo G, Monti M, Vranckx P, Percoco G, Tumscitz C, et al. Prolonging dual antiplatelet treatment after grading stent-induced intimal hyperplasia study I. Short- versus long-term duration of dual-antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting: a randomized multicenter trial. Circulation 2012;125:2015-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colombo A, Chieffo A, Frasheri A, Garbo R, Masotti M, Salvatella N, et al. Second generation drug-eluting stents implantation followed by six versus twelve-month - dual antiplatelet therapy- the security randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:2086-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassese S, Byrne RA, Tada T, King LA, Kastrati A. Clinical impact of extended dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary interventions in the drug-eluting stent era: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J 2012;33:3078-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Driscoll-Shempp P, Cutlip DE, Steg PG, et al. Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2155-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savovic J, Weeks L, Sterne JA, Turner L, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. Evaluation of the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials: Focus groups, online survey, proposed recommendations and their implementation. Syst Rev 2014;3:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation 2007;115:2344-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kikkert WJ, van Geloven N, van der Laan MH, Vis MM, Baan J Jr, Koch KT, et al. The prognostic value of bleeding academic research consortium (BARC)-defined bleeding complications in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a comparison with the TIMI (thrombolysis in myocardial infarction), GUSTO (global utilization of streptokinase and tissue plasminogen activator for occluded coronary arteries), and ISTH (International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis) bleeding classifications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1866-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seeger P, Gabrielsson A. Applicability of the cochran q test and the f test for statistical analysis of dichotomous data for dependent samples. Psychol Bull 1968;69:269-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med 2006;30;25:3443-57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Collet JP, Cayla G, Cuisset T, Elhadad S, Range G, Vicaut E, et al. Randomized comparison of platelet function monitoring to adjust antiplatelet therapy versus standard of care: rationale and design of the assessment with a double randomization of (1) a fixed dose versus a monitoring-guided dose of aspirin and clopidogrel after des implantation, and (2) treatment interruption versus continuation, 1 year after stenting (ARCTIC) study. Am Heart J 2011;161:5-12.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collet JP, Silvain J, Barthelemy O, Range G, Cayla G, Van Belle E, et al. Dual-antiplatelet treatment beyond 1 year after drug-eluting stent implantation (ARCTIC-Interruption): a randomised trial. Lancet 2014;384:1577-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Normand SL, Wiviott SD, Cohen DJ, Holmes DR, et al. Rationale and design of the dual antiplatelet therapy study, a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial to assess the effectiveness and safety of 12 versus 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy in subjects undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with either drug-eluting stent or bare metal stent placement for the treatment of coronary artery lesions. Am Heart J 2010;160:1035-41, 1041.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park SJ, Park DW, Kim YH, Kang SJ, Lee SW, Lee CW, et al. Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1374-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CW, Ahn JM, Park DW, Kang SJ, Lee SW, Kim YH, et al. Optimal duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation: a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation 2014;129:304-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gwon HC, Hahn JY, Park KW, Song YB, Chae IH, Lim DS, et al. Six-month versus 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents: the Efficacy of Xience/Promus Versus Cypher to Reduce Late Loss After Stenting (EXCELLENT) randomized, multicenter study. Circulation 2012;125:505-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulz-Schüpke S, Byrne RA, Ten Berg JM, Neumann FJ, Han Y, Adriaenssens T, et al. ISAR-SAFE: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 6 versus 12 months of clopidogrel therapy after drug-eluting stenting. Eur Heart J 2015; 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feres F, Costa RA, Bhatt DL, Leon MB, Botelho RV, King SB 3rd, et al. Optimized duration of clopidogrel therapy following treatment with the Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent in real-world clinical practice (OPTIMIZE) trial: rationale and design of a large-scale, randomized, multicenter study. Am Heart J 2012;164:810-6.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feres F, Costa RA, Abizaid A, Leon MB, Marin-Neto JA, Botelho RV, et al. Three vs twelve months of dual antiplatelet therapy after zotarolimus-eluting stents: the OPTIMIZE randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310:2510-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valgimigli M, Campo G, Percoco G, Monti M, Ferrari F, Tumscitz C, et al. Randomized comparison of 6- versus 24-month clopidogrel therapy after balancing anti-intimal hyperplasia stent potency in all-comer patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Design and rationale for the PROlonging Dual-antiplatelet treatment after Grading stent-induced Intimal hyperplasia study (PRODIGY). Am Heart J 2010;160:804-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim BK, Hong MK, Shin DH, Nam CM, Kim JS, Ko YG, et al. A new strategy for discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy: the RESET trial (REal Safety and Efficacy of 3-month dual antiplatelet Therapy following Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent implantation). J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilard M, Barragan P, Noryani AA, Noor HA, Majwal T, Hovasse T, et al. 6- versus 24-month dual antiplatelet therapy after implantation of drug-eluting stents in patients nonresistant to aspirin: the randomized, multicenter ITALIC trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:777-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steg PG, Huber K, Andreotti F, Arnesen H, Atar D, Badimon L, et al. Bleeding in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions: position paper by the working group on thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2011;32:1854-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarese EP, Schulze V, Andreotti F, Kowalewski M, Kolodziejczak M, Kandzari DE, et al. Comprehensive meta-analysis of safety and efficacy of bivalirudin versus heparin with or without routine glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor in patients with acute coronary syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:201-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarantini G, Brener SJ, Barioli A, Gratta A, Parodi G, Rossini R, et al. Impact of baseline hemorrhagic risk on the benefit of bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin in patients treated with coronary angioplasty: a meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Am Heart J 2014;167:401-12.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Hayek G, Messerli F, Bangalore S, Hong MK, Herzog E, Benjo A, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing short-term versus long-term dual antiplatelet therapy following drug-eluting stents. Am J Cardiol 2014;114:236-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faxon DP, Lawler E, Young M, Gaziano M, Kinlay S. Prolonged clopidogrel use after bare metal and drug-eluting stent placement: the veterans administration drug-eluting stent study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5:372-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barone-Rochette G, Foote A, Motreff P, Vanzetto G, Quesada JL, Danchin N, et al; EVASTENT Investigators. Stent-related cardiac events beyond three years after implantation of the sirolimus-eluting stent (from the evastent patients). Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Claessen BE, Henriques JP, Jaffer FA, Mehran R, Piek JJ, Dangas GD. Stent thrombosis: a clinical perspective. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:1081-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navarese EP, Castriota F, Sangiorgi GM, Cremonesi A. From the abluminal biodegradable polymer stent to the polymer free stent. Clinical evidence. Minerva Cardioangiol 2013;61:243-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siddiqi OK, Faxon DP. Very late stent thrombosis: current concepts. Curr Opin Cardiol 2012;27:634-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elmariah S, Mauri L, Doros G, Galper BZ, O’Neill KE, Steg PG, et al. Extended duration dual antiplatelet therapy and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2015;385:792-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary material