Abstract

Background and Aims:

Various drugs are used for providing favorable intubation conditions during awake fiberoptic intubation (AFOI). However, most of them cause respiratory depression and airway obstruction leading to hypoxemia. The aim of this study was to compare intubation conditions, and incidence of desaturation between dexmedetomidine and fentanyl group during AFOI.

Material and Methods:

This randomized double-blind prospective study was conducted on a total of 60 patients scheduled for elective laparotomies who were randomly allocated into two groups: Group A received dexmedetomidine 1 mcg/kg and Group B received fentanyl 2 mcg/kg over 10 min. Patients in both groups received glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg intravenous, nebulization with 2% lidocaine 4 ml over 20 min and 10% lidocaine spray before undergoing AFOI. Adequacy of intubation condition was evaluated by cough score and post-intubation score. Incidence of desaturation, hemodynamic changes and sedation using Ramsay sedation scale (RSS) were noted and compared between two groups.

Results:

Cough Score (1-4), post-intubation Score (1-3) and RSS (1-6) were significantly favorable (P < 0.0001) along with minimum hemodynamic responses to intubation (P < 0.05) and less oxygen desaturation (P < 0.0001) in Group A than Group B.

Conclusion:

Dexmedetomidine is more effective than fentanyl in producing better intubation conditions, sedation along with hemodynamic stability and less desaturation during AFOI.

Keywords: Awake intubation, dexmedetomidine hydrochloride, fentanyl citrate

Introduction

Awake fiberoptic intubation (AFOI) is recommended for patients with anticipated difficult airway, failed intubation, unstable cervical spine injury where optimum positioning for laryngoscopy is difficult to achieve. It is essential to prepare patients prior to AFOI. The preparation includes obtundation of airway reflexes, adequate sedation, anxiolysis along with preservation of a patent airway and adequate ventilation.

Currently benzodiazepines, opioids, propofol are used alone or in combination for this purpose.[1,2] Midazolam produces amnesia and makes patient comfortable. Propofol has rapid onset and offset of action with profound amnesia. Opioids such as fentanyl and remifentanil are helpful for attenuating hemodynamic response and discomfort during passage of the bronchoscope through vocal cords. However, all of them are respiratory depressants. Though the combination of these drugs may provide better intubation conditions, however the incidence of hypoxemia is high.[3,4] In difficult airway scenarios, which may lead to cannot intubate, cannot ventilate situation, hypoxemia is to be avoided as it can lead to fatal consequences. Propofol in high dose may cause apnea and loss of tone of upper airway producing difficulty during the negotiation of the bronchoscope beyond epiglottis.[5,6] Hence there is a search of an ideal agent for conscious sedation, which will ensure spontaneous ventilation with a patent airway, adequate cooperation, smooth intubating conditions and stable hemodynamics without respiratory depression. In the present study, we compared dexmedetomidine with fentanyl for conscious sedation during AFOI in adult patients scheduled for elective abdominal surgeries. The aims of our study were to compare between these two groups: Intubation condition by cough score, tolerance to intubation by post-intubation score, hemodynamic parameters and incidence of oxygen desaturation (SpO2) if any.

Material and Methods

After obtaining institutional ethics committee approval and written informed consent from study subjects, this double blinded randomized prospective study was conducted among 60 patients of either sex, aged 20-60 years, belonging to American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA-PS) I and II, and posted for elective abdominal surgeries. Based on the result of previous study, we calculated the sample size of at least eight in each group with a power of 0.9 and type one error of 0.05. Due to availability of logistic support 30 patients were taken in each group as there is no upper limit of sample size. Patients with pregnancy, known alcoholic or drug abusers, allergy to the drugs involved in the study, bradycardia (baseline HR <60 beats/min), any type of atrioventricular block, heart failure, having significant neurological, hepatic, renal and pulmonary disease, emergency surgeries, any contraindication for nasal intubation like thrombocytopenia or coagulopathies were excluded from this study. Anticipated difficult intubation was excluded after assessment by modified Malampatti grading (MP) and thyromental distance (TMD). MP grade III and IV and TMD <6.5 cm were excluded.

Patients were allocated by computer generated random numbers and were divided into two groups. Group A — dexmedetomidine group (n = 30) and Group B — fentanyl group (n = 30). Dose of study drug was calculated according to patient's body weight, diluted with normal saline to make equal volume of 50 ml and enveloped according to patient's inclusion number. The anesthesiologist preparing the study drug and the observer anesthesiologists were blinded to each other. Bronchoscopy was performed by a single anesthesiologist in all patients. The anesthesiologist who performed AFOI and who recorded data were all blinded to the group identities.

Patients were pre-medicated with tab alprazolam 0.5 mg night before surgery, tab ranitidine 150 mg and tab ondansetron 4 mg on the morning 2 h before surgery. In the operating room, intravenous line (i.v.) was secured with wide bore cannula (18 G) and multichannel monitor was applied to record baseline Heart rate (HR), Mean arterial pressure (MAP), SpO2 and electrocardiogram. Injection glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg i.v. was given. Patency of both nostrils was tested and the nostril with better patency was chosen for awake nasal fiberoptic intubation. Topicalization of both the upper and lower airway was accomplished by nebulization with 2% lidocaine 4 ml (80 mg) for 20 min. Xylometazoline nasal drops and lidocaine jelly were applied to both the nostrils. Tongue and hypopharynx were sprayed with two puffs of 10% lidocaine (20 mg). After that dexmedetomidine (1 mcg/kg over 10 min) and fentanyl (2 mcg/kg over 10 min) was infused according to the subject's inclusion number. After lubrication bronchoscope was loaded with appropriate size cuffed polyvinyl chloride endotracheal tube. At the end of the study drug infusion, sedation was evaluated by Ramsay sedation scale (RSS).[7] After achieving Score ≥2, bronchoscopy was performed through nasal approach. After proper placement of tube in trachea general anesthesia was induced and surgery was allowed to proceed.

Intubation condition was evaluated by cough score during bronchoscopy as Score 1 = no cough, 2 = slight cough (no more than two cough in sequence), 3 = moderate cough (3-5 cough in sequence), 4 = severe cough (>5 cough in sequence).[8] Tolerance to intubation was evaluated by post-intubation score after placement of tube in the trachea as: 1 = Co-operative, 2 = minimal resistance, 3 = severe resistance.[9] Level of sedation was evaluated by Ramsay sedation score (RSS) just after completion of infusion of study drug as: 1 = Anxious, agitated or restless, 2 = cooperative, oriented and tranquil, 3 = sedated but responds to command, 4 = asleep, brisk glabellar reflex responds to loud noise, 5 = asleep, sluggish glabellar reflex or responds to loud noise, 6 = asleep with no response to a painful stimulus. MAP and HR were noted as a baseline and immediately after intubation. SpO2 was monitored throughout the procedure and lowest one was noted. Hypotension (reduction of MAP >20% from baseline) was treated with i.v. fluid and/or phenylephrine 50 mcg i.v. bolus, repeat dose after 5 min. Bradycardia (HR <60 beats/min) was treated with atropine 0.6 mg i.v. Oxygen desaturation (SpO2<95% for >10 s) was treated with oxygen supplementation either through a nasal cannula or oxygen port of bronchoscope.

Numerical data were expressed as mean with a standard deviation and categorical data were put into tables. Statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical package for the social sciences 16.0 statistical software packages. Numerical data were compared between two groups using independent t-test and within the same group using paired t-test. Categorical data were compared between two groups using Chi-square test. All analysis was two tailed and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

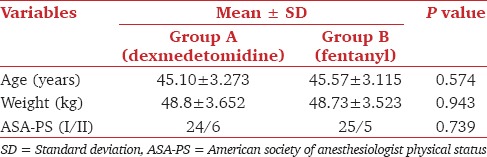

Demographic characteristics like age, weight and ASA-PS (I/II) were comparable between two groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data

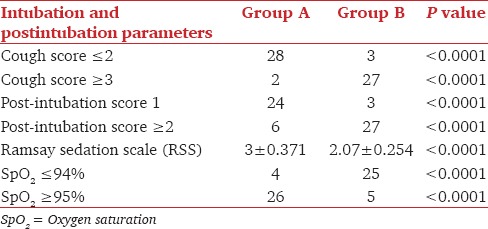

Cough score ≤2 was considered as favorable intubation condition, which was achieved in 28 out of 30 patients in Group A, but only in 3 out of 30 patients in Group B. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). Better post-intubation score (Score 1) was found in 24 patients of Group A and only three patients in Group B. This difference was also statistically significant (P < 0.0001). At the end of study drug infusion, higher RSS was achieved in Group A (3 ± 0.371) than in Group B (2.07 ± 0.254) (P < 0.0001). We observed that 26 patients of Group A and only five patients in Group B were able to maintain SpO2 (≥95%) (P < 0.0001) during the procedure. 25 patients in Group B and four patients in Group A suffered from significant desaturation (SpO2≤94%), which was managed by administration of oxygen through the port of the bronchoscope [Table 2].

Table 2.

Cough score, post-intubation score, sedation score, SpO2

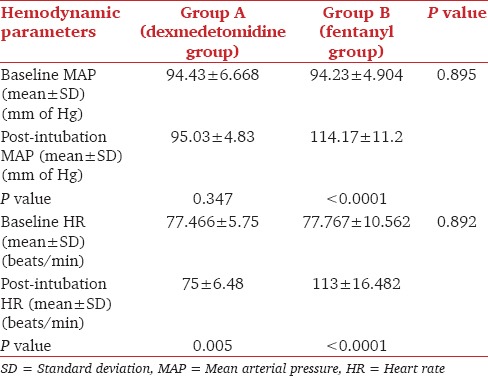

The baseline MAP, HR and SpO2 were comparable between two groups [Table 3]. There was a rise of MAP compared with baseline values in both groups. The increase of MAP was minimal in Group A (P = 0.347). However, in Group B rise of MAP was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). There was no episode of hypotension in both groups. There was a significant increase in HR in the post-intubation period (113 ± 16.482 beats/min) in comparison with the baseline value (77.767 ± 10.562 beats/min) in Group B (P < 0.0001). The post-intubation HR (75 ± 6.48 beats/min) decreased significantly in comparison with baseline value (77.466 ± 5.75 beats/min) in Group A (P value 0.005). However, no patient developed bradycardia (HR <60 beats/min) requiring atropine.

Table 3.

Baseline and post-intubation MAP, baseline and post-intubation HR

Discussion

The ASA difficult airway algorithm emphasizes on awake intubation and tracheostomy as primary or alternate options in difficult airway situations.[10] Now-a-days, AFOI is the preferred method for securing a difficult airway. Various drugs have been tried to achieve conscious sedation during AFOI.

Fentanyl is a phenylpiperidine derivative of synthetic opioid, which provides mild sedation, analgesia along with hemodynamic stability, which are beneficial for AFOI but there is a risk of respiratory depression, nausea and vomiting and chest wall rigidity.[11,12,13]

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective, centrally acting α-2 agonist. It acts on presynaptic α-2 receptors to provide negative feedback causing less neurotransmitter (norepinephrine, epinephrine) available at post-synaptic α-1 receptors. It produces hypnosis, amnesia, analgesia, anxiolysis, sympatholysis and antisialogogue effects all of which are desirable during AFOI.[14] Dexmedetomidine induces sedation involving activation of endogenous sleep promoting pathway through the post-synaptic α-2 receptors in the locus ceruleus, which modulates wakefulness. The major advantages of dexmedetomidine infusion during AFOI are a unique form of sedation where patients remain sleepy, but are easily aroused, cooperative with minimum respiratory impairment. The feasibility of dexmedetomidine has been recently studied either as a sole sedative agent or as an adjuvant during AFOI.[15,16]

We compared dexmedetomidine 1 mcg/kg (Group A) with fentanyl 2 mcg/kg (Group B) and found more favorable intubation conditions and better tolerance to intubation in dexmedetomidine group than fentanyl group. Most of the patients (28 out of 30) of Group A, but only three patients of Group B had cough score ≤2. Poor post-intubation Score (≥2) was found in 27 patients of Group B and six patients of Group A (P < 0.0001).

Chu et al.[10] observed better tolerance to intubation without respiratory depression and upper airway obstruction in dexmedetomidine group (1 mcg/kg) compared with fentanyl group (1 mcg/kg). In our study, dexmedetomidine produced better intubating conditions than fentanyl used in dose of 2 mcg/kg. Dexmedetomidine has also been proved as an effective agent for AFOI in certain difficult airway scenarios.[17,18,19] Bergese et al.[20] noted that dexmedetomidine at 1 mcg/kg bolus was safe and beneficial for patients undergoing AFOI even without airway nerve block or topical anesthesia.

Bergese et al.[20] found that dexmedetomidine in combination with low dose midazolam is more effective than midazolam alone for sedation in AFOI. However, dexmedetomidine dose in excess of 1 mcg/kg/h with midazolam produced airway obstruction, which was managed by simple chin lift.

In our study, all patients achieved RSS ≥2, but patients of Group A achieved a higher score (3 ± 0.371) than Group B (2.07 ± 0.254) (P < 0.0001).

Ryu et al.[21] compared remifentanil with dexmedetomidine for conscious sedation during bronchoscopy. They found that there were no significant difference of sedation level, MAP, HR and patient satisfaction score (P > 0.05) but cough score and incidence of desaturation was significantly lower (P < 0.01) in dexmedetomidine group than remifentanil group.

In our study, patients of dexmedetomidine group showed better hemodynamic stability. Initial HR and MAP were similar in both groups. There was a significant change of HR in the post-intubation period in comparison with the baseline value in Group B, which was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). However, there was no significant changes of HR in the post-intubation period in comparison with baseline value in Group A. There was no incidence of bradycardia in any patient. The hemodynamic effects of dexmedetomidine results from a decrease in noradrenaline release diminished centrally mediated sympathetic tone and increased vagal activity. Dexmedetomidine infusion may cause bradycardia, atrial fibrillation, hypotension or hypertension particularly in higher dose.[22] However, there are reports of unaltered hemodynamics even in higher doses of dexmedetomidine infusion.[23] Yavascaoglu et al. reported that dexmedetomidine prevented the hemodynamic response to tracheal intubation more effectively than esmolol.[24] There are various reports of attenuation of stress response to endotracheal intubation in patients scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft surgery.[25,26] Peden et al. observed bradycardia and sinus arrest in young volunteers following dexmedetomidine bolus and infusion and they suggested prevention with administration of glycopyrrolate prior to dexmedetomidine infusion.[27] We administered glycopyrrolate as an antisialogogue before bronchoscopy procedure, which may have prevented such side-effects. There was no incidence of hypotension, hypertension, bradycardia or arrhythmia in dexmedetomidine group.

Fentanyl suppresses respiratory center, produces chest wall rigidity and there is a risk of hypoxia and desaturation. The unique property of dexmedetomidine is that it produces sedation without airway obstruction and respiratory depression. We observed that the incidence of desaturation was less in Group A (four patients) than Group B (25 patients) (P < 0.0001). These patients were managed by administration of oxygen through the port of the bronchoscope.

Thus to conclude dexmedetomidine is more effective than fentanyl during AFOI, as it provides better intubation condition, hemodynamic stability and adequate sedation without desaturation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Rosenblatt WH. Airway management. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, et al., editors. Clinical Anesthesia. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 595–638. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergese SD, Khabiri B, Roberts WD, Howie MB, McSweeney TD, Gerhardt MA. Dexmedetomidine for conscious sedation in difficult awake fiberoptic intubation cases. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19:141–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lallo A, Billard V, Bourgain JL. A comparison of propofol and remifentanil target-controlled infusions to facilitate fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:852–7. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318184eb31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rai MR, Parry TM, Dombrovskis A, Warner OJ. Remifentanil target-controlled infusion vs propofol target-controlled infusion for conscious sedation for awake fibreoptic intubation: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:125–30. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey PL, Pace NL, Ashburn MA, Moll JW, East KA, Stanley TH. Frequent hypoxemia and apnea after sedation with midazolam and fentanyl. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:826–30. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199011000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Struys MM, Vanluchene AL, Gibiansky E, Gibiansky L, Vornov J, Mortier EP, et al. AQUAVAN injection, a water-soluble prodrug of propofol, as a bolus injection: A phase I dose-escalation comparison with DIPRIVAN (part 2): Pharmacodynamics and safety. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:730–43. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200510000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, Goodwin R. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone. Br Med J. 1974;2:656–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5920.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue FS, He N, Liao X, Xu XZ, Xu YC, Yang QY, et al. Clinical assessment of awake endotracheal intubation using the lightwand technique alone in patients with difficult airways. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:408–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai CJ, Chu KS, Chen TI, Lu DV, Wang HM, Lu IC. A comparison of the effectiveness of dexmedetomidine versus propofol target-controlled infusion for sedation during fibreoptic nasotracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:254–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu KS, Wang FY, Hsu HT, Lu IC, Wang HM, Tsai CJ. The effectiveness of dexmedetomidine infusion for sedating oral cancer patients undergoing awake fibreoptic nasal intubation. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:36–40. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32832e0d2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–77. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200305000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang SY, Mei Y, Sheng H, Li Y, Han R, Quan CX, et al. Tramadol combined with fentanyl in awake endotracheal intubation. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5:270–7. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.03.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhasmana S, Singh V, Pal US. Awake blind nasotracheal intubation in temporomandibular joint ankylosis patients under conscious sedation using fentanyl and midazolam. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010;9:377–81. doi: 10.1007/s12663-010-0159-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall JE, Uhrich TD, Barney JA, Arain SR, Ebert TJ. Sedative, amnestic, and analgesic properties of small-dose dexmedetomidine infusions. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:699–705. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200003000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avitsian R, Lin J, Lotto M, Ebrahim Z. Dexmedetomidine and awake fiberoptic intubation for possible cervical spine myelopathy: A clinical series. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2005;17:97–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ana.0000161268.01279.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann MM, Davio MB, Macknet MR, Applegate RL., 2nd Dexmedetomidine for awake fiberoptic intubation in a parturient with spinal muscular atrophy type III for cesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2009;18:403–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maroof M, Khan RM, Jain D, Ashraf M. Dexmedetomidine is a useful adjunct for awake intubation. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:776–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03016576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant SA, Breslin DS, MacLeod DB, Gleason D, Martin G. Dexmedetomidine infusion for sedation during fiberoptic intubation: A report of three cases. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16:124–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2003.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stamenkovic DM, Hassid M. Dexmedetomidine for fiberoptic intubation of a patient with severe mental retardation and atlantoaxial instability. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:1314–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergese SD, Patrick Bender S, McSweeney TD, Fernandez S, Dzwonczyk R, Sage K. A comparative study of dexmedetomidine with midazolam and midazolam alone for sedation during elective awake fiberoptic intubation. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryu JH, Lee SW, Lee JH, Lee EH, Do SH, Kim CS. Randomized double-blind study of remifentanil and dexmedetomidine for flexible bronchoscopy. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:503–11. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jorden VS, Pousman RM, Sanford MM, Thorborg PA, Hutchens MP. Dexmedetomidine overdose in the perioperative setting. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:803–7. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venn RM, Grounds RM. Comparison between dexmedetomidine and propofol for sedation in the intensive care unit: Patient and clinician perceptions. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:684–90. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yavascaoglu B, Kaya FN, Baykara M, Bozkurt M, Korkmaz S. A comparison of esmolol and dexmedetomidine for attenuation of intraocular pressure and haemodynamic responses to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25:517–9. doi: 10.1017/S0265021508003529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sulaiman S, Karthekeyan RB, Vakamudi M, Sundar AS, Ravullapalli H, Gandham R. The effects of dexmedetomidine on attenuation of stress response to endotracheal intubation in patients undergoing elective off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Card Anaesth. 2012;15:39–43. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.91480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menda F, Köner O, Sayin M, Türe H, Imer P, Aykaç B. Dexmedetomidine as an adjunct to anesthetic induction to attenuate hemodynamic response to endotracheal intubation in patients undergoing fast-track CABG. Ann Card Anaesth. 2010;13:16–21. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.58829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peden CJ, Cloote AH, Stratford N, Prys-Roberts C. The effect of intravenous dexmedetomidine premedication on the dose requirement of propofol to induce loss of consciousness in patients receiving alfentanil. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:408–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.01553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]