Abstract

A major question in neuroscience is how diverse subsets of synaptic connections in neural circuits are affected by experience dependent plasticity to form the basis for behavioral learning and memory. Differences in protein expression patterns at individual synapses could constitute a key to understanding both synaptic diversity and the effects of plasticity at different synapse populations. Our approach to this question leverages the immunohistochemical multiplexing capability of array tomography (ATomo) and the columnar organization of mouse barrel cortex to create a dataset comprising high resolution volumetric images of spared and deprived cortical whisker barrels stained for over a dozen synaptic molecules each. These dataset has been made available through the Open Connectome Project for interactive online viewing, and may also be downloaded for offline analysis using web, Matlab, and other interfaces.

Background & Summary

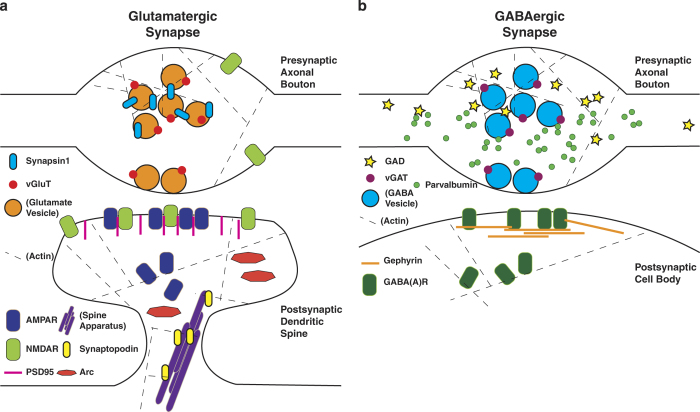

Many hundreds of distinct proteins are involved in the development of synapses and the mechanics of synaptic signaling1–7, and this complex molecular architecture exhibits striking diversity between brain regions, cell types, and even individual synapses belonging to the same neuron8. This complexity at first seems daunting, but may in fact enable researchers to better characterize synaptic populations and their experience-dependent modification. In particular, the definition of different synapse types based on characteristic expression of distinct molecular constituents by may enable identification of subpopulations involved in learning, while identifiable patterns of molecular modifications at existing connections may be used to reveal functional changes in synaptic strength8.

Array tomography (ATomo) is uniquely well suited to proteomic mapping of synaptic circuits. Ultrathin sectioning of resin-embedded tissue samples enables immunohistochemical multiplexing and high-resolution imaging of millions of synapses in situ, followed by computational reconstruction into precisely aligned image volumes9,10. The ability to measure the molecular composition of many individual synapses in the context of the larger circuits they comprise should greatly enhance our understanding of the roles of diverse synapse subsets in neuronal information storage and plasticity. (See Figure 1 for a summary of the method.)

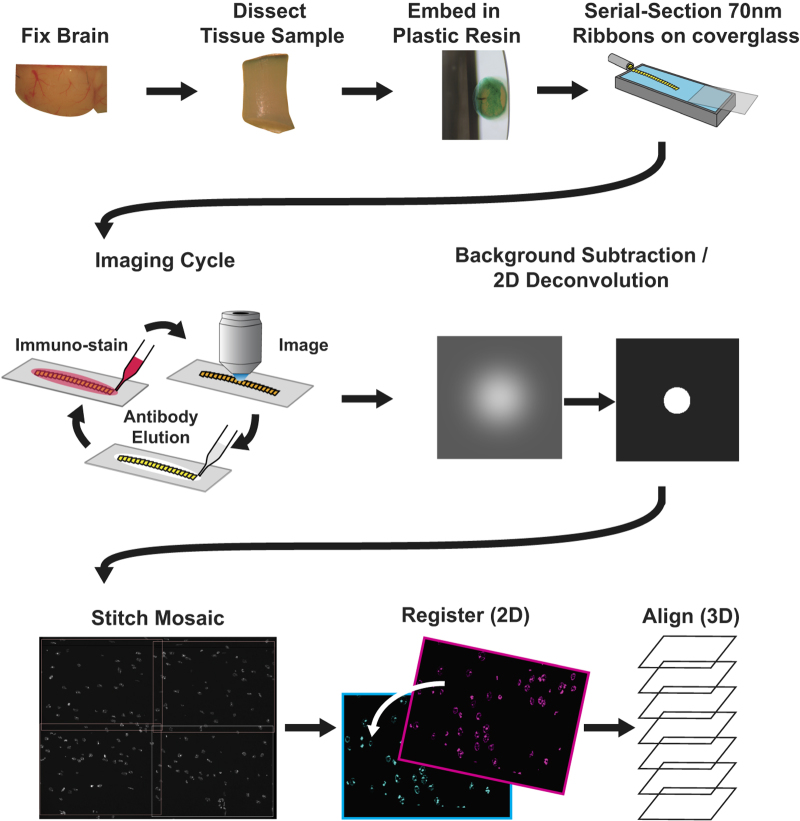

Figure 1. Pipeline of ATomo imaging and reconstruction.

Top Row: array production. Fixed brain tissue is dissected into a small sample, in this case a tissue punch, and embedded in resin (generally LR White). This embedded sample is sectioned into ribbons of ultrathin (50–200 nm) serial sections, which are each affixed to a microscope coverglass to form a stable array. Middle Row: imaging and image processing. A ribbon array is stained with antibodies against selected antigens, and indirect immunofluorescence (IF) is imaged using a high-resolution objective. The antibodies can be removed from the ribbon using a high-pH elution solution, and the array can then be used again for multiple cycles of immunostaining and imaging. Image processing software improves the resolution of the resulting images. Bottom Row: volume reconstruction. Custom software is used for stitching, registration, and alignment of acquired images into volumetric reconstructions of the original tissue sample. ‘Mosaics’ comprising multiple microscope fields of view are stitched into individual images of the same location in each serial section across the ribbon. Images of each serial section from different imaging sessions (with different antibody stains applied) are then registered into the same 2-dimensional data space. Serial sections are then three-dimensionally aligned with one another across the ribbon. Software used for image processing and reconstruction can be found at http://smithlabsoftware.googlecode.com.

To enable this analysis, we have used ATomo to image the synaptic molecular architecture of neighboring whisker-associated columns of mouse somatosensory cortex (S1). The whisker region of S1 is organized as a grid-like spatial map, with rows of thalamically-innervated layer 4 (L4) ‘barrels’ corresponding to the layout of whiskers on the face11,12 (see Figure 2). The circuitry of this cortical barrel field is highly plastic, able to reorganize itself quickly if the whisker layout is altered13. The neurons immediately above and below a given barrel (the ‘barrel column’) normally respond primarily to stimulation of a single principal whisker (PW), but also exhibit weaker surround-whisker (SW) responses. Loss of input from the column’s PW depresses the column’s response to this whisker, while potentiating responses to spared SWs, which can come to dominate circuit activity in the deprived column14,15. This produces a remapping of the barrel field such that the representations of spared whiskers expand into neighboring deprived columns. Plasticity of many different components of the barrel column circuit have been implicated in this remapping, including excitatory and inhibitory synapses in thalamorecipient L4, superficial L2/3 and deep L5 (refs. 16, 17 and 18).

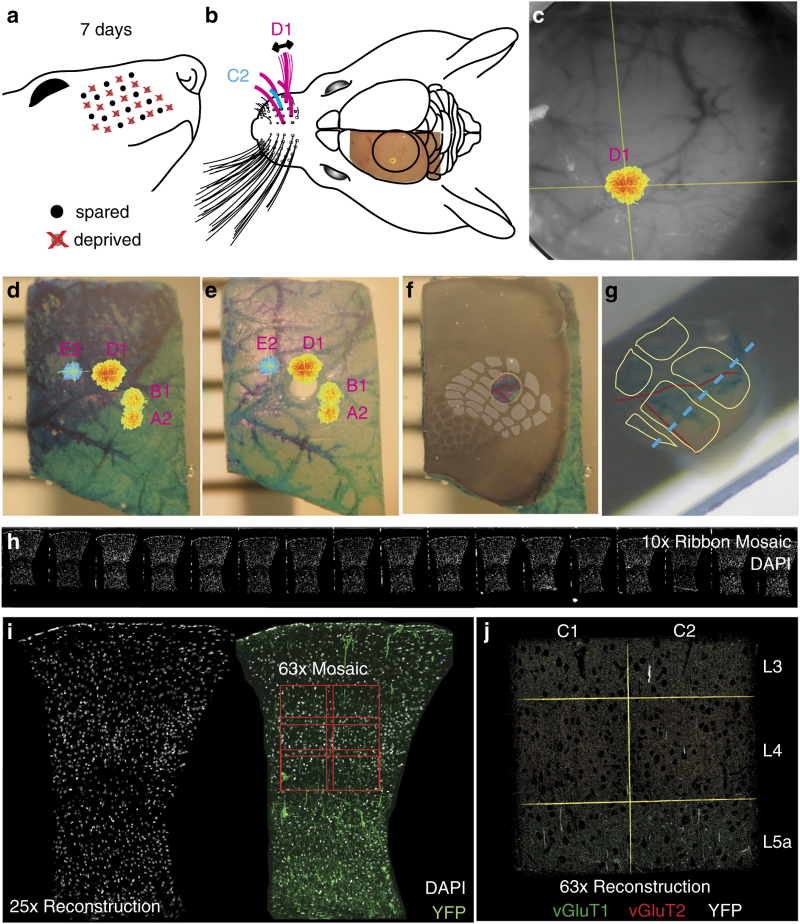

Figure 2. Functionally guided barrel column extraction.

(a) Chessboard pattern of whisker deprivation. (b) Spared whiskers (magenta) surrounding the C2 whisker (cyan) were stimulated in anesthetized mice. Intrinsic optical signal (IOS) imaged transcranially over left somatosensory cortex (S1). (c) In vivo images of D1-whisker stimulation-evoked IOS peak (pseudocolor) and cerebral surface vasculature (grayscale). (d) Fixed and dissected left S1 cortex with tissue paint and registered IOS peaks (pseudocolor). (e) Remainder tissue after removal of tissue punch centered on the C2 whisker column. (f) Cytochrome oxidase (CO)-stained 80 micron-thick section of remainder tissue registered to the intact remainder tissue, with barrel field traced to confirm the correct punch localization (gray overlay). (g) Estimated barrel column positions within embedded tissue punch (yellow outlines) based on vascular and tissue paint features (cf. red traced blood vessels in panel f) with estimate of optimal cross-section through the C1 and C2 barrel columns parallel to the C-row axis (dashed cyan line). (h) Portion of ATomo ribbon imaged for DAPI at 10x magnification. (i) Maximum-intensity z-projection (MIP) of volume reconstruction of 25x magnification images of ribbon in h. Left: DAPI (gray). Right: DAPI (gray) and YFP (green). High-resolution imaging is targeted to C1 & C2, L3-L5a (red outlines). (j) MIP of multi-session volume reconstruction of 63x magnification images of region shown in (i), with YFP (grey) vGluT1 (green) and vGluT2 (red).

In our experiments, we trimmed alternating facial whiskers of adult mice in a ‘chessboard’ pattern, every 2-3 days for 7 days, which has been shown to produce significant functional and structural plasticity in barrel cortex well into adulthood19–21. We developed a method to precisely dissect pairs of neighboring barrel columns for ATomo imaging, and produced volume reconstructions of stains against many functionally important synaptic molecules in these adjacent spared and deprived columns. Additionally, this data contains cell-type specific transgenic labeling of layer 5 pyramidal neurons with YFP22,23, as well as immunohistochemical labeling of PV+ interneurons24–26. Thus, synaptic subpopulations may be classified based on characteristic molecular signatures or association with YFP+ pyramidal neurons or PV+ interneurons, and the prevalence of these populations as well as changes in expression of molecules thought to play a role in experience-dependent plasticity may be compared between spared and deprived columns.

The Chessboard Dataset described here comprises over 6 million cubic microns of neocortical tissue within a well-defined microanatomical structure, stained for over a dozen different synaptic proteins and imaged at synaptic resolution. As such, it is likely to be a valuable resource for researchers interested in statistical characterization of the diversity of protein expression patterns in mouse neocortical synapses and the effects of experience-dependent plasticity on these patterns8. We make this dataset publicly available alongside two supplementary datasets (see Data Records) in the hopes that other researchers will apply their own creative approaches to discovering patterns of synapse molecular diversity and novel signatures of experience dependent cortical learning.

Methods

Animals

All procedures related to the care and treatment of animals were approved by the Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care at Stanford University. Animals used to generate these datasets were derived from hemizygous transgenic founder mice of the thy1-yfp H line22 purchased from Jackson Labs (Strain Name: B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-YFP)HJrs/J, Stock number: 003782). Mouse Ex1 was excluded from the Chessboard Dataset (see Data Records) because it was found not to express YFP. Thereafter, we used the Transnetyx genotyping service to restrict experiments to YFP-positive individuals based on the results of automated rtPCR comparison with JAX gene sequences.

Chessboard whisker deprivation

We induced experience dependent map plasticity in 8 adult male mice (P63-70) by unilaterally trimming facial whiskers on the right side of the face in a chessboard pattern (that is, alternating spared and trimmed whiskers) every 2-3 days for 7 days (Figure 2a). We trimmed whiskers to within 1 mm of the face, and did not observe significant regrowth between trimming sessions. Of the 7 mice included in the Chessboard Dataset (see Data Records), 4 had the chessboard pattern centered on a spared C2 whisker (C2 spared), and 3 had the chessboard pattern centered on a deprived C2 whisker (C2 deprived). Animals were group-housed and supplied with cardboard tubes for mild enrichment and to discourage whisker barbering by cagemates27. Mice were excluded from these dataset if any whisker loss was observed in addition to the chessboard trimming.

Rodent surgery

Following 7 days of chessboard deprivation, we imaged whisker-evoked intrinsic optical signals (IOS)28 to localize barrel columns C1 and C2 for dissection. Mice were sedated with intraperitoneal injections of 0.05 ml chlorprothixene and anesthetized with isoflurane (0.8% in O2). Mice were kept on a heating pad, and we ensured that mice remained at a stable level of anesthesia by monitoring their core temperature and tracking their respiration rate. We also locally anesthetized the scalp with subcutaneous injections of ~0.01 ml lidocaine. We covered the eyes with petroleum jelly and provided hydration with a pre-operative subcutaneous injection of 0.5 ml physiological saline.

We stabilized the heads of the mice with ear-bars and surgically exposed a region of the skull overlying the left somatosensory cortex. We then affixed a custom metal head-plate with a 2 mm round imaging window to the exposed skull approximately centered on the location of left barrel cortex, and clamped this head plate to a metal post attached to the imaging apparatus. Once the mice were thus head-fixed, we removed the ear-bars, filled the imaging window with warm low-melting-point agarose, and covered the window with a round glass coverslip.

Intrinsic Optical Signal (IOS) imaging

To identify the location of barrel-columns C1 and C2 without producing additional plasticity in these columns by direct stimulation, we used IOS imaging to map the representations of adjacent spared whiskers (Figure 2b). In C2-spared mice, we mapped the locations of the spared A2, B1, D1 and E2 whisker representations, while in C1-spared mice, we mapped the spared A1, B2, D2, and E1 whiskers. We used a custom piezo-electric actuator (PiezoSystems) to stimulate individual right facial whiskers at 10 Hz in 5-second bouts with an inter-stimulus interval of 15 s. The imaging window was illuminated with a 630 nm red/orange LED light (LumiLEDs), and a Pantera 1M30 camera (Dalsa) equipped with a nose-to-nose macro-lens was used to record changes in reflectance through the skull29. We measured IOS with the camera focused 500 microns beneath the cortical surface to maximize signals originating L4 barrels.

IOS peaks associated with the 0.05 Hz period of whisker stimulation bouts were obtained using LabView software designed by David Ferster, which calculated the real-time fast fourier transform (FFT) of changes in reflectance at this frequency. This FFT-based method allows fast and robust detection of stimulus-associated IOS peaks with little interference from other cardiovascular rhythms, which occur at much higher frequencies30. Clear IOS peaks were generally detected within 15 bouts (~5 min) of stimulation. For each whisker, once an IOS peak was established, we photographed the vascular pattern at the surface of the cortex with contrast enhanced by 530 nm green LED illumination (LumiLEDs). Because the position of the camera relative to the imaging window could shift slightly as we switched whiskers, we registered the vascular images and their paired IOS peaks to map the location of each whisker-associated peak relative to the surface vasculature (Figure 2c).

Barrel column dissection

Following IOS imaging, animals were deeply anesthetized with 5% isoflurane, their brains extracted and the left somatosensory cortex dissected and immersed in fixative (4% PFA, 2.5% sucrose in 0.01 M PBS)31. We estimated the locations of the C-row barrel columns by registering in vivo images of the surface vasculature collected under 530 nm illumination to the visible vasculature of the fixed somatosensory cortex tissue. We used tissue paint (Polysciences) to help reveal additional vascular features in the fixed tissue and to highlight the estimated position of the C-row of the barrel field (Figure 2d). We embedded this painted tissue in agarose gel for stability, and used a custom guide-chamber and sharpened oval tube (inner diameter ~1×0.75 mm) to precisely target extraction of a tissue punch centered on the border between barrels C1 and C2 (Figure 2e), as estimated by vascular and tissue-paint features registered to the functionally measured ISI peaks. The punched tissue was then embedded in LR-white resin for ultra-thin sectioning into ATomo ribbons (see ATomo Tissue Processing, below).

Cytochrome oxidase staining

We confirmed that our punch contained the C1 and C2 barrel columns by making 80-micron sections of the somatosensory cortex tissue remaining after the tissue punch procedure (hereafter ‘remainder tissue’), and stained these for CO to reveal the pattern of the barrel field in layer 4. We then registered our standard barrel field map to the CO stain of remainder tissue sections to reveal which barrels overlapped with the punched-out hole in these sections (Figure 2f).

The CO-stained sections also allowed us to estimate the precise position and orientation of the columns contained within the embedded tissue-punch in order to plan the sectioning of ribbons for ATomo (Figure 2g). For this purpose, we registered images of the vascular features and tissue paint at the pia surface at each stage of the dissection procedure. Based on these common features, we were able to register images of 1) the fixed tissue prior to punch extraction, 2) the superficial sections of post-punch remainder tissue, and 3) the surface of the punched tissue before and after embedding. We aligned adjacent sections of the remainder tissue from the superficial sections containing vascular features down to the L4 sections containing the CO-stained barrel field based on vertically projecting capillaries visible from section to section. Following this alignment, the standard barrel field map and embedded punch images were also in registry, and so we could estimate the locations of the embedded barrel columns with great precision.

ATomo tissue processing

We dehydrated the tissue punches containing C1 and C2 columns in ascending alcohols up to 80% to retain YFP fluorescence, and embedded them in LR White resin according to previously published methods9,31,32.

The resin block was oriented based on the registration procedure described above (Figure 2g) and sectioned into ribbons of 70 nm serial sections (~50 sections/ribbon) parallel to the axis of the C-row such that each ribbon comprised ~3.5 micron cross-sections of the embedded C1 and C2 columns and contained all layers of cortex between the pia surface and the subcortical white matter33. We collected 40–100 ribbons from each embedded block, enough to contain all or most of the targeted pairs of barrel columns. Although we could in principle attempt to reconstruct the columns in their entirety, the scale of such a project was outside the capabilities of our current image acquisition and reconstruction pipeline. Instead, for each block we identified the ribbon that best approximated a plane passing through the centers of both neighboring barrels for imaging and reconstruction (Figure 2g). To aid in this selection, we took sequential pictures of the surface of the punch during sectioning to keep track of our progress through the columns, so that we could select ribbons from as near as possible to the C-row center (that is, equidistant from rows B and D).

Note that for most animals, ribbons were cut from the tissue punch starting from the E-side of the C-row (Ex1, Ex2, Ex3, Ex6, Ex10, Ex14) while others were cut from the B-side (Ex12, Ex13), producing different left-right orientations of the columns in the final data volumes (See Table 1).

Table 1. Animals and Ribbons.

| Animal ID | Dataset | Age | Sex | Transgenic Line | Imaged Ribbon(s) | Deprivation Pattern | Columns Contained * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The nine chessboard deprived animals used in these experiments, their vital statistics, and derived ribbons/tissue samples. |

|||||||

| Ex1 | Elution-Test | 9 weeks | male | thy1-yfp line-H | Ribbon 2Ribbon 7Ribbon 8 | C2-spared | [C1, C2] |

| Ex2 | Chessboard | 9 weeks1 day | male | thy1-yfp line-H | Ribbon 18 | C2-spared | [ß, C1, C2] |

| Ex3 | Chessboard | 9 weeks1 day | male | thy1-yfp line-H | Ribbon 43 | C2-spared | [C1, C2, C3] |

| Ex6 | Chessboard | 9 weeks | male | thy1-yfp line-H | Ribbon 15 | C2-spared | [C1, C2] |

| Ex10 | Chessboard | 9 weeks5 days | male | thy1-yfp line-H | Ribbon 55 | C2-deprived | [C1, C2] |

| Ex12 | Chessboard | 9 weeks5 days | male | thy1-yfp line-H | Ribbon 75Ribbon 76 | C2-deprived | [C3, C2, C1] |

| Ex13 | Chessboard | 9 weeks2 days | male | thy1-yfp line-H | Ribbon 51 | C2-spared | [C2, C1] |

| Ex14 | Chessboard | 9 weeks3 days | male | thy1-yfp line-H | Ribbon 58 | C2-deprived | [C1, C2] |

*Note that for most animals, ribbons were cut from the tissue punch starting from the E-side of the C-row (Ex1, Ex2, Ex3, Ex6, Ex10, Ex14) while others were cut from the B-side (Ex12, Ex13), producing different orientations of the columns in the final data volumes, as indicated under the ‘Columns Contained’ heading.

ATomo ribbon imaging

For all imaging experiments, we first create a low-resolution overview of the ribbon to be imaged by making a mosaic image at low magnification (10x) of a DAPI stain for cell nuclei included in the mounting medium (molecular probes ref S36939) (Figure 2h). To ensure that we selected good quality ribbons for high-resolution immunohistochemical imaging, we imaged DAPI and intrinsic YFP fluorescence in several ribbons surrounding the estimated row center with a 25x magnification objective (Zeiss). These 25x images allowed us to reconstruct large cross-sections of barrel columns (Figure 2i; see ATomo Image Processing and Reconstruction, below), which aided in selecting ribbons taken from closest to the barrel centers, based on their larger barrel hollows visible as lower DAPI and YFP density. Once a ribbon was selected, the 25x DAPI/YFP images were also used to identify boundaries between columns and layers to guide higher magnification imaging of layers 3–5a in columns C1 and C2. Column boundaries could be detected by the higher density of YFP dendrites running between columns. The centers of L4 barrels were identified by their low DAPI density compared to higher density ‘septal’ regions between barrels, which is a characteristic feature of mouse barrel cortex15.

For selected ribbons from each chessboard-deprived animal, we performed 6–8 rounds of triple or quadruple immunostaining, paired with high-resolution imaging with a 63x plan-apochromat objective (Zeiss)34,35. For all sections in each ribbon, we imaged a region of the section corresponding to layers 3-5a in all of the columns present (C1-C2 in 5 animals, C1-C3 in 1 animal). Automated mosaic imaging of the selected region was targeted using custom software (MosaicPlanner; available at https://smithlabsoftware.googlecode.com/). For several ribbons, to minimize focus artifacts resulting from deviations of the 70 nm sections from the objective’s limited focal plane, z-stacks of each mosaic position were imaged and then computationally merged using an extended depth of field algorithm (Zeiss Axiovision).

ATomo image processing and reconstruction

All custom code described in this section is available for download at https://smithlabsoftware.googlecode.com .

Image processing

Following imaging, we used plugins available in the FIJI image processing software as well as custom routines to create high-dimensional volume reconstructions of the imaged tissue with all of the antibody stains in registry. First, all images were background subtracted using a 20 pixel rolling ball filter (FIJI/ImageJ) and deconvolved (Matlab) based on empirical point-spread functions measured with fluorescent tetraspeck beads. Following deconvolution, the effective resolution of the images was 100×100×70 nm (ref. 36).

Mosaic stitching

We used a DAPI nuclear stain present in our mounting medium in all imaging sessions as a fiducial marker both for stitching together adjacent microscope fields of view and registering images of the same tissue sections taken in different imaging sessions (see below).

2D registration

Minor shifts in the position of the coverslip-affixed ribbon between imaging sessions can be simply modeled as rigid linear transformations to achieve appropriate session registration using custom FIJI/ImageJ plugins. These transformations were calculated based on SIFT features detected in the corresponding DAPI images from each imaging session37. These features were filtered using RANSAC38 to detect inliers specifying the model for rigid transformation between sessions, which could then be applied to images from the other channels of that session to bring them into registry with the first session.

3D alignment

Unlike the rigid transformations used for 2d registration between imaging sessions, mechanical deformations of the tissue during the process of sectioning make the transformations needed for 3d alignment of ultrathin serial-section images significantly nonlinear. Synapse-scale alignment was achieved with another custom FIJI/ImageJ plugin by applying the elastic algorithm developed by Saalfeld and colleagues to the Synapsin1 channel39. This channel was used for fine alignment because it densely and reliably stains synapses across multiple 70 nm sections. The alignment calculated from Synapsin1 was then applied to all of the other channels already in registry to produce full multi-channel reconstructed data volumes.

Data Records

There are 3 data records associated with this data descriptor, all derived from serial-section ribbons from 9 chessboard-deprived mice (Table 1), imaged across multiple rounds of staining with a panel of 21 antibodies (Table 2).

Table 2. Antibody Panel.

| Name | Species | Clonality | Company | Clone | Catalogue no. | Concent-ration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The 21 antibodies used in the Chessboard and Elution-Test datasets (Data Citation 1) and their vital statistics. NB: some of these antibodies were used in only a subset of ribbons/data volumes. Names of antibodies used in all ribbons/data volumes are labeled in bold. (GAD2 and GAD65/67 are labeled in bold because one or the other antibody was used in every ribbon to label the same antigen.) | ||||||

| 1. Arc | Guinea Pig | poly | Synaptic Systems | N/A | 156,005 | 1:150 |

| 2. CB | Rabbit | mono | Cell Signaling | C26D12 | 2,173 | 1:100 |

| 3. GABAARa1 | Mouse | mono | NeuroMABs | N95/35 | 75–136 | 1:100 |

| 4. gActin | Mouse | mono | Sigma | 2-2.1.14.17 | A8481 | 1:100 |

| 5. GAD2 | Rabbit | mono | Cell Signaling | D5G2 | 3,988 | 1:200 |

| 6. GAD6567 | Rabbit | poly | AbCAM | N/A | AB11070 | 1:1,000 |

| 7. Gephyrin | Mouse | mono | BD Biosciences | 45 | 612,632 | 1:300 |

| 8. GFP | Chicken | poly | GeneTex | N/A | GTX13970 | 1:100 |

| 9. GluR1 | Rabbit | poly | Millipore | N/A | AB1504 | 1:100 |

| 10. GluR2 | Mouse | mono | Millipore | 6C4 | MAB397 | 1:50 |

| 11. GluR4 | Rabbit | mono | Cell Signaling | D41A11 | 8070P | 1:50 |

| 12. NR2A | Mouse | mono | NeuroMABs | NN327/95 | 75–288 | 1:50 |

| 13. NR2B | Mouse | mono | NeuroMABs | N59/36 | 75–101 | 1:500 |

| 14. PSD95 | Rabbit | mono | Cell Signaling | D27E11xP | 34,505 | 1:200 |

| 15. PV25 | Rabbit | poly | Swant | N/A | PV 25 | 1:100 |

| 16. Synapsin1 | Rabbit | mono | Cell Signaling | D12G5 | 52,975 | 1:200 |

| 17. Synaptopodin | Rabbit | poly | Synaptic Systems | N/A | 163,002 | 1:500 |

| 18. vGAT | Mouse | mono | Synaptic Systems | 117G4 | 131,011 | 1:100 |

| 19. vGluT1 | Guinea Pig | poly | Millipore | N/A | AB5905 | 1:5,000 |

| 20. vGluT2 | Guinea Pig | poly | Millipore | N/A | AB2251 | 1:5,000 |

| 21. vGluT3 | Guinea Pig | poly | Millipore | N/A | AB5421 | 1:5,000 |

1: Chessboard dataset

The primary Chessboard Dataset consists of 12 reconstructed data volumes (Table 3 (available online only)) comprising 20–25 immunohistochemical channels each (Table 4 (available online only)). These data volumes were reconstructed from multiple rounds of imaging of eight ribbons of serial sections containing paired spared and deprived barrel columns from seven chessboard-deprived mice (Table 5 (available online only)).

Table 3. Chessboard Dataset Data Volumes.

| Data Volume Token --> | Ex2R18C1 | Ex2R18C2 | Ex3R43C1 | Ex3R43C2 | Ex3R43C3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provenance and size of 12 data volumes derived from 8 Chessboard Dataset ribbons/tissue samples (Data Citation 1, Files 8–295 Supplementary Table 1). There are more data volumes than ribbons because the barrel columns in some ribbons were imaged without sufficient overlap for stitching to produce a combined dataset. Three ribbons (Ex2R18, Ex3R43, and Ex6R15) have separate data volumes for each barrel column, and five ribbons (Ex10R55, Ex12R75, Ex12R76, Ex13R51, and Ex14R58) have all columns included in a single data volume. The total Chessboard Dataset volume is 5,141,887 μm^3, and the average volume per ribbon (including multiple data volumes per ribbon when applicable) is 642,736 μm^3. | |||||

| Animal | Ex2 | Ex2 | Ex3 | Ex3 | Ex3 |

| Ribbon | R18 | R18 | R43 | R43 | R43 |

| Subregion | C1 | C2 | C1 | C2 | C3 |

|

Size

|

|||||

| x (px) | 2,176 | 2,048 | 2,176 | 2,048 | 2,048 |

| y (px) | 3,328 | 3,200 | 3,328 | 3,200 | 3,328 |

| z (px) | 43 | 43 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

|

Resolution

|

|||||

| x (nm/px) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| y (nm/px) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| z (nm/px) | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Volume (um^3) | 217,976 | 197,263 | 354,845 | 321,126 | 333,971 |

| Data Volume Token --> | Ex6R15C1 | Ex6R15C2 | Ex10R55 | Ex12R75 | Ex12R76 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provenance and size of 12 data volumes derived from 8 Chessboard Dataset ribbons/tissue samples (Data Citation 1, Files 8–295 Supplementary Table 1). There are more data volumes than ribbons because the barrel columns in some ribbons were imaged without sufficient overlap for stitching to produce a combined dataset. Three ribbons (Ex2R18, Ex3R43, and Ex6R15) have separate data volumes for each barrel column, and five ribbons (Ex10R55, Ex12R75, Ex12R76, Ex13R51, and Ex14R58) have all columns included in a single data volume. The total Chessboard Dataset volume is 5,141,887 μm^3, and the average volume per ribbon (including multiple data volumes per ribbon when applicable) is 642,736 μm^3. | |||||

| Animal | Ex6 | Ex6 | Ex10 | Ex12 | Ex12 |

| Ribbon | R15 | R15 | R55 | R75 | R76 |

| Subregion | C1 | C2 | |||

|

Size

|

|||||

| x (px) | 3,328 | 3,328 | 3,456 | 5,504 | 6,016 |

| y (px) | 3,584 | 3,712 | 3,456 | 4,864 | 4,992 |

| z (px) | 31 | 31 | 71 | 36 | 36 |

|

Resolution

|

|||||

| x (nm/px) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| y (nm/px) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| z (nm/px) | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Volume (um^3) | 258,828 | 268,072 | 593,614 | 674,641 | 756,803 |

| Data Volume Token --> | Ex13R51 | Ex14R58 |

|---|---|---|

| Provenance and size of 12 data volumes derived from 8 Chessboard Dataset ribbons/tissue samples (Data Citation 1, Files 8–295 Supplementary Table 1). There are more data volumes than ribbons because the barrel columns in some ribbons were imaged without sufficient overlap for stitching to produce a combined dataset. Three ribbons (Ex2R18, Ex3R43, and Ex6R15) have separate data volumes for each barrel column, and five ribbons (Ex10R55, Ex12R75, Ex12R76, Ex13R51, and Ex14R58) have all columns included in a single data volume. The total Chessboard Dataset volume is 5,141,887 μm^3, and the average volume per ribbon (including multiple data volumes per ribbon when applicable) is 642,736 μm^3. | ||

| Animal | Ex13 | Ex14 |

| Ribbon | R51 | R58 |

|

Subregion

|

||

| Size

|

||

| x (px) | 5,248 | 4,864 |

| y (px) | 5,888 | 3,456 |

| z (px) | 31 | 42 |

| Resolution

|

||

| x (nm/px) | 100 | 100 |

| y (nm/px) | 100 | 100 |

| z (nm/px) | 70 | 70 |

| Volume (um^3) | 670,535 | 494,214 |

Table 4. Chessboard Dataset Antibody Channels.

| Ribbon ID > v Channel ID | Ex2R18 | Ex3R43 | Ex6R15 | Ex10R55 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| List of antibody channels for each ribbon in the Chessboard Dataset (Data Citation 1, Files 8–295 Supplementary Table 1). Channel names are in the form ‘[antibody name]—[imaging round]’. The left-hand column lists channel numeric tokens, which can be used in place of channel names in the OCP hdf5 interface (See Usage Notes: OCP Data Access). NB: certain stains were repeated several times (Ex3R43 vGluT2, Ex10R55 vGAT, Ex14R58 vGluT2 & vGluT2) when initial images were judged of insufficiently high quality (See Table 5). We recommend focusing analysis on the last imaged version of these repeated antibodies, though we make all data available as repeated staining may be of interest. | ||||

| 1 | DAPI-1 | PSD95-2 | DAPI-1 | Arc-5 |

| 2 | DAPI-2 | DAPI-7 | DAPI-2 | Calbindin-7 |

| 3 | DAPI-3 | vGluT2-7 | DAPI-3 | DAPI-1 |

| 4 | DAPI-4 | vGAT-4 | DAPI-4 | DAPI-2 |

| 5 | DAPI-5a | GABAARa1-8 | DAPI-5 | DAPI-3 |

| 6 | DAPI-5b | NR2B-7 | DAPI-6 | DAPI-4 |

| 7 | DAPI-6 | Arc-3 | GABAARa1-6 | DAPI-5 |

| 8 | DAPI-7 | Gephyrin-1 | GAD2-3 | DAPI-6 |

| 9 | GABAARa1-7 | PV25-1 | Gephyrin-2 | DAPI-7 |

| 10 | GAD2-4 | Synaptopodin-7 | GluR1-4 | DAPI-8 |

| 11 | GFP-5b | GAD6567-4 | GluR2-5 | GABAARa1-7 |

| 12 | Gephyrin-1 | NR2A-4 | NR2A-1 | GAD2-3 |

| 13 | GluR1-5a | vGluT2-1 | NR2B-3 | GFP-4 |

| 14 | GluR2-6 | DAPI-8 | PSD95-1 | Gephyrin-2 |

| 15 | GluR4-7 | NR2B-3 | PV25-5 | GluR1-4 |

| 16 | NR2A-2 | GluR2-6 | Synapsin1-2 | GluR2-8 |

| 17 | NR2B-4 | DAPI-6 | Synaptopodin-6 | GluR4-8 |

| 18 | PSD25-2 | GFP-4 | YFP-1 | NR2A-1 |

| 19 | PV25-1 | vGluT1-2 | vGAT-4 | NR2B-3 |

| 20 | Synapsin-3 | GluR4-8 | vGluT1-3 | PSD95-1 |

| 21 | Synaptopodin-6 | GluR1-6 | vGluT2-2 | PV25-5 |

| 22 | YFP-1 | DAPI-1 | Synapsin1-2 | |

| 23 | vGAT-3 | Synapsin1-3 | Synaptopodin-6 | |

| 24 | vGluT1-3 | DAPI-2 | YFP-1 | |

| 25 | vGluT2-2 | DAPI-3 | vGAT-4 | |

| 26 | DAPI-4 | vGAT-5 | ||

| 27 | vGAT-6 | |||

| 28 | vGluT1-3 | |||

| 29 | vGluT2-2 |

| Ribbon ID > v Channel ID | Ex12R75 | Ex12R76 | Ex13R51 | Ex14R58 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| List of antibody channels for each ribbon in the Chessboard Dataset (Data Citation 1, Files 8–295 Supplementary Table 1). Channel names are in the form ‘[antibody name]—[imaging round]’. The left-hand column lists channel numeric tokens, which can be used in place of channel names in the OCP hdf5 interface (See Usage Notes: OCP Data Access). NB: certain stains were repeated several times (Ex3R43 vGluT2, Ex10R55 vGAT, Ex14R58 vGluT2 & vGluT2) when initial images were judged of insufficiently high quality (See Table 5). We recommend focusing analysis on the last imaged version of these repeated antibodies, though we make all data available as repeated staining may be of interest. | ||||

| 1 | DAPI-1 | DAPI-1 | GFP-4 | Arc-7 |

| 2 | DAPI-2 | DAPI-2 | Synapsin1-2 | DAPI-1 |

| 3 | DAPI-3 | DAPI-3 | vGluT2-2 | GABAARa1-6 |

| 4 | DAPI-4 | DAPI-4 | GluR2-5 | GAD2-3 |

| 5 | DAPI-5 | DAPI-5 | vGluT1-3 | Gephyrin-2 |

| 6 | DAPI-6 | DAPI-6 | Synaptopodin-6 | GFP-5 |

| 7 | GABAARa1-6 | GABAARa1-6 | GABAARa1-6 | GluR1-4 |

| 8 | GAD2-3 | GAD2-3 | DAPI-6 | GluR2-5 |

| 9 | — | — | vGAT-3 | NR2A-1 |

| 10 | — | — | PV25-5 | NR2B-3 |

| 11 | — | — | NR2B-4 | PSD95-1 |

| 12 | Gephyrin-2 | Gephyrin-2 | GluR1-4 | PV25-5 |

| 13 | GluR1-4 | GluR1-4 | GAD2-3 | Synapsin1-2 |

| 14 | GluR2-5 | GluR2-5 | DAPI-5 | Synaptopodin-7 |

| 15 | NR2A-1 | NR2A-1 | DAPI-4 | vGAT-4 |

| 16 | NR2B-4 | NR2B-4 | DAPI-3 | vGluT1-4 |

| 17 | PSD95-1 | PSD95-1 | PSD95-1 | vGluT1-6 |

| 18 | PV25-5 | PV25-5 | NR2A-1 | vGluT2-2 |

| 19 | Synapsin1-2 | Synapsin1-2 | Gephyrin-2 | vGluT2-3 |

| 20 | Synaptopodin-6 | Synaptopodin-6 | DAPI-2 | YFP-1 |

| 21 | YFP-1 | YFP-1 | DAPI-1 | |

| 22 | vGAT-3 | vGAT-3 | ||

| 23 | vGluT1-3 | vGluT1-3 | ||

| 24 | vGluT2-2 | vGluT2-2 | ||

| 25 | ||||

| 26 | ||||

| 27 | ||||

| 28 | ||||

| 29 |

Table 5. Chessboard Dataset Imaging Log.

| Ribbon | Imaging Session | Imaging Date | primary ab antigen | primary ab raised in | primary ab vendor | primary ab concentration | secondary ab fluorophor | secondary ab against | secondary ab raised in | secondary ab concentration | exposure (ms) | notes/caveats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This table contains a log of all stains/imaging sessions included in the Chessboard Dataset (Data Citation 1, Files 8–295 Supplementary Table 1). All secondary antibodies were raised in goat and applied at a concentration of 1:150. | ||||||||||||

| Ex2-R18 | 1 | 14/8/2012 | Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:300 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 250 | |

| PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 250 | ||||

| (YFP) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,200 | ||||

| 2 | 15/8/2012 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 310 | ||

| NR2A | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 225 | ||||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 1,150 | ||||

| 3 | 16/8/2012 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 50 | slightly messy stain | |

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 350 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa647 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 895 | slightly messy stain | |||

| 4 | 17/8/2012 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | significant bkgd | |

| NR2B | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:500 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | ||||

| 5 | 23/8/2012 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | sparse stain; significant bkgd | |

| GFP | Chx | Genetex | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Chx | Gt | 1:150 | 10 | ||||

| gActin | Ms | Sigma | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,935 | sparse stain; somatic labeling | |||

| 6 | 19/3/2013 | GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa647 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,500 | dim but ubiquitous staining | |

| Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa594 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 100 | bright somatic labeling | |||

| 7 | 25/3/2013 | GluR4 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:50 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 600 | ||

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 700 | ||||

| 8 | 28/3/2013 | GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 700 | high bkgd | |

| GluR4 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:50 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 750 | high bkgd | |||

| Ex3-R43 | 1 | 14/6/2012 | Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:300 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | |

| PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | ||||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | some YFP signal remaining (NB: restained session 7) | |||

| 2 | 15/6/2012 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 600 | ||

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 297 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 140 | ||||

| 3 | 18/6/2012 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 50 | ||

| NR2B | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:450 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 150 | bleedthrough from Arc (NB: restained session 7) | |||

| Arc | GP | Synaptic Systems | 1:150 | Alexa647 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 200 | bright somatic labeling | |||

| 4 | 21/6/2012 | GAD6567 | Rb | AbCAM | 1:1,000 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | ||

| NR2A | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | ||||

| GFP | Chx | GeneTex | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Chx | Gt | 1:150 | 10 | ||||

| 5 | 20/3/2013 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | N/A | Excluded: Used 2 rabbit antibodies by mistake | |

| Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa488 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | N/A | Excluded: Used 2 rabbit antibodies by mistake | |||

| 6 | 22/3/2013 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 600 | significant bkgd; some unbound secondaries ("floaters") | |

| GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa488 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | significant bkgd | |||

| 7 | 26/3/2013 | NR2B | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:500 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | ||

| Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 350 | ||||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 700 | ||||

| Ex6-R15 | 1 | 20/8/2012 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 600 | |

| NR2A | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | ||||

| (YFP) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,000 | ||||

| 2 | 21/8/2012 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 60 | slightly messy stain | |

| Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | ||||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa647 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 2,000 | dim stain | |||

| 3 | 22/8/2012 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 200 | ||

| NR2B | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:500 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 250 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa647 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 650 | ||||

| 4 | 23/8/2012 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 450 | small tissue out-of-focus bubbles, captured by extended depth of field | |

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | ||||

| 5 | 24/8/2012 | PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 220 | ||

| GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 100 | ||||

| 6 | 24/3/2013 | Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 215 | high bkgd | |

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 750 | high bkgd | |||

| Ex10-R55 | 1 | 31/10/2012 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,100 | |

| NR2A | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 665 | ||||

| (YFP) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,750 | ||||

| 2 | 2/11/2012 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 115 | ||

| Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 550 | significant drying artifacts | |||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa647 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 1,750 | ||||

| 3 | 5/11/2012 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | significant bkgd | |

| NR2B | Ms | NeuroMaB | 1:500 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 420 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa647 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 900 | ||||

| 4 | 6/11/2012 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 440 | ||

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | significant staining noise (NB: restained sessions 5 & 6) | |||

| GFP | Chx | GeneTex | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Chx | Gt | 1:150 | 25 | ||||

| 5 | 7/11/2012 | Arc | GP | Synaptic Systems | 1:150 | Alexa647 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 450 | bleedthrough from 594 (PV25) channel | |

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | very high bkgd (NB: restained session 6) | |||

| PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 65 | significant unbound secondaries ("floaters") | |||

| 6 | 8/11/2012 | vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 600 | ||

| Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | ||||

| 7 | 9/11/2012 | CB | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,700 | ||

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 650 | ||||

| 8 | 27/3/2013 | GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | significant staining noise, unbound secondaries ("floaters") | |

| GluR4 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:50 | ALexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 2,000 | very dim staining | |||

| Ex12-R75 | 1 | 8/5/2013 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 900 | |

| NR2A | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 750 | ||||

| (YFP) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 750 | ||||

| 2 | 15/5/2013 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 600 | ||

| Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | ||||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | ||||

| 3 | 17/5/2013 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,150 | ||

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 650 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 450 | ||||

| 4 | 18/5/2013 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 800 | ||

| NR2B | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:500 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 350 | ||||

| 5 | 19/5/2013 | PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | ||

| GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | significant staining noise in first half of ribbon | |||

| 6 | 20/5/2013 | Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa657 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,000 | significant staining noise at end of ribbon | |

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 600 | some unbound secondaries ("floaters") | |||

| Ex12-R76 | 1 | 5/7/2013 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 800 | |

| NR2A | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 350 | significant staining noise in second half of ribbon | |||

| (YFP) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 500 | ||||

| 2 | 9/5/2013 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 350 | ||

| Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 250 | some out-of-focus tissue bubbles, largely corrected by extended depth of field | |||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | ||||

| 3 | 16/5/2013 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,120 | ||

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | ||||

| 4 | 18/5/2013 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 650 | more tissue bubbles | |

| NR2B | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:500 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | ||||

| 5 | 21/5/2013 | PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 250 | large tissue bubbles | |

| GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | ||||

| 6 | 23/5/2013 | Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa657 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,250 | large tissue bubbles full of unbound secondaries ("floaters") | |

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 450 | ||||

| Ex13-R51 | 1 | 6/6/2013 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 950 | somewhat messy stain |

| NR2A | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 750 | messy stain, staining noise | |||

| (YFP) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | very dim—did not image (but see GFP, session 4) | |||

| 2 | 7/6/2013 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | ||

| Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | ||||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 700 | high bkgd | |||

| 3 | 11/6/2013 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 450 | ||

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,500 | very dim—possible bleedthrough from 594 (vGluT1) | |||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa594 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 200 | ||||

| 4 | 12/6/2013 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 400 | ||

| NR2B | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:500 | Alexa647 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,500 | ||||

| GFP | Chx | GeneTex | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Chx | Gt | 1:150 | 30 | ||||

| 5 | 13/6/2013 | PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | ||

| GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 250 | ||||

| 6 | 14/6/2013 | Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:2,500 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 550 | Used incorrect primary concentration, but images fine | |

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 800 | ||||

| Ex14-R58 | 1 | 29/11/2012 | NR2A | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:50 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | |

| PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 600 | ||||

| (YFP) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,150 | ||||

| 2 | 30/11/2012 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 200 | ||

| Gephyrin | Ms | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | mistakenly used 2 mouse primaries: imaged bright Gephyrin at low exposure (little vGluT2 visible) | |||

| vGluT2 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:5,000 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 2,000 | mistakenly used 2 mouse primaries: imaged dim vGluT2 at high exposure (incl. highly saturated Gephyrin puncta) (NB: restained vGluT2 in session 3) | |||

| 3 | 1/12/2012 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,000 | ||

| NR2B | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:500 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 350 | ||||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 800 | very high bkgd—possibly unusable | |||

| 4 | 4/12/2012 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 550 | many unbound secondaries ("floaters") | |

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 550 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa647 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 1,500 | significant staining noise | |||

| 5 | 5/12/2012 | PV25 | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 300 | dim DAPI; staining noise at end of ribbon | |

| GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | ||||

| GFP | Chx | GeneTex | 1:100 | Alexa488 | Chx | Gt | 1:150 | 15 | staining noise at end of ribbon | |||

| 6 | 6/12/2012 | CB | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:100 | Alexa647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,932 | quite dim | |

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:50 | Alexa488 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 600 | bad bkgd (some GFP remaining from session 5?) | |||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa594 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 500 | ||||

| 7 | 7/12/2012 | Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 250 | still some GFP remaining from session 5? | |

| gActin | Ms | Sigma | 1:100 | Alexa594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 358 | some nuclear staining; bleedthrough from Arc | |||

| Arc | GP | Synaptic Systems | 1:150 | Alexa647 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 1,035 | some nuclear staining; staining noise at start of ribbon |

The Chessboard Dataset is hosted for interactive browsing and download through the Open Connectome Project (OCP) at http://openconnecto.me. (For further instructions, see Data Access, below, as well as Usage Notes: OCP Data Access.) Individual data files for each channel in each volume reconstruction are also available through FigShare (Data Citation 1), as files 8–295 described in Supplementary Table 1.

Chessboard dataset caveats

Please note that the number of animals, imaged ribbons, and derived data volumes differ because (1) two ribbons from mouse Ex12 were imaged and (2) multiple barrel columns from ribbons Ex2R18, Ex3R43, and Ex6R15 were reconstructed separately into 2-3 columnar data volumes per ribbon. Also, note that animal ribbon Ex14-R58 was subject to several significant problems during antibody staining (see Table 5 (available online only)), particularly as relates to the staining for vGluT2. We include the derived data volumes in the present dataset with this caveat, and we have excluded this ribbon from the quantification of vGluT puncta density (See Usage Notes: Analysis Recommendations & Caveats).

Data access

There are two ways to access the Chessboard Dataset through OCP: 1) interactively browsing through entire data volumes over the web through OCP’s CATMAID interface, which is ideal for quick visual inspection of the data, or 2) by downloading specific data regions (called ‘cutouts’) through OCP’s HDF5 interface, which is ideal for handling the data for analysis. OCP also has its own API for those wishing to interact more deeply with the project’s data structures. For the most up-to-date descriptions of OCP’s services, visit http://openconnecto.me/#!services/chru.

Online data viewing

CATMAID stands for Collaborative Annotation Toolkit for Massive Amounts of Image Data (http://catmaid.org/). OCP uses this interface to enable fast, browsable online data viewing as well as collaborative data annotation. To view the data, visit http://openconnecto.me/catmaid and browse projects labeled ‘Array Tomography (Weiler et al.)’. You may view these projects only by selecting Home> Array Tomography in the upper left-hand corner of the browser window. We have curated several useful multi-channel volumes to explore, but users may also construct their own combinations of channels to visualize different molecular relationships using hdf5 data cutouts (see below).

Viewing/downloading data cutouts

To access data volumes for analysis, OCP provides a ‘cutout service’ which allows users to download arbitrary 3d data cubes using the HDF5 interface through Matlab, R, C, C++, or C# or by downloading the NumPy pickle for use with python. (See Usage Notes: OCP Data Access for a guide to using the hdf5 web interface to view or download cutouts.).

For additional documentation of the cutout service, see the OCP wiki page at the following address: http://tinyurl.com/OCP-cutout-wiki. We have prepared sample scripts for data access using MATLAB at https://gist.github.com/ncweiler. The cutout service also enables collaborative annotation of the data (labeling neuronal or synaptic structures, for instance). These metadata annotations are registered to the original data and can be either used privately or shared publicly. See more details on data annotations at http://tinyurl.com/OCP-annotation-wiki.

2: Chessboard dataset low-magnification overview images

Prior to the high-resolution, high-magnification imaging that generated the Chessboard Dataset image volumes, we first imaged intrinsic YFP and DAPI-stained cell bodies in each ribbon at low magnification. These images allowed us to create a roughly aligned reconstruction of the complete ribbons, which we then used to help identify anatomical layers and columns for the subsequent high-magnification imaging that generated the Chessboard Dataset image volumes. 2d projections of these whole-ribbon reconstructions, created using either a standard deviation projection or maximum intensity projection (FIJI), are also made available through FigShare as RGB tiff images to support the identification and analysis of specific anatomical regions (Data Citation 2).

3: Elution-test dataset

The supplementary Elution-Test Dataset consists of data volumes derived from seven short ribbon segments derived from mouse Ex1 (Table 6 (available online only)), each stained and imaged repeatedly with a different panel of antibodies (Tables 7 and 8 (available online only)). Analysis of stain repeatability can help estimate the signal to noise ratio of each antibody—the likelihood that a punctum of stain will be seen on repeated staining of the same tissue (see Technical Validation).

Table 6. Elution-Test Dataset Data Volumes.

| Data Volume Token --> | Ex1R02A | Ex1R07A | Ex1R07B | Ex1R07C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provenance and size of 7 data volumes derived from 8 Elution-Test Dataset ribbon segments/tissue samples (Data Citation 1, Files 1–7 Supplementary Table 1). In this dataset, each ribbon was divided into distinct segments, which were stained separately with different antibody panels. These ribbon segments are designated with the letters A through F. The total Elution-Test dataset volume is 88,921 μm^3, and the average data volume size is 14,820 μm^3. | ||||

| Animal | Ex1 | Ex1 | Ex1 | Ex1 |

| Ribbon | R02A | R07A | R07B | R07C |

|

Size

|

||||

| x (px) | 1,388 | 1,388 | 1,388 | 1,388 |

| y (px) | 1,040 | 1,040 | 1,040 | 1,040 |

| z (px) | 4 | 14 | 6 | 16 |

|

Resolution

|

||||

| x (nm/px) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| y (nm/px) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| z (nm/px) | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Volume (um^3) | N/A (not contiguous sections) | 14,146 | 6,063 | 16,167 |

| Data Volume Token --> | Ex1R08D | Ex1R08E | Ex1R08F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provenance and size of 7 data volumes derived from 8 Elution-Test Dataset ribbon segments/tissue samples (Data Citation 1, Files 1–7 Supplementary Table 1). In this dataset, each ribbon was divided into distinct segments, which were stained separately with different antibody panels. These ribbon segments are designated with the letters A through F. The total Elution-Test dataset volume is 88,921 μm^3, and the average data volume size is 14,820 μm^3. | |||

| Animal | Ex1 | Ex1 | Ex1 |

| Ribbon | R08D | R08E | R08F |

|

Size

|

|||

| x (px) | 1,388 | 1,388 | 1,388 |

| y (px) | 1,040 | 1,040 | 1,040 |

| z (px) | 15 | 21 | 16 |

|

Resolution

|

|||

| x (nm/px) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| y (nm/px) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| z (nm/px) | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Volume (um^3) | 15,157 | 21,220 | 16,167 |

Table 7. Elution-Test Dataset Antibody Channels.

| Ribbon ID > v Channel ID | Ex1R02A | Ex1R07A | Ex1R07B | Ex1R07C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| List of antibody channels for each ribbon in the Elution-Test Dataset (Data Citation 1, Files 1-7 Supplementary Table 1). Channel names are in the form ‘[antibody name]—[imaging round]’. | ||||

| 1 | DAPI-1 | DAPI-1 | DAPI-1 | DAPI-1 |

| 2 | DAPI-2 | DAPI-2 | DAPI-2 | DAPI-2 |

| 3 | DAPI-3 | DAPI-3 | DAPI-3 | DAPI-3 |

| 4 | NR2B-1 | NR2A-1 | GAD2-1 | PV25-1 |

| 5 | NR2B-2 | NR2A-2 | GAD2-2 | PV25-2 |

| 6 | NR2B-3 | NR2A-3 | GAD2-3 | PV25-3 |

| 7 | Synapsin1-1 | PSD95-1 | vGAT-1 | Gephyrin-1 |

| 8 | Synapsin1-2 | PSD95-2 | vGAT-2 | Gephyrin-2 |

| 9 | Synapsin1-3 | PSD95-3 | vGAT-3 | Gephyrin-3 |

| 10 | vGluT2-1 | vGluT1-1 | ||

| 11 | vGluT2-2 | vGluT1-2 | ||

| 12 | vGluT2-3 | vGluT1-3 |

| Ribbon ID > v Channel ID | Ex1R08D | Ex1R08E | Ex1R08F |

|---|---|---|---|

| List of antibody channels for each ribbon in the Elution-Test Dataset (Data Citation 1, Files 1-7 Supplementary Table 1). Channel names are in the form ‘[antibody name]—[imaging round]’. | |||

| 1 | DAPI-1 | DAPI-1 | Arc-1 |

| 2 | DAPI-2 | DAPI-2 | Arc-2 |

| 3 | DAPI-3 | DAPI-3 | Arc-3 |

| 4 | GluR1-1 | GABAARa1-1 | DAPI-1 |

| 5 | GluR1-2 | GABAARa1-2 | DAPI-2 |

| 6 | GluR1-3 | GABAARa1-3 | DAPI-3 |

| 7 | GluR2-1 | Synaptopodin-1 | GluR4-1 |

| 8 | GluR2-2 | Synaptopodin-2 | GluR4-2 |

| 9 | GluR2-3 | Synaptopodin-3 | GluR4-3 |

| 10 | |||

| 11 | |||

| 12 |

Table 8. Elution-Test Dataset Imaging Log.

| Ribbon | Imaging Session | Imaging Date | primary ab antigen | primary ab raised in | primary ab vendor | primary ab concentration | secondary ab fluorophor | secondary ab against | secondary ab raised in | secondary ab concentration | exposure (ms) | notes/caveats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This table contains a log of all stains/imaging sessions included in the Elution-Test Dataset (Data Citation 1, Files 1–7 Supplementary Table 1). All secondary antibodies raised in goat and applied at a concentration of 1:150. | ||||||||||||

| Ex1-R02-A | 1 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:300 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 592 | ||

| NR2B | Ms | Millipore | 1:500 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 667 | ||||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa 488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 788 | ||||

| 2 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:300 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 592 | |||

| NR2B | Ms | Millipore | 1:500 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 667 | saturated (would now image at 274 ms) | |||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa 488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 788 | ||||

| 3 | Synapsin1 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:300 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 592 | somewhat saturated (would now image at 459 ms) | ||

| NR2B | Ms | Millipore | 1:500 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 667 | saturated (would now image at 235 ms) | |||

| vGluT2 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa 488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 788 | somewhat saturated (would now image at 575 ms) | |||

| Ex1-R07-A | 1 | 3/6/2014 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:300 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 2,050 | |

| NR2A | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,160 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa 488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 843 | ||||

| 2 | 4/6/2014 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:300 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 2,050 | ||

| NR2A | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,160 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa 488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 843 | ||||

| 3 | 4/6/2014 | PSD95 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:300 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 2,050 | ||

| NR2A | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,160 | ||||

| vGluT1 | GP | Millipore | 1:5,000 | Alexa 488 | GP | Gt | 1:150 | 843 | ||||

| Ex1-R07-B | 1 | 3/6/2014 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa 488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,180 | |

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,090 | ||||

| 2 | 4/6/2014 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa 488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,180 | ||

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,090 | vGAT very messy | |||

| 3 | 4/6/2014 | GAD2 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:200 | Alexa 488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,180 | ||

| vGAT | Ms | Synaptic Systems | 1:100 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,090 | ||||

| Ex1-R07-C | 1 | 3/6/2014 | PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 876 | |

| Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:300 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 964 | ||||

| 2 | 4/6/2014 | PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 876 | PV ubiquitous | |

| Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:300 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 964 | ||||

| 3 | 4/6/2014 | PV25 | Rb | Swant | 1:100 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 876 | ||

| Gephyrin | Ms | BD Biosciences | 1:300 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 964 | ||||

| Ex1-R08-D | 1 | 3/6/2014 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa 488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 800 | background |

| GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 761 | ||||

| 2 | 4/6/2014 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa 488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 800 | ||

| GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 761 | ||||

| 3 | 4/6/2014 | GluR1 | Rb | Millipore | 1:100 | Alexa 488 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 800 | ||

| GluR2 | Ms | Millipore | 1:50 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 761 | ||||

| Ex1-R08-E | 1 | 3/6/2014 | Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,430 | |

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 2,240 | almost no signal | |||

| 2 | 4/6/2014 | Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,430 | ||

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 2,240 | ||||

| 3 | 4/6/2014 | Synaptopodin | Rb | Synaptic Systems | 1:500 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 1,430 | ||

| GABAARa1 | Ms | NeuroMABs | 1:100 | Alexa 594 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 2,240 | ||||

| Ex1-R08-F | 1 | 3/6/2014 | Arc | GP | Synaptic Systems | 1:150 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 2,750 | |

| GluR4 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:50 | Alexa 488 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,370 | ||||

| 2 | 4/6/2014 | Arc | GP | Synaptic Systems | 1:150 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 2,750 | Arc very saturated | |

| GluR4 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:50 | Alexa 488 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,370 | ||||

| 3 | 4/6/2014 | Arc | GP | Synaptic Systems | 1:150 | Alexa 647 | Rb | Gt | 1:150 | 2,750 | ||

| GluR4 | Rb | Cell Signaling | 1:50 | Alexa 488 | Ms | Gt | 1:150 | 1,370 |

In the Elution-Test Dataset, each ribbon was divided into distinct segments, which were stained separately with different antibody panels. These ribbon segments are designated with the letters A through F. Unlike the Chessboard Dataset, only small fields of view from layer 4 were imaged in each of these ribbons, since the objective of this experiment was antibody testing, rather than analysis of differences between regions. Six of ribbon segments have been reconstructed into data volumes, but one other ribbon segment (Ex1-R02A) was imaged at four non-consecutive tissue sections, preventing volumetric reconstruction.

The Elution-Test Dataset may be downloaded from Figshare (Data Citation 1), as files 1–7 described in Supplementary Table 1. Unlike the Chessboard Dataset, each of these files is a zip file containing all channels for a given data volume.

OCP—FigShare dataset cross-reference

See Supplementary Table 1 to cross-reference data files available through the Open Connectome Project (OCP) and FigShare. Files comprising the Chessboard and Elute-Test Datasets (Data Citation 1) are listed alongside the animal and ribbon they derive from, the antibody stains they include, and the accession addresses for the data at both OCP and FigShare.

Note that the OCP web addresses as written will display the full extent of the first slice (z-section) of a multi-slice volume image. To view a smaller region in x or y, adjust the values in the second-to-last and third-to last terms in the HDF5 web address. To view a different slice, adjust the final term in the HDF5 address. (For additional instructions regarding the OCP web interface, see Usage Notes: OCP Data Access.)

Technical Validation

Antibody specificity

All antibodies used in this study have been validated by their originators as reliable and specific to the antigens of interest, and tested within our laboratory for reliable and repeatable staining of ATomo ribbons of LR-white embedded tissue sections. We make sure all antibodies stain in patterns that correspond to their expected synaptic localization. That is, for example, each GABAergic antibody was screened to confirm that it co-stained a significant number of putative GABAergic synapses defined by multiple other GABAergic antibodies, and that it did not excessively stain within cell bodies or blood vessels, where synapses would not be expected.

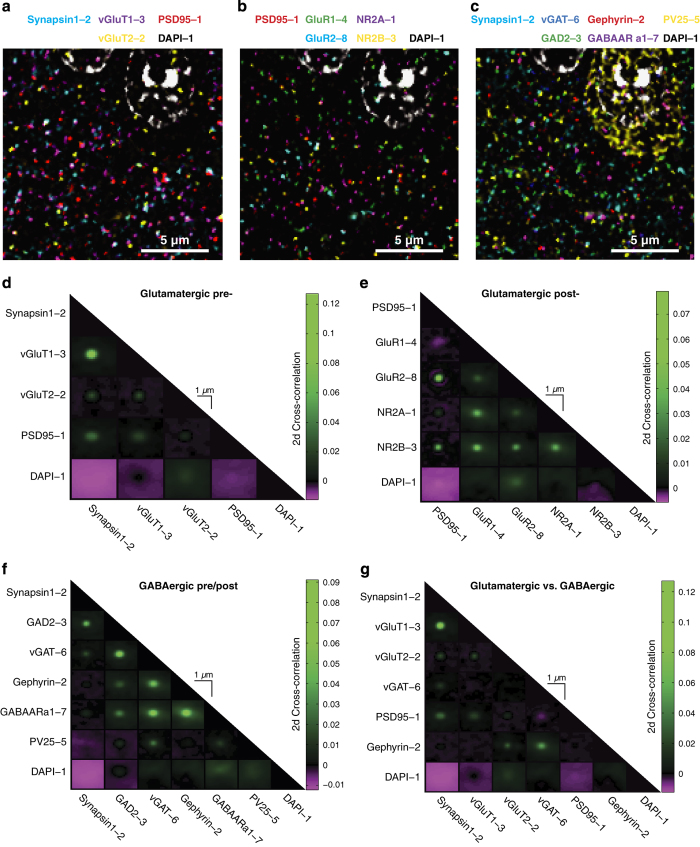

We have quantified these expected staining patterns by performing a pairwise 2-dimensional cross-correlation analysis to quantify spatial correlations (colocalization) between the principal antibodies used in these experiments. Pairwise cross-correlation plots were generated by shifting pairs of registered antibody channels against each other in x and y and calculating 2d image correlations for each spatial shift.

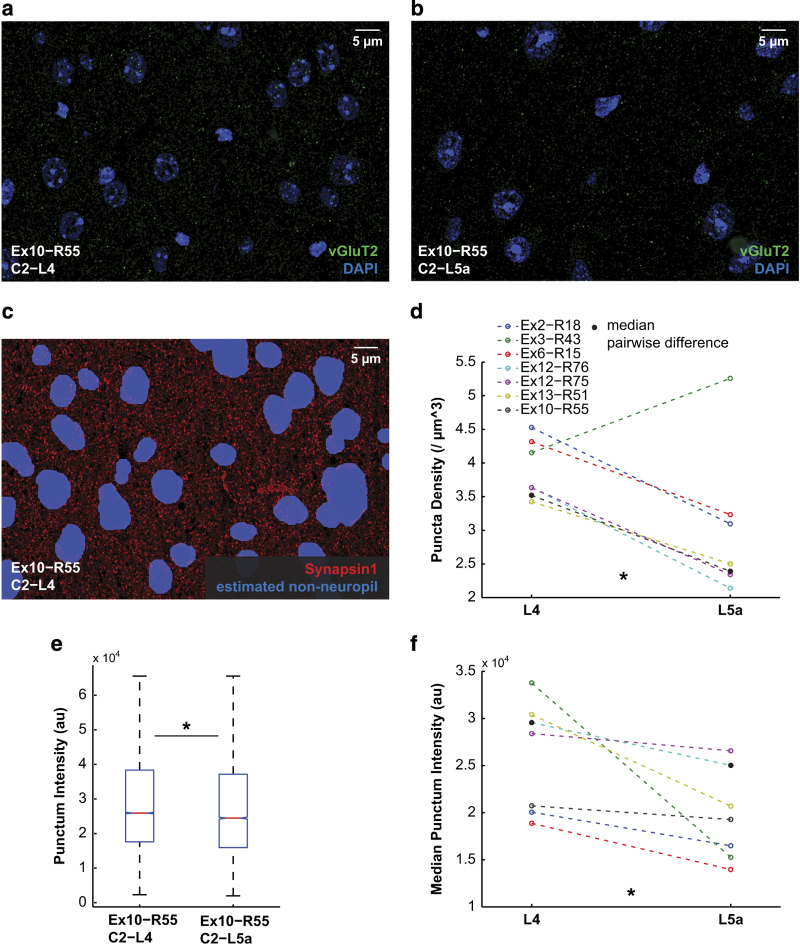

These pairwise cross-correlations demonstrated sharp central peaks for colocalized antibodies, and broader noisier values for poorly colocalized antibodies. Examining the cross-correlations at small 2d shifts between images reveals that pairs of antibodies which are expected to colocalize within either pre- or postsynaptic compartments (for example, Synapsin1 and vGluT1 or PSD95 and GluR2, respectively) have sharp peaks of correlation, while pairs of antibodies which represent associated pre- and postsynaptic compartments (for example, Synapsin1 and PSD95) have broader, more diffuse cross-correlation peaks (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Validation of synaptic antibody colocalization.

(a–c) Multi-channel composite images of related synaptic protein stains in a subregion of a single serial section of the Ex10-R55 ribbon. Scale bar 5 um. (d–g) 2-dimensional cross-correlation analysis of the colocalization of antibody stains specific to the pre- and postsynaptic compartments of glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses. Each plot contains an array of panels representing correlation between different stains of a subregion of the Ex10-R55 ribbon as a function of spatial shifts in x and y (shifts up to 10 px shown), averaged over stacks of 10 serial sections. (a,d) Colocalization of stains for presynaptic glutamatergic proteins (Synapsin1, vGluT1 and vGluT2) and comparison with postsynaptic PSD95 and nuclear DAPI stains. (b,e) Colocalization of stains for postsynaptic glutamatergic proteins (PSD95, GluR1, GluR2, NR2A and NR2B) and comparison to nuclear DAPI stain. (c,f) Colocalization of stains for presynaptic (Synapsin1, vGAT, GAD, and PV25) and postsynaptic (GABAARa1 and Gephyrin) GABAergic proteins and comparison with nuclear DAPI stain. (g) Colocalization of glutamatergic and GABAergic vesicular neurotransmitter transporters (vGluT1, vGluT2, vGAT) relative to presynaptic marker Synapsin1, postsynaptic markers PSD95 (glutamatergic) and gephyrin (GABAergic), and DAPI-stained cell nuclei.

To quantify these correlations, we measured the absolute peak of the cross-correlation, and calculated a half-maximum value based on the average background correlation. Using Matlab, we also calculated a 2d contour of the cross-correlation peak at the half-maximum value, and measured the area of this contour and calculated the diameter of a circular contour with the same area. These values are displayed in Table 9.

Table 9. Antibody Colocalization.

| Correlation Peak (r) | Synapsin1 | vGluT1 | vGluT2 | PSD95 | GluR1 | GluR2 | NR2A | NR2B | GAD2 | vGAT | Gephyrin | GABAARa1 | PV25 | DAPI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| We performed a pairwise 2-dimensional cross-correlation analysis to quantify spatial correlations (colocalization) between the principal antibodies used in these experiments This table displays 2-d cross-correlation peak, half-max contour area, and equivalent circular diameter values for each pairwise combination of antibodies. (See Technical Validation: Antibody Specificity; Figure 3). | ||||||||||||||

| Synapsin1 | 0.394 | 0.127 | 0.025 | 0.033 | 0.017 | 0.024 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.050 | 0.018 | 0.002 | 0.007 | −0.003 | −0.012 |

| vGluT1 | 0.127 | 0.394 | 0.026 | 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.016 | 0.002 | 0.025 | 0.033 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| vGluT2 | 0.025 | 0.026 | 0.394 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.004 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.008 | 0.013 | 0.017 |

| PSD95 | 0.033 | 0.020 | 0.011 | 0.394 | −0.002 | 0.079 | 0.011 | 0.043 | 0.003 | −0.005 | 0.001 | 0.004 | −0.005 | −0.006 |

| GluR1 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.394 | 0.018 | 0.041 | 0.051 | 0.074 | 0.148 | 0.056 | 0.075 | 0.020 | 0.003 |

| GluR2 | 0.024 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.079 | 0.018 | 0.394 | 0.016 | 0.033 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.033 | 0.004 | 0.018 |

| NR2A | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.041 | 0.016 | 0.394 | 0.038 | 0.006 | 0.038 | 0.076 | 0.066 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| NR2B | 0.013 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 0.043 | 0.051 | 0.033 | 0.038 | 0.394 | 0.010 | 0.036 | 0.042 | 0.066 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| GAD2 | 0.050 | 0.033 | −0.002 | 0.003 | 0.074 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.394 | 0.079 | 0.018 | 0.031 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| vGAT | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.005 | 0.148 | 0.017 | 0.038 | 0.036 | 0.079 | 0.394 | 0.054 | 0.079 | 0.029 | 0.004 |

| Gephyrin | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.032 | 0.001 | 0.056 | 0.018 | 0.076 | 0.042 | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.394 | 0.091 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| GABAARa1 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.075 | 0.033 | 0.066 | 0.066 | 0.031 | 0.079 | 0.091 | 0.394 | 0.014 | 0.013 |

| PV25 | −0.003 | 0.005 | 0.013 | −0.005 | 0.020 | 0.004 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.009 | 0.029 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.394 | 0.012 |

| DAPI | −0.012 | 0.001 | 0.017 | −0.006 | 0.003 | 0.018 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.394 |

|

Contour Area (px^2)

|

||||||||||||||

| Synapsin1 | 5.77 | 9.13 | 8.82 | 19.78 | 9.22 | 14.59 | 125.38 | 15.25 | 8.81 | 9.57 | 16.48 | 13.69 | 318.64 | 156.17 |

| vGluT1 | 9.12 | 5.69 | 7.63 | 21.81 | 21.50 | 16.59 | 11.57 | 9.49 | 6.96 | 8.37 | 352.89 | 13.80 | 5.12 | 21.95 |

| vGluT2 | 8.76 | 7.63 | 5.36 | 9.61 | 388.84 | 10.56 | 11.79 | 10.71 | 30.38 | 131.79 | 7.87 | 12.46 | 9.54 | 36.26 |

| PSD95 | 19.71 | 21.76 | 9.61 | 3.96 | 35.87 | 6.72 | 7.04 | 6.47 | 14.42 | 20.83 | 28.25 | 7.22 | 21.55 | 38.20 |

| GluR1 | 9.17 | 62.60 | 219.17 | 35.79 | 5.07 | 14.35 | 11.85 | 8.70 | 10.32 | 8.11 | 14.38 | 11.88 | 12.06 | 397.91 |

| GluR2 | 14.54 | 16.54 | 10.53 | 6.72 | 14.37 | 4.80 | 15.18 | 9.18 | 14.41 | 13.98 | 15.45 | 13.44 | 20.89 | 32.03 |

| NR2A | 82.12 | 10.79 | 11.85 | 7.03 | 11.88 | 15.11 | 2.73 | 11.00 | 24.73 | 11.37 | 8.55 | 12.00 | 15.47 | 67.40 |

| NR2B | 15.11 | 9.46 | 10.72 | 6.46 | 8.69 | 9.17 | 11.02 | 4.03 | 18.66 | 10.05 | 12.94 | 10.21 | 455.36 | 247.07 |

| GAD2 | 8.77 | 6.93 | 29.41 | 1.75 | 10.34 | 14.33 | 24.84 | 18.63 | 5.31 | 10.64 | 22.54 | 15.21 | 12.65 | 30.15 |

| vGAT | 9.51 | 208.44 | 14.48 | 20.92 | 8.12 | 13.90 | 11.36 | 10.05 | 10.62 | 5.17 | 14.68 | 11.53 | 11.63 | 160.51 |

| Gephyrin | 15.86 | 251.98 | 7.86 | 59.59 | 14.38 | 15.40 | 8.53 | 12.91 | 22.43 | 14.65 | 5.00 | 11.68 | 38.20 | 101.67 |

| GABAARa1 | 13.57 | 13.19 | 12.57 | 7.17 | 11.86 | 13.36 | 11.98 | 10.18 | 15.16 | 11.52 | 11.70 | 5.42 | 13.70 | 114.35 |

| PV25 | 286.11 | 5.03 | 9.57 | 21.89 | 12.09 | 20.39 | 114.91 | 69.03 | 12.68 | 11.65 | 37.09 | 13.77 | 5.18 | 72.26 |

| DAPI | 145.74 | 22.59 | 37.12 | 35.12 | 288.63 | 32.59 | 78.27 | 321.33 | 29.96 | 304.59 | 26.77 | 116.32 | 73.49 | 18.00 |

|

Contour Diameter (px)

|

||||||||||||||

| Synapsin1 | 2.71 | 3.41 | 3.35 | 5.02 | 3.43 | 4.31 | 12.64 | 4.41 | 3.35 | 3.49 | 4.58 | 4.18 | 20.14 | 14.10 |

| vGluT1 | 3.41 | 2.69 | 3.12 | 5.27 | 5.23 | 4.60 | 3.84 | 3.48 | 2.98 | 3.26 | 21.20 | 4.19 | 2.55 | 5.29 |

| vGluT2 | 3.34 | 3.12 | 2.61 | 3.50 | 22.25 | 3.67 | 3.87 | 3.69 | 6.22 | 12.95 | 3.17 | 3.98 | 3.49 | 6.79 |

| PSD95 | 5.01 | 5.26 | 3.50 | 2.25 | 6.76 | 2.92 | 2.99 | 2.87 | 4.28 | 5.15 | 6.00 | 3.03 | 5.24 | 6.97 |

| GluR1 | 3.42 | 8.93 | 16.71 | 6.75 | 2.54 | 4.27 | 3.88 | 3.33 | 3.63 | 3.21 | 4.28 | 3.89 | 3.92 | 22.51 |

| GluR2 | 4.30 | 4.59 | 3.66 | 2.93 | 4.28 | 2.47 | 4.40 | 3.42 | 4.28 | 4.22 | 4.43 | 4.14 | 5.16 | 6.39 |

| NR2A | 10.23 | 3.71 | 3.88 | 2.99 | 3.89 | 4.39 | 1.87 | 3.74 | 5.61 | 3.81 | 3.30 | 3.91 | 4.44 | 9.26 |

| NR2B | 4.39 | 3.47 | 3.70 | 2.87 | 3.33 | 3.42 | 3.75 | 2.27 | 4.87 | 3.58 | 4.06 | 3.60 | 24.08 | 17.74 |

| GAD2 | 3.34 | 2.97 | 6.12 | 1.49 | 3.63 | 4.27 | 5.62 | 4.87 | 2.60 | 3.68 | 5.36 | 4.40 | 4.01 | 6.20 |

| vGAT | 3.48 | 16.29 | 4.29 | 5.16 | 3.21 | 4.21 | 3.80 | 3.58 | 3.68 | 2.56 | 4.32 | 3.83 | 3.85 | 14.30 |

| Gephyrin | 4.49 | 17.91 | 3.16 | 8.71 | 4.28 | 4.43 | 3.30 | 4.06 | 5.34 | 4.32 | 2.52 | 3.86 | 6.97 | 11.38 |

| GABAARa1 | 4.16 | 4.10 | 4.00 | 3.02 | 3.89 | 4.12 | 3.91 | 3.60 | 4.39 | 3.83 | 3.86 | 2.63 | 4.18 | 12.07 |

| PV25 | 19.09 | 2.53 | 3.49 | 5.28 | 3.92 | 5.10 | 12.10 | 9.38 | 4.02 | 3.85 | 6.87 | 4.19 | 2.57 | 9.59 |

| DAPI | 13.62 | 5.36 | 6.87 | 6.69 | 19.17 | 6.44 | 9.98 | 20.23 | 6.18 | 19.69 | 5.84 | 12.17 | 9.67 | 4.79 |

Antibody consistency

In previously published work, we demonstrated that multiple rounds of elution have minimal effect on tissue antigenicity as quantified by the consistency of staining with an antibody against Synapsin1 across multiple rounds of imaging9. In the present datasets, we also observed comparable staining quality irrespective of the multiple rounds of stripping and staining.

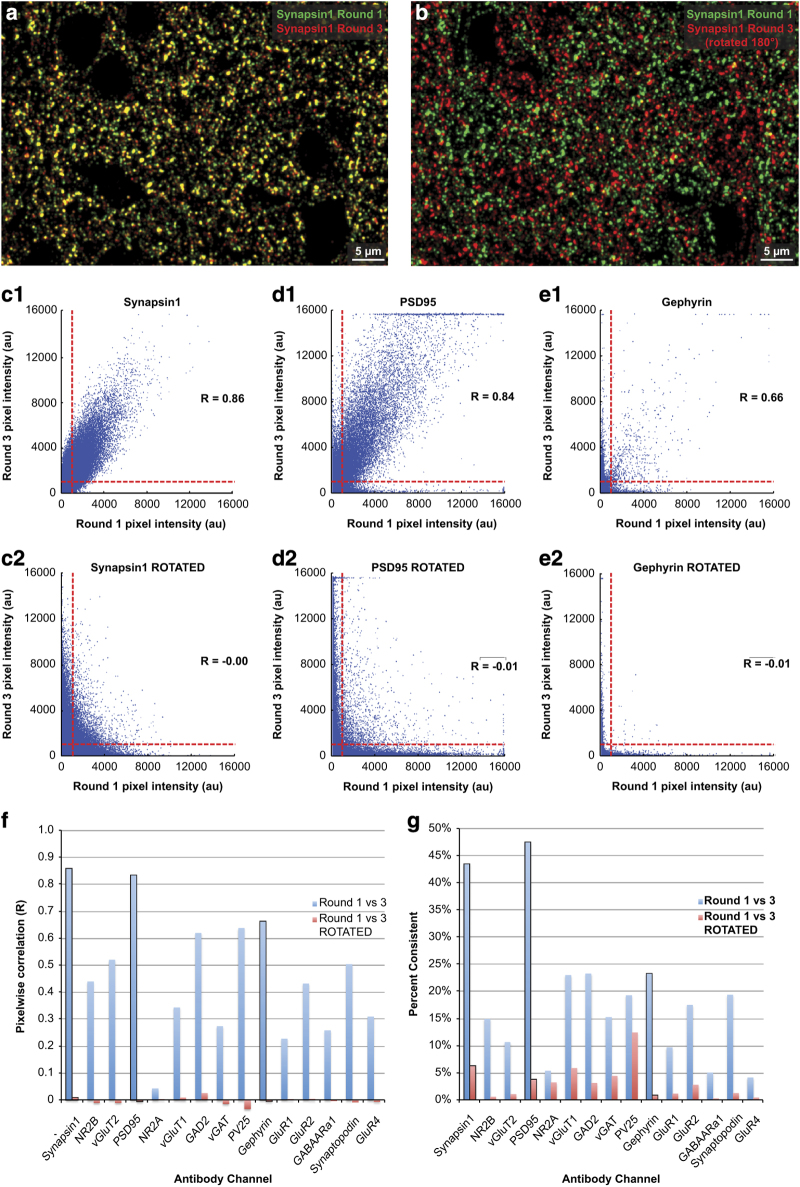

To further test the consistency of our staining procedure, we have performed three rounds of repeated staining with fifteen key antibodies on ribbons equivalent to those used to produce the Chessboard Dataset. We used 2d image correlation to assess the similarity of staining between the first and third rounds of imaging for each antibody (Figure 4a,c1,e1,g1). To compare the observed level of correlation to a proxy for ‘random’ colocalization, we rotated the images of the third imaging session 180° and repeated the analysis (Figure 4b,c2,e2,g2).

Figure 4. Evaluation of stain robustness across imaging sessions.

(a) False-color composite image comparing the first stain of a subregion of ribbon Ex1-R02A with an antibody against Synapsin1 protein (green) with the third sequential stain of the same region (red). Areas of overlap (yellow) represent consistent patterns of staining despite intervening rounds of stripping and restaining. (b) Here the image of the third round of staining has been rotated 180° to illustrate that the chance occurrence of overlapping staining is quite low, despite the high stain density in the two images. (c1) Synapsin1 immunofluorescence intensity at individual pixels compared between rounds 1 and 3. The R value represents Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the two images. An approximate threshold between foreground and background pixels (set at 1,000 a.u.) in each image is illustrated by horizontal and vertical red dashed lines. (c2) The same analysis with the image of round 3 rotated 180° to serve as a control for random colocalizations. (d,e) The same analyses for PSD95 and Gephyrin staining. (f) Comparison of correlation coeffients (R) for images of the first and third round of staining for 15 different antibodies. (g) For the same set of antibody stains, comparison of the ‘percent consistency’: the percent of pixels that were bright (above threshold) in either imaging session which were also bright in the other imaging session. See Table 10 for a full list of these values.

Since the large proportion of dark background pixels could be contributing significantly to these image correlations, we also computed a ‘percent consistent’ metric that measured the proportion of bright pixels that were bright in both images. We set an approximate threshold between foreground and background at 1,000 a.u., and quantified the proportion of pixels above this threshold in either imaging session that were also above threshold in the other imaging session. As with the correlation metric, we compared this ‘percent consistent’ metric between the observed colocalization and the ‘random’ colocalization achieved by rotating one image 180° (Figure 4g). This pixelwise metric is only a rough quantification of antibody consistency, but it provides a simple supplement to the correlation values described above.

We find that the antibodies against Synapsin1 and PSD95 produce highly consistent staining between sessions, while the rest (with the exception of NR2A) ranged from relatively good to relatively poor consistency, when compared with the extremely low values expected by random colocalization (Figure 4f,g, Table 10). This analysis corresponds well with previous unpublished observations by our lab, and suggests that each antibody channel represents a mixture of robust signal and stochastic variability, with a signal-to-noise ratio that varies between antibodies.

Table 10. Staining Robustness to Strip-Stain Cycles.

| Antibody Name | R | R (rotated) | % Consistent | % Consistent (rotated) | Background % Consistent | Background % Consistent (rotated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|