Abstract

ADAMTS-18 is a member of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) family of proteases, which were known to play important roles in development, angiogenesis and coagulation; dysregulation and mutation of these enzymes have been implicated in many disease processes, such as inflammation, cancer, arthritis and atherosclerosis. Mutations of ADAMTS-18 have been linked to abnormal early eye development and reduced bone mineral density. In this review, we briefly summarize the structural organization and the expression of ADAMTS-18, review the alternative form and the truncated fragments of ADAMTS-18, focus on the emerging role of ADAMTS-18 in several pathophysiological conditions, including hematological diseases, tumorgenesis, osteogenesis, eye-related diseases, central nervous system disorders, and end with the perspective research of ADAMTS-18 and its potential as a promising diagnostic and therapeutic target in various kinds of diseases and conditions.

Keywords: ADAMTS-18, Alternative forms, Hemostasis, Tumor suppresser gene, Bone, Eye, Central nervous system, Review

2. INTRODUCTION

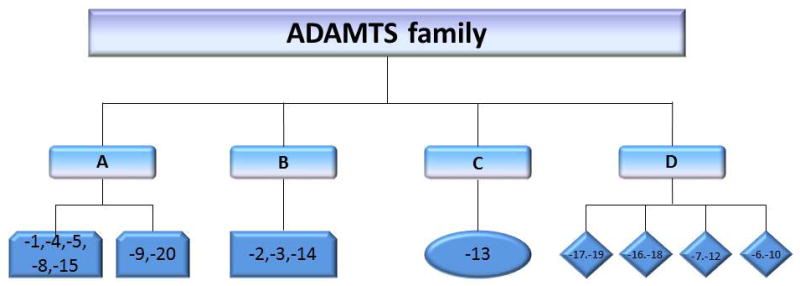

ADAMTS family was first identified in 1997 (1), since then the ADAMTS family has grown to 19 members. In detail, the first subgroup consists of ADAMTS-1, -4, -5, -8 and -15, while another consists of ADAMTS-9 and -20. Both divisions combine to form a larger subgroup. Another division includes ADAMTS-2, -3, and -14. ADAMTS-13 alone forms a unique group. Additionally, ADAMTS-17 and -19, ADAMTS-16 and -18, ADAMTS-7 and -12, and ADAMTS-6 and -10 consists the structurally-related ADAMTS pairs division (Figure 1) (2–5).

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of divisions of ADAMTS family. The ADAMTS family can be categorized by the structural similarities. Group A consists of two subgroups, in detail, ADAMTS-1, -4, -5, -8 and -15 form one subgroup, while another subgroup consists of ADAMTS-9 and -20. Group B includes ADAMTS-2, -3, and -14. ADAMTS-13 alone forms a dependent group C. ADAMTS-17 and -19, ADAMTS-16 and -18, ADAMTS-7 and -12, and ADAMTS-6 and -10 consist of the group D.

The ADAMTS family enzymes have been shown to be proteolytically active and to be involved normal physiological process or in the pathogenesis of various kinds of diseases. For instances, ADAMTS-1 is associated with follicular rupture and ovulation (6), ADAMTS-2, ADAMTS-3, and ADAMTS-14 are procollagen N-propeptidases (7–9), ADAMTS-1, -8, and -9 participate in the inhibitory process of angiogenesis (10–14). Mutations in the ADAMTS-2 gene have been implicated in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type 7C, which is named “Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, dermatosparactic type” according to the new nosology, a genetic condition characterized by procollagen processing (9, 15). Both ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 have been associated with the breakdown of cartilage via aggrecan degradation (16–21). ADAMTS-7 and ADAMTS-12 are associated with the pathological process of arthritis (5, 22–25). Mutations in ADAMTS-13 are associated with the development of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, a disease characterized by decreased numbers of circulating platelets (26).

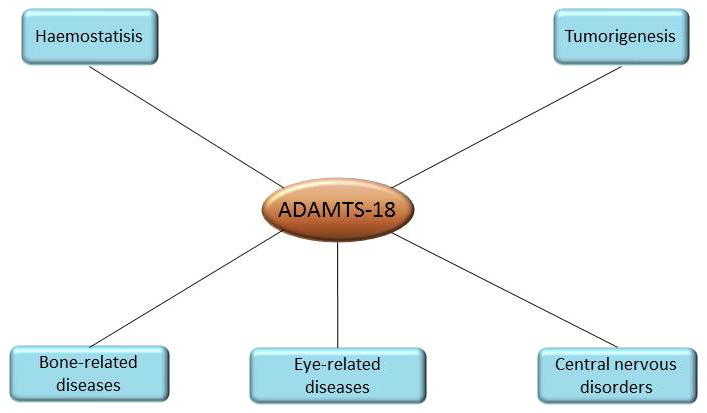

ADAMTS-18 was first identified in 2002 by bioinformatics screening of the human genome through sequence similarity to the metalloproteinase signature of previously described ADAMTS (27). It is reported that there is a significant percentage of identity of domain architecture between ADAMTS-16 and ADAMTS-18 (overall identities: 57%, catalytic domains: 85%) by amino acid sequence alignments analysis (27). ADAMTS-18 and ADAMTS-16 are assigned to a subgroup of ADAMTS family according to their similar structure. Although the potential roles of ADAMTS-18 in different tissues have been studied over past decade, the mechanisms underlying are still not clear. Particularly the substrate of ADAMTS-18 is still unknown. In this review, we will discuss our current understanding of ADAMTS-18 by focused on its potential role in different tissues and associated diseases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A schematic representation of ADAMTS-18’s multi-systemic functions. To date, the potential role of ADAMTS-18 in different tissues and associated diseases which have been discovered includes haemostatic balance maintain and tumor suppression. In addition, ADAMTS-18 may play an important role in bone-, eye- and CNS-related diseases due to the significant change of its expression. However, the mechanism is still not clear.

3. GENE, STRUCTURE, AND EXPRESSION OF ADAMTS-18

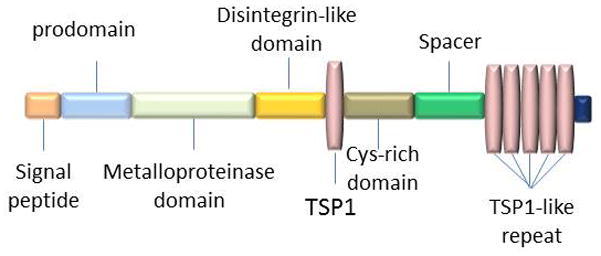

ADAMTS-18 gene is located on 16q23 in human genome (27, 28). The structure of ADAMTS-18 includes a signal peptide, a pro-domain, a metalloprotease domain, a disintegrin domain, a central TS-1 domain, a cys-rich domain, a spacer domain and a TS-1 like repeat domain (Figure 3) (27). In pro-domain, ADAMTS-18 contains a subtilisin-like pro-protein convertase cleavage site which is the furin recognition sequences. ADAMTS-18 can be cleaved at the N terminal by furin or related pro-protein convertases leading to secretion of mature ADAMTS-18 (27). Expression of ADAMTS-18 has been found in a variety of tissues in both human and mouse. In human fetal tissues, ADAMTS-18 is expressed in lung, liver, and kidney while in adult tissues ADAMTS-18 is detected in brain, prostate, submaxillary gland, endothelium, and retina (27, 29). In addition, ADAMTS-18 is also expressed in bone according to a genome-wide bone mass candidate genes analysis (30). Recently, ADAMTS-18 is also detected in heart, skeletal muscle, spleen, pancreas, esophagus, stomach, colon, larynx, breast, cervix, placenta, ovary, bone marrow and lymph node (28). Moreover, ADAMTS-18 truncation is detected in brain, kidney, lung, and testicle of C57BL/6 mice embryo by western blot assay (31). And ADAMTS-18 is also found in the lens and retina in the developing murine eyes (32).

Figure 3.

Domain structure and organization of ADAMTS-18. ADAMTS-18 consists of a signal peptide, prodomain, metalloprotease domain, disintegrin domain, the first thrombospondin type 1 repeat (TSP1), Cys-rich domain, spacer domain and 5 additional TSP1 repeats. Notably, the intact molecular weight (WM) of ADAMTS-18 is 135KD.

4. ALTERNATIVE FORM AND THE TRUNCATED FRAGMENTS OF ADAMTS-18

It has been shown that thrombin cleaved ADAMTS-18 (33) between Arg775 and Ser776 (31). Analysis of putative glycosylation sites in catalytic domain indicates that there is one consensus sequence (which is called NVT) for N-glycosylation in ADAMTS-18. ADAMTS-18 protein contains three repeats in the second thrombospondin module. In the process of transcription or translation, un-spliced intron or spliced exon may produce a stop codon, which lies in the region of coding the middle of ADAMTS-18’s third TS-1 like repeat domain, thus easily resulting in a truncated ADAMTS-18 motif (27). Analysis of the EST databank indicated that there was at least one EST (AV730422) corresponding to this region of ADAMTS-18, showing a sequence compatible with that reported herein (27). It was reported that there were always two bands (one is 135KDa while the other one is 75KDa) in the Western blot assay in the in vitro translation of ADAMTS-18 experiment (31). The size of intact ADAMTS-18 is 135KDa and the 75KDa band may indicate one of the isoforms of ADAMTS-18 (31). However, genetic codon optimization has no effect on production of ADAMTS-18 short form (31). In addition, both protease inhibitors and mutations in catalytic domain have no effect on the generation of ADAMTS-18 short form (31). The potential function of the alternative forms of ADAMTS-18 has been studied (34–36). It was reported that trADAMTS-18F650 (Met1–Phe650, cDNA constructs terminating at the corresponding conserved Phe residue of ADAMTS-18 as mentioned before (27)) was generated and purified to test its GAG-binding affinity and aggrecanase activity comparing with ADAMTS-5, 9 and 16 (36). trADAMTS-18F650 had no effective GAG-binding affinity or aggrecanase activity. In addition, trADAMTS-18F650 bound heparin poorly possibly due to lacking of a consensus heparin-binding sequence (XBBXBX) (36).

The inhibition assay using antibody against C-terminal of ADAMTS-18 provides evidence that ADAMTS-18 C terminal has function. A polyclonal antibody (pAb) against active C-terminal ADAMTS-18 fragment (ADAMTS-18C) was generated from rabbit by immunizing ADAMTS-18C recombinant protein (rADAMTS-18C) (35). The binding specificity was confirmed by ELISA and Western blot assay with rADAMTS-18C and natural ADAMTS-18 protein. And the bioactivity of pAb was tested in vivo and it has been shown that pAb shortened the mouse tail bleeding time in a dose-dependent manner indicating the role of ADAMTS-18 C-terminal fragment in regulating thrombus stability.

5. ROLES OF ADAMTS-18 IN VARIOUS PATHPHYSIOLOGICAL CONDITIONS

5.1 Hemostasis

Endothelial cell plays a central role in regulating the coagulation process (33, 37–40). Both reverse-transcription (RT)-PCR assay in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and immunocytochemistry assay in human tissue confirmed that endothelial cells could express and secrete ADAMTS-18 (33). It has been shown that thrombin and TNF-α as the HUVECs activators could enhance ADAMTS-18 secretion subsequently induced platelet fragmentation, platelet disaggregation, and thrombus dissolution after thrombin cleavage of ADAMTS-18 (33, 41, 42).

It has been reported that anti-GPIIIa49-66 antibodies commonly found in HIV-1 ITP patients induce destruction of platelets through sequential activation of 12-lipoxygenase and NADPH oxidase, which suggests another mechanism of platelet activation and death (33, 43–45). In order to find the physiological ligand interacts with GPIIIa49-66, the peptide reacted with GPIIIa49-66 was identified through phage surface display screening. It has been shown that the peptide interacts with GPIIIa49-66 had 70% homology with C-terminal sequence of ADAMTS-18. Both ADAMTS-18 and anti–GPIIIa49-66 Ab did not fragment platelets in GPIIIa−/− knockout mice and C-terminal truncated ADAMTS-18 had no binding affinity to platelets (33). In addition, a second rabbit antibody against the N-terminal domain of ADAMTS-18 was inactive while antibody against C-terminal domain significantly inhibited ADAMTS-18 induced platelet fragmentation (33). Since C-terminal portion of ADAMTS-18 might contain its functional properties interacting with GPIIIa, three truncated rADAMTS-18 were generated to determine the C-terminal function. They were rADAMTS-385-amino acid (AA) structure (contain the GPIIIa binding site), rADAMTS-188–amino acid structure (partial active) and rADAMTS-66–amino acid structure (do not contain the GPIIIa binding site) (33). And only rADAMTS-385-AA was potent with high platelet fragmentation. Furthermore, LDH release was measured to confirm that ADAMTS-18 C-terminal could induce platelet fragmentation. Accordingly, ADAMTS-18 C-terminal peptide is likely to be the physiological ligand interact with GPIIIa49-66 to induce platelet oxidative fragmentation (33).

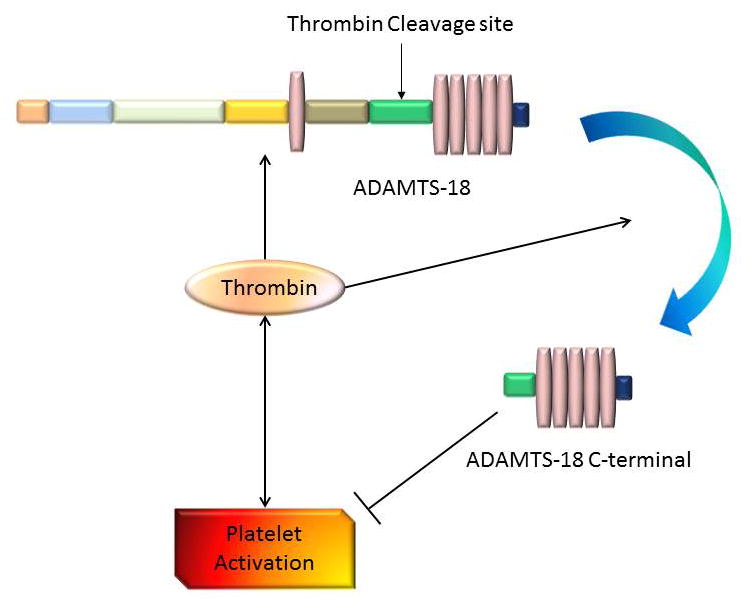

Thrombin is able to cleavage full length ADAMTS-18 into 85KDa and 45KDa molecular weight (MW) while the process could be inhibited by hirudin, the specific inhibitor of thrombin(33). The thrombin cleavage site was identified through mass spectrum assay and it is between Arg775 and Ser776 (31). Since thrombin was generated during the formation of thrombus formation and ADAMTS-18 was detected in plasma after thrombin stimulation (33, 46, 47), thrombin and ADAMTS-18 might interplay in the haemostatic process. These provocative findings highlight the physiologic processes regulating thrombus dissolution. However, the impairment of thrombin/ADAMTS-18–dependent platelet dissolution could conceivably produce a prothrombotic phenotype. It is also possible that thrombin/ADAMTS-18 could act as a safeguard in thrombin compromised situations (48, 49).

However, it seems that there is no difference in platelet aggregation trace and activation and adhesion on immobilized ligand by in vitro experiment compared between wild type and ADAMTS-18-deficient platelet (50). In addition, the expression profile data has not shown any ADAMTS-18 expression in megakaryocyte so far. Therefore, we would assume that in platelet there is no ADAMTS-18 regardless the platelets are from WT or ADAMTS-18-deficient mice. In that case, the function of platelets from both WT and ADAMTS-18-deficient should be the same. Furthermore, in vitro assays cannot simultaneously reproduce the interactions of all of the components of the haemostatic process that occur in vivo nor do they reflect the importance of haemodynamic factors resulting from blood flow (51).

It was reported in an ABSTRACT that ADAMTS-18 functioned as a pro-vasculature gene using ADAMTS-18-deficient mice model (50). It was confirmed that adventitial collagen deposition was increased in ADAMTS-18 knock-out mice by immunohistochemistry staining. In addition, ADAMTS-18-deficient mice had lower blood vessel density compared to wild type mice. Without ADAMTS-18, the vessels show a premature phenotype resulting in a lower blood flow. The hemodynamic change leads to a shorter time of thrombus formation. And it was proven in a transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) model that knock-out mice got a bigger infarction size (50). Perhaps the vascular change finally affects thrombus formation in some extent.

ADAMTS-18 had been reported to be down regulated in the rapid atrial pacing (RAP) model of pig (52). RAP model was established to mimic the atrial fibrillation (AF) which was the most commonly sustained cardiac arrhythmia disease and AF was characterized as an independent and important risk factor of stroke (53–56). Since ADAMTS-18 was proven to have a protective role in several thrombosis models including stroke (33), the down-regulation of ADAMTS-18 might contribute to aggravating the haemostatic imbalance in the endocardium resulting in thrombus formation (52).

Take all together, current data apparently support the concept that the interaction of ADAMTS-18 with thrombin may play an important role in maintaining the systemic haemostatic balance (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Interaction between thrombin and ADAMTS-18 in haemostatic balance. Endothelial cell can express ADAMTS-18. Thrombin increases the expression of ADAMTS-18 while have the ability to cleave it into 45KD active C-terminal. ADAMTS-18 C-terminal inhibits while thrombin promotes the platelet aggregation. Notably, thrombin cleavage site is in the spacer domain between Arg775 and Ser776. Abbreviations: arrows indicate a stimulatory effect; perpendicular lines indicate an inhibitory effect.

5.2 Tumor

The potential role of ADAMTS-18 in tumor mestastasis and tumor genesis was first suggested by the genetic linkage analysis (28). It has been shown that the loss of heterozygosity assay of 16q23 region is strongly associated with a variety of cancers. Since ADAMTS-18 is one of these genes located around 16q23 region, it has been studied as a potential oncogene. The fact that the mutations and high methylated promoter of ADAMTS-18 gene are strongly associated with a variety of tumors suggests that ADMATS-18 could be a tumor suppressor gene. (28, 57–62).

ADAMTS-18 was down-regulated in multiple samples of carcinoma cell lines such as esophageal, nasopharyngeal (28). Although there indeed was a homozygous 16q23.1. deletion in some carcinoma, the decreased expression of ADAMTS-18 was not due to this deletion. In fact, ADAMTS-18 is not in this deletion in all these described cell lines (28). The silenced or reduced expression of ADAMTS-18 is likely due to the methylation of ADAMTS-18 CGI (CpG Island, (63–65)). The tumor-specific methylation of ADAMTS-18 CGI was further supported by the fact that there is little methylation of CGI of ADAMTS-18 in non-tumor cell lines. Both pharmacological inhibitors and genetic mutation were used for the demethylation indicating that ADAMTS-18 silence was directly mediated by CGI methylation (28). High-resolution melting (HRM) analysis was used to determine the ADAMTS-18 methylation status in gastric, colorectal and pancreatic cancers as well as their adjacent normal tissues (58, 66–69). Data showed that ADAMTS-18 was highly methylated in tissues with tumor than in normal tissues. ADAMTS-18 expression level was inversely correlated with methylation status level and no evidence was identified between ADAMTS-18 methylation status and TNM staging in tumor (58, 70–72). Since ADAMTS-18 was silenced or down-regulated in tumor, re-express ADAMTS-18 in different tumor cell lines resulted in significantly reduced colony number both in monolayer and soft agar culture indicating ADAMTS-18 suppresses both anchorage-dependent and anchorage-independent tumor growth (28). Moreover, data showed that ADAMTS-18 was methylated in a large collection of primary carcinoma samples (28). Thus, ADAMTS-18 could be a biomarker for the cancer diagnosis and prognosis prediction.

Although ADAMTS-18 gene was not deleted in many carcinomas as described previously, it is reported that ADAMTS-18 gene was deleted in the breast cancer (57). Both single nucleotide polymorphism-comparative genomic hybridization (SNP-CGH) and the LOH analysis indicated ADAMTS-18 functioned as a tumor suppressor gene (TSG). The 16q deletion was associated with better prognosis (57).

Despite the fact that ADAMTS-18 was methylated or deleted in some carcinomas, it was reported that ADAMTS-18 mutant was involved in the melanoma (59). It has been shown that ADAMTS-18 mutant promoted growth, migration, and metastasis of melanoma.(59). Melanoma is one of the skin diseases accompanied by a series of genetic changes (73–75). 408 ADAMTS exons genes which were extracted from genomic databases from 31 melanoma patients were analyzed. Data showed that ADAMTS-18 was highly mutated and the mutant was positively selected during tumorigenesis. Analysis of cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix components indicated that mutant ADAMTS-18-expressing cells had lower adhesion ability to laminin-I compared with wild type (WT) cells resulting in facilitation of cell migration. Mutant ADAMTS-18 was identified as essential for the migration of melanoma by analysis of migration after ADAMTS-18 knock-down. This concept was further supported by in vivo experiment (59).

5.3 Bone-related diseases

ADAMTS-18 has been shown to be correlated with bone-related diseases in genetic analysis and meta-analysis microarray (30, 76–78). It was reported that ADAMTS-18 was a bone mass candidate gene in different ethnic groups (30, 76). Bone mineral density (BMD) was a prominent osteoporosis risk factor (79–81). Masses of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were genotyped in different ethnic groups indicating that both ADAMTS-18 and TGFBR3 were BMD candidate genes (30). In addition, Meta-analyses supported the significant associations of ADAMTS-18 and TGFBR3 with BMD (30). One SNP (rs16945612) was found to generate a binding site for the transcription factor TEL2. Furthermore, allele “C” of rs16945612 might enhance TEL2 factor binding ability and thus repressed the expression of ADAMTS-18 and subsequently enhanced the osteoporosis phenotype (30, 82). Moreover, a genome-wide association study of BMD in premenopausal women shows an association between femoral neck BMD and rs1826601 near the 5′ terminus of ADAMTS-18 (76). The NCBI GEO expression profiles showed that the ADAMTS-18 level was significantly lower in subjects with nonunion fractures than normal subjects (83). Thus, decreased ADAMTS-18 expression may contribute to the non-healing of skeletal fractures (30).

Evidence showed that ADAMTS-18 was correlated with kyphosis in swine (77). Kyphosis in human was a condition of over-curvature of the thoracic vertebrae, which could be either the result of degenerative diseases (such as arthritis), developmental problems (Scheuermann’s disease), osteoporosis with compression fractures of the vertebrae, or trauma(84). However, Spine curvature defects had been reported in swine herds for the past three decades (85). Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) associations were performed with 198 SNPs and microsatellite markers in Duroc-Landrace-Yorkshire resource (USMARC) population and F2 population. Data showed that ADAMTS-18 on SSC6 was significantly associated with kyphosis trait in the F2 population of swine (P≤0.0.5) while it seemed no association with USMARC resource herd. Thus, the association of ADAMTS-18 with kyphosis might be differed by population(77).

Study has shown that ADAMTS-18 was about 2.6.4-fold up-regulated in permanent periodontal ligament (PDL) tissues compared with deciduous PDL by cDNA microarray analysis and quantitative reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis (78). Periodontal ligament (PDL) is known to be the most important tissue for the attenuation and conduction of masticatory forces and connection of the tooth to the alveolar jaw bone in the area surrounding the root surfaces (78, 86–89). It is reported that in permanent PDL cells IL-6 was up-regulated resulting in the increased expressions of ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 (78, 90). However, ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5 were the key enzymes degrading extracellular matrix (91). Although it is unknown whether IL-6 and ADAMTS-18 were related and what their mechanisms are, it is intriguing to examine whether ADAMTS-18 and IL-6 play a part in the turnover of the extracellular matrix in permanent PDL tissues.

5.4 Eye-related diseases

It was reported that ADAMTS-18 was a novel gene associated with Knobloch syndrome (KS) by combining exome and homozygosity mapping in 13 patients of Saudi in origin and consanguineous (32). Knobloch syndrome is an autosomal recessive disease characterized by developing disorder of the eye and the occipital skull bone defect (92–96). After excluding COL18A1 (identified as the KS disease gene and 17 mutations have been reported to date (97–100)), analysis was undertaken to identify that ADAMTS-18 was associated with Knobloch syndrome (32). However, the conclusion was corrected by the same group (101). It was reported that the KS case reported by this group was due to biallelic mutations in COL18A1 and ADAMTS-18 variant probably did not influence the phenotype of Knobloch syndrome disease (101).

Homozygosity mapping and whole exome sequencing were used to identify that ADAMTS-18 gene was responsible for autosomal recessive disease of retinal dystrophy (29). Inherited retinal dystrophies (IRD) were heterogeneous disorders characterized by a progressive loss of visual acuity (VA) and deterioration of the visual field (VF) (102–104). Only a single homozygous missense variation named c.T3235 > C in the ADAMTS-18 gene was identified to be related to IRD by SNPs genotyping analysis. In addition, ADAMTS-18 was detected on human retina. Furthermore, ADAMTS-18 knockdown model was used to analyze its function. Data showed that there was a notable increase of light-induced rod photoreceptor damage in ADAMTS-18 knockdown compared with wild type fish by immunofluorescence analysis. In addition, there was a reduction of about 50% of the Rhodopsin-positive retinal areas in ADAMTS-18-deficient eyes as compared with wild type eyes. What is worth to mention is that ADAMTS-18-deficient model also had an aberrant central nervous system (CNS) phenotype which could be rescued by injecting the full-length coding human ADAMTS-18 synthetic mRNA (29).

Biallelic mutation in the gene on 16q23.1. enoding ADAMTS-18 caused MMCAT syndrome (105). MMCAT syndrome is a distinct syndrome featuring microcornea, myopic chorioretinal atrophy, telecanthus (106). Data showed that MMCAT syndrome was an autosomal recessive disease linked to chromosome of 16q23.1.

Taken together, since ADAMTS-18 was detected in eyes and ADAMTS-18 had genetic linkage to some hereditary ophthalmological diseases, ADAMTS-18 might participate in the pathological process of eye-related diseases.

5.5 Central nervous system

It was reported that ADAMTS-18 was related to the brain’s white matter integrity (107). Genome-wide association analysis of 542,050 SNPs with gFA was undertaken in 72–74 years old healthy people. gFA is a global measure of white matter tract integrity which is derived from principal components analysis of tract-averaged fractional anisotropy measurements, accounting for 38.6.% of the individual differences across the white matter tract. Among the genome-wide association study, the strongest association was with rs7192208 whose SNP was located in an intron of the gene ADAMTS-18. Although, rs7192208 was nominally associated with almost all 12 white matter tracts by post hoc analysis, rs7192208 was most significantly linked to the left arcuate fasciculus. Moreover, the addition of the minor allele (G) in rs7192208 was associated with decreased gFA. Furthermore, 30 exon probes that specific for ADAMTS-18 were tested by online resources indicated that 21 exon probes were associated with rs7192208 in brain tissue. However, rs7192208 was not associated with ADAMTS-18 in lymphoblastoid cell lines (SNPexp) or peripheral blood mononuclear cell tissue suggesting that rs7192208 influences ADAMTS-18 expression through cisacting genetic regulation in the brain (107, 108). In contrast, the association of ADAMTS-18 was not so strong by gene-based analysis possibly due to the underlying genetic architecture of the gene. It is worthy to mention that the top five tissues where ADAMTS-18 was overexpressed are the cerebellar vermis, cerebellum, cerebellar hemisphere, transverse colon, and the corpus callosum (NextBio Body Atlas; nextbio.com) (107). Further study the function of ADAMTS-18 in brain white matter would shed light on the role of ADAMTS-18 in central nervous system.

6. SUMMARY AND PERSPECTIVE

ADAMTS-18 has been shown to be a bone mass candidate and genetically associated with some diseases such as inherited retinal dystrophies (IRD), MMCAT syndrome and brain white matter integrity degeneration. In addition, ADAMTS-18 functions as a tumor suppressor gene which is almost epigenetically silenced in all carcinoma cell lines resulting from methylation. It is deleted with some other genes in breast cancer. ADAMTS-18 C-terminal plays a unique role in maintaining haemostatic balance by inducing platelet fragmentation.

Although it is reported that ADAMTS-18 can cleave aggrecan despite the low efficiency at the aggrecanase site of Glu373-Ala374, efforts needs to be invested to identify the substrates of ADAMTS-18, which is the key to understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying ADAMTS-18 regulations of various kinds of diseases and conditions. It is a reasonable speculation that ADAMTS-18 should interact with its substrate around where it is present such as endothelial cells. Although growing evidences indicate that ADAMTS-18 is a metalloproteinase with multiple functions, the exact expression profiling, regulation and function of ADAMTS-18 in various pathophysiological processes, especially the signaling pathways and molecular events, remain to be delineated. Further study would help us to understand better of the function and regulation of ADAMTS-18.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge that Dr. Stephen Tsang in Columbia University who helps us review this paper. This work is supported partly by NIH research grants R01AR062207, R01AR061484, R56AI100901, a Disease Targeted Research Grant from American College of Rheumatology Research and Education Foundation.

Footnotes

- ECM

Extracellular Matrix

- ADAMTS

A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin Motifs

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MW

molecular weight

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- RAP

rapid atrial pacing

- HRM

High-resolution melting

- SNP-CGH

single nucleotide polymorphism-comparative genomic hybridization

- TSG

tumor suppressor gene

- BMD

Bone mineral density

- PDL

permanent periodontal ligament

- KS

Knobloch syndrome

- VF

visual field

- VA

visual acuity

- CNS

central nervous system

- pAb

polyclonal antibody

References

- 1.Kuno K, Kanada N, Nakashima E, Fujiki F, Ichimura F, Matsushima K. Molecular cloning of a gene encoding a new type of metalloproteinase-disintegrin family protein with thrombospondin motifs as an inflammation associated gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(1):556–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llamazares M, Cal S, Quesada V, Lopez-Otin C. Identification and characterization of ADAMTS-20 defines a novel subfamily of metalloproteinases-disintegrins with multiple thrombospondin-1 repeats and a unique GON domain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(15):13382–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson AC, Malik SB, Logsdon JM, Jr, Van Meir EG. Functional evolution of ADAMTS genes: evidence from analyses of phylogeny and gene organization. BMC Evol Biol. 2005;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin EA, Liu CJ. The role of ADAMTSs in arthritis. Protein Cell. 2010;1(1):33–47. doi: 10.1007/s13238-010-0002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robker RL, Russell DL, Espey LL, Lydon JP, O’Malley BW, Richards JS. Progesterone-regulated genes in the ovulation process: ADAMTS-1 and cathepsin L proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(9):4689–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080073497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colige A, Vandenberghe I, Thiry M, Lambert CA, Van Beeumen J, Li SW, Prockop DJ, Lapiere CM, Nusgens BV. Cloning and characterization of ADAMTS-14, a novel ADAMTS displaying high homology with ADAMTS-2 and ADAMTS-3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(8):5756–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes RJ, Hirohata S, Engle JM, Colige A, Cohn DH, Eyre DR, Apte SS. Procollagen II amino propeptide processing by ADAMTS-3. Insights on dermatosparaxis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(34):31502–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colige A, Sieron AL, Li SW, Schwarze U, Petty E, Wertelecki W, Wilcox W, Krakow D, Cohn DH, Reardon W, Byers PH, Lapiere CM, Prockop DJ, Nusgens BV. Human Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VII C and bovine dermatosparaxis are caused by mutations in the procollagen I N-proteinase gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(2):308–17. doi: 10.1086/302504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georgiadis KE, Hirohata S, Seldin MF, Apte SS. ADAM-TS8, a novel metalloprotease of the ADAM-TS family located on mouse chromosome 9 and human chromosome 11. Genomics. 1999;62(2):312–5. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark ME, Kelner GS, Turbeville LA, Boyer A, Arden KC, Maki RA. ADAMTS9, a novel member of the ADAM-TS/metallospondin gene family. Genomics. 2000;67(3):343–50. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rocks N, Paulissen G, Quesada-Calvo F, Munaut C, Gonzalez ML, Gueders M, Hacha J, Gilles C, Foidart JM, Noel A, Cataldo DD. ADAMTS-1 metalloproteinase promotes tumor development through the induction of a stromal reaction in vivo. Cancer Res. 2008;68(22):9541–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu Y, Nagy JA, Brown LF, Shih SC, Johnson PY, Chan CK, Dvorak HF, Wight TN. Proteolytic cleavage of versican and involvement of ADAMTS-1 in VEGF-A/VPF-induced pathological angiogenesis. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59(5):463–73. doi: 10.1369/0022155411401748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn JR, Reed JE, du Plessis DG, Shaw EJ, Reeves P, Gee AL, Warnke P, Walker C. Expression of ADAMTS-8, a secreted protease with antiangiogenic properties, is downregulated in brain tumours. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(8):1186–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colige A, Nuytinck L, Hausser I, van Essen AJ, Thiry M, Herens C, Ades LC, Malfait F, Paepe AD, Franck P, Wolff G, Oosterwijk JC, Smitt JH, Lapiere CM, Nusgens BV. Novel types of mutation responsible for the dermatosparactic type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (Type VIIC) and common polymorphisms in the ADAMTS2 gene. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123(4):656–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickinson SC, Vankemmelbeke MN, Buttle DJ, Rosenberg K, Heinegard D, Hollander AP. Cleavage of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (thrombospondin-5) by matrix metalloproteinases and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs. Matrix Biol. 2003;22(3):267–78. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cudic M, Burstein GD, Fields GB, Lauer-Fields J. Analysis of flavonoid-based pharmacophores that inhibit aggrecanases (ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5) and matrix metalloproteinases through the use of topologically constrained peptide substrates. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74(5):473–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00885.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohmander LS, Neame PJ, Sandy JD. The structure of aggrecan fragments in human synovial fluid. Evidence that aggrecanase mediates cartilage degradation in inflammatory joint disease, joint injury, and osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(9):1214–22. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malfait AM, Liu RQ, Ijiri K, Komiya S, Tortorella MD. Inhibition of ADAM-TS4 and ADAM-TS5 prevents aggrecan degradation in osteoarthritic cartilage. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(25):22201–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandy JD, Verscharen C. Analysis of aggrecan in human knee cartilage and synovial fluid indicates that aggrecanase (ADAMTS) activity is responsible for the catabolic turnover and loss of whole aggrecan whereas other protease activity is required for C-terminal processing in vivo. Biochem J. 2001;358(Pt 3):615–26. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3580615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tortorella MD, Burn TC, Pratta MA, Abbaszade I, Hollis JM, Liu R, Rosenfeld SA, Copeland RA, Decicco CP, Wynn R, Rockwell A, Yang F, Duke JL, Solomon K, George H, Bruckner R, Nagase H, Itoh Y, Ellis DM, Ross H, Wiswall BH, Murphy K, Hillman MC, Jr, Hollis GF, Newton RC, Magolda RL, Trzaskos JM, Arner EC. Purification and cloning of aggrecanase-1: a member of the ADAMTS family of proteins. Science. 1999;284(5420):1664–6. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5420.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai XH, Wang DW, Luan Y, Yu XP, Liu CJ. Regulation of chondrocyte differentiation by ADAMTS-12 metalloproteinase depends on its enzymatic activity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(4):667–80. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo F, Lai Y, Tian Q, Lin EA, Kong L, Liu C. Granulin-epithelin precursor binds directly to ADAMTS-7 and ADAMTS-12 and inhibits their degradation of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(7):2023–36. doi: 10.1002/art.27491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai Y, Bai X, Zhao Y, Tian Q, Liu B, Lin EA, Chen Y, Lee B, GACT, Beier F, Yu XP, Liu CJ. ADAMTS-7 forms a positive feedback loop with TNF-alpha in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu CJ. The role of ADAMTS-7 and ADAMTS-12 in the pathogenesis of arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2009;5(1):38–45. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy GG, Nichols WC, Lian EC, Foroud T, McClintick JN, McGee BM, Yang AY, Siemieniak DR, Stark KR, Gruppo R, Sarode R, Shurin SB, Chandrasekaran V, Stabler SP, Sabio H, Bouhassira EE, Upshaw JD, Jr, Ginsburg D, Tsai HM. Mutations in a member of the ADAMTS gene family cause thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Nature. 2001;413(6855):488–94. doi: 10.1038/35097008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cal S, Obaya AJ, Llamazares M, Garabaya C, Quesada V, Lopez-Otin C. Cloning, expression analysis, and structural characterization of seven novel human ADAMTSs, a family of metalloproteinases with disintegrin and thrombospondin-1 domains. Gene. 2002;283(1–2):49–62. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00861-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin H, Wang X, Ying J, Wong AH, Li H, Lee KY, Srivastava G, Chan AT, Yeo W, Ma BB, Putti TC, Lung ML, Shen ZY, Xu LY, Langford C, Tao Q. Epigenetic identification of ADAMTS18 as a novel 16q23.1. tumor suppressor frequently silenced in esophageal, nasopharyngeal and multiple other carcinomas. Oncogene. 2007;26(53):7490–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peluso I, Conte I, Testa F, Dharmalingam G, Pizzo M, Collin RW, Meola N, Barbato S, Mutarelli M, Ziviello C, Barbarulo AM, Nigro V, Melone MA, Simonelli F, Banfi S. The ADAMTS18 gene is responsible for autosomal recessive early onset severe retinal dystrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiong DH, Liu XG, Guo YF, Tan LJ, Wang L, Sha BY, Tang ZH, Pan F, Yang TL, Chen XD, Lei SF, Yerges LM, Zhu XZ, Wheeler VW, Patrick AL, Bunker CH, Guo Y, Yan H, Pei YF, Zhang YP, Levy S, Papasian CJ, Xiao P, Lundberg YW, Recker RR, Liu YZ, Liu YJ, Zmuda JM, Deng HW. Genome-wide association and follow-up replication studies identified ADAMTS18 and TGFBR3 as bone mass candidate genes in different ethnic groups. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84(3):388–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Zhang W, Yi Z, Wang S, Li Z. Identification of a thrombin cleavage site and a short form of ADAMTS-18. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;419(4):692–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aldahmesh MA, Khan AO, Mohamed JY, Alkuraya H, Ahmed H, Bobis S, Al-Mesfer S, Alkuraya FS. Identification of ADAMTS18 as a gene mutated in Knobloch syndrome. J Med Genet. 2011;48(9):597–601. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z, Nardi MA, Li YS, Zhang W, Pan R, Dang S, Yee H, Quartermain D, Jonas S, Karpatkin S. C-terminal ADAMTS-18 fragment induces oxidative platelet fragmentation, dissolves platelet aggregates, and protects against carotid artery occlusion and cerebral stroke. Blood. 2009;113(24):6051–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dang S, Hong T, Bu D, Tang J, Fan J, Zhang W. Optimized refolding and characterization of active C-terminal ADAMTS-18 fragment from inclusion bodies of Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2012;82(1):32–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dang S, Bu D, Hong T, Zhang W. A polyclonal antibody against active C-terminal ADAMTS-18 fragment. Hybridoma (Larchmt) 2011;30(6):567–9. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2011.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeng W, Corcoran C, Collins-Racie LA, Lavallie ER, Morris EA, Flannery CR. Glycosaminoglycan-binding properties and aggrecanase activities of truncated ADAMTSs: comparative analyses with ADAMTS-5, -9, -16 and -18. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760(3):517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Hinsbergh VW. Endothelium--role in regulation of coagulation and inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34(1):93–106. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0285-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jennings LK. Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102(2):248–57. doi: 10.1160/TH09-03-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minami T, Sugiyama A, Wu SQ, Abid R, Kodama T, Aird WC. Thrombin and phenotypic modulation of the endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(1):41–53. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099880.09014.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lovren F, Verma S. Evolving role of microparticles in the pathophysiology of endothelial dysfunction. Clin Chem. 2013;59(8):1166–74. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.199711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li ZD, Nardi M, Pan RM, Yee H, Karpatkin S. A new mechanism of platelet activation and oxidative death induced by ADAMTS-18 and regulating bleeding time. Blood. 2007;110(11):47a–48a. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li ZD, Nardi MA, Feinmark SJ, Karpatkin S. A new mechanism of platelet activation, oxidation and death induced by ADAMTS-18. Blood. 2005;106(11):193a–193a. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nardi M, Tomlinson S, Greco MA, Karpatkin S. Complement-independent, peroxide-induced antibody lysis of platelets in HIV-1-related immune thrombocytopenia. Cell. 2001;106(5):551–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00477-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nardi MA, Gor Y, Feinmark SJ, Xu F, Karpatkin S. Platelet particle formation by anti GPIIIa49-66 Ab, Ca2+ ionophore A23187, and phorbol myristate acetate is induced by reactive oxygen species and inhibited by dexamethasone blockade of platelet phospholipase A2, 12-lipoxygenase, and NADPH oxidase. Blood. 2007;110(6):1989–96. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nardi M, Feinmark SJ, Hu L, Li Z, Karpatkin S. Complement-independent Ab-induced peroxide lysis of platelets requires 12-lipoxygenase and a platelet NADPH oxidase pathway. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(7):973–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI20726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mazepa M, Hoffman M, Monroe D. Superactivated platelets: thrombus regulators, thrombin generators, and potential clinical targets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(8):1747–52. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whayne TF. A review of the role of anticoagulation in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease. Int J Angiol. 2012;21(4):187–94. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1330232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Esmon CT. The interactions between inflammation and coagulation. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;131(4):417–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arthur JF, Jackson SP. Is thrombin the problem or (dis)solution? Blood. 2009;113(24):6046–6047. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei Zhang DB, Dang Suying, Hong Tao, Wisniewski Thomas. Adamts-18 Is a Novel Candidate Gene Of Vascular Development That Is Related To Aggravated Thrombosis: Evidence From a Adamts-18 Knock Out Mice. Blood. 2013;122(21 31 ):0006–4971. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bellido-Martin L, Chen V, Jasuja R, Furie B, Furie BC. Imaging fibrin formation and platelet and endothelial cell activation in vivo. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(5):776–82. doi: 10.1160/TH10-12-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cervero J, Segura V, Macias A, Gavira JJ, Montes R, Hermida J. Atrial fibrillation in pigs induces left atrial endocardial transcriptional remodelling. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(4):742–9. doi: 10.1160/TH12-05-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chao TF, Liu CJ, Chen SJ, Wang KL, Lin YJ, Chang SL, Lo LW, Hu YF, Tuan TC, Chen TJ, Tsao HM, Chen SA. Hyperuricemia and the risk of ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation - Could it refine clinical risk stratification in AF? Int J Cardiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ciaccio EJ, Biviano AB, Garan H. The dominant morphology of fractionated atrial electrograms has greater temporal stability in persistent as compared with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Comput Biol Med. 2013;43(12):2127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakahara S, Kamijima T, Hori Y, Tsukada N, Okano A, Takayanagi K. Substrate modification by adding ablation of localized complex fractionated electrograms after stepwise linear ablation in persistent atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10840-013-9848-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pillarisetti J, Patel A, Bommana S, Guda R, Falbe J, Zorn GT, Muehlebach G, Vacek J, Sue Min L, Lakkireddy D. Atrial fibrillation following open heart surgery: long-term incidence and prognosis. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10840-013-9830-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nordgard SH, Johansen FE, Alnaes GI, Bucher E, Syvanen AC, Naume B, Borresen-Dale AL, Kristensen VN. Genome-wide analysis identifies 16q deletion associated with survival, molecular subtypes, mRNA expression, and germline haplotypes in breast cancer patients. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47(8):680–96. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Z, Zhang W, Shao Y, Zhang C, Wu Q, Yang H, Wan XB, Zhang J, Guan M, Wan J, Yu B. High-resolution melting analysis of ADAMTS18 methylation levels in gastric, colorectal and pancreatic cancers. Medical Oncology. 2010;27(3):998–1004. doi: 10.1007/s12032-009-9323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wei XM, Prickett TD, Viloria CG, Molinolo A, Lin JC, Cardenas-Navia I, Cruz P, Rosenberg SA, Davies MA, Gershenwald JE, Lopez-Otin C, Samuels Y, Progra NCS. Mutational and Functional Analysis Reveals ADAMTS18 Metalloproteinase as a Novel Driver in Melanoma. Molecular Cancer Research. 2010;8(11):1513–1525. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lopez-Otin C, Matrisian LM. Emerging roles of proteases in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(10):800–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, Parsons DW, Lin J, Barber TD, Mandelker D, Leary RJ, Ptak J, Silliman N, Szabo S, Buckhaults P, Farrell C, Meeh P, Markowitz SD, Willis J, Dawson D, Willson JK, Gazdar AF, Hartigan J, Wu L, Liu C, Parmigiani G, Park BH, Bachman KE, Papadopoulos N, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314(5797):268–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagstaff L, Kelwick R, Decock J, Edwards DR. The roles of ADAMTS metalloproteinases in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2011;16:1861–72. doi: 10.2741/3827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16(1):6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu Z, Taylor JA. Genome-wide age-related DNA methylation changes in blood and other tissues relate to histone modification, expression, and cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013 doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peille AL, Brouste V, Kauffmann A, Lagarde P, Le Morvan V, Coindre JM, Chibon F, Bresson-Bepoldin L. Prognostic Value of PLAGL1-Specific CpG Site Methylation in Soft-Tissue Sarcomas. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wojdacz TK, Dobrovic A, Algar EM. Rapid detection of methylation change at H19 in human imprinting disorders using methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(10):1255–60. doi: 10.1002/humu.20779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wojdacz TK, Dobrovic A, Hansen LL. Methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(12):1903–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Virmani AK, Tsou JA, Siegmund KD, Shen LY, Long TI, Laird PW, Gazdar AF, Laird-Offringa IA. Hierarchical clustering of lung cancer cell lines using DNA methylation markers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(3):291–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wittwer CT, Reed GH, Gundry CN, Vandersteen JG, Pryor RJ. High-resolution genotyping by amplicon melting analysis using LCGreen. Clin Chem. 2003;49(6 Pt 1):853–60. doi: 10.1373/49.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471–4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ng WT, Yuen KT, Au KH, Chan OS, Lee AW. Staging of nasopharyngeal carcinoma - The past, the present and the future. Oral Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rice TW, Blackstone EH. Esophageal cancer staging: past, present, and future. Thorac Surg Clin. 2013;23(4):461–9. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, Patel HN, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, Cho KH, Aiba S, Brocker EB, LeBoit PE, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(20):2135–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu H, He Z, Simon HU. Autophagy suppresses melanoma tumorigenesis by inducing senescence. Autophagy. 2013;10(2) doi: 10.4161/auto.27163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Koller DL, Ichikawa S, Lai D, Padgett LR, Doheny KF, Pugh E, Paschall J, Hui SL, Edenberg HJ, Xuei X, Peacock M, Econs MJ, Foroud T. Genome-wide association study of bone mineral density in premenopausal European-American women and replication in African-American women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(4):1802–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lindholm-Perry AK, Rohrer GA, Kuehn LA, Keele JW, Holl JW, Shackelford SD, Wheeler TL, Nonneman DJ. Genomic regions associated with kyphosis in swine. BMC Genet. 2010;11:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-11-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Song JS, Hwang DH, Kim SO, Jeon M, Choi BJ, Jung HS, Moon SJ, Park W, Choi HJ. Comparative gene expression analysis of the human periodontal ligament in deciduous and permanent teeth. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iida T, Harada T, Ishizaki F, Nitta Y, Aoi S, Ikeda H, Chikamura C, Shiokawa M, Nitta K. Changes in bone mineral density and metabolism in women: evaluation of bodily characteristics, bone metabolic markers and bone mineral density. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 2013;62(3):49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tunon-Le Poultel D, Cannata-Andia JB, Roman-Garcia P, Diaz-Lopez JB, Coto E, Gomez C, Naves-Diaz M, Rodriguez I. Association of matrix Gla protein gene functional polymorphisms with loss of bone mineral density and progression of aortic calcification. Osteoporos Int. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2577-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nybo M, Jespersen B, Aarup M, Ejersted C, Hermann AP, Brixen K. Determinants of bone mineral density in patients on haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis--a cross-sectional, longitudinal study. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2013;23(3):342–50. doi: 10.11613/BM.2013.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ralston SH. Osteoporosis as an Hereditary Disease. Clinic Rev Bone Miner Metab. 2010;8:68–76. doi: 10.1.007/s12018-010-9073-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rodriguez EK, Boulton C, Weaver MJ, Herder LM, Morgan JH, Chacko AT, Appleton PT, Zurakowski D, Vrahas MS. Predictive factors of distal femoral fracture nonunion after lateral locked plating: A retrospective multicenter case-control study of 283 fractures. Injury. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lewis JS, Valentine RE. Clinical measurement of the thoracic kyphosis. A study of the intra-rater reliability in subjects with and without shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lahrmann KH, Hartung K. (Causes of kyphotic and lordotic curvature of the spine with cuneiform vertebral deformation in swine) Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 1993;106(4):127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schrock P, Lupke M, Seifert H, Staszyk C. Finite element analysis of equine incisor teeth. Part 2: Investigation of stresses and strain energy densities in the periodontal ligament and surrounding bone during tooth movement. Vet J. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schrock P, Lupke M, Seifert H, Borchers L, Staszyk C. Finite element analysis of equine incisor teeth. Part 1: Determination of the material parameters of the periodontal ligament. Vet J. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim SE, Yun YP, Han YK, Lee DW, Ohe JY, Lee BS, Song HR, Park K, Choi BJ. Osteogenesis induction of periodontal ligament cells onto bone morphogenic protein-2 immobilized PCL fibers. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;99:700–9. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Staszyk C, Gasse H. Distinct fibro-vascular arrangements in the periodontal ligament of the horse. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50(4):439–47. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mimata Y, Kamataki A, Oikawa S, Murakami K, Uzuki M, Shimamura T, Sawai T. Interleukin-6 upregulates expression of ADAMTS-4 in fibroblast-like synoviocytes from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15(1):36–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Verma P, Dalal K. ADAMTS-4 and ADAMTS-5: key enzymes in osteoarthritis. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(12):3507–14. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aldahmesh MA, Khan AO, Mohamed JY, Levin AV, Wuthisiri W, Lynch S, McCreery K, Alkuraya FS. No evidence for locus heterogeneity in Knobloch syndrome. J Med Genet. 2013;50(8):565–6. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bongiovanni CS, Ferreira CC, Rodrigues AP, Fortes Filho JB, Tartarella MB. Cataract surgery in Knobloch syndrome: a case report. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:735–7. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S18989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gorlin RJ, Knobloch WH. Syndromes of genetic juvenile retinal detachment. Z Kinderheilkd. 1972;113(2):81–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00473403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Williams TA, Kirkby GR, Williams D, Ainsworth JR. A phenotypic variant of Knobloch syndrome. Ophthalmic Genet. 2008;29(2):85–6. doi: 10.1080/13816810701850041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Khan AO, Aldahmesh MA, Mohamed JY, Al-Mesfer S, Alkuraya FS. The distinct ophthalmic phenotype of Knobloch syndrome in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(6):890–5. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kliemann SE, Waetge RT, Suzuki OT, Passos-Bueno MR, Rosemberg S. Evidence of neuronal migration disorders in Knobloch syndrome: clinical and molecular analysis of two novel families. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;119A(1):15–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Keren B, Suzuki OT, Gerard-Blanluet M, Bremond-Gignac D, Elmaleh M, Titomanlio L, Delezoide AL, Passos-Bueno MR, Verloes A. CNS malformations in Knobloch syndrome with splice mutation in COL18A1 gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(13):1514–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Menzel O, Bekkeheien RC, Reymond A, Fukai N, Boye E, Kosztolanyi G, Aftimos S, Deutsch S, Scott HS, Olsen BR, Antonarakis SE, Guipponi M. Knobloch syndrome: novel mutations in COL18A1, evidence for genetic heterogeneity, and a functionally impaired polymorphism in endostatin. Hum Mutat. 2004;23(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/humu.10284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mahajan VB, Olney AH, Garrett P, Chary A, Dragan E, Lerner G, Murray J, Bassuk AG. Collagen XVIII mutation in Knobloch syndrome with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A(11):2875–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Aldahmesh MA, Khan AO, Mohamed JY, Levin AV, Wuthisiri W, Lynch S, McCreery K, Alkuraya FS. No evidence for locus heterogeneity in Knobloch syndrome. J Med Genet. 2013;50(8):565–566. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bok D. Contributions of genetics to our understanding of inherited monogenic retinal diseases and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(2):160–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Prokofyeva E, Troeger E, Wilke R, Zrenner E. Early visual symptom patterns in inherited retinal dystrophies. Ophthalmologica. 2011;226(3):151–6. doi: 10.1159/000330381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Prokofyeva E, Troeger E, Zrenner E. The special electrophysiological signs of inherited retinal dystrophies. Open Ophthalmol J. 2012;6:86–97. doi: 10.2174/1874364101206010086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Aldahmesh MA, Alshammari MJ, Khan AO, Mohamed JY, Alhabib FA, Alkuraya FS. The syndrome of microcornea, myopic chorioretinal atrophy, and telecanthus (MMCAT) is caused by mutations in ADAMTS18. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(9):1195–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.22374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Khan AO. Microcornea with myopic chorioretinal atrophy, telecanthus and posteriorly-rotated ears: a distinct clinical syndrome. Ophthalmic Genet. 2012;33(4):196–9. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2012.681097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lopez LM, Bastin ME, Maniega SM, Penke L, Davies G, Christoforou A, Valdes Hernandez MC, Royle NA, Tenesa A, Starr JM, Porteous DJ, Wardlaw JM, Deary IJ. A genome-wide search for genetic influences and biological pathways related to the brain’s white matter integrity. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(8):1847 e1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Heinzen EL, Ge D, Cronin KD, Maia JM, Shianna KV, Gabriel WN, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Hulette CM, Denny TN, Goldstein DB. Tissue-specific genetic control of splicing: implications for the study of complex traits. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(12):e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]