Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the current quality “assurance” and “improvement” mechanisms, the knowledge, attitudes and practices of cataract surgeons in a large South African city.

Methodology:

A total of 17 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with ophthalmologists in June 2012 at 2 tertiary institutions in the Republic of South Africa. Recruitment of the purposive sample was supplemented by snowball sampling. The study participants were 5 general ophthalmologists and 2 pediatric ophthalmologists; 4 senior and 4 junior registrars and a medical officer. Participants were interviewed by a trained qualitative interviewer. The interview lasted between 20 and 60 min. The interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim and analyzed for thematic content.

Results:

Mechanisms for quality assurance were trainee logbooks and subjective senior staff observation. Clinicians were encouraged, but not obliged to self-audit. Quality improvement is incentivized by personal integrity and ambition. Poorly performing departments are inconspicuous, especially nationally, and ophthalmologists rely on the impression to gauge the quality of service provided by colleagues. Currently, word of mouth is the method for determining the better cataract surgical centers.

Conclusion:

The quality assurance mechanisms were dependent on insight and integrity of the individual surgeons. No structures were described that would ensure the detection of surgeons with higher than expected complication rates. Currently, audits are not enforced, and surgical outcomes are not well monitored due to concerns that this may lead to lack of openness among ophthalmologists.

Keywords: Blindness Prevention, Cataract Surgery, Monitoring, Quality, Vision 2020

INTRODUCTION

Currently, there is a concerted effort towards increasing the number of cataract surgery procedures. This increase in the volume of procedures is driven by the targets for cataract surgical rates in achieving the goals of vision 2020. However, concurrent efforts may not be in place to ensure that the quality of cataract surgery is being monitored and improved. Worse outcomes have been shown to correlate with female gender, lower educational level, government facilities, and increasing age.1,2,3 Hence, the poorest and most vulnerable, suffer the worst outcomes after cataract surgery.

Studies from developing countries commonly conclude that visual outcomes or often below the desired benchmarks1,2,3,4,5,6,7 and even “unacceptable” in some cases.5 Pokharel et al. concluded in 1998 that: “In the quest to reduce cataract blindness, much more attention needs to be given to improving surgical outcomes.”5 They5 reported that 15% of eyes that underwent cataract surgery had presented visual acuity (VA) of ≥6/18 in both eyes. Postoperatively, 38% of the patients in Pokharel et al.'s study had ≥6/18 best-corrected VA and 21% of patients were still blind with VA of <6/60. Their study5 did not discuss the noncataract related causes of blindness in these patients. However, their5 finding of insufficient monitoring of outcomes is common in some Asian and African countries including South Africa.7,8 Lack of equipment or sub-standard equipment, inadequate training or skills (e.g., biometry), and inadequate resources such as intraocular lenses have all contributed to insufficient monitoring of outcomes.1,2,3

More recently (2013), the PRECOG multicenter observational study7 of 40 centers in 10 countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America concluded that it is logistically difficult to monitor quality of outcomes because of poor follow-up in rural settings. The study7 found that the longer follow-up visual outcomes correlated with the early postoperative outcomes in the best, intermediate and worst performing centers. Therefore, in these scenarios, early postoperative outcomes should suffice for quality monitoring.

Relying on coverage data such as the vision 2020 target, can result in complacency about the surgery being provided.9

“Quality” in cataract surgery is multifactorial, and can be taken from the perspective of the surgeon and service provider, or the patient and community perspective. Evaluation of the quality of a surgical service is a complex process. However, a starting point is to examine the current quality “assurance” and “improvement” mechanisms and how these are influenced by the knowledge, attitudes and practices of eye surgeons. The US Institute of Medicine defines quality in healthcare as a measure of desired outcome.10 This article will focus on quality demonstrated in desired clinical outcome rather than aspects such as waiting times, the facilities and ease of access.

In a study from Kenya, Yorston et al.11 demonstrated that monitoring visual outcomes improved the number of cataract patients achieving a “good” outcome from 77% to 89% in 12 months. While there was no net reduction in the incidence of operative complications, good outcomes after vitreous loss increased from 47% to 71% in the second half of the 12-month period.11 Despite the logical suggestion that monitoring was the direct cause for improvement, the interaction between change in practice and the attitudes of clinicians remains unclear.

We undertook a situation analysis to evaluate the existing attitudes and practices regarding outcomes of cataract surgery at two teaching hospitals in the Republic of South Africa (RSA).

METHODOLOGY

In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted over 4 days with ophthalmologists in June 2012 in the Department of Ophthalmology of two tertiary hospitals in South Africa. These hospitals had 17 ophthalmologists and trainees who perform cataract surgery. Cataract surgery was performed with phacoemulsification and extracapsular extractions for dense cataracts.

Consultation with the National Research Ethics Service in the UK confirmed that this observational evaluation of current services would not require formal ethical committee approval. In addition, there was no requirement in RSA for research ethics board approval for this observational, participative situation analysis. The process was guided by the relevant heads of department. This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki because the respondents might be considered subjects of the situation analysis.

A question guide was designed that focused on the perceived mechanisms for detecting poor provision of cataract service at the individual, departmental and national levels. Interviews explored the presence and nature of incentives for improving service. Objectives for developing processes for improving quality were examined by asking respondents to reflect on the issue if their own relatives were undergoing surgery at the institution. The resulting guide was submitted to the head of department of each hospital for review of relevance and sensitivity. Comments were taken into account when conducting the pilot interview. The question guide was adapted into two versions: One for consultants, the other for trainees.

The standard practice in hospitals is for trainees to perform cataract surgery under the supervision of consultants. Trainees range from medical officers, (i.e., “postfoundation” doctors in nonspecialist training) to year 4+ specialist registrar grades. All trainees and trainers for cataract surgery were included in this study. There were no exclusions.

Following each day of interviews, key and or interesting themes were highlighted for further exploration with subsequent respondents. 18 respondents were contacted by E-mail via their head of department with an information sheet about the situation analysis and a request for consent to be interviewed. Most participants replied with a date and time for the interview. Those who did not respond to E-mails were approached individually by the trained interviewer to whom all respondents were professionally more senior. None of the individuals refused the interview. One clinician was on annual leave and could not be included. Prior to each interview, the participant being interviewed underwent a thorough informed consent procedure that included addressing any questions they had. Subsequently every participant gave verbal consent to be included in the study. Participants consented to be recorded and quoted anonymously for the purpose of the situation analysis. The interviews were scheduled around the convenience of the participant and at participant's choice. Interviews were performed in an enclosed office space that was not audible to others. All interviews were performed by the same trained qualitative interviewer and lasted between 20 and 60 min.

Day 1 was for the pilot interview only, questions were minimally revised (for clarity); and the remaining interviews were performed on days 2, 3, and 4. The use of both open and closed-ended questions, and varied interviewee grades, allowed some method and data triangulation respectively. The short interval between interviews made triangulation by time and detailed observation unfeasible. We anticipated that a long interval between appointments may give clinicians too much opportunity to prime colleagues and therefore bias the results. Consequently, the interviews were performed over four consecutive days.

The pilot interview was included in the analysis as the final set of questions did not significantly differ from the initial set of questions. Responses were recorded, transcribed verbatim and analyzed for thematic content. Themes were drawn from two of the authors and themes that they agreed on were included in the final draft.

RESULTS

The study sample was comprised of 16 out of 17 potential participants. There were with five females and eleven males. Experience in ophthalmology varied according to grade. Four participants had <5 years, nine had 5–10 years and one had 17 years experience. Two had been ophthalmologists for >30 years.

Quality improvement motivators

Half of the respondents (8/16) identified “personal integrity,” and/or the desire to maintain a good professional reputation as the main motivators for South African doctors to provide good quality surgical services. None identified existing systems for incentivizing good quality service in the country or sanctions for poor performance. Some (3/16) respondents stated that some institutions performed audits to motivate good outcomes while the majority stated this was not the case. A typical response conveyed that the respondent did not “think they have any formal ways to improve other than individual surgeons trying to achieve the best they can.” Common observations generally conveyed the following: “In general- there's no broad audit that occurs as a mechanism.”

The main positive points of the existing system were: “People's desire to be perfect…” The frequent response was that, “if you are working in a small department, you will soon hear from people who are repeatedly doing vitrectomies … most of the registrars here are particularly driven people … everybody is aiming for perfect.”

Quality assurance: Identifying sub-optimal services

No formal national quality assurance processes were reported. Respondents observed “outcomes are mainly looked at in terms of numbers … there's quite a lot of assumption that the number of cases that were done, were pretty much all done well.”

The majority of respondents felt that there were no means to identify surgeons or units performing below an accepted level in terms of surgical outcomes. Some did feel that perceptions of other centers, based on trends in complications referred from those centers, might alert the medical community to units with poorer outcomes. Additionally, patient perception is expressed by “voting with their feet.”

Notably, even those that felt units with poor outcomes might be detected by this method, they acknowledged that there was no “governing body that actively monitors outcome measures.”

Quality improvement and assurance mechanisms within units: Monitoring personal outcomes

The majority (11/16) of respondents stated that individual surgeons are expected to audit their own results. The majority (13/16) also felt consistently poor quality surgery was unlikely to go unnoticed by colleagues within the department due to shared ward rounds. Here, colleagues see the postoperative cases of all surgeons, regularly. “Everyone knows what's going on and there are rounds every day. If a patient is admitted with complications, everybody knows the next day. Hence, there's also that bit of pressure, you know that if you are performing badly everybody will know, and it will be picked up…” Respondents were less clear about what the implications of being identified as having poorer outcomes. For the trainees it was suggested that they “will probably just get more supervision and get to do less in theatre until you build up.”

All surgeons claimed to know their own rate of complications (primarily posterior capsule rupture [PCR] rate), and this was deemed an entrenched practice. One consultant reported that “I will often ask on the ward round… “what is your (PCR) rate?” and they should be able to tell me…”

Knowledge of refractive outcomes was less frequently reported, with only 9/16 surgeons claiming to have an idea of their postoperative refractive outcomes following cataract surgery. It was suggested that “we each know, and I know my own refractive outcomes in a kind of soft way … but in terms of documenting it … do I personally have that data available for myself?… The answer is no, I don’t.”

Hence, an assessment of complication rates and refractive outcomes is not required of surgeons. Most (13/16) respondents felt that departments rely on an individual surgeon's self-motivation to audit personal outcomes as no external monitoring process: “…Every surgeon looks at his own results; (our department) doesn’t audit our results … it boils down to the surgeon himself to monitor his outcomes and I think that's how it works out in most institutions.”

A proportion (7/16) of respondents felt that supervising consultants were also able to function as gatekeepers to prevent consistently poor outcomes with remediation measures until a satisfactory competence level is reached.

Two outliers, both trainees, felt very differently saying that a surgeon experiencing higher complication rates than colleagues would not be identified, since there are no departmental audit of complication rates.

Quality assurance: Benchmarking

With the success defined in terms of postoperative VA compared to the preoperative vision, 15/16 respondents were aware of the World Health Organization (WHO) benchmarks for cataract surgery. Notably, none identified any national or local benchmarks for cataract services in the country. Similarly, none had formally evaluated their own results in the past 12 months to see if they achieved the desired success rates.

Quality improvement: Training

Evaluation of the progress in surgical training was basically an apprenticeship model. Junior surgeons are required by their college to maintain a logbook, which contains complication rates, but no systematized quantitative evaluation of the logbook is conducted by trainees or by the training institution. Qualitative feedback from direct supervision of surgery in the theater, and verbal quarterly appraisals where surgeons may be asked their PCR rate is the main method to evaluate trainees.

A trainer responded, “what we do not do, and people could argue that we should do or could do, is to monitor each of the trainees – to ask each of them to (hand in) copies of their log book so that we could monitor them. We do not do that.”

Another consultant who was not in favor of monitoring outcomes felt that it would erode the ease with which trainees openly discuss weaknesses and seek assistance; “you are quite open because there is no competition in trying to be better than anybody else- and nobody is counting, so you are quite open about your problems and trying to make it better. If there would be an audit, you’d probably not be so open about your problems.”

Three of 7 consultants also expressed that continuity is difficult to maintain as trainees quickly move from rotation to rotation. However, one felt that this is compensated by consultants talking to one another about trainees, thereby flagging those who require greater assistance.

Quality improvement: Critical incidence reporting

Reporting and institutional learning processes following critical incidents (such as surgery on the wrong eye, implantation of the wrong lens, patient in surgery without biometry or) were fairly explicit. Most (15/16) surgeons were aware of an existing departmental “critical incidents” protocol, which was an E-mail to the head of department who then disseminated the learning points at his/her discretion.

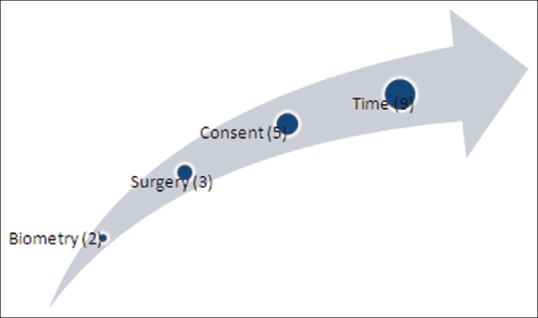

Figure 1 illustrates areas where improvement is desired. Surgeons were asked what their concerns would be if their own relatives underwent surgery at their unit. The surgeon responded with similar answers based on waiting from diagnosis to surgery and waiting time on the day of surgery along with the quality of consent. Only a few respondents commented on the seniority of the surgeon operating, and two respondents mentioned the need to ensure that biometry was performed prior to surgery to ensure effective refractive correction.

Figure 1.

Areas of desired improvement

DISCUSSION

Republic of South Africa has the highest gross domestic product in the African continent.12 Hence, the teaching institutions might be expected to represent the best practices in Sub-Saharan Africa. The teaching institutions also serve as a model that shapes the attitudes of the trainees. In this study, a situation analysis was conducted to explore the need for interventions to promote outcomes monitoring of cataract surgery. This would allow research into the effectiveness of these interventions if required.

In the current study, we found the quality assurance mechanisms were very heavily dependent on the individual surgeons having insight and integrity. Although the assumption of the presence of these qualities may be accurate in the majority of the cases, explicit mandatory structures to provide quality assurance in health care, and particularly in surgical services, are becoming increasing widespread globally.

Even though the WHO benchmarks for outcomes in cataract surgery were almost unanimously cited, no structures were described that would ensure the detection of individuals or institutions with higher than expected complication rates or poor visual outcomes. Some may claim that it is insufficient to rely on the trainees themselves to flag problems with their practice. However, this “soft” self-monitoring practice is perceived by some surgeons to facilitate an inherent openness on postoperative outcomes. Current practice also avoids surgeon-to-surgeon comparison, which would be inappropriate since the more experienced surgeons are likely to operate on the complex cases and will have seemingly “poorer” surgical outcomes.

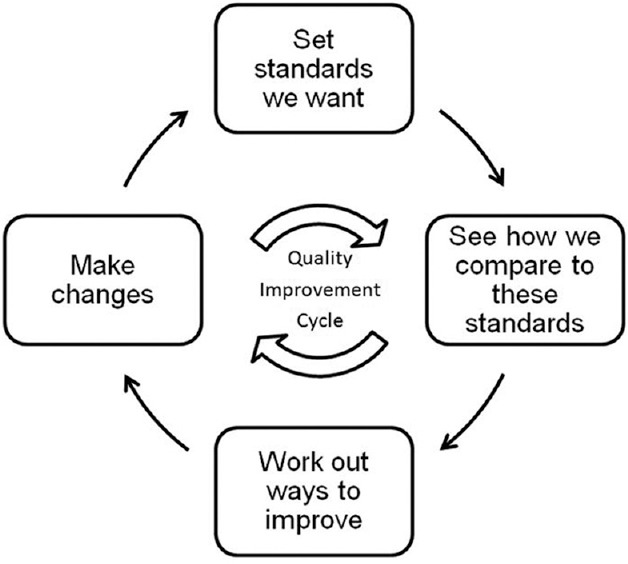

It should be acknowledged that there is little evidence that relying on the surgeon's insight and integrity in RSA is any worse than other proposed quality assurance mechanisms. However, if patients are considered “consumers,” overt demonstration of the attainment of agreed standards will increasingly be required as patients become increasingly empowered. Creating systematic monitoring structures drives the quality improvement cycle [Figure 2]. Systematic monitoring will foster confidence in physicians and patients regarding the surgery being provided. In addition, the routine practice of self-auditing by senior ophthalmologists should encourage the self-audits among trainees.

Figure 2.

Audit cycle for cataract surgical service

Although the audit process is time-consuming, there is growing consensus internationally that it is mandatory for those providing surgical services to report complication/success rates that meet national or international standards. This process can facilitated by paper based or computer spreadsheet-based models that are freely available from the International Centre for Eye Health.13 Repeated audit cycles of refractive outcomes and biometry are effective at improving visual outcomes.11

The published evidence indicates that monitoring the quality of cataract surgery improves postoperative VA.14,15,16 The concerns of some respondents that monitoring may erode the current perceived openness among ophthalmologists regarding visual outcomes and complications may or may not be realized. However, the authors experience of introducing monitoring in the healthcare systems of other countries, suggests that surgeons embrace the audit process as a means to encourage everyone to achieve the highest standards.

CONCLUSION

This situation analysis describes a system that can be enhanced. The assumption of personal accountability for quality control can develop into a more transparent and formal system for surgeons to demonstrate that their outcomes meet the accepted minimum standards.

Different benchmarks and processes will be needed for trainees and for consultants. The methods used in this study allowed the involved institutions to propose that trainees move to a structured monitoring and auditing of their own surgical outcomes with the aim of showing a qualitative trend in improvement, not a quantitative comparison between colleagues.

Significant research can be performed into the cultural and professional acceptability of monitoring complications and cataract surgery outcomes, as well as research into the effects of implementing these systems on the surgical outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to thank the staff at participating Hospitals in South Africa.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Isawumi MA, Soetan E, Adeoye A, Adeoti CO. Evaluation of cataract surgery outcome in Western Nigeria. Ghana Med J. 2009;43:169–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He M, Xu J, Li S, Wu K, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB. Visual acuity and quality of life in patients with cataract in Doumen County, China. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1609–15. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thulasiraj RD, Reddy A, Selvaraj S, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB. The Sivaganga eye survey: II. Outcomes of cataract surgery. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2002;9:313–24. doi: 10.1076/opep.9.5.313.10339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oladigbolu KK, Rafindadi AL, Mahmud-Ajeigbe AF, Chinda D, Pam V, Samaila E. Outcome of cataract surgery in rural areas of Kaduna State, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med. 2014;13:25–9. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.126943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pokharel GP, Selvaraj S, Ellwein LB. Visual functioning and quality of life outcomes among cataract operated and unoperated blind populations in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:606–10. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.6.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müller A, Zerom M, Limburg H, Ghebrat Y, Meresie G, Fessahazion K, et al. Results of a rapid assessment of avoidable blindness (RAAB) in Eritrea. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2011;18:103–8. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2010.545932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Congdon N, Yan X, Lansingh V, Sisay A, Müller A, Chan V, et al. Assessment of cataract surgical outcomes in settings where follow-up is poor: PRECOG, a multicentre observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e37–45. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook C, Kluever H, Mabena L, Limburg H. Rapid assessment of cataract at pension pay points in South Africa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:867–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.108910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pararajasegaram R. Importance of monitoring cataract surgical outcomes. Community Eye Health. 2002;15:49–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1990. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21 st Century; p. 244. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yorston D, Gichuhi S, Wood M, Foster A. Does prospective monitoring improve cataract surgery outcomes in Africa? Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:543–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Monetary Fund. Sub. Saharan Africa Region Dataset GDP Based on PPP Share of the World: World Economic Outlook. c2013. [Last cited on 2013 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/index.php .

- 13.Monitoring Cataract Surgical Outcomes. International Centre for Eye Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Community Eye Health J. c2010. [Last cited on 2013 Nov 5]. Available from: http://www.cehjournal.org/resources/monitoring-cataract-surgical-outcomes/

- 14.Limburg H, Foster A, Vaidyanathan K, Murthy GV. Monitoring visual outcome of cataract surgery in India. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:455–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limburg H, Foster A, Gilbert C, Johnson GJ, Kyndt M, Myatt M. Routine monitoring of visual outcome of cataract surgery. Part 2: Results from eight study centres. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:50–2. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.045369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang Y, Foster PJ. Quality assessment of cataract surgery in regions with low follow-up rates. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e9–10. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70007-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]