Abstract

Background: after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, inactivity and the homebound status of older victims in affected areas have been a serious public health concern owing to the victims' prolonged existence as evacuees in mountainous areas.

Objective: to evaluate the association between distances to retail stores and risks of being homebound.

Design: secondary analysis of cross-sectional interview survey data with a geographical information analysis.

Setting: Rikuzentakata, Iwate, a municipality seriously damaged by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

Subjects: all Rikuzentakata residents aged 65 or older except for those living in temporary housing (n = 2,327).

Methods: we calculated road distances between each residential address and retail stores, hawker sites and shopping bus stops, accounting for the extra load caused by walking on slopes. The prevalence ratio of being homebound adjusted for age, source of income and morbidity by road distance was estimated using Poisson regression with a generalised estimating equation.

Results: those living at distances of 1,200 m or more were 1.78 (95% confidence intervals, 1.03–3.08) times more likely to be homebound (going out only every 4 or more days a week) among men and 1.85 (1.13-3.02) among women, compared with those residing in places <400 m from retail stores or shopping bus stops. The distances were reduced by new hawker and shopping bus services, but the improvements varied greatly across the districts.

Conclusions: access to daily needs is essential to prevent homebound status. Post-disaster community diagnosis in terms of the built environment is important for strategic community restoration.

Keywords: older people, built environment, disaster, homebound, Japan

Introduction

On 11 March 2011, the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred, and a massive tsunami with a maximum wave height of 40 m caused destruction to many cities along 500 km of Japan's north-eastern coast; it directly killed 15,882 people and 2,668 individuals are still missing [1]. The recovery process has been slow owing to the overwhelming scale of the damage. After the disaster, people who originally resided in tsunami-hit coastal areas and many affected cities evacuated to other cities or nearby areas in the mountains. In the affected cities, access to such places as retail stores and the availability of public and business services worsened. Those access barriers probably increased the risk of older evacuees becoming physically and social inactive. One survey reported that 30% of respondents cited poor access to transportation as the prime reason for not going out; this was followed by a lack of purpose or places to go (16%) and a lack of motivation to go out (16%) [2].

Numerous studies have reported that among older adults, physical and social inactivity in addition to homebound status are important risk factors for functional decline and death [3–8]. In particular, the homebound lifestyle of older adults has been an area of serious public health concern [1]. However, the effects of access difficulties on older adults' inactivity after the 2011 disaster have not been studied.

The purpose of this study was, therefore, to evaluate the effect of the built environment in terms of physical access to retail stores on older adults' inactivity in a city severely affected by the disaster. We focused on retail stores (including grocery stores, convenience stores, supermarkets and shopping centres), because shopping has been identified as a primary reason for going out in the daily lives of older Japanese adults: a national representative survey reported that 66.2% of older respondents selected ‘shopping’ as their main reason for going out [5].

Methods

Data

Rikuzentakata, the site of this study, was one of the cities most seriously damaged by the disaster: of its total population of 23,302 before the catastrophe, 1,773 people died or are still missing. Like many cities affected by that tsunami, Rikuzentakata is a rural area, and it had a highly aged population before the disaster: 34.9% of its population was aged 65 years or over in 2010 [9].

Forest accounted for 80.6% of the total land area, and most areas of flat land were located by the coast or around river estuaries (see Supplementary data, Appendix Table S1 available in Age and Ageing online). Before the earthquake, the population was concentrated in the flat coastal areas. Of 7,730 houses, 3,368 (43.6%) were affected by the disaster and 3,159 were ‘completely destroyed’ [9]. Since the community infrastructure in the flat areas was also totally shattered, many victims who lost their houses insisted on moving to areas in the mountains (Figure 1) [10].

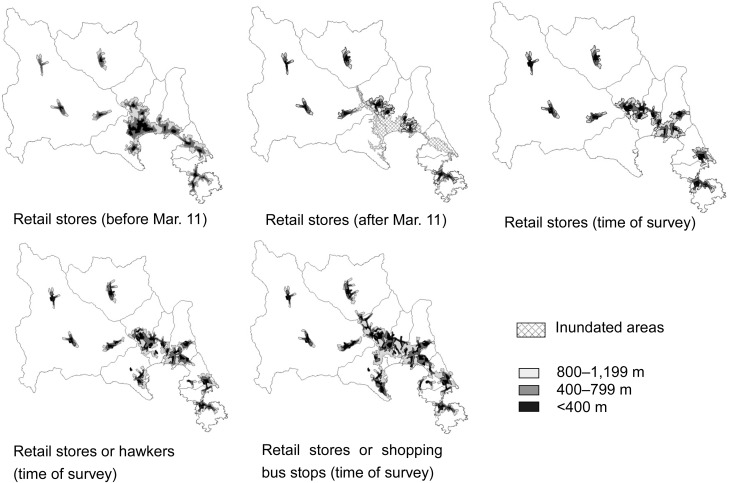

Figure 1.

Road distance areas from retail stores, hawker sites and shopping bus stops before the earthquake (on 11 March 2011), just after the earthquake and the time the survey started (August 2012).

We used the data of the third wave of the Health and Living Condition Survey conducted by the Rikuzentakata city government. The home-visit interview survey was carried out from August 2012 to October 2013 among all residents of 6,027 households on the resident registry. Individuals living in temporary housing as earthquake victims were not surveyed, because those individuals had been previously surveyed. Among them, 3,855 households responded to the interviews (response rate = 64.0%). Interviewers gathered information on current morbidity, socio-economic status, health behaviour (eating meals and snacks, smoking status and amount of alcohol consumed per day), frequency of going out and social support. Of 11,370 respondents in total, we used the data of 4,149 people who were 65 years or older. We eventually employed the data of 2,327 older adults with the necessary information for this analysis, including accurate residential address.

Geographical information

We obtained information on grocery stores, convenience stores and shopping centres from the online community directory database Town Page (NTT data, Tokyo, Japan) in August 2012. We removed data relating to facilities in the areas directly hit by the tsunami. Information on shopper bus stops and hawker sites was provided by the disaster support team of Iwate Prefecture Consumer Cooperative. We used ArcGIS data collection (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA) for road network data; where road information was lacking, we referred to road data of digital national land information [11]. Using these data, we calculated three distances related to road networks: the distance to the nearest retail stores; distance to retail stores or hawker sites and distance to retail stores or shopper bus stops. Following the study by Satoh et al. [12], we assumed that going uphill and downhill require extra effort to move and we penalised slope angles on the road by putting a weight of

on the surface road distance, where θ represents the slope angle. Slope angle data were obtained from the 10 m mesh altitude data of digital national land information. The data were linked to road data using geographical information systems.

Measurements

Dependent variables: homebound

Following recent reviews, homebound status was determined by the frequency of going out [4]. Respondents were asked about the frequency of going out, and the response options were as follows: (i) daily; (ii) once every 2 or 3 days; (iii) once every 4 or 5 days and (iv) less than that (i.e. once every 6 days or more). We dichotomised the responses and determined those who went out once every 4 or more days as homebound.

Explanatory variables

Our main explanatory variables were road distances from the residential addresses to retail stores (including small grocery stores, convenience stores and supermarkets), hawker sites and shopping bus stops. After the earthquake, private stores and consumer cooperatives started hawker sales for people residing in regular or temporary housing located in remote areas. Shopping bus services were also improved, covering wider areas than before the earthquake. Shopping buses take passengers to a shopping area located in the city centre for free.

Co-variates

As potential confounding factors, we used age, morbidity (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, heart diseases, brain diseases, cancers, orthopaedic disorders, psychiatric disorders, asthma, allergic diseases and other conditions), types of income (pension, wage, none and other) and availability of contact with neighbours (yes or no).

Statistical analysis

Geographical information analysis

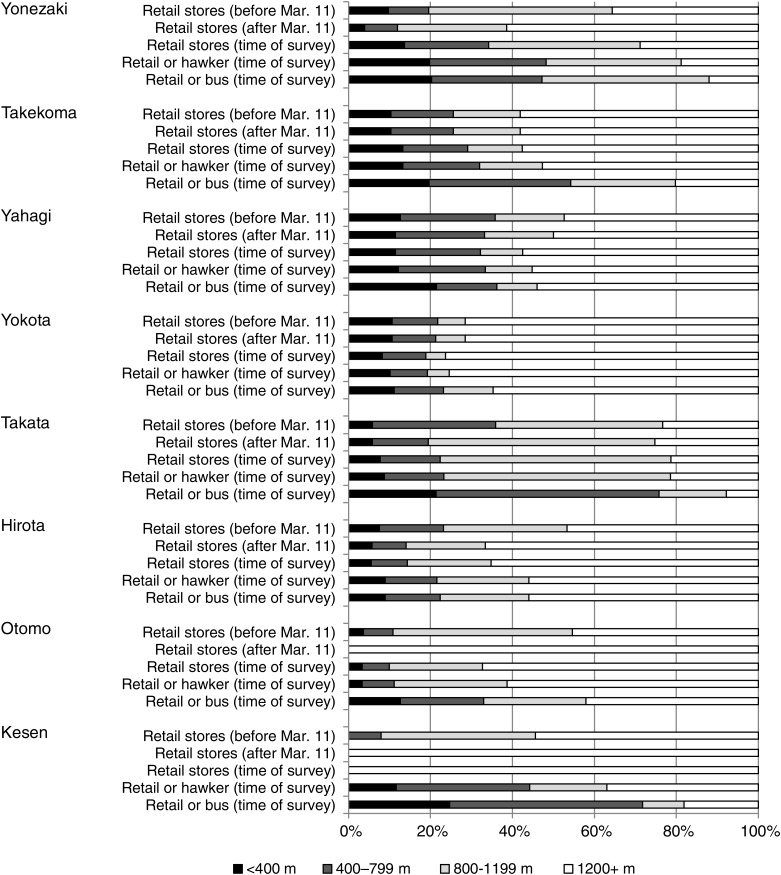

The calculated road distances were divided into four categories: <400 m, 400–799 m, 800–1,199 m and 1,200 m or more. First, we visually evaluated the changes in the areas covered by those road distances. We then calculated the population coverage for the road distances to retail stores, hawker sites or bus stops in terms of eight districts. For this, we used the geographical information systems software ArcGIS.

Epidemiological analysis

We then linked the results of the geographical information analysis to the survey data. We first evaluated the prevalence of homebound status according to the respondents' socio-demographic status, district of residence and distance to retail stores or shopping bus stops. Then, we used Poisson regression with a log link function to evaluate the association between those distances and the risks for homebound status, considering potential confounding factors. We separately created three models using the distances to the nearest retail store (Model 1), retail store or hawker site (Model 2) and retail store or shopping bus stop (Model 3). To address clustering within households, we used the generalised estimating equation (GEE) technique. All analyses were categorised by gender. The GEE was required, despite the gender stratification, because there were some addresses at which more than one older couple resided. We employed SPSS version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) for the analysis. All P values were two-tailed.

Results

Geographical analysis

As expected, most of the retail stores, hawker sites and shopping bus stops were in areas that had not been reached by the tsunami (see Supplementary data, Appendix Figures S1 and S2 available in Age and Ageing online). The geographical distribution of the road distances to retail stores, hawker sites and shopping bus stops dramatically changed before and after the earthquake (Figure 1). The coverage of populations within a certain road distance to those facilities also underwent a major change (Figure 2). Baseline coverage and the degree of changes varied across districts. Just after the earthquake in Yonezaki, Otomo and Kesen districts, the distances to retail stores largely increased. In the latter two districts, all residential addressees were 1,200 m or more from the nearest retail store. In Otomo, however, the re-opening of a new shopping centre, previously located in a tsunami-affected coastal area, contributed to the increased coverage of areas that were less distant to retail stores (32.7% of residential addresses were within 1,200 m of the nearest retail store). In Kesen, although no retail stores opened afterward and the distance to the nearest retail store did not change, the distance to retail stores, hawker sites or shopping bus stops largely decreased owing to newly introduced hawker and shopping bus services.

Figure 2.

Population coverage by the road distances to retail stores, hawker sites and shopping bus stops by district and by period (before March 2011; just after March 2011 and time of survey started, August 2012).

Epidemiological analysis

Among the 2,327 participants, 1,027 (44.1%) were men and 1,300 were women (55.9%), with average ages of 75.5 and 77.2 years, respectively. Overall, the proportions of homebound people were 19.6% for men and 23.2% for women, with higher proportions in the older age groups. There was an over 3-fold regional difference across the eight districts—from 7.9% among women in Kesen to 34.8% among women in Yokota. Linking geographical information with survey data, we found that people residing at greater distance from retail stores, hawker sites or bus stops were likely to be homebound (see Supplementary data, Appendix Table S2 available in Age and Ageing online).

Overall, the GEE–Poisson regression showed a positive association between road distances to retail stores or shopping bus stops and the risk of being homebound. For example, among men, the adjusted prevalence ratio (PR) for homebound status among those whose residential address was 1,200 m or more from the nearest retail store or hawker site compared with <400 m was 1.40 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.96–2.04); the adjusted PR was 1.78 (95% CI, 1.03–3.08) for those living 1,200 m or more from the nearest retail store or shopping bus stop. These associations were comparable in all the models for women, though women rather showed narrower CIs and smaller P values (the P values for women in the >1,200 m category were <0.05 in all models) (see Supplementary data, Appendix Table S3 available in Age and Ageing online for full descriptions of those models; Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence ratios for being homebound by road distance to nearest retail store, hawker site or shopping bus stop after the Great East Japan Earthquake, 11 March 2011, in the city of Rikuzentakata, 2012–13

| Men |

Women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | PR (95% CI) | P | n | PR (95% CI) | P | |

| Model 1: to retail store | ||||||

| −399 m | 92 | 1 | 104 | 1 | ||

| 400–799 m | 126 | 1.30 (0.71–2.37) | 0.40 | 183 | 1.28 (0.75–2.18) | 0.37 |

| 800–1,199 m | 219 | 1.39 (0.80–2.42) | 0.24 | 250 | 1.36 (0.82–2.25) | 0.24 |

| 1,200+ m | 590 | 1.39 (0.83–2.30) | 0.21 | 763 | 1.54 (0.97–2.44) | 0.07 |

| Model 2: to retail store or hawker site | ||||||

| −399 m | 124 | 1 | 138 | 1 | ||

| 400–799 m | 170 | 0.99 (0.63–1.55) | 0.96 | 244 | 0.94 (0.64–1.37) | 0.74 |

| 800–1,199 m | 238 | 1.23 (0.79–1.89) | 0.36 | 277 | 1.45 (1.02–2.05) | 0.04 |

| 1,200+ m | 495 | 1.40 (0.96–2.04) | 0.07 | 641 | 1.45 (1.05–2.00) | 0.02 |

| Model 3: to retail store or shopping bus stop | ||||||

| −399 m | 176 | 1 | 205 | 1 | ||

| 400–799 m | 220 | 1.18 (0.59–2.35) | 0.63 | 305 | 1.33 (0.75–2.36) | 0.33 |

| 800–1,199 m | 228 | 1.49 (0.81–2.74) | 0.20 | 282 | 1.73 (1.02–2.95) | 0.04 |

| 1,200+ m | 403 | 1.78 (1.03–3.08) | 0.04 | 508 | 1.85 (1.13–3.02) | 0.01 |

All models were adjusted for age, sources of income, morbidity and available contacts/neighbours.

Discussion

Our analysis found that, even after controlling for age, income status, mental and physical health status (morbidity) and social integration, the older men and women residing at great distance from shopping facilities were more likely to be homebound or not go out frequently; however, the association between distance and homebound status was not clear for those with a road distance of under 800 m. Although the distance to shopping facilities may be a risk of being homebound, the newly started shopping bus and hawker services in Rikuzentakata may have provided more opportunities for going out.

Potential reasons for the positive association between distance to retail stores or shopping support services and going out infrequently are as follows. (i) The distance itself is a physical barrier to going out. (ii) The distance may also be a psychosocial barrier—giving rise to feelings of being neglected or excluded from society, which may in turn reduce the willingness for going out. (iii) It is also possible that some people who reside in distant areas from those shopping destinations may not need to go out, because they have sufficient instrumental support for obtaining daily necessities through, for example, their children or younger neighbours.

To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the association between distances to certain facilities in a built environment and the risk of homebound status of older adults. The strengths of this study were utilising the data of a home-visit survey for all people who resided in their own or rented accommodation as well as detailed, objective geographical information. The accurate information on distances relating to road networks is another advantage. Nonetheless, a major limitation of this study is that we did not account for the means of transportation. Some people may use motor vehicles, potentially leading to the underestimation of the association between road distance and their inactiveness. This may explain the gender differences observed, with more precise estimates being obtained for women than men. In Japan, older women are less likely to drive a car and possess a licence; misclassification may thus be smaller among women. Another issue is the self-reported, limited information obtained from the survey: this raises the possibility of potential information biases and residual confounding. Inactivity may be influenced by unmeasured factors, including instrumental social support, educational attainments and neighbourhood environment [13–17]. Responses to the frequency of going out may be influenced by the lifestyles and perceptions of respondents. For example, some persons may regard going to a field next to their houses as going out, but others may not. We do not know whether this factor may have systematically caused a misclassification. Moreover, the generalisability of the results is limited, as the data did not include the residents of temporary housing and other earthquake-damaged areas.

Recent studies have reported the link between neighbourhood environment and physical activity of older adults, including the association with self-rated health [18, 19] and more objective health measures [20–23]. However, these studies used road or community information in the form of small-area data, such as census collection districts, not the geographical information of total road networks. Among the few exceptions was the study by Hanibuchi et al. [24], which evaluated road distances using total road network data and identified the positive association between road distances and physical activities, such as leisure-time sports activity. Our analysis represents an advance in terms of additionally accounting for the physical load due to road slopes; it provides more realistic calculations of road distances, which are particularly important when evaluating neighbourhood environments in mountainous areas.

This study has important implications for public health, especially in the setting of post-disaster community reconstruction. First, community diagnosis in a post-disaster setting should cover the built environment, including access to shopping facilities. Second, to prevent homebound status of older victims, it is clearly essential to provide access to the facilities that fulfil their daily needs. Given the findings of this study, such access could be increased by the private sector, suggesting the importance of public–private partnerships for post-disaster reconstruction. The results of this study may be used directly to design community recovery plans for Rikuzentakata. Because many rural municipalities affected by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami have similar backgrounds and challenges, the results of this study can be generalised to those other areas.

Key points.

The homebound status of older victims of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake is a matter of concern.

Geographical analysis indicated that distances to retail stores were associated with the risk of homebound status.

Hawker and shopping bus services contributed to improved access, providing more opportunities for going out.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare, Japan (No. H25-iryou-shitei-003).

Ethical approval

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Board of The University of Tokyo Faculty of Medicine (No. 10197).

Authors’ contributions

H.H. developed the ideas of this study, analysed the data and drafted. N.K. contributed to the management of research group, conceptualisation, data analysis and drafting. R.S., S.I., H.M., R.O. and K.S. contributed to data acquisition and intensively participated in improving analysis and manuscript.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text are available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of Rikuzentakata Healthcare and Welfare Recovery Future Plans Meeting for their valuable comments for our draft.

References

- 1.Ishigaki A, Higashi H, Sakamoto T, Shibahara S. The Great East-Japan Earthquake and devastating tsunami: an update and lessons from the past great earthquakes in Japan since 1923. Tohoku J Exp Med 2013; 229: 287–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kondo N. Results of health and living condition survey for older adults in the recovery period of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. Geriatr Med 2013; 52: 147–51 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branch LG, Wetle TT, Scherr PA, et al. A prospective study of incident comprehensive medical home care use among the elderly. Am J Public Health 1988; 78: 255–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert GH, Branch LG, Orav EJ. An operational definition of the homebound. Health Serv Res 1992; 26: 787–800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cabinet Office of Japan. Results of Survey on the Senior Citizens’ Attitude Toward Housing and the Living Environment for FY 2005. Tokyo, Japan: Director General for Policies on Cohesive Society, Cabinet Office of Japan, 2006. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shinkai S, Kumagai S, Fujiwara Y, et al. Predictors for the onset of functional decline among initially non-disabled older people living in a community during a 6-year follow-up. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2003; 3: S31–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strobl R, Muller M, Emeny R, Peters A, Grill E. Distribution and determinants of functioning and disability in aged adults - results from the German KORA-Age study. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, Bula CJ, Hohmann C, Beck JC. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med 1999; 48: 445–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The City of Rikuzentakata. The City of Rikuzentakata Official Website. The City of Rikuzentakata, 2014. http://www.city.rikuzentakata.iwate.jp/ (10 March 2014, date last accessed).

- 10.Center for Spatial Information Science, at the University of Tokyo. Archive of Recovery Support Survey [cited 2014 3.10]. http://fukkou.csis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ (10 March 2014, date last accessed).

- 11.Fundamental Geospatial Data. [database on the Internet]. Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. 2014. http://www.gsi.go.jp/kiban (10 March 2014, date last accessed).

- 12.Satoh E, Yoshikawa T, Yamada A. Investigation of converted walking distance considering resistance of topographical features and changes in physical strength by age. J Architectural Plann Res 2006; 610: 133–9 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murayama H, Fujiwara Y, Kawachi I. Social capital and health: a review of prospective multilevel studies. J Epidemiol 2012; 22: 179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kagamimori S, Gaina A, Nasermoaddeli A. Socioeconomic status and health in the Japanese population. Soc Sci Med 2009; 68: 2152–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furuya Y, Kondo N, Yamagata Z, Hashimoto H. Health literacy, socioeconomic status, and self-rated health in Japan. Health Promot Int 2013; doi:10.1093/heapro/dat071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon JR, Kondo N, Glymour MM, Subramanian SV. Widowhood and mortality: a meta-analysis. PLos One 2011; 6: e23465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondo N, Kawachi I, Hirai H, et al. Relative deprivation and incident functional disability among older Japanese women and men: prospective cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009; 63: 461–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue S, Ohya Y, Odagiri Y, et al. Association between perceived neighborhood environment and walking among adults in 4 cities in Japan. J Epidemiol 2010; 20: 277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murayama H, Yoshie S, Sugawara I, Wakui T, Arami R. Contextual effect of neighborhood environment on homebound elderly in a Japanese community. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2012; 54: 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H. The effect of homebound status on older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58: 2358–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan MJ, Winkler E, Sugiyama T, et al. Relationships of land use mix with walking for transport: do land uses and geographical scale matter? J Urban Health 2010; 87: 782–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leslie E, Coffee N, Frank L, Owen N, Bauman A, Hugo G. Walkability of local communities: using geographic information systems to objectively assess relevant environmental attributes. Health Place 2007; 13: 111–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webb E, Netuveli G, Millett C. Free bus passes, use of public transport and obesity among older people in England. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011; doi:10.1136/jech.2011.133165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanibuchi T, Kawachi I, Nakaya T, Hirai H, Kondo K. Neighborhood built environment and physical activity of Japanese older adults: results from the Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES). BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.