Abstract

Background and Aims:

Supraglottic airway devices have been established in clinical anesthesia practice and have been previously shown to be safe and efficient. The objective of this prospective, randomized trial was to compare I-Gel with LMA-Proseal in anesthetized spontaneously breathing patients.

Material and Methods:

Sixty patients undergoing short surgical procedures were randomly assigned to I-gel (Group I) or LMA- Proseal (Group P). Anesthesia was induced with standard doses of propofol and the supraglottic airway device was inserted. We compared the ease and time required for insertion, airway sealing pressure and adverse events.

Results:

There were no significant differences in demographic and hemodynamic data. I-gel was significantly easier to insert than LMA-Proseal (P < 0.05) (Chi-square test). The mean time for insertion was more with Group P (41 + 09.41 secs) than with Group I (29.53 + 08.23 secs) (P < 0.05). Although the airway sealing pressure was significantly higher with Group P (25.73 + 02.21 cm of H2O), the airway sealing pressure of Group I (20.07 + 02.94 cm of H2O) was very well within normal limit (Student's t test). The success rate of first attempt insertion was more with Group I (P < 0.05). There was no evidence of airway trauma, regurgitation and aspiration. Sore throat was significantly more evident in Group P.

Conclusion:

I-Gel is a innovative supraglottic device with acceptable airway sealing pressure, easier to insert, less traumatic with lower incidence of sore throat. Hence I-Gel can be a good alternative to LMA-Proseal.

Keywords: Airway sealing pressure, I-gel, laryngeal mask airway-Proseal, supraglottic airway device

Introduction

It has become something of a holy grail in recent years to maintain airway patency with supraglottic airway devices especially LMA-Proseal in day care short surgical procedures without the use of the neuromuscular blockade, in order to reduce the postoperative hospital stay and the postoperative complaints of sore throat.[1] The safety and efficacy of I-gel is yet to be explored. Since LMA-Proseal has almost similar design as I-gel, we decided to compare both these devices.

I-gel is a novel supraglottic airway device with anatomically designed, non-inflatable mask, which is soft gel like and transparent made of medical grade thermoplastic elastomer called styrene ethylene butadiene styrene. The soft noninflatable cuff fits snugly onto the perilaryngeal framework and its tip lies in the proximal opening of the esophagus, thus isolating oropharyngeal opening from the laryngeal opening. The device has a buccal cavity stabilizer which has a propensity to adapt its shape to the oropharyngeal curvature of the patient. This buccal cavity stabilizer houses airway tubing and a separate gastric channel.[2,3,4]

In this prospective randomized single blinded open study, we have compared the safety and efficacy of I-gel and LMA-Proseal in terms of ease, time and the attempts required for insertion, airway sealing pressure and airway complications.

Material and Methods

After approval from the institution's ethics committee, written informed, valid consent was obtained from all patients after explaining the study protocol.

Sixty patients of either sex, 18-60 years, American Society of Anesthesiologists Grade I/II undergoing short surgical procedures lasting for 30-120 min were included in the study.

Patients with anticipated difficult airway, restricted mouth opening, pregnant females, cervical spine disease, obese with body mass index >30 kg/m2 and patients with history of regurgitation were excluded from the study.

Patients were randomly allocated into two groups each based on the computer generated codes. Group I in whom I-Gel was inserted and Group P in whom LMA-Proseal was inserted. Anesthesiologist in post-anesthesia care unit monitoring the post-operative parameters and incidence of sore throat, and the patient were all blinded to the group assignment.

Pre-anesthetic assessment included medical/surgical history, general/systemic examination, airway examination and investigations, such as complete hemogram, chest X-ray and electrocardiogram.

After peripheral venous cannulation, monitors including blood pressure (BP) cuff, cardioscope, and pulse oximeter were attached and baseline parameters such as pulse, BP, oxygen saturation, and respiratory rate were noted.

After standard premedication with injection glycopyrrolate 0.004 mg/kg, ondansetron 0.08 mg/kg, ranitidine 1 mg/kg, midazolam 0.02 mg/kg and fentanyl 2 mcg/kg, all patients were pre-oxygenated with 100% oxygen for 3 min. Each patient then received induction dose of injection propofol (2-2.5 mg/kg) until the loss of eyelash reflex and achievement of adequate jaw relaxation. To prevent bias, device was inserted by a qualified anesthesiologist with minimum 2 years’ experience. The patient's head was placed in sniffing the morning air position. The supraglottic airway device was inserted after lubricating the cuff with a water based jelly. LMA-Proseal cuff was inflated with half the recommended volume of air and in case of inadequate seal entire recommended volume of air was used to inflate the cuff. In case of further leak, the device was removed and one size bigger was inserted. Additional doses of propofol were used in case of reinsertion if required. The device was then connected to the breathing circuit and capnometer assembly and secured after confirming bilaterally equal air entry. Nasogastric tube was inserted. An effective airway was confirmed from the bilaterally symmetrical chest movements, square wave form on the capnograph and a normal saturation.

Ease of insertion was defined as no resistance to the insertion of device in the pharynx in single attempt. The time taken for the insertion of device was noted. It was the time from the end of the propofol bolus to the connection of the airway to the breathing circuit and square wave capnograph.

The airway sealing pressure was determined by manometer stabilization method. After closing the expiratory valve of the circle system at a fixed gas flow of 3 L/min, the pressure manometer was observed on positive pressure ventilation and the point where equilibrium was achieved was taken as the sealing pressure.

If an effective airway was not achieved then manipulations were done in the form of increasing the depth of insertion, jaw thrust, or chin lift or changing the size of the device.

The device insertion was abandoned after three unsuccessful attempts. Then, patient was given muscle relaxant and trachea was intubated with endotracheal tube.

Anesthesia was maintained on oxygen, nitrous oxide and propofol infusion with spontaneous respiration.

At end of the procedure, all the patients were ventilated with 100% oxygen during emergence from anesthesia. The device was removed when the patient was able to open the mouth on command. The patient was inspected for any injury to lips, teeth or tongue and the device was inspected for the presence of any blood stains. The mask of the supraglottic device was inspected for the presence of any gastric contents to confirm regurgitation. All the patients were observed for a period of 24 h for any complaints of sore throat. Sore throat in the postoperative period was treated using warm saline nebulization and in patients with sore throat 24 h later warm saline gargles were advised. Laryngospasm was given standard treatment. We gave 100% oxygen followed by injection scoline 0.5 mg/kg. Hiccups were tackled by increasing the depth of anesthesia by increasing the maintenance dose of Injection propofol.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was calculated based on the results of previous study[5] to detect a projected difference in airway sealing pressure of 30% between groups with 80% power and 5% alpha error and a reported difference[5] in airway sealing pressure of 15% between two groups, a sample size 22 patients were required, which was rounded off to 30 patients in each group.

The two groups were compared with each other in terms of age, weight, and sex. The statistical test used was Unpaired Student's t-test for age and weight. For qualitative data like the sex of the patient the statistical test employed was Chi-square test.

Hemodynamic parameters such as mean heart rate, BP both systolic and diastolic, respiratory rate, SpO2 and end tidal CO2 were compared using analysis of variance.

The mean time required for insertion and the mean seal pressure was compared using unpaired Student's t-test. The ease of insertion, attempts required for insertion, airway manipulations and the incidence of adverse events were compared using Chi-square test. In all the parameters, P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

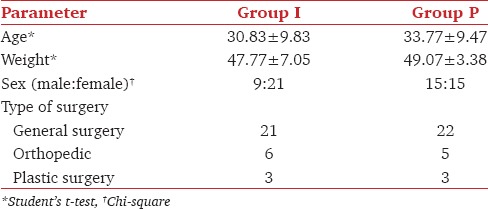

The demographic profile was comparable among both groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data

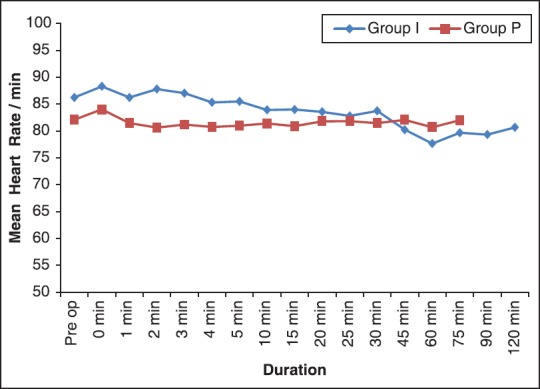

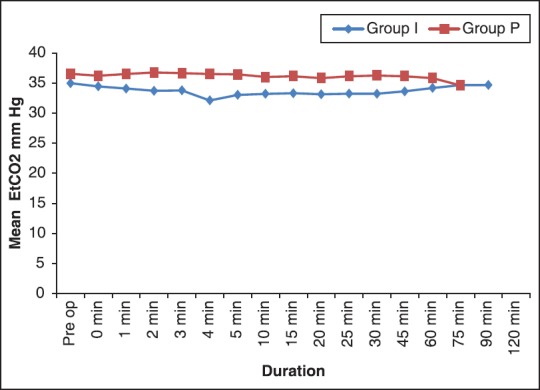

In both groups, the mean heart rate [Figure 1], other hemodynamic parameters and end-tidal CO2[Figure 2] were comparable.

Figure 1.

Comparison of changes in mean heart rate between two groups

Figure 2.

Comparison of changes in mean EtCO2 between two groups

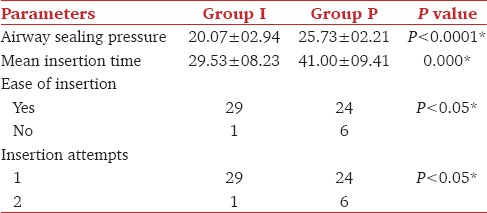

Higher airway sealing pressure was noted with Group P (25.73 ± 02.21) as compared to Group I (20.07 ± 02.94) and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.0001*). I-gel was faster and easier to insert than LMA-Proseal and this difference was statistically significant [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of airway sealing pressure, ease of insertion and insertion attempts

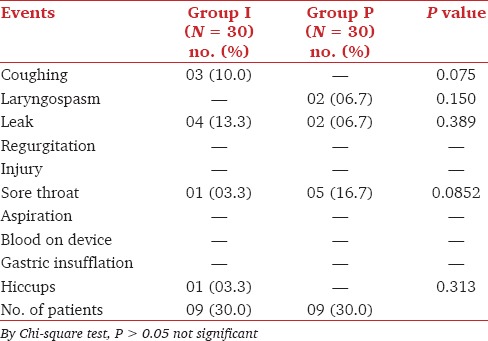

Statistically, insignificant number of adverse effects were observed in 30% of the total cases from both groups. Out of these most common was sore throat and leak followed by coughing, laryngospasm and hiccups. There was no evidence of injury, regurgitation, aspiration, blood on device, and gastric insufflation [Table 3].

Table 3.

Profile of adverse events

Discussion

Insertion of I-gel was easier and faster as compared to LMA-Proseal. LMA-Proseal is a complex device requiring an introducer for insertion, while an I-gel can be inserted without an introducer. As no cuff inflation is required in the I-gel, shorter time was required to achieve an effective airway by many investigators.[5,6]

In 29/30 cases, I-gel was successfully inserted in first attempt, only once second attempt was required, whereas in LMA-Proseal first attempt was successful in 24/30 cases and six cases required a second attempt. The difference was clinically as well as statistically significant [Table 2]. There are many studies comparing LMA-Proseal with Classic LMA, in which they have observed lower first attempt insertion success with LMA Proseal.[7,8,9] The common reason which was stated was that when deflated, the semi — rigid distal end of the drain tube formed the leading edge of the LMA-Proseal, which was more rigid as compared to the softer I-gel. This factor could contribute to the difficult insertion of LMA-Proseal.[8]

Levitan and Kinkle presumed that on insertion of LMA with inflatable mask the deflated leading edge of the mask can catch the edge of the epiglottis and cause it to downfold or impede proper placement beneath the tongue.[10] Brimacombe et al. presumed that the difficulty in inserting the LMA-Proseal was caused by larger cuff impeding digital intra-oral positioning and propulsion into the pharynx, the lack of backplate making cuff more likely to fold over at the back of the mouth.[9,11]

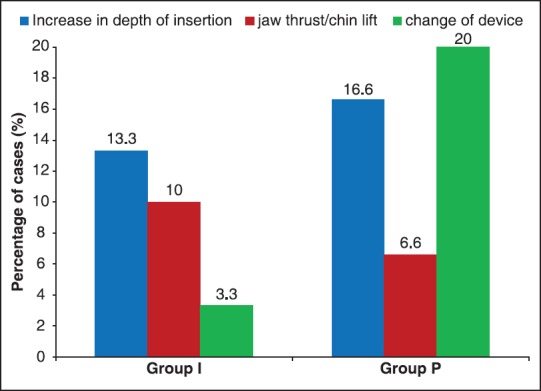

Airway manipulations were required in both groups to achieve an effective airway. The commonest manipulation required to achieve effective airway in Group I was increasing the depth of insertion ([5/30], 13.3%), whereas in the Group P, the device had to be changed ([6/30], 20%). The overall requirement of manipulations was less in the Group I ([8/30], 26.66%) as compared to Group P ([13/30], 43.33%) [Figure 3]. Kannaujia et al. also reported similar findings with respect to I-gel.[6]

Figure 3.

Profile of airway manipulations required

The mean airway sealing pressure with I-gel was 20.07 ± 02.94 cm H2O, and with LMA-Proseal 25.73 ± 02.21 cm of H2O which was statistically significant (P = 0.0000*) [Table 2], but it was not clinically significant. The higher values of EtCO2 among the LMA-Proseal group can explain the high airway sealing pressure and a better seal provided by it. Though the seal pressure of I-gel was lower than that of LMA-Proseal, it was enough to provide optimum ventilation.

Gabbott et al. also concluded that I-gel provides a good airway sealing pressure which improved over time and may be due to the thermoplastic properties of gel cuff which forms an effective seal around the larynx after warming to body temperature.[12] Various studies have been conducted comparing the seal pressures of I-gel with other LMA's, which conclude that an I-gel has an airway sealing pressure almost similar to the LMA-Proseal and more than the Classic LMA and LMA-Unique, hence can be used for positive pressure ventilation without the risk of aspiration.[13,14,15]

We compared the incidence of adverse effects intraoperatively, during emergence and in the postoperative period. Intraoperatively leak was present in 4/30 (13.3%) cases of the I-gel and 2/30 (6.7%) cases with the LMA-Proseal. The leak was diagnosed by the audible noise during assisted ventilation. The lower incidence of leak with the LMA-Proseal can be attributed to the higher airway sealing pressure. Though there was leak, good oxygenation and ventilation was maintained with both devices. Our results were in concordance with those found by Gasteiger et al.[16]

There was no evidence of regurgitation and aspiration with either of the devices. In our study, we included only elective patients who were adequately fasting preoperatively and all the patients had nasogastric tube in situ so none of the patients had episode of regurgitation. There was no evidence of injury to lip, teeth or tongue, and blood on either device.

There was no incidence of gastric insufflation with either device probably due to a good seal of ventilation around the laryngeal inlet and presence of nasogastric tube through the gastric channel. Brimacombe et al.[17] described one case of gastric insufflation with LMA-Proseal, wherein the tip of the LMA-Proseal had folded posteriorly after insertion resulting in the failure of the drainage tube to perform its intended function.

In the I-gel group, 3.3% cases complained of sore throat immediately in the postoperative period whereas in the LMA-Proseal group 16.7% patients complained of sore throat. 24 h later the same patient had sore throat in I-gel group where as in the LMA-Proseal group 23.3% patients complained of throat discomfort. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05*). Soliveres et al. also found that the use of LMA-Proseal produces more sore throat as compared to the I-gel.[18] Various studies have reported similar findings wherein the incidence of sore throat is minimal with I-gel in comparison with other supraglottic airway devices.[5,14,19,20] The lower incidence of sore throat in our study can be attributed to the soft seal non inflatable mask of I-gel. I-gel being a supraglottic airway device without an inflatable mask has some potential advantage of easier insertion and minimal tissue compression[21,22,23] whereas supraglottic airway device with inflatable cuff like the LMA-Proseal in our study can absorb anesthetic gases leading to increased mucosal pressure.[24]

Conclusion

I-gel is a simple device which is easy to insert without much of manipulations rapidly. It has a potential advantage of effective seal pressure which is less as compared to LMA-Proseal, but is enough to prevent aspiration and maintain an effective ventilation and oxygenation. Lack of inflatable cuff also resulted in lower incidence of sore throat. Thus an I-gel can be a useful tool for maintaining airway and intermittent positive pressure ventilation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Brandt L. The first reported oral intubation of the human trachea. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:1198–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.I-gel supraglottic airway device with non inflatable cuff Org. [Last accessed on 2011 Nov 29]. Available from: http://www.i-gel.com/products/theinventor/

- 3.I-gel User-guide. [Last accessed on 2011 Nov 29]. Available from: http://www.i-gel.com/lib/docs/userguides/i-gel_User_Guide_English.pdf .

- 4.I-gel supraglottic airway device with Non inflatable cuff. [Last accessed on 2011 Nov 29]. Available from: http://www.i-gel.com/faq/i-gel .

- 5.Singh I, Gupta M, Tandon M. Comparison of clinical performance of I-gel with LMA-proseal in elective surgeries. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:302–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannaujia A, Srivastava U, Saraswat N, Mishra A, Kumar A, Saxena S. A preliminary study of I-gel: A new supraglottic airway device. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:52–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu PP, Brimacombe J, Yang C, Shyr M. ProSeal versus the Classic laryngeal mask airway for positive pressure ventilation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:824–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.6.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook TM, Nolan JP, Verghese C, Strube PJ, Lees M, Millar JM, et al. Randomized crossover comparison of the proseal with the classic laryngeal mask airway in unparalysed anaesthetized patients. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:527–33. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brimacombe J, Keller C. The ProSeal laryngeal mask airway: A randomized, crossover study with the standard laryngeal mask airway in paralyzed, anesthetized patients. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:104–9. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200007000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levitan RM, Kinkle WC. Initial anatomic investigations of the I-gel airway: A novel supraglottic airway without inflatable cuff. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:1022–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brimacombe J, Keller C, Fullekrug B, Agrò F, Rosenblatt W, Dierdorf SF, et al. A multicenter study comparing the ProSeal and Classic laryngeal mask airway in anesthetized, nonparalyzed patients. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:289–95. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200202000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabbott DA, Beringer R. The iGEL supraglottic airway: A potential role for resuscitation? Resuscitation. 2007;73:161–2. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin WJ, Cheong YS, Yang HS, Nishiyama T. The supraglottic airway I-gel in comparison with ProSeal laryngeal mask airway and classic laryngeal mask airway in anaesthetized patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:598–601. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283340a81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmy AM, Atef HM, El-Taher EM, Henidak AM. Comparative study between I-gel, a new supraglottic airway device, and classical laryngeal mask airway in anesthetized spontaneously ventilated patients. Saudi J Anaesth. 2010;4:131–6. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.71250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber U, Oguz R, Potura LA, Kimberger O, Kober A, Tschernko E. Comparison of the i-gel and the LMA-Unique laryngeal mask airway in patients with mild to moderate obesity during elective short-term surgery. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:481–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasteiger L, Brimacombe J, Perkhofer D, Kaufmann M, Keller C. Comparison of guided insertion of the LMA ProSeal vs the i-gel. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:913–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brimacombe J, Keller C, Berry A. Gastric insufflation with the ProSeal laryngeal mask. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1614–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200106000-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soliveres J, Balaguer J, Richart MT, Sanchez J, Solaz C. Airway morbidity after use of the laryngeal mask airway LMA Proseal vs. I-gel. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:257–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gatward JJ, Cook TM, Seller C, Handel J, Simpson T, Vanek V, et al. Evaluation of the size 4 i-gel airway in one hundred non-paralysed patients. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:1124–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keijzer C, Buitelaar DR, Efthymiou KM, Srámek M, ten Cate J, Ronday M, et al. A comparison of postoperative throat and neck complaints after the use of the i-gel and the La Premiere disposable laryngeal mask: A double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1092–5. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b6496a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Twigg S, Brown JM, Williams R. Swelling and cyanosis of the tongue associated with use of a laryngeal mask airway. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:449–50. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0002800417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart A, Lindsay WA. Bilateral hypoglossal nerve injury following the use of the laryngeal mask airway. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:264–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2002.02231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowinger D, Benjamin B, Gadd L. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury caused by a laryngeal mask airway. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1999;27:202–5. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9902700214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouellette RG. The effect of nitrous oxide on laryngeal mask cuff pressure. AANA J. 2000;68:411–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]