Abstract

Regular interactions with people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) who are receiving care provide caregivers opportunities to deliver interventions to reduce HIV-related risks. We conducted a systematic review of behavioral interventions for PLWHA (provided at individual level by caregivers at HIV care settings) to determine their efficacy in reducing sexual risk behavior. Conference websites and biomedical literature databases were searched for studies from 1981 to 2013. Randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials (with standard-of-care control groups), considering at least one of a list of HIV-related behavioral or biological outcomes in PLWHA aged ≥18 receiving HIV care with at least 3-month follow-up were included. No language or publication status restrictions were set. Standardized search, data abstraction, and evaluation methods were used. Five randomized controlled trials were included in the review. We found limited evidence that sexual risk reduction interventions increase condom use consistency in HIV transmission risk acts, and reduce the number of (casual) sexual partners. We still believe that regular interactions between HIV care providers and PLWHA provide valuable opportunities for theory-based sexual risk reduction interventions to restrain the spread of HIV.

Introduction

Although majority of people make changes in their sexual behavior after being dianosed with HIV to avoid transmitting the infection, some continue to engage in unprotected sexual practices.1–3 High sexual risk behavior among HIV-infected people1,2 can have serious personal and public health consequences.

While historically HIV prevention focused on protecting people from becoming HIV infected, more recently the concept of ‘positive prevention’ [i.e., promoting physical and mental wellbeing in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and preventing further transmission of HIV], has emerged.4,5 It has been recognized that, from a public health perspective, it could be more efficient attempting to change behavior, including sexual risk-taking, among the fewer HIV-positives than the many HIV-negatives to fight the HIV/AIDS epidemic.6–8

PLWHA linked to and retained in HIV care attend HIV care settings for medical services. Those regular interactions with patients provide caregivers an opportunity for patient education and interventions to reduce ongoing risk behaviors and maintain safer practices. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Behavioral interventions are strategies designed to change persons' knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, or practices in order to reduce their personal health risks or their risk of transmitting HIV to others”.1 Reducing sexual risk behaviors among PLWHA has been the focus of many behavioral interventions.2,9,10 As behavior change occurs in incremental steps, messages delivered to patients receiving HIV care by clinicians or other qualified staff at HIV clinics during several or each visit could result in patients, over time, adopting and maintaining safer practices.1 To fit into the daily routine of a clinic, the intervention should be feasible—performed in a relatively short amount of time and added to other routine interactions with patients in the clinic, better reaching the patients when they attend the clinic and not requiring them to attend for additional visits.

Researchers in the field have identified, and the CDC HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Project has defined, efficacy criteria for HIV behavioral interventions to help HIV prevention planners and providers select rigorously evaluated and effective interventions for HIV prevention within their communities.11

The efficacy of feasible clinician-delivered behavioral interventions focusing on sexual risk-reduction with HIV-infected patients has not been studied extensively. Our aim was to systematically identify and synthesize research on behavioral interventions for adult PLWHA, provided on an individual level by caregivers in HIV care settings.

Methods

Considering studies

We built our study selection criteria on characteristics of effective behavioral interventions reducing HIV sexual risk taking among PLWHA identified in a previous meta-analysis,10 and defined by the CDC HIV/AIDS PRS Project as study design and implementation criteria for best-evidence HIV behavioral interventions.11

Studies meeting all of the following criteria were included in the review:

i. randomized controlled trials and quasi-randomized controlled trials (the latter only if they had independent comparison groups where prospective assignment was not based on participants' need or volition);12

ii. implementing HIV/AIDS interventions specifically designed for sexual risk behavior reduction to be delivered in health-care settings. We looked at behavioral individual-level interventions designed to promote sexual risk behaviour reduction, provided by HIV care providers [e.g., doctors, nurses, other trained (para) professionals] at HIV care centers; compared to ‘no such intervention’ (usual care or minor sexual risk reduction intervention, limited to information provision);

iii. focusing on adult (age ≥18 years) PLWHA aware of their HIV diagnosis, linked to and retained in HIV care (i.e., regularly attending HIV care centers for HIV-related healthcare services);

iv. collecting data on at least one HIV-related behavioral or biological outcome. The outcome of interest was sexual risk behavior reduction, based on at least one behavioral measure [number of sexual partners, number of condomless sexual acts or condom use consistency (i.e., always/not always using a condom)] or one biological measure [sexually transmitted infection (gonorrhoea, chlamydia infection) or hepatitis (B) acquisition].

v. assessing the outcome(s) after at least 3 months (90 days). Follow-up was measured from intervention initiation (introductory or main module/session) (i.e., not restricted to after completion of intervention follow-up).

Searching studies

We defined specific search terms for the following concepts: HIV/AIDS, sexual (risk) behavior, behavioral intervention, and (quasi)randomized study design12 to identify relevant studies from 1981 (the year AIDS was first reported)13 to 2013 (year end). No language or publication status restrictions were set.

The following electronic biomedical literature databases were searched between February 21 and 23, 2014: MEDLINE (PubMed), MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Cochrane Library), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), and CINAHL (EBSCOhost). We first developed a search strategy for PubMed, then adapted it to the search-engine properties of other databases.

Following the Cochrane Review Group on HIV/AIDS recommendations on searching archives of HIV/AIDS conference abstracts,14 we also searched applicable studies from abstracts of the following conferences: International AIDS Conference (AIDS), International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention (IAS), and Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) for the period of 1981 to 2013 (included). Using the AIDS Education Global Information System (AEGIS) database,15 we retrieved relevant abstracts from IAS conferences 2001–2009, AIDS conferences 1985–2008 (for 2008 only the first conference day available), and CROI 1993–2008. For IAS conferences 2011, 2013 and AIDS conferences 2008 (full conference), 2010, 2012 the International AIDS Society website16 was searched. CROI abstracts from 2009–2013 were not available online during our search in February 2014.

References of retrieved publications (all reviews upon retrieval, other articles during full-text review) were screened for additional reports of the same study and other relevant studies.

Selecting and evaluating studies

Citation search was conducted by two authors (MR, KTL). Citations retrieved from all the electronic databases were merged and duplicates deleted. The citations were inspected independently by two researchers. Publication screening by title and abstract was conducted by Mari-Liis Pürjer (Data Analyst, National Institute for Health Development, Estonia) and one of the authors (KTL). Full texts of all potentially eligible publications were read independently by AU and KTL, who assessed the study design, types of participants, interventions, and outcome measures. Agreement between two reviewers was measured with Cohen's kappa.12 Studies were promoted to the next phase after inclusion consensus was reached by the two reviewers. AU and KTL independently extracted characteristics of each study that met the review inclusion criteria. Authors of all studies included in our review were contacted (by KTL) to clarify study results and request data not provided in the publications.

Methodological quality of studies included in the review was independently assessed by two reviewers (AU and KTL) according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions.12 Potential selection bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and study personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (intention to treat analysis, outcome data completeness and how incomplete data were dealt with), reporting bias (selective outcome reporting) and other biases, if applicable, were evaluated. Quality was categorized as either ‘low risk’, ‘high risk’ or ‘unclear’ and listed in the risk of bias table broken down by study. However, we accept that blinding of participants and intervention providers is impossible in behavioral studies, thus performance bias, if present in an otherwise good quality study, was given less importance. At any stage of the review all disagreements and uncertainties were discussed, and consensus was reached between the two reviewers.

We hypothesized a priori that the intervention effect would depend on whether the intervention was focusing on several HIV transmission risk behaviors or sexual risk behavior alone. When the intervention was aimed at several transmission risk behaviors [sexual, drug-use, antiretroviral therapy (ART)], we only assessed the sexual risk behavior component. In studies with multiple follow-ups, we only looked at data from the last follow-up. We also hypothesized that the intervention effect would be influenced by the duration and intensity of the intervention, and whether the intervention was delivered by a caregiver in person or was computerized.

Results

Search results

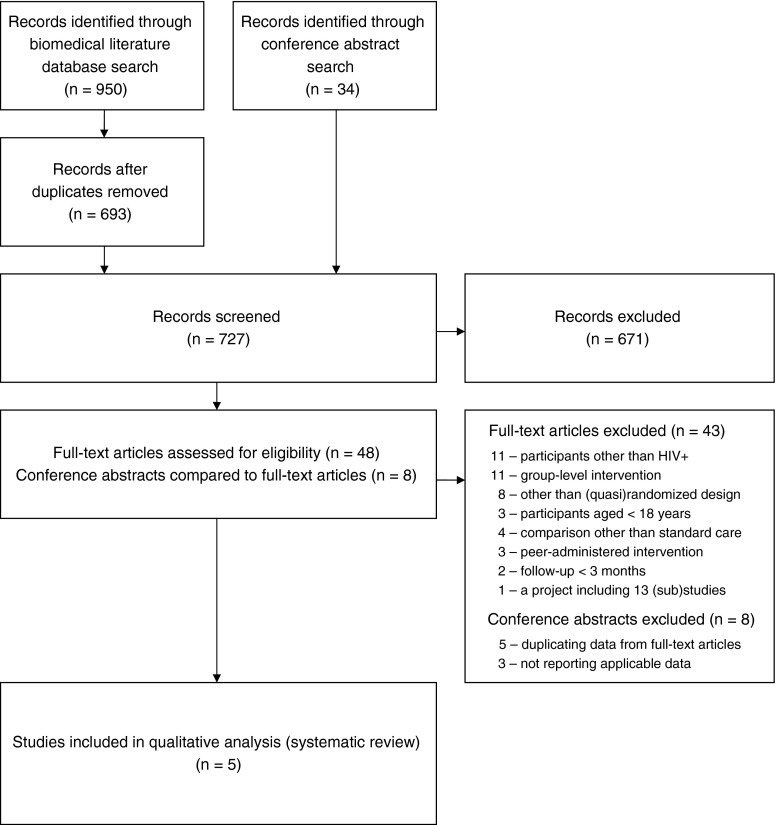

Our search of electronic databases of biomedical literature identified 950 citations: MEDLINE (PubMed) 424, MEDLINE (Ovid) 170, Embase 187, Cochrane CENTRAL 111, CINAHL 35, and PsycINFO 23. This was reduced to 693 after deleting duplicates. Additional search of conference websites identified 34 abstracts. Altogether 727 publications entered the ‘title and abstract’ review. Fifty-six potentially relevant publications were identified: 48 from biomedical literature databases, and 8 conference abstracts from additional search for conference proceedings. For the 48 publications from biomedical literature databases, full texts were retrieved. After comparing the authors of the 8 conference abstracts and the full text articles, we decided that 5 of the abstracts were reporting studies also described in the full-text publications we had retrieved, and these were therefore deleted as duplicates. The remaining 3 of the 8 conference abstracts, although referring to potentially relevant studies, did not report data applicable to our review. We did not manage to find publication(s) reporting on those studies in a further MEDLINE (PubMed) search (conducted by KTL). After assessment of the remaining 48 publications, 43 were excluded. In the final ‘full text’ review of publications the Cohen's kappa coefficient indicated good agreement between those rating the studies (K=0.73).12 The publication flow in our review process is provided in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

PRISMA diagram with flow of studies in the review.

During full-text review, we learned that one of the publications (Myers, 2010) reported results from a research initiative at 13 sites, with only 2 evaluating an intervention that met our review inclusion criteria.17 We found other publications reporting on this research initiative,18–22 but none including data on the intervention effect. We also did not succeed in obtaining additional information from the authors contacted (as of April 9th, 2014), and the study was excluded from further consideration.

Included studies

Five randomized controlled trials with two parallel arms—The Healthy Living Project Team 2007,3 Cornman 2008,23 Gilbert 2008,24 Kurth 2013,25 Safren 2013,26 comparing a behavioral intervention intended to reduce sexual risk behavior among PLWHA with no such intervention (standard care), met the review inclusion criteria. In the study by Gilbert,24 risk counseling at providers discretion was allowed in the comparison group, yet no information on whether or how this might have impacted the study results was provided. All but one study23 were conducted in the United States, all the studies ran between 2003 and 2007. The studies included adult PLWHA with mean age ranging from 34 to 45 years; and all but one studied both men and women.26 The Safren study26 looked at men having sex with men (MSM). Participants in all the studies were receiving HIV clinical care, except in the Healthy Living Project 20073 where this was not clearly stated. Yet as 69% of participants in that study were on ART, they (majority of participants in the study) could be considered as in clinical care. ART coverage ranged from 57% to 100% in four of the studies, with no information about ART in the Gilbert study.24 All studies included people from various ethnic groups.

Regarding sexual risk behavior, the inclusion criteria for participants in the selected studies ranged from no prerequisite of recent sexual activity23–25 to reporting at least one recent HIV sexual transmission risk act (i.e., a condomless sex act with a partner of unknown or negative HIV serostatus).23,26

Interventions in all of the studies were theory-based behavioral interventions, aimed at reducing HIV transmission risk behaviors among PLWHA. While the study by Cornman (2008) targeted only sexual risk behavior,23 in others the interventions were multitopic, including sexual risk behavior. The interventions were delivered individually, either in person3,23,26 or through computer,24,25 and with an animated ‘video doctor’ in the study by Gilbert.24 Intervention providers were social workers, community-based HIV services providers (including HIV counselors), and therapists. The interventions varied considerably in their intensity and duration—from a few 15-min sessions during regular HIV clinic visits approximately 3 months apart23 to extensive 90-min sessions, altogether 15 in 1 year.3

All the included studies assessed change in HIV transmission risk behavior, with sexual risk measured in terms of condomless sexual acts. In the study by Kurth,25 condomless acts included both the cases when a condom was not used and when a condom was used but with problems/errors. Researchers in all the other studies defined ‘condomless’ as not using a condom. While in the study by Gilbert,24 HIV sexual transmission risk was measured as consistently (in 100% of cases) versus inconsistently (<100%) using a condom during sex, in other studies the mean number of condomless acts was reported. The Gilbert 2008 study24 was the only one to assess the change in the number of sexual partners over time. Regarding HIV transmission risk behavior, three of the five studies23–25 reported sexual acts with all partners, while two3,26 only focused on sexual acts with unknown or negative HIV serostatus partners.

In all the included studies the published baseline characteristics of participants suggested that intervention effect data of interest for our review (the number of sexual partners, number of condomless sexual acts, and condom use consistency) might have been measured, yet were not reported in most of the studies. We contacted the corresponding authors of the publications, but did not succeed in obtaining additional information (as of April 9, 2014).

None of the studies included in our review measured sexual risk behavior reduction based on a biological measure, such as acquisition of a sexually transmitted infection (gonorrhoea, chlamydia infection) or hepatitis B. Characteristics of the included studies with evaluation of the participants-intervention-comparison-outcome (PICO) elements of the studies are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies: The PICO Elements

| Study | Setting(s) and study period | Sample characteristics | Intervention design | Intervention description | Sexual outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cornman 200823 | One urban HIV clinic; KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Study period: 10/2004–01/2005 |

HIV-infected; receiving HIV clinical care No precondition of sexual activity (and condomless sex), past 3 months (n=152) ≥18 years old, mean age 34 years (range 18–58 years); 43% male; 95% African/5% other; 93% reported heterosexual HIV acquisition; 66% on ARTa Participation rate 98%, overall retention 85% |

RCTb (2 arms) Intervention: Behavioral intervention; sexual risk topic Level: Individual Provision: HIV counselors, face-to-face, using Motivational Interviewing techniques Intensity-duration: 15 min session at each clinic visit (appr. 3 months apart) until study end Follow-up (post intervention): none Data collection: baseline and month 6 |

Aim: Reduce number of condomless sexual events; evaluate the feasibility and fidelity of the intervention adapted from the Options Project27 Theoretical basis: Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model Intervention group (n=103): brief patient-centered discussion (the Options for Health sexual risk reduction intervention)27 in addition to standard HIV counseling Comparison group (n=49): standard care (HIV counseling) |

Number of condomless sexual acts during last 3 months (all and HIV-/?): ↓ mean no. of sex acts with all partners from baseline in intervention arm (stat.sign.);↑in control arm (marginally stat.sign.) Same direction changes in condomless sexual risk acts with HIV-/? partners (marginally stat.sign) ↑total no. of sex acts (both w and w/o condom) in both arms from baseline (stat.sign) |

| Gilbert 200824 | Five outpatient HIV clinics; San Francisco Bay Area, US Study period: 12/2003–09/2006 |

HIV-infected (≥3 mo); receiving HIV care No precondition of sexual activity, and only had to report at least 1 of 3 risk behaviors (alcohol, drugs, sex): for sexual risk behavior past 3 months (n=476)≥18 years old, mean age 44.1 years (SD 9.09)c; 51% male; 29% white/ 50% black/African-American/ 13% Hispanic/Latino/ 8% other; 51% reported MSM/Wd/ 16% IDUe related HIV acquisition; data on ART not provided Participation rate 96% (of those 52% eligible according to risk behavior), overall retention 83% |

RCT (2 arms, 2:1) Intervention: Behavioral intervention; multitopic Level: Individual Provision: Interactive computer program, using Motivational Interviewing approach Intensity-duration: Average 24 min session prior to regularly scheduled medical appointment with booster at 3 months; post-session doctor-patient discussion (based on computer-suggested risk counseling statements) during medical appointment; behavioral assignment (take-away) Follow-up (post intervention): 3 months Data collection: baseline and months 3, 6 |

Aim: Reduce illicit drug-use, risky alcohol consumption and condomless anal-vaginal (UVA) sexual acts Theoretical basis: N/A Intervention group (n=243): Positive Choice intervention with computer-based risk assessment preceding tailored “Video Doctor” risk reduction counseling session; printout of behavioral assignment and referrals to substance use and harm-reduction services Comparison group (n=233): Computer-based risk assessment, followed by standard care, risk counseling at providers' discretion |

Sexual risk, measured by: (1) 100% (consistently) /<100% (inconsistently) using condom during last 3 months with main and/or casual partner(s): ↓UVA (stat.sign)g ↑Condom use, all partners: trend in both arms, no difference between arms (2) No. of sexual partners: ↓No. of casual partners (stat.sign) |

| Kurth 201325 | HIV clinic and community setting; Seattle, WA, US Study period: 03/2006–07/2007 |

HIV-infected, on ART No precondition of sexual activity, past ? months (n=240)≥18 years old; mean age 45 (SD 10.37)c years; 91% male; 46% white/25% black or African American/7% Hispanic/Latino, 22% other; 62% MSM; 11% current IDU Participation rate 80%, overall retention 87% |

RCT (2 arms) Intervention: Behavioral intervention; multitopic Level: Individual Provision: Computerized, personal, using motivational interviewing and social cognitive techniques Intensity-duration: 4 sessions with 3-month intervals; during 9 months Follow-up: 9 months Data collection: at baseline and months 3, 6, 9 |

Aim: Reduce HIV transmission risk and support ART adherence Theoretical basis: Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model, Transtheoretical Model of Change Intervention group (n=120): computerized CARE+f (audio-narrated assessment, tailored feedback, skill-building videos, health plan, and print-out) plus standard care Comparison group (n=120): computerized risk assessment plus standard care |

Transmission risk composite outcome, incl. no condom use or condom use with problems/errors (past 3 months) and ART adherence (30 days): ↓odds of transm.risks 0.55 lower at mo 9 compared to baseline in intervention group (stat.sign), while↑in control group;↓odds of transm.risks at mo 9 reduced in intervention group compared to control group (stat.sign) |

| Safren 201326 | HIV clinic in Boston, MA, US Study period: 04/2004–07/2008 recruitment 04/2004–08/2007 |

HIV-infected MSM; receiving HIV care reporting at least one sexual transmission risk act, past 6 months (n=201) ≥18 years old, mean age 40.7 (SD 7.8) years; white 74.6%/11.9% black/African American/8.5% latino/Hispanic/5.0% other; IDU % measured, not reported; 56.7% currently on ART Participation rate not reported (non-eligible and refusing reported together), overall retention 86% |

RCT (2 arms) Intervention: Behavioral intervention; multitopic Level: Individual Provision: Medical social worker, Motivational Interviewing approach Intensity-duration: Intervention module of 5 (50–90 min) sessions (1 intake+4 “interventions”) over appr. 3 months, followed by 4 boosters at mo 3, 6, 9, 12. Follow-up (post intervention): none (considering the boosters) Data collection: baseline and months 3, 6, 9, 12 |

Aim: Reduce sexual transmission risk behavior Theoretical basis: Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model; influenced by / adapted from Project EXPLORE28 Intervention group (n=100): 7 topics, same-format, but individualized delivery – mandatory ‘Having sex’ and others: ‘Party drugs’, ‘Managing stress’, ‘Triggers’, ‘Cultures, communities and you’, ‘Disclosure’, ‘Getting the relationships you want’. Comparison group (n=101): standard care |

Transmission risk, measured by no. of condomless sexual risk acts during last 3 months with HIV-/? partner(s): - number of acts, - no risk acts or at least 1 risk act (dichotomized) ↓in transmission risk in whole study population, but no sign. differences between study groups in transmission risk over time for either outcomes |

| The Healthy Living Project Team 20073 | HIV clinics and other community settings; 4 US cities (Los Angeles, CA; Milwaukee, WI; New York, NY; San Francisco, CA); Study period: 04/2000–02/2004 recruitment 04/2000–01/2002 |

HIV-infected (women, MSM, IDUs; at later stage also heterosexual men) considered at risk of sexually transmitting HIV; eligible only if reported at least 1 condomless sex act in past 3 months: with any HIV-/? partner OR HIV+ partner other than main (n=936)≥18 years old, mean age 39.8 years (range 19–67 years); 79% male (of whom 72% MSM); 32% white/45% African-American/15% Hispanic/8% other; 12% IDU/ 70% non-IDU; 69% on ART Participation rate 87%, overall retention 83% |

RCT (2 arms) Intervention: Behavioral intervention; multitopic Level: Individual Provision: Facilitators (social workers, therapists, community-based service providers) face-to-face, using cognitive-behavioral techniques Intensity-duration: 15 sessions (90 min each); during 12 months Follow-up (post intervention): appr 13 months Data collection: baseline and months 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 |

Aim: Reduce number of sexual risk acts; execute effective coping responses; enchance access and and adherence to medical services Theoretical basis: Social Action Theory Intervention group (n=467): 3 modules (safer behaviors; stress, coping and adjustment; health behaviors) Comparison group (n=469): No active psychosocial intervention (on waitlist) |

Transmission risk, measured by no. of condomless sexual risk acts during last 3 months with HIV-/? partner(s): ↓mean no. of sex risk acts with HIV-/? partners (stat.sign); ↓no. of sex risk acts with HIV-/? partners from baseline; observed in both arms, no difference between arms |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; bRCT, randomized controlled trial; ctotal sample mean age (SD) calculated by review authors based on means (SDs) of different study arms; dMSM/W, men having sex with men/women; eIDU, injection drug use; fCARE+, Computer Assessment & Rx Education for HIV-positive people.

Risk of bias in included studies

Three of the studies (The Healthy Living Project Team,3 Cornman,23 and Gilbert24) had unclear and/or high risk of bias, and two studies (Kurth25 and Safren26) had low risk of bias in majority of the domains evaluated. Sequence generation was reported and judged adequate in all studies but one.23 Allocation concealment was described in sufficient detail and judged adequate in only one of the studies.3

It is not possible to blind participants and care providers in behavioral intervention studies, and this was the case in all the studies reviewed. However, blinding of outcome assessors was probably used in the Cornman study,23 and thus detection bias in this study was judged ‘unclear,’ not ‘high’ as in all others.

Four of the five studies23–26 had high retention rates (83–87%). Differential loss to follow-up in study arms, if present, was dealt with adequately. Only in the Healthy Living Project 2007 was study follow-up in the intervention group significantly lower than in the comparison group.3 All studies but Gilbert24 reported having undertaken intention-to-treat analysis.

In the Gilbert study,24 certain outcomes and pre-planned analyses were mentioned, but not reported, and the outcomes that were reported were based on different analytical approaches (either including or excluding those lost to follow-up). In the Healthy Living Project Team3 and the Cornman23 publications, certain intervention effect data were reported only in small-format and thus hard-to-read figures.

The comparison of intervention and control groups at baseline in the Healthy Living Project3 revealed imbalance between study groups regarding the number of HIV sexual transmission risk acts, but rigorous statistical methods were applied to adjust for this imbalance. Although in the Safren study26 baseline HIV transmission risk behavior differences between study arms were not statistically significant, the standard deviation for mean risk behavior between the study arms indicated large heterogeneity within the intervention arm and thus imbalance between the study arms.

All the included studies relied on participants' self-report on sexual risk behavior, not cross-validating behavioral measures with biological ones [sexually transmitted infection (STI) and/or hepatitis acquisition]. Self-reporting might have been affected by the “social desirability” bias among study participants, especially those in the intervention group reporting improvement in sexual risk behavior, when outcome assessment was not blinded and conducted by study personnel also involved in intervention provision. The risk of bias assessment in the studies included in the review is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies: Risk of Bias

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Authors' judgment | Support for judgment | Authors' judgment | Support for judgment | Authors' judgment | Support for judgment |

| Cornman 200823 | Unclear risk | Not described | Unclear risk | Not described | High risk | Not used |

| Gilbert 200824 | Low risk | Randomization by computer (after computer-based risk-profile assessment) Gender imbalance in CG at baseline, but adjusted for gender in outcome assessment |

Unclear risk | Patients, providers not informed about group assignment Remark: Assignment likely deduced by some (computer print-outs for those assigned to intervention) |

High risk | Patients and providers not informed about group assignment, yet see the remark for allocation concealment |

| Kurth 201325 | Low risk | Pseudo-random number generation algorithm used | Unclear risk | Not described | High risk | Not used |

| Safren 201326 | Low risk | Randomization allocation list prepared by staff member in no contact with participants | Unclear risk | Sealed randomization envelopes (numbered) subsequently opened by interventionist | High risk | Not used |

| The Healthy Living Project Team 20073 | Low risk | Centralized well-protected randomization (website) Still comparison of transm. risk acts revealed imbalance between study groups at baseline; 9% mismatches with original assignments Rigorous statistical methods to adjust for the issues |

Low risk | Assignment to either of the study groups announced after inserting patient data into a centralized web-based randomization database | High risk | Not used |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement | Funding |

| Cornman 200823 | Unclear risk | Outcome assessments were conducted by research assistants (probably not same as counselors) using a structured questionnaire | Low risk | Overall retention 85%; no differential attrition by study arm in attrition analysis; intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis | Unclear risk | Prespecified outcomes by study arm reported only on figure – exact data not available | National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH); University of Connecticut |

| Gilbert 200824 | High risk | Not reported | Unclear risk | Overall retention 83%, yet differential loss to follow-up at different study stages ITT analysis with imputations for missing data not described |

High risk | Certain outcomes and pre-planned analyses mentioned, not reported Outcomes reported based on different analytical approaches (incl./excl. those lost to follow-up) |

US Department of Health and Human Services National Institute on Drug Abuse |

| Kurth 201325 | High risk | Lab personnel blinded, but this applies to VL; sex risk behavior assessment blinding not reported | Low risk | Overall retention 87%; non-differential drop-out ITT analysis |

Low risk | All outcomes reported | Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC); University of Washington Center for AIDS Research & NIH funded programs |

| Safren 201326 | High risk | Not reported | Low risk | Overall retention 86%, yet not reported whether drop-out differential or not; ITT analysis, direct likelyhood estim. procedures (imputing) | Low risk | All outcomes reported | NIMH |

| The Healthy Living Project Team 20073 | High risk | Not reported | Unclear risk | Follow-up was significantly lower among intervention vs. control group at 15 months (78% vs. 83%, p=0.03) and at 25 months (73% vs. 81%, p=0.01); ITT analysis | Unclear risk | For main outcome (transmission risk acts) data over time (at assessment each 5 months), both actual and model estimated, only provided on a figure, thus some of the data unavailable | NIMH & University of California; HIV Center/Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene/NY State Psychiatric Institute; Medical College of Wisconsin; University of California, SF |

VL, viral load.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 43 studies from the studies for which full texts were read. The main reasons for exclusion were: participants were HIV-negative; study design other than (quasi)randomized controlled trial; intervention provided in group(s). Most of the excluded studies had more than one reason to justify exclusion. We also excluded all the eight relevant conference abstracts, as data presented in five of these abstracts came from studies already described in publications included in our full-text review; and in three cases the abstracts did not report data relevant to our review question.

Effects of interventions

The outcome of interest in our review was sexual risk behavior reduction, based on at least one behavioral measure [reported number of sexual partners, number of condomless sexual acts, or condom use consistency (i.e., always versus not always using a condom)], or one biological measure [STI (gonorrhoea, chlamydia infection) or hepatitis B acquisition].

None of the studies included in the review used biological measures for sexual risk behavior evaluation. Regarding behavioral measures, sexual risk reduction intervention effect on the number of sexual partners was only reported in the Gilbert study, where a statistically significant difference between study arms in reduction in the mean number of casual sex partners (among those who completed the study) was observed [−2.7 (SD 8.4) in the intervention group versus −0.6 (SD 5.6) in the comparison group; p=0.042].24 Yet in this study only 38% of total 476 participants (those completing the study) provided the data.

While assessing the effect of sexual risk reduction intervention on the number of sexual acts protected/not protected with condoms, researchers approached the question in two ways—either looking at condom use with all or serodiscordant partners only, sexual acts not protected with condom in the latter case defined as ‘HIV transmission risk acts’. The Cornman study23 provided data about the intervention effect on the number of condomless sexual acts with partners regardless of their HIV serostatus. In this study, reduction in the mean number of condomless acts in the intervention group over time was statistically significant (p<0.05), yet a marginally statistically significant (p=0.05) increase was detected in the comparison group.23 Intervention effect difference between the two study groups was reported without measures of uncertainty, the 95% confidence intervals for change in the mean number of condomless sexual acts for both study arms were presented in a figure and were indistinguishable.

The Healthy Living Project Team3 and the Safren26 studies looked at sexual risk behavior change among PLWHA based on the number of condomless sexual acts with partners of unknown or negative HIV serostatus. The Safren study failed to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in reduction of the number of condomless sexual acts between the study arms—the mean number of HIV transmission risk acts in the intervention group was 0.50 lower than in the control group, p>0.641,26 likely due to large variability in the number of HIV transmission risk acts. The Healthy Living Project showed at the end of the study that the mean number of HIV transmission risk acts in the intervention group was not significantly different from the mean number in the control group (p=0.48).3

Only two of the five studies included in the review (Kurth25 and Safren26) provided data to assess sexual risk behavior change through condom use consistency. Aggregate effect measures (odds ratios) were reported for the dichotomized outcome. The odds of not always using a condom in HIV transmission risk acts in the intervention (compared to control) group was lower in the Kurth study (OR=0.46, 95% CI 0.25–0.84, p=0.012),25 yet marginally larger in the Safren study (OR=1.39, 95% CI 1.01–1.92, p<0.05).26 These differences could be attributed to different study populations, as all participants in the Safren study were MSM, while in the Kurth study, MSM accounted for only 62%; and the different baseline sexual risk behavior of participants of the two studies.25,26

Two of the studies had also looked at the effect of time on sexual risk reduction, comparing the study groups. In the Safren study, the risk of inconsistent condom use decreased significantly over time (OR=0.76, 95% CI 0.66–0.88, p<0.001), while the difference between the two study groups was nonsignificant [intervention main effect OR=1.13 (0.66–1.93, p>0.1); time and intervention interaction OR 0.94 (0.78–1.16, p>0.1)].26 In the Healthy Living Project study, a significant reduction in the number of transmission risk acts over time (from baseline) was observed in both groups (p<0.0001). In addition to that, although by study end (month 25) the difference between the mean number of risk acts in the study groups was not significant, it had been statistically significant when measured at months 15 and 20.3

Discussion

We conducted a rigorous publication search with terms addressing all the main concepts of our review question [the (quasi)randomized controlled study design, HIV/AIDS, sexual (risk) behavior, and behavioral interventions], and thus feel confident that we located all available studies.

Our review of 1981–2013 research on behavioral interventions for adult PLWHA (provided on individual level by caregivers in HIV care settings) to determine their efficacy in reducing sexual risk behavior retrieved a small number (n=5) of studies assessing effect using either randomized or quasi-randomized design.

Interventions in the studies that we found were conducted in real life conditions, yet differed greatly in duration and intensity–from brief (15-min) sessions a few months apart23 to fifteen 90-min sessions in a year.3 Participants were both men and women, except in one study with MSM, and included different ethnic groups. All studies included main HIV risk groups, based on HIV acquisition mode or reported risk-behavior (IDUs, MSM). Risky sexual behavior varied greatly, because two studies3,26 only recruited people reporting prior sexual acts not protected with condom during the past 3 months, while others had no precondition of (recent) sexual activity.

Overall, the quality of evidence in the studies included was relatively low, even when ignoring blinding of participants and providers which is not possible in behavioral intervention studies–only two of the five studies had low risk of bias (see Table 2).25,26 No evidence was available about the effect of sexual risk reduction intervention(s) on the more objective (i.e., biological measures of sexual risk behavior), as none of the studies included in the review measured STI and/or hepatitis acquisition. However, we believe that behavioral data of interest to us were probably recorded in all of the studies, judging from the list of characteristics reported for study participants at baseline or described in other parts of the publications. As we did not manage to fill in the data gaps, our analysis was based on a limited number of studies, reducing the ability to draw conclusions. Three different quality and size studies evaluated the intervention effect on the number of condomless sexual acts, yet failed to support the interventions.3,23,26

Some evidence about the intervention reducing the number of (casual) sexual partners was available from one study with relatively low quality.24 Even though the two studies included in our review that reported data on condom use consistency among PLWHA25,26 demonstrated heterogeneous results on the effects of sexual risk reduction interventions, good quality evidence from one of the studies25 suggests that an individual behavioral intervention aimed at sexual risk reduction is likely to increase condom use consistency. The complex nature of the dichotomous ‘always/not always using a condom’ measure (i.e., condom use consistency) might have affected the “negative” result of the other study,26 as PLWHA in the intervention group having never or seldom used a condom prior to the study might have started to use condoms sometimes, but not in 100% of sexual acts, and were thus still considered not consistently using condoms at follow-up, despite the potentially “positive” effect of the intervention and sexual risk behavior reduction among study participants in the intervention group.

Despite the limited evidence found, we still believe that regular interactions between HIV care providers and PLWHA, delivered in HIV care settings, provide valuable opportunities for theory-based sexual risk reduction interventions.29

Many studies were excluded from our review because of group-level interventions or using peer(s) as intervention providers, as were considered requiring patients to attend extra sessions at the clinic (for pre-scheduled group meetings) or additional human resources [peer(s) present during clinic opening hours]. While previous reviews have looked at sexual risk reduction interventions at different levels, including individual, group, and community level interventions of very different types, we focused on interventions that are most applicable in busy HIV clinic situations during routine interactions with patients (i.e., individual level interventions). However, in HIV clinics with more and different specialty care providers (including peer counselors) available, more diverse interventions may better meet the needs of PLWHA.

Four of the included studies were conducted in the United States, and one in South Africa. More studies have been conducted outside the US, but those were either not (quasi)randomized controlled trials or did not meet our other inclusion criteria. We believe that we avoided language bias by not excluding any study based on the language of publication. Not restricting on publication type enabled us to retrieve all relevant studies. Although we looked at one outcome (i.e., sexual risk behavior change/reduction), we allowed multiple measures from one study, thus maybe “diluting” the intervention effect to some extent. However, evidence was available for only one of our four pre-defined outcome measures. The definitions for the outcome measures did vary across the studies, for example, HIV transmission risk act defined as a sexual act with a serodiscordant partner when a condom was not used, or an act when a condom was either not used or used with a problem/error, despite the latter perhaps suggesting low condom use skills rather than willingness to use a condom.

Previous analyses have shown sexual risk reduction interventions to be effective at promoting protected sexual intercourse among adults living with HIV/AIDS,10,30 especially when guided by behavioral theories, and more intensive and longer in duration. Interventions delivered by healthcare providers during routine interactions with patients in medical care settings on an individual level, have previously demonstrated reduction in condomless sex.10 In contrast, a recent meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to promote condom use among HIV-positive women showed behavioral interventions to have little effect.9 Yet the authors of that review conclude that they would not discourage such interventions altogether, rather they recommended integrating them with other strategies. This also applies in the current era of ‘treatment as prevention’, when the more traditional HIV sexual transmission prevention strategies should still support antiretroviral therapy, as not everybody on treatment has the virus suppressed.31

Although it is the year 2014, we can still agree with the astonishment of the authors of a 2006 review by Johnson et al, that only a limited number of randomized controlled trials of risk reduction interventions have been conducted among people living with HIV.30 As available evidence is limited, based on both the number of studies conducted and the quality of the studies, more and better trials are needed. However, we admit that including studies with other minimally biased methods of assigning subjects to study arms may add valuable information.

It would also be useful for future research to better account for the diversity of interventions, focusing on subgroup analyses or otherwise comparing brief and rigorous interventions, those administered by providers in person to computerized or other technology systems; and for the heterogeneity of sexual risk behavior among PLWHA. Future reseach should focus on theory-based interventions that have previosly proven to be effective, perhaps peferring adaptation of an efficient intervention to the development of a new one.

Better standards for study methodology and data reporting (e.g., the CDC's HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Project criteria for best-evidence HIV behavioral interventions),11 should be followed to allow better comparison and pooling of results from different studies.

As outcomes, future studies should measure both behavioral and biological outcomes, the latter more objectively reflecting risk behavior; and over a longer follow-up period to ensure sustainability.32 The self-reported risky sexual behavior should be measured in a standardized way and be related to condomless sex (with both all and serodiscordant partners), and sex with multiple partners (both parallel and over time, main and casual).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mari-Liis Pürjer (Data Analyst, National Institute for Health Development, Estonia) for her contribution to conducting this review.

This research was supported by the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund within the research project “Bridging the gap in knowledge and practice of prevention and care for HIV in Estonia (HIV-BRIDGE),” and the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (Grant # SF0180060s09).

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Incorporating HIV Prevention into the Medical Care of Persons Living with HIV. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:1–24 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher JD, Smith LR, Lenz EM. Secondary prevention of HIV in the United States: Past, current, and future perspectives. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;55:S106–S115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Healthy Living Project Team. Effects of a behavioral intervention to reduce risk of transmission among people living with HIV: The healthy living project randomized controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;44:213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Advancing HIV prevention: New strategies for a changing epidemic, United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:329–332 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bekker LG, Beyrer C, Quinn TC. Behavioral and biomedical combintion strategies for HIV prevention. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasry A, Sansom SL, Hicks KA, Uzunangelov V. Allocating HIV prevention funds in the United States: Recommendations from an optimization model. PLoS One 2012;7:e37545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). High-impact prevention: CDC's approach to reducing HIV infections in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/strategy/index.htm (Last accessed January10, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy CE, Medley AM, Sweat MD, O'Reilly KR. Behavioral interventions for HIV positive prevention in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:615–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carvalho FT, Gonçalves TR, Faria ER, et al. . Behavioral interventions to promote condom use among women living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;9:CD007844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, et al. . Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviors among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS 2006;20:143–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Project. Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Behavioral Interventions. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/prevention/research/compendium/ (Last accessed January23, 2014)

- 12.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration 2011. Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org (Last accessed January10, 2014)

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pneumocystis pneumonia–Los Angeles. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1981;30:250–252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cochrane Review Group on HIV/AIDS. Recommendations on searching archives of HIV/AIDS conference abstracts. Available at: http://hiv.cochrane.org/node/59 (Last accessed February24, 2014)

- 15.AIDS Education Global Information System (AEGIS) database. Available at: http://ww1.aegis.org/search/ (Last accessed February24, 2014)

- 16.International AIDS Society. Available at: http://www.iasociety.org/ (Last accessed February25, 2014)

- 17.Myers JJ, Shade SB, Rose CD, et al. . Interventions delivered in clinical settings are effective in reducing risk of HIV transmission among people living with HIV: Results from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)'s Special Projects of National Significance initiative. AIDS Behav 2010;14:483–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimley DM, Bachmann LH, Jenckes MW, Erbelding EJ. Provider-delivered, theory-based, individualized prevention interventions for HIV positive adults receiving HIV comprehensive care. AIDS Behav 2007;11:S39–S47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koester KA, Maiorana A, Vernon K, et al. . Implementation of HIV prevention interventions with people living with HIV/AIDS in clinical settings: Challenges and lessons learned. AIDS Behav 2007;11:S17–S29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malitz FE, Eldred L. Evolution of the special projects of national significance prevention with HIV-infected persons seen in primary care settings initiative. AIDS Behav 2007;11:S1–S5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin SF, Myers JJ, Shade SB, et al. . Predicting HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected patients seen in clinical settings. AIDS Behav 2007;11:S6–S16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nollen C, Drainoni ML, Sharp V. Designing and delivering a prevention project within an HIV treatment setting: Lessons learned from a specialist model. AIDS Behav 2007;11:S84–S94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornman DH, Kiene SM, Christie S, et al. . Clinic-based intervention reduces unprotected sexual behavior among HIV-infected patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Results of a pilot study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48:553–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert P, Ciccarone D, Gansky SA, et al. . Interactive Video Doctor” counseling reduces drug and sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive patients in diverse outpatient settings. PLoS One 2008;3:e1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurth AE, Spielberg F, Cleland CM, et al. . Computerized counseling reduces HIV-1 viral load and sexual transmission risk: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;65:611–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safren SA, O'Cleirigh CM, Skeer M, et al. . Project Enhance: A randomized controlled trial of an individualized HIV prevention intervention for HIV-infected men who have sex with men conducted in a primary care setting. Health Psychol 2013;32:171–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, et al. . Clinician-delivered intervention during routine clinical care reduces unprotected sexual behavior among HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;41:44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koblin B, Chesney M, Coates T, EXPLORE Study Team. Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: The EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet 2004;364:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flickinger TE, Berry S, Korthuis PT, et al. . Counseling to reduce high-risk sexual behavior in HIV care: A multi-center, direct observation study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:416–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Chaudoir SR, Reid AE. Sexual risk reduction for persons living with HIV: Research synthesis of randomized controlled trials, 1993 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;41:642–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McMahon JM, Myers JE, Kurth AE, et al. . Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for prevention of HIV in serodiscordant heterosexual couples in the United States: Opportunities and challenges. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2014;28:462–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao Z, Li X, Mehrotra P. HIV/sexual risk reduction interventions in China: A meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:597–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]