Abstract

The aim of this study is to determine the effects of hypoxia on the proliferating potential and phenotype of primary human oral keratinocytes cultured at ambient oxygen tension (20%) or at different levels of hypoxia (2.0 and 0.5% O2). The effects of oxygen tensions on cellular metabolic activity, cell proliferation, clonogenicity and proliferation heterogeneity were measured. Cell cycle profiles were analyzed by fluorescent-activated cell sorter, and p21WAF1/CIP1 expression in G0/G1-phase was also concomitantly quantitated. The expression levels of cell cycle regulatory proteins were examined by immunoblotting, and the cellular senescence was assessed by senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining. Basal and suprabasal keratinocyte phenotypes were determined by the expression levels of 14-3-3σ, p75NTR and α6 integrin. Despite of lower metabolism, the proliferation rate and clonogenic potential were remarkably enhanced in hypoxic cells. The significantly higher percentage of cells in G0/G1-phase under hypoxia and the expression patterns of cell cycle regulatory proteins in hypoxic cells were indicative of a state of cell cycle arrest in hypoxia. Furthermore, decrease in the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p16INK4A and the fewer number of β-galactosidase positive cells suggested a quiescent phenotype rather than a senescent one in hypoxic cells. Compared with normoxic cells, differential expression pattern of keratinocyte phenotypic markers suggested hypoxic cells that generate minimal reactive oxygen species, suppress the mammalian target of rapamycin activity and express hypoxia-inducible factor-1α favor a basal cell phenotype. Thus, regardless of the state of cell cycle arrest, hypoxic conditions can maintain oral keratinocytes, in vitro, in an undifferentiated and quiescence state.

Keywords: Oxygen tension, oral keratinocyte, cell cycle, differentiation, microenvironment

Introduction

In most mammalian tissues, the oxygen tension drops after it enters the lungs from 21 % to less than 9 % (Vanderkooi et al., 1991). Oxygen is a potent biochemical signaling molecule that regulates the growth, fate and function of mammalian cells including various stem cells in terms of proliferation and differentiation (Haque et al., 2013). In a natural niche, a specialized cellular microenvironment where stem cells reside, low oxygen tensions play a role in maintaining an undifferentiated stem cell phenotype (Mohyeldin et al., 2010). At present, most in vitro culture conditions are employed under ambient oxygen concentration of 21% in contrast to the 1-9% range in the niche (Mohyeldin et al., 2010). In a variety of cells low oxygen tensions can provide beneficial effects for regenerative therapies because hypoxic conditions can promote cell proliferation in vitro (Yamamoto et al, 2013; Santilli et al, 2010).

An autologous tissue-engineered oral mucosa, constituting a full-thickness graft or an epithelial cell sheet, has been applied to patients intraorally and extraorally (Izumi et al., 2013; Inatomi et al., 2006). Oral mucosal epithelium is highly active in terms of cell turnover and regeneration, which implicates the presence of an in situ stem cell population (Izumi et al., 2007). Thus, oral mucosa keratinocytes can be an attractive stem cell source for regenerative medicine even though keratinocyte stem cells have not been specifically identified. However, an enriched population of oral keratinocyte progenitor/stem cells has been able to be isolated (Izumi et al., 2007). An important issue in tissue engineering/regenerative medicine is the expansion and maintenance of progenitor cells ex vivo, to produce a large number of cells in an undifferentiated and proliferative state. The optimization of the expansion process leads to the maximization of cell yield, reducing cell cultivation time, chance of contamination and total cost of the products.

Previous research has focused on hypoxia in pathological conditions, i.e. wound healing and cancer, and not with normal oral mucosa epithelium (Chen et al., 2012; Thorn et al., 1997). Although, to date, there is no direct measurement of oxygen tension in vivo in oral epithelium, physiological oxygen tensions in oral mucosa appear to be low, as reported in skin (Carreau et al., 2011). Since changes of cellular behavior and characteristics in oral keratinocytes under hypoxia condition are poorly-understood it is not known whether 20% oxygen tension is an optimal environment, in vitro, to expand oral keratinocytes. Thus, the aim of this study is to demonstrate cellular response and determine the changes in the proliferating potential and phenotypes of cultured oral keratinocytes under hypoxic conditions. The outcomes will provide a new strategy of how oral keratinocytes can be manipulated ex vivo for use in regenerative medicine.

Materials and Methods

Primary cell culture under hypoxic conditions

Keratinized oral mucosa, was obtained from persons undergoing minor dento-alveolar surgery at the Universities of Michigan and Niigata. The protocol for harvesting human oral mucosal tissue was approved by an Internal Review Board of both institutes. All individuals signed informed consent before the tissue samples were procured. Primary human oral keratinocytes were isolated and cultured routinely in a “complete” EpiLife® (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with EpiLife® Defined Growth Supplements (Life Technologies), 0.06 mM Ca++, Gentamicin (5.0 μg/mL; Life Technologies), and Amphotericin B (0.375 μg/mL; Life Technologies) as described previously (Kato et al., 2013). The majority of cells used in this study were from 4th to 7th passage, inclusive. To culture cells under hypoxic conditions, culture vessels were placed in a humidified molecular incubator chamber (Billups Rothenberg, Inc., Del Mar, CA), flushed for four minutes with a gas mixture of 2.0%O2 (5.0% CO2-93.0%N2) and 0.5%O2 (5.0% CO2-94.5%N2), then placed at 37°C in an incubator. Cells were fed with 2% and 0.5% O2 tensions equilibrating complete media every other day. As a normoxic condition (20%O2), vessels were placed in ambient oxygen in an incubator, at 37°C in a humidified 5.0% CO2 environment.

Measurement of cellular metabolic activity

Oral keratinocytes (5 × 103) were plated into 96-well microplates with 100 μL of complete EpiLife® culture medium. Twenty-four hours later, after a medium change, cells were cultured in normoxic and hypoxic conditions for up to ninety-six hours. Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Osaka, Japan) was used to determine cellular metabolic activity (dehydrogenase activity in viable cells) every 48 hours according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 690 nm using a Multiskan FC 96-well plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All assays were performed in triplicate. To eliminate variations among individual cells, we determined “% change of normoxic cells (control)” for comparison by dividing each OD of hypoxic cells by the OD of normoxic cells.

Cell proliferation

To determine cell proliferation, we counted the number of viable cells with trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cells were seeded into wells in a six-well plate at a density of 5×104 cells with 4 mL of culture medium. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were placed in either normoxic or hypoxic conditions and fed every other day. The number of viable cells was counted every other day up to six days. The average cell number from two wells was calculated. To eliminate variations among individual cells, “% change of control” was shown.

Clonogenic assay

For colony-forming efficiency assay, 5 × 103 of cells were plated into a six-well plate (Costar, Corning. NY. USA) and cultured for seven days under normoxic or hypoxic conditions with complete medium. Cells were fixed for ten minutes with methanol and stained with 2.0% crystal violet (Baker Chemical, Phillipsburg. NJ, USA). We enumerated colonies consisting of sixteen cells or greater under the microscope. In addition, from the scanned image using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/), the number of colonies, larger than 1 mm in diameter, was counted macroscopically. These counts were performed in triplicate. To eliminate variations among individual cells, “% change of control” was shown.

Proliferation tracking assay

To assess “proliferative heterogeneity”, we monitored the cycling activity based on the carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE) dye tracking as described elsewhere (Chadli et al., 2013). In brief, cell suspension in 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a density of 106 cells/mL was incubated in at a final concentration of 10μM CFSE (CellTrace™ CFSE Cell Proliferation kit, C34554, Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA) solution in the dark for 20 minutes at 37 °C, left for another 30 minutes at RT, and the labeling was ceased by adding prewarmed EpiLife® culture medium. After a minor subset of cells was separated, the majority of cells were plated for subsequent culture. The CFSE dye profile was analyzed by FACS (fluorescence activated cell sorting) Aria II (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) for cells immediately after the labeling and cultured for 48 and 72 hours. 7-AAD (7-amino- actinomycinD, BD Bioscience) and Fluoresbrite® microspheres (PolyScience Inc., Warrington, PA, USA) were used for the elimination of non-viable cells and a FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) standard, respectively. To compare “proliferative heterogeneity”, standard deviations and median were calculated. FlowJo software (FLOWJO, LCC. Ashland, OR, USA) was used to illustrate CFSE dye profile.

Cell cycle profile and p21WAF1/CIP1 expression analyses

Cell cycle and the expression level of p21WAF1/CIP1 were examined by bi-parameter flow cytometry. Cells grown in a 100mm dish under normoxic and hypoxic conditions for 48-72 hours were collected and fixed in final concentration of 80% ice-cold methanol at 4°C for at least 24 hours. After washing 5×105 fixed cells with 2.0% bovine serum albumin in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), cells were immunostained with 1μL/200μL Alexa488 Fluor conjugated anti-p21WAF1/CIP1 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, #5487) for one hour at room temperature (RT) in the dark. Subsequently, cells were incubated with propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich) (10μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) and ribonuclease A (100μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS for 30 minutes at 37°C. After the samples were kept on ice for 15 minutes, they were analyzed by FACS Aria II (BD Bioscience). Simultaneously, the expression level of p21WAF1/CIP1 in the G0/G1 phase fraction gated by R1 was also monitored, based on Alexa488 Flour-conjugated rabbit IgG isotype control (Cell Signaling Technology, #4340). Modfit software (BD Bioscience) was used to determine cell cycle profile.

Immunoblotting

RIPA buffer was used to obtain whole-cell extracts. A 10-15μg protein per lane were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride membranes. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with 1:2000 anti-Cyclin D1 and pRb (Cell Signaling Technology, #2926 and #9307), 1:1000 anti-Rb (Cell Signaling Technology, #9309), 1:1000 anti-Rb2/p130 (Beckton Dickinson Transduction Laboratories, 610262), 1:500 anti-p16INK4A and p75NGF (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, ab81278 and ab52987), 1:200 anti-14-3-3σ (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, MA5-11663), 1:1000 anti-HIF-1α (NB100-479) (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), 1:1000 anti-pS6K (Cell Signaling Technology, #9234), 1:1000 anti-S6K (Cell Signaling Technology, #2708), 1:1000 anti-pS6 (Cell Signaling Technology, #4857), 1:1000 anti-S6 (Cell Signaling Technology, #2217) or 1:2500 β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, #4970), followed by 1:2500 goat-anti mouse or rabbit (Cell Signaling Technology, #7076 and #7074). Signals were detected by the chemiluminescence reagent (Cell Signaling Technology). For quantitative comparison of protein band, films were scanned and quantified with Image J software. The ratio of phosphorylated to total Rb protein was calculated from three independent immunoblots.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining (SA-β-Gal)

Cells were plated into wells in a six microwell plate at a density of 1×105 cells with 2 mL of culture medium, and cultured under normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 72 hours. SA-β-gal activity was detected using the SA-β-gal staining kit (Cell Signaling Technology, #9860) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After six fields under the microscope (200×) were randomly photographed, the β-Gal positive cells were counted and the percentage was calculated by dividing the number of β-Gal positive cells by the total cell count, and multiplying by 100.

Detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

ROS was detected by Total ROS/Superoxide Detection kit (ENZ-51010; ENZO life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Oral keratinocytes (5×103) seeded in 96-well black wall/clear bottom plates (Falcon, Big Flats, NY, USA) were cultured under normoxic and hypoxic conditions for 72 hours. For a positive control, cells were treated with ROS inducer pyocyanin (200 μM), at 37°C for 30 minutes. Subsequently, cells were washed with 200 μl of 1× wash buffer and loaded with 100 μl of ROS/Superoxide detection reagents. Fluorescent intensity was measured 45 minutes after loading using a microplate fluorometer (TriStar LB 941; Berthold Technologies GmbH & Co. KG, Bad Wildbad, Germany) with excitation at 490 nm and emission at 525 nm for the detection. All assays were performed in sextuplicate.

Analysis of α6 integrin expression

The expression level of α6 integrin cultured in hypoxia and normoxia for 72 hours period was quantified by FACS Aria II (Beckton Dickinson). After harvesting cells, they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 minutes, followed by permeabilization in 0.5% triton-X-100 for 10 minutes at room temperature (RT). After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with a 1:200 dilution of FITC-conjugated anti-α6 integrin antibody (clone GOH3, sc-19622, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for one hour at RT. The expression level of α6 integrin between cells cultured in hypoxia and normoxia was quantified by FACS Aria II (Beckton Dickinson). FITC-conjugated, isotype matched, normal rat IgG1 was used as the negative control (BD Pharmingen).

Immunocytochemistry/fluorescence

Oral keratinocytes grown in chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), around 70% confluent, were cultured under hypoxic conditions for 72 hours before they were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 minutes. They were then permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 min, rinsed several times with PBS, incubated with 10% normal goat serum for 60 minutes at RT, then incubated with primary antibody to HIF-1α (NB100-479, 1:100) overnight at 4°C. Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was applied for 90 minutes at RT. After removing the chamber, glass coverslips were mounted onto slides in Vectashield (Vector Lab, Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA, USA) for DNA staining.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation of mean (SD) of the values obtained. Comparisons among three different O2 tensions were analyzed by either Tukey-Kramer or Steel-Dwass test after determining whether the samples were normally distributed or not. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cellular metabolic activity, cell proliferation, clonogenic and proliferation tracking assays

The cellular metabolic activity of hypoxic cells cultured for 48 hours was significantly lower than seen in normoxic cells while it was statistically different only between cells cultured for 96 hours at 20% and 2% O2 (Fig 1A). No statistical difference was noted between cells cultured at 2.0%O2 and 0.5%O2. We counted the number of viable cells in culture to assess the proliferation rate of cells under hypoxia. Cell proliferation was found to be significantly higher at both 2% and 0.5% O2 compared with 20%O2 (Fig 1B). The proliferation potential of hypoxic cells was also assessed by clonogenic assay. The number of colonies yielded under hypoxia, was 2-3 times higher than normoxia by both microscopic and macroscopic quantification (Fig 1C, D). Furthermore, we examined the cycle of division in normoxic and hypoxic cells by using the CFSE dye tracking assay, and detected a variety of patterns of the CFSE profiles among different oxygen tensions (Fig 1E) while the statistical analysis of SD and Median in CFSE profiles did not show significant differences (p=0.15).

Figure 1.

(A) Effects of three different oxygen tensions (20%, 2.0% and 0.5%) on the cellular metabolic activity of human oral keratinocytes up to 96 hours. The metabolic activity was assessed using a Cell-Counting kit-8 (N=10). Assays were performed in triplicate. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences determined by Steel-Dwass test (*p< 0.05).

(B) Effects of three different oxygen tensions on the proliferation rate of human oral keratinocytes up to 6 days. Viable cells were stained with trypan blue and counted (N=8). Assays were performed in duplicate. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences determined by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p< 0.05, **p< 0.01).

(C) Effects of three different oxygen tensions on the colony forming efficiency of human oral keratinocytes. Cells were stained with crystal violet and the number of colonies were microscopically and macroscopically counted (N=9) as stated in the Materials and Methods. An asterisk represents statistically significant difference determined by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p< 0.05). The statistical differences between normoxic and hypoxic cells were marginal except the microscopic quantification between 2.0% and 20%O2 culture condition.

(D) Representative images of clonogenic assay. After cells were cultured for 4 days at 20, 2.0 and 0.5% O2, colonies were fixed and stained with Crystal Violet as aforementioned.

(E) CFSE dye profile of cells cultured in normoxic and hypoxic conditions for 48 h. Their patterns were diverse among different oxygen tensions as well as individuals. The data shown are representative of six separate experiments. (a) 20% O2, (b) 2% O2, (c) 0.5% O2, (d) Overlay, (e) FITC standard beads. The values shown in (a), (b), (c) are the percentage of cells that could be experienced round of divisions of 2, 1 and 0 times according to the protocol of Chadli’s work.

Cell cycle profile and cell cycle regulatory protein expression

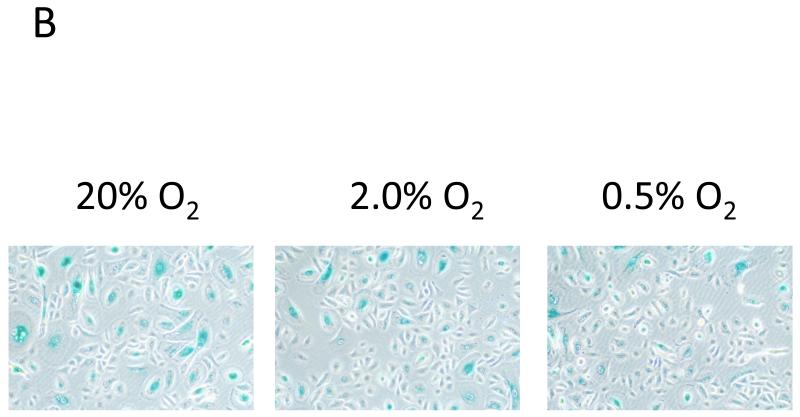

We analyzed the cell cycle profile to explain the dichotomy between lower metabolism and higher proliferation of the cultured cells. The proportions of actively-cycling (in G2/M-phase) and DNA-replicating (in S-phase) cells were fewer in hypoxic cells than in the normoxic cells consistent with the noted predominance of cells in the G0/G1 phase, implying a state of cell cycle arrest occurred more readily under hypoxic conditions (Fig 2A). To distinguish quiescence from senescence within the G0/G1 phase of the cell subpopulation, p21WAF1/CIP1 expression, which is required for initiating irreversible growth arrest, was concurrently measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 2B) (Topley et al., 1999). The proportion of cells expressed p21WAF1/CIP1 in the subpopulation of G0/G1 phase in hypoxic conditions were significantly lower than that in normoxic condition (Fig. 2C). An immunoblot of cyclin D1 expression and phosphorylated-Rb protein, involved in regulating cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase, was suppressed in hypoxic conditions (Fig 3A). Densitometry reading confirmed that the ratio of phosphorylated to total Rb protein was statistically different between normoxic cells and hypoxic cells (Fig 3B). The expression of p16INK4A was also reduced in hypoxic conditions consistent with down regulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 (Fig 3A). In contrast, the higher expression level of Rb2/p130, a marker of cells in G0 phase, was seen at 0.5% oxygen tension (Fig 3A). To further determine if the state of cell cycle arrest induced by hypoxia was reversible or irreversible, we assessed senescence-associated ß-galactosidase (SA-ß-Gal) activity and found the number of SA-ß-Gal positive cells were higher under normoxia than hypoxia (Fig 4A, B). This also supported the effects of hypoxic conditions maintaining oral keratinocytes in a quiescent (reversible cell cycle arrest) state rather than entering into a state of senescence (irreversible cell cycle arrest).

Figure 2.

(A) Distribution of human oral keratinocytes cultured at three different oxygen tensions (20%, 2.0% and 0.5%) in various phases of the cell cycle. Bar chart showing the cell distribution (%) in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases as determined by ModFit software. Data are mean percent ±standard deviations (SD) of 11 independent experiments. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences determined by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p< 0.05, **p< 0.01) .

(B) Representative dot plot images of flow cytometric analysis of DNA content and p21 WAF1/CIP1 expression.

(C) Ratio of p21 WAF1/CIP1 positive cells within G0/G1 phase of normoxic and hypoxic oral keratinocytes (N = 12). Statistically significant differences were present between normoxic and hypoxic cells determined by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p< 0.05).

Figure 3.

(A) Expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins. Western immunoblotting detection of cyclin D1, phospho-Rb, Rb, p16INK4 and Rb2/p130 in oral keratinocytes cultured in three different oxygen tensions for 48 hours. The results shown are representative of 4 separate experiments. β-actin is shown as a loading control.

(B) Rb phosphorylation of cells cultured in normoxic and hypoxic conditions was quantified based on the densitometric analysis (N = 3). Statistically significant difference of the ratio of phosphorylated to total Rb protein was present between normoxic and hypoxic cells determined by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p< 0.05).

Figure 4.

(A) Ratio of positive cells stained with SA-β-galactosidase at pH 6 under normoxia and hypoxia (N = 6). There was statistically significant difference between 2.0% and 20%O2 culture condition although the difference between 0.5% and 20% O2 pressure was marginal, which were determined by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p< 0.05).

(B) Representative images of SA-β-galactosidase staining after cells were cultured for 72 hours at 20, 2.0 and 0.5% O2.

Oral keratinocytes favor an undifferentiated phenotype under hypoxia

We also assessed whether the cell cycle changes noted in hypoxic conditions had an impact on the status of undifferentiated keratinocytes. The expression of 14-3-3σ, a regulatory protein specific to suprabasal differentiated keratinocytes, was inhibited in hypoxic cells (Fig 5A). Cells cultured at 0.5% oxygen tension had a higher expression of p75NTR, a putative stem cell maker for keratinocytes (Nakamura et al., 2007), when compared to cells cultured at either 2% or 20% oxygen (Fig 5A). The ratio of α6 integrin-immunopositive cells, similar in size to the documented smaller stem cells (Izumi et al., 2009), was significantly higher in 0.5% oxygen condition than in normoxia (Fig 5B). In addition, we further analyzed the levels of intracellular ROS and mTOR activity via downstream substrates because both are important modulators of energy metabolism for maintenance of quiescent cells. As a consequence, hypoxic conditions significantly inhibited both total ROS production and mTOR activity in oral keratinocytes, compared with normoxic cells (Fig 5C, D).

Figure 5.

(A) Expression of basal and suprabasal keratinocyte phenotypic markers. Western immunoblotting detection of 14-3-3σ and p75NTR in oral keratinocytes cultured in three different oxygen tensions for 48 hours. The results shown are representative of 4 separate experiments. β-actin is shown as a loading control.

(B) Ratio of α6 integrin positive cells under normoxia and hypoxia detected by flow cytometric analysis (N = 9). The α6 integrin expression ratio significantly increased at the oxygen tension of 0.5% compared with 20% O2 pressure while there was no statistical difference between 2.0% and 20% O2 culture condition determined by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p< 0.05).

(C) Total ROS production levels under normoxia and hypoxia measured by a microplate fluorometer (N = 10). Cells cultured at 20% O2 pressure generated total ROS and its level was close to a positive control cells incubated with 200μM of pyocyanin. In contrast, total ROS was barely detected in cells cultured in hypoxic conditions. There was a remarkable statistical difference between normoxic and hypoxic culture conditions determined by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*p< 0.001).

(D) Expression of down-stream substrates of mTOR signaling pathway. Western immunoblotting detection of p-S6K, S6K, p-S6 and S6 in oral keratinocytes cultured in three different oxygen tensions for 48 hours. The results shown are representative of 3 separate experiments.

HIF-1α expression in hypoxic cells

These results would seem to indicate that hypoxia favors a basal stem-like cell phenotype in oral keratinocytes and is consistent with the cells being in a more undifferentiated state. Lastly, we confirmed the induction of HIF-1α, a transcription factor identified as the master regulator for cellular adaptation to hypoxia, was noted under hypoxic conditions (Fig 6A, B). The fact implied low oxygen tensions mediate those cellular responses.

Figure 6.

(A) Immunofluorescence staining showed only a few cells expressed HIF-1α in their nuclei in normoxic condition. In contrast, there were a large number cells expressed HIF-1α in their nuclei under 2.0% and 0.5% O2 tensions. Original magnification ×200, scale bar=100 μm

(B) Higher expression of HIF-1α was detected from the whole cell lysates cultured in hypoxic conditions. β-actin is shown as a loading control.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates the effects of 2% and 0.5% O2 tensions on the cellular responses of primary human oral keratinocytes in vitro. One of the characteristic changes of oral keratinocytes under hypoxia is the enhancement of the cell proliferation and clonogenicity. The enhanced clonogenicity induced by the hypoxic condition between 1% and 5% O2 have been seen not only in epithelial cells, skin and corneal limbus (Bath et al., 2013; Ngo et al., 2007), but also mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (Yamamoto et al., 2013; Grayson et al., 2007). Thus, this cell behavior is consistent with the results seen in our study. However, the observed lower metabolism would appear to be in conflict with the higher proliferation rates seen in hypoxic cells. Several studies reported MSCs can be maintained in an undifferentiated state and expanded under hypoxic conditions by enhancing glycolysis instead of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. This implies that metabolic down regulation of oral keratinocytes cultured in hypoxic conditions is not directly related to a higher proliferation rate, especially under 2% oxygen tension in this study (Buravkova et al., 2013; Deschepper et al., 2011). This adaptive metabolic switch can result in an increase in ATP generation which is a critical factor in increasing cell survival at low oxygen levels (Kim et al., 2014).

In this study, the cell cycle profile revealed the low oxygen tensions predisposed to induce cell cycle arrest, apparently in G0/G1 phase, which was also confirmed by the expression pattern of regulatory cell cycle proteins, cyclin D1, Rb, phospho-Rb, Rb2/p130 and p16INK4A (Chandler et al., 2013; Helmbold et al., 2011; Wen et al., 2010; Genovese et al., 2006). Hypoxia-induced cell cycle arrest that was concurrent with higher cell proliferation and clonogenicity presented in this study is viewed as contradictory, as also previously seen in a study with limbal epithelial cells (Miyashita et al., 2007). However, this finding is supported by a recent study showing cycling and quiescent cell cycle state can coexist within an isogenic cell population (Overton et al., 2014). Another experimental work elucidating the balance between cell cycle arrest and cell proliferation by using a bistable switch model and a bifurcation diagram indicated there is a certain range of the levels in external signals such as growth factors, extracellular matrix and cell density, allowing a state of cell cycle arrest coexists with cell proliferation (Gérard and Goldbeter, 2014). Thus, higher cell density resulting from increase in proliferation rate under hypoxia might impinge on our results.

The present study also showed the decrease in the expression level of p21WAF1/CIP1 and the lower SA-ß-Gal activity, indicating this growth arrest is not irreversible senescence but reversible quiescence and the subset of cells, not expressing p21WAF1/CIP1, may be capable of contributing to the cell proliferation (Cheung and Rando, 2013; Jung et al., 2010; Weinberg et al., 2002). Since quiescent cells are recently thought to be distinct from cycling cells or cell cycle arrested cells, we speculate the phenotype seen in hypoxic cell subsets is mainly quiescence showing “a state of cell cycle arrest” that enables cells to re-enter a proliferating state after transient arrest (Yao, 2014). This is supported by the studies on suppression of conversion from arrest to senescence by hypoxia (Blagosklonny, 2013; Leontieva et al., 2012). Moreover, the tendency of diverse patterns of CFSE dye profile under different oxygen tensions could also denote the heterogeneous quiescent states, leading to heterogeneous proliferation (Yao, 2014).

The ability of hypoxic cells to maintain an undifferentiated state was the other major hallmark in this study, confirmed by the expression pattern of the suprabasal layer specific, differentiated keratinocyte phenotypic marker, 14-3-3σ (Kirschner et al., 2006). Moreover, basal cell phenotypic markers such as α6 integrin and p75NTR (Rezvani et al., 2011; Nakamura et al., 2007) were noted to be expressed in cells under 0.5% oxygen pressure. This was in agreement with previous studies on skin keratinocytes (Rezvani et al., 2011; Ngo et al., 2007) as well as other epithelial cells (Vaapil et al., 2012; O’Callaghan et al., 2011). Taken together, these outcomes illustrate that hypoxia can maintain oral keratinocytes in an undifferentiated state. Thus, a low oxygen microenvironment, in vivo, may act as a reservoir for a “progenitor” subsets of the basal cells layer in stratified epithelium (Nakamura et al., 2007). In addition, cells cultured in 0.5% O2 pressure may behave differently from cells in 2% O2 pressure based on the differential expression pattern of those three markers. Our results show that oral keratinocytes cultured in hypoxic conditions exist in a quiescent and undifferentiated state preventing the cells from moving into a senescence state and preserving their proliferative potential, in contrast to what is seen at ambient, 20%, oxygen tension that is associated with cellular senescence and a more actively cycling cell population.

There were studies demonstrating increase of ROS levels hampered the cell cycle quiescence in hematopoietic stem cell system (Ito et al., 2006) and induced premature senescence (Welford et al., 2006). Thus, the minimal production of ROS in hypoxic cells in contrast to its elevation in normoxic cells underpinned the data obtained in this study. This also contributed to the maintenance of an undifferentiated and quiescence state because mitochondrial ROS promote epithelial differentiation (Hamanaka et al., 2013). Moreover, we detected mTOR activity was downregulated in hypoxic cells, which is consistent with the previous reprt (Leontieva et al., 2012) and similar to our previous study using rapamycin, a potent mTOR inhibitor (Izumi et al., 2009). The fact that mTOR activity was suppressed in basal cells of oral mucosa in vivo shown in our previous study is indicative of low physiological oxygen pressure in oral mucosa as seen in skin (Rezvani et al., 2011). This suggests the energy production in basal cells is via anaerobic glycolysis rather than mitochondrial metabolism, which may be beneficial to minimize ROS production (Baris et al., 2011, Ivanovic et al., 2013).

Cellular adaptation and/or responses to a hypoxic microenvironment has been shown to be mediated by induction of the transcription factor HIF-1α expression (Moniz et al., 2014; Semenza, 2012) that was confirmed in oral keratinocytes under 2.0% and 0.5% oxygen tensions in this study. Although cellular responses shown in this study are likely to be attributed to the HIF-1α stabilization, further studies on HIF-1α-dependent and -independent molecular mechanisms are necessary to elucidate how it regulates quiescence and an undifferentiated state of oral keratinocytes.

Our ultimate goal is to manufacture tissue-engineered oral mucosa grafts that are more consistent by manipulating culture conditions and improving the current clinical protocol (Izumi et al., 2013). Clarification is needed to address the role of hypoxia in modulating the long-term proliferating potential and a regenerative capability of oral keratinocytes in vitro. This was recently shown that short-term hypoxic preconditioning of cells can enhance the angiogenic capacity of tissue-engineered oral mucosa (Perez-Amodio et al., 2011). The ex vivo expansion of oral keratinocytes and manufacturing of tissue-engineered oral mucosa substitutes by manipulating oxygen tensions can be beneficial to the strategies on the fabrication of cell-based products in regenerative medicine, eventually the identification of an oral keratinocyte stem cell and associated niche (Hawkins et al., 2013).

Acknowledgement

We thank Drs. Cynthia L. Marcelo and Toshiaki Tanaka for their critical comments, Dr. Masataka Oda for his technical assistance and Dr. Takeyasu Maeda for financial support to this study. This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 23659913 and 26293420) to K.I. from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), and National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant Number R01 DE019431 to S.E.F

Abbreviations used in this paper

- 7-AAD

7-amino-actinomycin D

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CFSE

carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- MSCs

mesenchymal stem cell

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- OD

optical density

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- PI

propidium iodide

- p-S6K

phosphorylated-ribosomal S6 protein kinase

- p-S6

phosphorylated-ribosomal S6 protein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RT

room temperature

- SA-β-Gal

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase stainin

- SD

standard deviation of mean

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Bath C, Yang S, Muttuvelu D, Fink T, Emmersen J, Vorum H, Hjortdal J, Zachar V. Hypoxia is a key regulator of limbal epithelial stem cell growth and differentiation. Stem Cell Res. 2013;10:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baris OR, Klose A, Kloepper JE, Weiland D, Neuhaus JF, Schauen M, et al. The mitochondrial electron transport chain is dispensable for proliferation and differentiation of epidermal progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1459–1468. doi: 10.1002/stem.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagosklonny MV. Hypoxia, MTOR and autophagy: converging on senescence or quiescence. Autophagy. 2013;9:260–262. doi: 10.4161/auto.22783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buravkova LB, Rylova YV, Andreeva ER, Kulikov AV, Pogodina MV, Zhivotovsky B, et al. Low ATP level is sufficient to maintain the uncommitted state of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:4418–4425. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreau A, El Hafny-Rahbi B, Matejuk A, Grillon C, Kieda C. Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1239–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadli L, Cadio E, Vaigot P, Martin MT, Fortunel NO. Monitoring the cycling activity of cultured human keratinocytes using a CFSE-based dye tracking approach. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;989:83–97. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-330-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler H, Peters G. Stressing the cell cycle in senescence and aging. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:765–771. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Gajendrareddy PK, DiPietro LA. Differential expression of HIF-1α in skin and mucosal wounds. J Dent Res. 2012;91:871–876. doi: 10.1177/0022034512454435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung TH, Rando TA. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:329–340. doi: 10.1038/nrm3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschepper M, Oudina K, David B, Myrtil V, Collet C, Bensidhoum M, et al. Survival and function of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) depend on glucose to overcome exposure to long-term, severe and continuous hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1505–1514. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01138.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese C, Trani D, Caputi M, Claudio PP. Cell cycle control and beyond: emerging roles for the retinoblastoma gene family. Oncogene. 2006;25:5201–5209. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gérard C, Goldbeter A. The balance between cell cycle arrest and cell proliferation: control by the extracellular matrix and by contact inhibition. Interface Focus. 2014;4:20130075. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2013.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson WL, Zhao F, Bunnell B, Ma T. Hypoxia enhances proliferation and tissue formation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:948–953. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka RB, Glasauer A, Hoover P, Yang S, Blatt H, Mullen AR, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote epidermal differentiation and hair follicle development. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque N, Rahman MT, Abu Kasim NH, Alabsi AM. Hypoxic culture conditions as a solution for mesenchymal stem cell based regenerative therapy. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:632972. doi: 10.1155/2013/632972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KE, Sharp TV, McKay TR. The role of hypoxia in stem cell potency and differentiation. Regen Med. 2013;8:771–782. doi: 10.2217/rme.13.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmbold H, Galderisi U, Bohn W. The switch from pRb/p105 to Rb2/p130 in DNA damage and cellular senescence. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:508–513. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inatomi T, Nakamura T, Kojyo M, Koizumi N, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S. Ocular surface reconstruction with combination of cultivated autologous oral mucosal epithelial transplantation and penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, Takubo K, Matsuoka S, Miyamoto K, et al. Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:446–451. doi: 10.1038/nm1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovic Z. Respect the anaerobic nature of stem cells to exploit their potential in regenerative medicine. Regen Med. 2013;8:677–680. doi: 10.2217/rme.13.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi K, Tobita T, Feinberg SE. Isolation of human oral keratinocyte progenitor/stem cells. J Dent Res. 2007;86:341–346. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi K, Inoki K, Fujimori Y, Marcelo CL, Feinberg SE. Pharmacological retention of oral mucosa progenitor/stem cells. J Dent Res. 2009;88:1113–1118. doi: 10.1177/0022034509350559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi K, Neiva RF, Feinberg SE. Intraoral grafting of tissue-engineered human oral mucosa. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2013;28:e295–303. doi: 10.11607/jomi.te11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YS, Qian Y, Chen X. Examination of the expanding pathways for the regulation of p21 expression and activity. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1003–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Izumi K, Saito T, Ohnuki H, Terada M, Kawano Y, et al. Distinct expression patterns and roles of aldehyde dehydrogenases in normal oral mucosa keratinocytes: differential inhibitory effects of a pharmacological inhibitor and RNAi-mediated knockdown on cellular phenotype and epithelial morphology. Histochem Cell Biol. 2013;139:847–862. doi: 10.1007/s00418-012-1064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Andersson KE, Jackson JD, Lee SJ, Atala A, Yoo JJ. Downregulation of Metabolic Activity Increases Cell Survival Under Hypoxic Conditions: Potential Applications for Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014 Feb 14; doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0637. 2014. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner M, Montazem A, Hilaire HS, Radu A. Long-term culture of human gingival keratinocyte progenitor cells by down-regulation of 14-3-3 sigma. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15:556–565. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leontieva OV, Natarajan V, Demidenko ZN, Burdelya LG, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. Hypoxia suppresses conversion from proliferative arrest to cellular senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13314–13318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205690109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita H, Higa K, Kato N, Kawakita T, Yoshida S, Tsubota K, et al. Hypoxia enhances the expansion of human limbal epithelial progenitor cells in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3586–3593. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohyeldin A, Garzón-Muvdi T, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moniz S, Biddlestone J, Rocha S. Grow2: The HIF system, energy homeostasis and the cell cycle. Histol Histopathol. 2014 Jan 10; doi: 10.14670/HH-29.10.589. 2014. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Endo K, Kinoshita S. Identification of human oral keratinocyte stem/progenitor cells by neurotrophin receptor p75 and the role of neurotrophin/p75 signaling. Stem Cells. 2007;25:628–638. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo MA, Sinitsyna NN, Qin Q, Rice RH. Oxygen-dependent differentiation of human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:354–361. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan AR, Daniels JT, Mason C. Effect of sub-atmospheric oxygen on the culture of rabbit limbal epithelial cells. Curr Eye Res. 2011;36:691–698. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2011.556302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton KW, Spencer SL, Noderer WL, Meyer T, Wang CL. Basal p21 controls population heterogeneity in cycling and quiescent cell cycle state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014:E4386–E4393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409797111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Amodio S, Tra WM, Rakhorst HA, Hovius SE, van Neck JW. Hypoxia preconditioning of tissue-engineered mucosa enhances its angiogenic capacity in vitro. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1583–1593. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani HR, Ali N, Nissen LJ, Harfouche G, de Verneuil H, Taïeb A, et al. HIF-1α in epidermis: oxygen sensing, cutaneous angiogenesis, cancer, and non-cancer disorders. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1793–1805. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani HR, Ali N, Serrano-Sanchez M, Dubus P, Varon C, Ged C, et al. Loss of epidermal hypoxia-inducible factor-1α accelerates epidermal aging and affects re-epithelialization in human and mouse. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:4172–4183. doi: 10.1242/jcs.082370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santilli G, Lamorte G, Carlessi L, Ferrari D, Rota Nodari L, Binda E, et al. Mild hypoxia enhances proliferation and multipotency of human neural stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell. 2012;148:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn JJ, Kallehave F, Westergaard P, Hansen EH, Gottrup F. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen on irradiated oral tissues: transmucosal oxygen tension measurements. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1103–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topley GI, Okuyama R, Gonzales JG, Conti C, Dotto GP. p21(WAF1/Cip1) functions as a suppressor of malignant skin tumor formation and a determinant of keratinocyte stem-cell potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9089–9094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaapil M, Helczynska K, Villadsen R, Petersen OW, Johansson E, Beckman S, et al. Hypoxic conditions induce a cancer-like phenotype in human breast epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderkooi JM, Erecińska M, Silver IA. Oxygen in mammalian tissue: methods of measurement and affinities of various reactions. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:C1131–1150. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.6.C1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg WC, Denning MF. P21Waf1 control of epithelial cell cycle and cell fate. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:453–464. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welford SM, Bedogni B, Gradin K, Poellinger L, Broome Powell M, Giaccia AJ. HIF1alpha delays premature senescence through the activation of MIF. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3366–3371. doi: 10.1101/gad.1471106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen W, Ding J, Sun W, Wu K, Ning B, Gong W, et al. Suppression of cyclin D1 by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 via direct mechanism inhibits the proliferation and 5-fluorouracil-induced apoptosis of A549 cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2010–2019. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao G. Modelling mammalian cellular quiescence. Interface Focus. 2014;4:20130074. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2013.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Fujita M, Tanaka Y, Kojima I, Kanatani Y, Ishihara M, et al. Low oxygen tension enhances proliferation and maintains stemness of adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. Biores Open Access. 2013;2:199–205. doi: 10.1089/biores.2013.0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]