Abstract

Since the cloning of the D4 receptor in the 1990s, interest has been building in the role of this receptor in drug addiction, given the importance of dopamine in addiction. Like the D3 receptor, the D4 receptor has limited distribution within the brain suggesting it may have a unique role in drug abuse. However, compared to the D3 receptor, few studies have evaluated the importance of the D4 receptor. This may be due, in part, to the relative lack of compounds selective for the D4 receptor; the early studies were mainly conducted in mice lacking the D4 receptor. In this review, we summarize the literature on the structure and localization of the D4 receptor before reviewing the data from D4 knockout mice that used behavioral models relevant to the understanding of stimulant use. Next, we present evidence from more recent pharmacological studies using selective D4 agonists and antagonists and animal models of drug seeking and taking. The data summarized here suggest a role for D4 receptors in relapse to stimulant use. Therefore, treatments based on antagonism of the D4 receptor may be useful treatments for relapse to nicotine, cocaine and amphetamine use.

Keywords: amphetamine, cocaine, nicotine, smoking, dopamine, D4

Introduction

Dopamine (DA) is an important neurotransmitter in the brain. For more than 25 years, it has been suggested that DA systems in the brain are involved in critical functions such as the primary motivation for natural stimuli such as food, water and sex (Koob, 1992; Wise & Bozarth, 1987). DA primarily exerts its influence by interacting with, and activating, a family of G protein-coupled DA receptors. Between 1988 and 1991, five genes were identified that code for multiple DA receptor subtypes. The DA D2 receptor gene (DRD2) was the first to be cloned (Bunzow et al., 1988; Giros et al., 1989; D.K. Grandy et al., 1989), followed by the DA D1 receptor gene (DRD1) (Dearry et al., 1990; Monsma, Mahan, McVittie, Gerfen, & Sibley, 1991; Sunahara et al., 1990; Zhou et al., 1990), the DA D3 (DRD3) gene (Sokoloff, Giros, Martres, Bouthenet, & Schwartz, 1990), the DA D4 (DRD4) gene (H. H. Van Tol et al., 1991) and finally the DA D5 (DRD5) gene (D. K. Grandy et al., 1991; Sunahara et al., 1991). Not only did it represent a new member of a growing family of unanticipated DA receptors, the high affinity of the antipsychotic clozapine for the DRD4 was intriguing from the standpoint of understanding this important drug's mechanism of action. Clozapine, being an antipsychotic, led to a flurry of interest in developing DRD4 agents for the treatment of schizophrenia. However, it is the highly polymorphic nature of DRD4, the large number of receptor protein variants predicted - each potentially with its own unique pharmacological and second messenger/signaling profiles (Seeman & Van Tol, 1994) – that put it among the most favorite neuropsychiatric candidate genes; a position strengthened by the repeated finding of associations between particular DRD4 VNTRs and a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivcity disorder (reviewed in Kuntsi, McLoughlin, & Asherson, 2006)

The focus of this review will be on the putative role of the DRD4 in stimulant abuse, with a focus on the aspects of this receptor that make it a suitable target for treatment approaches for addiction to stimulants, in particular cocaine, amphetamine and nicotine. The stimulants have in common the fact that they all produce behavioral arousal, with the ability to improve cognition, a property that may confer action on the DRD4, as discussed below. The properties of the DRD4 that make it unique will be summarized, followed by a description of the localization of the DRD4. Studies linking the DRD4 to addictions, in particular smoking, will be reviewed. Finally, the studies with knock out mice and pre-clinical pharmacological studies will be reviewed with an aim to determining the role of the DRD4 in stimulant abuse.

The DRD4

Interest in DRD4 was heightened with the 1992 report (H. H. M. Van Tol et al., 1992) of considerable variation in the human gene, DRD4, and subsequent studies documenting its being among the most highly polymorphic genes in the human genome (Chang, Kidd, Livak, Pakstis, & Kidd, 1996; Lichter et al., 1993). Arguably the single most compelling feature of DRD4 that distinguishes it from almost every other gene in the human genome is its unusual polymorphism in exon 3. This polymorphism consists of an imperfect 48-bp open reading frame that is tandemly repeated 2 to 10 times per allele (Lichter et al., 1993; H. H. M. Van Tol et al., 1992). The most prevalent DRD4 variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) alleles are those consisting of 4-, 7- and 2-repeat alleles, with global mean allele frequencies of 64.3%, 20.6% and 8.2% respectively (Chang et al., 1996). Alleles with less than 7 repeats are generally referred to as “short alleles” (S) while those having more than 7 repeats are referred to as “long alleles” (L). When these polymorphisms are translated the resulting receptor protein domains responsible for G protein-coupling are predicted to differ by as much as 128 amino acids. Naturally this observation resulted in several early studies designed to understand what functional consequences, if any, are associated with each VNTR – a question still to be definitively answered. It should also be noted there is good evidence to support the interpretation that this intracellular domain of the receptor protein not only interacts with G proteins but also binds nuclear factors with potential consequences for gene expression (Schoots & Van Tol, 2003).

Of course two important aspects of deorphanizing a putative G protein-coupled receptor, which the DRD4 was initially, are characterizing its pharmacological profile and defining its second messenger coupling. Although initially the in vitro heterologous expression of DRD4 was difficult, enough protein was made so that its pharmacological profile and Gi coupling could be demonstrated. However, the tendency for heterologous D4 receptor expression to be low hampered in vitro efforts to broaden our understanding of the cellular processes influenced by activated D4 receptors. Once this impediment was overcome it was reported that activation of the DRD4 receptor not only inhibits cAMP production but also opens the kir3 potassium channel, activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1 and 2), and decreases functional GABAA receptor levels (reviewed by Rondou, Haegeman, & Van Craenenbroeck, 2010); responses that may involve receptor oligomerization (Van Craenenbroeck et al., 2011). What remains considerably more elusive is convincingly demonstrating the contribution(s) that DRD4-mediated signaling makes to human health. Over the years several approaches have been taken to this end with one of the most promising being the anatomical mapping of the receptor's mRNA and protein distribution in healthy and pathological human tissues with an emphasis on the brain because of its affinity for the atypical antipsychotic clozapine.

DRD4 Distribution

DRD4 mRNA is found in various brain regions at low density compared with DRD1 or DRD2. It is most abundant in retina (Cohen, Todd, Harmon, & O' Malley, 1992), cerebral cortex, amygdala, hypothalamus and pituitary, but sparsely in the basal ganglia, as assessed by RT-PCR and Northern blot (Valerio et al., 1994), in situ hybridization (Meador-Woodruff et al., 1994; Meador-Woodruff et al., 1997; O'Malley, Harmon, Tang, & Todd, 1992) and immunohistochemistry (Mrzljak et al., 1996). These studies also found DRD4 in both pyramidal and non-pyramidal cells of the cerebral cortex, particularly layer V, and in the hippocampus. Localization of DRD4 to mainly the cerebral cortex, amgydala and hippocampus has functional implications for the role of DRD4. The anygdala and hippocampus are areas that have been implicated in learning and memory (Ito, Robbins, McNaughton, & Everitt, 2006), and in particular the amygdala is thought to be important in the learning of associations with emotional stimuli (Schultz, 2006). In this regard, the L alleles have been associated with attention for emotional stimuli (Wells, Beevers, Knopik, & McGeary, 2013) and DRD4 agonists have been shown to improve performance in cognitive tasks that are memory dependent (Bernaerts & Tirelli, 2003; Powell, Paulus, Hartman, Godel, & Geyer, 2003; Woolley et al., 2008). These are important considerations for the study of addiction, as ‘craving’ and drug-seeking can be powerfully elicited by environmental stimuli that have been previously paired with drug use, and thus the DRD4 may be important in this regard.

Beyond Imaging – Genetic Association Studies

The anatomical mapping approach has resulted in important fundamental knowledge, however, considerable advances were obtained from genetic association studies, in particular the initial findings that a subset of DRD4 VNTRs were found associated with personality traits including excessive impulsivity, novelty seeking and risk taking behavior (Benjamin et al., 1996; Ebstein et al., 1996; Frank & Fossella, 2011; Malhotra et al., 1996; Ptacek, Kuzelova, & Stefano, 2011). Given that associations were found between DRD4 VNTRs, impulsivity, novelty seeking and risk taking behavior it comes as no surprise there has been considerable interest in the receptor's potential role in drug taking behavior and as a target for novel abstinence medications. However, both positive and negative associations have been reported between various DRD4 alleles and methamphetamine (METH) abuse. METH abusers had a significantly higher prevalence of the seven-repeat alleles than controls, while there were no significant differences in the DRD2 or DRD3 alleles between the METH abusers and controls (Chen et al., 2004), highlighting the importance specifically of the DRD4 receptor for drug abuse. In another study, however, no differences were found for DRD4 gene exon III polymorphisms (Tsai et al., 2002). In an attrempt to reconcile these disparate findings an intriguing new approach to assessing the contribution of the VNTR to drug-taking behaviors has been proposed (McGeary, 2009).

Although the studies of the relationship between alleles and DRD4 are somewhat compelling, the possible involvement of DRD4 variants in nicotine use provides the most comprehensive information. One study reports an association between DRD4 genotype and smoking in African-Americans but not Caucasians (Shields et al., 1998). Comparison of male carriers of an L-allele to those with the S-allele revealed that those with the L-allele started smoking earlier, had a higher rate of lifetime smoking, and smoked more cigarettes per day (Laucht, Becker, El-Faddagh, Hohm, & Schmidt, 2005). Interestingly, significantly less binding potential was detected using PET imaging of DRD2 receptors in carriers of DRD4 alleles with more than 7 repeats (Brody et al., 2006); decreased binding potential of (11C)-raclopride is an indirect measure of DA release and implies that DA release was increased. By categorizing participants as either DRD4 S or DRD4 L, other studies have found differences between those carrying the L and S alleles on smoking cue reactivity (Hutchison, LaChance, Niaura, Bryan, & Smolen, 2002; McClernon, Hutchison, Rose, & Kozink, 2007; Munafo & Johnstone, 2008) and some suggest the L-alleles are a risk factor for heavy smoking and may influence smoking cessation outcome (David et al., 2007; Ton et al., 2007; Vandenbergh et al., 2007); however, the authors indicate their findings are preliminary and need to be replicated in a controlled study with a larger sample size.

Even though the findings of genetic association studies are provocative and in some cases compelling, additional complementary approaches – including the development and use of animal models – will be required to provide a molecular explanation that connects a particular personality trait or mental health condition with one or more DRD4 VNTRs. Next, we will provide a short summary of the information that has been collected using knock-out and pharmacological approaches to determine the role(s) its variants play in psychostimulant drug abuse (i.e. cocaine, methamphetamine and nicotine).

DRD4 and Psychostimulant Addiction

Although genetic association studies have provided compelling results, advances in the understanding of the role of DRD4 came about from studies with genetically modified mice (Rubinstein et al., 1997; Waddington et al., 2005), and, more recently, pharmacological studies with selective DRD4 agents. At the time that the use of genetically modified mice was first proposed (1995-96), there were no selective antagonists available, and early studies into the role of the DRD4 were provided by findings with these mutants. In addition, the KO background would provide the perfect means of evaluating in vivo the selectivity of any emerging DRD4-selective compounds as well as any immunological reagents. In genetically modified mice, one strategy is to “knock-out” (KO) all expression of a functional DRD4 by completely eliminating the receptor protein. The strategy for targeting the drd4 gene was accomplished relatively quickly and has been described in detailed (Rubinstein et al., 1997).

Early findings with knockout mice have confirmed the pharmacological and electrophysiological consequences of altering the number of functional DRD4 alleles, but not all of the behavioural findings have. For example, whereas the findings of Ralph et al. (1999) indicated a role for the DRD4 gene product in mediating amphetamine's disruption of prepulse inhibition of the startle response (Ralph et al., 1999), a finding that is is widely accepted, the findings reported by Dulawa et al. (1999) claiming a role for DRD4 in novelty seeking behavior (Dulawa, Grandy, Low, Paulus, & Geyer, 1999) has been challenged by the results of at least two independent studies (Keck, Suchland, Jimenez, & Grandy, 2013; Powell et al., 2003). Of relevance to the focus of this review is the observation that mice completely lacking functional DRD4 are dose-dependently hypersensitive to the locomotor stimulating effect of METH (Katz et al., 2003; Rubinstein et al., 1997) and methylphenidate (Keck et al., 2013). Locomotor activity is believed to be related to addictive potential (Wise & Bozarth, 1987), and thus the findings that D4 knockout mice are hypersensitive to locomotion suggests that DRD4 may mediate propensity to addiction. However, it has been found that DRD4 knockout mice show a decreased DA response to an amphetamine challenge (Thomas et al., 2007), a finding that is not in keeping with the locomotor hypersensitivity observed, given that increased locomotion is associated with increased DA release (Kuczenski & Segal, 1989). Thus, the findings with the DRD4 knockout mice are inconclusive and it may be best to look at behavioural measures more directly related to drug addiction and to consider the findings with knockout mice together with the more recent antagonist studies. These findings are provided below and organised by animal model. Each section begins with a description of the animal model to frame the results with knockout mice and antagonists.

Drug Self-Administration

In pre-clinical studies of drug addiction, drug self-administration has become the ‘gold standard’ for studying drugs of abuse. Once acquired, self-administration behavior remains stable over days; animals ‘titrate’ their intake of drug to maintain constant blood levels of the drug (Yokel & Pickens, 1974) and brain levels of DA (Di Ciano et al., 1995; Pettit & Justice, 1991). In one study by Thanos et al. (2010), it was found that mice lacking the DRD4 were similar to controls in responding for cocaine (P. K. Thanos et al., 2010). Consistent with the findings from knockout mice, it has been found that administration of L-745,870 has no effect on self-administration of nicotine (Yan, Pushparaj, Le Strat, et al., 2012). L-745,870 is a DRD4 antagonist with a Ki of 0.43, 960 and 2300 for DRD4, DRD2 and DRD3, respectively. It also has no appreciable binding to DRD1 or DRD5 (Ki >10,000) (Kulagowski et al., 1996). Although this finding may suggest that DRD4 are not involved in drug addiction, it is important to consider these findings within a larger context. That is, it is known that when the dose of drug available is decreased, rats may increase their rate of responding to compensate for the decreased dose received (Pickens & Thompson, 1968). This is a problem with antagonists at the DRD2 (Woolverton, 1986; Yokel & Wise, 1975), but not those that target the DRD3 (Andreoli et al., 2003; Di Ciano, Underwood, Hagan, & Everitt, 2003; Gal & Gyertyan, 2003; Le Foll & Goldberg, 2006; Xi et al., 2005), as revealed in studies with rats. This suggests that DA DRD2 antagonists would not be ideal treatments for substance abuse, as they may increase drug intake. Thus, what the findings with the D4 knockout mice reveal is that DRD4 antagonists do not increase drug self-administration, a finding which is promising for the development of D4 antagonists as treatment for drug addiction, provided that D4 antagonists influence other models of drug addiction.

Reinstatement

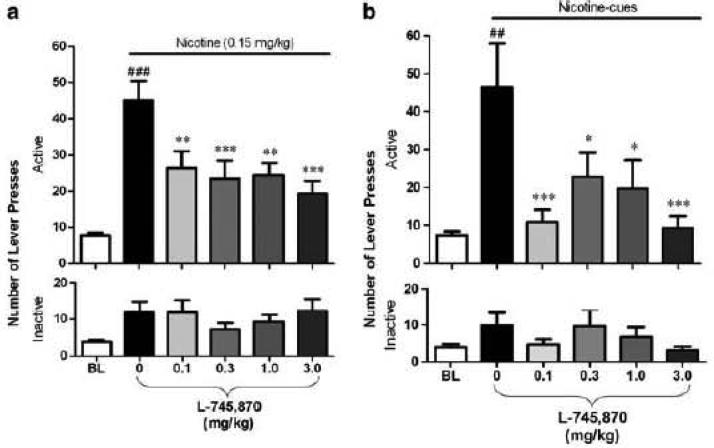

Drug abuse is a chronic relapsing disorder and an understanding of the role of DRD4 in stimulant addiction can be obtained from a focus on the effects of interventions on relapse to drug seeking. The main animal models of relapse are the reinstatement models that have evolved from studies with drugs that modeled the ability of environmental stimuli (de Wit & Stewart, 1981) and drugs (Gerber & Stretch, 1975; Stretch & Gerber, 1973) to induce relapse to drug-seeking. Reinstatement is an animal model with high predictive validity (Epstein & Preston, 2003) that has been studied in rats (Chiamulera, Borgo, Falchetto, Valerio, & Tessari, 1996; Forget, Coen, & Le Foll, 2009; Khaled et al., 2010; Pushparaj et al., 2013; Shaham, Adamson, Grocki, & Corrigall, 1997), mice (Yan, Pushparaj, Gamaleddin, et al., 2012), non human primates (Mascia et al.) and humans (McKee, 2009). In this model, the animal is first trained to self-administer drug and then the response is extinguished by removing the associated drug that was self-administered; responses have no consequences during extinction. Following extinction of the response, a condition, such as stress, cues or drug is introduced that reinstates extinguished responding. It has been shown that a DA D4 antagonist, L-745,870, can block the reinstatement of nicotine-seeking induced by either cues paired with the drug or re-exposure to nicotine itself (Yan, Pushparaj, Le Strat, et al., 2012). As seen in Figure 1, administration of nicotine reinstated responding to above extinguished levels, and several doses of L-745,870 reduced this reinstatement. Similarly, cues previously paired with each self-administered nicotine infusion also reinstated extinguished responding, and L-745,870 also attenuated this. An effect on both types of reinstatement suggests that the effects of D4 antagonists may be related to an effect on relapse per se and not the ability of, for example, cues to maintain behavior or of nicotine to influence behavior. In sum, these findings suggest that DA DRD4 are involved in the relapse to drug-seeking. Although promising, the findings with nicotine should be generalized to other drugs of abuse to reveal the generality of the effect.

Figure 1.

Effect of DRD4 antagonist L-745,870 on the mean + reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior in rats. A) Pretreatment of L-745,870 significantly reduced the number of active (upper) but not inactive (lower) lever presses triggered by nicotine-associated cues (n=13). B) Pretreatment of L-745,870 significantly attenuated the number of active (upper) but not inactive (lower) lever presses induced by priming injection of nicotine (0.15 mg/kg s.c.; n=23). *p<0.05; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs the baseline (BL). Student's paired t-test ##p<0.01; ###p<0.001 vs the vehicle pretreatment. Taken from Yan et al. (2012), with permission.

Together, the findings thus far suggest that DRD4 antagonists would be viable targets for treatments for stimulant abuse as they prolong abstinence while not increasing drug self-administration. This position is highlighted by the further findings that L-745,870 did not affect reinstatement of food seeking induced by either presentation of food or the presentation of food associated cues (Yan, Pushparaj, Le Strat, et al., 2012). Thus, the effects of DA D4 antagonists seem selective to stimulants, and do not generalize to natural rewards, meaning that their use as treatments may not impact on general motivation, a problem with DA antagonists that are used in the clinic. This is encouraging as administration of the DRD4 agonist A-412997 increased locomotor activity (Woolley et al., 2008), implicating DRD4 in general activity levels, but the lack of effect of food is informative in that the role of DRD4 in general activity levels may not play a role in behaviors motivated for drug. This hypothesis warrants further testing by examining whether DRD4 antagonists have similar effects on other types of stimulants, such as cocaine or amphetamine, or whether their effects are only on nicotine.

Drug discrimination

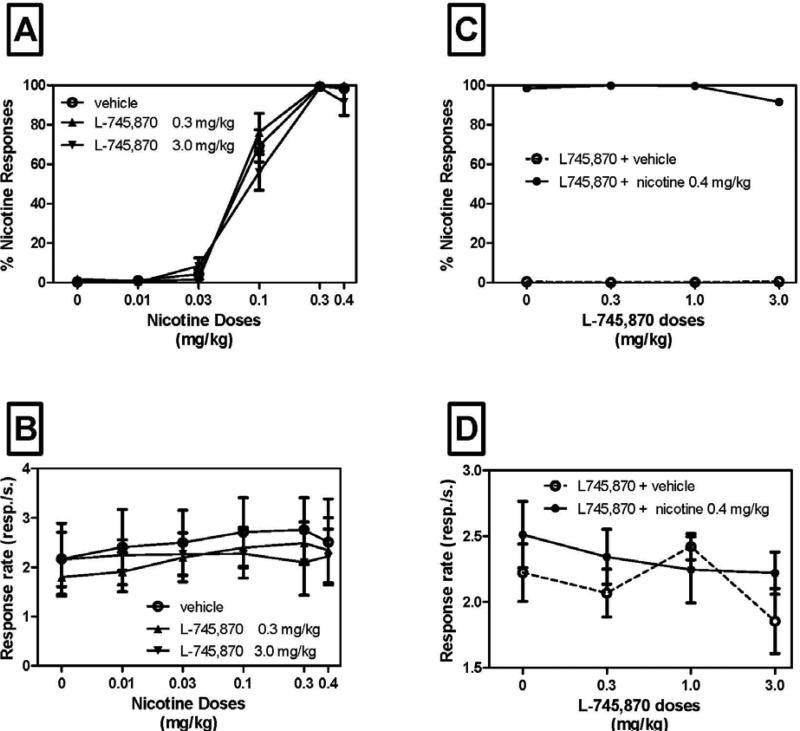

All drugs of abuse have interoceptive properties and in the drug discrimination procedure, the ability of rats to distinguish different interoceptive properties is tested. In the drug discrimination procedure, rats are trained, for example, to respond on a lever located on the left side of a test chamber when given a certain drug of abuse, and to respond on the right-side lever when they are given saline. Over time, animals will learn to make differential responses on the two levers. The effects of drug challenges on drug-appropriate versus saline-appropriate responding can then be determined. As illustrated in Figure 2, the amount of nicotine-appropriate responding increases with dose of a challenge dose of nicotine; nicotine feels ‘more like’ nicotine as the dose is increased. Once discriminative responding has been established, a test compound can then be administered and if the animal responds on the nicotine-appropriate lever, then this suggests that the test compound has similar interoceptive properties to the drug of abuse. Alternatively, a test compound can be administered with the drug of abuse and the effects on discrimination of responding for the drug of abuse as compared to that for saline can be determined. If the test compound decreases drug-appropriate responding then the discriminative properties of the drug of abuse have been disrupted. This is important because the discriminative properties of drugs may maintain responding for drug, and thus compounds that disrupt the discriminative properties of drugs of abuse may serve as potential treatments, especially if the animal has learned to discriminate drug from saline. As can be seen in Figure 2, the D4 antagonist L-745, 870 had no effect on discriminative responding for nicotine. At both doses of L-745,870, the dose-response function for nicotine-appropriate responding after various doses of nicotine was similar to that observed after co administration of nicotine with vehicle (Yan, Pushparaj, Le Strat, et al., 2012). Similarly, L-745,870 also did not affect cocaine-appropriate responding when co-administered with cocaine (Costanza & Terry, 1998); in this study, L-745,870 also did not produce cocaine-appropriate responding when administered on its own. In contrast, blockade of DRD4 did block the discriminative stimulus properties of METH in mice (Yan et al., 2006). In sum, DRD4 does not appear to be involved in discriminative properties of nicotine and cocaine, but may participate to those of METH. Taken together, it appears that D4 antagonists do not have interoceptive properties that are similar to those of stimulants and they disrupt drug-seeking through mechanisms that are not related to the discriminative properties of the drug. Similarly, a D4 agonist, ABT-724 was self-administered in only one of 5 monkeys tested, and at levels lower than that for cocaine (Koffarnus et al., 2012), consistent with the lack of discriminative properties with cocaine.

Figure 2.

A) Dose effect functions for the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in rats trained to discriminate 0.4 mg/kg nicotine from saline. The percentage of responses on the lever associated with nicotine administration is shown as a function of dose (mg/kg) during tests with various doses of nicotine. The DRD4 antagonist L-745,870 administered acutely 30min before the sessions did not modify discriminative-stimulus effects of nicotine (no curve shift). B) L-745,870 also did not significantly affect rates of lever-press responding when administered together with different doses of nicotine or with vehicle. C) Effects of different doses of L-745,870 on discriminative-stimulus effects of the training dose of nicotine when L-745,870 was administered with vehicle. D) Effects of different doses of L-745,870 on rates of lever-press responding when administered together with the training dose of nicotine or with vehicle (n=9-12). Data are expressed as means (± SEM) of the percentage of responses on the nicotine lever.

Consistent with their lack of discriminative properties similar to stimulants, a number of findings suggest that DA DRD4 may not have rewarding properties on their own. For example, as mentioned above, monkeys did not self-administer the D4 agonist ABT-724 (Koffarnus et al., 2012), and thus, DA D4 agonists may not have reinforcing effects on their own. Similarly, administration of A-412997, a D4 agonist, did not induce a conditioned place preference (Woolley et al., 2008). Thus, based on the findings of Woolley et al., (2008), that a D4 agonist did not induce place preference on its own, it is possible to conclude that stimulation of DRD4 is not rewarding on its own.

Conditioned Place Preference

Another frequently used model of drug addiction is the conditioned place preference model (Liu, Le Foll, Wang, & Lu, 2008). Place preference is a well-established animal model of addiction in which two sides of a test chamber are uniquely identifiable to an animal and one side is paired with a rewarding substance while the other with vehicle. At test, the animal is placed in between the two sides and allowed to explore free of drugs. It is has been reported many times, that, after administration of stimulants, the time spent on the drug-paired side is increased relative that paired with vehicle (Carr, Fibiger, & Phillips, 1989). Place preference is believed to be a measure of the rewarding aspects of drugs, especially those maintained by conditioned aspects of stimuli previously paired with drugs. In a report by Thanos et al. (2010), it was found that DRD4 knockout mice were not impaired in conditioned place preference to methylphenidate, amphetamine and cocaine relative to controls (P. Thanos et al., 2009). Thus, DRD4 are not involved in this measure of drug addiction. Further insights may be gained from pharmacological interventions conducted in animal studies.

Sensitization

Sensitization is a model of drug addiction based on observations that a behavioral response to drugs of abuse can increase over time with repeated exposure to the drug. In the most frequently used model of sensitization, locomotor activity counts to a stimulant challenge are obtained at baseline and again after a course of treatment with the drug. When administered intermittently (as opposed to continually) (T.E. Robinson & Becker, 1986), repeated administration of a drug can potentiate the locomotor activating effects of the drug. When administered the D4 antagonist PNU-101387G prior to the pre-treatments with amphetamine, behavioral sensitization to a subsequent amphetamine challenge was blocked (Feldpausch et al., 1998). PNU-101387G has high selectivity for the DRD4 (Ki=3.6) as opposed to other DA receptor subtypes (DRD1 Ki > 8,000; DRD2 Ki = 5,147; DRD3 Ki>2,778) (Merchant et al., 1996). It has been posited that the role of sensitization in addiction is to increase drug wanting over time, thus rendering the user addicted to a drug (T. E. Robinson & Berridge, 1993). Thus, DA DRD4 may be important in the development of sensitization to drugs of abuse and thereby be important in the establishment of an addiction. Again, these findings need to be replicated with other stimulants such as cocaine or nicotine to determine whether the stimulatory role of DRD4 is simply on the effects of amphetamine or whether they mediate some common aspect that underlies the sensitization process.

Conclusions

Since the cloning of the DRD4 in the 1990s, this receptor has received growing attention. Although genetic association studies have been compelling in implicating a role of the DRD4 in stimulant use, the real advances in understanding of this receptor emerged with the advent of knockout mice, and, more recently, selective pharmacological agents. When interpreting the role of DRD4 in stimulant use, the findings from the knockout mice and pharmacological interventions tell a coherent story. From the literature it is clear that DRD4 affect the reinstatement of nicotine-seeking and thus may be potential treatments for relapse, especially since DRD4 antagonists were without non-specific effects on responding for food and DRD4 agonists were not self-administered themselves (therefore they have no addictive potential). This is further supported by findings that DRD4 antagonists blocked the development of sensitization to stimulants. This finding must be taken into context with those that found no effect of D4 knockout or D4 antagonists on a place preference; perhaps DRD4 is not involved in the conditioned rewarding properties of drugs, but may, instead, mediate the relapse or other aspects of seeking. Issues that remain to be resolved are the findings of a blockade of discriminative properties of cocaine but not METH by DRD4 antagonists; further studies will need to determine whether DRD4 is involved in this function. Also, it remains to be determined whether the promising findings on reinstatement will generalize to other stimulant drugs, as the findings so far are only with nicotine. In sum, D4 antagonists may provide a means by which novel treatments for stimulant-seeking may be targeted. The fact that ligands that are available in clinic such as buspirone, are also effective DRD4 antagonists (Bergman et al., 2013) could represent a translational opportunity for future work (Le Foll & Boileau, 2013). Indeed, recent findings implicate DRD4 in gambling, which is an addictive behavior (Cocker, Le Foll, Rogers, & Winstanley, 2013).

Acknowledgment

Some descriptions of the distribution of the dopamine receptors have been reproduced with permission from Behavioral Pharmacology (Le Foll, Gallo, Le Strat, Lu, & Gorwood, 2009).

List of Abbreviations

- DA

dopamine DRD1 dopamine type 1 receptor

- DRD2

dopamine type 2 receptor

- DRD3

dopamine type 3 receptor

- DRD4

dopamine type 4 receptor

- DRD5

dopamine type 5 receptor

- VNTR

variable number of tandem repeats

- S

short alleles

- L

long alleles

- GABA

γ-aminbutyric acid

- ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- METH

Methamphetamine

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Andreoli M, Tessari M, Pilla M, Valerio E, Hagan JJ, Heidbreder CA. Selective antagonism at dopamine D3 receptors prevents nicotine-triggered relapse to nicotine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(7):1272–1280. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin J, Li L, Patterson C, Greenberg BD, Murphy DL, Hamer DH. Population and familial association between the D4 dopamine receptor gene and measures of Novelty Seeking. Nat Genet. 1996;12(1):81–84. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-81. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman J, Roof RA, Furman CA, Conroy JL, Mello NK, Sibley DR, Skolnick P. Modification of cocaine self-administration by buspirone (buspar(R)): potential involvement of D3 and D4 dopamine receptors. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(2):445–458. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000661. [Research Support, N.I.H., Intramural] doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaerts P, Tirelli E. Facilitatory effect of the dopamine D4 receptor agonist PD168,077 on memory consolidation of an inhibitory avoidance learned response in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2003;142(1-2):41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00371-6. doi: S0166432802003716 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody AL, Mandelkern MA, Olmstead RE, Scheibal D, Hahn E, Shiraga S, McCracken JT. Gene variants of brain dopamine pathways and smoking-induced dopamine release in the ventral caudate/nucleus accumbens. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):808–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.808. doi: 63/7/808 [pii] 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunzow JR, Van Tol HHM, Grandy DK, Albert P, Salon J, Christie M, Civelli O. Cloning and expression of a rat D2 receptor cDNA. Nature. 1988;336:783–787. doi: 10.1038/336783a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr GD, Fibiger HC, Phillips AG. Conditioned place preference as a measure of drug reward. In: Liebman JM, Cooper SJ, editors. Neuropharmacological basis of reward. Oxford, New York: 1989. pp. 264–319. [Google Scholar]

- Chang FM, Kidd JR, Livak KJ, Pakstis AJ, Kidd KK. The world-wide distribution of allele frequencies at the human dopamine D4 receptor locus. Hum Genet. 1996;98(1):91–101. doi: 10.1007/s004390050166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CK, Hu X, Lin SK, Sham PC, Loh el W, Li T, Ball DM. Association analysis of dopamine D2-like receptor genes and methamphetamine abuse. Psychiatr Genet. 2004;14(4):223–226. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200412000-00011. doi: 00041444-200412000-00011 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiamulera C, Borgo C, Falchetto S, Valerio E, Tessari M. Nicotine reinstatement of nicotine self-administration after long-term extinction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;127(2):102–107. doi: 10.1007/BF02805981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocker PJ, Le Foll B, Rogers RD, Winstanley CA. A Selective Role for Dopamine D Receptors in Modulating Reward Expectancy in a Rodent Slot Machine Task. Biol Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.026. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AI, Todd RD, Harmon S, O' Malley KL. Photoreceptors of mouse retinas possess D4 receptors coupled to adenylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:12093–12097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanza RM, Terry P. The dopamine D4 receptor antagonist L-745,870: effects in rats discriminating cocaine from saline. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;345(2):129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01603-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SP, Munafo MR, Murphy MF, Proctor M, Walton RT, Johnstone EC. Genetic variation in the dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) gene and smoking cessation: follow-up of a randomised clinical trial of transdermal nicotine patch. Pharmacogenomics J. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500447. doi: 6500447 [pii] 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Stewart J. Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacol. 1981;75:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00432175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearry A, Gringrich JA, Falardeau P, Fremeau RT, Bates MD, Caron MG. Molecular cloning and expression of the gene for a human D1 dopamine receptor. Nature. 1990;347:72–76. doi: 10.1038/347072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Coury A, Depoortere RY, Egilmez Y, Lane JD, Emmett-Oglesby MW, Blaha CD. Comparison of changes in extracellular dopamine concentrations in the nucleus accumbens during intravenous self-administration of cocaine or d-amphetamine. Behav Pharmacol. 1995;6(4):311–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Underwood RJ, Hagan JJ, Everitt BJ. Attenuation of cue-controlled cocaine-seeking by a selective D3 dopamine receptor antagonist SB-277011-A. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(2):329–338. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulawa SC, Grandy DK, Low MJ, Paulus MP, Geyer MA. Dopamine D4 receptor-knock-out mice exhibit reduced exploration of novel stimuli. J Neurosci. 1999;19(21):9550–9556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09550.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebstein RP, Novick O, Umansky R, Priel B, Osher Y, Blaine D, Belmaker RH. Dopamine D4 receptor (D4DR) exon III polymorphism associated with the human personality trait of Novelty Seeking. Nat Genet. 1996;12(1):78–80. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Preston KL. The reinstatement model and relapse prevention: a clinical perspective. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168(1-2):31–41. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1470-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldpausch DL, Needham LM, Stone MP, Althaus JS, Yamamoto BK, Svensson KA, Merchant KM. The role of dopamine D4 receptor in the induction of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine and accompanying biochemical and molecular adaptations. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286(1):497–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget B, Coen KM, Le Foll B. Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase reduces reinstatement of nicotine seeking but not break point for nicotine self-administration--comparison with CB(1) receptor blockade. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;205(4):613–624. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1569-5. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1569-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Fossella JA. Neurogenetics and pharmacology of learning, motivation, and cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(1):133–152. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.96. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review]. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal K, Gyertyan I. Targeting the dopamine D3 receptor cannot influence continuous reinforcement cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2003;61(6):595–601. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber GJ, Stretch R. Drug-induced reinstatement of extinguished self-administration behavior in monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1975;3(6):1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(75)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giros B, Sokoloff P, Martres M-P, Riou J-F, Emorine LJ, Schwartz J-C. Alternative splicing directs the expression of two D2 dopamine receptor isoforms. Nature. 1989;342:923–926. doi: 10.1038/342923a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandy DK, Marchionni MA, Makan H, Stofko RE, Alfano M, Frothingham L, Civelli O. Cloning of the cDNA and gene for a human D2 dopamine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;84:9762–9766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandy DK, Zhang YA, Bouvier C, Zhou QY, Johnson RA, Allen L, Civelli O. Multiple human D5 dopamine receptor genes: a functional receptor and two pseudogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(20):9175–9179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9175. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KE, LaChance H, Niaura R, Bryan A, Smolen A. The DRD4 VNTR polymorphism influences reactivity to smoking cues. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(1):134–143. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R, Robbins TW, McNaughton BL, Everitt BJ. Selective excitotoxic lesions of the hippocampus and basolateral amygdala have dissociable effects on appetitive cue and place conditioning based on path integration in a novel Y-maze procedure. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23(11):3071–3080. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL, Chausmer AL, Elmer GI, Rubinstein M, Low MJ, Grandy DK. Cocaine-induced locomotor activity and cocaine discrimination in dopamine D4 receptor mutant mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170(1):108–114. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1513-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck TM, Suchland KL, Jimenez CC, Grandy DK. Dopamine D4 receptor deficiency in mice alters behavioral responses to anxiogenic stimuli and the psychostimulant methylphenidate. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;103(4):831–841. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.006. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaled MA, Farid Araki K, Li B, Coen KM, Marinelli PW, Varga J, Le Foll B. The selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonist SB 277011-A, but not the partial agonist BP 897, blocks cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking. Int J Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;13(2):181–190. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709991064. doi: S1461145709991064 [pii] 10.1017/S1461145709991064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Collins GT, Rice KC, Chen J, Woods JH, Winger G. Self-administration of agonists selective for dopamine D2, D3, and D4 receptors by rhesus monkeys. Behav Pharmacol. 2012;23(4):331–338. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283564dbb. [Comparative Study Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, N.I.H., Intramural Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283564dbb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Neural mechanisms of drug reinforcement. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;654:171–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal D. Concomitant characterization of behavioral and striatal neurotransmitter response to amphetamine using in vivo microdialysis. J Neurosci. 1989;9(6):2051–2065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-06-02051.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulagowski JJ, Broughton HB, Curtis NR, Mawer IM, Ridgill MP, Baker R, Leeson PD. 3-((4-(4-Chlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl)-methyl)-1H-pyrrolo-2,3-b-pyridine: an antagonist with high affinity and selectivity for the human dopamine D4 receptor. J Med Chem. 1996;39(10):1941–1942. doi: 10.1021/jm9600712. doi: 10.1021/jm9600712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsi J, McLoughlin G, Asherson P. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuromolecular Med. 2006;8(4):461–484. doi: 10.1385/NMM:8:4:461. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review] doi: 10.1385/NMM:8:4:461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laucht M, Becker K, El-Faddagh M, Hohm E, Schmidt MH. Association of the DRD4 exon III polymorphism with smoking in fifteen-year-olds: a mediating role for novelty seeking? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(5):477–484. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000155980.01792.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Boileau I. Repurposing buspirone for drug addiction treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(2):251–253. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000995. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Gallo A, Le Strat Y, Lu L, Gorwood P. Genetics of dopamine receptors and drug addiction: a comprehensive review. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20(1):1–17. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283242f05. [Meta-Analysis Review] doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283242f05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Targeting the Dopamine D3 Receptor for Treatment of Tobacco Dependence. In: George TP, editor. Medication Treatments for Nicotine Dependence. Taylor and Francis; 2006. (Vol. in press) [Google Scholar]

- Lichter JB, Barr CL, Kenney JL, Van Tol HHM, Kidd KK, Livak KJ. A hypervariable segment in the human dopamine D4 (DRD4) gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993;2:767–773. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.6.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Le Foll B, Wang X, Lu L. Conditioned place preference induced by licit drugs: establishment, extinction, and reinstatement. ScientificWorldJournal. 2008;8:1228–1245. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.154. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra AK, Virkkunen M, Rooney W, Eggert M, Linnoila M, Goldman D. The association between the dopamine D4 receptor (D4DR) 16 amino acid repeat polymorphism and novelty seeking. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1(5):388–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascia P, Pistis M, Justinova Z, Panlilio LV, Luchicchi A, Lecca S, Goldberg SR. Blockade of nicotine reward and reinstatement by activation of alpha-type peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Biol Psychiatry. 69(7):633–641. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.009. doi: S0006-3223(10)00716-X [pii] 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClernon FJ, Hutchison KE, Rose JE, Kozink RV. DRD4 VNTR polymorphism is associated with transient fMRI-BOLD responses to smoking cues. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;194(4):433–441. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0860-6. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0860-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeary J. The DRD4 exon 3 VNTR polymorphism and addiction-related phenotypes: a review. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93(3):222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.03.010. [Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S. Review] doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA. Developing human laboratory models of smoking lapse behavior for medication screening. Addict Biol. 2009;14(1):99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00135.x. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review]. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff JH, Grandy DK, Van Tol HHM, Damask SP, Little KY, Civelli O, Watson SJ. Dopamine receptor gene expression in the human medial temporal lobe. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1994;10:239–248. doi: 10.1038/npp.1994.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador-Woodruff JH, Haroutunian V, Powchik P, Davidson M, Davis KL, Watson SJ. Dopamine receptor transcript expression in striatum and prefrontal and occipital cortex. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997;54:1089–1095. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant KM, Gill GS, Harris DW, Huff RM, Eaton MJ, Lookingland K, Tenbrink RE. Pharmacological characterization of U-101387, a dopamine D4 receptor selective antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279(3):1392–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsma FJ, Mahan LC, McVittie LD, Gerfen CR, Sibley DR. Molecular cloning and expression of a D1 dopamine receptor linked to adenylyl cyclase activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1991;87:6723–6727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrzljak L, Bergson C, Pappy M, Huff R, Levenson R, Goldman-Rakic PS. Localization of dopamine D4 receptors in GABAergic neurons of the primate brain. Nature. 1996;381(6579):245–248. doi: 10.1038/381245a0. doi: 10.1038/381245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Johnstone EC. Smoking status moderates the association of the dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) gene VNTR polymorphism with selective processing of smoking-related cues. Addict Biol. 2008;13(3-4):435–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00098.x. doi: ADB098 [pii] 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley KL, Harmon S, Tang L, Todd RD. The rat dopamine D4 receptor sequence, gene structure, and demonstration of expression in the cardiovascular system. The New Biologist. 1992;2:137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit HO, Justice JB., Jr. Effect of dose on cocaine self-administration behavior and dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 1991;539(1):94–102. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90690-w. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens R, Thompson T. Cocaine-reinforced behavior in rats: effects of reinforcement magnitude and fixed-ratio size. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968;161(1):122–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell SB, Paulus MP, Hartman DS, Godel T, Geyer MA. RO-10-5824 is a selective dopamine D4 receptor agonist that increases novel object exploration in C57 mice. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44(4):473–481. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00412-4. [Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek R, Kuzelova H, Stefano GB. Dopamine D4 receptor gene DRD4 and its association with psychiatric disorders. [Review]. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(9):RA215–220. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushparaj A, Hamani C, Yu W, Shin DS, Kang B, Nobrega JN, Le Foll B. Electrical stimulation of the insular region attenuates nicotine-taking and nicotine-seeking behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(4):690–698. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.235. doi: npp2012235 [pii] 10.1038/npp.2012.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph RJ, Varty GB, Kelly MA, Wang YM, Caron MG, Rubinstein M, Geyer MA. The dopamine D2, but not D3 or D4, receptor subtype is essential for the disruption of prepulse inhibition produced by amphetamine in mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19(11):4627–4633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04627.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Becker JB. Enduring changes in brain and behavior produced by chronic amphetamine administration: a review and evaluation of animal models of amphetamine psychosis. Brain Res. Rev. 1986;11:157–198. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(86)80193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving : an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondou P, Haegeman G, Van Craenenbroeck K. The dopamine D4 receptor: biochemical and signalling properties. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(12):1971–1986. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0293-y. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review] doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0293-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein M, Phillips TJ, Bunzow JR, Falzone TL, Dziewczapolski G, Zhang G, Grandy DK. Mice lacking dopamine D4 receptors are supersensitive to ethanol, cocaine, and methamphetamine. Cell. 1997;90(6):991–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoots O, Van Tol HH. The human dopamine D4 receptor repeat sequences modulate expression. Pharmacogenomics J. 2003;3(6):343–348. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500208. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500208 6500208 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Behavioral theories and the neurophysiology of reward. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:87–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Van Tol HH. Dopamine receptor pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15(7):264–270. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Adamson LK, Grocki S, Corrigall WA. Reinstatement and spontaneous recovery of nicotine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;130(4):396–403. doi: 10.1007/s002130050256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields PG, Lerman C, Audrain J, Bowman ED, Main D, Boyd NR, Caporaso NE. Dopamine D4 receptors and the risk of cigarette smoking in african-americans and caucasians. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers and prevention. 1998;7:453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres M-P, Bouthenet M-L, Schwartz J-C. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature. 1990;347(6289):146–151. doi: 10.1038/347146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stretch R, Gerber GJ. Drug-induced reinstatement of amphetamine self-administration behaviour in monkeys. Can J Psychol. 1973;27(2):168–177. doi: 10.1037/h0082466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara RK, Guan HC, O'Dowd BF, Seeman P, Laurier LG, Ng G, Niznik HB. Cloning of the gene for a human dopamine D5 receptor with higher affinity for dopamine than D1. Nature. 1991;350:614–619. doi: 10.1038/350614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara RK, Niznik HB, Weiner DM, Stormann TM, Brann MR, Kennedy JL. Human dopamine D1 receptor encoded by an intronless gene on chromosome 5. Nature. 1990;347:80–83. doi: 10.1038/347080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos P, Bermeo C, Rubinstein M, Suchland K, Wang G, Grandy D, Volkow N. Conditioned place preference and locomotor activity in response to methylphenidate, amphetamine and cocaine in mice lacking dopamine D4 receptors. J Psychopharmacol. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0269881109102613. doi: 0269881109102613 [pii] 10.1177/0269881109102613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos PK, Habibi R, Michaelides M, Patel UB, Suchland K, Anderson BJ, Volkow ND. Dopamine D4 receptor (D4R) deletion in mice does not affect operant responding for food or cocaine. Behav Brain Res. 2010;207(2):508–511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.10.020. doi: S0166-4328(09)00628-7 [pii] 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TC, Kruzich PJ, Joyce BM, Gash CR, Suchland K, Surgener SP, Glaser PE. Dopamine D4 receptor knockout mice exhibit neurochemical changes consistent with decreased dopamine release. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;166(2):306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.009. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton TG, Rossing MA, Bowen DJ, Srinouanprachan S, Wicklund K, Farin FM. Genetic polymorphisms in dopamine-related genes and smoking cessation in women: a prospective cohort study. Behav Brain Funct. 2007;3:22. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Cheng CY, Shu LR, Yang CY, Pan CW, Liou YJ, Hong CJ. No association for D2 and D4 dopamine receptor polymorphisms and methamphetamine abuse in Chinese males. Psychiatr Genet. 2002;12(1):29–33. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerio A, Belloni M, Gorno ML, Tinti C, Memo M, Spano P. Dopamine D2, D3, and D4 receptor mRNA levels in rat brain and pituitary during aging. Neurobiol Aging. 1994;15(6):713–719. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Craenenbroeck K, Borroto-Escuela DO, Romero-Fernandez W, Skieterska K, Rondou P, Lintermans B, Haegeman G. Dopamine D4 receptor oligomerization--contribution to receptor biogenesis. FEBS J. 2011;278(8):1333–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08052.x. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tol HH, Bunzow JR, Guan HC, Sunahara RK, Seeman P, Niznik HB, Civelli O. Cloning of the gene for a human dopamine D4 receptor with high affinity for the antipsychotic clozapine. Nature. 1991;350(6319):610–614. doi: 10.1038/350610a0. doi: 10.1038/350610a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tol HHM, Wu CM, Guan HC, O'Hara K, Bunzow JR, Civelli O, Janovic V. Multiple dopamine D4 receptor variants in the human population. Nature. 1992;358:149–152. doi: 10.1038/358149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbergh DJ, O'Connor RJ, Grant MD, Jefferson AL, Vogler GP, Strasser AA, Kozlowski LT. Dopamine receptor genes (DRD2, DRD3 and DRD4) and gene-gene interactions associated with smoking-related behaviors. Addict Biol. 2007;12(1):106–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington JL, O'Tuathaigh C, O'Sullivan G, Tomiyama K, Koshikawa N, Croke DT. Phenotypic studies on dopamine receptor subtype and associated signal transduction mutants: insights and challenges from 10 years at the psychopharmacology-molecular biology interface. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181(4):611–638. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0058-8. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review] doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells TT, Beevers CG, Knopik VS, McGeary JE. Dopamine D4 receptor gene variation is associated with context-dependent attention for emotion stimuli. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(3):525–534. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000478. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.] doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Bozarth MA. A psychomotor stimulant theory of addiction. Psychol. Rev. 1987;94:469–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley ML, Waters KA, Reavill C, Bull S, Lacroix LP, Martyn AJ, Dawson LA. Selective dopamine D4 receptor agonist (A-412997) improves cognitive performance and stimulates motor activity without influencing reward-related behaviour in rat. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19(8):765–776. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32831c3b06. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32831c3b06 00008877-200812000-00002 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL. Effects of a D1 and a D2 dopamine antagonist on the self-administration of cocaine and piribedil by rhesus monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24(3):531–535. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90553-8. doi: 0091-3057(86)90553-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Gilbert JG, Pak AC, Ashby CR, Jr., Heidbreder CA, Gardner EL. Selective dopamine D3 receptor antagonism by SB-277011A attenuates cocaine reinforcement as assessed by progressive-ratio and variable-cost-variable-payoff fixed-ratio cocaine self-administration in rats. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;21(12):3427–3438. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Nitta A, Mizuno T, Nakajima A, Yamada K, Nabeshima T. Discriminative-stimulus effects of methamphetamine and morphine in rats are attenuated by cAMP-related compounds. Behav Brain Res. 2006;173(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.05.029. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Pushparaj A, Gamaleddin I, Steiner RC, Picciotto MR, Roder J, Le Foll B. Nicotine-taking and nicotine-seeking in C57Bl/6J mice without prior operant training or food restriction. Behav Brain Res. 2012;230(1):34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.01.042. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Pushparaj A, Le Strat Y, Gamaleddin I, Barnes C, Justinova Z, Le Foll B. Blockade of dopamine d4 receptors attenuates reinstatement of extinguished nicotine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(3):685–696. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.245. [Research Support, N.I.H., Intramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokel RA, Pickens R. Drug level of d- and l-amphetamine during intravenous self-administration. Psychopharmacologia. 1974;34(3):255–264. doi: 10.1007/BF00421966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokel RA, Wise RA. Increased lever pressing for amphetamine after pimozide in rats: implications for a dopamine theory of reward. Science. 1975;187(4176):547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.1114313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou QZ, Grandy DK, Thambi L, Kushner JA, Van Tol HHM, Cone R, O. C. Cloning and expression of human and rat D1 dopamine receptors. Nature. 1990;347:76–86. doi: 10.1038/347076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]