Abstract

Drug efflux protein complexes confer multidrug resistance on bacteria by transporting a wide spectrum of structurally diverse antibiotics. Moreover, organisms can only acquire resistance in the presence of an active efflux pump. The substrate range of drug efflux pumps is not limited to antibiotics, but it also includes toxins, dyes, detergents, lipids, and molecules involved in quorum sensing; hence efflux pumps are also associated with virulence and biofilm formation. Inhibitors of efflux pumps are therefore attractive compounds to reverse multidrug resistance and to prevent the development of resistance in clinically relevant bacterial pathogens. Recent successes on the structure determination and functional analysis of the AcrB and MexB components of the AcrAB-TolC and MexAB-OprM drug efflux systems as well as the structure of the fully assembled, functional triparted AcrAB-TolC complex significantly contributed to our understanding of the mechanism of substrate transport and the options for inhibition of efflux. These data, combined with the well-developed methodologies for measuring efflux pump inhibition, could allow the rational design, and subsequent experimental verification of potential efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs). In this review we will explore how the available biochemical and structural information can be translated into the discovery and development of new compounds that could reverse drug resistance in Gram-negative pathogens. The current literature on EPIs will also be analyzed and the reasons why no compounds have yet progressed into clinical use will be explored.

Keywords: multidrug resistance, drug efflux, efflux pump inhibitor, Gram-negative, pathogen, antimicrobial resistance

Introduction

Over the last two decades there has been a dramatic surge in the number of multidrug resistant bacteria, yet paradoxically the number of pharmaceutical companies developing new antimicrobial agents has dwindled during this same period. As a result, antibiotic resistance is now one of the world’s most pressing health problems (WHO, 2014). Therefore, new treatments to combat drug resistant bacteria are urgently needed if we do not want to return to the high mortality rates associated with infections during the pre-antibiotic era (Bush et al., 2011; WHO, 2014).

Hospital acquired pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumonia, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa which can cause life-threatening infections display high levels of antibiotic resistance (Poole, 2011; Bassetti et al., 2013). Resistance of K. pneumonia to carbapenems, the last resort treatment for severe infections, of up to 54% of cases were reported (WHO, 2014).

Recently a few new antibiotics have been approved for the use against Gram-positive organisms (Butler and Cooper, 2011). However, infections caused by Gram-negative pathogens proved much harder to treat due to the very high intrinsic drug resistance displayed by Gram-negative organisms. This intrinsic drug resistance is due to presence of an outer membrane which acts as a permeability barrier and by the expression of drug efflux pumps.

Drug efflux pumps are protein complexes which reside in the membrane and remove antimicrobials and toxins, thereby lowering their concentration inside the cell to sub-toxic levels (Poole, 2004, 2005; Piddock, 2006a; Nikaido and Pages, 2012). These proteins recognize and expel a wide range of structurally diverse antibiotics with different mechanisms and sites of action. The clinical implication of this substrate promiscuity is the development of multidrug resistance where a pathogen displays resistance against multiple classes of antimicrobials.

Apart from antibiotics drug efflux proteins can also transport antiseptics and disinfectants (Chuanchuen et al., 2003; Sanchez et al., 2005; Mima et al., 2007; Pumbwe et al., 2007), detergents (including naturally occurring bile salts; Rosenberg et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2005), fatty acids (Lee and Shafer, 1999; Lennen et al., 2013), heavy metals (Silver and Phung, 1996; Walmsley and Rosen, 2009), solvents (White et al., 1997; Ramos et al., 2002; Segura et al., 2012), and virulence factors (Piddock, 2006b). Therefore, drug efflux pumps are also important constituents of bacterial pathogenesis, virulence, and biofilm formation (Hirakata et al., 2002, 2009; Piddock, 2006b; Ikonomidis et al., 2008; Martinez et al., 2009; Baugh et al., 2012, 2014; Amaral et al., 2014). In addition, micro-organisms can only acquire resistance in the presence of drug efflux pumps (Lomovskaya and Bostian, 2006; Ricci et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2011; Piddock, 2014) as these non-specific pumps remove most compounds until the organism has had time to acquire resistance to an antibiotic through more specific adaptive mechanisms.

Despite their crucial role in bacterial pathogenesis and multidrug resistance there are currently no inhibitors for drug efflux pumps in clinical use. Therefore drug efflux pumps are attractive targets for inhibition. Efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) will (a) synergise with currently used antibiotics, (b) restore the efficacy of antibiotics to which resistance has arisen, (c) reduce the incidence of emergence of drug-resistant pathogens, (d) reduce the ability of pathogens to infect the host as the inhibition of efflux attenuates the bacterium, and (e) prevent the development of highly drug resistant biofilms

Drug Efflux Pumps in Gram-Negative Bacteria

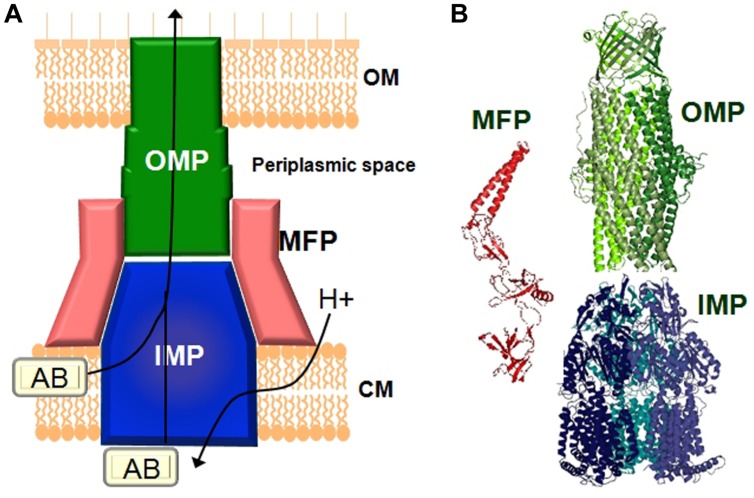

Gram-negative pathogens rely on tripartite protein assemblies that span their double membrane to pump antibiotics from the cell. The tripartite complex consists of an inner membrane protein (IMP) of the resistance nodulation cell division (RND) family, an outer-membrane protein (OMP), and a periplasmic membrane fusion protein (MFP) which connect the other two proteins (Figure 1). The inner-membrane protein catalyses drug/H+ antiport and is the part of the complex responsible for drug selectivity. The best studied tripartite drug efflux complexes are the AcrA-AcrB-TolC and MexA-MexB-OprM transporters from Escherichia coli and P. aeruginosa, respectively, (Du et al., 2013). The IMPs AcrB and MexB share 86% similarity and MexB can functionally substitute for AcrB (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2008; Welch et al., 2010). The asymmetric structure of the AcrB homotrimer and subsequent biochemical analysis revealed a functional rotating mechanism where the monomers cycle through the different states loose (L), tight (T), and open (O; Murakami et al., 2006; Seeger et al., 2006, 2008b). IMPs such as AcrB consist of a transmembrane domain and periplasmic domain. The drug efflux pathway from the periplasm/outer membrane leaflet through the periplasmic domain of AcrB has been the focus of many studies and are now relatively well-understood (Murakami, 2008; Seeger et al., 2008a; Eicher et al., 2009; Misra and Bavro, 2009; Nikaido and Takatsuka, 2009; Pos, 2009; Nikaido, 2011; Nikaido and Pages, 2012; Ruggerone et al., 2013a,b). Recently, it was also found that mutations at the cytoplasmic face of MexB affected transport of drugs with targets inside the cell (Ohene-Agyei et al., 2012). This raises the possibility that similar to the cytoplasmic pathway for Cu(II) in CusA (Delmar et al., 2014), MexB might also have the ability to remove antibiotics from the inner membrane leaflet/cytoplasm (Ohene-Agyei et al., 2012). Targeted geometric simulations showed that such a cytoplasmic pathway could be possible even though it would not necessarily out-compete the periplasmic channel for drug binding and transport (Phillips and Gnanakaran, 2015). Biochemical and structural analysis revealed that the perplasmic binding site in AcrB contains a shallow (proximal) and deep (distal) binding pocket separated by a switch loop (G-loop) consisting of residues 614–621 (Nakashima et al., 2011; Eicher et al., 2012; Cha et al., 2014). Conformational flexibility in this loop is necessary to move the substrate along the extended binding site. Mutations that change the small glycine residues in this loop to bulkier residues affects transport of larger macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin while the activity toward smaller compounds such as novobiocin, ethidium, and chloramphenicol remained unaffected (Bohnert et al., 2008; Wehmeier et al., 2009; Nakashima et al., 2011, 2013; Eicher et al., 2012). Therefore, EPIs would most effectively inhibit the efflux of different antibiotics by interaction with the switch loop.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation 48.5pcof a tripartite drug efflux complex. (A) The complex 48.5pcconsists of three proteins which span the inner-membrane (CM), the outer membrane (OM), and the periplasmic space. The inner-membrane protein (IMP), e.g., AcrB or MexB is responsible for substrate specificity and catalyzes ΔpH dependent drug transport. Examples of the outer membrane protein (OMP) are TolC or OprM. The periplasmic membrane fusion protein (MFP), e.g., AcrA or MexA connects the IMP and the OMP. (B) Structures of the individual components of the efflux pump. The MexA (pdb: 2V4D), MexB (pdb: 2V50), and OprM (pdb: 1WP1) proteins from Pseudomonas aeruginosa are given as examples.

Due to the complexity of these macromolecular structures progress on elucidating their assembly and structure was slow. Only very recently Du et al. (2014) used a creative approach of genetic fusion proteins to solve the first structure of a partially active, fully assembled, tripartite pump in the presence of a modulatory partner. This structure of AcrA–AcrB–AcrZ–TolC shed light on long disputed subunit stoichiometries and revealed that the complex assembles in a 3 : 6 : 3 ratio of AcrB : AcrA : TolC with one monomer of AcrZ bound to each subunit of AcrB. The role of the small protein AcrZ is not clear, however, as it alters the substrate specificity of AcrB (Hobbs et al., 2012) it most likely plays a modulatory role.

The structural similarity between transporters from different Gram-negative organisms means that EPIs developed against, e.g., the AcrA–AcrB–TolC efflux pump from E. coli would most likely be effective against other pathogens also. Our current understanding of the structure and function of RND efflux pumps from Gram-negative bacteria could therefore provide the basis for the informed and efficient design of inhibitors against these protein complexes.

Approaches to Inhibit Drug Efflux

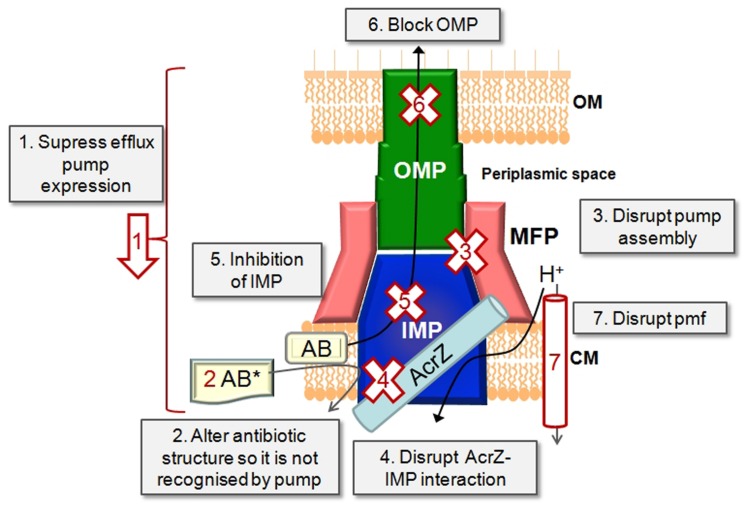

The expression, function and assembly of drug efflux pumps of the RND class can be targeted in several ways (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition strategies. Schematic representation of a tripartite drug efflux complex in complex with a small protein such as AcrZ. The possible approaches of inhibiting drug efflux are depicted.

Targeting the Regulatory Network that Controls the Expression of Efflux Pumps as Levels of Pump Expression are Controlled by Activators and Repressors

Some progress has already been made in understanding the regulation of efflux pump expression, e.g., expression of AcrB from Salmonella enterica (Blair et al., 2014) and the regulation of efflux pump expression in P. aeruginosa (Wilke et al., 2008; Starr et al., 2012; Hay et al., 2013; Purssell and Poole, 2013; Lau et al., 2014). The expression levels of efflux pumps could be measured by real time PCR or with green fluorescent protein reporter fusions (Bumann and Valdivia, 2007; Ricci et al., 2012). Both these methods are amenable to high-throughput processing.

Changing the Molecular Design of Old Antibiotics so that they are No Longer Recognized and Transported by the Efflux Pump

Given the wide range of compounds which could be recognized by drug efflux transporters, the plasticity in the binding sites, and the redundancy in aromatic residues in the binding pocket which could stabilize substrate binding (Du et al., 2013), this approach might prove a daunting task. In addition, altering the chemical structure of the antibiotic might render it less efficient against its intended cellular target. However, some progress has been made in this regard for a different class of drug efflux protein, the ATP binding cassette transporter, human P-glycoprotein where the substrate taxol was chemically modified so that P-glycoprotein no longer recognized it. This allowed the drug to cross the blood brain barrier and access its target receptor without being removed by P-glycoprotein (Rice et al., 2005).

Preventing the Assembly of the Efflux Pump Components into a Functional Tripartite Pump by Targeting Protein–Protein Interfaces

This is a very promising approach which is still under-developed due to the lack of information of how tripartite pumps assemble. However, Tikhonova et al. (2011) showed that designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) could inhibit AcrAB-TolC function by inhibiting the interaction between AcrA and AcrB. The recent structure of a complete tripartite drug efflux pump and the information gained from that also opens up exciting new possibilities (Du et al., 2014). The interaction of purified protein components of the pump with each other can be measured with surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The ability of efflux pumps to assemble in vivo can be measured by cross-linking in whole cells with subsequent co-purifying of the pump components (Welch et al., 2010).

Disrupting the Interaction Between AcrB and AcrZ

The exact role of AcrZ in drug efflux is still ill-defined. However, as AcrA–AcrB–TolC has a diminished ability to confer resistance to some drugs in the absence of AcrZ (Hobbs et al., 2012), this approach could be promising for restoring sensitivity to some antibiotics. Homologs of AcrZ are found in most Gram-negative bacteria, therefore the modulatory effect of RND class of transporters by small proteins is probably a widely conserved occurrence. The interaction between the IMP and a small protein such as AcrZ could be measured with SPR or with cross-linking in cells as mentioned above.

Directly Blocking the IMP with a High Affinity Competing Substrate or Trapping the IMP in an Inactive Conformation

The recent crystal structure of AcrB and MexB bound to an inhibitor (Nakashima et al., 2013) and the advances in our understanding of how drugs are bound makes this option very attractive (see Efflux Pump Inhibitors Against Gram-Negative Bacteria Identified So Far). The ability of compounds to inhibit antibiotic efflux can be measured using drug accumulation or drug efflux assays (see Inhibition of Substrate Transport), while direct interaction between the test compound and the IMP component could be determined with isothermal calorimetry (ITC) or SPR (Tikhonova et al., 2011).

Blocking the Exit Duct (the OMP)

A set of indole derivatives was designed based on the structure of TolC. These compounds were able to synergise with antibiotics and were reported to act on TolC specifically, presuming by preventing opening of the channel (Zeng et al., 2010). In addition, TolC from E. coli contains an electronegative entrance formed by an aspartate ring which is widely conserved throughout the TolC family and which could be a target for blocking by large cations (Andersen et al., 2002). The biggest challenge with this approach is achieving selectivity to the bacterial pores. Blocking of the OMP could be detected by inhibition of antibiotic efflux through the tripartite pump or by disruption of TolC-mediated conductance.

Depleting the IMP From the Energy Needed to Drive the Drug/H+ Antiport Reaction

The proton motive force (pmf) can easily be disrupted by the use of ionophores or compounds that disrupt the membrane integrity in one way or another. However, these effects are mostly not specific for bacterial membranes and hence compounds that act in this way would be cytotoxic to the host cells too. The magnitude of the pmf and the effect of test compounds on these could be determined by the use of fluorescent probes specific for the ΔΨ or ΔpH components of the pmf (Venter et al., 2003).

How Could EPIs be Identified?

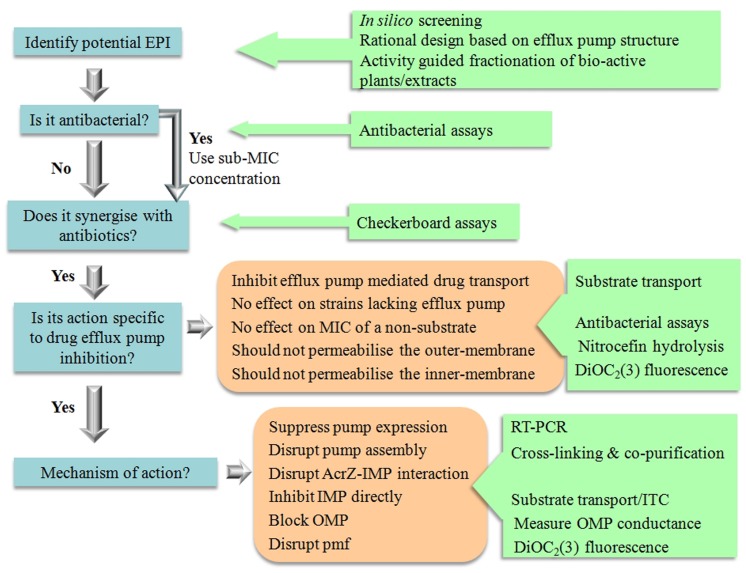

Significant effort went into the biochemical and structural characterization of drug efflux proteins from Gram-negative bacteria. Recent successes such as the structural determination of an intact pump and of IMPs bound to an inhibitor (Nakashima et al., 2013; Du et al., 2014) offer a solid platform for the rational design of EPIs using quantitative structure-activity relationship data (Ruggerone et al., 2013a; Wong et al., 2014; Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The tools for EPI discovery.

Recently we used in silico screening to identify compounds which would bind to AcrB with reasonable affinity. Of the roughly fifty compounds docked, six compounds were selected for further study. The docking allowed us to provide an order of efficiency of the compounds as potential EPIs. The biochemical data compared well with the predictions from the docking showing that in silico screening could be used as an effective screening tool to limit the amount of experiments needed or save on precious and hard earned purified natural products (Ohene-Agyei et al., 2014).

Another approach with good scope for success is investigating compounds purified from plants (Tegos et al., 2002). Traditional peoples have used plants to treat infections for 100s if not 1000s of years. In western medicine, plants are thus far an under-utilized source of chemical components in the treatment of infectious disease. Resistance to medicinal plant extracts have not been described yet and extracts of herbal medicines have been shown to potentiate antibiotic action in resistant pathogens (Garvey et al., 2011; Ohene-Agyei et al., 2014). Therefore, it is likely that as well as antibacterial chemicals, plants may also produce compounds that circumvent efflux-mediated resistance. Hence, activity guided fractionation can be used to identify the bio-active phytochemicals in plant extracts with EPI activity against Gram-negative organisms (Garvey et al., 2011).

Tools for Studying Efflux Pump Inhibitors

The most significant problem in current screening campaigns for EPIs is that in many cases the synergism observed could be attributed to non-specific damage to the bacterial membrane. This would be a strong indicator the compound would have similar activity against mammalian cells and hence would be cytotoxic. This was clearly the case for the EPI Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide (PAβN; Marquez, 2005; Lomovskaya and Zgurskaya, 2011).

Therefore, there need to be a thorough investigation in order to verify true EPI action (Figure 3). Compounds that permeabilise the membrane of Gram-negative organisms will always show synergism with antibiotics. For example, the modulatory effect of α-tocopherol in multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria such as P. aeruginosa and E. coli could most probably be attributed to the effects of α-tocopherol on the membrane (Andrade et al., 2014). It is therefore important that potential inhibitors are not only identified on their synergism with antibiotics, but that a subsequent biochemical assays are performed to determine that the compounds are truly acting by inhibiting drug efflux.

In order to qualify as an EPI a compound must be able to satisfy the following criteria as stipulated by Lomovskaya et al. (2001).

-

(a)

It must potentiate the activity of antibiotics to which a strain has developed resistance as a result of the expression of a drug efflux pump.

-

(b)

It should not have an effect on sensitive strains which lack the drug efflux pump.

-

(b)

It must not reduce the MIC of antibiotics which are not effluxed.

-

(d)

It must increase the level of accumulation and decrease the level of extrusion of compounds which are substrates of the efflux pump.

-

(e)

It must not permeabilise the outer membrane.

-

(f)

It must not affect the proton gradient across the inner membrane.

All the above criteria can be addressed with well-developed techniques as outlined below and in Figure 3, which would be amenable to scale-down for high throughput analysis.

Measuring Synergism

The first thing to do is to determine the MIC of the test compound using standard broth dilution assays (Lomovskaya et al., 2001; Welch et al., 2010; Ohene-Agyei et al., 2012, 2014). Ideally the compound should not be toxic to bacterial cells or only toxic at high concentrations. This would prevent resistance against the test compound from developing very quickly. The compound would then be used at concentrations below its MIC (usually 4× lower than the MIC) to test for synergism with antibiotics to which the organism has developed resistance. Synergism is best studied using checkerboard assays. These assays could be performed in a 96-well plate format with the antibiotic serially diluted along the ordinate and the test compound serially diluted along the abscissa (Lomovskaya et al., 2001; Orhan et al., 2005; Ohene-Agyei et al., 2014). The MIC of the antibiotic is determined in the presence of a range of different concentrations of the compound. Antibiotic-EPI interactions are subsequently classified on the basis of fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC). The FIC index is the sum of the FIC of each of the antibiotics, which in turn is defined as the MIC of the antibiotic when used in combination divided by the MIC of the antibiotic when used alone. The combination is considered synergistic when the ΣFIC is ≤0.5, indifferent when the ΣFIC is >0.5 to <2, and antagonistic when the ΣFIC is ≥2.

Ensuring the Compound has no Effect on Strains Which Lack the Drug Efflux Pump

An effective way of testing the effect of a compound on efflux pump mediated resistance is to use a wild-type antimicrobial resistant strain and a sensitive strain with a genomic deletion of the IMP. Checkerboard assays can be performed on the wild type strain to determine if MIC drop toward that of sensitive strain. Conversely the compound should not have an effect on the MIC of the sensitive strain.

However, it is important not to use a strain with a TolC deletion. TolC is a multi-functional protein that operates with the majority of MFP-dependent transporters encoded in the genome of E. coli (Zgurskaya et al., 2011). Results from TolC minus cells would therefore be complicated by effects which are not related to active drug efflux (Ohene-Agyei et al., 2014).

Inhibition of Substrate Transport

The ability of a potential EPI to inhibit substrate transport in a drug efflux pump can be measured by performing substrate accumulation assays or by measuring substrate efflux in the absence/presence of the putative EPI. Many fluorescent compounds are also substrates for drug efflux pumps. If these compounds undergo a change in fluorescence when bound to DNA/membrane lipids they can be used to measure the efflux activity of drug transporters. Many fluorescent compounds fulfill this role and are frequently used to measure drug efflux; examples are Hoechst 33342, berberine, ethidium bromide, TMA-DPH [1-(4-trimethylammoniumphenyl)-6-phenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene p-toluenesulfonate], N-phenylnaphthylamine and Nile Red which display enhanced fluorescence intensity when accumulated inside the cell or doxorubicin and rhodamine 6G for which accumulation inside cells results in quenching of the fluorescence signal (Lee et al., 2001; Lomovskaya et al., 2001; Seeger et al., 2008a,b; Ohene-Agyei et al., 2012, 2014; Cha et al., 2014). In drug accumulation assays the difference in rate of accumulation of the fluorescent compound between cells with and without an active efflux pump are used as an indication of efflux, since efflux will result in lower accumulation of compound. In drug efflux assays, the de-energized cells are pre-loaded with the fluorescent compound and then energized by the addition of glucose to catalyze drug efflux (observed as a drop in fluorescence). Drug influx assays are more straightforward and much quicker to perform than drug-efflux assays as de-energization and pre-loading can be time consuming. In addition, all the samples must be pre-loaded to the same level of fluorescence to avoid differences in efflux rate as a result of differences in the concentration of drug inside the cell. The main drawback of using fluorescent compounds to measure the effect of an EPI on drug efflux is that the potential EPI could be highly colored or fluorescent itself and thus interfere with the measurement. Recently, Bohnert et al. (2010) developed a method using Nile Red for efflux which are compatible with highly colored or fluorescent compounds.

Testing of Outer Membrane Permeabilization

The most effective method to measure outer membrane permeabilization is the nitrocefin hydrolysis method. Nitrocefin is a chromogenic β-lactam which changes from yellow (∼380 nm) to red (∼490 nm) when it is hydrolyzed by the periplasmic β-lactamase, hence nitrocefin hydrolysis can be followed by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm. If the test compound permeabilises the outer membrane, nitrocefin will diffuse more quickly over the membrane and hence the rate of nitrocefin hydrolysis will increase as a result (Lomovskaya et al., 2001; Ohene-Agyei et al., 2014). It is important to perform these essays in the presence of the ionophore CCCP to de-energize cells and prevent nictrocefin efflux.

Testing of Inner Membrane Permeabilization

Several methods exist to measure permeabilization of the inner-membrane. A DNA stain which does not penetrate the membrane of intact bacterial cells and which will undergo an increase in fluorescence quantum yield when bound to DNA such as propdium iodide or SYTOX Green could be used (Roth et al., 1997; Nakashima et al., 2011). SYTOX Green would be preferred for its sensitivity as it undergoes a >500-fold enhancement in fluorescence emission when bound to DNA.

Other methods to measure the intactness of the bacterial inner membrane involve the use or measurement of the pmf in E. coli. Opperman et al. (2014), employed an assay based on the uptake of [methyl-3H]β-D-thiogalactopyranoside ([3H]TMG) by the LacY permease. The activity of the lactose permease is dependent on the pmf as it catalysis substrate/H+ symport. Lomovskaya et al. (2001) probed the intracellular pH of E. coli cells by measuring the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) of the 31P in the inner-membrane. Although both these two methods are effective they are quite time consuming and require access to specialist equipment. The magnitude of the individual components of the pmf can be measured directly by a simple fluorescence assay utilizing the fluorescent membrane potential probe 3,3′-diethyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DIOC2(3); Venter et al., 2003). Moreover, the DIOC2(3) assay can easily be adapted to 96-well format for the quick analysis of test compounds on the inner membrane in high-throughput screening.

Use of a Non-Substrate

Another way of ruling out false positives and establishing that compounds do not act non-specifically is to measure the effect of the test compound on an antibiotic which is not an efflux pump substrate. For example our group used rifampicin, which is not transported by the AcrAB-TolC drug efflux pump from E. coli (Ohene-Agyei et al., 2014). The test compounds should not lower the MIC of rifampicin. Any reduction in the MIC of rifampicin would indicate that the compound does not potentiate antibiotic action by inhibition of efflux, but acts by indirect means such as permeabilization of the membrane.

EPIs Against Gram-Negative Bacteria Identified so Far

The first EPI to be identified against RND pumps in Gram-negative bacteria was the peptidomimetic PAβN, originally referred to as MC-2077110. PAβN was identified in a screen for levofloxacin potentiators against resistant P. aeruginosa. Unfortunately, in addition to efflux pump inhibition it also permeabilized the outer membrane (Lomovskaya et al., 2001). Derivatives of PAβN with reduced toxicity, enhanced stability, and better solubility were developed and advanced to the pre-clinical stage, however, failed due to toxicity issues (Marquez, 2005; Lomovskaya et al., 2006; Lomovskaya and Zgurskaya, 2011; Bhardwaj and Mohanty, 2012).

The structural basis for the inhibition of the RND transporters has been recently described with the publication of the crystal structures of AcrB from E. coli and MexB from P. aeruginosa bound to a pyridopyrimidine derivative D13–D900 (Nakashima et al., 2013). The inhibitor binding almost overlapped with the binding of the substrates minocycline and doxorubicin, while part of the inhibitor inserted into a narrow phenylalanine rich region in the deep binding pocket, termed the hydrophobic trap by the authors. The authors suggested that the inhibitor competitively inhibit substrate binding and hinders the functional rotation of the efflux pumps.

As there is only one structure of a RND protein bound to an inhibitor published to date, docking, and molecular simulation studies were used to investigate the putative binding modes of other inhibitors such as PAβN and NMP (Vargiu et al., 2014) while in silico screening also provided information on the binding of putative EPIs (Ohene-Agyei et al., 2014). Both PAβN an NMP were predicted to interact with the switch loop while D13–D9001and MBX2319 have more interactions with the hydrophobic trap first identified by Nakashima et al. (2013).

Table 1 summarizes the compounds reported to act as EPIs against Gram-negative organisms so far. The term EPI is used loosely here as some of the included compounds were identified based on their synergism with one or more antibiotic while no further analysis was performed to study the mechanism of inhibition or rule out non-specific effects such as membrane permeabilization.

Table 1.

Efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) against Gram-negative pathogens.

| Compound | Source | Protein/ Organism |

Actions1 | Essays performed | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Compounds | |||||

| Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide (PAβN; MC-207,110) | Synthetic | MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, MexEF-OprN (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) |

Synergise with fluoroquinolones | Antibacterial Synergism Substrate accumulation Inhibition of efflux Effect on outer-membrane |

Lomovskaya et al. (2001) |

| 7-nitro-8-methyl-4-[2′-(piperidino)ethyl] aminoquinoline | Alkylamino-quinolines | AcrAB-TolC (Enterobacter aerogenes) |

Reduced MIC of Cam, Nor, and Tet Increased Cam uptake |

Antibacterial Synergism Substrate accumulation |

Mallea et al. (2003) |

| 2,8-dimethyl-4-(2′-pyrrolidinoethyl)-oxyquinoline | Alkoxy-quinoline derivative | E. aerogenes Klebsiella pneumonia | Reduced MIC of Nor, Tet, Cam | Substrate accumulation Effect on membrane |

Chevalier et al. (2004) |

| 1-(1-Naphthylmethyl)-piperazine (NMP) | Synthetic | AcrAB, AcrEF (Escherichia coli) |

Reduction in MICs of Lev, Oxa, Rif, Cam, Clr Increased accumulation of ethidium |

Antibacterial Substrate accumulation |

Kern et al. (2006) |

| New chloroquinoline derivatives | Fluoroquinolones | AcrAB-TolC (E. aerogenes) |

Reduced MIC of Cam | Antibacterial Substrate accumulation |

Ghisalberti et al. (2006) |

| 3-amino-6-carboxyl-indole, 3-nitro-6-amino-indole | Designed and synthesized based on TolC structure | AcrAB-TolC(E. coli) | Reduced MIC of cam, tet, ery, and cip | Antibacterial Synergism |

Zeng et al. (2010) |

| 4-(3-morpholinopropylamino)-quinazoline | 4-alkylaminoquinazoline derivatives | AcrAB-TolC MexAB-OprM (E. coli P. aeruginosa) |

Reduced MIC of Cam, Nal, Nor, and Spfx Increased Cam uptake |

Antibacterial Synergism Substrate accumulation |

Mahamoud et al. (2011) |

| MBX2319 | Synthetic pyranopyridine | AcrB (E. coli) | Decreased MIC of Cip, Lev, and Prl | Docking Time kill assay Substrate accumulation Effect on outer-membrane Effect on inner-membrane |

Vargiu et al. (2014), Opperman et al. (2014) |

| 2-substituted benzothiazoles | Synthetic | AdeABC (Acinetobacter baumannii) |

Reduced MIC of cip | Pharmacophore hypothesis | Yilmaz et al. (2014) |

| Natural Compounds | |||||

| EA-371α and EA-371δ | Streptomyces MF-EA-371-NS1 | MexAB-OprM (P. aeruginosa) |

Reduce MIC of Lev | Synergism Substrate accumulation |

Lee et al. (2001) |

| Geraniol | Helichrysum italicum | E. coli P. aeruginosa A. baumanii | Reduced MIC of β-lactams, quinolones, and Cam | Antibacterial Synergism |

Lorenzi et al. (2009) |

| Plumbagin | Plumbago indica | AcrB (E. coli) | Reduced MIC of Ery, Cam, TPP, SDS, tet Inhibition of Nile Red efflux |

In silico screening Antibacterial Synergism Non-substrate control Inhibition of efflux Effect on outer-membrane |

Ohene-Agyei et al. (2014) |

| Nordihydroguaretic acid (NDGA) | Creosote bush | AcrB (E. coli) | Reduced MIC of Ery, Cam, Nov, Tet, and TPP | ||

| Shikonin | Lithospermum erythrorhizon | AcrB (E. coli) | Reduced MIC of TPP | ||

| (-)-epigallocatechin gallate EGCG | Green tea | Campylobacter spp. | Reduced MIC to Ery and Cip | Antibacterial Synergism |

Kurincic et al. (2012) |

| Curcumin | Curcuma longa (Zingiberaceae) | P. aeruginosa | Reduced MIC Mem, Carb, Caz, Gen, and Cip | Antibacterial Synergism |

Negi et al. (2014) |

| Lanatoside C and diadzein | Phytochemical | AcrB, MexB (E. coli, P. aeruginosa) | Reduced MIC of Lev and Carb Increased accumulation of EtBr |

High-throughput virtual screening Synergism Substrate accumulation |

Aparna et al. (2014) |

| 4-hydroxy-α-tetralone | Ammannia sp | E. coli | Reduced MIC of Tet | RT-PCR study In silico docking |

Dwivedi et al. (2014) |

| Non-antibacterial drugs | |||||

| Trimethoprim and Epinephrine | Small heterocyclic or nitrogen-containing drugs |

S. typhimurium E. cloacae S. marcescens P. aeruginosa K. pneumoniae E. coli |

Reduced MIC of Cip | Antibacterial Synergism Substrate accumulation Growth kinetics |

Piddock et al. (2010) |

| Chlorpromazine, Amitryptiline, Trans-chlorprothixene | Non-antibiotic drugs | P. aeruginosa | Reduced MIC of Pen, Cxm, and Tob | Antibacterial Synergism |

Kristiansen et al. (2010) |

| Sertraline | Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitors | AcrAB, AcrEF, MdtEF, and MexAB | Inhibition of Nile Red efflux | Inhibition of efflux RT-PCR |

Bohnert et al. (2011) |

| Artesunate | Anti-malarial drug | AcrAB-TolC (E. coli) | Reduced MIC ofβ-lactam antibiotic Increased Dau uptake Reduce mRNA expression |

Antibacterial Synergism Substrate accumulation RT-PCR |

Li et al. (2011) |

| Pimozide | Neuroleptic drug | AcrAB-TolC (E. coli) | Reduced MICs of Oxa and EtBr Inhibition of Nile rRed efflux |

Synergism Substrate efflux |

Bohnert et al. (2013) |

1Abbreviations used: Cam, Chloramphenicol; Carb , Carbanecillin; Caz , Ceftazidime; Cip , Ciprofloxacin; Clr , Clarithromycin; Cxm , Cefuroxime; Dau , Daunomycin; Ery , Erythromycin; EtBr , Ethidium Bromide; Gen, Gentamicin; Lev , Levofloxacin; Mem , Meropenem; Nal , Nalidixic acid; Nor , Norfloxacin; Oxa , Oxacillin; Pen , Penicillin; Prl , Piperacillin; Rif , Rifampicin; Spfx , Sparfloxacin; Tet , Tetracycline; Tob , Tobramycin; TPP , Triphenylphosphonium.

Conclusion

There are various papers reporting the ability of crude extracts from plants or other organisms to reduce antibiotic resistance that were not dealt with in this review. As can be seen from Table 1, there is also a sizable amount of pure compounds which were able to synergise with antibiotics against drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. However, the translation of these promising compounds into EPIs for clinical application is still lacking. The most probable reason for the discrepancies in lead compounds and final outcome is the deficiency of follow through from first identification of a compound with synergistic effects to identification of true EPI activity and providing a thorough investigation into mechanism of action. With this review we aimed to summarize the current knowledge of how drug efflux can be inhibited.

The tools necessary to identify, test and characterize the mechanism of action of a putative EPI were also provided in order to aid the discovery and development of EPIs with which we would be able to stem the tide of multidrug resistant Gram-negative infections.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Work in HV’s laboratory is funded by the University of South Australia, the Sansom Institute for Health Research and the Australian Research Council (Grant LE150100203 for screening of EPIs to HV). RM is the recipient of an Australian post-graduate award. HV and SM are co-recipients of a China–Australia Centre for Health Sciences Research Grant.

References

- Amaral L., Martins A., Spengler G., Molnar J. (2014). Efflux pumps of Gram-negative bacteria: what they do, how they do it, with what and how to deal with them. Front. Pharmacol. 4:168 10.3389/fphar.2013.00168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen C., Koronakis E., Hughes C., Koronakis V. (2002). An aspartate ring at the TolC tunnel entrance determines ion selectivity and presents a target for blocking by large cations. Mol. Microbiol. 44 1131–1139 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade J. C., Morais-Braga M. F., Guedes G. M., Tintino S. R., Freitas M. A., Menezes I. R., et al. (2014). Enhancement of the antibiotic activity of aminoglycosides by alpha-tocopherol and other cholesterol derivates. Biomed. Pharmacother. 68 1065–1069 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparna V., Dineshkumar K., Mohanalakshmi N., Velmurugan D., Hopper W. (2014). Identification of natural compound inhibitors for multidrug efflux pumps of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa using in silico high-throughput virtual screening and in vitro validation. PLoS ONE 9:e101840 10.1371/journal.pone.0101840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti M., Merelli M., Temperoni C., Astilean A. (2013). New antibiotics for bad bugs: where are we? Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 12 22 10.1186/1476-0711-12-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh S., Ekanayaka A. S., Piddock L. J., Webber M. A. (2012). Loss of or inhibition of all multidrug resistance efflux pumps of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium results in impaired ability to form a biofilm. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67 2409–2417 10.1093/jac/dks228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh S., Phillips C. R., Ekanayaka A. S., Piddock L. J., Webber M. A. (2014). Inhibition of multidrug efflux as a strategy to prevent biofilm formation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69 673–681 10.1093/jac/dkt420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj A. K., Mohanty P. (2012). Bacterial efflux pumps involved in multidrug resistance and their inhibitors: rejuvinating the antimicrobial chemotherapy. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 7 73–89 10.2174/157489112799829710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair J. M., Smith H. E., Ricci V., Lawler A. J., Thompson L. J., Piddock L. J. (2014). Expression of homologous RND efflux pump genes is dependent upon AcrB expression: implications for efflux and virulence inhibitor design. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70 424–431 10.1093/jac/dku380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert J. A., Karamian B., Nikaido H. (2010). Optimized Nile Red efflux assay of AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux system shows competition between substrates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54 3770–3775 10.1128/aac.00620-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert J. A., Schuster S., Kern W. V. (2013). Pimozide Inhibits the AcrAB-TolC Efflux Pump in Escherichia coli. Open Microbiol. J. 7 83–86 10.2174/1874285801307010083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert J. A., Schuster S., Seeger M. A., Fahnrich E., Pos K. M., Kern W. V. (2008). Site-directed mutagenesis reveals putative substrate binding residues in the Escherichia coli RND efflux pump AcrB. J. Bacteriol. 190 8225–8229 10.1128/jb.00912-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert J. A., Szymaniak-Vits M., Schuster S., Kern W. V. (2011). Efflux inhibition by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 2057–2060 10.1093/jac/dkr258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumann D., Valdivia R. H. (2007). Identification of host-induced pathogen genes by differential fluorescence induction reporter systems. Nat. Protoc. 2 770–777 10.1038/nprot.2007.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K., Courvalin P., Dantas G., Davies J., Eisenstein B., Huovinen P., et al. (2011). Tackling antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9 894–896 10.1038/nrmicro2693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. S., Cooper M. A. (2011). Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline in 2011. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 64 413–425 10.1038/ja.2011.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha H. J., Muller R. T., Pos K. M. (2014). Switch-loop flexibility affects transport of large drugs by the promiscuous AcrB multidrug efflux transporter. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 4767–4772 10.1128/aac.02733-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier J., Bredin J., Mahamoud A., Mallea M., Barbe J., Pages J. M. (2004). Inhibitors of antibiotic efflux in resistant Enterobacter aerogenes and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48 1043–1046 10.1128/AAC.48.3.1043-1046.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuanchuen R., Karkhoff-Schweizer R. R., Schweizer H. P. (2003). High-level triclosan resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is solely a result of efflux. Am. J. Infect. Control 31 124–127 10.1067/mic.2003.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmar J. A., Su C. C., Yu E. W. (2014). Bacterial multidrug efflux transporters. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 43 93–117 10.1146/annurev-biophys-051013-022855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du D., Venter H., Pos K. M., Luisi B. F. (2013). “The machinery and mechanism of multidrug efflux in gram-negative bacteria,” in Microbial Efflux Pumps: Current Research Chap. 3 eds Yu E. W., Zhang Q., Brown M. H. (Ames, IA: Caister Academic Press; ), 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Du D., Wang Z., James N. R., Voss J. E., Klimont E., Ohene-Agyei T., et al. (2014). Structure of the AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump. Nature 509 512–515 10.1038/nature13205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi G. R., Upadhyay H. C., Yadav D. K., Singh V., Srivastava S. K., Khan F., et al. (2014). 4-Hydroxy-alpha-tetralone and its derivative as drug resistance reversal agents in multi drug resistant Escherichia coli. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 83 482–492 10.1111/cbdd.12263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher T., Brandstatter L., Pos K. M. (2009). Structural and functional aspects of the multidrug efflux pump AcrB. Biol. Chem. 390 693–699 10.1515/bc.2009.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher T., Cha H. J., Seeger M. A., Brandstatter L., El-Delik J., Bohnert J. A., et al. (2012). Transport of drugs by the multidrug transporter AcrB involves an access and a deep binding pocket that are separated by a switch-loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 5687–5692 10.1073/pnas.1114944109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey M. I., Rahman M. M., Gibbons S., Piddock L. J. (2011). Medicinal plant extracts with efflux inhibitory activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 37 145–151 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisalberti D., Mahamoud A., Chevalier J., Baitiche M., Martino M., Pages J. M., et al. (2006). Chloroquinolines block antibiotic efflux pumps in antibiotic-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 27 565–569 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay T., Fraud S., Lau C. H., Gilmour C., Poole K. (2013). Antibiotic inducibility of the mexXY multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement of the MexZ anti-repressor ArmZ. PLoS ONE 8:e56858 10.1371/journal.pone.0056858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakata Y., Kondo A., Hoshino K., Yano H., Arai K., Hirotani A., et al. (2009). Efflux pump inhibitors reduce the invasiveness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34 343–346 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakata Y., Srikumar R., Poole K., Gotoh N., Suematsu T., Kohno S., et al. (2002). Multidrug efflux systems play an important role in the invasiveness of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Exp. Med. 196 109–118 10.1084/jem.20020005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs E. C., Yin X., Paul B. J., Astarita J. L., Storz G. (2012). Conserved small protein associates with the multidrug efflux pump AcrB and differentially affects antibiotic resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 16696–16701 10.1073/pnas.1210093109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidis A., Tsakris A., Kanellopoulou M., Maniatis A. N., Pournaras S. (2008). Effect of the proton motive force inhibitor carbonyl cyanide-m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 47 298–302 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern W. V., Steinke P., Schumacher A., Schuster S., von Baum H., Bohnert J. A. (2006). Effect of 1-(1-naphthylmethyl)-piperazine, a novel putative efflux pump inhibitor, on antimicrobial drug susceptibility in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57 339–343 10.1093/jac/dki445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy G., Tikhonova E. B., Zgurskaya H. I. (2008). Fitting periplasmic membrane fusion proteins to inner membrane transporters: mutations that enable Escherichia coli AcrA to function with Pseudomonas aeruginosa MexB. J. Bacteriol. 190 691–698 10.1128/JB.01276-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen J. E., Thomsen V. F., Martins A., Viveiros M., Amaral L. (2010). Non-antibiotics reverse resistance of bacteria to antibiotics. In Vivo 24 751–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurincic M., Klancnik A., Smole Mozina S. (2012). Effects of efflux pump inhibitors on erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline resistance in Campylobacter spp. isolates. Microb Drug Resist. 18 492–501 10.1089/mdr.2012.0017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau C. H., Krahn T., Gilmour C., Mullen E., Poole K. (2014). AmgRS-mediated envelope stress-inducible expression of the mexXY multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiologyopen 4 121–135 10.1002/mbo3.226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. H., Shafer W. M. (1999). The farAB-encoded efflux pump mediates resistance of gonococci to long-chained antibacterial fatty acids. Mol. Microbiol. 33 839–845 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. D., Galazzo J. L., Staley A. L., Lee J. C., Warren M. S., Fuernkranz H., et al. (2001). Microbial fermentation-derived inhibitors of efflux-pump-mediated drug resistance. Il Farmaco 56 81–85 10.1016/S0014-827X(01)01002-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennen R. M., Politz M. G., Kruziki M. A., Pfleger B. F. (2013). Identification of transport proteins involved in free fatty acid efflux in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 195 135–144 10.1128/jb.01477-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Yao Q., Pan X. C., Wang N., Zhang R., Li J., et al. (2011). Artesunate enhances the antibacterial effect of {beta}-lactam antibiotics against Escherichia coli by increasing antibiotic accumulation via inhibition of the multidrug efflux pump system AcrAB-TolC. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 769–777 10.1093/jac/dkr017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Cagliero C., Guo B., Barton Y. W., Maurel M. C., Payot S., et al. (2005). Bile salts modulate expression of the CmeABC multidrug efflux pump in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 187 7417–7424 10.1128/jb.187.21.7417-7424.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomovskaya O., Bostian K. A. (2006). Practical applications and feasibility of efflux pump inhibitors in the clinic–a vision for applied use. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71 910–918 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomovskaya O., Warren M. S., Lee A., Galazzo J., Fronko R., Lee M., et al. (2001). Identification and characterization of inhibitors of multidrug resistance efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: novel agents for combination therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45 105–116 10.1128/AAC.45.1.105-116.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomovskaya O., Zgurskaya H. I. (2011). Efflux Pumps from Gram-negative Bacteria: From Structure and Function to Inhibition. Norfolk, VA: Caister Academic press. [Google Scholar]

- Lomovskaya O., Zgurskaya H. I., Totrov M., Waitkins W. J. (2006). Waltzing transporters and ‘the dance macabre’ between humans and bacteria. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6 56–65 10.1038/nrd2200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzi V., Muselli A., Bernardini A. F., Berti L., Pages J. M., Amaral L., et al. (2009). Geraniol restores antibiotic activities against multidrug-resistant isolates from gram-negative species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53 2209–2211 10.1128/aac.00919-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahamoud A., Chevalier J., Baitiche M., Adam E., Pages J. M. (2011). An alkylaminoquinazoline restores antibiotic activity in Gram-negative resistant isolates. Microbiology 157(Pt. 2), 566–571 10.1099/mic.0.045716-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallea M., Mahamoud A., Chevalier J., Alibert-Franco S., Brouant P., Barbe J., et al. (2003). Alkylaminoquinolines inhibit the bacterial antibiotic efflux pump in multidrug-resistant clinical isolates. Biochem. J. 376(Pt. 3), 801–805 10.1042/bj20030963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez B. (2005). Bacterial efflux systems and efflux pumps inhibitors. Biochimie 87 1137–1147 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. L., Sanchez M. B., Martinez-Solano L., Hernandez A., Garmendia L., Fajardo A., et al. (2009). Functional role of bacterial multidrug efflux pumps in microbial natural ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33 430–449 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00157.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima T., Joshi S., Gomez-Escalada M., Schweizer H. P. (2007). Identification and characterization of TriABC-OpmH, a triclosan efflux pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requiring two membrane fusion proteins. J. Bacteriol. 189 7600–7609 10.1128/JB.00850-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra R., Bavro V. N. (2009). Assembly and transport mechanism of tripartite drug efflux systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1794 817–825 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S. (2008). Multidrug efflux transporter, AcrB–the pumping mechanism. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18 459–465 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S., Nakashima R., Yamashita E., Matsumoto T., Yamaguchi A. (2006). Crystal structures of a multidrug transporter reveal a functionally rotating mechanism. Nature 443 173–179 10.1038/nature05076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima R., Sakurai K., Yamasaki S., Hayashi K., Nagata C., Hoshino K., et al. (2013). Structural basis for the inhibition of bacterial multidrug exporters. Nature 500 102–106 10.1038/nature12300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima R., Sakurai K., Yamasaki S., Nishino K., Yamaguchi A. (2011). Structures of the multidrug exporter AcrB reveal a proximal multisite drug-binding pocket. Nature 480 565–569 10.1038/nature10641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi N., Prakash P., Gupta M. L., Mohapatra T. M. (2014). Possible role of curcumin as an efflux pump inhibitor in multi drug resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 8 Dc04–Dc07. 10.7860/jcdr/2014/8329.4965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H. (2011). Structure and mechanism of RND-type multidrug efflux pumps. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 77 1–60 10.1002/9780470920541.ch1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H., Pages J. M. (2012). Broad-specificity efflux pumps and their role in multidrug resistance of Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36 340–363 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00290.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H., Takatsuka Y. (2009). Mechanisms of RND multidrug efflux pumps. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1794 769–781 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohene-Agyei T., Lea J. D., Venter H. (2012). Mutations in MexB that affect the efflux of antibiotics with cytoplasmic targets. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 333 20–27 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02594.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohene-Agyei T., Mowla R., Rahman T., Venter H. (2014). Phytochemicals increase the antibacterial activity of antibiotics by acting on a drug efflux pump. Microbiologyopen 3 885–896 10.1002/mbo3.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman T. J., Kwasny S. M., Kim H. S., Nguyen S. T., Houseweart C., D’Souza S., et al. (2014). Characterization of a novel pyranopyridine inhibitor of the AcrAB efflux pump of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 722–733 10.1128/aac.01866-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orhan G., Bayram A., Zer Y., Balci I. (2005). Synergy tests by E test and checkerboard methods of antimicrobial combinations against Brucella melitensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 140–143 10.1128/jcm.43.1.140-143.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. L., Gnanakaran S. (2015). A data-driven approach to modeling the tripartite structure of multidrug resistance efflux pumps. Proteins 83 46–65 10.1002/prot.24632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piddock L. J. (2006a). Clinically relevant chromosomally encoded multidrug resistance efflux pumps in bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19 382–402 10.1128/cmr.19.2.382-402.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piddock L. J. (2006b). Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps? Not just for resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4 629–636 10.1038/nrmicro1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piddock L. J. (2014). Understanding the basis of antibiotic resistance: a platform for drug discovery. Microbiology 160 2366–2373 10.1099/mic.0.082412-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piddock L. J., Garvey M. I., Rahman M. M., Gibbons S. (2010). Natural and synthetic compounds such as trimethoprim behave as inhibitors of efflux in Gram-negative bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65 1215–1223 10.1093/jac/dkq079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. (2004). Efflux-mediated multiresistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10 12–26 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00763.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. (2005). Efflux-mediated antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56 20–51 10.1093/jac/dki171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K. (2011). Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to the max. Front. Microbiol. 2:65 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pos K. M. (2009). Drug transport mechanism of the AcrB efflux pump. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1794 782–793 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumbwe L., Wareham D., Aduse-Opoku J., Brazier J., Wexler H. (2007). Genetic analysis of mechanisms of multidrug resistance in a clinical isolate of Bacteroides fragilis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13 183–189 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purssell A., Poole K. (2013). Functional characterization of the NfxB repressor of the mexCD-oprJ multidrug efflux operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 159(Pt. 10), 2058–2073 10.1099/mic.0.069286-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos J. L., Duque E., Gallegos M.-T., Godoy P., Ramos-González M. I., Rojas A., et al. (2002). Mechanisms of solvent tolerance in gram-negative bacteria. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 56 743–768 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.161038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci V., Busby S. J., Piddock L. J. (2012). Regulation of RamA by RamR in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium: isolation of a RamR superrepressor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56 6037–6040 10.1128/aac.01320-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci V., Tzakas P., Buckley A., Piddock L. J. (2006). Ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains are difficult to select in the absence of AcrB and TolC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50 38–42 10.1128/aac.50.1.38-42.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice A., Liu Y., Michaelis M. L., Himes R. H., Georg G. I., Audus K. L. (2005). Chemical modification of paclitaxel (Taxol) reduces P-glycoprotein interactions and increases permeation across the blood-brain barrier in vitro and in situ. J. Med. Chem. 48 832–838 10.1021/jm040114b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg E. Y., Bertenthal D., Nilles M. L., Bertrand K. P., Nikaido H. (2003). Bile salts and fatty acids induce the expression of Escherichia coli AcrAB multidrug efflux pump through their interaction with Rob regulatory protein. Mol. Microbiol. 48 1609–1619 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth B. L., Poot M., Yue S. T., Millard P. J. (1997). Bacterial viability and antibiotic susceptibility testing with SYTOX green nucleic acid stain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63 2421–2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggerone P., Murakami S., Pos K. M., Vargiu A. V. (2013a). RND efflux pumps: structural information translated into function and inhibition mechanisms. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 13 3079–3100 10.2174/15680266113136660220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggerone P., Vargiu A. V., Collu F., Fischer N., Kandt C. (2013b). Molecular dynamics computer simulations of multidrug RND efflux pumps. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 5:e201302008 10.5936/csbj.201302008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez P., Moreno E., Martinez J. L. (2005). The biocide triclosan selects Stenotrophomonas maltophilia mutants that overproduce the SmeDEF multidrug efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 781–782 10.1128/AAC.49.2.781-782.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M. A., Diederichs K., Eicher T., Brandstatter L., Schiefner A., Verrey F., et al. (2008a). The AcrB efflux pump: conformational cycling and peristalsis lead to multidrug resistance. Curr. Drug Targets 9 729–749 10.2174/138945008785747789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M. A., von Ballmoos C., Eicher T., Brandstatter L., Verrey F., Diederichs K., et al. (2008b). Engineered disulfide bonds support the functional rotation mechanism of multidrug efflux pump AcrB. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15 199–205 10.1038/nsmb.1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M. A., Schiefner A., Eicher T., Verrey F., Diederichs K., Pos K. M. (2006). Structural asymmetry of AcrB trimer suggests a peristaltic pump mechanism. Science 313 1295–1298 10.1126/science.1131542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura A., Molina L., Fillet S., Krell T., Bernal P., Muñoz-Rojas J., et al. (2012). Solvent tolerance in gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 23 415–421 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver S., Phung L. T. (1996). Bacterial heavy metal resistance: new surprises. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 50 753–789 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr L. M., Fruci M., Poole K. (2012). Pentachlorophenol induction of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa mexAB-oprM efflux operon: involvement of repressors NalC and MexR and the antirepressor ArmR. PLoS ONE 7:e32684 10.1371/journal.pone.0032684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegos G., Stermitz F. R., Lomovskaya O., Lewis K. (2002). Multidrug pump inhibitors uncover remarkable activity of plant antimicrobials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46 3133–3141 10.1128/AAC.46.10.3133-3141.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonova E. B., Yamada Y., Zgurskaya H. I. (2011). Sequential mechanism of assembly of multidrug efflux pump AcrAB-TolC. Chem. Biol. 18 454–463 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargiu A. V., Ruggerone P., Opperman T. J., Nguyen S. T., Nikaido H. (2014). Molecular mechanism of MBX2319 inhibition of Escherichia coli AcrB multidrug efflux pump and Comparison with other inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 6224–6234 10.1128/aac.03283-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter H., Shilling R. A., Velamakanni S., Balakrishnan L., Van Veen H. W. (2003). An ABC transporter with a secondary-active multidrug translocator domain. Nature 426 866–870 10.1038/nature02173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley A. R., Rosen B. P. (2009). Transport Mechanisms of Resistance to Drugs and Toxic Metals Antimicrobial Drug Resistance. Berlin: Springer, 111–120 10.1007/978-1-59745-180-2_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wehmeier C., Schuster S., Fahnrich E., Kern W. V., Bohnert J. A. (2009). Site-directed mutagenesis reveals amino acid residues in the Escherichia coli RND efflux pump AcrB that confer macrolide resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53 329–330 10.1128/aac.00921-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch A., Awah C. U., Jing S., van Veen H. W., Venter H. (2010). Promiscuous partnering and independent activity of MexB, the multidrug transporter protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem. J. 430 355–364 10.1042/BJ20091860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White D. G., Goldman J. D., Demple B., Levy S. B. (1997). Role of the acrAB locus in organic solvent tolerance mediated by expression of marA, soxS, or robA in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179 6122–6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2014). Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance 2014. Available at: www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Wilke M. S., Heller M., Creagh A. L., Haynes C. A., McIntosh L. P., Poole K., et al. (2008). The crystal structure of MexR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in complex with its antirepressor ArmR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 14832–14837 10.1073/pnas.0805489105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K., Ma J., Rothnie A., Biggin P. C., Kerr I. D. (2014). Towards understanding promiscuity in multidrug efflux pumps. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39 8–16 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz S., Altinkanat-Gelmez G., Bolelli K., Guneser-Merdan D., Over-Hasdemir M. U., Yildiz I., et al. (2014). Pharmacophore generation of 2-substituted benzothiazoles as AdeABC efflux pump inhibitors in A. baumannii. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 25 551–563 10.1080/1062936x.2014.919357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng B., Wang H., Zou L., Zhang A., Yang X., Guan Z. (2010). Evaluation and target validation of indole derivatives as inhibitors of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 74 2237–2241 10.1271/bbb.100433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Lambert G., Liao D., Kim H., Robin K., Tung C. K., et al. (2011). Acceleration of emergence of bacterial antibiotic resistance in connected microenvironments. Science 333 1764–1767 10.1126/science.1208747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zgurskaya H. I., Krishnamoorthy G., Ntreh A., Lu S. (2011). Mechanism and function of the outer membrane channel tolc in multidrug resistance and physiology of enterobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2:189 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]