Abstract

The lymphatic system is essential for generation of immune responses by facilitating the immune cell trafficking to lymph nodes. Dendritic cells (DCs), the most potent antigen presenting cells, exit tissues via lymphatic vessels, but the mechanisms of interaction between DCs and lymphatic endothelium and their potential implications for immune responses are poorly understood. Here, we demonstrate that lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) modulate maturation and function of DCs. Direct contact of human monocyte-derived DCs with inflamed, TNF-α-stimulated lymphatic endothelium reduced expression of costimulatory molecule CD86 by DCs and suppressed DC ability to induce T-cell proliferation. These effects were dependent on adhesive interactions between DCs and LECs, which were mediated by binding of Mac-1 on DCs to ICAM-1 on LECs. Importantly, the suppressive effects of lymphatic endothelium on DCs were observed only in the absence of a pathogen-derived signals. In vivo, DCs which migrated to the draining lymph nodes upon inflammatory stimuli, but in the absence of a pathogen, showed increased levels of CD86 expression in ICAM-1-deficient mice. Together, these data demonstrate a direct role of lymphatic endothelial cells in modulation of immune response and suggest a function of lymphatic endothelium in preventing undesired immune reactions in inflammatory conditions.

Keywords: Endothelial cells, Dendritic cells, Adhesion molecules, Inflammation

INTRODUCTION

The lymphatic system plays a vital role in maintaining tissue homeostasis by regulating tissue fluid and protein balance, and by performing immunological functions (1, 2). Traditionally, the lymphatic system has not been considered actively involved in the regulation of immune responses, and has been viewed primarily as a transportation system. Lymphatic vessels serve as a route for the transport of dendritic cells (DCs), memory T cells, macrophages, and antigens from the periphery to lymph nodes, and therefore play an important role in initiating immune responses (3–6). In the steady-state, dendritic cell is the major antigen-presenting cell found in afferent lymph (5–7). During inflammation DC transit through the afferent lymphatics is increased by approximately an order of magnitude. It is well established that inflammatory mediators such as TNFα and IL-1β rapidly induce mobilization of DCs to the lymph nodes by stimulating production of chemokines and chemokine receptors which direct DC migration (2, 6, 7). Inflammatory signals also lead to remodeling of the lymphatic network at the periphery and in the lymph node. Lymphangiogenesis has been described in several inflammatory conditions and also in the draining lymph nodes following immunization (8–13). Thus, lymphatic system activation is apparently an integral part of inflammation and immunity. It is believed to aid in resolution of inflammation by removing extravasated fluids, inflammatory mediators and cells (2, 14, 15), but whether the lymphatic system has a function in the regulation of immunity and inflammation beyond its role as a transport system is poorly understood.

Dendritic cells typically acquire antigens in peripheral tissues and migrate to lymph nodes where they present them to T-cells. Exposure of DCs to danger signals such as microbial agents and inflammatory mediators induces their maturation, resulting in increased expression of MHC class II, costimulatory molecules like CD80 and CD86, and cytokines, ultimately resulting in induction of immunity (6, 16). In the absence of pathogens, immature DCs capture autoantigens from apoptotic cells, migrate to secondary lymphoid organs and trigger T cells tolerance (17–21). Immature DCs continuously traffic from peripheral tissues to lymph nodes under steady-state conditions, and it has been proposed that they play a critical role in establishing peripheral tolerance to innocuous environmental proteins and self antigens (22). The risk of autoimmunity is particularly heightened during inflammation and infection, which are associated with extensive cell death and increased flux of dendritic cells to the lymph nodes. In inflammation, it is therefore of particular importance to prevent undesired immune reactions, but the mechanisms which control the ability of DCs to suppress immune responses are poorly understood.

DCs must come into close contact with LECs as they migrate in and out of the lymphatic vessels, but little is known about direct interactions between DCs and LECs. Recent study showed that in inflammation, lymphatic vessels express several key adhesion molecules involved in transmigration of leukocytes from the blood (23), and some studies suggested that ICAM-1 may be important for DC migration to the lymph nodes (23–25). Here, we investigated the role of ICAM-1 and its β2-integrin ligands LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) and Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) (26) in mediating adhesive interactions of DCs with LECs, and demonstrate that ICAM-1-mediated contact of DCs with LECs suppresses DC maturation and their ability to stimulate T-cells in the absence of a pathogen-derived signals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

APC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD14, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR Abs, IgG1 and IgG2a isotype controls were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). APC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD86 Ab and IgG2a isotype control were purchased from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA). Mouse anti-human podoplanin used for FACS was from AngioBio (DelMar, CA). Abs used for immunostaining were: rat anti-mouse ICAM-1 (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL), anti-human ICAM-1, VCAM and E-selectin (R&D Systems, Mineapolis, MN); ICAM-2 (Biosource, Camarillo, CA); mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin FITC-conjugated (Sigma-Aldrich, St.Louis, MO) ; rabbit anti-human LYVE-1 and podoplanin (Fitzgerald Industries International, Concord, MA). Mouse anti-human antibodies used in blocking studies were: anti-ICAM-1, clone P2A4 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and clone 15.2 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); anti-LFA-1, clone TS1/22, (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) and anti-Mac-1, clone CBRM1/5 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Isotype matched control used for blocking studies was mouse IgG1 from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Cell isolation and culture

Primary cultures of human lymphatic microvascular endothelial cells (LECs) were established from neonatal foreskins and cultured on collagen-coated dishes in EBM (Clonetics, San Diego) with glutamine and 20% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), as described (27). In all experiments involving co-culture of LECs with leukocytes, hydrocortisone acetate, cAMP, penicillin, streptomycin and amphotericin B, which are supplemented for routine culture, were omitted from the media. Human monocytic cell line THP-1 and human T-cell leukemic Jurkat cells were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD) and cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad,CA) with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 1mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad,CA).

Conditioned media preparation

Confluent LECs were pre-stimulated with TNFα (1ng/ml, 24 hr) in EBM with 1%FBS, cells were washed to remove TNFα and fresh EBM/1% FBS was added. Conditioned media were collected after 24hr and filtered with 0.22µm PDVF filter (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Preparation of human DCs

Blood was obtained from healthy donors according to the guidelines approved by the IRB of Mount Sinai School of Medicine. PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and CD14+ monocytes were purified using anti-CD14 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Dendritic cells were generated by culturing CD14+ monocytes for 5 days in RPMI 1640 supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% FBS, 1mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 100ng/ml GM-CSF and 50ng/ml IL-4 (Peprotech, Rocky Hills, NJ). For DC maturation cells were treated with 100ng/ml LPS (E. coli, serotype 0111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or 50ng/ml TNFα (Peprotech), for additional 48 hr.

Adhesion to immobilized ICAM-1Fc

Flat bottom 96-well microtiter plates (MaxiSorp, Nunc, Rochester, NY) were coated with 15µg/ml recombinant human ICAM-1Fc chimeric protein (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, Minneapolis, MN, Minneapolis, MN) for 2hr at RT, washed with PBS using a microplate washer (EL404, Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VE) and incubated with 0.2% gelatin in PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ for 1hr at RT, to minimize non-specific binding. Cells were labeled with 5µM CFSE (5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinmidyl ester; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), resuspended in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+ and added to the wells at 3×104cells/well, in triplicate. To activate integrins, cells were seeded in HBSS containing 2mM EGTA and 5mM MgCl2 (28). For blocking studies, cells were preincubated with blocking antibodies to LFA-1 (10µg/ml; clone TS1/22), Mac-1 (20µg/ml; clone CBRM1/5) or mouse IgG1 (20µg/ml) for 30min on ice. After seeding, plates were centrifuged at 200g for 2min at 4°C and cells allowed to adhere for 30min at 37°C. Cell fluorescence was measured using a Synergy HT micro-plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT), before and after two washes with PBS using a microplate washer. Results were expressed as a percentage of input cells

Adhesion to LECs

LECs were grown to confluence on collagen-coated wells of 6-well plates in EBM with 20% FBS (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, San Jose, CA). Media was changed to EBM with 1% FBS, with or without 2ng/ml TNFα for 24 hr. This concentration of TNFα was chosen because it induced high levels of ICAM-1 in LECs, but did not alter cell shape, as observed at the concentrations higher than 50ng/ml. LECs were then washed 2× with HBSS and DCs labeled with CFSE seeded on top of the LEC monolayers at 3×105cells/well, in triplicate. For blocking studies, DCs were preincubated with blocking antibodies to LFA-1 (10µg/ml; clone TS1/22) (29), Mac-1 (20µg/ml; clone CBRM1/5) (30) or mouse IgG1 (20µg/ml) for 30min on ice. To block ICAM-1, LECs were preincubated with anti-ICAM-1 Ab (10µg/ml; clone P2A4 or 15.2) or mouse IgG1 (10µg/ml) for 30min before adding DCs. Cells were allowed to adhere for 30min at 37°C, non-adherent cells were gently removed with PBS with Ca2+ and Mg2+ and cell fluorescence measured using a Synergy HT micro-plate reader. Alternatively, 1.5×105 LECs were seeded onto collagen-coated 8-well slides (LabTekII, Nunc, Rochester, NY), treated as above and 2×104 CFSE-labeled DCs seeded on top in duplicates. Slides were gently washed, fixed with 1% formalin, coverslipped with 50% glycerol in PBS and examined with Nikon E-600 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY). Images were captured with a SPOT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) at 10× magnification (four images per well) and quantitative analysis performed using the IPLab software (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA).

Immunofluorescent staining of cells and tissues

Human neonatal foreskin and adult skin were collected and freshly frozen in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) or cultured ex vivo with or without 100ng/ml TNFα in EBM/1% FBS for 4 and 24hr, and then frozen. Mouse foot pad or ear was injected with FITC-conjugated latex beads or with TNFα (Peprotech, 50ng per ear, 200ng per foot pad) 20hr prior to harvesting of the skin or draining LN. Tissues were collected and freshly frozen in OCT compound. Tissues were sectioned (6µm) using a Leica CM3050S cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL) and stained as described (27, 31). For staining of cells, LECs were grown to confluence on collagen-coated 8-well slides. Media was changed to EBM/1%FBS and some wells were treated with 2ng/ml TNFα for 24 hr. Cells were stained with antibodies to human ICAM-1, -2, -3, E-selectin and podoplanin as described (27, 31). Specimens were examined with a Nikon E-600 microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY), and images were captured with a SPOT digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). For confocal analysis images were captured with Leica SP5-DMI confocal microscope at 0.118 µm interval. 3D reconstructions were performed using Volocity v4.5 software (Improvision; England).

Flow cytometry

DCs were stained with APC-conjugated antibodies against CD14, CD83, CD86, HLA-DR or with APC-conjugated appropriate isotype controls. To block unspecific binding human DCs were incubated with 20% human serum, and mouse DCs with Mouse BD Fc block (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 15 min at 4°C prior to antibody incubation. Antibodies were incubated in 0.1% BSA/PBS for 30 min at 4°C, cells were washed and fixed in 1% formalin. CFSE-labeled DCs were collected from co-cultures with LECs as described in the MLR assay, washed with cold PBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ and stained for FACS. LECs were released from the plate by mechanical scraping, centrifuged, resuspended in PBS/5% FBS and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C with primary antibodies to ICAM-1, VCAM-1 or podoplanin. Following washes, appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with Cy5 were added for 30 min at 4°C, cells were washed and fixed in 1% formalin. Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a FACScalibur (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). The expression levels were reported as the difference between median fluorescence intensity (MFI) with specific Ab minus the isotype control MFI .

β2 integrin activation analysis

Affinity modulation of LFA-1/CD11a was analyzed on DCs and Jurkat cells with the mAb AL-57 (kind gift from Drs. M. Shimaoka and T. Springer, CBR Institute for Biomedical Research, Boston, MA), which selectively binds to the active conformation of human LFA-1 (32, 33). Activation status of Mac-1/CD11b was examined using the mAb CBRM1/5 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), which reacts with an activation-specific epitope of human Mac-1 (30). Antibodies which do not distinguish between activated and non-activated forms of LFA-1 (MHM24, GeneTex Inc) and Mac-1 (ICRF44, BD Biosciences), were used to quantify total surface expression of these integrins. Human IgG1 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was used as a control. Epitope expression was examined on unstimulated cells and cells stimulated with EGTA/ Mg2+ as described (32, 33), with some modifications. Cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 2×105 cells per well. Following centrifugation, cell pellets were resuspended in 50µl activating buffer (HBSS with 5mM MgCl2 and 2mM EGTA) or control buffer (HBSS without Ca2+ and Mg2+) and incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C in presence of the antibody (AL-57, MHM24, CBRM1/5 or ICRF44, all at 20 µg/ml). After washing, cells were stained with the anti-mouse Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody, fixed with 1% formalin and analyzed by flow cytometry.

MLR assay

To assess the impact of LECs on DC functional status, DCs were co-cultured with TNFα-stimulated LECs (2ng/ml) as described above, adherent and non-adherent cells were collected, washed in cold PBS, and assayed for their ability to stimulate allogeneic T cell proliferation. Non-adherent DCs were collected from LECs after 12hr or 2hr of co-culture. To assay adherent cells, non-adherent DCs were removed after 2hr, and adherent DCs were collected after total of 12hr of co-culture with LECs with cold PBS, without Ca2+ and Mg2+. As an additional control, DCs were cultured in LEC conditioned media for 12hr, washed with cold PBS and assayed in MLR. T cells were prepared by rosetting PBMCs with neuraminidase–treated sheep red blood cells as described (34). DCs were irradiated and incubated with 1×105 allogeneic T cells at different ratios (DC/T cell 1:5–1:50) for 5 days. At day 5 cells were pulsed with 3H thymidine (1µCi/well; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), harvested after 18hr (PHD Cambridge harvester Cambridge Technologies, Cambridge, MA) and measured with β-counter (Beckman 3801, Fullerton, CA).

Real-Time PCR

The expression levels of human ICAM-1 mRNA were quantified by SYBR-Green based Real-Time PCR, using Opticon 2 Detection System (Bio Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and cDNA was generated using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad,CA). Triplicate reactions containing SYBR Green Jump Start Taq Ready Mix (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), cDNA, forward and reverse primers were amplified with 40 cycles at 94°C for 40 sec, 59°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, with fluorescent data recorded at the end of each cycle in a single step. Data were normalized based on the expression levels of β-actin in each sample. Primers used were: ICAM-1 forward 5’-TCCGTGCTGGTGACATGCCAG-3’, reverse 5-AGGCAACGGGGTCTCTATGC-3’; β-Actin forward 5’TCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTACGA-3’, reverse 5’ CAGCGGAACCGCTCATTGCCAATGG -3’.

Dendritic Cell Migration Assays

FITC-labeled latex microspheres (1 µm diameter; Polysciences) were injected into the footpads of C57BL/6 WT and ICAM-1−/− mice (purchased from Jackson Laboratories) as described (35). Two days after microsphere injection mice were sacrificed; draining lymph nodes were collected, processed and stained with anti-mouse CD86 APC-conjugated antibody (BD Biosciences) for FACS analysis. For adoptive transfer, BMDCs from C57BL/6 WT mice were prepared as described (36) and on day 8 stimulated with 100ng/ml TNFα for 24hr. At day 9, CFSE-labeled BMDCs (1×106) were injected into each side of the scapular skin of C57BL/6 WT and ICAM-1−/− mice. Two days later draining brachial LN were collected, processed, and the whole LN sample was analyzed by FACS.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using the paired Student t-test.

RESULTS

Immature DCs adhere to lymphatic endothelial cells more than mature DCs or macrophages

Antigen presenting cells (APCs) traverse lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) en route to the lymph nodes, but the nature of their interactions with the lymphatic endothelium is poorly understood. We sought to examine the ability of LECs to support adhesion of monocyte-derived APCs under steady-state and inflammatory conditions. Because lymphatic capillaries are a point of entry for APCs, we employed human LECs derived from the skin microvasculature (27). These cells have been characterized previously and have been shown to express LYVE-1, Prox-1 and podoplanin, typical markers of lymphatic endothelial lineage, and to respond to the lymphangiogenic growth factor VEGF-C by increased growth and tube formation in vitro. Under steady-state conditions, imDCs generated from CD14+ human monocytes adhered to LECs to a moderate extent (Fig. 1). Adhesion was markedly increased upon stimulation of LECs with TNFα (32% vs. 79% adherent cells). In contrast, LPS-matured DCs showed very little adhesion to LECs under basal conditions (4.2% adherent cells), and although TNFα slightly increased binding (6.9% adherent cells), the overall adhesion levels were much lower in comparison with imDCs (Fig. 1). To exclude the possibility that the increase in adhesion was due to direct effects of TNFα on DCs, we compared binding of imDCs to TNFα-activated LECs in the presence or absence of TNFα in the media. As shown in Fig. 1H, presence of TNFα in the media did not change the number of adherent cells, indicating that TNFα promoted adhesion of DCs by altering adhesive properties of LECs. Activated macrophages generated from monocytes with INFγ and LPS (37) were even less adhesive than mDCs, whereas PBMCs exhibited higher levels of adhesion to TNFα/LECs than imDCs (data not shown). These results indicate selectivity in the ability of lymphatic endothelial cells to support adhesion of different monocyte-derived cell subsets.

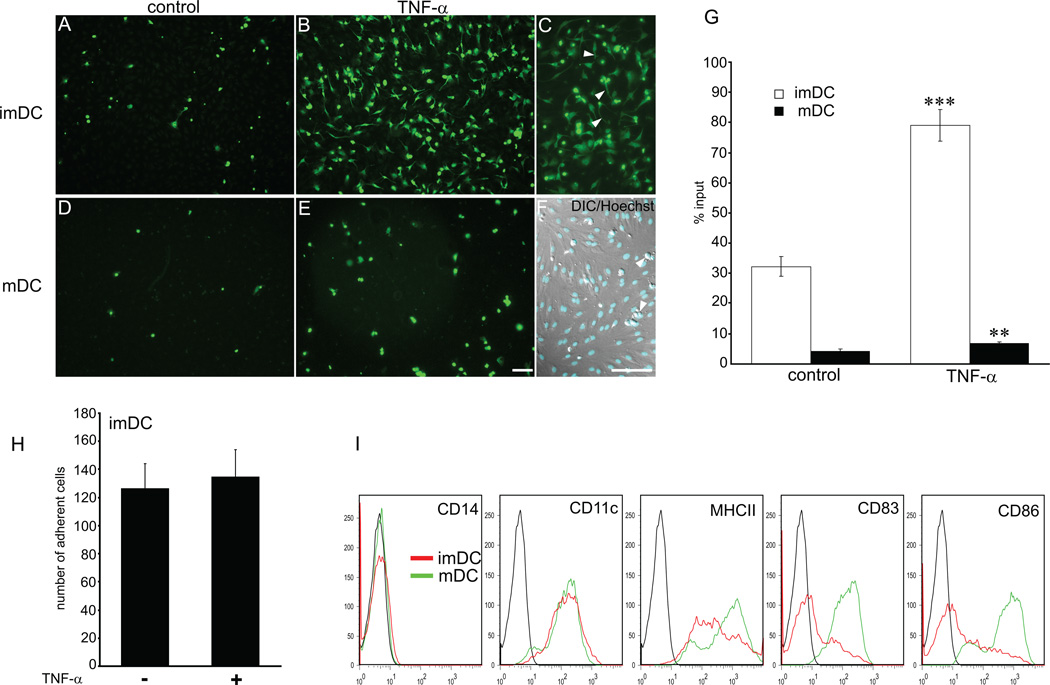

Figure 1. DC adhesion to lymphatic endothelial cells is increased with TNFα.

Adhesion of imDC and LPS/mDC to control (A, D) and TNFα treated LECs (B–F) was examined in a static adhesion assay. imDCs showed higher affinity for LEC in steady-state (A) and in inflammatory condition (B) than mDC (D and E). Upon contact with TNF-α/LEC (1ng/ml, 24 hr) imDCs changed phenotype from round to dendritic (B, C). (C) Arrowheads point to protrusions. In contrast, mDCs did not change morphology upon contact with TNF-α/LECs (E). (F) Nuclear staining with Hoechst overlaid on Nomarsky image shows DCs (arrowheads) adhering to confluent LEC. (Bar = 100 µm). (G) DC adhesion was quantified by FACS and expressed as percentage of input cells. (H) Binding of imDCs to TNF-α/LECs in presence or absence of TNFα in the media. Note no difference in the adhesion levels. (I) Phenotype of DCs employed in the adhesion assays was determined by FACS just before the experiment. Data shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined with Student’s t-test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Interestingly, upon prolonged contact with TNFα-activated LECs (14hr) morphology of immature DCs was dramatically altered (compare Fig. 1A and B). At early timepoints, 30min-1hr, imDCs which bound to LECs were rounded with very few, thin projections. After 14hr of direct contact with TNFα-activated LECs, but in the absence of TNFα in the media, imDC cell shape changed from round to elongated with many projections, assuming a dendritic appearance (Fig. 1B and C). In contrast, the appearance of imDCs bound to control, unstimulated LECs did not change upon extended contact. After 14hr of adhesion to control LECs imDCs remained rounded and the number of cells adhering was lower than after 1hr. Together, these data demonstrate that TNFα-activated LECs strongly support adhesion of imDCs and affect their phenotypic characteristics.

Lymphatic endothelial cells express high levels of ICAM-1 upon TNFα stimulation

To investigate the mechanism of DC adhesion to lymphatic endothelium, we next analyzed expression of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) which mediate leukocyte adhesion to blood endothelium, in the skin lymphatic vasculature. TNFα stimulation of human skin explants (adult skin and foreskin) strongly induced ICAM-1 expression in lymphatic vessels 24hr after treatment, as determined by immunostaining (Suppl. Fig. 1). Low levels of ICAM-1 protein were detected at 4hr in a subset of small lymphatic vessels, whereas at 24hr, many small and large lymphatic vessels, strongly expressed ICAM-1. The pattern of ICAM-1 expression on a single lymphatic vessel was heterogenous, as reported previously for the blood vasculature (38). Lymphatic vasculature in control, untreated skin, was consistently devoid of ICAM-1 expression. In contrast, ICAM-1 was constitutively expressed by a subset of blood vessels, and its expression was further increased with TNFα, in accordance with previous reports (38). Similar pattern of ICAM-1 expression was observed on lymphatic vessels in mouse skin upon injection of TNFα (Suppl. Fig. 2). ICAM-2 and ICAM-3 were not expressed by lymphatic vessels under the conditions examined. Likewise, E-selectin, which is strongly induced with TNFα at 4hr in the skin blood vessels, was not expressed by the lymphatic vasculature (data not shown).

This pattern of CAM expression was recapitulated in primary cultures and early passage lymphatic endothelial cells in vitro. ICAM-1 was most robustly expressed CAM in LECs treated with TNFα, while ICAM-2, ICAM-3 and E-selectin were not expressed (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Immunostaining of TNFα-treated cultured LECs revealed high levels of ICAM-1 expression, which was barely detectable on unstimulated cells (Fig. 2A–D). Kinetic studies with real-time qPCR demonstrated onset of ICAM-1 expression at 2 hr and maximum expression at 12 hr, followed by a sharp decline 48hr later (Fig. 2E and F). FACS analysis showed that surface expression of ICAM-1 was highly inducible in LECs, and that ICAM-1 expression levels were much higher than those of VCAM (Fig. 2G). It is important to note that upon prolonged culture LECs begun to express low levels of ICAM-1, ICAM-2 and E-selectin (Fig. 2G and data not shown), which was apparently a tissue culture artefact, as this was never observed on lymphatic capillaries in vivo. In summary, these results demonstrate that ICAM-1 is a highly expressed inducible adhesion molecule on lymphatic endothelial cells.

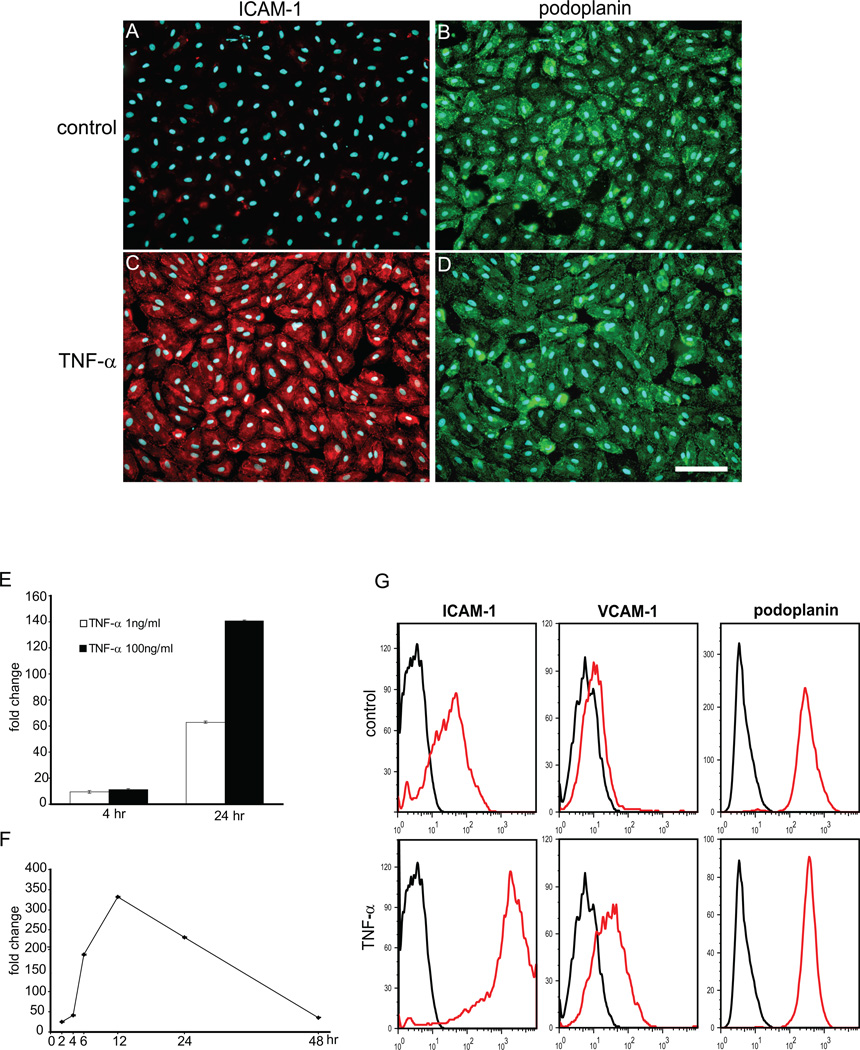

Figure 2. Expression of ICAM-1 on LECs in vitro.

(A–D) LECs were cultured in presence or absence of TNF-α (2 ng/ml) and expression of ICAM-1(red) and podoplanin (green) was examined by double immunofluorescent staining. Note high expression levels of ICAM-1 on TNF-α/LECs (C), but not on control cells (A). Podoplanin expression was uniform in both conditions (B, D). (E, F) qRT-PCR showing dose-response (E) and time-course (F) of ICAM-1 mRNA expression in TNF-α/LECs. For the time-course, TNF-α was added at 1ng/ml. (G) Surface expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM on control and TNF-α-treated LECs was analyzed by FACS. Data shown are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Adhesion of imDCs to ICAM-1 is mediated by Mac-1

To examine whether ICAM-1 may mediate adhesion of imDCs to LECs, we next investigated the ability of imDCs to adhere to recombinant ICAM-1-Fc immobilized on a plate. ImDCs adhered to immobilized ICAM-1-Fc to a much greater extent than mDCs (3.8-fold increase), which exhibited minimal binding (Fig. 3). Activation with Mg2+/EGTA significantly increased adhesiveness of both mature and immature DCs. For comparison, adhesion levels of non-activated imDCs were comparable to that of Jurkat cells, whereas adhesion of Mg2+/EGTA activated imDCs was lower than the adhesion of activated Jurkat cells and THP-1 cells (Fig. 3A). Binding of imDCs to ICAM-1-Fc was also greatly augmented by stimulation with phorbol myristoyl acetate (PMA) or Mn2+, and the combination of PMA and Mg2+/EGTA showed additive effects (data not shown). Nevertheless, adhesion of imDCs to recombinant ICAM-1 was much greater than the adhesion of mDCs in all conditions tested, consistent with the data showing higher levels of adhesion of imDCs to LECs. These data demonstrate that ICAM-1 is a ligand for integrins expressed by imDCs.

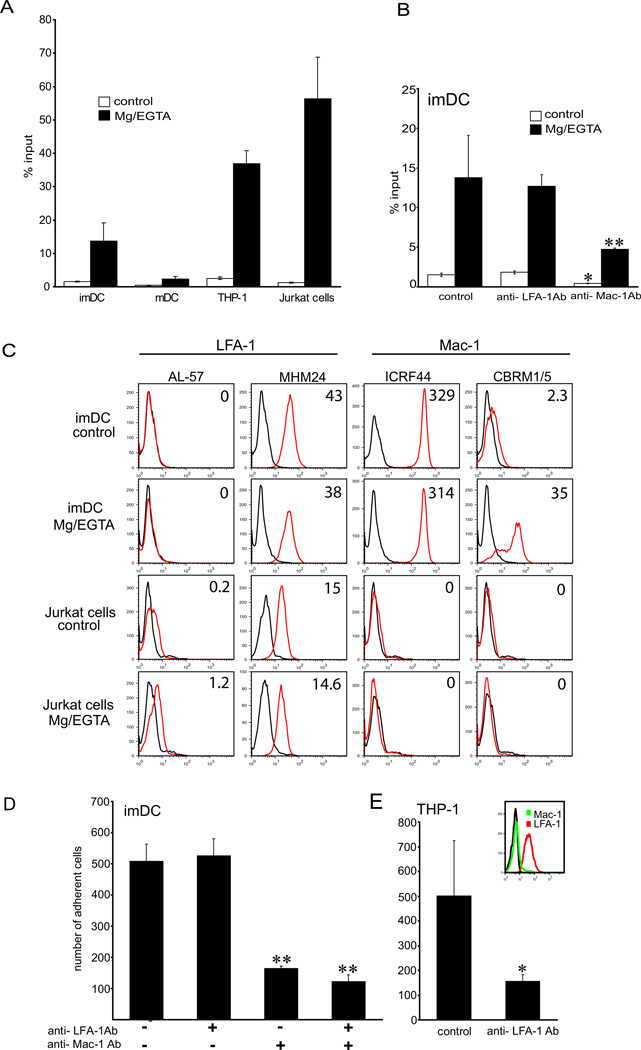

Figure 3. imDCs bind ICAM-1 via Mac-1.

(A) Cell adhesion to ICAM-1Fc immobilized on the plate with and without Mg2+/EGTA stimulation. Note that imDCs adhere to ICAM-1 more than LPS/mDCs. (B) imDCs were preincubated with blocking antibodies to LFA-1 or Mac-1 and assayed for adhesion to ICAM-1Fc (20µg/ml). Binding of control and Mg2+/EGTA-activated imDCs is inhibited by blocking Mac-1, but not LFA-1. Data shown are representative of 3 experiments, performed in triplicates. (C) To examine the activation state of β2 integrins on imDCs, cells were incubated with antibodies recognizing active conformation of LFA-1 (AL-57 Ab) or Mac-1 (CBRM1/5 Ab) or control antibodies (MHM24 and ICRF44, respectively), and analyzed by FACS. Jurkat cells were used as a positive control for LFA-1 activation and negative control for Mac-1. Data are expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), and are representative of 2 independent experiments. (D) Adhesion of imDCs to TNFα-treated LECs preblocked with function-blocking antibodies to LFA-1 and Mac-1. Note that Mac-1 Ab inhibits adhesion of imDCs, but LFA-1 Ab does not. Adhesion of THP-1 cells, which express activated LFA-1, but not Mac-1 was inhibited when blocking LFA-1 (E). Data shown are representative of 3 experiments, performed in triplicates. Appropriate isotype controls were used in all experiments (see Methods). Statistical significance was determined with Student’s t-test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Next, we investigated the relative contribution of β2 integrin receptors LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) and Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) for binding of imDCs to ICAM-1. A function-blocking antibody to LFA-1 (29) did not influence binding of imDCs to ICAM-1, regardless of the DC activation status (Fig. 3B), although it potently inhibited adhesion of PMA-activated Jurkat cells (data not shown). FACS analysis showed that LFA-1 was expressed constitutively and at high levels by imDCs (Fig. 3C). However, labeling with the mAb AL-57, which specifically recognizes the active high-affinity conformation of the LFA-1 domain (32, 33), revealed that on imDCs LFA-1 was present in the latent form. Affinity upregulation was not observed upon stimulation with Mg2+/EGTA (Fig. 3C), or when imDCs were cultured in LEC-conditioned media, in presence or in the absence of TNF-α (data not shown). Jurkat cells served as a positive control, and as expected, demonstrated increase in LFA-1 affinity upon stimulation with Mg2+/EGTA.

In contrast, a function blocking antibody to Mac-1 (30) strongly diminished adhesion of imDCs to ICAM-1-Fc, both in the presence and in the absence of Mg2+ (Fig. 3B). We then used an activation-dependent mAb to the Mac-1 I domain, CBRM1/5 (30), to characterize the affinity state of Mac-1 on imDCs. Indeed, high-affinity conformation of Mac-1 was detected on steady-state imDCs by FACS, in accordance with the function-blocking data. Mac-1 affinity was further enhanced with Mg2+/EGTA (Fig. 3C) and PMA, whereas LEC-conditioned media and TNF-α had no effect (data not shown). These results demonstrate that Mac-1 on imDCs is the main ligand for ICAM-1, and thus explain the lack of efficacy of the LFA-1 blocking antibody in inhibiting adhesion of imDCs to ICAM-1.

Because ICAM-1 was highly expressed by TNFα-activated LECs, we next asked whether Mac-1 also mediates binding of imDCs to the inflamed LECs. Function-blocking studies with antibodies to Mac-1 and LFA-1 showed that Mac-1 was indeed a major integrin mediating adhesion of imDCs to LECs. Blocking Mac-1 decreased the adhesion by 68%, whereas anti-LFA-1 antibody did not have any effect (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, combination of anti-Mac-1 and anti-LFA-1 antibodies did not decrease adhesion of imDCs more than blocking of the Mac-1 alone (Fig. 3D). However, when THP-1 cells which express high levels of LFA-1 and no Mac-1 were employed in the experiment, treatment with the anti-LFA-1 antibody resulted in the expected decrease of adhesion to LECs, confirming the efficacy of the anti-LFA-1 blocking antibody (Fig. 3E). In addition, blocking ICAM-1 on LECs decreased adhesion of imDCs to TNFα-activated LECs to a comparable extent as blocking Mac-1 (Suppl. Fig.3), indicating that Mac-1 is a ligand for ICAM-1 on LECs.

Contact of imDCs with LECs impairs their ability to activate T-cells

To examine whether interactions between DCs and LECs have functional implications, we next investigated the capacity of DCs co-cultured with lymphatic endothelium to stimulate proliferation of allogeneic T-cells. DCs were cultured on top of the confluent lymphatic endothelial monolayer which was pre-treated with TNFα, and the adherent as well as non-adherent cells were assayed in MLR. Co-culture of LPS-matured DCs (LPS/DC) with LECs did not affect their ability to activate T-cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, the extent of T-cell proliferation was not significantly different between the control, adherent and non-adherent LPS/DCs. Furthermore, LPS/DCs cultured in the LEC-conditioned media were equally effective in activating T-cells as the non-adherent LPS/DCs. However, we found that when immature DCs were co-incubated with LECs, their ability to stimulate T-cells was significantly impaired (Fig. 4B). We excluded any potential direct effects of LECs on T-cell proliferation, as LECs alone did not exhibit any effects on T-cells in MLR assay (Suppl. Fig. 4A). Importantly, the effect of LECs on imDCs was dependent on the direct cell contact, because LEC-conditoned media did not inhibit the capacity of imDCs to activate T-cells. Non-adherent imDCs and imDCs incubated in the LEC-conditioned media exhibited comparable effects (Fig. 4B), indicating that the soluble factors produced by LECs were not responsible for the inhibition. Thus, we conclude that the direct contact between imDCs and inflamed LECs is essential for restricting the ability of imDCs to stimulate proliferation of T-cells.

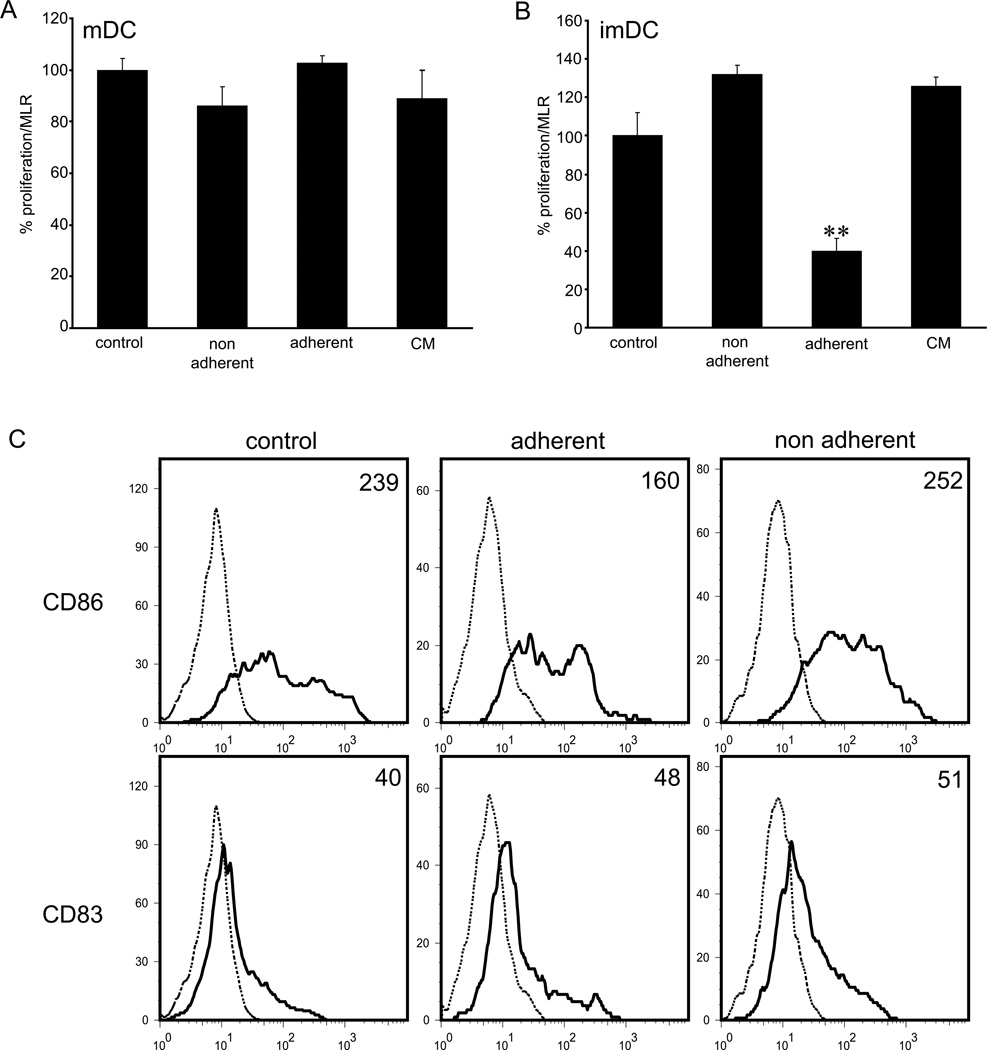

Figure 4. Adhesion of imDCs to TNFα-stimulated LECs suppresses T-cell proliferation.

(A, B) LPS/mDCs or imDCs were co-cultured with TNFα/LECs, equal numbers of non-adherent and adherent cells were collected and assayed in MLR. DCs maintained in the culture media or in the LEC-conditioned media (CM) were used as controls. Note significant reduction of T-cell proliferation only when adherent imDCs were employed in the assay. Data shown represent the 1:10 ratio of DCs to T-cells. (C) FACS analysis of imDCs for surface expression of CD83 and CD86 prior to MLR shows reduced expression of CD86. Data are expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined with Student’s t-test. **P<0.01.

Functional impairment of immature DCs was accompanied with the change in expression of the costimulatory molecule CD86. FACS analysis of CFSE-labeled DCs following co-culture with LECs showed that the surface expression of CD86 was reduced following adhesion of imDCs to activated LECs (Fig. 4C, Suppl. Fig. 4B). In contrast, CD86 expression did not change on non-adherent cells, and was comparable to that of control DCs, indicating that the soluble factors produced by LECs are not responsible for the observed change of phenotype. Expression of the maturation marker CD83 was not altered upon co-culture of imDCs with LECs under the conditions tested (Fig. 4C). Hence, these findings indicate that TNFα-activated LECs selectively instruct immature DCs to downregulate CD86 expression and impair their ability to stimulate T-cells.

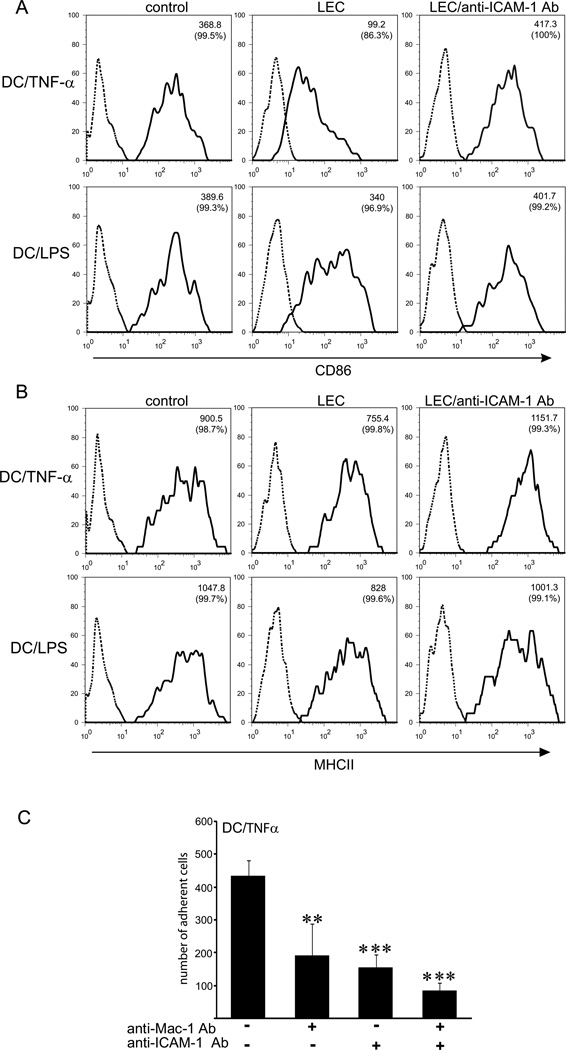

Effects of LECs on DC maturation are dependent on ICAM-1 and the presence of pathogen-derived signals

In addition to their role in inducing immune responses, DCs have been more recently shown to play an important role in maintaining peripheral tolerance in the steady-state (17–19, 22). Our data showing that TNFα-stimulated LECs suppress maturation and co-stimulatory activity of imDCs led us to hypothesize that interactions of DCs with the lymphatic endothelium during the course of an inflammatory response represent a mechanism for preventing undesired immune reactions. Because in inflammation not only LECs but also DCs will be exposed to inflammatory cytokines, we next asked the question whether LECs can exert suppresive effects on DCs exposed to TNFα (TNFα/DCs). To address this, monocyte-derived DCs were matured with TNFα, allowed to adhere to TNFα-activated LECs overnight, and the expression levels of the DC maturation markers CD86 and MHCII were determined by FACS (Fig. 5). Contact with LECs dramatically decreased surface expression of CD86 on TNFα-matured DCs (Fig. 5A). Downregulation of CD86 was ICAM-1-dependent, because pre-incubation of LECs with the blocking antibody to ICAM-1 completely abrogated this effect. In contrast, when LPS-matured DCs were co-cultured with activated LECs, CD86 expression was diminished only marginally (Fig. 5A). The minor decrease in CD86 expression, however, was also dependent on ICAM-1-mediated adhesion to LECs, as blocking antibody to ICAM-1 abolished this effect. In addition, inhibition of ICAM-1-mediated adhesion to LECs increased surface expression of CD83 by TNFα/DCs, but when DCs matured with LPS were employed, CD83 expression was not significantly altered (data not shown). MHCII expression on both TNFα/DCs and LPS/DCs was slightly lowered upon adhesion to LECs, and this effect was abrogated when adhesion was blocked with the anti-ICAM-1 blocking antibody (Fig. 5B). Blocking ICAM-1 or Mac-1 decreased adhesion of TNF/DCs to LECs to a comparable extent, and the effects of blocking Mac-1 and ICAM-1 together were less than additive, indicating that Mac-1 mediates binding to ICAM-1 on LECs (Fig. 5C). In summary, these data demonstrate that the suppressive effects of LECs on DCs are independent of the DC maturation status, but instead depend on the presence or absence of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).

Figure 5. Interaction of TNFα-matured DCs with ICAM-1 expressed by LECs decreases expression of CD86 in the absence of antigen.

(A, B) Dendritic cells matured with LPS (DC/LPS) or with TNFα (DC/TNFα) were co-cultured for 12hr with TNFα/LECs or TNFα/LECs preincubated with the anti-ICAM-1 blocking antibody. DCs incubated in the same culture media for 12hr were used as a control. All DCs from co-cultures (adherent and non-adherent) were analyzed by FACS. (A) Histograms show that CD86 is downregulated on DC/TNFα upon contact with LECs, but not on DC/LPS. This effect was reversed by adding a blocking antibody to ICAM-1. (B) MHCII expression on DC/TNFα or DC/LPS in co-cultures with TNFα/LECs. Note modest change of MHCII expression, when compared to CD86. Data are expressed as a mean fluorescence intensity (MFI); percentage of positive cells is indicated in brackets. (C) Adhesion of DC/TNFα to TNFα-treated LECs preblocked with function-blocking antibodies to ICAM-1, Mac-1 or both. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined with Student’s t-test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

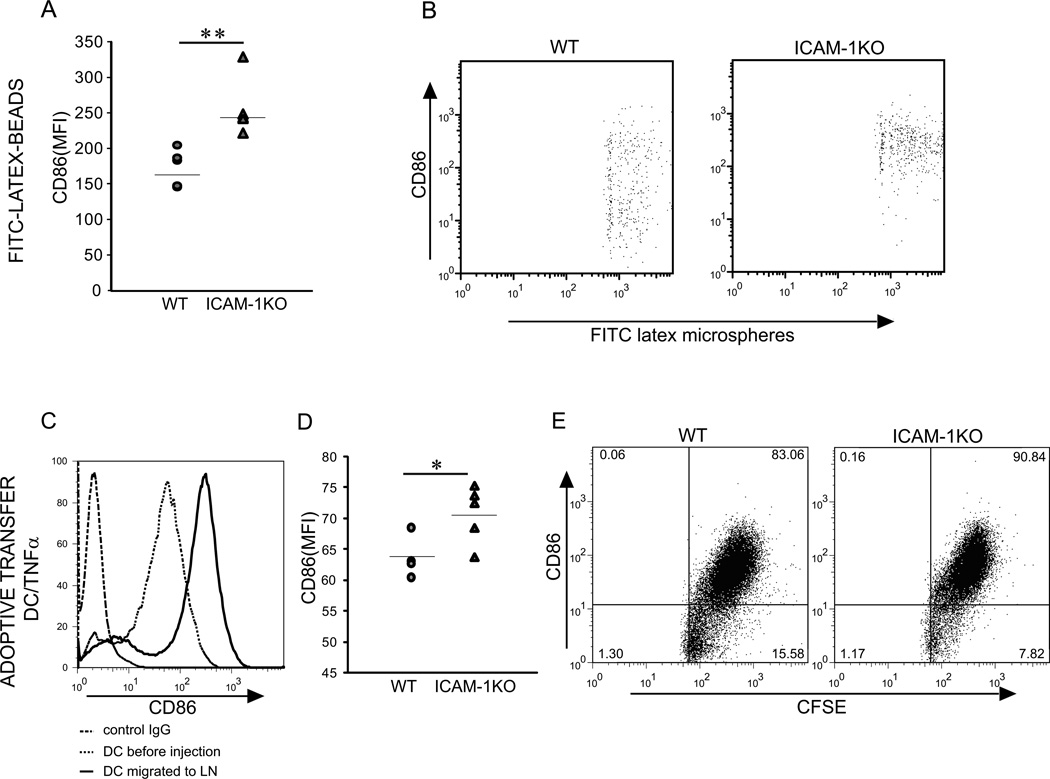

ICAM-1 deficiency correlates with increased DC maturation in vivo

To determine whether ICAM-1 influences the maturation status of DCs as they migrate to the lymph nodes in vivo, we employed ICAM-1 KO mice (39). Latex beads were injected into the mouse footpads and migration of monocyte-derived DCs into the lymph nodes traced two days later, to remain consistent with our in vitro model which employed monocyte-derived DCs. Number of migrated DCs was not significantly different between the WT and ICAM-1 deficient mice (data not shown). However, FACS analysis showed that the expression of CD86 was increased on DCs which migrated in ICAM-1 KO mice upon injection of FITC-Latex beads, as compared to WT mice (Fig. 6Aand B). To examine the effects of ICAM-1 deficiency selectively by host cells, and to exclude direct effects of ICAM-1-deficiency on DC maturation, we performed adoptive transfer of bone marrow-derived WT DCs into the ICAM-1 KO mice (Fig. 6C–E). BM-derived TNFα-matured DCs downregulated CD86 expression upon migration to the lymph nodes in WT mice (Figure 6C). Furthermore, TNF/DCs which migrated to the lymph nodes in ICAM-1-deficient mice showed higher levels of CD86 surface expression compared to TNF/DCs which migrated in wild type mice (Figure 6D, E). These results further indicate a role for ICAM-1 in DC maturation, and are consistent with our in vitro data showing that the suppression of DC maturation status by LECs is ICAM-1-dependent.

Figure 6. The effect of ICAM-1 deficiency on CD86 expression by DCs migrated into regional lymph nodes.

(A, B) FITC-latex microspheres were injected into the footpads of WT and ICAM-1 KO mice (n=5). After 2 days draining LNs were collected (3 per mouse), pooled and phenotype of migrated DCs with beads was analyzed by FACS. (A) Quantitative comparison of CD86 surface expression by migrated DCs. (B) Representative plots depicting entire population of microsphere-bearing cells recovered from the lymph nodes. (C–E) Adoptive transfer of bone marrow-derived TNFα-matured DCs into the back skin of WT and ICAM-1 KO mice (n=5). (C) FACS analysis of CD86 expression on DCs immediately before injection and on DCs which migrated into the LNs of WT mice. (D) Comparison of CD86 surface expression on migrated DCs in WT and ICAM-1 KO mice. (E) Representative plots depicting entire population of CFSE-labeled DCs recovered from the lymph nodes. Data shown are representative of at least 2 experiments. Statistical significance was determined with Student’s t-test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

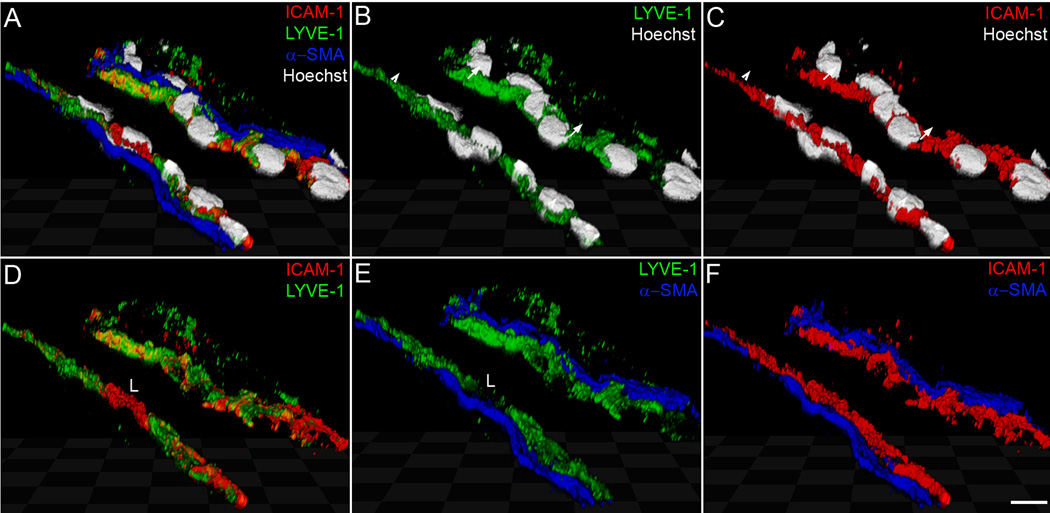

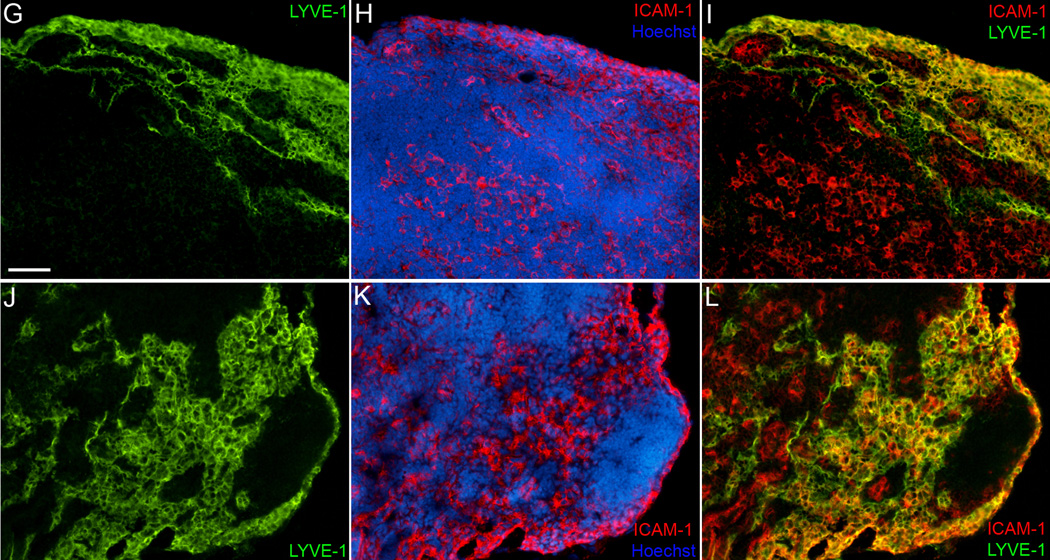

Lymph node sinuses and collecting lymphatics are major sites of ICAM-1 expression

En route to the lymph nodes, DCs could interact with the endothelium of lymphatic capillaries, collecting vessels and lymphatic sinuses. We examined the pattern of ICAM-1 expression within the lymphatic system to define the most likely site of DC interaction with ICAM-1. Upon inflammation, ICAM-1 was strongly upregulated on collecting lymphatics leading to the mouse lymph node (Fig. 7) and on collecting vessels in the cremaster muscle (not shown). Confocal analysis demonstrated ICAM-1 expression on the apical and on the basal side of the collecting vessels (Fig. 7A–F). Furthermore, ICAM-1 was highly expressed on lymph node lymphatic sinuses (Fig. 7G–L). Surprisingly, lymph node sinuses expressed ICAM-1 already in a steady-state, and the expression was further increased upon TNFα or Latex beads injection. This pattern of expression was very different from that observed in lymphatic capillaries, which were negative for ICAM-1 in a steady-state and showed a partial expression upon TNFα treatment of mouse and human skin (Suppl. Fig. 1 and 2). These data suggest that the main site of DC interaction with ICAM-1 on LECs are collecting vessels and lymph node sinuses.

Figure 7. Expression of ICAM-1 on collecting lymphatic vessels and on lymphatic sinuses in mouse lymph node.

(A–F) Confocal analysis of ICAM-1 localization on lymphatic endothelium of a collecting vessel 20 hr after injection of Latex beads into the mouse footpad. Triple immunofluorescent staining for LYVE-1 (green), ICAM-1 (red) and α-SMA (blue) shows expression of ICAM-1 on the apical (luminal) side of the vessel (arrows) and on the basal side of the endothelium (arrowheads). (G–L) Double immunofluorescent staining for LYVE-1 (green) and ICAM-1 (red) of control lymph nodes (G–I) and lymph nodes drainig footpad 20 hr after injection of 200 ng TNFα (J–L) Cell nuclei are counterstained with Hoechst (grey in A–C; blue in H, K). L designates a leukocyte expressing ICAM-1, but not LYVE-1. Scale bars: A–F: 7.5 µm; G–L: 50 µm.

DISCUSSION

The lymphatic system is critical for generating efficient immune responses by serving as a conduit for DC traffic from the periphery to the lymph nodes (1, 6).The lymphatic system also plays an important role in dampening inflammation by removing extravasated fluids, inflammatory mediators and cells from tissues. Traditionally, lymphatics have been assigned a passive role in performing these functions, and have been viewed primarily as a transportation system. Here, we demonstrate an active role of lymphatic endothelium in modulation of immune response. Our findings show that the direct contact of DCs with the inflamed lymphatic endothelium results in the downregulation of the maturation marker CD86 on DCs and the reduction of the DC ability to stimulate T-cell proliferation. These effects were dependent on adhesive interactions between DCs and LECs, which were mediated by binding of Mac-1 on DCs to ICAM-1 on LECs.

By employing co-cultures with human primary LECs (27), we found that immature DCs and DCs exposed to TNFα (TNF/DC) were significantly more adhesive to LECs than LPS-matured DCs (LPS/DC) and macrophages. This was observed in normal and in inflammatory conditions, and indicated selectivity of LECs in their ability to support adhesion of different monocyte-derived cell subsets. Only DC subtypes which were highly adhesive to LECs were instructed to down-regulate CD86 expression. These findings identify for the first time lymphatic endothelium as a source of signals which regulate DC maturation and aid in shaping the emerging concept that tissue microenvironment plays an important role in the regulation of DC function not only by presenting soluble stimuli, but also via direct cell contact. Previously, intestinal epithelial cells were shown to inhibit DC maturation upon contact, resulting in DCs with poor T-cell stimulatory capacity (40). Ligation of E-cadherin on immature Langerhans cells inhibited their maturation (41) and it was recently demonstrated that the disruption of E-cadherin-mediated adhesion leads to generation of tolerogenic DCs (42). These data suggest that the peripheral tissues, such as skin and intestine, which face continuous environmental provocation and are therefore particularly prone to aberrant immune system activation, share similar cell contact-dependent regulatory mechanisms controlling maturation of DCs.

We demonstrated that the suppression of DC maturation by LECs was ICAM-1-dependent, by using function-blocking antibodies. In contrast, ICAM-1 expressed by dermal fibroblasts was shown to promote DC maturation and their ability to activate T cells (43). Similarly, ICAM-1-mediated interaction of DCs with bronchial epithelial cells was shown to induce DC maturation, although it did not alter their capacity to activate T-cells (44). Together, these data underscore the importance of ICAM-1 signaling beyond its traditional role as an adhesion molecule involved in leukocyte trafficking, and indicate the significance of the cellular and tissue context of ICAM-1 in determining its function. The ability of ICAM-1 to mediate such opposite functions could also be explained by its binding to different ligands on DCs, such as CD11a, CD11b or CD11c. The exact mechanism by which binding of DCs to ICAM-1 modulate DC functional status remains to be investigated. Ligation of ICAM-1 could initiate signaling events which lead to the production of immunomodulatory cytokines by LECs. For example, IL-10 has been implicated in the suppression of DC maturation and function (45, 46). IL-6 plays a major role in maintaining immature, functionally impaired DCs, and its expression can be upregulated by TNFα (47, 48). Growth factors such as VEGF can inhibit functional maturation of DCs (49) and we have shown previously that VEGF is indeed expressed by LECs (27). Because LEC-conditioned media did not suppress DC maturation, indicating that soluble factors were not involved, these inhibitory signals must remain bound to the cell surface. Regulatory cytokines may also be induced in LECs by TNFα. In this case, adhesion to ICAM-1 may regulate bioavailablity of the cytokine, allowing for its presentation to DCs only when DCs are in close proximity to LECs, i.e. adherent to ICAM-1. Another intriguing possibility is that the adhesion to ICAM-1 leads to downregulation of the maturation signals produced by LECs. It has been shown recently that chemokines CCL19 and CCL21, which are produced by LECs in normal conditions, promote DC maturation (50). Downregulation of such signals in LECs upon contact with DCs may halt DC maturation.

We report here that Mac-1 on DCs was the main ligand for ICAM-1, as blocking LFA-1 did not diminish DC adhesion to LECs. Adhesion could also be partially mediated by CD11c (αxβ2) on DCs, which has been reported to bind ICAM-1 (51), although physiological relevance of this interaction remains unclear. Expression of Mac-1 by DCs was reported previously (52, 53) and its function has been related to the phagocytic properties of immature DCs. Mac-1 (CD11b/CR3) was shown to play a role in complement-mediated phagocytosis of bacteria and apoptotic cells (54–56). Our data showing that Mac-1 is involved in regulating functional status of DCs by ligating ICAM-1 on LECs demonstrate a novel function for Mac-1 on DCs. Mac-1 ligation could directly impact cytokine production by DCs. In support of this idea is the data showing that crosslinking of Mac-1 on DCs suppressed production of inflammatory cytokines (55). Recent reports indicate a function of Mac-1 in preventing immune activation upon binding to several different ligands in the absence of PAMPs. Ligation of Mac-1 to complement C3 fragment iC3b mediated peripheral tolerance to self-antigens (57) and Mac-1 rendered DCs tolerogenic upon capture of apoptotic cells (56). It was also reported that upon activation with divalent cations, Mac-1 on DCs can directly inhibit T-cell activation (58). These data are consistent with our model showing that Mac-1/ICAM-1 interaction results in immunosuppression.

ICAM-1–Mac-1 interaction may occur as DCs enter lymphatic capillaries at the tissue periphery, travel within the lymphatic system or as they exit lymphatic sinuses in the lymph nodes. We show that ICAM-1 is upregulated by lymphatic capillaries in inflammation, in accordance with the data by Johnson et al.(23). In addition, we demonstrate that lymph node sinuses and collecting lymphatics are major sites of ICAM-1 expression, suggesting that DCs may interact with ICAM-1 on LECs upon their arrival to the lymph node. In further support of this concept, our data shows ICAM-1 expression on luminal and on basolateral side of lymphatic endothelium of the collecting vessels. This pattern of ICAM-1 expression has also been reported on capillary LECs in vitro (23) and on IL-1-stimulated HUVECs (59), and it has been proposed to contribute to bidirectional movement of immune cells across endothelium(60). While some studies suggested that ICAM-1 is involved in DC migration to the lymph nodes (23–25), others reported that β2 integrin-mediated adhesion is not required (61). In agreement with the latter, our data did not show reduced rate of DC migration to the lymph nodes in ICAM-1 KO mice, suggesting that the effects of ICAM-1-mediated DC adhesion to lymphatics are not necessarily linked to migration. The discrepancy of these findings could be explained by the difference in the subset of DCs employed in the experiments. Whereas we employed immature and semi-mature TNFα/DCs, others employed mature DCs exposed to antigen in their studies (23, 24).

Interestingly, the effects of lymphatic endothelium on DCs were observed only in the absence of PAMPs (LPS), suggesting that TLR activation renders DCs unresponsive to the signals from LECs. Alternatively, because LPS/DCs adhered to LECs to a much lesser extent than imDCs or TNF/DCs, it is conceivable that by escaping close contact with LECs, LPS/DCs avoid inhibitory signals produced by LECs. These data suggest that signals induced by LPS in DCs override regulation by LECs because in the presence of a pathogen full immunogenic potential is required, and therefore downregulation of DC maturation is not desirable. It has been recognized more recently that during steady-state, upon capturing self-antigens, imDCs constitutively migrate to the lymph nodes where they induce and maintain peripheral tolerance (17, 18, 20–22). Migration of DCs into draining lymph nodes is greatly increased during inflammation (2, 3, 6) and in this condition DCs can be exposed to pro-inflammatory cytokines in the absence of a pathogen. Semi-maturation induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines alone seems to represent a unique developmental, tolerogenic stage for DCs, which is characterized by the absence of pro-inflammatory cytokine production despite high expression of MHCII and co-stimulatory molecules (62, 63). In inflammatory conditions, DCs carrying self and environmental antigens are exposed to inflammatory stimuli while migrating to the lymph nodes, what could result in their maturation and consequently immune response to self-antigens or non-dangerous environmental antigens. Hence, this condition would pose a risk for induction of autoimmunity. We found that both, imDCs and TNF/DCs were responsive to signals from TNFα-stimulated LECs which lead to suppression of maturation. Based on our results, we propose that the interactions of DCs with the lymphatic endothelium during the course of an inflammatory response might represent one of the control mechanisms for preventing undesired immune response. In addition to the phenotypic characteristics, functional status of DCs is determined by their capacity to produce cytokines (62, 64). While we show that LECs down-regulate CD86 on DCs and reduce their capacity to stimulate T-cells, exact functional characteristics of DCs following contact with LECs remain to be defined (endocytosis, chemokine receptors, antigen processing activity, cytokine production).

In conclusion, we demonstrate for the first time that lymphatic endothelium modulates differentiation and function of DCs through direct cell to cell contact. Our results challenge the dogma about the lymphatic system as a passive conduit for immune cells and present the first evidence for direct control of immune function by lymphatic endothelium. Further characterization of interactions between lymphatics and DCs should lead to better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms which influence functional status of DCs, and could therefore impact different areas, such as strategies for vaccine development, transplantation outcome, treatment of autoimmunity, inflammation and cancer.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Michael L. Dustin (New York University) for helpful discussions and Dr. Timoty Springer (Harvard Medical School) for providing the AL-57 antibody. We also thank Drs. Veronique Angeli, Theodore J. Kaplan and Dr. Ana Fernandez-Sesma (Mount Sinai School of Medicine) for help with DC isolation and culture.

This work was supported by the Emerald Foundation (M.S.) and by the DOD grant BC044819 (M.S.).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed at the MSSM-Microscopy Shared Resource Facility, supported with funding from NIH-NCI shared resources grant (5R24 CA095823-04), NSF Major Research Instrumentation grant (DBI-9724504) and NIH shared instrumentation grant (1 S10 RR0 9145-01).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- DC

dendritic cells

- BMDC

bone marrow-derived dendritic cell

- LEC

lymphatic endothelial cells

- LN

lymph node

- WT

wild type

- KO

knockout

- αSMA

α-smooth muscle actin

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental material

References

- 1.Pepper MS, Skobe M. Lymphatic endothelium: morphological, molecular and functional properties. J.Cell Biol. 2003;163:209–213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angeli V, Randolph GJ. Inflammation, lymphatic function, and dendritic cell migration. Lymphat Res Biol. 2006;4:217–228. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2006.4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olszewski WL. The innate reaction of the human skin lymphatic system to foreign and self-antigens. Lymphat Res Biol. 2005;3:50–57. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2005.3.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugh CW, MacPherson GG, Steer HW. Characterization of nonlymphoid cells derived from rat peripheral lymph. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1758–1779. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.6.1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackay CR, Marston WL, Dudler L. Naive and memory T cells show distinct pathways of lymphocyte recirculation. J Exp Med. 1990;171:801–817. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randolph GJ, Angeli V, Swartz MA. Dendritic-cell trafficking to lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:617–628. doi: 10.1038/nri1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JB, McIntosh GH, Morris B. The traffic of cells through tissues: a study of peripheral lymph in sheep. J Anat. 1970;107:87–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pullinger BD, Florey HW. Proliferation of lymphatics in inflammation. The Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology. 1937;45:157–170. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baluk P, Tammela T, Ator E, Lyubynska N, Achen MG, Hicklin DJ, Jeltsch M, Petrova TV, Pytowski B, Stacker SA, Yla-Herttuala S, Jackson DG, Alitalo K, McDonald DM. Pathogenesis of persistent lymphatic vessel hyperplasia in chronic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:247–257. doi: 10.1172/JCI22037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cursiefen C, Chen L, Borges LP, Jackson D, Cao J, Radziejewski C, D'Amore PA, Dana MR, Wiegand SJ, Streilein JW. VEGF-A stimulates lymphangiogenesis and hemangiogenesis in inflammatory neovascularization via macrophage recruitment. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1040–1050. doi: 10.1172/JCI20465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerjaschki D, Huttary N, Raab I, Regele H, Bojarski-Nagy K, Bartel G, Krober SM, Greinix H, Rosenmaier A, Karlhofer F, Wick N, Mazal PR. Lymphatic endothelial progenitor cells contribute to de novo lymphangiogenesis in human renal transplants. Nat Med. 2006;12:230–234. doi: 10.1038/nm1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furtado GC, Marinkovic T, Martin AP, Garin A, Hoch B, Hubner W, Chen BK, Genden E, Skobe M, Lira SA. Lymphotoxin beta receptor signaling is required for inflammatory lymphangiogenesis in the thyroid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5026–5031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606697104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angeli V, Ginhoux F, Llodra J, Quemeneur L, Frenette PS, Skobe M, Jessberger R, Merad M, Randolph GJ. B cell-driven lymphangiogenesis in inflamed lymph nodes enhances dendritic cell mobilization. Immunity. 2006;24:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamieson T, Cook DN, Nibbs RJ, Rot A, Nixon C, McLean P, Alcami A, Lira SA, Wiekowski M, Graham GJ. The chemokine receptor D6 limits the inflammatory response in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:403–411. doi: 10.1038/ni1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szuba A, Skobe M, Karkkainen MJ, Shin WS, Beynet DP, Rockson NB, Dakhil N, Spilman S, Goris ML, Strauss HW, Quertermous T, Alitalo K, Rockson SG. Therapeutic lymphangiogenesis with human recombinant VEGF-C. FASEB J. 2002;16:1985–1987. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0401fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Regulation of T cell immunity by dendritic cells. Cell. 2001;106:263–266. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinman RM, Turley S, Mellman I, Inaba K. The induction of tolerance by dendritic cells that have captured apoptotic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:411–416. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawiger D, Inaba K, Dorsett Y, Guo M, Mahnke K, Rivera M, Ravetch JV, Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J Exp Med. 2001;194:769–779. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geissmann F, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Dezutter C, Valladeau J, Kayal S, Leborgne M, Brousse N, Saeland S, Davoust J. Accumulation of immature Langerhans cells in human lymph nodes draining chronically inflamed skin. J Exp Med. 2002;196:417–430. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonifaz L, Bonnyay D, Mahnke K, Rivera M, Nussenzweig MC, Steinman RM. Efficient targeting of protein antigen to the dendritic cell receptor DEC-205 in the steady state leads to antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class I products and peripheral CD8+ T cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1627–1638. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Avoiding horror autotoxicus: the importance of dendritic cells in peripheral T cell tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:351–358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231606698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson LA, Clasper S, Holt AP, Lalor PF, Baban D, Jackson DG. An inflammation-induced mechanism for leukocyte transmigration across lymphatic vessel endothelium. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2763–2777. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu H, Guan H, Zu G, Bullard D, Hanson J, Slater M, Elmets CA. The role of ICAM-1 molecule in the migration of Langerhans cells in the skin and regional lymph node. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3085–3093. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<3085::AID-IMMU3085>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma J, Wang JH, Guo YJ, Sy MS, Bigby M. In vivo treatment with anti-ICAM-1 and anti-LFA-1 antibodies inhibits contact sensitization-induced migration of epidermal Langerhans cells to regional lymph nodes. Cell Immunol. 1994;158:389–399. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopkins AM, Baird AW, Nusrat A. ICAM-1: targeted docking for exogenous as well as endogenous ligands. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:763–778. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Podgrabinska S, Braun P, Velasco P, Kloos B, Pepper MS, Jackson DG, Skobe M. Molecular characterization of lymphatic endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16069–16074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242401399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimaoka M, Takagi J, Springer TA. Conformational regulation of integrin structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:485–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.101101.140922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Madrid F, Krensky AM, Ware CF, Robbins E, Strominger JL, Burakoff SJ, Springer TA. Three distinct antigens associated with human T-lymphocyte-mediated cytolysis: LFA-1, LFA-2, and LFA-3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:7489–7493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diamond MS, Springer TA. A subpopulation of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) molecules mediates neutrophil adhesion to ICAM-1 and fibrinogen. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:545–556. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.2.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skobe M, Hawighorst T, Jackson DG, Prevo R, Janes L, Velasco P, Riccardi L, Alitalo K, Claffey K, Detmar M. Induction of tumor lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C promotes breast cancer metastasis. Nat Med. 2001;7:192–198. doi: 10.1038/84643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimaoka M, Kim M, Cohen EH, Yang W, Astrof N, Peer D, Salas A, Ferrand A, Springer TA. AL-57, a ligand-mimetic antibody to integrin LFA-1, reveals chemokine-induced affinity up-regulation in lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13991–13996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605716103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang L, Shimaoka M, Rondon IJ, Roy I, Chang Q, Po M, Dransfield DT, Ladner RC, Edge AS, Salas A, Wood CR, Springer TA, Cohen EH. Identification and characterization of a human monoclonal antagonistic antibody AL-57 that preferentially binds the high-affinity form of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:905–914. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105649.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakazawa A, Dotan I, Brimnes J, Allez M, Shao L, Tsushima F, Azuma M, Mayer L. The expression and function of costimulatory molecules B7H and B7-H1 on colonic epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1347–1357. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Randolph GJ, Inaba K, Robbiani DF, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of phagocytic monocytes into lymph node dendritic cells in vivo. 1999;11:753–761. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robbiani DF, Finch RA, Jager D, Muller WA, Sartorelli AC, Randolph GJ. The leukotriene C(4) transporter MRP1 regulates CCL19 (MIP-3beta, ELC)-dependent mobilization of dendritic cells to lymph nodes. Cell. 2000;103:757–768. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mosser DM. The many faces of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:209–212. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panes J, Perry MA, Anderson DC, Manning A, Leone B, Cepinskas G, Rosenbloom CL, Miyasaka M, Kvietys PR, Granger DN. Regional differences in constitutive and induced ICAM-1 expression in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H1955–H1964. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.6.H1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu H, Gonzalo JA, St Pierre Y, Williams IR, Kupper TS, Cotran RS, Springer TA, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. Leukocytosis and resistance to septic shock in intercellular adhesion molecule 1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:95–109. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butler M, Ng CY, van Heel DA, Lombardi G, Lechler R, Playford RJ, Ghosh S. Modulation of dendritic cell phenotype and function in an in vitro model of the intestinal epithelium. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:864–874. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riedl E, Stockl J, Majdic O, Scheinecker C, Knapp W, Strobl H. Ligation of E-cadherin on in vitro-generated immature Langerhans-type dendritic cells inhibits their maturation. Blood. 2000;96:4276–4284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang A, Bloom O, Ono S, Cui W, Unternaehrer J, Jiang S, Whitney JA, Connolly J, Banchereau J, Mellman I. Disruption of E-cadherin-mediated adhesion induces a functionally distinct pathway of dendritic cell maturation. Immunity. 2007;27:610–624. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saalbach A, Klein C, Sleeman J, Sack U, Kauer F, Gebhardt C, Averbeck M, Anderegg U, Simon JC. Dermal fibroblasts induce maturation of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:4966–4974. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.4966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pichavant M, Taront S, Jeannin P, Breuilh L, Charbonnier AS, Spriet C, Fourneau C, Corvaia N, Heliot L, Brichet A, Tonnel AB, Delneste Y, Gosset P. Impact of bronchial epithelium on dendritic cell migration and function: modulation by the bacterial motif KpOmpA. J Immunol. 2006;177:5912–5919. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McBride JM, Jung T, de Vries JE, Aversa G. IL-10 alters DC function via modulation of cell surface molecules resulting in impaired T-cell responses. Cell Immunol. 2002;215:162–172. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinbrink K, Wolfl M, Jonuleit H, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of tolerance by IL-10-treated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:4772–4780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hegde S, Pahne J, Smola-Hess S. Novel immunosuppressive properties of interleukin-6 in dendritic cells: inhibition of NF-kappaB binding activity and CCR7 expression. Faseb J. 2004;18:1439–1441. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0969fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mantovani A, Bussolino F, Dejana E. Cytokine regulation of endothelial cell function. Faseb J. 1992;6:2591–2599. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.8.1592209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gabrilovich DI, Chen HL, Girgis KR, Cunningham HT, Meny GM, Nadaf S, Kavanaugh D, Carbone DP. Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marsland BJ, Battig P, Bauer M, Ruedl C, Lassing U, Beerli RR, Dietmeier K, Ivanova L, Pfister T, Vogt L, Nakano H, Nembrini C, Saudan P, Kopf M, Bachmann MF. CCL19 and CCL21 induce a potent proinflammatory differentiation program in licensed dendritic cells. Immunity. 2005;22:493–505. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diamond MS, Garcia-Aguilar J, Bickford JK, Corbi AL, Springer TA. The I domain is a major recognition site on the leukocyte integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) for four distinct adhesion ligands. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:1031–1043. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nestle FO, Zheng XG, Thompson CB, Turka LA, Nickoloff BJ. Characterization of dermal dendritic cells obtained from normal human skin reveals phenotypic and functionally distinctive subsets. J Immunol. 1993;151:6535–6545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grassi F, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, McIlroy D, Jacquet C, Yoneda K, Imamura S, Boumsell L, Schmitt D, Autran B, Debre P, Hosmalin A. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells have a phenotype comparable to that of dermal dendritic cells and display ultrastructural granules distinct from Birbeck granules. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:484–493. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ben Nasr A, Haithcoat J, Masterson JE, Gunn JS, Eaves-Pyles T, Klimpel GR. Critical role for serum opsonins and complement receptors CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and CR4 (CD11c/CD18) in phagocytosis of Francisella tularensis by human dendritic cells (DC): uptake of Francisella leads to activation of immature DC and intracellular survival of the bacteria. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:774–786. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1205755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Behrens EM, Sriram U, Shivers DK, Gallucci M, Ma Z, Finkel TH, Gallucci S. Complement receptor 3 ligation of dendritic cells suppresses their stimulatory capacity. J Immunol. 2007;178:6268–6279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skoberne M, Somersan S, Almodovar W, Truong T, Petrova K, Henson PM, Bhardwaj N. The apoptotic-cell receptor CR3, but not alphavbeta5, is a regulator of human dendritic-cell immunostimulatory function. Blood. 2006;108:947–955. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sohn JH, Bora PS, Suk HJ, Molina H, Kaplan HJ, Bora NS. Tolerance is dependent on complement C3 fragment iC3b binding to antigen-presenting cells. Nat Med. 2003;9:206–212. doi: 10.1038/nm814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Varga G, Balkow S, Wild MK, Stadtbaeumer A, Krummen M, Rothoeft T, Higuchi T, Beissert S, Wethmar K, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Vestweber D, Grabbe S. Active MAC-1 (CD11b/CD18) on DCs inhibits full T-cell activation. Blood. 2007;109:661–669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-023044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oppenheimer-Marks N, Davis LS, Bogue DT, Ramberg J, Lipsky PE. Differential utilization of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 during the adhesion and transendothelial migration of human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1991;147:2913–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Randolph GJ, Furie MB. Mononuclear phagocytes egress from an in vitro model of the vascular wall by migrating across endothelium in the basal to apical direction: role of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and the CD11/CD18 integrins. J Exp Med. 1996;183:451–462. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grabbe S, Varga G, Beissert S, Steinert M, Pendl G, Seeliger S, Bloch W, Peters T, Schwarz T, Sunderkotter C, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Beta2 integrins are required for skin homing of primed T cells but not for priming naive T cells. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:183–192. doi: 10.1172/JCI11703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lutz MB, Schuler G. Immature, semi-mature and fully mature dendritic cells: which signals induce tolerance or immunity? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:445–449. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sporri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory mediators are insufficient for full dendritic cell activation and promote expansion of CD4+ T cell populations lacking helper function. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:163–170. doi: 10.1038/ni1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reis e Sousa C. Dendritic cells as sensors of infection. Immunity. 2001;14:495–498. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.