Abstract

Class I hyaluronan synthases (HASs) assemble a polysaccharide containing the repeating disaccharide [GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcUA(β1,3)]n-UDP and vertebrate HASs also assemble (GlcNAc-β1,4)n homo-oligomers (chitin) in the absence of GlcUA-UDP. This multi-membrane domain CAZy GT2 family glycosyltransferase, which couples HA synthesis and translocation across the cell membrane, is atypical in that monosaccharides are incrementally assembled at the reducing, rather than the non-reducing, end of the growing polymer. Using Escherichia coli membranes containing recombinant Streptococcus equisimilis HAS, we demonstrate that a prokaryotic Class I HAS also synthesizes chitin oligomers (up to 15-mers, based on MS and MS/MS analyses of permethylated products). Furthermore, chitin oligomers were found attached at their reducing end to -4GlcNAc(α1→)UDP [i.e. (GlcNAcβ1,4)nGlcNAc(α1→)UDP]. These oligomers, which contained up to at least seven HexNAc residues, consisted of β4-linked GlcNAc residues, based on the sensitivity of the native products to jack bean β-N-acetylhexosaminidase. Interestingly, these oligomers exhibited mass defects of -2, or -4 for longer oligomers, that strictly depended on conjugation to UDP, but MS/MS analyses indicate that these species result from chemical dehydrogenations occurring in the gas phase. Identification of (GlcNAc-β1,4)n-GlcNAc(α1→)UDP as HAS reaction products, made in the presence of GlcNAc(α1→)UDP only, provides strong independent confirmation for the reducing terminal addition mechanism. We conclude that chitin oligomer products made by HAS are derived from the cleavage of these novel activated oligo-chitosyl-UDP oligomers. Furthermore, it is possible that these UDP-activated chitin oligomers could serve as self-assembled primers for initiating HA synthesis and ultimately modify the non-reducing terminus of HA with a chitin cap.

Keywords: activated oligosaccharide, chitobiosyl, Class I hyaluronan synthase, polymer synthesis, reducing end elongation

Introduction

Since the mechanism of HA polymer assembly is unusual, as described in the next paragraph, the nomenclature we employ is defined at the outset. Instead of writing a nucleotide sugar as UDP-GlcNAc, we use the sugar nucleotide nomenclature of GlcNAc(α1→)UDP for clarity and ease of describing various glycan species identified herein. This is consistent with the convention for writing hyaluronyl-UDP (HA-UDP) and other products of HA synthase (HAS) (and all other glycan structures), so that the reducing end is to the right. In addition, it emphasizes the key distinction that not all GlcNAc linkages in a putative chitin-UDP oligomer would be the same. In such a species, a (GlcNAcβ1,4)n oligomer is attached to a GlcNAc at the reducing end that is attached via an (α1→) linkage to UDP.

Class I HASs are phospholipid-dependent integral membrane proteins, whose multiple binding and catalytic activities (Table I) need only GlcUA-UDP, GlcNAc-UDP and Mg+2 ions in order to synthesize the repeating [GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcUA(β1,3)]n HA polysaccharide (Weigel 2002; Weigel and DeAngelis 2007). An important and very unusual aspect of Class I HAS function is that, unlike the vast majority of glycosyltransferases, sugar addition by this enzyme family occurs at the reducing end of HA rather than the non-reducing end (as for Class II HAS). This novel mechanism was first reported for streptococcal HAS (Prehm 1983) and verified by others in multiple studies of streptococcal HAS (Bodevin-Authelet et al. 2005; Tlapak-Simmons et al. 2005) and also confirmed for mouse and human HAS (Asplund et al. 1998; Prehm 2006). Most of these studies directly demonstrated the presence of UDP at the reducing end of the growing HA chains (e.g. using α32P-labeled GlcNAc-UDP). In this mode of sugar addition, the monosaccharide-UDP substrates are acceptors, not donors, and growing chains are thus HA-UDP, rather than HA. If the reducing end UDP is cleaved to generate free UDP and an HA chain, then further elongation of that HA chain cannot proceed and its final size becomes fixed.

Table I.

HAS requires multiple functions for HA synthesis by addition to the reducing end

| A. Established functions and activities for the synthesis of HA by Class I HAS |

| 1. GlcUA(α1→)UDP acceptor binding site |

| 2. GlcNAc(α1→)UDP acceptor binding site |

| 3. Hyaluronyl-GlcNAc(α1→)UDP donor binding site [for HA-GlcUA(β1,3)GlcNAc(α1→)UDP] |

| 4. Hyaluronyl-GlcUA(α1→)UDP donor binding site [for HA-GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcUA(α1→)UDP] |

| 5. Hyaluronyl-GlcNAc(α1→)UDP: GlcUA(α1→)UDP, hyaluronyl-GlcNAc(β1,4) transferase activity |

| 6. Hyaluronyl-GlcUA(α1→)UDP: GlcNAc(α1→)UDP, hyaluronyl-GlcUA(β1,3) transferase activity |

| 7. Hyaluronyl-UDP translocation activity [that moves the growing chain through an intraprotein HAS pore and across the membrane] |

| B. Overall HAS reaction for HA disaccharide synthesis |

(A) Seven established discrete binding or enzymatic activities are involved in HA assembly at the reducing end of a growing hyaluronyl-UDP chain (Weigel 2002). (B) The overall enzyme reaction for the addition of a disaccharide unit [D] at the reducing end of HA-UDP illustrates that the starting UDP group (boldface) attached to the HA group is displaced by hyaluronyl chain transfer to one of the two monosaccharides comprising the new disaccharide. Since it is not known if HA disaccharide synthesis is coordinated or sequential, the first monosaccharide-UDP added is not known (and not indicated). The last of two new monosaccharide-UDPs used to create the disaccharide remains attached to the elongated HA-UDP chain, whereas the first releases its UDP when the second sugar is added.

Activating phospholipids, such as tetra-oleoylcardiolipin, have been identified for streptococcal HASs (Tlapak-Simmons et al. 1999; Weigel et al. 2006) and several studies have shown that cholesterol and the lipid environment are important regulators of mammalian HAS function (Sakr et al. 2008; Ontong et al. 2014). Many groups have found that Class I HASs are potently inhibited by UDP, and we found that the rate of HA chain elongation and control of HA size are discrete enzyme functions that can be uncoupled by mutagenesis of conserved Cys residues near the membrane interface (Weigel and Baggenstoss 2012). Assembly of HA disaccharide units requires multiple discrete binding or activity HAS functions (Table IA) that illustrate both the important mechanistic features of glycan extension at the reducing end and the associated enzyme nomenclature and terminology, which are different from that for sugar addition at the non-reducing end. The overall reaction catalyzed by HAS during one round of disaccharide addition to a growing HA-UDP chain (Table IB) releases two UDPs, but these are derived from the starting HA-UDP and only one of the two substrate sugar-UDPs added; the second (last) sugar-UDP added remains attached to and activates the HA- chain. Although addition of a primer is not required to initiate HA chain assembly, there is often a kinetic lag before synthesis is detected (Baggenstoss and Weigel 2006), indicating that the initiation of HA chain assembly is a rate limiting step in overall synthesis. Two other important differences between Class I HASs and other glycosyltransferases are that: (i) exogenous free HA is not bound and extended by HAS and (ii) HAS elongation of HA-UDP is processive, dissociation of HA•HAS complexes is not detectable; HAS and HA-UDP do not dissociate during synthesis (DeAngelis and Weigel 1994; Baggenstoss and Weigel 2006).

Others have reported that Class I HASs from frog and mouse synthesize chitin (i.e. GlcNAc-β1,4) oligomers in the presence of only GlcNAc-UDP (Semino et al. 1996; Yoshida et al. 2000). Our hypothesis underlying the present study was that Class I HAS enzymes synthesize GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers and then use these novel UDP-activated substrates as self-primers to initiate HA synthesis. Given the mechanism of sugar addition at the reducing end, the finding of chitin oligomeric products in prior studies indicates that [GlcNAc(β1,4)]n-GlcNAc(α1→)UDP was made, but then cleaved to give free UDP and the observed [GlcNAc(β1,4)]n chitin oligomers. Using MS and glycosidase analyses to characterize products made by membrane-bound recombinant Streptococcus equisimilis HAS (SeHAS), we found that these unique predicted [GlcNAc(β1,4)]n-GlcNAc(α1→)UDP products are readily made by the enzyme.

Results

SeHAS synthesizes GlcNAcn oligomers

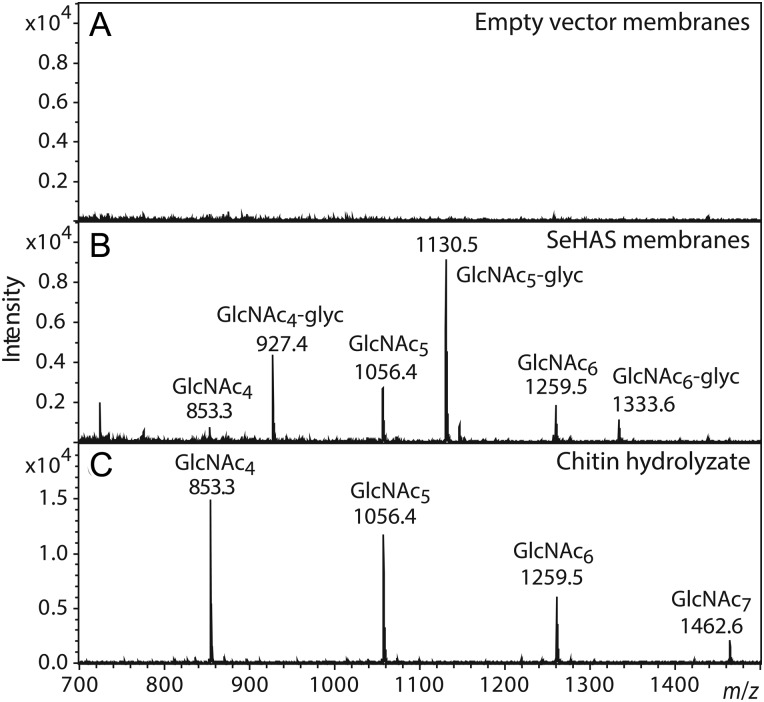

SeHAS membranes were incubated with GlcNAc(α1→)UDP and examined for their ability to produce chitin oligomers. After Folch extraction, products were selected by solid phase extraction on an activated charcoal cartridge and examined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Figure 1). SeHAS membranes made product ions (Figure 1B) at m/z 853, 1056, 1259 and 1463 corresponding to HexNAc4-7, and signals corresponding to HexNAc8,9 were also observed (not shown). Predicted and observed m/z values for chitin oligosaccharides are listed in Table II. In contrast, empty vector (EV) control membranes made no detectable species (Figure 1A). Commercial chitin oligomers from (GlcNAc)3 to (GlcNAc)10 were readily purified by this method and observable by MS (e.g. Figure 1C). GlcNAc and GlcNAc2 were not detected, presumably due to poor retention on activated charcoal and interference by matrix ions during MALDI-TOF MS. A similar HexNAc series was detected after enrichment by wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) affinity (Figure 2A and Table II), consistent with the expectation that these HexNAc oligomers consist of βGlcNAc. A distinct series of ions, similarly spaced by 203 mu (one HexNAc), was also detected after enrichment using either activated charcoal or WGA (e.g. m/z 927 and 1130; Figures 1B and 2A), and absent from the chitin hydrolysate. All ions in this series exhibited a mass increment corresponding to chitin oligomers with the addition of a glyceryl group. Consistent with this, removal of glycerol from the HAS membrane reaction mixes resulted in a reduction in or loss of these species. Thus, the glycerol conjugates may result from a secondary reaction promoted when glycerol is present at high concentration.

Fig. 1.

SeHAS synthesizes chitin oligomers in the presence of GlcNAc-UDP. EV (A) or SeHAS (B) membranes were incubated with GlcNAc-UDP and samples were processed by sequential passage over C18 and activated charcoal cartridges to purify oligosaccharides as described in the Materials and methods section. MALDI-TOF MS spectra in positive ion mode are shown for the samples and for a control mixture of commercial chitin oligomers (C). Products corresponding in mass to singly charged sodiated ions of HexNAc 4-, 5- and 6-mers are indicated and tabulated in Table II.

Table II.

Monoisotopic mass values of chitin oligomers

| Species | [M+Na]+ |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Observed (charcoal) | Observed (WGA) | |

| GlcNAc | 244.1 | ND | ND |

| GlcNAc2 | 447.2 | ND | ND |

| GlcNAc3 | 650.2 | ND | 650.3 |

| GlcNAc4 | 853.3 | 853.3 | 853.4 |

| GlcNAc5 | 1056.4 | 1056.4 | 1056.4 |

| GlcNAc6 | 1259.5 | 1259.5 | 1259.5 |

| GlcNAc7 | 1462.6 | 1462.6 | ND |

| GlcNAc8 | 1665.7 | ND | ND |

| GlcNAc9 | 1868.8 | ND | ND |

Product analysis of reactions containing SeHAS membranes incubated with GlcNAc-UDP only, as described in Figure 1. Products were enriched on an activated charcoal cartridge (as in Figure 1) or by WGA affinity (Figure 2) and analyzed in positive ion mode in a MALDI-TOF MS. Five species with m/z values identical to corresponding chitin oligosaccharide standards were detected (boldface font).

Fig. 2.

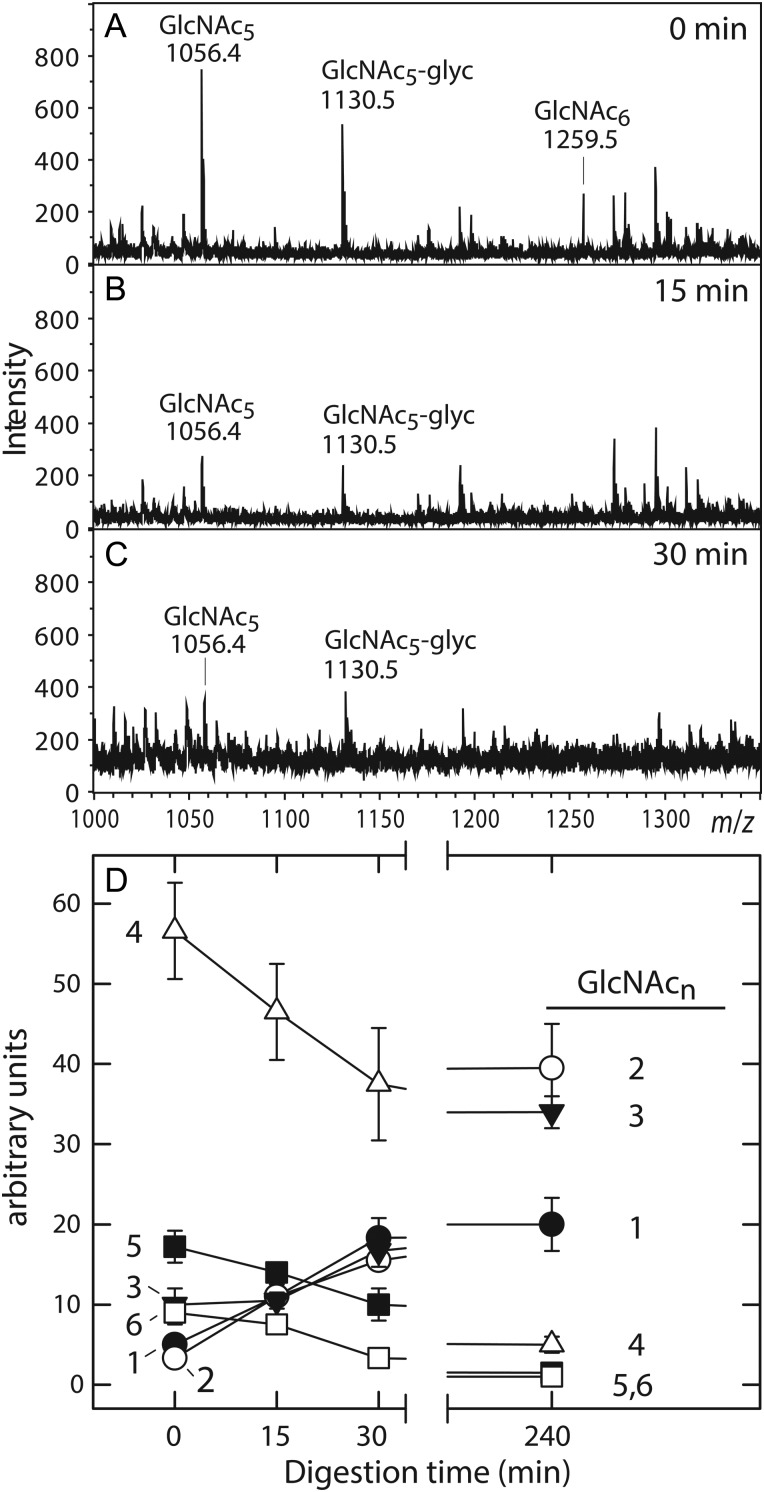

HexNAc oligomers synthesized by HAS are digested by chitinase. HexNAc oligomers synthesized by SeHAS were selected by WGA affinity chromatography and digested at 37°C with Streptomyces griseus chitinase as described in the Materials and methods section for 0 (A), 15 (B) or 30 (C) min and analyzed by positive ion mode MALDI-TOF MS. (D) Quantitation of changes. Total ion currents for chitinase digestion products, from experiments performed as in (A)–(C), were normalized to each MS peak baseline and the relative signal intensity of each oligomer was determined at the indicated times of digestion. The normalized and quantified m/z signals for digestion products corresponding to oligomers of (GlcNAc)1-6 (n = 1, filled circle; n = 2, open circle; n = 3, inverted filled triangle; n = 4, open triangle; n = 5, filled square; n = 6, open square) from three experiments are shown as a function of chitinase treatment time (mean ± SE signal intensity; n = 3).

For further characterization, the samples were subjected to MS/MS analysis and compared with the fragmentation patterns of authentic chitin oligomers (not shown). Each species showed abundant b- and y-type product ions similar to those derived from the standard chitins, indicating cleavage at the glycosidic linkages of a linear chain of GlcNAc residues. To confirm the presence of β(1,4)-linkages, the HexNAc oligomers were treated with Streptomyces griseus chitinase, which degrades chitin in two enzymatic reactions. Chitobiose units are first released by an endo-chitodextrinase/chitinase activity and an exo-N-acetylglucosaminidase/chitobiase activity then cleaves the disaccharides. A MALDI-TOF survey of digestion products at different treatment times (Figure 2A–C) showed decreasing signals for the HexNAc4-6 oligomers. Quantification (Figure 2D) showed that the larger HexNAc4-6 oligomers decreased in abundance with increasing time, whereas the HexNAc1-3 species increased as digestion proceeded. Similarly, treatment of samples with jack bean β-N-acetylhexosaminidase, which is specific for non-reducing end HexNAc(β1,4) linkages, decreased the signal intensity for all the above species (not shown). These results extend the earlier reports that vertebrate representatives of the Class I HAS family produce chitin oligomers when GlcNAc(α1→)UDP is the only sugar nucleotide provided (Semino et al. 1996; Yoshida et al. 2000), to include a prokaryotic member of the family.

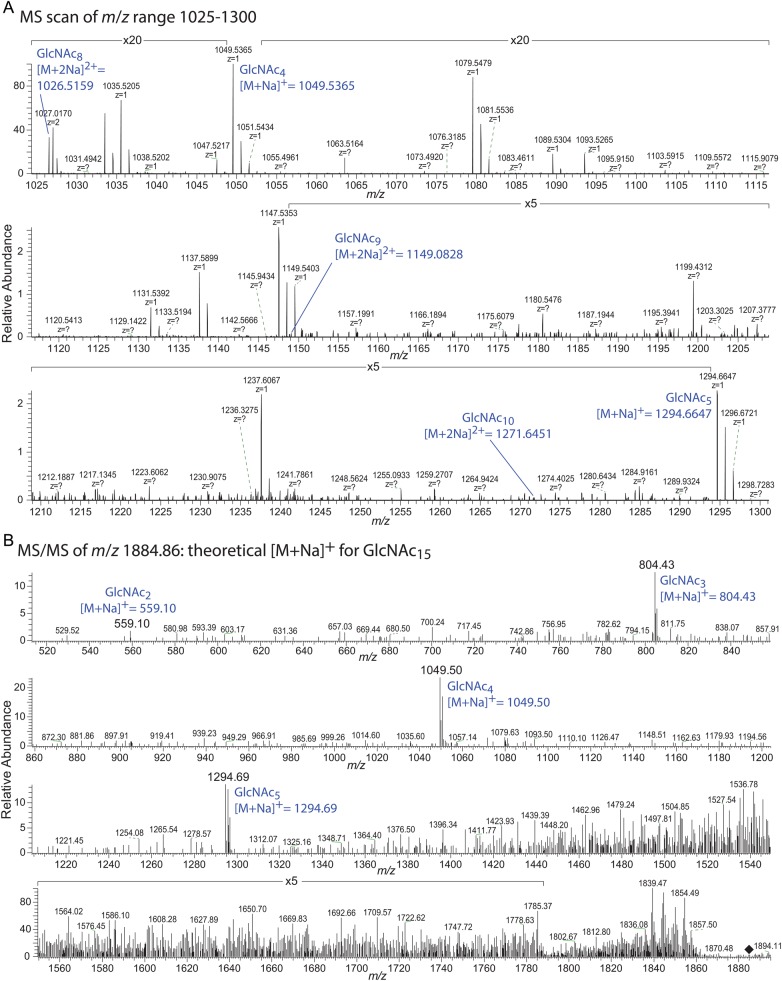

The SeHAS reaction products were further characterized by permethylation and high resolution and high sensitivity electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI MS) on an Orbitrap Fusion MS in positive ion mode. Elution of C18-cartridges with 50% ACN (acetonitrile) yielded predominantly chitin oligomers of expected m/z values up to 10 HexNAc residues (Table III, Figure 3A). Furthermore, MS/MS analysis at m/z values matching higher order oligomers demonstrated the presence of HexNAc15 (Figure 3B). Although it is unclear whether the low abundance of this oligomer is the result of minimal formation or failure to capture by the methods employed, SeHAS clearly has the potential to form extended chitin oligomers in the absence of GlcUA-UDP.

Table III.

MS analysis of permethylated GlcNAc oligomers

| Permethylated species | Found by |

MW | [M+Na]+ |

[M+2Na]2+ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT MS | MS/MS (IT) | Calculated (m/z) | Observed (m/z) | Mass error (ppm) | Calculated (m/z) | Observed (m/z) | Mass error (ppm) | ||

| GlcNAc1 | Yes | No | 291.1682 | 314.1574 | 314.1569 | 1.74 | 168.5733 | ND | NA |

| GlcNAc2 | Yes | Yes | 536.2946 | 559.2838 | 559.2830 | 1.48 | 291.1365 | ND | NA |

| GlcNAc3 | Yes | Yes | 781.4210 | 804.4102 | 804.4098 | 0.50 | 413.6997 | 413.6990 | 1.75 |

| GlcNAc4 | Yes | Yes | 1026.5473 | 1049.5366 | 1049.5365 | 0.08 | 536.2629 | 536.2621 | 1.52 |

| GlcNAc5 | Yes | Yes | 1271.6736 | 1294.6629 | 1294.6647 | −1.42 | 658.8261 | 658.8250 | 1.60 |

| GlcNAc6 | Yes | Yes | 1516.8000 | 1539.7892 | 1539.7953 | −3.93 | 781.3892 | 781.3887 | 0.70 |

| GlcNAc7 | Yes | Yes | 1761.9264 | 1784.9156 | ND | NA | 903.9524 | 903.9518 | 0.70 |

| GlcNAc8 | Yes | Yes | 2007.0527 | 2030.0419 | ND | NA | 1026.5156 | 1026.5159 | −0.32 |

| GlcNAc9 | Yes | Yes | 2252.1790 | 2275.1683 | ND | NA | 1149.0788 | 1149.0828 | −3.51 |

| GlcNAc10 | Yes | Yes | 2497.3054 | 2520.2947 | ND | NA | 1271.6420 | 1271.6451 | −2.47 |

| GlcNAc11 | No | Yes | 2742.4318 | 2765.4210 | ND | NA | 1394.2051 | ND | NA |

| GlcNAc12 | No | Yes | 2987.5581 | 3010.5473 | ND | NA | 1516.7683 | ND | NA |

| GlcNAc13 | No | No | 3232.6845 | 3255.6737 | ND | NA | 1639.3315 | ND | NA |

| GlcNAc14 | No | Yes | 3477.8108 | 3500.8001 | ND | NA | 1761.8947 | ND | NA |

| GlcNAc15 | No | Yes | 3722.9372 | 3745.9265 | ND | NA | 1884.4579 | ND | NA |

Samples were scanned at high resolution in MS mode (positive ion) in the Fusion Orbitrap instrument at high resolution (FT), and selected ions or m/z intervals predicted to include GlcNAc oligomers were subjected to collision-induced decay and analyzed in the ion trap (IT). GlcNAc oligomers detected in MS mode are noted in the second column (FT MS); those detected during MS/MS are noted in the third column (IT). Calculated and observed monoisotopic masses are given together with mass determination errors in ppm. Examples of MS and MS/MS spectra are shown in Figure 3. ND, not detected; NA, not applicable.

Fig. 3.

MS analysis of permethylated HAS-dependent oligomer products. (A) The preparation described in Table III was analyzed in a Thermo Orbitrap Fusion MS in positive ion mode. The m/z range of 1025–1300 is shown, where five ions corresponding to singly charged and sodiated GlcNAc4,5 or doubly charged and sodiated GlcNAc8-10 species were detected. (B) MS/MS analysis of a permethylated putative GlcNAc15 species at m/z 1884.86 (black diamond). The four daughter ions shown confirm the multiple HexNAc composition of the parent ion.

SeHAS synthesizes GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers

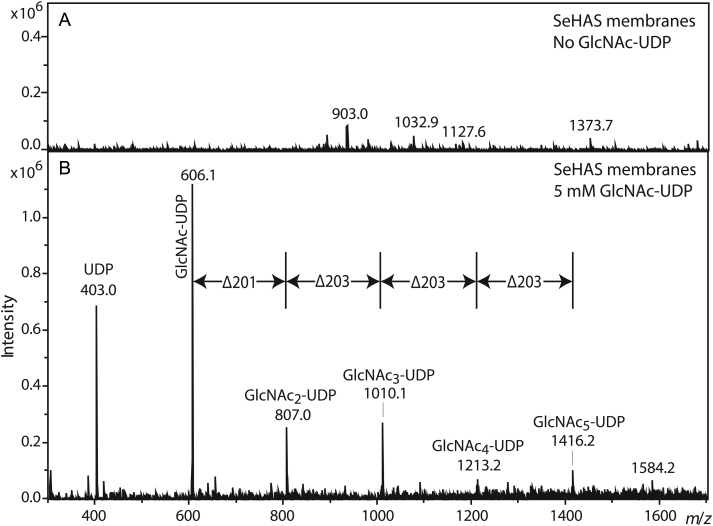

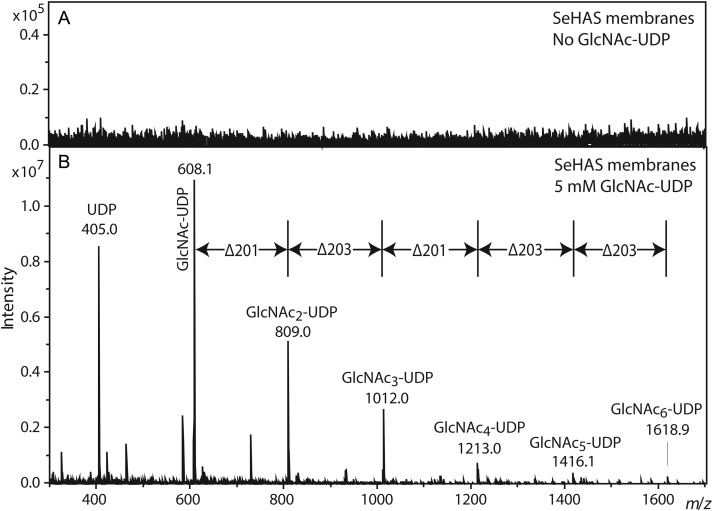

Activated charcoal-enriched samples from SeHAS membranes were incubated, processed in the absence of glycerol and analyzed by ESI MS operated in negative ion mode. As expected, SeHAS membranes without GlcNAc(α1→)UDP (not shown) or EV membranes incubated with GlcNAc(α1→)UDP (Figure 4A) showed no signals. In contrast, SeHAS membranes incubated with GlcNAc(α1→)UDP yielded a distinct series of [M-H]– ions as observed in MALDI-TOF MS (Figure 4B), most of which were spaced by 203 mu. Ions corresponding to UDP (403.0) and GlcNAc-UDP (403 + 203 = 606.1) were readily detected. However, a prominent ion expected to correspond to GlcNAc2-UDP exhibited an m/z value that was 2 mu less than expected (403 + 203 + 203 − 2 = 807.1). Ions corresponding to up to three additional GlcNAc units were detected, but each exhibited the same –2 mu mass defect (Figure 4B, Table IV). The putative UDP-conjugated ions were not detected in the presence of glycerol, nor were they detected in the WGA affinity enriched preparations (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Negative ion mode MS analysis of GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers made by HAS. SeHAS membranes were incubated without (A) or with (B) GlcNAc-UDP. Samples were processed as described in the Materials and methods section, and then examined by ESI MS in negative ion mode. The m/z species corresponding to the predicted values for GlcNAcn-UDP are labeled and those signals separated by 203 mu (one GlcNAc) are indicated by vertical lines. All ions are (M-H)– and are listed in Table IV.

Table IV.

Monoisotopic m/z values of GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers

| Species | [M-H]– |

Mass defect | [M+H]+ |

Mass defect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Observed | Predicted | Observed | |||

| UDP | 403.0 | 403.0 | 0 | 405.0 | 405.0 | 0 |

| GlcNAc-UDP | 606.1 | 606.1 | 0 | 608.1 | 608.1 | 0 |

| (GlcNAc)2-UDP | 809.2 | 807.1 | −2.1 | 811.2 | 809.0 | −2.2 |

| (GlcNAc)3-UDP | 1012.2 | 1010.1 | −2.1 | 1014.2 | 1012.0 | −2.2 |

| (GlcNAc)4-UDP | 1215.3 | 1213.2 | −2.1 | 1217.3 | 1213.0 | −4.3 |

| (GlcNAc)5-UDP | 1418.4 | 1416.2 | −2.2 | 1420.4 | 1416.1 | −4.3 |

| (GlcNAc)6-UDP | 1621.5 | 1619.3 | −2.2 | 1623.5 | 1618.9 | −4.6 |

| (GlcNAc)7-UDP | 1824.6 | ND | 1826.6 | ND | ||

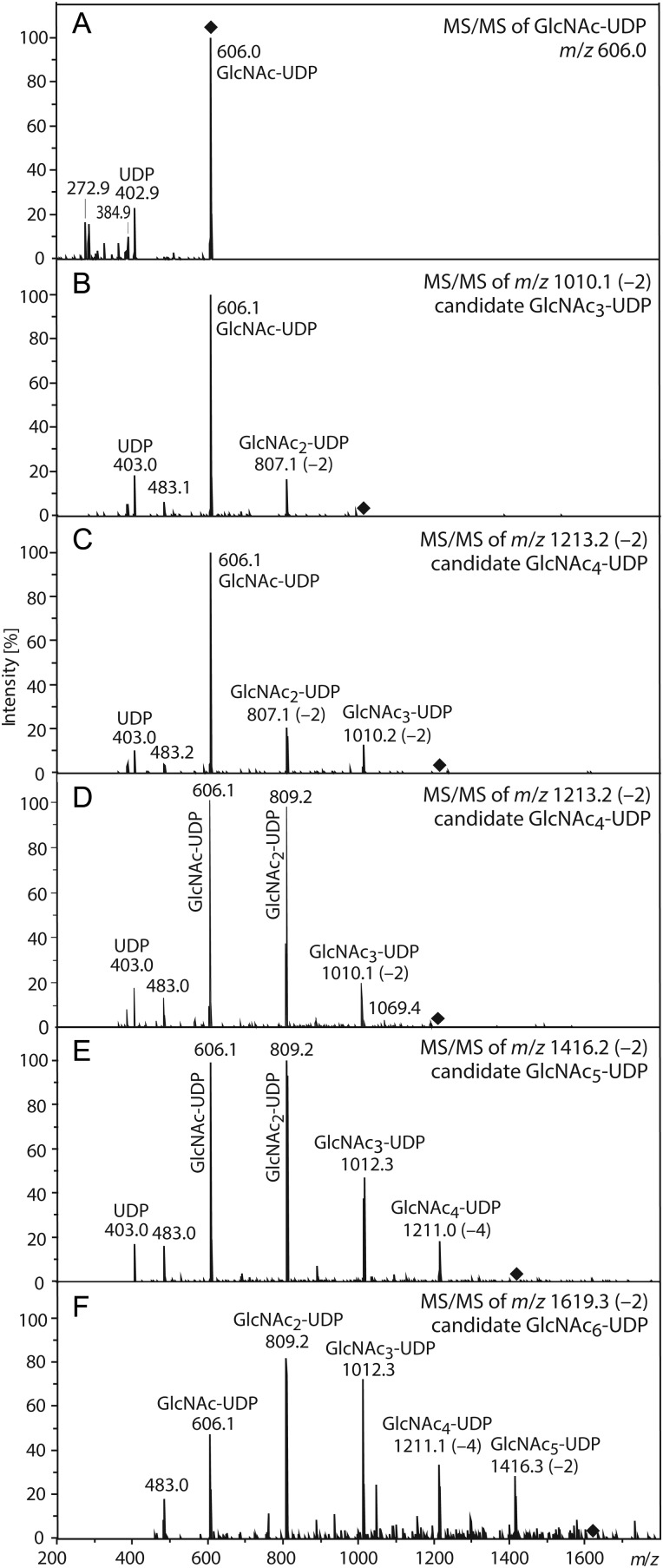

Similar results were obtained using ESI MS in positive ion mode, except that a variation in the mass defect was observed (Figure 5, Table IV). In this case, a second mass defect of –2 was observed for the three GlcNAc4-6-UDP species. Since the same sample was used for both negative and positive ion mode analyses, and because the free GlcNAc oligomers did not exhibit mass defects, the occurrence of a mass loss indicates that at least the second mass defect (and probably the first defect) was derived from a gas-phase chemical reaction that depended on the associated UDP-moiety. Collision-induced dissociation (CID)-induced negative ion mode fragmentation of each GlcNAc3-6-UDP oligomer (Figure 6) yielded fragments corresponding to UDP (402.9) and GlcNAc-UDP (606.0) ions, indicating that the mass defects occurred in the sugars, not in UDP. The putative GlcNAc3-UDP ion (1010.1) with a −2 defect yielded a fragment ion at 807.1, indicating that the mass defect required the third sugar but occurred in the second sugar (Figure 6B). For the putative GlcNAc4-UDP species (1213.2), the mass defect mapped to either the putative GlcNAc2-UDP daughter ion (Figure 6C) or the GlcNAc3-UDP daughter ion (Figure 6D) in different trials. The putative GlcNAc5-UDP ion (1416.2) yielded a different pattern, in which a prominent GlcNAc3-UDP product ion with no mass defect was observed, but the putative GlcNAc4-UDP product (1211.0) exhibited a –4 mass defect (Figure 6E). Since the parent ion had a mass defect of only –2, the second –2 defect must have occurred during gas-phase fragmentation. A similar result was found for the putative GlcNAc6-UDP ion (1619.3). The variable position of the original mass defect in GlcNAc4-UDP, as indicated by MS/MS analysis, and the acquisition of a second mass defect in MS/MS (summarized in Table V) indicates that these mass changes occurred during MS analysis itself.

Fig. 5.

Positive ion mode MS analysis of GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers made by HAS. SeHAS membranes were incubated without (A) or with (B) GlcNAc-UDP; samples were processed as in Figure 1 and in the Materials and methods section, and then examined by ESI MS in positive ion mode. The m/z species corresponding to expected and observed values for GlcNAcn-UDP (Table IV) are indicated with labels and those separated by 203 Da (one GlcNAc) are indicated by vertical lines; all ions are (M+H)+.

Fig. 6.

MS/MS fragmentation of GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers. SeHAS membranes were incubated with GlcNAc-UDP and processed as described in the Materials and methods section to enrich for GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers. (A) Standard GlcNAc-UDP alone. Samples were subjected to ESI MS in negative ion mode, and candidate GlcNAcn-UDP m/z species for n = 3, 4, 5 and 6 at 1010 (B), 1213 (C and D), 1416 (E) and 1619 (F) m/z, respectively, and then subjected to CID. (C) and (D) represent independent replicates. Fragment signals corresponding to GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers (n = 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5) species, and observed m/z values, are indicated and listed in Table V. Mass defects are denoted in parentheses. The parent ion position is indicated by black diamonds.

Table V.

MS/MS analyses of GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers

| Oligomer species | [M-H]– predicted | Parent ion 1010.1 (−2.1) GlcNAc3-UDP | Parent ion 1213.2 (−2.1) GlcNAc4-UDP | Parent ion 1416.2 (−2.2) GlcNAc5-UDP | Parent ion 1619.3 (−2.2) GlcNAc6-UDP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UDP | 403.0 | 402.9 | 403.0 | 403.0 | – |

| GlcNAc-UDP | 606.1 | 606.1 | 606.1 | 606.1 | 606.1 |

| GlcNAc2-UDP | 809.2 | 807.1 (−2.1) | 807.1 (−2.1)/809.2 | 809.2 | 809.2 |

| GlcNAc3-UDP | 1012.2 | – | 1010.2 (−2.0)/1010.1 (−2.1) | 1012.3 | 1012.3 |

| GlcNAc4-UDP | 1215.3 | – | – | 1211.0 (−4.3) | 1211.1 (−4.2) |

| GlcNAc5-UDP | 1418.4 | – | – | – | 1416.3 (−2.1) |

| GlcNAc6-UDP | 1621.5 | – | – | – | – |

Negative ion mode MS/MS analyses (using a Bruker Esquire HCT ion trap MS) were performed on GlcNAc3-6-UDP species as shown in Figure 6. The collected parent ion and product ion m/z values (monoisotopic) are listed in each column below the selected parent ion with mu differences indicated in parentheses. Values in italic font denote product species with greater mass differences than the parent ions, indicating that a gas phase reaction resulted in a second 2 mu loss during MS/MS analysis. Dual entries indicate results obtained from two different trials.

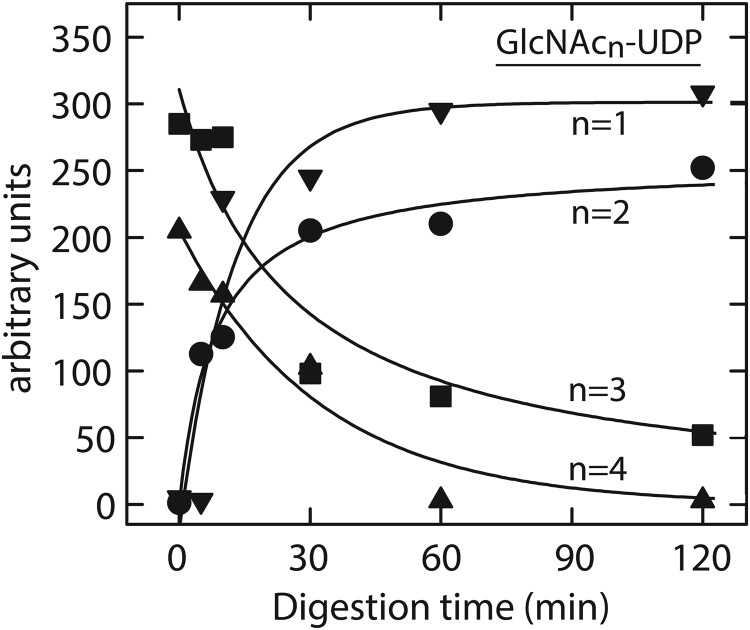

Enzymatic characterization of HexNAcnHexNAc(α1→)UDP oligomers synthesized by SeHAS

The results in Figures 4–6 and Tables IV and V support the conclusion that the species with mass differences are not present in samples prior to MS analysis and are most likely generated after ionization. As a check on this interpretation, the GlcNAcn-UDP samples were tested for sensitivity to jack bean β-N-acetylhexosaminidase. The longer products were first enriched by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to exclude GlcNAc-UDP and GlcNAc2-UDP. Enzyme treatment resulted in time-dependent loss of the 3- and 4-mer species, and an accumulation of 2- and 1-mer species (Figure 7). Based on the specificity of the enzyme for β-linked HexNAc residues at the non-reducing end, this result confirms the β-linkage of HexNAc residues, which are known to be GlcNAc based on GlcNAc-UDP substrate dependence, the chitinase sensitivity of the free oligomers and linkage of UDP at the reducing terminus as predicted.

Fig. 7.

Jack bean N-acetylhexosaminidase releases GlcNAc from GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers and generates smaller members of the series. Samples prepared as in Figure 1 were further enriched for particular GlcNAcn-UDP species by SEC fractionation and MS screening as described in the Materials and methods section. An SEC fraction containing predominantly GlcNAc3-UDP and GlcNAc4-UDP was treated with N-acetylglucosaminidase and analyzed by MS as in Figure 5. The kinetics of signal intensity changes for the indicated GlcNAc1-4-UDP species (n = 1, inverted filled triangle; n = 2, filled circle; n = 3, filled square; n = 4, filled triangle) were determined as a function of digestion time.

Discussion

Our MS analyses results confirm that enzymes of the Class I HAS family produce chitin oligomers in the presence of GlcNAc-UDP and the absence of the other acceptor substrate GlcUA-UDP and document that these oligomers may contain at least 15 GlcNAc residues. However, the preferred or average oligomeric chitin-UDP size made by HAS is not known and cannot be determined from these MS data alone. The results also confirm the hypothesis that these oligomers are first made as chitin-UDP oligomers, which are novel previously unknown products of HAS. In addition to the expected instability of chitin-UDP oligomers, these species behaved in several other unanticipated ways during sample preparation, WGA fractionation and MS analysis.

Chitin-UDP oligomers do not bind to WGA

WGA is a tetramer with multiple binding sites of varying affinities and the ability to bind a ligand at adjacent sites 14–16 Å apart (Wright and Kellogg 1996; Wittmann and Pieters 2013). Although control chitin oligomers were readily bound to WGA and thus enriched substantially by affinity chromatography (Figure 2), chitin-UDP oligomers of similar size were not detected by this method. We interpret the apparent inability of chitin-UDP oligomers to bind WGA to reflect either interference by the UDP group with alignment and binding of an attached chitin oligomer or the presence of some intramolecular tertiary structure that hinders binding. An alternative possibility is that the chitin-UDP oligomers bound irreversibly to the WGA column and were not released; this could not be tested, since high-salt flow-through fractions could not be analyzed successfully by MS. This possibility, in itself, also supports the presence of a novel conformation of the chitin portions of the chitin-UDP species. Based on all the above results, including the mass-loss trend noted in Table IV, we propose that species as small as GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcNAc(α1→)UDP can adopt a fold-over or hairpin end-to-end conformation, in which terminal non-reducing GlcNAc(s) interacts with UDP, so that the remaining chitin region is not available to interact with WGA. As chain length increases, longer oligomers could form similar complexes between the reducing end UDP and GlcNAc near or at the non-reducing terminus, resulting in successively longer loops that would not be able to bind WGA. If such intramolecular complexes form, they must be relatively stable in solution (and likely also in the gas phase during MS analysis), since a rapid equilibrium situation should enable WGA to trap transiently unfolded species and this does not occur.

Chitin-UDP oligomers are cleaved during concentration in the presence of glycerol

A second unexpected behavior of chitin-UDP oligomers was that MS analysis revealed a product series, not made by EV membranes, which did not correspond to the m/z values for a chitin-UDP oligomer series. However, the series showed 203 mu spacing (one GlcNAc differences), indicating that this was a modified chitin oligomer series of GlcNAcn + 74 Da. We tested the possibility that chitin-UDP oligomers might be so labile that a cleavage or displacement reaction occurred during sample processing (i.e. speed vacuum concentration) in the presence of glycerol, releasing UDP and creating a β-glyceryl glycoside of chitin (i.e. the chitin + 74 series). Possible mechanisms are an SN2-like displacement reaction [1], or a cleavage-rearrangement of the

α1-linked GlcNAc between C3-C4 and C1-O that creates two products: a C[1-2-3] fragment either free or still attached to UDP and a chitin oligosaccharide with a glyceryl aglycone. The first well known mechanism seems more likely, especially since the glycerol CH2OH level after vacuum concentration could exceed 5 M. The GlcNAcn-glyceryl product in reaction [1] is 74 Da greater than the GlcNAcn glycone. When glycerol was reduced from 20 to 2% or eliminated, the chitin + 74 series products were greatly reduced or essentially absent and the expected chitin-UDP m/z signals were finally evident. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that a displacement reaction occurs in which glycerol displaces (α1→)-UDP to release UDP and add a glyceryl group as an aglycone to the chitin oligomer. Thus, these HAS-dependent chitin+74 products provide indirect evidence for the presence of the chitin-UDP oligomer series.

MS analyses show 2–4 mu mass losses proportional to chitin-UDP oligomer size

The most perplexing behavior of the novel chitin-UDP oligomers identified here was the loss of 2 or 4 mu in both MALDI and ESI MS experiments, representing dehydrogenations. Standard chitin oligomers did not show any Δmu products, indicating that the presence of UDP at the reducing end is a factor in generation of mass-altered products. As chitin-UDP length increased, the Δmu observed also increased (Table IV), indicating that susceptibility to the Δ2 mu modification occurs in a size-dependent manner and does not involve modification of ribose or uracil in the UDP (or there would only be a single reaction product). MS/MS analysis of these lower mass parent ions showed the expected products for the smaller series members, especially the presence of GlcNAc-UDP in all species (Figure 6 and Table IV), supporting the biochemical identification of a series of GlcNAc(β1,4)-linked oligomers attached to UDP. Although there was no difference using a variety of sample matrices and a wide range of laser power settings, we conclude that the mass loss occurs during MS analysis, because parent ions for the n = 5 and n = 6 oligomers showed only a 2-mu loss, yet they yielded n = 4 oligomers with 4 mu losses (Table V; italic font). In support of this conclusion, the recognition of candidate oligomer species by jack bean β-N-acetylglucosaminidase was normal (e.g. Figure 7), ultimately yielding GlcNAc-UDP, indicating that the starting samples are normal and the 2–4 mu loss does not occur during sample preparation. Based on all the above findings, we suggest that the formation of the Δmu product(s) originates from the same intramolecular interaction that interferes with the binding of chitin-UDP oligomers to WGA (e.g. formation of an end-to-end hairpin complex). To our knowledge and based on input from other MS users, the observed mass loss behavior has not been reported or seen with other types of glycans and is likely related to the novel nature of these chitin-UDP oligomer species.

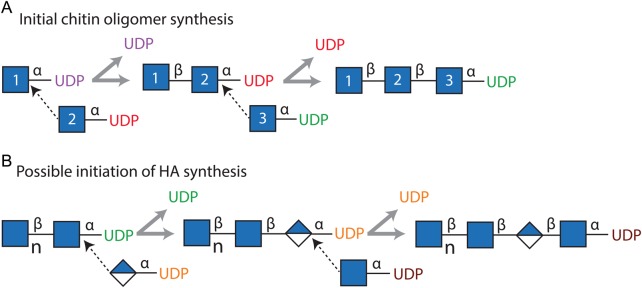

The overall mechanism for oligomeric chitin-UDP synthesis identifies new HAS enzyme functions

The results reported here demonstrate that Class I HAS enzymes possess several activities not previously recognized. The repeating [GlcUA(β1,3)GlcNAc(β1,4)] disaccharide structure of HA requires that HAS possess two transferase activities (Table IA), yet the enzyme also has the ability to transfer GlcNAc(β1,4) to GlcNAc(α1→)UDP and thus make chitin linkages. Not recognized previously, however, is that since HAS adds new sugar monomers to the reducing end, the initial GlcNAc oligomeric products could not be chitin, but rather must be chitin-UDP. The present study verifies this hypothesis. To make these UDP-activated species, HAS must have two additional binding sites and two additional activities (Table VIA). In addition to the seven functions noted in Table IA, HAS can bind GlcNAc(α1→)UDP in a donor site (Table VIA, Function 8) and also bind GlcNAc(β1,4)nGlcNAc(α1→)UDP (Table VIA, Function 9) in a donor site. These two sites could be independent or identical, with flexibility to accommodate a successively longer glycan oligomer.

Table VI.

Newly recognized binding and activity functions of HAS required for the synthesis of chitin-UDP oligomers by a reducing end mechanism

| A. Additional functions of HASs for the synthesis of chitin(α1→)UDP oligomers: |

| 8. GlcNAc(α1→)UDP donor binding site |

| 9. GlcNAc(β1,4)nGlcNAc(α1→)UDP donor binding site |

| 10. GlcNAc(α1→)UDP: GlcNAc(α1→)UDP, GlcNAc(β1,4) transferase activity |

| 11. GlcNAc(β1,4)n(α1→)UDP: GlcNAc(α1→)UDP, [GlcNAc(β1,4)]n transferase activity |

| B. HAS reactions for synthesis of (GlcNAc-β1,4)n-GlcNAc(α1→)UDP oligomer: |

| C. HAS function needed to synthesize the first hyaluronan disaccharide at non-reducing end: |

| 12. GlcNAc(β1,4)n(α1→)UDP: GlcUA(α1→)UDP, [GlcNAc(β1,4)]n transferase activity |

(A) In addition to the seven functions noted in Table I, at least four new functions identified in this study can be attributed to HAS (numbering is continued from Table I): the ability to bind GlcNAc(α1→)UDP (Function 8) and (GlcNAc-β1,4)n-GlcNAc(α1→)UDP (Function 9) in related or independent donor sites. Two novel transferase activities not previously associated with HAS are required: (i) to synthesize a disaccharide (Function 10) by transfer of GlcNAc from GlcNAc(α1→)UDP to a second GlcNAc(α1→)UDP to create GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcNAc(α1→)-UDP (chitobiosyl-UDP) and (ii) to transfer, in successive repeating additions (Function 11) (GlcNAc-β1,4)n-GlcNAc from (GlcNAc-β1,4)n-GlcNAc(α1→)-UDP to GlcNAc(α1→)UDP to yield (GlcNAc-β1,4)n+1-GlcNAc(α1→)-UDP. (B) The general reactions for the synthesis of (GlcNAc-β1,4)n-GlcNAc(α1→)UDP oligomers. The scheme shows the overall reactions for synthesis of an initial chitobiosyl-UDP disaccharide (top reaction) and the series of (GlcNAc-β1,4)n-GlcNAc(α1→)-UDP oligomer products (bottom reaction). (C) If oligomeric chitosyl-UDP serves as a primer for HA synthesis, then a single additional transferase activity (Function 12) would be needed to begin HA synthesis (i.e. to create the first HA disaccharide) by adding the chitin oligosaccharide to GlcUA-UDP to create the first GlcUA residue at the non-reducing end. These reactions are illustrated schematically in Figure 8.

A novel HAS transferase activity (Table VIA, Function 10) synthesizes a N,N'diacetylchitobiosyl-UDP disaccharide [GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcNAc(α1→)-UDP] by transfer of GlcNAc from GlcNAc(α1→)UDP to a second GlcNAc(α1→)UDP; this is a GlcNAc(α1→)UDP:GlcNAc(α1→)UDP, GlcNAc(β1,4) transferase. The second novel HAS activity (Table VIA, Function 11) transfers (GlcNAc-β1,4)n-GlcNAc- from (GlcNAc-β1,4)n-GlcNAc(α1→)UDP to GlcNAc(α1→)UDP to yield (GlcNAc-β1,4)n+1-GlcNAc(α1→)-UDP. This activity is a [GlcNAc(β1,4)]n(α1→)UDP:GlcNAc(α1→)UDP, [GlcNAc(β1,4)]n transferase that functions in successive cycles to create a series of linear oligomeric products with up to at least 15 GlcNAc(β1,4) residues. The overall reactions for synthesis of these species by HAS is shown in Table VIB and Figure 8 shows a schematic illustration of how HAS assembles oligomeric chitin-UDP products using the novel functions reported here.

Fig. 8.

Schematic illustration of HAS enzyme reactions responsible for synthesis of chitin-UDP oligomers and their potential role as primers for HA assembly. (A) The scheme illustrates the synthesis of GlcNAc3-UDP in which HAS utilizes three GlcNAc(α1→)UDP molecules (blue squares, numbered 1–3) in two successive reactions that each releases free UDP (purple and then red) and a third reaction that assembles an oligomer with two (β1,4)-linked GlcNAc residues (numbers 1 and 2) attached to GlcNAc (number 3), whose reducing end remains attached to UDP (green) by the original (α1→) linkage. The dotted line arrows indicate the C4-OH of each GlcNAc-UDP acceptor reacting with the C1 of each UDP-activated donor to displace the (α1→)-linked UDP and create a new inverted GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcNAc linkage. (B) Possible initiation of HA synthesis if chitin-UDP oligomers made by HAS can serve as primers. HAS could extend a [GlcNAc(β1,4)]nGlcNAc(α1→)UDP oligomer (left) to initiate HA synthesis by addition of GlcUA(α1→)UDP (blue–white diamond) to the reducing end to create [GlcNAc(β1,4)]n+1GlcUA(α1→)UDP (middle). Addition of GlcNAc(α1→)UDP would then extend the chain and define the preceding disaccharide as the first HA repeat unit [far right product; GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcUA]. Such products would further polarize the HA polysaccharide by leaving a non-HA component, an oligomeric chitin cap, at the older non-reducing end.

The significance of chitin-UDP oligomeric products

Although Class I HAS enzymes display many binding or transferase functions in a single protein, no one has determined how these enzymes initiate HA chain synthesis. The present results show that with only GlcNAc(α1→)UDP present, HAS adds a series of β(1,4)-linked GlcNAc residues, from GlcNAc(α1→)UDP to a growing GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcNAc(α1→)UDP acceptor to create (GlcNAcβ1,4)nGlcNAc(α1→)UDP. Chitin-UDP products have not been identified before and, in comparison, cellulose (Koyama et al. 1997) and chitin (Dorfmueller et al. 2014) synthases may add sugars at the non-reducing end, despite a shared ancestry with HAS enzymes. Chitin-UDP oligomers are expected to be unstable, hydrolyzing to release either UDP and free chitin oligomers or possibly UMP and chitin-PO4 oligomers. The latter product might be processed further by phosphatases to yield chitin oligomers and free phosphate. Intracellular chitin-UDP products released by HAS might also be substrates for cleavage by cellular phosphodiesterases or for a novel, as yet unknown, oligo-chitosyltransferase.

The significance of HAS being able to create free chitin or chitin-UDP oligomers is two-fold. First, as recognized earlier (Semino et al. 1996; Yoshida et al. 2000), chitin oligomers have multiple roles during developmental processes in lower vertebrates and mammalian development might similarly use chitin oligomers as signaling regulators. However, in mammals, these products could be made by HAS rather than a chitin synthase, since the human genome does not contain the latter. The present results also make it highly likely that HAS enzymes evolved from chitin-like synthases, consistent with protein sequence phylogenies.

A second, very intriguing and important, possible purpose for the synthesis of chitin-UDP oligomers is that they could be extended by the normal HAS activity of the enzyme; that is, the chitin-UDP products could function as self-primers for HA synthesis. In this case, all growing and newly released HA-UDP chains would contain a unique and unexpected non-HA structure, the residual chitin oligomer primer, at their non-reducing ends that reside extracellularly during biosynthesis. If the chitin oligomers self-associate while connected to the HA polymers, this could influence or have unexpected effects on the extracellular organization of HA. In order for the enzyme to utilize a chitin-UDP oligomer as a primer for HA synthesis, one additional activity would be needed (Table VIC; Function 12) to add the first GlcUA to create the first HA disaccharide; this linkage would define a unique start (i.e. register) and the first HA disaccharide as GlcNAc(β1,3)GlcUA(β1,4) for a newly initiated HA chain that HAS could then assemble using the previously identified functions (Table I). In ongoing studies, we find preliminary evidence for such chitin oligomer “caps” at the non-reducing end of HA chains made by SeHAS (Feasley et al. 2013).

Materials and methods

Materials, reagents and buffers

All water used was purified by reverse osmosis or distillation followed by deionization and charcoal adsorption. Streptomyces griseus chitinase (C6137) and Jack bean β-N-acetylhexosaminidase (A2264) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Bradford reagent (#23239) was from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Sep-Pak C18-cartridges (100 mg) were from Waters (Milford, MA) and activated charcoal (Carbograph) cartridges used for solid-phase extraction were from Alltech Associates (Deerfield, IL). WGA-agarose micro-lectin affinity columns (7 mg/mL) and chitin oligosaccharides were from Vector Labs (Burlingame, CA). The Superdex 75 peptide column (10/300 GL) was from GE Life Science (Piscataway, NJ).

HAS membrane preparation and synthesis of GlcNAcn-UDP or chitin oligomers

Escherichia coli SURE2 cells containing EV or vector with the SeHAS gene were grown, harvested and membranes prepared as reported in Tlapak-Simmons et al. (1999) with slight modifications. Membranes (1–1.5 g total protein) were resuspended to 7–10 mg/mL protein in 25 mM sodium-potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, 75 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM N,N,N′,N′-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 20 mM MgCl2 and with or without 2% glycerol. Protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (1976). GlcNAc-UDP was added to 200 µL of SeHAS-membrane suspension (350–500 µg/mL HAS) to a final concentration of 1–5 mM and incubated at 30°C for 30–120 min. The reaction was stopped by adding an equal volume of 25 mM phosphate buffer with 150 mM NaCl and then 1.2 mL of chloroform:methanol (2:1). The mixture was extracted once as described by Folch et al. (1957) by vortex mixing at 22°C for 5 min and then centrifuging for 5 min at 10,000 × g. The aqueous layer was transferred to a Speed Vacuum concentrator and dried to a final volume of 50–100 µL.

Affinity selection of chitin oligomers

Folch-extracted samples (50 µL) were mixed with 50 µL of 100 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.0, applied to a WGA-agarose column (70 µL bed volume) and the flow-through was collected and reapplied to the column three more times. The column was then washed with 300 µL of 25 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.0, and the wash and flow-through fractions were pooled. GlcNAc oligomers bound to WGA were eluted with 250 µL of 100 mM acetic acid and vacuum centrifuged to dryness. Folch-extracted membrane or WGA flow-through samples were diluted with an equal volume of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water and applied to a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge pre-equilibrated with sequential 3 mL washes of methanol, water, 50% ACN/0.1% TFA in water and 0.1% TFA in water. Three 250 µL washes with 0.1% TFA in water were pooled with the flow-through and applied to an activated charcoal cartridge, pre-equilibrated as above and washed with 4 mL of 0.1% TFA in water. GlcNAcn and GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers were eluted with four successive aliquots of 250 µL of 50% ACN/0.1% TFA in water. Eluted oligomers were dried by vacuum centrifugation before MS analysis.

Glycosidase digestion of chitin or GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers

GlcNAcn or GlcNAcn-UDP oligomers (0.1-1 nmol) in 10 µL of 25 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.0, were mixed with 1 µL (0.1 µU) of S. griseus chitinase or 1 µL of jack bean N-acetylhexosaminidase (first dialyzed for 1 h at 25°C against 25 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.0). The samples were then incubated at 37°C for 0–240 min, and 1 µL was removed at the indicated times for MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

Size-exclusion chromatography

Standard chitin oligomers and GlcNAc oligomeric species produced by SeHAS and enriched as described in the preceding section were fractionated on a Superdex Peptide HR10/30 column equilibrated in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 7.8, using an AKTA Basic HPLC (GE Life Science). Approximately 0.1 mg of total oligomers (25–50 µL) was injected onto the column at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min and 500 µL fractions were collected for one column volume; eluting oligosaccharides were monitored at 205 nm. Fractions were either analyzed directly by MALDI-TOF MS or first concentrated by vacuum centrifugation. For experiments in Figure 7, SEC fractions were subjected to MS screening in positive ion mode to identify smaller and larger GlcNAcn-UDP species; fractions 27–30 were of most interest, since many species were present. Fraction 27 was chosen for further analysis, since it contained weak or no signals for GlcNAc-UDP and GlcNAc2-UDP but clear signals for GlcNAc3-5-UDP.

MALDI-TOF MS analysis

Samples (1 µL in 50% ACN/0.1% TFA in water) were spotted on polished steel target plates with 1 µL of 10 mg/mL 2,5-dihydrobenzoic acid as a matrix and analyzed in Reflectron positive or negative ion mode (with an accelerating voltage of 25 kV for positive ion mode and 23.2 kV for negative ion mode) in a Bruker Ultraflex II MALDI-TOF-TOF (Billerica, MA). For each sample, ≥1000 individual summed shots were accumulated, collected in 100 shot sections and summed. Data were processed using Bruker Flex Analysis v2.4 software for peak identifications and any smoothing functions.

ESI MS analysis of non-derivatized samples

Extracted membrane samples were dissolved in 50% ACN/50% water or 50% methanol/50% water and analyzed using a Bruker Esquire HCT MS (Billerica, MA) with a direct infusion rate of 300 µL/h and the instrument set at alternating voltage and manual MSN isolation, selection and fragmentation.

MS analysis of permethylated GlcNAc oligomers

Dried samples were resuspended in 1 mM NaOH in 50% methanol and directly infused into an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) using the standard instrument software (Tune 1.0). Full MS scans were collected from m/z 200–2000 at a resolution of 120,000 (Full width at half maximum at m/z 200), with a maximum ion injection time of 200 ms, and an automatic gain control setting of 2 × 105 ions. MS/MS scans were collected in the ion trap via CID using 40% normalized collisional energy, with a maximum injection time of 200 ms for three microscans (three microscans per MS/MS scan) and an automatic gain control of 3 × 104. Data acquisition was conducted using Xcalibur® (ver. 3.0.49, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the fashion of one Orbitrap full MS followed by top 40 data-dependent ion trap CID MS/MS in each of the following m/z ranges: 1500–2000, 1200–1550, 1000–1250, 700–1050 and 300–750.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM35978) from the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Abbreviations

ACN, acetonitrile; CID, collision-induced dissociation; ESI, electrospray ionization; EV, empty vector; GlcNAc, N-acetyl-d-glucosamine; GlcUA, d-glucuronic acid; HA, hyaluronic acid, hyaluronate, hyaluronan; HAS, HA synthase; MALDI-TOF. matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight; MS, mass spectrometry mu, mass unit; m/z, mass:charge ratio; SEC, size-exclusion chromatography; SeHAS, Streptococcus equisimilis HAS; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; WGA, wheat germ agglutinin.

Acknowledgements

We thank Christa Feasley for mass spectroscopic analyses.

References

- Asplund T, Brinck J, Suzuki M, Briskin MJ, Heldin P. 1998. Characterization of hyaluronan synthase from a human glioma cell line. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 1380:377–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggenstoss BA, Weigel PH. 2006. Size exclusion chromatography-multiangle laser light scattering analysis of hyaluronan size distributions made by membrane-bound hyaluronan synthase. Anal Biochem. 352:243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodevin-Authelet S, Kusche-Gullberg M, Pummill PE, DeAngelis PL, Lindahl U. 2005. Biosynthesis of hyaluronan: Direction of chain elongation. J Biol Chem. 280:8813–8818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 72:248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis PL, Weigel PH. 1994. Immunochemical confirmation of the primary structure of streptococcal hyaluronan synthase and synthesis of high molecular weight product by the recombinant enzyme. Biochemistry. 33:9033–9039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfmueller HC, Ferenbach AT, Borodkin VS, van Aalten DM. 2014. A structural and biochemical model of processive chitin synthesis. J Biol Chem. 289:23020–23028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feasley CL, Baggenstoss BA, Weigel PH. 2013. (GlcNAc)n-UDP oligomer synthesis by Class I hyaluronan synthase and its role as a self priming initiator for hyaluronan synthesis. The 9th International Conference on Hyaluronan, Hyaluronan http://www.ishas.org/images/2013_Conference/ISHAS_2013_Book_of_Abstracts.pdf. (last accessed 22 January 2015) p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama M, Helbert W, Imai T, Sugiyama J, Henrissat B. 1997. Parallel-up structure evidences the molecular directionality during biosynthesis of bacterial cellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 94:9091–9095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ontong P, Hatada Y, Taniguchi S, Kakizaki I, Itano N. 2014. Effect of a cholesterol-rich lipid environment on the enzymatic activity of reconstituted hyaluronan synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 443:666–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prehm P. 1983. Synthesis of hyaluronate in differentiated teratocarcinoma cells. Mechanism of chain growth. Biochem J. 211:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prehm P. 2006. Biosynthesis of hyaluronan: Direction of chain elongation. Biochem J. 398:469–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakr SW, Potter-Perigo S, Kinsella MG, Johnson PY, Braun KR, Goueffic Y, Rosenfeld ME, Wight TN. 2008. Hyaluronan accumulation is elevated in cultures of low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient cells and is altered by manipulation of cell cholesterol content. J Biol Chem. 283:36195–36204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semino CE, Specht CA, Raimondi A, Robbins PW. 1996. Homologs of the Xenopus developmental gene DG42 are present in zebrafish and mouse and are involved in the synthesis of Nod-like chitin oligosaccharides during early embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 93:4548–4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlapak-Simmons VL, Baggenstoss BA, Clyne T, Weigel PH. 1999. Purification and lipid dependence of the recombinant hyaluronan synthases from Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus equisimilis. J Biol Chem. 274:4239–4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tlapak-Simmons VL, Baron CA, Gotschall R, Haque D, Canfield WM, Weigel PH. 2005. Hyaluronan biosynthesis by Class I streptococcal hyaluronan synthases occurs at the reducing end. J Biol Chem. 280:13012–13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel PH. 2002. Functional characteristics and catalytic mechanisms of the bacterial hyaluronan synthases. Int Union Biochem Mol Biol. 54:201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel PH, Baggenstoss BA. 2012. Hyaluronan synthase polymerizing activity and control of product size are discrete enzyme functions that can be uncoupled by mutagenesis of conserved cysteines. Glycobiology. 22:1302–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel PH, DeAngelis PL. 2007. Hyaluronan synthases: A decade-plus of novel glycosyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 282:36777–36781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel PH, Kyossev Z, Torres LC. 2006. Phospholipid dependence and liposome reconstitution of purified hyaluronan synthase. J Biol Chem. 281:36542–36551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann V, Pieters RJ. 2013. Bridging lectin binding sites by multivalent carbohydrates. Chem Soc Rev. 42:4492–4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CS, Kellogg GE. 1996. Differences in hydropathic properties of ligand binding at four independent sites in wheat germ agglutinin-oligosaccharide crystal complexes. Protein Sci. 5:1466–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Itano N, Yamada Y, Kimata K. 2000. In vitro synthesis of hyaluronan by a single protein derived from mouse HAS1 gene and characterization of amino acid residues essential for the activity. J Biol Chem. 275:497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]