Abstract

Prostaglandin H2 not only serves as the common precursor of all other PGs, but also directly triggers signals (eg. platelet aggregation), depending on its location and translocation. The prostaglandin carrier PGT mediates the transport of several prostanoids, such as PGE2, and PGF2 α. Here we used PGT in the plasma membrane as a model system to test the hypothesis that PGT also transports PGH2. Using wild type and PGT-expressing MDCK cells, we show that PGH2 uptake is mediated both by simple diffusion and by PGT. The PGH2 influx permeability coefficient for diffusion is (5.66 ± 0.63) × 10−6 cm/s. The kinetic parameters of PGH2 transport by PGT are Km = 376 ± 34 nM and Vmax = 210.2 ± 11.4 fmoles/mg protein/s. PGH2 transport by PGT can be inhibited by excess PGE2 or by a PGT inhibitor. We conclude that PGT may play a role in transporting PGH2 across cellular membranes.

Keywords: prostaglandin H2, prostaglandin transporter

Introduction

Prostaglandin H2 (PGH2) is the common precursor of all other PGs (PGE2, PGI2, PGD2 and PGF2 ) and thromboxane A2 (TxA2). It is converted to these PGs by the specific terminal synthases in the cytoplasm (1-6). Besides serving as a common precursor, extracellular PGH2 can directly trigger signals including Ca2+ release, serotonin release, vasoconstriction, and platelet aggregation (7-10). The signals induced by extracellular PGH2 can therefore oppose the signals resulting from intracellular PGH2, such as formation of PGI2, the most potent endogenous inhibitor of platelet aggregation (11, 12). Thus the net result of PGH2 depends on its localization of PGH2. Of interest, Kent et al. (9) reported that endothelial cells exposed to PGH2 produced PGI2, suggesting that PGH2 might be taken up into endothelial cells and converted to PGI2 by PGI2 synthase. This raises the question of how PGH2 translocation occurs.

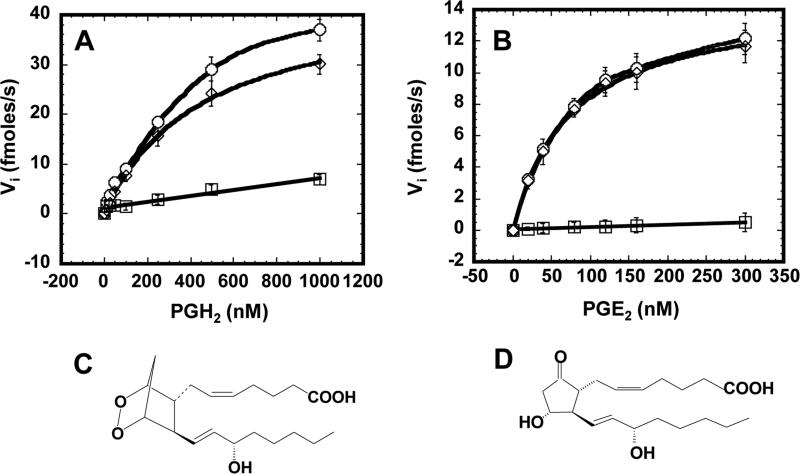

The prostaglandin transporter (PGT) has been shown to transport several prostaglandins, including PGE2 (13, 14). PGT mediates the active uptake of PGE2 into the cell against a concentration gradient (15). Based on the structural similarity between PGH2 and PGE2, as shown in Fig. 2C and D, we hypothesized that PGT might also transport PGH2. Using MDCK cells stably expressing PGT, as previously reported (16), we conducted a detailed investigation of the kinetics of PGH2 transport by PGT. The competition of transport by PGT between PGH2 and PGE2, and the inhibition of PGH2 transport by our newly identified PGT inhibitor, TGBz T34 (15), confirmed that PGH2 is, indeed, a substrate of PGT.

Fig. 2.

Plots of initial velocity of PGH2 (A) or PGE2 (B) uptake by PGT-expressing MDCK cells in the presence (squares) or absence (circles) of 25 μM TGBz T34 as a function of PGH2 (A) or PGE2 (B) concentration. Circles represent the total uptake and squares represent diffusional influx. The diamonds, which represent [total - diffusional] could be fit by the Michaelis-Menton equation (Vi = Vmax [S] / ([S] + Km)). These are representative plots of three individual sets of experiments. In each set of experiment, the error bars are S.D. values of triplicates. The kinetic parameters were generated in each of 3 sets of experiments and presented as mean values ± S.D. in Table 1. C and D, chemical structures of PGE2 and PGH2, respectively

Materials and methods

MDCK cells were stably transfected with the GFP-tagged PGT in our laboratory (16). Tritium labeled PGE2 ([3H)PGE2) and PGH2 ([3H)PGH2) were purchased from PerkinElmer and CaymanChem, respectively. Unlabeled PGE2 was obtained from CaymanChem.

Time Course of PGH2 or PGE2 Transport

MDCK cells were seeded at 15-20% confluence on 24-well plates. The day on which the cells were seeded was considered day one. PGE2 uptake experiments were conducted on day 4. All of the PGH2 or PGE2 uptake experiments were conducted at room temperature. On day 4, cells were washed twice with Waymouth buffer (135 mM NaCl, 13 mM H-Hepes, 13 mM Na-Hepes, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mM MgSO4, 5 mM KCl, and 28 mM D-glucose). Then 200 μL of Waymouth buffer containing 1 μM [3H]PGH2 or 1 nM [3H]PGE2 were added to each well. At the designated time, the uptake of [3H]PGH2 or [3H]PGE2 was stopped by aspiration of uptake buffer, followed immediately by two washes with 500 μL of chilled Waymouth buffer. Cells were then lysed with 100 μL lysis buffer containing 0.25% SDS and 0.05 N NaOH. 1.5 mL of scintillation solution was added to each well, and intracellular [3H]PGH2 or [3H]PGE2 was counted by MicroBeta scintillation Counter.

To obtain the time course of PGE2 transport in the presence of PGH2 or TGBz T34, MDCK cells were incubated in Waymouth buffer containing 1 nM [3H]PGE2 at room temperature for 9 minutes to reach the maximum intracellular level. Thereafter, either PGH2 or TGBz T34 was added to the uptake buffer at a final concentration of 2.5 μM or 25 μM. At the designated time, the uptake of [3H]PGE2 was stopped and uptake was assessed as described above. For the time course of PGH2 uptake in the presence of TGBz T34, MDCK cells were incubated in Waymouth buffer containing 1 μM [3H]PGH2 at room temperature for 120 minutes to reach the maximum intracellular level. At 120 minutes, TGBz T34 was added to the uptake buffer at a final concentration of 25 μM. Then the transport was stopped at varied time points and uptake was quantified as above.

Measurements of Kinetic Parameters of PGE2 and PGH2

We repeated the time courses of PGE2 or PGH2 uptake in the presence or absence of 25 μM TGBz T34 at various initial extracellular concentrations of PGE2 (0, 20, 40, 80, 120, 160, and 300 nM) or PGH2 (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500, and 1000 nM). In the case of PGE2, at low concentrations, the extracellular concentrations were taken as 3H labeled PGE2, which has a specific activity of 500 μCi/mol. At high concentrations of PGE2, we made a mixture of 3H labeled and unlabeled PGE2 to a final specific activity of 25 μCi/mol.

The initial velocities at various extracellular concentrations of PGE2 or PGH2 were determined from the PGE2 uptake in the first 2 minutes or the PGH2 uptake in the first 3 minutes, in the presence or absence of TGBz T34; these were linear over the early time course of PGE2 or PGH2 uptake. The permeability coefficient of PGH2 or PGE2 influx (Pin) was obtained by linear regression fit of the initial rate in the presence of TGBz T34 versus extracellular PGE2 or PGH2 concentration.

We subtracted the initial velocities in the presence of TGBz T34 from those in the absence of TGBz T34. These resulted initial velocities were used to obtain Km and Vmax values by nonlinear regression fit of the initial rate versus extracellular PGE2 or PGH2 concentration to the Michaelis-Menten equation (Vi = Vmax [S] / ([S] + Km)).

Results

Time Course of PGH2 Uptake

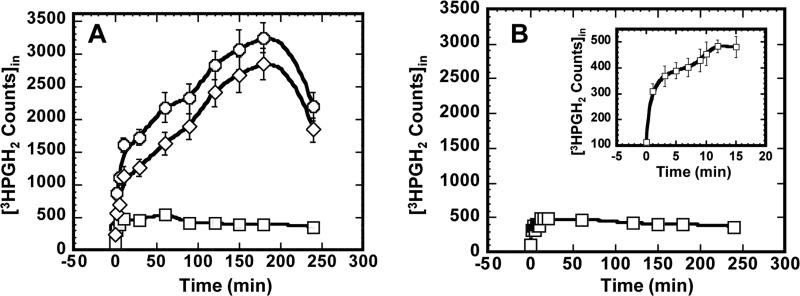

The time course of PGH2 uptake by MDCK cells expressing PGT is shown in Fig. 1A. The circles represent the total PGH2 uptake when the cells were incubated with 1 μM [3H]PGH2. Squares indicate experiments in which cells were incubated with 1 μM [3H]PGH2 in the presence of 25 μM TGBz T34, our newly identified PGT inhibitor (15). The line with diamonds represents PGH2 total uptake minus PGH2 influx when the PGT inhibitor was applied, which is equivalent to PGT-mediated uptake. The “overshoot” is characteristic of PGT (17).

Fig. 1.

A, time course of PGH2 uptake by PGT-expressing MDCK cells in the presence (squares) and absence (circles) of 25 μM TGBz T34. The diamond line is formed by subtracting intracellular PGH2 in the absence of TGBz T34 (circles) by intracellular PGH2 in the presence of TGBz T34 (squares). B, time course of PGH2 uptake by wild type MDCK cells. In both A and B, the values are presented as mean ± S.D. of three individual replicates.

Fig. 1B shows PGH2 uptake by wild-type MDCK cells. The inset of Fig. 1B shows the time course of PGH2 uptake by wild-type MDCK cells for the first 15 minutes. It is evident that PGH2 influx in PGT-expressing cells plus the inhibitor TGBZ T34 (squares in Fig. 1A) is almost identical to the data of Fig. 1B; each of these represents PGH2 influx by simple diffusion. Since the pattern of total PGH2 uptake was similar to that of PGT-mediated uptake, we conclude that PGT mediates the majority of PGH2 uptake.

Kinetics of PGH2 Uptake in Comparison with PGE2 Uptake

To obtain detailed kinetic parameters of PGH2 influx, we measured initial rates of PGH2 uptake at various extracellular PGH2 concentrations in the presence and absence of TGBz T34. In the presence of PGT inhibitor, the plot of the initial rates of PGH2 uptake versus concentration could be fitted with a straight line (squares in Fig. 2A), indicating that this part of influx was caused by simple diffusion. We calculated the permeability coefficient of PGH2 influx (Pin) by diffusion by dividing the slope of this linear line by the total cell surface. Pin for PGH2 was (5.66 ± 0.63) × 10−6 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of PGH2 and PGE2 influx by both PGT and diffusion.

| Kinetic Parameters | PGH2 | PGE2 |

|---|---|---|

| Km (nM) | 376 ± 34 | 91.0 ± 8.2 |

| Vmax (fmoles/mg protein/s) | 210.2 ± 11.4 | 78.9 ± 6.9 |

| Influx permeability coefficient (Pin) (cm/s) | (5.66 ± 0.63) × 10−6 | (1.06 ± 0.13) × 10−6 |

All kinetic parameters are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

In the absence of TGBZ T34, the plot with circles depicts the total PGH2 uptake (Fig. 2A). The PGT mediated rates (diamonds) from Fig. 2A were obtained by subtracting the influx by diffusion (squares) from the total influx (circles). When plotted against PGH2 concentration, they could be fitted by the Michaelis-Menton equation (Fig. 2A). The binding constant of PGH2 to PGT, Km, and the maximum velocity, Vmax, are listed in Table 1. PGT-mediated transport constituted 80% of PGH2 influx; the remainder was mediated by diffusion.

Using the same method, we conducted a similar investigation of the kinetics of PGE2 uptake. As shown in Fig. 2B, circles depict the total PGE2 uptake in the absence of TGBz T34, and squares depict the PGE2 influx in the presence of TGBz T34. The plot of the latter is linear and shows the component of PGE2 influx caused by diffusion. Pin for PGE2, was (1.06 ± 0.13) × 10−6 cm/s (Table 1). Using the same methods as for analyzing PGH2 kinetics, we generated the PGT-mediated uptake component (diamonds), which could be fitted by the Michaelis-Menton equation. The binding constant of PGE2 to PGT, Km, and the maximum velocity, Vmax, are listed in Table 1. As opposed to the case with PGH2, PGT-mediated PGE2 transport was almost identical to total PGE2 uptake, suggesting that PGE2 influx is mainly mediated by PGT. Comparison of the kinetic parameters of PGE2 to PGH2 uptake shows that Pin for PGH2 was 5-fold that for PGE2; Km of PGH2 was 4.1-fold that of PGE2; and Vmax of PGH2 was 2.7-fold that of PGE2.

To address the possibility that 3H-PGH2 was metabolized to 3H-PGE2 and that the measured tracer influx therefore represented 3H-PGE2, and not 3H-PGH2, we added 0, 0.5, or 1.0 μM unlabeled PGH2 to the medium overlaying WT MDCK cells at 37°C, waited 3 minutes, and determined the resulting PGE2 concentrations by enzyme-linked immunoassay. The resulting medium PGE2 concentrations were 0.159 ± 0.014, 0.166 ± 0.014, and 0.156 ± 0.017 nM (n = 3), respectively. These trivial levels of PGE2 are well below the affinity of PGT (Table 1), indicating that conversion of PGH2 to PGE2 cannot account for our uptake results.

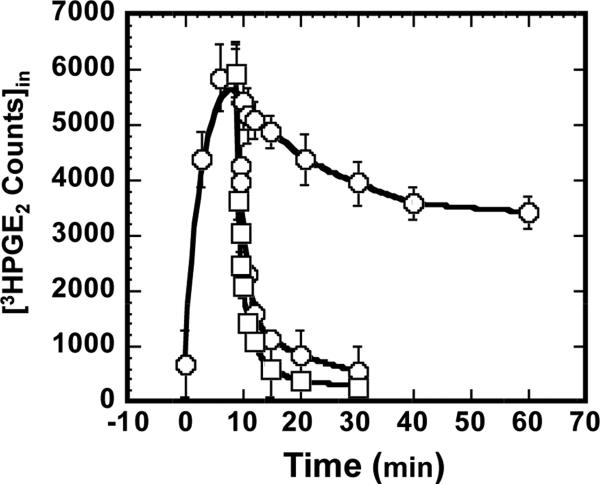

PGH2 serves as a PGT anion exchange substrate

In the absence of an extracellular substrate for PGT, PGE2 efflux occurs exclusively by diffusion (15, 17). However, when a PGT substrate is present in the extracellular medium, PGE2 efflux is accelerated via PGT acting as an obligate anion exchanger (17). In the following experiments, we examined whether unlabeled extracellular PGH2, like unlabeled extracellular PGE2, can serve as a “trans” exchange partner to drive tracer PGE2 efflux.

As shown in Fig. 3 (circles), under control conditions the cells could be rapidly loaded with 3H-PGE2 such that intracellular 3H-PGE2 reached a peak at 9 min and leveled off thereafter. This biphasic pattern results from a “pump-leak” system in which PGT-mediated uptake (“pump”) initially exceeds the diffusion-mediated efflux (“leak”) rate (18). As expected from our prior work (15), application of 25 μM TGBz T34 at 9 minutes abruptly stopped further PGT-mediated 3H-PGE2 uptake. The subsequent rate of 3HPGE2 efflux represents the background diffusional leak (dots in Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Time Course of PGE2 uptake by PGT-expressing MDCK cells in the absence (circles) and presence of 2.5 μM PGH2 (squares) or 25 μM TGBZ T34 (closed circles). PGE2 uptake as a function of time was first established by allowing uptake to various time points, washing, and counting intracellular PGE2 (open circles). In separate experiments, either 2.5 μM PGH2 or 25 μM TGBZ T34 was added at 10 minutes when intracellular PGE2 had reached the peak level. Thereafter, PGE2 uptake was stopped at various points by washing and intracellular PGE2 was measured. The values are presented as mean ± S.D. of triplicates.

We repeated the experiment, but this time added 2.5 μM unlabeled extracellular PGH2 during the 3H-PGE2 uptake. Intracellular 3H-PGE2 fell to baseline within 5 minutes and remained at that level for the rest of the time course. Of note, extracellular PGH2 induced a faster efflux of intracellular 3H-PGE2 than TGBz T34, indicating that PGH2 exchanges with 3H-PGE2 on PGT.

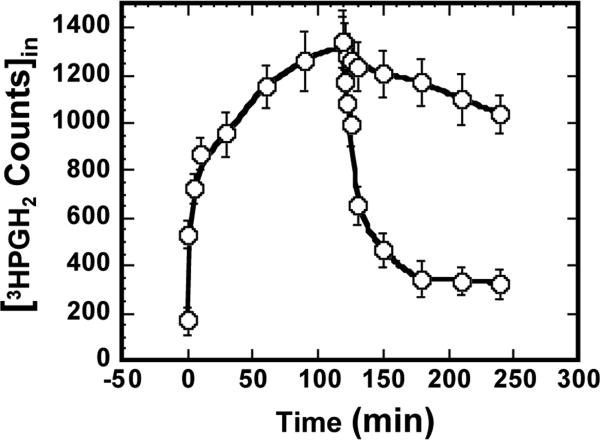

Diffusional efflux of PGH2

Because PGH2 influx can occur to some extent by diffusion (Fig. 2 and Table 1), we examined the degree to which PGH2 also effluxes from cells by diffusion. Toward this end, we loaded cells via PGT for 120 minutes with 3H- PGH2 to a peak level, and then stopped further uptake with 25 μM TGBz T34. As shown in Fig. 4, this block of carrier-mediated PGH2 uptake was followed by a rapid depletion of intracellular 3H-PGH2.This pattern is qualitatively the same as for PGE2 (Fig. 3), and indicates that pre-loaded 3H-PGH2 exits cells by diffusion in the same fashion as pre-loaded PGE2.

Fig. 4.

Diffusional efflux of PGH2. As a baseline, 3H-PGH2 uptake was allowed to proceed to various time points and stopped by washing, and then intracellular 3H-PGH2 was measured (open circles). In separate experiments, 25 μM TGBZ T34 was added at 120 minutes when intracellular PGH2 had reached peak level. Thereafter PGH2 uptake was stopped at various time points by washing and intracellular PGH2 was measured (closed circles). The values are presented as mean ± S.D. of triplicates.

Discussion

PGH2 serves as the common precursor of all other prostaglandins inside cells. It is also rapidly released into the extracellular compartment (Fig. 3) where it can trigger Ca2+ release and platelet aggregation by activating its receptor (7-10, 19). These signals could be reduced as PGH2 was taken back up into cells and converted into other PGs, including PGI2, which inhibits platelet aggregation. It appears that PGH2 plays different roles and may trigger opposing signals, directly or indirectly, from different cellular compartments. Therefore, its translocation is critical for its level in either the intracellular or extracellular compartments. Here, we show that PGH2 efflux is mainly mediated by diffusion and its influx is mediated by both passive diffusion and by a carrier, PGT.

Compared to PGE2, PGH2 is transported by PGT with a lower affinity, but at a higher rate. Using transport across the plasma membrane as a model system, we found that PGH2 has a higher passive permeability than PGE2. The time course of PGH2 uptake across the plasma membrane in our assay system is different from that of PGE2 uptake (Fig. 1A and 3). It took about two hours for PGH2 to reach a peak intracellular level, whereas it took only 10 minutes for PGE2 to do so. This is in spite of the fact that about 20% of PGH2 influx is caused by diffusion, whereas PGE2 influx by diffusion is negligible. Correspondingly, the efflux of PGH2 caused by simple diffusion is much greater than that of PGE2. Therefore, in the “pump-leak” system of PGT-mediated uptake and diffusional efflux, the latter component is much higher for PGH2 than for PGE2.

The differences in transport kinetics between PGH2 and PGE2 are likely due to chemical structure differences. PGH2 has a 7-member ring with two oxygens at the head of the molecule, whereas PGE2 has a five-member ring with a hydroxyl group. Although there are two oxygens in the 7-membrane ring, PGH2 is more hydrophobic than PGE2 because of its lack of a hydroxyl group. This greater hydrophobicity probably accounts for the higher passive diffusion of PGH2 relative to PGE2. The same structural difference probably accounts for the weaker binding of PGH2 to PGT, as compared to PGE2, implying that it is the head of the fatty acid that is interacting with PGT. The -OH group on the ring of PGE2 is important for the interaction, and it is likely to be a proton donor instead of an acceptor, in order for PGE2 to be differentiated from PGH2.

Although PGH2 binds to PGT more weakly than PGE2, the Vmax of PGH2 is higher than that of PGE2, indicating that PGT turns over PGH2 faster than PGE2. The Vmax of PGH2 is 2.7-fold that of PGE2. Given the same amount of PGT, kcat of PGH2 will be 2.7 folds of that of PGE2. The ratio of Km of PGH2 to that of PGE2 is 4.1. The specificity of PGT for a substrate is defined by kcat/Km. Since kcat/Km for PGE2 is 1.5 fold that for PGH2, we conclude that PGT slightly prefers PGE2 over PGH2.

As shown in Fig. 3B and 4, TGBz T34 exerted full inhibition of PGE2 transport, implying that almost 100% of PGE2 influx was mediated by PGT. In the case of PGH2 uptake, TGBz T34 inhibited 80% of PGH2 transport, consistent with the conclusion that about 80% of PGH2 uptake was mediated by PGT and about 20% by diffusion (Fig. 2A and 4).

PGH2 is synthesized by two enzymes cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 or –2, which have been localized to the luminal surfaces of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (20), at specific activities of 25 – 40 nmoles/min/mg protein (21-23). PGH2 is consumed in the cytoplasm by the prostaglandin synthases (PGDS, PGES, PGFS, PGIS), at specific activities of 1 – 4000 nmoles/min/mg protein (1; 2; 4-6; 24-30). The luminal surface of the ER is topologically similar to the exofacial surface of the plasma membrane. Thus, present studies shed light on the kinetics of PGH2 transport across the ER membrane. The specific transport activity of PGT for PGH2 is in the range of 0.012 - 1 nmoles/min/mg protein. If PGH2 translocation from the ER lumen to the cytoplasm is rate-limiting for prostaglandin synthesis, PGT might control the translocation of PGH2 across the ER, and therefore the accessibility of PGH2 to the terminal prostaglandin synthases.

In any event, PGT-mediated uptake of PGH2 may regulate the net signaling that PGH2 triggers. PGT is strongly expressed in endothelial cells and its expression is induced when endothelial cells are under sheer stress (31-33). PGH2-induced platelet aggregation would be counteracted by the anti-coagulation effect of PGI2, formed after PGH2 is transported into endothelial cells by PGT.

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH 2RO-1 DK 49688-12 and NIH P50 DK064236-01

Abbreviations

- PG

Prostaglandin

- PGT

prostaglandin transporter

- PGH2

prostaglandin H2

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- AA

arachidonic acid

- TxA2

thromboxane A2

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pinzar E, Miyano M, Kanaoka Y, Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Structural basis of hematopoietic prostaglandin D synthase activity elucidated by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:31239–31244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanioka T, Nakatani Y, Semmyo N, Murakami M, Kudo I. Molecular identification of cytosolic prostaglandin E2 synthase that is functionally coupled with cyclooxygenase-1 in immediate prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis. J, Biol, Chem. 2000;275:32775–32782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murakami M, Naraba H, Tanioka T, Semmyo N, Nakatani Y, Kojima F, Ikeda T, Fueki M, Ueno A, Oh-ishi S, Kudo I. Regulation of prostaglandin E2 biosynthesis by inducible membrane-associated prostaglandin E2 synthase that acts in concert with cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32783–32792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L-Y, Watanabe K, Hayaishi O. Purification and characterization of prostaglandin F synthase from bovine liver. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 296. 1992:17–26. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe K, Yoshida Y, Shimizu T, Hayaishi O. Enzymatic formation of prostaglandin F2 alpha from prostaglandin H2 and D2. Purification and properties of prostaglandin F synthetase from bovine lung. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:7035–7041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liou J-Y, Shyue S-K, Tsai M-J, Chung C-L, Chu K-Y, Wu KK. Colocalization of prostacyclin synthase with prostaglandin H synthase-1 (PGHS-1) but not phorbol ester-induced PGHS-2 in cultured endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:15314–15320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morinelli TA, Niewiarowski S, Daniel JL, Smith JB. Receptor-mediated effects of a PGH2 analogue (U 46619) on human platelets. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;253:H1035–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayeux PR, Morton HE, Gillard J, Lord A, Morinelli TA, Boehm A, Mais DE, Halushka PV. The affinities of prostaglandin H2 and thromboxane A2 for their receptor are similar in washed human platelets. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;157:733. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80311-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent KC, Collins LJ, Schwerin FT, Raychowdhury MK, Ware JA. Identification of functional PGH2/TxA2 receptors on human endothelial cells. Circ. Res. 1993;72:958–65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.5.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vezza R, Mezzasoma AM, Venditti G, Gresele P. Prostaglandin endoperoxides and thromboxane A2 activate the same receptor isoforms in human platelets. Thromb. Haemost. 2002;87:114–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moncada S, Vane JR. Pharmacology and endogenous roles of prostaglandin endoperoxides, thromboxane A2, and prostacyclin. Pharmacol. Rev. 1978;30:293–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Born GVR. Aggregation of blood platelets by adenosine diphosphate and its reversal. Nature. 1962;194:927–929. doi: 10.1038/194927b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanai N, Lu R, Satriano J, Bao Y, Wolkoff AW, Schuster VL. Identification and characterization of a prostaglandin transporter. Science. 1995;268:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.7754369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuster VL. Molecular mechanisms of prostaglandin transport. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1998;60:221–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi Y, Khersonsky SM, Chang Y-T, Schuster VL. Identification of a new class of prostaglandin transporter inhibitors and characterization of their biological effects on prostaglandin E2 transport. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;316:1346–1350. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nomura T, Lu R, Pucci ML, Schuster VL. The two-step model of prostaglandin signal termination: in vitro reconstitution with the prostaglandin transporter and prostaglandin 15 dehydrogenase. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:973–978. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.4.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan BS, Satriano JA, Pucci ML, Schuster VL. Mechanism of prostaglandin E2 transport across the plasma membrane of HeLa cells and Xenopus oocytes expressing the prostaglandin transporter “PGT”. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:6689–6697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan BS, Endo S, Kanai N, Schuster VL. Identification of lactate as a driving force for prostanoid transport by prostaglandin transporter PGT. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2002;282:F1097–F1102. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00151.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halushka PV, Mais DE, Mayeux PR, Morinelli TA. Thromboxane, prostaglandin and leukotriene receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1989;29:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.29.040189.001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spencer AG, Woods JW, Arakawa T, Singer II, Smith WL. Subcellular localization of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2 by immunoelectron microscopy. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9886–9893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith WL, Garavito RM, DeWitt DL. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases (cyclooxygenases)-1 and -2. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:33157–33160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laneuville O, Breuer DK, Dewitt DL, Hla T, Funk CD, Smith WL. Differential inhibition of human prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases- 1 and -2 by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:927–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnett J, Chow J, Ives D, Chiou M, Mackenzie R, Osen E, Nguyen B, Tsing S, Bach C, Freire J, et al. Purification, characterization and selective inhibition of human prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 and 2 expressed in the baculovirus system. BBA. 1994;1994;1209:130–139. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)90148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urade Y, Fujimoto N, Hayaishi O. Purification and characterization of rat brain prostaglandin D synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:12410–12415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urade Y, Fujimoto N, Ujihara M, Hayaishi O. Biochemical and immunological characterization of rat spleen prostaglandin D synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3820–3825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakobsson P-J, Thorén S, Morgenstern R, Samuelsson B. Identification of human prostaglandin E synthase: a microsomal, glutathione-dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. PNAS. 1999;96:7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe K, Kurihara K, Suzuki T. Purification and characterization of membrane-bound prostaglandin E synthase from bovine heart. BBA. 1999;1439:406–414. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanikawa N, Ohmiya Y, Ohkubo H, Hashimoto K, Kangawa K, Kojima M, Ito S, Watanabe K. Identification and characterization of a novel type of membrane-associated prostaglandin E synthase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;291:884–889. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki T, Fujii Y, Miyano M, Chen L-Y, Takahashi T, Watanabe K. cDNA cloning, expression, and mutagenesis study of liver-type prostaglandin F synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:241–248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hara S, Miyata A, Yokoyama C, Inoue H, rugger RB, Lottspeich F, Ullrich V, Tanabe T. Isolation and molecular cloning of prostacyclin synthase from bovine endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19897–19903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bao Y, Pucci ML, Chan BS, Lu R, Ito S, Schuster VL. Prostaglandin transporter PGT is expressed in cell types that synthesize and release prostanoids. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F1103–10. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00152.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pucci ML, Chakkalakkal B, Liclican EL, Leedom AJ, Schuster VL, Abraham NG. Augmented heme oxygenase-1 induces prostaglandin uptake via the prostaglandin transporter in micro-vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;323:1299–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ulrich D, Ulrich F, Silny J, Unglaub F, Pallua N. Handchir. Mikrochir. Plast Chir. Vol. 38. German: 2006. [Chiparray-based identification of gene expression in HUVECs treated with low frequency electric fields] pp. 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]