Abstract

Objective

Axitinib is a potent and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1–3. This analysis compared efficacy and safety of axitinib plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer from Japan, North America and the European Union, enrolled in a randomized Phase III study.

Methods

Patients (n = 632), stratified by disease extent, were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive axitinib/gemcitabine or placebo/gemcitabine. Axitinib was administered at a starting dose of 5 mg orally twice daily and gemcitabine at 1000 mg/m2 once weekly for 3 weeks in 4 week cycles. Primary endpoint was overall survival.

Results

Among Japanese patients, median overall survival was not estimable (95% confidence interval, 7.4 months—not estimable) with axitinib/gemcitabine (n = 58) and 9.9 months (95% confidence interval, 7.4–10.5) with placebo/gemcitabine (n = 56) (hazard ratio 1.093 [95% confidence interval, 0.525–2.274]). Median survival follow-up (range) was 5.1 months (0.02–12.3) with axitinib/gemcitabine vs. 5.4 months (1.8–10.5) with placebo/gemcitabine. Similarly, no difference was detected in overall survival between axitinib/gemcitabine and placebo/gemcitabine in patients from North America or the European Union. Common adverse events with axitinib/gemcitabine in Japanese patients were fatigue, anorexia, dysphonia, nausea and decreased platelet count. Axitinib safety profile was generally similar in patients from the three regions, although there were differences in incidence of some adverse events. An exploratory analysis did not show any correlation between axitinib/gemcitabine-related hypertension and overall survival.

Conclusions

Axitinib/gemcitabine, while tolerated, did not provide survival benefit over gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer from Japan or other regions.

Keywords: axitinib, gemcitabine, Japanese, pancreatic cancer

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer was diagnosed in an estimated 337 872 patients and claimed ∼330 372 deaths worldwide in 2012 (1). The estimated incidences and deaths, respectively, were 42 885 and 41 509 in the USA, 79 331 and 78 651 in the European Union and 32 899 and 31 046 in Japan (1). Currently, surgical resection is the only potentially curative treatment of pancreatic cancer, but patients are often diagnosed with advanced unresectable disease (2). For advanced pancreatic cancer, combination chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX (5-fluorouracil/leucovorin, oxaliplatin and irinotecan) or gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel or erlotinib (an inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor), as well as gemcitabine monotherapy, are recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2). Pancreatic cancer is associated with the poorest 5-year survival rate (6%) of any cancer in the USA (3). Therefore, new treatment options are urgently needed to improve survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is highly expressed in pancreatic cancer, with the level of expression correlated with microvascular density (4–6) and possibly with poor prognosis (5,6). Axitinib is a potent and selective inhibitor of VEGF receptors 1, 2 and 3 (7), approved for second-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Based on promising activity against advanced pancreatic cancer reported in an open-label randomized Phase II study (8), a randomized Phase III study was conducted globally to evaluate the efficacy and safety of axitinib in combination with gemcitabine (9). At the pre-planned interim analysis, median overall survival (OS), the primary endpoint of the study, was 8.5 months in the axitinib/gemcitabine arm (n = 314) compared with 8.3 months in the placebo/gemcitabine arm (n = 316) (hazard ratio [HR] 1.014; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.786–1.309; P = 0.5436, stratified one-sided log-rank test), and the independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) concluded that the futility boundary had been crossed (9). Thus, the study failed to demonstrate survival benefit of adding axitinib to gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer in the overall population.

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report describing potential geographic differences in efficacy and safety outcomes in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with anticancer drugs, including antiangiogenic agents. Therefore, we have undertaken in-depth analyses of the data from this Phase III study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of axitinib/gemcitabine in Japanese patients and compare the results with those from North America and the European Union in order to assess potential geographic differences in patient outcomes. In addition, based on a post hoc exploratory analysis of data from the Phase II study of axitinib/gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer, which indicated a longer median OS in patients who experienced diastolic blood pressure (BP) ≥90 mm Hg during treatment compared with those who did not (8), the exploratory analysis was expanded using the data from this Phase III study to further assess potential correlations between the axitinib efficacy outcome and hypertension in these patients.

Methods

Study design

This was a randomized, double-blind Phase III study conducted in 24 countries, including Japan. The details of the study design and treatment have been published previously (9). In brief, eligible patients were stratified by extent of the disease (metastatic vs. locally advanced pancreatic cancer), and randomly assigned (1:1) to receive axitinib/gemcitabine or placebo/gemcitabine. The primary endpoint was OS; secondary endpoints included progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR) and safety. For Japanese patients enrolled in the study, an additional review of the first 16 patients was conducted by the DMC to evaluate the safety of axitinib/gemcitabine, and subsequent enrollment and initiation of treatment was based on the feedback from the DMC.

The study protocol, amendments and informed consent documentation were reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards and independent ethics committees at each center. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines as well as applicable local regulatory requirements. All patients provided written informed consent prior to study entry. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT00471146).

Patients

As previously described in detail (9), eligible patients were aged 18 years or older (≥20 years old in Japan) with histologically or cytologically confirmed metastatic or locally advanced unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0 or 1; adequate bone marrow, hepatic, renal and coagulation function; and without uncontrolled hypertension, i.e. baseline BP readings must be ≤140/90 mm Hg. Use of antihypertensive medications was permitted. Exclusion criteria included prior systemic chemotherapy; prior therapy with gemcitabine, axitinib or VEGF inhibitors; or active seizure or brain metastasis.

Study treatment

Patients received gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) as a 30 min intravenous infusion once weekly for 3 weeks followed by 1 week off. Gemcitabine dose could be reduced to 750, 550 or 425 mg/m2 to manage toxicities. Axitinib or placebo was administered at a starting dose of 5 mg twice daily (BID) orally with food. Axitinib or placebo dose could be increased stepwise to 7 mg BID, and then to the maximum 10 mg BID, in patients who had no drug-related, Grade ≥3 adverse event (AE) per Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0 for consecutive 2-week periods, and had BP ≤150/90 mm Hg without any antihypertensive medication. Axitinib or placebo dose could be reduced to 3 mg BID, and then to 2 mg BID, if necessary, to manage treatment-related toxicity. Patients were treated in 4-week cycles until disease progression, unmanageable AEs or withdrawal of consent.

Assessments

As reported previously (9), tumor assessments were conducted at screening and repeated every 8 weeks until 28 days after the last dose and whenever disease progression was suspected. Tumor response was assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.0. Safety was monitored throughout the study and AEs were graded per CTCAE version 3.0. BP was measured in-clinic at screening and once every week. In addition, all patients were provided with a BP-monitoring device and instructed to measure BP twice daily at home and to contact their physician if BP was >150/100 mm Hg or symptoms related to elevated BP developed. Plasma level of thyroid-stimulating hormone and free thyroxine was monitored during treatment period, and hypothyroidism was treated with standard medication. Urinalysis was performed at screening and once every cycle.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were previously described in detail (9). For time-to-event endpoints (OS, PFS), median and two-sided 95% CIs were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method in the two treatment arms in each region (Japan, North America and the European Union). The OS and PFS between the two treatment arms within each region were compared using a log-rank test (one-sided), stratified by extent of the disease. The ORR and corresponding exact two-sided 95% CI were summarized in the two treatment arms in each region, and Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test (two-sided), stratified by the stratification factor, was used for comparison between the two treatment arms. To explore potential correlation between OS and hypertension, univariate Cox proportional regression was performed using maximum diastolic BP during Cycle 1 as a categorical variable. Patients were divided into two groups; one group with patients who experienced maximum diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg during Cycle 1 and the other group with patients who did not.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

Of 632 randomized patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (n = 316 in each arm), two patients in the axitinib/gemcitabine arm did not have randomization information in the clinical database at the time of the analysis, and were excluded from the analyses. Randomized patients were from Japan (n = 114), North America (n = 158), the European Union (n = 264), Asia other than Japan (n = 55) and other countries/regions (Argentina, Australia and South Africa; n = 39). By country, Japan had the second highest number of patients closely following the USA (n = 119). Due to small number of patients, Asia other than Japan, Argentina, Australia and South Africa were not included in the current analysis.

Median age and the proportion of male and female patients were comparable among Japanese, North American and European Union patients (Table 1). However, a higher percentage of Japanese patients had ECOG PS 0 and locally advanced disease compared with those in the other two regions.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

| Overall study population |

Japan |

North America |

European Union |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axitinib/Gem (n = 314) | Placebo/Gem (n = 316) | Axitinib/Gem (n = 58) | Placebo/Gem (n = 56) | Axitinib/Gem (n = 77) | Placebo/Gem (n = 81) | Axitinib/Gem (n = 132) | Placebo/Gem (n = 132) | |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| Median | 61 | 62 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 65 | 60 | 62 |

| Range | 34–84 | 35–89 | 43–77 | 39–77 | 39–84 | 37–89 | 34–82 | 35–81 |

| Sex, % | ||||||||

| Male | 60.8 | 59.5 | 69.0 | 62.5 | 54.5 | 60.5 | 55.3 | 56.1 |

| Female | 39.2 | 40.5 | 31.0 | 37.5 | 45.5 | 39.5 | 44.7 | 43.9 |

| Race, % | ||||||||

| White | 67.2 | 69.6 | 0 | 0 | 85.7 | 91.4 | 97.7 | 97.0 |

| Black | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 9.1 | 6.2 | 0 | 0.8 |

| Asian | 28.3 | 26.6 | 100 | 100 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.8 | 0 |

| Other | 1.9 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| ECOG PSa, % | ||||||||

| 0 | 46.8 | 50.0 | 77.6 | 76.8 | 37.7 | 38.3 | 44.7 | 50.8 |

| 1 | 51.6 | 48.7 | 22.4 | 23.2 | 62.3 | 61.7 | 51.5 | 47.7 |

| Disease stageb, % | ||||||||

| Locally advanced | 24.2 | 23.7 | 31.0 | 33.9 | 19.5 | 19.8 | 25.0 | 25.0 |

| Metastatic | 75.8 | 76.3 | 69.0 | 66.1 | 80.5 | 80.2 | 75.0 | 75.0 |

| Prior surgerya,c, % | ||||||||

| Yes | 11.8 | 10.8 | 3.4 | 10.7 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 17.4 | 14.4 |

| No | 86.3 | 86.4 | 93.1 | 76.8 | 93.5 | 93.8 | 80.3 | 84.8 |

| Prior adjuvant therapy, % | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.8 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 5.4 | 0 | 2.5 | 5.3 | 3.8 |

| No | 96.2 | 96.5 | 98.3 | 94.6 | 100 | 97.5 | 94.7 | 96.2 |

| Prior radiotherapya, % | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.2 | 4.1 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 7.4 | 3.0 | 5.3 |

| No | 95.5 | 94.3 | 98.3 | 98.2 | 97.4 | 92.6 | 95.5 | 91.7 |

Gem, gemcitabine; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

aThe remaining percent due to missing and/or unknown.

bAt randomization.

cResected or partially resected.

Treatments and patient disposition

The exposure to study drugs in each region as well as in the overall population is summarized in Table 2. Median treatment duration for gemcitabine in the axitinib/gemcitabine- and placebo/gemcitabine-treated patients was generally similar between Japan and the European Union. In North America, however, patients in the axitinib/gemcitabine arm received fewer days of gemcitabine treatment compared with those in the placebo/gemcitabine arm (43 vs. 71 days, respectively), and had more gemcitabine dose interruptions (72.0 vs. 54.3%, respectively). For axitinib treatment, median duration was longest for patients in Japan, followed by those in the European Union and then North America (95 vs. 84 vs. 63 days, respectively). However, axitinib dose interruptions and dose reductions, respectively, were more frequent among Japanese patients (87.7 and 31.6%) compared with those in North America (78.7 and 16.0%) or the European Union (64.6 and 26.0%).

Table 2.

Exposure to study drugsa

| Overall study population |

Japan |

North America |

European Union |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | |

| Gemcitabine | n = 305 | n = 308 | n = 57 | n = 56 | n = 75 | n = 81 | n = 127 | n = 126 |

| No. cycles startedb,c | ||||||||

| Median | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Range | 1–13 | 1–12 | 1–10 | 1–10 | 1–9 | 1–12 | 1–13 | 1–10 |

| Days on treatmentc,d | ||||||||

| Median | 71 | 73 | 119 | 99 | 43 | 71 | 71 | 85 |

| Range | 1–336 | 1–358 | 1–267 | 1–267 | 1–232 | 1–334 | 1–336 | 1–358 |

| Dose interruption, n (%) | 194 (63.6) | 165 (53.6) | 33 (57.9) | 29 (51.8) | 54 (72.0) | 44 (54.3) | 73 (57.5) | 62 (49.2) |

| Dose reduction, n (%) | 125 (41.0) | 100 (32.5) | 37 (64.9) | 27 (48.2) | 23 (30.7) | 26 (32.1) | 42 (33.1) | 34 (27.0) |

| Relative dose intensityc,e, % | ||||||||

| Median | 77.4 | 79.4 | 70.1 | 72.8 | 70.8 | 78.8 | 81.7 | 83.0 |

| Range | 27.7–106.4 | 19.6–106.3 | 32.1–104.5 | 33.3–101.3 | 27.7–101.4 | 19.6–104.5 | 32.5–106.4 | 32.7–106.3 |

| Axitinib or placebo | n = 298 | n = 301 | n = 57 | n = 56 | n = 75 | n = 81 | n = 127 | n = 126 |

| Days on treatmentd,f | ||||||||

| Median | 84 | 85 | 95 | 88 | 63 | 84 | 84 | 111 |

| Range | 1–335 | 2–361 | 24–280 | 5–280 | 2–251 | 2–361 | 1–335 | 4–281 |

| Days on drugf,g | ||||||||

| Median | 84 | 84 | 91 | 88 | 59.5 | 84 | 84 | 91 |

| Range | 1–336 | 2–334 | 24–280 | 5–280 | 2–251 | 2–334 | 1–336 | 4–288 |

| Dose interruption, n (%) | 223 (74.8) | 183 (60.8) | 50 (87.7) | 36 (64.3) | 59 (78.7) | 60 (74.1) | 82 (64.6) | 61 (48.4) |

| Dose reduction, n (%) | 74 (24.8) | 30 (10.0) | 18 (31.6) | 4 (7.1) | 12 (16.0) | 8 (9.9) | 33 (26.0) | 12 (9.5) |

| Dose increase, n (%) | 95 (31.9) | 131 (43.5) | 7 (12.3) | 32 (57.1) | 16 (21.3) | 29 (35.8) | 51 (40.2) | 57 (45.2) |

| Relative dose intensitye,f, % | ||||||||

| Median | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 117.1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Range | 36.3–186.7 | 50.0–190.2 | 40.0–184.4 | 55.6–190.2 | 48.2–179.6 | 54.4–168.0 | 38.4–186.7 | 62.6–188.1 |

Gem, gemcitabine

aBased on patients who received study treatment.

bIf patients took at least some gemcitabine, they were considered to have started a cycle.

cn = 304 and 302 for Axitinib/Gem and Placebo/Gem, respectively, in the overall study population; n = 74 and 79 for Axitinib/Gem and Placebo/Gem, respectively, in North America; and n = 123 for Placebo/Gem in the European Union.

dTime period starting from date of the first dose to date of the last dose or data cutoff.

e(Actual total dose/intended total dose) × 100.

fn = 55 and 53 for Axitinib/Gem and Placebo/Gem, respectively, in Japan; n = 72 and 79 for Axitinib/Gem and Placebo/Gem, respectively, in North America; and n = 125 and 124 for Axitinib/Gem and Placebo/Gem, respectively, in the European Union.

gTotal number of days on which axitinib or placebo was actually administered.

At the time of final analysis (data cutoff date: 23 January 2009), 24 and 27% of Japanese patients in the axitinib/gemcitabine and placebo/gemcitabine arms, respectively, discontinued study treatment, whereas a higher percentage of patients in North America (74 and 67%) and in the European Union (50 and 56%) discontinued treatment. The main reason for discontinuation in each arm was disease progression.

The most common systemic treatment administered to Japanese patients following the study treatment was S-1, whereas gemcitabine, 5-FU and oxaliplatin were the common follow-up treatments received by patients in North America and the European Union (Supplementary Material 1).

Efficacy

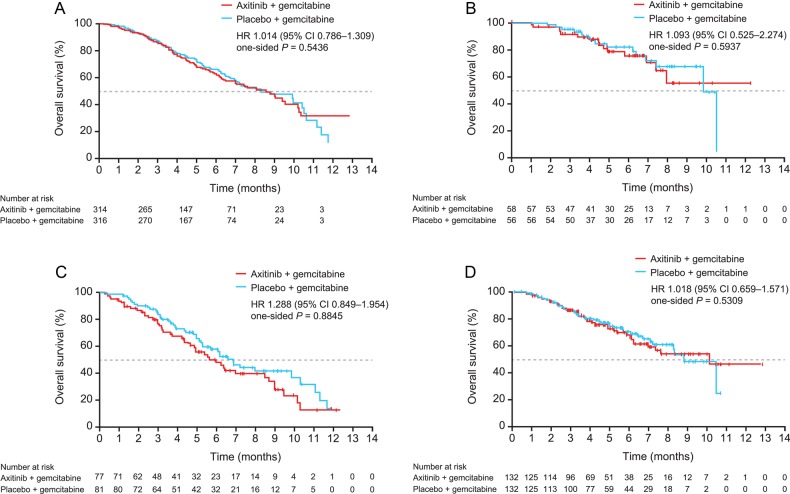

The OS in the overall study population and individual region by study treatment arm is presented in Table 3. In the overall study population, there was no statistically significant difference in OS between the axitinib/gemcitabine and placebo/gemcitabine arms (HR 1.014; P = 0.5436; Fig. 1A), as previously reported (9).

Table 3.

Summary of overall survival in the overall study population and by disease extent and region

| Overall study population |

Japan |

North America |

European Union |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | |

| Overall | ||||||||

| No. of patients | 314 | 316 | 58 | 56 | 77 | 81 | 132 | 132 |

| No. of events (%) | 118 (37.6) | 120 (38.0) | 15 (25.9) | 15 (26.8) | 45 (58.4) | 44 (54.3) | 41 (31.1) | 41 (31.1) |

| Follow-up period | ||||||||

| Median, months | 4.4 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 4.7 |

| (range) | (0.02–12.8) | (0.02–11.9) | (0.02–12.3) | (1.8–10.5) | (0.2–12.1) | (0.4–11.9) | (0.02–12.8) | (0.02–10.6) |

| Median OS, months | 8.5 | 8.3 | NE | 9.9 | 5.6 | 6.6 | 10.1 | 8.7 |

| (95% CI) | (6.9–9.5) | (6.9–10.3) | (7.4–NE) | (7.4–10.5) | (4.6–8.5) | (5.3–10.3) | (6.9–NE) | (7.1–NE) |

| Hazard ratioa,b (95% CI) | 1.014 (0.786–1.309) | 1.093 (0.525–2.274) | 1.288 (0.849–1.954) | 1.018 (0.659–1.571) | ||||

| P valuec | 0.5436 | 0.5937 | 0.8845 | 0.5309 | ||||

| Locally advanced disease | ||||||||

| No. of patients | 76 | 75 | 18 | 19 | 15 | 16 | 33 | 33 |

| No. of events (%) | 21 (27.6) | 13 (17.3) | 3 (16.7) | 3 (15.8) | 8 (53.3) | 5 (31.3) | 7 (21.2) | 4 (12.1) |

| Follow-up period | ||||||||

| Median, months | 5.1 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 3.0 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 6.0 |

| (range) | (0.02–10.6) | (0.4–11.9) | (0.02–10.3) | (2.9–10.5) | (1.3–10.0) | (1.4–11.9) | (0.02–10.6) | (0.4–10.6) |

| Median OS, months | 9.5 | 10.6 | NE | 9.9 | 6.3 | NE | 10.1 | 10.4 |

| (95% CI) | (7.4–NE) | (9.9–NE) | (8.0–NE) | (9.9–10.5) | (3.0–9.5) | (5.0–NE) | (7.3–NE) | (10.4–NE) |

| Hazard ratioa (95% CI) | 2.079 (1.031–4.189) | 1.939 (0.319–11.787) | 2.273 (0.741–6.974) | 2.351 (0.684–8.086) | ||||

| P valued | 0.9818 | 0.7678 | 0.9330 | 0.9187 | ||||

| Metastatic disease | ||||||||

| No. of patients | 238 | 241 | 40 | 37 | 62 | 65 | 99 | 99 |

| No. of events (%) | 97 (40.8) | 107 (44.4) | 12 (30.0) | 12 (32.4) | 37 (59.7) | 39 (60.0) | 34 (34.3) | 37 (37.4) |

| Follow-up period | ||||||||

| Median, months | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 4.3 |

| (range) | (0.2–12.8) | (0.02–11.7) | (1.1–12.3) | (1.8–10.4) | (0.2–12.1) | (0.4–11.7) | (0.5–12.8) | (0.02–9.8) |

| Median OS, months | 7.0 | 6.9 | NE | NE | 5.5 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 8.2 |

| (95% CI) | (5.8–9.3) | (6.2–8.0) | (6.9–NE) | (6.4–NE) | (4.3–8.5) | (5.2–8.0) | (6.1–NE) | (6.4–NE) |

| Hazard ratioa (95% CI) | 0.904 (0.686–1.190) | 0.972 (0.435–2.170) | 1.170 (0.746–1.837) | 0.897 (0.563–1.430) | ||||

| P valued | 0.2345 | 0.4721 | 0.2456 | 0.3230 | ||||

Gem, gemcitabine; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; NE, not estimable.

aAxitinib/gemcitabine vs. placebo/gemcitabine; assuming proportional hazards model, a hazard ratio <1 indicates a reduction in hazard rate in favor of axitinib/gemcitabine and a hazard ratio >1 indicates a reduction in favor of placebo/gemcitabine.

bHazard ratio stratified by extent of the disease (locally advanced vs. metastatic pancreatic cancer).

cFrom a one-sided log-rank test of treatment stratified by extent of the disease (locally advanced vs. metastatic pancreatic cancer).

dFrom a one-sided, unstratified log-rank test.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates for overall survival for axitinib/gemcitabine vs. placebo/gemcitabine in the overall study population (A), and in patients in Japan (B), North America (C) and the European Union (D). Panel A reprinted from The Lancet Oncology, 12 (3), Kindler HL, et al. (9). Axitinib plus gemcitabine versus placebo plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a double-blind randomised Phase 3 study, 256–62, Copyright 2011, with permission from Elsevier.

Since the study was terminated, which was recommended by the independent DMC due to the futility at the interim analysis, median survival follow-up period among all Japanese patients was short as well as those in other regions. The HR for OS between the axitinib/gemcitabine vs. placebo/gemcitabine arms in all Japanese patients was 1.093 (95% CI, 0.525–2.274; P = 0.5937; Fig. 1B). In Japanese patients with locally advanced disease, HR for OS was 1.939 (95% CI, 0.319–11.787; P = 0.7678), whereas in those with metastatic disease, it was 0.972 (95% CI, 0.435–2.170; P = 0.4721) (Table 3). Similarly, median OS did not differ between the two treatment arms in patients from North America or the European Union (Fig. 1C and D).

The PFS in each treatment arm is summarized in Table 4. In the overall study population, PFS was also similar between the axitinib/gemcitabine and placebo/gemcitabine arms (HR 1.006; 95% CI, 0.779–1.298; P = 0.5203; Supplementary Material 2A) (9). Among all Japanese patients, there was no difference in median PFS between the two treatment arms (HR 0.905; 95% CI, 0.416–1.968; P = 0.5995; Supplementary Material 2B). There was no difference in PFS between the two treatment arms in patients from North America or the European Union as well (Supplementary Material 2C and D).

Table 4.

Summary of progression-free survival in the overall study population and by disease extent and region

| Overall study population |

Japan |

North America |

European Union |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | Axitinib/Gem | Placebo/Gem | |

| Overall | ||||||||

| No. of patients | 314 | 316 | 58 | 56 | 77 | 81 | 132 | 132 |

| No. of events (%) | 116 (36.9) | 125 (39.6) | 12 (20.7) | 16 (28.6) | 39 (50.6) | 38 (46.9) | 44 (33.3) | 47 (35.6) |

| Median, months | 4.4 | 4.4 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 4.9 |

| (95% CI) | (4.0–5.6) | (3.7–5.2) | (4.8–7.2) | (4.0–10.5) | (2.9–5.3) | (3.4–5.7) | (3.7–7.5) | (3.8–7.0) |

| Hazard ratioa,b (95% CI) | 1.006 (0.779–1.298) | 0.905 (0.416–1.968) | 1.290 (0.814–2.045) | 0.908 (0.594–1.390) | ||||

| P valuec | 0.5203 | 0.5995 | 0.8635 | 0.6707 | ||||

| Locally advanced disease | ||||||||

| No. of patients | 76 | 75 | 18 | 19 | 15 | 16 | 33 | 33 |

| No. of events (%) | 22 (28.9) | 17 (22.7) | 4 (22.2) | 2 (10.5) | 7 (46.7) | 4 (25.0) | 7 (21.2) | 9 (27.3) |

| Median, months | 5.9 | 9.1 | 5.8 | 10.5 | 7.2 | 9.0 | 7.3 | 10.4 |

| (95% CI) | (4.2–7.3) | (5.8–10.6) | (5.6–NE) | (5.8–10.5) | (1.7–9.5) | (2.0–9.0) | (4.2–9.5) | (4.1–10.4) |

| Hazard ratioa (95% CI) | 1.888 (0.978–3.645) | 4.775 (0.531–42.915) | 1.477 (0.413–5.287) | 1.384 (0.500–3.832) | ||||

| P valued | 0.9732 | 0.9382 | 0.7273 | 0.7379 | ||||

| Metastatic disease | ||||||||

| No. of patients | 238 | 241 | 40 | 37 | 62 | 65 | 99 | 99 |

| No. of events (%) | 94 (39.5) | 108 (44.8) | 8 (20.0) | 14 (37.8) | 32 (51.6) | 34 (52.3) | 37 (37.4) | 38 (38.4) |

| Median, months | 4.2 | 3.8 | 7.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 4.1 |

| (95% CI) | (3.7–5.4) | (3.6–4.5) | (4.8–7.2) | (3.5–7.4) | (2.4–5.3) | (3.2–5.4) | (3.5–7.5) | (3.5–5.9) |

| Hazard ratioa (95% CI) | 0.897 (0.679–1.184) | 0.629 (0.259–1.527) | 1.264 (0.770–2.073) | 0.834 (0.523–1.329) | ||||

| P valued | 0.2214 | 0.1506 | 0.1718 | 0.2206 | ||||

Gem, gemcitabine; CI, confidence interval; NE, not estimable

aAxitinib/gemcitabine vs. placebo/gemcitabine; assuming proportional hazards model, a hazard ratio <1 indicates a reduction in hazard rate in favor of axitinib/gemcitabine and a hazard ratio >1 indicates a reduction in favor of placebo/gemcitabine.

bHazard ratio stratified by extent of the disease (locally advanced vs. metastatic pancreatic cancer).

cFrom a one-sided log-rank test of treatment stratified by extent of the disease (locally advanced vs. metastatic pancreatic cancer).

dFrom a one-sided, unstratified log-rank test.

The ORR in the overall population was numerically higher with axitinib/gemcitabine than placebo/gemcitabine (4.9 vs. 1.6%, respectively; P = 0.038). The ORR for the axitinib/gemcitabine and placebo/gemcitabine arms, respectively, was 6.7% (95% CI, 0.8–22.1) and 0% (95% CI, 0–9.7) (P = 0.145) in Japanese patients, 3.1% (95% CI, 0.4–10.8) and 2.6% (95% CI, 0.3–9.2) (P = 0.885) in patients in North America, and 4.6% (95% CI, 1.5–10.5) and 1.0% (95% CI, 0–5.3) (P = 0.117) in patients in the European Union.

Safety

All-causality AEs reported by >20% of patients in each arm in the overall study population and in individual regions are summarized in Table 5. Among Japanese patients, fatigue, anorexia, dysphonia, nausea and decreased platelet count were common AEs in patients treated with axitinib/gemcitabine, whereas anorexia and decreased neutrophil count were common with placebo/gemcitabine treatment. Grade ≥3 AEs reported by ≥10% of Japanese patients included decreased neutrophil count, anorexia, decreased platelet count and hypertension with axitinib/gemcitabine, decreased neutrophil count and decreased platelet count with placebo/gemcitabine. The profile of common AEs was generally similar between Japanese patients and the overall study population, North American or the European Union patients, although there were some differences in incidence rates for some AEs.

Table 5.

Treatment-emergent, all-causality adverse events reported by >20% of patients in any arm in any region

| All grades/≥3 Grade, % | Overall study population |

Japan |

North America |

European Union |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axitinib/ Gem (n = 305) | Placebo/ Gem (n = 308) | Axitinib/ Gem (n = 57) | Placebo/ Gem (n = 56) | Axitinib/ Gem (n = 75) | Placebo/ Gem (n = 81) | Axitinib/ Gem (n = 127) | Placebo/ Gem (n = 126) | |

| Non-hematologic adverse events | ||||||||

| Nausea | 47/4 | 37/3 | 58/2 | 46/5 | 45/8 | 36/2 | 41/4 | 37/1 |

| Fatigue | 42/9 | 37/7 | 70/9 | 46/9 | 49/13 | 53/11 | 26/6 | 25/5 |

| Anorexia | 37/6 | 27/4 | 68/16 | 52/4 | 33/5 | 21/5 | 24/4 | 22/3 |

| Diarrhea | 33/1 | 22/2 | 39/2 | 16/0 | 27/1 | 26/1 | 29/0 | 25/2 |

| Vomiting | 32/4 | 33/3 | 39/0 | 34/0 | 28/5 | 40/4 | 33/6 | 32/4 |

| Constipation | 29/1 | 31/2 | 49/0 | 41/4 | 24/3 | 38/4 | 21/0 | 22/1 |

| Hypertension | 28/7 | 9/2 | 44/12 | 4/2 | 31/7 | 14/5 | 23/5 | 10/0 |

| Dysphonia | 22/<1 | 4/0 | 60/2 | 18/0 | 17/0 | 2/0 | 10/0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 21/7 | 19/6 | 7/2 | 4/0 | 24/9 | 25/10 | 24/8 | 22/5 |

| Stomatitis | 17/0 | 4/<1 | 46/0 | 2/0 | 12/0 | 2/1 | 8/0 | 6/0 |

| Pyrexia | 16/1 | 16/<1 | 23/0 | 20/0 | 12/1 | 23/0 | 18/2 | 11/1 |

| Rash | 14/1 | 14/1 | 21/0 | 32/2 | 8/1 | 16/1 | 13/1 | 7/1 |

| Asthenia | 14/5 | 13/2 | 0 | 0 | 12/11 | 12/2 | 23/6 | 21/3 |

| Weight decreased | 14/<1 | 10/<1 | 21/0 | 11/2 | 9/0 | 16/0 | 14/1 | 10/0 |

| Alopecia | 10/0 | 6/0 | 25/0 | 11/0 | 1/0 | 5/0 | 7/0 | 6/0 |

| Dyspnea | 9/2 | 8/3 | 0 | 7/2 | 20/7 | 12/5 | 8/0 | 8/3 |

| Edema peripheral | 8/0 | 16/1 | 2/0 | 11/2 | 13/0 | 33/0 | 6/0 | 9/0 |

| Hand–foot syndrome | 6/<1 | 1/0 | 25/2 | 2/0 | 0 | 0 | 2/0 | 1/0 |

| Hematologic abnormalities | ||||||||

| Neutropeniaa | 24 /17 | 18/11 | 9/7 | 7/5 | 21/15 | 20/12 | 25/17 | 17/11 |

| Thrombocytopeniab | 16/5 | 12/3 | 0 | 0 | 27/9 | 21/7 | 11/2 | 13/2 |

| Platelet count decreasedb | 14/4 | 13/4 | 51/14 | 38/13 | 11/4 | 14/4 | 2/0 | 4/0 |

| Neutrophil count decreaseda | 10/7 | 13/9 | 42/32 | 50/39 | 8/3 | 7/5 | 1/1 | 4/2 |

| Anemiac | 9/1 | 18/3 | 0 | 0 | 12/3 | 27/5 | 10/0 | 23/2 |

| White blood cell count decreased | 7/1 | 5/1 | 30/4 | 21/7 | 1/1 | 1/0 | 1/1 | 0 |

| Hemoglobin decreasedc | 6/1 | 9/2 | 21/2 | 23/2 | 7/3 | 11/2 | 0 | 4/1 |

Gem, gemcitabine

aUsing terminology of neutropenia or neutrophil count decreased was based on physician's discretion.

bUsing terminology of thrombocytopenia or platelet count decreased was based on physician's discretion.

cUsing terminology of anemia or hemoglobin decreased was based on physician's discretion.

In Japanese patients, axitinib/gemcitabine treatment was associated with higher (>20%) incidence of all-causality fatigue, diarrhea, hypertension, dysphonia, stomatitis and hand–foot syndrome than with placebo/gemcitabine treatment. In addition, hypothyroidism and proteinuria were more common in Japanese patients treated with axitinib/gemcitabine compared with placebo/gemcitabine (hypothyroidism: 8.8 vs. 1.8%; proteinuria: 15.8 vs. 5.4%), but the majority were Grades 1–2.

AEs that led to discontinuation of axitinib treatment in Japanese patients were fatigue, general physical health deterioration, pneumonia, anorexia, neoplasm progression, gastrointestinal perforation and intestinal fistula (one patient [1.8%] each). General disorders (8.0%), including asthenia (4.0%), gastrointestinal disorders (4.0%) and psychiatric disorders (2.7%), were the reasons for axitinib treatment discontinuation in patients in North America, and general disorders (3.9%), including disease progression (2.4%), and hepatobiliary disorders (2.4%), among patients in the European Union.

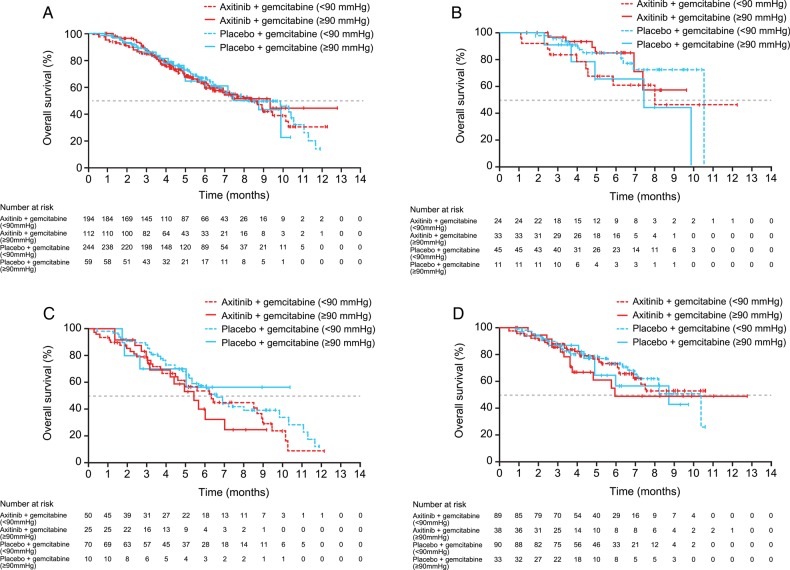

Exploratory analysis for relationship between OS and hypertension

The results indicated that there were no notable differences in OS between axitinib/gemcitabine-treated patients who experienced hypertension (maximum diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg) during Cycle 1 compared with those who did not develop hypertension in the overall study population, in North America or the European Union (Fig. 2A, C and D). Among Japanese patients treated with axitinib/gemcitabine, OS seemed to be slightly longer in those who experienced hypertension than those who did not (Fig. 2B). However, it is unlikely of clinical significance since it was similar to that in placebo/gemcitabine-treated Japanese patients who did not experience hypertension.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates for overall survival by maximum diastolic blood pressure during Cycle 1 for axitinib/gemcitabine vs. placebo/gemcitabine in the overall study population (A), and in patients in Japan (B), North America (C) and the European Union (D).

Discussion

The current analysis by region (Japan, North America and the European Union) of the Phase III trial of axitinib in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer revealed several findings. First, a combination treatment of axitinib and gemcitabine did not improve OS over gemcitabine alone in Japanese patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, which is consistent with results reported in the overall study population (9). Similarly, no survival benefit of adding axitinib to gemcitabine was observed in patients in North America or in the European Union. Second, although the previous Phase II open-label randomized study suggested greater survival benefit of axitinib/gemcitabine in patients with locally advanced than metastatic pancreatic cancer (8), this Phase III study failed to confirm better survival in patients with locally advanced disease in any of the three regions. Third, no difference was found for PFS between the two treatment arms in each region. Although the use of follow-up systemic treatment ranged between 9.1% and 22.2% in the three regions, interpretation of such data to determine their impact on OS would be complicated, given that many of the patients were still on study treatment at the time of the final analysis. It is noteworthy that HR for OS was close to 2 for locally advanced disease and ∼1 for metastatic disease in each region. These results suggested that patients with locally advanced and those with metastatic disease might not respond to study treatment in the same way and thus should be evaluated separately in a clinical study, as has been done in some other Phase III studies (10,11).

Although the lack of efficacy with the combination therapy was consistent across the three regions evaluated, we observed some geographic differences in clinical practice as well as baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the study. Patients in Japan received gemcitabine treatment for the longest duration (5 and 4 cycles started and 119 and 99 days on gemcitabine treatment in the axitinib/gemcitabine and placebo/gemcitabine arms, respectively) and those in North America were the shortest (2 and 3 cycles started and 43 and 71 days, respectively). Generally, longer treatment duration as observed with gemcitabine in Japanese patients in this study may contribute to the better efficacy. The majority of patients in Japan (78 and 77% in the axitinib/gemcitabine vs. placebo/gemcitabine arm, respectively) had ECOG PS 0, in contrast to 38% of patients in either arm in North America. The percentage of patients who had locally advanced rather than metastatic disease was highest in Japan (31 and 34% in the axitinib/gemcitabine vs. placebo/gemcitabine arm, respectively) and lowest in North America (20% in either arm), which might have impacted treatment duration. During treatment, the percentage of Japanese patients with axitinib dose reduction or dose interruption was higher than that in the other two regions, and conversely, a lower percentage of Japanese patients had axitinib dose increase. It is noteworthy that axitinib plasma exposures were similar between Japanese and Caucasian subjects (12,13). Thus, axitinib pharmacokinetics does not seem to account for the higher rate of axitinib dose decrease or the lower rate of axitinib dose increase in Japanese patients. The higher percentage of patients with dose reduction for gemcitabine or axitinib in Japan than in the other two regions could be partly explained by the fact that Japanese patients were on treatment longer, and thus, had more opportunities for dose reduction.

Common AEs experienced by Japanese patients treated with placebo/gemcitabine in this study included anorexia, fatigue and gastrointestinal and hematologic toxicities, which were similar to those reported previously in Japanese patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine (14–16). Addition of axitinib to gemcitabine was associated with ≥20% increase in the incidence of dysphonia, stomatitis, hypertension, fatigue, diarrhea and hand–foot syndrome in Japanese patients, but not among patients in North America or the European Union. Decreased platelet counts, neutrophil counts, white blood cell counts and hemoglobin levels were more frequently reported by Japanese patients treated with either axitinib/gemcitabine or placebo/gemcitabine compared with patients in North America or the European Union. On the other hand, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia were more common in patients in North America and the European Union. In light of the fact that axitinib plasma exposures were similar between Japanese and Caucasian (12,13), it is unclear whether differences in some AEs between Japanese patients and patients from the other two regions indicate pharmacogenomic differences. Additionally, the use of different terminologies (e.g. ‘neutropenia’ vs. ‘decreased neutrophil count’) by the investigators in different regions might have led to some extent to the different incidence rates of hematologic toxicities. Although there were some notable differences in the incidence of some AEs, the current analysis showed that the safety profile of axitinib in Japanese patients was generally comparable to that observed in patients in North America or the European Union.

Hypertension is a known AE associated with axitinib treatment, and a correlation between BP and efficacy outcome has been shown in axitinib-treated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (13,17). An exploratory analysis of data from the Phase II study of axitinib/gemcitabine suggested a possible association between hypertension and OS in advanced pancreatic cancer (8). However, the current analysis did not reveal any significant relationship.

The limitation of the current analyses is that follow-up period in this Phase III study was short, and consequently, there were few events that had occurred before the study was terminated. Hence, OS did not mature at the time of the interim analysis. The lack of efficacy for the combination therapy seen here, however, is in line with disappointing results reported in other randomized Phase III studies of gemcitabine in combination with two other antiangiogenic agents, bevacizumab or sorafenib (18–20). These results suggest antiangiogenic agents, including axitinib, do not appear to enhance the survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer when combined with gemcitabine. Hence, novel agents with different mode of action and/or new approaches are needed to improve survival in these patients.

In conclusion, the addition of axitinib to gemcitabine did not improve OS in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer in Japan, North America or the European Union. Although incidence rates for some AEs differed between patients in Japan and those in the other regions, the nature of common AEs and overall safety profile were generally similar.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at http://www.jjco.oxfordjournals.org

Funding

This work was funded by Pfizer Inc. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Pfizer Japan Inc.

Conflict of interest statement

Tatsuya Ioka has management/advisory affiliation with Chugai Pharmaceutical. Takuji Okusaka received speaker honoraria and research funding from Pfizer. Shinichi Ohkawa, Narikazu Boku and Akira Sawaki have no conflict of interest to disclose. Yosuke Fujii, Yoichi Kamei, and Satori Takahashi are employed by Pfizer Japan. Katsushi Namazu and Yoshiko Umeyama are employed by Pfizer Japan and own stock in Pfizer. Paul Bycott is employed by and owns stock in Pfizer. Junji Furuse received consulting fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly Japan, Pfizer, Bayer Pharmaceutical, and Zeria Pharmaceutical.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Hiroko Godai of Pfizer Japan Inc. for data analysis. Medical writing support was provided by Mariko Nagashima, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions (Southport, CT) and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. [Internet]. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 11. 2013 [cited 2014 January 31] Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (EUCAN) Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). [Internet]. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, V.I.2014 [cited 2014 January 14] Fort Washington, PA: NCCN; Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itakura J, Ishiwata T, Friess H, et al. Enhanced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human pancreatic cancer correlates with local disease progression. Clin Cancer Res 1997;3:1309–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seo Y, Baba H, Fukuda T, Takashima M, Sugimachi K. High expression of vascular endothelial growth factor is associated with liver metastasis and a poor prognosis for patients with ductal pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2000;88:2239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuwahara K, Sasaki T, Kuwada Y, Murakami M, Yamasaki S, Chayama K. Expressions of angiogenic factors in pancreatic ductal carcinoma: a correlative study with clinicopathologic parameters and patient survival. Pancreas 2003;26:344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu-Lowe DD, Zou HY, Grazzini ML, et al. Nonclinical antiangiogenesis and antitumor activities of axitinib (AG-013736), an oral, potent, and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases 1, 2, 3. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:7272–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spano JP, Chodkiewicz C, Maurel J, et al. Efficacy of gemcitabine plus axitinib compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: an open-label randomised phase II study. Lancet 2008;371:2101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kindler HL, Ioka T, Richel DJ, et al. Axitinib plus gemcitabine versus placebo plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a double-blind randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:256–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1817–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1691–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pithavala YK, Tortorici M, Toh M, et al. Effect of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of Axitinib (AG-013736) in Japanese and Caucasian healthy volunteers. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2010;65:563–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rini BI, Garrett M, Poland B, et al. Axitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis. J Clin Pharmacol 2013;53:491–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakai Y, Isayama H, Sasaki T, et al. A multicentre randomised phase II trial of gemcitabine alone vs gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer: GEMSAP study. Br J Cancer 2012;106:1934–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozaka M, Matsumura Y, Ishii H, et al. Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine and S-1 combination versus gemcitabine alone in the treatment of unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer (Japan Clinical Cancer Research Organization PC-01 study). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;69:1197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueno H, Ioka T, Ikeda M, et al. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine plus S-1, S-1 alone, or gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1640–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Tomczak P, et al. Axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: overall survival analysis and updated results from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:552–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Gemcitabine plus bevacizumab compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: phase III trial of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 80303). J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3617–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goncalves A, Gilabert M, Francois E, et al. BAYPAN study: a double-blind phase III randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus sorafenib and gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Cutsem E, Vervenne WL, Bennouna J, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.