Abstract

An improved synthesis of 2′-[18F]-fluoro-2′-deoxy-1-β-d-arabinofuranosyl-5-iodouracil ([18F]-FIAU) has been developed. The method utilizes trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate (TMSOTf) catalyzed coupling of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-1,3,5-tri-O-benzoyl-d-arabinofuranose with 2,4-bis(trimethylsilyloxy)-5-iodouracil to yield the protected dibenzoyl-[18F]-FIAU. Dibenzoyl-[18F]-FIAU was deprotected with sodium methoxide to yield a mixture of α- and β-anomers in a ratio of 1:1, which were purified by HPLC. The procedure described in this article eliminates the need for HBr activation of the sugar prior to coupling with silylated iodouracil and is suitable for automation. The total reaction time was about 110 min, starting from [18F]-fluoride. The average isolated yield of the required β-anomer was 10±6% (decay corrected) with average specific activity of 125 mCi/μmol.

Keywords: FIAU, PET, Microfluidics, HSV1-tk

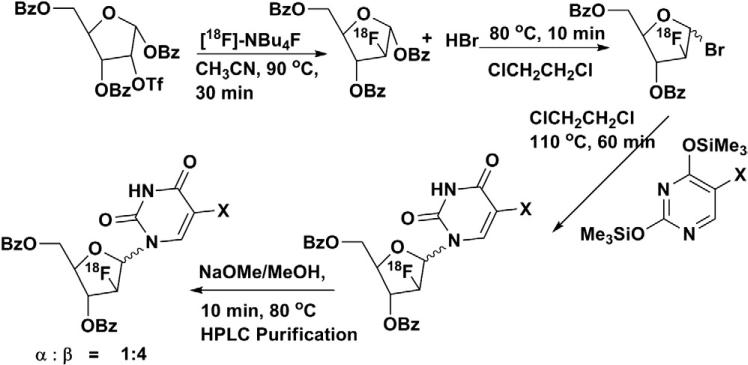

Reporter-gene imaging is a technique that can be used in live subjects to determine the location, duration and extent of expression of the gene of interest noninvasively [1,2]. Herpes simplex virus-1 thymidine kinase (HSV1-tk) gene is one of the most widely used reporter genes in molecular imaging applications. Radiolabeled nucleoside analogs, which have modifications either on the heterocyclic ring or on the sugar moiety [3,4], can be used for monitoring HSV1-tk gene expression by using positron emission tomography (PET) [5]. HSV1-tk gene expression imaging has been successfully utilized to visualize and monitor several biological processes including transcriptional regulation [6], lymphocyte migration [7,8] and stem-cell tracking [9]. Radiolabeled thymidine analogs of 2′-fluoro-2′-deoxy-1-β-d-arabinofuranosyl-5-iodo uracil (FIAU), [124I]-FIAU or [18F]-FIAU, have shown great potential as PET probes for imaging HSV1-tk gene expression [1,10–12]. Although [124I]-FIAU is easy to synthesize and has been used for HSV1-tk gene expression imaging in patients, the relatively long half-life of 124I (t1/2=4.18 days) is not suitable for repetitive imaging studies. Therefore, [18F]-FIAU, due to the shorter half-life (t1/2=110 min), is useful in applications where repetitive imaging is required, but the synthesis of [18F]-FIAU is not trivial. Seminal works by Alauddin et al. [13] and Mangner et al. [14] have yielded reliable but difficult multistep methods for the manual synthesis of [18F]-labeled thymidine analogs. Current methods employed for the synthesis of the [18F]-FIAU and other derivatives are notoriously difficult because of multiple-step reactions (Scheme 1), lengthy isolation protocols and low yields. Efforts to automate the synthesis have been stymied because an intermediate step involves generating the bromo sugar (4) by using highly corrosive HBr in acetic acid. A semiautomated procedure has been reported by Chin et al. [11] for the synthesis of 2′-[18F]-fluoro-2′-deoxy-1-β-d-arabinofuranosyl-5-ethyluracil ([18F]-FEAU) with 5±1% decay-corrected yields after a total synthesis time of 5.5 h. The reported semi-automated procedures require custom-designed automated synthesizers. In this work, we report a short and reliable TMSOTf-catalyzed synthesis of [18F]-FIAU which does not require the use of corrosive HBr [15]. The reported method is amenable for automation using existing 18F automated synthesizers with minor modifications.

Scheme 1.

General synthetic scheme for the synthesis of [18F]-FIAU.

The overall synthetic strategy is given in Scheme 2. The synthesis of 1,3,5-tri-O-benzoyl-2-[18F]-fluoro-α-d-arabinofuranose sugar was carried out on the Advion Nanotek LF system. This system makes use of a mini-column packed with MP1 anion exchange resin (Oak Ridge Technology Group, Inc., Oakdale, TN, USA). Carrier-free [18F]-fluoride in water from the MSKCC EBCO TR19/9 cyclotron was loaded onto the column by a pressurized microliter syringe and then eluted with 5×113 μl of a solution of kryptofix (30 mg/ml) and K2CO3 (5.5 mg/ml) in 90% CH3CN solution. The column was preactivated by washing with fluoride-free water (1 ml). The water was removed from the fluoride/ kryptofix mixture by azeotropic distillation with acetonitrile under a stream of argon (100 ml/min). The precursor 1,3,5-tri-O-benzoyl-2-trifluoromethylsulfonyl-α-d-ribofuranose (10 mg, ABX GMBH, Radeberg, Germany) was dissolved in 400 μl CH3CN, and the anhydrous mixture of kryptofix, K2CO3 and [18 F]-KF was passed simultaneously through the microfluidic reactor consisting of a coiled silica glass tubing (2 m×100 μm) at a flow rate of 50 μl/min at 125°C. A back-pressure regulator of 250 psi on the exit port of the reactor allows 125°C to be reached for the low-boiling CH3CN (bp 82°C). With a volume of 17 μl in the reactor loop and a flow rate of 50 μl/min, the residence time of reaction mixture is 20 s at 125°C. The radiolabeled sugar (3) was obtained and was used directly in the coupling reaction without any further purification steps.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of [18F]-FIAU. i) [18F]-KF/K2CO3/Kryptofix, ii) 85 °C, TMSOTf, ClCH2CH2Cl, 60 min iii) NaOMe/MeOH, 80 °C, 5 min iv) HPLC purification.

2,4-Bis(trimethylsilyl)-5-iodouracil was synthesized by heating a solution of 5-iodouracil (10 mg) in dichloroethane (500 μl), hexamethyldisilazane (100 μl) and TMSOTf (100 μl) in a sealed 3 ml V-vial at 85°C for 2 h. The radiolabeled sugar in CH3CN from the Advion unit was delivered directly to the vial containing 2,4-bis(trimethylsilyl)-5-iodouracil. The mixture was then heated at 85°C for 60 min. The solvent was evaporated at 85°C under a stream of argon to yield a viscous oil. To this mixture, 0.5 M sodium methoxide in methanol (1 ml) was added and the reaction was heated at 85°C for 5 min. The solvent was removed by heating at 85°C under a stream of argon. The precipitate was reconstituted in water (1 ml) and neutralized with 6N HCl. The products were purified by using reverse-phase HPLC on a semipreparative C-18 column (Luna, Phenomenex, Torrence, CA, USA; 250×10 mm 10 μm, C-18(2), 100 Å) and using a mixture of CH3CN and 0.2% acetic acid in water (88:12 v/v) at flow rate of 5 ml/min to yield a mixture of α- and β-anomers of [18F]-FIAU in a ratio of 1:1. Under the conditions used, the β-anomer eluted with a retention time of 12.2 min. The purity and specific activity of [18F]-FIAU were calculated using an analytical C-18 HPLC column (Bakerbond, 250×4.6 mm, Octadecyl C-18, 5 μm, 100 Å) with a mixture of CH3CN and 0.2% acetic acid in water (88:12 v/v) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min as eluant. Under the current conditions, the β-anomer elutes at 8.3 min. Previously reported methods for synthesis of [18F]-FIAU are difficult and impractical for routine production of the tracer [13,14]. Our objective was to simplify the synthesis of [18F]-thymidine analogs by eliminating the use of HBr/HOAc and to work towards reducing overall production times. Vorbrüggen and Bennua [15] have reported the synthesis of pyrimidine nucleosides by the direct coupling of protected sugars with 2,4-bis(trimethylsilyl)uracil derivatives in the presence of Lewis acids. However, the sugars used were 1-acetoxy arabinose derivatives. We have extended this methodology with 1-benzoyl arabinose derivatives for the synthesis of [18F]-FIAU.

As described above, the modified synthesis of [18F]-FIAU is a three-step process. The initial step involves fluorination of a protected sugar on the microfluidic synthesizer. Subsequent steps were performed manually but can be automated. The average isolated yield of the required β-anomer was 10±6% from a total of 18 runs. Coupling of the protected benzoyl sugar with the 2,4-bis-O-(trimethylsilyl)-5-iodouracil was efficient at 85°C. No significant coupling was observed at 60°C and coupling at 150°C resulted in decomposition products. The minimum and maximum yields obtained during our trial runs were 5% and 25%, respectively. The starting activity used in this optimization ranges from 62 to 150 mCi, but no correlation was observed with the final yield obtained. The average specific activity of [18F]-FIAU was 125 Ci/mmol (n=5), and the average time for the overall synthesis was 114 min. The low specific activity might arise from the fact that excess TMSOTf is used in the coupling reaction, which can potentially act as a fluoride source and reduce the specific activity of the final product. However, since the application of radiotracer is to image HSV1-tk gene expression and [18F]-FIAU acts as substrate for HSV1-tk enzyme, the low specific activity is not a concern and has a negligible effect on the image quality in vivo.

The α- to β-anomer ratio was 1:1, which is lower than the previous reports. Although α-glycosyl nucleoside derivatives [16] have been shown to exhibit antitumor, bacterio-static properties, the α-anomer has no affinity for the HSV1-tk enzyme and hence is considered as a waste byproduct. One likely reason for the unfavorable anomeric ratio is the presence of CH3CN, which favors the formation of α-anomer. The elimination of acetonitrile, in the coupling step, yields products with higher β- to α-anomer ratio, but the overall yields are low and hence we continued the synthesis in the presence of acetonitrile. However, isolated decay-corrected yields of about 10% are similar to yields obtained by using previous methods.

In conclusion, we have developed a short, robust and reliable method for the routine synthesis of [18F]-FIAU and other derivatives. Nucleophilic fluorination of the sugar was successfully accomplished by using the Advion Nanotek-LF system. The coupling of 2,4-bis(trimethylsilyl)-5-iodouracil with the [18F]-fluoro-sugar intermediate was accomplished manually and the modified procedure negated the use of highly corrosive HBr. Although the α- to β-anomer ratio is lower than that in previous reports, isolated decay-corrected yields are comparable and reaction times are substantially reduced. In addition, the current method can be easily extended for the synthesis of other [18F]-labeled thymidine analogs and can be adapted for full automation. Work on the optimization of the synthesis of [18F]-FEAU and other derivatives using fully automated procedures is underway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the staff of the Radiochemistry/Cyclotron Core at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center for assistance and Dr. Jason P. Holland for help in manuscript preparation. This research was supported in part by the Office of Science (BER), U. S. Department of Energy (Award DE-SC0002456, JSL).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.nucmedbio. 2010.01.003.

References

- 1.Serganova I, Mayer-Kukuck P, Huang R, Blasberg R. Molecular imaging: reporter gene imaging. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008:167–223. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77496-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponomarev V. Nuclear imaging of cancer cell therapies. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1013–6. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.064055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keller PM, Fyfe JA, Beauchamp L, Lubbers CM, Furman PA, Schaeffer HJ, et al. Enzymatic phosphorylation of acyclic nucleoside analogs and correlations with antiherpetic activities. Biochem Pharmacol. 1981;30:3071. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(81)90495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Clercq E. Antivirals and antiviral strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:704. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gambhir SS, Herschman HR, Cherry SR, Barrio JR, Satyamurthy N, Toyokuni T, et al. Imaging transgene expression with radionuclide imaging technologies. Neoplasia. 2000;2:118–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doubrovin M, Ponomarev V, Beresten T, Balatoni J, Bornmann W, Finn R, et al. Imaging transcriptional regulation of p53-dependent genes with positron emission tomography in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161091198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koehne G, Doubrovin M, Doubrovina E, Zanzonico P, Gallardo HF, Ivanova A, et al. Serial in vivo imaging of the targeted migration of human HSV-TK-transduced antigen-specific lymphocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:405–13. doi: 10.1038/nbt805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobrenkov K, Olszewska M, Likar Y, Shenker L, Gunset G, Cai S, et al. Monitoring the efficacy of adoptively transferred prostate cancer-targeted human T lymphocytes with PET and bioluminescence imaging. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1162–70. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pomper MG, Hammond H, Yu X, Ye Z, Foss CA, Lin DD, et al. Serial imaging of human embryonic stem-cell engraftment and teratoma formation in live mouse models. Cell Res. 2009;19:370–9. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyagawa T, Gogiberidze G, Serganova I, Cai S, Balatoni JA, Thaler HT, et al. Imaging of HSV-tk reporter gene expression: comparison between [18F]FEAU, [18F]FFEAU, and other imaging probes. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:637–48. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.046227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin FT, Namavari M, Levi J, Subbarayan M, Ray P, Chen X, et al. Semiautomated radiosynthesis and biological evaluation of [18F] FEAU: a novel PET imaging agent for HSV1-tk/sr39tk reporter gene expression. Mol Imaging Biol. 2008;10:82–91. doi: 10.1007/s11307-007-0122-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alauddin MM, Shahinian A, Park R, Tohme M, Fissekis JD, Conti PS. In vivo evaluation of 2′-deoxy-2′-[(18)F]fluoro-5-iodo-1-beta-D-arabinofuranosyluracil ([18F]FIAU) and 2′-deoxy-2′-[18F]fluoro-5-ethyl-1-beta-D-arabinofuranosyluracil ([18F]FEAU) as markers for suicide gene expression. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:822–9. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alauddin MM, Conti PS, Fissekis JD. A general synthesis of 2′-deoxy-2′-[F-18]fluoro-1-beta-D-arabinofuranosyluracil and its 5-substituted nucleosides. J Labell Compounds Radiopharm. 2003;46:285. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mangner TJ, Klecker RW, Anderson L, Shields AF. Synthesis of 2′-deoxy-2′-[18F]fluoro-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl nucleosides, [18F] FAU, [18F]FMAU, [18F]FBAU and [18F]FIAU, as potential PET agents for imaging cellular proliferation. Synthesis of [18F]labelled FAU, FMAU, FBAU, FIAU. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:215. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00445-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vorbruggen H, Bennua B. Nucleoside synthesis: 19. New simplified nucleoside synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978:1339–42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi T, Saneyoshi M. Synthetic nucleosides and nucleotides: 21. On the synthesis and biological evaluations of 2′-deoxy-alpha-D-ribofuranosyl nucleosides and nucleotides. Chem Pharm Bull. 1984;32:1441–50. doi: 10.1248/cpb.32.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.