Abstract

Objectives

Adherence to prehospital guidelines and protocols is suboptimal. Insight into influencing factors is necessary to improve adherence. The aim of this study was to identify factors that influence ambulance nurses’ adherence to a National Protocol Ambulance Care (NPAC).

Methods

A questionnaire was developed using the literature, a questionnaire and expert opinion. Ambulance nurses (n=452) from four geographically spread emergency medical services (EMSs) in the Netherlands were invited to fill out the questionnaire. The questionnaire included questions on influencing factors and self-reported adherence.

Results

Questionnaires were returned by 248 (55%) of the ambulance nurses. These ambulance nurses’ adherence to the NPAC was 83.4% (95% confidence interval 81.9–85.0). Bivariate correlations showed 23 influencing factors that could be related to the individual professional, organization, protocol characteristics and social context. Multilevel regression analysis showed that 21% of the variation in adherence (R2=0.208) was explained by protocol characteristics and social influences.

Conclusion

Ambulance nurses’ self-reported adherence to the NPAC seems high. To improve adherence, protocol characteristics (complexity, the degree of support for diagnosis and treatment, the relationship of the protocol with patient outcomes) and social influences (expectance of colleagues to work with the national protocol) should be addressed.

Keywords: clinical protocols, emergency medical services, emergency medical technicians, guideline adherence

Introduction

To support implementation of evidence in clinical practice, evidence-based guidelines and protocols have been developed 1. Guidelines consist of systematically developed recommendations to aid practitioner and patient decisions on appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances 2. To aid implementation of guidelines, protocols can be developed that formulate exactly which steps to follow 3. Despite the existence of these guidelines and protocols, a gap between available evidence and clinical practice often exists 1,4. A systematic review showed that patients in acute care settings received 53.5% of recommended care 5. Specifically in the prehospital setting, guideline adherence rates were low for patients with cardiac arrest, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, traumatic brain injury and in need of oxygen 6. This review also indicated that guideline deviations showed higher rates of mortality and adverse events.

To stimulate adherence to guidelines and protocols, it is important to identify influencing factors 7. In general, factors influencing the implementation of guidelines were related to the characteristics of professionals, patients, environment, guidelines and implementation strategies used 8. For the prehospital setting in particular, factors related to the patient (age, sex, presentation of disease, comorbidity), professional (knowledge, attitude, educational level, communication), organization (location of the emergency department, presence of a physician) and protocols (lacking or inadequate protocols) were identified 9–12. As only one qualitative study focused on the professionals’ perspective, insight into influencing factors from the perspective of prehospital professionals is needed. Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify the factors that influence adherence to a National Protocol Ambulance Care (NPAC) from the perspective of ambulance nurses.

Methods

Setting

In the Netherlands, ambulances are staffed with one driver and one ambulance nurse. Qualified ambulance nurses are registered nurses with an additional ICU, coronary care unit (CCU), emergency department (ED) or anaesthesia education and several years of working experience. Ambulance nurses work autonomously with their national protocol without the direct supervision of a physician. Emergency medical services (EMSs) are managed by EMS physicians, who are responsible for the medical care. The EMS physician is not present on site, but can be consulted by the ambulance nurses when they judge that this is necessary.

To support clinical practice by ambulance nurses, the Dutch ambulance care national sector organization developed a NPAC as the professional standard for prehospital ambulance care 13. The NPAC consists of flowcharts categorized into general topics (e.g. hygiene, handover, starting/stopping treatment), cardiology, neurology, pulmonology, internal medicine, traumatology, paediatrics, gynaecology, psychiatry and intoxications. These flowcharts are based on a mixture of evidence, best practice and expert opinion. Since its publication, the NPAC has a central position in the national ambulance nurses’ training course. The NPAC is updated every 3 years and all ambulance nurses receive a hardcopy (NPAC version 7.2 is avaliable at: http://visio.ambulancezorg.nl/LPA7.2/). Ambulance nurses are allowed to deviate from the NPAC with valid arguments and are required to register the deviations including the justification 13.

Design and framework

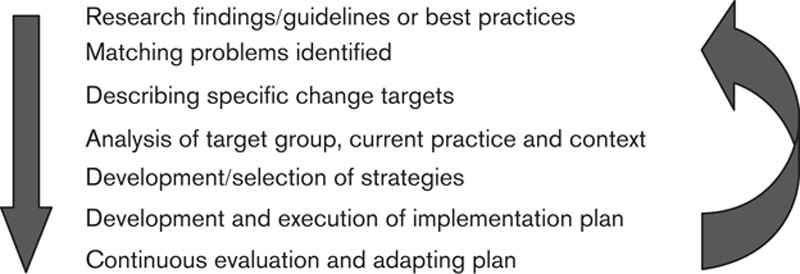

We adopted a quantitative, correlational design and used Grol’s model for effective implementation as a framework (Fig. 1) 3,4. The model provides a stepwise approach for improving clinical practice and starts with the identification of research findings or guidelines that have to be implemented (step 1). Steps 2 and 3 include a description of (change) targets and an analysis of the target group, current practice and setting. On the basis of the analysis, implementation strategies can be selected or developed (step 4), followed by the execution and evaluation of an implementation plan (steps 5 and 6).

Fig. 1.

Grol’s model for effective implementation.

As the NPAC has already been introduced into clinical practice, this study focuses on the third step of the model: an analysis of the target group, setting and current practice. The analysis focused on individual, organizational and social factors, and protocol characteristics 3.

Questionnaire

A questionnaire on influencing factors from the perspective of ambulance nurses was developed, including sociodemographics, degree of self-reported adherence and influencing factors related to the individual, organization, social context and protocol characteristics (Table 2). The questions on the individual, organizational and social factors were based on the implementation literature 3, previous qualitative studies 9,14 and expert opinion. The statements on protocol characteristics were developed by modifying the instrument ‘Attitudes Regarding Practice Guidelines’ 15,16. This instrument showed a good test–retest reliability and internal consistency. From this instrument, the statements on hand hygiene were excluded as these were beyond our purpose, and the general statements were modified for the Dutch setting and the NPAC. These general statements were translated into Dutch by three independent researchers and backward translated into English by a qualified translator. For answers to questions, a six-point Likert scale was used. Most questions were positively formulated and some were reversely phrased. Self-report adherence was measured as a continuous variable on a scale ranging from 0 to 100 per cent. Ambulance nurses could rate their own adherence by answering the question ‘to what degree do you adhere to the NPAC?’. The questionnaire was reviewed, adjusted and face validated by emergency care experts: ambulance nurses (two), emergency physicians (one) and researchers (one).

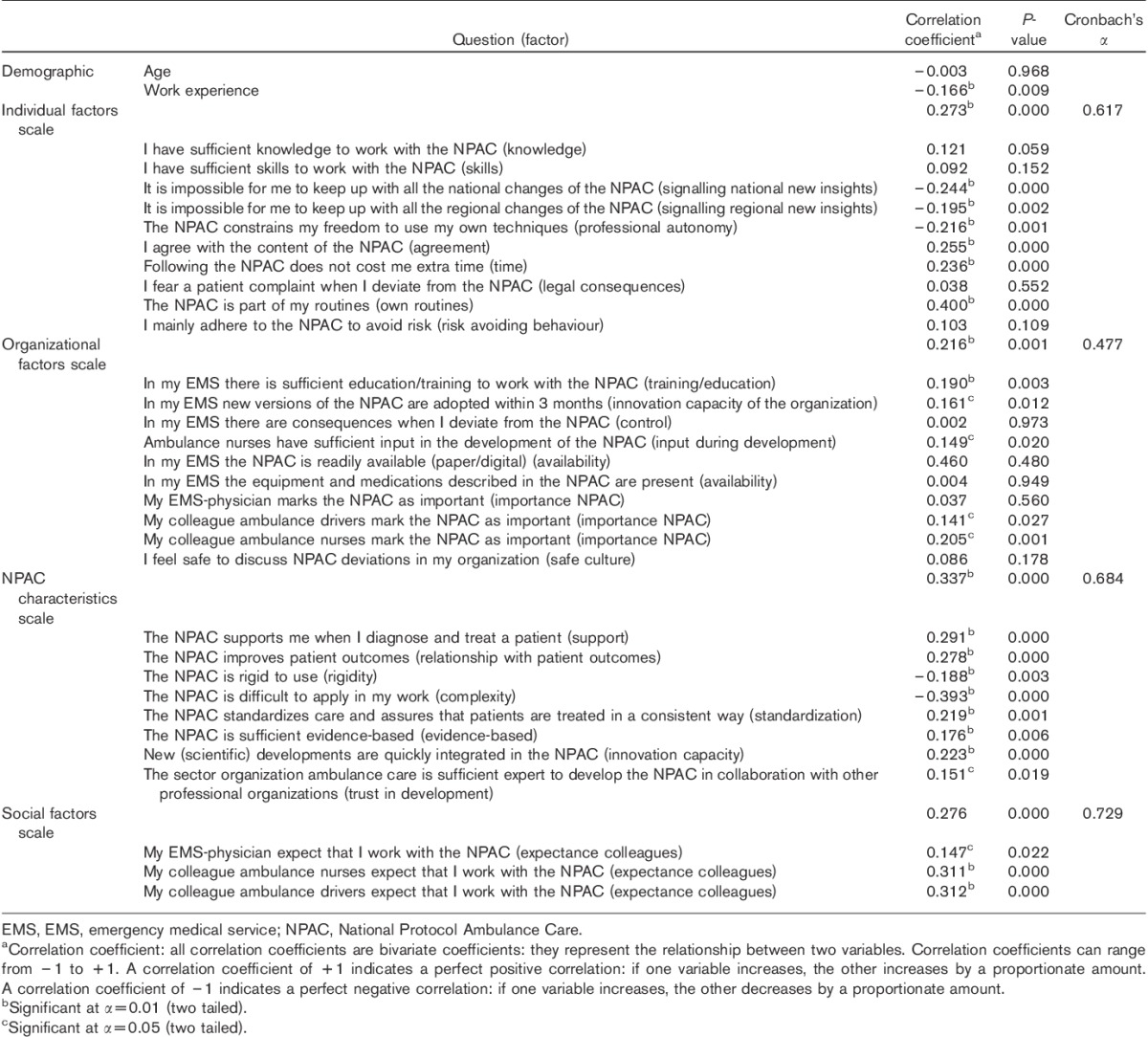

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations between factors and adherence rate

Sample

The study population included ambulance nurses as the primary target group for the NPAC. To select the ambulance nurses, we took a sample (n=4) from all EMSs (n=25) in the Netherlands. Geographical spreading ensured coverage over the country. All ambulance nurses (n=452) employed at these four EMSs received an e-mail with a hyperlink to the digital questionnaire by a contact person at their EMS, being either an ambulance nurse or an EMS physician. The ambulance nurses filled in the questionnaires in April and May 2012. Completed questionnaires were digitally returned to the research team. All ambulance nurses received three digital reminders with the hyperlink to the questionnaire.

Data analysis

Demographic data were analysed using descriptive statistics. To identify relationships between factors and ambulance nurses’ self-reported adherence, two-tailed Pearson’s (r) and Spearman’s (rs) correlation coefficients were computed. To assess the reliability of the scales, Cronbach’s α was computed. Relationships between scales, demographics and ambulance nurses’ adherence were determined using multiple regression analysis. Considering the data as hierarchical by clustering the respondents into four EMSs, we used multilevel regression analysis with EMSs as a random effect. Statistical significance was set at P-value less than 0.05. For all analyses, we used the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA).

Ethical considerations

The recommendations of the Dutch Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects were implemented following the step-by-step review plan (http://www.ccmo-online.nl/main.asp?pid=1&taal=1). Ethical approval of a certified healthcare ethics committee was not needed.

Results

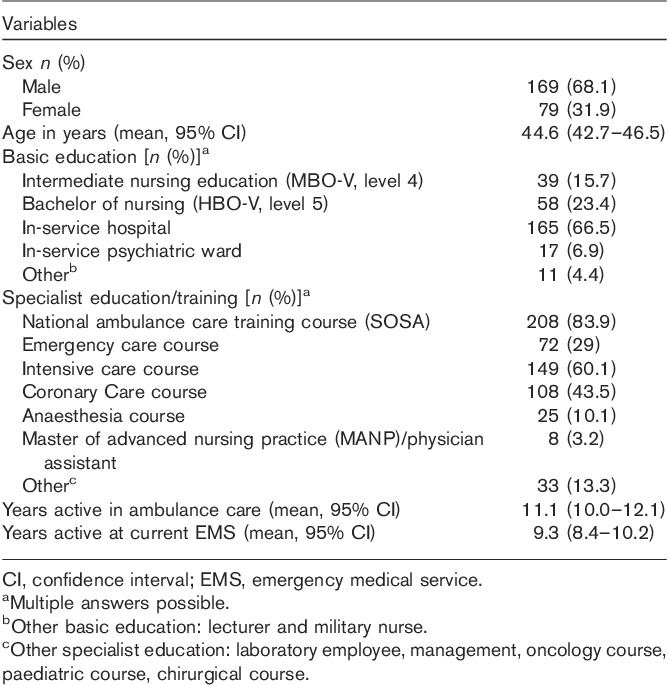

The questionnaire was returned by 248/452 (55%) of the ambulance nurses. Table 1 shows the respondents’ characteristics. Two-thirds of the respondents were men, mean age 44.6 years. Most ambulance nurses completed the national ambulance care training course as specialist education. Average years active in ambulance care was 11.1 years. The ambulance nurses reported an average adherence rate to the NPAC of 83.4% (95% confidence interval 81.9–85.0), with a range of 35–100%.

Table 1.

Ambulance nurses’ characteristics (n=248)

Table 2 shows bivariate associations between the scales and ambulance nurses’ self-reported adherence, as well as reliability scores for internal consistency of the scales. The individual factors scale (α=0.617), the protocol characteristics scale (α=0.684) and the social factors scale (α=0.729) showed satisfactory reliability scores for internal consistency. The organizational factors scale showed a relatively low internal consistency score (α=0.477). All scales were correlated positively with self-reported adherence, with rs=0.273 for the individual factors scale (P=0.000), rs=0.216 for the organizational factors scale (P=0.001), rs=0.337 for the protocol characteristics scale (P=0.000) and rs=0.276 for the social factors scale (P=0.000).

At the individual item level, higher adherence was related to agreement with the NPAC (rs=0.255, P=0.000), lower time investment (rs=0.236, P=0.000) and the ambulance nurses considering the NPAC as part of their own routines (rs=0.400, P=0.000). Lower adherence was related to more work experience (r=−0.166, P=0.009), higher professional autonomy (rs=−0.216, P=0.001) and difficulties for ambulance nurses in keeping up with national (rs=−0.244, P=0.000) and regional (rs=−0.195, P=0.002) changes of the NPAC.

At the organizational level, higher adherence was related to ambulance nurses perceiving sufficient education and training to work with the NPAC (rs=0.190, P=0.003), ambulance nurses indicating higher innovative capacity of the organization (rs=0.161, P=0.012), more ambulance nurses’ input during development of the NPAC (rs=0.149, P=0.020), and to colleague ambulance nurses (rs=0.205, P=0.001) and colleague ambulance drivers (rs=0.141, P=0.027), marking the NPAC as important.

According to the NPAC characteristics scale, adherence was higher when ambulance nurses perceived the NPAC as supportive for diagnosis and treatment (rs=0.291, P=0.000), perceived a positive relationship with patient outcomes (rs=0.278, P=0.000), perceived the NPAC as a tool to standardize care (rs=0.219, P=0.001), perceived the NPAC sufficient evidence-based (rs=0.176, P=0.006), trusted the developers of the NPAC (rs=0.151, P=0.019) and believed that scientific developments are quickly integrated into the NPAC (rs=0.223, P=0.000). Lower adherence rates correlated with increasing rigidity (rs=−0.188, P=0.003) and higher complexity of the NPAC (rs=−0.393, P=0.000).

At the social level, higher adherence rates correlated with increasing degree of EMS physicians’ (rs=0.147, P=0.022), ambulance nurses’ (rs=0.311, P=0.000) and ambulance drivers’ (rs=0.312, P=0.000) expectancy to work with the NPAC.

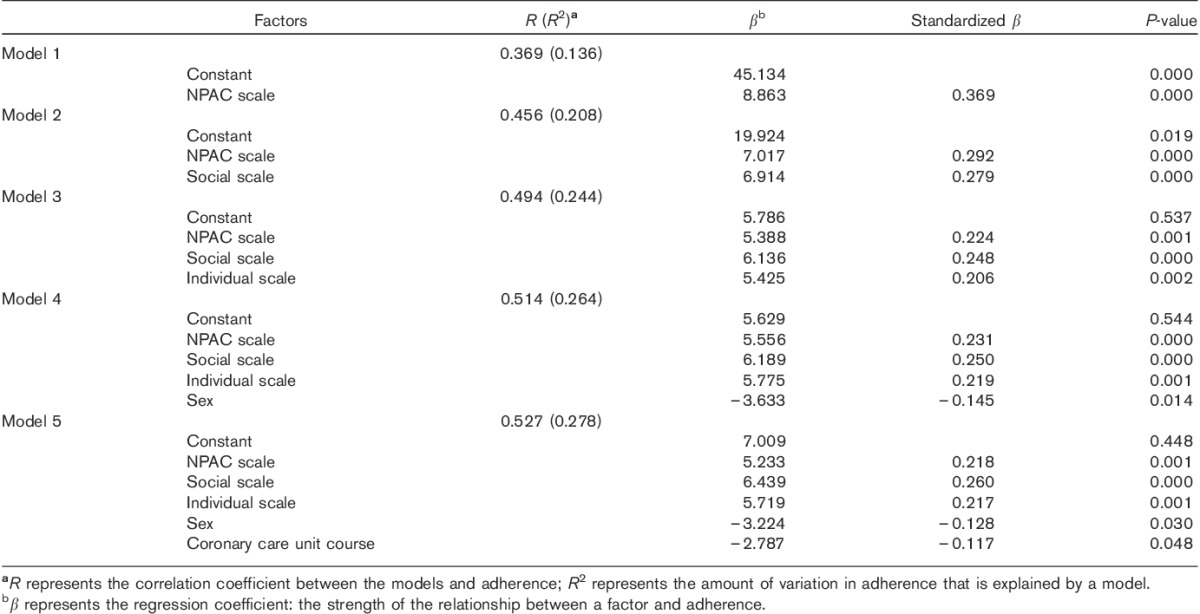

Together with the sociodemographic variables, all four scales were entered into a multiple regression analysis using the backward and forward stepwise methods. Because of the small number of nurses who had an MANP or a PA specialist education (n=8) and the nonspecificity of the ‘other education’ category (n=11), these variables were not entered into the analyses. Both backward and forward methods showed comparable models; therefore, only the forward method models are presented in Table 3. The best-fitting forward model (R=0.527, R2=0.278) included five predictors: NPAC scale, social factors scale, individual factors scale, sex and CCU additional education. These predictors were then entered into a multilevel model taking into account clustering of predictors in the EMSs. The final multilevel model did not include CCU additional education as a predictor, but for all other factors, the multilevel model did not differ from the best forward model.

Table 3.

Forward regression analysis

Discussion

This study identified factors that influence ambulance nurses’ adherence to a NPAC. Ambulance nurses’ self-reported adherence rate was 83.4% (95% confidence interval 81.9–85.0). Twenty-one per cent of variation in adherence could be explained by two factors: protocol characteristics and social influences (R=0.456, R2=0.208).

Compared with the total population of ambulance nurses in the Netherlands, our sample is representative in terms of the distribution of sex and age, but participants had somewhat more years of experience in ambulance care 17. The protocol adherence rate is high in comparison with other researches 6. An obvious explanation is the self-report method, which is known to cause response bias and overestimation 18. Appropriate methods to overcome overestimation of adherence rates are checking patient records, using clinical vignettes or video tape observations 12,19,20. Although the self-reported adherence rate is relatively high, it still indicates room for improvement. Complete adherence to the NPAC, however, is not a priori best practice as the NPAC is not entirely evidence-based and a clear relationship between the NPAC and patient outcomes has not been established. Also, contextual factors and patient preferences may require deviations. Furthermore, criteria and situations for protocol deviations are often unclear 21. Therefore, ambulance nurses should use their professional judgement when applying the NPAC and can only deviate from the protocol with clear motivation. Nevertheless, other reasons such as standardization and uniformity of care also justify the focus on protocol adherence.

For transparency, we have reported all five models of the forward regression analysis (Table 3), but our results indicate that 21% of the adherence variation can be explained by protocol (NPAC) characteristics and social influences (model 2). Protocol-related factors including complexity, support for diagnosis and treatment, and a relationship with patient outcomes seem to influence adherence. The complexity of guidelines and protocols was reported previously as a factor influencing adherence 8,22. In combination with our results, this stresses the need to make protocols less complex for ambulance nurses. To reduce complexity, the intended target group can be involved in protocol development, which has been indicated as an effective strategy 23. Also, draft protocols can be tested for complexity in small-scale practice settings. To reduce patient risks and limit the burden on daily practice, high-fidelity simulation settings to test protocol complexity and applicability seem promising. During simulations, participants are able to try and rehearse ‘new’ clinical practice, even if it concerns rare or complex situations 24.

The lack of expectation that adhering to specific recommendations will lead to improved patient outcomes is reported as a barrier for physicians’ adherence 15. Our study showed a positive correlation between adherence and a positive patient outcome expectancy of the ambulance nurses, indicating that adherence might improve when prehospital protocols are clearly related to positive patient outcomes.

At the social level, especially the expectancy of colleague ambulance nurses and drivers to work with the NPAC correlate with adherence positively. The support of colleagues can be a motivator for professionals to change their behaviour 3, and might even improve protocol adherence.

In the best-fitting model, 72% of variation in adherence remains unexplained. This could possibly be explained by the study’s focus on adherence to the NPAC as a whole and not on individual protocols in the NPAC. This is in line with a systematic review that describes the reasons for nonadherence on the level of guideline recommendations instead of the whole guideline 25. Another explanation for nonadherence can be the local protocols that compete with the NPAC: some EMSs make adjustments to the NPAC because of the local health policy. Competing local protocols influencing adherence to a national protocol have been reported previously 14. Furthermore, patient characteristics such as age and sex may influence adherence 11.

Implications for practice, education and future research

Studies showed that nonadherence to guidelines leads to higher rates of mortality and adverse events 10,12. Therefore, protocol adherence should be improved by strategies aimed at influencing factors 4. Adherence to the NPAC in the Netherlands may benefit from organizational strategies that provide a role for ambulance nurses during protocol development. Furthermore, educational strategies should focus on positive outcome expectancy providing evidence-based rationale for interventions in the NPAC. In this way, ambulance nurses can observe the relationship between the NPAC and patient outcomes.

Our results may stimulate ambulance nurses to become involved in protocol development. EMSs should involve the intended target group when developing or adjusting protocols. Our results may also contribute towards prehospital education and training for nurses by providing information on how to implement protocols. As our study is one of the first studies to quantify factors influencing adherence in the prehospital setting, future research should corroborate these findings and additionally take into account the perspective of the patient and situational factors. Thereby, it is important to identify general barriers as well as barriers related to specific medical conditions or topics as barriers can be located at the level of the whole guideline or an isolated guideline recommendation 25.

Limitations

Besides self-report bias, selection bias of responding ambulance nurses who are in favour of the NPAC is possible. Furthermore, ambulance nurses might deviate from the NPAC without being aware of the deviation, and therefore did not report these deviations as nonadherence. Another limitation is the 55% response rate. Also, as the Dutch ambulance care system is nurse based, with specific educational requirements, the results may not be fully transferrable to other countries. Finally, the internal consistency of the organizational factors scale was relatively low, which may indicate that the organizational factors scale did not have optimal operationalization.

Conclusion

Ambulance nurses’ self-reported adherence to the NPAC seems high, with 83% adherence, although there may be some overestimation because of self-reporting. Twenty-one per cent of the variance in adherence can be explained by factors related to the protocol itself and social influences. The main protocol characteristics were complexity, the degree of support for diagnosis and treatment and the relationship of the protocol with patient outcomes. Social influences include the degree to which colleagues expect nurses to work with the national protocol. To stimulate ambulance nurses’ adherence, multifactorial tailored implementation strategies are needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Loes Josemanders and Femke van Uden for their support during data collection and analysis.

The study was funded by a grant from the Netherlands organization for health research and development ZonMw (Project Number 8271.2001). The funding organization had no involvement in the study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cone DC. Knowledge translation in the emergency medical services: a research agenda for advancing prehospital care. Acad Emerg Med 2007; 14:1052–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field MJ, Lohr MJ. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program 1990Washington DC: National Academy Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M. Improving patient care. The implementation of change in clinical practice 2005Toronto: Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Achterberg T, Schoonhoven L, Grol R. Nursing implementation science: how evidence-based nursing requires evidence-based implementation. J Nurs Scholarsh 2008; 40:302–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, Kerr EA. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:2635–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebben RHA, Vloet LCM, Verhofstad MH, Meijer S, Mintjes-de Groot JAJ, van Achterberg T. Adherence to guidelines and protocols in the prehospital and emergency care setting: a systematic review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2013; 21:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figgis K, Slevin O, Cunningham JB. Investigation of paramedics’ compliance with clinical practice guidelines for the management of chest pain. Emerg Med J 2010; 27:151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francke AL, Smit MC, de Veer AJ, Mistiaen P. Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: a systematic meta-review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2008; 8:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berben SAA, THJM Meijs, van Grunsven PM, Schoonhoven L, van Achterberg T. Facilitators and barriers in pain management for trauma patients in the chain of emergency care. Injury 2012; 43:1397–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charpentier S, Sagnes-Raffy C, Cournot M, Cambou JP, Ducassé JL, Lauque D, Puel J. Determinants and prognostic impact of compliance with guidelines in reperfusion therapy for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from the ESTIM Midi-Pyrenees Area. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2009; 102:387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzharris M, Stevenson M, Middleton P, Sinclair G. Adherence with the pre-hospital triage protocol in the transport of injured patients in an urban setting. Injury 2012; 43:1368–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirves H, Skrifvars MB, Vahakuopus M, Ekström K, Martikainen M, Castren M. Adherence to resuscitation guidelines during prehospital care of cardiac arrest patients. Eur J Emerg Med 2007; 14:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sector Organisation Ambulance Care. Ambulance Care National Protocol (ANP) version 7.2 2011Zwolle: Stichting LAMP. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebben RHA, Vloet LCM, Schalk DM, Mintje-de Groot JAJ, van Achterberg T. An Exploration of factors influencing ambulance and emergency nurses’ protocol adherence in the Netherlands. J Emerg Nurs 2014; 40:124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PAC, Rubin HR. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999; 282:1458–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larson E. A tool to assess barriers to adherence to hand hygiene guideline. Am J Infect Control 2004; 32:48–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stichting Ambulancezorg Nederland. Ambulances in zicht 2011 2011Tiel: Stimio Consultants Drukwerk & Design. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Lomas J, Ross-Degnan D. Evidence of self-report bias in assessing adherence to guidelines. Int J Qual Health Care 1999; 11:187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemoyne S, De Paepe P, Vankeirsbilck C, Buylaert W. An inquiry on pain management in the emergency department of training hospitals. Acta Clin Belg 2011; 66:405–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santora TA, Trooskin SZ, Blank CA, Clarke JR, Schinco MA. Video assessment of trauma response: adherence to ATLS protocols. Am J Emerg Med 1996; 14:564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koerselman GF, Korzec A. A proposed checklist when deviating from guidelines. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2008; 152:1757–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grilli R, Lomas J. Evaluating the message: the relationship between compliance rate and the subject of a practice guideline. Med Care 1994; 32:202–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sachs M. Successful strategies and methods of nursing standards implementation. Pflege 2006; 19:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis R, Strachan A, Smith MM. Is high fidelity simulation the most effective method for the development of non-technical skills in nursing? A review of the current evidence. Open Nurs J 2012; 6:82–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Westert GP. Effects of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on quality of care: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2009; 18:385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]