Abstract

Amiodarone is an antiarrhythmic medication that can adversely effect various organs including lungs, thyroid gland, liver, eyes, skin, and nerves. The risk of adverse effects increases with high doses and prolonged use. We report a 54-year-old female who presented with multiorgan toxicity after 8 months of low dose (200 mg/day) amiodarone treatment. The findings of confocal microscopy due to amiodarone-induced keratopathy are described. Amiodarone may cause multiorgan toxicity even at lower doses and for shorter treatment periods.

Keywords: Amiodarone, Confocal Microscopy, Multiorgan Toxicity

INTRODUCTION

Amiodarone is a class III antiarrhythmic agent that is efficacious against all types of tachyarrhythmias. This medication is primarily used for preventing paroxysmal and persistent episodes of atrial fibrillation. However, the duration if use is limited due to the adverse effects association with amiodarone.1,2,3 In this report, we present a case of persistent atrial fibrillation that developed symptomatic hypothyroidism, skin discoloration, hepatotoxicity and corneal vortex keratopathy after 8 months of amiodarone therapy.

CASE REPORT

54-year-old female was admitted to the outpatient cardiology clinic with paroxysmal palpitation episodes 8 months prior to presentation at our center. Holter-electrocardiogram recordings demonstrated episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. After comprehensive cardiac evaluation, amiodarone therapy was started at an initial dose of 200 mg/day. General malaise, cold intolerance and blue-gray discoloration of the skin were noticed 7 months later. Dermatologic examination revealed bluish discoloration on the nose and cheeks [Figure 1a]. On histopathology, perivascular brown-gray pigment granule laden histiocytes were observed in the superficial dermis. Laboratory tests indicated slightly elevated serum aminotransferase levels (aspartate aminotransferase 54 μ/l [<31], alanine aminotransferase 73 μ/l [<34]). Thyroid function tests indicated hypothyroidism (free T4, 0.51 ng/dL [reference range, 0.7–2.01]; and thyroid-stimulating hormone, 41.23 μIU/mL [reference range, 0.4–3.1]). The patient was referred to an ophthalmologist for potential eye toxicity.

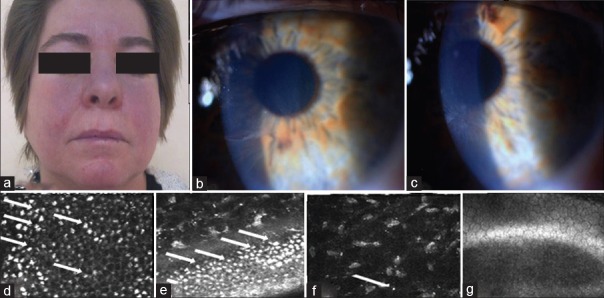

Figure 1.

(a) Blue-grey discoloration on the nose and central cheeks. Amiodarone-induced corneal opacities; (b) horizontal line in the inferior third of the cornea in the right eye, (c) whorl-like pattern of powdery, white, yellow or brown corneal deposits of the left eye. In vivo confocal microscopic images of hyperreflective intracellular inclusions of amiodarone keratopathy (d) in epithelial cells, (e) in basal epithelial cells, (f) in stroma, (g) no deposits in the endothelium

The patient underwent a complete ophthalmologic examination including measurement of visual acuity (VA), slit-lamp biomicroscopy, applanation tonometry, and dilated fundus examination. VA was 20/20 in both eyes. The intraocular pressures were within normal limits and the fundus examination was unremarkable in both eyes. There was no afferent pupillary defect. Slit-lamp examination indicated vortex keratopathy in both eyes. Vortex keratopathy was classified based on the grading system proposed by Orlando et al.4 The right eye presented with grade 1 vortex keratopathy (characterized by a horizontal line in the inferior third of the cornea), the left eye presented with grade 4 (a whorl-like pattern with additional clumps of pigment) [Figure 1b and c]. Both eyes underwent confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM), (Heidelberg Retina Tomograph, HRT II) equipped with the Rostock cornea module (Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). CLSM revealed hyper-reflective intracellular inclusions in both corneas. Inclusions were observed in the epithelium, stroma, and subepithelial nerves in both eyes [Figure 1d-g]. These findings were more evident in the epithelial basal cell layers. In the left eye with advanced keratopathy (stages 4), bright microdots were also detectable within the posterior stroma. Due to the ocular, skin and thyroid toxicity of the drug, amiodarone therapy was stopped and the patient underwent radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. Serum aminotransferase levels returned to normal limits after cessation of amiodarone. Although the discoloration of the face and vortex keratopathy regressed, this side effect did not disappear during the 5 months follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

Amiodarone is an iodinated benzofuran derivative. It has been associated with toxicity affecting the lungs, thyroid gland, liver, eyes, skin, and nerves. The daily (400 mg/day) and cumulative dose (100 g) combined with the length of therapy is associated with the toxicity. However, toxic effects may also be observed at lower maintenance doses, as observed in our patient.1,2,3

The most common cutaneous adverse effect of amiodarone is photosensitivity. Photosensitivity develops in approximately 75% of the patients usually after 4 months of treatment. Photosensitivity may persist between 4 and 12 months after stopping amiodarone. Eight percent of patients can develop hyperpigmentation due to accumulation of amiodarone metabolites on skin exposed to regular sunlight after 20 months of use. The primary step for skin discoloration is cessation of amiodarone. The pigmentation usually resolves within 2 years after cessation of the drug.3,4,5

The ocular effect of amiodarone is vortex keratopathy creating a whorl-like pattern by producing lysosomal deposits in the basal epithelial layer.6,7 The whorl-like pattern which was firstly described by Fleischer in 1910 is characterized as powdery, white, yellow, or brown corneal opacities beneath the cornea apex.4 Amiodarone reaches the cornea via the tear film, aqueous humor, and limbal vasculature. The drug or its metabolites penetrate lysosomes and bind with cellular lipids, producing drug-induced lipidosis.7 In the eye lysosomal storage leads to typical side-effects. Vortex keratopathy is the most common (70–100%) ocular change caused by amiodarone.8 Although the most common findings are corneal, lens opacities and optic neuropathy have also been reported due to amiodarone.9,10 In the current cases, lens changes and retinal changes were not observed. Photophobia, colored rings around lights and ocular irritation are the common symptoms of patients with amiodarone-induced keratopathy.9,10 However the patient in this case report did not complain of any of these symptoms. Corneal changes secondary to systemic amiodarone can affect all corneal layers.6,8,11 Our patient also had amiodarone-induced deposits within the corneal epithelium and stroma, but there were no deposits in the endothelial layer. The vision of this patient was not affected. Although corneal deposition is not an indication for drug cessation, patients receiving this medication should be monitored for symptoms related to corneal deposition and ocular toxicity.1,2

The iodine content of amiodarone effects thyroid functions ranging from mild changes to hypothyroidism or thyrotoxicosis. The frequency of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism is 2% and 6% respectively. In case of amiodarone-induced thyroid dysfunction, “dronedarone,” an iodine free variant of amiodarone is preferred.1 The patient in this case report complained of general malaise and cold intolerance. These symptoms may be attributed to hypothyroidism. Liver transaminase levels may be elevated in 0.6% of the patients. Amiodarone should be discontinued, if the liver enzymes are three times higher than normal limits.1 In our patient, liver enzymes were slightly elevated.

CONCLUSION

This case indicates that multiorgan toxicity due to amiodarone may develop even with short-term use and a low maintenance dose. Hence amiodarone should be used at lowest possible doses. Laboratory studies including liver and thyroid functions should be checked every 6 months and ocular examination should be done regularly to detect ocular side effects to prevent irreversible ocular damages in patients taking amiodarone.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siddoway LA. Amiodarone: Guidelines for use and monitoring. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:2189–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris L, McKenna WJ, Rowland E, Holt DW, Storey GC, Krikler DM. Side effects of long-term amiodarone therapy. Circulation. 1983;67:45–51. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rappersberger K, Hönigsmann H, Ortel B, Tanew A, Konrad K, Wolff K. Photosensitivity and hyperpigmentation in amiodarone-treated patients: Incidence, time course, and recovery. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93:201–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12277571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orlando RG, Dangel ME, Schaal SF. Clinical experience and grading of amiodarone keratopathy. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1184–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yones SS, O’Donoghue NB, Palmer RA, Menagé Hdu P, Hawk JL. Persistent severe amiodarone-induced photosensitivity. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:500–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollander DA, Aldave AJ. Drug-induced corneal complications. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2004;15:541–8. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000143688.45232.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Amico DJ, Kenyon KR, Ruskin JN. Amiodarone keratopathy: Drug-induced lipid storage disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:257–61. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010259007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uçakhan OO, Kanpolat A, Ylmaz N, Ozkan M. Amiodarone keratopathy: An in vivo confocal microscopy study. 2005;31:148–57. doi: 10.1097/01.icl.0000165283.36659.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flach AJ, Dolan BJ, Sudduth B, Weddell J. Amiodarone-induced lens opacities. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1554–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020556010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gittinger JW, Jr, Asdourian GK. Papillopathy caused by amiodarone. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:349–51. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060030069028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mäntyjärvi M, Tuppurainen K, Ikäheimo K. Ocular side effects of amiodarone. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:360–6. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]