Abstract

Purpose:

To report the characteristics and laboratory findings of 182 patients with bacterial keratitis diagnosed at Farabi Eye Hospital in Tehran, Iran.

Materials and Methods:

In this retrospective study, data were collected on demographics, risk factors, location, size and depth of the ulcer, height of the hypopyon, uncorrected visual acuity, results of smear and culture tests, and antibiotic sensitivity of cultured bacteria.

Results:

There were 110 (60.4%) males and 72 (39.6%) females with an average age of 56.0 ± 2.3 years. Ocular trauma (17.6%) and positive history of corneal surgery (14.3%) were major risk factors. The mean age of contact lens users was 22.5 ± 7.7 years. Sixty patients (33%) used topical antibiotics, 21 (11.5%) patients utilized topical steroid, and 26 (14.3%) cases used both topical antibiotic and steroid at presentation. Culture results were, 81 (44.5%) cases were Gram-positive, 63 (34.6%) were Gram-negative, 10 (5.5%) were mixed bacteria and in 28 (15.4%) cases had detected growth. The isolated bacterial species from the corneal ulcers were less resistant to ceftazidime (6%) and amikacin (6%). The majority of patients were treated with medical therapy; however, 81 cases (44.5%) received at least one surgical procedure.

Conclusion:

Among the patients with bacterial corneal ulcers, trauma was the most common risk factor. Over-the-counter antibiotic and steroid were commonly used in the majority of patients. The most common bacteria isolated were Gram-positives, and they were less resistant to ceftazidime and amikacin. Penetrating keratoplasty was the most common surgical procedure in patient who required surgery.

Keywords: Antibiotic Sensitivity, Bacterial Keratitis, Corneal Infection, Corneal Ulcer, Epidemiology, Risk Factor

INTRODUCTION

Corneal infections can be considered as one of the most significant visual threatening conditions. Corneal infections are the second most common cause of monocular blindness in developing countries.1 Infections due to invasive pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus can cause corneal perforations in <24 h.2

Therefore, early treatment to halt the disease process is warranted. Early treatment may also limit the extent of corneal scarring, which can cause loss of vision. While awaiting culture results, aggressive and broad-spectrum therapy with a combination of fortified antimicrobials is usually initiated.3

Empiric antibiotic therapy is based on the prevalence of microorganisms in the community. The epidemiologic pattern of microbial species that are responsible for bacterial keratitis and their sensitivity to different antibiotics varies from one geographic region to another.4

In the US, the incidence of corneal ulcer is approximately 11.0/100,000 persons/year.5 However, in developing countries the incidence is reported to be approximately 799/100,000 persons/year.6

In the northern US, Gram-positive organisms are the most common cause of microbial keratitis.4 However, there is a marked predominance of fungal and Gram-negative organisms in the southern States.7

In this study, we report the characteristics and laboratory findings of patients with bacterial corneal ulcer who were admitted to Farabi Eye Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective review of all patients with bacterial keratitis who were admitted to the Farabi Eye Hospital during a 4-year period from March 2008 to March 2012. Although this hospital is located in an urban area, a large number of patients from all parts of the country, including both rural and urban areas, are referred to this tertiary hospital. The Farabi Eye Hospital is the largest referral eye center in Iran.

This study was performed at Department of Ophthalmology at Farabi Eye Hospital (Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran) and was approved by ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. A chart review was performed of all patients who were admitted to the Farabi Eye Hospital with the diagnosis of corneal ulcer. A total of 182 patients with smear-proven bacterial keratitis was included. Cases with incomplete medical records and patients with other clinical diagnosis, such as fungal or viral keratitis, were excluded.

We have reviewed demographic characteristics, the time between onset of symptoms and admission, duration of admission, history of trauma, contact lens wear, prior history of corneal surgery, history of ophthalmic disease, antibiotic or corticosteroid consumption prior to admission, location, size and depth of the ulcer, height of the hypopyon, uncorrected visual acuity, results of smear and culture of the corneal ulcer, and antibiotic sensitivity of the cultured bacteria. The location of corneal ulcer was reported as central, if it was dominant in central 5 mm of the cornea, and peripheral, if it was dominant within 3 mm from the limbus.

Anterior chamber reaction was scored based on Hogan and associates8 for the Tyndall effect and with 0–4 cell scoring method.

The corneal scraping for smear and culture was performed with sterile cotton-tipped swabs under direct visualization with slit-lamp biomicroscopy. The specimens were placed on a glass slide and transport medium for laboratory testing. Gram and giemsa staining of the scraped smear were routinely prepared and examined.

For bacterial cultures, the smears were aerobic inoculation was performed at 37.8°C onto chocolate agar maintained in a candle jar (10% carbon dioxide), sheep blood agar and nonnutrient agar. Cultures on blood agar and chocolate agar were evaluated at 24 and 48 h and subsequently discarded if there was no growth. Selective media for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, fungal, mycobacteria and acanthamoeba were also used at the clinician's discretion based upon the suggestive clinical features.

All statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (version 16.0; IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA). The Wilcoxon Test and Mann–Whitney tests were used accordingly. A P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

RESULTS

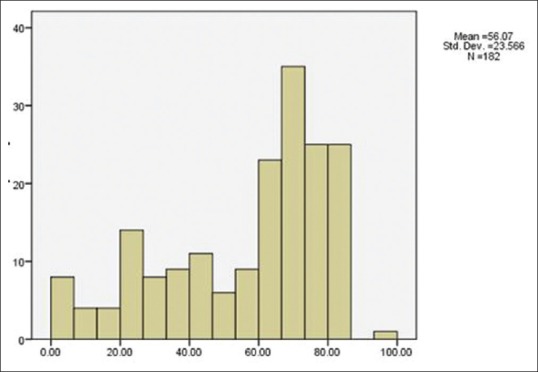

Data were collected on a total of 182 eyes with bacterial keratitis. There were 110 (60.4%) males and 72 (39.6%) females with an average age of 56 ± 2.30 years (range: 4 months to 95 years). The prevalence of bacterial keratitis was most frequent during the seventh and eighth decades [Figure 1]. The mean number of days between the onset of symptoms and referral to Farabi Eye Hospital was 12.98 ± 1.94 days.

Figure 1.

Distribution of age in patients with bacterial keratitis

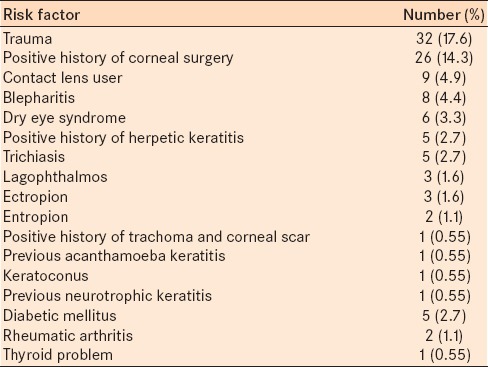

Patients presented with reduced visual acuity (98.9%), ocular pain (84%), ocular redness (73.6%), epiphora (10.4%), mucopurulent discharge (9.3%), periorbital edema (8.8%), photophobia (6%), and foreign body sensation (6%). The most common risk factor for bacterial keratitis was ocular trauma (17.6%) followed by a positive history of corneal surgery (14.3%), and 1.6% of corneal ulcers were postrefractive surgery. Other ocular conditions that predisposed to bacterial keratitis were present in 36 eyes [Table 1].

Table 1.

Risk factors for bacterial keratitis

The mean age of contact lens users was 22.5 ± 7.7 years, the mean age of patients with trauma was 35 ± 23. Four years, and the mean age of patients with other ocular problems was 55.6 ± 23.2 years.

Seventy-five cases (41.2%) did not use any medication prior to their admission however 60 patients (33%) were taking topical antibiotic, 21 cases (11.5%) used topical steroid, and 26 cases (14.3%) used both topical antibiotic and steroid at the time of presentation.

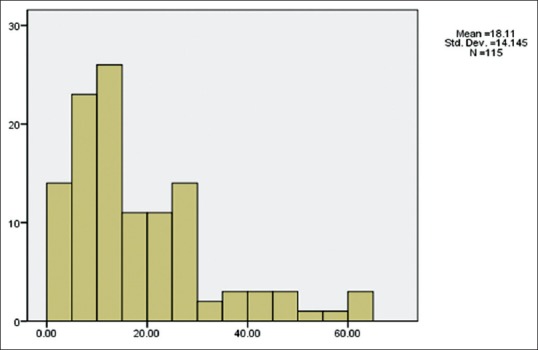

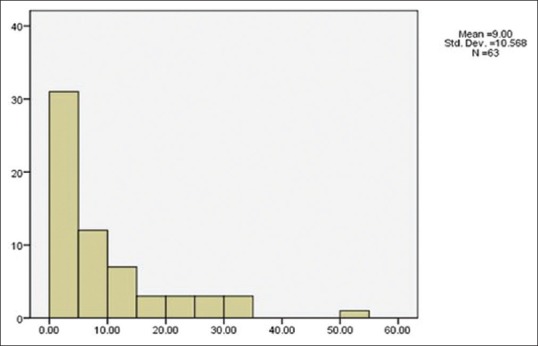

One hundred twenty-two (67.1%) ulcers were located in the central cornea, 51 ulcers (28%) were located in the periphery, and 9 ulcers (4.9%) involved the entire surface of the cornea. The mean surface area of corneal ulcer at the time of admission was 18.11 ± 14.14 mm2. The mean surface area of corneal ulcer at the time of discharge that was recorded for 63 patients was documented to 9.00 ± 10.56 mm2 [Figures 2 and 3].

Figure 2.

The mean surface area of corneal ulcer at the time of admission (mm2)

Figure 3.

The mean surface area of corneal ulcer at the time of discharge (mm2)

At the time of the first examination, the depth of infiltration in most cases (66%) was less than one-third. The depths of infiltration in 23% of patients were greater than one-third, and corneal perforation occurred in 11% of cases.

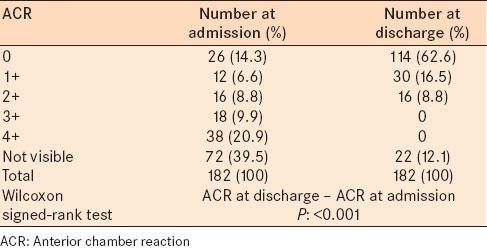

Most of the patients had 4 + anterior chamber reaction at the time of admission. The majority of patients had no anterior chamber reaction at the time of discharge from Farabi Eye Hospital [Table 2].

Table 2.

ACR in patients with bacterial keratitis at admission to Farabi Eye Hospital and discharge from Farabi Eye Hospital

Hypopyon was noted in 124 patients at admission and in 96 patients at discharge. The mean height of hypopyon at the time of admission and at the time of discharge was 0.996 ± 1.2 mm and 0.157 ± 0.5 mm respectively.

At presentation, visual acuity was less than or equal to hand motion (HM) in 137 (75.3%) eyes and visual acuity >20/40 was noted in 3 (1.6%) eyes. At discharge, 111 (61%) eyes had visual acuity ≤ HM and 18 (9.9%) of eyes had visual acuity >20/40.

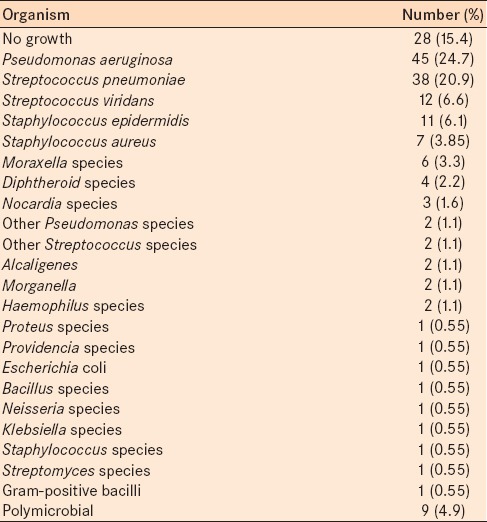

Of the 182 samples, 154 (86.4%) were culture positive; however, 28 cases (15.4%) were culture negative. From smear review, 52 cases revealed (28.6%) Gram-positive diplococci, 48 (26.4%) Gram-negative bacilli, 17 (9.3%) Gram-positive bacilli, 12 (6.6%) Gram-positive cocci, 8 (4.4%) Gram-negative diplobacilli, 4 (2.2%) Gram-negative diplococci, 2 (1.1%) Gram-negative coccobacilli, 1 (0.55%) Gram-negative cocci, and 10 cases (5.5%) were mixed bacteria. Table 3 indicates the result of pathogen characteristics by corneal cultures. Twenty-eight (15.4%) of cultures had no bacterial growth following 2 weeks follow-up.

Table 3.

Results of culture results for pathogen identification

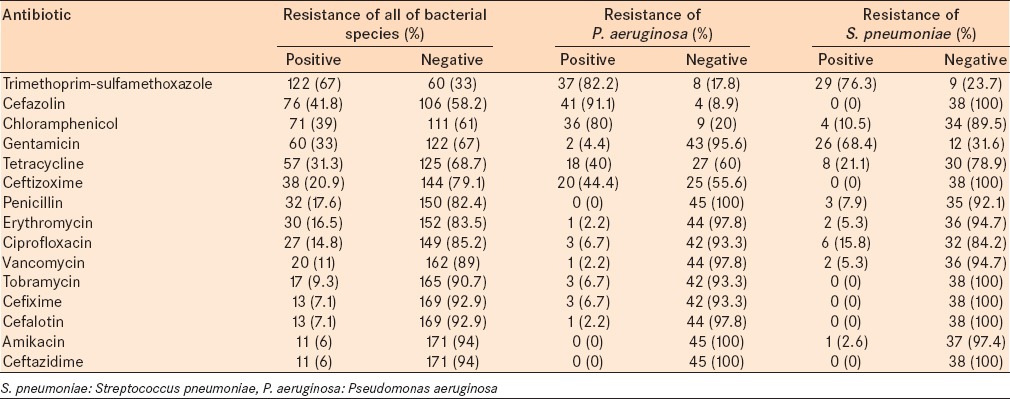

The isolated bacterial species from the corneal ulcers were less resistant to ceftazidime (6%) and amikacin (6%). Table 4 denotes the antibiotic resistance of all bacterial species that were isolated from our study and the antibiotic resistance of the two most common isolated bacteria, P. aeruginosa and Streptococcus pneumonia.

Table 4.

Antibiotic resistance of all of the bacterial species isolated from bacterial keratitis and antibiotic resistance of two most common isolated bacteria, P. aeruginosa and S. pneumoniae

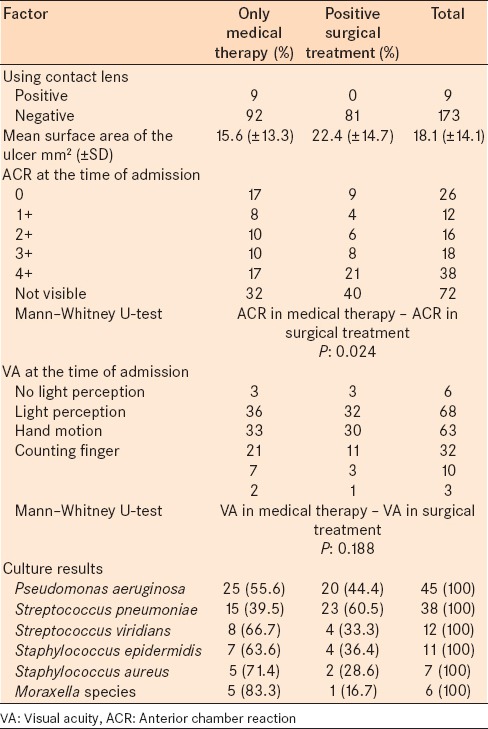

Of the 182 patients with bacterial keratitis who were admitted, 101 patients (55.5%) were treated with medical therapy only, and 81 cases (44.5%) had at least one surgical procedure. Surgical procedures included 38 cases of penetrating keratoplasty, 33 cases of tarsorrhaphy, 22 cases with conjunctival flap, 9 cases of scleral graft, 7 cases of corneal glue, and 6 cases of evisceration. Among the patients who underwent evisceration, 2 patients were positive for P. aeruginosa, 1 patient was positive for Streptococcus viridians, 1 patient was positive for Staphylococcus epidermidis, 1 patient was positive for Proteus species, and sample for 1 patient showed no growth in culture. Table 5 presents the relationship between risk factors and the type of treatment.

Table 5.

The relationship between a number of risk factors and type of treatment for corneal ulcer

DISCUSSION

Bacterial keratitis is a potentially sight-threatening condition. The prevalence of the risk factors, etiological agents, and bacterial susceptibilities vary from one geographical area to another. In our study, the ratio of male to female patients was 1.52–1 which is similar to Srinivasan et al. studies9 and Gonzales et al. studies.10 Bacterial keratitis occurred most frequently during the seventh and eighth decades, similar to other reports11 but presented later some studies.12

The mean number of days between the onset of symptoms and referral was 12.98 ± 1.94. This is similar to the duration reported by Yilmaz et al.,13 but longer than other studies.14

Approximately 17.6% of our patients presented with a positive history of ocular trauma that was similar to the other reports,15 it was the major predisposing factor for bacterial keratitis. Some studies have reported contact lenses wear as a major risk factor among patients.16 However, we found it was the third most common risk factor, following trauma and previous corneal surgery. Among the patients admitted to Farabi Eye Hospital, postrefractive surgery corneal ulcer was detected in 3 (1.6%) patients during the period investigated in this study. This rate was higher than Frédéric et al. study.17 Our study indicated the mean age of contact lens users was lower than the patients with other risk factors (the mean age of contact lens users was 22.5 ± 7.7 years, the mean age of patients with trauma was 35 ± 23.4 years, and the mean age of patients with other ocular problems was 55.6 ± 23.2 years). The female: Male ratio was 2:1. Among the patients who had previous corneal surgery, penetrating keratoplasty was the most common procedure.

One hundred and seven cases (58.8%) received medication prior to presentation at Farabi Eye Hospital. Sixty (33%) patients were prescribed topical antibiotic, 21 (11.5%) were prescribed topical steroid, and 26 (14.3%) were prescribed both topical antibiotic and steroid. In contrast studies from Southern India reported rates from 8% and 30.6%.9,18

In majority of our cases (67.1%), ulcers were located in the central cornea, 51 (28%) ulcers were peripheral and 9 (4.9%) ulcers involved the entire surface of the cornea. These observations are similar to previous studies that report centrally located ulcers were more common than peripheral ulcers.12,19

Eleven percent of the patients had corneal perforation at admission. This rate of perforation was higher than the other reports20 and might be due to the late presentation of the cases to the hospital or the high rate of topical steroid use prior to admission.

Patients with a larger size of ulcer had poorer visual acuity. This outcome is concurs with previous reports.21,22

In our study, 84.6% of corneal scrapings were culture positive. This is higher than the reports from Ghana23 and South India,24 and similar to a report from Bangladesh25 (57.3%, 70.6%, and 81.7%, respectively). In our study, 75% of the patients who received antibiotic and 89.4% of the patients who did not receive any kind of antibiotic had a positive culture report. According to another study, availability of topical antibiotics and their use before evaluation can cause the a lower rate of isolation.1

Like US studies,4 Gram-positive organisms were the most common cause of bacterial keratitis (44.5%). In our study, the most common species isolated was P. aeruginosa, which was similar to other reports.26,27 Carmichael et al. evaluated a group of African patients,28 and reported S. pneumonia was most common and Wong et al. in New Zealand,29 reported coagulase negative staphylococcus as the most common cause of bacterial corneal ulceration. P. aeruginosa results in a severe corneal ulcer. In this report, we studied only patients who were admitted to one tertiary eye care hospital. This group of patients had more severe corneal ulcers than patients who were not admitted. This may be the reason P. aeruginosa was the most common bacteria isolated. We found S. pneumonia was the second (20.9%) most common cause of bacterial ulceration. Similar to Green et al.,30 we found P. aeruginosa was the most common isolate in patients who were contact lens wearer (77.7%).

The average age of patients with S. aureus was lower (23.2 ± 11.8 years) and the average of patients with Moraxella species was higher (76. 1 ± 10.8 years) than all of our patients (56.1 ± 2.3 years).

Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from all the patients with previous refractive surgery. Huang et al.31 also reported S. aureus as the most common cause of bacterial keratitis following refractive surgery.

In the current study, the antibiogram report indicated that the isolated bacterial species from the corneal ulcers were less resistant to ceftazidime (6%), and amikacin (6%). All P. aeruginosa isolates were sensitive to ceftazidime and amikacin, and only 6.7% were resistant to Ciprofloxacin. Among the S. pneumoniae isolates, 2.6% were resistant to amikacin, and all were sensitive to cefazolin, ceftazidime, cefixime, and cephalothin.

Eighty-one (44.5%) patients had at least one surgical procedure. This was higher than the reports by Pachigolla et al.27 Saeed et al.12 and Limaiem et al.,32 which were 11%, 20% and 25.8% respectively. Similar to previous studies, penetrating keratoplasty was the most common surgical procedure (46.9%).32,33 However, almost 3% of our patients underwent evisceration although Limaiem et al.32 stated that of 8% of their patients may require this procedure.

In summary, among the patients with bacterial corneal ulcers, the male: Female ratio was 1.52:1. Trauma was the most common risk factor. Over-the-counter antibiotic and steroid were commonly used, and most patients had a delay in referral to the Eye Hospital of > 7 days. The most common bacterial species isolated were P. aeruginosa followed by S. pneumoniae. The isolated bacterial species from the corneal ulcers were less resistant to ceftazidime and amikacin. Among the patients who needed at least one surgical procedure, penetrating keratoplasty was the most common.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Upadhyay MP, Karmacharya PC, Koirala S, Tuladhar NR, Bryan LE, Smolin G, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics, predisposing factors, and etiologic diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111:92–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76903-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostler HB. Disease of the cornea. In: Mitchell CW, editor. Disease of the External Eye and Adnexa. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1993. pp. 137–252. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum JL. Initial therapy of suspected microbial corneal ulcers. I. Broad antibiotic therapy based on prevalence of organisms. Surv Ophthalmol. 1979;24:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(79)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wahl JC, Katz HR, Abrams DA. Infectious keratitis in Baltimore. Ann Ophthalmol. 1991;23:234–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erie JC, Nevitt MP, Hodge DO, Ballard DJ. Incidence of ulcerative keratitis in a defined population from 1950 through 1988. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:1665–71. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090120087027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upadhyay MP, Karmacharya PC, Koirala S, Shah DN, Shakya S, Shrestha JK, et al. The Bhaktapur eye study: Ocular trauma and antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of corneal ulceration in Nepal. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:388–92. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.4.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ormerod LD, Hertzmark E, Gomez DS, Stabiner RG, Schanzlin DJ, Smith RE. Epidemiology of microbial keratitis in southern California. A multivariate analysis. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:1322–33. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)80019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogan MJ, Kimura SJ, Thygeson P. Signs and symptoms of uveitis. I. Anterior uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1959;47:155–70. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)78239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasan M, Gonzales CA, George C, Cevallos V, Mascarenhas JM, Asokan B, et al. Epidemiology and aetiological diagnosis of corneal ulceration in Madurai, south India. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:965–71. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.11.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzales CA, Srinivasan M, Whitcher JP, Smolin G. Incidence of corneal ulceration in Madurai district, South India. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1996;3:159–66. doi: 10.3109/09286589609080122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Meulen IJ, van Rooij J, Nieuwendaal CP, Van Cleijnenbreugel H, Geerards AJ, Remeijer L. Age-related risk factors, culture outcomes, and prognosis in patients admitted with infectious keratitis to two Dutch tertiary referral centers. Cornea. 2008;27:539–44. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318165b200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saeed A, D’Arcy F, Stack J, Collum LM, Power W, Beatty S. Risk factors, microbiological findings, and clinical outcomes in cases of microbial keratitis admitted to a tertiary referral center in ireland. Cornea. 2009;28:285–92. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181877a52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yilmaz S, Ozturk I, Maden A. Microbial keratitis in West Anatolia, Turkey: A retrospective review. Int Ophthalmol. 2007;27:261–8. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerautret J, Raobela L, Colin J. Serious bacterial keratitis: A retrospective clinical and microbiological study. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2006;29:883–8. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(06)70108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keay L, Edwards K, Naduvilath T, Taylor HR, Snibson GR, Forde K, et al. Microbial keratitis predisposing factors and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirikul T, Prabriputaloong T, Smathivat A, Chuck RS, Vongthongsri A. Predisposing factors and etiologic diagnosis of ulcerative keratitis. Cornea. 2008;27:283–7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31815ca0bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frédéric S, Olivier B, Léonidas Z, Yan GC. Bacterial keratitis: A prospective clinical and microbiological study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:842–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.7.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gopinathan U, Garg P, Fernandes M, Sharma S, Athmanathan S, Rao GN. The epidemiological features and laboratory results of fungal keratitis: A10-year review at a referral eye care center in South India. Cornea. 2002;21:555–9. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200208000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shoja MR, Manaviat M. Epidemiology and outcome of corneal ulcers in Yazd Shahid Sadoughi Hospital. Acta Med Iran. 2004;42:136–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bourcier T, Thomas F, Borderie V, Chaumeil C, Laroche L. Bacterial keratitis: Predisposing factors, clinical and microbiological review of 300 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:834–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.7.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poole TR, Hunter DL, Maliwa EM, Ramsay AR. Aetiology of microbial keratitis in northern Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:941–2. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.8.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hooi SH, Hooi ST. Culture-proven bacterial keratitis in a Malaysian general hospital. Med J Malaysia. 2005;60:614–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leck AK, Thomas PA, Hagan M, Kaliamurthy J, Ackuaku E, John M, et al. Aetiology of suppurative corneal ulcers in Ghana and south India, and epidemiology of fungal keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1211–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.11.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bharathi MJ, Ramakrishnan R, Vasu S, Meenakshi R, Palaniappan R. Epidemiological characteristics and laboratory diagnosis of fungal keratitis. A three-year study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2003;51:315–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunlop AA, Wright ED, Howlader SA, Nazrul I, Husain R, McClellan K, et al. Suppurative corneal ulceration in Bangladesh. A study of 142 cases examining the microbiological diagnosis, clinical and epidemiological features of bacterial and fungal keratitis. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1994;22:105–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1994.tb00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fong CF, Hu FR, Tseng CH, Wang IJ, Chen WL, Hou YC. Antibiotic susceptibility of bacterial isolates from bacterial keratitis cases in a university hospital in Taiwan. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:682–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pachigolla G, Blomquist P, Cavanagh HD. Microbial keratitis pathogens and antibiotic susceptibilities: A 5-year review of cases at an urban county hospital in north Texas. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33:45–9. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000234002.88643.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carmichael TR, Wolpert M, Koornhof HJ. Corneal ulceration at an urban African hospital. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69:920–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.69.12.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong T, Ormonde S, Gamble G, McGhee CN. Severe infective keratitis leading to hospital admission in New Zealand. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1103–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.9.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green M, Apel A, Stapleton F. Risk factors and causative organisms in microbial keratitis. Cornea. 2008;27:22–7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318156caf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang AJ, Wichiensin P, Yang M. Bacterial keratitis. In: Krashmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, editors. Cornea. 1st ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. pp. 1005–41. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Limaiem R, Mghaieth F, Merdassi A, Mghaieth K, Aissaoui A, El Matri L. Severe microbial keratitis: Report of 100 cases. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2007;30:374–9. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(07)89607-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ly CN, Pham JN, Badenoch PR, Bell SM, Hawkins G, Rafferty DL, et al. Bacteria commonly isolated from keratitis specimens retain antibiotic susceptibility to fluoroquinolones and gentamicin plus cephalothin. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34:44–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]